Abstract

In the two decades of economic recovery in post-Independence Timor-Leste (2002–2022), there has been a growing interest and commitment, especially among young people, to pursue temporary and circular labour migration. In this paper I draw on a survey of returned Fataluku-speaking labour migrants who have spent varying periods of time working in the UK (Britain) and reflect on their experiences and the benefits or otherwise that have resulted from these efforts. The survey was undertaken in late 2019, just before the onset of the global Covid-19 pandemic. The subsequent lockdown and border closures marked the effective end of this remarkable, two-decade long, informal Timorese circular labour migration to the UK. A post-Covid landscape may yet see a lively resumption of this livelihood pathway, but it will do so in the uncertain terrain of a post-Brexit landscape in the UK and the prospects of new labour migration options available closer to home in Australia under the Seasonal Workers Program and Pacific Labour Schemes (PLS).

Introduction

Throughout two decades of economic recovery in post-Independence Timor-Leste (2002–2022), there has been a growing interest, especially among young people, to pursue forms of temporary labour migration. This trend can be seen in the drift of population from the rural hinterland and regions to the towns and cities in search of employment and opportunity (McWilliam Citation2015). It has also encompassed a shift to transnational labour migration in the form of temporary and circular periods of work. Like their counterparts elsewhere in contemporary Southeast Asia and in the wider patterns of globalised labour, the common push factor in Timor-Leste is economic insecurity and unemployment as migrants seek pathways out of poverty and alternate means to support their families (see Hugo Citation2009; McKay Citation2007, Citation2016; Rigg and Vandergeest Citation2012).

These push factors have been particularly acute in Timor-Leste with its young population and median age under 20 years (UNDP Citation2018). In 2016, this demography resulted in some 20,000 new entrants to the job market competing for no more than 2000 paid positions in the formal economy (ILO Citation2016). At the same time, the absence of manufacturing and a nascent private sector has produced few jobs, resulting in large numbers of citizens remaining under-employed, often living off intermittent or casual work as labourers or traders in the informal sector. These factors combine with a high prevalence of poverty in Timor-Leste, particularly in rural areas where 42 per cent of citizens live on less than USD2 a day (UNICEF Citation2018) and long-term under-investment in agriculture severely constrains the emergence of a higher value, productive rural sector (see Scheiner Citation2019; Young Citation2013).

For youthful aspiring Timorese workers, the opportunity to engage in international labour migration to a variety of destinations emerged gradually as a livelihood option following the end of Indonesian occupation of the territory and the declaration of Independence. In this article I draw on a survey of 70 returned labour migrants who have spent varying periods of time working in the United Kingdom (UK), taking up low-skilled factory jobs and opportunities in the hospitality sector for minimum wages while building savings over time to support their families at home. Their return to Timor-Leste for longer or shorter periods of time provided an opportunity to survey their experiences and the benefits or otherwise that have resulted from their efforts. The study draws comparatively on several previous surveys of Timorese labour migration (see McWilliam and Monteiro Citation2019; Reis, Cabral, and Valentim Citation2016; Schuaib Citation2007) but maintains a focus on the present returnees, their experiences and aspirations.

The present study was undertaken in late 2019, just before the onset of the global Covid-19 pandemic, which resulted in a complete and extended lockdown of international air travel and the closure of national borders through 2020 and beyond. The survey is therefore a snapshot of attitudes and experiences at a time when there was every expectation among circular migrants that they would return to rebuild depleted savings. A post-Covid landscape may yet see a lively resumption of this livelihood pathway, but it will do so in the uncertain and more complex regulatory terrain of a post-Brexit landscape in the UK with much more restrictive access for foreign workers. Fortunately for would-be migrants, the recent 2021 expansion of the Australian Seasonal Workers Program (SWP) and the Pacific Labour Scheme (PLS), both of which are now open to Timorese temporary labour migrants under expanded bilateral agreements, offer a potentially transformative, alternative livelihood option much closer to home. In both cases, the study highlights the growing contribution of temporary labour migration to the broader economic fortunes of Timor-Leste society.

Background Context

In the post-Independence context of Timor-Leste, two general types of temporary labour migration have found favour and become increasingly popular. One of these approaches, beginning in 2009, is based on formal Timor-Leste government bilateral agreements for labour exchanges, initially with South Korea and now Australia. These programmes are intended to provide fixed-term employment contracts for suitable candidates who are selected and managed through the Timorese government Secretariat of State for Professional Training and Employment (SEPFOPE). These limited schemes initially attracted small numbers of applicants, but their popularity and numbers have increased steadily in recent years as demand and work opportunities have expanded (Wigglesworth and Fonseca Citation2016; Wigglesworth and dos Santos Citation2018). The capacity for participants to undertake successive labour migration contracts has been another factor driving interest in the schemes.

A second form of transnational labour migration has been directed to the UK (including Northern Ireland) and has its unlikely origins during the Independence struggle in Timor-Leste. In the mid-1990s when young East Timorese student activists came under persecution from Indonesian security forces, they sought and secured political asylum by clambering into the compounds of various foreign embassies in Jakarta. Between 1993 and 1996, hundreds of young clandestinos, utilising the Indonesian-student based RENETIL (Resistência Nacional dos Estudantes de Timor-Leste) activist networks of protection and passage, escaped to Western Europe and continued their campaigns of protest against Indonesian occupation (see Pinto and Jardine Citation1997; Silva Citation2013).

