ABSTRACT

The growth of online gambling necessitates that both marketers and regulators have a better understanding of the gambling intention of players. Perceived fairness of customers towards operators has often been raised as a concern in the industry, but it has received limited attention in research on gambling intention. Theories that seek to explain purchase intention are considered and a model is proposed that investigates the role and impact that perceived fairness and system effort expectancy have on online gambling intention together with the moderating influence of user experience. Data from 255 online gambling customers are gathered and analysed using Hayes PROCESS analyses. Results indicate that perceived fairness impacts gambling intention directly, and indirectly strengthening the effect of effort expectancy on gambling intention. However, user experience weakens both these impacts. The research provides support for the inclusion of perceived fairness in theories that consider drivers of online gambling intention. In addition, the important role that perceived fairness plays offers support for gambling regulators who in recent years have sought to promote a fairer and more transparent deal to players. Firms in the online gambling industry can also look positively at activities enhancing fairness as its promotion can also enhance their performance.

1. Introduction

The Internet gambling industry is a fast-growing, multibillion-Euro business where Europe stands out as the biggest market for online gambling, with a 48% market share (European Gaming & Betting Association, Citation2016). Thousands of online casinos are available via a number of jurisdictions (Casino City, Citation2017). Increased Internet access and the growth in smartphone adoption has meant that online gambling websites are accessible to almost everyone, everywhere and at any time of the day (eMarketer, Citation2016). The growing market has witnessed increasingly aggressive marketing activities among Internet gambling firms as they compete for players and market share. The offered games are often not very different, and the expected effort required to master a firm’s online gambling system is critical to the resultant experience that a player derives, and therefore to competition.

Despite its continued popularity, Internet gambling is a pastime with a questionable reputation (Binde, Citation2005a, Citation2005b). Issues concerning health and addiction have traditionally been highlighted in the literature that has tended to focus on problem gambling (e.g. Gainsbury, Suhonen, & Saastamoinen, Citation2014). This research focuses on recreational gamblers who see gambling as a leisure-time pursuit. The National Addiction Service of Singapore (Citation2013) provided a useful basis for understanding the difference between recreational or social gambling, and problem gambling. It holds that the former refers to those who gamble for fun, are able to remain within their means and can stop anytime. On the other hand, problem gamblers continue to invest time and money on gambling despite experiencing harmful, negative consequences. This distinction is also reflected in the literature, with the National Research Council (US) Committee on the Social and Economic Impact of Pathological Gambling (Citation1999) holding that recreational gamblers are those who gamble for entertainment and typically do not risk more than they can afford (Custer & Milt, Citation1985; Shaffer, Hall, & Vander Bilt, Citation1999). Following the latest update to The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013) the terminology used for pathological or compulsive gambling is now gambling disorder. DSM-5 (p. 586) notes that ‘The essential feature of gambling disorder is persistent and recurrent maladaptive gambling behavior that disrupts personal, family, and/or vocational pursuits’ with one of its characteristic criterion (A6) being the frequent, and often long-term, pattern of ‘chasing one’s losses’.

Trust and issues of fairness of the products, games and services offered are increasingly a concern for both recreational gamblers and regulators (Cook, Citation2017; UKGC, Citation2017b, Citation2017c; Wood & Williams, Citation2009; Yani-de-Soriano, Javed, & Yousafzai, Citation2012). In a business where random number generators, or slot machines, dominate, players should rest assured that they are treated fairly and in a transparent manner. Thus, lawmakers, regulators and licensing bodies look at fairness and transparency as important features. For instance, in 2016, the United Kingdom Gambling Commission (UKGC) and the Competitions and Markets Authority (CMA) announced an investigation into the fairness of the terms and conditions offered by online betting firms (Rodionova, Citation2016). In May 2017, the UKGC fined a gambling operator for misleading advertising for the first time, arguing that it was not fair on the customer (UKGC, Citation2017a), and in June of the same year, the CMA issued a press release highlighting their concern with the fairness of promotions offered to Internet gambling customers (CMA, Citation2017).

Despite its importance, perceived fairness of customers towards operators has received little attention in the academic literature on online gambling. To better understand its role, we consider theories that seek to understand purchase intention and investigate the role and impact of perceived fairness and effort expectancy on online gambling intention. We also examine whether user experience weakens these interactions. Data are collected from 255 customers of an Internet gambling firm and analysed using Hayes PROCESS macro for IBM SPSS version 21 (Hayes, Citation2013). Results are reported, implications discussed, and limitations and further research areas are indicated.

