Abstract expressionism is among the many Western art movements that Aboriginal art has been compared to. That is to say, Aboriginal art is understood through abstract expressionism. But what would happen if we reversed the poles and understood abstract expressionism through Aboriginal art? One of the things that Aboriginal art might bring to our understanding of abstract expressionism is a sense of meaningfulness, or even of meaningfulness without meaning. Indeed, it is by means of this category that we might distinguish abstract expressionism from abstract art in general.

In this paper, I will outline this distinction through the work of the American philosopher Stanley Cavell, and attempt to show how it plays out in the criticism of one of Cavell's great followers, the art historian Michael Fried. We will see how the search for the ‘intention’ behind abstract expressionism is replaced by the need to find the ‘motivation’ that drives abstraction. It is for this reason that something ended in art with the passing of abstract expressionism, at least until it returned with the arrival of contemporary Aboriginal art.

* * *

One day in 1990—over 20 years ago now—the art dealer Mary Macha decided to take her friend and client, Kimberley artist Rover Thomas, known for his strong lines and monochromatic surfaces, to the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) in Canberra. Thomas, along with Trevor Nickolls, had recently been selected to represent Australia at the Venice Biennale—the first Aboriginal artists to be included in the exhibition. Although Thomas had previously visited Perth and Darwin, he had never been outside of the country, and Macha thought it would be good for him to see, for the first time, a major museum full of artists from other cultures in order to prepare him for the experience. Thomas, who was originally born in the Great Sandy Desert, had moved with his family as a young boy to the Kimberley and the Gija-speaking community, where he worked as a stockman at various cattle stations. He took up painting at the age of 54 when he was entrusted with the designs for the Gija Krill Krill ceremony.

Thomas had had virtually no direct contact with European art. And, from a European perspective, the idea of comparing Aboriginal and European art, and particularly in terms of their shared abstraction, had not really taken off by 1990. If such a comparison had been possible earlier in the century for the likes of Margaret Preston, it later seemed like something that should no longer be pursued. In the wake of Imants Tillers’ appropriation of Michael Nelson Jagamara's Five Dreamings (1984), and the storm of protest it incited from both urban Aboriginal artists and politically sensitive white critics, there was more emphasis on the incommensurability between the two cultures, with the idea that any European engagement with Aboriginal art could result only in exploitation and misunderstanding.Footnote

Nevertheless, it was from across this gulf—and against all of the prevailing cultural and political considerations—that Thomas reached out. In the NGA, in front of American painter Mark Rothko's 1957 #20 (1957), Thomas famously remarked in laconic fashion: ‘Who's that bugger who paints like me?’ To take up the NGA's Curator of Aboriginal Art, Wally Caruana:

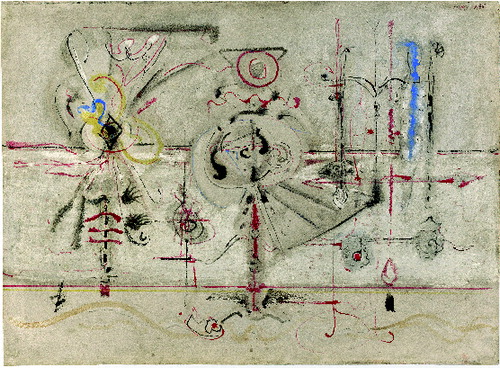

One of Thomas's most enduring images is Roads Meeting (1987). An image of reconciliation, the image of the black line, symbolising a bitumen road, crossing the red line of an ancestral path, suggests an inescapable reality: the mixture of peoples sharing the same lands in the contemporary world. [And in the same way] The need for artists to express the human condition may have moved Thomas to comment on ‘that bugger’ Rothko's painting.Footnote

Figure 1. Mark Rothko, Archaic Idol 1945, ink and gouache on paper, 55.6 × 76.2 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York, The Joan and Lester Avnet Collection, 157.1978.a-b. Digital image: © The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence. © Mark Rothko/ARS. Licensed by Viscopy.

This episode has been retold many times in Australian art history; mostly, as in the passage above, as an allegory of cross-cultural exchange. Here we have an Aboriginal artist—acting against the prevailing mood of distrust and scepticism—licensing the kinds of comparison then largely off limits to white art critics. And after Thomas's response there was, we might say—rather appropriately, given that his principal Dreaming later became a cyclone—the deluge. Aboriginal art was compared almost indiscriminately to French impressionism, Chinese and Japanese calligraphy and minimal art. Artists like Emily Kngwarreye were variously compared to Claude Monet, Paul Klee, A.R. Penck and Ralph Balson.Footnote But at the risk of repeating the same mistake, I would like to stick with Thomas's initial insight and consider why it is that the comparison with abstract expressionism is the right one for Aboriginal art. However, I would like to invert the usual—absolutely Eurocentric—order in which this comparison tends to take place: that it is abstract expressionism that helps us understand Aboriginal art. Instead, I want to insist—against all chronology, all conventional conceptions of cultural influence and dissemination—that it is Aboriginal art that helps us understand abstract expressionism, that it is time to ask what Aboriginal art has to teach us about abstract expressionism.

Of course, Thomas's remarks are generally understood, in a patronising way, to commit that classic art-historical mistake of isomorphism. This is the belief that because two works of art look the same, they must mean the same thing. Thomas seems—and this is undoubtedly the source of the slightly superior humour it is possible to feel at his remarks—to be mistaking Rothko's work as being like his own, despite all of the obvious cultural differences, ceremonial purposes and artistic intentions separating the two. But what if Thomas sees a deeper connection between them, or even pre-emptively understands the dangers of isomorphism, of thinking that one can simply cross cultures on the basis of visual resemblance? What if what he was commenting on when he looked at Rothko's work was its mystery, and perhaps even incomprehensibility, to him, just as he was aware that his own work was mysterious and incomprehensible to its predominantly white audience? What if he recognised Rothko as an artist whose secret was unknown to him, just as Aboriginal art—even in such modern forms as Thomas's—is about a secret caught up in enormously complicated and often strictly regulated protocols regarding the sharing and withholding of culturally sensitive information?

