With optimism, Miranda Goeltom, then chair of The Indonesian Arts Foundation, penned the foreword for Indonesia's first book on women artists, Indonesian Women Artists: The Curtain Opens. She described the book as an ‘historic step to record, recognise and present the works of our inspired and talented women artists and art writers to a wider audience both here and abroad’.Footnote Like other feminist-inspired texts, this first major survey on the lives and works of Indonesia's ‘most prominent women artists from the early twentieth century to the present’,Footnote aimed to show precisely that women artists were present and they were active within national circles.

For over four decades, feminist art historians and social historians across the world have conducted research and developed methodologies with the aim of rediscovering and re-evaluating women artists. Indonesian Women Artists (2007) was launched in conjunction with a ground-breaking exhibition, Intimate Distance: Exploring Traces of Feminism in Indonesian Contemporary Art, curated by the book's authors. It coincided with the exhibition Global Feminisms: New Directions in Contemporary Art (2007) at the Brooklyn Museum, the first large-scale American exhibition to consider the internationalisation of ‘feminism’ in art. The former was held at the National Gallery of Jakarta and aimed to examine traces of feminism in Indonesian women's art and the strategies employed by the artists. It also marked the first attempt to map the issues that are related to creative development and femininities in ‘Indonesia's patriarchal art world’, a subject that was later developed into a cogent doctoral study by one of the curators, Wulandani Dirgantoro.Footnote

In Dirgantoro's study, she argued that Kelompok Perek (Women's Experimental Group) was the first Indonesian art collective to express left-leaning, feminist intentions in their work. This was congruent with the common observation that the 1990s marked the moment when ‘Western/Post-structuralist feminism/s’ entered the Indonesian art discourse.Footnote In her study, Dirgantoro used psychoanalysis as a methodological tool to frame the analysis of selected works by Indonesian women artists. Her readings of the confronting works by the late Balinese painter, IGAK Murniasih employed a narrow application of Barbara Creed's notion of ‘active monsters’ and ‘the castrating female’ in order to understand how female agency can by asserted by ‘women in Indonesian visual arts’.Footnote

However effective her methodology, Dirgantoro's conclusions are likely limited to a very small subsection of artists in Indonesia who would produce such confronting works in the first place. Further, the irrelevance of the ‘feminist’ discourse Dirgantoro employed, viewed as being synonymous with Western ideology, has been strongly vocalised in Indonesia where many still question its applicability to local contexts.Footnote Dirgantoro took a precarious position when arguing for the relevance of the term ‘feminist’, and her difficulty in using the term was echoed by an Indonesian feminist scholar, Saparinah Sadli, who observed that even in the Department of Women's Studies, they were very careful not to use terms like ‘gender perspective’ or ‘feminist perspective’ at the official level, opting instead for the term ‘women's perspective’, even though they were ‘in fact discussing the methodologies usually known as feminist or gender perspectives’.Footnote

While there has been little consensus on the definition and relevance of the term ‘feminism’, scholars and members of the intellectual and cultural circuit were nonetheless convinced that the Indonesian art world was irrevocably male-dominated, and there existed a mainstream masculine language that excluded female subjectivity. Heidi Arbuckle highlighted this issue in her doctoral dissertation on Emiria Sunassa, in which she argued that the masculine language and structure of the Indonesian art-historical canon, which had adopted ‘elements of the western canon’ including its gender exclusions, had in fact reinforced the erasure of Emiria and also women's histories in Indonesia.Footnote Using S. Sudjojono's writings as the basis for her analysis, she demonstrated that gender bias was inherent in Indonesian discourse, arguing that Emiria's creative visual representations were potentially disruptive and subversive of nationalist and colonial ideologies, and therefore that, according to the canon, Emiria had to be ‘erased’.

However, for the vast majority of the women artists who were gradually gaining visibility in Indonesian institutions, it was not their ideologies but their creative ability that was being questioned. In 1997, one eminent Indonesian curator, Jim Supangkat, who bemoaned the lack of originality he observed in an all-women exhibition, went as far as to urge women artists to shed male ideological influence or risk becoming epigones.Footnote This very questioning of ‘women of genius’ or ‘worthies’ is often central to feminist discourse. Feminist historians have since demonstrated that such terms of analysis used in art history—determinants of ‘greatness’—were not gender-neutral. These socially constructed categories, as demonstrated by the discipline of art history, have maintained the canonical status of male practitioners and ensured the privileging of male taste.Footnote

In the following account, I will examine how women gained access to the requisite knowledge of art-making and exhibiting, asserting authority by paralleling the processes followed by men. In identifying such oft-overlooked historical perspectives, this paper aims to trace the historical development of feminist consciousness as demonstrated from the ways in which Indonesian women artists have made comparable attempts to men to stage professional exhibitions, and to create new public spheres for other women.

