In 1956, Sidney Nolan spent a day exploring the Gallipoli peninsula. Though brief, the experience crystallised in him the historical significance of the Dardanelles. ‘I stood on the place where the first ANZACs had stood,’ he later recalled, ‘looked across the straits to the site of ancient Troy, and felt that here history had stood still.’Footnote1 At the time Nolan had been reading Homer's Iliad, and was wrestling with how to reconstruct the grand, heroic narratives of classical mythology for a new time and a new place. On the shores of Gallipoli, where Australian troops had themselves reprised the campaigns of Xerxes and Agamemnon, he found inspiration.

In the dense void of Nolan's The Galaxy (1957–58) () – one of the earlier paintings from the Gallipoli series he began in the mid-1950s and pursued for two decades – we see a pastiche of historical and aesthetic reflections on war and its aftermath. Looking at the ethereal forms of naked Australian soldiers drifting rhythmically across the surface of the painting, we are gripped by the melancholy with which Nolan looked back on the tragedy of the First World War. But the image also speaks of contemporary anxieties. The eddies and swirls that animate the work were intended by Nolan to evoke the interior of an atom, a potent symbol of force and fear in a post-war world haunted by the spectres of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And yet the anxieties may have also been deeply personal: Nolan's brother Raymond had drowned while on service shortly before the end of the Second World War. Nolan's confidante, Patrick White, who believed the work was proof that Nolan was Australia's greatest creative painter, read it best. Drawing back from the microscopic lens towards the telescopic, he read the swirls as the Milky Way set against a limitless blackness that had enveloped the events at Gallipoli under the auspices of a shared narrative of human history. In this sense, above all else, Galaxy offers one great gift to its viewer: perspective.

Figure 1. Sidney Nolan, The Galaxy, 1957–58, synthetic polymer paint on canvas on hardboard, 193 × 256 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Australia. © The Trustees of the Sidney Nolan Trust. Bridgeman Art Library.

A century after Nolan painted The Galaxy, the turbulent subatomic physics he depicted provide a new and unexpected orbit from which to map the artist's autobiographical ambiguities. As detailed by Paula Dredge et al. in the essay that opens this issue, ‘Unmasking Sidney Nolan's Ned Kelly: X-ray Fluorescence Conservation Imaging, Art Historical Interpretation and Virtual Reality Visualisation’, in 2016 an interdisciplinary research team encompassing art history, conservation science, and particle physics subjected another of Nolan's paintings, his Ned Kelly: ‘Nobody knows anything about my case except myself’ (1945) – which features possibly the artist's first use of the iconic black mask motif to depict the outlaw – to an experimental elemental mapping technique at the Australian Synchrotron particle accelerator in Melbourne.Footnote2

The team was acting on an art historical hunch that more lay beneath the mask than meets the eye, but traditional modes of material investigation could not penetrate the artists’ dense paint medium. However, at the Synchrotron's X-ray fluorescence beamline, atoms accelerated to near-light speed were directed through the painting to digitally map its elemental layers. The result of this atomic parsing: beneath the mask is indeed a face, and the beginning of new avenues of art historical enquiry about Nolan's self-perception, autobiography and aesthetic development. To what extent did Nolan employ the iconography of Kelly to formalise a truly Australian cultural mythology and how did he re-parse familiar narratives in new contexts? The digital mapping provides new data for these enquiries.

Like in The Galaxy, this new network of atoms can also be read more broadly, in this case as a constellation of concerns surrounding experimental digital methodologies for the conduct of art historical research. How must disparate institutions and professional disciplines collaborate to facilitate this research? What are the boundaries and future directions of the discipline? To what are the new forms of data, created natively through digital research – the textual metadata, game engine builds, augmented documentation, 3D models and digital scans that provide a body of material I call metamateriality for its ability to both belong to the original and provide a new artistic aesthetic – beholden?