2. Literature review

2.1. Purchase intention

Several models have been developed that seek to understand purchase intention of which the Theory of Reasoned Action – TRA (Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1980; Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975), the Theory of Planned Behaviour – TpB (Ajzen, Citation1985) and the Technology Acceptance Model – TAM (Davis, Citation1985) are among the best known. Over the years, extensions (e.g. TAM 2 by Venkatesh & Davis, Citation2000) and hybrids of these models (e.g. Combined TAM and TpB by Taylor & Todd, Citation1995) have been proposed. In an attempt to synthesize the salient models within the literature, Venkatesh, Morris, Davis, and Davis (Citation2003) developed the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), originally focusing on employees using internal IT systems. The authors identified four key drivers of behaviour intention: performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social norms, and facilitating conditions; and four moderating variables: gender, age, experience, and voluntariness of use. Venkatesh, Thong, and Xu (Citation2012) have also successfully employed the model to the purchase intentions of mobile Internet customers while Oh and Yoon (Citation2014) have used it in an e-learning and online gaming context.

2.2. Perceived fairness, effort expectancy and online gambling intention

In a study by Wood and Williams (Citation2009), commissioned by the Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre, it was reported that many Internet gambling players have concerns about online casinos paying out customers’ winnings and ensuring the fairness of the games. Gainsbury, Parke, and Suhonen (Citation2013, p. 243) reported ‘a substantial proportion [of customers] believing that there is an “on/off” switch that can be used to cheat customers’. The concern for fairness has also been reiterated by legislators and regulatory bodies, especially in the UK (CMA, Citation2017; Moore, Citation2017; Rodionova, Citation2016; UKGC, Citation2017a). However, despite its importance the theories explaining behavioural intention do not incorporate perceived fairness as a possible driver. A primary objective of this article is to investigate the role of perceived fairness on online slot machine gambling intention. The decision to focus on effort expectancy and user experience from the four drivers and four moderators identified in UTAUT stems from a desire to test a parsimonious model. Effort expectancy was chosen because this is reported as having the strongest impact on intention (Oh & Yoon, Citation2014) while experience as a moderator represents a pertinent variable in an online gambling context.

For the purpose of this study, perceived fairness is defined as ‘an individual’s perception about the output/input ratio, the procedure that produces the outcome and the quality of interpersonal treatment’ (Chiu, Lin, Sun, & Hsu, Citation2009, p. 349). This definition is operationalized as a three-dimensional construct, comprised of distributive, procedural and interactional fairness that are all relevant to an online gambling context. Distributive fairness refers to the degree to which customers’ expectations are being met; procedural fairness is about customers’ perceived ability to complain and speak to representatives; while interactional fairness focuses on how fairly and respectfully customer service representatives act and treat clients. A number of authors provide support for a link between fairness and behaviour intention (e.g. Namkung & Jang, Citation2009, Citation2010; Palmer, Beggs, & Keown-McMullan, Citation2000; Su & Hsu, Citation2013). In an online gambling context, we therefore hypothesize that:

H1: Higher perceived fairness leads to higher online gambling intention.

The effort expectancy construct in UTAUT, like its predecessor ‘ease-of-use’ in TAM, captures how much effort users expect to invest in order to be proficient in using a system. Lower effort expectancy has been shown to be a significant predictor of intention (e.g. Chan et al., Citation2010; Chiu & Wang, Citation2008; Lee, Lin, Ma, & Wu, Citation2017; J.-C. Oh & Yoon, Citation2014; S. Oh, Lehto, & Park, Citation2009; Venkatesh et al., Citation2003). Moreover, Oh and Yoon (Citation2014) show that in both the online gaming and e-learning context, effort expectancy has the strongest effect on intention. We therefore focus on the link between effort expectancy and intention in an online gambling context and hypothesize that:

H2: Lower effort expectancy leads to higher online gambling intention.

However, the theories and models seeking to explain the linkage to purchase intention are single-stage models that may not correspond to actual human processes. In order to better understand how perceived fairness impacts online gambling intention and how it interacts with effort expectancy, we propose an alternative mediated hypothesis:

H1alt: As users expect online gambling to require more effort, perceived fairness becomes a stronger driver of online gambling intention.