Feminist consciousness, as defined by Gerda Lerner, refers to a woman's awareness that she belongs to a subordinate group, and suffers wrongs as a group due to conditions that are societally determined.Footnote By joining with other women to remedy the ‘wrongs’, Lener observed, women who had developed feminist consciousness could then provide an ‘alternate vision of societal organization in which women as well as men will enjoy autonomy and self determination’.Footnote This paper thus explores the rise of feminist consciousness among Indonesian women artists who, as a collective, contested against the restrictive terms on which women were to operate in the public sphere as professional artists. I argue that the active collaboration of women artists who struggled against the condition of peran ganda (double role) in the formation of Nuansa Indonesian, a collective that sought to promote professionalism in the exhibitory world by women, was unquestionably conducted in the spirit of feminism. This series of women-centred exhibitions marked one of the first steps toward understanding their conditions, and toward re-modelling the male-dominated Indonesian art world.

Becoming Professional: Women Painters from Institut Teknologi Bandung and Surabaya Academy of Fine Arts

As Indonesia transitioned into a new era of authoritarian control that was abruptly brought about by the introduction of Suharto's New Order in 1966, Indonesia's nationalist project was invigorated with new ideologies and fresh symbols.Footnote A tacit shift was observed by a number of scholars in the taste and preference of the newly inaugurated government that acted to suppress communist ideological associations across all facets of Indonesian society.Footnote Socialist-realist paintings fell out of favour, and abstract art and aesthetics gained unprecedented attention.

The Seni Rupa Academy of the Institut Teknologi Bandung (ITB), with its strong foundation in a Western-influenced aesthetic, played a significant role in cultivating Indonesian abstract artists who later became leaders in the field. This was in part due to the city's colonial ties and the influential teachings of a number of early Dutch art masters at the school. Seen as savvy in international trends, the Bandung artists quickly gained recognition as the forerunners of Indonesia's modernism.Footnote Many trained graduates went on to influence the expanded art community in Jakarta, the country's capital city. Women were very much a part of this participation in rapidly expanding markets and the growth of cultural developments, and some were able to make use of the opportunities and the increase in social mobility to advance their position and assert creative authority.

Under the New Order, Suharto assumed his paternalist position when defining women's kodrat (nature) in modern Indonesian society. He described ‘ideal’ Indonesian women as being ‘aware of their function as women and as good citizens … They are free to enter careers but at the same time, should not sacrifice family responsibilities.’Footnote The political rhetoric insisted that women's emancipation in relation to the right to an education, or a career, was couched along nationalist lines. Women, like men, needed to play their part as ‘good citizens’ for Indonesia's future, which, according to such rhetoric, depended on how well women performed their predetermined roles as mother and wife.

Nira Yuval-Davis has observed that women's membership in their national and ethnic collectives is characteristically of a double nature: women, like men, are members of the collective, but yet, there are always ‘specific rules and regulations which relate to women as women’.Footnote It was precisely the political and ideological assertion of women's peran ganda (double role) that provided the grounds for women to justify the organisation of sex-segregated art networks. Although these developments have not been examined in the context of feminist art movements, early traces of feminist consciousness can already be found in female-only clusters. Such clusters often came about in spontaneous circumstances and were underscored by the common conditions of womanhood.

One such example was the coming together of five Bandung-based women artists, Ardha, Erna Pirous, Chairin Hayati, Farida Srihadi and Heyi Ma'mun, in an exhibition entitled simply Pameran 5 Pelukis Wanita (Five Women Painters Exhibition).Footnote It was held at Decenta Gallery and Studio, one of the most prominent galleries in Bandung at the time. What was significant about this exhibition was how it foreshadowed the rise of art exhibitions for professional women artists, and how it marked the ‘return’ of a number of the women as professional practitioners.

That the exhibition was held and sponsored by Decenta Gallery likely played a part in endorsing the artists' positions as professional practitioners of fine arts. Founded by A. D. Pirous and his colleagues from the Faculty of Fine Arts and Design (ITB) in 1974, the Decenta Studio and Gallery was a professional, commercial and ‘upscale transformation of the sanggar studios of the 1950s’.Footnote It played an instrumental role in the professionalisation of artists in Bandung and Jakarta by organising and sponsoring exhibitions for them.Footnote

Although signs of female participation in the Bandung art circuit were readily observed throughout the 1960s, the more common outcome was women's temporary ‘disappearance’ from the professional circuit due to marriage and motherhood. For example, Erna, who married her lecturer, A. D. Pirous, in 1964, was unable to accept an offer to work as a teaching assistant due to motherhood responsibilities.Footnote Her first child was still young then, and she and her husband decided that she should stay home to look after the child. This decision, albeit a practical one, shaped the course of her career as an artist. Erna's position in the art world uniquely straddled the private and public spheres, for the sacrifices she made for her family did not go unnoticed. In an essay that celebrated the achievements of A. D. Pirous as a pioneer in Islamic painting, Carla Bianpoen subtly paid homage to Erna's contribution; she wrote: ‘It is said that behind every successful man there is a woman. This rings very true for Pirous, whose wife is Erna Ganarsih, a graduate of the ITB and a painter in her own right’.Footnote Bianpoen and her co-authors did not, however, include Erna in the book Indonesian Women Artists, owing in part to Erna's limited art career.Footnote

Like Erna Pirous, Heyi Ma'mun married a faculty member from ITB, and later became a mother of three. Unknown to many, Heyi continued to make art regularly following her graduation. When A. D. Pirous, her ex-instructor, discovered during a chance visit that she had been consistently making art privately throughout the years, he encouraged her to exhibit her works. In this regard, Five Women Painters Exhibition marked her ‘return’ to the professional art world.