A methodological shift in art history has already begun, driven in part by the grassroots adoption of new modes of viewing and interacting with visual cultural materials facilitated by the domestication – with breath-taking speed – of cutting-edge and almost magical, transformative technologies. These have already found their way into exciting research projects in the field now known as digital cultural humanities, which broadly encompasses such activities as the creation of intelligent artwork databases, networked collection access and visualisation, site and object reconstruction, museum digital interactives, large-scale exhibition installations and the creation of a new form of inter-subjectivity through the employment of virtual reality interfaces.

These technologies, until recently the bastion of technologists or niche industry professionals, are now championed by the most influential tech companies in history and are rapidly being integrated as natural human computer interfaces in core modes of social interaction and visual communication. The ubiquity of social media platforms and the rapidity of their evolution to accommodate the materialities, formats and hardware requirements of a dazzling array of new media types has produced new networks for the creation, transmission and trafficking of images in real time and across the globe. The implications for the existence of these channels are profound: visual culture has become networked and fluid, and evolves in real-time. Which is to say, for the next generation of art historians, the now niche specialisation known as digital art history will simply be known as art history.

The Ekphrasis Engine: A New Computational Engine for Art Historical Practice

The essays in this issue present a number of case studies in which virtual and simulative methodologies such as 3D modelling, gamification, interactive environments, experimental imaging and immersive visualisations have been employed, in conjunction with established art historical and museological practices, so as to interrogate particular moments in the lives of objects and the built environments that were designed for their encounter. They variously reconstruct and simulate lost or rediscovered works of art and architecture, as well as speculate on the viewing modalities engendered by particular works of art, and the social structures around which the originals were produced. In doing so, they add to the growing list of projects that demonstrate the successful application of investigative digital methods to material and cultural research in the arts.

However, the intention of this issue is not to simply present the achievements of Australian researchers in this field, a singular novelty in the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, the most established forum for art historical research in Australia. It expands, through the documentation of real-world industry practices and design workflows, to also offer the following provocation to the discipline of art history. With increasing rapidity, the contexts in which visual cultural information is created and consumed, and the questions of aesthetics, affect, social history and culture-making once thought to be the domain of the art historian or art theorist, will be posed and answered in fields once thought to be outside the purview of traditional art histories. Readers will observe this diversification in action in the list of contributors to this issue: particle physicist, conservation scientist, virtual reality designer, archaeologist, spatial designer and artist.

Because of this, we must produce new generations of art historians who break disciplinary boundaries in order to expand the relevance and influence of the discipline of art history itself. This requires us to not only experiment with new investigative methodologies, but to reconsider the entire industry through which art historians are trained in universities and their research disseminated through journals, books, digital formats and, more widely, cultural institutions.

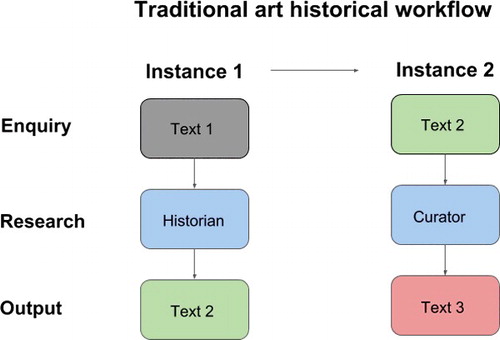

Putting aside instrumentalist questions of the value and purpose of cultural research, all industry workflows might be thought of in procedural terms as computational engines that, at various stages, are fed inputs and deliver outputs. Art history has long relied on a strong verticality of singular authorship and interpretation. Its primary inputs are object and archive (). The interrogation of a work of art is informed by textual records, historical accounts, audience perceptions, the subjectivity of the researcher and so on. Typically, an art historian parsing this data produces a new literary text – be it a journal article, book, or exhibition catalogue – interpreting the original, which is then fed back into the engine as a new possible input for interrogation and meta-criticism, usually within a relatively small, hyper-specialised field. In an alternative pipeline instance, a museum curator or artist might then encounter that new text, feeding its knowledge into the production of their own exhibition or artwork, through which knowledge reaches a broader public. Cultural fertilisation and public engagement occur slowly across professional structures whose outputs are carefully delineated by role and convention.

