Introduction: The Rhizomes of Documenta Fifteen

I spot myself talking to artist Hamja Ahsan among a crowd of people in a Deutsche Welle documentary titled The Documenta Scandal.Footnote1 It is a strange feeling watching myself witnessing a historic moment, as Indonesian art collective Taring Padi’s large banner The People’s Justice is dismantled after a few days of public and media outrage in Germany. For other viewers, I serve a merely illustrative purpose, but for me, this is akin to an out-of-body experience. Unaware that a future self would spy on him through archival footage, my past self grapples with the enormity and the impossibility of comprehending documenta fifteen in its entirety.

Jakarta-based collective ruangrupa’s framework for documenta fifteen, lumbung, has been much discussed since they introduced the concept into the contemporary art lexicon, although it was already in operation in Jakarta prior to ruangrupa’s selection as the artistic direction of documenta fifteen. Lumbung means ‘communal rice barn’ in Indonesian, where surplus rice is kept for the benefit of the whole community. In ruangrupa’s description of this concept—which connotes communality, collectivity, and community—and its place in the context of documenta, ruangrupa argues, ‘if documenta was launched with the noble intention to heal European war wounds, this concept will expand that motive in order to heal today’s injuries, especially ones rooted in colonialism, capitalism, and patriarchal structures’.Footnote2 To realise their vision, ruangrupa and the artistic team initially invited fourteen collectives to take part in the fifteenth edition of documenta, to form a ‘collective of collectives’, which gradually expanded to around fifty artists/collectives and their ekosistem.Footnote3

As each collective and artist invited members of their communities, the exhibition grew in size and scope, and in unexpected directions. In that respect, the fifteenth edition of the ‘museum of 100 days’ could be described as rhizomatic in the way Deleuze and Guattari define that concept: ‘In contrast to centered (even polycentric) systems with hierarchical modes of communication and preestablished paths, the rhizome is an acentered, nonhierarchical, nonsignifying system without a General and without an organising memory or central automaton, defined solely by a circulation of states’.Footnote4 Indeed, ruangrupa’s conceptualisation of the lumbung model makes use of that very term, albeit not with reference to Deleuze or Guattari:

Ideally, lumbung can be a model that can be owned, adapted, developed, and utilized by many, without rigid control. This way membership is not needed.

To further dissolve memberships, awareness of scale is paramount; how to keep it small-to-medium and agile, never too big. How cellular organisms or rhizomatic structures split themselves up in order to keep themselves small is a useful model to learn from. Large scale brings unsustainable consequences. Not enough systematic thought has been given to scale.Footnote5

My perception of documenta fifteen has been informed by my lived experiences as a precarious migrant worker in Australia, and my long-time participation in DIY (do-it-yourself) zine, comics and independent music scenes as a practitioner and community organiser, as well as my existing research into the Turkish Gastarbeiter (guest worker) phenomenon in Germany and its artistic expressions. A lot has already been said about the anti-Semitism allegations against documenta fifteen artists that resulted in the covering and later dismantling of The People’s Justice banner installation, and I do not wish to delve into that topic further. My interest is in the experiences of the artists as cultural workers, and this article mostly focuses on that aspect of the exhibition. Here, my approach is similarly rhizomatic, tracking several trails of thought and assembl(age)ing a series of impressions, free associations, histories, personal interests, scholarly research, and embodied knowledges. As such, I adopt a loose methodology of autoethnography, field work, and interviews to scratch the surface of documenta fifteen and the lumbung framework from a political economy perspective, identifying artists, curators, curatorial assistants, and other documenta staff as precarious guest workers, providing their labour in a neoliberal western art context.

In this article, I start with a discussion of DIY collectives and zinemakers who participated in documenta fifteen as artists. As a zine practitioner, I was pleasantly surprised to find many other zinemakers and zines in the context of the exhibition. My discussion provides insights from those artists who have found themselves in a contemporary art mega-event with a multimillion Euro budget after spending many years self-organising their events. Next, I discuss the funding model of documenta fifteen, and how money allocated to each artist or collective was expected to be used, which often resulted in unpaid creative or affective labour on the part of the artists. The ensuing sections provide a historical and locational context that informed the hostile, sometimes racist and paternalistic attitudes towards the artists, and argue that the political and media reaction to the lumbung community was informed by a 70-year history of migrant guest workers in Germany. Lastly, I investigate the working conditions of documenta staff, such as the art mediators (sobat-sobatFootnote7) and curatorial assistants, whose job it was to make sure the logistics and administration required to achieve the ideal of lumbung was in place, and who felt burned out after the scope of the ever-changing exhibition grew out of proportion ().

Decentralised Organisation at the Centre: Zinesters at Documenta

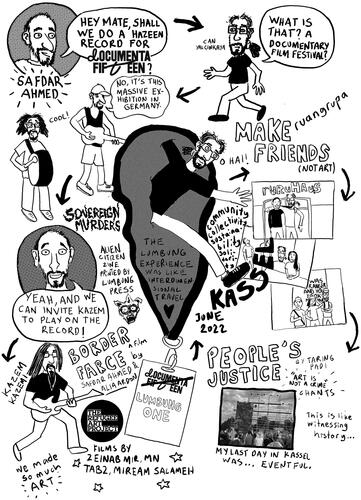

I first became aware of documenta when my friend and frequent collaborator, Safdar Ahmed, was invited to documenta fifteen by its artistic direction, ruangrupa, and the artistic team. My relationship with the contemporary art world had hitherto been tangential, only to the extent that it intersected with our scenes: the subcultures of zines, comics, punk, and extreme metal music. Safdar and I have both been involved in organising the annual Other Worlds Zine Fair in Sydney since 2015. We both make politically engaged comics and zines. We have also been performing and recording original songs as the anti-racist, Muslim death metal band Hazeen since 2015.Footnote8 Our live appearances have mostly been in the context of DIY zine fairs or contemporary art settings, such as Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art and at Sydney gallery Cement Fondu. As an individual artist, Safdar has gained great critical acclaim with his comics and graphic novels, such as Still Alive: Notes from Australia’s Immigration Detention System, which won several important literary awards in Australia and was published in France and the United States.Footnote9 He has also taken part in several group exhibitions and has been a spokesperson for Refugee Art Project, a community art organisation he co-founded.

For documenta, Safdar proposed a series of works that would combine all of those practices together. These included the debut Hazeen album Sovereign Murders, the two-channel video installation/experimental documentary Border Farce, and a 20-page zine titled Alien Citizen, as well as four films made by women of a refugee background: Zeinab by Zeinab Mir, Cleaning in Progress by Miream Salameh, Neverending by Tabz Jebba, and Take it Easy by MN.Footnote10 In Safdar’s words, ruangrupa ‘loved and wanted all of it’.Footnote11 As a collective, ruangrupa are also involved in making zines, playing music, and organising gigs and community art.Footnote12 Safdar felt an immediate affinity between his work and practice and ruangrupa’s.

