ABSTRACT

The paper seeks to provide a critical reflection on theorising perspectives in relation to decolonising occupational science from an insider’s perspective. In this paper ‘theorising’ refers to the means of identifying and collating some of the characteristics that form the problem of coloniality in the discipline of occupational science, and hence contribute to developing ways and means of decolonising occupational science. Various literature sources and theories from occupational science and beyond are addressed to engage the reader in this topic and critical reflection. The paper seeks to encourage the reader to critically review the current occupational science theory/ies, and practice, by offering a critical provocation that asserts that occupational science is institutionally racist and continues to perpetuate and recycle coloniality. A significant aspect of this critical reflection is framed around an adapted version of Professor Leon Tikly’s three pillars of decolonising the university, which has been applied to the topic of decolonising occupational science. The paper concludes by invoking the reader to look inward at the discipline of occupational science and to join in collaboration/s to generatively disrupt the current coloniality of the science, further providing suggestions on ways to do so.

Este artículo pretende ofrecer una reflexión crítica sobre los enfoques de teorización relacionados con la descolonización de la ciencia ocupacional desde una perspectiva interna. En este caso, “teorizar” hace referencia a los medios utilizados para identificar y cotejar algunas de las características que conforman el problema de la colonialidad en la disciplina de la ciencia ocupacional, lo que hace que contribuyan a elaborar formas y recursos para descolonizar la ciencia ocupacional. A fin de implicar al lector en este tema y en la reflexión crítica, se abordan diversas fuentes bibliográficas y teorías de la ciencia ocupacional y de otros ámbitos. Así, se intenta animar al lector a revisar de manera analítica la/s teoría/s y la práctica actuales de la ciencia ocupacional, mediante una provocación crítica que afirma que la ciencia ocupacional es institucionalmente racista y sigue perpetuando y reciclando la colonialidad. Un aspecto significativo de esta reflexión crítica se enmarca en una versión adaptada de los tres pilares de la descolonización de la universidad propuestos por el profesor Leon Tikly, la cual ha sido aplicada al tema de la descolonización de la ciencia ocupacional. El documento concluye convocando al lector a mirar hacia el interior de la ciencia ocupacional y a colaborar para desbaratar, de forma generativa, la colonialidad actual de la ciencia, proporcionando, además, sugerencias sobre las formas de llevarlo a cabo.

本文试图提供从内部人士的角度对生活活动科学去殖民化相关的理论化观点进行的批判性反思。 本文中的“理论化”,是指识别和整理构成生活活动科学学科殖民性问题的一些特征的手段,从而有助于开发生活活动科学去殖民化的方式方法。 来自生活活动科学及其它领域的各种文献来源和理论都旨在吸引读者参与这个主题和批判性反思。 本文旨在鼓励读者批判性地回顾当前的生活活动科学理论和实践,通过声称生活活动科学在制度上是种族主义的,并继续延续和循环殖民性,来提出批判性挑战。 这一批判性反思的一个重要方面是构建于莱昂·蒂克利(Leon Tikly)教授的大学去殖民化三大支柱的改编版本,已应用于生活活动科学去殖民化这一主题。 本文最后呼吁读者向内审视生活活动科学学科,并参与合作,以创造性地去除该科学当前的殖民性,并进一步就如何做到这一点提出建议。

Occupational science is the study of how humans participate in meaningful and/or purposeful activities (occupations) in context (Motimele, Citation2022), and this science informs occupational therapy practice in applying activities of daily living for healing, recovery, rehabilitation, and well-being. In the USA, the development of the discipline of occupational science was driven by the marketisation and corporatisation of universities, and the politics of higher education (Clark, Citation2006; Frank, Citation2012). Its development as a discipline opened up opportunities to research human occupation influenced by public health and socio-economical/political perspectives and challenges (Galvaan, Citation2021).

I began feeling an urgency to write this critical reflection, after having to deeply reflect on and review my lived experiences of attending and presenting at the Inaugural World Occupational Science Conference, in 2022, held in Vancouver, Canada. At the conference I heard from Western and Global South based scholars on a range of wonderful topics and projects related to interrupting marginalisation, the impact of racism/antiracism, the potential of decolonising, and the value of collective action work/generating collaborations; as well as how occupations can be applied to enable change. I presented with Māori scholar, Isla Emery-Whittington, on decolonising occupational science (it must be said here that the abstract published in the Journal of Occupational Science was initially incorrect. This was subsequently corrected).

Following our presentation, we received a long ovation which was supposed to be a positive recognition of our work. However, I was left feeling a lack of urgency around a recognition of the necessity to address issues of racism and coloniality in occupational science. I am aware that such a sense could be construed as making sweeping generalisations, but these are my own subjective experiences of the conference at the time. Such experiences were perhaps informed and further exacerbated by one white Canadian leader (at the final day of leaders’ presentations), referring to the persuasiveness skills of another presenter they were introducing, as someone who could ‘sell fridges to [outdated/offensive term referring to the Inuit and Yuipik]’. The leader appeared completely oblivious to the exploitative meaning in that phrase and painfully my mind wondered straight to coloniality—it made me feel very uncomfortable and reinforced this sense of not belonging.

Thoughtlessness in such matters, albeit clearly unintentional, hurts, and then if more systematically continued, it can harm individuals, groups, and communities. This brings me to my reflective piece: its purpose is to encourage and even convict the occupational science community to looking inward in relation to how coloniality shows up in multiple spaces, before thinking about decolonial praxis outwardly. Gibson (Citation2020) supported that critical reflexivity and reflection by the occupational science and therapy communities is a process by which to develop actions to disrupt institutional racism and racist practitioners’ power structures. My contention or provocation in this critical reflective piece is that occupational science is institutionally racist due to coloniality. To enable further critical reflections around my contention, I believe the concept of coloniality must be better understood, because without such understanding there may also be a lack of awareness that coloniality lives and operates systemically in theories such as occupational science, leading to institutional racism.

