Abstract

Being Indonesian is experienced differently depending on age and generation. In 1970 senior Nuaulu men had been young adults under Dutch colonialism. Those who in 2020 occupied key politically influential positions grew up in an independent Indonesia. Conflict with state agencies over resources, plus practical difficulties arising from non-recognition of their religion, have been obstacles to national integration. However, the impact of Christian—Muslim conflict between 1999 and 2003, and the opportunities afforded by reformasi and otonomi daerah, emboldened younger Nuaulu to balance being good Indonesian citizens with the pursuit of a ‘traditionalist pathway to modernity’. This paper charts how educational access and the emergence of youth culture and the category pemuda impacted after 1990 on the organisation of government work groups and appropriate forms of reward. These events threatened traditional authority and yet would ultimately provide a means for achieving territorial autonomy and state recognition for their beliefs and practices.

Introduction

Being Indonesian is experienced differently depending on age and generation. When I first arrived on Seram, in early 1970, my Nuaulu interlocutors included senior men who had been young adults under Dutch colonialism, who had been caught up in the Second World War, and who had fought as RMS (Republik Maluku Selatan) auxiliaries in an attempt to secede from the new Jakarta government following independence. Moreover, Nuaulu had a long-standing historical allegiance to the Muslim domain of Sepa before becoming subject, successively, to the Dutch East India Company, the government of the Netherlands East Indies and the Indonesian state. Indeed, the incorporation of the coastal Muslim polities of south Seram into the colonial state transformed the alliance between Nuaulu and Sepa into one of effective subjugation, as the Dutch sought to consolidate their power and administer territory and people. An independent Indonesia was initially content to accept the administrative status quo they inherited, but over time began to micro-manage local affairs through an increasingly complex heterarchy.

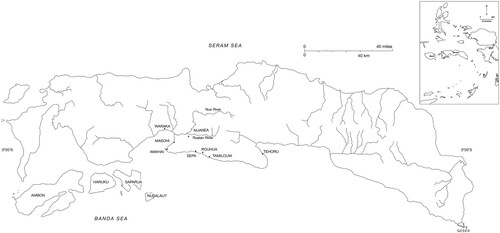

The Nuaulu by 2015 numbered something above 2000 individuals located mainly within separate settlements within the desa of Sepa, and in the predominantly Nuaulu desa of Nuanea around the confluence of the Nua and Ruatan rivers, in the Amahai subdistrict (kecamatan) of south Seram (). I explain here how their relationship with the concept of Indonesia has always been nuanced, tangential, and pragmatic. A younger generation—those who in 2020 occupied key politically influential positions—have grown up in an independent Indonesia, and Indonesian institutions have increasingly and ever more effectively shaped their behaviour and attitudes, seemingly making their status as Indonesian nationals easier to reconcile with other identities. However, conflict with the state and its agencies over land and resources, mainly in the context of transmigration policy, plus difficulties experienced in the labour market due to non-recognition of their ritual practices as religion, have continued to be obstacles to national integration. The negative experiences of communal Christian–Muslim conflict between 1999 and 2003 (Ellen Citation2004), and the opportunities afforded by reformasi (the post-Suharto reform movement) and otonomi daerah (local autonomy), have stimulated a younger generation to balance being good Indonesian citizens with the pursuit of a ‘traditionalist pathway to modernity’. This latter is shorthand for some ideas that I introduced and developed in a previous monograph about Nuaulu in the ‘New Indonesia’ (e.g. Ellen Citation2018, 197) to explain how after initial resistance to certain features of state intrusion and civic and economic modernism, and attempts to modify practices to conform with state norms and expectations, demographic and other developments in the wider political sphere led to a recognition that in order to be modern Indonesians it was not necessary to concede on certain matters of traditional practice. Instead, it was asserted that these might be integrated into a modernist vision and used to their advantage. In its oxymoronic ambiguity the phrase resonates with the state-level political assertion of ‘unity in diversity’.

I pay particular attention to how an emerging youth culture and formal education featured in these developments between 1980 and 2015, first threatening to destabilise traditional authority while integrating younger Nuaulu as cultural Indonesians, and yet ultimately providing the means for achieving some degree of territorial autonomy and state recognition for their beliefs and practices. The argument begins with language, but progresses through a consideration of how, since 1970, state power has intruded as administrative infrastructure has grown, how the market has been a force for economic and cultural integration, and how all have contributed to the context in which the category ‘youth’ (pemuda) has acquired political consequences for readjusting Nuaulu identity vis-a-vis the state.

Becoming an Indonesian Speaker

The history of nation-forming is virtually everywhere associated with promotion of a shared language through which the state can communicate with its subjects. Often failure to learn the language of the state and to persist using local languages is penalised. The situation in Indonesia was more complex than in most. Malay had been the language of intellectuals, commerce, and independence fighters as well as the language of much colonial administration. For this reason it had achieved some degree of standardisation by 1947 (Paauw Citation2009). In the Moluccas, Malay had been spoken for some centuries as a pre-European trading language, replacing local languages in some areas and leading to the formation of some distinct local Malay dialects. In Ambon, Lease, and coastal parts of Seram, Ambonese Malay (Collins Citation1980) had become a strong speech community long before Indonesian independence. Its replacement with modern Indonesian, a version of Malay (Bahasa Indonesia: literally the language of [those who are politically] Indonesian) was to be a slow and incomplete process. Moreover, the secessionist RMS continued to use an unreformed Malay of the kind fostered under the Dutch colonial dispensation (Bahasa Melayu Maluku), as well as its associated orthography, using both Roman and modified Arabic (Jawi) scripts (Ellen Citation1997).

Although many local languages on Seram were disappearing during the early post-colonial period or were critically endangered (Florey Citation2005), some because of pre-colonial political and commercial factors had themselves become vehicular languages and to an extent competed with Ambonese Malay and Indonesian. In the Nuaulu area (south central Seram), the main vehicular language for many people in the immediate post-independence period was Sepanese. This language was spoken in Sepa and Tamilauw, the two largest settlements along the south coast between Amahai and Tehoru. In 1970 almost all adult Nuaulu were functionally competent in Sepanese, and many also had varying degrees of competence in other local languages in addition to Nuaulu. However, growing involvement in the cash economy (from one based mainly on subsistence swiddening, sago, and hunting), more frequent contact with non-Sepanese speakers through immigration (mainly from Sulawesi), and increasing participation in state institutions required greater competence in Malay or, even better, Indonesian. In 1970 there were still people, some adult men but mainly women, who had only rudimentary Malay and no competence in spoken Indonesian. Learning Indonesian only effectively came with schooling. Up until then many Nuaulu were competent in spoken Ambonese Malay, the use of which did not convey state allegiance. Indeed, as the language of the RMS during the 1950s and 1960s it could mark them out as politically disloyal. Moreover, it is not language alone that defines someone as an Indonesian speaker but also paralinguistic features that accompany speech. For example, there is a formal style of oration adopted by politicians, which respects state honorifics and incorporates acronyms, that is specifically expected of government officeholders and when communicating with outside local administrative cadres on official occasions.