For documenta fifteen, ruangrupa’s project was to bring hundreds of artists and collectives like ours, whose modus operandi was self-organising, into contact with a highly hierarchical, top-down, and bureaucratic institutional culture and see what happens. Even so, ruangrupa was already aware of the risk of such a proposition, and they defiantly declared that

when we were invited to make a proposal for the fifteenth edition of documenta, instead of integrating ourselves into the long-established documenta system, we decided to stay on our path. We invited documenta back, asking it to be part of our journey. We refuse to be exploited by European institutional agendas that are not ours to begin with.Footnote13

For ruangrupa, this meant importing process-based (rather than product-focused) diverse art practices related to community building rather than individual vision into a neoliberal Western art environment. They invited lumbung members and artists ‘based on how they practice. This was sometimes not immediately visible in their artistic work, but rather in the artists’ and collectives’ larger roles forming or participating in social and political movements’.Footnote14

This often resulted in a clash with the demands of documenta gGmbH and its shareholders to put on a material art show that displays distinct and new art works. One of the seven curatorial assistants, Gözde Filinta, tells me during a Zoom interview that ruangrupa and the artistic team’s focus on the lumbung and its many streams—lumbung Press, lumbung Gallery, lumbung Kios, lumbung Radio, lumbung.space, lumbung Film etc.—as well as the overarching economic structure and sustainability of the lumbung, meant that the question of what would be displayed at the show often had secondary importance. Having worked at large museum settings before, Gözde describes the anxieties of being stuck in between the demands of documenta gGmbH as an institution and the vision of the artistic direction and the artistic team as something she had not experienced before: ‘€40 million of taxpayer’s money [is being spent on documenta fifteen]. You need to display something to the people. They needed to show something in Kassel. But there were some artists who didn’t want to do that, [and in some cases] didn’t do this at all’.Footnote15

Berlin-based comics artist Nino Bulling was among the few German natives involved in documenta fifteen. Their insight provides clarity on the expectations of the institution and the public:

Some of the, I think, more radical aspects of the proposal of ruangrupa was actually this idea that things would happen in the communities of whoever’s contributing and that doesn’t have to be in Kassel. And I think that the institution was really working against this. But this was coming more like from the top level… because of the sort of like touristic value and, like, overall money-making value of this event for the city and the region, right. So, they couldn’t really see the kind of schauwert? Well, let’s say, like the value of the spectacle or something.Footnote16

This is not to say that independent art communities exist in a non-capitalistic vacuum. Those who have a greater understanding of the contemporary art world have had success in getting grants and funding, but these are few and far between. Similarly, extreme metal music is not generally regarded as high art and remains part of an underground culture in Australia and around the world. As Hazeen, through blurring the lines between extreme metal music and performance art and incorporating an anti-Islamophobic stance, we have garnered some media interest in Australia; however, it never led to a great amount of financial return beyond the largely symbolic artist fees we received for performing in art spaces.

Being involved in documenta fifteen meant that Safdar was given a production budget beyond our wildest dreams. Each artist was given ‘60,000 Euro for production with 10,000 Euro for collectives and 5,000 Euro for individuals’.Footnote19 The budget also included a collective pot for each ‘mini majelis’ (smaller groups of artists and collectives who regularly convened) who would determine how this money would be used together. We were not alone in feeling overwhelmed with a budget like this. Nino Bulling tells me, ‘coming from a DIY perspective, suddenly having to budget €60,000… I had no idea what I [was] doing’.Footnote20

We were not the only zinemakers at documenta fifteen. Indonesian collective Taring Padi, Kiri Dalena and Resbak collective from the Philippines, Hamja Ahsan from the UK, ook_ from the Netherlands, and Baan Noorg Collaborative Arts and Culture from Thailand, among others, all produce zines as an alternative mode of publication. Those artists and collectives I connected with during and after documenta have also commented on the contrasts between their own ekosistem and the grandeur of the event in Kassel. Alexander Supartono of Taring Padi says,

Some of us [asked] ‘if we want to participate, why?’ Of course, we know of the stature of documenta as one of the largest, if not the largest exhibition in the contemporary art scene, but as you know, that kind of art scene is not really Taring Padi habitus… The answer is we want to use documenta as a platform to campaign whatever issue we have been working in the past 22–23 years. That’s the departure point.Footnote21

London-based artist and activist Hamja Ahsan pointed out the ‘whiteness’ of documenta staff and made a comparison between the zine fairs he organised and documenta:

There was a very big gap between the rhetorics… a lot of the departments were all white. When I first went to the press department, I think everyone was white apart from one [person]… I thought this group will have no connection with the Arab Muslim community who live in the neighbourhood at all, and my work wouldn’t be able to communicate with them… I went to the mosques, I met some of the people there… none of them cared about documenta, even though they lived in that city all that time. And it’s all around ruruHaus. It wasn’t like [that] at the zine fairs. I had a mission with zine fairs to make them more participatory and have that migrant connection with the neighbourhood, which I think I did with my festival DIY Cultures for over five years. So, the zine scene is no longer the same anymore. It’s not a white hipster thing.Footnote22

The hands-off curatorial approach of ruangrupa comes from their collaborative approach, which was appreciated by artists who were used to self-organising methods. In an interview I conducted with Ade Darmawan from ruangrupa, he tells me that this way of working did not resonate with documenta as an institution:

I think in the beginning, [during the first year] they really doubted that we can pull it off. People don’t understand how we work easily, especially if you are coming from a different working ethic and method. And [the institution] obviously is very hierarchical and structural; documenta was not really prepared for our horizontal way or mode of working. For us collaboration and collective decision-making is more important. We usually have a meeting for half a day and sometimes without [making] any decision. The meeting is when we listen to others and then we decide together. But for them, a meeting is when they want to listen [to] our orders. We don’t work like that. It needs trust and time in a process. It’s really hard to work in an environment where trust is not part of the working ethic… Not only speaking, but also listening, and sharing and then getting together and then deciding together. But [there is a] condescending tone of course here and there, because ruangrupa is not a curator in the traditional sense with curatorial muscle that is very centred, our approach was many times misread as slow, undecisive, or even vague… One can see it as a curatorial method as well, but for us, it is just us being us, being ruangrupa. It’s how we as an organism live and survive.Footnote26

Nino maintains that these tensions were there from the outset:

Even while it was happening, I was aware of this paradoxical situation that you have this ethos of self-organisation and also some of the structures of self-organisation, but then it clashes to some extent with the… institutional culture of this, like very wide, very hierarchical institutional body that’s already there… I think my analysis of it was, like, constantly going back and forth between feeling like I’m in this like neoliberal nightmare and then moments where it felt like some sort of, like, self-organised dreamboat fantasy has come true… I think those of us who were closer to the whole organisational part of it maybe felt this cognitive dissonance more. I think some people who were just invited into it through second or third partners or something just showed up in Kassel and had a great time. And then the closer you were to contradictions in the centre of it, the less easy it was to just embrace this hanging out spirit.Footnote27