For the sake of transparency, I will declare my own positionality. I am a dark-skinned person of South Asian heritage, Bangladeshi, who is an academic and acknowledges the power and privilege in that role, and I live in the UK in the heart of the metropole. I am an educator in occupational therapy and teach occupational science topics. Critical reflections, such as this, from those members of the profession who are Minoritized, can constitute a decolonial act in itself, because this kind of critical thinking from a Minoritized occupational therapist does not form the majority narrative and therefore has the ability to disrupt more dominant ways of thinking and knowing. Such acts of decoloniality are not fixed prescriptions; they change with the advancement of knowledges and changing contexts, inclusive of cultures, countries, and chronology (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Citation2021).

Coloniality is the sustaining and recycling of the characteristics of colonialism structurally and collectively in current knowledge, practice, and culture, continuing the disadvantage, marginalisation, and harm to Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized populations through enacted governance, policies, and leadership (IGI Global Publishers, Citationn.d.). Occupational science was developed by people from the Western globe. It is dominated by theories and viewpoints developed from Western centrism, and its leaders in the main are white Western individuals keeping hold of the white gaze. The same could be translated to occupational therapy, as occupational science informs the therapy, and its theories and practice are built on Western culture. Occupational science brings an occupational perspective to issues of social justice and human rights to reveal aspects that may not have been previously evident, such as how discrimination plays out in people’s everyday occupations. This includes being excluded from valued occupations or relegated to devalued occupations, causing real harm that can become intergenerational. The people who developed, and currently develop, these concepts in occupational science were/are from privileged positions and hence perpetuate coloniality and white supremacy because they do not identify or analyse social harms from these perspectives (Emery-Whittington, Citation2021; Grenier, Citation2020; Ramugondo, Citation2018).

It therefore seems imperative to ask: Whose human rights, whose social justice, how and where have the concepts been framed from? Whiteness/white gaze is not a colour: it is a way of being, beliefs that create power hierarchies to oppress and create racial disparities in ways that keep benefitting that group (Advocate Muzi Sikhakhane in an interview by Mpofu-Walsh, Citation2023). White supremacy is an ideology that is used as an instrument for oppression and social segregation. It is how whiteness shows up to promote power and racial hierarchies, individualism, and what is meant by professionalism (Almeida et al., Citation2019; Blackdeer & Ocampo, Citation2022), and this is relatable to occupational science and therapy disciplines (Grenier, Citation2020). For example, the lack of diversity in the leaderships of occupational science and therapy is generating knowledge and practice aligning to Western standards, a narrow perspective. But this perpetuates imbalance in power dynamics as it is facilitating people into leadership that are similar in the predominant racial make-up of the current leaderships, and this continues the lack of diversity, and the cycle continues. So, from the explanations thus far it can be seen why coloniality can be attributed to the historical and current conception of occupational science.

There has been an increasing focus on decolonising occupational science, which is building momentum for the discipline to interrogate itself and act to change for contemporary global relevance, for example Ahmed-Landeryou et al. (Citation2022), Emery-Whittington (Citation2021), Simaan (Citation2020a), Gibson (Citation2020), and Ramugondo (Citation2015, Citation2018). These authors are calling on the occupational science community to disrupt its dominating Western centrism and neoliberalism, hence coloniality replay, a ‘short-hand’ term I use to express continuing reproduction/representation of coloniality, that is tangled in the continuing contribution to institutionally racialised discrimination of Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized populations, potentially leading to inequitable occupational therapy service provision, further promoting health inequities. I speculate that the general hesitation to engage in decolonising actions could be due to ignorance, complacency, or seeking to avoid discomfort, that comes from power and privilege.

“Health inequities are systematic differences in the received healthcare status of different population groups” (WHO, Citation2018), leading to significant racial disparities in health further leading to impacting individuals and communities socio-economically. South African political thinker and activist, Advocate Muzi Sikhakhane, has said that economically just systems lead to antiracism because it sees all communities in equal value as a starting point (Mpofu-Walsh, Citation2023). Sikhakhane continued that racial disparities are the end outcome of coloniality in the system (Mpofu-Walsh Citation2023). Coloniality is the values, episteme (ways of knowing), and power structures that were in the Western ideology of colonialisation that is continuing today in disciplines, structures, and institutions, discriminating, oppressing, and harming (Mignolo & Walsh, Citation2018; Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Citation2013). Frank (Citation2022) added that neoliberal education and healthcare institutions have pushed occupational science to be more of a research brand, a capitalist notion, rather than an explanatory science. Whilst there have been attempts to show how to decolonise occupational science (e.g., Motimele, Citation2022; Ramugondo, Citation2015, Citation2018; Simaan, Citation2020a, Citation2020b), there seems a distinct lack of any visible change.

It is important, in context of this critical reflection, that the term decolonisation and its associated terms are understood. For this purpose, a description of decolonising knowledge taken up by Humboldt University social work department, in the USA has been used:

Decolonization is the intelligent, calculated and active resistance to the forces of colonialism that perpetuates the subjugation and/or exploitation of our minds, bodies, and lands, and it is engaged for the ultimate purpose of overturning the colonization structure, and realizing Indigenous liberation. (Wilson & Bird, Citation2005, p. 5)

Emery-Whittington (Citation2021), in her Golden Quill CAOT 2023 awarded paper titled ‘Occupational justice - Colonial business as usual? Indigenous observations from Aotearoa’, impresses on us that the problems with occupational science, occupational therapy, and terms such as occupational justice are that these are instruments implicated in acculturation and the normalising hegemony of the Western gaze in the disciplines. Emery-Whittington further asserted that within occupational science and occupational therapy, racism, coloniality, imbalance of power, and privilege are rarely raised, let alone interrogated. This tendency supports Guajardo Córdoba’s (Citation2020) assertion that occupational justice is “a new form of epistemic and cognitive colonization of the profession, which operates under universalist, essentialist, liberal assumptions, typical of modern Eurocentric rationality” (p. 1365).

