This article was written on the unceded lands of the Kaurna, Awabakal, Worimi and Kulin nations upon which the authors live and work.

This article seeks to contribute to the burgeoning body of writing on queer curating in a visual arts context. We reflect on five recent local exhibition projects to identify strategies that have guided its curators in developing queer methods. The three of us—Frances, Peter and Mel—have come together in conversation to develop a research method borne out of one of the five curatorial projects we discuss below, VERS: On Pleasures, Embodiment, Kinships, Fugitivity and Re/Organising (2022), led by Frances Barrett with a curatorium including Melissa Ratliff.Footnote1

This event was premised on a rolling conversation held over four hours, interspersed with live performances. After VERS, we wanted to keep the interplay of this discussion alive and to lean into the ‘unpredictability of moving in relation to another’, to use Lauren Berlant and Lee Edelman’s description of conversation.Footnote2 Choosing conversation as a critical form of knowledge production (and here we acknowledge its large role within curatorial discourse and exhibition programming) follows recent precedents, including Frances Barrett’s PhD thesis of 2021 Meatus: A Curatorial Passage, Amelia Jones and Erin Silver’s anthology Imagining queer feminist art histories (2015) and June Miskell and Bhenji Ra’s 2022 article “The ‘Women’s Show’ after House of Sle: A Dialogue Between Bhenji Ra and June Miskell’,” published in this journal. In the latter, the authors note that they adopted the discursive format because ‘collaboration, dialogue, and exchange are important methods of generating and sharing knowledge, despite being underrepresented in peer-reviewed scholarly publications.’Footnote3 As discussed in Barrett’s PhD thesis, conversation, process, and collaboration are interruptive forces to established academic writing and hold embodied and relational dynamics that support the development of queer research methodologies. In addition, we consider dialogue to shape a criticality and hold multiplicity through the authors’ contestation and questioning of each other.

The projects we focus on in this article span roughly one year and three states in the south-east of the country now known as Australia: Language Is a River (Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne, 2021–2022), QUEER: Stories from the NGV Collection (National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2022), Meatus (Australian Centre of Contemporary Art, Melbourne, 2022), VERS: On Pleasures, Embodiment, Kinships, Fugitivity and Re/Organising (Monash University Museum of Art, Samstag Museum of Art, and Adelaide Contemporary Experimental, Adelaide, 2022), and Screwball (Verge Gallery, Sydney, 2022). This article brings these exhibitions into conversation, ‘moving in relation’ with each other to draw out similarities and differences between queer curatorial projects.

Since 2017, there has been a rise in queer exhibition-making, evinced through large-scale exhibitions such as Queer British Art (1861–1967), curated by Clare Barlow with Amy Concannon at Tate Britain, London, and Spectrosynthesis: Asian LGBTQ Issues and Art Now, curated by Sean Hu at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei, both taking place in 2017. Queer curating has emerged as the focus of multiple recent programs and publications, including Routledge’s 2020 publication Queering the Museum by Nikki Sullivan and Craig Middleton; the 2017 symposiums Queer Exhibitions/Queer Curating: A Cross-Cultural Symposium at Museum Folkwang, Essen, and Queer Curating, Queer Art, Queer Archives at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS); and the 2017 ‘Queer Curating’ issue of OnCurating edited by Jonathan Katz, Isabel Hufschmidt, and Änne Söll. Within these examples, however, voices from outside of the European and North American context are rare, if not entirely absent. The event at UTS made clear Australia’s focus on European and North American perspectives, with its four international keynote speakers based in London, Poznań, New York, and Florida respectively.Footnote4 In the Queer Exhibitions/Queer Curating final panel discussion, an audience member stated that what threatened the development of a discourse around queer curating was a canonisation of North American–based exhibition histories. The panellists acknowledged that reaching out to colleagues based in other regions was necessary in building a complex discourse for this emerging field.Footnote5

Art historian and performance studies scholar Amelia Jones, in her 2020 publication In Between Subjects: A Critical Genealogy of Queer Performance, speaks to the narrowness of queer discourse (and performance discourse) as ‘US-based, most often normatively white, cosmopolitan and urban, often male, and clearly linked to late capitalist and postcolonial formations in European-dominant cultures.’Footnote6 What Jones’s research prompts us to consider in this article is that the goal is not to transplant queer uncritically to our context nor deny our complicity in these dynamics.Footnote7 In our conversation, we have identified several overlapping themes and artistic-curatorial strategies that include collectivism, citation, embodied experience, affect, language, representation, (in)visibility/(il)legibility, and forms of slipperiness. We consider that these strategies keep the term queer in dynamic contestation and discuss how the term itself is deployed within these projects.

This continent has a rich history of queer exhibition-making starting in the late 1970s, ranging from activist-led projects to institutional exhibitions. For an exemplary timeline of Australian queer exhibitions between 1977 and 2016, read the doctoral thesis of Tuan Nguyen, ‘Queering Australian Museums: Management, Collections, Exhibitions, and Connections’, submitted in 2018 to the University of Sydney.Footnote8 Easily, this article could have addressed an exhibition history that extends to the more recent work of our colleagues Jeff Khan, Kyra Kum-Sing, Dominic Guerrera, José Da Silva and Kelly Doley, Brent Harrison, Abbra Kotlarczyk and Madé Spencer-Castle, Alec Reade and Kalyani Mumtaz, Angela Bailey, Daniel Mudie Cunningham, and Léuli Eshrāghi.Footnote9 At the time of writing, Sydney WorldPride has a program that addresses queer and LGBTQIA+ histories, identities, and practices,Footnote10 including exhibitions The Party, curated by José Da Silva and Nick Henderson and Fulgora, curated by EO Gill, as well as the performance-rich First Nations ‘gathering space’ Marri Madung Butbut (Many Brave Hearts), hosted by multi-arts venue Carriageworks. This article seeks to contribute towards and act in solidarity with the vast practices, skills, and knowledges of these curators.

