Abstract

Through the discourse of indigeneity, rural communities around the world are joining a global network of rural justice seekers. By articulating grievances collectively, they demand state recognition while seeking support from NGOs and international development organisations. In Indonesia, the manifestation of indigenous ‘adat’ politics is no longer confined to the national struggle for the recognition of land rights, but instead, has proliferated into many localised short term ‘adat projects’. This introduction to the TAPJA special issue on adat demonstrates that both the rural poor and local elites can be the initiators or recipients of these adat projects but, at the current juncture, the latter are better positioned to benefit from such projects. The special issue shows that in Indonesia, where adat is often firmly entrenched in the state, the promotion of indigeneity claims can work in contradictory ways. Findings from across the special issue show that adat projects tend to reinforce the power of the state, rather than challenging it.

Introduction

Since the 1990s, states from around the world have turned from authoritarian rule with closed borders to democratic systems embracing neo-liberal economic development. That general change has also evoked a parallel development in renewed attention for local culture and tradition (Assies Citation2000; Hale Citation2002; Prill-Brett Citation2007). In political terms, the collective struggle of indigenous people ‘has given rise to a new global political entity, termed “indigenism”, and an associated international debate on indigeneity’ (Birell Citation2016, 9). In Indonesia ‘adat’ has come to be the word associated with indigeneity (Moniaga Citation2007). The Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of the Archipelago (AMAN)—founded in 1999—claims that it is one of the world’s largest national movements to defend local rural communities’ rights over land and natural resources. However, adat is also a diffuse term with multiple meanings and interpretations. In a general sense, adat is the Indonesian term for indigenous customs, traditions and institutions. However, as the concept has many more connotations it is also deployed for a variety of political purposes (Henley and Davidson Citation2007; Li Citation2007).

Although some states are recently experiencing a reversal—from democracy to more authoritarian regimes—the indigenous peoples’ discourse continues to carry a powerful message. In Indonesia, two decades after Indonesia’s democratic reforms were instated, adat remains influential in national political and legal domains, and has extended further into debates about land rights and control over natural resources (Hauser-Schäublin Citation2013). National advocacy organisations promoting adat rights have made considerable achievements, especially in terms of legal reforms. ‘Adat law communities’, ‘adat forest’ and ‘adat villages’ are now legal terms designed to provide communities with rights to their collective territory, natural resources and culture. Thus, rather than a temporary resurgence in the wake of emerging political opportunities after the fall of President Soeharto, the position of adat has solidified through laws and government regulations. Therefore, one might assume that such developments have served to reduce the power of the state, empowering local communities once systematically dispossessed and pushed to the margins. As this special issue demonstrates however, adat politics in Indonesia does not automatically result in such outcomes. Indeed, in the many cases of ‘adat projects’ we reflect on herein, outcomes point to the opposite trend. More often than not, the politics of indigeneity in the form of these adat projects in Indonesia serve to privilege authority among local elites, reinforcing the power of the state.

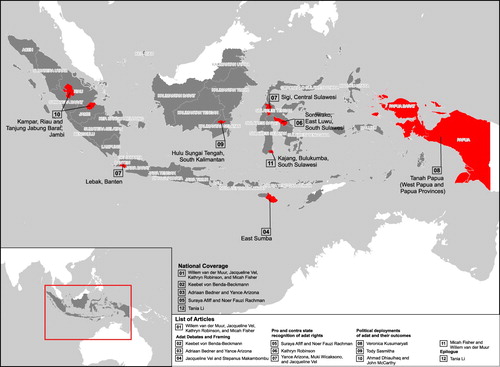

This two-part special issue came together as part of the international conference on ‘Adat law 100 years on: Towards a new interpretation’, held in May 2017 at Leiden University.Footnote1 Researchers and professionals from Indonesia and around the world gathered to consider the current prominence of adat in debates on rural governance in Indonesia.Footnote2 Based on research conducted all over Indonesia (), nearly 40 papers sought to address the following questions: How do we understand the current role of adat, and indigeneity more generally, in both civil society advocacy and government policy? Which actors invoke adat and for what purposes? Who benefits from pro-adat interventions? A main conclusion of the conference was that strategic narratives about adat are no longer dominated by civil society advocates campaigning for state recognition of adat communities and their land rights. Instead, there exists a variety of stakeholders who promote their own strategic framing of adat in specific situations. This introductory article—rooted in the various research articles comprising this special issue—will substantiate this argument and hence contributes to the discussion about the role of adat in present day Indonesia, particularly in relation to land conflicts and local politics.

Figure 1 Map showing the respective research sites for articles in the special issue ‘Changing Indigeneity Politics in Indonesia’. Map produced by Urban El-fatih Bani Adam © 2019.

The new approach to adat studies resulting from this collection of articles is that the revivalism of adat during the first decade of Reformasi has proliferated into a variety of interlinked ‘adat projects’ that should be interpreted in their specific political-economic contexts. Our selection of the word proyek (Aspinall Citation2013) in Indonesian is deliberate and holds its own connotations, which we define as funded, time-bound interventions revolving around a particular objective. We analysed the main actors in these projects, as well as their agendas and interests, the narratives they create when framing adat, and the characteristics of their political strategies. The articles across the special issue also show that there is a degree of discrepancy between national adat debates and how adat is played out in specific local situations. They demonstrate that various actors currently mobilise, interpret, codify and contest adat in multiple ways in Indonesia. The authors observe that although adat has been an effective tool to challenge corporate and state power, and continues to hold the power to do so, more recent manifestations of adat are often invoked as an asset in tourism development, a powerful tool in identity politics and elections, an argument used against and in favour of land dispossession, and a weapon against too many immigrants. While ‘adat projects’ at times may enhance the position of marginalised customary communities, this special issue alarmingly shows that adat is more commonly re-interpreted to support the interests of powerful state institutions and regional elites.