Decolonising is being continuously active in actions for decolonisation, and decoloniality is praxis (conceptualising conditions for enacting and undoing coloniality) (Mignolo & Walsh, Citation2018). Furthermore, Fúnez-Flores et al. (Citation2022) explained in regard to decolonial praxis that “decolonial thought and praxis, in other words, is dynamic and heterogeneously configured” (p. 614), adding that it does not belong to a handful of Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized scholars to do the decolonial work.

Reflection has always been promoted in the disciplines of occupational science and occupational therapy but appears, in my view, to shy away from discussions or research on racism and decolonising, which is limited. This reflective piece critically explores the coloniality of occupational science, with the intention of highlighting the urgent need for the occupational science community to critically look inward at the discipline and involve ourselves in decolonial actions now.

I used the term theorising in the title of this piece, as the focus of theorising is not developing a theory of decolonising occupational science as an end product but developing the characteristics of the problem by viewing it through many perspectives (Hammond, Citation2018; Swedberg, Citation2012). In relation to occupational science, the problem would be referring to coloniality in the discipline and how and why to take a decolonising approach, asking oneself how it is showing up in many ways in occupational science literature, research, discussions and more. I am hoping my reflections will in some way go towards elucidating this. Theorising on the topic of decolonising occupational science is a decolonial act as it is challenging and interrupting the status quo.

The main critical discussions in the content of this paper are around three proposed pillars for decolonising occupational science through answering ‘what if’ questions, with illustrations and practical suggestions of actions to start on the path of decolonising. The decolonising work is not for one or a few, but for all in the communities of occupational science and therapy.

Reflecting on Theorising Perspectives of Decolonising Occupational Science to Reimagine a Different Future

The reflective piece is organised with reference to Professor Leon Tikly’s three pillars of decolonising the university: decolonising the curriculum, democratising the university, and decolonising research (Wilkinson & Zou’bi, Citation2021). I have adapted the pillars for decolonising occupational science to provide a framework to springboard thoughts for reimagining and rebuilding the discipline. The interpreted three pillars for decolonising occupational science could be:

Decolonising occupational science education

Democratising occupational science (e.g., the governing bodies of the International Society of Occupational Science, SSO: USA, Journal of Occupational Science, etc)

Decolonising occupational science knowledge generation and dissemination.

What if occupational science education takes a decolonising approach?

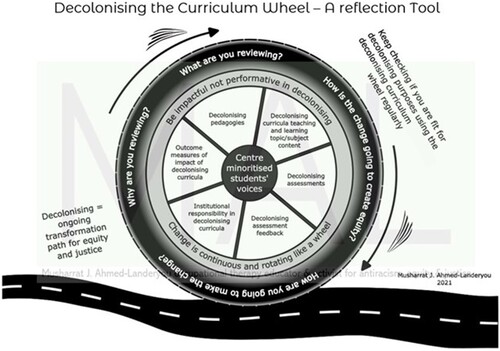

Professor Tikly has said that the reason we are wanting to decolonise education or deliver a justice-based education is because the long shadow of colonialism is present in contemporary education, discriminating against Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized staff and student populations, who have intersecting identities of being, for example, disabled, LGBTQIA, and socioeconomically disadvantaged (Wilkinson & Zou’bi, Citation2021). Ahmed-Landeryou (Citation2023) developed an evidence informed Decolonising the Curriculum Wheel from a scoping literature review and meta-analysis of reports of 12 focus groups of students discussing their experiences of the university as Minoritized and marginalised students (). The wheel was developed to aid deep interrogation and reflection for reimagined transformation. By taking this approach Professor Tikly may suggest that the wheel is assisting in disrupting the five main monocultures of knowledge by decentring the monopoly of Western centrism of knowledge and progress, and centring Black and Minoritized populations as equal in knowledge production and dissemination. The five main monocultures of knowledge being challenged are:

Exclusive focus on Westernised science and philosophy,

Naturalisation of differences between humans (i.e., men and women, people from different countries, the different levels of human),

Dominance of Western ideas of progress,

Normalcy of Western knowledge globally,

Capitalist monopoly of knowledge production.

The wheel provides guidance on the topics to travel through, enabling a start to interrogating historical and current ways of occupational science education. This in turn helps to develop transformative decolonising actions for occupational science theory and practice. I will briefly describe the parts of the wheel to expand on the contents of the wheel figure.

The central linchpin of the wheel

Decolonising transformation must start with the Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized students’ and communities’ views and them working in collaboration for coproduction with academics and all staff involved in their time at university at every level; and at every stage of the educational and institutional transformation process, not only for development but also for monitoring and reviewing. That is, it is important to recognise that the decolonising approach is centring not all voices from marginalised groups, but only Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized persons. If the ‘knotty’ problem of institutional racism is tackled, this will improve things for all marginalised groups, and all populations potentially. This is not essentialising or problematising the BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and persons of colour) students and communities, but collaborating with them to design education that is built on belonging. It is important if students, or communities, are helping us in this way that they get paid to equalize the space of influence, as it would foster unequal power dynamics if the students/communities are the only unpaid participants around the table.

The spokes of the wheel

Here, six areas are identified to start taking a deep dive around the curriculum, analysing and evaluating how the areas are performing in relation to the BIPOC students’ needs and experiences to enable success. You start at one place and move round the wheel, also enabling a returning to the categories.

The rim of the wheel

This includes the reminder to check in how the curriculum is being impactful not performative, and a statement as a reminder that decolonising the curriculum is continuous, so this is not a one-off action but an ongoing process.

The tyre of the wheel

Here, there are four prompt questions to start the deep interrogation and reflection:

What are you reviewing?

Why are you reviewing it?

How is the change going to create equity?

How are you going to make the change?

