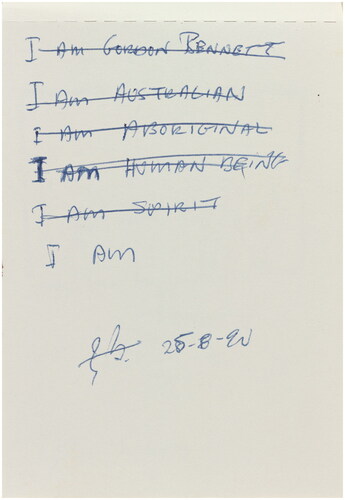

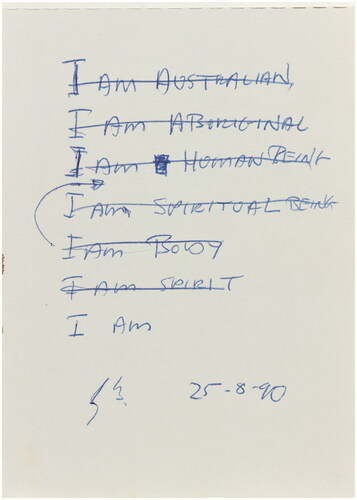

In the last room of the Queensland Art Gallery’s 2020 exhibition Unfinished Business—The Art of Gordon Bennett, just before the spectator exited the show, was a page from one of Bennett’s notebooks, blown up and applied to the wall.Footnote1 Unfinished Business was a survey exhibition of Bennett’s work, one of several that have so far taken place since his death, this time with an emphasis on works on paper. These were framed and mounted on walls throughout the exhibition, along with a selection of paintings from throughout Bennett’s career. But this particular page from the notebook was enlarged and applied directly to the wall of the final room, as though to serve as something of an artist’s signature in relation to what had come before—indeed, at the very bottom of the the wall were Bennett’s initials, GB, along with the date on which he originally made the entry, 25 August 1990 ().

What we have on that last wall of the gallery is testament to the ongoing importance of language in Bennett’s work. Words enter Bennett’s practice at least as early as 1987 with The Persistence of Language and continue virtually all the way to the end. Indeed, critics would later come up with the evocative term ‘word stack’ to describe a similar run of words in Bennett’s Notes to Basquiat series (1998–2002), which this notebook page is clearly a forerunner to.Footnote2 Earlier in the show, in fact, there was another page from Bennett’s notebook, very similar to the one in the last room, although it was actually framed and mounted on the wall. Its series of statements reads ‘I am Australian’, ‘I am Aboriginal’, ‘I am Human Being’, ‘I am Spiritual Being’, ‘I am Body’ and ‘I am Spirit’, followed by a final ‘I am’, Bennett’s initials and the date on which he made the entry, which is the same as the other page, 25 August 1990. In that version on the final wall, we have in slightly more abbreviated form ‘I am Gordon Bennett’, ‘I am Australian’, ‘I am Human Being’ and ‘I am Spirit’, again followed by a final ‘I am’, Bennett’s initials and the date. But although the two versions have the same date, we might say that the version on the wall comes later, insofar as we do not have that same crossed-out ‘a’ before ‘Human Being’, as though by now Bennett had made up his mind as to its proper formulation ().

As we read this series or sequence of categories, just to consider the earlier version mounted on the wall for a moment—Australian, Aboriginal, Human Being, Spiritual Being, Body and Spirit—we are tempted to see them as becoming increasingly abstract or even universal before that final ‘I am’, which is obviously the most specific, but which we feel we are being told is the most abstract and universal of all. This is indicated by the fact that, after originally writing ‘I am Body’ and ‘I am Spirit’, Bennett realises that Body is more specific and concrete than the immediately preceding Spiritual Being, and therefore uses an arrow to indicate a change of order.

In the subsequent version, as we can see, Bennett resolves this difficulty by no longer having Spiritual Being and Body at all. But then, if this is the obvious way of reading that sequence of categories, one of the perhaps surprising consequences of this is that Bennett appears to be suggesting that Aboriginal is a wider and more inclusive category than Australian, whereas conventionally Aboriginal would be understood to sit within the wider category of the Australian. And undoubtedly the other complexifying aspect of the sequence is that none of the categories are rendered as straight or unmarked. In both versions, the text has been crossed-out, struck through with a horizontal line, apart from a final ‘I am’ at the bottom, as though something of an assertion of identity that is not subject to and perhaps overcomes the doubt or failure of those previous categories. And yet, at least in that version on the final wall, it is as though any actual assertion of identity after this is again subject to doubt, as the initials ‘GB’ following it, just like that ‘I am Gordon Bennett’ at the top of the work, have also been crossed out.

Of course, those who know Bennett’s work will know that this ‘I am’ is something of an allusion to the great New Zealand artist Colin McCahon’s Victory over Death 2 (1970), one of the most celebrated and critically acclaimed works in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia. The most notable thing about Victory over Death 2, a huge painting measuring some six metres across by two metres high, is that it features an enormous ‘I AM’ to the centre-left of the canvas, based on words that Christ said on the cross as told in the Book of John, as well as in its broadly brushed black and white vertices alluding to the rugged terrain and diaphanous light of the South Island of New Zealand where McCahon was born (hence the Māori word for New Zealand, Aotearoa, ‘land of the long white cloud’). McCahon was a constant source of inspiration for Bennett, all the way from his time as an art student in the late 1980s, as seen in such works as The Coming of the Light (1987), based on McCahon’s 1959 Elias series, through to his similarly titled Notes to Basquiat (The Coming of the Light) (2001), which makes a comparison between McCahon and the American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat with regard to the respective uses of language in their work.

