ABSTRACT

From the late 19th century, when the Melbourne manufacturer and department store Foy & Gibson began to produce mail order catalogues for country customers, it recognised the potential to sell clothing made of Australian wool. This article explores how Foy & Gibson influenced consumer attitudes towards the natural fibre by encouraging them to feel wool as a next-to-the-skin experience. By focusing on underwear and swimsuits in the catalogues across the first three decades of the 20th century, it offers a historical counterpoint to promotional activities that continue into the present urging consumers to understand the benefits of wearing wool.

When Australian Wool Innovation launched its Feel Merino campaign in 2020, the organisation challenged a “persistent and outdated misconception”: the feel of wool as itchy and suited only to very traditional uses. Framing wool as an innovative performance fibre in its aim to capture a share of the booming sports and athleisure markets, the campaign cast a spotlight on the natural fibre as “soft on your skin no matter the challenge”.Footnote1 Feel Merino was the latest in a move that had intensified across the 20th century as mills, manufacturers, retailers and industry bodies sought to spark an awareness of wool’s diverse uses and superior feel, particularly against the emerging threat posed by synthetic rivals.Footnote2 It is this “feel” of Australian wool and its uses that animates my discussion of the next-to-the-skin experience, a century before the Feel Merino campaign. I offer this historical counterpoint through a study of the woollen clothing produced by the Melbourne manufacturer and department store Foy & Gibson, to explore how consumer attitudes to wool were shaped in the decades before the enthusiastic embrace of artificial fibres.

Foy & Gibson’s mills—referred to as its “two miles of mills” a hundred years ago—dominated the inner-Melbourne suburb of Collingwood.Footnote3 Its slogan, “From the sheep’s back to yours”, pointed to Foy & Gibson’s use of Australian wool worked in these mills, then made into cloth and clothing to be sold from its flagship Smith Street store and, later, other stores in Melbourne and across Australia including Perth, Brisbane and Adelaide.Footnote4 Many shopped in-store, but rural customers turned to Foy & Gibson’s mail order catalogues from the 1890s and for decades to follow to make their selections.Footnote5 The astonishing array of goods illustrated in the catalogues’ pages now provide a rich case study into the changing look, style and sartorial sensibilities of Australians, as clothing underwent a radical transformation towards more relaxed dress. They reflect strategies to entice consumers to Foy & Gibson’s affordable but good-quality products.Footnote6 They capture the ways in which Foy & Gibson sought to educate customers on the benefits of wearing wool. The catalogues also reveal how Foy & Gibson encouraged a “Buy Australian” ethos and the promotion of homegrown wool in the period before and during the formation of the country’s peak wool body in 1936, the Australian Wool Board—the forerunner to Australian Wool Innovation.

The historical parallels for consumers now and then to “feel merino” shapes the direction I take as I consider the artwork and language Foy & Gibson used to sell wool—Australia’s “finest and purest”, in the 1925 winter catalogue’s words.Footnote7 My exploration ranges across three decades, beginning at the turn of the 20th century and ending with the outbreak of the Second World War. Austerity measures and rationing would soon come into play, changing how consumers thought about and obtained clothes.Footnote8 I trace trends in the mail order catalogues’ pages across these years, alert to gendered patterns. I do not attempt, however, to analyse the effectiveness of the promotional messages because that has been done before.Footnote9 My focus on garments worn directly against the skin—swimsuits and underwear for both men and women (though Foy & Gibson made many other clothes in wool)—helps me to tease apart the urging for consumers to feel wool as part of a sensorial experience materialised on the body.

This study is informed by the rich scholarship on advertising’s connection with gender, modernity, consumer culture and the cycle of fashion.Footnote10 Even more, it considers the intersection between dress and its feel on the body. Two decades ago, Joanne Entwistle encouraged scholars to consider “dress as embodied practice”.Footnote11 As work on embodiment, materiality and our material worlds flourished, the focus on interactions between dress and the body as part of tactile, sensorial and affective experience grew. Such scholarship demonstrates how clothing is not simply worn but is felt, shaping our experience of the world.Footnote12 As Rosie Findlay explains, for example, her awareness of her body is heightened when wearing leather pants, making her more conscious of how she moves: “Thus the materiality of the pants changes my experience of my legs,” she observes, just as her “sense of being in the world and being myself within that world is in some way mediated by my clothes”.Footnote13 Heike Jenss and Viola Hofmann would call this clothing’s “intimate material role in the enactment and experience of the body and culture”, whereby “feeling the imprint of fabrics and garments on the body” holds the potential to provoke “feelings of desire and excitement … or experiences of discomfort, self-consciousness, or marginalization”.Footnote14

Central to such work is the understanding that clothes are felt through touch, but also impacted by sight, cultural preconceptions, and psychological and social factors.Footnote15 Scholars have indeed investigated the feel—in this multidimensional sense—of synthetic clothes.Footnote16 Most recently, it has been used to shed new light on clothing waste, with Elyse Stanes and Chris Gibson considering the part feel plays in the cycle leading to polyester’s discard.Footnote17 It is surprising then that historical scholarship on the feel of wool remains under-developed, particularly when scientific and consumer research now seeks to better understand attitudes to wool and its properties on the body by centring a wearer’s relationship to the fibre.Footnote18 For Marie Hebrok and Ingun Grimstad Klepp, appreciating the contours of this relationship involves looking beyond an aversion to wool as “itchy”, to recognise that its material properties are entangled with certain expectations and the cultural shaping of our senses.Footnote19 The layered relationship that existed between wool and the people who wore it therefore drives my discussion.

From Draper to Department Store

Foy & Gibson’s origins stretched decades before those in the early 20th century that form my focus. Encouraged by the explosive news of the Victorian gold discoveries of the mid-19th century, Irish-born draper Mark Foy sailed to Melbourne in 1858.Footnote20 He first worked for the draper (and later department store) Buckley & Nunn in Bourke Street. Recognising the prospects for a store of his own on the goldfields, Foy opened businesses in central Victoria’s thriving goldfields towns.Footnote21 From a store in Castlemaine he sold butter, plus potatoes grown in nearby Lancefield.Footnote22 It was with his clothing and drapery store on Sandhurst’s (now Bendigo’s) major thoroughfare, Pall Mall, with partner Robert Bentley, however, that Foy experienced goldfields success.

Bentley and Foy, as the store was named, advertised extensively in the Bendigo Advertiser—almost daily from late 1867 on the newspaper’s front page. One advertisement that ran for three months captures key elements of the business: stock that moved quickly, keeping it “fresh, nice, and new”, “reasonable” if not “really low” prices, and gentlemen’s clothing made by the business’s “own tailors in Melbourne”.Footnote23 In mid-1868, Bentley and Foy enlarged their store, selling “colonial-made suits” together with under flannels and Crimean shirts “made on Sandhurst”.Footnote24 Crimean shirts, with their low, open neck, made excellent workwear, as diggers had discovered a decade before.Footnote25 Some of Bentley and Foy’s stock came from well-known British textile manufacturing centres (foreign goods held cachet on the diggings), yet Australian-made goods held exciting potential. A new black silk produced from Queensland silkworms stocked by the store from November 1868 was evocatively described as “rich, thick, soft, like to the touch of the top of cream in a country dairy”. Bentley and Foy claimed to be “doing the largest trade between Melbourne and the Murray” by then.Footnote26 Foy would use similar strategies when he returned to Melbourne shortly after: extensive advertising to keep his goods at the front of customers’ minds, a network of contacts to source quality overseas stock, and an interest in colonial manufacture.