Although a majority of these transplanted asylum seekers (suaka politiku) began their expatriate lives in Lisbon, Portugal, over time a few made their way to centres such as London, Liverpool and Oxford in the UK, where they found local support for their cause and intermittent work to sustain their campaigns for independence. It is from these unlikely pioneering settlers, who maintained their familial and political ties to Timor-Leste, that the labour migration of young East Timorese took root (McWilliam Citation2020).

The growth of Timorese labour migration to the UK since 2000 has been entirely informal and spontaneous, relying for the most part on word of mouth and familial connections. But its success and sustained growth has depended on a number of vital enabling factors, including: (1) the decision by Portugal to recognise all Timor-Leste people born before 2002 (National Independence) as Portuguese citizens and hence able to acquire passports that provided open access and work opportunities across the European Union. (2) The good fortune to find a sponsor in Lisbon who could facilitate the process of securing a Portuguese passport for Timorese applicants. These services were often undertaken by expatriate Timorese relatives familiar with the Portuguese bureaucracy and willing to offer their services. (3) Booming economic conditions in the UK from the early 2000s provided significant and comparatively well-paid work opportunities for low-skilled migrants with marginal English language skills. (4) The deregulation of global airlines by 2010 dramatically reduced flight costs, offering labour migrants cut price return airfares between Dili and Heathrow. (5) Finally, the dramatic rise and expansion of global telecommunications, the Internet and social media platforms, extending into Timor-Leste, opened up the possibility of fast, cheap communication between migrants and their erstwhile families back home. The Internet fostered new economic imaginaries for many aspiring young Timorese facing bleak employment prospects at home and with little likelihood of improved conditions.

For 20 years this practice of travel and circular labour migration has flourished and expanded (especially from 2010) as increasing numbers of young Timorese took up comparatively well-paid, low-skilled employment in factories, restaurants, supermarkets and hotels across England (Inglatera) and Northern Ireland (Irlandia) (McWilliam Citation2020). Living for the most part in group houses and sharing the costs of food and entertainment, money judiciously saved from low wage shift work has formed the basis of a thriving cash remittance economy (McWilliam and Monteiro Citation2019).

Just how many aspiring Timorese workers have participated in this migration is open to debate. The 2015 Timor-Leste National Census reported a total of 5350 Timor-Leste citizens ‘living in European countries other than Portugal’, which in reality meant the United Kingdom (National Directorate of Statistics Citation2016). But this figure excludes large numbers of migrants who, at the time of recording, were visiting Timor-Leste for holidays, family commitments or longer breaks between further periods of employment overseas.

Survey Sample

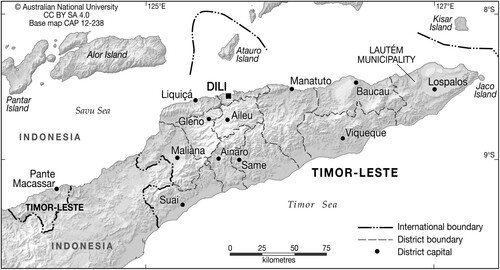

The purpose of the field survey of returnee migrants was to gain comparative perspectives on migrant work experiences in the United Kingdom including duration and residential locations, remittance practices and work activities since returning to Timor-Leste. The 70 respondents who participated in the survey were drawn from returned Fataluku language community migrant workers living predominantly in the municipality of Lautem (80 per cent) in far eastern Timor-Leste, with another group resident in the capital, Dili (20 per cent). My interest in Fataluku experiences reflects a background in longer-term ethnographic work among these communities beginning in 2000, and the reality that Fataluku were early adopters of the migration option to the United Kingdom. Their comparatively high rates of participation were influenced by their familial connections to sponsors and supporters already resident in Portugal and England (see McWilliam Citation2020).Footnote1 This factor also shaped the selection of prospective participants for the survey, many of whom were drawn from the regional capital of Lautem municipality, Los Palos, and its 11 constituent suburbs (aldeia) [>40 per cent]. The remainder were chosen from nearby surrounding villages in Lautem (especially Asaleino and Homé) along with a selection of participants from Dili residential areas (e.g. Bemoris, Becora, Farol, Maulo’o and Bidau Santana) (). The field surveys were commissioned and undertaken with my colleagues, Carmeneza Dos Santos Monteiro and staff of the local Lautem non-government organisation, Fundamor, during the latter months of 2019.

Results and Analysis

Since the initial survey of the informal Timorese UK migrant experiences conducted by Fikreth Schuaib in 2007 (Schuaib Citation2007), all subsequent assessments have revealed a range of common themes and findings in relation to migrant experiences (see Reis, Cabral, and Valentim Citation2016; McWilliam and Monteiro Citation2019). This commonality is perhaps not surprising given that the Timorese labour migrant experience has tended to follow a set of shared pathways and practices that have resulted in consistent outcomes both in the United Kingdom and when labour migrants return to Timor-Leste.

Gendered Migration and Age Groups

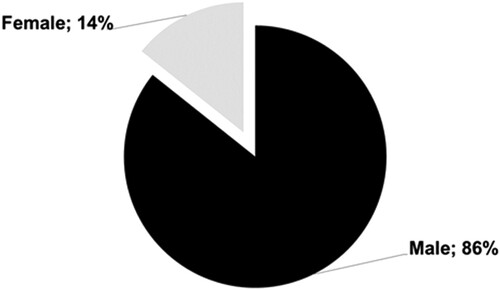

The gender ratio of labour migrants in previous surveys reveals a predominance of males and a consistent minority (10 per cent) of female labour migrant participants. The low level of female participation is also evident in the present assessment and reflects, in my view, the widespread concern of parents and close family members when their daughters and sisters seek to embark on the long-distance migration journey to the other side of the world. Risks to their personal safety and family reputation are usually uppermost in their minds. Over time these concerns have lessened to some degree as families have been reassured by the migration success of local women celebrated through the enabling and now common technologies of social media. However, in the current survey the comparatively low levels of younger women pursuing the labour migration option shows that these concerns remain a constraining feature ().