Among the five women artists, Farida Srihadi appeared to be most significantly encouraged by such opportunities, becoming one of the strongest proponents in Indonesia for female professionalism in the arts. The issue of women's conditions had a profound effect on Farida who, like other women who had to contend with double roles, took far longer than most male candidates to complete her studies. She enrolled in 1962, but graduated a decade later. In 1964, Farida fell in love and married her then lecturer, Srihadi Sudarsono, and soon became a mother of three children. Like others, Farida made career sacrifices due to motherhood and marriage obligations. During the early years of her marriage, Farida struggled to look after her young children, receiving little assistance from her family.Footnote For a period of time, she ceased all career development to focus on looking after her children. She took part-time courses in fashion design and French to fulfil her creative and intellectual needs, and worked part-time as an English teacher to privileged families to earn herself an allowance.Footnote

As discussed here, the experiences of motherhood had a direct impact on the development of these women artists, their art and their career paths. The gendered division of labour, argued Gerda Lener, has allotted to women the major responsibility for domestic services and the nurturance of children:

[it] has freed men from the cumbersome details of daily survival activities, while it disproportionately has burdened women with them. Women have had less spare time and above all less uninterrupted time in which to reflect, to think and to write.Footnote

Women's dual roles only gained official recognition following establishment of the Ministry for Women's Role in 1978. However, this did not entail any challenge to the domestic status quo, so deeply entrenched was the prevailing ideology of motherhood and women's corresponding duties within the household. Rather, as observed by scholars on this subject, the dual role's official recognition led to speeches and media interviews that celebrated the rise of professional women in Indonesia who were fully capable of fulfilling their home duties as well.Footnote

Farida's struggles against the kodrat in fulfilment of her aspirations to be an artist were well-known within Indonesian art circles. She said, ‘Society then attended more to male artists, so I have to fight.’Footnote Srihadi Sudarsono belonged to the aristocratic class in Solo and was then a highly regarded artist in Indonesia, while Farida was still a student. He was uncompromising on what he saw as women's primary role.Footnote Dissatisfied with her artistic progress and once her children were less dependent on her, Farida sought out opportunities overseas to deepen her knowledge of the fine arts, and pursued a string of courses via scholarships.

When Farida returned to Indonesia in 1980 with the requisite qualifications to teach, she was offered a position at the Jakarta Art Education Institute (now the Jakarta Art Institute (IKJ)) where she remains a key faculty member. The professional academic position, ironically, gave her more time ‘to be the mother of her children’ and to be the ‘wife of an artist’, while painting, she explained, was typically done at night, by lamp.Footnote She would re-assess the colours under natural lighting each morning.

Subsequently, Farida and Srihadi became key faculty members of Indonesia's third art academy, IKJ. The development of this art academy was augmented by that of Jakarta Arts Center (Taman Ismail Marzuki (TIM)), an arts and cultural centre, which Ali Sadikin, then governor of Jakarta, was keen to develop and reportedly spent much of the provincial budget on.Footnote The Jakarta Arts Council (DKJ) was installed as the organisational cell of TIM, with its members being appointed by the Jakarta Academy.Footnote The director of TIM, Umar Kayam, supported the development of art forms that ‘reflected modernization based on the cultural realities found in Indonesia’, and organised programs in visual art, theatre, literature and music that embraced the avant-garde, ‘including works that criticised the government and society’.Footnote

The timely opening of the art centre and its intimate relationship between TIM and IKJ proved important for women artists who were associated with either institution. It was in such open environments and in the now growing Jakarta art community that Farida met Nunung W. S., and thus began their conversations on developing art exhibitions for women artists.

Nunung's initial struggles to gain institutional training were well known in the art world. Nevertheless, she was described as ‘virtually the only Indonesian woman abstract painter of significance’.Footnote This accolade seemed presumptuous in light of the many talented and active women artists from Bandung discussed above. Yet, the authors knew that few Indonesian women without institutional endorsement or financial support could penetrate into the professional art world. Nunung was certainly one who had irrevocably succeeded in spite of the obstacles she encountered. She failed to gain admission into the two local art academies, and did not have the financial support from her family to develop her interest in art overseas. Instead, her path into the art world was shaped by non-institutional training and by a unique and rare master–student relationship with an influential Indonesian abstract artist, Nashar.

Although Nunung later enrolled in Surabaya's first art academy, Surabaya Academy of Fine Arts (AKSERA), the training she received, by her own admission, was like that of a sanggar (studio). AKSERA was set up in 1967 by a number of passionate artists in collaboration with an art-loving businessman who became the director of the school.Footnote Its semi-formal academic structure was loosely based on the ITB curriculum model and some of the instructors were ITB graduates. As a registered art academy, AKSERA received guest lecturers and established collaborative opportunities with the newly opened art centre in Jakarta. Members of IKJ on study tours to Bali would stop by Surabaya, and it was on occasions such as these that Nunung met with senior artists and key members of the art world, including her future husband, Sulebar Soekarman,Footnote and her mentor, Nashar.