Adat Debates

A decade ago, Jamie Davidson and David Henley (Citation2007) published the edited volume The Return of Tradition in Indonesian Politics: The Revival of Adat from Colonialism to Indigenism. This book came at a time when many Indonesia scholars were occupied with studying the impact of Indonesia’s democratisation and decentralisation processes after the fall of the Soeharto regime in 1998, surprised by what they described as a distinct process of adat revivalism. The book revealed the various ways that adat revivalism deployed adat to defend traditional forms of local authority, ranging from the protection of marginalised forest communities to the demands of abolished sultanates to be reinstated. Some authors who contributed to the book were confident that adat could be an emancipatory force for the marginalised, but the book also showed that a focus on traditional institutions could contribute to structural inequality, elite capture and even lead to violent ethnic conflict. In short, what adat would mean for Indonesian society in the near future was prone to significant debate.

Henley and Davidson called it a paradox that ‘dispossessed people themselves demand justice, not in the name of marginality and dispossession, but in the name of ancestry, community and locality’ (Henley and Davidson Citation2007, 23). However, this observation becomes less paradoxical if we consider the symbolic role that adat has played in dominant ideologies of Indonesian nationhood. Adat has long been regarded an essential feature of Indonesian culture—as the soul of nationhood. It plays a prominent role in popular depictions of the harmonious and collective nature of Indonesian society (Bourchier Citation2014). Furthermore, Tania Li writes that invoking adat ‘is to claim purity and authenticity for one’s cause’ (Citation2007, 337). Therefore, claiming adat can at once invoke the deepest form of Indonesianness, while also standing for egalitarianism values, and representing the overall moral high ground.

One surprising feature of current adat debates however, is that scholars, activists and policymakers still tend to refer to adat scholarship of 100 years ago. During the Ethical Policy (1901–42) of the Netherlands East Indies, the colonial government held that subjecting Indonesians to their own local adat laws was the best form of governance, as imposing Western state law on the diverse and fragmented societies of the archipelago would be unjust and unnatural. To a significant extent, this policy leaned on the scholarly work of Leiden Law Professor Cornelis van Vollenhoven and his Adat School. Van Vollenhoven believed that adat law should be left to evolve gradually without much interference from the colonial state.

After Indonesian independence however, adat law had to make way for unified state law. National unity and modern citizenship could only be realised when all Indonesians were governed by the same set of rules. Local identities were subordinated to a single national one which undermined their ability to play a role in politics. Indonesian leaders and policymakers also associated adat with colonial divide and rule politics, and scholars have hence expressed fierce criticism towards the Dutch approach to adat law. Daniel Lev, in particular, noted that adat law ‘is fundamentally a Dutch creation’, meaning that it was the Dutch who tied adat law to the authority of the colonial state. Prior to the Dutch creation of adat law as a legal category, adat only existed in the context of local political and economic interests (Lev Citation1985, 63–64). Scholars like Lev and Peter Burns (Citation2004) argued that the Adat Law School and the policies based on its ideas were rooted in conservative political thinking that helped to legitimise the authority of the colonial state, while keeping Indonesia fragmented in scattered communities.

In response to these critiques, other scholars have argued that the work of the Adat Law School was in fact highly progressive for its time. They state that in contrast to a majority of legal scholars during the early twentieth century, adat law helped to advocate for interpreting local rules and norms in their own specific contexts ‘free from ethnocentric bias’ (von Benda-Beckmann and von Benda-Beckmann Citation2011, 177). Van Vollenhoven himself regarded adat law as being constantly in motion, as it changed in accordance to society’s needs. In this issue, Keebet von Benda-Beckmann argues that most present day adat advocates instead situate adat in a niche of continuity while disregarding its flexible and fluid character. Current conceptualisations, she argues, tend to view adat rights in a regressive manner, as generations-old norms and customary rules based on long-preserved traditions, rather than an ever-changing normative system that continues to evolve at the local level (von Benda-Beckmann, this issue).

The adat revival that emerged with Reformasi, and took on a new shape in post-Soeharto Indonesia, was above all a form of civil resistance against the power of the state (Li Citation2001; Peluso, Afiff, and Rachman Citation2008). Social justice advocates viewed the empowerment of local leaders and traditional institutions as a better alternative to state rule, which had failed its rural citizens. Whereas earlier struggles for rural justice in Indonesia were largely centred in Java and framed in terms of a class-based peasant movement, the new discourse reflected an exploitative and abusive state that had stripped indigenous communities from their customary lands and cultures (White Citation2016). This discursive shift that began in the early 1990s coincided with, and was emboldened by, the growing influence of the transnational indigenous peoples’ movement, and increased civil society discontent with Soeharto’s extractive policies in Indonesia’s resource-rich and culturally diverse outer islands. A second parallel development to the rising influence of the indigeneity discourse in Indonesia was decentralisation. As part of the extensive democratic reforms following Soeharto’s demise in 1998, decentralisation shifted a large degree of political decision-making to the regions (Afiff and Lowe Citation2007; Tyson Citation2010).