Experience has also shown that a more readily acceptable pathway to labour migration opportunities, especially for young women, has arisen through the phenomena of online romances and subsequent betrothals with Fataluku male migrants based in the UK. Over time many of these engagements have led to fast-tracked marriages in Lautem and Dili, with the blessings of parents, during brief return visits to Timor-Leste. Soon after the marriage exchange formalities and feasting have been successfully celebrated, the young couple depart with Portuguese passports in hand, for their new life in Britain (see McWilliam Citation2020).

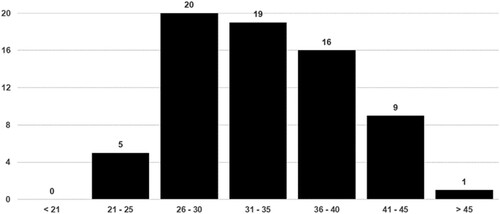

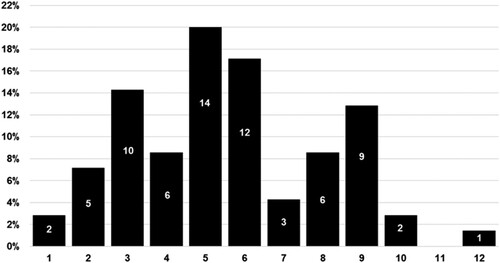

shows the age of respondents in the survey, indicating that around 62 per cent of returned migrants are under the age of 36, highlighting the reality that most of the labour migrants are typically younger with fewer family responsibilities at home. However, an older cohort of returnees in their forties is partly explained by respondents who had returned a decade earlier and the length of time that they had worked in the UK—in this case for a decade or more (5 respondents). But it is also the case that older individuals historically have been represented in the informal labour migration to the UK, motivated like everyone else to secure a source of savings capital to support their families in the absence of local employment opportunities.

Work in the United Kingdom

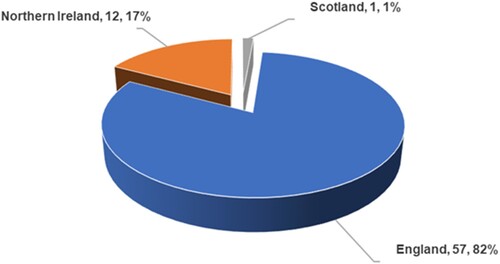

One of the characteristic aspects of Fataluku labour migration to the UK is that familial relationships are a key enabling connection that allow new migrants to imagine the possibility of travel and then to integrate rapidly into the completely novel environment of Britain. Close relatives who are already established in work overseas typically provide support including temporary accommodation and even access to employment opportunities once settled in. These facilitating mechanisms have made the global transition from Los Palos or Dili to the radically different environment of Britain, relatively seamless. Over the last two decades, this familial channelling of aspiring workers has been the dominant mechanism for transnational migration and has meant that Fataluku migrants have tended to congregate in certain well-established localities. graphs the destinations of the survey participants. Northern Ireland has been a favoured destination since the early 2000s, particularly for shift work in meat packing factories for export destinations and as a place where jobs can be secured without fluency in English. Towns like Dungannon and Port-a-Down still have significant Timorese populations (up to 3000, see Wigglesworth and Boxer Citation2017) and feature in the locations mentioned by respondents ().

Cities and towns in England have been the primary residential focus for most of the migrants, mainly because they offer more work opportunities; however, this pattern is also an artefact of historical circumstances that date to the origins of the UK migration in the 1990s when Timorese political asylum seekers were escaping persecution following the Santa Cruz massacre in Timor-Leste and found refuge, support and work in centres such as London, Oxford, Liverpool and Peterborough (McWilliam Citation2020). In the survey, 31 respondents (44 per cent) nominated Oxford as their place of residence and work in the UK, with major centres such as London, Birmingham, Leeds, Manchester and Plymouth absorbing another 18 respondents (25 per cent). One of the patterns of Timorese migration to the UK that has emerged over two decades is a gradual dispersal of migrants from well-established or favoured centres to a wider range of other cities and towns. This trend was initiated by the impact of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC 2008–2009) and the subsequent economic downturn where jobs were lost or shifts reduced, and migrants had to seek out lucrative options elsewhere. The value of social media and Internet that facilitates communication and awareness of diverse job opportunities in different localities was another vital factor in this process.

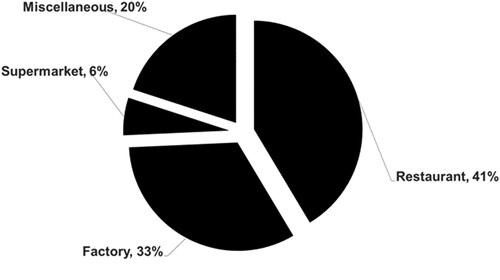

Consistent with other surveys of Timorese labour migration, the majority of employment categories secured in the UK involve low-skilled manual labour. shows the main types of work reported by the respondents. The largest grouping is the food services sector, mainly restaurants and working as dishwashers and cooks. Some migrants also find work in hotels and student accommodation kitchens in Oxford and other university towns which often pay well above the minimum wage. Restaurants also typically have high turnovers of staff and multiple shifts that provide work opportunities and often the benefit of free meals and food. The other major employment category among respondents is ‘factory work’, such as Northern Ireland in the meat-packing factories, the large BMW factory in Oxford and big box-packing factories for supermarket chain distribution centres such as Tesco, Morrisons and Sainsbury’s. Other types of work include diverse opportunities in aged care, housekeeping, supermarket stacking, cleaning and nursing support work in hospitals.

