ABSTRACT

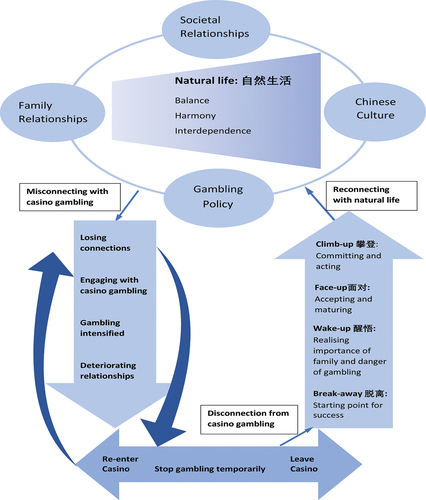

With commercial casinos proliferating over the past two decades, gambling-related harm has attracted attention in terms of both research and development of treatment strategies. A problematic relationship with gambling has major consequences for gamblers, families, communities, and society. This paper aims to present a better understanding of Chinese migrants’ experiences of responding to casino gambling harm in New Zealand using an interpretive phenomenological approach. Sixteen recent Chinese migrants were interviewed: eight people who self-identified as gambling problematically and eight affected family members. Data analysis incorporated a thematic approach involving multiple readings of interview transcripts and iterative processing of developing themes. The key findings are organized into a model involving four stages: misconnection (pathways into excessive gambling), disconnecting (moving away from casino gambling), reconnection (settling into their new social environment), and rebuilding a ‘natural life’ (a Chinese cultural conception of recovery). This process model helps understanding the Chinese migrants’ experience of responding to gambling harm in a broad social-cultural-historical context.

Introduction

With the growth of commercial casinos over the last two decades, scholars globally report concern about gambling-related harm. Gambling poses various levels of harm for gamblers and people around them. The harm includes financial hardship, relationship disruption, psychological distress, detrimental impacts to health, cultural harms, impaired work performance and criminal activity (Langham et al., Citation2016). Engaging with electronic gaming machines (EGMs) and casino-table gambling have been identified as the most harmful modes of gambling compared with other modes of legalized gambling (e.g. lottery products) (Abbott & Volberg, Citation2000). Indeed, the rate of problem gambling among casino gamblers is much higher than the rate in the general population (Fisher, Citation2000).

In many western countries, including New Zealand, Asian migrants have been reported to be vulnerable to gambling harm and, in addition, they are most likely to be harmed by engaging with casino gambling (Chen & Dong, Citation2015; Lai, Citation2006; Oei & Raylu, Citation2010; Sobrun-Maharaj et al., Citation2013). This vulnerability applies to all immigrants who face immigration and post-immigration adjustment issues in their host country, including language barriers, employment opportunities, access to local services, housing and transportation, and prejudice (Li & Chong, Citation2012; Tse et al., Citation2012). Social connections, entrepreneurship and sustainable communities were reported as significant aspects for strengthening Chinese migrants’ settlement and wellbeing in their host countries (Li & Chong, Citation2012). Current understanding of how recent Chinese migrants respond to harms related to casino gambling has attracted little research attention (Zhang & Hans, Citation2012) and an approach that seeks the views of those who have been affected will assist in developing appropriate policy and services. A study was undertaken to examine casino gambling harm experienced by Chinese migrants through a Chinese cultural lens (Zhang, Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2022). The study aimed to better understand 1) Chinese migrants who gamble and their affected family members’ experience in responding to casino gambling harm, and 2) their experiences of the influential aspects impacting on their responses. The research question “What are the Chinese migrants’ experiences of responding to casino gambling harm in New Zealand?” guided the study. The focus of this article is on selected elements of the project which resulted in the development of a process model.

Trends in addiction theories and treatment approaches

A review of the literature on responses to gambling harm revealed three trends. The first trend indicated that understandings of problem gambling are shifting from focusing on the personalities of individual consumers (see, for example, Blaszczynski & Nower, Citation2002) to examining associated systems and processes (Adams, Citation2009; Orford, Citation2020). Recent studies have highlighted how features of casinos – physical setting, games design and operational systems – are purposely designed to create more business and, consequently, these generate more individuals who gamble problematically (Schüll, Citation2012). Casinos promote their gambling as entertainment for ordinary people, but this disguises the reality that gambling is capable of generating physical, social and psychological harms. Furthermore, the casino gambling industry did not emerge from grass-roots demand for gambling but emerged out of the ambitions of governments and industry (Orford, Citation2020). The primary problem with gambling is not the problem gambler, but the escalating consumption of gambling profits (Adams, Citation2007).

The second trend regarding approaches to intervention is the shift from a medical model to a recovery model (White, Citation2007). The shift carries with it a transition from a practitioner-led response to a clinical disease to a person-led journey of recovery. In the addiction field, recovery is increasingly recognized as a personal journey that occurs through changes in social networks (Best et al., Citation2016). Natural recovery is understood to occur when people have enough resources to recover from addiction without formal or informal support (Granfield & Cloud, Citation2001). In line with this approach, the concept of ‘recovery capital’ provides a useful framework for looking more broadly at the social environment that supports recovery processes (Granfield & Cloud, Citation2001). The concept of recovery capital has been tested in the field of problem gambling by Gavriel-Fried and Lev-El (Citation2020). The study identified several unique resources for people recovering from problematic gambling, including awareness of gambling harm, irrespective of its legal status. The authors advocated for people who engaged in gambling to challenge the normalizing of gambling and to develop a knowledgeable and critical awareness (‘capital’) of the social and economic forces behind the deceptive mechanisms that encourage gambling (Gavriel-Fried & Lev-El, Citation2020).