The partnership between Mark Foy and Robert Bentley dissolved in 1870. Bentley remained in Sandhurst with the business, while Foy opened a store in Collingwood.Footnote27 By 1873, he sold silks from Spitalfields, East London, once the centre of the silk industry. He also described shawls “manufactured in Geelong from honest real wool, without cotton or shoddy mixture”. “Ladies,” Foy implored, “would you kindly call at my establishment and inspect these shawls?”Footnote28 His growing interest in selling Victorian-manufactured goods in wool grew at the same time that Foy sought a wider customer base for his Collingwood store. In the Weekly Times, he alerted women across Victoria to his wares. Those who wished to see his fabrics could write to request samples. “Thus people residing in the country are placed in the same favourable position” as those in Melbourne, Foy assured.Footnote29

Scotsman William Gibson entered as partner in 1883, with the store renamed Foy & Gibson. Though the partnership was short-lived—with Mark Foy handing control to his son Francis, before Francis left the business to open Mark Foy’s in Sydney—the name endured across decades to follow under Gibson’s direction. The 1890s witnessed enormous growth. A store opened in Perth in 1896. A new factory built in Collingwood manufactured socks and other knitted goods. Though the business considered itself “the largest manufacturers and the largest retail distributors in Australia” at the start of the 1890s, a London Office established in 1897 sourced stock from English and European suppliers.Footnote30 The Eagley Mills began operating this decade, expanding the woollens produced to blankets and a wide range of cloths, just as Australian woolgrowers were hit by drought and low prices.Footnote31 Foy & Gibson’s mills, manufacturing a range of woollen products under the “Gibsonia” brand, continued to grow to “the biggest of their kind in the Commonwealth” in the 1920s.Footnote32

“To make the type of woollen garments that can honestly be called first-class,” a booklet produced that decade explained, “the foundation must be good, sound wool.” It went on: “Of all the world’s productions in this valuable staple, Australia can claim the first place for quality”, referring to the dominant place the nation held in the global market as producer of the world’s finest wool.Footnote33 Foy & Gibson knit Australian wool into hosiery and underwear, and sold it as yarn for home knitting. It produced 50 different cloths for men’s and women’s wear: velours, hapsacs, twills, check and fancy tweeds, heavier-weight cloths for coats and mantles, and men’s suitings in different weights for Australia’s varying climate.Footnote34 By the end of the 1920s, Foy & Gibson used 2,900,000 pounds of wool per annum to produce an astonishing 8,100,000 miles of “Gibsonia” woollen and worsted yarns.Footnote35 Three-thousand employees worked in the mills to manufacture these “all-Australian woollens, garments, and fabrics”.Footnote36 Though Foy & Gibson’s operations comprised far more than wool—as haberdashers, furriers, milliners, dressmakers, tailors, hatters, glovers, boot and shoe manufacturers, it also dealt in leather goods, household furniture and fittings, iron-mongery, ornaments and more—the natural fibre remained at the business’s core for decades.Footnote37

“Australian Throughout—From Greasy Wool to Finished Article”

Wool was critical to Australia’s economy across these decades.Footnote38 Formalising the promotion and protection of the natural fibre became increasingly urgent as substitutes developed. Some commentators remained unperturbed in the 1920s. “I have never been the least concerned as to the effect of manufacture of any substitute for wool,” one expert in 1927 explained, “and I do not believe that all the ingenuity of man will ever be able to evolve a substance which will even remotely resemble wool.”Footnote39 Others would call this attitude “apathetic indolence”, arguing for Australian Government intervention in targeted research and development as “one of its prime duties”.Footnote40 After years of discussion, a statutory body representing the nation’s woolgrowers, the Australian Wool Board, was established to spearhead wool promotion and coordinate scientific research.Footnote41

The first “man-made” fibres, cellulosic fibres made into rayon, had been introduced from the turn of the 20th century. Resembling silk, rayon flourished from the 1920s.Footnote42 Short-lived wool alternatives were also tested. Substitutes such as the Italian-developed “sniafil” and German-created “woolstra”, both incorporating wood fibres with wool, “displac[ed] wool to a considerable extent throughout the world” in the 1920s and 1930s, Australia’s textile trade journal announced.Footnote43 Experimentation with wool substitutes grew further during the Second World War.Footnote44 Japan, then one of Australia’s largest wool purchasers, attempted to overcome wartime shortages by testing a “wool” made from seaweed.Footnote45 It also trialled another “revolutionary advance”: a wool alternative made from soybean.Footnote46 The first true synthetic fibres, made from oil and coal products, were produced in the 1940s, beginning with nylon. Polyester and acrylic entered the market shortly after.Footnote47 These artificial fibres marked a turning point in what clothing was made from, with their popularity skyrocketing in the mid-century period.Footnote48

Some, however, identified a bigger threat during the decades I discuss: not synthetics or wool alternatives but the production of “shoddy”. An inferior cloth to that made from virgin wool, shoddy was adulterated with reconditioned wool, wool waste or other matter.Footnote49 The Union Knitting Mills in Coburg assured consumers of its exclusive use of virgin wool for underwear and swimsuits, doing so in response to “a great amount of material” that emerged in the 1930s sold as “All Wool”, though it was in fact “made from waste material”.Footnote50 This example indicates the slippery use of the word “wool”. A call for legislation to protect the name emerged in an effort to prevent consumer deception, though debate raged over what could be included in a definition of “pure wool” or “all wool”.Footnote51 Taken literally, this definition might extend to low-grade cloth made from reclaimed wool including rags. It was therefore no assurance of quality when “wool” had the potential to be applied to the finest worsted cloths or the cheapest shoddy.Footnote52 The introduction of textile labelling legislation by state governments was a first step.Footnote53 It took years, however, to be put into operation while the Australian Government amended customs regulations to introduce similar compulsory labelling for imported textiles.Footnote54 In the meantime, the Australian Wool Board remained deeply concerned that consumers were “bewildered by the diversity” of available textiles and their fibre content.Footnote55

Interest in promoting goods of local manufacture made from Australian wool grew from the turn of the century. The Sydney department store Gowing Bros encouraged its customers with the slogan “Australian Wool for Australian People”.Footnote56 The Australian Knitting Mills promoted its Golden Fleece Underwear as “locally made for loyal Australians”.Footnote57 Foy & Gibson dressed its windows with all-wool “Gibsonia” products to remind passers-by that “Australian made deserves your trade”.Footnote58 It extended this message in its catalogues. Its goods (which were “made by Australians from the best Australian wool”, Foy & Gibson assured) were “Australian throughout—from greasy wool to finished article”.Footnote59 The catalogues encouraged consumers not simply to wear Australian wool, however, but also to think about the bodily experience of the natural fibre in order to better understand its health benefits.

