ABSTRACT

Online gambling is a profitable industry both in the regulated market and in the unregulated offshore market. Difficulties in regulating the offshore online markets are exacerbated by concerns over lacking consumer protection measures in offshore environments and reduced financial and tax revenue from gambling. Blocking is a measure employed by numerous regulators to prevent access or financial transactions to unregulated gambling sites. Yet, little is known about how well such strategies work. The current scoping review focuses on evidence on the effectiveness of blocking measures. Based on the review, 14 publications were identified. The analysis focused on four themes: implementation, effectiveness, risks, and alternatives. Results show that there is a paucity of empirical research on the effectiveness of blocking measures. The scarce evidence suggests that the effectiveness of blocking measures depends on implementation. Blocking without proper implementation may be an insufficient and disproportionate tool. The effectiveness of blocking is particularly limited by a constant need for updates in terms of technology and blocklists. We argue that research on and the effectiveness of blocking measures is obstructed by an asymmetry in expertise in three dimensions: Between regulators and industry; between ordinary and heavy gamblers; and between gambling and IT researchers.

Introduction

The online gambling market is rapidly growing. Expansion and introduction of licensing regimes, as well as the boost of online sales in some contexts during COVID-19 have contributed to the growth (Brodeur et al., Citation2021; S. M. Gainsbury et al., Citation2018). The compound annual growth rate of global gambling markets is estimated at over 11% for 2022–2027 (Mordor Intelligence, Citation2021). In 2023, the global online gambling market is estimated to reach 92.9 billion U.S. dollars (Statista, Citation2022). Following recent developments in opening online sports betting markets, North America is currently the fastest growing market for online gambling (Mordor Intelligence, Citation2021). Sports betting can be characterized as a driver of growth in the online gambling market (Nosal, Citation2022). In Europe, online channels are already estimated to make up about one-quarter of all gambling (EGBA, Citation2021), but the share of online channels can reach up to 60% in some European countries, such as Sweden and Denmark (EGBA, Citation2021).

The regulation of online gambling is complicated by the supranational nature of online environments. Online gambling shares many of the characteristics of land-based products, but regulation also needs to take into account online-specific questions related to issues, such as availability, accessibility, data protection, geographical reach, or emerging technologies (Fiedler, Citation2018; Sulkunen et al., Citation2019; Hörnle et al., Citation2018; Laffey et al., Citation2016). Offshore offer of gambling further complicates the regulatory approaches of jurisdictions. Offshore gambling refers to online gambling on websites that are not regulated or is illegal in the jurisdiction of the gambler (cf. Gainsbury et al., Citation2018). A large proportion of online gambling takes place in offshore websites, out of reach of national regulation. In Europe, the offshore market was estimated to be around 17% of the total gambling market in 2021 (EGBA, Citation2021). The importance of offshore markets varies depending on regulatory choices. In tightly regulated monopoly systems, such as Norway, Finland, or Québec, the share of offshore markets is already estimated to make up the bulk of online markets for some products (Nikkinen & Marionneau, Citation2020; Kairouz et al., Citation2018). Under licensing regimes, the share of offshore provision may also be important particularly for unregulated products (Fiedler, Citation2018).

Offshore gambling is highly challenging to regulate and prevent, as it is geographically located beyond the reach of national regulators. A variety of tools have been tested to control non-regulated offer. A recent report to the European Commission on the regulation of offshore online gambling (Hörnle et al., Citation2018) showed that blocking approaches, alongside restrictions on advertisement, were amongst the most used by national regulators. According to the report, 60% of EU/EEA Member States used website blocking while 30% had implemented payment blocking mechanisms. Blocking measures are also used elsewhere. For example, in Australia, the Australian Communications and Media Authority can ask service providers to block access to unauthorized gambling websites (ACMA, Citation2022). In Canada, Québec was the first province to introduce a website blocking scheme in 2015, but the provision was struck down in the Superior Court in 2018 as unconstitutional (French et al., Citation2021).

Blocking measures can take different forms. Website blocking refers to a practice where internet users trying to access unauthorized gambling websites are prevented access. Users are often redirected to landing pages informing them of the illegal nature of the offer (Hörnle et al., Citation2018). Payment blocking refers to targeting payments made to gambling websites, payments from gambling websites, or requests made to payment intermediaries to make their services unavailable (Hörnle et al., Citation2018). In other usage, blocking may also refer to software to block a user’s access to gambling apps and websites (Brownlow, Citation2021). However, these do not target offshore provision but can rather be used as tools for gambler auto-regulation and self-exclusion and are thus not part of this review.