In the years of Reformasi, many scholars expressed their concerns about the possible implications of the revival of adat, particularly if this was to result in a fully fledged return to traditional forms of governance. Allowing adat to flourish could contribute to the further fragmentation of society along ethnic lines (Li Citation2001, 648). Some also worried that the renewed legitimacy of traditional power structures would only result in elite capture by local leaders, interpreting adat laws in ways that strengthened their position (Hooe Citation2012). Other scholars have warned that notions of adat presuppose a romanticised image of communitarian and rural communities living in harmony with the natural environment (Ellen Citation1986; Brosius, Tsing, and Zerner Citation1998; Li Citation2000). Such images are largely the result of the nexus between adat and the global indigeneity discourse. It is therefore important to delve deeper into this nexus, before we discuss the main findings and conclusions of this special issue.

Adat Frames and the Global Indigeneity Discourse

The indigeneity discourse links indigenous peoples to ‘social ethics, morality generally, politically progressive ideologies, and environmental consciousness’ (Canessa Citation2018, 314). These associations are embedded into the language of local NGOs in developing countries, and they also form the priority strategies of large international organisations such as the United Nations. In Indonesia, linking indigeneity to adat has emboldened the formation of new alliances between civil society organisations, government institutions and multilateral development organisations such as the World Bank (Avonius Citation2009). Influenced by an international discourse that emerged in the final quarter of the twentieth century, indigeneity frames draw upon local historical claims, but can only come into being through modern interactive processes, usually articulated by the support of powerful external actors, such as activists and NGOs, legitimated by local governments and other formal institutions (Hirtz Citation2003). Claiming rights and entitlement on the basis of indigeneity is therefore best understood as a political process (Li Citation2000; Canessa Citation2018).

In Latin America, the current significance of indigeneity is closely linked to structural socio-economic inequality between descendants of European settlers and people of non-European descent (Canessa Citation2018). In Africa and Asia however, such a dichotomy is absent; most European colonists have long left or were never there to begin with. In these settings, advocates of marginalised communities who engage in indigeneity politics face the challenge of determining who qualifies as indigenous. In Indonesia, where the government has long held that all citizens are equally indigenous, linking indigeneity to a modern, yet static interpretation of the colonial ‘adat community’ concept has helped to create an Indonesia-fit concept of indigeneity (Persoon Citation1998; van der Muur Citation2019). As a result, the indigeneity argument in Indonesia is generally not ‘We are indigenous because we were here first’ but, instead, ‘We are indigenous because we still preserve our customary traditions’. As a result, communities that no longer abide by traditional institutions risk falling out of the scope of indigeneity (van der Muur Citation2018). Several articles in this special issue however highlight that at present, indigeneity is not only invoked by vulnerable and marginalised communities to empower themselves and claim rights, but also by powerful actors at the regional and local level to acquire (or preserve) political and economic capital (Comaroff and Comaroff Citation2009).

The strategic deployment of the indigeneity argument that has created tension between activists and scholars is raised in the contribution by Suraya Afiff and Noer Rachman. Scholars often stress that romanticised notions of traditional rural communities are ‘theoretically dubious’, but activists argue that such notions provide a basis for mobilisation, helping communities to secure rights to land and natural resources (Sylvain Citation2014, 251–252). As such, efforts by scholars to deconstruct essentialist strategies are sometimes ‘at odds with political activism’ (Sylvain Citation2014, 253). Writing in the context of indigenous political mobilisations in South Africa, Renee Sylvain asserts that activists advocating for indigenous rights feel the need to convey a simplified, powerful message to obtain their objectives, even if this message does not present a realistic depiction of rural society. Sylvain thus offers a window for examining the tensions of political advocacy with the scholarly objective to provide contextualisation to such advocacy.

However, a different approach is necessary if we are to explain recent developments identified among scholars, namely that the deployment of indigeneity is not only conducted by marginalised people, but also by people in power. In Bolivia, for example, Valencia Canessa observes that ‘indigeneity has been transformed from being the language of resistance to the state by people on the political margins to the language of the state in expressing its legitimacy’ (Citation2018, 317). Against the backdrop of such observations, we argue that in order to grasp the many ‘adat projects’ in present-day Indonesia, it is necessary to look concretely at how different actors frame adat and how that framing corresponds with their interests. Therefore, the next sections are focused on the link between projects, interests and how actors use adat arguments strategically.

From Single Adat Movement to Fragmented Projects

AMAN, as the largest indigenous peoples’ rights organisation in Indonesia, initially depicted its struggle in terms of a national social movement against the state. AMAN uses indigeneity as a collective action frame, which can be understood as a collectively negotiated ‘“shared understanding” of some problematic condition or situation’ (Benford and Snow Citation2000). The underlying assumption of the national adat movement is that the ‘predatory state’ is incapable of realising justice for its citizens in remote rural and forested regions. The concept of adat community is used to imagine groups of local rural people as harmonious collectives in opposition to external actors, particularly those with whom they compete for land or other natural resources. This narrative has helped to mobilise AMAN’s network and connect it to the movement of global indigenism, solidifying their struggle against outside forces, in particular the oppressive state apparatus, its security forces (most notably the military), and their capitalist allies (Li Citation2001; Avonius Citation2009).

This framing of communal egalitarianism versus powerful external state interests has become so pervasive that it may blur researcher sensitivities for the many internal fragmentations within the movement. In recent years however, adat proponents have formed coalitions with state actors. Indeed, the 2015 AMAN national congress introduced a theme explicitly highlighting partnerships with government institutions.Footnote3 Afiff and Rachman’s contribution in this special issue illustrates the new version of this activist perspective. Their article reiterates the dominant discourse of one single national adat movement, while emphasising that ‘the state’ as a monolithic enemy has ceased to exist. Instead the authors differentiate between government institutions, recognising ‘reformist bureaucrats’ in selected national institutions as potential allies for activists, while depicting other government institutions as barriers against reform.