Healthy in Wool

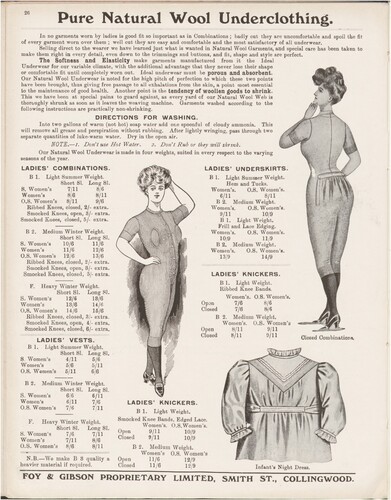

Wool-clad bodies were healthy bodies, or so Foy & Gibson’s catalogues promised. “Ideal underwear must be porous and absorbent,” the 1910 winter catalogue explained to women customers. “Our Natural Wool Underwear is noted for the high pitch of perfection to which these two points have been brought,” it continued, “thus giving free passage to all exhalations from the skin, a point most essential to the maintenance of good health.”Footnote60 These exhalations might be bodily oils or sweat, though the suggestion that either of the women illustrated on the page might perspire seemed unlikely (see ). Both wore combinations: underwear joined at the waist. One stood with her hand gently on her hip, toes pointed in heeled shoes and body gently angled. The second—drawn in the distinctive s-shaped silhouette of that decade achieved through foundation garments that started low on the bust and pushed the hips back—displayed the combinations’ back.Footnote61 That wool was a healthy next-to-the skin choice was critical in this body-hugging form, where the interface between flesh and fibre extended from neck to knee.

Figure 1. Foy & Gibson, Winter Catalogue 38 (1910): 69. Foy & Gibson Catalogues, University of Melbourne Archives.

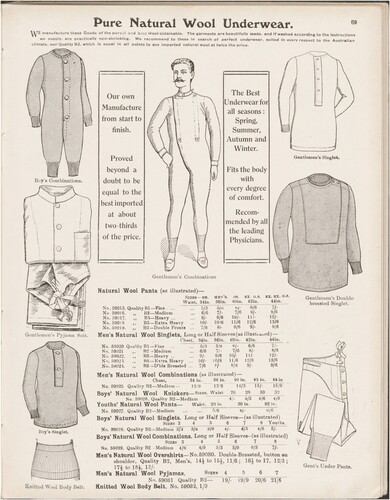

Wool encased much of the man’s body too. Illustrations of men’s “under pants” that extended to the ankle and buttoned at the fly appeared in the 1910 winter catalogue. “Singlets” also featured, though not as the sleeveless garment we now know but with sleeves to the wrist and a button placket at the neck.Footnote62 A sole figure modelled combinations (see ). His stance was strong and square, though the artwork feels surprisingly intimate. The state of undress reminds us that even though this first layer is “frequently forgotten precisely because it typically lies underneath everything else”, it is nonetheless valuable. “One has to make explicit opportunities to reflect on the daily practice of dressing, of routinely selecting and stepping into underpants, to probe the roles played out in this garment,” Prudence Black and colleagues assert.Footnote63

Figure 2. Foy & Gibson, Winter Catalogue 38 (1910): 26, 69. Foy & Gibson Catalogues, University of Melbourne Archives.

The bodies illustrated in the 1910 catalogue became even more gendered in years to come, both in the way they were posed and as props were introduced: pipes and cigarettes for men, for example, redolent of masculine ease.Footnote64 The gendering of the catalogues was further revealed in the ways they pitched their messages. The authors of sales literature believed that women consumed emotionally or were “always ready to devour bargain announcements”. Men, by contrast, made their selections rationally after asking “why” they should purchase.Footnote65 Men, but not women, were told in the 1910 catalogue that wool was “recommended by all the leading Physicians”, for example.Footnote66 Later catalogues spoke directly to male consumers. “Men!”, the 1935 autumn and winter catalogue prompted them, “You can’t afford to take risks! You must wear wool next to your skin.”Footnote67

In other respects, however, the language used to underpin the health benefits of wearing wool underclothing crossed between men’s and women’s pages. Indeed, the Draper of Australia suggested that the best catalogues should identify “everything that can be said in their favour … so that the reader has before her a word-picture of the garments as well as the illustrations”.Footnote68 The prospect of “Better Health” for both men and women became more explicitly tied to what we now recognise as wool’s thermo-regulating properties in the catalogues across years to follow.Footnote69 They counselled women that wearing all-wool undergarments kept the body “at a natural comfortable warmth; fresh air is transmitted evenly and regularly to the skin, perspiration is absorbed quickly, and there is far less likelihood of catching chill or cold”.Footnote70 Men received similar advice.Footnote71 Wool prevented winter chills, though it was also “Healthiest for Summertime” and ideal for changeable weather.Footnote72 “Sudden cool changes do not affect wearers of All Wool Underwear so readily as those wearing other types,” Foy & Gibson assured its customers.Footnote73

Foy & Gibson’s connection between good health and pure, natural fibres was not new to the 20th century. Linen underwear had been worn for health and hygiene reasons since the early modern period, linked with concerns around how often one should bathe the body.Footnote74 By the final quarter of the 19th century, wool underwear was favoured as part of the rational dress movement advocated by doctors including Gustav Jaeger.Footnote75 Jaeger promoted the health benefits of the natural fibre for the way “perspiration passes freely away through pure, porous wool”, unlike other cloths that “repress[ed] the exhalation”.Footnote76 When wool underclothing was sold as hygienic but perspiration moved through it, proper washing was important. Jaeger and other proponents offered precise advice for doing so.Footnote77 So did Foy & Gibson, with the catalogues stepping through the recommended process to “remove all Grease and Perspiration”. The purity of its wool was further underlined with the guarantee that “We Use No Chemical Processes which rob the Wool of its virtues”.Footnote78 This pure, natural wool protected the body it hugged.