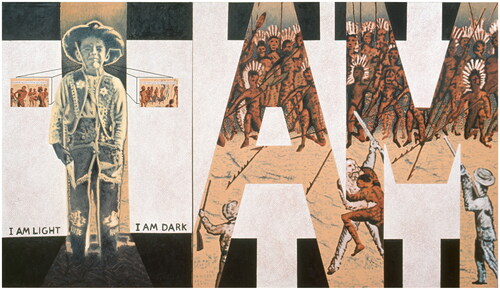

An even more direct reference to McCahon’s Victory over Death 2 is to be found in Bennett’s Self-Portrait (But I Always Wanted to Be One of the Good Guys) (1990), which directly reproduces the large ‘I AM’ of that work, as well as in its ‘I am Light I am Dark’ towards the bottom left referring amongst other things to McCahon’s largely back and white palette. And there was also in Unfinished Business the previously unknown I am (1991–1992) from around the same time as those notebook pages, which features a dedication to the Māori poet and artist Emare Karaka—Bennett’s almost exact contemporary—which reminds us in turn that the ‘I’ in McCahon’s ‘I AM’ is in part at least an allusion to the Māori Tau cross ().

Self-Portrait, we might say, is a painting about Bennett’s dividedness. He was raised as a young child to think that he was a white Australian only to discover at the age of eleven that he had Indigenous heritage. (Bennett’s father was an English immigrant who worked as an electrical linesman for a British construction company and his mother grew up on a mission in Cherbourg in south-east Queensland subject to the 1939 Aboriginal Preservation and Protection Act, whereby Aboriginal people were forced to lose their original culture and assimilate into white Australia. Together they felt it best, for entirely understandable reasons, not to reveal Bennett’s Indigenous heritage to him.) All of this is dramatised in that self-portrait by Bennett on the left side of the painting, which is based on a photo of him as a child, dressed in a cowboy suit with sheriff’s badge, ready to fight the Indians. On the right-hand side we have a slightly altered film still from Australian director Charles Chauvel’s Uncivilised (1936), a so-called ‘jungle story’ aimed at the US market, in which the Aborigines of Cape York are made up to appear like Native American Indians. Again, down towards the bottom left-hand side of the painting, we have the words ‘I am Light I am Dark’, which speak to how Bennett can be seen to identify with figures from both sides of the painting. And, finally, almost like dialogue boxes going into Bennett’s ears, we have an episode from Australia’s colonial past as represented in a high school history textbook, in which Indigenous men take up spears against European invaders—as opposed to Bennett playing a cowboy fighting Native American Indians—with the accompanying captions ‘The Warriors Chosen for the Shooting Party Made Ready’ and ‘Later that Evening the Scouting Party Came Back’, almost like his unconscious whispering to the young Bennett, telling him who he really was.

Several years after Self-Portrait, Bennett was to write his essay ‘The Manifest Toe’ (1996), in which he seeks to explain both where he comes from as a person and his practice as an artist. It is undoubtedly one of the most brilliant and sophisticated accounts of their artistic practice by any Australian artist, now reprinted several times, and one of the decisive documents for thinking about Indigenous art altogether. However, a close reading reveals a number of subtle if productive inconsistencies or even contradictions that both allow us to think his art and that his art allows us to think. As Bennett states in the opening autobiographical section, after leaving school at fifteen, he completed an apprenticeship in fitting and turning and then followed his father by working as a line serviceman for Telecom Australia. By his late twenties, however, he was growing dissatisfied with both his life and work and, recalling his early love of art at high school, undertook part-time study at the Brisbane Institute of Art in order to prepare a portfolio so that he might leave his job and enter art school. Bennett makes it clear that, having been accepted by the Queensland College of Art and enjoying his first-year Renaissance to Modernism course, the turning point came the following year when he undertook a course in postmodernism and read such thinkers as Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida. This, along with the following year’s course, Aboriginal Art and Culture, allowed him to begin to reflect more critically upon the category of Aboriginality.Footnote3 What Bennett came to realise is that there was no single ‘essential’ or ‘unchanging’ Aboriginality, but rather that it was at least in part a Western construction that was then projected upon Aboriginal people. As Bennett writes in ‘The Manifest Toe’: ‘I soon realised that everything I knew about Aborigines, everything I was finding out about my heritage in my Art College elective on Aboriginal Art and Culture, was filtered through a European perspective’.Footnote4 This is to say, on a more personal level, that even when Bennett learnt of his Indigenous heritage it did not confer some particular identity upon him, because he knew there was no single Aboriginality that encompassed all Indigenous people; instead, it changed according to how it was constructed and by whom. As he writes of the prevailing form of ‘Aboriginality’ found in Australian art at the time: ‘I wanted to explore my “Aboriginality”, if only to heal myself, but felt that for me to paint fish and kangaroos and the like would have been like painting empty signs of this thing called “Aboriginality”’.Footnote5

Needless to say, the argument for the essential arbitrariness of both personal identity and wider racial and sexual categories is familiar to us all as part of a generalised (and frequently vulgarised) postmodernism, which speaks to the way that we are never able to grasp ourselves directly but only through the mediation of language, inherited social categories and the internalised gaze of others. As a result, taken to its extreme, there would appear to be nothing in particular that would define something like Aboriginality or what being Aboriginal is, so much so that Bennett can even suggest in ‘The Manifest Toe’ that ‘While some people may argue this [being positioned as an urban Aboriginal artist] has been a quick route to success, and that my work is authorised by my “Aboriginality”, I maintain that I don’t have to be an Aborigine to do what I do’.Footnote6

