ABSTRACT

For children, playing outdoors is a meaningful occupation, and such play is enabled by outdoor playgrounds. As play is a fundamental right for every child, Universal Design is an approach to creating inclusive playgrounds that welcome all children. Yet, research investigating how the physical environment of a playground supports children’s play needs, in terms of play value and inclusion, is largely absent. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate how children’s experiences of the environmental characteristics of outdoor playgrounds add to the understanding of play value and inclusion from a child-centred perspective. Using a meta-ethnography approach, a systematic review of qualitative evidence was conducted, which included 17 studies. The study identified two themes. Theme one describes the understanding of play value from the children’s view, which includes their experiencing and mastering of challenges, creating and shaping of the physical environment, social experiences of playing with or alongside other children, and sense of belonging felt from the welcoming playground atmosphere. Theme two describes how the design of the physical environment of a playground in the sense of the variety of spaces and places, and the variability of designed and non-designed elements, influences play value and inclusion. The line of argument synthesis describes the interrelationship between the physical (variety and variability) and the social environment (inclusion) characteristics of the playground through the socio-spatial element of play value. This study identified the interrelated elements contributing to high play value, and consequently place-making, which can contribute to the understanding of inclusive design for playgrounds.

Play is a universal right of every child (United Nations, Citation1989) and a core occupation in childhood (Lynch & Moore, Citation2016; Parham, Citation2008). From an occupational science perspective, children have told us how play and places for play are important in their lives and contribute to their happiness and well-being (Moore & Lynch, Citation2018). Outdoor playgrounds are environments specifically built with the intention to provide a place for children to play and can thus be seen as supporting children’s right to play. Playgrounds are often located in communities, for example in parks, schools, and preschools, and they feature play equipment of various kinds (Burke, Citation2013; Lee et al., Citation2022; Woolley & Lowe, Citation2013). The significant role of playgrounds in children’s lives is reflected in the meaning they ascribe to outdoor play (Miller & Kuhaneck, Citation2008; Moore & Lynch, Citation2018; van Heel et al., Citation2022), which demonstrates the interconnection between occupations and the environments that enable them (Hocking, Citation2009). Van Heel et al.’s (Citation2022) investigation of children’s drawings in relation to outdoor play places revealed playgrounds as their favourite places. The children indicated that the experience of fun was the most important reason for this preference, followed by the variety of occupations, experiences, and social interactions with other children that playgrounds offer them (Moore & Lynch, Citation2018; van Heel et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, studies have revealed that for children, play is characterised by opportunities for challenge and mastery, its flexibility to happen anywhere and with everything or everyone, and the chance to interact with friends (Brussoni et al., Citation2020; Miller & Kuhaneck, Citation2008; Moore & Lynch, Citation2018; Morgenthaler et al., Citation2023). Thus, it can be concluded that playgrounds should provide the experience of fun, social interaction, challenge, and a variety of occupations to meet children’s play needs. These elements can be combined into the concept of play value.

The term ‘play value’ (Woolley & Lowe, Citation2013) has been established in recent playground research (Lynch et al., Citation2020; Parker & Al-Maiyah, Citation2021). Play value refers to the meaning children derive while playing, that is, the richness of the play experience children have in a particular environment (Yuen, Citation2016). Playgrounds that are characterised by high play value offer many different ways for children with different abilities to engage in play (Casey & Harbottle, Citation2018; Children’s Play Policy Forum & UK Play Safety, Citation2022; Parker & Al-Maiyah, Citation2021; Yuen, Citation2016) and thus “maximise fun experiences” (Lynch et al., Citation2018, p. 20). Yet, little is known to date about which environmental characteristics should be considered in the design of playgrounds that are high in play value to meet the play needs for all children.

One design approach that considers both physical and social characteristics, with the aim of creating inclusive environments that can be used by everyone without the need for special adaptations, is Universal Design (UD) (Mace, Citation1985; Steinfeld et al., Citation2012). In relation to children’s play, UD has been anchored at the policy level for the design of inclusive playgrounds, that are both accessible and usable (European Standards, Citation2021; United Nations, Citation2006, Citation2013). Inclusive playgrounds aim to be places that provide equal opportunities for children of different ages, abilities, and backgrounds to engage in play and social occupations (Children's Play Policy Forum & UK Play Safety, Citation2022; Fernelius & Christensen, Citation2017; Moore et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, inclusive playgrounds aim to offer an environment where everyone feels welcome (Casey & Harbottle, Citation2018). An investigation of children’s perspectives on inclusion in outdoor leisure settings identified feeling welcome, experiencing equality, and having a sense of belonging as the central elements (Edwards et al., Citation2021). Therefore, UD and design for inclusion means going beyond accessibility and usability, to design places for play that are high in play value, and in the end, are welcoming and support the sense of belonging.

However, to our knowledge, no research to date has investigated the association between playground design and play value through an analysis of children’s play experiences in playgrounds. From an inclusive design perspective, these aspects should be enabled through the physical and social environment. This raises the key question of how the emotional experience of belonging can be enabled by the design of the environment. Probyn (Citation1996) described belonging as “some sort of attachment to people, places, modes of being, a process that develops” (p. 19). The term ‘place-attachment’ (synonymous with place making, place-making, or topophilia) describes the emotional bond people develop in relation to certain places, which is affected by their physical and social environment (Akbar & Edelenbos, Citation2021; Altman & Low, Citation1992). The notion of place-attachment originated from urban design, where the focus was on the physical environment, and was further developed by other disciplines, such as sociology and human geography, which added the social dimension and the idea that a dynamic relationship between the physical and social aspects of an environment is central in creating (socially) meaningful places (Akbar & Edelenbos, Citation2021; Manzo & Devine-Wright, Citation2020). The centrality of occupations in transforming physical places into socially meaningful place-attachments has been discussed within occupational science (Delaisse et al., Citation2020; Huot & Laliberte Rudman, Citation2010; Johansson et al., Citation2013; Manuel, Citation2003; Rowles, Citation2008; Zemke, Citation2004). Researchers in the field agree that a space becomes a meaningful place through the occupations people engage in and the social interactions with others. Yet, in occupational science, studies on place-attachment have primarily focused on adulthood rather than childhood (Hand et al., Citation2023; Heatwole Shank & Cutchin, Citation2010; Shaw, Citation2009).

In relation to children’s play experiences, several studies in occupational science have acknowledged the influence of environmental characteristics (Fahy et al., Citation2021; Gerlach et al., Citation2014; Gerlach & Browne, Citation2021; Lynch et al., Citation2016; Moore & Lynch, Citation2018; van Schalkwyk et al., Citation2019). However, only two of these studies have investigated children’s play experiences in relation to playgrounds, and neither has explored the influence of the environment on play value and inclusion. This indicates the need to synthesise the research from other fields that are looking at playgrounds from the perspective of children and to view them through an occupational science lens. As children are the experts in their play occupations, and in line with their right to be heard, their views should be considered when aiming to design a meaningful and inclusive playground (United Nations, Citation1989, Citation2013). Therefore, this study aimed to expand the knowledge, from a child-centred perspective, of how environmental characteristics influence play value and inclusion for all children in outdoor playgrounds. The research question was: How do children’s experiences of environmental characteristics in outdoor playgrounds add to the understanding of play value and inclusion from a child-centred perspective?

Methods

Design

A meta-ethnography was conducted to systematically collect children’s experiences in outdoor playgrounds in relation to play value and inclusion, following the methodology described by Noblit and Hare (Cahill et al., Citation2018; Noblit & Hare, Citation1988). The steps of the meta-ethnography approach used follow the eMERGe reporting guidance by France et al. (Citation2019), as it provides clear advice for reporting and methodology. In addition the consultation of the guide of Cahill et al. (Citation2018) was useful for additional guidance on methodology. The study protocol is published on PROSPERO under the number CRD42021268705 (Wenger, Lynch et al., Citation2021).