To begin to explain this, let us take two absolutely typical pieces of Aboriginal art criticism that appeared recently in Australian art magazines. The first is by Australian art curator John McPhee in Art Monthly Australia, and is a review of a show by Mornington Island artist Sally Gabori. After admitting that he cannot read the specific iconography of Gabori's work, and that he knows nothing of the country she paints, he asks what it is that moves him so intensely about the work. To which he answers: ‘most significantly these are paintings of extraordinary commitment’.Footnote Alternatively, take the response of American English Professor Timothy Morton in the journal Discipline to the abstract weaves of Pintupi artist Yukultji Napangati, which he describes as existing in a ‘tug between what has been done and what cannot be known’, placing a responsibility upon their viewer ‘not to intone ritualistically about their hopeless entrapment in their cultural matrix’.Footnote

Perhaps the truly interesting thing about both of these pieces of contemporary art criticism is that they play out a precedent set by one of the great early commentators of Aboriginal art, the anthropologist Eric Michaels. Some 25 years ago, Michaels wrote a ground-breaking essay on the Yuendumu Doors, painted on a secondary school in Yuendumu in the Central Desert, and one of the foundational objects of the modern Aboriginal art movement. In his essay, Michaels speaks of the fact that, ‘in a way reminiscent of abstract expressionism, the viewer is encouraged to perceive meaningfulness but not meaning itself’.Footnote

These three pieces of writing are different—one by a curator, one by a professor of English and one by an anthropologist; one a review of an exhibition, one on a single work of art and one on a complex post-colonial object. But all conclude in a similar way: not with a specific reading or interpretation of the meaning of the work of art, but with a general invocation of its meaningfulness. It is, of course, easy to see this particular form of spectatorship as though it were a symptom of something other than a reaction to the work itself. What we have here is an ‘attunement’ towards the other as a ‘political’ expression of sympathy. In their engagement with Aboriginal art, the viewer enacts a certain kind of gestural politics that in all likelihood is ‘inauthentic’, and that, perhaps more than anything else, is the deferral or displacement of any ‘real’ political action. Put simply, Aboriginal art constructs a particular white subjectivity. And I would even suggest that the art is about this: even in its original context, the work does not entirely reveal its meaning to everybody. Rather, in the ‘tribal’ setting—hence the analogy with the circumstances in which a white viewer encounters it in a museum or art gallery—a procedure of ceremony is enacted around an occult or esoteric meaning. And, crucially, this ceremony is not the experience of the work's meaning, but the enactment of a meaningfulness. There is an emphasis by the artist, which is understood by their audience, not on the actual content of the Dreaming stories themselves, but on the fact that they are done the ‘right way’, that they are performed appropriately.Footnote

What, in the end, is the true shock of Aboriginal art? In a way—and this undoubtedly accounts for its double effect of anachronism as something that comes both out of a distant past and from a future that is yet to come—it is its hand-made quality in a time of post-modern reproduction. That is, Tillers could not have been more wrong when he spoke of the dots in Aboriginal painting as those of mechanical reproduction.Footnote They are, in fact, the very opposite: a sign of the presence of the artist during a period in which they are supposed to be ‘dead’. Indeed, we read Aboriginal art through the artist's subjectivity, or even intentionality, as indicated by their painterly ‘touch’, in something of a reference to the founding assumptions of the discipline of art history itself. The hand of the artist returns precisely at a time when it was thought to have disappeared, bringing with it all of those classic problems of forgery, authenticity and artistic quality. It is really only in Aboriginal art today that we have raised the issue of attribution in Australian art, and—as auction houses will confirm—really only with regard to Aboriginal art that we can meaningfully raise questions of good and bad work, both between artists and by the same artist.Footnote And, against the whole post-modern discourse of irony, we see in Aboriginal art an unquestioned sincerity: no one seriously doubts that Aboriginal artists mean what they paint; and even if this is understood as tradition, the basis of contemporary Aboriginal art is that this tradition is freely chosen or intended.Footnote In all of these ways, Aboriginal art constitutes that most impossible of returns, that—with both terms being given equal weight—of a certain abstract expressionism.

Of course, the obvious connection is that the original abstract expressionist artists were themselves interested in ‘primitive’ art and the idea of the ‘primitive’. Rothko gave his early works such titles as Archaic Idol (1945), Primal Landscape (1945), The Source (1945) and Ancestral Imprint (1946). Barnett Newman wrote his famous introduction to the show The Ideographic Picture (1947), in which he spoke in relation to the Indians of the Northwest Coast of shape as ‘a living thing, a vehicle for an abstract thought-complex, a carrier of awesome feelings [the artist] felt before the terror of the unknowable’.Footnote Adolph Gottlieb, too, spoke of ‘all primitive expression revealing the constant awareness of powerful forces, the immediate presence of terror and fear’.Footnote Needless to say, this reference to primitive art by the abstract expressionists has been variously interpreted, and alternately approved of and criticised. Irving Sandler, in his 1976 book The Triumph of American Painting, suggests that artists turned to American Indian art not so much because it embodied terror as because it evoked spirituality and community.Footnote Ann Gibson, in the chapter ‘Painting through Primitivism’ of her Abstract Expressionism: Other Politics, emphasises the incongruity of these white artists’ nostalgia for another culture while overlooking the actual Afro-American artists in their midst (and, perhaps even more pertinent for our argument here, there was also a largely unremarked-upon Native American artist amongst the abstract expressionists, the Chippewa-born George Morrison).Footnote But, in fact, we must grasp very carefully what the abstract expressionist artists were trying to do here. If we read their evocation of the ‘primitive’ attentively, we will see a very particular argument emerge. The ‘primitive’ is understood as innocent and child-like, surely, but more exactly as implying a kind of pre-linguistic or pre-semiotic state. It is almost as though it is a cry without words, an intention that cannot be conveyed, a meaningfulness that is unable to become a definitive meaning. De Kooning wrote that ‘The first man who began to paint, whoever he was, must have intended it’.Footnote And Newman similarly spoke of an ‘original man, shouting out his consonants, doing so in yells of awe and anger’.Footnote

