ABSTRACT

The 1961 Recent Australian Painting exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London is an important and much-discussed moment in Australian art history. It is when the idea of Australian art as “isolated” and “exotic” first became popularised in both British and Australian cultures. The prominent Australian art historian Bernard Smith criticised the idea, but in many ways his book Australian Painting, published the year after, repeated the assumption. What is overlooked in accounts of the show is that many of its artists were not “isolated”, frequently having spent extended periods in Britain living and studying. But, more than this, what is rarely, if ever, discussed is how many of the artists in the show were queer, as was its curator, the director of the Whitechapel Gallery, Bryan Robertson. In many ways, the social and professional connections between Australian and British artists were forged through their shared homosexuality. It is this that puts Australian artists in connection with the British art scene and, on occasion, explains their influence upon it. Queerness has often connected Australian artists to those around the world—it is also the case for the Australian women artists in Paris before and after World War I.

The Recent Australian Painting show that opened at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in June 1961 is an important and much-discussed moment in Australian art history. It is the exhibition Australian art historian Bernard Smith wished he’d been able to write the catalogue for—he had earlier curated The Antipodeans in Melbourne in 1959, which he regarded as something of an inspiration for it, and helped its curator, Bryan Robertson, in 1960 when he was in Australia. Smith responded to the exhibition by delivering the famous polemic “The Myth of Isolation” as the inaugural Macrossan Lecture at the University of Queensland, which correctly diagnosed the hidden desire of English curators and art historians to understand Australian art as something exotic coming from far away with little connection to recent developments in European art. For Robertson, one of the chief English architects of this myth, Australia had a “lack of any aesthetic tradition with roots”,Footnote1 and in the catalogue he opined that it is “the very real isolation of many Australians [that] gives a special edge to whatever is created [there]”.Footnote2 Indeed, for the exhibition opening, he dressed the Whitechapel full of tropical plants and trees, a staging intended to evoke this fantasy. The other catalogue writers, Kenneth Clark and Robert Hughes, largely echoed Robertson, with Hughes, for example, speaking of “our complete isolation from the Renaissance tradition, and, parallel with that, a similar isolation from most of what happens now in world art”.Footnote3

But what nobody pointed out was just how many of the artists in Recent Australian Painting were effectively English artists. Barbara Blackman, wife of the artist Charles Blackman who was in the show, wrote in her diary of the easy familiarity between the Australian and English art worlds evident at the dinner after the opening where she “sat next to Bryan Robertson, who curated it all … The Boyds, the Underhills, Keith Vaughan, Prunella Clough, Francis Bacon, Brett Whiteley, Roy de Maistre, all there”.Footnote4 Also at the dinner was the New Zealand gallerist and collector Rex Nan Kivell; his Australian gallery partner, Harry Tatlock Miller, was in all likelihood in attendance as well. Indeed, there were many Australian artists in the show who were either living in England at the time or had spent extended periods of time there. Roy de Maistre had been living in England since 1930, Sidney Nolan since 1953, Loudon Sainthill in 1939 and then again from 1949, Donald Friend between 1936 and 1938 and then again between 1949 and 1950 and yet again between 1952 and 1953, William Dobell between 1929 and 1938, John Passmore between 1933 and 1950 and again in 1960, James Gleeson between 1947 and 1949 and the New Zealand-born Godfrey Miller between 1929 and 1931 and then from 1933 until 1938.

Smith was undoubtedly right. There was a “myth of isolation” surrounding the artists in the show, but it was a double one: the English regarded them as coming from far away and embodying a different sensibility, while Australian art history, as it had always done with its expatriates, had largely ignored them, or at least those years they spent overseas, understanding that when they left the country they could no longer be regarded as Australian artists. In fact, and ironically, just one year later Smith could be accused of doing the same thing, speaking in his Australian Painting of the artists who left Australia after the Heidelberg School in terms of an “exodus”, before having them return in a biblical “Leviticus”, thereby writing out a generation of Australian women artists who lived and worked in Paris before and after World War I.

But the truly unspoken, and perhaps even unspeakable, thing about Recent Australian Painting, in part explaining that easy familiarity between participants and guests at the opening, is that so many of those involved were queer. De Maistre, Sainthill, Friend, Miller, Passmore, Dobell, Gleeson, Nan Kivell and Tatlock Miller were all queer. So, of course, was Bacon, although that doesn’t entirely explain his presence at the dinner. (His father was in fact Australian, but Bacon—otherwise the most open and transgressive of queer men—would never admit to that shameful fact.) So, finally, was the curator of the show and director of the Whitechapel, Bryan Robertson. And even, arguably, was that depictor of bushrangers and the soldiers of Gallipoli and more particularly the nude sunbathers of the St Kilda baths, Sidney Nolan.

In this article, we seek to trace the extensive history of the queer male Australian artists in London from the 1930s onwards as not only a lost line of Australian art history but a lost story in English art history as well. Indeed, in many ways, we might compare these men in London with that generation of queer Australian women who lived in Paris—for example, Agnes Goodsir, Janet Cumbrae Stewart, Anne Dangar, Bessie Davidson, Grace Crowley, Kathleen O’Connor and Mary Cockburn Mercer—who have similarly, at least until recently, largely been left out of Australian art history.Footnote5 It is important to think about why both groups decided to leave Australia to pursue their artistic ambitions and why they felt the increasingly nationalistic Australia of the post–World War I era was not for them. It is undoubtedly to say something about Australian art and culture more generally at the time, as well as pointing towards the comparative tolerance of so-called “Sapphic” Paris and the “anonymity”, in Patrick White’s words, of interwar London. As he writes in his autobiography, “Anonymity was anybody’s right in a city like London, whereas in the village life of Sydney before World War II it would not have been possible.”Footnote6

We are right, as Smith suggests, to challenge the myth of “isolation”, the idea that Australian art and artists were somehow separate from the rest of the world. But it is also important to challenge the myth of “heterosexuality”. This overseas story is not just about some artists who happened to be queer. Rather, these artists knew of each other and were consciously creating both an alternative Australian art history and Australia together. They connected Australian art with that of the rest of the world, thereby dispelling the myth of isolation, and it was their sexual orientation as much as their art that put them in contact with artists from around the world. The real question here is whether this is actually an “Australian” art history any more. A queer art history challenges the assumption of a bounded Australian identity both because “Australian” art history definitionally excludes queer—precisely by not mentioning it—and because the artists themselves form part of a transnational queer community.