We have limited our scope to five projects that we have attended, curated, or made contributions towards, which we discuss in chronological order. The selection therefore enables both a discursive and embodied reflection on these projects.

Language Is a River, Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne, 27 November 2021–15 January 2022

Melissa Ratliff: Language Is a River was a group exhibition that I co-curated with Hannah Mathews in 2021. It included films and audio-based works by six Australian and international artists whose various forms of narration (spoken, captioned, sung) brought attention to language—its self-affirming/self-creation aspects, alongside philosophical, social, and cultural considerations. Less explicitly, though legibly, it platformed queer subjectivities: by this I mean both the participating artists’ own sex/gender identifications, and the platforming in their works of open-ended, relationally constructed understandings of identity that reflect queer’s ‘engagement with post-structural critiques of subjectivity and individual or collective identities’.Footnote11 Charlie Prodger (whose video BRIDGIT, 2016, was exhibited) talks about the formation of her subjectivity as an ongoing ‘enfolding’ process, in which the language and histories of queer elders like Samuel Delany and Sandy Stone play a constitutive part.Footnote12 Sarah Rodigari’s audio installation Towards an Affective Measure (2021), which was created for the exhibition, also demonstrates this understanding of a composite self through its method: the work’s centrepiece is a scripted monologue collaged from remarks and phrases the artist gleaned during a series of walking interviews. These and other works reinforced processes of becoming, rather than static identity positions. The figure of the river conveys this fluidity, and also holds lots of productive tension: immersion, swimming, floating, sinking, drowning, etc.

Peter Johnson: I was speaking recently with the artist and curator Fayen d’Evie about languages that exist beyond the written or verbal. She spoke about vibrational poetics, languages that aren’t fixed or easily translatable, or held in dictionaries or lexicons; language as a space for negotiation of new identities, for slippage, for movement into that space between sense and nonsense.Footnote13 It made me think about how we name—explicitly or otherwise—queer exhibitions and, for that matter, queerness itself. How does the poetic nature of your exhibition title reveal or conceal the show’s queerness? And does that matter?

MR: I was very conscious in its framing that labelling with respect to identity politics is fraught, being at times necessary—and helpful in giving clarity to political struggles—but many times also disabling or limiting. I was interested in pointing to queerness via fluidity but also wanted a title that would not overtly out or label or cast an unwanted sensibility onto the artists.Footnote14 The title comes from a saying quoted in one of the exhibited works, Commerce des Esprits (2018) by Shen Xin, that says ‘a good swimmer will in no time get the knack of it, that means he’s forgotten the water’, and also ‘Language is the river I’m in, and we need to forget each other.’ That tension in being an adept or floundering in the medium of language seemed to me to be metaphorically poetic and powerful with respect to queer thriving and queer struggle.

From my perspective, I wasn’t interested in it being a ‘queer exhibition’, but as a queer identifying curator I was interested in how some queer artists were rejecting a certain kind of authorship by acknowledging the porous and contingent nature of the self. I did have ‘queer’ in early drafts of the curatorial statement, but in the end I felt that the umbrella term would close down the works’ multiple meanings and foreclose other identifications. Gloria Anzaldúa wrote that ‘we must not forget that it [queer] homogenizes, erases our differences’.Footnote15

A colleague recently asked me about the ambiguity of the exhibition’s framing, and we had an interesting discussion about the political necessity of bannering exhibitions more explicitly as being about/for sexual and gender minorities in the 1980s and 1990s, and whether an approach like this would have been possible then. I imagine not (I began working in the art field in the 2000s), but I wonder if in some contexts it might have worked in the 1970s (policing and criminalisation aside).

Frances Barrett: This makes me consider Nayland Blake’s approach to curating in the early 1990s. Blake didn’t want to explicitly use the terms gay, lesbian or queer in a project’s title, saying

The title is the doorway through which the viewer enters the exhibition. If we essentialize the work of these artists in the title, we limit the viewers’ chances of being able to find new information and connections among the works. The artists would be once again ghettoized.Footnote16

Could you elaborate on what you mean by your role as a ‘queer curator’ as opposed to developing a queer curatorial framework or methodology?

MR: I think my role was to imbue the project with a queer subjectivity and set of references, and to be visible within my institution, in addition to delivering usual forms of curatorial support and organisation. I am interested in methodological and structural experimentation as well, but in this context my contribution was more discursive and representative. I am lucky to work in a context where I’m encouraged to have a voice and leadership in projects that work against the invisibilisation of difference, but Blake’s statement does also resonate with me.

PJ: This makes me think of the work of Archie Barry (who was in Language Is a River) and Bhenji Ra, and Ra’s views about the dangers of legibility and the power that can be gained by resisting it.Footnote17 Rendering oneself visible or intelligible to others gives them the capacity to describe and identify you, to bind you to various prejudices and structures of power, and to make you the subject, potentially, of violence. So, there is a strategy in obfuscation—or at least in not making one’s queerness immediately legible to those who might meet it with scorn or violence.

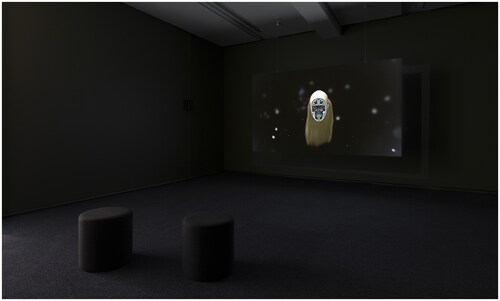

MR: Absolutely. Barry included an animated avatar of themself in their work Scaffolding (Preface) (2021) in the form of a twirling head whose embodiment, or enheadment, radically defied systems of recognition; the persona (based on a 3D scan of the artist’s head) is the work’s narrator who vocalises without words, has no prefrontal cortex (therefore no facial features) and spins, so that any ‘frontal’ views are obscured by floating blonde hair ().