For two decades, Timorese migrant workers travelling on Portuguese passports had direct and open access to residence and work in the UK, taking advantage of the agreements on a free movement of labour within the European Union (EU). Unlike other jurisdictions, their capacity to continue working in the UK was unrestricted, limited only by their ability to sustain separation from home and family in Timor-Leste. illustrates the number of years spent pursuing labour migration in the UK by the survey respondents. The common length of time away was between 3 and 6 years for 42 respondents or 60 per cent of the sample. However, a significant group (18, or around 25 per cent) spent at least 8 years overseas.

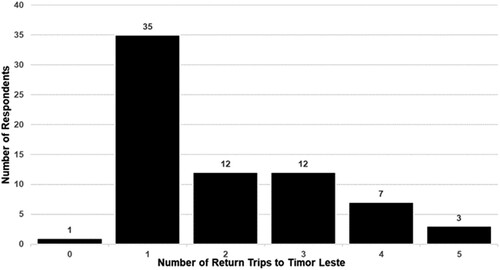

For most of the Fataluku labour migrants, and especially those who maintain families in Timor-Leste, feelings of homesickness and the need to return to Timor-Leste and their households of intimate familiarity is strongly felt. As the responses highlight, it had become common practice for labour migrants to make periodic return visits ‘on holiday’ in Timor-Leste to visit friends and family before heading back to replenish their savings. Cut price airfares (USD1500 return) made the otherwise daunting 36-hour journey, via Dubai and Bali to Dili, an affordable option. In the survey, a majority of respondents made at least one return trip to Timor-Leste during the time they were away (see ). Broadly speaking there is a general correlation between years spent working overseas and the number of times return visits are undertaken.

Return visits are a time of emotional celebration when the prodigals reunite with their families and soak up all the local attention and news of home. This is also usually an opportunity to pass on savings for family support, often hand carried from England, or for initiating various planned projects such as house repairs and new construction, purchasing a motorbike, as well as participating in the ritual life of the village with its ever present round of weddings, funerals, end of mourning events (T: kore metan) and religious gatherings.

Remittances and Family Obligations

A key motivation for the popularity and expansion of the informal labour migration was, and remains, the prospect of earning comparatively high incomes (£250 per week—compared to USD25 in Timor) from low-skilled factory and restaurant work, supermarket shelf stacking and aged care employment. There was, and still is, simply nothing comparable in Timor-Leste and this has meant that by living frugally in the UK, pooling resources and sharing group accommodation arrangements, a diligent migrant worker could quickly generate substantial savings, a portion of which could be regularly remitted back to families in Timor. This was common practice among the Fataluku labour migrants who reported a range of regular cash transfers to relatives and family via Western Union, the principal financial platform for these transactions into Timor-Leste (see also Wigglesworth and Fonseca Citation2016, 7).

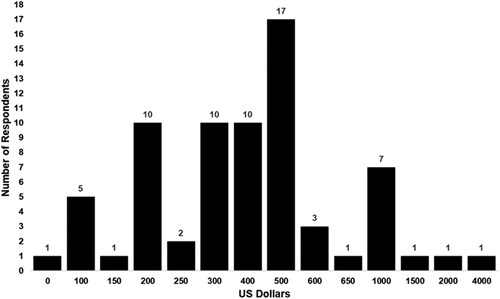

The table in highlights the remittances to Timor-based households and the varying dollar amounts sent on a regular basis. The majority (70 per cent) of respondents transferred between USD 200–500 monthly, with a smaller number (14 per cent) reporting sending as much as USD1000 or more a month. While it is not possible to verify the scale of these figures, the key point is that virtually all labour migrants were committed to making regular cash transfers to home out of savings generated from their regular pay checks in the UK. It formed part of their commitment to support family members' ongoing livelihood needs.

The funds transferred from the UK to families in Timor-Leste are generally utilised for a range of immediate household and family expenses. Consistent with findings from other surveys (see McWilliam and Monteiro Citation2019; McWilliam Citation2020), a commonly expressed use of remitted cash is to finance daily consumption needs, especially food supplies and basic domestic requirements. The great majority of participants mentioned this explicitly and framed it in terms of family support—‘attendé necesidade familia’. The practice effectively replaces the need for family recipients to cultivate their own food crops and instead enables the purchase of imported rice. The downside of course is that this kind of support only lasts while the migrant family member remains in employment in the UK.

Other frequently mentioned uses of the remittance flows include building a new house (T: harii / halo uma), mentioned explicitly by 19 respondents (27 per cent), and providing financial support for siblings' and children’s schooling costs (alin sira nia eskola), 16 respondents (around 23 per cent). These figures, however, are likely to significantly underestimate the actual use of remitted funds for these purposes, given that the great majority of respondents did not specify the breakdown of expenditure and simply mentioned continuing financial support for their immediate family. This can be inferred because the renewal of housing stock in places like Los Palos and surrounding settlements has been a highly visible feature of the post-Independence landscape. Most of this construction has been funded by migrant remittances, and the ‘building boom’ in Los Palos and surrounding villages from 2011 has dramatically changed the appearance of the urban and built environment in that precinct (McWilliam Citation2012). Construction provides one of the very few thriving, domestic economic and employment opportunities in the district, offering regular work and profitable investment projects (e.g. carting sand and cement, concrete brick manufacturing (pataco), window frames and timber supply).