The EU-level policy review conducted by Hörnle et al. (Citation2018) has thus far been the only review study on blocking policies. However, the focus of the study was on practical implementation within Europe only. There has not been a review available on global research on blocking, including how these measures are implemented in practice, and how functional or effective blocking measures have been. In the current study, we address these questions by conducting a scoping review on the research literature on the blocking of websites and of payment services.

Material and methods

Blocking is widely used by regulators. In the current scoping review, we mapped what research evidence is available on blocking, and what are the main findings (Grant & Booth, Citation2009). The main research question guiding the review was what different forms of website and payment blocking are used and how these are implemented.

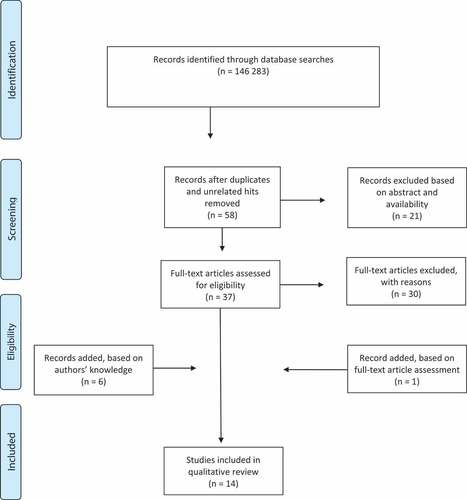

We conducted a literature search using the search string ‘gambling AND online AND block*’ in four scientific databases: Google Scholar, Scopus, ProQuest, and EBSCOhost (). Our inclusion criteria included literature addressing the effectiveness and implementation challenges of online gambling blocking measures by regulators. This excluded literature on individual use of blocking programs or applications to prevent the use of gambling websites or applications. In addition, we only included studies that focused mainly on blocking measures. We therefore excluded studies that merely mentioned blocking, such as more generic studies on online gambling regulation. As our interest was mainly in the effectiveness of blocking measures, we included only original empirical work and case studies. We therefore excluded discussion, opinion, and review papers. We did not set any limits on the publication years or geographical contexts of studies. For practical reasons, we excluded literature not available through the University of Helsinki Library services.

Table 1. Reviewed databases.

The initial search results of the four databases amounted to 146,283 hits (see PRISMA chart in for details).

Figure 1. Prisma flow chart. (According to Moher et al., Citation2009).

Taking into account a reasonable ratio between diminishing returns of relevant articles from continuous searches and the resources necessary to screen each hit (Stevinson & Lawlor, Citation2004), we decided to include the first 50 hits for databases exceeding this amount, sorted by relevance (see also Pham et al., Citation2014 using a comparable strategy). After removing duplicates and clearly unrelated hits based on a first scan of titles, 58 records remained for closer analysis. Based on the abstracts, another 21 records were excluded as irrelevant as per our inclusion criteria. We assessed the eligibility of the remaining articles by reading through the full texts. The full-text assessment resulted in the exclusion of further 30 records. Most of these were excluded based on the fact that they only mentioned blocking as part of wider legal evaluations and discussions of online gambling regulation (mainly in the US). Other excluded records focused more specifically on e.g. blockchain technology, cryptocurrencies, or advertising restrictions, instead of blocking. The sample consisted of seven studies, to which we added one (Ververis et al., Citation2015), which was referenced in one of the reviewed articles and which was clearly identifiable as fitting our inclusion criteria. In addition, we added six publications (Fiedler, Citation2020; Fiedler, Steinmetz, & von Meduna, Citation2020; Steinmetz & Ante, Citation2020; Steinmetz, Ante, et al., Citation2020; Steinmetz, von Meduna, et al., Citation2020 Thoma & Fiedler, Citation2020), presenting national regulators’ experiences with using blocking measures. This addition was based on our previous knowledge of these country case studies. While we put the emphasis on the primary empirical work, the added country case studies helped in exemplifying and contextualizing the results from the empirical studies on blocking measures. The final sample therefore consisted of 14 studies. The included studies consist of seven country case studies, three legal analyses, three studies of blocking measures’ effectiveness and implementation, and one political analysis (see ).

Table 2. Included studies.

The analysis followed four main topics: practical and technological implementation, effectiveness and functionality, risks, and alternatives to website and payment blocking. We did not assess the quality of the included studies, as, in line with scoping review methodology, our aim was rather to map the field (Grant & Booth, Citation2009).

Results

The main results of the review are summarized in . Overall, there is a paucity of empirical research on the practicalities and the effectiveness of blocking measures related to both website and payment blocking. There is also limited evidence on their effectiveness despite widespread usage.

Table 3. Main results of reviewed literature.

Practical and technological implementation

The literature only sparsely evaluates the direct effectiveness or functionality of blocking measures. It is therefore beneficial to first lay out the forms of practical implementation of the blocking measures discussed in the reviewed literature.