Figure 1. Archie Barry, Scaffolding (Preface), 2021, single-channel 4K video, stereo sound, 11 min 20 s. 3D modelling: Savannah Fleming, 3D animation: Ben Jones, Courtesy of the artist. Installation view, Language Is a River, Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne, 2021. Photo: Christian Capurro.

QUEER: Stories from the NGV Collection, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 10 March–21 August 2022

PJ: QUEER: Stories from the NGV Collection ran for five months across the entirety of the third level of NGV International, Melbourne. It brought together close to 400 works from the Gallery’s various collecting departments, from painting and sculpture to fashion and design—the largest such collection display in the Gallery’s history. The exhibition was conceived and organised by a group of in-house, queer-identifying curators—Ted Gott,Footnote18 Angela Hesson, Myles Russell-Cook, Meg Slater, and Pip Wallis—during Melbourne’s COVID-19 lockdowns, which, at the time, were the longest enforced lockdowns in the world.Footnote19 Having worked for the last few years in a major collecting institution, I understand the significant resources—financial, temporal, intellectual, and emotional—that would have been required by all parts of the organisation, especially its queer staff, to realise this project. QUEER was, by all institutional standards, a major investment and statement of values.

As an institutional survey of works by queer artists and about queer subjects, it was largely successful despite some significant ‘gaps’ in the collection (loudly acknowledged through wall texts and public commentary), especially works by women, trans and non-binary artists—as well as works from outside the transatlantic dipole. Despite the proliferation of queer representation in recent years, and the relative acceptance found by queer people in the arts, it was still deeply fortifying to see queer art and artists promoted so prominently by an institution with the authority and cultural capital of the NGV.

FB: Do you think an exhibition like this could create structural change within institutions such as the NGV?

PJ: I can’t speak to what the NGV has or hasn’t undertaken, but I think these sorts of exhibitions do have the capacity to be used as a way of evidencing and leveraging structural change. The recent Know My Name series of exhibitions at the National Gallery of Australia, which was a large-scale project celebrating Australian women artists working from 1900 to now, was internally a way to embed and make arguments in support of a larger gender equity action plan. The exhibition and the action plan went hand-in-hand as part of an internal strategy of structural change and an external, communication-focused strategy articulating the Gallery’s priorities. There’s a feedback loop between what you say publicly, and then being accountable to what you say.

MR: What about as a curatorial endeavour? When was the exhibition most successful and what didn’t work?

PJ: The show was at its strongest when it created conversations between works of different mediums and periods to tell specifically queer stories. The gallery about queer spaces, with its depictions of beats, lesbian bars, and bathhouses, stands out in my memory. There were a number of works included that were not grounded in a lived experience of queerness but rather, it was argued, displayed a ‘queer sensibility’ (such as Art Nouveau decorative objects). As noted by art historian Amelia Jones, such sensibilities often only exist with reference to a very narrow section of the queer community—most often white, rich, cis, and male. Camp and other queer modalities not necessarily rooted in identity sat uneasily alongside a larger narrative of artistic expression arising from lived experience. The retellings and reshapings of various histories to highlight their queerness were well supported and at times poetic, but there were moments where it became almost gossipy—wall texts for certain works speculating about the artist’s or subject’s sexuality or gender through historical hearsay.

FB: As a counterpoint, this makes me consider Gavin Butt’s argument that gossip is the real stuff of art history, particularly in relation to queer artists from earlier periods of time:

What I want to propose… is that rather than lamenting this lack of hard evidence as something which undermines the securing of iconographic meaning in works of art, we might explore the sexual uncertainties which proliferate around such scenes of sexual interpretation as discursive phenomena in their own right. That is, insofar as the homosexuality of this era comes to be the subject of rumor and suspicion both for the art-world gossips in New York then, and for contemporary historians now, I take the practices of gossip and rumor-mongering as fundamental to its very representational construction.Footnote20

It’s an interesting question of how to judge the success of such a project and its curatorial model in relation to the sometimes slippery aspirations of queerness. An exhibition at a major state institution such as the NGV is understandably beholden to its audiences—to accessibility and education—and, as such, it was largely conventional in its exhibition display and interpretation strategies. Works were grouped by theme or chronology, accompanied by scholarly wall didactics. QUEER was an exhibition for queer people, but it was also for everyone else, so that our stories might be better known and understood beyond our communities. Using traditional framing devices and exhibition technologies, while perhaps not queer unto themselves, seemed to me to be in service to a larger and admirable goal.

FB: Pete and Mel, how did QUEER impact your thinking as individuals working within institutions?

PJ: There is a temptation to see institutions as monolithic or entities unto themselves, but they are only ever groups of people, of individuals, subject to larger economic and cultural forces just like everyone else. It’s my experience that, by and large, cultural institutions are made up of people doing their best day-to-day to enable change. Clearly such museums and galleries can have significant cultural impact—both a responsibility and an opportunity—but they only ever exist in dialogue with an audience. It’s laudable that the NGV chose to have a queer exhibition as their major summer show, but that wouldn’t have been possible or successful without a long history of queer activism leading to a significant shift in societal attitudes over the last few decades.

MR: I have similar views to Pete. I think what impacted me most was witnessing how validating these kinds of exhibitions can be for people with histories of exclusion. To be among the intergenerational audience at the opening and experience it as something extraordinary taking place within those imposing walls, to see people seeing themselves represented and being energetically engaged, was a bolt of understanding—that even through exhibitions, a little more ease is created for a lot of people. The NGV became another space to breathe. While the scale and ceremony of QUEER could admittedly also be seen as a consequence of homonormativity, I agree that its existence owes a huge debt to what our colleagues and people in equal opportunity and diversity roles have been doing over time.Footnote21 There are so many efforts that we’re not even aware of.