In what follows, we trace the presence of queer Australian artists over three decades in London and examine their personal relationships at once with each other and with other artists in England. Although they do not all know each other, they do know of each other and there are indisputably many close connections between them. And this, we say, is important. It is not for us merely a matter of acknowledging them and pointing out their presence, as the recent exhibitions Queer at the National Gallery of Victoria and Know My Name at the National Gallery of Australia arguably did. Rather, it is important for us to describe the artists’ relationships, their scene and their awareness of each other. If we write their history here for the first time, therefore, it is a history of which they were already aware. It is not a matter of a number of disaggregated male artists heading off alone as though for the first time. As with the women in Paris, they consciously knew of the expatriate possibility and passed this knowledge on from artist to artist. So that, if this is a certain non-national story, it is not a recent creation by art historians in the 21st century coming after contemporary global art but one consciously lived out by Australian artists in the mid-20th century. This is significant, for if, as others suggest, it was important for these queer men to know of others who shared their sexual orientation, it was also important for them as artists to know there were other artists like them. Indeed, our point in this essay is that the two possibilities cannot be separated, with each making the other possible. To break down the “myth of isolation” is to dismantle the “myth of heterosexuality” and vice versa. And both might be summed up in the epithet “UnAustralian”.

* * *

We start in 1929 with William Dobell’s arrival in London and enrolment at the Slade School of Fine Art. In the studios there he soon met the renowned Dutch pianist, writer and artist Rient van Santen, who, after originally training in art in Antwerp and studying singing in Berlin, gained fame with his musical performances and such publications as De piano en hare componisten (1925) and Debussy (1926). In the summer of 1930, van Santen invited Dobell to stay at his house in Den Haag with him and his partner, the composer Bernhard van den Sigtenhorst Meyer; while in the Netherlands, Dobell went to see the exhibition Van Gogh and His Contemporaries at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, where he is said to have stood in front of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers for an hour. But eventually, in the words of Dobell’s biographer Brian Adams, van Santen’s “stolid formality and rigid lifestyle made the visit pall”, and in this way, “Rient van Santen became another name on the list of associations and relationships that punctuated Dobell’s life and then were forgotten”.Footnote7

The same year as Dobell, Godfrey Miller also left Australia and enrolled at the Slade. Originally from Wellington, New Zealand, Miller had served in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force and suffered a badly wounded arm at Gallipoli. Following his repatriation, he moved to Melbourne, where he studied at the National Gallery School, and eventually joined the Victorian Artists Society before heading to London. It was probably at the Slade that he met Dobell, and the two subsequently shared the cost of models and sketched together in the 1930s. Miller graduated with a certificate in sculpture in 1931 but returned to Melbourne that year.Footnote8 In 1933, at almost 40 years of age, the independently wealthy Miller then went back to London and re-enrolled part-time in sculpture at the Slade, where he also took drawing classes in the years leading up to his final return to Sydney in 1938. During this time, he joined the Royal Institute of Philosophy in 1935 (it appears he may have met de Maistre there), attended the landmark International Surrealist Exhibition in 1936, became a theosophist and, again unable to marry, broke up his second engagement. But his time in London had been decisive for him. In the words of Miller scholar Ann Wookey, “He had arrived in London a conservative naturalistic painter, grounded in nineteenth-century artistic traditions, [but] left a fully-fledged modernist.”Footnote9

The year after Dobell and Miller came to London also saw the arrival of Roy de Maistre soon after the success of his Burdekin House Exhibition in Sydney, for which he had designed furniture and the interior of a “man’s bedroom” in a style that can only be called luxe. Then, within three months of his arrival, he had a solo exhibition at the Beaux Arts Gallery in London, followed four months later by a shared exhibition of Paintings by Roi de Mestre, Drawings and Pastels by Jean Shepeard, Paintings and Rugs by Francis Bacon, which was held at Bacon’s studio at 17 Queensbury Mews. Indeed, the first work in the exhibition catalogue was de Maistre’s Portrait of Francis Bacon (with the subject wearing his signature make-up), and Shepeard also draws Bacon as well as de Maistre (). The exact nature of the relationship between de Maistre and Bacon has for a long time been a complicated question. On the one hand, Bacon always insisted that “he had ‘never shared a studio or anything else’ with de Maistre”,Footnote10 and “close friends of de Maistre state categorically that de Maistre never intimated that he had been a sexual partner of Bacon”.Footnote11 On the other hand, according to Martin Harrison and Rebecca Daniels, the former the editor of Bacon’s catalogue raisonné, “it is likely that the relationship between Bacon and de Maistre was, briefly at least, sexual”.Footnote12 Regardless, according to Bacon biographer Daniel Farson, de Maistre was one of the few men of whom Bacon spoke with unreserved affection, and it is widely acknowledged that Bacon acquired many of his later work habits—particularly the habit of shutting the doors to everyone while working—from de Maistre.Footnote13 More than this, it is undoubtedly true that much of Bacon’s early style is heavily indebted to de Maistre. Not only did de Maistre spark the then designer (of rugs, stools and, as we will see later, desks) into painting, but Bacon began by largely imitating de Maistre. We need only compare, for instance, Bacon’s Screen (c. 1933) with de Maistre’s Studio Interior (1931) to see this, or wonder about the relationship between de Maistre’s Annunciation (before November 1934) and Bacon’s Crucifixion of 1933. But most remarkably—and this has emerged only recently—what perhaps drew Bacon to de Maistre and any number of other Australians throughout his life is the fact that his father, Anthony Edward “Eddy” Mortimer Bacon, was born in Adelaide. This “Australianness” was perhaps the truly unspoken fact about Bacon’s life and career, both for Bacon himself and for generations of English critics and historians, who have largely overlooked his early relationship with de Maistre and the undeniable influence of de Maistre on his work

Figure 1. Roy de Maistre, Portrait of Francis Bacon, 1930, oil on board, 64.5 × 41.5 cm. Reproduced courtesy of Deutscher and Hackett and by permission of Caroline de Mestre Walker and Joanna Green.

Figure 2. Francis Bacon, Study from the Human Body, 1949, oil on canvas, 147.2 × 130.6 cm. Reproduced by permission of Francis Bacon DACS/Copyright Agency.

It is now the moment to introduce the New Zealand art dealer and collector Rex Nan Kivell, who, having worked for the Redfern Gallery, became its director in 1931 and oversaw its move to Cork Street, Mayfair, in 1936. As part of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force, Nan Kivell served in England during World War I, but saw no action and was not, as he claimed, gassed. Like de Maistre, who was introduced to the London public as Roi de Mestre and who eventually settled on Roy, Nan Kivell remade himself after the war into something less “colonial”. Born in Christchurch in 1898, where his birth certificate has him as Reginald Nankivell, he restyled himself after the war as Rex De Charembac Nan Kivell. In 1925 he began working at the Redfern Gallery, which had been founded in 1923 and was then operating out of Old Bond Street in the West End, before taking over the business six years later. It was perhaps his Antipodean roots that led him to employ Coleraine-born Alleyne Clarice Zander in 1930, but it was more likely because of her contacts. She was, after all, the partner of the famous Australian black-and-white artist Will Dyson and would also go on to curate the landmark exhibition British Contemporary Art, which toured Sydney and Melbourne in 1933, sparking the so-called Zandrian Wars as the Australian public took in its first taste of then contemporary British art (although the show included, of course, numerous hidden Australian artists, such as Derwent Lees). With Zander’s help, Nan Kivell made the Redfern into one of Britain’s leading galleries, whose inclination towards French artists marked it as modern in the London of the 1930s. It was as much a gallery for the camp photographs of Cecil Beaton as it was for the “masked” faces in Loudon Sainthill’s pictures of the Ballet Russes in 1939 and Sidney Nolan’s second Ned Kelly series in 1955. Nan Kivell himself had a penchant for “cruising during the early years of the war in his Rolls Royce, a New Zealand flag flying on its bonnet, with the Duke of Kent, a one-time lover of Noel Coward’s, in the passenger seat: ‘They’d pass a bomb site where workmen were clearing rubble, spot the prettiest, scoop him up and go back to the coal cellar at the Redfern in Cork Street for a spot of fucking.’”Footnote14 He was knighted in 1976, having bequeathed his extensive collection of colonial art and other material to the National Library of Australia, a gift that “has exercised a substantial and enduring influence on Australasian historical and artistic scholarship”.Footnote15