The Funding Question

The discrepancy between the DIY, self-organising, self-publishing, collective ethos of the lumbung and the institutional culture of documenta gGmbH becomes more apparent in how the labour of artists is valued and how funds are allocated. Prior to 2017, documenta did not pay a fee to participating artists, instead using a ‘working for the exposure’ model. Thanks to ruangrupa’s efforts, artists were given fees in the form of the seed money, a substantial production budget, and a collective pot of up to €220,000 for each mini majelis.Footnote28 However, the seed money, which essentially paid for the artist’s labour, was still low considering the amount of work required, expected, or in some cases, self-imposed, depending on who you talk to. Hamja Ahsan says that the €5000 fee was not sufficient, because for him it sometimes became ‘a 7-day a week job, and it was full time’.Footnote29

However, ruangrupa’s initial thoughts about the funding model were even more radical in the context of the contemporary art industry’s funding models for artists. Ade Darmawan says that initially they considered and discussed the possibility of paying all artists a basic income, but the differences in basic income rates in different countries stopped them. Paying each artist the same amount of seed money and production budget became an equalising factor.Footnote30 He adds,

You know, [documenta] trades their myths with your income or fees… But it doesn’t work like that. I think people know it doesn’t work like that. I think the institution knows it doesn’t work. This is what is really disgusting about the art world. The weakest position of the whole thing [is] the artist’s. If we think [of the] art world as a big ecosystem, I would say it’s a crime. It’s really exploitative.Footnote31

Most artists I spoke to agree that paying for their own labour rarely factored into their production budget, and in most cases, they ended up paying people who worked on the production of their works more than the seed money they received. Alexander Supartono says,

We don’t calculate the labour at all, actually. Yeah, it is essentially free labour. What we get is like a per diem [in Kassel]… So, we get some kind of seed money… I think that’s the only money that we distribute among the collective as an honorarium.Footnote32

Most of Taring Padi’s production budget was spent on transporting existing works from Indonesia to Germany and installing them. They also paid some of their members—at Indonesian minimum wage rates—to make new works for documenta. An interesting detail Alexander told me about was that the cost of first covering and later dismantling The People’s Justice, as demanded by documenta gGmbH shareholders and the City of Kassel, was also taken from their budget. Alexander jokes, ‘so we pay from our pocket basically to censor ourselves’.Footnote33

One of ruangrupa’s goals in bringing documenta along for lumbung was to create financial and practical sustainability for the collectives and artists beyond documenta. Through establishing marketplaces outside of documenta, like the lumbung Kios and lumbung Gallery, which sold merchandise and art by the participants, they attempted to create ongoing income for the lumbung members. Their vision of long-term benefits for the artists, then, was more materially sound compared to documenta’s tradition of expecting the participating artists’ stars to rise as a result of exhibiting at the quinquennial.

What was unexpected, perhaps, was the amount of unpaid affective and emotional labour it would take to be part of documenta fifteen. For the collective of collectives, with solidarity and anticapitalist motivations in mind—but having gone beyond the envisioned ‘small-to-medium scale’ that would bring more agility—the unpaid care work took its toll, as multiple crises erupted and artists had to convene long meetings on Zoom to make decisions collectively. Nino Bulling recalls:

Honestly, like, everyone that I was in touch with really put so much labour into this aspect of, you know, self-organisation of the artists and, like, all of these statements that we wrote and this poster campaign that we did and we were basically like working full time for this shit for like two months or so and, like, everyone of us was completely burned out.Footnote34

As one of the largest exhibitions on the contemporary art calendar, documenta is credited as creating the concept of ‘star curators’ who shape the global contemporary art world with their curatorial practice as a singular vision.Footnote37 In a sense, ruangrupa’s curatorial proposal was a counteraction against this type of self-enterprising, individualist, market-driven framework. ruangrupa’s collective approach is that art and life are inseparable.Footnote38 Their critique of an elitist contemporary art world is manifest in their motto, ‘make friends not art’. They also brought to documenta fifteen the Indonesian concept of nongkrong (hanging out), encouraging artists and visitors to ‘hang out’ as friends. This approach blurs the lines between art, life, friendship, work and leisure even further. However, it also raises the question: in the context of a neoliberal art institution, how do we exercise friendship as a form of (paid) labour? In other words, how do we quantify, commodify and remunerate friendship? And when the work that is commissioned is, or involves, ‘hanging out’, where does labour end and leisure begin? While there is a great deal of resistance from the artistic direction and artists to the idea of being co-opted by the capital, creative labour tends to not always be easily quantifiable by the artists themselves, as leisure and labour might become indistinguishable. This, in turn, is used to exploit and impoverish creative workers by neoliberal institutions. Exercising friendship and ‘hanging out’ as art blurs the boundaries of labour and leisure even further.

I asked Ade Darmawan about his view on the above questions. He replied:

In lumbung principle it is a mutual cooperation (gotong-royong in Bahasa Indonesia), the labour and the leisure are intertwined and reciprocal rather than disconnected or separated in a binary position. Time and space are bent or merged leaving slowly the defined categories. That’s the most challenging [thing] in our neoliberal (art) world.

We’ve discussed that as well after documenta in Gudskul. Because we did that as well in Gudskul context and we got paid for our time based on the project… How to get fees? Because… what is working, you know, like, if we are at home and thinking about Gudskul? In Gudskul as it is a much smaller community, many more non-financial, non-monetary exchanges are involved, such as time, space, care, ideas, knowledge, etc. In the documenta context, we questioned that as well in the process, from the idea of the basic income to equalising the fees—we call it seed money—with the logic of giving respect to artists’/collectives’ time and energy for what they have done, are doing and will do in the future for their sustainability. And this amount of resources were not burdened by production obligation, as we don’t use the logic of commission that is bilateral only between the organisers and the artists. Can this resource allocation be collectively governed or be lumbungised? So instead, we equalised the seed money and also the production money and the collective pot resources that were self-organised by each mini majelis of artists.

documenta can be supertoxic; it really changed people. Some artists will think differently. Collectives question themselves. Maybe [they] split up during the process because it’s really changed the whole dynamic. I think not only [because of] money, but documenta as a myth. I was even worried about ruangrupa. I remember during the interview during the selection one of the jury members asks, like, what [do we] fear the most. Farid [Rakun, ruangrupa member] answered what we were afraid of the most was actually if we got split up, but fortunately not. Because we know we are going to be in the belly of the beast, right?… like, lumbung way, of course we knew it’s not easy to be applied. That’s why we changed the whole scenery in Kassel… Like everyone hanging out and then time and space will bend by itself, you know. Because it’s become an organism rather than a clinically defined time and space. How to replace representation with translation and occupation? The space could be occupied with that energy with people… [the] only way is actually living there. That’s why we change the space into living space as well… It’s a living room. It’s not the exhibition space. There’s recognisable artwork but, but it’s not artwork like in [an] elitist, kind of divine space.Footnote39

At this juncture, it is important to keep in mind that ruangrupa is among many collectives that emerged in Indonesia after 1998, after the dissolution of the ‘New Order’ regime and the relative easing of restrictions on art. Collectives often run their own spaces and/or organise their own events. According to Hujatnika and Zainsjah, the move towards collective art practices in Indonesia was due to the lack of opportunities for young artists in commercial galleries, and a desire to avoid the bureaucracy of public art institutions.Footnote40 Since their foundation in Jakarta in 2000, ruangrupa have been involved in many projects and curatorial work both in Indonesia (such as the Jakarta Biennale) and overseas, which has helped sustain their collective practices financially.