And yet despite this Bennett can also point to the persistence or even necessity of a certain self-identity. The first moment this occurs is when, after initially advocating a ‘strategic’ use of the term ‘Aborigine’, he goes on to argue for not only the appeal but even desirability of a certain ‘essentialism’: ‘While I would contend that a strategic logocentre may be one of the forms that Aboriginality can take, I would also point to this essential thing as being the object of what Franz Fanon called “passionate research”’.Footnote7 Equally, after suggesting that all attempts to grasp who he is as an Aboriginal man are open to doubt, insofar as they can all be shown to be stereotypes coming from elsewhere imposed upon him, he insists that this cannot be said outside a certain underlying ‘I’: ‘An “infinity of traces without an inventory”, these few words best describe to me an identity… an everflowing process that is alive with possibility, and which confuses and flows around the conceit “I am”’.Footnote8 And altogether, in perhaps his strongest assertion of the necessity of breaking with or at least standing outside of the processes that would shape him, insofar as they are to be thought: ‘Consequently I am interested in psychoanalysis; particularly in the kind of radical analysis that interprets the so-called norms of society as repressive illusions and which regards analysis as a preparation for the analysand to get outside of them once and for all’.Footnote9

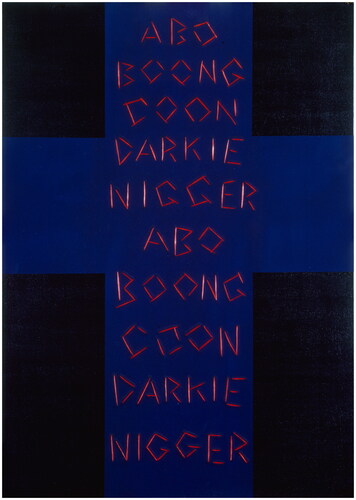

How are we to reconcile the fact that Bennett at once argues for the historicisation and relativisation of such categories as the Aboriginal and also for an essential or at least strategic Aboriginality from where this can be thought? How to put together the endless splitting and division of the self and the fact that from the ‘many diverse, culturally relative, dismembered and repressed fragments’Footnote10 of an ever-flowing process a certain ‘I’ emerges? Indeed, how might we acknowledge that, far from having to be reconciled, we cannot have one without the other? That we cannot have these categories without the breaking up of these categories and cannot have the I without the emptying out of the I. And how, finally, might all of this relate to those two pages from Bennett’s notebook that we began by looking at? We might begin here with the revealingly titled installation Self Portrait (Schism) (1992), which includes the two canvases History Painting (Burn and Scatter) and History Painting (Excuse My Language) (). In History Painting (Excuse My Language), we have what appears to be a series of racist insults inscribed alphabetically down the surface of the canvas: ‘Abo’, ‘Boong’, ‘Coon’, ‘Darkie’ etc. And the same incision or inscription into a dark surface is also seen in Bennett’s Bloodlines (1993), in which a series of thin red marks, based apparently on Bennett’s left- and right-hand palm lines, run down an all-black surface like the flow of a river or blood. Or even his Self Portrait (Suit) (1995), in which a textured black canvas suit hangs on a wall revealing an inner red lining. And finally, we would suggest, there are all the many red lines that move through Bennett’s later work, for example, Notes to Basquiat: (ab)original (1998), in which an otherwise black-seeming body is outlined with what looks like a red silhouette.

Of course, the most obvious reading of Excuse My Language is that something like a knife or whip has carved the words into a dark-skinned body, opening up the skin to reveal the flesh beneath. It is literally to inscribe this racist identity into the subject or object it names, ensuring that this is all they are. (Bennett has, in fact, made a number of works involving a whip and shouted racist epithets in exactly this manner, for example, Performance with Object for the Expiation of Guilt (Apple Premiere Mix) (1993), and this recalls the whip hanging to the side of the incised surface of Self Portrait: Interior/Exterior (1993) and even the red whip notionally lashing the Indigenous man gazing into the water in Poet and Muse (1991).) But with the red flesh exposed beneath the abusive words of Excuse My Language, Bennett is perhaps reminding us of our common humanity, of the colour we all share beneath our variously coloured skins. And, following that series of descending but ascending words we have in those two pages from Bennett’s notebook, we might see this red flesh into which those words ‘Abo’, ‘Boong’, ‘Coon’ etc., are inscribed as something of a crossing out or crossing over of those categories, a universality that is aways more than those racist labels. In effect, that string of words is not so much a series of indifferent racist epithets as the successive but failed attempts to cover over what cannot be covered over, what appears more than any of its particular categories. Indeed, it might be something like this excess that precisely incites this racist abuse, the sense that the other is whole or entire as opposed to the abuser who feels that they lack something.

And yet, at the same time, if we want to propose this red flesh as some kind of common humanity that overruns all of its categories and can never be accounted for by any of them, it must also be admitted that it is not this red flesh that comes first and these names fall short of, but that this red can only be seen through and in a way only exists because of the gaps or shortcomings in the black. In other words—and although this might seem counter-intuitive, it is what we see in those notebook pages—these thin strips of red are not some split in the black that these names fall short of but are instead what brings those names together, ensuring that there is nothing outside of them. And we see something like this in that series of works by Bennett in which an all-black surface runs over an underlying series of scars and cicatrices that can be seen underneath, such as Untitled (Triptych) (1991) and indeed Self Portrait (Suit).