FB: I think of projects like Parallel, which is a research project led by Dr Verónica Tello, Distinguished Professor Ien Ang, and artist Salote Tawale. Parallel is asking ‘how we transform our museum’s relationship to non-Anglo and culturally and linguistically diverse art communities’ and is working closely with Murray Art Museum Albury.Footnote22 It is aiming for structural change within the museum sector in Australia by initiating a suite of curatorial projects with curators such as Evgenia Anagnostopoulou and Kelly Dezart-Smith.

Meatus, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA), Melbourne, 2 April–19 June 2022

MR: Coming to Meatus, curated by you, Frances, how it dealt with its institutional, curatorial, and social contexts in ways that resonate as queer was immediately present to me on the levels of language and framing. You chose to decentre your curatorial position by describing the project as ‘led by’ rather ‘curated by’ you. You also responded to what is traditionally a solo commission (ACCA’s Katthy Cavaliere Fellowship) by bringing multiple artists together and by becoming both and neither artist and curator—or, to use the term that you adopted in your dissertation, ‘artist-cum-curator’.Footnote23 The strange not-quite-duality of this hyphenated identity (artist-curator itself being a fairly common descriptor) is charged with the transgressive connotation of ‘cum’—i.e., a perversion or play on ‘come’ in a sexual sense, in addition to its Latin meaning of ‘with’ or ‘along with being’. The title is also suggestive of multiple modes of embodiment. Meatus are bodily openings, and I love how the title calls up the diverse sensing and mechanical operations of bodies.Footnote24

As a project that used ACCA’s spaces as connected sound passages and wanted to ‘explore practices of listening that decentre the ear to activate the entire body, attuned to both conscious responses and unconscious intensities’,Footnote25 it seemed explicitly anti-narrative, in addition to its reorientation of the sense value chain. Was that something that you were intentionally addressing?

FB: Yes, it was. As a curator there is an expectation to shape a narrative around a project through wall texts, catalogue essays, programs, or public talks. As part of Meatus I wanted to complicate the notion of a singular, coherent authorial voice and narrative, and instead offer up my composted, wormholed, propositional thinking. Through a live performance with Hayley Forward and Brian Fuata, called Curator’s Talk, I performed a curatorial text as my voice was modulated to various frequencies, making my words more or less intelligible. This was an attempt to demonstrate to an audience the collaborative, embodied, durational, and performative processes of the curatorial role.

PJ: Very sadly I missed Meatus by 45 minutes as my plane was delayed. As such, I am interested in understanding the exhibition as an embodied experience—what the sounds felt like in your chest, down your spine, rising up through the soles of your feet.

MR: I can offer my description to start with. The interconnected chambers at ACCA were populated with individual sound installations by artists Nina Buchanan, Del Lumanta, and Sione Teumohenga, and the immersive sound environment that Frances, Hayley Forward, and Brian Fuata created for the largest space (). The lighting drenched the galleries in primary red, so that entering, you felt like a miniaturised traveller through organs and bodily passages.Footnote26 There was real pleasure in listening to the sounds of the exhibition through your ears as well as your gut region. I felt like I was invited to inhabit the space however and wherever I wanted, and to spend time, which I did, sitting on the carpet. The lighting was cocooning; you didn’t feel as observed as you do in the white fluoro, bright light scenario of most contemporary galleries. My senses felt very satisfied.

Figure 2. Installation view, Meatus, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne, 2022. Image of sound installation by Frances Barrett, Brian Fuata and Hayley Forward, worm divination (segmented realities), 2020. Photo: Andrew Curtis. Image courtesy of the artists.

I also recall the sculptural aspects of the sound—the distributed speaker equipment and the wriggly cables drawing lines through the spaces. Visual and tactile stimulation were present, but with reduced bandwidth, so that the sound experience was foregrounded.

Sound and listening have been recurring aspects of your curatorial practice, Frances. The strategy also decentres the hierarchical primacy of visuality as the mainstay of exhibitions and its attendant mode of knowing the world through seeing, imaging, mapping, and cataloguing—ways in which science and Western epistemologies make meaning. Meatus shifts perception from the outside eye (spectatorship, seeing as knowing, single perspective, single system) to the inside, composite array (multiple functional and sensate operations, sensing as knowing, plural system). The visitor cycles through the overall environment by following each individually authored sound work, timed to play one after another. As such, this is more of a conversation than a speaking-over. I see these aspects of conversation, contamination, and intermingling as some of the key values of the project.

Your co-created work worm divination (segmented realities) (2020) struck me as representing a different but related strategy. Brian Fuata’s vocalisation worked against a sense of certainty of meaning that is often attempted by art spaces through emphasis on refinement and narrativisation. Fuata goes from an affective, linguistic vocality to a kind of convulsed, nonlexical vocality.

FB: I am interested in performance; as a curator I try to create spaces for performed or embodied gestures. I’m interested in making an audience critical in the realisation of the work. The audience plays a role in the project, either as a witness or a listener, by configuring their bodies ‘in the round’ or cruising through a space. Performance itself demands a heightened sensitivity to other bodies in space and in time. Underlying Meatus is a heightening of the experience of listening to register the sensations and intensities of your own body, and in relation to others in the space too.

PJ: I find the refusal of the ocular—or at least its substantial demotion—fascinating as a queer strategy. As you mentioned, Mel, to observe visually is at the apex of Western ways of knowing—but it is also how we understand ourselves to be a body and personage that can be seen, à la John Berger,Footnote27 and subsequently surveilled, à la Michel Foucault.Footnote28 To deny sight is perhaps to deny legibility, as discussed previously, and in doing so entice us to find pleasure and meaning through our other senses.