Indonesian language competence and basic literacy massively improved with the introduction of systematic schooling, other kinds of state penetration, and the rise of electronic media (first radio and television and then mobile phones and social messaging). While spoken Ambonese Malay competence persists, truncated Indonesian and various Ambonese Malay idioms have been adopted during the twenty-first century for social media text messaging. Indonesian language competence had immediate consequences, some unexpected (such as graffiti and ad hoc protest signs), but overall increased the effectiveness with which Nuaulu could engage with the state.

The Intrusion and Establishment of State Infrastructure

Hierarchies of Political Administration

In large parts of the Moluccas during the late colonial period the Dutch had run their administration through a form of indirect rule, mainly recognising local rulers by conferring upon them Malay language titles legitimated through official letters of appointment (e.g. Ellen Citation1997). From the late nineteenth century until 1949 Nuaulu were formally subject to the Raja of Sepa, whose position was recognised by the Dutch. The Raja of Sepa in turn recognised three Nuaulu titles: (N) ia onate aia, ia onate ankarua and ia onate ankatika,Footnote1 in order of decreasing precedence. Each title was held by the head of a particular clan and inherited through the male line. The ia onate aia was effectively the Nuaulu Raja, resident in Aihisuru and also primus-inter-pares for all Nuaulu, the ia onate ankarua was the head of the settlement in Rouhua and the ia onate ankatika of Bunara. During the immediate post-independence period all these titles were translated as bapak jou (literally ‘father lord’), kepala pemerintah (government head), kepala kampung or later kepala dusun (both village head). Use of such titles tended to flatten out any implication of hierarchy or precedence in government-recognised positions in different traditional domains, and because of this the titles often became the subject of disputes between various officeholders of different clans. Nevertheless, the positions continued to be inherited, including that of wakil (deputy village head), which in Rouhua was held by the clan Matoke. There was also by 1970 an appointed kepala- (or pemuka-) gotong-royong in Rouhua whose role was to organise government-dictated work such as path clearing, a position formally encouraged and instituted through a kind of state philosophy under Sukarno and periodically revived by subsequent governments (Koentjaraningrat Citation1967; Bowen Citation1986). Kepala gotong-royong positions have existed intermittently in Nuaulu villages ever since, revived every so often following local government exhortations or directives to undertake specific work.

Between 1970 and 2000 there were three successive kepala kampung in the large Nuaulu village of Rouhua east of Sepa, none of whom were literate. The problem was partly overcome by the appointment of a sekretaris in the 1980s, who was both literate and functionally comfortable in standard Indonesian. It was the first sekretaris of Rouhua, Sonohue Matoke, who eventually became kepala kampung in 2000. A similar pattern emerged in other Nuaulu settlements, and with the establishment of Nuanea from migrants from the old villages around Sepa, the decision was taken to separate traditional leadership involving ritual responsibilities from the secular government head of the desa.

Although from 1949 there had been a new state bureaucracy, Nuaulu villages continued to be immediately subject to the Raja of Sepa, who now also held the government title of kepala desa (village head). Thus, positions in the lower echelons of the Indonesian administrative structure were coterminous with the old colonial arrangement through which the Raja of Sepa had been subject to the Dutch authorities. In turn, Nuaulu government heads were expected to show their fealty to the Raja by attending various festivals, both religious and secular, and meetings convened by the Raja in Sepa. To reciprocate, the Raja would be invited to major Nuaulu festivals—such as the topping out of a new (N) suane (Ambonese Malay baileo, village ritual house), or new clan ritual house. From an Indonesian angle, the Raja was simply the instrument of the power of the state, but from a local angle the relationship was complex, complementary, and ambiguous. Often described as a relationship between older and younger siblings (adik-kakak), the older sibling in this case was not the official governmentally recognised superordinate authority, namely the Raja of Sepa. Rather, in mythological and cosmological terms, the older sibling was Nuaulu, the forebears of all Muslim Sepanese belonging to autochthonous clans. Nuaulu were seen as the original people whose rights to territory in the interior were still recognised in shared customary law; recognition, if you like, of the status of Nuaulu as indigenous without invoking the discourse of indigeneity. In return, Nuaulu put their trust in the Raja of Sepa to protect their interests and would respect his authority as a channel for edicts and requests coming from either the colonial or post-colonial government. There was therefore an historic pact between Nuaulu and the Raja of Sepa to protect and assist each other, which went back at least to the period of the Dutch wars of the late seventeenth century, the earliest recorded moment when Nuaulu and Sepa united against outsiders (Ellen Citation2018, 15–17). This alliance was revalidated, but arguably became more asymmetrical, once Nuaulu were encouraged to move from their mountainous clan hamlets in the latter part of the nineteenth century and concentrated in settlements around Sepa (Ellen Citation2018, 27–33). This exposed them to more direct observation and control.

Changes in administrative structure under the late New Order began to alter the long-standing relationship between Sepa and Nuaulu. The movement of some clans to new settlements in the Ruatan transmigration zone from the early 1980s upset the pattern. More were to move permanently later in the decade while others commuted to extract resources from what was regarded as ancient Nuaulu territory, but which was now more accessible. By 1990 the village of Aihisuru had moved completely to the Ruatan valley. In response the local subdistrict recognised new kepala kampung positions in the villages of Kilo 9 (Simalouw) and Kilo 12 (Tahena Ukuna), and thereafter a single kepala desa for the new desa of Nuanea formed by merging and extending these settlements and forming a single territory with which resident Nuaulu could identify separately from Sepa, with which relations had deteriorated. Throughout this period, there was also a kepala kampung and a wakil (deputy head) in each Nuaulu settlement remaining in the domain of Sepa and from the 1980s a sekretaris too. As early as the 1970s there had additionally been an attempt by the government to establish hansip units, a kind of unpaid vigilante force of younger men who would patrol villages and deal with minor infringements of the law and socially unacceptable behaviour. In 1973, I noted eleven hansip in Rouhua, and in 1981 nine, with a designated leader (kepala hansip). Between 1998 and 2000 there was also KAMRA, another civilian militia, which people spoke about during my visit of 2003; however, there is no good evidence of Nuaulu recruitment.