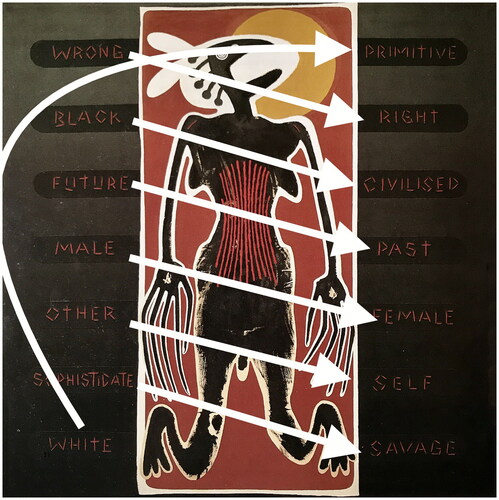

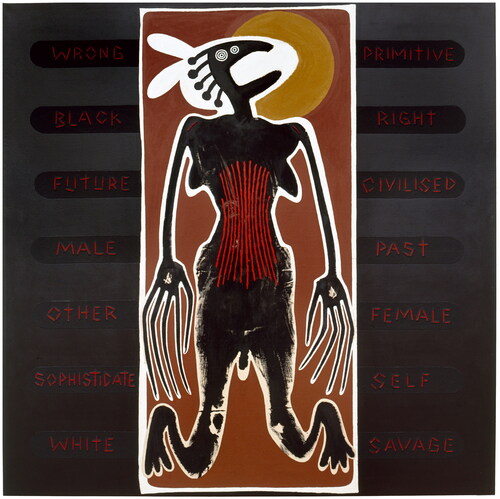

We observe much the same thing in another Bennett work, Altered Body Print (Shadow Figure Howling at the Moon) (1994) (). What we have there is a series of descriptions, this time not directly racist but apparently typological, running down either side of an Indigenous figure, produced by Bennett pressing his own painted body against the canvas, with a strange kangaroo-like head and long-fingered feet and claws and striped ceremonial markings running down its torso. Down the left-hand side we have a list of words inscribed in brushed-over matte black on black, ‘Wrong’, ‘Black’, ‘Future’, ‘Male’, ‘Other’, ‘Sophisticated’ and ‘White’, while down the right-hand side we have ‘Primitive’, ‘Right’, ‘Civilised’, ‘Past’, ‘Female’, ‘Self’ and ‘Savage’. Of course, by simply reading the words across they can appear, like those insults in Excuse My Language, as merely the successive failed attempts to describe the figure, marked each time with a certain equivocation and sense of its shortcomings. Thus, if ‘White’ does not fit, we are tempted to try ‘Savage’; if ‘Other’ does not fit we are tempted to try ‘Female’; and so on. Again, it is as if there is some excess of the figure that these descriptions are seeking and failing to capture, as though there is something left out from any particular category we might apply to it. (And, indeed, in terms of this ‘excess’, the figure does appear to have both a penis and breasts.)

But then, with a little more attention, we realise that we are dealing not with a variety of unrelated descriptions but a series of logical oppositions transversally matching each other. Thus ‘Wrong’ at the top left is paired with ‘Right’ one down to the right, ‘Black’ one down to the left is paired with ‘Civilised’ two down to the right, ‘Future’ two down to the left is paired with ‘Past’ three down to the right, all the way down to ‘White’ at the bottom left, which is paired with the previously unmatched ‘Primitive’ up on the top right. And here the insistent presence of the body between the rows disappears and it becomes part of an invisible cycle running diagonally left to right with a final loop connecting bottom left to top right, as though something of a missing cause always trying to catch up with itself. And, along with this, we do not have the same sense any more that there is something beyond the realm of words that they are always falling short of, but rather that they now cover all alternatives (Future/Past, Male/Female, Other/Self, Sophisticated/ Savage). Here we might say that, as opposed to any shortcomings of the categories in relation to some pre-existing object, it is now the subject that disappears to allow the all-inclusive self-reference of a semiotic field. (And by contrast to the ‘excess’ androgyny of the figure in that first reading, what we have in this second reading is a figure made up of the same red lines as the words. And it might even be those same lines that move these words around the canvas connecting them ().)

To return to those notebook pages we began with one last time, it is something like this that we see there, too. We have previously remarked that, after each of those proposed qualities falls short and has to be crossed out, that final ‘I am’ can appear like a triumphant assertion of self-identity. Bennett would be more than any of them, that empty unmarked space from which to think the way they arbitrarily construct his identity. But then this simple doing away with all doubt, as in Descartes’ cogito, is not at all Bennett’s experience, for all of Bennett’s proposing of a ‘strategic logosphere’ or even ‘passionate essentialism’. Indeed, as we have seen in that version attached to the wall of the gallery, Bennett crosses out his name and initials, as though any consequent expression of his identity is not to be trusted. We might then turn to that other way of understanding those notebook pages, opened up also by Altered Body Print, which is to say that, rather than some intact or integral ‘I’ standing outside of its various categories and evidencing their shortcomings, this ‘I’ in effect disappears to ensure that these categories are universal and cover all alternatives. That is to say, in the same way as we have, for example, ‘Wrong/Right’, ‘Black/Civilised’ and ‘Future/Past’ in Altered Body Print, we have an ‘Australia’ broken into two halves in the notebook pages. And although ‘Australia’ is in the same way always opposed to itself there, we can also only argue against one ‘Australia’ in the name of another, let us say better or different, ‘Australia’. And the same thing goes for the category of ‘Aboriginal’, for as Bennett says of his course in Aboriginal Art and Culture at the Queensland College of Art, if it allowed him to question some ‘natural’ or ‘primitive’ notion of Aboriginality, it was only in the name of a ‘historical’ and ‘scientific’ one that was still European. As he writes in ‘The Manifest Toe’, recalling the oppositions of Altered Body Print (and, of course, the question we will come to is what is left out of this opposition that allows it to come about):