In addition, as discussed in the contribution by Adriaan Bedner and Yance Arizona, policy preferences regarding customary land rights vary between different government agencies and ministries. Bedner and Arizona highlight the existence of new opportunities for strategic alliances between adat activists and reformist bureaucrats, as well as the continued contestations across ministerial policies. Meanwhile, Afiff and Rachman’s empirical material describes how a few national activists have acquired positions within certain government institutions, providing them with influence in the policy-making process concerning adat community land rights to forest land. The perception that these activists represent a large national social movement consisting of millions of people all over Indonesia is crucial for obtaining such government positions. Afiff and Rachman argue that the prospect of pro-adat policies translating into a large number of voters in the presidential elections of 2014 was also an important factor explaining the pro-adat decisions of the Widodo administration. However, they also argue that the political momentum allowing such decisions was only temporary and, hence, such coalitions are fragile and dependent on potential political opportunities. By way of example, we observed during the 2019 presidential campaign, AMAN withdraw their explicit political support for presidential candidates.

Other articles in this special issue point to a diverse spectrum of indigenous politics. What emerges from this overall landscape of adat politics in Indonesia is a fragmentation across many ‘adat projects’. That view corresponds with Edward Aspinall’s (Citation2013) analysis of how a process of fragmentation is unfolding among the various layers of government and Indonesian civil society. In his view, large programs and policies are being fragmented into many projects (Indonesian: proyek), with bounded goals and a limited duration, functioning as a mechanism for distributing economic resources.

Li (Citation2016) has also introduced the notion of a project system, juxtaposing rural governance historically with its contemporary forms in Indonesia. Therein she shows that governance across rural Indonesia is almost exclusively discussed in terms of projects. This project system, she argues, has become ‘so routine that alternative ways of thinking and acting are scarcely considered’ (Li Citation2016, 79). Projects typically involve a funded, time-bound and short-term technical intervention to solve a particular problem, while the larger structural and political issues that may underlie rural problems remain unaddressed. The main ideas about indigeneity as countless small communities fragmented across the archipelago suit the project system well. The indigeneity discourse hence sustains the notion that each community requires a specific intervention, rather than the adoption of a society-wide policy. Meanwhile, discussions on the driving factors of social inequality, rural poverty and land dispossession are largely avoided. The project system persists because of the benefits it brings to government actors and rural elites, not in the least local officials and adat elites.

Analysing adat struggles from the perspective of fragmented projects makes it possible to understand why national NGOs sometimes represent local communities in ways that do not correspond with common interests among community members (Fisher and van der Muur, this issue). Using the term ‘adat projects’ furthermore links the discussion on the strategic use of adat to the debate on Indonesian governance and vice versa, not only situating adat politics in the context of decentralisation reforms, but also situating adat in the global movements for indigeneity. It also helps to explain why NGOs sometimes represent only the interests of one specific group.

In her contribution to this issue, Kathryn Robinson highlights the tension between the local framing of adat and the discourse of national adat organisations in the case of land dispossession in a mining area in South Sulawesi. She finds that recent advocacy efforts by national-level adat activists failed to represent the original land claimants who took issue with the mining site. Some communities were supported in their claims by national NGOs, whereas others with stronger historical claims were ignored. The case demonstrates that the recognition of adat claims by one community may lead to the erasure of other claims (Robinson, this issue).

Many adat projects are funded by international donors or development organisations and channelled through Jakarta-based NGOs towards the regions. The Development Grant Mechanism Indonesia (DGM-I) for example, consists of a World Bank-administered program to support small grants specific to adat projects across Indonesia. The DGM-I works in several stages, supporting legal mechanisms to formalise recognition, followed by block grants to support development programming. Other programs are financed and promoted by international development organisations but implemented by government agencies. The implementation of REDD+ (reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation plus sustainable forest management) in Indonesia for example, is in the hands of the Indonesian government, but supported by various United Nations outfits and a billion US dollar grant from the Norwegian government. REDD+ programs designate indigenous peoples as potential beneficiaries and participants of such a large market-oriented environmental program (Astuti and McGregor Citation2017).

At the local level, various adat projects usually co-exist and overlap. They sometimes clash (Robinson, this issue), while in other cases converge strategically (Vel and Makambombu, this issue). A recent development across all cases however, is the increased role of district governments in such projects. District heads (bupati) and regional parliament members in particular are increasingly involved in bartering adat community recognition for election votes, or as a wedge to drum up support as a form of identity politics against immigrants, regional tourism boards promoting adat tourism projects, and adat elites who hold dual positions in formal district government positions that use their position to optimise their interests in both realms.

Assessing indigeneity politics in the context of the project system shows that ideas about adat are subject to a variety of contingent processes of manipulation and elite capture. In such conditions, the interests of less powerful or socially marginal people are often overruled or ignored. The irony is, of course, that the discourse of indigeneity seeks to challenge these very power structures to empower the marginalised and dispossessed.