Support for children's and or siblings’ education is another important priority for many Fataluku households, and there is a strong obligation for older siblings who have taken the labour migration option to help fund their younger siblings' school fees and related costs. Although migrant work in the UK has been very popular among young Fataluku for the cash and experiences it offers, it is also recognised that the work available is usually menial and relatively low skilled with little prospect for training and professional development. For this reason, many parents see education beyond secondary schooling as a valued and prospective basis for improved life chances.

Finally, the notion of supporting home-based families while working overseas extends to many of the lifecycle events and transitions—births, marriages, deaths and funerals (collectively known as matters of life and death: lia moris no lia mate)—that occur regularly in the social lives of close-knit households and their affinal networks of relation and obligation. These events are important occasions when families publicly confirm their ties and obligations to one another through reciprocal gift exchange and feasting for participants (McWilliam Citation2011). The immediacy of Internet connections between Timor-Leste and the UK ensures that news of important family events can be quickly conveyed to migrant household members, along with expectations that contributions in the form of cash transfers are forthcoming.

Savings, Employment and Investment for Returned Migrants

A further aspect of the labour migration experience has been the common practice among migrants to try and save as much of their earnings as possible so they can build a capital fund for a range of projects and livelihood support once they return to Timor-Leste. In some cases these funds have simply been used to support their own living costs for an extended time, at which point they would seek to return to the UK and re-engage expatriate employment. With this option now largely closed or made much more complicated by new Brexit regulations, savings provide an important source of income or buffer against poverty.

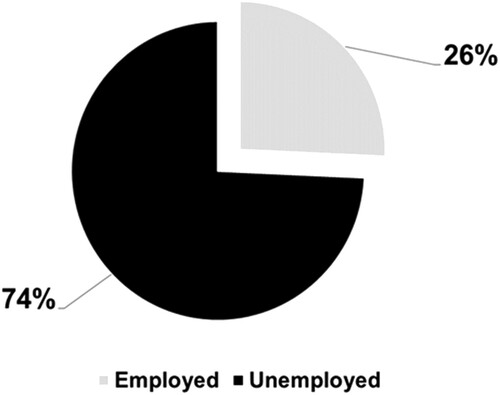

This reality is confirmed in one of the survey questions about respondents’ current employment status and whether they were in work at the time of the survey. Fully three quarters of the sample (53, or around 74 per cent) answered in the negative (see ). Their unemployed status is the result of endemic poor prospects for paid employment in Timor-Leste but also reflects the capacity of many returnees to sustain themselves by drawing on savings over longer periods of time to bolster any income or local support they can garner through temporary forms of paid work or farming activities. In these circumstances, most respondents expressed a desire to return to the UK and rebuild their cash reserves in the familiar pattern of circular migration that was emerging among Fataluku migrants until Covid 19 travel restrictions and Brexit regulations disrupted that option.

A small number of returned respondents (4, or around 5 per cent) mentioned that they had established a kiosk (kios) at their residence in Los Palos or Dili with capital saved from work in the UK. Typically, this involves constructing a small secure structure adjoining or next to the house and stocking it with provisions for sale to members of the community and passing traffic. The kios can provide a small but regular return on investment, usually in the form of food replacement for the family. A further two respondents acknowledged that they were not currently employed, but had, in one case, purchased a tip truck (Colt Diesel) and another had contributed to the purchase of a family mikrolet (minibus) for local transport services (see Viegas Citation2018 for comparison). In these cases, the investments provide varying amounts of revenue flows to support household livelihoods.

A minority of respondents (18, or 25 per cent) confirmed that they were employed in different capacities at the time of the survey in late 2019. A few individuals had found work through government contracts and small-scale commercial trading. The most common category of work comprised transport and construction-related activities as employees or owners investing their savings in a business. Responses include regular work as truck and bus drivers (three respondents) around Los Palos or on return trips to Dili; the purchase of Mitsubishi tip trucks (Colt diesel)Footnote2 for leasing and contract work (three respondents); and the purchase of cement block presses (pataco) for production and sale of bricks into the UK-funded local house construction boom (three respondents). Another three respondents mentioned investing their savings into auto workshops and motor maintenance businesses. One young woman who had resumed her studies at the Dili Institute of Technology (DIT) upon returning from England also invested with her brother in two motor maintenance businesses in Dili and Los Palos; their choice, once again, reflecting the perceived economic opportunity that comes with an increasing number of vehicles on the road and a reliable cash flow from servicing them.

The capacity for returned labour migrants to invest in a range of income-producing businesses is directly related to their earlier commitment and resolve to save a significant portion of their incomes while working in the UK. To understand just how significant this can be, one of the survey questions asked specifically about the amount of ‘savings’ (as distinct from remittances) generated by migrants during their time overseas.