Until the 1970s one of the main ways in which the state had demonstrated its presence was through periodic (usually annual) visitations by the local camat (the head of a subdistrict), the next administrative level up from the desa. This was clearly modelled on the colonial pattern of district commissioners progressing annually through their subdistrict. There were similar occasional visits from the bupati at the regency or district level (kabupaten), and periodic police and sometimes military patrols. But not only did the state intrude into the village through its visitations but the village or its representations would also be required to attend meetings called by the camat in Amahai or the bupati in Masohi. Sometimes mass attendance would be expected at Independence Day and similar state celebrations where Nuaulu would participate by performing cakalele dances and taking part in competitive games: public engagements in civic space.

During the colonial period the authority of those individuals granted administrative power by the Dutch was reflected in material culture. Officials were given or expected to wear official uniforms and have other tokens of office. Such practices continued into the post-colonial period, and Nuaulu officials in the 1970s were required to wear a military-style uniform. An even clearer visible statement of the presence of the government at village level was the rumah pemerintah or (N) numa insi, a building from which flags could be flown, where posters with government announcements and slogans could be hung; organisation charts, census results and (later) devolved budgets displayed; and where meetings could be held, visiting state functionaries hosted, and where other guests passing through could spend the night. In the 1970s these were expected to be paid for by the village itself, and in 1971 there was still no such house in Rouhua mainly due to local objections to any building of stone and cement that might anger ancestral spirits. In November 1970 there was even a police visit to Rouhua to take stock of these objections, at which I was present. Eventually, by 1973, the first numa insi of several successor buildings was erected using a combination of local materials (sago palm thatch, and leafstalks for the walling), sawn timber, and cemented limestone for the base.

Adat and State Law

Under Dutch colonial rule, Nuaulu were mostly left to themselves, except when problems bubbled over into spheres where Nuaulu came into conflict with non-Nuaulu. In such cases a kind of generic adat-law would apply, influenced by local legal regimes that Dutch jurists had demarcated. Thus, Nuaulu fell into the Ambon grouping (ter Haar Citation1948, 30). This approach to the administration of justice continued into the period after independence, though on Seram a growing intermixing of many different ethnic groups through transmigration made this increasingly difficult. Apparently, the Raja of Sepa kept a record of Nuaulu hukum adat until destroyed in the sacking of Sepa by RMS guerillas during the 1950s, and by 1990 there was still no written codification of Nuaulu adat. Most disputes that could not be handled within the Nuaulu community (including those involving outsiders) were dealt with by the Raja of Sepa taking into consideration Nuaulu oral traditions. But Nuaulu would also respect and argue in favour of state legal devices when this suited them. Thus the reason provided by Nuaulu in Rouhua for not recognising Utapina Kamama as Nuaulu Raja was that he had been unable to sign the correct surat keterangan (letter of authority) as he had married a woman from Sepa. Reference to adat law was still important where occasional cases came before a magistrate or judge. Thus, Nuaulu from the 1980s onwards have occasionally used courts in cases of land disputes with outsiders. In 1990 Nuaulu themselves were taken to court (and lost) for reselling land at Kilo Duabelas that had already been transacted (Ellen Citation1993, 136–137). In the cases of murder and head-taking that occurred as a result of conflict between Nuaulu and transmigrants during the 1990s, advocates for the defence relied extensively on what was alleged to be Nuaulu customary practice as part of a process of mitigation (Ellen Citation2002). Moreover, the jurisdiction of the police and Indonesian courts was certainly recognised, and individuals would sometimes be handed in to the police in cases of assault or even marital disputes. Police would be summoned to find, for example, wives or husbands who had absconded or gone missing.

Counting Heads: Census and Elections

One visible way in which the Indonesian state made a claim to authority, created a basic resource for administration, and intruded into the intimate physical space of the Nuaulu village during the 1970s and 1980s was for the purpose of the census (Ellen Citation2014). In order for the counting to be undertaken there would first be a visit from state employees who would place wooden signs on each house, recognised as a blok sensus (census unit), while a follow-up visit was necessary to conduct the actual census.

Similarly, provincial and general elections have provided a major national intrusion into the village. Up until the demise of Soeharto voting was straightforward for Nuaulu, government employees (as headmen technically were) being expected to vote for the government block (Golkar), while their immediate families and staff would be expected to follow suit. With the fall of the New Order there appears to have been greater variation and nuance in the way Nuaulu have voted, not least because they have had to select candidates at five separate levels and assemblies. Given that religious identity was a significant basis for voting across Indonesia as a whole in the 2019 election (Mietzner Citation2019), then Nuaulu voters might seem to have been in a quandary. The recognition of their religion is for many the main obstacle to their economic development, so why should they vote for candidates from parties that espouse an explicit religious agenda? But this is to ignore other factors: that some families are actually split by religion, and that more generally there are traditional loyalties (still) to the Raja of Sepa, combined with a pervasive clientelism reflected in links to a variety of bureaucratic, political, and business figures. In line with what Marcus Mietzner has suggested, and casual conversations I have had in the villages, many Nuaulu probably voted for Jokowi Widodo in the presidential election. However, given that it is the district level where much of the budget is spent, and since most Nuaulu, like most other voters, are concerned with basic issues such as roads and electricity, they tend to vote for individual candidates who they perceive most likely to deliver resources or to who they owe favours.