Practically, this may mean exploring the cultural relevance of assessments before using them with the communities occupational scientists or occupational science educators/researchers work with, critically assessing whether their use would disadvantage the community (Simaan, Citation2020a). Or wondering how Indigenous therapists and communities could be enabled to “reclaim valued and healthful occupations such as dreaming, theorizing, meeting, speaking, and listening that promote reconnection to self, one another, and nature” (Emery-Whittington, Citation2021, p. 158).

In the end, decolonising occupational science education would entail attempts to create a space that belongs to all and is culturally responsive, where there is acknowledgement of the value of diverse cultures’ epistemes. This acknowledgment would also call for a deeper awareness that the discipline needs to adapt to create conditions to integrate these epistemes; and thereby enable occupational scientists to have global awareness and occupational science to have global relevance. The symbol of the wheel is to enable not only a moving forward, but also a continual return to changes made, to check if they are still fit for the purpose of decolonising.

Every aspect of education, if left unchecked, runs the risk of simply reproducing coloniality, ultimately predominantly benefitting the white or privileged students. Furthermore, unchecked education, in whatever form, will arguably translate into the recycling of institutional racism and discrimination through well-meaning but uncritical coloniality in education, which in turn becomes further recycled through our students as they become part of the workforce. It is therefore critical that, as part of the occupational science’s educational content, coloniality in occupational science and its contribution to racial health disparities is discussed. Only then, as argued in Simaan’s (Citation2020b) paper on decolonising education, can the recycling of whiteness as a normative measure of good standards be stopped. Thus, a readiness of occupational science to be authentically culturally responsive and adaptable, and the ability to work with the collective independence present within communities, would be enabled.

A decolonising education enables the adding of knowledges from the Global South, from Global South authors, or Western authors of Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized heritage into occupational science education. Doing so enhances disciplines to be knowledges based, not Western centric knowledge based, thus enabling equity and justice into occupational science education and exposing and disrupting institutional racism and discrimination and improving belonging for all.

What if occupational science democratises?

Democratising means collective participation and collaboration with students, researchers, educators, practitioners, and leaders to challenge institutional racism, discrimination, and coloniality, and them having “a role in determining the structure, content and process” (Tikly & Barrett, Citation2011, p. 5) of occupational science. The challenges arguably are unwittingly (uncritically) perpetuated by the occupational science community, ultimately leading to the gatekeeping of Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized populations, their knowledges, and ways of knowing. In my view, considering the context of this critical reflection, the Western centric occupational science community has sat on its privilege and power to make little impact for Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized communities, nor centring our voices, and have made limited collaborations with us to bring the discipline and therapy into the realities of the 21st century for all service users and occupational science memberships.

An example of harm to membership when coloniality is unchallenged is demonstrated in an Instagram post by Associate Clinical Professor Toni Solaru (Citation2023). The post identified a presenter at the ASPIRE American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) conference 2023. Interpreted from their perspective, they heard a past president of the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) present a defence that the way Black populations had been treated was because white people did not see Black people’s humanity, adding that this was a common attitude in the 1980s. Solaru, expressing their sadness over the voicing of such views, went on to state that Black AOTA members told them that they were harmed by the statement of this high profile ex-president, terming it as white violence and supremacy.

Gebhard et al. (Citation2022) would identify this incident as white benevolence, where white paternalism maintains racism and thus the status quo of power difference, harming, excluding, and marginalizing instead of challenging the status quo of dominance of whiteness and coloniality. Occupational science leaders need to equalize the space, meaning reducing or removing the power imbalance and improving belonging in environments, for Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized populations, and underrepresented groups. They need to be discussing the changes and doing the change work in collaboration with these groups.

Occupational science is described by its founders as studying the context of where, how, and why human beings do what they do, which cannot be understood without deep exploration (Motimele, Citation2022). But, critically thinking, I am asking whether this related to all human beings. Occupational science was conceived and designed by Westernised leaders for populations from the Western centric globe. It is therefore arguable that the discipline predominantly shares a narrow conceptualisation of occupational science for dissemination, application, and research. Indeed, it can be further argued that the leaders and authors continue to engage in gatekeeping practices, thereby retaining their power and benefit, however much their good intentions are to promote diversity, inclusion, and justice, because there is an uncritical centring of whiteness. This white centring is exemplified by Townsend’s (Citation2020) response to Simaan’s (Citation2020a) article ‘Decolonising Occupational Science Education through Learning Activities Based on a Study from the Global South’. Townsend advised Simaan to refer to white authors to enhance his article. The advice completely negates the focus of decolonising, which is centring the voices and presence of Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized populations and de-centring whiteness. Such a response was likely well intentioned, but uncritical, seemingly taking no account of his article’s decolonising perspective.

Gibson and Farias (Citation2020) suggested that the hegemony in occupational science is predominantly “privileged Western, middle class, white, heterosexual, and able-bodied women’s ways of understanding occupation that generally fit occupational science education” (p. 445). Colonialism identified the superior population as: white, Christian, male, able bodied, heteronormative, English speaking, middle-upper class, affluent, university educated, and more. This is argued to continue via coloniality, an ongoing imposition of dominance, values, and beliefs through a system of power (Mignolo & Walsh, Citation2018).

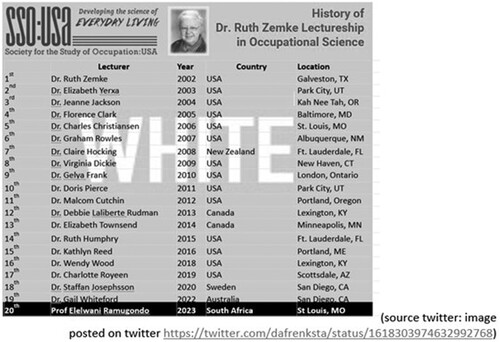

Such an argument of white dominance in occupational science is exemplified by . It depicts who has been allocated for the Ruth Zemke lectureship from 2002-2022. Some questions to ask, to understand how and why coloniality is prevalent would be who awarded the speakers and who and how was it decided that these speakers would be chosen for the Society of the Study of Occupation USA membership to listen to. Such critical questions may be uncomfortable for some, but such discomfort is arguably necessary for any attempts at progress. To deal with the discomfort, I ask that we start by naming and framing why the discomfort is occurring, because it is not the job of the person experiencing racism or othering to help individuals to understand, Change, and ‘heal’. It is the responsibilities of individuals and collectives to disrupt the white gaze of the list (), and to democratise it, facilitating an understanding of the answers to questions such as why this list is occurring, and why it took until 2023 for us to choose Professor Ramugondo as a speaker.