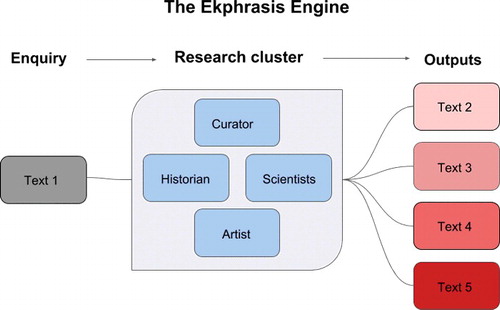

In the context of this issue I propose a new, networked industry architecture for the conduct of digital art history that is transdisciplinary and natively generative across multiple output formats. It is a workflow that begins with the same inputs as the traditional art historian – the object and archive – but whose computational engine cannot function without the alliance of multiple discipline partners allied in one research cluster, and whose outputs shift organically as this cluster is configured and reconfigured. I call this the Ekphrasis Engine, as both as a nod to the foundational rhetorics and lyricism of the discipline of art history as a translation between two forms of human text, and as recognition that the production of digital art histories involves a new form of poiesis, in which the study of human making leads itself to evolutionary forms of production and thus new objects. To illustrate this with respect to the particular workflow demonstrated by Dredge et al., I borrow the paradigms of visual programming languages employed in computer science engineering to reconceive of texts, discipline-based methodologies, and research outputs each as different types of node – computational functions whose algorithms may be daisy-chained endlessly between inputs and outputs to produce new functions. Naturally, the characteristics of each node determine their individual algorithm: art historians parse visual objects through cultural filters; scientists conduct experiments, consider recorded data and produce empirical analyses; curators consider relationships between object and viewer and deliver exhibitions. ().

This new computational engine simultaneously produces outputs relevant to all nodes in the cluster: interpretive text, scientific knowledge, new artwork and metamaterial imaging that both documents and interprets the original. In this constellation of materialities and platforms we must also consider the role of the publisher, traditionally present in the humanities as text- and series editors nominally focused on the print industry. Their role too must expand to be central to the academic enterprise as multi-platform content curators, who identify strategies for dissemination to enhance content engagement with a wider public. It is thus possible that a single art historical enquiry might become a central pillar in investigating a question of the human condition across a range of fields, this knowledge emanating from the original object but untethered to its historical object-life in perpetuity. I conceive of the Ekphrasis Engine as natively generative in that it is functionally transdisciplinary, where the production of new, digital artefacts of visual culture, and the consideration of their engagement with users and audiences, are critical components of art historical enquiry.

This should not be read as a diminution of the role and work of the art historian – it is quite the opposite. Instead, the art historian takes on a directorial role as a designer of research and user experience. The design and construction of this workflow engine is essential to the successful conduct of research, and the essays in this issue all describe the design choices, which Tom Chandler et al. argue, in ‘A New Model of Angkor Wat: Simulated Reconstruction as a Methodology for Analysis and Public Engagement’, ‘are as important as the final result’ made in achieving their outcomes.Footnote3 A network of decisions must be made to link object input with research output, to take into account the audience for the finished work and the mode in which they engage with it. When thinking about the virtual reality interactive described by Dredge et al., I was prompted to ask how interactive actions in a visualisation platform – totally novel to most users – could be enacted in a mode that mimicked lived and expected behaviour in the visualised space. In her essay, ‘What Could Have Bean: Using Digital Art History to Revisit Australia's First World War Official War Art’, Anthea Gunn considers how contemporary viewers might encounter modes of spectatorship designed for the 1920s. Chandler et al. consider how long a user can view a scene before the simulation begins repeating itself. And so on.