Having organised zine fairs with the Other Worlds collective in Sydney for a decade and been part of the artist-run collectives Comic Art Workshop and Refugee Art Project more recently, I have not been a stranger to sustaining and being sustained by my communities, which ‘bend time and space’. In these contexts, my organisational labour has always been provided for free, as a volunteer. However, organisations like ours are not-for-profit and exist for the love of art and community. How do community art practices translate into the institutional context of an art exhibition with a €40 million budget, which has ‘touristic and money-making’ goals for the region in addition to its cultural benefits? In essence, regardless of the increase in cultural capital and greater exposure they gain through exhibiting at documenta, artists were positioned as precarious workers with low wages, who reported providing unpaid work for their employer in some instances. They have had to organise to defend their rights with no union structure or support. This, of course, is a wider issue in the contemporary art world and other cultural industries, and not specific to documenta or Germany.Footnote41

However, there is a specific history in Germany that sheds some light on the experiences of documenta fifteen artists providing their labour as migrant workers from the global south. In the next two sections, I provide some historical context from Turkish guestworker and diasporic artmaking histories. In doing so, I explore the parallels between the histories of migrant workers and migrant artists in Germany.

Ich bin ein gastkunstarbeiter: documenta fifteen in the historical context of the guest worker experience

Es wurden arbeiter gerufen,

doch es kamen menschen an

—Cem Karaca

Cem Karaca was one of Turkish rock music’s most politically radical singers, having produced several anthems to the working class and the socialist cause through his career, which lasted from the mid-1960s until his death in the early 2000s. Karaca had to spend the 1980s in exile in Germany in the aftermath of 12 September 1980 military coup in Turkey. There, Karaca continued to record songs with social themes, including commentary on the status of Turkish Gastarbeiter (guestworkers). His 1984 album, Die Kanaken, stands as a landmark artistic statement among other musical outputs from Turkey’s diasporas as a work against racist attitudes towards migrant workers, sung by Karaca in German (with a thick Turkish accent, and occasional Turkish exclamations, such as ‘aman aman’).

Before my visit to Kassel for the opening of documenta fifteen, during my time there and after my return to Australia, I often listened to these songs and reflected on their resonance with the experience of artists from the global south in Germany. Die Kanaken is a concept album about the Gastarbeiter experience, containing songs from a musical play, Ab in den Orient Express (Off you go to the Orient Express), written by Harry Böseke and Martin Burkert in 1984. The play takes its title from a well-known racist slogan, which demanded foreigners leave the country by taking the Orient Express train. The title of the record is a reclamation use of the German racist slur Kanake, pejoratively used against migrants from the SWANA (Southwest Asia and North Africa) regions.

As a migrant artist, I see Cem Karaca’s great influence on me. My band Hazeen’s music and performances, and our debut album Sovereign Murders, which was released with documenta’s support, place anti-racism and anti-Islamophobia at its core. Like Karaca, we take a Western musical genre (in our case, death metal) and synthesise it with musical traditions of our cultures from India, Iran, and Turkey, incorporating Sufi elements and middle eastern rhythms. One of the main themes of Sovereign Murders is the critique of Australia’s treatment of refugees and asylum seekers. Our main contributor in these projects was Kurdish-Iranian heavy metal guitarist Kazem Kazemi, whom we met through social media. He had been in indefinite offshore detention on Manus Island since 2015 and was posting videos of himself playing electric guitar in the laundry space in the camp, under the social media handle @manus_metal_man. He collaborated with Safdar to write a song, for which he also provided lyrics. This became the track ‘Manus Hell’ on Sovereign Murders. Kazem was able to join us in Sydney, thanks to the funding from documenta, and record guitars and vocals on this song and also contribute to other tracks.

The song on Die Kanaken that I find most reminiscent of ‘Manus Hell’ is ‘Es kamen menschen an’, which is about being dehumanised by host countries where migrants or refugees have sought a new life. ‘Es kamen menschen an’ became a personal soundtrack for me throughout documenta fifteen. Its lyrics are a reference to a Max Frisch quote from 1965: ‘workers were called, but humans came’, which was a response to the situation of migrant workers in Switzerland.Footnote42 The reason the song kept playing in my head was due to the tension we experienced in Germany as we tried to exercise our freedom of expression. The lived experiences of artists from the global south participating in the ‘first exhibition of the twenty-first century’ has some parallels with the guestworker experience in Germany in the twentieth century.Footnote43 After World War II, Germany went through a speedy economic recovery known as ‘the economic miracle’, or Wirtschaftswunder. As a result, a labour shortage emerged during the 1950s and ‘60s, and authorities started signing recruitment agreements with several countries in order to import guest workers. The first of these agreements was signed with Italy in 1955, the same year Arnold Bode founded documenta to grapple with the Nazi regime’s legacy of censorship and destruction of modern art and to provide a venue to restore Germany’s place in the world of modern art through a survey exhibition. These two simultaneous but discrete initiatives form intricate rhizomatic trails that intersect at the point of documenta fifteen.

Germany’s attempts to meet labour shortages continued into the 1960s and 1970s, resulting in recruitment agreements to bring temporary workers from southern Italy, Yugoslavia, Greece, Turkey, Portugal, and Spain. While the expectation was for these workers to stay only for a year or two, more and more guestworkers began to settle and bring their families with them. By the 1980s, xenophobic sentiments against the migrant population of some 4.5 million people escalated to breaking point. The 1980 elections were marked by the far right National-demokratische Partei Deutschland (NPD)’s anti-foreigner slogans, such as ‘Germany for Germans’.Footnote44 Writing in that period, Philip L. Martin regards Germany’s economic experiment with guest workers as a mistake, because they eventually cost taxpayers more—due to the integration initiatives—than they benefited the economy.Footnote45 On the topic of integration, Martin notes, ‘the 1.4 million Turks are a special problem. Their Islamic religion and relative poverty alienate them from German society’.Footnote46

While the cost-benefit analysis of the guestworker experience continued, the integrationist policies extended to arts and culture. Barbara Wolbert lists a series of exhibitions that were held during the 1980s, with titles such as ‘I Live in Germany: Seven Turkish Artists in Berlin’ and ‘Train Station Everywhere: Painting and Sculpture by Turkish Artists in Berlin’, which were presented as art by Turkish guestworkers, and celebrated mostly by political activists in support of migrant workers rather than the art world in general.Footnote47 This was met with critique from Turkish-German composer Tayfun Erdem, who labelled this the Türkenbonus—artists being provided a platform for their cultural identity as migrant Turks in Germany.Footnote48

Wolbert continues her ethnographic analyses of German art exhibitions that deal with the subject of ‘the other’ with a discussion of Begegnung mit den Anderen (Encountering the Other), a 1992 exhibition featuring works by artists from Asia, Africa, and South America. Referred to in the media as the ‘Third World Documenta’, the show intended to draw attention to the Eurocentric focus of documenta by foregrounding the works of artists from the global south, but was nevertheless ‘paternalistic’, and was ‘exoticising’ the art in its curatorial choices.Footnote49

There is a long history of orientalist attitudes towards art and craft from the global south in the West, which have often been contextualised by white/Western curatorial perspectives. The appointment of ruangrupa was a way of ‘decolonising’ the art mega-exhibition, centring a curatorial framework from the global south for an edition of documenta that would feature works by collectives and artists from that region, giving the German public an opportunity to ‘encounter the other’ on the terms of ‘the other’.