Incorporation Through Economic Development

Neither political administration, ideological inculcation, nor ‘guided’ participatory democracy alone would be sufficient to turn Nuaulu into Indonesians. At every stage political incorporation has been accompanied by integration into a wider market of goods, ideas, and social contacts, and the impact of the state between 1970 and 1998 increased mainly through expansion of the economy. By the late New Order period, between 1970 and 1989, there were significant state infrastructure projects in south Seram, mainly associated with the development of transmigration zones in the Ruatan valley. As these areas were on land claimed as Nuaulu territory, it provided a potential basis for conflict and raised issues of compensation and payment. Work on the transmigration zone infrastructure was accompanied by improvement of the road network, and in particular completion of the southern coastal road between Amahai and Tehoru, and the trans-Seram highway connecting Masohi with north Seram. The roads in turn brought buses and trucks, enabling Nuaulu to more effectively reach their lands in the Nua and Ruatan valleys and, later, electricity cables. By 1986 growing logging activity had put pressure on Nuaulu to grant concessions and sell land. As well as migrants moving into official resettlement zones, ‘spontaneous migrants’ began to settle on the fringes of Nuaulu villages on the south coast, including Rouhua, where some opened small shops and warung. Some intermarriage with Butonese further blurred identities and made people more inclined to think of themselves as Indonesian. In this new environment Nuaulu increasingly acted individualistically in terms of ownership and entrepreneurship, viewing their resources in new ways and thereby providing opportunities for greater economic differentiation between households. These new entrepreneurial outward-looking attitudes and their consequences have been particularly prominent in Nuanea, where the restoration of ancient territory to Nuaulu and the assertion of local autonomy is entirely in keeping with the spirit of a ‘traditionalist path to modernity’.

As the von Benda-Beckmanns have noted (Citation1998, 148), the Indonesian state has a penchant for governing by way of ‘projects’. Although formally under the administrative authority of Sepa, other government departments were directly involved in Nuaulu affairs, no more so than the Ministry of Social Affairs, which designated groups (usually animist, remote, unschooled) as suku terasing (separated/marginal tribes) and later masyarakat terasing (separated/marginal societies) or even masyarakat yang di belakang (backward societies). This status was supposed to release special development funds for Nuaulu to raise them to the level of other local peoples and might, for example, involve assistance in upgrading housing. This was already happening as I began fieldwork on Seram (1970, Proyek Bunara), and was repeated at least twice during the 1970s in Rouhua (1975–77). The first attempt involved plank-built houses, but Nuaulu complained about their unsuitability, poor materials, and construction. Many were left unoccupied. The second attempt involved half-cement houses with corrugated iron roofs, and these proved more robust and acceptable. In both cases the original plan failed to be effectively realised due to the siphoning-off of funds by corrupt officials along the chain supervising the work and procuring materials. By 1990 some Nuaulu were building their own cement houses. Other state projects focused on Rouhua included repeated attempts to establish kebun sosial to grow cash crops collectively, and an agroforestry project, Proyek Desa Hutan (1996), to plant cacao and teak seedlings and thereafter sell new seedlings freely on the market. Other projects were supervised by NGOs, for example the installation of concrete water cisterns (1981), the replacing of bamboo water conduits with metal piping (Catholic Church), and a failed plan by the Summer Institute of Linguistics to install WCs. Incorporation through projects such as these, especially those motivated by the status masyarakat terasing, only served to compartmentalise Nuaulu, marking out and reinforcing their separateness, and delaying the likelihood of full integration into a national state.

Adolescence and Age Differentiation: 1946–65

The Nuaulu developmental cycle and pattern of socialisation that I documented in the 1970s had no place for the category ‘youth’ or adolescent. Onset of adulthood was marked starkly for girls with the arrival of their first menstruation, followed by a period of confinement and then a ritual reintegration into society. Females were thereafter (N) pinamo until they got married, and so the category pinamo is strongly marked in Nuaulu behaviour and discourse. Pre-pubertal girls increasingly participated in adult female domestic and economic activities as they grew older, but their lives remained mainly focused on the village. The traditional pattern for men was different. The formal transition to adulthood was and continues to be strongly marked by participation in (N) matahenne puberty ceremonies, but the physical and social transition was more gradual. Given that in many cases adolescent boys must wait a long time for a clan matahenne to take place, there is pressure to undertake adult male tasks before they are initiated. Moreover, some become sexually precocious and may even marry before undergoing the puberty ceremony, a practice that is still technically taboo.

Men also travel more widely than women before and after going through the matahenne. This behaviour conforms to a wider pattern described in the ethnographic literature for island Southeast Asia—merantau—in this sense to wander or make one's way in life away from home, the rantau being the reach of a river (as in Borneo) or a stretch of coast (as on Seram). Iban bejalai, for example, has been described as a kind of journey preparatory to male initiation, a way of learning about the world (Kedit Citation1991). For Johan Lindquist (Citation2009), merantau has become homogenised as a national cultural form in Indonesia. During the 1970s I spent many hours listening to stories told by Napuae and other unmarried men about their travels around Seram and further afield, and about the people (including sexually adventurous women) whom they met; and of older men who when young and unmarried had worked in the service of the Dutch, Australian, or Japanese forces away from Seram. I remember also Soile and others returning from long periods away; before their departure they had removed their distinctive red head cloths, cut their long flowing or frizzy hair, and dressed in long trousers and shirts to render themselves invisible as Nuaulu in the wider world. This expectation that young men should travel had the effect of exposing youths to other ethnic groups and familiarising them with the way in which the state (whether colonial or post-colonial) provided some kind of coherent framework wherever they went.

Schooling and the Emerging Category Pemuda Under the Late New Order

Until the 1970s Nuaulu had been reluctant to send their children to school, and when I arrived in January 1970 there were only a handful of individuals (all young men) with rudimentary literacy. By 1981 more than twelve Rouhua children were attending primary school, and probably more from other villages closer to Sepa. The desire to compete effectively in the market and understand and respond to government written communications, as well as encouragement from the government itself, led during the 1970s and 1980s to increasing levels of attendance, initially at the primary school in Sepa. With this came improved spoken Indonesian, basic literacy, and more informed levels of systematic knowledge about Indonesia as a state and nation. In 1986 a school was established at the newly formed Christian settlement of Perusahaan just east of Rouhua, so-named because it had previously been the location of a Filipino logging camp. At this time there was just one peripatetic teacher. Another school was for a while established at Lata, between Rouhua and Tamilouw, guarded by the semi-literate Sekanima living at Mon. The Perusahaan school and the neighbouring church and group of houses were destroyed at the end of 1999 at the time of the communal disturbances, and the small Rouhua Christian community fled to Waraka on Elpaputih Bay, where they established Rouhua Baru. Animist Rouhua children resumed their attendance at the state primary school in Sepa, which was also attended by children from other Nuaulu villages around Sepa. By 2015 a new school had been established at Rouhua within the village area, which catered for all residents including animist Nuaulu and a growing number of Butonese, for whom there had also been a mosque since 1986. By this time any lingering resistance to having a school within the village, where its proximity might contaminate clan sacred houses, had effectively ceased. I would estimate that all Nuaulu born after 1980 have achieved some degree of literacy, following acceptance that reading, writing, and good spoken Indonesian were vital qualifications for advancement and official positions. Most children, however, have usually left school by the end of primary level; some have gone on to secondary school (both lower SMP and higher SMA), which usually involves moving away from the village; and by 2015 a handful from different villages had qualifications from tertiary level institutions in Ambon, while there were also Nuaulu teaching assistants employed in primary schools.