Having introduced one gallerist who was also a collector, we now introduce a collector who was also a gallerist. In 1932, at the age of 21, the diasporic Australian Douglas Cooper came into a considerable inheritance derived from the wealth his family had amassed in Sydney during the 19th century from property, gold and alcohol. His family built and lived in the well-known “Juniper Hall” on Oxford St, Paddington, and the present-day Cooper Park in Double Bay lies at the foot of what was once known as the Cooper Estate. Indeed, his grandfather was, of all things, the third baronet of Woollahra. Nonetheless, his parents returned, just before Federation, to England, where Cooper was educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, before studying art history at the Sorbonne and the University of Freiburg, thus acquiring great fluency in a number of European languages. As with other figures in our history, as a young man he was struck by the Ballet Russes, having attended a performance in Monte Carlo in 1930. With his inheritance in his pocket, he decided to devote a third of his fortune to collecting that first period of Cubism developed by Picasso, Braque, Gris and Léger, which he came to call the “Essential Cubism”. As John Richardson, Cooper’s long-time partner and later author of the four-volume Picasso biography, wrote in 1985 after his death, Cooper was important for art history in that “he was the first person to study and collect [early] Cubist works”.Footnote16 (We will not go here into his so-called war with the Tate, which led to his punching its director over their policy of buying overpriced British art instead of his beloved Cubists, or his work as a “monument man” during World War II, which ultimately led to his being stopped from interrogating captured Nazis accused of dealing in looted art because of his penchant for sadistic violence.)

The last figures we introduce are the Sydney painter John Passmore and the Auckland artist Felix Kelly. Passmore arrived in England in 1933, having left his wife of five years and three-year-old child behind. According to the curator of his 1984 retrospective, Barry Pearce, it was an “unhappy relationship from the beginning”.Footnote17 On his arrival in London, Passmore was met by his old friend from art school, Dobell, and subsequently stayed at his flat in Bayswater for several weeks, where “each morning they would model for each other”.Footnote18 Indeed, Passmore is said to be the model for Dobell’s Boy Bathing (1939) as well as for Boy Washing (c. 1933) (men bathing, either privately or publicly, is a subject shared among the artists we consider here).Footnote19 The 28-year-old Passmore then almost immediately found work as a commercial artist for Lintas, the advertising arm of Unilever, where he soon became “close friends” with the English painter Keith Vaughan,Footnote20 who was eight years his junior, and befriended the queer New Zealand painter, illustrator and muralist Felix Kelly. Unilever House, just by Blackfriars Bridge in central London, was only completed in 1933, and its commercial art studio quickly drew an array of young male artists, many of them queer, celebrated in the exhibition Beyond the Horizon—A Collection of Paintings from Artists Who Worked at the Lintas Advertising Agency 1930–1950 at Thomas Agnew and Sons in 1988.Footnote21 For Pearce, “Vaughan idolised Passmore and, to a certain extent, Passmore reciprocated his attention”,Footnote22 and Passmore is “remembered by colleagues at Lintas as being snappily dressed with a penchant for orange or yellow knitted ties against vivid shirts, his whistling of Rimsky-Korsakov’s ballet music at his desk and a shy, courteous manner that kept others at a distance”.Footnote23 For his part, Passmore remembers Vaughan’s love of music and his dancing, which “was such a brilliant thing. He was very close to a Diaghilev dancer”.Footnote24 Indeed, Passmore much later confessed that Vaughan was “the biggest influence of anyone in my life”, and when he eventually departed for Sydney in late 1950 he was leaving a large house in St John’s Wood where both he and Vaughan (and others) had rooms.Footnote25

For his part, the 21-year-old Felix Kelly had arrived in 1935 and also almost immediately found work at Lintas. Later in 1943 he held his first exhibition at the Lefevre Gallery (the same gallery where Vaughan first showed), and it was from this exhibition that Herbert Read bought his Three Sisters (1943). The work in Kelly’s second exhibition at the Lefevre in 1944 tended towards a kind of neo-Romantic surrealism and was shown in an adjoining room to Julian Trevelyan and Lucian Freud. After the war, he began to make a name for himself on both sides of the Atlantic as a muralist and painted, for instance, on the walls of the Royal Palace in Kathmandu, Nepal, as well as on the interiors of numerous ships of the Cunard Line. In the 1950s Kelly also worked as a scenographer for the ballet and stage at the Old Vic and Sadler’s Wells theatres and was the illustrator of the dust jackets for Faber and Faber’s Best Horror Stories (1957) and Best Tales of Terror (1962). In the 1980s, he was approached by the then Prince of Wales to reimagine the prince’s Highgrove House in Gloucestershire, and his drawings and paintings of that pile became the basis of the now King’s remodelling of the house, all of this a long way from his arrival from Auckland with his mother some 50 years earlier.

Nineteen thirty-three was quite a year for Dobell and de Maistre: Dobell was included in the annual Royal Academy exhibition, the first time his work was shown in Britain, while de Maistre’s painting was reproduced in the then up-and-coming art critic and historian Read’s influential bestseller, Art Now, and was included in the exhibition 20th Century Art, as it became known, at the reopened Mayor Gallery. His inclusion in both was likely due to the influence of the gallery’s new part-owner, Douglas Cooper. In 1934 the great German Jewish gallerist Alfred Flechtheim, then a newly arrived refugee in his mid-50s, became a silent co-director, and it was from this point on that the Mayor became the leading gallery for modern art in London (). Flechtheim knew the first generation of Cubist art dealers, such as Ambroise Vollard and Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, and was well connected to artists, dealers and institutions around Europe. These relationships facilitated Cooper’s entrée as collector to the French art world and, by the 1950s, had helped him to procure, in the words of Richardson, “the finest collection of modern art in England”.Footnote26 But, more than their shared love of modern art, it was, as Charles Dellheim writes in Belonging and Betrayal: How Jews Made the Art World Modern, “the common ground they shared in taste, style, manner and, not least, sexual preferences” that brought the pair together.Footnote27

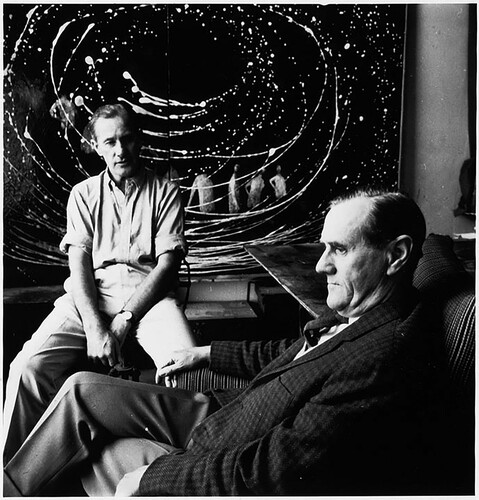

Figure 3. Douglas Cooper with Alfred Flechtheim, Paris, 1937. Photo by John Richardson. Reproduced courtesy of alfredflechtheim.com.