I soon realised that everything I knew about Aboriginality, everything that I was finding out about my heritage in my Art College elective on Aboriginal Art and Culture, was filtered through a European perspective, through the canon of Anthropology and Ethnography: those men of ‘science’ who peered at Aboriginal people and made judgements based on an assumed cultural superiority predicated on such binaries as civilised and savage, self and other.Footnote11

However, Bennett’s real point is that these two approaches cannot be separated. The exclusion of the I can only be expressed by an Aboriginality that is possible only because of the exclusion of a certain I. Or to put it otherwise, Aboriginality is the name for the split in the I, just as I is the split within Aboriginality. And if this sounds abstract, we might take it back to the actual life experience of Bennett himself and say that ‘Aboriginality’ is the name for that dissatisfaction or inadequacy Bennett felt in himself at a certain point (it is what allowed him to express that sense of not being entirely himself), just as ‘Bennett’ is the name for that split or division in Aboriginality (not merely the split Bennett himself experienced between ‘primitive’ and ‘scientific’ Aboriginality, but the fact that Aboriginality would always be split in this way). But perhaps the crucial thing here is that if this means there is no ‘essential’ I or Aboriginality, that it is always split or divided from itself, this does not imply any kind of postmodern ‘relativism’ insofar as this I and Aboriginality are not simply lost or deferred but are their own split and division, and in this split and division are universal. It is precisely what prevents Bennett from having an identity that is his identity. It is what means we can never definitively say what Aboriginality is that is Aboriginality. So, the real equation at stake in those notebook pages is not so much I = ABORIGINAL or ABORIGINAL = I as I = ABORIGINAL. It is not only that Bennett’s identity lies in his loss of Aboriginality, or that Aboriginality is his loss of identity, but, in a kind of double negative that produces a positive, Bennett’s loss of identity is his loss of Aboriginality.Footnote12

But again, if all of this seems too abstract, let us consider another Bennett work that we would say expresses precisely this: the long-running Coloured People series (2000–2008) produced by Bennett’s artistic pseudonym, John Citizen (). To begin with the name, the generic or even anonymous John Citizen. Bennett began using the term in the Home Décor (Preston + De Stijl = Citizen) series in 1995 and carried it all the way through to his late Abstraction (Citizen) series of 2012. He once wrote of this adopted identity to the Canadian critic Ihor Holubizky: ‘John’s birth, or rite of passage, [involved] the splitting of Gordon Bennett away from his Aboriginal artist ‘naming’… I know that John Citizen gives Gordon Bennett a chance at other perspectives, like a third space for dialogue between the dualities of self and other’.Footnote13 And undoubtedly the inspiration behind Bennett both giving up his birth name (which is already a version of Cockney slang) and adopting another seemingly without qualities was the American civil rights leader Malcolm X, who after converting to Islam and beginning the project of black voter registration did so not in the name of or even to recover some supposedly lost Afro-American identity, but to propose a new ‘black’ identity to come, which would not even be particular to Afro-American people. (In part, his registration campaign was as much for disenfranchised poor white Southerners, who were even likely to be antagonistic to black Americans.Footnote14) That ‘X’ in his name—which, as in Bennett’s notebook pages, is first of all a crossing out of his own identity—is exactly the attempt to make him more universal, to not separate him from others, and perhaps even to suggest that all names are a certain loss of identity, a falling short of who we are, which can only be captured by another name. (In this sense, all names are in a sense their own opposites, a certain unnaming with a line running through them.)

Figure 1. Gordon Bennett, Notebook sketch, 25 August 1990. Ink on paper. 27 × 19.5 cm. Collection: Estate of Gordon Bennett.

Figure 2. Gordon Bennett, Notebook sketch, 25 August 1990. Ink on paper. 27 × 19.5 cm. Collection: Estate of Gordon Bennett.

Figure 3. Gordon Bennett, Self Portrait (But I Always Wanted to Be One of the Good Guys) 1990. Oil on canvas. 150 × 260 cm. Private collection, Brisbane.

Figure 4. Gordon Bennett, History Painting (Excuse My Language) 1992. Acrylic and flashe on canvas. 92 × 65 cm. Collection: Holmes à Court.

Figure 5. Gordon Bennett, Altered Body Print (Shadow Figure Howling at the Moon) 1994. Acrylic and flashe on canvas. 182 × 182 cm. Private collection.

Figure 7. Gordon Bennett/John Citizen, Coloured People #20 2007. Synthetic polymer paint on canvas. 101 × 101 cm. Sutton Gallery, Melbourne

Now let’s turn to what Bennett might mean by Coloured People and how it is the equivalent of its author, John Citizen. As we have seen, if there is a universal at stake in Bennett’s work, be it either Bennett’s identity or the notion of Aboriginality, it is not given directly but only as a kind of split with itself, so that if it is never given whole and is always able to be challenged, it can be done so only in its name. And it is at this point that we might note that there are philosophically speaking two different universals, or at least two different ways of thinking about the universal. The first is one in which the universal is like an empty box that simply accumulates examples but is not meant to be confused for any of them, insofar as they always fall short of it, or it remarks upon them from somewhere outside of them. The other is one in which we only have examples, but our very ability to remark upon them splits them, implies some space outside of them, which will be revealed in turn to be merely another example. In the first, it is the genus that classifies its species. In the second, this genus is revealed to be merely another species. In the first, we have the one and the many. In the second, we start with two, which produces the retrospective effect of one. The first—and we will come back to the distinction between the two later—is the philosopher Kant’s negative judgement and the second is the philosopher Hegel’s infinite judgement.Footnote15 But we might also oppose them—and, of course, this should remind us of what we have previously argued of Bennett’s notion of ‘Aboriginality’—as white and black, for if the logic of whiteness, at least until recently, was that of an empty universal that was ideal and ahistorical, a place from where all differences were marked from a distance, ‘black’ in that way we have been trying to describe can be seen only in its particulars, not in the inadequacy of all others (non-black) to be black (as white is the inability of the non-white to be white), but of black itself to be black. ‘Blackness’ not only does not exist outside of its examples, but moreover is to be seen only through their failure, the failure as it were of black to be black. As David Marriott writes of the French West Indian philosopher and psychoanalyst Franz Fanon, who was important to Bennett: ‘Le non-moi c’est moi… Fanon presents blackness from the position of contrariety (some men are not white), but as a contrary that has no (white) universal’.Footnote16