Offshore gambling is typically available through websites licensed in low-regulation and low-tax jurisdictions, but not in the country of consumption. The three most common measures employed by countries of consumption to block such offer are: (1) internet protocol (IP) address blocking, (2) domain name system (DNS) blocking, and (3) uniform resource locators (URL) blocking. DNS blocking is the cheapest and easiest, and therefore widely used (Schmidt-Kessen et al., Citation2019). IP blocking is effective but carries the risk of ‘over blocking’: Many websites are hosted under one IP address including also legitimate (i.e. non-blocked) addresses (Schmidt-Kessen et al., Citation2019). This renders this method less functional in achieving the goal of preventing offshore gambling, as it entails the risk of unjustly restraining legitimate traffic. URL blocking is precise but requires deep-packet-inspection (DPI) (Schmidt-Kessen et al., Citation2019). The DPI technique enables Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to monitor communication. This, yet, may be problematic due to privacy rights (Schmidt-Kessen et al., Citation2019; Ververis et al., Citation2017). DPI is also costly and difficult to use for encrypted connections (Schmidt-Kessen et al., Citation2019).

The effectiveness of each of the three blocking methods depend on and require practical enforcement, typically undertaken by ISPs. The existing evidence shows that for example in Quebec, the initial bill intended to task the ISPs with blocking addresses within 30 days of their appearance on an updated blocklist (French et al., Citation2021). In Malaysia, the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) can task ISPs with blocking offshore online gambling as well as offshore gambling advertising, as per the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Act (Dhillon et al., Citation2021). ISP blocking processes can also be more complicated, and blocking may in some cases, such as in France, require a court decision (Fiedler, Citation2020). A court decision, while slowing the process down, may be functional in securing citizen and commerce rights to a larger degree.

Each blocking method also depends on the creation and updating of a blocklist. This can be done manually or automatically, for example by using gambling related keywords. The latter, nevertheless, entails a high risk of over blocking (Dewar, Citation2001). Denmark is using an automated search engine particularly developed to identify illegal online gambling offers (Steinmetz, Ante, et al., Citation2020). However, Steinmetz, Ante, et al. (Citation2020) do not explain how the software operates or how over blocking could be avoided. Another study on blocking measures in Greece (Ververis et al., Citation2015) highlights the difficulties in keeping a blocklist up-to-date. In Greece, the list is updated manually and provided to ISPs as a downloadable PDF. In Cyprus, a text file of the local blocklist with file paths is publicly available (Ververis et al., Citation2017). The Cypriot blocklist has grown rapidly in size: from 95 entries in February 2013 to 2,563 in April 2017 (Ververis et al., Citation2017). Updating such lists is therefore highly resource intensive if not done using automated tools.

Access to offshore gambling can also be blocked by targeting payments to these websites instead of the websites. Very little research was found on the practical and technological implementation of payment blocking, and the practicalities were described vaguely. For instance, in the United States, ‘[t]he details of enforcing this prohibition [are] left up to the Federal Reserve System, “which prescribes regulations that banks and credit card companies must follow to identify and block restricted transactions.”’ (Grahmann, Citation2008, p. 173). Payment blocking can in some cases be less demanding than website blocking. For example in France, website blocking requires a court decision, but payment blocking is possible at the initiative of the national gambling authority (the ANJ, formerly ARJEL) (Fiedler, Citation2020). The authority has nevertheless not made use of this right so far (Fiedler, Citation2020), suggesting the possibility of other administrative hurdles in the process.

Effectiveness and functionality of blocking

The effectiveness of blocking can be measured in terms of either preventing or at least decreasing the consumption of offshore gambling. Experiences of effectiveness appear to vary across countries that have adopted blocking. An early contribution by Dewar (Citation2001) evaluated the cases of the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. While the study may be the first academic paper on blocking, the results are not surprising. Dewar (Citation2001) finds that blocking never prevents all offshore gambling. The leak is attributed to skilled users capable of circumventing blocks. More recent experiences from Denmark (Steinmetz, Ante, et al., Citation2020), Germany (Fiedler, Steinmetz, & von Meduna, Citation2020), France (Fiedler, Citation2020), and Malaysia (Dhillon et al., Citation2021) show that in addition to users, other factors also impact the effectiveness of blocking. An important issue is the flexibility of offshore providers, including capability of swiftly changing their blocked IP-address (Dhillon et al., Citation2021). An offshore gambling website with a new IP-address becomes accessible which can decrease the overall effectiveness of website blocking. Another issue relates to the adequate resourcing of regulators (Fiedler, Steinmetz, & von Meduna, Citation2020), as well as their willingness and capability to employ blocking measures (Fiedler, Citation2020; Steinmetz, Ante, et al., Citation2020). Implementation processes are also crucial to the success of the measures (Fiedler, Citation2020). For instance, Grahmann (Citation2008, p. 177) shows that the combination of payment and ISP blocking is more effective, a so-called ‘belt and suspenders approach’.