In the first decades of the 20th century, ideas around health, hygiene and the Australian body had also transformed with a growing interest in physical culture. The Women’s League of Health and Beauty peaked in popularity in Australia in the 1930s. The league’s philosophy and exercise system set out to improve women’s physical health, encouraging fitness and vitality as the foundation of beauty.Footnote79 Similarly, the national fitness program saw physical activity and the culture of healthy bodies rise from the late 1930s for both men and women as part of a project of modernity.Footnote80 Publications such as Withrow’s Physical Culture magazine further encouraged movement and exercise. “Health is what makes perfect the physical in man and woman—the light step, the pink cheek, the pure skin, the clear eye, the sweet breath, the white teeth, the powerful grasp of the hand, the firm muscle and the perfect form,” Walter Withrow described for readers.Footnote81

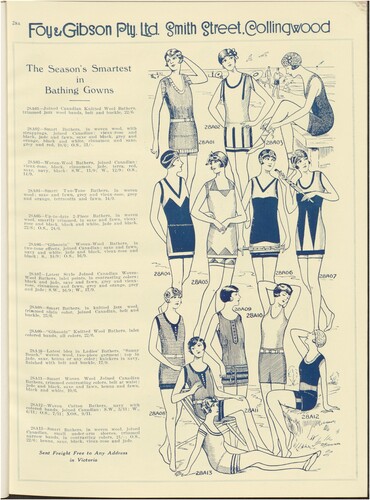

It was in this context that Foy & Gibson’s swimsuits found a market connecting wool with a different kind of healthy body from that of underwear. “Diving, Plunging, and Dipping into the foaming waters of the surf gives one a rejuvenated feeling of glorious lively youth,” a writer for the Gibsonia Gazette explained in 1926, describing Australia’s growing adoration of sea bathing and beach culture as a site of healthy leisure.Footnote82 Foy & Gibson recognised the potential for making and selling swimsuits, as did plenty of others including those sold under the Speedo, Jantzen, Golden Fleece, Black Lance labels and more.Footnote83 By the time Foy & Gibson’s swimsuits were “used by leading life-saving clubs” in 1928, the surf lifesaver had solidified as a national icon.Footnote84 The timing was critical occurring in the aftermath of First World War servicemen’s return, some suffering ongoing physical or psychological trauma.Footnote85 Australia’s lifesavers represented what Kay Saunders has described as flawless heroes during a time in which Australia reeled and recovered from war.Footnote86

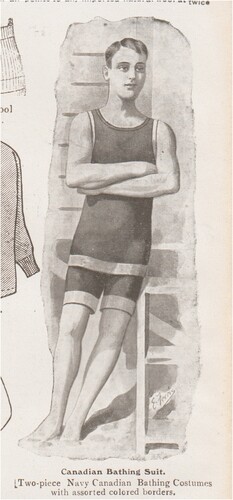

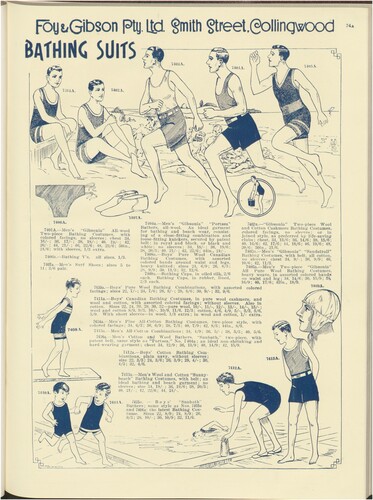

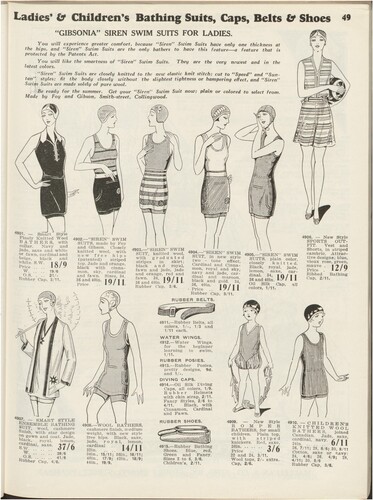

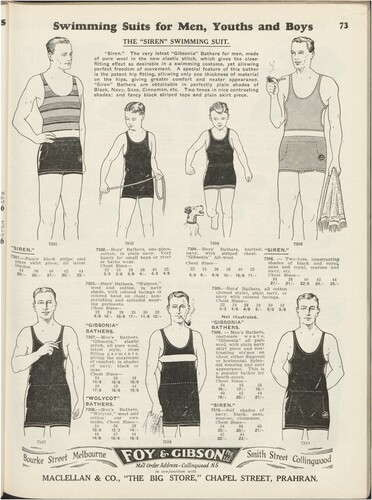

Beach bathing was “the privilege of all and the monopoly of none”, the Gibsonia Gazette declared.Footnote87 Swimsuits illustrated against the backdrop of this democratic space at the water’s edge confirmed this, as did the change in bathing wear. Pre–First World War bathing costumes for women consisting of loose, belted gowns that finished at the knee, with legs modestly covered by bloomers and knitted hosiery, and men’s suits were in the Canadian style ( and ).Footnote88 In years to follow, however, wool’s elastic properties provided not only new ways of seeing the healthy body but also new ways of being healthy. Briefer knitted woollen swimsuits entered the market in the 1920s. A range of styles introduced in quick succession hugged the body tightly, revealing its contours while exposing more of its flesh. By 1926, “Gibsonia” swimsuits included the men’s “Portsea” style, which was “secured by a patent belt”.Footnote89 The belt held swimsuits firmly in place while wearers moved through the surf. This fixture was important when wet wool was known to sag. Belts featured on men’s and women’s styles across the decades to follow, encouraging active beach use, despite the catalogues’ illustrations, which contrasted beach experiences: women’s gentle movement unlike men’s action on the sand ( and ).Footnote90

Figure 3. Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 41 (1911–12): 15 (detail). Foy & Gibson Catalogues, University of Melbourne Archives.

Figure 4. Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 43 (1912–13): 84 (detail). Foy & Gibson Catalogues, University of Melbourne Archives.

Figure 5. Foy & Gibson, Summer Catalogue 74 (1926–27): 28A. Foy & Gibson Catalogues, University of Melbourne Archives.

Figure 6. Foy & Gibson, Summer Catalogue 74 (1926–27): 74A. Foy & Gibson Catalogues, University of Melbourne Archives.

The swimsuits and underwear of these decades readily reveal why dress is referred to as our “second skin” for the way it skims the body or hugs it tightly, or as Jennifer Craik explains, “their shared proximity to the body”. Craik goes on to clarify: “The difference is that swimwear takes underwear into the public arena.”Footnote91 In connecting the idea of dress lying “at the margins of the body” to the social world, Joanne Entwistle suggests a “boundary”: one that is “intimate and personal”, but also located between the “individual and society”.Footnote92 This work has encouraged scholars to be attentive to “the way in which dress works on the body which in turn works on and mediates the experience of self”—a call now richly answered by scholars of dress and fashion.Footnote93 For wool underwear and swimsuits to form part of the experience of health, and for them to mediate between wearers and the world, they needed to fit snugly yet comfortably—to move on and with the body, which is where my discussion now turns.