2.3. The role of user experience

User experience is defined as familiarity with a new technology over time (Venkatesh et al., Citation2003). Together with other demographics of age and gender it is treated as a moderator in UTAUT and found to weaken the relationships it moderates. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H3a: User experience weakens the impact of effort expectancy on gambling intention

However, given the inclusion of perceived fairness as an important additional antecedent construct to online gambling intention, we also investigate the moderating effect of user experience on the impact of perceived fairness on both effort expectancy and online gambling intention. Hence:

H3b: User experience weakens the impact of perceived fairness on online gambling intention.

H3c: User experience weakens the impact of perceived fairness on effort expectancy.

The hypotheses described above, and their resultant relationships are shown in the research model in .

3. Methodology

The research instrument used in this study was written in English and consisted of 21 items; 17 to capture the constructs under investigation and 4 items to capture demographics for user experience, age, gender and residence. User experience was collected by asking respondents to indicate the number of years they had been gambling online. Perceived fairness was measured using the three-dimensional construct adapted from Chiu et al. (Citation2009) consisting of 10 items, while the 4-item measure of effort expectancy as well as the 3-item measure for online gambling intention were adopted from Venkatesh et al. (Citation2003). The adaptations made to the items reflect the online gambling context. All measures have been used in previous studies and indicated acceptable psychometric properties (cf. Chan et al., Citation2010; Chiu et al., Citation2009; Chiu & Wang, Citation2008; Magsamen-Conrad, Upadhyaya, Joa, & Dowd, Citation2015; Tan, Citation2013; Venkatesh et al., Citation2003). All items were measured with a 7-point scale which ranged from 1 = ‘Strongly disagree’ to 7 = ‘Strongly agree’. In the case of effort expectancy, the wording is such that, the higher the value, the stronger it is expected that effort will be low. Thus, by way of example, a high score on the first effort expectancy question, reading ‘My interaction with an online gambling system needs to be clear and understandable’, means that a low level of effort is required. A pretest of the final research instrument was conducted among a sample of 30 online casino customers to determine and improve item comprehension and completion, as well as the data gathering process and response time.

Final data collection was undertaken via arrangements made with the Malta operation of the online gambling firm ALEA. The company was willing to allow the forwarding of the research instrument to a random sample of 2000 players taken from their database of customers who had registered but not made a deposit after 48 hours of registration with their brand SlotsMillion.com. To ensure that respondents were indeed active online gambling customers, a filtering question at the beginning of the questionnaire asked whether the respondent was currently actively playing and wagering on any online gambling website. Only respondents answering ‘Yes’ to this question were included in the data collection. Qualtrics was used for online data collection. To increase response rates, an incentive consisting of 20 free spins for the value of €0.10 per free spin on the well-known game Starburst from NetEnt was offered to respondents completing the questionnaire. To receive the gift, the respondent had to contact the customer service at SlotsMillion with a code that was provided to respondents on completion of the questionnaire.

Steps were also taken to ensure that ethical standards were maintained. First, the questions asked were such that no harm or discomfort would result. Second, informed consent was ensured via a cover letter that appeared when data collection took place, describing the academic nature and purpose of the research. Participation was completely voluntary, and respondents could discontinue completing the questionnaire at any point. They were also given the contact details of one of the researchers. Third, the privacy and anonymity of the respondents were safeguarded. Respondents visited a separate university website that hosted the Qualtrics questionnaire. The collected classificatory data did not ask questions of a private nature, nor was individual identification available to the researchers or to the supporting firm. All data analyses undertaken and shared was at an aggregated level.

Data analyses commence by providing descriptive statistics for the data collected. This is followed by principal component factor analysis and reliability testing which are employed to investigate the psychometric properties of the instruments used to capture the constructs of this study. Finally, the moderated-mediation hypotheses in the research model are tested via two concurrent regressions using Hayes (Citation2013) PROCESS analyses.

4. Results

A total of 15.2% of the 2000 customers sampled responded in the first 3 weeks of the survey. Of these, 49 could not be used primarily due to incomplete answers, so that a total of 255 completed and usable questionnaires were obtained. Respondents were aged 18 to 88 years old with a mean age of 34.91 (SD = 9.43); 50% were male; and reported experience with online gambling ranged from less than 1 year to 11 years with a mean of 3.18 years (SD = 2.41). In terms of residence, 50.9% were from Australia and New Zealand; 15.4% were from the Netherlands and 14.0% were from Germany. Because of confidentiality, it was not possible to test for non-response bias by comparing demographic characteristics of the sample with those of the online betting population of the supporting firm. However, methodological studies indicate that even relatively large variations in response rates do not have much effect on final sample estimates (Keeter, Kennedy, Dimock, Best, & Craighill, Citation2006). Descriptive statistics are shown in .