Though such encounters were brief, Nunung apparently left an impression and she would later, following her time at the Academy, meet these people again in Jakarta. This time, she was among the students of AKSERA exhibiting at TIM for the first time. This opportunity opened up a pathway for Nunung, who used her time in Jakarta to seek advice from Nashar and other senior artists, and to partake in the activities that were available in TIM.Footnote Nashar, who had trained under Affandi and S. Sudjojono since he was a teenager, was then a faculty member of the newly established IKJ. Known for his unique abstract style, he taught from 1970 to 1972 and again from 1979 to 1991, and inspired a number of Indonesian artists, including Nunung and Sulebar.

Nunung's training with Nashar officially began in 1972 when he invited her to Bali with him on a sketching trip. They spent two months in Bali, during which Nunung also met with other artists who were there, such as Affandi. Using the box of pastels given to her by Nashar, Nunung tackled the new medium and created countless sketches of Bali with them. This period marked a significant turning point in her life, profoundly impacting her art. While her paintings in Surabaya were compact, in Bali they were simple and full of lines, as observed from the sketches completed during this intensive period under the tutelage of Nashar. Though she was not immediately aware of the developments then, she realised later that this marked the beginning of her process of simplification, which eventually led to the processes of abstraction, a phase that she later developed on her own.

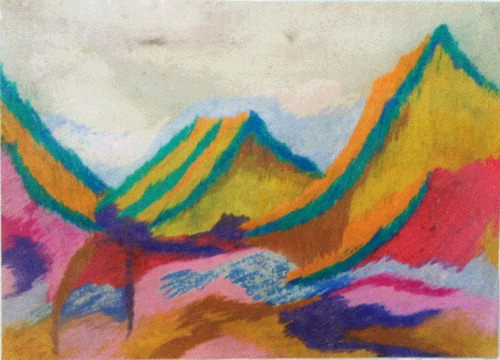

Like Nashar, Nunung used basic media in her sketches, namely charcoal, pastels and ink. Clearly affected by the vibrancy of Balinese cultures and the colours that greeted her in the Hindu temples, Nunung's depictions of mountains and temples, as demonstrated in and , were drenched with bright hues of orange and yellow. During this intense period of sketching and self-development, Nunung was struck by how the change in environment had such an effect on her art. As her ‘painting changed’, Nunung was filled with self-doubt, but she eventually learned to trust Nashar and to regain confidence in her art.Footnote

Figure 1. Nunung W. S., Untitled Sketch, c. 1970s, pastel on paper, 21×29.7 cm. Photo: the author, courtesy the artist.

Figure 2. Nunung W. S., Untitled Sketch, c. 1970s, pastel on paper, 21×29.7 cm, Photo: the author, courtesy the artist.

For Nunung to later become an authority in the language of abstraction in Indonesia, she appeared to have broken the gendered conventions for women in her time, and to have defied her family's wishes. Unlike Farida, she did not have the blessing of her family to become a painter (menjadi pelukis), an aspiration that she had held since she was a young child.Footnote Nunung once professed her devotion to her profession against the commercial market, accepting her artistic calling as a responsibility that demanded sacrifices on her part as a woman. The decision to have only one child was one example. Such public declarations echoed and resonated closely with the well-known writings of S. Sudjojono, who felt strongly against commercial tyranny and who had spoken out about the sacrifices of true artists in the context of nationalism.Footnote For Nunung, exhibiting her works was a significant aspect of demonstrating her commitment to the profession while augmenting her position in the art world as an artist in her own right.

By the 1980s, Nunung had gained clear entry into the Jakarta art world, and together with Farida Srihadi, officially set up Nuansa Indonesia (The Association of Indonesian Women Artists) in 1984.

Nuansa Indonesia: In Support of Professional Women Artists

The key objective of Nuansa Indonesia was to promote the importance of professionalism among Indonesian women artists. Technically, Nuansa Indonesia was not a formal group or society to which an artist could sign up and become a member. The organising ‘group’ loosely comprised a few prominent artists: Nunung W. S., Farida Srihadi, Titik Sunarti Jabaruddin and Kartika Affandi. Footnote

Like many recovery and feminist-inspired projects, the first step was to identify who the Indonesian women artists were.Footnote For their first exhibition in 1985, Nunung has explained that they would go through all the resumes of the artists, mailed in from all around Indonesia, before they made their final selection of 25 artists.Footnote The participants included painters from Jakarta, Bandung, Yogyakarta, Surabaya and Denpasar. The response among women artists was so positive that Nuansa Indonesia was encouraged to continue its activities. For inclusivity, its second exhibition in 1987 extended the selection criteria from painting to include graphics, sculpture and ceramics. With the tactical extension of sisterhood in collaboration with Malaysian artists for their fourth instalment, Nuansa Indonesia aimed to show that women's incapacity to partake as a full member of the community—in this case, as a professional artist—was a common and universal problem.