Comfortable in Wool

“In no garments worn by ladies is good fit so important as in Combinations,” the Foy & Gibson catalogues explained over a number of years: “Badly cut they are uncomfortable and spoil the fit of every garment worn over them; well cut they are easy and comfortable and the most satisfactory of all underwear.”Footnote94 Clothes too tight, ill-fitting, stiff or scratchy affected their wearer in negative ways, perhaps all the more for underwear when it acted as a second skin; hence comfort, softness and elasticity were repeated as selling points for men and women across decades.Footnote95 In particular, Foy & Gibson drew a direct line between the softness of its undergarments and use of superior wool, pledging “only the finest soft quality wools are used”.Footnote96

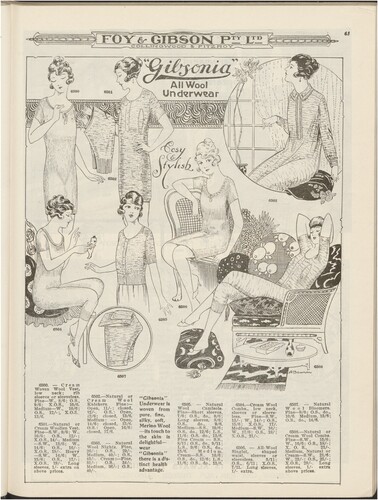

Softness was a tactile experience felt between the fingertips and on the flesh, yet absent from the catalogues was what Gail Reekie describes as the “pleasurable sensual and visual experiences” experienced by in-store shoppers across this period. For delicate underwear, this meant handling the fine fabric then imagining its wear, amplified by “the sights, sounds, smells and sensory pleasures” of display spaces.Footnote97 The catalogues hinted at sensual ease in a different way: through visual and linguistic aids. The 1923 autumn and winter catalogue depicted one woman reclining on a plush chair, her eyes closed in pleasure (). It described the “Gibsonia” underwear that she (and other women illustrated on the page) wore as “woven from pure, fine, silky, soft, Merino Wool—its touch to the skin is delightful”, anticipating the tactile experience for customers.Footnote98 This soft wool gently enfolded the body, enhancing its wearers’ comfort, which extended confidence in their fully dressed state.

Figure 7. Foy & Gibson, Autumn and Winter Catalogue 66 (1923): 65. Foy & Gibson Catalogues, University of Melbourne Archives.

As these dressed bodies moved in the world, growing numbers of increasingly uncovered beach-goers populated the beach. Those who supported women’s sea bathing had been quick to point out that swimming in modest voluminous costumes was “an unseemly farce”. The heavy volume of fabric not only resulted in “a source of continual annoyance to the swimmer” but also clung dangerously when wet.Footnote99 The search for greater comfort on the sand and in the water drove rapid stylistic changes for wool swimsuits, aided by a new elastic stitch designed to hug the body when the suit was wet or dry. In 1930, Foy & Gibson launched its streamlined “Siren” swimsuit for women and men ( and ). The Siren costume came in two cuts, “speed” and “suntan”, the first designed for active use and the second for leisure. In whichever cut the Siren appeared, the catalogue assured purchasers that it gave “the close-fitting effect so desirable in a swimming costume, yet allowing perfect freedom of movement”.Footnote100 Snug wool swimsuits continued to improve with the “Seafit” and the “Swift”.Footnote101 The “perfectly fitting” Swift swimsuit, knitted in a firm elastic ribbed stitch to “retain its shape through long wear”, was also “specially resistant to the fading properties of salt water and sun”.Footnote102

Figure 8. Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 82 (1930–31): 49. Foy & Gibson Catalogues, University of Melbourne Archives.

Figure 9. Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 82 (1930–31): 73. Foy & Gibson Catalogues, University of Melbourne Archives.

By the end of the decade, swimsuit manufacturers such as Sutex began to incorporate “Lastex”—a rubber yarn—into its “perfect form fitting”, shiny, sleek new suits.Footnote103 Swimsuits were no longer just about fit and freedom for their wearers; they were also about glamour. Jantzen tested new fabrics too, but announced it had “been successful in developing glamorous fabrics made from Australian wool”. In 1939, Jantzen announced in an industry journal: “It is the company’s prediction that wool, because of its many desirable qualities, will continue to occupy a place of importance in the swimming suit field.”Footnote104 Foy & Gibson no doubt hoped the same, though in the decades to follow, swimsuits incorporating nylon, polyester and Lycra rose in popularity, overtaking wool’s elastic properties and offering a different experience of beach bathing for the body. Fabrics for garments worn at the crossroads of sports and leisure continued to transform in the pursuit of snug-fitting comfort. That manufacturers remain alert to the centrality of fabrics’ feel, and the experiences this quality opens for wearers, is seen today in the embrace of “feeling premium” in athleisure wear—and in Australian Wool Innovation’s response, urging those consumers to feel merino rather than synthetic alternatives.Footnote105

Conclusion

Foy & Gibson’s next-to-the-skin experience of wool had linked health and comfort to the “purest and best Wool obtainable” from the first years of the 20th century.Footnote106 Its mail order catalogues continued to repeat variations of this wording across the decades that followed. Whether reading about “the purest Merino Wool”, “the finest Australian wool” or similar descriptions, consumers were aware of the excellence of the fibre Foy & Gibson spun into yarn in its mills, wove or knit into cloth, made into clothes, and then sold across the country.Footnote107 The fineness and purity of this wool provided a critical dimension to its interface with the flesh.

Intimately hugging the body as underwear, Foy & Gibson’s wool was emphasised as maintaining health and protecting its wearers from outside (the weather) and internal (perspiration) forces. Indeed, this was nothing new, but it extended on understandings that had emerged the century before connecting pure, natural wool with a healthier body. That Foy & Gibson underlined the Australian origin of its wool aided customers in understanding its beneficial material properties. In swimsuits, however, wool offered a different way of being healthy through an increasingly undressed state, exposing more of the skin to the sun, beach breeze and seawater. Those who wore Foy & Gibson's swimsuits—or those of other brands—embraced beach culture in costumes that enhanced their engagement with leisured activity, promoted new ways of seeing men’s and women’s bodies, rethought notions of modesty, and opened up a new experience of wearing wool linked to a feeling of wellbeing, if not vitality.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 “Feel Merino,” Australian Wool Innovation, https://www.woolmark.com/performance/feel-merino/ (accessed 8 April 2023); Australian Wool Innovation, “New Marketing Campaign: Feel Merino,” Beyond the Bale 85 (2020): 6–8. For more on wool for athleisure wear, see Mark Abernethy, “Demand for Australian Merino Wool on the Rise, Thanks to the Athleisure Market,” Australian Financial Review, 12 June 2018, https://www.afr.com/life-and-luxury/wool-is-fashionable-again-especially-in-the-gym-20180517-h1065k. For a discussion of the rise of athleisure wear, see Jennifer Craik, “‘Feeling Premium’: Athleisure and the Material Transformation of Sportswear,” in Fashion and Materiality: Cultural Practices in Global Contexts, ed. Heike Jenss and Viola Hofmann (London: Bloomsbury, 2020), 214–32.

2 For a mid-century example: Melissa Bellanta and Lorinda Cramer, “‘Well-Dressed’ in Suits of Australian Wool: The Global Fiber Wars and Masculine Material Literacy, 1950–1965,” Fashion Theory (2023), https://doi.org/10.1080/1362704X.2023.2228009.

3 Foy & Gibson, Two Miles of Mills (Melbourne: Foy & Gibson, ca. 1922). History of Foy & Gibson: Annette Cooper, “Foy & Gibson: From the Sheep’s Back to Yours,” La Trobe Journal 106 (2021): 6–22.