The anti-Semitism controversy coloured everything the artists did in the context of documenta fifteen. The multitudes of subjectivities, political stances, and creative practices were drowned in the noise. A ‘scientific panel’ appointed to scrutinise the artworks to find evidence of antisemitism came to the conclusion that ‘the serious problems of documenta fifteen consist not only in the presentation of isolated works with anti-Semitic imagery and statements, but also in a curatorial and organisational structural environment that allowed an anti-Zionist, anti-Semitic, and anti-Israel sentiment’.Footnote50 The open letter co-authored and signed my many of the lumbung members and artists as a response to the scientific panel’s findings emphasises how that report conflates various broad concepts such as anti-Zionism, anti-Semitism, and anti-Israel sentiments, and opposes its portrayal of the artists and curators as one homogenous and unruly mass unaware of the complexities of Germany’s history.Footnote51

As artists and collectives from around the world, we were invited to Germany temporarily to provide our artistic and cultural labour in the framework of documenta fifteen, along with other workers who were hired on temporary contracts to work as curators, curatorial assistants, production team members, educators, art mediators, and so on. In essence, we were guest workers, or guest art workers (perhaps a neologism like gastkunstarbeiter may be appropriate), who ended up facing Islamophobia, racism, hostility, and paternalistic attitudes from politicians, the general public, and the media in Germany, much like the migrant workforce has since the 1960s. There were racist and transphobic attacks against some of the artists and the artwork prior to and during the exhibition. My colleague and friend, Hamja Ahsan, faced a great deal of media and public hostility in Germany, both towards his artworks and his statements regarding documenta, his pro-Palestine stance, and racist attitudes in Germany. He remembers the attacks against him beginning even before the start of documenta fifteen, due to his many years of pro-Palestine activism. Along with other artists who were associated with pro-Palestine and pro-BDS movements, he received countless negative comments and threats online both in the lead up to and during the exhibition. One of the venues where his work was exhibited, alongside Palestinian collectives Question of Funding and Eltiqa, among others, was attacked by right-wing groups, who wrote far-right graffiti on the walls. The attacks against Hamja accelerated, and he became one of the artists who was singled out, after being tagged a ‘hate artist’ (hass-kunstler) by the conservative, right-wing German newspaper, Bild, after calling the German chancellor Olaf Scholz a ‘neoliberal fascist pig’ on his private social media account.Footnote52 Hamja had organised two public programs for documenta; however, after this incident he was prevented from appearing publicly in documenta, and was not able to hold the second part of his public program in September 2022. He remembers documenta fifteen as one of the most traumatising experiences of his life:

the whole process of the documenta… when you were threatened, where there was a media hostility, political hostility, racist hostility, constantly, day in, day out, and every day you felt like you were prey, or you might have some crap press written all about you… Every single day of that was horrible and you didn’t know which images of yourself were being circulated in German social media. You don’t know what Reddit threads were about you… and yeah. This guillotine over your head, where you could have been expelled or banned or smeared… that really affected my ability to just function… I just became really dysfunctional… and the institution gave no accountability, no one to respond to… They would almost treat those distressing experiences as an invisibility. Some visible and really bad institutional problems and management problems.Footnote53

As the open letter ‘We are angry, we are sad, we are tired, we are united’—of which I was one of the signatories—proclaims:

We refuse Eurocentric—and in this case specifically Germancentric—superiority, as a form of disciplining, managing and taming. We come here as equals. We come here in power, and we come here to put ourselves in the public domain, with nothing to hide or be ashamed of. We come here as nothing less than equals, who can humbly learn from each other, who can help each other, who care about each other, because we know that our interdependency is the only path toward a more just planetary future.Footnote56

Speaking in Tongues, Making Art with An ‘Accent’

Positioning documenta fifteen artists as precarious guestworkers providing their labour on a temporary basis in Germany allows us to dig deeper into what it means to speak against the dominant culture as a working-class minority. John Berger’s description of the Turkish guest worker in Germany in The Seventh Man is one of voicelessness: someone who mimics gestures and words in a foreign country where they do not have a knowledge of the language. Who finds that the meanings of words change when they use them, because they do not know them on a metaphorical, or cultural level. This account invokes a melancholic and displaced person, who find themselves in an unheimlich—uncanny, or literally ‘unhomely’—environment.Footnote57 Drawing from Berger, Homi Bhabha argues,

Without the language that bridges the knowledge, without the objectification of social process, the Turk leads the life of a double, the automaton. It is not the struggle of master and slave, but in the mechanical reproduction of gestures, a mere imitation of life and labour.Footnote58

The guest art workers of documenta fifteen from the global south are far from the oppressed figure of the Gastarbeiter of the 1970s. Most of them speak English (and sometimes German) fluently and know it on a deep metaphorical and cultural level. In postcolonial theory terms—often coming from places with colonial histories—they resist subalternity. They disrupt the hegemony of the local language by bringing words from their own language into their art works, their statements, and everyday communications. The most apparent of these disruptions come from ruangrupa, who introduced Indonesian words, such as lumbung (rice barn), nongkrong (hanging out), majelis (assembly) and sobat (friend) into the daily lexicon within the framework of documenta fifteen. But it is not limited to that. As a humorous example: artist and curatorial assistant Cem A. distributed tattoo stickers that said ‘documenta fifteen mashallah’ (in Arabic: ‘God has willed it’) and ‘documenta sixteen inshallah’ (in Arabic: ‘if God wills it’) in the early days of the exhibition when the antisemitism controversy was unfolding.

In the context of an art exhibition the size of documenta fifteen, polyphony and multilingualism are not surprising or necessarily significant in themselves; however, it is not a far-fetched idea to think of the diverse practices of artists in linguistic terms as foreign art ‘languages’. Indeed, ruangrupa’s call to the artists to ‘translate’ what they do to Kassel affirms this line of thinking. What is foreign to the Western art settings must be expressed in a way that locals would be able to make sense of. In documenta fifteen, some things seemed to get lost in translation. An ongoing inside joke in documenta fifteen was the question ‘where is the art?’, highlighting the often intangible, process-based, community-driven, relational, collective, and artistic practices that clashed with the expectations of documenta as an institution.Footnote59 Some of the media responses to documenta fifteen also brought this question to the fore. For instance, the 3Sat documentary Kaminer Inside: documenta fifteen, featuring the Russian-born media personality Wladimir Kaminer, goes in search of this elusive concept of art. Filmmaker Alia Ardon from our ekosistem and I were interviewed by Kaminer and were featured in the documentary, talking about our work, Border Farce – Sovereign Murders – Alien Citizen. We were asked whether our activism could be seen as art. In the final edit, we see Kaminer walking away from our exhibition space in Stadtmuseum, not totally convinced by our response. In another gallery space, he looks around with feigned perplexity and calls out ‘Art, where are you?’Footnote60

Making Friends (Not Art) as Work

As important as it is to critique how artistic labour is valued in exhibitions such as documenta fifteen, and more broadly in the contemporary art world, it is even more essential to examine and shed light on the working conditions of waged workers employed by art institutions such as documenta gGmbH to support, organise, and administer such a large event. In essence, these are employees who were paid almost minimum wage, and in many cases casual hourly rates to help bring the vision of the lumbung to life.