The Nuansa Indonesia exhibitions did not uphold a women's aesthetic or a feminist art, a strategy that underpinned the direction of more recent woman-centred exhibitions such as Text and Subtext, which was shown in Singapore, Australia, Sweden and Norway (2001–02) or Global Feminisms (2007). Both examples observed a distinction between women artists who had made ‘women's issues’, such as motherhood, the subject or theme of their art, and those artists who pursued other interests (that is, art not about women per se). Nuansa Indonesia participants were generally free to submit any work that was representative of their oeuvre. Sanento Yuliman, an esteemed art historian, remarked that the 1985–1988 exhibitions did not exude any unique ‘feminine’ quality that differentiated the women artists from male artists.Footnote

Here, Nuansa Indonesia exhibitions celebrated women's artworks by opening up the professional art world to women who had proven their commitment to the arts, and by delivering professional women-only art exhibitions in parallel with the male-dominant exhibitions of the time. The exhibitions ensured these artists were included in contemporary dialogue: forums and seminars formed part of the program format; professional catalogues were designed, printed and distributed. Often, they included brief forewords by the organising committee or event sponsors.

For the fourth and final instalment, Farida Srihadi penned the following message:

In this forum we hope to have implanted the notion that creativity in production, as a process of finding ‘individual expression’, is a professional responsibility … Universally, culture around the world is always the product of expression and one form of partnership between men and women, whether direct or not.Footnote

This is consistent with the association's key objective: to promote the importance of professionalism among Indonesian women artists.Footnote Farida's passionate appeal for professional responsibility in the arts was directed at fellow women artists, who were in turn reminded by the Indonesian Government of their peran ganda (double role). As decreed by the Department of Information, women could have ‘the same rights, responsibilities and opportunities as men’, but this should not ‘mitigate their role in fostering a happy family’.Footnote In a similar vein, President Suharto professed that the objective of women's organisations, such as Dharma Wanita, was to ‘guide the Indonesian woman to her appropriate status and role in society, which is to be a housewife as well as a driving force in development’.Footnote Without denying their epistemic identity or refuting their citizenry obligations, both Farida and Nunung were clear on the issue that one's artistic calling was similarly a responsibility that demanded sacrifices on the part of the artist.

In this regard, the two artists unapologetically echoed the artistic visions of influential Indonesian maestros, Sudjojono, Srihadi and Nashar. Srihadi and Nashar were pupils of Sudjojono, and later became the teachers and mentors of Farida and Nunung, respectively. Nunung saw herself as responding to a calling, and saw her chosen profession, as a painter, as inextricably tied to her faith.Footnote It was a profession that demanded sacrifices and hard work, because ‘anyone who wants to become a painter’, as she said to the art critic interviewing her then, ‘must produce a lot of work, read books and exchange ideas with others’.Footnote Her sacrifices, apparently well known by those in the art world, contravened the expectations as dictated by women's peran ganda and kodrat.Footnote It did not, however, contravene the higher calling for the arts by intellectual members of the art community, such as Sudjojono, and her art master, Nashar. In so doing, she had paralleled the paths first taken by male maestros.

It was this unique positioning of Nuansa Indonesia, as a story of personal self-sacrifices of a gendered nature being made for the sake of a greater artistic calling, that enabled the association to garner significant support from the art community, in spite of its critical position and strong feminist message. Further, by then, both Nunung and Farida, due in part to their diligence and personal connections with key members of the intellectual art community, were well and truly part of the Jakarta art world and were able to wield some influence in obtaining sponsorship and the support needed to execute exhibitions of such scale and scope.

Seemingly aware of their precarious position, Farida penned her appreciation and gratitude toward the Dewan Kesenian Jakarta (Jakarta Arts Council) for their support; she wrote:

The faith placed in Nuansa Indonesia on the part of the Jakarta Arts Council in particular is extremely encouraging and gratifying to the group and supplies the motivation to work even harder towards our aspiration to enrich the world of Fine Arts in Indonesia (my italics).Footnote

For all four instalments, the organising committee of Nuansa Indonesia staged an exhibition at prominent locations, stimulated topical discussions among significant cultural and intellectual authorities, and obtained institutional support for their position, namely from the Jakarta Arts Council and Jakarta Arts Center.

Prior to the establishment of the National Gallery of Indonesia in 1995, cultural spaces such as TIM and Balai Budaya (Hall of Culture) were significant exhibiting sites for artists in the Indonesian art world. The organising committee proved to be resourceful and managed to obtain the funds needed to stage four professional exhibitions, for which catalogues were also produced. For the last instalment, the Indonesian Minister of Education and Culture and the Malaysian Minister of Culture, Arts and Tourism each penned a brief message of support. On such occasions, while key personalities—curators, art historians and critics—were invited to pen catalogue essays or give lectures during the exhibition seminar, women's issues and art were vigorously debated and given unprecedented attention.

Exhibiting in the metropolis of Jakarta was traditionally significant for artists who hoped to gain the attention of important patrons such as President Sukarno, ‘well-to-do Indonesian and Chinese art collectors’, the foreign embassies, individual members of the diplomatic corps, and other foreign residents of the capital.Footnote The high cost of financing an exhibition in the capital was one of the biggest obstacles for artists, who depended on cultural associations for assistance and support. Setting up a solo exhibition, a sign of one's standing in the art world and commitment to the profession, took a substantial amount of resources and often, without sponsorship, artists needed to hold dual jobs.Footnote This task proved to be even more difficult for women artists because of their peran ganda. Clearly aware of the many obstacles facing female practitioners, the organising committee of Nuansa Indonesia had hoped that the activities they conducted would provide some relief, if not change, within the system, thereby improving the position of women artists.