As can be seen from Excuse My Language, Altered Body Print and those notebook pages, Bennett was obsessed with the self-splitting of black identity throughout his career. We might go back to his foundational encounter with McCahon’s Victory over Death, in which, famously, before Christ’s assertion of triumph on the cross, ‘I AM’, there is an ‘AM’ painted to the left of that central illuminated ‘I’, thus posing a question or moment of doubt to which Christ’s assertion must be seen to be responding: ‘AM I?’, ‘I AM!’ And brilliantly McCahon paints that first ‘AM’ in reflective paint against an otherwise matte oil paint so that it stands out against it. In a sense, then, Christ’s ‘I’ arises out of the splitting of black into both the visible figure and the invisible background that allows it to be seen. And Bennett proposes something similar of another ‘foundational’ painting, not just of his own artistic life but of the Western tradition altogether: Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square (1915), which he reimagines not as a black square on a white background, but as literally black on black, indeed with the word ‘black’ in reflective paint on matte black paint, very much in the manner of McCahon, in a notebook sketch of 21 October 1993. In fact, in this rethinking of the ‘transcendentality’ of Malevich’s painting—for Black Square is not only understood by Malevich as a depiction of the ‘face of God’ but by art historians generally as not merely an ‘abstract’ painting but proposing the transcendental conditions all painting—as the split of black with black, Bennett can be seen to be extraordinarily prophetic. In 2015 it was discovered by the conservators of the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow in which the painting is housed that underneath that black square Malevich had originally written the words ‘Battle of Negroes in a Cellar at Night’.Footnote17 Here again the transcendental would be not simply above the phenomenal world it conditions but the very split or battle of the phenomenal with itself, the putting together of the highest and the lowest.Footnote18 And we see this joining of the worldly and the unworldly in such Bennett versions of Black Square as Monochrome (with Red) (1995), in which he mixes black and red paint; Untitled (Nuance) (1992), in which he peels off a now transparent plastic mask that previously took on the colour of his skin; and even the etching Ask a Policeman (1993), in which an Aboriginal man who has hanged himself dangles over a black void.

Bennett first began to think about the question of a universal ‘blackness’ when he encountered the work of Haitian-Puerto Rican-American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat while at art school in the 1980s. He was later to write of what he called an ‘internationalist’ blackness in a letter he addressed to Basquiat in 1998, by which time the artist was dead: ‘My work [is an attempt] to communicate a basic underlying humanity to the perception of ‘blackness’ in its philosophical and historical production’.Footnote19 And soon after Bennett started making his long-running Notes to Basquiat series, exactly as an attempt to continue the communication between them. The most typical format in the series—and we can see the connection to what we have seen before—is a series of vertically stacked synonyms running down the canvas like a thesaurus, along with the imitation—undoubtedly a little too stiff and self-conscious—of Basquiat’s neo-expressionist graffiti-esque humanoid forms. But there is also a particular set of the Notes to Basquiat series that, instead of these synonyms, features a list of body parts alongside a more skeletal figure. For example, in Notes to Basquiat: Autonomic Nervous System (1998), we have ‘Trachea’, ‘Lungs’, ‘Heart’, ‘Liver’, all the way down to ‘Rectum’ running down the left side of the canvas, along with ‘Universal’, ‘Malevich’, ‘Basquiat’ and ‘Citizen’ running down the right.

Of course, it is tempting to see this progression or perhaps regression from ‘Trachea’ (breath, spirit) to ‘Rectum’ (waste, excrement) as not only literally but metaphorically from high to low. But attuned both by those Bennett works we have previously looked at and the fact that the thesaurus often moves from specific and particular synonyms through to broader and more inclusive equivalents, what we want to suggest is that in this move from ‘Trachea’ to ‘Rectum’ we shift from lower to higher, the less universal to the more universal. For, in that way we have been suggesting, it is not the immaterial, spiritual and physically unmoored trachea and its breath or speech that is truly universal—after all, there are many human languages, not all of them comprehensible to each other—but the lowest, most material and particular rectum and its winds and excretions, which we all share and all smell the same. It is the universal that is excluded, rejected and divided from itself. Similarly, in that list to the right of the work with ‘Universal’ at the top and running down through ‘Malevich’, ‘Basquiat’, ‘Bennett’ and ‘Citizen’, what we suggest is that it traces a passage not from highest to lowest but from lowest (white Russian) to highest (identity-less black), or even a circular respiration as in Altered Body Print, in which the universality implied by Citizen can be expressed only by the particularity of Malevich and the split in Malevich implies the universality of Citizen.