For children, school is the main institution inculcating the values of the state: through deference to the authority of the teacher, instruction in the national philosophy of Pancasila, uniform, the ceremony of raising the national flag (kasinaik bendera), the singing of the national anthem and other patriotic songs, and participation in scouts (pramuka)—all delivered through a ‘culture of regimentation’ (Ellen Citation1988). Similarly, the concept of pemuda for Nuaulu has been mainly acquired through schooling. Before Nuaulu started going to school it had little or no meaning. Schools divide children into a series of age and ability grades that cut across traditional Nuaulu distinctions. Until recently Nuaulu had little precise knowledge of birth dates. Once these start being recorded there is an objective basis for distinguishing age grades. Moreover, by the 1980s teachers were having a major impact on how young Nuaulu viewed the state and what it meant to be Indonesian. As the von Benda Beckmanns have shown (Citation1998, 143) for Ambon, between 1970 and 1980 Indonesia's bureaucracy quadrupled. From a period when the state intruded into villages lightly and only from time to time, at the subdistrict level and below in the villages there were now far more civil servants and the state seemingly moved closer and more permanently to the rural population.

The Indonesian government deliberately elaborated the category of pemuda and fostered the cult of youth as part of the apparatus of state control, much as authoritarian and communist states of eastern Europe had done. The scout movement (pramuka) had been introduced by the Dutch, but under Sukarno was appropriated by the new state as a force for national integration. Youth generally was bureaucratised through the Kementerian Pemuda dan Olaraga (Ministry of Youth and Sport) and para-militarised (Kloos Citation2018). By 2013 membership of scout groups had become compulsory for students.

Thus, for Nuaulu, the category ‘youth’ emerged with the introduction of regular schooling, effectively during the 1980s. The skills of literacy and numeracy, an acquaintance with the values of Pancasila, and general knowledge of the organisation of the state increasingly set younger Nuaulu apart from their elders. This was manifested in the way schooled Nuaulu were being consulted by elders concerning affairs of state, and representations made by the same to elders in matters of state interference that affected their participation in civil affairs. By 1990 the title kepala pemuda was being used in Nuaulu villages as an official title for a ‘responsible’ older youth who could represent and organise younger people in the village. Usually there was one for males and another for females. Demonstrated ability in youth organisation became a route for acquiring higher administrative office. We have already noted how Sonohue in Rouhua, on the basis of his education and leadership skills, would become sekretaris and eventually government head of the village, but in 1990 he was kepala pemuda. By this time schooling, official youth organisation, and youth culture combined was beginning to impact on Nuaulu as cultural citizens of Indonesia. Further, most educated youth had either remained or returned to their villages after schooling and a short period of absence. At the present time, while education is considered increasingly significant, it has not led to permanent out-migration by youth—articulate and knowledgeable community members—as it has in many other parts of Indonesia. Thus a larger cohort of Nuaulu pemuda have been in a position to play a role as cultural and political brokers.

The Kelompok Business of 1990

Throughout my time among the Nuaulu, individual villages have periodically been asked by local government to undertake community work (loosely speaking gotong-royong), and I have already noted the importance of this in underpinning Nuaulu relations with the state from 1970 onwards. Initially this might involve collecting forest resources for some government project, such as rattan for police accommodation (the Asrama Polisi) in Amahai. Later there would be directives to establish collective gardens or plantations, following yet another initiative from a government ministry (variously kebun pemerintah, kebun sosial or kebun PELITAFootnote2), or there would be an initiative to improve housing. These demands—placed on the Nuaulu community of villages as a whole—introduced new alternative models for organising labour and in particular new ways of thinking about the recruitment and composition of work groups.

To begin with these were requests channelled through the village head, and adults (always males) would be expected to comply, several members from each clan or house making up a work party of sufficient size. Groups were formed to undertake other work that was not strictly traditional, and conducted under other rules, such as constructing a government guesthouse. Groups brought together to work on sacred houses or to make preparations for major rituals and feasts are known as (N) makananae, and organised on a clan or house basis, though often recruiting in-laws from other clans. By 1990, work groups formed as a result of government requests were being described in Nuaulu conversational speech as kelompok, using the Indonesian term to distinguish them from (N) makananae groups. I had heard the term being used before; for example, in connection with the kebun PELITA, but the usage was novel at that time. The term kelompok can refer to any kind of group of objects or people in Malay, but in Indonesian was increasingly favoured in official circles towards the end of the New Order and beyond in the technical quasi-official sense of kelompok kerja, used specifically to label work groups formed under government guidance. Thus, in Kei Kecil in 2009 (Soselisa and Ellen Citation2013), kelompok was used to describe groups working specific plots within government projects, often semi-permanent and with names.

The new Nuaulu kelompok concept appeared to be a bit different. By the end of February 1990, the kelompok business in Rouhua was becoming big. Arranged through Kepala Pemuda Sonohue, kelompok were being formed to mend the roof of the house of the sekretaris, and that of the wakil and of the kepala pemuda himself, and also for making thatch for other purposes and for transporting copra. These kelompok were loosely organised along kinship and affinal lines, and hosted focally by the clan Matoke because the village wakil was from Matoke. As the workload expanded so male youths disproportionately recruited to kelompok began to complain. Whereas work parties organised for labour on sacred houses were automatically and customarily accompanied by (N) nasae (traditional feasts) for those involved, and came with the sacred force of (N) monne (obligatory ritual duty), none of this was mandatory for kelompok work. It had been the custom to follow where possible the traditional model, and the work on the roof of the wakil's house was rewarded with a nasae given by the head of the clan Matoke. However, at the old kebun pemerintah site on the Mon river there was confusion over whether they should be offering the usual nasae or offering a reward of some other kind. A deputation of young men was organised to approach the wakil and ask if they could organise a kind of dance festival, pesta joget, as a means of payment. After some discussion with the (N) ia onate ankarua and a meeting of elders, the wakil conceded that it was the right thing to do.