The reception and impact of the Nuansa Indonesia exhibitions is difficult to measure, due in part to the often contradictory and ambiguous nature of their feminist position. Nuansa Indonesia argued for greater ‘freedom to express themselves’, which directly challenged the constraints women, on the whole, experienced. Yet, they sought the endorsement of the Minister of State for the Role of Women (as seen in their third instalment), who underscored the nationalist rhetoric of women's kodrat, emphasising that the onus was on women to thus manage their time more effectively in light of the ‘nature of [their] daily chores’. The Minister wrote:

For a nation which continues to develop, all your aspirations and potentials must be developed and utilized to the maximum possible […] although time available to as [sic] women, due to the nature of our daily chores, is relatively short; it is essential therefore that we manage our time effectively (my italics).Footnote

Nonetheless, both Farida and Nunung were heartened by the positive response and interest generated by the events. Ironically, it also brought them unanticipated stress and an increase in workload, all of which took precious time away from their art practice. Though the ‘group’ disbanded just as abruptly and as spontaneously as it had begun, its legacy as a significant arts organisation that fought for women's position made an indelible mark on the women artists in Indonesia.

Some Concluding Remarks

Nuansa Indonesia's contribution to the feminist movement in Indonesia remains ambiguous and warrants further study. The women artists participating in these exhibitions did not share a collective, feminist, artistic or exhibition ethos. Unlike the Jakarta exhibition Women in the Realm of Spirituality (1998), which campaigned for women's rights and social change via art that directly addressed women's issues, Nuansa Indonesia exhibitions did not focus on feminist work. The organising committee merely selected artists based on their commitment to the arts profession, regardless of the subject, theme or content of their art.

Yet, there is no denying that feminist consciousness was present in the way the women artists came together to contest certain restrictions and to reach out to other women artists as a collective. In this regard, Nuansa Indonesia represented the alternate vision that female professional artists could achieve their creative aspirations. What Nuansa Indonesia offered was a platform for women artists to talk publicly about such issues, thus enabling them to enter into a new relationship with the art world at large, and to negotiate new terms for the production and reception of their art.

Forums that were organised from such positions enabled the inclusion of women's subjectivity and lived experiences in debating current issues and problems. It provided the rare opportunity for women artists and their audience to consider how the social construction of gender could impact on the artist profession, and how that intersected with the fundamental problem of the demands and sacrifices of a ‘pure’ artist.

However, the collective positioning to associate with ‘pure’ artistic practice inevitably reinforced the amateur–professional divide, maintaining an ideological distance and difference with the many women-centred networks that promoted art development as supplementary to women's lives. Organisations such as Grup Sembilan (Group of Nine) and Ikatan Wanita Pelukis Indonesia (Indonesian Women Painters Association) were often considered as gatherings of ‘Sunday painters’. Carla Bianpoen maintained that such a put-down was ‘not altogether fair’, as the members of Grup Sembilan were active artists, both local and expatriate women, and most had a background in art education, but were unable to be full-time artists due to their responsibilities as married women.Footnote Astri Wright described Grup Sembilan as ‘semi-professional’, given that a number of them partook in Nuansa, and other major, art exhibitions. Yet, the positioning of these as ‘ibu-ibu’ (ladies') groups resulted in women artists distancing themselves from such associations, professional or otherwise.Footnote

Nuansa Indonesia insisted on the distinction between professional and amateur women artists, and aimed to raise the profile of the former through a series of exhibitions and panel discussions. Its feminist position, which was derived from a combination of its founders' personal experience and knowledge of the art-world system, paradoxically divided the group from other artistic women artists and women-only groups, who were similarly unable to achieve creative aspirations due to the gendered constraints in their lives. In this regard, they may share a similar gender-based problem, but they approached the issue in markedly different ways.

The formation of women-centred networks such as these was nonetheless crucial for women artists to come to terms with the nature of their oppression. As Gerda Lerner has shown, sex-segregated social space became the terrain in which ‘women could confirm their own ideas and test them against the knowledge and experience of other women’, and in so doing help ‘women to advance from a simple analysis of their condition to the level of theory formation’.Footnote Women artists, as shown here, have undoubtedly taken the first step toward understanding their conditions and re-modelling the art world.

Notes

1. Miranda Goeltom, ‘Foreword’ in Indonesian Women Artists: The Curtain Opens, ed. Carla Bianpoen (Jakarta: Indonesian Arts Foundation, 2007), 6.

2. Ibid., 6.

3. See Wulandani Dirgantoro, ‘Defining experiences: Feminisms and contemporary art in Indonesia’ (PhD diss., University of Tasmania, 2014). The author argued that feminism was already a distinct discourse in Indonesian visual arts and its traces are evident in the artists’ views on issues such as the body, private space, art-making, medium and memory.