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted with the intention to include all relevant studies that investigated children’s experiences of playing in outdoor playgrounds. The search terms were derived from the research question and key studies on the topic of interest. The search strategy was developed and tested following consultation with a university librarian in July 2021 and consisted of the three search blocks (see ) of outdoor play, children, and perspective. The search blocks were connected with the Boolean operator AND, and were composed according to the SPIDER search strategy tool (Cooke et al., Citation2012).

Table 1. Search query.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All the studies were peer-reviewed articles published in English, because English was the common language of the authors, who were from different countries across Europe. No limits were set for years of publication or geographical locations. The inclusion criteria were studies of children aged 0–12 years in relation to outdoor play in specific play spaces (e.g., in parks or school playgrounds), which focused on environmental aspects, such as natural or social environments, and had in the foreground children’s perspectives about the play spaces. Studies were excluded if they focused on play in digital/virtual spaces, play as a physical activity or sports, quantitative methods, literature reviews, or qualitative studies informed by questionnaires.

Search process and study selection

The literature search was conducted in August 2021 on the databases AMED, Avery Index, CINAHL, Emcare, Eric, Medline, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Web of Science. These databases were selected because they cover the fields of health, education, architecture, and the social sciences and humanities, all fields considered relevant to the research question ().

Table 2. Overview of searched databases.

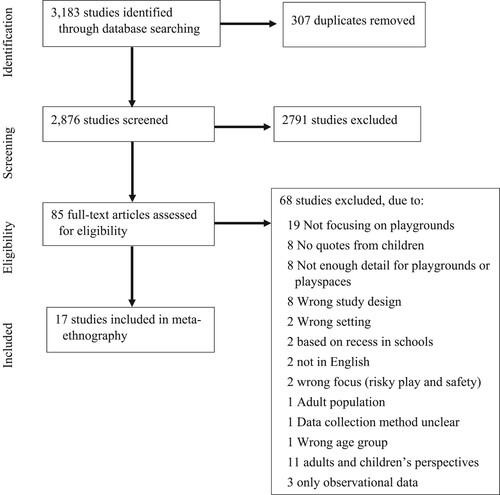

The literature search was conducted by the primary author, and resulted in 3,183 studies, which were then imported into the Covidence tool for abstract screening (https://www.covidence.org). After the duplicates were removed, 2,876 studies remained. The abstracts of all the studies were screened by two persons (the primary author and one of the co-authors) according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. If they disagreed, a third person (one of the co-authors) resolved the conflict. Finally, 85 studies remained for full-text eligibility. For the final selection of the full texts, a purposive strategy was applied, with the aim of theoretical saturation (Booth, Citation2001, Citation2016). Therefore, some additional inclusion and exclusion criteria were added to focus more specifically on the research question and to specifically highlight the children’s voices. Studies that included the perspectives of adults, such as parents or teachers, or studies applying methods that did not directly represent children’s voices (e.g., observational studies using methods of mapping or counting the presence of children) were excluded. The full texts were then reviewed for these additional inclusion and exclusion criteria by two members of the research team (primary author and one co-author). When disagreement occurred, the opinion of another co-author was sought and, if necessary, discussed by the entire research team. Finally, the full-text eligibility resulted in the inclusion of 17 studies. provides an overview of the different inclusion and exclusion criteria that were applied for the study selection (see for the different phases of the search process).`

Table 3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for study selection.

Quality appraisal

A consensus has been established in the literature that the quality of studies included in a qualitative evidence synthesis should be assessed (Garside, Citation2014). For quality appraisal of the 17 included studies, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP; https://casp-uk.net), one of the most used checklists for the quality assessment of qualitative studies (Dalton et al., Citation2017), was used. Quality was appraised by two persons (Garside, Citation2014), whereby each rated each study independently and solved items of disagreement through discussion (see ). Studies were allocated so that at least one person who was not a co-author of the study being assessed was involved in assessing it. In line with Atkins et al. (Citation2008), we decided not to exclude any study based on the CASP results, as the content of the study could be valuable for the overall synthesis.

Table 4. Quality appraisal of included studies with the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP).

After completion of the process of synthesising the data of the studies, the GRADE-CERQual (Confidence in Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research) assessment was conducted by all authors (Lewin et al., Citation2018). The GRADE-CERQual integrated the results of the CASP into the assessment of methodological limitations, and it assessed coherence, adequacy of data, and relevance of the primary studies in relation to the review findings and overall aim of the meta-ethnography (see for a summary of the qualitative findings and details on the assessment of confidence).

Table 5. Summary of Qualitative Findings.

Data extraction and data synthesis

Following the seven steps of Noblit and Hare (Citation1988), the first phase involved reading the studies and extracting and synthesising the data in an iterative process that involved all the authors. All studies were read several times by all authors. Descriptive information about the studies was extracted into a data extraction form modelled on Toye et al. (Citation2014) including information about the aim, purpose, method, data collection methods, age of participants, gender, disability, socio-economic background, study context, natural elements, and inclusion. Few of the studies reported the ethnicity of participants.

Concepts that “explain not just describe the data” (Toye et al., Citation2013, p. 5) were compared across the studies in relation to play value, the factors contributing to inclusion, the occupations of children in play spaces, and the places where these take place, following the constant comparative approach of Toye et al. (Citation2014). Information about the background of the children (e.g., age group, gender, socio-economic background, disability status) was integrated into the analysis. Reflexive notes were made regularly by the first author, as suggested by Doyle (2003, as cited in Cahill et al., Citation2018), while reading the studies and extracting and synthesising the data.

The key concepts of the studies were extracted following Noblit and Hare (Citation1988), who recommend “repeated reading of the accounts and the noting of interpretative metaphors” (p. 3) (also known as themes). In the process of this repeated reading, the identified concepts were mapped by a short summary and the respective first- and second-order constructs informing the concepts (Sattar et al., Citation2021; Toye et al., Citation2014). First-order constructs are study concepts emerging from the participants’ quotes, in this case the children’s voices (Toye et al., Citation2014). Second-order constructs are derived from the interpretation of the participant data by the authors of the primary studies (Toye et al., Citation2014). Also, verbatim data of the studies were extracted and imported into the data analysis software Atlas.ti (Cahill et al., Citation2018; Toye et al., Citation2014). This was done in line with the recommendation of Sattar et al. (Citation2021) to “preserve the original terminology used by the primary authors” and to “avoid the risk of losing important data” (p. 5). The data extraction and comparison revealed that the different studies were complementary, which led to a reciprocal synthesis that was incorporated into the line of argument synthesis.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

The publication years ranged from 2007 to 2021, with most studies published between 2016 and 2021. gives a detailed overview of the characteristics of the 17 included studies, which are described below. Just over half of the studies were conducted in various European countries (10), while the other studies were conducted in Australia (4), Asia (2), and Africa (1). School playgrounds/school yards (9) were the most commonly included playground settings, followed by community play spaces (5) and community playgrounds (4). Most of the study participants lived in an urban setting.

Table 6. Characteristics of included studies.

In total, the studies included 594 children (one study did not specify the sample). Most studies captured the perspectives of primary school-aged children (6–12 years), with some studies only looking at preschool children (4–5 years) or at children in both age groups. All studies included either a mixed sample of boys and girls or did not specify the gender of the participants, except for one study that specifically looked at the perceptions of girls. Four studies included children with various types of disabilities (e.g., autism spectrum disorder, physical or intellectual disabilities), and five studies included children with a low socio-economic background. In the findings, we generally refer to all the children just as children. Only if the findings revealed differences according to the children’s background was this specifically mentioned. The studies used a variety of child-centred qualitative methods to capture the children’s perspectives.