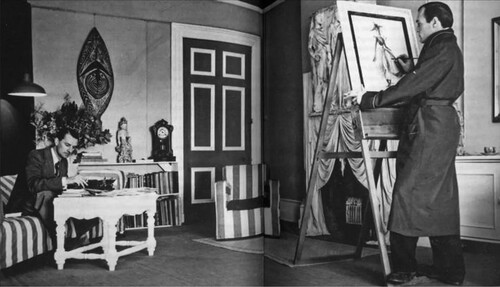

In many ways, 1934 was the apex of Roy de Maistre’s career. In that year, he held his own one-person exhibition at the Mayor Gallery and opened the School of Contemporary Painting and Drawing in Kensington together with another German Jewish refugee, the painter Martin Bloch. It is around this time, too, that he began, in the words of his biographer Heather Johnson, “a large body of work” depicting “fellas doing things to fellas”, which was later destroyed after de Maistre’s death at his request by his executors.Footnote28 It wasn’t until 1936 that de Maistre met Patrick White when they evidently bumped into each other on Ebury Street, where de Maistre had moved the year before. White had originally left Australia in 1932, aged 20, to enrol in King’s College Cambridge, where he studied modern languages, before graduating in 1935. Moving down to London, White roomed first at 68 Ebury St and then not long after at 104 Ebury St. Following his chance encounter with de Maistre, White recalls in his autobiography that “I fell in love very quickly”,Footnote29 and de Maistre “became what I most needed, an intellectual and aesthetic mentor. He taught me how to look at paintings, to listen to music. From what Francis told me [later], his own experience was similar”.Footnote30 And it was not just Bacon whom White met through de Maistre. White recalled meeting other “more or less important people” at de Maistre’s studio, including Henry Moore, Graham Sutherland and Douglas Cooper.Footnote31 And—as de Maistre did with Bacon’s move away from interior design to painting—the older man encouraged the younger White to stop writing plays and start writing novels. Indeed, White’s first book, Happy Valley, published in 1939, featured endorsements from Graham Greene and Herbert Read, and was, for some critics, Book of the Day, Book of the Week and Book of the Year. His second, less successful, novel, The Living and the Dead, was published in 1941 and featured a writer who lived on Ebury Street ().

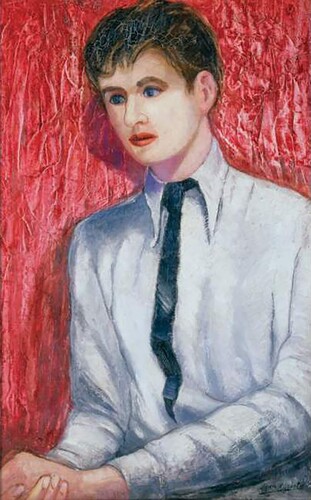

Figure 4. Roy de Maistre, Portrait of Patrick White, 1939, oil on canvas, 76.4 × 50.7 cm. Gift of the sitter’s niece, Miss Francis Peck, 1972. Reproduced by permission of Estate of Roy de Maistre and Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney.

We had previously left William Dobell in the Netherlands in 1930 briefly enjoying the comforts of Rient van Santen in Den Haag. Back in London and short of money, he thought of becoming an actor, and in 1934 he rented his good looks out to Alfred Hitchcock, who used him as an extra on his first version of The Man Who Knew Too Much. In 1936 he sketched Donald Friend (whose abuse of boys when he lived in Bali in 1967–1979 has now become infamous) reading on a bed for a work that is now in the National Gallery of Australia and entitled Portrait of Donald Friend (Sleeping Burglar) (1936). That was the year Friend had arrived in England, undoubtedly encouraged by his friend, the soon-to-be-world-famous ballet dancer Robert Helpmann, whom he had known back in Sydney, and who had left for England in 1932 (ballet is another of the connections between our artists).

Helpmann—he had added the extra “n” to his surname in the mid-1930s to lend it a “more exotic, European appeal”Footnote32—was soon employed as a member of the corps de ballet in the Vic-Wells Ballet Company, the forerunner of the Royal Ballet, by its founder, the former Ballet Russes dancer Dame Ninette de Valois. He would eventually go on to become the star of the Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger high-camp masterpieces (frequently given their look by the German Australian set designer Hein Heckroth) The Red Shoes (1948) and The Tales of Hoffmann (1951).

Once established in England, Friend exhibited at the Redfern Gallery in 1937, enrolled at the Westminster School that same year—studying, as many Australians did, with Mark Gertler and Bernard Meninsky—and had his work included in the exhibition Figure Drawings by English Artists of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries at R. E. A. Wilson’s gallery. Friend even managed to father a child by the mistress of Wilson, a man he described as “dangerous—more so than anyone I have known; for as far as I can see, his mind, his motives, actions and morals have absolutely no boundaries”.Footnote33 All the while, according to his diaries, he was a habitué of various bars and nightclubs in queer Soho, including the Shim Sham Club and, as he writes, a “very low homosexual nightclub called Pansy Jack’s Sailors Dance Bar: more Greek than the Greeks, my dear!”Footnote34

Dobell, for his part, later told the story behind Portrait of Donald Friend (Sleeping Burglar). He says that he shared his room at the time with a burglar nicknamed “Stiffy”, with Dobell supposedly having the bed at night and Stiffy during the day. But, as Dobell’s biographer Scott Bevan asks, “Was there ever a real thief sleeping in Dobell’s bed or was Bill’s story just a cover for some other arrangement?”Footnote35 Dobell’s sketchbook at the time also features other “sleeping” subjects, mainly young men stretched out on a bed or across a lounge. One drawing, which Dobell titled “Wouldn’tchou”, has a young man looking coyly at the observer. Also in 1936 Dobell painted The Dead Landlord, the story behind which he told to White a decade later, suggesting that it might “contain the theme for a play”.Footnote36 At the world premiere of White’s play The Ham Funeral in Adelaide in 1961, the poster and other promotional material featured an image of Dobell’s painting. And, as if to confirm the closeness of the relationship between Australia’s greatest writer and its best-known painter at mid-century, “Patrick White, in company, was once accused by his partner Manoly Lascaris of being unfaithful—with Bill Dobell. But White harrumphed and said it didn’t matter, because ‘Bill was no good at it’.”Footnote37