Our review identified only two analyses estimating the technical effectiveness of blocking measures (Ververis et al., Citation2015, Citation2017). These two studies focused on Greece and Cyprus and analyzed end-user connections (Ververis et al., Citation2017) and ISP data (Ververis et al., Citation2015). In the case of Greece, Ververis et al. (Citation2015) utilized the open-source software Ooniprobe ‘to probe [the] network for signs of network tampering, surveillance or censorship.’ (Ververis et al., Citation2015, p. 2). In both countries, a number of URLs listed on blocklists were accessible. In Greece, internet service providers blocked between 22% and 100% of listed URLs (Ververis et al., Citation2015). In addition, blocklists were deficient, and contained malformed and expired URL addresses, duplicates, and non-gambling addresses (three on the Greek list and one on the Cypriot list) (Ververis et al., Citation2015, Citation2017). The deficient implementation of the website blocking reduces effectiveness and may overly restrain citizen rights.

Effective implementation of particularly website blocking can be improved by so-called landing pages (sometimes also named ‘block pages’). Landing pages are websites on which users trying to reach blocked gambling sites are redirected. In a study by Schmidt-Kessen et al. (Citation2019), at least the Estonian, French, Spanish, and Polish gambling regulators employed such a measure. Landing pages were identified as important in informing users about why they did not reach the desired website. If landing pages are not used, such as in Greece, the end user is often only faced with an unspecified timeout messages or error notice (e.g. the 404 http error) (Ververis et al., Citation2017). The failure to inform the consumer of the blocking is a major shortcoming: if a restriction on the freedom of communication is deemed necessary to prevent gambling harms, this should also be communicated to the user. In addition, as many online gamblers are unsure about the legal status of different online gambling operators (Gainsbury et al., Citation2018), landing pages can be used as a tool to inform consumers about national regulations (Schmidt-Kessen et al., Citation2019). As an information tool, landing pages should therefore include information in several languages (covering also minority languages), avoid legal jargon, provide a link to a list of the licensed operators (aka whitelist) and a link to the official web page of the regulator, include a warning of risks of using offshore operators and of gambling in general, provide a link to self-help tools, and finally contact information of the regulator, as well as problem gambling help services (Schmidt-Kessen et al., Citation2019). Outdated landing pages as in the case of Cyprus (Ververis et al., Citation2017) may undermine the effectiveness of this measure. In addition to their value as tools of communication, landing pages can also be used by regulators to monitor online traffic (Schmidt-Kessen et al., Citation2019).

No studies evaluated the effectiveness of payment blocking. However, it has been suggested elsewhere that payment blocking is complicated by the use of foreign payment services and digital wallets (Hörnle et al., Citation2018). According to market intelligence, about one-half of all gambling-related banking transactions are conducted via PayPal. Card payments and bank transfers make up slightly over one-quarter of payments. The remainder consists of other payment services such as Google and Apple pay (Mordor Intelligence, Citation2021).

Risks of blocking

The previous two sections have looked at the technical and practical questions involved in the use of blocking measures. Nevertheless, based on the current review, the main concerns related to both website and payment blocking revolve around privacy, data protection, and censorship (French et al., Citation2021; Grahmann, Citation2008; Hudelcu, Citation2021; Schmidt-Kessen et al., Citation2019; Steinmetz & Ante, Citation2020; Ververis et al., Citation2015). For example, an analysis of political documents in Québec showed that censorship concerns were strongly present (French et al., Citation2021). In addition, concern was voiced over the leaking of gambling expenditures of Québec residents toward unlicensed sites. Somewhat surprisingly, the risks of offshore companies targeting and attracting consumers, as well as the concerns of gamblers were absent in the analyzed studies. This observation suggests a one-sided perspective on the risks of blocking. Furthermore, alternative perspectives on the risks of privacy and censorship were also present. A legal analysis in Romania (Hudelcu, Citation2021) concludes that the blocking of unauthorized gambling sites does not violate the privacy of communication, ‘as access to the site remains the same, the site does not undergo any transformation under the action of the first warning page, both for individuals and the owner of the IT platform’ (Hudelcu, Citation2021, p. 82).

Risks related to payment blocking are much less discussed in the material. Steinmetz and Ante (Citation2020) observe that at least in the case of Norway, the necessity of registering the bank account data of citizens complicated the introduction of this measure. On the other hand side, the Norwegian Gambling and Foundation Authority considers payment blocking as effective (Norwegian Gambling and Foundation Authority, Citation2022), and thus despite the data protection concerns, ordered Norwegian banks to block transactions (ibid.). Also due to the remaining privacy concerns, the Norwegian gambling regulation is currently undergoing a reform (Vixio Gambling Compliance, Citation2022).

Alongside concerns regarding privacy and citizen rights, another risk associated with blocking relates to the freedom of trade. Hudelcu’s (Citation2021) legal evaluation of the Romanian online gambling regulation addresses the issue of the freedom of trade. Hudelcu’s (Citation2021) concludes that private business interests are not violated, at least in the light of the Romanian constitution. Ververis et al. (Citation2015, Citation2017) mention the risk of under and over blocking. While under blocking is mainly a question of effectiveness, over blocking touches upon freedom of trade in cases when non-gambling websites are blocked by mistake. In some cases, over blocking may also involve targeting company e-mail connections in addition to websites (Ververis et al., Citation2015, Citation2017). Such deficient implementation is not only problematic from the perspective of consumer information, but also from the perspective of impeding business also in jurisdictions where operation is licensed.

Alternatives to website and payment blocking

Taking into account the multiple challenges in implementing blocking measures effectively and the diverse concerns voiced against these measures, some research has also discussed the alternatives available to blocking measures.

Grahmann (Citation2008) suggests a sounder implementation of payment blocking by targeting a wider network of ‘payment systems’ and expecting the financial industry to find creative solutions and legislative loopholes. Dewar (Citation2001) similarly discusses a possible liability of ISPs and payment providers in effectively implementing the blocking measures. However, as these suggestions are not so much an alternative but rather improvements of existing measures, they may not be sufficient in reducing the risks related to blocking measures.

As blocking can have limited effectiveness, some jurisdictions (e.g. Denmark and Spain) complement their blocking measures and blocklists with whitelists and official labels for licensed providers (Steinmetz, Ante, et al., Citation2020; Steinmetz, von Meduna, et al., Citation2020). This strategy may be more effective from the perspective of consumers, as it also serves as a tool for informing consumers of what part of the offer is licensed (cf. Gainsbury et al., Citation2019; Gainsbury et al., Citation2018), instead of assuming that the majority of consumers directly and willingly choose offshore gambling.

Finally, targeting the entire ‘eco-system’ of the online gambling economy has been discussed before as an alternative or addition to the website and payment blocking (Hörnle et al., Citation2018). This measure would consist of targeting the wider production chains of online gambling. For example in 2020, the Malaysian police raided a software company providing online gambling applications to foreign businesses (Dhillon et al., Citation2021). While such an approach faces many of the same difficulties as other blocking and is typically limited to the jurisdictional level (Hörnle et al., Citation2018), this type of an eco-system approach may provide additional or alternative levers to the regulators in preventing and blocking offshore gambling.

Discussion

This scoping review has charted the available academic literature on the practical implementation, as well as the functionality and effectiveness of online offshore gambling blocking measures. The results indicate an asymmetry in expertise in three dimensions: Between regulators and industry; between ordinary and heavy gamblers; and between gambling researchers and IT-researchers.

Technically lacking implementation may be due to limited technical expertise of the regulators (Ververis et al., Citation2015, Citation2017), but this shortcoming may also make it easier to intentionally or accidentally circumvent blocking measures (Dewar, Citation2001; Ververis et al., Citation2017). As Gainsbury et al. (Citation2018, Citation2019) have shown, ordinary consumers prefer regulated domestic provision, but are at the same time unaware of which providers are licensed. They might thus by accident or unknowingly end up gambling offshore. Well-designed landing pages appear to be a good way forward also as tools of information (Schmidt-Kessen et al., Citation2019). Heavy gamblers, (including both those experiencing problems with their gambling and those identifying as professional gamblers), are more likely to make the effort to circumvent blocks in order to access additional or more attractive gambling offers. While online offshore gambling can never be prevented completely a mixture of measures decreases the chances of circumvention (cf. Grahmann, Citation2008). Increasing popularity of gambling via mobile apps rather than web browsers (e.g. EGBA, Citation2021) also necessitate extending blocking measures to app stores. This, in fact, may prove more feasible in national contexts due to the proprietary nature and quasi-duopolistic markets of mobile app distribution.

The current review confirms that ‘the effectiveness of [these] blocking measures is largely untested’ (Mangion, Citation2010, p. 368): there is a paucity of academic empirical work concerning the effectiveness of blocking measures. We were able to locate only two technical evaluations of offshore gambling website blocking (Ververis et al., Citation2015, Citation2017), and even in these cases the main topic of interest was internet censorship. Researchers with the necessary expertise seem to take gambling only as a case but with a different research frame and goal, whereas most gambling researchers probably lack the expertise to technically evaluate online gambling and its regulation. Multi-disciplinary approaches could fill this gap in research and in assessing the effectiveness of blocking in the field of online offshore gambling.

The risks related to blocking measures are somewhat more discussed in the literature. Censorship and related issues of privacy and data protection were the main points of concern in the reviewed literature. Such concerns are understandable from a citizen rights perspective. However, blocking of internet content can also be tolerated and acceptable from a legal perspective to prevent other harmful or illegal content (e.g. copyright infringements in the United States, cf. Seltzer, Citation2011). In particular, the blocking of websites infringing on copyrights highlights that blocking can work in practice. This holds potential lessons also for the blocking of online offshore gambling. The protection of intellectual property right faces similar challenges: national bans do not reach hosts with questionable content beyond the national borders and the circumvention of website blocking remains an option (Marsoof, Citation2015). While the evaluation of the effectiveness of website blocking is challenging, evidence indicates that the blocking of websites infringing on property rights, had an overall positive effect in reducing illegal content in the UK (Riordan, Citation2017). Although circumvention remains a possibility also in the UK, it entails costs (including monetary). As suggested by Riordan (Citation2017, p. 304) ‘for a sufficiently robust form of blocking, many users will simply not possess the technical skill required to restore access’ (ibid.: p. 304). Furthermore, to avoid the tedious and resource-intensive manual update of blocking lists, the use of machine learning has been suggested to identify websites with piracy content (Jilcha & Kwak, Citation2022). Albeit their specific take on using ad banners placed on piracy websites might not be directly translatable to identify online offshore gambling websites, machine learning may be suitable in keeping track in particular dynamic online environments (ibid.).

Within the European Union, blocking gambling websites from other Member States has also been termed a form of economic patriotism and market protectionism (cf. Laffey et al., Citation2016; similarly French et al., Citation2021 in Québec). In some of the reviewed publications (Grahmann, Citation2008; Hudelcu, Citation2021; Ververis et al., Citation2015, Citation2017) the question of freedom of trade arose as another concern against blocking. While blocking does not need to collide with constitutional rights for freedom of trade (Hudelcu, Citation2021), problems in the technical implementation of blocking (Ververis et al., Citation2015, Citation2017) can result in over blocking and thus violating constitutional rights.

Proper technical implementation of payment and website blocking is crucial. Juridical processes are not sufficient in implementing effective blocking if technical implementation does not follow. Regulators should thus make sure to build up the necessary technical resources and expertise (cf. Casey, Citation2022).

National-level measures may nevertheless not be sufficient in the long run. The online gambling market is becoming increasingly concentrated in multi-national companies, following mergers and a geographical (cross-national) expansion (Mordor Intelligence, Citation2021). The regulation of these powerful corporations, as in the case of any multi-national actors, remains challenging for national regulators. Models of co-regulation have emerged as one solution to the limited possibilities of national governments to regulate transnational online environments and to involve corporations in their own regulation (Gorwa, Citation2019). Abbott and Snidal (Citation2009) have discussed the so-called governance triangle, comprised of states, corporations, and NGOs. With sufficient resources, regulation can also expand to the entire ‘eco-system’ of the online gambling industry, including also intermediaries, such as software providers, testing houses, or advertising companies (e.g. Casey, Citation2022; Dhillon et al., Citation2021; Egerer et al., Citation2018; Hörnle et al., Citation2018; Marionneau & Nikkinen, Citation2020).

The aim of this scoping review was to chart the available information on the implementation and effectiveness of website and payment blocking targeting offshore gambling. The study has been limited to four databases. A more expanded review may be necessary in the future. More urgently, more empirical evidence on the technical, legal, and commercial implications of blocking is needed. Otherwise, regulators are left with scant evidence to support decisions that may eventually prove to be inefficient and even harmful to individual and trade rights. The existing work on blocking measures nevertheless demonstrates that the practical implementation (administrative and technical) is paramount in making the measures effective as well as constitutional.

Disclosure statement

Egerer and Marionneau have during the last three years received funding from the Finnish Foundation for Alcohol Studies (FFAS) based on §52 of the Finnish Lotteries Act to support conference travel and research. Both are funded by the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health within the objectives of §52 of the Lotteries Act. The funds based on § 52 stem from a mandatory levy on the Finnish gambling monopoly to support research and treatment. The funds are circulated via the Ministry, and the monopoly has no influence on how the money is distributed. Neither the Ministry, the FFAS northern gambling monopoly pose restrictions on publications. During the last three years, Marionneau has also received funding from the Academy of Finland.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michael Egerer

Michael Egerer is a University Researcher at the University of Helsinki Centre for Research on Addiction, Control, and Governance (CEACG). His research interests address gambling, gambling regulations and the concept of addiction. He is the chair of the Finnish Association for Alcohol, Drug and Gambling Research.

Virve Marionneau

Virve Marionneau is a University researcher focusing mainly on gambling policies, institutional perspectives, and the political economy of gambling. She has several projects focusing mainly on international comparisons, such as the Assessment tool for gambling regulation project, and two projects on the impacts of COVID-19 on gambling.

References

- Abbott, K. W., & Snidal, D. (2009). Strengthening international regulation through transmittal new governance: Overcoming the orchestration deficit. Vand. J. Transnat'l L, 42, 501–578.

- ACMA. (2022). Blocked gambling websites. Accessed: July 5, 2022, https://www.acma.gov.au/blocked-gambling-websites

- Brodeur, M., Audette-Chapdelaine, S., Savard, A. C., & Kairouz, S. (2021). Gambling and the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 111, 110389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110389

- Brownlow, L. (2021). A review of mHealth gambling apps in Australia. Journal of Gambling Issues, (47), 47. https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2021.47.1

- Casey, D. (2022). The role and influence of test houses in gambling regulation and markets. In J. Nikkinen, V. Marionneau, & M. Egerer (Eds.), The global gambling industry, structures, tactics, and networks of impact (pp. 165–178). Springer.

- Dewar, L. (2001). Regulating internet gambling: The net tightens on online casinos and bookmakers. Aslib Journal of Information Management in 2014, 53(9), 353–367.

- Dhillon, G., Ling, L. S., Nandan, M., & Nathan, J. T. X. (2021). Online gambling in Malaysia: A legal analysis. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, 29(1), 207–220. https://doi.org/10.47836/pjssh.29.1.12

- EGBA. (2021). European online gambling key figures 2021 edition. Retrieved August 2, 2022, https://www.egba.eu/uploads/2021/12/European-Online-Gambling-Key-Figures-2021-Edition.pdf

- Egerer, M., Marionneau, V., & Nikkinen, J. (Eds.). (2018). Gambling policies in European welfare states. Current challenges and future prospects. Springer.

- Fiedler, I. (2018). Regulation of online gambling. Economics and Business Letters, 7(4), 162–168. https://doi.org/10.17811/ebl.7.4.2018.162-168

- Fiedler, I. (2020). Frankreich. In I. Fiedler, F. Steinmetz, L. Ante, & M. von Meduna (Eds.), Regulierung von onlineglücksspielen (pp. 261–329). Springer.

- Fiedler, I., Steinmetz, F., & von Meduna, M. (2020). Deutschland. In I. Fiedler, F. Steinmetz, L. Ante, & M. von Meduna (Eds.), Regulierung von onlineglücksspielen (pp. 111–230). Springer.

- French, M., Tardif, D., Kairouz, S., & Savard, A. C. (2021). A governmentality of online gambling: Quebec’s contested internet gambling website blocking provisions. Canadian Journal of Law and Society/La Revue Canadienne Droit Et Société, 36(3), 483–504. https://doi.org/10.1017/cls.2021.9

- Gainsbury, S., Abarbanel, B., & Blaszczynski, A. (2019). Factors influencing internet gamblers’ use of offshore online gambling sites: Policy implications. Policy & Internet, 11(2), 235–253. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.182

- Gainsbury, S. M., Russell, A. M., Hing, N., & Blaszczynski, A. (2018). Consumer engagement with and perceptions of offshore online gambling sites. New Media & Society, 20(8), 2990–3010. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817738783

- Gorwa, R. (2019). The platform governance triangle: Conceptualising the informal regulation of online content. Internet Policy Review, 8(2), 1–22.

- Grahmann, K. P. (2008). Betting on prohibition: The federal government’s approach to internet gambling. Northwestern Journal of Technology and Intellectual Property, 7(2), 162–184.

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Hörnle, J., Litler, A., Tyson, G., Padumadasa, E., Schmidt-Kessen, M., & Ibosiola, D. (2018). Evaluation of regulatory tools for enforcing online gambling rules and channelling demand towards controlled offers. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Hudelcu, D. (2021). Interference of the legitimate public and private interest in exercising the competences of the national office of gambling. Perspectives of Law and Public Administration, 10(1), 79–88.

- Jilcha, L. A., & Kwak, J. (2022). Machine learning-based advertisement banner identification technique for effective piracy website detection process. CMC-COMPUTERS MATERIALS & CONTINUA, 71(2), 2883–2899. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2022.023167

- Kairouz, S., Fiedler, I., Monson, E., & Arsenault, N. (2018). Exploring the effects of introducing a state monopoly operator to an unregulated online gambling market. Journal of Gambling Issues, January 2018(37), 136–148.

- Laffey, D., Della Sala, V., & Laffey, K. (2016). Patriot games: The regulation of online gambling in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(10), 1425–1441.