The third trend is a paradigm shift from an individualized focus to a relational focus in a social world (e.g. Adams, Citation2008, Citation2016; B. K. Alexander, Citation2012). According to B. Alexander (Citation2010), ‘dislocation’ produces insufficient ‘psychosocial integration,’ making a severe and prolonged dislocation difficult to endure. Maintaining supportive relationships with families or communities is essential for human survival. Dislocation theory of addiction contends that when people experience inadequate psychosocial integration, they engage in excessive alcohol or other drug use, or gambling as a way of easing psychological distress (B. Alexander, Citation2010). Adams (Citation2008) located the current dominant paradigm of understanding addiction in what he refers to as a ‘particle paradigm.’ That is ‘a cluster of assumptions that revolve around the idea that the self is primarily an individual object and that this object – or particle – is the appropriate focal point for understanding addictive processes’ (p. 23). In contrast to the particle paradigm, a social paradigm views people as being positioned in their relationships. This paradigm sees people as being embraced in a web of connections which is inseparable from other people and the surrounding context in which they move. Further to this theory is the idea that addiction occurs when the relationship with an addictive substance or process intensifies to the detriment of other relationships. The dislocation theory of addiction and the social-ecological model offers a more appropriate base for understanding Chinese migrants’ experience of responding to casino gambling harm in a social and cultural context.

Casino gambling and Chinese migrants

Commercial gambling, including casinos, is commonplace in many western countries. The strategy of targeted ethnic marketing to attract Chinese customers to casinos is well known and widely practised (Dyall et al., Citation2009; Keovisai & Kim, Citation2019). Common strategies include offering free bus rides, cheap buffets, gambling coupons, employing Chinese-speaking dealers, and building casinos near Chinese communities (Chen & Dong, Citation2015; Lai, Citation2006; Wong & Li, Citation2019). Cultural symbols have also been employed by casinos to target vulnerable populations. In New Zealand, casinos have applied ethnic and indigenous cultural icons such as large-scale Māori (indigenous New Zealanders) carvings at entry points and at Chinese New Year festival displaying the image of a dragon dance to create a sense of familiarity which will lure people into the venues (Dyall et al., Citation2009). Similarly, in the US and Canada, casinos regularly put advertisements in media targeted at specific ethnicities and offer games like Pai Gow or Sic Bo which are familiar to Chinese and other Asian players (Kim, Citation2012).

Chinese are overly represented in casino gambling globally and, accordingly, Chinese gambling has generated considerable attention in gambling research (Bell & Lyall, Citation2002; Chen & Dong, Citation2015). Research on the impacts of gambling on Asian populations has identified how the high availability and accessibility of legalized commercial casinos provide an attractive social environment that encourages new migrants to engage in casino gambling (Lai, Citation2006; Sobrun-Maharaj et al., Citation2013). The motivations for Asian migrants to gamble have been identified as a way of improving their ability to cope with stress, language barriers, unemployment, and isolation; all factors associated with immigration and post-immigration adjustment (Li et al., Citation2014; Tse et al., Citation2012).

The meaning of gambling varies across cultures and this, in turn, affects when and how gambling is incorporated into daily life. In Chinese discourse, gambling is understood in its negative meaning, equivalent to problem gambling in English (Wong & Li, Citation2019). An investigation involving older Chinese migrants indicated that participants differentiated playing, from gambling, and they equated gambling to problem gambling (Keovisai & Kim, Citation2019). For Chinese, gambling is inconsistent with traditional Chinese philosophies, such as Confucianism and Daoism, which emphasize harmony (hexie 和谐) between people, among people and with the natural environment. Chinese culture promotes what is referred to as natural life – a life that follows a natural order in society and nature, and in a way that avoid extravagance and excess (Chan, Citation1963). Several studies have examined cultural influences on Chinese people’s engagement with problem gambling (Oei & Raylu, Citation2010; Tse et al., Citation2010). However, for much of this research the emphasis is on what is going wrong and, in the process, gravitates toward pathology-oriented explanations. Studies considering how cultural values guide Chinese responses to gambling harm are rare (Zhang et al., Citation2022).

Methods

The study applied an interpretive phenomenological approach that can be described as ‘a method of abstemious reflection on the basic structures of the lived experience of human existence’ (van Manen, Citation2014, p. 26). Phenomenology has its focus on a person’s lived experience. Prejudices (or one’s preconceptions that make understanding possible) have a special importance in interpretation (Gadamer, Citation1976). van Manen (Citation2014) developed a framework for phenomenological inquiry, which was employed as an instrumental guide to this study.

We adopted an interpretive phenomenological approach because we saw it as appropriate for examining the meanings and responses to gambling harm by Chinese people who have lived experience of the phenomenon. In line with the goals of phenomenological research, a criterion purposeful sampling method was used to select information-rich participants who had experience with the topic under study (Creswell & Poth, Citation2018). Criterion purposeful sampling is used when pre-established criteria are introduced that defines the selection of a particular sample. The inclusion criteria were Chinese individuals, aged 20 or over, who self-identified as having experienced problem gambling and have stopped for over three months (Gambler, G), and associated affected family members (AFM) who agreed to be interviewed. Sixteen participants from eight families were recruited through local gambling treatment agencies and Chinese communities. Participants came from a range of backgrounds in terms of age, gender, social-economic situation, length of problem gambling, and length of recovery. The AFMs were nominated by gamblers and contacted separately to ensure their voluntary participation. A total of 10 families were approached out of which 2 declined. Two resources were employed for recruitment to ensure participants included both service users and non-service users. Five families were recruited from a problem gambling service specializing in ethnic communities, and 3 families were recruited through advertisements displayed in family doctor clinics, in community group rooms and on social media.