For instance, sobat-sobat were art mediators employed to help visitors explore documenta fifteen. On 18 August 2022, about halfway into the exhibition, they published an open letter (which was later included in their 80-page publication through lumbung Press, titled Ever been Friend-zoned by an Institution?), documenting their negative working conditions as employees of documenta und Museum Fridericianum gGmbH. Their main points include high levels of stress and the devaluation of their roles, not being paid for their time for the ongoing preparation and research they had to undertake as part of an everchanging exhibition, lack of resource planning on the part of the institution in pandemic conditions, dysfunctional workflows and systems, not having access to work devices, data breaches, and ‘intimidating and violent communication by staff members’.Footnote61

The main point in their criticism is that documenta as an institution did not take the time to engage in the values of friendship, care, and community exchange that ruangrupa hoped to bring to this edition of documenta:

To this day, the executive department of documenta gGmbH has not put ruangrupa’s proposal for documenta fifteen into practice. The documenta gGmbH contracted us as service providers and expects us to act accordingly. At the same time, we are asked to practise art mediation as sobat-sobat—as friends. These two approaches are constantly clashing. As a result, a statement on art education in accordance with lumbung values was never formulated.Footnote62

During my time in Kassel prior to the opening and during the first week of the exhibition, I observed many documenta staff members in ruruHaus looking stressed and overworked. There were several mishaps and staff were struggling to meet the competing demands of the organisation, often working late and looking exhausted. Curatorial assistant Gözde Filinta, who worked with us on our project, says the expectations of the artistic direction and the artistic team from the curatorial assistants were ‘vague’. Curatorial assistants did not know what their role was, which changed from situation to situation, artist to artist. In some cases, they were given more responsibility and authority, while in others they felt less empowered. She says that the artistic team rarely had time to meet with curatorial assistants alone, aside from weekly large meetings with the documenta team, and there were few opportunities for meeting with all fourteen curators, including ruangrupa, present at the same time. They had one big meeting at the beginning where they learned about lumbung and its principles, but her understanding of the curatorial goals remained unclear. She also felt that the sense of solidarity that comes with the lumbung did not extend to herself as a curatorial assistant. As a result of working at documenta fifteen, she felt burned out.Footnote64

Gözde informs me that curatorial assistants at documenta fifteen were paid slightly above minimum wage in Germany. They later requested a pay increase and received a €100 per month increase (before tax). Some of them, including Gözde, moved to Kassel for the duration of their employment by documenta gGmbH, which is also a cost they had to bear. As with the artists, many staff members see working at documenta as a big career break and accept exploitative working conditions due to expectations that the experience would lead to better positions in the future, Gözde tells me. Most curatorial assistants are in their early thirties, working with minimum wage and undertaking highly intellectual labour. According to Gözde, these conditions are endemic in the sector and makes her question her career choices and the value of the work she provides.Footnote65

The experiences of sobat-sobat and the curatorial assistants, as Gözde describes them, are textbook examples of ‘immaterial labour’ in a post-industrial economy, in which ‘the worker’s soul [becomes] part of the factory’.Footnote66 As Maurizio Lazzarato argues, ‘precariousness, hyperexploitation, mobility, and hierarchy are the most obvious characteristics of metropolitan immaterial labor’.Footnote67 Companies create small teams for ‘ad hoc projects’, which are only in operation when the task is needed and become disestablished when the project is finished.Footnote68 As Gözde informs me, sobat-sobat were only employed shortly (one or two months) before the exhibition opening and were expected to learn a large amount of information to be able to perform their tasks. She says that the staff (except the artistic team) were treated like ‘seasonal workers’, which meant that there was no culture building among them; they were hired when the institution needed teams to perform a certain function and their contracts ended as soon as, or soon after the exhibition concluded.

Ade Darmawan also highlights the same issue of not having an ongoing institutional culture or memory:

documenta is actually not a big institution… Every artistic director brings their own team every time, so it always starts from scratch. It’s good and bad. It’s good because it will leave some space for the artistic direction to build the team but again the time and openness factor is not always there, and it’s bad because there is not much institutional memory or knowledge that can be regenerated… so there are no organic growing cycles. So, it’s like a frozen institution that lives in the mind.Footnote69

The production staff was just so overwhelmed at some point and so understaffed and so sick and tired… It was just starting to feel like I would force people to, you know, like, do things that they’re really not able to do anymore because they just fucking need a break. And I think, like, everyone that worked with me on my project at one point or another, like, just broke down crying… I don’t know if that’s always the case in mega arts events, because this was my first mega art event… I really didn’t like it. It was really not nice to be forced to ask labour off of someone who’s clearly not in a position to do it and be well, yeah. And then I think to some extent, I also felt like ruangrupa hadn’t maybe really considered this split enough… that in some ways, the existence of the lumbung relied on this overtime wage labour of the staff that was employed. I don’t know, or at least I haven’t heard it mentioned… I felt like that was like a pretty blatant problem.Footnote70

Conclusion

documenta fifteen closed on 25 September 2022, and messages of celebration were posted on the lumbung WhatsApp group, as the collective of collectives managed to stand their ground against a hostile political, academic, and media-driven campaign, and the exhibition was not shut down. The position of documenta gGmbH towards the artistic direction and the artists, both throughout the controversies and in the time since the closing, has been ambivalent. On the one hand, they seemed to want to champion the radical and revolutionary aspects of documenta fifteen; on the other, they did not want to be associated with the pro-Palestinian positions of the lumbung community in any way.

Since documenta 14 had a budget shortfall of €7.6 million, it was important for documenta gGmbH and its shareholders to ensure they did not go over budget in the event’s fifteenth edition.Footnote71 The day after the closing day, documenta posted an update on their website, titled ‘documenta fifteen closes with very good attendance figures’. A total of 738,000 people visited the exhibition, which exceeded the organisers’ expectations, and despite the controversies, ‘the majority of the visitors rated their visit to documenta fifteen as good to very good [57.4%]’.Footnote72 In June 2023, documenta gGmbH announced that their financial statement was in the black. Acting Managing Director Andreas Hoffman said ‘I am very pleased that we can now close the major exhibition, which was prepared during the pandemic and marked by the crisis surrounding the anti-Semitic motifs, in the black. I would like to take this as an opportunity to thank my predecessors and the team for prudent financial management and controlling’.Footnote73

However, documenta continue to be on high alert to avoid further anti-Semitism accusations against them. On 9 October 2023, Andreas Hoffman published a press release condemning two ruangrupa members who ‘liked a video showing people chanting “viva Palestine” as well as “Palestine will be free”’ in the aftermath of the Hamas attack on Israel.Footnote74 Calling the social media likes ‘intolerable and unacceptable’, he wrote, ‘documenta und Museum Fridericianum gGmbH distances itself from this in the strongest possible terms. It notes that the likes have since been withdrawn and that those involved acknowledge them as a mistake’.Footnote75 This shows that, while no longer employed as the artistic direction of documenta fifteen, members of ruangrupa are still policed as workers of documenta gGmbH. It is not hard to see that the institution will engage in damage control and ensure the brand’s image is secure in the lead up to the next edition of the quinquennial in 2027.