Finally, in 1936, Dobell painted The Irish Youth, a subject he repeatedly turned to, whose genesis his biographer explains this way: “Apparently the young man was unemployed and Dobell came across him killing time along the Thames.”Footnote38 This is, we suggest, one among many instances of sexual erasure in the biographies of our subjects, which invariably seek to underplay or even render invisible their queerness: we would note that Christopher Heathcote in Discovering Dobell makes not a single reference to Dobell’s queer London in the 1930s; Deborah Edwards makes no reference to Godfrey Miller’s sexuality in her 1997 retrospective exhibition catalogue; and even Heather Johnson, who does acknowledge de Maistre’s homosexuality, does not identify the sexuality of his friends and acquaintances, much less attempt any kind of queer reading of his work (his Crucifixions are always Catholic and never homoerotic, for example). We might suggest instead that Dobell met the subject of his painting while cruising the Thames, for the riverside was well known at the time as a beat. As Friend writes: “He [Dobell] liked sordid situations in which he found founts of sentiment. Bill was, in the proper sense of the word, vulgar; his strength lay in that vulgarity, the common touch, cocking a snoot at pretension, yet very sensitive to a feeling of social inferiority.”Footnote39

It is perhaps at this point that we should mention another queer Australian artist, Ian Fairweather, whose work was shown in London, though he was not living in Britain at the time. Fairweather had studied at the Slade in the 1920s and exhibited for the first time at the Redfern Gallery in 1927. In 1935, through his friendship with its curator, Jim Ede, the Tate Gallery acquired his Bathing Scene, Bali (1933), and in 1937 he held his second exhibition at the Redfern Gallery, where he exhibited numerous paintings from his travels through South East Asia, including Sampans at the Water Gate, Huchow (1936). In 1940, his Two Philippine Children (1935) was included in British Painting since Whistler at the National Gallery in London, and he held his third exhibition, Ian Fairweather: Paintings of China and the Philippines, at the Redfern in 1942 while he was serving in the British Army in India. He exhibited for the last time at the Redfern in 1948, having returned to Australia more or less permanently in 1943, where he became a famed artist recluse (although he appeared in Robertson’s show), and we wonder to what extent his restlessness and isolation can be attributed to his repressed queer identity.

Back in London, in early 1938, de Maistre moved residence around the corner from his former home to 13 Eccleston Street, Belgravia, where he would live for the rest of his life. He occupied the long room at the back of the building, once a restaurant, on the ground floor, which doubled as his studio. He then offered Patrick White the top floor. Accepting his offer, White then commissioned furniture and, as his biographer David Marr writes, “Bacon designed him a magnificent writing desk with wide, shallow drawers and a red linoleum top, and from de Maistre’s friends, [Sydney and Rab] Butler, White brought a glass and steel table and a set of stools all designed by Bacon.”Footnote40 In his autobiography, White recalls: “I had got to know Francis when he designed some furniture for my Eccleston St flat. I like to remember his beautiful, pansy-shaped face, sometimes with too much lipstick on it.”Footnote41 On the walls of the apartment, White hung his expanding collection of de Maistres, and downstairs he met Douglas Cooper, who himself had commissioned a Bacon desk, though he said he kept it “to show guests how bad he thought it looked”.Footnote42 This was typical Cooper, of whom White observed that he “would start off genial and generous, then turn against those he had taken up”.Footnote43 And White, of course, wrote these words undoubtedly aware of the falling out between Cooper and de Maistre that took place in 1938 around the time Cooper inscribed a copy of the book Vincent van Gogh: Letters to Emile Bernard that he gave de Maistre at Christmas: “Tu m’as donné ta boue et j’en ai faix de l’or” or “You gave me your mud and I made it gold”. This may, however, have been something of a shared joke between them because, as Johnson notes, it is “unlikely de Maistre would have kept the book had he felt grossly insulted”.Footnote44

In 1939 White headed across the Atlantic in search of an American publisher. Undertaking a transcontinental road trip, he decided to make a pilgrimage to Taos, New Mexico, in honour of D. H. Lawrence. By then an already well-established art colony, Taos was where Fred Leist and Francis McComas had worked in the 1920s, just as Frank and Margel Hinder had in the mid-1930s. White met there the ex-Bloomsbury painter Dorothy Brett, who took him to meet Lawrence’s widow, Frieda. Encouraged to come by the grand dame of Taos, Mabel Dodge Luhan, Lawrence revised his “Australian” novel, Kangaroo, there two months after leaving Australia in 1922. While in Taos, White also met the man who would later be called “the aesthetic and intellectual conscience of Taos”, Walter Willard “Spud” Johnson, and the two became lovers.Footnote45 Indeed, the town would inspire White’s The Aunt’s Story (1948), whose last chapter features—in an echo of the last chapter of Joyce’s Ulysses—an extended monologue by his main character, the “aunt” of the title, who mystically fuses with the desert. Not coincidentally, the cover of the first edition is adorned with de Maistre’s Figure in a Garden (The Aunt) of 1945.

There are two more queer men, a couple in fact, to introduce to this account. Arriving in London in 1939, just five months before war was declared, the Geelong-born writer, editor and publisher of the “little magazine” Manuscripts, Harry Tatlock Miller, and his life partner, the artist and scenographer Loudon Sainthill, had travelled together with the Ballet Russes, which was returning to Europe from its second successful tour of Australia. In London, the pair bed-hopped between the flats and studios of friends and acquaintances. One of these contacts was Chica Edgeworth Lowe, the future chatelaine of the art colony at the Merioola mansion, where the couple resided upon their return to Sydney, and another was Canadian dress designer and ballet costumier Matilda Etches (). It was she who held the open house at which Robert Helpmann met his life partner, the stage director at the Old Vic, Michael Benthall. In July, Sainthill exhibited his paintings, all gouaches, at the Redfern Gallery, enabled by another queer man, the Melbourne writer, gallerist and curator Basil Burdett. Burdett left England the day after Sainthill’s opening, having previously been in Paris putting together the landmark Exhibition of French and British Modern Art, which would open in Australia before the end of the year. Sainthill’s show was mostly portraits of the Covent Garden Russian Ballet Company, painted on board the boat as it steamed to England, and some 50 of the 55 works were sold. The famous photographer Cecil Beaton, who described himself as “a terrible, terrible homosexualist” but from his diaries was clearly bisexual, also commissioned a work.Footnote46 Beaton was certainly a great friend of the royal family and the then Duchess of Kent visited the exhibition less than a week after it opened. However, following the declaration of war, Sainthill and Miller return to Sydney, again with most of the dancers of the Ballet Russes heading for their third tour of Australia.