In Indonesia the term joget is usually applied to any form of popular street dance, such as that performed to dangdut music, often involving teasing and playing between partners. During my times in Indonesia, it was also regarded as daringly risqué in rural areas and often disapproved of by older people, especially conservative Muslims. One of the most popular types of joget is called joget lambak and usually performed by a large crowd together in social functions, and this is what was envisaged by the Rouhua pemuda. As far as I am aware, this was the first occasion when a joget event had been organised in a Nuaulu village. Quite apart from the logistical problems, hitherto there had been much disapproval expressed by elders, in large part relating to the potential immodesty of any females taking part. Some young Nuaulu had previously participated in joget in other (usually Christian villages) such as Nuelitetu, Hatuhenu, and larger centres such as Amahai and Masohi. The Nuaulu cultural form that most resembled what was planned here is tug-of-rattan performances accompanied by sung verse (N kapata ararirane), much of which involves allusive and satirical gossip about sexual relationships, and in which men and women sing alternate verses.

How to procure the resources and cover the costs of the pesta joget was a problem to be resolved. I was asked to pay for petrol for a generator. There was also a music system involving a cassette player and amplifiers. It was reckoned that the cash outlay on food for each person would be between 500 and 1000 rupiah. Indeed, cost and relative ease of organisation was likely a consideration in agreeing to the pesta joget in the first place. Not only were the food costs cheap compared with the 5000 rupiah per person estimated at that time for a traditional (N) nasae held in a sacred house, but nasae procurement, organisation, and distribution arrangements were anyway notoriously complex. The solution was very much in line with the simplification of traditional ritual found in other areas of contemporary Nuaulu life (Ellen Citation2012, 286–288). The use of the term pesta is also significant, differentiating a purely secular government event from other festivities associated with traditional rituals.

On the day of the pesta joget a temporary (N) tainane (pondok or sabua) made from bamboo and sago thatch was erected next to the wakil's house adorned with decorative coconut fronds and branches of Codiaeum variegatum, similar to structures erected for festivities elsewhere in the Moluccas. As it became dark, the generator started up, electric lights came on, and loud dangdut music began to thump out from the amplifiers. The kepala pemuda, wakil and other hosts of the pesta kelompok began to assemble, but sat apart on cane chairs and benches. They would observe the proceedings but not participate in the joget or consume food, as would also have been the custom at a regular feast. The young male bloods began to line up on one side dressed in flashy shirts, long trousers and—unusual at that time—socks and trainers. Most of the girls were modestly dressed, but a few quite daringly ‘immodest’ by current Nuaulu standards. Sartorially these Nuaulu youths adopted postures and ways of speaking that made them look little different from any other bunch of young rural Indonesians anxious to be seen as fashionable. Villagers not connected with the kelompok watched the proceedings from outside the (N) tainane. Those more likely to know than me thought the event a great success.

A few weeks after the pesta joget another event underlined for me the growing political role of Nuaulu youth. By 1990 there were increasing concerns over outside pressures on resources which Nuaulu themselves linked to state discrimination against their belief system and barriers in the labour market and at school (Ellen Citation1999). With the appearance of an articulate younger group of schooled Nuaulu this was becoming an increasing issue. I was approached by Komisi, then village headman, to help the pemuda by producing a video in which Rouhua addressed the Indonesian state. In the first part, Komisi (in Nuaulu) chastised the government from behind a makeshift podium, but the second part was a short play by adolescents in school uniform adopting conventions of dramatic performance presumably acquired at school and through the media, followed by a speech by Sonohue the kepala pemuda, all conducted in Indonesian.

Discussion: The Art of Being Sufficiently Indonesian

The performance of the first pesta joget in Rouhua was arguably a watershed in the development of Nuaulu youth culture, as well as marking a new arrangement for organising and rewarding work for state-initiated and other collective secular ends. The life of the first 1990 kelompok ended with the joget, and a second kelompok was formed shortly after for work on the kebun desa. This organisational model was to continue, and it was still operating in 1996 for the Proyek Desa Hutan. The formation of work groups based on the labour of pemuda in exchange for a periodic pesta joget or some other reward provided a new and alternative way of organising work and helped to solidify the idea of pemuda as an entity. And because the whole idea of pemuda was elaborated through state institutions it also helped to consolidate the presence of the state in the village. But little of this would have been possible without the Nuaulu population also reaching a critical demographic threshold. This ensured that the issues of cultural difference between Nuaulu and those who live with them and around them became ever more politically visible.

By the latter I mean that youth can only really become a meaningful category if there are sufficient people, between say the ages of 10 and 25, to differentiate a clearly demarcated group. In 1970 Nuaulu population levels could barely yield such a grouping, but as numbers grew during the 1980s and 1990s, and the cohorts born between 1960 and 1970 matured, so potential recruitment to a youth grouping attained viability (Ellen Citation2018, 177). But of all demographic cohorts, that for the ages 11–25 is also the most divided in terms of competing allegiances. The group is almost equally split between males and females, while there is a strong cultural distinction between females who have gone through menarche and those who have not and who are still technically juveniles. Moreover, post-menarche females are expected to marry as soon as possible and once married are more difficult to place within a youth group. There is more fluidity for males. Males who have been waiting a long time to go through the (N) matahenne can be physically very mature when they finally do so, though in recent years there has been a tendency for males to be initiated younger. Moreover, the upper boundary for those considered legitimate pemuda is fairly flexible. Strikingly, in 1990 Sonohue as kepala pemuda was already 30–35 years old and his wife Maulea had given birth to seven children.

Thus, while the formal education system places Nuaulu young people into Indonesian state categories—into ability and age-ranked classes, and requires them to identify as pemuda—it also interferes with traditional lifecycle rituals and expectations regarding marriage. For females, confinement on reaching first menstruation is shortened so that they can quickly resume their schooling. For many this is seen as a convenient innovation as, like staging large traditional feasts, keeping girls confined to the puberty (N) posune is expensive. Similarly, marriage may have to be delayed in order to complete education. For males, the younger they are when going through their (N) matahenne the easier it is in terms of both schooling and in respecting the lower age boundary of pemuda. Men too defer marriage in order to complete their education.