VERS: On Pleasures, Embodiment, Kinships, Fugitivity and Re/Organising, Samstag Museum of Art, and Adelaide Contemporary Experimental, Initiated by Monash University Museum of Art, 17–18 June 2022

MR: Frances and I were part of the advisory panel and organising committee for VERS, a curatorium that included Arlie Alizzi, Archie Barry, Léuli Eshrāghi, and Jeff Khan. This symposium-cum-exhibition-cum-performance program was held over the course of two days, inviting artists, curators, and arts workers to engage in conversation on a range of topics, including ‘pleasures, embodiment, kinships, fugitivity and re/organising’. Pete, we are interested in your experience of VERS as a participant—how you felt, what you noticed or learned.

PJ: Throughout the event it was made clear that process rather than outcome was of the greatest importance. It didn’t matter if we didn’t reach ‘answers’ or propose ‘resolutions’ as in a more traditional conference—the meat of the matter lay in the affective, the discursive, and the unresolved. In the opening conversation between artists V Barratt, Brian Fuata, and Daniel Jaber, moderated by yourself, Frances, each participant was asked to define what improvisation meant to them. Fuata’s response was: ‘Improvisation… is a way to make the audience supple.’Footnote29

This foundation in collective creativity and open-ended modes of enquiry foregrounded and held space for the emotional realities of participants in a way implicitly discouraged by traditional models. The major conversations on the second day were structured sequentially around the stated themes of the event, each with its own facilitator and line of questioning. However, even this loose structuring seemed ultimately at odds with a participant cohort primed to dwell in conceptual messiness and to resist rationalist strategies of analysis and understanding.

The loudest elements of the resulting discussion—which started to share an energy with durational performance given its four-hour continuous runtime—were expressions of trauma: stories of racial violence and sexual violence, of misogyny and structural exclusion, of exploitation and abuse by institutions, of lateral violence within the queer community, of a long spiral towards exhaustion and the eternal appeal of the void. As a participant and observer, it was at times emotionally difficult. Many queer people experience a foundational trauma—one caused by the rejection we experience and internalise as we begin to come into our gender and sexual identities. While trauma can bring us together, healing and creating community, it also tends to compound and be re-enacted.

As a curatorial model, VERS successfully and self-critically enacted so much of contemporary queer thinking. Its emphasis on distributed power and collective decision-making, and its embrace of affective ways of knowing and making meaning, created a forum in which participants felt safe to both speculate and divulge. What is interesting to me for future iterations is how to facilitate and shape these discussions in a way that can find space for hope or a positive way forward. And where that isn’t possible, perhaps because of the emotional weight of the discussion, how to hold the participants safely through that experience.

FB: Pete, do you feel like VERS transferred its focus on embodiment to an audience experience?

PJ: The event was framed by and interwoven with performance, centring the propulsive and creative force of physicality and situating the participants in relation to one another not just intellectually, but as fleshy, desiring beings.

Before the opening session, Fuata described the circular seating arrangement as an anus, which sat with me throughout the rest of the weekend, meaning that it sometimes felt like our discussions were taking place as part of a ritual rimming. The discussion circle is a classic for a reason: it brings people together, flattens hierarchies, and encourages empathy. It makes you aware of others as bodies in space who laugh, become frustrated, sweat, fart, get bored—it literally fires the mirror neurons in your brain ().

Figure 3. Seating arrangement for VERS: On Pleasures, Embodiment, Kinships, Fugitivity and Re/Organising, Samstag Museum of Art, Adelaide, 18 June 2022. Photo: Sia Duff.

One of the things that we’ve noticed talking through these examples is the centring of collaboration and collective action, but particularly pronounced in VERS is the way that you worked with the rest of the curatorium to devise the project. How was that process?

FB: Working collectively meant we had many different perspectives, knowledges, and experiences feeding into this proposition of creating a queer symposium. The conversation between us as a collective set up and framed the event. Conversation was the underpinning modality in which we worked together, so in turn the outcome continued that modality. I also think collectivity enables an extended network of people to be involved in a project.

MR: It’s necessary. Not only for the pleasure of working with and learning from others, but we had to have several people bring as many different perspectives and experiences as possible to that format to work against the homogenising potential of the label queer (which the name VERS also sidestepped).

PJ: I understand your decision to organise the event collectively to be a clear queer strategy. Many queer people find safety in found families and communities, and we have been able to exercise our power by organising collectively (a model with long roots in the feminist and labour movements). I would argue that it’s particularly important for queers as a group of people with distinct yet interrelated identities that intersect with other backgrounds and ways of being to embrace collectivity as a means of representing the breadth of experience and diversity in our communities.

MR: Safety, power, and representation, but energy and possibility too. The curatorial group wanted to create a dynamic space for robust discussion, so we invited as many speakers as our budget allowed.

Screwball, Verge Gallery, Sydney, 22 June–22 July 2022

FB: Screwball was an exhibition at Verge Gallery curated by the filmmaker, EO Gill. Screwball is a horny framing of recent queer video and performance practices, and loosely tethers queer video and performance practices across the two sites of Los Angeles and Sydney. This exhibition leverages the tenets of Gill’s own video practice, which ‘mines film culture and genre’ and contributes to the larger discourse around artist-curator models.Footnote30 Gill built a curatorial framework around the ‘screwball’ as a methodology for image-making and performance. The screwball, Gill argues, perversely agitates conventions of image-making and performance by engaging the obscene and humour, ‘relational, non-normative forms of sensuality, pleasure and connection’, citation, performativity, and a camera that edges rather than delivers.Footnote31 The strength of Screwball is that its central argument moves away from the optics of queer representation and hypervisibility, and instead turns to the slippery, playful, and withheld as strategies for queerness as method.