It is just this kind of effect that the artists wanted in their own work. Again, of course, there is a whole diversity of statements made by the abstract expressionists and their critics as to how they wanted their work to signify, to mean, to function. But here I just want to draw out certain threads. First of all, they sought to do away with all ‘objective’—by which we might mean conventional, recognisable, socially shared and assumed—means of communication (which, for all of their sociability and recognisability, were considered not universal enough). This is the basis of the famous distinction between ‘object-matter’ and ‘subject-matter’ made by Meyer Schapiro in his essay ‘The Liberating Quality of the Avant-Garde’, in which he states that what must be avoided is the turning of the artist's feelings into static and reproducible forms or symbols: object-matter as opposed to subject-matter.Footnote But the abstract expressionists also rejected unconscious symbols or symbols of the unconscious. This was the basis for their eventual dismissal of surrealism, which must be explained not only as a chauvinistic assertion of the American, as opposed to the French, but also as a result of the realisation that the surrealist dream-image had become a technical and easily imitated vocabulary. Newman spoke of surrealism in his essay ‘The Plasmic Image’ as a ‘mundane expression’,Footnote while Gottlieb insisted that ‘for us it is not enough to illustrate dreams’.Footnote And finally, and perhaps most complexly, the abstract expressionists also rejected transcendent symbols or symbols of the transcendent; that is, symbols that indicated simply the inability to signify. This seems to be the meaning of Newman's subtle and intellectually brilliant refusal of any reading of the work in terms of beauty in his essay ‘The Sublime is Now’, in which he also criticises Immanuel Kant's version of the sublime, which for him is too ‘formal’, too ‘hierarchical’, too much like beauty, in terms of its objective signification:

The failure of European art to achieve the sublime is due to its blind desire to exist inside the reality of sensation (the objective world, whether distorted or pure) and to build an art within a framework of pure plasticity (the Greek ideal of beauty, whether that plasticity be a romantic active surface or a classic stable one).Footnote

However, while the abstract expressionists reject any recognisable—objective, symbolic, transcendent—language, they also reject any simple refusal to signify, or the opening up of their work to chance and contingency. This means that they distance themselves from that aspect of surrealism it shares with Dadaism: its automatism. As Robert Motherwell writes in the introduction to his book The Dada Painters and Poets: ‘[The abstract expressionists] are at the antipodes of automatism and mechanism, and no less from the cunning ways of reason’.Footnote And this, again, is why we might make a distinction—and not just for chauvinistic reasons—between the abstract expressionists and those French or French-inspired tachist or informel artists like Jean-Paul Riopelle (and the Canadian group Les Automatistes associated with him), whose Knight Watch (1953) is meant to have come about outside of the artist's control. By contrast, Pollock and all those later abstract expressionists who spoke for him would always strenuously deny the element of chance in his work, asserting such things as ‘I control the flow of paint. There is no accident’ or ‘I am literally inside my paintings’.Footnote Indeed, strictly speaking, we would not even describe abstract expressionism as gestural, if by gesture we mean something autonomous, a loss of control, the hand of the artist carrying out an action beyond the artist's intentions.

The effect for the abstract expressionists is a particular kind of image that is not exactly symbolic, nor that other favourite word hieratic, insofar as these imply a certain objectivity, recognisability or translatability. Rather, what we have is a series of idiosyncratic marks that, although loosely repeated and in some ways identified with particular artists, are never exactly repeated, and whose meaning never entirely becomes clear. They would constitute a vocabulary but not quite a language; or, better, a cry or even words but not exactly a speech. The abstract expressionists, of course, had several names for the particular kind of image they were trying to create: the plasmic (Newman), the ideographic (Newman again), the glyph (David Smith) and the pictographic (Gottlieb and Arshile Gorky). And there were several ambitious attempts by the artists to explain what they were doing and the particular kind of art they were creating. Newman in ‘The Sublime is Now’ writes: ‘The artist must seek to throw off the impediments of memory, association, nostalgia, legend, myth, or what have you, that have been the devices of European painting’ and to make paintings ‘out of ourselves, out of our own feelings’.Footnote And Motherwell, in a 1959 School of New York exhibition catalogue (citing Odilon Redon), writes: ‘[My works] inspire and are not meant to be defined. They determine nothing. They place us, as does music, in the ambiguous realm of the undetermined. They are a kind of metaphor’.Footnote

This rejection of symbols did not prevent abstract expressionist works from having meaning (or, more precisely, meaningfulness). Indeed, their entire reception depended on the claim that they somehow communicated the greatest and most exalted of themes. We might begin with the statements of the artists themselves: Clyfford Still once wrote a letter to museum director Gordon Smith, claiming that his work stood against the whole ‘collectivist rationale of our society’, which he equated with a form of ‘intellectual suicide’.Footnote There is, of course, Newman's notorious claim, repeated in an interview with Dorothy Seckler, that if only people could read his work properly ‘it would mean the end of state capitalism and totalitarianism’.Footnote And this proud tradition has been continued in the subsequent reception of abstract expressionism, from critics writing immediately after the movement up to the present. For example, in 1950 the Director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), René d’Harnoncourt, issued a statement with two other gallery directors to the effect that they recognised ‘the humanistic value of abstract art as an expression of thought and emotion and the basic aspirations towards freedom and order’.Footnote This is extended and politicised in critic Max Kozloff's 1973 ‘American Painting During the Cold War’, in which he links abstract expressionism with French existentialism and, more generally, with an ‘equivocal yet profound glorifying of [the freedom of] American civilization’.Footnote And this, needless to say, has led to ongoing disputes as to whether the artists were for or against their society, whether abstract expressionism was radical or conservative, all the way up to charges that abstract expressionism—not only in its exhibition but also in its form—was a tool of American imperialism and CIA plans to defeat communism during the Cold War.Footnote