The data collection method involved two semi-structured in-depth interviews to generate a co-constructed account of families’ realities (Reczek, Citation2014). The self-identified individual who gambled problematically and associated affected family member were interviewed together. Pseudonyms were used to preserve anonymity. Literature on joint interviewing were consulted as several ethical dilemmas emanated from this method of data collection. Associated ethical issues were addressed in an ethics application that included measures to ensure a safe environment during joint interviews and ways of fostering equal and neutral but dedicated attention to all parties, before, during and after the joint interviews (Voltelen et al., Citation2018). Ethical approval was granted by the University of Auckland Ethics Committee.

All interviews were conducted in Mandarin apart from one family who were interviewed in English as they preferred. The first interview explored the details of the experiential events, the second interview sought to further develop an interpretation from the empirical data. The first interviews were guided by two overarching interview questions: ‘How did you engage in casino gambling? What happened next?’ An anecdote was developed from the transcript and returned to the interviewee for checking. The second interview focused on the anecdote developed from the first interview. Questions included: ‘Can you talk more about that event?’ and ‘What has influenced your behaviour?’.

Data analysis was based on the texts generated from the interviews and comprised a comprehensive thematic analysis. Thematic analysis is commonly used in interpretive phenomenology as a way of shedding light on every day, taken-for-granted thinking (K. H. Ho et al., Citation2017). The data analysis involved three main steps (Crowther et al., Citation2017): 1) crafting anecdotes to determine the meaning of a story (from each text) and returning the anecdotes to interviewees before the second interview; 2) repeatedly reading the text generated from both interviews (integrating notes and memos) and identifying initial themes through manual coding of transcripts (across texts); 3) generating major themes, including integrating the researcher’s interpretations; and developing a model (a visual image). Four major themes were generated from 18 sub-themes. Initial data analysis was conducted in English. The one transcript from the interview conducted in English was translated into Chinese for analysis after approval from the participants. The quotations from all interviews used in dissemination were translated into English with use of Chinese expressions as appropriate. All translated documents were checked by two academics who are fluent Chinese and English speakers to ensure that the depth of meaning was retained. Trustworthiness was ensured using peers for checking translations and meaning. The model was sent to participants and two families provided feedback which were integrated into the final version. Field notes were taken to record the interviewer’s observations and contextual information. This supplemented the research data and supported purposeful reflection.

Results

Participants shared how Chinese migrants’ responses to casino gambling involves a long, rocky, and transformative journey. Collectively, the four major themes that resulted from the data led to the development of a process model of Chinese migrants responding to gambling harm. illustrates this model.

Misconnecting with casino gambling

Participants indicated that pathways into excessive gambling (conceptualized as ‘misconnection’) were two-pronged: their migration experiences and the gambling environment.

The first part of the model (the left of the diagram), shows participants’ experiences of misconnecting to casino gambling. This includes four components: losing connections, engaging with casino gambling, intensifying gambling and the consequent deteriorating relationships. Participants recalled that, as migrants, they left their countries and familiar environments to explore a new world and a different but better lifestyle. They lost many connections during the process of migration and felt they needed to replace these connections in the host country.

Huang Jie, Gambler (G), Male (M), aged 30, came to New Zealand as a student but felt unprepared for the isolation and loneliness he experienced. He linked his gambling with his living environment in his new country. He recollected:

Compared to my hometown, the weather was freezing at night. I was very lonely and didn’t know what to do. There were many bars in the city, and you could see the jackpot sign outside the bars everywhere. It was too cold to stay home, so I started going to the bars to play tiger machines.

Disconnected from his original living environment, Huang Jie was looking for a place where he could be surrounded by other human beings. That place addressed only his physical need for warmth; his psychological needs were less secure.

For some participants, casinos became a place for socializing because the location is easy to access, always available, with Chinese commonly spoken and, over time faces become familiar. Wang Kai (G, M, 70), a retired civil servant, recollected: ‘I used to have a social circle […]. To build a new life here is very tough. I only went [to the casino] for socializing.’ Wu Ming, (G, M, 70+), a restaurant worker, commented ‘I cannot speak English and go to the casino with my workmates after work. Apart from going to the casino where else could you enjoy fun in New Zealand (在新西兰除了赌场还有哪里好玩)?’ For participants like Wang Kai and Wu Ming, engaging (misconnecting) with casino gambling was a way of making up for lost connections and became a way to cope with psychological pain. They did this without a strong awareness of the addictive features of casino gambling.

Chen Xin (G, M, 50+), a skilled migrant, shared his experiences and observations of casino gambling:

Let me tell you, although casino [promoters] say, ‘if you have $100, only spend $10 on gambling.’ But, when I sit and play with the cards, nothing could stop me, until all the money has gone. Nothing [activities in the casino] is for playing. Of course, now I know that is addiction. I was not in control of myself. The casino controlled me.

Casinos in New Zealand are legal and are promoted as entertainment. Chen Xin’s statement suggests he was naïve to the addictive potential of casino games and accepted casinos’ promotional messages without question.

Several participants highlighted that their problematic gambling was related to the design and operation of casinos. Dai Jun (G, M, 50), a businessman, shared this insightful reflection:

I was invited to play in the VIP room. In there, you felt ‘I am a really important person.’ Everything was arranged for you to make sure you stayed there for longer and bet more money. The system leads you quickly to overdraft all your financial resources. I lost all my family savings and accumulated over $1 million of debt in a year.

Dai Jun’s story revealed that becoming a casino VIP member accelerated his gambling problem. His exposure to more salient forms of gambling placed him more at risk.

Several participants described how their intensified relationship with casino gambling impacted on their personal and family well-being, including family conflict, financial hardship or gambling debts, poor mental health, and child neglect. The impact on their well-being has further separated them from the resources needed for settling into their host country including social connections, business opportunities and familiarization with local services (Li & Chong, Citation2012). This finding supports the social-ecology model of addiction that, once people’s relationship with addiction intensifies, their relationship with others in their lives deteriorates (Adams, Citation2008).

Disconnecting from casino gambling

The second part of the model (arrows at the bottom of the diagram), acknowledges the way participants described their struggle to control their gambling and the importance of family members’ understanding and support. Participants recalled that they had tried many ways to stop gambling. A common way (reported by 7/8 gambling participants) was to seek to be excluded from the casino through an ‘exclusion order.’ Chen Xin had gambled problematically in casinos for over 15 years. He had been excluded repeatedly following the urging of family members or friends: ‘I have self-excluded at least four times. Of course, that was not [voluntary].’

Yang Hai (AFM, M, 30), shared how it is vital for gamblers to leave the casino to stop gambling. After he saw how his mother, Hou Lian (G, Female, 50+), presented as a totally different person in the casino, he applied for an exclusion order to be placed on her. He stated, ‘I wanted to show her that someone is caring for her.’ He emphasized the importance for family members to take action:

Family members needed to be informed that they have the authority to act [ban a gambler from the casino], because gamblers may not want to ban themselves. If family members know what to do in preventing them from gambling harm, it can be effective.

Although the casino self-exclusion programmes have been adopted as a harm-minimization tool, many participants experienced disappointment with them. After being excluded from the casino, Hou Lian gambled in another casino in a nearby city that belonged to the same company. She gambled there undetected and continued to gamble overnight before casino staff checked her ID.

Participants’ descriptions of struggles to stop casino gambling support Orford’s (Citation2020) argument that making use of exclusion orders to quit gambling is a clear signal that casino gambling is addictive. The reasons for returning to casino gambling identified in this study related to the availability of gambling opportunities and the lack of meaningful connections in life.

Reconnecting to natural life

Disconnecting from casino gambling is a necessary step to getting away from gambling harm – but is not sufficient. Reconnecting to ‘natural life’ (ziranshenghuo 自然生活) is crucial in maintaining a life free from gambling harm. Chinese migrants spoke of benefitting from settling into a new environment (conceptualized as ‘reconnection’). The third part of the diagram (the right), details how participants effectively reconnected to a reinvigorated world they described as ‘natural life’ (ziranshenghuo 自然生活) (top of the diagram), which was a crucial task, requiring a whole family effort.

The journey starts with ‘breaking-away’ (tuoli 脱离) that involves leaving the gambling venues (in this case the casino), through three phases as a pathway to reconnecting to natural life: wake-up (xingwu 醒悟), face-up (miandui 面对) and climb-up (pandeng 攀登). Participants described how this involves a repetitive journey requiring the collective effort of both gamblers and family members and the support of the wider community, of society and of government agencies.

Participants referred to breaking-away (tuoli 脱离), or leaving casinos, as the starting point in their process of disconnecting from gambling harm. Several spoke of having temporary breaks from gambling before they reached a point where they could sustain their absence from the casino. Dai Jun gambled in the casino for less than two years and accumulated about $1 million gambling-related debts. During the interview, he repeatedly emphasized that stopping was the most important thing.

When I think about it [gambling in casinos] now, I felt how important it was to stop at that time. Stop first! Then you will calm down, calm down, and think of other solutions.

However, to stop gambling may require assistance from external forces. A break-away from casinos opened the pathway and the opportunity to reconnect with other areas in life.

Participants described wake-up (xingwu 醒悟), as the way gamblers recognized the dangers of casino gambling and formed an appreciation of family. Yu Gang (G, M, 30+) recalled how he reduced his gambling once he got married: ‘Family is significant to me, and hence I am more able to control my gambling. Gambling is not an important thing.’ Li Hong (AFM, F 50+), Wang Kai’s wife, recalled the way her husband finally stopped casino gambling ‘after he lost $20,000 NZD of our daughter’s money at one session [of gambling]’ and commented ‘that was out of his own conscience (是他自己的良心发现).’ Once Wang Kai recognized his gambling violated his responsibility as a father, he was able to stop casino gambling ‘This [gambling] is only my hobby, it should not harm the family and children. That is irresponsible, and I would feel guilty [自己心里过不去].’ The awareness of the importance of family served as a wake-up call and reflected the collective-oriented Chinese cultural values (Leung, Citation2009).

Participants reported that a better understanding of how casinos functions helped them to stay away. For some, gambling was like a spiritual opium (赌博是精神鸦片) and others realized that ‘controlled gambling’ was only a myth of the casino (赌博自制在赌场只是一个迷思). They also commented on their realization that there is ‘no free enjoyment’ (没有白享受的), and that the casino had some ‘horrible features’ (可恶的面目). The recognition of these features of gambling also served as a wake-up call.