Table 1. a. Descriptive statistics for items and loadings from factor analysis followed by an oblimin rotation (n = 255).

Before proceeding to explore the data via principal components factor analysis in IBM SPSS v21, the KMO and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were computed. The results of the KMO test provided a value of .91, which is in the ‘marvellous’ category (Kaiser & Rice, Citation1974), while Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant at 2862.08 (p < .001). These results indicate the existence of sufficient correlations in the data collected thereby providing support for its investigation via exploratory factor analysis. To test for common method variance, the component matrix resulting from the factor analysis was observed. This indicated multiple factors, providing support for the absence of common method variance for the measures used (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Citation2003). The data was further investigated using an oblimin rotation, which was chosen because the three multi-item constructs in the study were expected to be correlated. The resultant four-factor solution accounts for 74.25% of the cumulative variance in the data and correspond to the three constructs used in this research. Online gambling intention and effort expectancy load on separate factors while perceived fairness loads on two factors corresponding to the distributive fairness dimension and the procedural and interactional fairness dimensions, with the latter two tending to load together. Resultant loadings are shown in the last four columns of and provide support for both convergent and discriminant validity of the measures employed. Reliability was investigated using Cronbach alpha (Cronbach, Citation1951), which provided scores of .89, .90, .88 and .89 for gambling intention, effort expectancy and the two dimensions of perceived fairness, respectively. Overall perceived fairness had a Cronbach alpha of .92. Taken together these results provide support for the psychometric properties of the instruments used, allowing them to be confidently employed in further analyses. When investigating causal effects, whose linkage hypotheses have been defined at the construct level, any analyses should be undertaken at a construct and not at a dimensional level (Wong, Law, & Huang, Citation2008). Therefore, the items making up the constructs were summed up and used as variables in moderated-mediated regression.

The proposed model was investigated using Hayes’ PROCESS Macro for IBM SPSS v21. The macro allows for analyses of complex models with mediation and moderation. PROCESS (Hayes, Citation2013) was used in the analyses in preference to variance or covariance based Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) for three reasons. First, although based on different estimation methods and theory, the results from the two alternative analytical techniques are largely identical and any differences are minimal and rarely substantive (Hayes, Montoya, & Rockwood, Citation2017). Second, the SEM approach is known to have some serious limitations when looking at mediation-moderation and PROCESS is to be preferred (MacKinnon, Coxe, & Baraldi, Citation2012). Finally, the investigated research model which consists of a single moderator and mediators whose interactions correspond to Model 59 in PROCESS makes for relative simplicity of analyses.

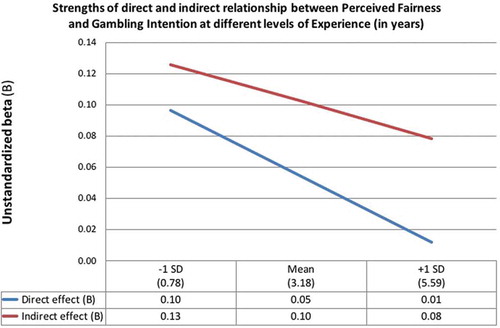

The results of the moderated-mediation multiple regression analyses are shown in and . These indicate that the effect of perceived fairness on gambling intention is partially mediated via effort expectancy and provide support for H2 and H1alt. The resultant B parameters show that the magnitude of the direct effect of perceived fairness on gambling intention is .11, but at .13 (.31 x .43) its indirect effect via effort expectancy is stronger.

Table 2. Results from moderated-mediated multiple regression analysis using Hayes’ (Citation2013) PROCESS Macro.

In addition, the model also investigates the weakening effect of user experience on the impact of perceived fairness on gambling intention. The results do not provide support for H3a, which holds that user experience weakens the impact of effort expectancy on gambling intention. This is counter-intuitive and may be occurring as a result of the constant changes that online betting firms undertake with the introduction of new and improved website design that require a constant degree of learning that in turn renders previous experience of limited use. Moreover, features such as metagaming or gamification of the website designed at increasing retention (Griffiths & Carran, Citation2015) may also require the customer to invest some effort into understanding how the (new) feature works. However, both H3b and H3c are supported so that user experience weakens the impact of perceived fairness on gambling intention and on effort expectancy. The direct and indirect effect of perceived fairness on online gambling intention at different levels of experience is shown in . The lower line represents the strength of the direct effect of perceived fairness on gambling intention, whereas the upper line represents the situation as a result of the mediated effect of effort expectancy. In both cases, players with higher experience give less importance to fairness and effort expectancy (ease of site negotiation) than less experienced or novice individuals.