Synthesis of review findings

Through the analysis, the importance of considering the children’s perspectives became evident, as they are the experts in their own play (Caro et al., Citation2016; Yates & Oates, Citation2019). For example, the studies that included children with disabilities described that the play of these children can be misinterpreted from an adult perspective (Burke, Citation2012; Wenger, Schulze et al., Citation2021).

shows the themes and subthemes that resulted from the translations of the first- and second-order constructs. The first theme, “You‘ve got to have fun in the playground” – Characteristics of play value from children’s perspectives, describes the meaning of play value from their viewpoint. The second theme, “With more possibilities, it is easier to play” – Designing with variety and variability in mind to create inclusive play spaces for all children, explores the centrality of variability in designing for inclusion and play value.

Theme 1: “You‘ve got to have fun in the playground”: Characteristics of play value from children’s perspectives

This theme describes the understanding of play value from the children’s perspectives. The analysis showed that for children, play value is characterised by the things they do in playgrounds and the meanings that arise from these doings afforded by the playground environment. In other words, from the children’s perspectives, play value includes the elements of challenge, creativity, and playing with or alongside other children. These characteristics of play value are described in the subthemes experiencing and mastering challenges means excitement and achievement, creating and shaping the physical environment, and playing with or alongside other children – the experience of inclusion and equality. Furthermore, from the data, characteristics of the physical and social environment, such as access, maintenance, and rules were identified as affecting play value and inclusion and are described in the subtheme thinking beyond play – characteristics that create a welcoming atmosphere for play. If a playground provides these experiences, it enables meaningful play experiences for children, such as fun and happiness (Agha et al., Citation2019; Bartie et al., Citation2016; Caro et al., Citation2016; Saragih & Tedja, Citation2017). The theme and subthemes were informed by 17 out of the 17 studies (see ).

Experiencing and mastering challenges means excitement and achievement

The analysis showed that children associate play value with challenge. The experience of challenge was associated with intense feelings, such as excitement, and the experience of mastering challenges was related to the sense of achievement and self-esteem children had from playing games or excelling in play occupations such as climbing or sliding (Almers et al., Citation2020; Bartie et al., Citation2016; Burke, Citation2012; Caro et al., Citation2016; Fahy et al., Citation2021; Jansson, Citation2015; Prellwitz & Skär, Citation2007; Prompona et al., Citation2020; Wenger, Schulze et al., Citation2021; Yates & Oates, Citation2019). The following quote from a child illustrates how she and her peers experienced challenges by doing competitions: “All competitions and so on. … For example, we can jump on a trampoline, then you have to try to jump really high for example. … Who can run the fastest? And then you have to jump over the sandpit” (Caro et al., Citation2016, p. 7). It can be assumed that the meaning challenge has for children is reflected in their desire to experience and master new challenges. The analysis showed that challenges arise from both the physical and the social environment.

In the physical environment, children identified the combination of natural elements (e.g., trees, branches, stones, cones, etc.), the playground equipment, and the different landscape shapes as characteristics contributing to challenge (Almers et al., Citation2020; Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Caro et al., Citation2016; Jansson et al., Citation2016; Moore et al., Citation2021; Pawolowski et al., Citation2019; Yates & Oates, Citation2019), for example through experiencing heights and/or speed when climbing, running, or sliding (Caro et al., Citation2016; Fahy et al., Citation2021), using equipment they haven’t used before, discovering new ways of using equipment (Prellwitz & Skär, Citation2007), or using equipment in innovative ways that were not intended by the adults who built the playground or supervised them (Almers et al., Citation2020; Jansson, Citation2015; Moore et al., Citation2021; Saragih & Tedja, Citation2017; Yates & Oates, Citation2019). The following quote is an example of such an innovative use of equipment by children: “Almost everybody tries to hang by the knees. I know we are not supposed to, but it is fun and scary” (Prellwitz & Skär, Citation2007, p. 149).

In the social environment, challenges were afforded, for example, in making fun of adults (Prompona et al., Citation2020) or in measuring each other’s skills through competition (Caro et al., Citation2016; Prompona et al., Citation2020; Wenger, Schulze, et al., Citation2021). As one of the children put it, “We are outlaws for sure (laughter). Since you (teachers) keep saying no to everything during recess, we said we would do something that we really like even if it is forbidden” (Prompona et al., Citation2020, p. 772).

Creating and shaping the physical environment

For children, the characteristic of creating and shaping the physical environment of a playground, including the built and natural elements, was experienced through transforming the play space through their imagination into their own places or worlds (Agha et al., Citation2019; Almers et al., Citation2020; Burke, Citation2012; Fahy et al., Citation2021; Moore et al., Citation2021; Prellwitz & Skär, Citation2007; Prompona et al., Citation2020; Saragih & Tedja, Citation2017; Yates & Oates, Citation2019), such as in creating dens or hide-outs (Almers et al., Citation2020; Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Bartie et al., Citation2016; Jansson, Citation2015; Moore et al., Citation2021). Another way of ‘creating and shaping’ involved children integrating the elements of the physical environment into their play by coming up with their own games, such as playing catch, using the playground equipment as shields, or inventing a game where they could not be caught if they were on specific playground equipment (Agha et al., Citation2019; Bartie et al., Citation2016; Fahy et al., Citation2021). The quote shows an example of how the children developed a game by integrating the slide into their play: “On the big slide we play crocodile, you try to climb up but the crocodile pulls you down” (Prellwitz & Skär, Citation2007, p. 150).

Children associated ‘creating and shaping’ with positive feelings, such as enjoyment, satisfaction, happiness, coziness, and safety, as well as the excitement of exploring new spaces for play that allowed for freedom or adventure (Burke, Citation2012; Jansson et al., Citation2016; Prompona et al., Citation2020; Saragih & Tedja, Citation2017). Overall, the analysis showed that through ‘creating and shaping’, the children experienced self-confidence and self-determination that was expressed through agency; control over themselves, the environment, or adults; and a sense of privacy (Agha et al., Citation2019; Bartie et al., Citation2016; Moore et al., Citation2021; Prellwitz & Skär, Citation2007; Prompona et al., Citation2020; Yates & Oates, Citation2019).

These feelings were in contrast with the boredom children sometimes experienced on playgrounds that did not allow for creating and shaping (Caro et al., Citation2016; Jansson, Citation2015; Saragih & Tedja, Citation2017) and were limited to ‘mundane doing and using’, thus leading to a limited sense of belonging and attachment to the place (Moore et al., Citation2021). From the children’s descriptions of the process of creating and shaping in the playground, it became evident that this is one way in which children ‘make’ places, and through this process, attachments to places are created that contribute to a sense of belonging.

Playing with or alongside other children – experience of inclusion and equality

The children described that, for them, the meaning of playing with or alongside other children was that they developed a sense of belonging to a group or peer culture, which can be expressed, for example, by using special codes or sharing commonalities (Bartie et al., Citation2016; Moore et al., Citation2021; Prompona et al., Citation2020; Wenger, Schulze et al., Citation2021).

From the studies, it was evident that a playground is an important social environment in which to meet and play with or alongside other children (Agha et al., Citation2019; Bartie et al., Citation2016; Burke, Citation2012; Caro et al., Citation2016; Fahy et al., Citation2021; Jansson, Citation2015; Jansson et al., Citation2016; Ndhlovu & Varea, Citation2018; Prellwitz & Skär, Citation2007; Prompona et al., Citation2020; Saragih & Tedja, Citation2017). One child described it like this: “It is really fun. You have a lot of people, and it is … a cosy place. Here you can have fun together” (Jansson et al., Citation2016, p. 232). No evidence was found that children preferred to play far away from other children. Rather, the children specified that they prefer to play with children they know, such as friends, over strangers (Caro et al., Citation2016; Wenger, Schulze et al., Citation2021). Also, meeting friends, making new friends, or even ending friendships were described (Prellwitz & Skär, Citation2007; Prompona et al., Citation2020).