4 Foy & Gibson, “Gibsonia” Woollen and Hosiery Mills (Melbourne: Foy & Gibson, ca. 1921), back cover.

5 All Foy & Gibson catalogues referred to in this article are held by the University of Melbourne Archives (see also the business records: 1968.0005 and 2007.0062) and State Library Victoria. Many other Australian department stores produced mail order catalogues: Myer Emporium, Anthony Hordern & Sons, and Grace Bros among them. All sold wide-ranging woollen clothes and underclothes. The Myer Emporium also had its own wool mills that made “Myrall” brand underwear, suitings and more. Myer Emporium, For Autumn & Winter 1927 (1927): 8, 86, 88, 94–5.

6 Prices for women’s clothing, for example, were described as “about half what similar goods made by dressmakers” cost. Foy & Gibson, Winter Catalogue 20 (1902): 15.

7 Foy & Gibson, Winter Catalogue 71 (1925): inside front cover. Today’s superfine merino is a luxury product, though the wool that Foy & Gibson sold in its clothes and underclothes was competitively priced. Its underwear in 1910 was “proved beyond a doubt to be equal to the best imported at about two-thirds of the price”. Foy & Gibson, Winter Catalogue 38 (1910): 69.

8 For example: Lorinda Cramer and Melissa Bellanta, “‘Clothes Shall Mark the Man’: Wearing Suits in Wartime Australia, 1939–1945,” Cultural and Social History 19, no 1 (2022): 57–76; Robert Crawford, “Nothing to Sell?: Australia’s Advertising Industry at War, 1939–1945,” War & Society 20, no. 1 (2002): 99–124.

9 The Draper of Australasia provided “constructive criticism” on department store catalogues, including Foy & Gibson’s: “Make the Advertising Pay,” Draper of Australasia, 30 April 1926, 160; “Make the Advertising Pay,” Draper of Australasia, 30 June 1927, 268; “Aggressive Sale-Time Advertising,” Draper of Australasia, 31 July 1928, 306; “Make Your Advertising Pay,” Draper of Australasia, 31 October 1928, 509.

10 For example: Robert Crawford, “Emptor Australis: The Australian Consumer in Early Twentieth Century Advertising Literature,” Australian Economic History Review 45, no. 3 (2005): 221–329; Robert Crawford, Judith Smart, and Kim Humphery, eds., Consumer Australia: Historical Perspectives (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2010); Jackie Dickenson, Australian Women in Advertising in the Twentieth Century (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016); Gail Reekie, Temptations: Sex, Selling and the Department Store (St Leonards: Allen & Unwin, 1993).

11 Joanne Entwistle, “Fashion and the Fleshy Body: Dress as Embodied Practice,” Fashion Theory 4, no. 3 (2000): 323–47.

12 For example: Lucia Ruggerone, “The Feeling of Being Dressed: Affect Studies and the Clothed Body,” Fashion Theory 21, no. 5 (2017): 573–93; Sophie Woodward and Tom Fisher, “Fashioning through Materials: Material Culture, Materiality and Processes of Materialization,” Critical Studies in Fashion and Beauty 5, no. 1 (2014): 3–22.

13 Rosie Findlay, “‘Such Stuff as Dreams are Made On’: Encountering Clothes, Imagining Selves,” Cultural Studies Review 22, no. 1 (2016): 88–89.

14 Heike Jenss and Viola Hofmann, “Introduction: Fashion and Materiality,” in Fashion and Materiality: Cultural Practices in Global Contexts (London: Bloomsbury, 2020), 1.

15 Marie Hebrok and Ingun Grimstad Klepp, “Wool Is a Knitted Fabric That Itches, Isn't It?,” Critical Studies in Fashion and Beauty 5, no. 1 (2014): 67–93.

16 For example: Jane Schneider, “In and Out of Polyester: Desire, Disdain and Global Fibre Competitions,” Anthropology Today 10, no. 4 (1994): 2–10; Susannah Handley, Nylon: The Manmade Fashion Revolution (London: Bloomsbury, 1999); Kaori O’Connor, “The Other Half: The Material Culture of New Fibres,” in Clothing as Material Culture, ed. Susanne Küchler and Daniel Miller (Oxford: Berg, 2005), 41–60. For plastics more broadly, see Tom H. Fisher, “What We Touch, Touches Us: Materials, Affects, and Affordances,” Design Issues 20, no. 4 (2004): 20–31.

17 Elyse Stanes and Chris Gibson, “Materials That Linger: An Embodied Geography of Polyester Clothes,” Geoforum 85 (2017): 27–36; Elyse Stanes, “Dressed in Plastic: The Persistence of Polyester Clothes,” in Plastic Legacies: Pollution, Persistence, and Politics, ed. Trisia Farrelly, Sy Taffel, and Ian Shaw (Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2021). For the feel of clothes more broadly, see Elyse Stanes, “Clothes-in-Process: Touch, Texture, Time,” Textile 17, no. 3 (2019): 224–45.

18 For example: D. P. Bishop, “Fabrics: Sensory and Mechanical Properties,” Textile Progress 26, no. 3 (1996): 1–62; Maryam Naebe and Bruce A. McGregor, “Comfort Properties of Superfine Wool and Wool/Cashmere Blend Yarns and Fabrics,” Journal of the Textile Institute 104, no. 6 (2013): 634–40; and Joanne N. Sneddon, Julie A. Lee, and Geoffrey N. Soutar, “Exploring Consumer Beliefs about Wool Apparel in the USA and Australia,” Journal of the Textile Institute 103, no. 1 (2012): 40–47.

19 Hebrok and Klepp, “Wool Is a Knitted Fabric That Itches, Isn't It?,” 68.

20 Cecily Close, “Foy, Mark (1830–1884),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/foy-mark-3565/text5515 (accessed 8 April 2023). Other sources suggest that Foy arrived in 1859: “The History of Foy and Gibson,” in Miss Smith Street (Collingwood: Smith Street Traders’ Association, ca. 1950), 14.

21 “Summer Fair,” Gibsonia Gazette (January 1927): 1; “Store Histories – Foy & Gibson Ltd.,” Retail Merchandiser (February 1966): 5.

22 “On Sale,” Mount Alexander Gazette, 28 October 1862, 3.

23 First appearing: “Summer Has Arrived,” Bendigo Advertiser, 4 November 1867, 1.

24 First appearing: “Commercial Intelligence,” Bendigo Advertiser, 13 May 1868, 1.

25 On diggers’ dress: Margaret Maynard, Fashioned from Penury: Dress as Cultural Practice in Colonial Australia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 168–70.

26 First appearing: “Summer Having Now Fairly Set in,” Bendigo Advertiser, 17 November 1868, 1.

27 Foy & Gibson, Welcome to Foys (Melbourne: Foy & Gibson, 1963), 1.

28 First appearing: “Attractive Display of Drapery,” Age, 26 April 1873, 3.

29 First appearing: “To the Ladies of Victoria,” Weekly Times, 22 March 1873, 16.

30 “Foy and Gibson’s Winter Fair,” Argus, 10 July 1891, 1; “Foy and Gibson’s Winter Fair,” Age, 10 July 1891, 1.