PJ: How did those queer strategies manifest through the exhibition? Did it impact the design of the space or the way in which interpretive materials were conceived?

FB: The exhibition design included the pasting up of the exhibition catalogue cover over the usually transparent glass entrance of Verge Gallery. The catalogue cover featured the ‘comedy’ and ‘tragedy’ portraits of Chloe Corkran and Athena Thebus, whose bruised, bandaged, and cream-pied faces multiplied across the gallery’s façade immediately drew connotations of masking, slapstick, and the surgical opening of bodies. Inside the darkened gallery space, Corkran and Thebus’s portraits were situated as centrefold spreads of imagined magazines presented as two large vinyl decals on the gallery wall (). A changing room bench was offered to audience as seating to watch a showreel of video works by artists such as Brian Fuata, Garden Reflexxx, Sione Monu, P. Staff, and Archie Barry. This isolated bench held a homoerotic aesthetic suggestive of a gay porno setting, and as such, positioned the gallery space as a potential site of erotic encounter and action. Nat Randall and Anna Breckon’s suite of videos depicting cold and calculated office-based roleplay were presented across several screens. My own work, a series of printed scripts for a performance about a character called Doctor Mother, was taped up onto a wall using neon-pink gaffer tape.Footnote32 Performance is centred in the works presented in Screwball, with recurring artistic strategies of characterisation, improvisation, collaborative gesture, and vocalisation.

Figure 4. Chloe Corkran and Athena Thebus, In Dramatic Roles Such as These, 2022, wallpaper, 61 × 1600 cm. Installation view, Screwball, Verge Gallery, Sydney, 2022. Photo: Jessica Maurer.

Gill’s work depends on a community of practitioners who often contribute directly to the work as editors, performers, or supporting film crew. Screwball replicates this web of peers and influences. I consider Fuata’s video, Negativity, most incisively demonstrates this. Fuata performs three improvisations across three different sites and bases these improvisations on an encounter he had with a gardener and a stripped castor oil plant. Negativity is filmed and edited by Screwball artists, Garden Reflexxx (Jen Atherton and André Shannon). Two of the sites of Fuata’s performance are in the contexts of other queer projects: his, Hayley Forward, and my collaborative sound installation, worm divinations (segmented realities) that Mel mentioned earlier, and Randall and Breckon’s set of their theatre work, Set Piece, at Arts House. Throughout one of his improvisations Fuata wears a hand-painted shirt by artist Kelly Doley. Fuata then reappears later in another video work, performing in Jimmy Nuttall’s Fabulina. This webbed citation of artists, projects, and even costuming is a generous call and response to a community of aligned practitioners. As Verónica Tello in her review of Screwball for online platform Memo Review points out: ‘Behind a wall of porn-magazine covers, which transform Verge into an illicit space, however temporary, Gill has created a shelter for their screwy community to cum—or not—together.’Footnote33 Screwball builds a sense of community through the citational practices at play within the works.

MR: I love your acknowledgement of the ‘webbed citation’, or in Tello’s words ‘screwy community’, behind this exhibition, which also speaks to your own work, Frances. We work in community and in relation with people, where possible, over and over, and as much as we can. I remember watching a video conversation online between artists and partners boychild (Tosh Basco) and Wu Tsang where they talk about doing what they do so that they can be together; making work together to keep on making work together.Footnote34

FB: Even threaded throughout this article that we’re writing, you can see artists like Fuata and Barry appearing and reappearing in the different projects. So again, this article is reflecting that same webbed ‘screwy community’.

PJ: I was really interested in the horniness of Screwball, because sex, desire, and horniness (or the lack of it) are fundamental to the queer community and queer experience, and it’s not necessarily something that’s come through strongly in a lot of the other projects. Gill’s foregrounding of it, of literally having to walk through a porn magazine centrefold of sorts to get into the exhibition, is really fun and really interesting. So how did that feel and work for you as a participating artist, and the effect in the show, Fran?

FB: Gill is interested in that tension between implicit and explicit erotic encounter, specifically in film. I think it’s really a foundational interest in their own practice, and so they’ve tethered that interest to other peers and really drawn that quality out of the included works.

The horniness did prove difficult in some ways… Gill had scheduled a screening event by Dirty Looks Inc., a platform for queer film, video, and performance founded in 2011 by Bradford Nordeen.Footnote35 The event was going to screen four film works that spanned the time period of 1971 to 1985. As Gill wrote to me, this timespan

is significant in its alignment with the AIDS pandemic. And though COVID-19 did not have the same impacts re: shaming of queer sexuality, I thought the positioning of queer erotic works at this moment in time would be important in helping viewers to navigate, learn and re-think bodies, sexualities and intimacies at a time of isolation caused by a global pandemic.Footnote36

This would have been the first time Dirty Looks Inc. presented their programming in Australia. What stopped Gill and Verge from presenting this program was complications around screening unclassified films. There was ambiguity around whether the films presented were artworks or erotic films, and what distinguishes an artwork from an erotic film is the notion of artistic intent. The artistic intention of two of the programmed films were not able to be proven because their authors were unknown or deceased. Due to the time constraints, Gill and Verge were unable to build a case for the films’ artistic intent so had to cancel the event. Fortunately, Dirty Looks Inc. will be involved in screening two of these works in Gill’s curatorial project, Fulgora, at the National Art School in Sydney.Footnote37

In Conclusion

MR: As we’ve landed in the present moment, could we conclude with some suturing thoughts on what we’ve discussed? How do these curatorial strategies that we’ve been discussing keep the term queer in dynamic contestation?