I say ‘we’ because it is all our responsibilities in the occupational science community to challenge by asking the why questions. Ramugondo (Citation2018) called on us, in the occupational science and therapy communities, to show up in many ways to abate the influence of coloniality. To abate coloniality in occupational science we need to further understand the influence of coloniality in occupational science. One way to do this is to consider what Quijano (Citation2000) termed ‘the coloniality of power’, a quadrant matrix of how coloniality is kept in play through four factors: economy, authority, gender and sexuality, and knowledge, fuelled by racism, patriarchy (paternalism), and colonialism. To further aid theorising and understanding how coloniality is sustained by occupational science and therapy, I discuss this with reference to the four factors of the matrix of the coloniality power.

Economy

Labour and resource exploitation and extraction from Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized groups, and hierarchy of pay for labour, in that these populations are mostly in the lower pay scale jobs or expected to do additional imposed free labour at work due to precarity of working. Supporting this assertion, I offer two examples. First, the trend that the people hired for low pay jobs in organisations are from Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized populations, and organisations are not taking responsibility to put in place strategies to support career progressions for these populations. Second, US educational institutions continue to be situated on forcibly acquisitioned land for economic gain. See for example, the High Country News website identifying “land-grab” universities (Lee et al., Citation2020). Although them declaring land acknowledgement is a start, their actions need to go further by showing accountability with such actions via reparations. Not showing responsibility and accountability sets up and embeds a hierarchy of difference between those that have the power of finances and those who do not.

Authority

This factor comes about by setting up a fallacy as part of colonial thinking that communities and individuals from Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized populations have less knowledge, abilities, agency, and autonomy. Hence, these populations need to be taught civility, governed, and advocated for, in order for them to survive and exist. Dhillon et al.’s (2010) study identified themes as to reasons why therapists participate in advocacy (e.g., selfish reason for job satisfaction, rationalising that the person needs the more powerful status of the occupational therapist to access help, or linking it to human rights and quality of care). Thus, the factor of ‘authority’ is setting up and validating the construct that those who hold power are superior and those who don’t are lesser or othered humans, hence possibly justifying, to those who have power, perpetuation of the injustice, exclusion, and oppression put upon those who do not have/have less power (Mignolo & Walsh, Citation2018).

Gender and sexuality

This factor refers to forcibly situating colonial constructed societal norms and conventions. For example, gender initiatives in education usually benefit the white women because these changes are happening within institutionally racist and colonial organisations (Bhopal, Citation2018). Another example is that studies regarding the intersectionality of LGBT + populations are very limited (e.g., the Black Trans populations and occupations). In the queer community, there is history of the dominating presence of the white man (Stonewall, Citation2018), and currency of continuing racism (Jones, Citation2016), which then could impact on occupational opportunities and health outcomes. These disparities are due to the sustaining of colonialism and patriarchy/white benevolence structurally, resulting in racism, discrimination, and oppression for the Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized populations in comparison to the dominating groups.

Knowledge

This factor relates to recycling colonial constructed epistemology and education norms for occupational science across the globe (Simaan, Citation2020a, Citation2020b). The dominance of white women in leadership, scholarship, and research positions is maintaining the power to push through a narrowed worldview of occupational science and therapy globally (Gibson & Farias, Citation2020). This could have a knock-on effect (i.e., gatekeeping) on what topics are deemed worthy to research, teach, and disseminate, and who will be involved in and delivering this, as explicated by Ramugondo (Citation2022).

Some may counter what I am saying in this section by referring to social occupational therapy in Brazil, where occupational science and therapy scholars are going into and working with Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized communities. The communities lead the scholars in the work on what matters to them, to address social inequalities and marginalization (Lopes & Malfitano, Citation2021). The professionals here are using their privilege and power for good, but the concept of racism and whiteness is not discussed within social occupational therapy, which makes me wonder critically, whether the space is really equalizing as the power imbalance potentially remains.

To develop and sustain decolonising transformative change in occupational science, it would be beneficial to consider Dobbin et al.’s (Citation2007) suggestion on what makes for sustainable impactful change in diversity for organisations for the discipline of occupational science. Their research spans over 829 corporate companies in America, taking over 31 years to identify their suggestions. Just attending to diversity is not decolonising, but the paper identified three factors that help to sustain transformative change, which could be translatable for democratising occupational science: leadership, establishing a task group, and building a mentorship programme. Leadership should role model the culture change for implementing and applying a decolonising approach as an integral part of the science. To be able to enact this transformation there must be support and resources in place. The task group would, potentially, monitor and review decolonising actions being implemented and hold the community to account, also having the agency to make decisions. Such task groups must be funded and resourced and be part of the strategic decolonising action plan for occupational science. Who will be in the task group should be reviewed in collaboration with Black and Minoritised populations in occupational science communities/groups. The vision for building a mentorship programme is that occupational science societies/groups would source a pool of mentors for Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized practitioners, scholars, and students. The occupational science societies/groups must take responsibility to look after the mentorship programme to ensure that the mentees get the best out of the experience, gaining opportunities they would not otherwise have had, such as leading research, leading a co-authored group, or being sole author in writing a paper.

Occupational science societies/groups could generate disruptive actions to interrupt the status quo of coloniality in the discipline through collaborations building relations for community activism (Galvaan, Citation2021; Simaan, Citation2020b). I say activism rather than advocacy, because activism is born out of struggle, and shared struggle brings people together to take action to disrupt the status quo and generate knowledge and ways for change.