Black Lives Matter protests erupted across America in May 2020 in response to a video showing police officers in Minneapolis holding black man George Floyd down on the ground with a knee on his neck until he was asphyxiated. ‘I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe’ are Floyd’s immortal last words, as seen in footage recorded by Darnella Frazer on her cell phone, which was viewed around the world. This led to calls for the police officers involved to be tried for murder, along with an acknowledgement that black Americans are disproportionately subject to more arrests, lengthier sentences and police and state violence than any other group of Americans. These protests soon spread to Australia, where over a series of weeks in June 2020 both Indigenous and non-Indigenous protestors took to the streets and demanded an end to Aboriginal deaths in custody and a whole range of wider social discriminations suffered by Indigenous Australians. But the Black Lives Matter protests soon led to a backlash by conservative commentators and, indeed, protestors, who argued that any kind of specific ‘black’ justice was racist; instead, the proper cause should be voiced as ‘All Lives Matter’. To take just one instance of this kind of argument, we might quote none less than Rudy Giuliani, who confided to Fox News that ‘Black Lives Matter is inherently racist because, number one, it divides us. All Lives Matter: white lives, black lives, all lives’.Footnote20 This view has been challenged by many, from Black Lives protestors themselves and their supporters to philosophers and even jurists, who might be expected to be more cautious or at least even-handed in not arguing for any special treatment of a particular segment of the population (but who have perhaps begun to think, along with Hegel, that the first crime is the law itself). To my mind, the best response is by philosopher and political activist Cornell West, who uncompromisingly expresses where exactly the universality of Black Lives Matter would lie:

The emergence [of BLM] exposes the spiritual rot and moral cowardice of too much of Black leadership [under Barack Obama]… in order to show their love of those shot down by an unaccountable police force under a Black President, Black attorney general and Black homeland security. What an indictment of neo-liberal Black power in the face of massive Black suffering, highlighted by Black Lives Matter activists.Footnote21

At this point we return to Bennett’s Coloured People series, which shows us exactly this: that we are all coloured and no one is only one colour.Footnote22 (And this particularity, the fact that none of us is coloured like anyone else, is the universality of their maker, John Citizen.) This is also the power of such race-based critiques as Black Lives Matters and ‘white studies’: that white is merely another colour and always found mixed with others. And Bennett once made a work about exactly this, Im Wald (Divided Unity) (1995), which features both black and white figures and the line ‘each man is an interior sea’. The year before Bennett had painted the large, much discussed and similarly titled Painting for a New Republic (The Inland Sea) (1994), which features on the left-hand side a Union Jack, colonists rowing a boat and a pile of Aboriginal bones, on the right-hand side a Western Desert painting and an Indigenous baby being held over a pond, and at the upper centre an Indigenous man looking into a mirror who turns out to be Bennet, along with a pared-down landscape and a book by Kant.Footnote23 This reflection in the mirror is reminiscent of that famous image of Brunelleschi staring into a mirror at the origin of Western perspective. The paradox of Brunelleschi’s set-up is that the spectator comes to the painting only by taking up the point of view of a notional spectator who has come before them, but it is retrospectively revealed that this spectator is only them. They look at the painting because they feel that the painting is looking at them, but thanks to Brunelleschi’s mirror it is the spectator who is already looking at themselves. The painting is in a sense this very gap between the spectator and themselves, standing in for that self they cannot see. And this is perhaps why Bennett then did another version of Painting for a New Republic called Mirror (Interior/Exterior) Volkgeist (1995), in which he now shows his face on what was the mirror of that original mirror, except that this time it is Hegel and not Kant who is the author of that book to the side of him. This may be because, as we have been hinting throughout—and, remember, the painting is a kind of reflection upon Painting for a New Republic’s reflection—it is Hegel who makes the point that the transcendental of Kant is not so much something outside as a split in what is inside, or to go back to the title of the work, the split between the interior and exterior.

Bennett is his own distance from himself. This is what Bennett is trying to figure in his work all the way from Altered Body Print through those notebook pages and on to Notes to Basquiat and beyond. ‘Aboriginality’ might be the name for what separates Bennett from himself, except that, as we have seen, Bennett is also the name for what separates Aboriginality from itself. And this is true of everybody: it is not any single identity or category we all have in common but only this division, this line or crossing out within ourselves. It is certainly true of me. At one end, the top, I am a singular king, an I, who stands above all, and at the other, the bottom but really the top, I am merely an anonymous butler or servant. But really who I am is that ‘X’ or crossing out that runs between them, at once connecting them and making them possible. And, of course, Bennett has already depicted this. His notebook drawing Untitled (Nachos), dated 13 January 1998, puts a crown atop a childish image of a Tyrannosaurus Rex and beneath that a pencilled clown, and I am the very space between them. Like Gordon Bennett, I am not Gordon Bennett, but I am also not Rex Butler, and we at least have that in common.

Acknowledgments

This paper was originally delivered as the Daphne Mayo Annual Public Lecture at the University of Queensland on 25 August 2022, which is the same day thirty-two years later on which Bennett originally made those notebook drawings. I would like to thank my colleagues in Art History at the University of Queensland, especially Andrea Bubenik, for inviting me. I would also like to thank Leanne Bennett and Ian McLean for their assistance in the writing of this essay. I would finally like to thank the two anonymous reviewers of this essay for the Journal, as well as its editor, Verónica Tello.

Notes

1 Unfinished Business—The Art of Gordon Bennett, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 7 November 2020–21 March 2021. For an extensive review of the exhibition, see Pat Hoffie, ‘Unfinished Business: The Art of Gordon Bennett’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art 21, no. 2 (2021): 299–303.

2 See Simon Wright, ‘The Gordon Bennett Studio’, in Unfinished Business—The Art of Gordon Bennett (Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery, 2020), 131.