The importance of the social environment in playgrounds was particularly highlighted by the studies that included children with disabilities. The analysis of these studies showed that children with disabilities undertake specific efforts and strategies to participate in social activities on playgrounds (Burke, Citation2012; Prellwitz & Skär, Citation2007). The strategies included their identifying the popular physical spaces where social occupations take place and doing everything to be in these spaces (Burke, Citation2012; Prellwitz & Skär, Citation2007), or starting a conversation with other children in a certain place as a way to participate in the social experience (Burke, Citation2012). However, the studies also showed that not all children with disabilities had access to these social occupations and thus the experience of belonging (Prellwitz & Skär, Citation2007; Wenger, Schulze et al., Citation2021) as the following quote of a child with a physical disability illustrates: “They don’t want to make friends with us, that’s the problem!” (Wenger, Schulze et al., Citation2021, p. 140).

Thinking beyond play – characteristics that create a welcoming atmosphere for play and belonging

Children identified characteristics from the physical and social environment that contribute to a welcoming atmosphere and overall feeling of belonging on playgrounds that reflect play value and inclusion. From the analysis, it became clear that the involvement of children in the planning of playgrounds is of central importance in order to learn about children’s needs that go beyond the actual playground equipment, such as access, maintenance, and rules, and how these are related to play value and inclusion (Burke, Citation2012; Caro et al., Citation2016; Jansson et al., Citation2016; Ndhlovu & Varea, Citation2018; Wenger, Schulze et al., Citation2021; Yates & Oates, Citation2019).

In the physical environment, access to the playground was identified as one characteristic. One child said: “We don’t want to go far away” (Pawolowski et al., Citation2019, p. 5). If a playground was located too far away, children felt excluded, which was especially expressed by girls (Pawolowski et al., Citation2019) and children with visual impairments (Prellwitz & Skär, Citation2007). Children preferred to get to the playground by themselves if possible (Agha et al., Citation2019; Caro et al., Citation2016; Jansson, Citation2015; Jansson et al., Citation2016; Pawolowski et al., Citation2019), and thus favoured playgrounds in close proximity to where they live. Having access to playgrounds was thus identified as a pre-requisite for play value and inclusion in several studies (Agha et al., Citation2019; Caro et al., Citation2016; Jansson, Citation2015; Jansson et al., Citation2016; Pawolowski et al., Citation2019; Prellwitz & Skär, Citation2007).

Another important characteristic of the physical environment was the level of maintenance of a playground, which was described by the children as affecting their feelings, play behaviours, and quality of stay (Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Caro et al., Citation2016; Jansson et al., Citation2016; Moore et al., Citation2021; Pawolowski et al., Citation2019). For example, children preferred less maintained places in natural environments because of their abandoned appearance, which afforded them a feeling of adventure (Jansson et al., Citation2016). Yet, the children also described how playgrounds that contained dirty or broken playground equipment or neglected natural environments provoked a sense of fear or dangerous behaviour, as the children continued to use the broken equipment because they want to play (Agha et al., Citation2019; Caro et al., Citation2016; Jansson et al., Citation2016; Moore et al., Citation2021). Thus, a neglected playground negatively impacted the overall play value and feeling of belonging.

Children were also aware of the hazards on playgrounds, as evident in several studies (Almers et al., Citation2020; Bartie et al., Citation2016; Ndhlovu & Varea, Citation2018; Yates & Oates, Citation2019). In one study a child said: “It’s dangerous at the pebbles, you can’t run on there, you could easily fall, one day a girl in our class fell and started bleeding” (Ndhlovu & Varea, Citation2018, p. 499). Children applied strategies to minimise the hazards, which were related to the physical and social environment, such as suggesting the provision of soft surfaces or fences around playgrounds; taking responsibility for themselves and younger children (Bartie et al., Citation2016), for example through identifying the potential sources of hazards, such as traffic or wood splinters (Caro et al., Citation2016); and recognising the need for rules on playgrounds (Caro et al., Citation2016). In relation to the social environment, children especially suggested having rules on playgrounds concerning social interaction and inclusion, such as no bullying, kicking, or hitting, and the equality of boys and girls and older and younger children (Caro et al., Citation2016). Yet, children also highlighted that rules should be applied with consistency and communicated in a friendly way, and that supervisors should be attentive and allow for risky play experiences to contribute to their comfort, play value, and inclusion on playgrounds (Agha et al., Citation2019; Almers et al., Citation2020; Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Caro et al., Citation2016; Fahy et al., Citation2021; Ndhlovu & Varea, Citation2018; Saragih & Tedja, Citation2017).

This theme shows that from the children’s perspectives, a playground should provide the characteristics that allow them to experience challenge, to shape and create, and to play with or alongside other children, all of which contribute to their play value. These characteristics can be afforded through elements of the physical environment, such as the playground equipment and loose parts (including natural elements like stones, tree branches, leaves, etc.), which create social meeting places and a welcoming atmosphere, thus contributing to an overall feeling of belonging. Loose parts have been defined by Lee et al. (Citation2022) as:

Natural or manufactured materials with no specific set of directions that can be used alone or combined with other materials, moved, carried, combined, redesigned, lined up, and taken apart and put back together in multiple ways and used for play. (p. 12)

Theme 2: “With more possibilities, it is easier to play” - Designing with variety and variability in mind to create inclusive play spaces for all children

This theme identifies variety as a central characteristic of playgrounds, and its influence on play value and inclusion is described by two subthemes. The first subtheme, variety of spaces and places, describes how a variety of spaces, such as open spaces and in-between places, contributes to inclusion and play value by providing different play situations. The second subtheme, variability of designed and non-designed elements: Enabling a variety of experiences, describes how the variability of designed and non-designed (play) features affords a variety of uses by children and, in that sense, contributes to play value and inclusion.

The following quote from a conversation about a play space in a natural environment illustrates how a variety of play opportunities within one place and an overall variability of places contributes to play value:

Girl: I think that this type of place is more fun … because here I think that you can do so much more still … it is just to come up with things to do. It is usually so that always when I am with friends and that we usually make up games instead of taking what you already know of.

Interviewer: But why is it easier to do that here than in an ordinary playground?

Girl: I think there are mainly built things and it is usually mostly swings and such things and when you have been to a playground […] very many times so it is a bit boring. But when you come to a forest you have for example been to one place and then you go further out and then end up in another place all of a sudden. (Jansson et al., Citation2016, p. 233)

The theme and subthemes were informed by 15 out of the 17 studies (see ).

Variety of spaces and places

The analysis showed that providing a variety of spaces in a playground, such as in-between places and open spaces, is an important characteristic contributing to inclusion and play value. Through the analysis, it was found that having enough space to play contributes to inclusion. For example, a large space provides room for physically active play, such as running around or playing football, and it thereby provides opportunities for larger groups of children to play together and for children of different ages to be in the same space (Almers et al., Citation2020; Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Caro et al., Citation2016; Fahy et al., Citation2021; Jansson et al., Citation2016; Ndhlovu & Varea, Citation2018; Pawolowski et al., Citation2019; Prellwitz & Skär, Citation2007). However, the children also described how they sometimes were negatively affected by the characteristics of an open space, such as the surface material (Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Caro et al., Citation2016; Moore et al., Citation2021; Ndhlovu & Varea, Citation2018; Pawolowski et al., Citation2019; Saragih & Tedja, Citation2017); the domination of the space by boys’ rough behaviour, for example while playing football (Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Caro et al., Citation2016; Ndhlovu & Varea, Citation2018; Pawolowski et al., Citation2019); the crowdedness (Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Pawolowski et al., Citation2019); the noise (Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Fahy et al., Citation2021; Moore et al., Citation2021; Pawolowski et al., Citation2019); the lack of privacy (Agha et al., Citation2019; Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Caro et al., Citation2016; Fahy et al., Citation2021; Moore et al., Citation2021; Pawolowski et al., Citation2019; Prellwitz & Skär, Citation2007), and the dirtiness or messiness (Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Caro et al., Citation2016; Jansson et al., Citation2016; Pawolowski et al., Citation2019). These characteristics could lead to “moping and messing around” (Caro et al., Citation2016, p. 7), restless play (Fahy et al., Citation2021; Moore et al., Citation2021), sadness (Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Caro et al., Citation2016; Fahy et al., Citation2021; Moore et al., Citation2021; Ndhlovu & Varea, Citation2018; Pawolowski et al., Citation2019), or a complete withdrawal from the play space, which was especially identified in girls (Pawolowski et al., Citation2019) and younger children (Caro et al., Citation2016; Ndhlovu & Varea, Citation2018). Therefore, the children described the need for different places, such as in-between places.