Returning to my earlier questions: how do we exercise friendship as a form of (paid) labour? How do we quantify, commodify, and remunerate friendship? When does the work of ‘hanging out’ end as labour and begin as leisure? How do community art practices translate into the institutional context of the global contemporary art exhibition? The documenta fifteen experience showed that the highly hierarchical structures of a mega art institution and its political and financial imperatives are difficult, if not impossible, to reconcile with the horizontal structures and not-for-profit ethics of many community art organisations and collectives. As Ade Darmawan observes, this sometimes created a toxic environment and resulted in break-ups among some collectives, everyone wanting a piece of the documenta pie. From the outset, ruangrupa envisaged documenta fifteen as ‘lumbung one’, planning for the sustainability of the collective of collectives. Following documenta—freed from the shackles of institutional hierarchy and demands of the market forces, as well as the formalities of predetermined mini majelises formed by the curators—artists have been collaborating around the world based on friendships and connections forged in Kassel and online. In that respect, ruangrupa’s vision for the lumbung as non-hierarchical, small-to-medium (never too big!) scale networks has been achieved. Finally, we are free to be friends and nongkrong without needing to commodify our art.

A Post-Script: imece as an Alternative to Lumbung

Here is a playful suggestion for anyone who is listening. The community rice barn as a metaphor works only to some extent. Lumbung is an architectural structure where surplus common resources are stored for the common good. I offer the Turkish word imece as an alternative, which is a term used to describe village folk working collectively for the common good or to help each other—harvesting together, preparing food for winter, building what needs to be built without waiting for the municipality to do it. In some ways, it is no different to what villagers in Indonesia call gotong royong (mutual assistance).

İmece is solidarity in action, not solidarity as a place.

İmece, by definition, is:

Non-hierarchical

Non-institutional

Collectively organised

By the people for the people

Putting together an art show in imece style, we discard all titles that create hierarchies. There is no artistic direction, and there are no curators.

The institution strips from its institutionality. Its managing directors, administrators, coordinators, and shareholders give up their powers and enter an equal standing with the artists, production teams, education teams, and others involved in the show.

The roles of each person are interchangeable—there is total fluidity among the participants. Each undertakes work as needed according to their abilities.

All resources are shared equally. The budget is divided among every participant equally regardless of the type of work they perform. Their time is equally valuable, and they receive equal compensation.

Community is essential, friendship is optional.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 The Documenta Scandal, dir. Grete Götze (Deutsche Welle, 2022), 28:25, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A9uhf1iSvN8.

2 ruangrupa, ‘documenta fifteen’, ruangrupa.id, https://ruangrupa.id/en/documenta-fifteen/.

3 Indonesian for ‘ecosystem’. On the documenta fifteen website, ekosistem is defined as ‘collaborative network structures through which knowledge, resources, ideas, and programs are shared and linked’. Ekosistem is a key component of ruangrupa’s practice as a collective, as exemplified by the Gudang Sarinah Ekosistem, an interdisciplinary space, which brought together a number of collectives in Jakarta, as well as Gudskul Collective Study and Contemporary Art Ecosystem, started by ruangrupa, Serrum and Grafis Huru Hara. In essence, ekosistem is the broader local networks in which artists and collectives work and create together and provide each other space and opportunities.

4 Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005 [1987]), 21.

5 ruangrupa and Artistic Team documenta fifteen, documenta fifteen Handbook (Berlin: Hatje Kantz, 2022), 40.

6 Kate Brown, ‘Documenta 15 Opens With a Record 1,500 Artists, Promising to Be Unlike Any Edition That Came Before It’, Artnet, June 15, 2022, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/documenta-15-preview-2130857.

7 Sobat is the Indonesian word for friend. Sobat-sobat is the plural form. In the documenta fifteen context, sobat-sobat were staff who provided guided tours and art mediation to visitors as ‘friends’.

8 Can Yalçinkaya and Safdar Ahmed, ‘Creeping Sharia: An Extreme Response to Islamophobia’, in Australian Metal Music: Identities, Scenes, and Cultures, ed. Catherine Hoad (Bingley: Emerald Publishing, 2019), 111–127.

9 Safdar Ahmed, Still Alive: Notes from Australia’s Immigration Detention Centre (Melbourne: Twelve Panels Press, 2021).

10 Safdar Ahmed, ‘documenta fifteen’, safdarshmed.com, https://safdarahmed.com/documenta-fifteen/.

11 Safdar Ahmed, personal correspondence with the author, September 7, 2023.

12 Samanth Subramanian, ‘A Radical Collective Takes Over One of the World’s Biggest Art Shows’, New York Times Magazine, June 9, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/09/magazine/ruangrupa-documenta.html.

13 ruangrupa, ‘About the Lumbung Processes and How the Guest Becomes the Host’, documenta fifteen Handbook (Berlin: Hatje Kantz, 2022), 12.

14 ruangrupa, ‘Keep on Doing What You’re Doing…’, documenta fifteen Handbook (Berlin: Hatje Kantz, 2022), 30.

15 Gözde Filinta, interviewed by the author, September 19, 2023 (author’s translation from Turkish).

16 Nino Bulling, interviewed by the author, October 14, 2023.

17 Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000).

18 Michael Hardt, ‘Affective Labor’, boundary 2 26, no. 2 (1999): 89–100, https://www.jstor.org/stable/303793.

19 ruangrupa, ‘Keep on Doing What You’re Doing…’, documenta fifteen Handbook (Berlin: Hatje Kantz, 2022), 21.

20 Bulling, interview, October 14, 2023.

21 Alexander Supartono, interviewed by the author, September 7, 2023.

22 Hamja Ahsan, interviewed by the author, September 7, 2023. ruruHaus was the headquarters of documenta fifteen, designed as the ‘living room’ of the exhibition.

23 Supartono, interview, September 7, 2023.

24 Safdar Ahmed, interviewed by the author, October 9, 2023.

25 Bulling, interview, October 14, 2023.

26 Ade Darmawan, interviewed by the author, November 16, 2023.

27 Bulling, interview, October 14, 2023.

28 Subramanian, ‘A Radical Collective Takes Over One of the World’s Biggest Art Shows’.

29 Ahsan, interview, September 7, 2023.

30 Darmawan, interview, November 16, 2023.

31 Ibid.

32 Supartono, interview, September 7, 2023.

33 Ibid.

34 Bulling, interview, October 14, 2023.

35 Sarah Brouillette, ‘Creative Labor’, Mediations: Journal of the Marxist Literary Group 24, no. 2 (2009), https://mediationsjournal.org/articles/creative-labor.