The links between process and simulation are thus central to the conduct of this new form of art history, as the outcome itself mimics the workflow processes of its creation – the digital art historical engine. Such simulations are not exactly predictive models: ‘they may be conceived of as a ‘hypothetical machine’, Chandler et al. argue, that ‘opens new lines of enquiry among the domains of data, virtuality, and art history’.Footnote4 Simulation, rather than simple animation, they suggest, allows the reconstruction to accommodate competing hypothetical theories in the future, positioning digital historical reconstructions as a new form of dialogical text in which debates can be staged in real-time.

An Expanded Constellation of Concerns for Digital Art Historical Production

The essays in this issue present the field of digital art historical research as it manifests in its industry context. All of the research projects presented herein originated at research institutions, but were exhibited at or facilitated by some of Australia's most important collecting museums, galleries and libraries. The practical execution of digital art history thus represents a convergence of the roles that cultural research and exhibiting institutions perform, which necessarily requires a discussion of the challenges of intra- and inter-institutional practices. The essays in this issue evidence a new form of digital staging; and yet stages require actors and audiences. Digital interfaces require users.

University research clusters are in general not geared towards the large-scale, public dissemination of accessible exhibition content and impactful engagement with a broader public consisting of general, rather than specialised, audiences. Here, partnerships within the galleries, libraries, archives and museums sector become vital points not only as repositories for cultural heritage but as nexuses of engagement, interaction and, eventually, debate. Conversely, Australian collecting institutions benefit from the specialised content knowledge that dedicated university researchers can bring to particular collection areas. In Australia, every major state gallery and museum hosts a department dedicated to digital engagement that is variously engaged in the production of web content, event information, in-exhibition interactives, video content and social media. They are variously located intra-institutionally; mostly within marketing or public engagement divisions, occasionally lumped alongside IT departments. Yet, in spite of the fact that digital art history research engages directly with the politics of display and collection, digital museum practice in Australia is not institutionally identified as a curatorial discipline, which I believe stunts the ability of researchers and gallery practitioners to deliver meaningful content, thus freezing museological practice within anachronistic conventions of display, engagement and professional practice.

These considerations are evident in Gunn's essay, which distinguishes itself for being an institutionally curator-led, digital reconstructive project undertaken at the Australian War Memorial, which evidences the deep connections and potential for digital technologies to activate collection knowledge, and which questions the identity of the institution itself. The site for reconstruction is an earlier iteration of the Memorial, commissioned for a 2017 exhibition at the Memorial, titled Art of Nation, during the centenary commemorations of the First World War. Its design decisions were made in consideration of the contemporary audiences of the Memorial, in effect offering an alternative perspective on the historiography of Australian war memorialisation.

Gunn's essay details the construction of a fully navigable vision of how Australia's official war correspondent and historian Charles Bean originally conceived of the Memorial in the 1920s as a grand neo-classical revival building filled with history paintings solely devoted to the First World War. It thus reconfigures the life of the building in Australian history as a high art gallery with national scope, rather than the predominantly object-based museum it is today, and allows for new perspectives to be read into Bean's vision and his role not only as official war historian, but as an advisor to the Official War Art scheme. As Gunn argues, it also sheds light on a particularly stark reality: ‘the museum was to be a memorial to one conflict, the “war to end all wars”.’Footnote5

In this case, digital reconstruction is the only possible method through which the original curatorial vision of the institution could be fulfilled. It offers a new form of historical and contemporary spectatorship. It also demonstrates value of digital methodologies as collection mapping, visualisation and augmentation strategies. Art of Nation visualises over 70 paintings commissioned by Bean, which are linked to 400 mapped field sketches in the Memorial's collection. User interactions with paintings generate content links to contextual information about the images.

It also puts into context important historical tensions evident in the Memorial's collection. For example, it highlights the Memorial's original intent in justifying certain war trophies, including the excavation of the Shellal Mosaic, a sixth-century mosaic floor taken from Palestine by the 2nd Light Horse Brigade.