FB: I am drawn to the strategies of artists and curators who are moving away from queer optics towards the shared and processual, the affective, and performative. I return to Screwball and Fuata’s work Negativity, where he laughs at his own joke about the naked tree only to be met with a silent glance from the gardener. His joke and laughter are not received by the gardener, which imbues this fleeting moment with ambiguity. I consider this laughter and moment to resound with queerness: the laughter as a call to another, somatic joy, agitative humour, and embodied force. In a climate of increased anti-queer and anti-trans violence, joy and pleasure seem more critical, more necessary.Footnote38

PJ: I find the theoretical positioning of queer solely as a state of irresolution of relationality personally unsatisfying. For me, queerness is physical and present—it’s having been kicked out of the heteropatriarchy and realising that the system was rotten to begin with. It’s ‘not gay as in happy, queer as in fuck you’. When I look at the themes and commonalities that emerge from these examples of queer curating, I see strategies that respond directly to lived experiences of otherness and all the forms of violence that entails. Working collectively is a means of reclaiming power by coming together; making decisions collaboratively is a rejection of a singular authority; privileging embodied and affective knowledges resists rationalism and its tendency to divide and cut away; playing with language lets us imagine and build new worlds, intimacies, and ways of being. These strategies are deeply queer and inherently political; they live and flourish in the material and temporal; they offer a better way forward.

MR: Could I add just one more thing: queer as irritant. I like that term on a spectrum of positive and negative affects and excitements, and want to add a grain of sand to the idea of the ‘better way forward’. Queerness, following Sara Ahmed and Heather Love, is also constituted by orienting and feeling ‘backwards’. For me, the political project is also not to reproduce Western humanist progress narratives—not just replacing one positivist regime with another. It’s living lovingly and knowingly in the messes we co-create.

Disclosure statement

One of the authors is employed at Monash University Museum of Art, which initiated two of the projects under discussion.

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14434318.2023.2265126

Notes

1 The event program and audio recordings are available from the Monash University Museum of Art website, ‘VERS: On Pleasures, Embodiment, Kinships, Fugitivity and Re/Organising’, https://www.monash.edu/muma/public-programs/previous/2023/vers-on-pleasures,-embodiment,-kinships,-fugitivity-and-reorganising.

2 Lauren Berlant and Lee Edelman, Sex, or the Unbearable (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014), ix–x.

3 June Miskell and Bhenji Ra, ‘The “Women’s Show” After House of Slé: A Dialogue Between Bhenji Ra and June Miskell’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art 22, no. 2 (2022): 172–186, DOI: 10.1080/14434318.2022.2143755.

4 The conveners were Dr Peter McNeil FAHA, Distinguished Professor in Design History, School of Design at UTS and Richard Perram OAM, Director, Bathurst Regional Art Gallery. Invited guests included Clare Barlow, Dr Pawel Leszkowicz, Branden Wallace, Bill Zewadski, Michael Carnes and Robert Lavis, Assoc. Prof. Andrew Gormon-Murray, Assoc. Prof. Maryanne Dever, Dr Christine Dean, and Gary Carsley. Of the twelve participants, four were international, seven Australian. See https://aaanz.info/queer-curating-queer-art-queer-archives-uts-18-october-2017/ (accessed 10 February 2023).

5 For audio recordings of Queer Exhibitions/Queer Curating: A Cross-Cultural Symposium, go to the symposium’s archive on the Museum Folkwang website, https://www.museum-folkwang.de/de/blog/queer-exhibitionsqueer-curating (accessed 10 February 2023). The final roundtable participants included Jonathan Katz, Clare Barlow, Amelia Jones, Thom Collins, and Maura Reilly, with contributions from other symposium speakers and audience members.

6 Amelia Jones, In Between Subjects: A Critical Genealogy of Queer (Abingdon: Routledge, 2020), 2.

7 Here we acknowledge our positions as white settler authors, working in the institutional contexts of the University of South Australia, Newcastle Art Gallery, and Monash University Museum of Art.

8 Vu Tuan Nguyen, ‘Queering Australian Museums: Management, Collections, Exhibitions, and Connections’ (PhD diss., University of Sydney, 2018). See also Tuan Nguyen, ‘Co-Existence and Collaboration: Australian AIDS Quilts in Public Museums and Community Collections’, Museum & Society 16, no. 1 (2017): 41–55, and ‘Mediating Queer Controversy in Australian Museum Exhibitions’, Historic Environment 28, no. 3 (2016): 36–48.

9 Projects since 2016 include Day for Night, curated by Jeff Khan at Performance Space (2014–present); the ongoing exhibitions at Boomalli Aboriginal Artists Co-operative for the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, with the last several exhibitions curated by Kyra Kum-Sing; Staunch, curated Dominic Guerrera at Nexus Arts (2021); Friendship as a Way of Life, curated by José Da Silva and Kelly Doley at UNSW Galleries (2021); Here&NoPJ0: Perfectly Queer, curated by Brent Harrison at Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery (2020); Queer Economies, curated by Abbra Kotlarczyk and Madé Spencer-Castle at Bus Projects, CCP and Abbotsford Convent (2018–2019); Queer Blak Futurism, curated by Alec Reade and Kalyani Mumtaz at Artspace and Black Dot Gallery (2018); WE ARE HERE, curated by Angela Bailey at the State Library of Victoria (2018); The Unflinching Gaze: Photo Media and the Male Figure, curated by Richard Perram OAM at Bathurst Regional Art Gallery (2017); and Pōuliuli (Faitautusi ma Fāʻaliga), curated by Léuli Eshrāghi at West Space (2017).