A Variety of Adat Projects

Most adat projects of recent years were initiated with the objective to secure government recognition of a particular adat community and its collective land rights. In the eyes of NGOs and activists, only formal recognition of community rights can keep out plantation companies and other forms of encroachment by state actors. However, formal recognition requires the approval of district governments and, therefore, advocates of adat rights are bound to engage in existing patronage structures. Micah Fisher and Willem van der Muur’s article provides an example of a project that was set up to recognise an adat community in South Sulawesi. It was initiated by NGOs that eventually came to involve many actors, including adat elites and a number of district government departments. The project achieved its primary goal, namely, the enactment of a regional regulation recognising the community’s indigenous status and rights to its customary territory. However, the authors demonstrate in their article that this recognition did very little to improve the lives of the average community member.

Arizona’s contribution systematically investigates the process of legal recognition and presents an analytical framework that distinguishes the steps in the recognition process, helping to identify the roles of the various actors engaged in the process, each with their own specific objectives. For the NGOs involved, legal recognition appears above all as a means to legitimise their cause to the outside world, even if such recognition bears little relevance to the actual situation on the ground. For the district government departments involved, facilitating recognition offers a chance to show goodwill towards the cause of rural communities and can also support the conditions to boost opportunities for cultural tourism.

For those holding positions of power and authority in the regions, adat projects are rarely about empowering marginalised and vulnerable rural communities. Instead, referring to adat offers avenues for identity politics in regional and local elections. Veronika Kusumaryati shows this to be the case in her contribution describing how adat politics have evolved in Papua, namely that they have been ‘codified as an integral part of decentralised governance and development policies’. Her analysis shows how adat is the battleground for various political actors in West Papua, including the Indonesian central government and Papuan independence movements.

As various contributions in this special issue point out, government institutions have become one of the most important stakeholders in adat projects. All of the case studies highlight the paradoxical result of the politics of indigeneity in Indonesia. Rather than reducing state power, which was the initial purpose of the post-1998 revival of adat, the fragmentation of adat projects in fact serves to further reinforce the power of state institutions. For example, adat communities have more opportunities to obtain formal recognition of their land rights when they maintain good relations with regional government authorities (van der Muur Citation2018). This type of relationship no doubt makes it more difficult to challenge the very structures of inequality. The contributions in this special issue also clearly show that adat projects are more likely to succeed when certain members among those making claims also hold influential positions in the regional government. As a consequence, certain government institutions have become partners in adat projects, whereas other government institutions may still be considered as adversaries to adat.

Governing adat on the basis of projects, rather than on a single policy providing clear rules, thus allows different stakeholders to negotiate over the meaning and scope of what adat is and should be. This allows the various parties involved to bargain for the outcome of a project in a way that serves their interests. Against this backdrop, it is not surprising that a National Bill on Adat Communities has yet to be enacted, despite many years of advocacy by organisations such as AMAN. Our analysis of the possible implications of such a bill is twofold. A single bill with a clearly laid-out set of standardised rules on adat rights recognition could render the majority of adat projects superfluous as it would take away the bargaining power of regional and local authorities in recognising rights. That said, if such a bill was to be vaguely defined and its implementation made contingent on the discretionary powers of national or sub-national government agencies, then a national bill shall likely be co-opted by the project system.

Studies from the Philippines suggest the likelihood of the latter scenario. The 1997 Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (IPRA) was promulgated in the Philippines to provide tenure security to indigenous communities. The IPRA provides a legal basis for communities to obtain Certificates of Ancestral Domain Titles (CADT). Although the IPRA has increased the bargaining power of communities vis-à-vis corporations and state agencies, the extent to which communities are actually able to obtain communal land certificates is dependent on their ties with regional power holders. For communities seeking to benefit from the IPRA, ‘positioning in local power constellations is key’ (Rutten Citation2015–Citation16, 3). Hence, despite the enactment of a national bill on indigenous rights, the situation in the Philippines does not seem to differ significantly from Indonesia, where informal ties to local power holders is also a prerequisite for legal recognition. June Prill-Brett notes that the implementation of the IPRA has mostly been implemented in favour of local elites, who sometimes have privatised land rights after obtaining a communal certificate (Citation2007, 24).

Tody Sasmitha makes a similar observation in the context of Indonesia’s Village Law in his analysis of the ‘adat village’ mechanism (Sasmitha, this issue). The 2014 Village Law allows communities to register their village as a traditional adat village. Sasmitha’s national-level analysis however highlights key aspects whereby the adat village provision can be co-opted as part of the political process. Furthermore, his analysis scales down to the village level from a small community in Kalimantan seeking to claim adat village status. Although the Balai Kiyu community sought to achieve designation with adat village status, existing village authorities that questioned their claims of authenticity ultimately undermined the effort. To this date, there are only a handful of villages in Indonesia that have gained the status of adat village. Hence, an important lesson from this special issue is that when studying adat projects, a central question should be ‘what’s in it for whom?’

Marginal Groups and Adat Elites

In addition to the pervasiveness of fragmented adat projects, the articles in this special issue also point to the dichotomy between adat majorities and minorities, and its relevancy for scholarly analysis. Indigeneity is generally understood as a frame adopted by marginalised ethnic minorities in search of entitlements from a state that is dominated by a powerful ethnic majority (Gausset, Kenrick, and Gibb Citation2011; Zenker Citation2011). Although such a depiction might have empirical validity for some Indonesian groups,Footnote4 the strategic framing of adat is adopted in very different settings involving actors with diverse backgrounds. The articles in this issue suggest that explaining the many political forms of adat is contingent upon whether the adat community is a small minority of the district’s population or comprises a major part of it.