36 Ibid.

37 Charles Green and Anthony Gardner, Biennials, Triennials, and documenta: The Exhibitions that Created Contemporary Art (West Sussex: Wiley, 2016), 20–21.

38 ruangrupa and Nikos Papastergiadis, ‘Living Lumbung: The Shared Spaces of Art and Life’, e-flux Journal 118 (2021), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/118/395154/living-lumbung-the-shared-spaces-of-art-and-life/.

39 Darmawan, interview, November 16, 2023.

40 Agung Hujatnika and Almira Belinda Zainsjah, ‘Artist Collectives in the Post-1998 Indonesia: Resurgence, or a Turn (?)’, AESCIART: International Conference on Aesthetics and the Sciences of Art, 28 September 2020, 256–263, https://media.neliti.com/media/publications/338617-artist-collectives-in-the-post-1998-indo-591112ef.pdf.

41 Paula Serafini and Mark Banks, ‘Living Precarious Lives? Time and Temporality in Visual Arts Careers’, Culture Unbound 12, no. 2 (2020): 351–372, doi: 10.3384/cu.2000.1525.20200504a.

42 Laura Muchowiecka, ‘The End of Multiculturalism? Immigration and Integration in Germany and the United Kingdom’, Inquiries 5, no. 6 (2013): 3, http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/735/3/the-end-of-multiculturalism-immigration-and-integration-in-germany-and-the-united-kingdom

43 Charles Esche, ‘Charles Esche about documenta 15’, Museum of Care, https://museum.care/charles-esche-about-documenta-15/.

44 Philip L. Martin, ‘Germany’s Guest Workers’, Challenge 24, no. 3 (1981): 34–42, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40719975.

45 Ibid.

46 Ibid., 39.

47 Barbara Wolbert, ‘Ethnographic Shortcuts Art Exhibition and Fieldwork in the Everyday Spaces between Anthropology of Art and German Studies’, in Former Neighbors, Future Allies? German Studies and Ethnography in Dialogue, ed. A. Dana Weber (New York: Berghahn, 2023), 243.

48 Ibid., 243.

49 Ibid., 245.

50 Marion Detjen, ‘What Kind of Science Is This?: On the documenta fifteen “Expert Panel”’, e-flux Notes, September 23, 2022, https://www.e-flux.com/notes/492996/what-kind-of-science-is-this-on-the-documenta-fifteen-expert-panel.

51 Lumbung community, ‘We are angry, we are sad, we are tired, we are united: Letter from lumbung community’, e-flux Notes, September 10, 2022, https://www.e-flux.com/notes/489580/we-are-angry-we-are-sad-we-are-tired-we-are-united-letter-from-lumbung-community.

52 Oskar Luis Bender, ‘Rauswurf! Hass-Künstler darf nicht mehr auf die Documenta.

… aber seine Werke bleiben’, Bild, August 20, 2022, https://www.bild.de/politik/inland/politik-inland/documenta-hass-kuenstler-rausgeworfen-81063694.bild.html.

53 Ahsan, interview, September 7, 2023.

54 Minh Nguyen, ‘Friendship and Antagonism: Documenta 15’, Art in America, August 2, 2022, https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/aia-reviews/documenta-15-review-lumbung-ruangrupa-1234635632/.

55 Frank-Walter Steinmeier, ‘Opening of documenta fifteen’, Der Bundespräsident, https://www.bundespraesident.de/SharedDocs/Reden/EN/Frank-Walter-Steinmeier/Reden/2022/220618-documenta-fifteen.html.

56 Lumbung community, ‘We are angry, we are sad, we are tired, we are united’.

57 John Berger and Jean Mohr, A Seventh Man, (London and New York: Verso, 2010), 95-98.

58 Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), 165–166.

59 Claudia König, ‘Awaiting ruangrupa: A Performative Walk through Kassel’, Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia 6, no. 1 (2022): 211–220, https://doi.org/10.1353/sen.2022.0012.

60 Kaminer Inside: documenta fifteen, dir. Nadja Kölling (3Sat, 2022), 45:00.

61 Alice Escher, Anna Marckwald, Antonin Steinke, Barbara Lutz et al., Ever Been Friend-zoned by an Institution? (Kassel: Sobat Publication, 2022).

62 Ibid., 4.

63 Kabir Jhala, ‘Documenta Drama: The Six Most Controversial (and Confusing) Things we Saw at the Kassel Exhibition’, The Art Newspaper, June 21, 2022, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/06/21/documenta-15-most-controversial-kassel-exhibition.

64 Filinta, interview, 19 September 2023. I asked Ade Darmawan for a comment about Gözde’s experience. He said that they met with the curatorial assistants more than once, but ‘it was always difficult to gather the whole team because of the pandemic at that time, so we went in rotation. I remember once we needed to have a sharing session with the whole team… people who experienced many documentas before said that never happened before, that the whole team could share their thoughts and feelings. This happened before the opening… and about the so-called assistant curators: we don’t like this term, as we see them as a collaborator as well… especially people with the expectation or experience of “traditional curating” ‘will struggle in our lumbung model’. Ade Darmawan, email correspondence with author, February 16, 2024.

65 Filinta, interview, September 19, 2023.

66 Maurizio Lazzato, ‘Immaterial Labor’, in Radical Thought in Italy, ed. Paolo Virno and Michael Hardt (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 134.

67 Ibid, 136.

68 Ibid.

69 Darmawan, interview, November 16, 2023.

70 Bulling, interview, October 14, 2023.

71 Henri Neuendorf, ‘“The Ship Is Now Back on Course”: documenta Boosts Its Budget After a New Report Shows It Overspent Even More Than Previously Thought’, Artnet, November 30, 2018, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/documenta-final-audit-even-more-over-budget-than-previously-thought-1407136.

72 documenta, ‘Documenta Fifteen Closes with Very Good Attendance Figures’, documenta fifteen, https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/news/documenta-fifteen-closes-with-very-good-attendance-figures/#:∼:text=On%20exhibition%20space%20totaling%20more,integral%20part%20of%20documenta%20fifteen

73 ‘Documenta Annual Financial Statements 2022: Documenta Fifteen Closes in the Black’, Art Dependence Magazine, June 21, 2023, https://www.artdependence.com/articles/documenta-annual-financial-statements-2022-documenta-fifteen-closes-in-the-black/

74 These were posted on the Instagram page @realdocumenta, which was started by Hamja Ahsan in July 2022, during the early days of documenta fifteen, as an artist-driven project to represent documenta fifteen and counter the accusations of anti-Semitism directed at the artists. It also served as a research archive of the history of documenta. The account was suspended on November 15, 2023 and later shut down by Instagram on the basis of infringing on documenta’s trademark.

75 Andreas Hoffman, ‘Press Release: documenta Managing Director Andreas Hoffmann on Social Media Likes by ruangrupa Members regarding the Pro-Palestinian Demonstration in Berlin last Saturday’, documenta.de, May 7, 2024, https://www.documenta.de/en/news#news/3267-press-release-documenta-managing-director-andreas-hoffmann-on-social-media-likes-by-ruangrupa-members-regarding-the-pro-palestinian-demonstration-in-berlin-last-saturday.