4. Ibid., 280.

5. Ibid., 185.

6. This issue was critically studied in Dirgantoro's dissertation, which addressed the definition, understanding and adaptation of feminist techniques in Indonesian visual art discourse. See also brief discussions of this issue in the following essays: Carla Bianpoen, ‘Introduction’ in Indonesian Women Artists, 22–34; and Saparinah Sadli, ‘Feminism in Indonesia in an International context’, in Women in Indonesia, Gender, Equity and Development, ed. Kathryn Robinson and Sharon Bessell (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2002), 80–91.

7. Saparinah Sadli, Berbeda tetapi Setara (Jakarta: Kompas, 2010). See Sadli, ‘Feminism in Indonesia’, 470–483. Sadli maintained that this decision was made to avoid unnecessary irritation within the academic community.

8. Heidi Arbuckle, ‘Performing Emiria Sunassa: Reframing the Female Subject in Post/colonial Indonesia’ (PhD diss., University of Melbourne, 2011), 81.

9. Cited in Corma Pol, Discourse on the Frame: The Making and Unmaking of Indonesian Women Artists (Amsterdam: Akademische Peers, 1998), 63. The exhibition he was critiquing was by Nuansa Indonesia.

10. Apart from Linda Nochlin's seminal essay, ‘Why have there been no great women artists?’ [1971] in Art and Sexual Politics: Women's Liberation, Women Artists, and Art History, ed. Thomas B. Hess and Elizabeth C. Baker (New York: Collier-Macmillan, 1973 [1971]) 1–43; other notable sources discussing this issue include: Whitney Chadwick, Women, Art and Society (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2007); and Griselda Pollock and Parker Rozsika, Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981).

11. Gerda Lerner, The Creation of Feminist Consciousness from the Middle Ages to Eighteen-Seventy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 14.

12. Ibid.

13. For example, Setianingsih Purnomo observed that ‘Rakyat kecil’ (common people) was a primary subject matter in the first decade of modern Indonesian art but ‘disappeared’ during the political change from the Old Order to the New Order. See ‘The Voice of Muted People in Modern Indonesian Art’ (Master's thesis, University of Western Sydney, 1995).

14. Ibid. Following the ‘failed’ political ‘coup’ on 30 September 1965, which marked the fall of Sukarno and his Old Order, Suharto assumed control of Jakarta and began a campaign ‘to inflame smouldering class and religious tensions’. The left-winged cultural institute LEKRA was outlawed and the painters it supported were killed, imprisoned, or suppressed. See Claire Holt, Art in Indonesia: Continuities and Change (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1967); and more generally of the political events, Saskia Wieringa, Sexual Politics in Indonesia (Palgrave: ISS, Institute of Social Studies, 2002).

15. Wieringa, Sexual Politics in Indonesia.

16. See, in particular, chapter ‘Concerning our Women’ in Soeharto: My Thoughts, Words, and Deeds: Autobiography as Told to G. Dwipayana and Kamadhan K.H., trans. Sumadi Muti'ah Lestiono (Jakarta: Citra Lamtoro Gung Persada, 1991), 256–260 (my italics).

17. Nira Yuval-Davis, Gender and Nation (London: Sage Publications, 1997), 37.

18. According to Farida, Ardha has ‘disappeared’ from the art world and has not kept in touch with the other artists (interview with the author, Jakarta, January 30, 2013).

19. Kenneth M. George and Mamannoor, A.D. Pirous: Vision, Faith and a Journey in Indonesian Art 1955–2002 (Bandung: Yayasan Serambi Pirous, 2002), 74–5.

20. Ibid.

21. This position was then given to her classmate, Umi Dachlan, who never married, and became the first female lecturer at the art academy.

22. Carla Bianpoen ‘AD Pirous: Islamic Painting Pioneer’, The Jakarta Post, March 17, 2012, unpaginated.

23. It is certainly not the intention of the book to include all women artists, but as indicated in chapter one, the qualitative criteria imposed by the authors on the selection process would necessarily exclude Erna Pirous.

24. Interview with Farida Srihadi (Jakarta, January 30, 2013).

25. Interview with Farida Srihadi (Jakarta, January 30, 2013) and with Heyi Ma'mun (Bandung, December 13, 2012). Both expressed that it was not uncommon for women to suspend their studies due to marriage and motherhood.

26. Gerda Lerner, The Creation of Feminist Consciousness, 11.

27. Susan Blackburn, Women and the State in Modern Indonesia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

28. Interview with Farida Srihadi.

29. Ibid. Srihadi Sudarsono was born in Solo in 1931 to a priyayi (noble) family, respected for the family's knowledge in kris. See his monograph: Jim Supangkat, Srihadi dan seni rupa [Srihadi and Art in Indonesia] (Jakarta: 1 New Museum, 2012).

30. Interview with Farida Srihadi.

31. Jim Supangkat, Srihadi dan seni rupa, 182–183. It also housed archival documents on Indonesian literature collected by prominent literary critic H. B. Jassin.

32. Between 1968 and 1975, administrative and cultural buildings such as theatres, galleries and a planetarium were erected. Art festivals showing works by artists from Bandung, Jogjakarta and Jakarta were held.

33. See Jim Supangkat, Srihadi dan seni rupa, 182–183.

34. Carla Bianpoen et al., Indonesian Women Artists: The Curtain Opens, 213.

35. See Rudi Isbandi, Perkembangan Seni Lukis di Surabaya Sampai 1975 (Surabaya: Dewan Kesenian Surabaya, 1975). See also my interviews with Nunung W. S. and Sulebar Soekarman (Yogyakarta, December 4, 2012).