It is this generalised sense of meaningfulness that is the authentic experience of abstract expressionism, both its true ‘subject’ and the means by which it is to be distinguished from those other art movements for which it is often mistaken (tachism, art informel, colour field). We get the sense of a kind of semiotic pressure, a compelling need to impart something to us. A feeling that the artist is seeking to communicate something to us, but is unable to say exactly what it is. If the work can be said to be sublime—a word applied to it not just by Newman—it lies in the radical disjunction between the work and what it is understood to speak of. (This is how Newman uses the word and how, as we shall see in a moment, Harold Rosenberg uses it as the ‘cosmic’, despite most readings of his work.) Its message is not transcendent—Newman is right there—which would imply some universal and unchanging content that could finally be intuited some other way, but is to be understood only through its symbols, even though they are inadequate. (But there is no undeclared or declarable mismatch between them.) That is to say, to push the paradox to the limit, what we experience in abstract expressionism—what we are intended to experience—is an equivalence between the artist or the work of art and the spectator, a total coming-together without excess or remainder, but without it ever becoming clear what it is that passes between them. Sculptor David Smith wrote in 1953: ‘A work of art or an object of interest is always completed by the viewer’.Footnote Hans Hoffman, in reply to a question, once asked rhetorically: ‘If you do not understand a man who speaks a language you do not speak, is this therefore proof that the man babbles only nonsense?’Footnote There is, henceforth, no limit as to what signifies in abstract expressionist work: everything is absolutely charged with meaning, although there is no sense of what, exactly, is being communicated. It is perhaps not by coincidence that David Anfam, in his Abstract Expressionism, cites a passage from Henry James, which sounds like a description not just of one of Pollock's drip paintings, but of the—I would say absolutely commensurate—process by which the consciousness of the spectator, underwritten by what they take to be the intention of the artist, extends to the furthest reaches of his canvases, down to the smallest particles of painterly presence. Indeed, we see something of this attitude in the writings of Michael Fried on Pollock, all the way from his early description of the spectator's eyesight ‘moving without resistance’Footnote through the work in ‘Three American Painters’ to his assertion that every part of Pollock's all-overs is charged with ‘pictorial intensity’Footnote in his review of Pollock's 1998 retrospective at MoMA. Here is the Henry James passage relevant to Pollock, according to Anfam: ‘Experience is never limited, and it is never completed; it is an immense sensibility, a kind of huge spider web of the finest silken threads suspended in the chamber of consciousness, and catching every airborne particle in its tissue’.Footnote

All of this aspiration towards meaning requires a certain attitude by the maker, and accounts from the period are full of descriptions of the artist as ‘sincere’, ‘committed’, ‘authentic’ and ‘responsible’. Equally, it requires from the spectator a kind of openness and willingness to engage with the unknown, which can also be interpreted in a number of ways. Stepping back a little, the entire interaction between work and spectator can be diagnosed as belonging to a period of consumerist-inspired individualism, existentialism and the ethics of personal responsibility in an emerging post-liberal society. It is a phenomenon quite rightly subject to the broadest sociological analyses, under such headings as ‘Individualism, Universalism and the Cold War’, ‘The Discrediting of Collectivist Ideology’ and ‘Narcissism in Chaos: Subjectivity, Ideology, Modern Man and Women’.Footnote The engagement with the work of art would require a certain subjective disposition or comportment, a kind of spiritual exercise in self-formation of the sort described by Michel Foucault or Pierre Hadot. We might recall here Schapiro's description of the effects of the work in ‘The Liberating Quality of Avant-Garde Art’: ‘If painting and sculpture do not communicate, they induce an attitude of communion and contemplation. They offer to many an explanation of what is regarded as part of religious life: a sincere and humble submission to a spiritual object’.Footnote And no doubt all of this can be analysed in terms of ‘bad faith’—or, to use T.J. Clark's term, ‘vulgarity’—just as we would say the same thing of contemporary white Australians who bow down before works of Aboriginal art as though that in itself could somehow overcome or ameliorate social injustices.

To extend this ‘contextualisation’ of abstract expressionism, I would suggest that the whole enterprise of art history is part of this critical, desublimatory project, whether it realises it or not. Infamously, we might think of that arch-populist Robert Hughes, who in his American Visions television series stood in front of Newman's Stations of the Cross series (1958–66) and repeated the artist's stated ambition—already in a way the work's desublimation—that he wanted to match the achievement of Michelangelo. ‘Sorry, Barney’, Hughes contemptuously riposted, ‘you lost’.Footnote

But perhaps even the great Clement Greenberg carried something of this impulse to tear down abstract expressionism (we might, indeed, diagnose in him a form of art-historical terror before the sublimity of the work). His crucial retrospective essay ‘After Abstract Expressionism’ is not merely the tracing of the fate or aftermath of the so-called New York School, but in its very historicisation—and positing of an always comparativist aesthetic ‘quality’—is itself this aftermath. Put simply, the aestheticisation of abstract expressionism that Greenberg inaugurates, the seeing of it as troping its own medium, is a way—admittedly, against Greenberg's own conception of what he was doing—of giving the work meaning (and in this regard there is a strong continuity between Greenberg's modernist self-reflexivity and the post-modern ‘criticality’ that follows him). Asserting this meaning brings on precisely a loss of, or falling away from, that meaningfulness that abstract expressionism is authentically about. And at moments Greenberg even admits this. After speaking of a ‘self-critical’ process that would get us to what he calls the ‘irreducible essence of art’, he then goes on to qualify this by asking: ‘What is the ultimate source of value or quality in art?’ And immediately answers: ‘conception’ or ‘inspiration’, of which, he says, exactly with reference to that all-signifying quality of abstract expressionism we have been trying to put our finger on: ‘The exact choices in colour, medium, size, shape, proportion are what determine the quality of the result, and these choices depend solely on inspiration or conception’.Footnote