31 David Merrett and Simon Ville, “Industry Associations and Non-Competitive Behaviour in Australian Woolmarketing: Evidence from the Melbourne Woolbrokers’ Association, 1890–1939,” Business History 54, no. 4 (2012): 517–18.

32 Foy & Gibson, Two Miles of Mills, 7.

33 Foy & Gibson, Two Miles of Mills, 7.

34 Foy & Gibson, Two Miles of Mills, 27.

35 Foy & Gibson, Autumn and Winter Catalogue, Adelaide (1929): 16c. (This Adelaide catalogue does not bear a print number; however, it is likely to be 46 given the Autumn and Winter 1930 catalogue is 48, and there would have been a Spring and Summer catalogue between them.)

36 Foy & Gibson, Autumn and Winter Catalogue, Adelaide 48 (1930): inside front cover.

37 The Companies Acts, Companies Limited by Shares, Memorandum and Articles of Association of Foy & Gibson Proprietary Limited (Melbourne: Anderson, Gowan Pty Ltd, 1936), 3–4.

38 For a small sample of a much larger body of research, see Charles Massy, The Australian Merino: The Story of a Nation (North Sydney: Random House, 2007, rep. 1990); David Merrett and Simon Ville, “Accounting for Nonconvergence in Global Wool Marketing before 1939,” Business History Review 89 (2015): 229–53; Kosmas Tsokhas, Markets, Money and Empire: The Political Economy of the Australian Wool Industry (Carlton, VIC: Melbourne University Press, 1990); Simon Ville and David Merrett, “Too Big to Fail: Explaining the Timing and Nature of Intervention in the Australian Wool Market, 1916–1991,” Australian Journal of Politics and History 62, no. 3 (2016): 337–52.

39 Reviewer, “Wool at the Moment,” Textile Journal of Australia 2, no. 2 (14 April 1927): 106.

40 “The Wool Market,” Textile Journal of Australia 2, no. 1 (15 March 1927): 8–9.

41 Australian Wool Board, First Annual Report of the Australian Wool Board, Dated 31st July, 1937 (Canberra: L. F. Johnston, Commonwealth Government Printer, 1937), 5, 7. For Australian Wool Board wool promotional activities, see Tiziana Ferrero-Regis, “From Sheep to Chic: Reframing the Australian Wool Story,” Journal of Australian Studies 44, no. 1 (2020): 48–64; Prudence Black and Anne Farren, “The Wool Industry in Australia,” Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion, Volume 7, Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific Islands, ed. Margaret Maynard (Oxford: Bloomsbury, 2010), 100–5.

42 Donald Coleman, “Man-Made Fibres before 1945,” The Cambridge History of Western Textiles, Vol. 2, ed. David Jenkins (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 942–44.

43 “News of the Day,” Age, 8 January 1926, 8; “New Textiles: Germany’s Substitutes,” Sun, 29 August 1934, 13; “Wool Publicity,” Textile Journal of Australia 10, no. 12 (15 February 1936): 550.

44 Madelyn Shaw and Trish FitzSimons, “Fabric of War: The Lost History of the Global Wool Trade,” Selvedge 90 (2019): 10–18.

45 “‘Wool’ from Seaweed,” Textile Journal of Australia 14, no. 1 (15 March 1939): 47.

46 “Synthetics versus Wool: Test Tube Challenge to Merino,” Pix, 11 December 1943, 27.

47 Coleman, “Man-Made Fibres before 1945,” 933; Jeffrey Harrop, “Man-Made Fibres since 1945,” The Cambridge History of Western Textiles, Vol. 2, ed. David Jenkins (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 950; “Product like Silk Made from Coal, Air, Water,” Textile Journal of Australia 14, no. 2 (1939): 58.

48 Regina Lee Blaszczyk. “Styling Synthetics: DuPont’s Marketing of Fabrics and Fashions in Postwar America,” Business History Review 80, no. 3 (2006): 485–528; Handley, Nylon; Schneider, “In and Out of Polyester,” 4.

49 House of Representatives, Official Hansard, No. 38, 20 September 1944, 1087. See also: Hannah Rose Shell, Shoddy: From Devil’s Dust to the Renaissance of Rags (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020).

50 “Wool Adulteration: Practical Step by Manufacturer,” Draper of Australasia 39, no. 7 (1939): 72; “Union Knitting Mills,” Draper of Australasia 40, no. 10 (1939): iii. The Australian Wool Board’s first annual report recognised this problem: Australian Wool Board, First Annual Report of the Australian Wool Board, 6.

51 “Name of ‘Wool’,” Textile Journal of Australia 14, no. 6 (1939): 254–55.

52 “Defining Pure Wool Goods,” Textile Journal of Australia 14, no. 6 (1939): 267.

53 For example, see Legislative Council and Legislative Assembly of New South Wales, Textile Products Labelling Act 1945, https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/pdf/asmade/act-1945-13 (accessed 8 April 2023).

54 “Measures to Prevent Fraud in Woollens,” Sun, 20 April 1944, 2; “Wool Board Critical on Textiles Labelling,” Sydney Morning Herald, 17 October 1952, 2; Australian Wool Board, Annual Report 1952–53 (Melbourne: Australian Wool Board, 1953), 5, 8–9.

55 Australian Wool Board, Annual Report 1950–51 (Melbourne: Australian Wool Board, 1951), 8.

56 For example, the Gowing Bros bill of sale and self-measurement form in the collection of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, https://collection.maas.museum/object/251548 and https://collection.maas.museum/object/159874 (accessed 8 April 2023).

57 “Golden Fleece All Australian Underwear,” Textile Journal of Australia 2, no. 9 (15 November 1927): back cover.

58 “Empire Shopping Week in West Australia,” Draper of Australasia, 31 July 1930, 349.

59 Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 67 (1923–24): 107; Foy & Gibson, Winter Catalogue 38 (1910): 69; Foy & Gibson, Autumn and Winter Catalogue 69 (1924): 125; and Foy & Gibson, Autumn and Winter Catalogue, Brisbane (1929): 35.

60 Foy & Gibson, Winter Catalogue 38 (1910): 26; Foy & Gibson, Summer Catalogue 39 (1910–11): 26; Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 41 (1911–12): 26; Foy & Gibson, Autumn and Winter Catalogue 42 (1912): 26; Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 43 (1912–13): 26; Foy & Gibson, Autumn and Winter Catalogue 44 (1913): 26. Men’s underwear was likewise described in these terms: Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 55 (1918–19): 73.

61 Lydia Edwards, How to Read a Dress: A Guide to Changing Fashion from the 16th to the 20th Century (London: Bloomsbury, 2017), 123–27.

62 Foy & Gibson, Winter Catalogue 38 (1910): 69.

63 Prudence Black et al., “What Lies Beneath? Thoughts on Men’s Underpants,” Critical Studies in Men’s Fashion 1, no. 2 (2014): 134. For more of the layers beneath, specifically singlets, see Jess Berry, “The Underside of the Undershirt: Australian Masculine Identity and Representations of the Undershirt in the ‘Chesty Bond’ Comic-Strip Advertisements,” Critical Studies in Men’s Fashion 1, no. 2 (2014): 147–59; Lorinda Cramer, “Rethinking Men’s Dress through Material Sources: The Case Study of a Singlet,” Australian Historical Studies 52, no. 3 (2021): 420–42.