The typical framing in national adat campaigns depicts communities as small minorities that are politically and economically marginal. However, there are also cases in which the ‘adat community’ comprises a large part of the district population or majority of a sub-district. Under decentralised governance structures the difference between district minority and majority becomes pronounced because of the way it shapes democratic elections. However, if the adat community is defined in an inclusive way that makes it very large, the identity claims may become weak when contested by outside parties like plantation companies. Ahmad Dhiaulhaq and John McCarthy (this issue) point out the dilemma that many adat advocates face. If they succeed in mobilising a community through a narrowly defined concept of indigenous identity, other groups may be excluded. In their example of an adat mobilisation to make land claims against a plantation company in Riau, Sumatra, the company used an adat frame to exclude claimants that did not fit the indigeneity criteria, resulting in a reduced land area that the community could claim.

Several articles in this issue analyse adat majority cases, and each of them confirms the conclusions of earlier studies, namely that adat elites are the main actors in promoting or reviving adat (Bakker Citation2009; Hooe Citation2012; von Benda-Beckmann and von Benda-Beckmann Citation2013). Adat elites also play a central role as the main proponents of the common practice in Indonesian politics of splitting up districts (pemekaran), guiding decisions on whether their adat community forms a majority of the district population. This has taken place in the case of West Sumba (Vel Citation2008), and also helps to explain why plans to bid for village autonomy failed in Sasmitha’s (this issue) case from Kalimantan.

In contrast to the dominant narrative of isolated and marginalised tribes, various studies in this special issue were conducted in areas where large parts of the population could make a case for indigenous status, including regional power holders. In these areas, adat elites dominate local politics, and, hence, play a decisive role in adat projects. In the case of East Sumba for example, adat elites used adat claims as a way to make deals with businesses to the disadvantage of local community members. The elites claimed authority to represent their broader community in negotiations with a plantation company. However, these claims subsequently sparked internal conflict between clans claiming rights to the land that the company was converting into a plantation. Jacqueline Vel and Stepanus Makambombu’s article shows the powerful position of such adat elites who also occupy high positions in the district government, putting them first in line for obtaining information on new investments in agriculture, and supporting their claims for financial compensation. As this case shows, the line between adat and the state is often blurry. Elites who are alienated from their clan land, yet claim to be adat leaders no longer share the interests of their farmer-clan members whose livelihoods are in danger because of land dispossession for plantation establishment. Plantation companies can easily divide the members of a large adat community by paying compensation to some of those members who then refrain from demanding the company return land to the tillers.

These ‘majority cases’ indicate that national pro-adat policies can be deployed in local politics to support adat elites and their positions of power. The success of such elites can bring benefits to the wider community in the form of patronage networks. However, such a politics provides very limited opportunity for any meaningful engagement by vulnerable community members to secure access to ancestral lands for their livelihoods. These elites are often more loyal to their provincial and central government peers or corporate allies than to their subordinates. This also provides an important insight for the proposed National Bill on Adat Communities, which would regulate adat issues nationally in a uniform fashion despite the variety of local contexts. A general lesson from across the articles of this special issue is that the nexus between marginality and adat, or indigeneity more generally, should be questioned and empirically investigated (see also van der Muur Citation2019).

The Future of Indigeneity in Indonesia and Adat Studies

The paradoxical outcomes of adat projects in Indonesia raise the issue of engaging possible alternatives to indigeneity as a basis to claims rights and entitlement to resources. There are, of course, other discourses and frames to claim rights from the state, and scholars have advocated for the adoption of a more inclusive rights-based approach in the name of citizenship (see, for instance, Li Citation2001). Others have argued for a return to a more class-oriented, peasant-based approach (White Citation2016). In this special issue, Dhiaulhaq and McCarthy also empirically show in a comparison between an agrarian reform frame and an indigeneity frame, that the former is more effective in claiming more inclusive land rights. Indeed, they argue that:

the agrarian justice framing tends to be more inclusive. As this framing fits more readily with the heterogeneous rural context, it enables community actors to mobilise a wider coalition more effectively, thereby enhancing the political leverage required to achieve better outcomes in contrast to the indigenous rights (adat) framing.

Although we have listed various implications for Indonesia, the findings from across the special issue are also relevant beyond Indonesian borders. The project approach adopted in this introduction article could, therefore, be a useful analytical framework for other contexts. In sub-Saharan Africa for example, Janine Ubink has noted that the resurgence of traditional authority coincided with the wave of democratisation, giving rise to debate on the desirability and legitimacy of traditional authority in modern forms of governance (Ubink Citation2008). Despite the regional differences, the adoption of indigeneity frames always involves a political process, and, hence, these processes need to be understood in order to grasp the outcomes of projects and policies on the basis of indigeneity. This requires more than legal and policy research, and demands more attention from the lens of political economy analysis. Within Indonesia, adat law studies should therefore no longer be just a branch of law studies and anthropology, but also become part of wider academic debate involving political science, sociology, cultural studies and human geography.