In-between places are located between, on the sidelines or in the corners of the main play areas, such as the open spaces (Aminpour et al., Citation2020), or between the play equipment and the natural elements, such as bushes or trees (Almers et al., Citation2020; Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Moore et al., Citation2021). In contrast to open spaces, in-between places were characterised as being less crowded, more peaceful, and cozier overall (Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Fahy et al., Citation2021; Moore et al., Citation2021; Pawolowski et al., Citation2019). Also, the children experienced in-between places as more private in the sense of offering some control over who enters the space (Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Pawolowski et al., Citation2019), being out of adults’ sight, being among friends, or being on their own (Agha et al., Citation2019; Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Caro et al., Citation2016; Fahy et al., Citation2021; Moore et al., Citation2021; Pawolowski et al., Citation2019; Prellwitz & Skär, Citation2007). One child explained his preference for in-between places like this: “It’s kind of fun to play here … because it’s a kind of secret area. Teachers don’t normally check there” (Aminpour et al., Citation2020, p. 13).

In relation to inclusion, the studies showed that in-between places are, due to their quiet nature and shielded location, of special importance for the inclusion of especially preschool children (Moore et al., Citation2021), children with disabilities (Fahy et al., Citation2021; Prellwitz, & Skär, Citation2007), and girls (Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Ndhlovu & Varea, Citation2018; Pawlowski et al., Citation2019). In terms of play value, a (larger) open space was identified as providing more active play (Almers et al., Citation2020; Fahy et al., Citation2021; Pawlowski et al., Citation2019), whereas in-between places offered children a variety of occupations, mainly of a social and creative nature, such as relaxing with friends or building hiding places (see ).

Table 7. Relation of environmental characteristics to occupations, meanings, play value and inclusion.

Variability of designed and non-designed elements: Enabling a variety of experiences

The analysis showed that for children, a variety of designed features, and variability of choices for play are central environmental characteristics in enabling play value and inclusion (Caro et al., Citation2016; Fahy et al., Citation2021; Jansson, Citation2015; Jansson et al., Citation2016; Yates & Oates, Citation2019). In terms of variety, this was evident in examples such as built playground equipment, surfaces, and materials, and non-designed features, such as loose parts (e.g., chalks, tubes, sport material, dresses, speakers), including natural elements. The studies identified that a variety of experiences can be provided in various ways, for example by enabling children to do the same occupations in different ways according to their abilities and preferences (e.g., climbing a tree, climbing from a sitting position, or climbing by watching how others climb) (Prellwitz & Skär, Citation2007; Wenger, Schulze et al., Citation2021). In this way, children are provided with opportunities for equal experiences.

Another aspect of variety was identified as playground equipment that can be used by several children together and that provides different experiences (e.g., challenges, privacy, and social interactions) through the multiple ways it can be used, such as multiplayer swings (Almers et al., Citation2020; Prellwitz & Skär, Citation2007; Yates & Oates, Citation2019). Another example was identified as loose parts (Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Bartie et al., Citation2016; Caro et al., Citation2016; Jansson et al., Citation2016; Moore et al., Citation2021; Pawolowski et al., Citation2019; Yates & Oates, Citation2019), and the different ways children can use these adds fun and play value for them (Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Caro et al., Citation2016; Pawolowski et al., Citation2019; Yates & Oates, Citation2019).

Also, the natural environments of playgrounds create a variety of play possibilities, such as in-between places, or the possibility of creating one’s own place (Almers et al., Citation2020; Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Jansson, Citation2015; Jansson et al., Citation2016; Moore et al., Citation2021; Pawolowski et al., Citation2019), thus adding play value (Agha et al., Citation2019; Almers et al., Citation2020; Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Caro et al., Citation2016; Fahy et al., Citation2021; Jansson et al., Citation2016; Moore et al., Citation2021; Pawolowski et al., Citation2019; Yates & Oates, Citation2019). The following quote illustrates how a tree can add play value: “I come here to cool down … under the peppermint gumtree … This is my favourite spot … because it’s shady and under the leaves … it’s fun when it’s bushy cos we can hide” (Moore et al., Citation2021, p. 948). Children experienced the natural environments as adding to their well-being and perceived them as beautiful, cosy, and relaxing (Aminpour et al., Citation2020; Caro et al., Citation2016; Jansson et al., Citation2016; Moore et al., Citation2021; Pawolowski et al., Citation2019). Interestingly, studies that included children with disabilities did not mention natural environments.

In terms of inclusion, variability was related to the provision of enough equipment so that everyone can find a place to play (Caro et al., Citation2016; Fahy et al., Citation2021; Jansson, Citation2015; Jansson et al., Citation2016; Yates & Oates, Citation2019), the many ways of using the equipment by children of different ages, sizes, and abilities (Almers et al., Citation2020; Caro et al., Citation2016; Ndhlovu & Varea, Citation2018; Prellwitz & Skär, Citation2007; Wenger, Schulze et al., Citation2021; Yates & Oates, Citation2019), and the type of material used in the playground equipment, with a preference for natural and colourful materials (Caro et al., Citation2016; Yates & Oates, Citation2019). Therefore, enabling a variety of experiences combined with variability, was identified as a central characteristic of inclusion.

In summary, this theme shows how the variety and variability of spaces, open and in-between, are perceived by children as characteristics contributing to inclusion and play value by providing play opportunities that meet children’s different needs. Furthermore, the characteristic of variability of the designed and non-designed elements within these places and spaces contributes to inclusion and play value by enabling a variety of play experiences.

Line of argument synthesis

The themes described above were further abstracted into a line of argument synthesis. The process of building this synthesis involved all the authors and was informed by team discussions and visualisations aimed at depicting the overarching meaning of the themes (Cahill et al., Citation2018; Noblit & Hare, Citation1988). The discussions resulted in the metaphor of a seesaw that, depending on whether it is surrounded by a physical environment characterised by variety and variability, shifts towards more or less play value (see ). If the physical environment shows greater variety and variability, the seesaw shifts towards more play value, indicating that children find more opportunities to experience challenge, to create and shape the environment, and to play with or alongside other children in a welcoming atmosphere, all of which leads to more inclusion.

Variety and variability are part of the physical environment and refer to a mix of places and spaces on a playground, as well as the availability of different materials, such as loose parts, including natural elements and playground equipment that can be used in many ways. Inclusion forms part of the social environment and includes equity of experiences, contributing to the feeling of belonging and being welcome on the playground. Play value connects the physical and social environment and can therefore be seen as situated in the socio-spatial environment. From the children’s perspectives, play value can be understood as the occupations and experiences that make a playground meaningful for children. Some aspects of play value relate to characteristics afforded by the physical environment that create opportunities for challenge and allow children to create and shape the environment. Other aspects, such as playing with or alongside other children and experiencing a welcoming atmosphere, are strongly related to the social environment and contribute to the feeling of inclusion. Yet, factors of both the physical and social environment contribute to the creation of a welcoming atmosphere and the feeling of belonging, which illustrates the interconnectedness of the physical and social environment and their mutual importance in terms of inclusion.