The face-up phase (miandui 面对) is where participants dealt with the consequence of their gambling. Many participants expressed their emotional vulnerability in this phase and shared feelings of hopelessness, helplessness, shame, and guilt because their behavior had caused harm to their families. Some commented on the need to avoid ‘burying one’s head in the sand’ (不能有鸵鸟心态). Xia Hua (G, F, 50+) described how a positive attitude helped her in this phase: ‘I had lost so much [money, relationship with children] after gambling for over 20 years. Well, what ought to be lost had been lost. Let’s now follow the natural order [该失去的已经失去, 那就顺其自然吧].’ Many affected family members spoke of feeling anger, resentment, and distress. They commented how this was the hardest step in their journey because it could either move them forward to natural life (ziranshenghuo自然生活) or, for some, lead to a relapse. Luo Yan (AFM, F, 30), Yu Gang’s wife, explained how attempts to reconnect to natural life was fragile in the following extract:

I could not sleep while I had those images [of lapsing back into gambling] appear in my mind, and even wondered do we still want to stay together as a family (jia hai guo ma 家还过吗)? It seemed like a hidden bomb that would explode anytime.

Some participants described this phase as crucial for the whole family and required accepting and supporting each other. Jiang An (AFM, F, 40+), Dai Jun’s wife, shared how she felt when faced with the family chaos brought on by gambling. “I had thought of complaining [maiyuan 埋怨] to him [her husband], but that was unhelpful.

I went out to look for jobs to show him that we still have hope.” To prevent families from gambling harm, any small improvement can enhance hope and confidence.

The climb-up (pandeng 攀登) phase involves committing to a new direction. Participants described how committing at the climb-up phase involved affirming their decision to change, as stated by Chen Xin:

The last 3 years, my family life was getting normal and getting better. The most important thing is that I have a plan for next year. If I went to the casino again, everything would become zero. I am afraid of that.

Having a plan instilled hope and enhanced the determination for Chen Xin to maintain a gambling-free lifestyle. Huang Jie shared his experience of moving toward a natural life by engaging in alternative activities: ‘Now, I like fishing on a boat. After having a baby, I look after the baby.’ There is no point, in Huang Jie’s life, in maintaining connections with the casino once new interests develop and a new life unfolds. Looking after their new-born baby had further strengthened his relationship with his wife. Miao Li (AFM, F, 30), Huang Jie’s wife, commented: ‘Now, [when he wanted to go out] he would ask me first. He has greatly reduced the frequency and has much better control [of gambling].’ Miao Li depicted them in a harmonious relationship and showing respect for each other. Gambling had no place in such a family.

The participants’ experiences echoed the theoretical model of gambling recovery; that recovery from problem gambling does not only require absence from gambling but also improved quality in other areas of life (Pickering et al., Citation2021).

Natural life (Ziranshenghuo自然生活)

The top part of the diagram () depicts the core elements of natural life (ziranshenghuo自然生活) and influential aspects of rebuilding natural life. Natural life embraces the features of balance (pingheng平衡), harmony (hexie和谐), and interdependence (xianghuyicun相互依存).

A balanced (pingheng 平衡) lifestyle is consistent with Confucian teaching of Zhongyong (中庸), which means not too much and not too little in everyday living. Most participants emphasized that there is no place for casino gambling in their natural life. Chinese culture endorses a lifestyle that discards the excessive, the extravagant, and the extreme, and advocates for maintaining the harmony of the family, of human beings, and of the natural environment. A balanced lifestyle is the opposite of an addictive lifestyle. Lu Ying (AFM, F, 20+), Xia Hua’s daughter, emphasizes the importance of maintaining an enjoyable and natural lifestyle: ‘I was very happy every time I collected the vegetables from my mother, [shared them with] my friends [and they] were also very happy.’ Lu Ying’s description

Participants expressed satisfaction with their current life and valued the peace and harmony (hexie 和谐) it offered. Family relationships were strengthened and they enjoyed harmonious relationships. Some spoke about having achieved better family life and considered the effort to stop gambling as meaningful.

Natural life involves a situation in which family members support each other in ways that align with Confucius’s notion of human relationships as interdependent (xianghuyicun相互依存). Many participants highlighted that receiving support from family and social networks is a natural practice among Chinese people. For some new migrants, family support is not always available, and, accordingly, friends and community networks are needed in providing wake-up calls for people who gambled problematically. Wu Rong (AFM, F, 30+), Wu Ming’s daughter, expressed a need for social support for her father: ‘I am working and can only take him for yum-cha (yincha 饮茶, a Chinese style lunch) at the weekends. It is better to introduce him to an agency so he can attend some other activities.’ This finding is consistent with a previous study that found community functions as a natural support for gamblers and affected family members and highlighted the need for this to be strengthened (Best et al., Citation2017).

Influential Aspects

Family relationships

Family members are the most affected by the negative consequences of gambling and in the unique position of observing the early signs of a person’s problematic relationship with gambling. Several family members described how they played active roles in responding to gambling harm. They described ‘working together’ and ‘never giving up’ as key to achieving this goal. Chen Mei offered her insight for children whose lives had been impacted by family members’ gambling: ‘ … don’t let your family situation define you because you are a different person in your own right. Like everything is up to you, only you can change.’ Even though Chen Mei experienced a miserable life during her childhood, she became a university student and looked forward to a bright future.

Societal relationships

The establishment of local Chinese communities in Auckland has provided a platform for Chinese migrants to share their happiness and sadness and to care for each other. Such community resources provide better opportunities for Chinese migrants to reconnect with natural life. Several participants shared that group counseling or peer-support groups provided them with positive support. Xia Hua had cut her relationships with family in China because she did not want her family worrying about her. Peer support replaced her social relationships: ‘[Counseling] has helped me a lot. At least it provided a place to share your troubles and experiences of gambling. You felt relieved. Whenever I was stuck, especially when my gambling problem got more serious, I hoped for a person who could pull me out of the deep mud (拉我一把) . … I trust [peer support] could pull me out.’

Chinese culture

Participants highlighted how traditional Chinese values, beliefs and culture have influenced their way of responding to gambling harm. Li Hong commented on her husband’s commitment to quit gambling as his discovery of conscience (liangxin faxian良心发现): his change ‘was out of his own conscience’ (是他自己的良心发现) and he ‘would feel guilt’ (自己心里过不去) if he continued to gamble. Her comments suggest that discovery of conscience is an important motivation in stopping gambling. As Leung (Citation2009) asserts, it serves as one’s wake-up (xingwu 醒悟) call. The Chinese emphasis on collective identity was linked to participants’ awareness of the family as important, and this contributed to preventing personal interests from harming family well-being. The Chinese proverb reflects the value of collective identity: ‘no eggs can remain unbroken when the nest is upset’ (倾巢之下, 安有完卵).

Gambling policy

Recognition of the dangerous features of casino gambling enhanced participants’ commitment to stop their gambling. Participants shared how they learnt about the ways casino gambling influenced their gambling behavior. The casino exclusion policy was the most common tool utilized by participants, but its effectiveness was challenged. The disappointment participants had regarding such policies was that the casinos did not take these programmes seriously. Hou Lian could bet money in a casino despite being excluded: ‘I played overnight until I was the only one in the casino. The venue supervisor knew me and only then checked my ID and asked me to leave the venue’. The effectiveness of casino regulations, including exclusion policies, needs to be evaluated in order to help Chinese communities take a proactive approach to gambling harm. Findings from this study support the suggestion from previous research that third-party exclusion options (including early identification by venue staff) need to be improved, entry checks for exclusion need to be taken seriously and the effectiveness of centralized exclusion systems need to be regularly monitored by state agencies (Hayer et al., Citation2020; Pickering et al., Citation2018).

Discussion

The dislocation theory of addiction offers a helpful explanation for why migrants are more vulnerable to having a problematic relationship with gambling. According to B. Alexander (Citation2010), to live in a society, a person must connect with supportive and meaningful relationships. For many migrants, various aspects of their lives have been disconnected from their usual supports. Misconnecting with casino gambling – i.e. casino connecting instead of connecting socially – created the impression that a casino could temporarily meet their psychological needs. The vulnerability of migrants to gambling harm has been reported in previous studies on Asian migrants’ gambling (Sobrun-Maharaj et al., Citation2013; Tse et al., Citation2012).

Viewing addiction as a relationship issue enhances understandings of Chinese migrants’ experiences of responding to gambling harm. The theory emphasizes that reintegration is seen as a social process; the focus is not on one individual but on multiple people across several social layers (Adams, Citation2008). The process of reconnecting to natural life (ziranshenghuo 自然生活) described in this study and broken down into the phases of wake-up (xingwu 醒悟), face-up (miandui 面对) and climb-up (pandeng 攀登), is similar to the phases of reintegration Adams (Citation2008) identified in his application of social-ecological theory to addiction – that identified ‘collective action,’ ‘crisis,’ ‘reappraisal,’ ‘reformation,’ ‘renegotiation’ and ‘consolidation’ as key parts of the process. Participants stated that building a natural life cannot be achieved by individual action but requires collective effort. The findings of this study encourage future gambling studies to shift the gaze from personal perspectives to explore the role of social connections in the addictive system.

Natural life (ziran shenghuo 自然生活) means to live with nature. In Daoism, ziran does not mean the natural world; it is the dao (道) of the universe, the principle of the universe operating (Yu, Citation2008). In Daoism, the ideal way of living is to follow ziran. Similar to the Chinese living principles, several participants emphasized that connecting to natural life does not mean simply returning to their old lifestyle, but is a living practice that requires them to accept what has happened and a willingness to start a new journey. As Xia Hua stated: ‘Let’s follow the natural order [那就顺其自然吧].’ The participants’ stories illustrated that to pursue a natural life in the host country, new migrants needed to expend extra effort over a long period of time. The participants shared that the stronger they reconnected to natural life, the less likely they were to return to gambling.

The process model developed from this study adds qualitative evidence to our understanding of gambling harm and contributes to the three trends in gambling studies discussed earlier. In doing so, it illustrates that a focus on gambling harm needs to widen beyond the individual to be seen as a phenomenon within a social world.

A comparison of the concepts of recovery capital and natural life can be useful to determine how the Chinese concept of recovery can contribute to the theory of recovery in the field of addiction, including gambling. Recovery capital provides a holistic model of recovery that considers the socio-cultural context in which gambling is occurring that includes both recovering individuals’ perceptions and experiences and shifts away from a pathology-oriented model of addiction. However, recovery capital, including social networks, cultural influences, human attributions, and financial resources, still focus primarily on individual-level recovery. An extended view of recovery to include resources beyond the individual is worth considering (Zschau et al., Citation2016). This conceptual model relates to community and social recovery domains that are necessary throughout the recovery process. The notion of natural life as a Chinese concept of recovery has its roots in Chinese Daoist philosophy that proposes an ideal life is living with zira. In Daoism ziran does not mean the natural world but refers to the most fundamental operational principle of the natural world. For Daoism, living with nature is a matter of restoring our original spontaneous aptitude (Yu, Citation2008). Natural life is a lifestyle that means that one is not disturbed by desires and is indifferent toward external events. The present study enriches the concept of recovery capital by showing how social, community and human resources are manifested in Chinese immigrants.

Conclusion

The study reported in this article provides insights into the intersection between casino gambling for Chinese migrants, Chinese culture, and the host country’s gambling environments. The process model developed from this study provides a visual tool to understanding both how Chinese migrants get involved in casino gambling and how they might respond in reducing gambling harm. Such descriptions have not been identified in previous Chinese gambling-related studies. Accordingly, this process model contributes to gambling literature in ways that extend debates from the narrow focus on relapse prevention to ways of minimizing gambling harm in a broad social, cultural, and historical life cycle. This model also encourages policy makers and clinicians to consider the impacts of migration and post-migration experiences, as well as the gambling environments that new migrants face, and to use these understandings to develop more effective approaches to gambling harm. Exploring the meaning of natural life in Chinese culture can be incorporated into approaches used in gambling treatment programs in ways that help such programs extend beyond simple relapse prevention and toward approaches that use social and cultural processes in the task of building new and gambling-free lifestyles. The notion of natural life and the identification of Chinese cultural influences on Chinese migrants’ approaches to gambling harm could be extended in future studies of addiction.

Limitations

This research studied Chinese migrants’ lived experience of responding to gambling harm in New Zealand. It may not be representative of Chinese migrants’ gambling issues in other Western countries, but we consider some of the findings transferrable. This study was furthermore mainly from a Chinese cultural perspective. It does not claim to consider cultural differences applied to other ethnic groups, although there may be some similarities with experiences in other cultural contexts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

W. Zhang

Wenli Zhang has extensive practice experience as counsellor and social worker in gambling addiction and mental health education. She completed her doctoral studies on Chinese migrants’ lived experiences of responding to gambling harm.

C. B. Fouché

Christa B. Fouche is a Professor in the School of Counselling, Human Services and Social Work. She is an applied researcher with research expertise in community health, child migrant health and transnational workforce dynamics.

P. J. Adams

Peter J. Adams is a Professor in the School of Population. He has teaching expertise in alcohol and drug studies, mental health and health promotion and research expertise in Asian health, addictive behaviour, gambling and community development.

References

- Abbott, M. W., & Volberg, R. A. (2000). Taking the pulse on gambling and problem gambling in New Zealand: A report on phase one of the 1999 national prevalence survey. Department of Internal Affairs.

- Adams, P. J. (2007). Gambling, freedom and democracy (Vol. 53). Routledge.

- Adams, P. J. (2008). Fragmented intimacy: Addiction in a social world. Springer Science & Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-72661-8

- Adams, P. J. (2009). Redefining the gambling problem: The production and consumption of gambling profits. Gambling Research: Journal of the National Association for Gambling Studies (Australia), 21(1), 51–54. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.185982353932249

- Adams, P. J. (2016). Switching to a social approach to addiction: Implications for theory and practice. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 14(1), 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-015-9588-4

- Alexander, B. (2010). The globalization of addiction: A study in poverty of the spirit. Oxford University Press.

- Alexander, B. K. (2012). Addiction: The urgent need for a paradigm shift. Substance Use & Misuse, 47(13–14), 1475–1482. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2012.705681

- Bell, C., & Lyall, J. (2002). One night out gambling. In B. Curtis (Ed.), Gambling in New Zealand (pp. 231–244). Dunmore Press.

- Best, D., Beckwith, M., Haslam, C., Alexander Haslam, S., Jetten, J., Mawson, E., & Lubman, D. I. (2016). Overcoming alcohol and other drug addiction as a process of social identity transition: The social identity model of recovery (SIMOR). Addiction Research & Theory, 24(2), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2015.1075980

- Best, D., Irving, J., Collinson, B., Andersson, C., & Edwards, M. (2017). Recovery networks and community connections: Identifying connection needs and community linkage opportunities in early recovery populations. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 35(1), 2–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347324.2016.1256718

- Blaszczynski, A., & Nower, L. (2002). A pathways model of problem and pathological gambling. Addiction, 97(5), 487–499. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00015.x

- Chan, W. T. (1963). The way of Lao Tzu: Tao-te ching. Bobbs-Merrill.

- Chen, R., & Dong, X. (2015). The prevalence and correlates of gambling participation among community-dwelling Chinese older adults in the US. AIMS Medical Science, 2(2), 90–103. https://doi.org/10.3934/medsci.2015.2.90

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE.

- Crowther, S., Ironside, P., Spence, D., & Smythe, L. (2017). Crafting stories in hermeneutic phenomenology research: A methodological device. Qualitative Health Research, 27(6), 826–835. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316656161

- Dyall, L., Tse, S., & Kingi, A. (2009). Cultural icons and marketing of gambling. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 7(1), 84–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-007-9145-x

- Fisher, S. (2000). Measuring the prevalence of sector-specific problem gambling: A study of casino patrons. Journal of Gambling Studies, 16(1), 25–51. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009479300400

- Gadamer, H. G. (1976). Philosophical hermeneutics. University of California Press.