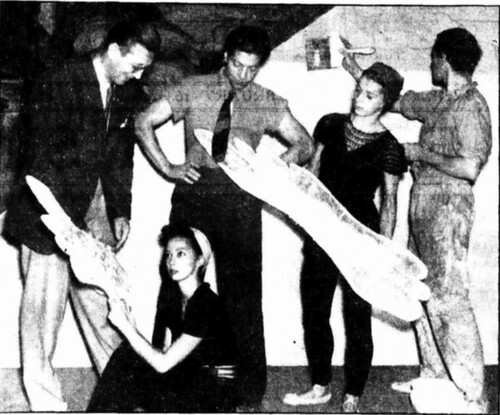

To continue with the theme of ballet, just two days after Sainthill and Miller arrived in Sydney on Boxing Day 1939 by boat, the famous Ukrainian French dancer and choreographer Serge Lifar arrived by plane. A few days later, he sees Sidney Nolan’s The Eternals Closed the Tent (1939) at the flat of the newly installed editor of Art in Australia Peter Bellew, through whom he contacts Nolan and approaches him to design and paint the backdrop for Icare, his upcoming ballet at the Theatre Royal. Nolan quickly took the train to Sydney, where his first design was rejected but his second accepted. Nevertheless, all did not go smoothly. The artist Frank Hinder was brought in to help Nolan realise his design, but one day turned up to work to find Nolan missing. Nolan was eventually found at Central Station, panicked and running from the job, waiting to catch the train back to Melbourne; but Hinder talked him into returning, the job was finished, and Icare opened in February 1940, with Lifar in the lead role (). Following the first night’s performance, there were reportedly 25 curtain calls, and Nolan joined Lifar, the conductor and the producer on stage to bathe in the audience’s applause.Footnote47 Not unsurprisingly, Nolan told a journalist at the time, “It is the biggest thing that has ever happened to me.” In March, as the war moved quickly in Europe, Lifar departed Australia, this time by flying boat, returning to France via Bali. Then in June Paris fell to the Nazis, but no sooner had the Wehrmacht installed itself than Lifar made it known to them that he was available for collaboration, pushing himself forward to head the Opera Garnier. Incredibly, three months later, he improvised a dance at the German embassy in Paris to celebrate the German Army’s victory over the French. In the words of Frederic Spotts, the author of The Shameful Peace: How French Artists and Intellectuals Survived the Nazi Occupation, Lifar was “a liar’s liar, a name-dropper’s name-dropper, and opportunist’s opportunist”. More than once, “while stroking the arm of some nearby man who caught his fancy”, Lifar is said to have uttered the words: “Only two men have caressed me like this, Diaghilev and Hitler.”Footnote48

Figure 6. L-R Col de Basil, Genevieve Moulin, Serge Lifar, Sona Asato and Sidney Nolan. The Sun, 16 February 1940, p. 2.

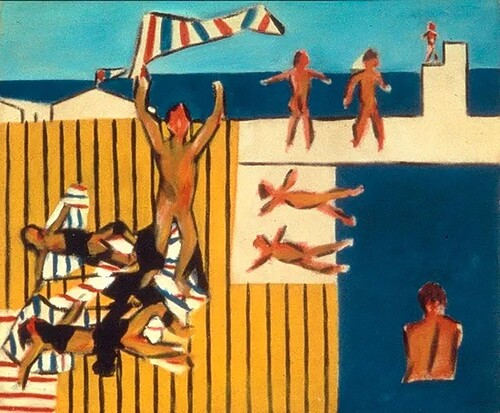

For his part, Nolan, before he deserted the army for whom he performed the no-doubt demanding labour of loading and unloading trains, was working on his paintings of bathers at St Kilda (). He completed the first of these in 1939, developed further versions in 1942 and 1945, and took up working on them again in 1975 and into the mid-1980s. Most often featuring a tripartite figure group, the series depicted naked men lying next to each other at the men-only baths in Port Phillip Bay near Luna Park in Melbourne.Footnote49 The didactic panel for Nolan’s Bathers (1942) in the 2022 exhibition Queer: Stories from the NGV Collection explained that the baths were a “well-known meeting place for queer men around this time” and that Nolan “referred to himself as ambi-dextrous—his word for bi-sexual”. Indeed, it has been suggested that in 1947 Nolan had an affair with the poet Barrett Reid during a trip to Brisbane. Certainly, he painted Reid twice, in two of the relatively few portraits he devoted to a contemporary subject. Later, Nolan wrote to John Reed that, “in general terms, Brisbane seems to have a strong homosexual overtone”.Footnote50 We note that he did not report to his one-time lover that it was an undertone.

Figure 7. Sidney Nolan, Bathers, 1942, enamel paint on cardboard, 64.0 × 76.2 cm. Gift of Sir Sidney and Lady Nolan, 1983. Reproduced by permission of the Sidney Nolan Trust DACS/Copyright Agency.

Shuttling between England and Australia after the war was Patrick White, who had been demobbed in early 1946 after serving mostly in North Africa and the Middle East. He returned to Australia that year, where he caught up with Dobell, who was painting above a bank in Darlinghurst. A year later he headed back to Europe, coincidentally aboard the same ship as the Sydney artists Mary Webb and James Gleeson, who were both soon to meet up again at the leafy artists’ colony just outside of London known as the Abbey. Only in London for a year, during this time Gleeson produced his somewhat camp and very surrealist Agony in the Garden (1948). White disembarked at Port Said, Egypt, to spend time with Manoly Lascaris, his eventual life partner, the pair having met in Alexandria during the war, before heading on to London to tidy up his affairs. In early 1948 he arrived back in Sydney, having sold his Bacon furniture but with his collection of de Maistres intact. In fact, some five years later he commissioned a carpenter in Parramatta to make a copy of Bacon’s desk and hung one of de Maistre’s Descents from the Cross above it, under which he proceeded to write The Tree of Man (1955). Later he hung Fairweather’s Gethsemane (1958) above it and the desks themselves became the subject of a work by the English artist Simon Starling.

In 1949, after having spent some seven years at Merioola in Sydney with Donald Friend, among others, Loudon Sainthill and Harry Tatlock Miller returned together to London. Once there, Miller was employed by Rex Nan Kivell as an assistant at the Redfern Gallery, rising eventually to become its director (). Vaughan exhibited at the Redfern in 1950 (Passmore is likely to have been at the opening not long before his return to Sydney) and then again in 1952 with his first survey, Keith Vaughan: Retrospective Exhibition. Not long after Sainthill’s arrival, Helpmann commissioned him to design the ballet Ile des Sirènes, which he and Margot Fonteyn would take on tour. This led to Sainthill’s first major commission, for Michael Benthall’s production of The Tempest at Stratford-upon-Avon, and from this time on Sainthill designed, on average, about four productions a year—opera, dance, drama and musicals—for such directors as John Gielgud, Laurence Olivier and Noel Coward. In 1951, Miller edited and Sainthill “decorated” the very celebratory Royal Album for that year’s Festival of Britain, which they followed up in 1958, in the wake of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, with Undoubtedly Queen (in full awareness of the pun), which was in fact about Queen Elizabeth I. Nineteen fifty-one was also the year Nolan held his first English show, at the Redfern Gallery, and, encouraged by this, some two years later he moved permanently to Britain. In 1955 he held another exhibition at the Redfern, this time of his second series of Kelly paintings, of which Zander noted that “the bush ranger is monstrous in the Baconian manner”.Footnote51 Two years later, Nolan designed the cover for White’s Voss—they would not, in fact, meet in person until 1958 in, of all places, Fort Lauderdale, Florida—and in June that year Robertson curated Sidney Nolan: Paintings from 1947 to 1957 at the Whitechapel Gallery, the beginning of Nolan’s English canonisation and the English “myth of isolation” that would soon surround Australian art.