36. Interview with Nunung W. S. and Sulebar Soekarman.

37. Ibid.

38. Ibid.

39. See section on Nunung W. S. in Pol, Discourse on the Frame, 18.

40. See original text, S. Sudjojono ‘Seni Loekis di Indonesia sekarang dan jang akan datang’ [The Art of Painting in Indonesia Now and in the Future] in Seni Loekis, Kesenian dan Seniman [Painting, Art and the Artist] (Jogjakarta: Indonesia Sekarang, 1946), 1–9, and translated sections in Claire Holt, Art in Indonesia, 196.

41. Its founding took place spontaneously, with the intention of initially showing two women artists (Nunung W. S. and Titik Sunarti Jabaruddin) by DKJ and TIM. Farida Srihadi, who was then teaching at IKJ, was invited along. The concept of a women's organisation took shape and Kartika Affandi was invited to be their consultant. Sulebar and Srihadi were involved in the discussion and provided support. Interview with Nunung W. S. and Sulebar Soekarman.

42. Ibid. As part of the DKJ effort to document the art developments of Indonesia, a database of artists was slowly being built and Sulebar, who was involved in this project with DKJ, was able to furnish Nunung with a list of over 1,300 artists.

43. Ibid.

44. Sanento Yuliman, ‘Women and the Fine Art in Indonesia’ in Nuansa Indonesia III (Jakarta: Percetakan Gramedia, 1988), 8–11.

45. See catalogue: Nuansa Pameran Seni lukis wanita Indonesia-Malaysia (Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Kesenian Jakarta and Balai Seni Lukis Negara, 1991), unpaginated. Selected text translated by Siobhan Campbell.

46. Similar messages can be found in the 1987 and 1988 Nuansa catalogues, in which Farida wrote of women's struggle to become professional. The 1988 exhibition was reviewed by Astri Wright, who observed that the term ‘professional’ was central in the discussion about Nuansa Indonesia; it was a term that conveyed the connotations of being serious and dedicated to one's practice. See articles, ‘Nuansa Indonesia moves towards professionalism’, Jakarta Post (November 30, 1998): 6 and ‘Nuansa Indonesia enriches local art scene’, Jakarta Post (December 1, 1988): 6.

47. Cited in Pol, Discourse on the Frame, 20. In The Women of Indonesia (1990), as stipulated by the Department of Information: ‘1: Overall development requires maximum participation of men and women in all fields. Therefore, women have the same rights, responsibilities and opportunities as men to fully participate in all development activities. 2: The role of women in development does not mitigate their role in fostering a happy family in general and guiding the young generation in particular, in the development of Indonesia in all aspects of life.’

48. Soeharto, Soeharto, 260. See also Julia I Suryakusuma's critical essay on how the state controlled sexuality using Dharma Wanita as one of its agencies to espouse the gender ideology of ‘State Ibuism’. Julia I Suryakusuma, ‘The State and Sexuality in New Order Indonesia’ in Fantasizing the Feminine in Indonesia, ed. Laurie J. Sears (Durham: Duke University Press, 1996), 92–116.

49. Both Corma Pol (Discourse on the Frame, 1998) and Carla Bianpoen (Indonesian Women Artists, 2007) have variously discussed Nunung's devotion to the Islamic faith—she performed the shalat, and created from her inner experience, and needed the daily acts of worship to activate this source.

50. See section on Nunung W. S. in Pol, Discourse on the Frame, 18–71. Pol referred specifically to the article by Sangpoerwaning, ‘Nunung Wachid Saat: Wanita Pelukis Warna-Warni’, Minggu Pagi 26 (October, 1988): unpaginated.

51. For example, Pol highlighted an interview Nunung conducted with Muhammad Ali (first published in Surabaya Pos, July) in which she spoke about how her career gave her satisfaction but also demanded many sacrifices. Nunung, whose sacrifices would necessarily be different from those of others, spoke about having to participate in exhibitions, marrying a man who really understood her, and choosing to have only one child.

52. Farida Srihadi ‘A few notes’, Nuansa Indonesia III (Jakarta: Percetakan Gramedia, 1988), 1 (my italics).

53. Claire Holt, Art in Indonesia, 246.

54. During her time in Indonesia, Claire Holt (Art in Indonesia, 244) observed a hierarchy of painters in which the highest-ranked were Jakarta's artists (wealthy salon and palace painters) and the lowest-ranked were becak painters.

55. Statement by the Minister of State for the Role of Women, Mrs A. Sulasikin Murpratomo, in Nuansa III (Jakarta: Percetakan Gramedia, 1988), 5 (my italics).

56. Carla Bianpoen et al., Indonesian Women Artists, 22–33.

57. Astri Wright, Soul, Spirit and Mountain: Preoccupations of Contemporary Indonesian Painters (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1994), 130. The author remarked that some artists did not want to exhibit even with Nuansa because of such classification—another ‘ibu-ibu’ (ladies’) group (‘ibu’ means ‘mother’).

58. Gerda Lerner, The Creation of Feminist Consciousness, 279.