64 For more on the gendered rendering of bodies in mail order catalogues, see Reekie, Temptations, 137–42.

65 “‘Reason Why’ Copy,” Draper of Australasia, 31 March 1927, 115; Reekie, Temptations, 176.

66 Foy & Gibson, Winter Catalogue 38 (1910): 69; Foy & Gibson, Winter Catalogue 54 (1918): 81.

67 Foy & Gibson, Autumn and Winter Catalogue (1935): 37.

68 “Monthly Advertising Review,” Draper of Australasia, 27 April 1912, 165.

69 Foy & Gibson, Autumn and Winter Catalogue 66 (1923): 94.

70 Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 67 (1923–24): 66; Foy & Gibson, Autumn and Winter Catalogue 69 (1924): 73.

71 Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 67 (1923–24): 106.

72 Foy & Gibson, Winter Catalogue 77 (1928): 69; Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 67 (1923–24): 67; and Foy & Gibson, Autumn and Winter Catalogue 69 (1924): 73.

73 Foy & Gibson, Winter Catalogue 73 (1926): 76; Foy & Gibson, Summer Catalogue 74 (1926–27): 76.

74 Susan North, Sweet and Clean? Bodies and Clothes in Early Modern England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

75 Shaun Cole, The Story of Men’s Underwear (New York: Parkstone International, 2011), 52–53.

76 Gustav Jaeger, Dr Jaeger’s Health Culture, enlarged and revised ed., trans. and ed. Lewis R. S. Tomalin (London: Waterlow and Sons Limited, 1887), 117. Jaeger went further, insisting it was “not enough to wear wool next to the skin, and any other material over it”. Rather, only wool should be worn to permit exhalations when “the noxious portion of the exhalation settles in the vegetable fibre”. Jaeger, Dr Jaeger’s Health Culture, 118.

77 Cole, The Story of Men’s Underwear, 54.

78 Foy & Gibson, Summer Catalogue 57 (1919–20): 77; Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 80 (1929–30): 71; Foy & Gibson, Autumn and Winter Catalogue, Adelaide 48 (1930): 64.

79 Jill Julius Matthews, “They Had Such a Lot of Fun: The Women’s League of Health and Beauty between the Wars,” History Workshop 30, no. 1 (Autumn 1990): 22–54.

80 Charlotte Macdonald, Strong, Beautiful and Modern: National Fitness in Britain, New Zealand, Australia and Canada, 1935–1960 (Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, 2011).

81 Walter E. Withrow, “The Editor’s Foreword,” Withrow’s Physical Culture Magazine (1920): 5.

82 Dame Fashion, “The Flight of Fashion, Month by Month, December 1926,” Gibsonia Gazette 4 (December 1926): 6. The Gibsonia Gazette combined “home hints” with its catalogue pages. According to the Draper of Australasia, it was so strong in “the technique and essentials of good advertising” that they could “offer no suggestions for improvement”. See “Make the Advertising Pay,” Draper of Australasia, 31 May 1927, 228.

83 For example: Douglas Booth, “Swimming, Surfing and Surf-Lifesaving,” in Sport in Australia: A Social History, ed. Wray Vamplew and Brian Stoddart (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 231–54; Jennifer Craik, “Swimwear, Surfwear, and the Bronzed Body in Australia,” Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion, Volume 7, Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific Islands, ed. Margaret Maynard (Oxford: Bloomsbury, 2010), 113–20.

84 Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 78 (1928): 81; Kay Saunders, “‘Specimens of Superb Manhood’: The Lifesaver as National Icon,” Journal of Australian Studies 22, no. 56 (1998): 96–105.

85 Stephen Garton, The Cost of War: Australians Return (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1996); Marina Larrson, Shattered Anzacs: Living with the Scars of War (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2009); Saunders, “‘Specimens of Superb Manhood’,” 96–7.

86 Saunders, “‘Specimens of Superb Manhood’,” 97.

87 Dame Fashion, “The Flight of Fashion, Month by Month, December 1926,” Gibsonia Gazette 4 (1926): 6.

88 Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 41 (1911–12): 15; Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 43 (1912–13): 84.

89 Foy & Gibson, Summer Catalogue 74 (1926–27): 74.

90 This corresponds with Reekie’s finding that men appeared active in mail order catalogues “in contrast to women who appeared to be almost exclusively creatures of leisure”. Reekie, Temptations, 140.

91 Entwistle, “Fashion and the Fleshy Body,” 334; Jennifer Craik, The Face of Fashion: Cultural Studies in Fashion (London: Routledge, 1994), 136.

92 Entwistle, “Fashion and the Fleshy Body,” 327.

93 Entwistle, “Fashion and the Fleshy Body,” 334.

94 Foy & Gibson, Winter Catalogue 38 (1910): 26; Foy & Gibson, Summer Catalogue 39 (1910–11): 26; Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 41 (1911–12): 26; Foy & Gibson, Autumn and Winter Catalogue 42 (1912): 26; Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 43 (1912–13): 26; Foy & Gibson, Autumn and Winter Catalogue 44 (1913): 26.

95 Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 55 (1918–19): 73; Foy & Gibson, Winter Catalogue 77 (1928): 69; Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 80 (1929–30): 47; Foy & Gibson, Autumn and Winter Catalogue 81 (1930): 34; Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 82 (1930–31): 42; and Foy & Gibson, Winter Catalogue 83 (1931): 24.

96 Foy & Gibson, Winter Catalogue 73 (1926): 50; Foy & Gibson, Summer Catalogue 74 (1926–27): 26. And a variation in Foy & Gibson, Winter Catalogue 75 (1927): 22.

97 Reekie, Temptations, 83.

98 Foy & Gibson, Autumn and Winter Catalogue 66 (1923): 65.

99 Walter E. Withrow, “Bathing Costumes and Bathing Customs,” Withrow’s Physical Culture (January 1924): 11.

100 Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 82 (1930–31): 73.

101 Foy & Gibson, Christmas Bargain Carnival (1935): 12.

102 Foy & Gibson, Spring Catalogue (1934): 28.

103 “Men’s Swim Suits,” Draper of Australasia 39, no. 6 (1939): 41.

104 “Jantzen Reports Many Changes in Swim Suits,” Textile Journal of Australia 14, no. 5 (1939): 221.

105 Craik, “‘Feeling Premium’,” 214–32.

106 Foy & Gibson, Winter Catalogue 20 (1902): 52; Foy & Gibson, Catalogue 29 (ca. 1906): 58; Foy & Gibson, Summer Catalogue 30 (1906–7): 59; Foy & Gibson, Winter Catalogue 38 (1910): 69.

107 Foy & Gibson, Summer Catalogue 64 (1922): 78; Foy & Gibson, Spring and Summer Catalogue 78 (1928): 71; and Foy & Gibson, Winter Catalogue 83 (1931): 33.