Discussion

This meta-ethnographic study aimed to expand knowledge, from a child-centred perspective, on how environmental characteristics influence play value and inclusion for all children on outdoor playgrounds. The overall findings contribute to the understanding of play value from children’s perspectives and illustrate the complex interplay of the physical and social environments on playgrounds. Play value is influenced by the characteristics of the physical environment and is, in turn, related to the degree of belonging that children experience in a playground. The line of argument synthesis reflects this complexity through the metaphor of a seesaw.

Next, an attempt is made to describe this complexity and the interrelationships between the physical and social environment, based on the identified characteristics of play value. One characteristic of play value is the children’s experiencing and mastering challenges. This can be described as a cycle of seeking challenges, mastering them, and seeking new challenges. Meeting these challenges is a meaningful experience that leads to positive feelings, such as excitement and self-esteem. On the one hand, these meaningful experiences are related to height, speed, and the unintended use of playground equipment or natural environments (e.g., trees and landscapes). On the other hand, the meaningful experiences arise from social interactions, such as playing together or collectively making fun of adults. Another perspective on the challenges in children’s outdoor play is Sandseter’s (Citation2007, Citation2009) conceptualisation of risky play, which is informed by children’s and preschool teachers’ perspectives. Some forms of risky play were also identified in our findings of children’s experiences of challenge. However, in our study, the children did not associate their experiences of challenge with risks, even though this is often referred to as risky play by adults.

‘Creating and shaping’ was identified as another characteristic of play value and also points to a difference in perceptions between adults and children. These findings correspond with those of other scholars who found that children’s use of places (Hart, Citation1979; Rasmussen, Citation2004) or performance of occupations (Graham et al., Citation2018) differ from adults’ perceptions or intentions. Our findings indicate that considering the differences in perceptions between adults and children is likely to be helpful in understanding children’s attachment to a place. From our study, it became evident that the occupation of ‘creating and shaping’ the physical environment of a playground is a way that children make places their own. In turn, from the meaningful experiences of ‘creating and shaping’, the feeling of attachment to the place (playground) arises, which contributes to a sense of belonging. This process of ‘making’ spaces into places and becoming attached to them, by engaging in meaningful occupations that result in a sense of belonging, has also been described in occupational science in relation to adult place-attachment (Rowles, Citation2008; Shaw, Citation2009; Zemke, Citation2004), but it is less researched in relation to childhood.

Other characteristics of play value were identified as playing together or alongside other children and experiencing a welcoming atmosphere on playgrounds, which contribute to children’s overall experience of belonging and sense of inclusion. From the findings, it became clear that the social experience of belonging is related to a physical environment characterised by variety and variability. Our results show that several dimensions are relevant in enabling a sense of belonging. These relate to basic needs, such as feeling safe and having access to the playground; the possibility to have an impact on the physical environment, to change it and leave one’s own mark; and social interactions with other children, either in direct contact with them or close by, which can all lead to a feeling of place-attachment and belonging. These results are confirmed by other studies (Chawla, Citation2020; Jansson et al., Citation2022; Rasmussen, Citation2004).

The results also indicate the importance of nature in play value and inclusion, as natural elements offer many opportunities for play, either in terms of challenge, creative use, social interaction, or variability. Chawla (Citation2020) identified the significance that engagement with natural environments has for children, for example in terms of agency when adventuring outside adults’ sight, evoking positive and calming emotions, and establishing attachment to a place and a feeling of belonging. Furthermore, the benefit of nature on children’s health and well-being is well documented (Adams & Savahl, Citation2017; Chawla, Citation2020; Gill, Citation2014; McCormick, Citation2017; Roberts et al., Citation2020), and it also shapes children’s awareness on environmental issues, such as biodiversity (Chawla, Citation2020). However, our findings showed that children with disabilities did not mention nature when they spoke about playgrounds. This raises a key issue concerning playground provision for children with disabilities: there is a need to not only consider accessibility and usability but also the provision of natural elements, as this is important for their health and well-being.

Studies investigating the experiences of children with disabilities also found that the influence of societal attitudes is crucial in terms of whether children feel welcome and included in playgrounds (Jeanes & Magee, Citation2012; Lynch et al., Citation2020; Sterman et al., Citation2019). While the focus of this study was not specifically on UD, indirectly the study was conducted to inform playground design for inclusion, through understanding children’s perspectives and their experiences of places for play as one user group. This meta-ethnography identified the need for variety and variability in the physical environment of a playground, which clearly addresses the principles of UD in the sense that even if not all elements are usable, there should be enough variety for every child to play, and variability of places and materials so that all children feel welcome. By analysing children’s play experiences in the context in which they take place, a better understanding of environmental design was achieved.

A literature review shows, however, that environments designed with UD in mind often do not focus on the occupations and associated meanings of the people that inhabit these environments (Watchorn et al., Citation2021). These findings may also be reflected in the results of a recent scoping review about guidelines for the design of inclusive playgrounds, which showed that even though some of the identified guidelines addressed UD principles and play value, it is unclear if universally designed playgrounds are effective in providing inclusion and play value (Moore et al., Citation2020). Perhaps this ambiguity can be traced back to a lack of focus on the occupations of children in playgrounds. Thus, to forward the understanding of how inclusion and play value can be supported through UD, it is hoped that the findings of this study will serve to inform the UD field. Focusing on children’s perspectives reflects a central element of UD, which is the inclusion of the user perspective (Iwarsson & Stahl, Citation2003; Lid, Citation2013). Furthermore, several authors have highlighted the importance of including the perspectives of children with diverse backgrounds when designing playgrounds (Jansson et al., Citation2022; Schoeppich et al., Citation2021).

Methodological considerations and future research

This study explored how environmental characteristics influence play value and inclusion in outdoor playgrounds from a child-centred perspective, and therefore the search strategy was designed to foreground children’s voices. Although we only included studies that reported children’s experiences of playing in outdoor playgrounds, it is possible that the results were influenced by adult views, due to the methodology of a meta-ethnography conducted by four adult researchers. Another limitation in relation to the search strategy is the restriction of the inclusion criteria to peer-reviewed studies published in English. This restriction may have led us to miss important research published in other languages or studies of children’s perception of play, which may differ across cultures. However, this does not explain the absence of studies from North America. Thus, in terms of the transferability of the review findings, this has to be taken into consideration. However, the search strategy was as open as possible to include the perspectives of children with diverse experiences. Furthermore, we acknowledge that the review authors are all based in European countries, which could have played a role in the interpretation of the studies. Additionally, the quality appraisal of the included studies showed that many studies had methodological limitations, which could point to the need for more methodologically robust qualitative research about children’s experiences of outdoor playgrounds. Future research should aim to expand the knowledge about the experiences of children with diverse backgrounds, experiences, and ages. Also, the understanding of play value from children’s perspectives should further be investigated, as this study is only a starting point in this area.

Conclusion

This study is, to our knowledge, one of the first studies investigating play value from children’s perspectives. Also, it is one of the first studies that discusses the connection of place-making, place-attachment, and belonging in relation to children within an occupational science perspective.

The results of the meta-ethnography contribute to the understanding of the interplay between the physical and social environment of playgrounds. The physical environment, characterised by a variety and variability of spaces and places, and designed and non-designed elements, is interrelated with children’s experiences of their play occupations in terms of play value and the social environment, including playing with or alongside other children and the feeling of belonging that contributes to inclusion. Furthermore, from an occupational science perspective, the present study adds knowledge that children, and especially children with disabilities, may experience play occupations and the use of play environments differently than adult interpretations. Thus, adopting such a perspective and including children’s perspectives in UD could be important in the design of inclusive playgrounds with high play value.