Gathering communities through shared interests and goals to advance decolonising action is not new. It is arguably akin to the concept of ‘interest convergence’ in Critical Race Theory, where the rights and interests of Black populations only moved forward when they converged with the interests of whiteness (Bell, Citation1980). Interest convergence is a way to engage those with power to join in making change, because then the change wanted matters to those in power, as ultimately what matters gets attention, which would potentially better the BIPOC communities’ opportunities, environments, and abilities to thrive.

There are pockets of activism in occupational science groups in different nations, for example, Aboriginal groups in Australia (e.g., Gibson, Citation2020), Māori groups in New Zealand (e.g., Emery-Whittington, Citation2021), and First Nation groups in Canada (e.g., Phenix, in Restall et al., Citation2019). These authors and their groups point out how coloniality is still in play, perpetuating the injustices and harms, and represented in racial disparities data, but also sharing ways of knowing and being to bring change generatively and collectively as occupational science groups.

What if occupational science knowledge generation and dissemination does take a decolonising approach?

Ramugondo (Citation2022) expounded that you cannot think about theorising without interrogating who is enabled to be a theorist, who is thought of as a theorist, who is thought of as legitimate in knowing and knowledge productions, and who is making those decisions. This is about who is in power and gatekeeping knowledge generation and dissemination, and which groups are getting the allocation to do this scholarly activity. My perspective is that the process of producing knowledge/theories by Western centric scholars who research communities/populations outside their own, where that knowledge production is in relation to communities that are from Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized groups, should not be leading the research. They should collaborate with the members of the community to partner in the research or have a researcher from the same community heritage to lead the research. In this way, they are using their power and privilege to even the playing field by stepping aside completely, or co-investigating, or to support and guide. This is disrupting coloniality and hence also becomes a decolonial act.

In an open letter from UK-based charity, Ladders4Action (Citation2020), to UK Research and Innovation Institute (UKRI) (one of the larger funding bodies for research), 10 Black researchers, with 3000 signatures of support, identified that £0 out of the £4.3million available of funding was given to Black leads for researching COVID19. In addition, one of the funding assessors was on three out of the six successful submissions as a co-investigator. Ladders4Action (Citation2020) stated that according to UK HESA data (Higher Education Statistics Agency), only 1.3% of full-time researchers are Black or mixed-heritage women. This is arguably an example of colonial replay and institutional racism demonstrated through keeping certain groups out, to further the advantage of the dominant group.

There should be a review of how many Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized individuals/groups were able to gain funding to carry out occupational science research compared to their white counterparts. Occupational science and therapy UK research with Black, Asian, and Minoritized groups is limited and usually, if funded, is carried out by the white lead researcher. You can count them on one hand, again demonstrating evidence of coloniality. Organisations giving out research grants need to review their processes to check they are not favouring those in power, and thereby replicating unequal power relations. Even if it is so called blinded, well-known frequent researchers could still be favoured, because of how the application is written.

Research grant providers should collaborate with Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized researchers and the public to review and rewrite content of grant applications. Lead occupational science researchers could use their power and privilege and offer time to support Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized researchers applying for grants, to help them write applications. Any research with Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized participants should be demonstrating collaboration at every point of the research so that space is equalized, whilst the researcher should feedback to the groups as to the changes to be made and the potential impact.

In my research to inform this critical reflection I conducted an informal scope of publications on the Journal of Occupational Science website. I used search terms racis* or decolon*. I identified 178 records, removing duplicates 86 papers remained that mention the search terms in the title, abstract, or at least once in the body of the text. Not all the identified papers were publishing research. A total of 204 authors (including repetition of names), 122 white authors (60%) and 82 BIPOC (40%) (searched bios & pictures through google), 56 papers (65%) were single white authors or white authors leading a group, and 30 BIPOC (35%) single or leading a group. If you took the duplications of authors out, the numbers changed slightly to increase the difference between the white and BIPOC authors. The date range of the included papers was between 2002-2023 (21 years, could be considered as ∼4 papers a year on the identified topics), but most of the papers clumped around 2019-2022. Two points I noted were:

There were papers that had leads who were white for research on BIPOC communities (e.g., Huff et al., Citation2022). I would suggest that having leads who are white for papers on such topics should be deterred, as this arguably constitutes colonial replay. It is role modelling in essence what the Ladders4Action are campaigning against, in that you need a white lead for research to be funded and, I add, possibly for papers to be published on racism and colonialism in general in journals. Supporting that point, I posit that people racialised as white will ‘listen’ to a same racialised author discussing issues such as institutional racism, as they respond to cues in the writing style and vocabulary (for example) that reveal the author(s) positionality, worldview, educational level, disciplinary background, and so forth. Such considerations offer possible reasons as to why there are many publications by Whalley Hammell and Beagan on the topic in journals.

Eighty-six papers in 21 years indicates the limited publications in this journal addressing decolonising or racism in occupational science. This is termed as scholars being ‘health equity tourists’. When topics such as racism gain increased attention in publications due to popularity/trendiness of the topic, this is coloniality. The term ‘health equity tourist’ was coined by Lee McFarling (Citation2021), referring to publications in medical journals by white scholars giving attention to the social topics when popular or trendy and not as continuously necessary.

Looking and going forward, it would be helpful to have a free central repository where people can place case stories which give examples of decolonising in occupational science. This would help the occupational science community to build evidence of who is doing what and where, regarding decolonising in the discipline. Such transparency could then also elucidate the impact and outcomes in applying decolonising approaches to occupational science in education, practice, and research. Dominant leaders and the community should role model actions, showcasing implementation of antiracist approaches and decolonial actions through collaborative working.