The events of 1990 were a foretaste of things to come. Nuaulu youth were to emerge not simply as a structural grouping of better informed and skilled individuals increasingly competent and prepared to challenge their elders but also as a group which identified with a wider trans-ethnic ‘youth culture’ cutting across local language, and cultural and religious boundaries. This identification was achieved partly through various kinds of electronic media: first radio and then during the early 1980s television, then cassettes and videos, followed by DVDs, and by the mid-2000s mobile cell phone technology supporting social media platforms such as Facebook. These technologies connected Nuaulu to a wider Indonesia not through state institutions as such but through the market of shared cultural media, also more immediately drawing upon regional youth culture with its hybrid cultural conventions and role in post-conflict resolution (e.g. Bräuchler Citation2019). Nuaulu schoolchildren, for example, have absorbed elements of both Muslim and Ambonese Christian popular music. More recently, an organised football league with significant government subsidies has also served as a recreational force for cultural integration.Footnote3

For Nuaulu, pemuda are not merely unmarried adolescents but both unmarried and married young people with education, who are more secular in their outlook and more preoccupied with political and other responsibilities. In these respects, they contrast with the still largely uneducated elders who nevertheless control access to sacred matters and occupy ritual positions. But an increasingly outward-looking cultural identification among the young has gone hand-in-hand with a re-assertion of traditional religious and cultural identities. While Nuaulu youth can confidently assert their identity as Indonesians, and warm to the notion of ‘unity in diversity’, there remain conflicting loyalties and a problematic relationship with the state which is related to access to territory and Pancasila.

The younger generation of Nuaulu can, therefore, be said to be more ‘trans-ethnic’. This is partly achieved through adherence to an abstract notion of what it means to be Indonesian; partly through their exposure to education, modern media, and travel; partly through the impacts of trans-migration and spontaneous migration on their daily lives; but more selectively through identification with other adat-minded peoples of the geographic and political periphery. Paradoxically, for Nuaulu at least, AMAN (the Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara) presents itself in the context of the New Indonesia as forward-looking rather than narrowly backward-looking. This is in contrast to the portrayal of adat in colonial scholarship and in the political and legal modernism of the first thirty years of the independent Indonesian state, which treated it as an essentially conservative force that needed to be contained and which was anyway likely to be in historic decline. In a contemporary context, adat is one of the forces liberated by post-Soeharto reformism and in the Moluccas revitalised by the tragedy of inter-communal and religious conflict. But relatively few Nuaulu have converted to Islam or Christianity over the last fifty years, and so it is less that they are ‘reviving’ or ‘inventing’ tradition than they are continuing doing what they have always done (with modifications, say in relation to the role of head-taking) but on a larger scale, more openly, and in a politically more receptive environment. They are not trying to re-create something that they have lost, except in the sense of regaining territory and autonomy.

What Nuaulu seek to protect and project is not some reified de-historicised set of practices but everything they do—and certainly not the much-discussed New Order ideological conceit of adat as a category of limited cultural practice for show, a kind of ‘sanitized ethnicity’ (Duncan Citation2009). It is not that adat assertion somehow shifts primordial loyalties from religion to ethnicity (as in some other Moluccan groups since 2003), but that it provides an instrument by which they can promote a separate ‘religious identity’. This is a key difference between Nuaulu and other communities where tradition is being more explicitly revived. Religious conflict between Muslim and Christian communities only reinforced for Nuaulu their position as neither. In a Moluccan context this was an opportunity to assert their religious and political independence. In many parts of eastern Indonesia, the resurgence of adat is not an alternative to Christian or Muslim identities but, rather, complementary, and in the provinces of Maluku and North Maluku a way of seeking reconciliation. The conjunction between traditionalism and modernism is certainly paradoxical, and this is why the Nuaulu case is especially interesting.

Conclusion

I have demonstrated that being Indonesian is experienced differently by Nuaulu depending on age and generation. I have paid attention to how the emergence of youth culture and formal education between 1980 and 2015 has served to integrate younger Nuaulu as cultural Indonesians while also undeniably threatening to destabilise traditional authority along the way. A paradoxical beneficial outcome of this process, and of the conflicts with migrants, and wider religious conflict between Christians and Muslims, has been the achievement (albeit incomplete) of a measure of territorial autonomy and state recognition for Nuaulu beliefs and practices. I have emphasised the central role of language in this process, and how since 1970 state power has intruded as administrative infrastructure has grown, how the market has driven economic and cultural integration, and how all have contributed to the context in which the youth category (pemuda) has emerged as one with political consequences for reinvigorating Nuaulu identity vis-a-vis the state. In particular, I have exemplified the notion of pemuda in relation to developments connected to the organisation of secular work groups in 1990. Conflict with the state and its agencies over land and resources continues, as have practical difficulties related to non-recognition of Nuaulu religion. The negative experiences of communal Christian–Muslim conflict between 1999 and 2003, and the opportunities afforded by reformasi and otonomi daerah, have emboldened younger Nuaulu to balance being good Indonesian citizens, with its civic and economic modernism, with the maintenance and public assertion of much traditional ritual, belief, and identity markers.

If the New Order tried to control ethnic minorities by classifying and administering them as masyarakat terasing, taming cultural difference and depoliticising them and making them Indonesian, then reformasi, otonomi daerah, and the forces of techno-cultural globalisation have emphasised what Indonesians have in common through social experience and values. But those same media have also provided a means of reasserting difference and ‘multiple citizenry’ (von Benda-Beckmann and von Benda-Beckmann Citation2010). Participation in a national organisation such as AMAN, identification with a pan-Indonesian revival of adat and an international notion of ‘indigenism’, is a paradoxical recognition that the minorities involved are indeed Indonesian in the sense of participating in a shared nation-wide discussion, and initiating action that is defined by the boundaries of the Indonesian state and conducted through its institutions (see e.g. Davidson and Henley Citation2007). It could be argued that becoming culturally Indonesian has been achieved for Nuaulu as much through the unplanned consequences of the market and electronic media as through deliberate ideological indoctrination through schools and other state institutions. Although the category pemuda emerges through the schooling system and is encouraged through other state interventions, in recent years it has spread through self-identification with youth in other parts of Indonesia, who share a common interest in certain kinds of cultural activity—mainly sport, dress fashion, dance, and music—mediated by shared ways of using the Indonesian language. It also implicates a certain progressive political stance (Lee Citation2016). The undeniable conflicts and tensions with outsiders, and between different outsiders, that young Nuaulu have witnessed over the last few decades have left them with many unresolved issues of identity and socio-economic deprivation, but being Indonesian is probably not among them.

Acknowledgments

Nuaulu fieldwork between 1970 through to 2015 has been supported by various funding bodies and grants, listed in full elsewhere (Ellen 1918, xiiii–iv). The research in 1990 specifically referred to here was generously financed through a Southeast Asia travel grant from the University of Kent, and the writing of this chapter has benefitted from receipt of a Leverhulme Trust Emeritus Fellowship (EM-2018-057\6, 2018-21).