- Gavriel-Fried, B., & Lev-el, N. (2020). Mapping and conceptualizing recovery capital of recovered gamblers. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 90(1), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000382

- Granfield, R., & Cloud, W. (2001). Social context and “natural recovery”: The role of social capital in the resolution of drug-associated problems. Substance Use & Misuse, 36(11), 1543–1570. https://doi.org/10.1081/JA-100106963

- Hayer, T., Brosowski, T., & Meyer, G. (2020). Multi-venue exclusion program and early detection of problem gamblers: What works and what does not? International Gambling Studies, 20(3), 556–578. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2020.1766096

- Ho, K. H., Chiang, V. C., & Leung, D. (2017). Hermeneutic phenomenological analysis: The “possibility” beyond “actuality” in thematic analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(7), 1757–1766. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13255

- Keovisai, M., & Kim, W. (2019). “It’s not officially gambling”: Gambling perceptions and behaviors among older Chinese immigrants. Journal of Gambling Studies, 35(4), 1317–1330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-019-09841-4

- Kim, W. (2012). Acculturation and gambling in Asian Americans: When culture meets availability. International Gambling Studies, 12(1), 69–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2011.616908

- Lai, D. W. (2006). Gambling and the older Chinese in Canada. Journal of Gambling Studies, 22(1), 121–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-005-9006-0

- Langham, E., Thorne, H., Browne, M., Donaldson, P., Rose, J., & Rockloff, M. (2016). Understanding gambling related harm: A proposed definition, conceptual framework, and taxonomy of harms. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2747-0

- Leung, Y. K. (2009). An exploratory study on how male pathological gamblers become non-gamblers in Hong Kong. Chinese University of Hong Kong.

- Li, W., & Chong, M. (2012). Transnationalism, social wellbeing and older Chinese migrants. Graduate Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies, 8(1), 29–44. https://webs-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/ehost/detail/detail?vid=2&sid=f96bf0b1-eb67-4328-aae3-64911988fef5%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZzY29wZT1zaXRl#AN=91559043

- Li, W., Tse, S., & Chong, M. D. (2014). Why Chinese international students gamble: Behavioral decision making and its impact on identity construction. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 12(3), 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-013-9456-z

- Oei, T. P., & Raylu, N. (2010). Gambling behaviours and motivations: A cross-cultural study of Chinese and Caucasians in Australia. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 56(1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764008095692

- Orford, J. (2020). The gambling establishment: Challenging the power of the modern gambling industry and its allies. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367085711

- Pickering, D., Blaszczynski, A., & Gainsbury, S. (2021). Development and psychometric evaluation of the recovery index for gambling disorder (RIGD). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 35(4), 472–485. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000676

- Pickering, D., Blaszczynski, A., & Gainsbury, S. M. (2018). Multivenue self-exclusion for gambling disorders: A retrospective process investigation. Journal of Gambling Issues, 38(38), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2018.38.7

- Reczek, C. (2014). Conducting a multi-family member interview study. Family Process, 53(2), 318–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12060

- Schüll, N. D. (2012). Addiction by design: Machine gambling in Las Vegas. Princeton University Press.

- Sobrun-Maharaj, A., Rossen, F. V., & Wong, A. S. (2013). Negative impacts of gambling on Asian families and communities in New Zealand. Asian Journal of Gambling Issues and Public Health, 3(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2195-3007-3-14

- Tse, S., Dyall, L., Clarke, D., Abbott, M., Townsend, S., & Kingi, P. (2012). Why people gamble: A qualitative study of four New Zealand ethnic groups. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 10(6), 849–861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-012-9380-7

- Tse, S., Yu, A. C., Rossen, F., & Wang, C. W. (2010). Examination of Chinese gambling problems through a socio-historical-cultural perspective. Scientific World Journal, 10, 1694–1704. https://doi.org/10.1100/tsw.2010.167

- van Manen, M. (2014). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing. Left Coast Press.

- Voltelen, B., Konradsen, H., & Stergaard, B. (2018). Ethical considerations when conducting joint interviews with close relatives or family: An integrative review. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 32(2), 515–526. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12535

- White, W. L. (2007). Addiction recovery: Its definition and conceptual boundaries. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 33(3), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2007.04.015

- Wong, C., & Li, G. (2019). Talking about casino gambling: Community voices from Boston Chinatown. Massachusetts gaming commission. https://massgaming.com/research/talking-about-casino-gambling-community-voices-fromboston-chinatown/

- Yu, J. (2008). Living with nature: Stoicism and Daoism. History of Philosophy Quarterly, 25(1), 1–19. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27745110

- Zhang, W. (2021) Reconnecting to natural life: Chinese migrants’ lived experiences of responding to gambling harm. Unpublished PhD thesis, The University of Auckland

- Zhang, W., Fouché, C., & Adams, P. J. (2022). Chinese migrants’ experiences of responding to gambling harm in Aotearoa New Zealand. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 34(2), 16–29. https://web-p-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=2&sid=18aa583c-1f37-4979-9410-676feebefcd9%40redis

- Zhang, W., & Hans, E. (2012). Interactive Drawing Therapy and Chinese Migrants with Gambling Problems. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 10(6), 902–910. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-012-9385-2

- Zschau, T., Collins, C., Lee, H., & Hatch, D. L. (2016). The Hidden Challenge: Limited Recovery Capital of Drug Court Participants’ Support Networks. Journal of Applied Social Science, 10(1), 22–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1936724415589633