Figure 8. Rex Nan Kivell with his business partner, Harry Tatlock Miller, in the Redfern Gallery, 1957. Photographer unknown. Reproduced courtesy of National Library of Australia, Canberra (manuscript collection MS4000).

Just a few years later, Robertson, who, as we have noted, was queer, oversaw Roy de Maistre: A Retrospective Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings 1917–1960 at the Whitechapel, and in 1962 he organised Vaughan’s first institutional retrospective at the same gallery, the catalogue for which included the autobiographical “Extracts from a Journal 1943–1961”, which makes clear Vaughan’s homosexuality. That same year, Nolan produced the scenography for a revival at Covent Garden of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, first staged, of course, by Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes in Paris in 1913. According to Sainthill’s biographer Andrew Montana, Nolan’s art “inverted a folkloric Russian past to present a nightmarish vision of Aboriginal Australia”, and, despite his “appropriating the rituals and ceremonial arts of Indigenous tribal cultures … it was heralded as a triumph of choreography, musical and visual interconnectedness”.Footnote52 This “exoticism” was seen to characterise Australia and Australian art, a perception that Australian artists sometimes exploited. And that same year, too, de Maistre, Dobell, Friend, Miller, Nolan, Passmore and Gleeson, as well as Justin O’Brien and Jeffrey Smart, were included in that other pillar of England’s Australia of the 1960s, Australian Painting—Colonial, Impressionism, Contemporary, at the Tate.

In conclusion, we might mention two further events, both in their way reflective of the period. One is coolly judgemental and self-critical, the other utterly narcissistic and lacking in self-awareness. In 1963 White returned to London, chiefly to see Roy de Maistre again. He found his former lover “pursuing an elderly existence in Eccleston St. He was seventy. Little had changed in his studio”.Footnote53 Bacon’s yellow sofa was still in evidence, and de Maistre wore “ochre makeup carefully applied to his face, but it stopped at his ears, leaving the back of his neck a ghastly white”.Footnote54 De Maistre offered to leave White his studio in his will, but White declined. Before leaving London, White visited the career-defining Bacon exhibition at Marlborough Gallery. In 1967 he began to write The Vivisector, his novel about “a painter, the one I was not destined to become”, having received a valedictory letter from de Maistre, who would die the following year.Footnote55 The book was published in 1970. Sidney Nolan annotated his copy with all the purported convergences with his own life and career in the margins, although, as White made clear to his biographer, “John Passmore and Godfrey Miller are the principal sources for Hurtle Duffield’s life”,Footnote56 and his “paintings are more than anyone’s the paintings of Francis Bacon” ().Footnote57

Figure 9. Axel Poignant, photograph of Patrick White and Sidney Nolan, 1963, gelatin silver, 21.0 × 19.2 cm. Reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Australia, Canberra (Bib. ID 1650353).

Finally, in 1981 Sir Sidney Nolan, a recipient of the Order of Merit and member of the Royal Academy, created his late Icare in ink and oil on paper, on which he inscribed “Icare, Serge Lifar from Sidney Nolan”. When it was sold at auction, it was accompanied by a photo of the artist and Lifar holding the work at the Sydney Opera House that same year. It was perhaps an appropriate classical myth about overweening hubris that brought the two together: the one who had sought to ingratiate himself by dancing for Nazi generals in their offices in newly occupied Paris; the other who, during the same war, had deserted the army but later had himself filmed in the crowd respectfully watching an Anzac Day march. They had more in common than aspects of their sexuality, but both are part of an expanded Australian art history, which also does not float alone and untethered up in the sky but belongs down here on earth with others as part of a new horizontal art history.

* * *

What we have been trying to suggest is that a re-examination of the 1961 exhibition Recent Australian Painting opens up the possibility of another “Australian” art history. Certainly, as we have made clear, the queerness of many of the artists has not been discussed, at least not until recently. But what has not at all been recognised is the extent of the connections that arose between them because of their sexuality. It meant that they were not “foreign” and “exotic” but known to and intimate with both English art and each other. And it is this that Robertson himself represses in his exhibition: the fact that he came to understand and identify with the work of so many of the artists in the show because, like him, they were queer. In this sense, we would suggest that what, at least in part, is at stake in Recent Australian Painting is the art not of a “nation” but of a “scene”, just as there might equally one day be an exhibition looking at the queer women Australian artists who lived and worked in Paris between 1910 and 1950. Indeed, we might even say that the usual provincial history of Australian art is a heterosexual history, or at least one that would deny the connections Australian artists have always made with others because of their sexuality. But this story of the queer Australian men in London in the mid-20th century is typical of all the other “scenes” Australian artists have found themselves part of around the world, whether it be through friendships, marriages, exhibitions, art schools or art colonies. Australian artists have always had things in common with other artists, even when their respective nationalities apparently separated them. The queer male artists in London between 1930 and 1960 were “UnAustralian”, perhaps, but so were nearly all of those Australian artists in whose work we can now recognise ourselves. Or, as Christopher Isherwood once wrote in his novel Goodbye to Berlin about a homosexual Englishman in Germany in the early 1930s:

The little American simply couldn’t believe it. “Men dressed as women? As women, hey? Do you mean they’re queer?”

“Eventually we’re all queer,” drawled Fritz solemnly.Footnote58

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Bryan Robertson, “Notes on Australian Painting,” London Magazine 1, no. 3 (1961): 59–66, quoted in Simon Pierse, “Bryan Robertson, Abstract Expressionism and Late Modernism in Recent Australian Painting (1961),” in Impact of the Modern: Vernacular Modernities in Australia 1870s–1960s, ed. Robert Dixon and Veronica Kelly (Sydney: University of Sydney Press, 2008), 154–67.

2 Bryan Robertson, “Preface,” Recent Australian Painting (London: Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1961), 9–10.