Finally, we hope that the articles in this special issue will inspire further studies that utilise innovative methods and research approaches that continue to dig deeper into these perplexing and often contradictory dynamics. Foremost, what would it take to bring the political economy consideration to the forefront amidst the growing legitimacy of adat projects? Furthermore, prospective research could include an investigation about how transnational networks for indigeneity are further ingrained, namely how the support among indigeneity NGOs, their programs, and funding shapes new practices going forward. Across Indonesia, as AMAN (and other activist organisations) maintain their narrative of empowerment of the rural dispossessed, what are the implications of the widespread co-optation and elite capture that have occurred amidst the conciliations made to secure adat projects? The study of indigeneity in Indonesia would also benefit from regional comparisons between countries, as was recently done by Canessa (Citation2018) in the context of Latin America and Africa. Southeast Asia as a region has distinct and deeply rooted dynamics relative to core–periphery, upland–downstream, and other relational dynamics. Finally, deeper empirical material that draws from a larger variety of case studies on adat projects would further confirm or reject the claims made herein, providing more robust analysis, and following along the new developments that might emerge from indigenous politics in Indonesia. That would imply that the selection of case studies be based on academic and analytical criteria, instead of selecting success cases of famous and iconic communities, or the commonly presumed emancipatory potential of adat. Such an approach would seek to improve the analytical framework for studying the politics of indigeneity and help to define the crucial context variables across different research locations.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge with thanks the funding assistance provided by Leiden University's Asian Modernities and Traditions (ATM) towards the production of this special double issue.

Notes

1 “Adat Law 100 years on: Towards a New Interpretation?” (Citation2017).

2 The year 2017 marks exactly one century since the famous legal scholars Cornelius van Vollenhoven and Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje established the Adat Law Foundation (Adatrechtstichting) in Leiden (the Netherlands) that published dozens of studies on adat law based on one of the largest research projects ever conducted by the Law Faculty of Leiden University.

3 AMAN’s statement that emerged from the 2015 congress is as follows: ‘The theme of KMAN V is “to change the state through action”, which highlights the role of the government and non-government institutions in shaping an Indonesia that is better for indigenous peoples across the archipelago’. Original Indonesian: ‘Tema KMAN V adalah “Melakukan Perubahan Negara dengan Tindakan Nyata” yang menyoroti peran pemerintah dan nonpemerintah dalam mewujudkan Indonesia yang lebih baik bagi Masyarakat Adat di Nusantara’.

4 See Christian Wawrinec (Citation2010) on the case of marginalised and extremely impoverished hunter-gatherer tribes of Sumatra’s interior.

References

- “Adat Law 100 years on: Towards a New Interpretation?”. 2017. National Museum of Ethnology, Leiden, May 22–24. Accessed August 22, 2019. http://www.kitlv.nl/conference-adat-law-100-year/.

- Afiff, Suraya, and Cecilia Lowe. 2007. “Claiming Indigenous Community: Political Discourse and Natural Resource Rights in Indonesia.” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 32: 73–97. doi:10.1177/030437540703200104.

- Aspinall, Edward. 2013. “A Nation in Fragments: Patronage and Neoliberalism in Contemporary Indonesia.” Critical Asian Studies 45 (1): 27–54. doi:10.1080/14672715.2013.758820.

- Assies, William. 2000. “Introduction.” In The Challenge of Diversity: Indigenous Peoples and Reform of the State in Latin America, edited by Willem Assies, Gemma van der Haar, and A. J. Hoekema, 3–22. Amsterdam: Thela Publishers.

- Astuti, Rini, and Andrew McGregor. 2017. “Indigenous Land Claims or Green Grabs? Inclusions and Exclusions Within Forest Carbon Politics in Indonesia.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 44 (2): 445–466. doi:10.1080/03066150.2016.1197908.

- Avonius, Leena. 2009. “Indonesian Adat Communities: Promises and Challenges of Democracy and Globalisation.” In The Politics of the Periphery in Indonesia: Social and Geographical Perspectives, edited by Minako Sakai, Glenn Banks, and J. H. Walker, 219–240. Singapore: NUS Press.

- Bakker, Laurens. 2009. “Who Owns the Land? Looking for Law and Power in East Kalimantan.” PhD diss., Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen.

- Benford, Robert D., and David A. Snow. 2000. “Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment.” Annual Review of Sociology 26 (1): 611–639. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611.

- Birell, Kathleen. 2016. Indigeneity: Before and Beyond the Law. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315761312.

- Bourchier, David. 2014. Illiberal Democracy in Indonesia: The Ideology of the Family State. London and New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203379721.

- Brosius, J. Peter, Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, and Charles Zerner. 1998. “Representing Communities: Histories and Politics of Community-Based Natural Resource Management.” Society & Natural Resources 11 (2): 157–168. doi:10.1080/08941929809381069.

- Burns, Peter J. 2004. The Leiden Legacy: Concepts of Law in Indonesia. Leiden: KITLV Press.

- Canessa, A.A. Valencia. 2018. “Indigenous Conflict in Bolivia Explored Through an African Lens: Towards a Comparative Analysis of Indigeneity.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 60 (2): 308–337. doi:10.1017/S0010417518000063.

- Comaroff, John L., and Jean Comaroff. 2009. Ethnicity, Inc. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226114736.001.0001.

- Ellen, Roy F. 1986. “What Black Elk Left Unsaid: On the Illusory Images of Green Primitivism.” Anthropology Today 2 (6): 8–12. doi:10.2307/3032837.

- Gausset, Quentin, Justin Kenrick, and Robert Gibb. 2011. “Indigeneity and Autochthony: A Couple of False Twins?” Social Anthropology 19 (2): 135–142. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8676.2011.00144.x.

- Hale, Charles R. 2002. “Does Multiculturalism Menace? Governance, Cultural Rights and the Politics of Identity in Guatemala.” Journal of Latin American Studies 34: 485–524. doi:10.1017/S0022216X02006521.

- Hauser-Schäublin, Brigitta, ed. 2013. Adat and Indigeneity in Indonesia: Culture and Entitlement Between Heteronomy and Self-Ascription. Göttingen Studies in Cultural Property, Volume 7. Göttingen: Universitsverlag Göttingen. doi:10.4000/books.gup.150.