- Mangion, G. (2010). Perspective from Malta: Money laundering and its relation to online gambling. Gaming Law Review and Economics, 14(5), 363–370.

- Marionneau, V., & Nikkinen, J. (2020). Stakeholder interests in gambling revenue: An obstacle to public health interventions? Public Health, 184(July 2020), 102–106.

- Marsoof, A. (2015). The blocking injunction–A critical review of its implementation in the United Kingdom within the legal framework of the European Union. IIC-International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law, 46(6), 632–664.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). The PRISMA group. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

- Mordor Intelligence. (2021). Global online gambling market (2021-2026). Retrieved July 5, 2022, https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/online-gambling-market

- Nikkinen, J., & Marionneau, V. (2020). On the efficiency of Nordic state-controlled gambling monopolies. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 38(3), 212–226.

- Norwegian Gambling and Foundation Authority. (2022). Gambling in norway. Retrieved June 28, 2022, https://lottstift.no/en/gambling-in-norway/

- Nosal, P. (2022). A Wealthy Marriage? The Politics and Economy of Sports Betting in Poland. In J. Nikkinen, V. Marionneau, & M. Egerer (Eds.), The Global Gambling Industry. Structures, Tactics, and Networks of Impact (pp. 151–164). Springer.

- Pham, M. T., Rajić, A., Greig, J. D., Sargeant, J. M., Papadopoulos, A., & McEwen, S. A. (2014). A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Research Synthesis Methods, 5(4), 371–385.

- Riordan, J. (2017). Website blocking injunctions under United Kingdom and European law. In G. Dinwoodie (Ed.), Secondary liability of internet service providers (pp. 275–315). Springer.

- Schmidt-Kessen, M. J., Hörnle, J., & Littler, A. (2019). Preventing risks from illegal online gambling using effective legal design on landing pages. Journal of Open Access List, 7(2019), 1–22.

- Seltzer, W. (2011). Infrastructures of Censorship and Lessons from Copyright Resistance. San Francisco, CA, FOCI '11 workshop, August. Retrieved March 13, https://www.usenix.org/legacy/event/foci11/tech/final_files/Seltzer.pdf

- Statista. (2022). Market size of the online gambling industry worldwide from 2019 to 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2022 https://www.statista.com/statistics/270728/market-volume-of-online-gaming-worldwide/

- Steinmetz, F., & Ante, L. (2020). Norwegen. In I. Fiedler, F. Steinmetz, L. Ante, & M. von Meduna (Eds.), Regulierung von onlineglücksspielen (pp. 450–487). Springer.

- Steinmetz, F., Ante, L., & von Meduna, M. (2020). Dänemark. In I. Fiedler, F. Steinmetz, L. Ante, & M. von Meduna (Eds.), Regulierung von onlineglücksspielen (pp. 74–109). Springer.

- Steinmetz, F., von Meduna, M., & Ante, L. (2020). Spanien. In I. Fiedler, F. Steinmetz, L. Ante, & M. von Meduna (Eds.), Regulierung von onlineglücksspielen (pp. 490–526). Springer.

- Stevinson, C., & Lawlor, D. A. (2004). Searching multiple databases for systematic reviews: Added value or diminishing returns? Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 12(4), 228–232.

- Sulkunen, P., Babor, T., Cisneros Örnberg, J., Egerer, M., Hellman, M., Livingstone, C., Marionneau, V., Nikkinen, J., Orford, J., Room, R., & Rossow, I. (2019). Setting limits: Gambling. Science and Public Policy. Oxford University Press.

- Thoma, G., & Fiedler, I. (2020). Italien. In I. Fiedler, F. Steinmetz, L. Ante, & M. von Meduna (Eds.), Regulierung von onlineglücksspielen (pp. 395–447). Springer.

- Ververis, V., Isaakidis, M., Loizidou, C., & Fabian, B. (2017). Internet censorship capabilities in Cyprus: An investigation of online gambling blocklisting. In: International Conference on e-Democracy, Athens, Greece. (pp. 136–149). Springer.

- Ververis, V., Kargiotakis, G., Filastò, A., Fabian, B., & Alexandros, A. (2015). Understanding internet censorship policy: The case of greece. In 5th USENIX Workshop on Free and Open Communications on the Internet (FOCI 15). (pp. 1–11). Retrieved May 17, 2022, https://www.usenix.org/system/files/conference/foci15/foci15-paper-ververis-updated-2.pdf.

- Vixio Gambling Compliance. (2022). Norwegian culture ministry notifies EU commission of regulations on gambling. Retrieved June 28, 2022, https://gc.vixio.com/regulatory-update/norwegian-regulations-gambling-notified-eu-commission