Acknowledgments

We thank the university librarian for the kind support during the search process.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, S., & Savahl, S. (2017). Nature as children’s space: A systematic review. The Journal of Environmental Education, 48(5), 291–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2017.1366160

- Agha, S. S., Thambiah, S., & Chakraborty, K. (2019). Children’s agency in accessing for spaces of play in an urban high-rise community in Malaysia. Children’s Geographies, 17(6), 691–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2019.1574335

- Akbar, P. N. G., & Edelenbos, J. (2021). Positioning place-making as a social process: A systematic literature review. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1), Article 1905920. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1905920

- Almers, E., Askerlund, P., Samuelsson, T., & Waite, S. (2020). Children’s preferences for schoolyard features and understanding of ecosystem service innovations—A study in five Swedish preschools. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 21(3), 230-246. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2020.1773879

- Altman, I., & Low, S. M. (1992). Place attachment. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-8753-4

- Aminpour, F., Bishop, K., & Corkery, L. (2020). The hidden value of in-between spaces for children’s self-directed play within outdoor school environments. Landscape and Urban Planning, 194, Article 103683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2019.103683

- Atkins, S., Lewin, S., Smith, H., Engel, M., Fretheim, A., & Volmink, J. (2008). Conducting a meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: Lessons learnt. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), Article 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-21

- Bartie, M., Dunnell, A., Kaplan, J., Oosthuizen, D., Smit, D., van Dyk, A., Cloete, L., & Duvenage, M. (2016). The play experiences of preschool children from a low-socio-economic rural community in Worcester, South Africa. Occupational Therapy International, 23(2), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.1404

- Booth, A. (2001, May 14-16). Cochrane or cock-eyed? How should we conduct systematic reviews of qualitative research? [Paper presentation]. Qualitative Evidence-based Practice Conference, Coventry, United Kingdom. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277255779_Cochrane_or_Cock-eyed_How_Should_We_Conduct_Systematic_Reviews_of_Qualitative_Research

- Booth, A. (2016). Searching for qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: A structured methodological review. Systematic Reviews, 5(74), Article 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0249-x

- Brussoni, M., Lin, Y., Han, C., Janssen, I., Schuurman, N., Boyes, R., Swanlund, D., & Mâsse, L. C. (2020). A qualitative investigation of unsupervised outdoor activities for 10- to 13-year-old children: “I like adventuring but I don’t like adventuring without being careful”. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 70, Article 101460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101460

- Burke, J. (2012). ‘Some kids climb up; some kids climb down’: Culturally constructed play-worlds of children with impairments. Disability & Society, 27(7), 965–981. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.692026

- Burke, J. (2013). Just for the fun of it: Making playgrounds accessible to all children. World Leisure Journal, 55(1), 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/04419057.2012.759144

- Cahill, M., Robinson, K., Pettigrew, J., Galvin, R., & Stanley, M. (2018). Qualitative synthesis: A guide to conducting a meta-ethnography. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 81(3), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022617745016

- Caro, H. E. E., Altenburg, T. M., Dedding, C., & Chinapaw, M. J. M. (2016). Dutch primary schoolchildren’s perspectives of activity-friendly school playgrounds: A participatory study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(6), Article 526. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13060526

- Casey, T., & Harbottle, H. (2018). Free to play: A guide to creating accessible and inclusive public play spaces. Inspiring Scotland, Play Scotland, & Nancy Ovens Trust. https://www.inspiringscotland.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Free-to-Play-Guide-to-Accessible-and-Inclusive-Play-Spaces-Casey-Harbottle-2018.pdf

- Chawla, L. (2020). Childhood nature connection and constructive hope: A review of research on connecting with nature and coping with environmental loss. People and Nature, 2(3), 619–642. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10128

- Children’s Play Policy Forum & UK Play Safety (2022). Including disabled children in play provision. https://childrensplaypolicyforum.files.wordpress.com/2022/03/including-disabled-children-in-play-provision.pdf

- Cooke, A., Smith, D., & Booth, A. (2012). Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1435–1443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452938

- Dalton, J., Booth, A., Noyes, J., & Sowden, A. J. (2017). Potential value of systematic reviews of qualitative evidence in informing user-centered health and social care: Findings from a descriptive overview. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 88, 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.04.020

- Delaisse, A.-C., Huot, S., & Veronis, L. (2020). Conceptualizing the role of occupation in the production of space. Journal of Occupational Science, 28(4), 550–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2020.1802326

- Edwards, B., Cameron, D., King, G., & McPherson, A. C. (2021). Exploring the shared meaning of social inclusion to children with and without disabilities. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 41(5), 467–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/01942638.2021.1881198

- European Standards. (2021). Accessibility and usability of the built environment. Functional requirements (Standard No. BS EN 17210:2021). https://www.en-standard.eu/bs-en-17210-2021-accessibility-and-usability-of-the-built-environment-functional-requirements/

- Fahy, S., Delicâte, N., & Lynch, H. (2021). Now, being, occupational: Outdoor play and children with autism. Journal of Occupational Science, 28(1), 114–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2020.1816207

- Fernelius, C. L., & Christensen, K. M. (2017). Systematic review of evidence-based practices for inclusive playground design. Children, Youth and Environments, 27(3), 78-102. https://doi.org/10.7721/chilyoutenvi.27.3.0078

- France, E. F., Cunningham, M., Ring, N., Uny, I., Duncan, E. A. S., Jepson, R. G., Maxwell, M., Roberts, R. J., Turley, R. L., Booth, A., Britten, N., Flemming, K., Gallagher, I., Garside, R., Hannes, K., Lewin, S., Noblit, G. W., Pope, C., Thomas, J., … Noyes, J. (2019). Improving reporting of meta-ethnography: The eMERGe reporting guidance. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), Article 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0600-0

- Garside, R. (2014). Should we appraise the quality of qualitative research reports for systematic reviews, and if so, how? Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 27(1), 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2013.777270

- Gerlach, A., Browne, A., & Suto, M. (2014). A critical reframing of play in relation to Indigenous children in Canada. Journal of Occupational Science, 21(3), 243–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2014.908818

- Gerlach, A. J., & Browne, A. J. (2021). Interrogating play as a strategy to foster child health equity and counteract racism and racialization. Journal of Occupational Science, 28(3), 414–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2020.1826642

- Gill, T. (2014). The benefits of children’s engagement with nature: A systematic literature review. Children, Youth and Environments, 24(2), 10–34. https://doi.org/10.7721/chilyoutenvi.24.2.0010

- Graham, N., Nye, C., Mandy, A., Clarke, C., & Morriss-Roberts, C. (2018). The meaning of play for children and young people with physical disabilities: A systematic thematic synthesis. Child: Care, Health and Development, 44(2), 173–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12509

- Hand, C., Prentice, K., McGrath, C., Laliberte Rudman, D., & Donnelly, C. (2023). Contested occupation in place: Experiences of inclusion and exclusion in seniors’ housing. Journal of Occupational Science, 30(1), 94–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2022.2125897

- Hart, R. (1979). Children’s experience of place. Irvington Publishers.