Something of this might be seen also with that other major theorist of abstract expressionism, Harold Rosenberg. Rosenberg's ‘The American Action Painters’ was mostly read at the time, for example by Greenberg, as a mere vulgar reduction of the work of art to action, gesture and the time of its making—and this, of course, is largely the way it is received today. But—in, admittedly, a very fine distinction—Rosenberg does in fact open up a certain distance between the work and its physicality, attributing to it a kind of meaningfulness. He speaks not so much of an ‘is’ with regard to the work as of a ‘seems’, which is the essential attribute for the search for meaning, for something behind what is. He characterises the work in terms of ‘a drama of as if’, and of the artist playing a certain ‘role’, with which they are nevertheless to be identified.Footnote

If we were to look for a philosopher of abstract expressionism, or a philosopher whose work most closely aligns with abstract expressionism—and this would be ironic, in the same way that Henri Bergson is often thought of as the great philosopher of cinema, despite his disapproval of actual films—it would be the American ‘ordinary language’ philosopher Stanley Cavell. In a series of important essays from the mid-1960s such as ‘A Matter of Meaning It’ and ‘Knowing and Acknowledging’, Cavell sets out the essential conditions for abstract expressionism (even though, like Bergson, he was not sure that abstract expressionism would pass the test).Footnote In ‘A Matter of Meaning It’, Cavell speaks of the way that modernism is characterised by a kind of scepticism, insofar as it always depends on new or untried conventions. Indeed, if modernism is anything, it is the sense that the existing conventions of a particular art form no longer apply and new ones must be found. (This is, needless to say, what we have been suggesting is at stake in abstract expressionism.) But this, as Cavell admits, opens modernism up to the possibility of fraudulence, inadvertence and incomprehensibility. How, then, are we to know if what is said in a modernist work of art is meant? Cavell cites the necessity for a certain conviction in the work that allows us to consider what it means in the absence—insofar as it does not yet exist—of any objective evidence for that meaning. It is a conviction, that is, that comes before any evidence for it (just as Greenberg speaks of an ‘inspiration’ or ‘conception’ that comes before ‘skill, training or anything else having to do with execution or performance’).Footnote As Cavell writes, making the point not that the artist actually intends what we see in the work of art, but rather that we must see such work as intended; that we must attempt to find or locate the intention of the work of art, with which the artist is then (or can be, if it is to be what Cavell calls a ‘serious’ work of art) identified: ‘The artist is responsible for everything that appears in his work—not just in the sense that it is done [by them], but in the sense that it is meant’.Footnote

Thus, this idea of conviction is not only found in abstract expressionism, but is the very subject of abstract expressionism. We have the sense that in these works everything is meaningful, everything is intended; that there is always more to be understood about them. However, there is no giving up on the work of art because we feel that the artist stands somewhere outside of it, or is only pretending to say what he does. On the contrary, the artist is absolutely present and part of the work. And to show how these issues play out I would like briefly to conclude with an artistic example discussed by Cavell's great disciple, Michael Fried. It is the work of an artist usually considered a colour field or even a ‘concrete’ or monochrome painter, but whom we might call here an abstract expressionist: the American Joseph Marioni, who makes his work by running a series of subtly different-coloured layers of paint down the canvas, almost like glazes, at certain points momentarily diverting the flow of paint by using the end of his paintbrush, his hands or a lamb's wool roller. There is a review by Fried of a small Marioni retrospective in the September 1998 issue of Artforum, which forms the basis of the chapter on him in Fried's recent book Four Honest Outlaws: Sala, Ray, Marioni, Gordon, in which he speaks of Marioni as making paintings in the ‘fullest and most exalted sense of the word’, after what he calls, somewhat slightingly, the ‘Minimalist intervention’.Footnote In other words, Fried thinks that Marioni does not merely make paintings after minimalism, but somehow catches minimalism up in a wider project (that is, modernist painting), thereby overcoming its scepticism and disbelief and replacing these with conviction and belief. And it is this, amongst other similar developments, that allowed Fried to return to criticism after a 20-year absence with his review of Marioni, insofar as he believed that his requirement of artistic conviction, which he takes from Cavell, could still be found in the art of today after the irony of post-modernism.

But what exactly does Fried mean by speaking of Marioni coming after minimalism? In what sense is Marioni able to defeat the scepticism that Fried originally diagnosed in his seminal 1967 essay ‘Art and Objecthood’?Footnote To answer these questions, we might briefly compare Marioni with a painter to whom he is often related—and, indeed, the two are friends and colleagues—the minimal, not post-minimal, painter Robert Ryman. Ryman, as is well known, makes works using and about various painterly materials and techniques—frames, canvases, brushes, brush marks, the mounting of the canvas on the wall and so on—in what can be seen as an intense meditation on the various properties and procedures of painting. Perhaps the best-known text on Ryman is Yve-Alain Bois's ‘Ryman's Tact’, in which Bois at once repeats and distances himself from this usual, self-reflexive, pseudo-Greenbergian conception of Ryman. He writes: ‘An aesthetic of causality is reintroduced [in Ryman's work], a positivist monologue that we thought modern art was supposed to have gotten rid of: A (paintbrush) + B (paint) + C (support) + D (the manner in which these are combined) give E (painting). There would be nothing left over in the equation. Given E, ABCD could be deciphered, absolutely.’Footnote

But, in fact, Bois refuses to go along with this reading of Ryman, arguing that in the end there is always something that goes beyond this equation. The E in Ryman's work is always in excess of, and cannot simply be explained by, A, B, C and D. And in a paradoxical and perhaps deliberately self-contradictory way, we might even say that it is this excess or unknown that Ryman can be seen to be aiming at. That is, at a certain point Ryman knows that his method or procedure—and, of course, Ryman's work can be seen as a form of process art—breaks down; but it is just this failure that he desires. He is not, however, able to get to this point directly; it cannot happen consciously or be plotted in advance. It is only through Ryman's efforts at control that he can reveal what cannot be controlled. It is only at the end of his painterly procedure that he can expose its limits. It is undoubtedly for this reason that one of the privileged objects of Ryman's artistic engagement is the artist's signature, as in Untitled or For Gertrude Mellon (both 1958). The truth or authenticity of a signature lies in the fact that each is slightly different from the others, that there can be no direct copying of an original (a direct copying of another signature would, of course, be a forgery). However, the signatory cannot deliberately set out to achieve this difference, but can do so only through the attempt to actually produce another identical signature. Again, it is for this reason that critics speak of Ryman's work in terms of the philosophical doctrine of pragmatism, for his is an incessant attempt to take into account the limits of knowledge, the inability of rules to be definitive.Footnote He knows in advance that he can never get things entirely right, and he remains content to operate within these limits.

How different all of this is from the work of Marioni. At a certain point in Ryman's process, there is a giving up (not a giving up from the beginning, as in minimalism, but a giving up at the end). Although he makes work that appears self-referential and without remainder, he nevertheless knows in advance that this is impossible, and so his commitment to the project must always be divided. There is none of this in Marioni. It might appear that the final result of his work is beyond him. There are physical limits to the medium in which he works (depending on the viscosity of the paint, there are limits as to how much he can alter its course as it runs down the canvas, or to what extent his interventions can remain visible; there is a certain physical limit as to how large he can make his canvases and still have the individual droplets hold the surface or remain compositionally pertinent). And yet at no point does Marioni simply give up on, or disclaim, his work. Like Pollock, who asserted that there were no accidents when he was painting, Marioni is entirely confident that he remains in control of his process. He says, almost wittily, in an interview that he ‘controls the painting in his mind’ and that his favourite part of the process is ‘watching the paint dry in the end’, as though in simple confirmation of a prior cerebral process.Footnote In other words, Marioni fully intends—and seeks to make us feel as fully intended—every aspect of his work. Of course, we do not know exactly what is intended, only that it is intended. Henry Staten, one of Marioni's best critics, puts this in a superb aphorism. Paraphrasing the well-known argument about Shakespeare, he writes that Marioni is ‘everywhere present, but nowhere visible’ in his work.Footnote And we might express this as the inseparability of the depicted and the literal, and the optical and the material, in Marioni's oeuvre. Each absolutely is the other. Marioni, we might say, does not so much make monochromes as remake them. The work is perhaps nothing else but minimalism, but he intends this minimalism. It is exactly in this sense that he can be seen, as Fried asserts, as coming after the ‘Minimalist intervention’. He shows that minimalism means nothing unless it is meant, and that this meaning it— here he even goes beyond abstract expressionism—is the very subject of the work.Footnote

To conclude here, do we not see all of the above in T.J. Clark's extraordinary ‘In Defence of Abstract Expressionism’, the final chapter of his Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism? Clark begins, in 2001, by admitting that abstract expressionism is not yet distant enough for him properly to speak of it. It is as an attempt to distance it—to make it useful for art history—that he describes it (unexpectedly and unconventionally) as ‘vulgar’, by which he means ‘belonging to the pathos of bourgeois taste’ or expressing a ‘petty bourgeois attitude’.Footnote But this ‘vulgarity’, beyond the work's content or what it represents, is also a certain form or mode of address. It is vulgar exactly in its lack of irony, its absence of self-distancing (or at least its distancing from the spectator). This is the distinction Clark makes between the work, say, of Gottlieb or De Kooning and that of someone like Asger Jorn, of which Clark wonders whether it is ironising its vulgarity or somehow about its vulgarity. The same question might also be put to George Brecht and his ‘fake’ Pollocks, or to Robert Rauschenberg's Factum I and II (1957), or even to Gerhard Richter's late abstracts. In a way, all of this work would no longer be vulgar—and, therefore, no longer useful for art history and having to be distanced from us—because it is already its own irony, its own distancing. As Clark puts it, there is always raised with this ‘second generation’ of abstract expressionists the question of whether the author means it or not. There is a kind of distance—that constituted by the presence of the artist themselves—between us and the work, rather than the artist being in the work, to go back to Rover Thomas and Mark Rothko. As Clark writes:

An Asger Jorn can be garish, florid, tasteless, forced, cute, flatulent, overemphatic; it can never be vulgar. It just cannot prevent itself from a tampering and framing of its desperate effects which pulls them back into the realm of painting, ironises them, declares them done in full knowledge of their emptiness.Footnote

Of course, the great strength of Clark's approach—in its immense candour, we might even say its vulgarity—is that he admits that the entire enterprise of art history—its decoding, its interpretation, its symptomatology, ultimately even his own beloved class analysis—is nothing more than an attempt to distance ourselves from the overwhelming presence of the work (such proximity or desire to touch would be the opposite of Ryman's ‘tact’). It is art history itself, the very book Clark writes, that is the true farewell to modernism. But, as Clark admits at the end of his book, it is not so easy to distance ourselves from art, to ignore its meaningfulness and the unappeasable demands it makes of us. (Again, this is despite all of the ways in which we—and Clark—are able to analyse, describe and diagnose not only this meaningfulness, but also the susceptibility of its audience to it: the fact that it is social, not primitive; class-based, not universal; a product of aesthetic training, not innate knowledge.) For Clark admits that there is one thing he is unable to distance himself from in the work of the abstract expressionists, which still remains despite all attempts to get rid of it: what he calls the ‘lyrical’, by which he means the ‘voice’ of the artists themselves. The cry, the primitive cry without words, almost like a song. As he writes: ‘I do not believe that modernism can ever quite escape [from the lyric]. By lyric, I mean the illusion in an art work of a singular voice or viewpoint, uninterrupted, absolute, laying claim to a world of its own.’Footnote And, of course, it is this ‘lyricism’ that I believe Rover Thomas recognised and responded to that day in the gallery—across cultures, across time, across forms. Almost like that other great doubting, but still believing, Thomas. He saw in Rothko another poor ‘bugger’ just like him. Art history starts with this recognition, and abstract expressionism—and in saying this we have already begun to lose it, it is already beginning to lose itself—reminds us of this fact.