5. Conclusions and discussion

Perceived fairness is of concern to both online gamblers and regulators but it has not received much attention in the literature. This research considers models from the literature that seek to explain purchase intention and applies them to an online gambling context to investigate the interaction of perceived fairness, effort expectancy, user experience and gambling intention. In doing so, it contributes to refining our understanding of these challenging constructs for the online gambling industry. Results indicate that the effect of perceived fairness on online gambling intention is made stronger by the mediating effect of effort expectancy. The resultant B parameters show that the magnitude of the direct effect of perceived fairness on gambling intention is .11, but at .13 (.31 x .43) its indirect effect via effort expectancy is stronger. Taking these two effects together suggests a slope of .24 so that for every unit increase in perceived fairness, there is a 24% increase in intention to gamble online. These results support gambling firms’ investments in enhancing perceived fairness and lowering effort expectancy.

Lowering effort expectancy requires that front-end systems be increasingly customer-driven and not remain solely the domain of technical developers. A look at the results in for the mean scores shows that the perceived fairness items obtain the lowest scores. To improve these requires effort directed at the activities captured by the dimensions of perceived fairness. Therefore, to improve the dimension of distributive fairness, it is not enough to enhance the perceived fairness of offerings but it is also necessary to convince players that their monetary transactions are being handled carefully and quickly (Gainsbury, Citation2012; Wood & Williams, Citation2009). The dimension of procedural fairness is about openness and transparency. These are known to be key customer concerns that are actively being pursued by regulators (UKGC, Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2017c) and need to be embraced by firms. In terms of interactional fairness, it can be said that firms are generally aware that good customer service is the backbone of increased patronage (e.g. Wood & Griffiths, Citation2008), and devoting resources to building excellent customer support in different languages is critical. Systems can be enhanced not only via technical improvements, but also by putting into place policies and activities that communicate a firm’s interest in providing a fair deal. It is clear that the pursuit of fairness represents a win-win situation for both regulators and online betting firms. The former increasingly insist on fairness while for the latter it can enhance betting intention among customers.

This study also looked at whether an increase in user experience weakens the impact of effort expectancy on purchase intention and whether it similarly weakens the impact of perceived fairness on gambling intention and effort expectancy. A weakening effect on the impact of effort expectancy on gambling intention, as suggested in the literature (Venkatesh et al., Citation2003), was not found. Other studies employing UTAUT have reported a similar finding (e.g. Oliveira, Faria, Thomas, & Popovič, Citation2014), suggesting that this weakening effect from user experience is likely to be context dependent. However, results show that user experience does weaken the impact of perceived fairness on both effort expectancy and gambling intention, suggesting that growing gambling experience weakens the importance of perceived fairness. The latter is likely due to the fact that experienced users have already convinced themselves that the system is a fair system, irrespective of whether, objectively, it is or is not. In such circumstances, it may well be that the transactional activities represented by the items in the measure of perceived fairness become less important. For example, having customer service representatives treat people with politeness may not be an issue for online users since customer service is rarely ever contacted. Moreover, as players become more knowledgeable about online gambling in general, they come to accept the rules of the game; know how to ‘move in the sphere of gambling’; and know what to expect and how to behave. Perceived fairness is more important to novice players, who still need to become acquainted with the online gambling market. These may therefore have higher expectations of fairness simply because the system is relatively unknown to them.

The results have implications for theory, policy and practice. The findings indicate that perceived fairness of customers towards operators is an overlooked construct in understanding final purchase intention in an online gambling context. The general theories that seek to explain purchase intention, including TRA, TpB, TAM, TAM2 and UTAUT, do not consider perceived fairness of customers towards operators as an important driver of purchase intention. The findings also support the current policy initiatives by regulators promoting greater fairness and transparency by confirming the importance that customers place on this, suggesting that polices which seek to strengthen fairness are likely to be well received by customers. Regulatory activities improving fairness should be viewed positively by the industry, as firms that are able to enhance perceived fairness among customers can benefit from higher gambling intention.

The Internet gambling market consists of a large number of firms that compete for market share and share of wallet, globally. New players are increasingly presented with a vast amount of choice and myriad promotional inducements. However, effective competition requires that firms seek clear positioning and differentiation. In a sector where real differences are limited, perceived fairness can potentially provide a distinctive positioning option for early movers. The results suggest that an Internet gambling firm wishing to position on ‘fairnesss’ should target young, novice players of both sexes who are in the early stages of the customer life cycle.