10 We use the abbreviation LGBTQIA + to reflect the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex, asexual/ally and ‘+’ (what cannot or cannot yet be labelled) identities addressed by WorldPride communication materials, but a local variation would be LGBTQIA + SB to acknowledge Sistergirl/Sistagirl and Brotherboy/Brothaboy gender identities in Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures. For this conversation, we have enlisted queer for convenience, out of an interest in investigating its use in the discussed projects, and to acknowledge our attachment to the Anglophone sphere as settler authors engaging with Western European–Northern American queer theory and politics. For a discussion of the global dissemination of queer, see Ashley Tellis and Sruti Bala, introduction to The Global Trajectories of Queerness: Re-thinking Same-Sex Politics in the Global South, ed. Ashley Tellis and Sruti Bala (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 17.

11 Annamarie Jagose, Queer Theory: An Introduction (Melbourne: Melbourne University Publishing, 1997), 87.

12 ‘TateShots: Charlotte Prodger’, Tate, 17 September 2018, https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/turner-prize-2018/charlotte-prodger.

13 For further reading about Fayen d’Evie’s conceptualisation of ‘vibrational poetics’ and language see ‘Post-humanity’, Routledge Companion to Audiences and the Performing Arts, ed. Matthew Reason, Lynne Conner, Katya Johanson, and Ben Walmsley (London: Routledge, 2022).

14 Fluidity is a trope tethered to queerness that strongly informs its mainstream, celebrated understandings (e.g., ‘gender fluid’ identities). For a discussion of queer concepts in anglophone contexts see chapter 5, ‘Queer’, in Amelia Jones, In Between Subjects: A Critical Genealogy of Queer Performance (Abingdon: Routledge, 2020), 186–247.

15 Gloria E. Anzaldúa, ‘To(o) Queer the Writer—Loca, escritora y chicana’, in The Gloria Anzaldúa Reader, ed. AnaLouise Keating (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009), 164.

16 Nayland Blake, ‘Curating In a Different Light’ (1995), PDF, https://archive.bampfa.berkeley.edu/exhibition/InaDifferentLight/Curating_In_a_Different_Light_by_Nayland_Blake.pdf (accessed 19 May 2023).

17 Miskell and Ra, ‘The “Women’s Show” after House of Slé’.

18 Gott was curator of the seminal exhibition Don’t Leave Me This Way: Art in the Age of AIDS, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 1994–1995, which brought together artists responding to the HIV/AIDS crisis.

19 ‘Australia: Melbourne to Bring an End to World’s Longest Lockdowns’, Al Jazeera, 17 October 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/10/17/australias-melbourne-set-to-end-worlds-longest-lockdowns (accessed 5 May 2023).

20 Gavin Butt, Between You and Me: Queer Disclosures in the New York Art World, 1948–1963 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), 6, emphasis in original.

21 Among others, Heather Love has observed how ‘advances’ in rights or visibility can ‘threaten to obscure the continuing denigration and dismissal of queer existence. One may enter the mainstream on the condition that one breaks ties with all those who cannot make it’. Heather Love, Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), 10. Rosanna Mclaughlin provides a cautionary critique about queering art history in the article ‘Queer: Some Notes on Art and Identity’, e-flux Criticism, 9 April 2020, https://www.e-flux.com/criticism/326676/queer-some-notes-on-art-and-identity.

22 For more information about Parallel see https://parallelstructures.art/.

23 Frances uses the term ‘artist-cum-curator’ to describe one of the pathways her research took towards ‘queering the curator’. Frances Barrett, ‘Meatus: A Curatorial Passage’ (PhD diss., Monash University, 2021), 3.

24 The word meatus is both singular and plural.

25 ‘Frances Barrett: Meatus’, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, https://acca.melbourne/exhibition/frances-barrett-meatus/ (accessed 4 December 2022).

26 Not only does the use of the drenching red light across ACCA’s gallery district have kinship with the red lights used to attract customers to sex work premises—and so intervenes in the stigmatisation of the colour connotation (in a way not dissimilar to the large-scale 1980s reclamation of the slur ‘queer’)—red light itself is thought to be therapeutic. Sabrina Rohringer et al., ‘The Impact of Wavelengths of LED Light-Therapy on Endothelial Cells’, Scientific Reports 7, article 10700 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11061-y; ‘LumiCure Torchlight’ product page, Lifepro Fitness, https://lifeprofitness.com/products/lumicure-torchlight (accessed 4 December 2022).

27 John Berger, Ways of Seeing (London: British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin Books, 1973).

28 Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Pantheon Books, 1977).

29 The other participants’ responses were also insightful and worthy of inclusion: ‘Improvisation is the accumulation of affect’ (V Barratt), and ‘Improvisation is going to the dressing up box to try something I’ve never explored before’ (Daniel Jaber).

30 EO Gill, ‘Screwball’, Volupté 5, no. 2 (2022), https://journals.gold.ac.uk/index.php/volupte/article/view/1670.

31 EO Gill, Screwball, exhibition catalogue (Sydney: Verge, 2022).

32 Frances Barrett, The Verses of Doctor Mother (2023), a series of five works of ink on paper.

33 Verónica Tello, ‘Screwball’, Memo Review, 9 July 2022, https://memoreview.net/reviews/screwball-at-verge-gallery-by-vernonica-tello.

34 ‘Boychild in Conversation with Wu Tsang, Wu Tsang in Conversation with Boychild’, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 2 December 2020, Vimeo, 1:01:32, https://vimeo.com/486397901 (accessed 13 February 2023).

35 For more information see https://dirtylooksla.org/about.

36 EO Gill, e-mail message to author, 15 January 2023.

37 Fulgora, Rayner Hoff Project Space, National Art School, Sydney, 3 February–5 March 2023.

38 Cait Kelly and Mostafa Rachwani, ‘What’s Behind the “Terrifying” Backlash Against Australia’s Queer Community?’, The Guardian, 25 March 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/mar/25/whats-behind-the-terrifying-backlash-against-australias-queer-community.