* * *

How then does Aboriginal art allow us to think about abstract expressionism? In some ways, the question is rhetorical. I wished to speak of, Rover Thomas' remarks in front of the Rothko, of which I wanted to say that he acknowledged meaningfulness without knowing an actual meaning. And it is this, I suggest, that we see today in the best of white critics’ responses to Aboriginal art. It is an attitude that has increasingly been lost over the previous 60 years of art history, since the end of abstract expressionism, but that the encounter with Aboriginal art is bringing back to us. And, furthermore, I would argue that all of those questions of sincerity, intentionality, the desire to mean, apply also to Aboriginal art today, which we insist is no longer a matter of simply following a pre-existing tradition, but of having to work (at least in part) outside or in consciousness of a tradition, with all of those questions of fraudulence, inadvertence and misattribution that Cavell identifies. Aboriginal art is contemporary, as it always has been since whites first arrived here, or even, to use Clark's word, ‘vulgar’. And this is to say—and this is the salutary thing about studying the reception of Aboriginal art in Australia by white critics—it takes us back, as abstract expressionism intended to do, to the first ‘primitive’ engagement with the work of art: outside of categories, outside of histories, outside of protective or distancing ironies or sublimating aesthetic comparisons.

Sometimes this contemporary meaningfulness is recognised by the ‘other’ side, not just by critics but also by artists (and there could be no more pressing a task, which has only partially been attempted, than writing a history not of the art-historical but of the artistic responses to Aboriginal art in Australia). Indeed, soon after delivering an earlier version of this paper at the Action. Painting. Now symposium, I was reminded by Daniel Thomas of David Smith's extraordinary welded steel sculpture Australia (1951), now held at MoMA, in remarks he made to the visiting American art historians. Here precisely lies the matching and reciprocal case from Rover Thomas's: not an Aboriginal artist recognising something of themselves in abstract expressionism, but an abstract expressionist recognising something of themselves in Aboriginal art. As Daniel Thomas proposes in ‘Aboriginal Art: Who was Interested?’, it is likely that Smith first encountered actual Aboriginal art in a 1946 exhibition at MoMA entitled Arts of the South Seas, curated by Ralph Linton and Paul Wingert, which featured an x-ray painting of a kangaroo from Goulburn Island in the Northern Territory.Footnote It is this x-ray style that Smith sought to imitate in Australia, with its thin wavering strips of metal welded on either side of a central bow and a circle above crossed by striated lines. Of course, in one way, Smith was ready for Aboriginal art because of his interest, shared by most, if not all, of the artists in the New York School, in primitivism, surrealism and the unconscious. But I want to say more than this. I want to suggest that, like Thomas in front of Rothko, Smith in his work is asking ‘Who is that bugger who paints like I sculpt?’

Figure 2. Rover Thomas [Joolama], Kukatja/Wangkajunga peoples, Roads meeting, 1987, natural earth pigments on canvas, 90×180 cm, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. © the artist's estate courtesy Warmun Art Centre.

![Figure 2. Rover Thomas [Joolama], Kukatja/Wangkajunga peoples, Roads meeting, 1987, natural earth pigments on canvas, 90×180 cm, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. © the artist's estate courtesy Warmun Art Centre.](/cms/asset/c6fd3a40-964e-4d91-bea3-84e38e09bc3f/raja_a_936529_f0002_oc.jpg)

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was delivered at the symposium ‘Action. Painting. Now’, held at the NGA, 24–25 August 2012. I would like to thank Roger Benjamin for his generous invitation to speak at the symposium.

Notes

1. See, for example, Juan Davila, ‘Aboriginality: A Lugubrious Game?’, Art & Text 23 (March–May, 1987): 53–8; and Tony Fry and Anne-Marie Willis, ‘Aboriginal Art: Symptom or Success?’, Art in America 77 (July 1989): 109–17.

2. Wally Caruana, ‘World of Dreamings: Traditional and Modern Art of Australia’, catalogue essay for National Gallery of Australia exhibition at the Hermitage, St Petersburg, February 2000, http://nga.gov.au/Dreaming/Index.cfm?Refrnc=Ch5.

3. See, for example, Michael Boulter, The Art of Utopia: A New Direction in Contemporary Aboriginal Art (Roseville: Craftsman House, 1991), and the essays in Jennifer Isaacs et al., Emily Kngwarreye Paintings (Roseville: Craftsman House, 1998), and Margo Neale, ed., Emily Kame Kngwarreye: Alhalkere: Paintings from Utopia (Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery, 1998).

4. John McPhee, ‘Sally Gabori: Feeling the Landscape’, Art Monthly Australia 249 (May 2012): 9.

5. Timothy Morton, ‘Yukulltji Napangati: Occupying Dreaming’, Discipline 2 (Autumn 2012): 55.

6. Eric Michaels, ‘Western Desert Sandpainting and Postmodernism‘, in his Bad Aboriginal Art: Tradition, Media and Technological Horizons (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993, 1993): 57.

7. See Vivien Johnson, Michael Jagamara Nelson (Roseville: Craftsman House, 1997), 70–75.

8. See Imants Tillers, ‘Fear of Texture’, Art & Text 10 (1983): 8–18.

9. For a summary, see Elizabeth Burns Coleman, ‘Art Fraud and the Ontology of Painting’, in Aboriginal Art, Identity and Appropriation (Ashgate: Aldershot, 2005).

10. This is Ian McLean's point in putting together Aboriginal tradition and modernity in ‘Aboriginal Modernism?: Two Histories, One Painter’, in Margo Neale, ed., Utopia: The Genius of Emily Kame Kngwarreye (Canberra: National Museum of Australia Press, 2008), 24. Extremely interesting in this regard is the Papunya painter Michael Nelson Jagamara, who returned to ‘traditional’ Aboriginal art after a period of what might be called abstract expressionism. For a survey of his later career, see Michael Jagamara Nelson and Imants Tillers et al., The Loaded Ground (Canberra: ANU Drill Hall Gallery, 2012).

11. Barnett Newman, ‘The Ideographic Picture’, in Barnett Newman: Selected Writings and Interviews, ed. John P. O’Neill (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 108.

12. Cited in Michael Leja, Reframing Abstract Expressionism: Subjectivity and Painting in the 1940s (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 69.