6. Limitations and future research

As is the case with any research design chosen, there are a number of limitations with this research that should be taken into consideration. First, the research utilized a cross-sectional survey and a convenience sample. This has a number of disadvantages that include the fact that it does not allow for the analyses of behaviour over a period of time; the timing of the survey may be such that the representativeness of the snapshot obtained cannot be guaranteed; and that it cannot determine cause and effect.

Second, the sample for this study was taken from the database of a single online casino (SlotsMillion.com), which, at the time, only offered online slot machines. The findings may therefore not reflect perceptions across other forms of online gambling such as online poker, sports betting and lotteries. Future research should therefore look at replication both for online slot machine gambling and beyond to other forms of online gambling.

Third, the questionnaire was sent to players who had registered but not made a deposit after 48 hours of registration. Although this is not an uncommon situation in online gambling, future studies could collect data from more active customers. It would have been useful to collect data about active customers in terms of respondents’ frequency of use of online betting services. However, asking for this data directly as part of the data collection process was deemed unlikely to result in accurate replies, and a better way to obtain such data, if the cooperation of a collaborating firm is forthcoming, is to link respondents with their online betting histories. But such an approach would mean foregoing anonymity of respondents which, given the nature of the online betting industry, is an important aspect of ethical behaviour by researchers. Notwithstanding, future research would do well to see if suitable arrangements with a supporting firm are possible, allowing researchers to gain access to respondents’ histories while safeguarding respondents’ confidentiality, if not anonymity.

Fourth, the analyses are based on 255 responses which represents a response rate of 15.2%. Generalization of findings to the population of interest presumes that the sample is a representative sample of that population and, generally, higher response rates are desirable, as low response rates may result in biased population parameters. It is known that response rates to email surveys have been decreasing (Sheehan, Citation2001) while the meta-analysis by Manfreda, Berzelak, Vehovar, Bosnjak, and Haas (Citation2008, p. 8) indicates that ‘web surveys yield a lower response rate of about 11% on average compared to other modes’. To increase the response rate this research has adopted clarity in the cover email sent which linked to a short, well-structured, web-based questionnaire while also providing anonymity and an incentive for those opting to respond. In itself, the latter may have created a bias in terms of disproportionally attracting respondents who are motivated by the incentive provided. Given the circumstances, it can be argued that the response rate is reasonable but the nature of the research and the response rate suggest that any generalizations undertaken need to be done with caution.

Fifth, both measures of effort expectancy and perceived fairness can do with a critical reappraisal. Although in both cases standard measures were adopted to ensure content validity, it can be noted that in the case of the perceived fairness measure there are a number of items that appear to be more in line with notions of service quality rather than fairness, while a number of items in the effort expectancy measure ask about how the system should be rather than how it actually is. Indeed, as it currently stands, only one item (PF4) asks whether the gaming product was ‘fair’. The other items focus on customer service delivery, the value proposition for the site, and fairness in communication. It may be that these aspects of fairness are not quite equivalent to fairness in the probability of outcomes (e.g. a fair ‘flop’ in poker, true randomness in cards drawn, and so forth). In addition, it may be that the importance of perceived fairness and what constitutes ‘fairness’ may vary across different online gambling products. Therefore, it may be useful to consider improving the perceived fairness measure by asking questions that are more specific to the perceived fairness of the particular gambling product.

Finally, this study has looked at perceived fairness in relative isolation from other constructs that are included in models that seek to explain purchase intention such as TpB, TAM and UTAUT. Future research would do well to look at the influence of perceived fairness within the context of a fuller model.

Conflicts of interestFunding sources

This work has not received any external funding.

Competing interests

In accordance with Taylor & Francis policy and our ethical obligation as researchers, we confirm that at no point did the supporting company influence or guide the authors’ research.

Constraints on publishing

There are no constraints on publishing.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to acknowledge and thank ALEA, owners of the brand Slotsmillion.com, for the support provided in the collection of the data and for meeting the cost of the free spins incentive provided to players who completed the questionnaire for this research.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jirka Konietzny

Jirka KONIETZNY is a PhD student at the Department of Business Administration, Technology and Social Sciences at Luleå University of Technology, Luleå, Sweden. He is currently also working in CRM for a gambling company in Malta.