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Non-English terms are in Bahasa Indonesia unless identified as Nuaulu by the sign (N).

2 A garden or grove established as part of the five-year plan (Pembangunan Lima Tahun) but also an acronym conveniently meaning ‘light’.

3 Other state institutions, such as prisons, have provided unlikely contexts for forging trans-ethnic Indonesian identities. Nuaulu prisoners incarcerated in Masohi jail following resource conflict in the Ruatan valley were released several years later displaying lavish tattoos that owed more to Christian iconography than to traditional Seramese styles.

References

- Benda-Beckmann, Franz von, and Keebet von Benda-Beckmann. 1998. “Where Structures Merge: State and Off-State Involvement in Rural Social Security on Ambon, Indonesia.” In Old World Places, New World Problems: Exploring Resource Management Issues in Eastern Indonesia, edited by Sandra Pannell, and Franz von Benda-Beckmann, 143–180. Canberra: ANU.

- Benda-Beckmann, Franz von, and Keebet von Benda-Beckmann. 2010. “Unity and Diversity: Multiple Citizenship in Indonesia.” In Cultural Diversity and the Law: State Responses from Around the World, edited by M.-C. Foblets, J.-F. Gaudreault-DesBiens, and A. D. Renteln, 889–917. Bruxelles: Bruylant.

- Bowen, John R. 1986. “On the Political Construction of Tradition: Gotong Royong in Indonesia.” The Journal of Asian Studies 45 (3): 545–561. doi:10.2307/2056530.

- Bräuchler, Birgit. 2019. “From Transitional to Performative Justice: Peace Activism in the Aftermath of Communal Violence.” Global Change, Peace and Security 31 (2): 201–220. doi:10.1080/14781158.2019.1585794.

- Collins, James T. 1980. Ambonese Malay and Creolization Theory. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka.

- Davidson, J. S., and David Henley. 2007. The Revival of Tradition in Indonesian Politics: The Deployment of Adat from Colonialism to Indigenism. London: Routledge-Curzon.

- Duncan, Christopher R. 2009. “Reconciliation and Revitalization: The Resurgence of Tradition in Postconflict Tobelo, North Maluku, Eastern Indonesia.” Journal of Asian Studies 68 (4): 1077–1104. doi:10.1017/S002191180999074X.

- Ellen, Roy. 1988. “Ritual, Identity and the Management of Inter-Ethnic Relations on Seram.” In Time Past, Time Present, Time Future: Perspectives on Indonesian Culture: Essays in Honour of Professor P.E. de Josselin de Jong, edited by Henri J.M. Claessen, and David S. Moyer, 117–135. Dordrecht/Holland: Foris.

- Ellen, Roy. 1993. “Rhetoric, Practice and Incentive in the Face of the Changing Times: A Case Study of Nuaulu Attitudes to Conservation and Deforestation.” In Environmentalism: The View from Anthropology, edited by K. Milton, 126–143. London: Routledge.

- Ellen, Roy. 1997. “On the Contemporary Uses of Colonial History and the Legitimation of Political Status in Archipelagic Southeast Seram.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 28 (1): 78–102. doi:10.1017/S0022463400015186.

- Ellen, Roy. 1999. “Forest Knowledge, Forest Transformation: Political Contingency, Historical Ecology and the Renegotiation of Nature in Central Seram.” In Transforming the Indonesian Uplands: Marginality, Power and Production, edited by T. Li, 131–157. Amsterdam: Harwood.

- Ellen, Roy. 2002. “Nuaulu Head-Taking: Negotiating the Twin Dangers of Presentist and Essentialist Reconstructions.” Social Anthropology 10 (3): 281–301. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8676.2002.tb00060.x.

- Ellen, Roy. 2004. “Escalating Socio-Environmental Stress and the Preconditions for Political Instability in South Seram: The Very Special Case of the Nuaulu.” Cakalele 11: 41–64.

- Ellen, Roy. 2012. Nuaulu Religious Practices: The Frequency and Reproduction of Rituals in a Moluccan Society. Leiden: KITLV Press.

- Ellen, Roy. 2014. “Pragmatism, Identity and the State: How the Nuaulu of Seram Have Re-Invented Their Beliefs and Practices as ‘Religion’.” Wacana 15 (2): 254–285. doi:10.17510/wacana.v15i2.403.

- Ellen, Roy. 2018. Kinship, Population and Social Reproduction in the ‘New Indonesia’: A Study of Nuaulu Cultural Resilience. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Florey, Margaret. 2005. “Language Shift and Endangerment.” In The Austronesian Languages of Asia and Madagascar, edited by A. Adelaar, and N. P. Himmelmann, 43–64. London: Routledge.

- Haar, B. ter. 1948. Adat Law in Indonesia. New York: Institute of Pacific Relations.

- Kedit, Peter M. 1991. “Meanwhile, Back Home … Bejalai and its Effects on Iban Men and Women.” In Female and Male in Borneo: Contributions and Challenges to Gender Studies, edited by V. H. Sutlive, 295–316. Williamsburg, VA: The Borneo Research Council.

- Kloos, David. 2018. Becoming Better Muslims: Religious Authority and Ethical Improvement in Aceh, Indonesia. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Koentjaraningrat. 1967. “The Village in Indonesia Today.” In Villages in Indonesia, edited by Koentjaraningrat, 386–405. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Lee, Doreen. 2016. Activist Archives: Youth Culture and the Political Past in Indonesia. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Lindquist, Johan A. 2009. The Anxieties of Mobility. Migration and Tourism in the Indonesian Borderlands. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

- Mietzner, Marcus. 2019. “Indonesia’s Elections in the Periphery: A View from Maluku.” New Mandela, April 2. Accessed June 11, 2020. https://www.newmandala.org/indonesias-elections-in-the-periphery-a-view-from-maluku/.

- Paauw, Scott. 2009. “One Land, One Nation, One Language: An Analysis of Indonesia’s National Language Policy.” University of Rochester Working Papers in the Language Sciences 5: 2–16.

- Soselisa, Hermien L., and Roy Ellen. 2013. “The Management of Cassava Toxicity and its Changing Sociocultural Context in the Kei Islands, Eastern Indonesia.” Ecology of Food and Nutrition 52 (5): 427–450. doi:10.1080/03670244.2012.751913.

- Zentz, Lauren. 2017. Statehood, Scale and Hierarchy: History, Language and Identity in Indonesia. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.