3 Undoubtedly also influential on Bennett at this time was the work of Marcia Langton, most notably Well, I Heard It on the Radio and Saw It on the Television (North Sydney: Australian Film Commission, 1993), whose critique of both a ‘white’ and a ‘black’ essentialising of Aboriginal culture would be more fully developed in such later essays as ‘Anthropology, Politics and the Changing World of Aboriginal Australians’, Anthropology Forum 21, no. 1 (2011): 1–22. Another important example for Bennett at this time was the Queensland-based Indigenous academic Aileen Moreton-Robertson, who would later write Talkin’ Up to the White Woman: Indigenous Women and Feminism (Brisbane: University of Queensland Press, 2000), which is a critique of many ‘white’ forms of identification with Aboriginal people.

4 Gordon Bennett, ‘The Manifest Toe’, in Ian McLean and Gordon Bennett, The Art of Gordon Bennett (Roseville East: Craftsman House, 1996), 31.

5 Ibid., 27.

6 Ibid., 58.

7 Ibid., 30.

8 Ibid., 12.

9 Ibid., 9.

10 Ibid., 12.

11 Ibid., 31. Ian McLean says much the same thing: ‘This is why post-modernism suited the purposes of Bennett’s art: its deconstructive methodology provided ways to represent what had been foreclosed by the history of Europeans bringing Enlightenment to the antipodes. All of his work is founded on the presumption that the language of the Enlightenment introduced by colonialism was, for Aborigines, a prison-house they could not escape, but only appropriate’, The Art of Gordon Bennett, 73.

12 We might just quote here Slavoj Žižek on this double negative that produces ‘identity’: ‘Crucial here is the final reversal: the disparity between subject and substance is simultaneously the disparity of the substance with itself—or, to put it in Lacan’s terms, disparity means that the lack of the subject is simultaneously the lack in the Other: subjectivity emerges when substance cannot achieve full identity with itself, when substance is in itself ‘barred’, traversed by an immanent impossibility or antagonism’. Slavoj Žižek, Sex and the Failed Absolute (London: Bloomsbury, 2020), 24. Equally, with regard to that earlier equation I = ABORIGINAL, we might read Denise Ferreira da Silva’s discussion of the European construction of a ‘subject without properties’ (Descartes, Kant, Hegel) and the necessary exclusion of ‘blackness’ to allow this. Denise Ferreira da Silva, ‘1 (life) ÷ 0 (blackness) = ∞ − ∞ or ∞/∞: On Matter Beyond the Equation of Value’, e-flux 79 (February 2017), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/79/94686/1-life-0-blackness-or-on-matter-beyond-the-equation-of-value/.

13 Gordon Bennett, ‘Letter to Ihor Holubizky, 2006’, in Gordon Bennett: Selected Writings, ed. Angela Goddard and Tim Riley Walsh (Sydney: Power Publications, 2020), 108, 109.

14 On this point, see, for example, Malcolm X’s famous speech ‘The Ballot or the Bullet’, first delivered at a Methodist Church in Cleveland, Ohio, on 3 April 1964. Malcolm X, ‘The Ballot or the Bullet’, EdChange, http://www.edchange.org/multicultural/speeches/malcolm_x_ballot.html (accessed 12 April 2023).

15 For an essay on Hegelian ‘infinite judgement’, see Anna Longo, ‘Infinite Judgements and Transcendental Logic’, Cosmos and History: The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy 20, no. 2 (2020): 391–415.

16 David S. Marriott, Lacan Noir: Lacan and Afro-Pessimism (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021), 93, 30.

17 Irina Vakar, ‘New Information Concerning The Black Square’, in Celebrating Suprematism: New Approaches to the Art of Kazimir Malevich, ed. Christina Lodder (Leiden: Brill, 2019), 23. Vakar attributes this phrase to the French poet Alphonse Allais, although in fact it was the little-known French playwright Paul Bilhaud who first coined the phrase. For more on this, see Aleksandra Shatskikk, ‘Inscribed Vandalism: The Black Square at One Hundred’, e-flux 85 (October 2017), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/85/155475/inscribed-vandalism-the-black-square-at-one-hundred/ (accessed 24 May 2023).

18 On Black Square as the face of God, see Kazimir Malevich, Letter to Pavel Ettinger, 3 April 1920, cited in Vakar, ‘New Information Concerning The Black Square’, 13. For an essay on Bennett’s use of black in general, see Abigail Bernal, ‘The Colour Black and Other Histories: Gordon Bennett and Jackson Pollock’, in Gordon Bennett—Unfinished Business, 67–82.

19 Gordon Bennett, ‘Letter to Jean-Michel Basquiat’, in Gordon Bennett: Selected Writings, ed. Angela Goddard and Tim Riley Walsh (Sydney: Power Publications, 2020), 102.

20 Naomi Lim, ‘Rudy Giuliani: Black Lives Matter “Inherently Racist”’, CNN Politics, 11 July 2016, https://edition.cnn.com/2016/07/11/politics/rudy-giuliani-black-lives-matter-inherently-racist/index.html.

21 George Souvlis, ‘Cornell West: Black America’s Neo-Liberal Sleepwalking is Coming to an End’, openDemocracy, 13 June 2016, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/cornel-west-black-america-s-neo-liberal-sleepwalking-is-coming-to-end/.

22 It is perhaps worth noting that one of the inspirations for Coloured People was African-American artist Adrian Piper, whose early performance series Catalysis (1970–1973) concerned her ability to ‘pass’ as white, and who in 2000 even made a series of works entitled Colour Wheel.

23 For a discussion of Painting for a New Republic in somewhat similar terms, see Brett Nicholls, ‘Disrupting the Kantian Sublime: Gordon Bennett’s Painting for a New Republic (The Inland Sea) and the Rule of Reason’, Culture, Law and Colonialism 1, no. 1 (2000): 129–48.