Albert Caruana

Albert CARUANA PhD is professor of marketing at the University of Malta, and at the University of Bologna, Italy. His research interests focus primarily on marketing communications and services marketing. His work includes papers in the Journal of Advertising, Journal of Advertising Research, Journal of Business Research, European Journal of Marketing and Industrial Marketing Management.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Action control: From cognition to behavior (pp. 11–39). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitude and predicting social behaviour. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Binde, P. (2005a). Gambling across cultures: Mapping worldwide occurrence and learning from ethnographic comparison. International Gambling Studies, 5(1), 1–27.

- Binde, P. (2005b). Gambling, exchange systems, and moralities. Journal of Gambling Studies, 21(4), 445–479.

- Casino City. (2017). Internet Gaming Directory. Retrieved June 10, 2017, from http://www.casinocity.com/

- Chan, F. K. Y., Thong, J. Y. L., Venkatesh, V., Brown, S. A., Hu, P. J.-H., & Tam, K. Y. (2010). Modeling citizen satisfaction with mandatory adoption of an e-government technology. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 11, 519–549.

- Chiu, C.-M., Lin, H.-Y., Sun, S.-Y., & Hsu, M.-H. (2009). Understanding customers’ loyalty intentions towards online shopping: An integration of technology acceptance model and fairness theory. Behaviour & Information Technology, 28, 347–360.

- Chiu, C.-M., & Wang, E. T. G. (2008). Understanding Web-based learning continuance intention: The role of subjective task value. Information & Management, 45, 194–201.

- CMA. (2017). CMA launches enforcement action against gambling firms. Retrieved July 23, 2017, from https://www.gov.uk/government/news/cma-launches-enforcement-action-against-gambling-firms

- Cook, C. (2017, July 17). Sarah Harrison the punters’ champion at the gambling commission. Retrieved July 23, 2017, from https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2017/jul/17/sarah-harrison-fighting-for-punters-gambling-commission

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297–334.

- Custer, R., & Milt, H. (1985). When luck runs out: Help for compulsive gamblers. New York: Facts on File Publications.

- Davis, F. D. (1985). A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: Theory and results. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- eMarketer. (2016). Slowing growth ahead for worldwide Internet audience. Retrieved May 7, 2017, from https://www.emarketer.com/Article/Slowing-Growth-Ahead-Worldwide-Internet-Audience/1014045

- European Gaming & Betting Association. (2016). Market reality. Retrieved April 5, 2016, from http://www.egba.eu/facts-and-figures/market-reality/

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behaviour: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Gainsbury, S. (2012). Internet gambling: Current research findings and implications. New York: Springer.

- Gainsbury, S., Parke, J., & Suhonen, N. (2013). Consumer attitudes towards internet gambling: Perceptions of responsible gambling policies, consumer protection, and regulation of online gambling sites. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 235–245.

- Gainsbury, S., Suhonen, N., & Saastamoinen, J. (2014). Chasing losses in online poker and casino games: Characteristics and game play of Internet gamblers at risk of disordered gambling. Psychiatry Research, 217, 220–225.

- Griffiths, M. D., & Carran, M. (2015). Are online penny auctions a form of gambling? Gaming Law Review and Economics, 19(3), 190–196.

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

- Hayes, A. F., Montoya, A. K., & Rockwood, N. J. (2017). The analysis of mechanisms and their contingencies: PROCESS versus structural equation modeling. Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ), 25(1), 76–81.

- Kaiser, H., & Rice, J. (1974). Little Jiffy, Mark Iv. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 34, 111–117.

- Keeter, S., Kennedy, C., Dimock, M., Best, J., & Craighill, P. (2006). Gauging the impact of growing nonresponse on estimates from a national RDD telephone survey. Public Opinion Quarterly, 70(5), 759–779.

- Lee, D.-C., Lin, S.-H., Ma, H.-L., & Wu, D.-B. (2017). Use of a modified UTAUT model to investigate the perspectives of internet access device users. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 33, 549–564.

- MacKinnon, D. P., Coxe, S., & Baraldi, A. N. (2012). Guidelines for the investigation of mediating variables in business research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 27(1), 1–14.

- Magsamen-Conrad, K., Upadhyaya, S., Joa, C. Y., & Dowd, J. (2015). Bridging the divide: Using UTAUT to predict multigenerational tablet adoption practices. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 186–196.

- Manfreda, K. L., Berzelak, J., Vehovar, V., Bosnjak, M., & Haas, I. (2008). Web surveys versus other survey modes: A meta-analysis comparing response rates. International Journal of Market Research, 50(1), 79–104.