It may be critiqued and pointed out that I am focusing on the people making the knowledge instead of the process of how they are producing theory, but as already identified we must also interrogate who is producing knowledge (Ramugondo, Citation2022). This informal review shows where most of the knowledge producers are located in the publications, hence who is holding the power of generating and disseminating knowledge for occupational science from the Journal of Occupational Science. This then perpetuates Professor Tikly’s five monocultures of knowledge mentioned earlier, as the range of the papers were in the main narrowly generated from the Western side of the globe.

Conclusion

Members of the occupational science community need to hold themselves accountable for enabling the status quo of racism and injustices still experienced by Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized groups. There does not seem to be a systemic urgency for decolonising occupational science ethically and morally; and in relation to its theories which are still dominated by knowledge that are Western centric. This is arguably coloniality replay. It is necessary that all forms of racism and coloniality are made manifest in the discipline of occupational science before starting decolonising. Relating back to the ‘coloniality of power’ matrix, the proposed actions thus far from this paper concentrate on authority and knowledge. The occupational science and therapy communities, which encompass associations, educators, researchers, students, and leaders, could continue using this matrix to formulate further actions based on the four factors of economy, authority, gender and sexuality, and knowledge, to start actions for disrupting institutional racism, paternalism, and colonialism. This is not an end point but a continuous process of reviewing and reconstructing to abate coloniality.

Yes, there are scholars who are writing about ways to be and act to engage in decolonising, but in general decolonising seems to still be a special interest project/subject rather than an integral consideration in occupational science. However, there are authors from the Global South, Indigenous, and Black populations who have published in the Western based publications to get more views so that the topic of decolonising is shared more widely. It would perhaps be advisable to produce a systematically informed heat map of all the books and journals specific to occupational science, to show the countries of the publications and the heritage of the authors. By doing this we could then globally make an action plan for change that is contextual to the data. This would equalize the space for Black, Indigenous, and Minoritized authors wanting to publish on decolonising occupational science to have more presence and standing to hopefully influence just change. This would be a decolonial act. What is needed is that the journals in the West that share decolonising occupational science theories and practice equalize the space and make the journals open access for all. This would also constitute a decolonial act.

In summary, the key points from this reflection are that the community, in general, tends to not be critically reflexive in terms of how coloniality is manifested in them, in their communities, and the discipline of occupational science, so the tendency is not to be cognisant regarding applying a decolonial praxis in context. Occupational science cannot be justice-based if the work is not for the liberation of all. Critically committing to decolonising approaches, and thereby recognising and consciously steering away from coloniality, is not just for a particular group, but will benefit humanity.

A potential limitation of this paper is that it is written by a single author and would have benefitted from involvement of more authors to broaden perspectives of discussions. However, I do not see this as a one-off paper, but a topic for further collaborative critical conversations to publish in the future.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges Lily Owens (especially), Dr. Frank Kronenberg (challenging me to improve by critical thinking), and Dr. Roshan Galvaan and Chantal Christopher, for their support. For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising. If you need to discuss further please email the university at: [email protected]

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahmed-Landeryou, M. J., Emery-Whittington, I., Ivlev, S., & Elder, R. (2022). Pause, reflect, reframe: Deep discussions on co-creating a decolonial approach for an antiracist framework in occupational therapy. Occupational Therapy Now, 25(March-April), 14–16.

- Ahmed-Landeryou, M. (2023). Developing an evidence-Informed decolonising curriculum wheel – A reflective piece. Equity in Education & Society, 2(2), 157–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/27526461231154014

- Almeida, R. V., Werkmeister Rozas, L. M., Cross-Denny, B., Lee, K. K., & Yamada, A.-M. (2019). Coloniality and intersectionality in social work education and practice. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 30(2), 148–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428232.2019.1574195

- Bell, D. A. Jr. (1980). Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest-Convergence Dilemma. Harvard Law Review, 93(3), 518–533. https://doi.org/10.2307/1340546

- Bhopal, K. (2018). White privilege: The myth of a post-racial society. Policy Press.

- BlackDeer, A. A., & Ocampo, M. G. (2022). #SocialWorkSoWhite: A critical perspective on Settler colonialism, White supremacy, and social justice in social work. Advances in Social Work, 22(2), 720–740. https://doi.org/10.18060/24986

- Clark, F. (2006). One person’s thoughts on the future of occupational science. Journal of Occupational Science, 13(2-3), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2006.9726513

- Dhillon, S. K., Wilkins, S., Law, M. C., Stewart, D. A., & Tremblay, M. (2010). Advocacy in occupational therapy: Exploring clinicians’ reasons and experiences of advocacy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. Revue Canadienne D’ergotherapie, 77(4), 241–248. https://doi.org/10.2182/cjot.2010.77.4.6

- Dobbin, F., Kalev, A., & Kelly, E. (2007). Diversity management in corporate America. Contexts, 6(4), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1525/ctx.2007.6.4.21

- Emery-Whittington, I. (2021). Occupational justice – Colonial business as usual? Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 88(2), 153–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/00084174211005891

- Emery-Whittington, I., & Te Maro, B. (2018). Decolonising occupation: Causing social change to help our ancestors rest and our descendants thrive. New Zealand Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65(1), 12–19.

- Frank, G. (2012). The 2010 Ruth Zemke Lecture in Occupational Science. Occupational therapy/occupational science/occupational justice: Moral commitments and global assemblages. Journal of Occupational Science, 19(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2011.607792

- Frank, G. (2022). Occupational science’s stalled revolution and a manifesto for reconstruction. Journal of Occupational Science, 29(4), 455–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2022.2110658

- Fúnez-Flores, J. I., Díaz Beltrán, A. C., & Jupp, J. (2022). Decolonial discourses and practices: Geopolitical contexts, intellectual genealogies, and situated pedagogies. Educational Studies, 58(5-6), 596–619. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131946.2022.2132393

- Galvaan, R. (2021) Generative disruption through occupational science: Enacting possibilities for deep human connection. Journal of Occupational Science, 28(1), 6–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2020.1818276

- Gebhard, A., Mclean, S., & St. Denis, V. (2022). White benevolence. Fernwood Publishing.