3 Robert Hughes, “Introduction,” Recent Australian Painting, 13.

4 Barbara Blackman, Glass After Glass: Autobiographical Reflections (Ringwood: Viking Press, 1997), 13.

5 For scholarship on queer Australian women artists, see Janine Burke, Australian Women Artists: 1840–1940 (Collingwood: Greenhouse Publications, 1980), 37–61; Lucy Chesser, Parting with My Sex: Cross-Dressing, Inversion and Sexuality in Australian Cultural Life (Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2008); Peter Di Sciascio, “Australian Lesbian Artists of the Early 20th Century,” in In Out: Gay and Lesbian Perspectives VI, ed. Yorick Smaal and Graham Willett (Clayton: Monash University Press, 2011), 135–55; Helen Topliss, Modernism and Feminism: Australian Women Artists, 1900–1940 (Roseville East: Craftsman House, 1986), 25. For a number of brief essays on Grace Crowley, Anne Dangar, Mary Cockburn Mercer, Margaret Preston, Thea Proctor and Gladys Reynell, see Queer: Stories from the NGV Collection, ed. Ted Gott, Angela Hesson, Myles Russell-Cook, Pip Wallis, and Meg Slater (Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2022).

6 Patrick White, Flaws in the Glass: A Self-Portrait (London: Jonathan Cape, London, 1981), 57.

7 Brian Adams, Portrait of an Artist: A Biography of William Dobell (Melbourne: Hutchinson Press 1983), 59.

8 Ann Wookey, The Life and Work of Godfrey Clive Miller, 1893–1964 (PhD diss., La Trobe University, 1994), http://www.artresearchaustralia-online.info/Godfrey_Clive_Miller,_1893-1964/title_page.html.

9 Ann Wookey, “Miller, Godfrey Clive (1893–1964),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/miller-godfrey-clive-11123.

10 Francis Bacon, quoted in Heather Johnson, Roy de Maistre: The English Years 1930–1968 (Roseville East: Craftsman House, 1993), 21.

11 Johnson, Roy de Maistre, 21.

12 Martin Harrison and Rebecca Daniels, “Australian Connections,” in Francis Bacon: Five Decades, ed. Anthony Bond (Sydney: Art Gallery of NSW, 2013), 34.

13 Daniel Farson, The Gilded Gutter Life of Francis Bacon (London: Century Random House, 1993), 26.

14 Andrew Montana, Fantasy Modern: Loudon Sainthill’s Theatre of Art and Life (Sydney: NewSouth Publishing, 2013), 454. Montana quotes here an unidentified source.

15 John R. Thompson, “Nan Kivell, Sir Rex de Charembac (1898–1977),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/nan-kivell-sir-rex-de-charembac-11219.

16 John Richardson, “Remembering Douglas Cooper,” New York Review of Books, 25 April 1985, https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1985/04/25/remembering-douglas-cooper/.

17 Barry Pearce, “Introduction,” John Passmore (Sydney: Art Gallery of NSW, 1985), 8.

18 Pearce, John Passmore, 9.

19 David Thomas, “Catalogue Text,” Deutscher and Hackett, 30 April 2014, https://www.deutscherandhackett.com/auction/35-important-australian-international-fine-art-auction/lot/boy-bathing-1939.

20 Pearce, John Passmore, 11.

21 Beyond the Horizon—A Collection of Paintings from Artists Who Worked at the Lintas Advertising Agency 1930–1950 (London: Thomas Agnew and Sons, 1988).

22 Pearce, John Passmore, 11.

23 Philip Vann and Gerard Hastings, Keith Vaughan (Surrey: Lund and Humphries, 2012), 40.

24 Vann and Hastings, Keith Vaughan, 40.

25 Pearce, John Passmore, 11.

26 John Richardson, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice: Picasso, Provence and Douglas Cooper (London: Jonathan Cape, 1999), 11.

27 Charles Dellheim, Belonging and Betrayal: How Jews Made the Art World Modern (Waltham: Brandeis University Press, 2021), 447.

28 Johnson, Roy de Maistre, 28.

29 White, Flaws in the Glass, 59.

30 White, Flaws in the Glass, 60.

31 White, Flaws in the Glass, 62.

32 Christopher Sexton, “Helpmann, Sir Robert Murray (1909–1986),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/helpmann-sir-robert-murray-12620.

33 Friend, letter to his sister Gwendolyn, undated [1939], quoted in Anne Gray, “Introduction,” The Diaries of Donald Friend, Volume 1, ed. Anne Gray (Canberra: National Library of Australia, 2001), xvii.

34 Donald Friend, The Diaries of Donald Friend: Chronicles and Confessions of an Australian Artist (Melbourne: Text Publishing 2010), 58.

35 Scott Bevan, Bill: The Life of William Dobell (Cammeray: Simon and Schuster, 2014), 73.

36 Bevan, Bill, 75.

37 Martin Edmond, “The Man Who Knew Too Much: Bill: The Life of William Dobell,” Sydney Review of Books, 8 May 2015, https://sydneyreviewofbooks.com/review/the-man-who-knew-too-much/.

38 Bevan, Bill, 78.

39 Bevan, Bill, 446.

40 David Marr, Patrick White: A Life (North Sydney: Random House, 1991), 169.

41 White, Flaws in the Glass, 62.

42 Harrison and Daniels, “Australian Connections,” 36.

43 White, Flaws in Glass, 62.

44 Johnson, Roy de Maistre, 75.

45 Claire Morrill, quoted in Sharyn Udall, Spud Johnson and Laughing Horse (Santa Fe: Sunstone Press, 2008), 3.

46 Cecil Beaton from his diary in 1923, quoted in Hugo Vickers, Cecil Beaton: A Biography (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1986), 40.

47 Nolan, quoted in “Struggling Melbourne Artist Gets Big Chance with Ballet,” Herald (Melbourne), 13 February 1940, 3.

48 Frederic Spotts, The Shameful Peace: How French Artists and Intellectuals Survived the Nazi Occupation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 207–8.

49 Unattributed didactic panel for Sidney Nolan’s Bathers (1942), Queer: Stories from the National Gallery of Victoria Collection (exhibition), National Gallery of Victoria, 10 March–21 August 2022.

50 Sidney Nolan to John Reed, 26 February 1948, Reed Papers, State Library of Victoria, quoted in Nancy Underhill, Sidney Nolan: A Life (Sydney: NewSouth Publishing, 2015), 184. On Nolan’s speaking of himself as “ambidextrous” and his relationship with Barrett Reid, see Lesley Harding and Kendrah Morgan, Modern Love: The Lives of John and Sunday Reid (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2015): “It transpired that Nolan had told Barrie [Barrett Reid] on more than one occasion after he came to Brisbane [in July 1947] that he was ‘ambidextrous’, and although Bernie stopped short of giving John [Reed] a full confession—perhaps that would be too upsetting for the Reeds—he strongly alluded to the idea that he and Nolan has been sexually involved” (204).

51 Alleyne Clarice Zander, “Sidney Nolan,” Studio, September 1955, 86, quoted in Martin Harrison and Rebecca Daniels, “Australian Connections,” 38.

52 Montana, Fantasy Modern, 516.

53 Marr, Patrick White, 423.

54 Marr, Patrick White, 423.

55 White, Flaws in Glass, 150.

56 Marr, Patrick White, 473.

57 Marr, Patrick White, 474.

58 Christopher Isherwood, “Goodbye to Berlin,” in The Berlin Stories (New York: New Directions, 1963), 193.