Architectural reconstruction is among the chief interests for digital art historians. Yet, as Chandler et al. demonstrate in employing more holistic simulation strategies to the interrogation of Angkor Wat and its surrounding site, advances in digital visualisation techniques offer new perspectives to art historians and researchers that lie outside the museological contexts in which artefacts are normally encountered. They argue that static interpretations and reconstructions, particularly in the field of archaeology, while necessary are insufficient to providing understanding of the socio-cultural context of a work of art. Models of Angkor Wat have existed since 1860, when a replica was exhibited in the Royal Palace grounds in Bangkok. These position the temple as an isolated artefact, a methodology that ‘deserves to be discarded’, as new augmented techniques allow pluralistic reconstructions of the site and its human use, placing it in its temporal and functional context.Footnote6

Chandler et al. detail the important design decisions made in simulating the cultural life of Angkor Wat over a single day, offering real insight into an overarching tension present in digital historical reconstruction: how to balance the strictures of scholarship with the realities of visualisation and the need for public legibility.Footnote7 In this case the simulation arose from new material discoveries. Their model accounts for the 2013 detection of wooden buildings within the temple's enclosure, remotely sensed through light detection and ranging scanning, a key driver of the contextual reconstruction that demonstrates its necessity. The newly discovered wooden infrastructure prompted speculation of the diversity of historical vegetation, wooden residences and accompanying ecological and cultural soundscapes, which each included consideration of the temple as a living landscape, with the population considered an integral part of the model. The reconstruction of these people models, too, is informed by traditional historical analyses and evidence: bas-relief sculptures, for example, provided a source for the interpretation and visualisation of clothing.

Chandler et al. dealt with the gap between historical fact and informed visual speculation by integrating it into their methodology. Speculation was essential: extant archaeological evidence indicated the location of structures but not their design. Thus, in the case of the innumerable assets that are required for visualisation in the simulation engine, certain procedural variables – such as building material possibilities, variances in population behaviour and movement routes by class – are randomised at start-up to naturally indicate the visual speculation within the simulation. The result is in fact a new form of dialogical text. As newer and better data becomes available the simulation can be adjusted to suit, which immediately feeds into its public presentation. In 2017, when the simulation was exhibited at the Hargrave-Andrew Library at Monash University, it cycled through its own self-contained world according to the real-world time of day, signalling its status as a living and evolving history-scape.

The deep and complex methodological considerations of object reconstruction and simulation are detailed in Feneley's essay ‘Reconstructing God: Proposing a New Date for the West Mebon Viṣṇu, using Digital Reconstruction and Artifactual Analysis’. It presents the significant technological and methodological achievement of digitally reconstructing, through painstaking visual analysis, the West Mobon Viṣṇu, a large bronze sculpture of great spiritual, historical and political significance found broken and buried in 1936, over 60% of which is missing.

The West Mebon Viṣṇu is an artwork, Feneley argues, that ‘Surprisingly, given its prominence in every book on Southeast Asian art history … has never been fully examined in its archaeological context’.Footnote8 Feneley details the processes and historical considerations undertaken in reconstructing the sculpture through photogrammetry and 3D immersive gaming platforms. Using an interdisciplinary approach that combines digital art history and archaeology, she is able to shed light on the contextual relationships between the statue and its geographical and political contexts, as well as on its status within Khmer religious practices. Importantly, in doing so she is able to offer a reappraisal of the statue's date of commission and execution; digital reconstruction thus creates a new vector by which physical, material history can be re-evaluated, while still offering the possibility for flexible analysis as further data is discovered.