- Moore, J. (2017). Gambling industry scores another own goal as CMA strikers threaten penalty area. Retrieved July 23, 2017, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/comment/gambling-industry-scores-another-own-goal-as-cma-strikers-threaten-penalty-area-a7804721.html

- Namkung, Y., & Jang, S. C. (2009). The effects of interactional fairness on satisfaction and behavioral intentions: Mature versus non-mature customers. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28, 397–405.

- Namkung, Y., & Jang, S. C. (2010). Effects of perceived service fairness on emotions, and behavioral intentions in restaurants. European Journal of Marketing, 44, 1233–1259.

- National Addiction Service of Singapore. (2013). Understanding your gambling addiction. Retrieved April 13, 2018, from https://www.imh.com.sg/uploadedfiles/Publications/Educational_Resources/Brochure_Understanding%20Your%20Gambling%20Addiction.pdf

- National Research Council (US) Committee on the Social and Economic Impact of Pathological Gambling. (1999). Pathological Gambling: A Critical Review. Gambling Concepts and Nomenclature, 2. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US).

- Oh, J.-C., & Yoon, S.-J. (2014). Predicting the use of online information services based on a modified UTAUT model. Behaviour & Information Technology, 33, 716–729.

- Oh, S., Lehto, X. Y., & Park, J. (2009). Travelers’ intent to use mobile technologies as a function of effort and performance expectancy. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 18, 765–781.

- Oliveira, T., Faria, M., Thomas, M. A., & Popovič, A. (2014). Extending the understanding of mobile banking adoption: When UTAUT meets TTF and ITM. International Journal of Information Management, 34, 689–703.

- Palmer, A., Beggs, R., & Keown-McMullan, C. (2000). Equity and repurchase intention following service failure. Journal of Services Marketing, 14, 513–528.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.

- Rodionova, Z. (2016). Online gambling firms face investigation for cheating customers. Independent. Retrieved July 23, 2017 from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/news/online-betting-firms-face-cma-investigation-cheating-a7373001.html

- Shaffer, H. J., Hall, M. N., & Vander Bilt, J. (1999). Estimating the prevalence of disordered gambling behavior in the United States and Canada: A research synthesis. American Journal of Public Health, 89(9), 1369–1376.

- Sheehan, K. B. (2001). E-mail survey response rates: A review. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 6. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2001.tb00117.x

- Su, L., & Hsu, M. K. (2013). Service fairness, consumption emotions, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions: The experience of chinese heritage tourists. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30, 786–805.

- Tan, P. J. B. (2013). Applying the UTAUT to understand factors affecting the use of english e-learning websites in Taiwan. SAGE Open, 3, 1–12.

- Taylor, S., & Todd, P. (1995). Understanding information technology usage: A test of competing models. Information Systems Research, 6, 144–176.

- UKGC. (2017a). Gambling business fined £300,000 for misleading advertising. Retrieved July 5, 2017, from http://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/news-action-and-statistics/news/2017/Gambling-business-fined-for-misleading-advertising.aspx

- UKGC. (2017b). Gambling operators face landmark enforcement action over unfair practices and promotions. Retrieved August 16, 2017, from http://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/news-action-and-statistics/news/2017/Gambling-operators-face-landmark-enforcement-action-over-unfair-practices-and-promotions.aspx

- UKGC. (2017c). Should society lotteries be more transparent about the money raised for good causes? Have your say. Retrieved August 16, 2017, from http://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/news-action-and-statistics/news/2017/Should-society-lotteries-be-more-transparent-about-the-money-raised-for-good-causes.aspx

- Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. (2000). A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Management Science, 46, 186–204.

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27, 425–478.

- Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., & Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157–178.

- Wong, C.-S., Law, K. S., & Huang, G. (2008). On the importance of conducting construct-level analysis for multidimensional constructs in theory development and testing. Journal of Management, 34(4), 744–764.

- Wood, R., & Griffiths, M. (2008). Why Swedish people play online poker and factors that can increase or decrease trust in poker Web sites: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Gambling Issues, 80–97. doi:10.4309/jgi.2008.21.8

- Wood, R., & Williams, R. (2009). Internet gambling: Prevalence, patterns, problems, and policy options (Final Report prepared for the Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre). Guelph, Ontario: Canada.

- Yani-de-Soriano, M., Javed, U., & Yousafzai, S. (2012). Can an industry be socially responsible if its products harm consumers? The case of online gambling. Journal of Business Ethics, 110, 481–497.