- Henley, David, and Jamie S. Davidson. 2007. “Introduction: Radical Conservatism – the Protean Politics of Adat.” In The Revival of Tradition in Indonesian Politics. The Deployment of Adat From Colonialism to Indigenism, edited by Jamie S. Davidson, and David Henley, 1–49. London and New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203965498.

- Hirtz, Frank. 2003. “It Takes Modern Means to be Traditional: On Recognizing Indigenous Cultural Communities in the Philippines.” Development and Change 34 (5): 887–914. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2003.00333.x.

- Hooe, T.R. 2012. “Little Kingdoms: Adat and Inequality in the Kei Islands, Eastern Indonesia.” PhD diss., University of Pittsburgh.

- Lev, Daniel S. 1985. “Colonial Law and the Genesis of the Indonesian State.” Indonesia 40: 57–74. doi:10.2307/3350875.

- Li, Tania Murray. 2000. “Articulating Indigenous Identity in Indonesia: Resource Politics and the Tribal Slot.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 42 (1): 149–179. doi:10.1017/S0010417500002632.

- Li, Tania Murray. 2001. “Masyarakat Adat, Difference, and the Limits of Recognition in Indonesia’s Forest Zone.” Modern Asian Studies 35 (3): 645–676. doi:10.1017/S0026749X01003067.

- Li, Tania Murray. 2007. “Adat in Central Sulawesi: Contemporary Deployments.” In The Revival of Tradition in Indonesian Politics. The Deployment of Adat From Colonialism to Indigenism, edited by Jamie S. Davidson, and David Henley, 337–370. London and New York: Routledge.

- Li, Tania Murray. 2016. “Governing Rural Indonesia: Convergence on the Project System.” Critical Policy Studies 10 (1): 79–94. doi:10.1080/19460171.2015.1098553.

- Moniaga, Sandra. 2007. “From Bumiputera to Masyarakat Adat: A Long and Confusing Journey.” In The Revival of Tradition in Indonesian Politics: The Deployment of Adat From Colonialism to Indigenism, edited by Jamie S. Davidson, and David Henley, 275–294. London and New York: Routledge.

- Peluso, Nancy Lee, Suraya Afiff, and Noer Fauzi Rachman. 2008. “Claiming the Grounds for Reform: Agrarian and Environmental Movements in Indonesia.” Journal of Agrarian Change 8 (2–3): 377–407. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0366.2008.00174.x.

- Persoon, Gerard. 1998. “Isolated Groups or Indigenous Peoples: Indonesia and the International Discourse.” Bijdragen Tot de Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde 154 (2): 281–304. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003899.

- Prill-Brett, June. 2007. “Contested Domains: The Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (IPRA) and Legal Pluralism in the Northern Philippines.” The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law 39 (55): 11–36. doi: 10.1080/07329113.2007.10756606

- Rutten, Rosanne. 2015–16. “Indigenous People and Contested Access to Land in the Philippines and Indonesia.” Kasarinlan: Philippine Journal of Third World Studies 30(2)/ 31(1): 1–29.

- Sylvain, Renee. 2014. “Essentialism and the Indigenous Politics of Recognition in Southern Africa.” American Anthropologist 116 (2): 251–264. doi:10.1111/aman.12087.

- Tyson, Adam. 2010. Decentralization and Adat Revivalism in Indonesia: The Politics of Becoming Indigenous. London and New York, NY: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203849903.

- Ubink, Janine. 2008. Traditional Authorities in Africa: Resurgence in an Era of Democratisation. Leiden: Leiden University Press. doi:10.5117/9789087280529.

- van der Muur, Willem. 2018. “Forest Conflicts and the Informal Nature of Realizing Indigenous Land Rights in Indonesia.” Citizenship Studies 22 (2): 160–174. doi:10.1080/13621025.2018.1445495.

- van der Muur, Willem. 2019. “Land Rights and the Force of Adat in Democratizing Indonesia: Continuous Conflict between Plantations, Farmers, and Forest in South Sulawesi.” PhD diss. Van Vollenhoven Institute, Leiden University.

- Vel, Jacqueline. 2008. Uma Politics: An Ethnography of Democratization in West Sumba, Indonesia, 1986–2006. Brill: KITLV. doi:10.26530/OAPEN_393150.

- von Benda-Beckmann, Franz, and Keebet von Benda-Beckmann. 2011. “Myths and Stereotypes About Adat Law: A Reassessment of Van Vollenhoven in the Light of Current Struggles Over Adat Law in Indonesia.” Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 167 (2–3): 167–195. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003588.

- von Benda-Beckmann, Franz, and Keebet von Benda-Beckmann. 2013. Political and Legal Transformations of an Indonesian Polity: The Nagari From Colonisation to Decentralisation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139839082.

- Wawrinec, Christian. 2010. “Tribality and Indigeneity in Malaysia and Indonesia: Political and Sociological Categorizations.” Stanford Journal of East Asian Affairs 10 (1): 96–107.

- White, Ben. 2016. “Remembering the Indonesian Peasants’ Front and Plantation Workers’ Union (1945–1966).” The Journal of Peasant Studies 43 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1080/03066150.2015.1101069.

- Zenker, Olaf. 2011. “Autochthony, Ethnicity, Indigeneity and Nationalism: Time-Honouring and State-Oriented Modes of Rooting Individual-Territory-Group Triads in a Globalizing World.” Critique of Anthropology 31 (1): 63–81. doi:10.1177/0308275X10393438.