- Gibson, C. (2020). When the river runs dry: Leadership, decolonisation and healing in occupational therapy. New Zealand Journal of Occupational Therapy, 67(1), 11–20.

- Gibson, C., & Farias, L. (2020). Deepening our collective understanding of decolonising education: A commentary on Simaan’s learning activity based on a Global South community. Journal of Occupational Science, 27(3), 445–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2020.1790408

- Grenier, M-L. (2020). Cultural competency and the reproduction of White supremacy in occupational therapy education. Health Education Journal, 79(6), 633–644. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896920902515

- Guajardo Córdoba, A. (2020). About new forms of colonization in occupational therapy. Reflections on the idea of occupational justice from a critical-political philosophy perspective. Cadernos Brasileiros de Terapia Ocupacional, 28(4), 1365–1381. https://doi.org/10.4322/2526-8910.ctoARF2175

- Hammond, M. (2018). ‘An interesting paper but not sufficiently theoretical’: What does theorising in social research look like? Methodological Innovations, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2059799118787756

- Hittler, J. (2018). The genius of asking the ‘what if’ questions. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbescoachescouncil/2018/05/16/the-genius-of-asking-what-if-questions/?sh=7cac207b22ef

- Huff, S., Laliberte Rudman, D., Magalhães, L., & Lawson, E. (2022). Gendered occupation: Situated understandings of gender, womanhood and occupation in Tanzania. Journal of Occupational Science, 29(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2020.1852592

- IGI Global Publishers. (n.d.). What is coloniality? https://www.igi-global.com/dictionary/funds-of-perezhivanie/44165

- Jones, O. (2016, Nov 24). No Asians no Black people. Why do gay people tolerate blatant racism? https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/nov/24/no-asians-no-blacks-gay-people-racism

- Ladders4Action. (2020, Aug 17). Knowledge is power – An open letter to UKRI. https://www.researchprofessionalnews.com/rr-news-uk-views-of-the-uk-2020-8-knowledge-is-power-an-open-letter-to-ukri/

- Lee, R., Ahtone, T., Pearce, M., Goodluck, K., McGhee, G., Leff, C., Lanpher, K., & Salinas, T. (2020). Land-grab universities. https://www.landgrabu.org

- Lee McFarling, U. (2021, Sept 23). ‘Health equity tourists’, how white scholars are colonizing research on health disparities. https://www.statnews.com/2021/09/23/health-equity-tourists-white-scholars-colonizing-health-disparities-research/

- Lopes, R. E., & Malfitano, A. P. S. (2021). Social occupational therapy: Theoretical and practical designs. Elsevier.

- Mignolo, W. D., & Walsh, C. E. (2018). On decoloniality: Concepts, analytics, praxis. Duke University Press.

- Motimele, M. (2022) Engaging with occupational reconstructions: A perspective from the Global South. Journal of Occupational Science, 29(4), 478–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2022.2110659

- Mpofu-Walsh, S. (2023). “SA Constitution must be rewritten”: Race and the law, threats to Black advocates, ANC failures [Video - online interview]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wf1dsV7GTEc&ab_channel=SizweMpofu-Walsh

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2013). Coloniality of power in postcolonial Africa. Myths of decolonization. CODESRIA.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2021). The cognitive empire, politics of knowledge and African intellectual productions: Reflections on struggles for epistemic freedom and resurgence of decolonisation in the twenty-first century. Third World Quarterly, 42(5), 882–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1775487

- Quijano, A. (2000). Coloniality of power and Eurocentrism in Latin America. Nepantla: Views from the South, 1(3), 533–580. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580900015002005

- Ramugondo, E. (2015). Occupational consciousness. Journal of Occupational Science, 22(4), 488–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2015.1042516

- Ramugondo, E. (2018). Healing work: Intersections for decoloniality. WFOT Bulletin, 74 (2), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/14473828.2018.1523981

- Ramugondo. E. (2022). Theorising present struggle. [Video – online presentation for the Johannesburg Institute for Advanced Study]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tvw_OIHROxI&t=960s

- Restall, G., Phenix, A., & Valavaara, K. (2019). Advancing reconciliation in scholarship of occupational therapy and indigenous people’s health. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 86(4), 256–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417419872461

- Simaan, J. (2020a). Decolonising occupational science education through learning activities based on a study from the Global South. Journal of Occupational Science, 27(3), 432–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2020.1780937

- Simaan, J. (2020b). Decolonising the curriculum is an ongoing and collective effort: Responding to Townsend (2020) and Gibson and Farias (2020). Journal of Occupational Science, 27(4), 563–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2020.1827696

- Solaru, T. (2023). An Instagram post by author regarding a situation experienced during the ASPIRE AOTA conference 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CrULhUIMJLr/

- Stonewall. (2018, Jun 27). Racism rife in LGBT community Stonewall research reveals. https://www.stonewall.org.uk/cy/node/79551

- Swedberg, R. (2012). Theorizing in sociology and social science: Turning to context of discovery. Theory and Society, 41(1), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-011-9161-5

- Tikly, L., & Barrett, A. M. (2011). Social justice, capabilities and the quality of education in low income countries. International Journal of Educational Development, 31(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2010.06.001.

- Townsend, E. (2020). Commentary on decolonising occupational science education through learning activities based on a study from the Global South (Simaan, 2020). Journal of Occupational Science, 27(3), 443–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2020.1793447

- Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), 1–40. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/issue/view/1234

- Wilkinson, R., & Zou’bi, S. (2021, Jun 23). Decolonising the Curriculum Interview Series – Leon Tikly podcast and transcript. https://bilt.online/decolonising-the-curriculum-interview-series-leon-tikly-podcast-and-transcript/

- Wilson, W. A., & Bird, M. Y. (2005). For Indigenous eyes only: Beginning decolonization. School for Advanced Research.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2018). Health inequities and their causes. https://www.who.int/news-room/facts-in-pictures/detail/health-inequities-and-their-causes