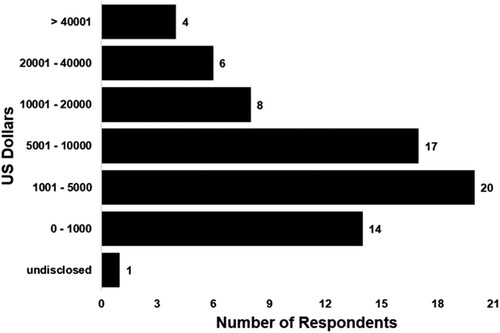

The answers reveal some surprising results and highlight both the extraordinary economic opportunity that the labour migration experience has conferred on some diligent savers, and perhaps the lost opportunity for others to secure their futures. Wide variations in the time spent working in the UK by different migrant respondents evidently influences the scope for savings. For example, one survey respondent spent just 18 months in the UK while another accumulated 12 years of residence. presents a summary of these results. The great majority of returned migrants had only managed to put together relatively modest levels of personal savings—between USD1000 to 10,000—during their time away (52, or around 74 per cent of respondents). However, a smaller cohort returned with much larger savings funds—up to and over USD40,000—much of which has subsequently been directed into income-producing investments in Dili and or Los Palos with a portion kept aside to cover everyday living expenses. The figures highlight the common experience of most migrants: the cash benefits from working and saving in the UK are highly beneficial while working but do not commonly translate into substantial savings over time.

Reflections on the UK Migrant Experience

In concluding the survey, respondents were asked two final questions: (1) What made them contented, happy (haksolok) or otherwise as the result of their UK labour migration experience; and (2) Would they be interested to return to the UK to take up employment again? The most frequent response to the first question concerns the ability to earn regular and comparatively lucrative cash incomes. Fully 43 respondents (61 per cent) mentioned the money that they earned (kontenti ho osan), with another 13 (around 18 per cent) referring to the paid work they were able to secure. The responses highlight the centrality of income-earning opportunities—a platform for saving—as the principal motivation for young Fataluku to undertake the travel. But a range of broader experiences were also reflected upon, such as the novelty of meeting new people and living in a different culture, enjoying the sense of helping their families (financially) and experiencing new types of work and other opportunities.

Conversely, returned migrants commonly reflected on the negative or difficult aspects of migrant life, namely their struggles with being ‘separated from their families’ (do’ok husi familia). This phrase reflects the complex and heartfelt sense of separation from close-knit friends and family networks, as well as the familiar patterns of everyday life and comfortable cultural fluency in Timor-Leste which seem very far away when living in a cold and distant England or Northern Ireland. The sense of ‘working’ for one’s family, or even as a broader contribution to stronger economic development, forms part of a shared narrative of (self)-sacrifice by which participants seek to frame their efforts overseas.

A final question sought information on respondents’ intentions to return to the UK and take up the migrant labouring life again. The majority (61, or 87 per cent) expressed the strong view that they did indeed plan to return to the UK, highlighting the extraordinary impact of the labour migration experience on so many participants in the global adventure. It is also a striking commentary on the continuing absence of alternative financially attractive local work opportunities in Timor-Leste; work that might persuade them to stay on in country.

The shared intention to again pursue transnational work opportunities also reinforces the familiar pattern of circular labour migration that emerged over time among experienced offshore workers. After some years away, many enjoyed varying periods of time back home, to be with their children, catch up with family and friends, and spend down their savings until they needed to return to the UK to replenish their savings and begin the cycle again. As it happened, however, the advent of Covid-19 and the shutdown that followed made that choice redundant, at least for the time being. Many would-be return migrants found themselves stranded in Dili or Los Palos with little prospects of either returning to the UK or securing domestic employment.

Labour Migration and Change

Covid 19 and the global shutdown of international airline travel brought an abrupt end to Timorese transnational labour migration to the UK. Since then, the prospects for resumption have been further threatened by the enactment of the much-delayed Brexit regulations that were implemented on 31 January 2020, but a further transition period was negotiated which extended the timeframe for full compliance until 31 December 2020. This ruling has radically altered the migration landscape in the UK for non-citizens, with the main effects being to restrict open access for European passport holders to work in the UK labour market and to limit access to skilled migrants. The ruling clearly applies to aspiring Timorese labour migrants travelling on Portuguese passports (the vast majority), who have no previous experience or demonstrated connections with the United Kingdom. Their ability to negotiate access to work in the UK is now very much compromised and much more difficult than before.

This possibility of exclusion had been foreshadowed since the surprise result of the 2016 Brexit vote and, arguably, provided an added incentive for a growing number of young Timorese eager to secure their own slice of the benefits on offer (see McWilliam and Monteiro Citation2019). Either way, the combined effects of these momentous developments signal the end of the flourishing Timorese UK labour migration experience or, at least, a significant reappraisal of its future. At present there remain thousands of Timorese-origin migrant workers still living in the UK, who were given the possibility of negotiating the regulatory pathways to secure their residency and employment status—primarily by registering their ‘settled status’ in the UK (prior to the 30 June 2021 deadline).Footnote3 But just how many managed to register by the deadline and secure their future status remains unclear, with some reports suggesting that many young Timorese were unaware or oblivious to the requirements and may have found themselves losing their entitlements to remain in the UK (Webster Citation2021). The combined effects of these developments have substantially changed the terms of labour migration for aspiring Timorese workers and caused a major disruption to the bounteous flow of remittances enjoyed by many thousands of rural and urban households in Timor-Leste.