Feneley's process in digitally reconstructing the lost fragments of the sculpture is meticulous. Where possible, surviving pieces of the statue were weighed, measured and scanned to provide the base point for digital reconstruction. The reconstruction was then informed by comparative studies of similar iconographies of Viṣṇu, as well as Khmer religious traditions. This data included considering 100 examples of images of Viṣṇu reclining, gathered from the territories of the Angkorean Empire. Made more difficult by the lack of any example of an intact 3D representation of Viṣṇu Anantasain in Khmer art, Feneley found a solution by employing bas-relief carvings as a stylistic armature. While rigorous, the digital reconstruction technique offered numerous advantages over traditional sculptural reconstruction techniques. In reassembling fragmented pieces, the ability to edit in 3D, to rotate and experiment with 3D placement of fragments, was instrumental. Reconstruction complete, the statue was re-sited in context, which required the modelling of the West Mebon Temple and its activation within a video-game engine.

Performative Cultural Visualisation: User Agency and Hermeneutics

The constellation of roles and concerns engaged in producing digital art histories means that art historians will increasingly perform a role not only as interpreters of visual material and its context, but as user experience designers for new creative outputs. The particular discipline of site modelling and simulative reconstruction that informs all the papers in this issue, in which historical context is literally staged and performed by digital actors, introduces a new form of performativity to the processes of art history. As Susanne Thurow argues in her ‘Response to the Metamaterial Turn: Performative Digital Methodologies for Creative Practice and Analytical Documentation in the Arts’ – following the essays and reviews of this issue – these new methodologies herald steep changes for artistic practice; they ‘performatively call on viewers to assume an active role in the process of knowledge creation’, shifting the focus of content production towards the aesthetics of interface design. Viewers of art become ‘users’ of installations, galleries.Footnote9

Employing simulative methodologies places greater weight on considerations of the user. As Chandler et al. argue, it requires asking how designers call on users to look at, and act upon, cultural heritage objects: ‘would players require goals and a virtual guide to direct them through a series of premeditated events? These questions had implications regarding whether the venture would become a ‘serious game’ of virtual heritage, with the attendant considerations of agency and hermeneutics.Footnote10 In effect, in reconstructing the contexts for looking at art, we must better understand the processes of looking itself.

The hermeneutics of viewer activity is precisely the subject of Soheil Ashrafi and Michael Garbutt's essay, ‘Looking at Looking: Two Applications of a Hermeneutic Phenomenological Analysis of Head-mounted Eye-tracking Data in Gallery Visitation’, in which they employ digital technologies to assess the experience of spectatorship for a visitor using new metrics for user engagement. While the tracking of gaze patterns while looking at art has been the subject of scientific study in the past, the vast majority of such eye tracking studies, which are laboratory-based, focus on the mechanics of visual effect. Garbutt and Ashrafi argue for combining eye-tracking data with a hermeneutic phenomenological analysis of the embodied experience of viewing paintings in a gallery, in order to situate activity in context.

Their essay provides a potential model for assessing action and experience in virtual and public spaces. Using data from a head-mounted, mobile eye tracker and an accompanying audio recording of a subject's running commentary of their search to locate two paintings by Picasso in the Art Gallery of New South Wales, they employ Martin Heidegger's fore-structures of existential and concrete situatedness to model the situated visual behaviour. Within this framework, they identify three hermeneutic elements: ‘action’, ‘thought’ and ‘mood’, whose fluid relations with the Gallery's architectonic and curatorial design inform their reading of the eye-tracking data.

The resultant implications for professional practice are twofold. Firstly, the hybrid experiment provides a diagnostic tool for assessing and mapping visitor experience and spatial behaviour. Secondly, they argue, it provides an interactive experience itself, resulting in visual information in the form of gaze-patternation, that can be leveraged as an artistic medium. Visitors thus become active producers of images, enabling them to reflect on current visual practices and imagine new ways of seeing and being.

What emerges from Ashrafi and Garbutt's experiment is a reflection on the performative and generative modalities of digital art research and engagement with its outcomes. Thurow summarises the potentialities of contextual knowledge creation afforded by new media platforms that have been evidenced by the case studies that precede her: they provide ‘expanded, malleable, and rapid data access; [exploit] embodied spatial cognition; and [deliver] interactive as well as networked capabilities’.Footnote11 These are somewhat new methodological challenges for the conduct of art history in particular, though they have been dealt with in some detail by other disciplines. This is the reason for the response provided by Thurow, in which she signals possible new avenues for the development of this new creative practice by examining parallel developments and trajectories that have evolved from similar digital design in the performing arts.

In interrogating these aesthetics, Thurow appraises the capabilities and constraints of the digital methodologies currently employed in the cultural humanities. The employment of digital platforms brings its own aesthetic and visual language, she argues, which in the performing arts has at times been incorporated into resultant public practice, but which remains a tension in art history. The production workflow of digital reconstruction is detailed using the design case studies of the theatre bauprobe and the impact of lighting technology on the methodology of stage design, and subsequently digital performative practice. She assesses the strengths and limitations of current, industry-standard software packages, and provides a model for a new kind of collaborative, immersive digital design platform being engineered at the University of New South Wales that has the potential to link cultural collection data in museums and theatres to simulated environments useful across digital cultural practice.

Her perspective is useful because, as I have also argued throughout this introduction, a transition is underway in digital art historical practice that both widens the scope of the discipline and requires rapid solutions for the industrial challenges this change presents. We are already past the point where it can be debated whether experimental digital approaches to art history serve or debase the objects the discipline reveres. Within new generations of users who are born digitally native, new expectations have arisen governing not only how they expect to interact with real objects and consume information about them, but as to what constitutes an authentic object or cultural heritage material in the world of the virtual in the first place. Virtual does not mean unreal. The inhabitants of digital universes – from Facebook to Instagram to Oculus Rift to World of Warcraft – give their transactions substance through deep devotion to the meta-reality of their platforms. New social etiquettes of behaviour and interaction mean that the content of the virtual is conceptually and socially as substantial as the real.

The discipline of art history must respond to the modalities of the present, not only if it is to maintain its ability to speak its message to new audiences in their native language, but if it is to document and interpret the new forms of art that have arisen in response to the mediums of the digital and virtual themselves – such as post-internet art, which can alternatively take the web as its medium, or as a cultural commodity whose identity can be interrogated or subverted, or its icons subjected to memetic parsing.

Digital art history will struggle to be conducted through existing research, funding and hierarchical models perpetuated by university institutions that maintain siloed bastions of research specialisation and recruitment. It requires flexibility, agility, professional surety and institutional bravery. And yet the possibilities for new, interactive and evolving art histories are immense. In order to take advantage of new forms of spectatorship and historical staging, we must look to interdisciplinary models of collaboration and skillset development for guidance in navigating these new channels for visual investigation.

Notes

1. Sidney Nolan, ‘The ANZAC Story’, The Australian Women's Weekly (March 17, 1965): 3.

2. Paula Dredge et al., ‘Unmasking Sidney Nolan's Ned Kelly: X-ray Fluorescence Conservation Imaging, Art Historical Interpretation and Virtual Reality Visualisation’, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Art 17, no. 2 (2017): 147.

3. Tom Chandler et al., ‘A New Model of Angkor Wat: Simulated Reconstruction as a Methodology for Analysis and Public Engagement’, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Art 17, no. 2 (2017): 182.

4. Ibid.

5. Anthea Gunn, ‘What Could Have Bean: Using Digital Art History to Revisit Australia's First World War Official War Art’, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Art, vol.17, no.2 (2017): 175.

6. Chandler et al., ‘A New Model of Angkor Wat’, 182.

7. Ibid.

8. Marnie Feneley, ‘Reconstructing God: Proposing a New Date for the West Mebon Viṣṇu, Using Digital Reconstruction and Artefactual Analysis’, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Art 17, no. 2 (2017): 195.

9. Susanne Thurow, ‘Response to Performative Digital Methodologies: New Interdisciplinary Paradigms for Creative Practice and Analytical Documentation in the Arts’, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Art 17, no. 2 (2017): 238.

10. Chandler et al., ‘A New Model of Angkor Wat’, 185.

11. Thurow, ‘Response to Performative Digital Methodologies’, 238.