- Heatwole Shank, K., & Cutchin, M. P. (2010). Transactional occupations of older women aging-in-place: Negotiating change and meaning. Journal of Occupational Science, 17(1), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2010.9686666

- Hocking, C. (2009). The challenge of occupation: Describing the things people do. Journal of Occupational Science, 16(3), 140–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2009.9686655

- Huot, S., & Laliberte Rudman, D. (2010). The performances and places of identity: Conceptualizing intersections of occupation, identity and place in the process of migration. Journal of Occupational Science, 17(2), 68–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2010.9686677

- Iwarsson, S., & Stahl, A. (2003). Accessibility, usability and universal design—Positioning and definition of concepts describing person-environment relationships. Disability and Rehabilitation, 25(2), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/dre.25.2.57.66

- Jansson, M. (2015). Children’s perspectives on playground use as basis for children’s participation in local play space management. Local Environment, 20(2), 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2013.857646

- Jansson, M., Herbert, E., Zalar, A., & Johansson, M. (2022). Child-friendly environments—What, how and by whom? Sustainability, 14(8), Article 4852. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084852

- Jansson, M., Sundevall, E., & Wales, M. (2016). The role of green spaces and their management in a child-friendly urban village. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 18, 228–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2016.06.014

- Jeanes, R., & Magee, J. (2012). ‘Can we play on the swings and roundabouts?’: Creating inclusive play spaces for disabled young people and their families. Leisure Studies, 31(2), 193–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2011.589864

- Johansson, K., Laliberte Rudman, D., Mondaca, M, Park, M., Josephsson, S., & Asaba, E. (2013). Moving beyond ‘aging in place’ to understand migration and aging: Place making and the centrality of occupation. Journal of Occupational Science, 20(2), 108–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2012.735613

- Lee, E.-Y., de Lannoy, L., Li, L., de Barros, M. I. A., Bentsen, P., Brussoni, M., Fiskum, T. A., Guerrero, M., Hallås, B. O., Ho, S., Jordan, C., Leather, M., Mannion, G., Moore, S. A., Sandseter, E. B. H., Spencer, N. L. I., Waite, S., Wang, P.-Y., Tremblay, M. S., & participating PLaTO-Net members. (2022). Play, learn, and teach outdoors—Network (PLaTO-Net): Terminology, taxonomy, and ontology. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 19(1), Article 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-022-01294-0

- Lewin, S., Bohren, M., Rashidian, A., Munthe-Kaas, H., Glenton, C., Colvin, C. J., Garside, R., Noyes, J., Booth, A., Tunçalp, Ö., Wainwright, M., Flottorp, S., Tucker, J. D., & Carlsen, B. (2018). Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings—paper 2: How to make an overall CERQual assessment of confidence and create a Summary of Qualitative Findings table. Implementation Science, 13(1), 11–70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0689-2

- Lid, I. M. (2013). Developing the theoretical content in Universal Design. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 15(3), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/15017419.2012.724445

- Lynch, H., Hayes, N., & Ryan, S. (2016). Exploring socio-cultural influences on infant play occupations in Irish home environments. Journal of Occupational Science, 23(3), 352–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2015.1080181

- Lynch, H., & Moore, A. (2016). Play as an occupation in occupational therapy. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(9), 519–520. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022616664540

- Lynch, H., Moore, A., Edwards, C., & Horgan, L. (2018). Community parks and playgrounds: Intergenerational participation through universal design. University College Cork & Centre for Excellence in Universal Design. https://nda.ie/uploads/publications/Community-Parks-and-Playgrounds-Universal-Design-RPS2017.pdf

- Lynch, H., Moore, A., Edwards, C., & Horgan, L. (2020). Advancing play participation for all: The challenge of addressing play diversity and inclusion in community parks and playgrounds. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 83(2), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022619881936

- Mace, R. (1985). Universal design: Barrier free environments for everyone. Designers West, 33(1), 147–152.

- Manuel, P. M. (2003). Occupied with ponds: Exploring the meaning, bewaring the loss for kids and communities of nature’s small spaces. Journal of Occupational Science, 10(1), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2003.9686508

- Manzo, L. C., & Devine-Wright, P. (2020). Place attachment: Advances in theory, methods and applications (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- McCormick, R. (2017). Does access to green space impact the mental well-being of children: A systematic review. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 37, 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2017.08.027

- Miller, E., & Kuhaneck, H. (2008). Children’s perceptions of play experiences and play preferences: A qualitative study. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62(4), 407–415. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.62.4.407

- Moore, A., Boyle, B., & Lynch, H. (2022). Designing for inclusion in public playgrounds: A scoping review of definitions, and utilization of universal design. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2021.2022788

- Moore, A., & Lynch, H. (2018). Understanding a child’s conceptualisation of well-being through an exploration of happiness: The centrality of play, people and place. Journal of Occupational Science, 25(1), 124–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2017.1377105

- Moore, A., Lynch, H., & Boyle, B. (2020). Can universal design support outdoor play, social participation, and inclusion in public playgrounds? A scoping review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(13), 3304-3325. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1858353

- Moore, D., Morrissey, A.-M., & Robertson, N. (2021). ‘I feel like I’m getting sad there’: Early childhood outdoor playspaces as places for children’s wellbeing. Early Child Development and Care, 191(6), 933–951. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2019.1651306

- Morgenthaler, T., Schulze, C., Pentland, D., & Lynch, H. (2023). Environmental qualities that enhance outdoor play in community playgrounds from the perspective of children with and without disabilities: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), Article 1763. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031763

- Ndhlovu, S., & Varea, V. (2018). Primary school playgrounds as spaces of inclusion/exclusion in New South Wales, Australia. Education 3-13, 46(5), 494–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2016.1273251

- Noblit, G., & Hare, R. (1988). Meta-ethnography. Sage.

- Parham, D. L. (2008). Play and occupational therapy. In D. L. Parham & L. S. Fazio (Eds.), Play in occupational therapy for children (2nd ed., pp. 3-39). Elsevier.

- Parker, R., & Al-Maiyah, S. (2021). Developing an integrated approach to the evaluation of outdoor play settings: Rethinking the position of play value. Children’s Geographies, 20(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2021.1912294

- Pawlowski, C., Veitch, J., Andersen, H., & Ridgers, N. (2019). Designing activating schoolyards: Seen from the girls’ viewpoint. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(19), Article 3508. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193508

- Prellwitz, M., & Skär, L. (2007). Usability of playgrounds for children with different abilities. Occupational Therapy International, 14(3), 144–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.230

- Probyn, E. (1996). Outside belongings. Routledge.

- Prompona, S., Papoudi, D., & Papadopoulou, K. (2020). Play during recess: Primary school children’s perspectives and agency. Education 3-13, 48(7), 765–778. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2019.1648534

- Rasmussen, K. (2004). Places for children – Children’s places. Childhood, 11(2), 155–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568204043053

- Roberts, A., Hinds, J., & Camic, P. M. (2020). Nature activities and wellbeing in children and young people: A systematic literature review. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 20(4), 298–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2019.1660195

- Rowles, G. D. (2008). Place in occupational science: A life course perspective on the role of environmental context in the quest for meaning. Journal of Occupational Science, 15(3), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2008.9686622

- Sandseter, E. B. H. (2007). Categorising risky play—How can we identify risk-taking in children’s play? European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 15(2), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930701321733

- Sandseter, E. B. H. (2009). Characteristics of risky play. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 9(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729670802702762

- Saragih, J., & Tedja, M. (2017, November 14-15). How children create their space for play? [Paper presentation]. International conference on eco engineering development, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/109/1/012045

- Sattar, R., Lawton, R., Panagioti, M., & Johnson, J. (2021). Meta-ethnography in healthcare research: A guide to using a meta-ethnographic approach for literature synthesis. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), Article 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-06049-w

- Schoeppich, A., Koller, D., & McLaren, C. (2021). Children’s right to participate in playground development: A critical review. Children, Youth and Environments, 31(3), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.7721/chilyoutenvi.31.3.0001

- Shaw, L. (2009). Reflections on the importance of place to the participation of women in new occupations. Journal of Occupational Science, 16(1), 56–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2009.9686643

- Steinfeld, E., Maisel, J., & Levine, D. (2012). Universal design: Creating inclusive environments. John Wiley & Sons.

- Sterman, J. J., Naughton, G. A., Bundy, A. C., Froude, E., & Villeneuve, M. A. (2019). Planning for outdoor play: Government and family decision-making. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 26(7), 484–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2018.1447010

- Toye, F., Seers, K., Allcock, N., Briggs, M., Carr, E., Andrews, J., & Barker, K. (2013). ‘Trying to pin down jelly’—Exploring intuitive processes in quality assessment for meta-ethnography. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 2–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-46