Ironically, as one labour migration door closes, another one opens, and for aspiring Timor-Leste transnational workers, new opportunities for temporary labour migration have opened up in neighbouring Australia over the last decade. The expansion of the Australia-based Seasonal Workers Program (SWP) to Timor-Leste temporary workers in 2012, and more recently the Pacific Labour Scheme (PLS) in 2019, have offered recurring and longer-term employment opportunities for growing numbers of aspiring Timorese labour migrants. Both schemes are bilateral programmes managed through cooperative arrangements between the Government of Timor-Leste (SEPFOPE) and Australia (specifically, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade) (see Curtain and Howes Citation2020, 48–52). The schemes offer a range of time-based contracts with approved employers focused on agricultural harvesting across rural and regional Australia, and a range of semi-skilled occupations in areas of labour demand such as agriculture, hospitality and aged care. In recent years, the number of Timor-Leste participants in these schemes has grown consistently from a low base up to 1000 participants (see Wigglesworth and dos Santos Citation2018). In 2022 the programmes are to be folded into one umbrella programme known as the Pacific–Australia Labour Mobility (PALM) scheme, with overall numbers boosted by 12,500 participants.Footnote4 Labour shortages across Australia, particularly in the broader agricultural sector, represent a significant opportunity for youthful Timorese to pursue temporary and circular labour migration to generate a sustained source of income, savings and remittance payments to support households and source communities in Timor-Leste while building a platform for personal skills development (see Wu Citation2021). These are positive developments in a context of continuing poor employment prospects in Timor-Leste, especially for young graduates who confront the debilitating impacts of the oil-based economy on which the fledgling nation continues to depend (see Scheiner Citation2019). The previous experience and example of informal labour migration to Europe and the UK, especially the ways in which savings and remittances have been deployed in Timor-Leste source communities, is likely to be strongly indicative of the expenditure patterns of new Timorese labour migrants working in Australia.

Concluding Thoughts

The global reach of labour migrants is a distinctive and pervasive feature of the modern era; one that speaks to the widespread human search for a better life despite the risks. Success is not guaranteed however, and the increased income that may be gained by travelling away is often accompanied by feelings of isolation and separation from family, friends and the cultural familiarity of social life back home. These concerns are also reflected in the responses of the 70 migrant returnees who participated in this survey, and who value the experience, material benefits and knowledge they have accrued overseas. Many also frame their motivation to work away as a desire and aspiration to build a better future for their families and, by inference, the nation. Like their forebears and relatives who sacrificed themselves for national liberation and their children’s future in the struggle for independence, many labour migrants adopt a similar kind of language of sacrifice to characterise their own efforts pursuing employment in distant lands. In the process they reaffirm their own forms of struggle, week by week, in the far away drudgery of shift work and the factory line, accumulating the necessary financial resources to fulfil the promise of a better future (see also Bexley Citation2009).

Two decades on from the historic achievement of sovereign independence, the process of nation-building and the promise of economic prosperity remains a work in progress for Timor-Leste. Exporting the labour of its youthful population to generate income in a variety of largely lower skilled, minimum wage and temporary occupations overseas is no substitute for sustained domestic economic investment, enterprise and development at home. But as this survey has illustrated, and like the experience of most of its regional neighbours, there is much value to be gained from temporary labour migration, not least for the Fataluku participants and their dependants who have enjoyed substantially improved living standards and security in the process.

The material benefits of migration savings and remittances have been most visibly observed among Fataluku communities in Lautem and Dili, especially the widespread housing boom and proliferation of new buses, trucks and motorbikes, computers and mobile phones. At the same time, the increased financial prosperity of many households has seen an intensification of more traditional patterns of exchange, obligation and memorialisation among extended kin networks. These practices include elaborate weddings and bridewealth displays, more expensive tombs of family members, and greater attention to the reconstruction of ancestral graves, especially those (martyrs and herois) who died in the cause of liberation (Kent and Feijó Citation2020). There has also been a renewed focus on the rebuilding of ancestral cult houses (le-ia valu :: lei teinu) to install the sacrificial hearth (aca kaka) and lineage sacra, providing a ritual focus for lifecycle transitions and a gathering place where agnatic members can offer sacrificial gifts to House ancestors in return for their blessings and spiritual protection (McWilliam, in press). In these and other ways transnational labour migration has transformed the lives of many Fataluku families while providing the means to reinforce the customary protocols and obligations of tradition. Fataluku have become, what I call, ‘customary moderns’ (McWilliam Citation2020), embracing a modernity that is full of new possibilities but inevitably qualified by customary restraint. The composite phrase, customary modern, expresses subjectivities that are at home in both worlds while negotiating the oftentimes conflicted priorities between personal aspirations and group responsibilities (McWilliam Citation2020, 139).

Acknowledgements

Assistance in the development and conduct of the survey in Timor-Leste was provided by Carmeneza dos Santos Monteiro and NGO Fundamor. I thank them for their contribution and to Desmon Ginting for editing work on tables and graphs. I thank an anonymous reviewer for their comments.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 I have estimated that Fataluku labour migrants made up at least 30 per cent and possibly as many as 40 per cent of the participants at the time (McWilliam and Monteiro Citation2019, 44).

2 Mitsubishi Colt Diesel tip trucks have been commonly purchased and shipped out of Surabaya in eastern Java (Indonesia). Costing around USD24,000 landed in Dili, by 2014 the trucks had become a common sight around Los Palos and were used to support the house construction boom. In the early days it was possible to repay the wholesale cost of the trucks in 12 months if leased consistently through the year.

3 By officially registering, EU migrants received the right to work, rent housing and access to the National Health Service (NHS). If migrants had worked for less than five years, they were given ‘pre-settled status’ which would convert after 5 years of residence (see Webster Citation2021).