13. Irving Sandler, ‘The Mythmakers’, in The Triumph of American Painting: A History of Abstract Expressionism (New York: Harper & Rowe, 1976).

14. Ann Gibson, ‘Painting through Primitivism’, in her Abstract Expressionism: Other Politics (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

15. Willem de Kooning, ‘What Abstract Art Means to Me’, in Abstract Expressionism: Creators and Critics, ed. Clifford Ross (New York: Abrams, 1990), 36.

16. Newman, ‘The First Man was an Artist’, in Barnett Newman, 158.

17. Meyer Schapiro, ‘The Liberating Quality of Avant-Garde Art’, ArtNews 56, no. 4 (1957); reprinted in Abstract Expressionism: Creators and Critics, 258–69.

18. Newman, ‘The Plasmic Image’, in Barnett Newman, 140.

19. Radio interview with Rothko and Gottlieb; cited in Serge Guilbaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985),112.

20. Newman, ‘The Sublime is Now’, in Barnett Newman, 173. Michael Leja repeats the argument from Derrida that at once ‘no meaning can be determined outside of context’ and ‘no context permits saturation’ (Reframing Abstract Expressionism, 12), and this neatly captures Newman's sense of the sublime. It is neither transcendent (as in Kant) nor simply objective (as with beauty). It is in many ways Burke's sublime or the very ‘struggle between beauty and the sublime’ (‘The Sublime is Now’, 172).

21. Robert Motherwell ed., The Dada Painters and Poets: An Anthology (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2nd edition, 1981), xliii.

22. See, for example, Pollock's ‘Statement’, Possibilities 1, no. 1 (Winter 1947–48):147; reprinted in Abstract Expressionism: Creators and Critics, 138–40.

23. ‘The Sublime is Now’, 173.

24. Robert Motherwell, ‘Preface: The School of New York’, in his The Writings of Robert Motherwell (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 154.

25. Clyfford Still, ‘Letter to Gordon Smith’, in Abstract Expressionism: Creators and Critics, 195.

26. Newman, ‘Frontiers of Space: Interview with Dorothy Gees Seckler’, in Barnett Newman, 251.

27. René d’Harnoncourt et al., ‘A Statement on Modern Art’, in Abstract Expressionism: Creators and Critics, 232.

28. Max Kozloff, ‘American Painting During the Cold War’, Artforum 11, no. 9 (May 1973): 42.

29. For a summary, see ‘Introduction’, 74–79, and David Craven, ‘Dissent during the McCarthy Period’, in Reading Abstract Expressionism, ed. Ellen G. Landau (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005).

30. David Smith, David Smith: Sculpture and Writings (New York: Thames & Hudson, 1968), 68.

31. Cited in Becky Hendrick, Getting It: A Guide to Understanding and Appreciating Art (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2000), 7.

32. Michael Fried, ‘Three American Painters: Noland, Olitski, Stella’, in his Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 224.

33. Michael Fried, ‘Optical Allusions’, Artforum 37, no. 8 (April 1999): 97.

34. Henry James, ‘The Art of Fiction’, cited in David Anfam, Abstract Expressionism (New York: Thames & Hudson, 1990), 13.

35. These are chapter titles in Ann Gibson, Abstract Expressionism: Other Politics, 43–57, Nancy Jachec, The Philosophy and Politics of Abstract Expressionism 1940–80 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), 17–61, and Michael Leja, Reframing Abstract Expressionism: Subject and Painting in the 1940s, 208–74 respectively.

36. Schapiro, ‘The Liberating Quality of Avant-Garde Art’, 266.

37. Robert Hughes, American Visions, BBC, 1997, Episode 7. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZI-BjmNoxdk).

38. Clement Greenberg, ‘After Abstract Expressionism’, in The Collected Essays and Criticism, Vol. 4: Modernism with a Vengeance, ed. John O’Brien (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 132.

39. Harold Rosenberg, ‘The American Action Painters’, ArtNews 51, no. 8 (December 1952): 22.

40. See, for example, Stanley Cavell, ‘Music Discomposed’ in his Must We Mean What We Say? (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976): 202–03, where Cavell refuses to decide on the validity—or lack thereof—of a Pollock drip painting or Louis stripe painting.

41. Greenberg, ‘After Abstract Expressionism’, 132.

42. ‘A Matter of Meaning It’, in Cavell, Must We Mean What We Say?, 236–7.

43. Michael Fried, ‘Joseph Marioni, Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University’, Artforum 37, no. 1 (September 1998): 149.

44. Michael Fried, ‘Art and Objecthood’, Artforum 5, n. 10, June 1967, 12–23.

45. Yve-Alain Bois, ‘Ryman's Tact’, in his Painting as Model (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990), 216.

46. On Ryman's link to pragmatism, see Suzanne Perling Hudson, Robert Ryman: Used Paint (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009).

47. Cited in Ingvild Goetz, ‘Written Interview with Joseph Marioni’, in Monochromie Geometrie (Munich: Sammlung Goetz, 1996), 66.

48. Henry Staten, ‘Painting Beyond Narrative’, Kunstforum International 84 (March/April, 1987): 84.

49. See also Fried’s essay ‘Thomas Demand’s Pacific Sun’, in Thomas Demand: Animations, ed. Carrie Schmitz (Des Moines: Des Moines Art Center, 2013), np; in many ways Pacific Sun is like a Pollock drip painting or a Carl Andre scatter piece, except that its individual elements are deliberately placed or intended,

50. T.J. Clark, ‘In Defence of Abstract Expressionism’, in his Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Taste (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), 388.

51. Clark, ‘In Defence of Abstract Expressionism’, 390.

52. Clark, ‘In Defence of Abstract Expressionism’, 401.

53. Daniel Thomas, ‘Aboriginal Art: Who Was Interested?’, Journal of Art Historiography 4 (June 2011), http://arthistoriography.files.wordpress.com/2011/05/daniel-thomas-document.pdf. Another theory has it that it was Clement Greenberg who sent Smith some reproductions of ‘Aboriginal cave paintings’; see http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/david-smith-sculptures/david-smith-sculptures-room-guide/david-smi-3.