References

- Bexley, A. 2009. “Getting an Education: Links to Indonesian Schools and Universities Remain Strong in East Timor.” Inside Indonesia 96 (April–June), www.insideindonesia.org/getting-an-education.

- Curtain, R., and S. Howes. 2020. Governance of the Seasonal Worker Programme in Australia and Sending Countries. Canberra: Development Policy Centre, ANU Crawford School of Public Policy. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2020-12/apo-nid309985.pdf.

- Hugo, G. 2009. “Best Practice in Temporary Labour Migration for Development: A Perspective from Asia and the Pacific.” International Migration 47 (5): 23–74.

- ILO (International Labour Organization). 2016. Structural Transformation and Jobs in Timor-Leste. Dili: ILO, Timor-Leste.

- Kent, L., and R. G. Feijó, eds. 2020. The Dead as Martyrs, Ancestors and Heroes in Timor-Leste. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- McKay, D. 2007. “‘Sending Dollars Shows Feelings’: Emotion and Economies in Filipino Migration.” Mobilities 2 (2): 175–194.

- McKay, D. 2016. An Archipelago of Care: Filipino Migrants and Global Networks. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- McWilliam, A. R. 2011. “Exchange and Resilience in Timor-Leste.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (JRAI) 17: 745–763.

- McWilliam, A. R. 2012. “New Fataluku Diasporas and Landscapes of Remittance and Return,” in “Nation-Formation, Identity and Change in Timor-Leste,” special Issue, Local-Global: Identity, Security, Community 11: 72–85.

- McWilliam, A. 2015. “Rural-Urban Inequalities and Migration in Timor-Leste.” In A New Era? Timor-Leste After the UN, edited by S. Ingram, L. Kent, and A. McWilliam, 225–234. Canberra: ANU Press.

- McWilliam, A. R. 2020. Post-Conflict Social and Economic Recovery in Timor-Leste: Redemptive Legacies. London: Routledge.

- McWilliam, A. R., and C. Dos Monteiro. 2019. “Fataluku Labor Migration and Transnational Care in Timor-Leste.” Indonesia 109 (1): 41–54.

- National Directorate of Statistics. 2016. “Former Members of Private Households Living in Portugal, or Other European Countries, by Sex, Municipality, and Administrative Post of Household.” Table 21.e of the 2015 Timor-Leste National Census.

- Pinto, C., and M. Jardine. 1997. East Timor’s Unfinished Struggle: Inside the Timorese Resistance: A Testimony. Boston, MA: South End Press.

- Reis, J. S., L. D. Cabral, and J. V. Valentim. 2016. Impaktu Traballador Iha Ingleterra no Norte Irlandia be Prosperiedade Familia iha Munisipiu Lautem, Final Report. Jakarta: Asia Foundation, Jakarta, with support of PLG (Policy Leaders Group) and Australian Aid.

- Rigg, J., and P. Vandergeest. 2012. Revisiting Rural Places: Pathways to Poverty and Prosperity in Southeast Asia. Singapore: NUS Press.

- Scheiner, C. 2019. “After the Oil Runs Dry: Economics and Government Finances.” In The Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Timor-Leste, edited by A. McWilliam and M. Leach, 87–109. London: Routledge.

- Schuaib, F. 2007. Leveraging Remittances with Microfinance: Timor-Leste Country Report, 1–24. Brisbane: The Foundation for Development Cooperation (FDC).

- Silva, C. da. 2013. RENETIL Iha Luta Libertasaun Timor-Lorosa’e: Antes sem Título, do que sem Pátria! Dili: RENETIL.

- UNICEF. 2018. Quality Education: Realising Rights for Quality Education for all Children. https://www.unicef.org/timorleste/quality-education.

- Viegas, S. de M. 2018. “Looking Back Into the Future: Temporalities of Hope among the Fataluku (Lautém).” In The Promise of Prosperity: Visions of the Future in Timor-Leste, edited by J. Bovensiepen, 173–188. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Webster, Eve. 2021. “UK’s East Timorese Population Faces Loss of Rights after Brexit.” The Guardian, June 28. Accessed November 7, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/27/uks-east-timorese-population-faces-loss-of-rights-after-brexit.

- Wigglesworth, A., and L. Boxer. 2017. “Transitional Livelihoods: Timorese Migrant Workers in the UK.” Paper presented at the Australasian Aid Conference, Canberra, February 15–17. https://devpolicy.org/2017-Australasian-Aid-Conference/Papers/Wigglesworth-BoxerTransitional-livelihoods-Timorese-migrant-workers-UK.pdf.

- Wigglesworth, A., and A. B. dos Santos. 2018. “Timorese Migrant Workers in the Australian Seasonal Worker Program.” Paper presented at the Australasian Aid Conference, Canberra, February 12–14. https://devpolicy.org/2018-Australasian-Aid-Conference/Papers/Timorese.migrant.workers.in.SWP-Wigglesworth&dosSantos.pdf.

- Wigglesworth, A., and Z. Fonseca. 2016. “Experiences of Young Timorese as Migrant Workers in Korea.” Paper presented at the Australasian Aid Conference, Canberra, February 10–11.

- Wu, A. C. W. 2021. “Migration, Family and Networks: Timorese Seasonal Workers’ Social Support in Australia.” Asia Pacific Viewpoint 62 (3): 313–330.

- Young, P. 2013. Effects of Importing Maize and Rice Seed on Agricultural Production in Timor-Leste, Commissioned Study for the Seeds of Life Program. Dili: Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries.