ABSTRACT

Aboriginal participatory action research (APAR) has an ethical focus that corrects the imbalances of colonisation through participation and shared decision-making to position people, place, and intention at the centre of research. APAR supports researchers to respond to the community's local rhythms and culture. APAR supports researchers to respond to the community's local rhythms and culture. First Nations scholars and their allies do this in a way that decolonises mainstream approaches in research to disrupt its cherished ideals and endeavours. How these knowledges are co-created and translated is also critically scrutinised. We are a team of intercultural researchers working with community and mainstream health service providers to improve service access, responsiveness, and Aboriginal client outcomes. Our article begins with an overview of the APAR literature and pays homage to the decolonising scholarship that champions Aboriginal ways of knowing, being, and doing. We present a research program where Aboriginal Elders, as cultural guides, hold the research through storying and cultural experiences that have deepened relationships between services and the local Aboriginal community. We conclude with implications of a community-led engagement framework underpinned by a relational methodology that reflects the nuances of knowledge translation through a co-creation of new knowledge and knowledge exchange.

Introduction: circling back to the beginning

See us as your cultural carpenters; we'll help shape you for this work. By the end, you won't know yourselves! (Wright et al., Citation2016, p. 93)

The Looking Forward research program is a series of Aboriginal-led, participatory action research (APAR) projects spanning a decade aimed at increasing access to and the responsiveness of mainstream mental health and drug and alcohol support services for Aboriginal families living in Western Australia (Wright et al., Citation2015, Citation2019, Citation2021). Mainstream health systems rarely reflect values, knowledge systems, and care practices that align with Aboriginal worldviews. A key outcome of the research is the development and implementation of a culturally secure system to change the framework for service delivery which enhances the skills of the health workforce. This is achieved by bringing them together with Elders to learn more about Aboriginal culture and our ways of working (Wright et al., Citation2015). Participants have demonstrated deep insight, maturity and a genuine willingness to work together to address serious mental health concerns, like suicide and self-harm, experienced in our community in Perth, Western Australia (Wright, Citation2014; Wright et al., Citation2013, Citation2013).

Debakarn: slowing down to build confidence, capacity and competence as an interdisciplinary research team

We are an interdisciplinary, intercultural research team led by a senior Nyoongar researcher and guided by Elders and other members of the community. We have different histories and origins that inform how we position ourselves in this work (Wright & O’Connell, Citation2015). We learn together, being open and vulnerable to the possibilities that arise in working alongside community and service providers. Throughout this article, we critically reflect on our way of working. For example, our lead researcher reflected on his level of confidence, to position himself in the work:

The Elders have been my teachers, guides and inspiration. For me, I have always been a confident person, but in the presence of the Elders I can be nervous and my confidence nebulous. As an Aboriginal man, the Elders have ‘grown me up' so I am now more confident about my Aboriginality and as a father, brother and community member. The confidence that has organically emerged is now more considered and a slower form of confidence; Debakarn, Debakarn, Debakarn. (steady, steady, steady)

We do this through our experiential learning, which is expressed through the development of confidence, capacity and competence, all of which are central to understanding and valuing relational aspects of systematic change. Central to this is the building of respectful and sustainable relationships with Elders and others in the community. How this is actualised in different contexts varies, as does the co-design process that follows. However, common to all is the need to debakarn, debakarn and to prioritise the relationships and connections with the Elders. For example, confidence has to be re-grown with each new group as we work towards cultural competence and capacity. This is not an external exercise; for each and every service or group we work with, we also learn and grow in confidence and capacity.

Our writing, as with our research, is not conventional. Our journey with the Elders and service partners has been deeply personal and experiential. Articulating the ‘how' of our research methodology is challenging, for we are embedded and embodied in the research process. It is a ‘lived' process, interwoven through our praxis, and is centrally relational. We tell our stories to illustrate the complexity of our research approach using our reflective notes along with quotes from semi-structured interviews with Elders and service providers participating in our research program. This Nyoongar-led approach is held by meaningful dialogue; story-ed, embodied, immersive, and framed by intercultural experiences that have ultimately deepened relationships between mainstream service providers and the local Nyoongar community. The implications of our methodological approach can reshape the way mainstream services engage with and respond in a culturally secure manner to Aboriginal families seeking support. It can also explore ways to translate the research findings through the very relationships built along the way. That is, the process itself inherently influences the outcomes and the people who produce these outcomes. To this end we explore the ways in which Indigenous knowledge translation is applied, as reflected in the scholarly works of Smylie, Morton-Ninomiya and others (Jull et al., Citation2018; Morton Ninomiya et al., Citation2020; Smylie et al., Citation2014). These works echo the co-design and participatory nature of conducting health research in partnership with Indigenous and First Nation communities to produce community-led outcomes.

Aboriginal participatory action research

The literature about APAR is shaped by decolonising efforts at the interface between First Nations and western ways of knowing, being, and doing (Dudgeon et al., Citation2020; Henry & Foley, Citation2018; Kovach, Citation2021; Morton Ninomiya et al., Citation2020; Morton Ninomiya & Pollock, Citation2017; Rigney, Citation2017; Smith, Citation2021). Research in Aboriginal communities starts with where the community is at, working collaboratively with – and in response to – rhythms distinct to the local context and prioritising people's needs. Most often, success comes from Aboriginal researchers who know their community, its history, culture, and protocols. Relationships that are developed slowly over time ensure participation is meaningful, purposeful and honest. Without personally meaningful relationships participants are less inclined to get involved or sustain any engagement in research. Consequently, any attempts in knowledge translation are also impacted, for it is through the participants themselves that outcomes are co-created (Jull et al., Citation2018; Morton Ninomiya et al., Citation2020; Morton Ninomiya & Pollock, Citation2017; Smylie et al., Citation2014). So too, relationships held in strong cultural hands, hearts, and minds make research endeavours authentic, lived, and culturally safe. Developing and maintaining authentic collaborations is challenging in colonised contexts where historical, societal, and institutional power imbalances have resulted in unequal distribution of research knowledge and its benefits because of the politics of colonial control (Jull et al., Citation2018; Morton Ninomiya et al., Citation2020; Smylie et al., Citation2014). If we are to counter this to develop new knowledge and new ways of working for research impact, we must privilege Aboriginal and First Nation worldviews.

Trust, in research in a First Nations context, can never be taken as a given and must be established, deepened, and sustained through relationships (Culbong et al., Citation2022; Hansen et al., Citation2020; Rudman et al., Citation2021; Sherriff et al., Citation2019; Snijder et al., Citation2020; Wright et al., Citation2019). The relational approach takes time and needs to be held in a spirit of reciprocity where cultural accountability is attended to continuously throughout the research. Relationships build the trust and respect required to explore and hold the tensions inherent in different worldviews. As an intercultural research team, these tensions are layered and negotiated internally as much as they are with the community. We must relate together if we are to relate meaningfully to our community and be able to reflect on and effectively translate this experience with service providers, as one non-Aboriginal team member reflected:

I continue to question my intentions and ways of working, which fuels my confidence in working together with Aboriginal Elders, community members, and my colleagues. I know that, even if I say or do something that is in some way, however inadvertently, detrimental to these relationships and our work together, the relationship can be mended and maintained if my original intentions were genuine.

Not same, not different: APAR as everyday intercultural praxis

Decolonising research not only grounds PAR in Aboriginal epistemology and drives everyday research practice through reflexivity and conscious (re)positioning. One team member clearly articulated this:

My confidence has grown from realising and respecting the importance and power of collective decision-making, and the time involved in this process. Drawing on this process gives me confidence to know that the right solution to any issue will always be found.

When participants work as co-researchers, they contribute to community-led actions and the deconstruction and reconstruction of the research agenda and arguably the research team. Decolonising research foregrounds First Nations voices and epistemologies and it frames efforts pursued by (and in partnership with) First Nations peoples in reclaiming power, our unique Indigeneity, and ways of working.

A relational research methodology provides the conditions for participants to have confidence in their engagement and hold the tensions respectfully, with trust and patience. The invitation here, is to consider that, it is not the relationships that create the new knowledge; but how to engage and hold the relationships is the new knowledge, as these thoughts from one non-Aboriginal team member illustrated:

I find myself in a constant state of learning and I approach the uncertainty from this perspective. Uncertainty opens up a vast field of possibilities to me and the uncertain is no longer a paralysing fear; rather it becomes an opportunity to keep discovering what is new around me and in myself. Learning allows me to connect, to recognise my own limitations and gaps, and to continue without fear of failing.

Research context: locating the work

Ngulla kaatidj nidja Nyoongar moort, keyen kaadak nidja Nyoongar boodja. We acknowledge the Nyoongar people who are the traditional custodians of the land on which we live and work.

Since the 1820s when the first settlements in Albany and the Swan River were established on Nyoongar boodja, the impact of colonisation has shifted the standpoint of Nyoongar law and customs. Since the beginning of these settlements, the standard practice has been to broadcast the decline of Nyoongar law and culture to the point of extinction (Haebich, Citation2000; Host & Owens, Citation2009; Tilbrook, Citation1983). These practices have been grossly misleading, for they ignore the reality of a vibrant, robust and thriving culture. Indeed, Nyoongar culture and people have not only survived the impacts of colonisation but have prospered and adapted despite the pressures of modernity.

Debakarn Koorliny Wangkiny: a methodology for steadily walking and talking together

Our research approach is framed by a respect for, and privileges, a Nyoongar worldview. Elders are central to this approach as they are custodians of culture. The dominant world-view through which western mechanisms, structures, and value systems are produced and supported recedes to the background, foregrounding instead, Nyoongar knowledge, practices, structures, and value systems, so that they can stand in their own right. Consequently, the creation, exchange, and translation of new knowledges are influenced by the local context, its history, and its culture (Jull et al., Citation2018; Morton Ninomiya et al., Citation2020).

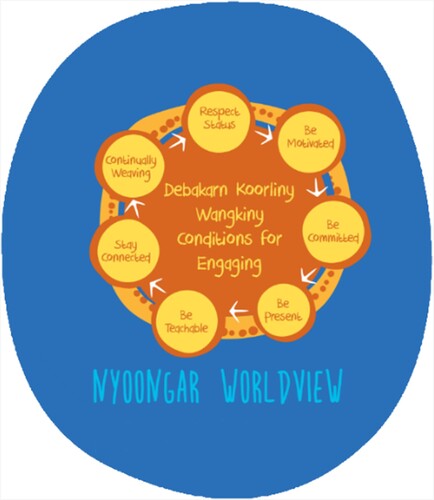

A key outcome of the research was the co-design of an engagement framework, entailing a set of conditions through which Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people could come together in a meaningful way (Wright et al., Citation2015, Citation2021). The framework, known as the Debakarn Koorliny Wangkiny (Steady Walking and Talking) engagement framework, sets out these conditions, which shape and hold the relationships between and with Elders, community, researchers, and participants, for them to develop: (a) inclusivity; (b) trustworthiness; (c) reciprocity; and (d) adaptability (Wright et al., Citation2016). Using the Debakarn Koorliny Wangkiny framework has enabled services and Elders to come together to work collaboratively in a meaningful and effective way to improve service delivery for our people. The seven conditions that direct and support effective engage- ment include: being motivated; being committed; being present; being teachable; staying connected; respecting status; and continually weaving (Wright et al., Citation2021).

The Elders guide predominantly non-Aboriginal service providers to be mindful of their motivations, to engage fully and grow in their commitment to the work and their relationship as it has deepened over time. It has required non-Aboriginal participants to be present and open to learning in a different way, held by the Elders. For the non-Aboriginal participants, it has meant being teachable; that is, to stay open to all emerging possibilities and let solutions arise naturally, unlearning and relearning and being prepared to challenge their own worldview. This means non-Aboriginal participants must respect the status of the Elders to fully commit to being open and willing learners. As the learning and decolonising journey progressed, participants were often confronted by doubts and questions, and were encouraged to stay connected, for it was the experience where the realisations emerged and crystalised. They were reminded neither to give in to the initial anxiety associated with challenging conventional ways of working, nor the uncomfortable vulnerability that arises from revealing more of themselves and being open to the unknown. As staff confidence grew, we witnessed people change through a continual weaving of shared understanding and new knowledge. These are the conditions required for authentic engagement; steadily growing; deepening; talking together; and moving forward – debakarn, koorliny, wangkiny (see ).

Our methodology has deepened over more than ten years, between 2010 and 2022, through the conduct of a series of research projects as part of the Looking Forward program of research (Wright, Citation2014; Wright et al., Citation2013, Citation2015, Citation2016, Citation2019, Citation2021; Wright & O’Connell, Citation2015). Ethical approval was granted for these projects by the Western Australian Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee (WAAHEC), the state-wide entity responsible for overseeing research that has direct engagement and partici- pation of, and benefits Aboriginal people (WAAHEC approvals HRE 262-11/09 (2009), HRE-762 (2017), HRE-772 (2017), HRE-955 (2019)). We engaged and inter-viewed Aboriginal people to establish a baseline view of their experiences of mainstream mental health services. We then engaged mainstream service providers as partners who were committed to work with us and the local Aboriginal community. We conducted a series of face-to-face community forums and face-to-face and online semi-structured interviews with both stakeholder groups during the data collection phase to capture early impressions of their experiences. Findings were corroborated by findings from two surveys conducted as part of a larger service evaluation (Wright et al., Citation2021). As a research team, we were guided by the Elders in our data collection and meaning making through our analysis, upholding the key principle of working Burdiya to Burdiya (the Nyoongar word for Boss). Through the lead researcher, we modelled our approach to service providers and service managers, so that there was a clear understanding of and commitment to working directly with the community at every stage of the research.

A synthesis of our thematic analyses over the ten-year period revealed shared storying, On Country immersion, and ‘working together' co-design approaches to be central to enacting a relational, decolonising methodology that frames the debakarn koorliny wangkiny approach.

Ngulla wangkiny, us talking: shared storying

Put your things away and let's just have a yarn you know. Let's have a yarn about things … that's what we were talking about, just yarn about our cultural ways and how we get things going, how we work, how for them to work with us, you know makes us feel comfortable. (Elder co-researcher, semi-structured interview, 2018).

Shared storying is central to our ways of being and doing. It enables reciprocity and inclusivity and is critical in understanding the depth and closeness of relationships between people and Country. In practical terms, it also serves to connect people over space and time to remember, place, and recall people and events (Wright et al., Citation2019). ‘Our story is not one story. There are shared stories around the invasion and colonisation of our homelands. There are also different strands … within these strands are the stories of our families, communities and nations' (Fejo-King, Citation2015).

Primarily, our aim was for service providers to ‘hear’ more directly about Nyoongar experiences, through Elders' stories, unimpeded by the dominant paradigm - the sanitised and edited colonial story - that still shapes our modern way of life. Shared storying is a powerful process that has enabled Elders and service providers to come together in a safe space where they could better understand their shared histories without judgement. What makes such spaces safe are the moments where people feel seen and heard.

In one storying session, a young Aboriginal co-researcher shared a very personal story. She was very nervous and anxious and when she told her story, she became very emotional. An Elder in the session responded by going to her and supporting her with a hug. Their embrace was more than just reassurance; it was giving validation to her experience, enabling a deeper connection between the Elders and young people and their shared histories and experiences. The Storying space is held by the Elders and in doing so, they provide cultural security and safety for the participants.

The connections that are fostered assist the process of seeing – and importantly, feeling – a way forward, turning the ‘colonizer's gaze’ inward (Fejo-King, Citation2015; Milroy & Revell, Citation2013). Each person introduces themselves by telling a story about who they are and what experiences shaped them into that person. Elders advise participants to ‘Only tell as much as you want’. There is no obligation to disclose more than a person feels comfortable to share with colleagues and Elders. The aim is to get to know individuals as people prior to developing an understanding of them as professionals in the sector and what the organisation itself does. For many, the experience of shared storying has been profound and transformative:

Our entire management team including our CEO, sat in a circle with the Elders for two years and told stories and that put us in a position where we could even think up an idea that they would accept (service executive staff member, semi-structured interview, 2017).

It's a human need and I think this concept of expertise, … the human expertise of their own story and we accompany people with our own expertise alongside their own expertise (service executive staff member, semi-structured interview, 2017).

Often those first good conversations actually have the seeds of everything you want, just about anyway, and everything after that is refinement (service executive staff member, semi-structured interview, 2018).

being able to work alongside an Aboriginal colleague has been profoundly impacting – 99% [of the journey] has been actually having Aboriginal staff and Elders in the building that they [staff] can interact with over a long period of time (service executive staff member, semi-structured interview, 2019).

you’ve got to change the setting. You’ve got to be in their place and with their experience and be open to it (service provider, semi-structured interview, 2019).

Service providers are more open and present in their interactions with the Elders and their heightened curiosity is evident from their respectful questioning and attentive listening. This learning has become the bedrock for their work together:

And Aunty's just saying, ‘Well, I feel safe, I can cry here', which kind of like is a relationship, not a service. That's a big challenge for us because we're a service, you know. We take our work to work and then we leave it at five and go home. … The more you peel it out and begin to get their experience, the more raw it becomes and then you realise you actually need to have the raw conversation (service executive staff member, semi-structured interview, 2018).

Nidja Boodja – here, On Country

As a research team, we have supported the Elders to take service providers to locations of cultural and historical importance – and always with a story to tell. Through immersive On Country activities, such as dance, art, preparing traditional foods, and walks through the bush, participants had an opportunity to experience, firsthand, the deep connection Nyoongar people have with Boodja (Country) and how crucial it is to their identity. All of these experiences are held and shaped by the Elders who know Country as deeply as they know themselves.

These activities were somatically potent, disrupting service providers’ typical ways of working as they moved into a space that was mostly uncomfortable and unfamiliar. They must place their trust in the Elders to hold them (Wright et al., Citation2016; Wright et al., Citation2019). Some participants have settler origins, where others have migrant histories, as do members of the research team. Each has a different On Country experience that reflects or echoes elements of their own country of origin, as one team member explained:

I have found a connection with the On Country experience as it resonates with my experience of living in Peru and with my biological family. The rules of reciprocity also apply in Peruvian culture holding nature and humans together through the practices on the land. During our project work, an Aboriginal On Country event can be a day out in a regional town with an Elder giving us a guided visit of the local museum, and then sharing a bus with us, and stopping at special sites and listening to the Stories told by an Elder. It can also be camping On Country with Elders and family organising the entire event; where we sleep, what we eat and the cultural activities that form the event. Feeding us with damper and kangaroo stew, dancing on top of a significant landmark and yarning around the fire until late at night.

Yakka Danjoo, working together, through co-design

The Elders were very clear at the outset that their involvement was conditional on them working with the leadership in the organisations. The rationale was for the leadership to recognise the Elders’ cultural leadership and demonstrate respect for their status by meeting with them as equals. Respecting status has empowered both the Elders and the organisation leaders to engage effectively thereby, legitimising Nyoongar culture. Service leaders have come to realise that the Nyoongar Elders’ status is necessary and critical to ensuring change is sustainable (Wright et al., Citation2021):

What I know to be true categorically based on my six years' experience is nothing changes [organisational] culture more powerfully than having Elders in the building talking to staff (service executive staff member interview, semi-structured interview, 2018).

We’re all solid. We’ve all got something to contribute. We’ve got experience, we’ve got knowledge, we’ve got expertise in our own right, expertise in our own area. We’re all Nyoongars and that’s what’s going to get this thing going further. I really appreciate what’s happening (Elder co-researcher, semi-structured focus group, 2015).

the big thing is who are the decision makers, can you make a decision based on the information coming out from this group today or do you have to go back to your boss or do you have any authority from the boss to make decisions (Elder co-researcher, semi-structured interview, 2018).

In understanding the nuances of research translation, there comes a clear expectation to co-create new knowledge and to do something meaningful with it, offering skills transfer and building capacity together (Culbong et al., Citation2022; Jull et al., Citation2018; Wright et al., Citation2021). At every step in the co-design process, there are noticeable changes in participants' behaviour. Their language is more inclusive and strengths-based, they are more confident in what and how they share with Aboriginal people. They are less transactional and more authentic and relational.

These factors were recently demonstrated by three co-researchers – an Elder, an Aboriginal young person, and a mental health service manager – who presented together at a state conference about mental health. They shared a clear intention about changing the service to better engage with Aboriginal young people, demonstrating the respect and warmth they had for each other. They supported one another as they presented their views and experiences to conference delegates. That the co-researchers spoke so readily about the relational approach; the Elders’ guidance; the storying that brought them together to build trust; the On Country activities that deepened their learning together; and their heartfelt accounts of young people’s lived experiences; it was evident that the research had a significant impact on them and thus the outcomes they co-created as a result. They embodied and enacted the methodology. They ‘owned' it. The research team did not need to be a part of the presentation for the results spoke for themselves through the co-researchers and their drive for community-led outcomes. Co-design workshops follow cultural protocol, commencing with either an Acknowledgement of Country, or, if there is a local Elder present, a Welcome to Country. Participants are invited to reflect on the traditional Country where the meeting is being held and to hear about the significance of the location. Given the Welcome or Acknowledgement is about cultural protocol, it provides for and allows the group to move into the working space by culturally – and literally – securing the participants in the location. Some co- design experiences are highly impactful, reminding us of the ongoing importance of positioning culture, history, and truth-telling at the forefront of our work. One Aboriginal team member recounts one co-design workshop that illustrates the power of stories to share history, learning and truth-telling not as (re)traumatising, but as recognition and healing. It shows the power of privileging Aboriginal voices to open a differentspace for coming together and being seen and heard:

This workshop was held on the anniversary of the Australian 1967 Referendum and one day after National Sorry Day. After the Acknowledgment of Country, we took an unplanned moment to reflect on the significance of the Referendum. Without prompting or priming the Aboriginal participants in the room began sharing their own stories or their family's stories about what it was like to not be seen as citizens in their own country. Elders shared their personal stories about their decision to apply or not for citizenship rights.

The Elders explained that they were not allowed to associate with other Aboriginal people who did not have their citizenship (which inevitably included family) or to speak their language if their application was successful, and how some people chose to tear their citizenship papers up when they struggled to adhere to the racist laws being imposed on them and their family. The prohibited zones and curfews in the city were talked about. The ways in which people navigated the system and resisted in their own ways were shared. Some of the Aboriginal youth co-researchers had never heard these stories before. Elders usually reserved or quiet spoke up strongly as they recounted their lived experiences.

For the non-Aboriginal people in the space, hearing this information first-hand, was both a shock and surprise. Many had not known about the racist and exclusionary policies that existed, and they certainly had not heard these stories recounted in such a direct fashion. The Elders commanded the space and shared with passion, kindness, and in good faith that their story would mean something to those present. They didn’t share because they were required or asked to; they shared because they wanted to. The experience of being seen and heard was personally powerful and validating for me. I recall sharing my own experience and the impact on generations who came after these policies were lifted. The knowledge gap in education as well as the generational knowledge gap for some Black kids is clearly highlighted through my own lived experience.

Being well-informed and inter-connected helps to realise the value of priorities and outcomes that are shared by many rather than determined by a select few. How a person or group arrives at an outcome is just as important to Nyoongar people as achieving the outcome. A more meaningful and sustainable result is likely to be attained if the process is inclusive and respectful of all points of view. This sends a powerful message to researchers that, to be sure their research is impactful, they must embed knowledge translation firmly into the research design and co-design research priorities and outcomes together with community members:

No, we’re not going to change their minds overnight. We can give them 1000 practices and ways of working with our people; they’re not going to listen until they sit down at the table and start listening and stepping into our worldview (Elder co-researcher, semi-structured focus group, 2015).

Well, it’s a two-way learning like I said. We’re working with Wadjellas [white people] and we’re working with Nyoongars. We’re working with all Aboriginal people around the place. It’s the connection and the way you want to work it. Unless you’ve got that, you’re not going to achieve things (Elder co-researcher, semi-structured interview, 2014).

Conclusions: debakarn koorliny wangkiny, steady, moving forward together

In responding to the very real need for systemic change, services have been challenged to forensically examine what is required to ensure Aboriginal people and their families are involved in the decisions made about their own recovery and health care. As service providers have grown in confidence, there has been a noticeable shift in their competence and we have witnessed first-hand the changes made through their continual weaving of learning and deepening understanding in their relationship with Elders and Aboriginal young people.

There are lessons to be learnt here for knowledge translation and impactful research. Engaging with First Nations people in the ways described in this article demonstrates the myriad opportunities to create systems and structures that respond to different worldviews for the benefit of those who are directly impacted. It may be said that relationships are personal, but when relationships are valued in our workplaces, societal structures and systems as being fundamental to the human condition, then relationships carry our ways of working forward to be authentic, meaningful and necessary in all facets of our lives.

In this article, we have outlined a relational Aboriginal participatory action research methodology that incorporates the central guiding role of Elders, facilitates shared storying, engages non-Indigenous and Indigenous people together in On Country and culturally immersive activities, and sets a space for co-design to occur. Service providers can better understand the central role culture plays in the mental health and wellbeing of First Nations people. Service leaders have come to highly value Elders’ cultural knowledge and leadership, such that their organisations have irrevocably changed. These are the conditions required to acknowledge First Nation ways of being and doing, incorporating different worldviews, valuing diversity and its creative possibilities.

To close, in the spirit of the relationship, we end with reflections about the Elders by a team member, an emerging Nyoongar researcher. It is entirely fitting that the wisdom of the Elders be left to resonate with the reader:

‘Debakarn, girl’, Aunty says in a hushed but gentle tone, a message meant only for me. Her presence is soft but strong and unyielding. She scans the room with her hawk-eyed gaze taking everything in, and when her eyes hover, I know she's recognised a familiar face. I'm moving too fast. She can see my mind ticking over a hundred miles a minute, and I'm nervous. She reaches her hand out to mine, a quick squeeze is all it takes. A wave of relief washes over me and the butterflies melt away.

She holds herself in a way that is unapologetic while simultaneously graceful. Behind that gentle exterior lies thousands of years' worth of wisdom and leadership. Though, just by looking at her, you wouldn't think she could command a room of that size. Floral, pastel prints cover her tiny frame, grey hair layers her shoulders, where a small but intricate sunflower broach sits perched against her purple pastel cardigan. She positions her walking stick out in front of her, angled comfortably to host her hands, which smell of Deep Heat and Emu Oil.

The room bustles with chatter. Elders greet one another and catch up, the laughter is infectious. I've heard so many people speak about what holds us together as a community, and humour is rarely acknowledged, but when mob get together, you can hear the laughter from around the corner. I'm not talking about that giggle in the back of your throat; I'm talking about that bellyache, can't breathe, tears running down your face laughter, that makes-you-feel-good-to-be-alive-laughter, it'll save your life.

As Elders continue to yarn with each other around the room, Aunty remains perfectly comfortable with her walking stick in hand and a cup of tea at her side, white with one sugar no doubt. Elders approach Aunty one after the other, all reaching down to embrace her while exchanging the latest news in their lives. She greets everyone with the same love and attentiveness; she smiles and her face lights up. I can feel the warmth.

Everyone is seated and the discussion is pointed. A room full of Elders. I soak it in. Aunty sighs and I can't help but wonder if she's tired of having the same conversations. I imagine what it feels like to listen to the same song for the thousandth time or slam my head against a brick wall a thousand times. She clears her throat and the room quietens in anticipation, an image of a Nyoongar mafia pops into my mind and I audibly giggle. Aunty glances a look in my direction – from experience, I know this look means I'm either in big trouble or really big trouble and there's no way to tell which until it's happening.

Aunty addresses the Elders' group. She is the Elder of Elders and holds seniority in the room. In that moment she looks tired, and I wonder why she continues to come back, why they all do. All the Elders in the room have been fighting their entire lives, but they continue to show up. ‘I keep doing this so my grandkids don't have to grow up the same way I did, so they don't have to fight as hard as we did. I will continue to show up and continue to fight until the day I die if it means future generations have a better chance’.

My heart pounds; she's read my mind.

Ethics approvals

WA Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee: HRE262-11/09 (reciprocal ethics approval University of Western Australia: HRERA/4/1/2581), HRE772 (reciprocal ethics approval Curtin University: HRE2017-0446); HRE762 (reciprocal ethics approval Curtin University: HRE2017-0350); HRE955 (reciprocal ethics approval Curtin University: HRE2020-0023).

Acknowledgements

There are numerous colleagues and partners who have journeyed with us in this work. Firstly, we pay our deep respects to the Elder co-researchers and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth co-researchers with whom we work. Without their engagement, guidance and truth-telling, this work would not be possible. We extend our gratitude to our service organisation partners who have committed to learning and growing alongside us with humility and openness. We thank the project investigator teams for their expertise and support. We thank our former team members and researchers who have informed our approach through their committed efforts. Finally, we are indebted to the Aboriginal community for trusting us in this work – without their stories, culture and lived experiences none of this would be possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2016). Census data 2016: Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, June 2016, Indigenous Regions. Canberra ACT.

- Battiste, M., & Youngblood, J. (2000). Protecting Indigenous knowledge and heritage: A global challenge.

- Cornell, S. (2015). “Wolves have a constitution:” Continuities in Indigenous self-government. The International Indigenous Policy Journal, 6(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2015.6.1.8

- Culbong, T., Crisp, N., Biedermann, B., Lin, A., Pearson, G., Eades, A.-M., Wright, M. (2022). Building a Nyoongar work practice model for Aboriginal youth mental health: Prioritising trust, culture and spirit, and new ways of working. Health Sociology Review, 31(2), 173–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/14461242.2022.2087534

- Datta, R. (2018). Decolonizing both researcher and research and its effectiveness in Indigenous research. Research Ethics, 14(2), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747016117733296

- Dudgeon, P., Bray, A., Darlaston-Jones, D., & Walker, R. (2020). Aboriginal participatory action research: An Indigenous research methodology strengthening decolonisation and social and emotional wellbeing. The Lowitja Institute.

- Fals-Borda, O. (1987). The application of participatory action-research in Latin America. International Sociology, 2(4), 329–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/026858098700200401

- Fejo-King, C. (2015). The fire of resilience: Insights from an Aboriginal social worker. Magpie Goose.

- Gegeo, D. W., & Watson-Gegeo, K. A. (2001). “How we know”: Kwara’ae rural villagers doing Indigenous epistemology. The Contemporary Pacific, 13(1), 55–88. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23718509

- Haebich, A. (2000). Broken circles. Fremantle Press.

- Hansen, L., Hansen, P., Corbett, J., Hendrick, A., & Marchant, T. (2020). Reaching across the divide (RAD): Aboriginal elders and academics working together to improve student and staff cultural capability outcomes. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 50(2), 284–292. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2020.23

- Henry, E., & Foley, D. (2018). Indigenous research: Ontologies, axiologies, epistemologies and methodologies. In L. A. E. Booysen, R. Bendl, & J. K. Pringle (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in diversity management, equality and inclusion at work (pp. 212–227). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Host, J. T., & Owens, C. (2009). ‘It’s still in my heart this is my country’: The single Noongar claim history. UWA Publishing.

- Jull, J., Morton-Ninomiya, M., Compton, I., Picard, A. (2018). Fostering the conduct of ethical and equitable research practices: The imperative for integrated knowledge translation in research conducted by and with Indigenous community members. Research Involvement and Engagement, 4(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-018-0131-1

- Keikelame, M. J., & Swartz, L. (2019). Decolonising research methodologies: Lessons from a qualitative research project, Cape Town, South Africa. Global Health Action, 12(1), 1561175. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2018.1561175

- Kovach, M. (2021). Indigenous methodologies: Characteristics, conversations, and contexts. University of Toronto press.

- Kowal, E. (2011). The stigma of white privilege. Cultural Studies, 25(3), 313–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2010.491159

- Milroy, J., & Revell, G. (2013). Aboriginal story systems: Remapping the west, knowing country, sharing space. Occasion: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Humanities, 5, 1–24.

- Morton Ninomiya, M. E., Hurley, N., & Penashue, J. (2020). A decolonizing method of inquiry: Using institutional ethnography to facilitate community-based research and knowledge translation. Critical Public Health, 30(2), 220–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2018.1541228

- Morton Ninomiya, M. E., & Pollock, N. J. (2017). Reconciling community-based Indigenous research and academic practices: Knowing principles is not always enough. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 172, 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.11.007

- Nakata, M. (1997). The cultural interface: An exploration of the intersection of western knowledge systems and Torres strait islanders positions and experiences. James Cook University.

- Rigney, L.-I. (2017). Indigenist research and Aboriginal Australia. Indigenous peoples' wisdom and power (1st ed., p. 32–48). Routledge.

- Rudman, M. T., Flavell, H., Harris, C., & Wright, M. (2021). How prepared is Australian occupational therapy to decolonise its practice? Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 68(4), 287–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12725

- Ryder, C., Mackean, T., Coombs, J., Williams, H., Hunter, K., Holland, A. J., & Ivers, R. Q. (2020). Indigenous research methodology – weaving a research interface. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 23(3), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2019.1669923

- Sasakamoose, J., Bellegarde, T., Sutherland, W., Pete, S., & McKay-McNabb, K. (2017). Miýo-pimātisiwin developing Indigenous cultural responsiveness theory (ICRT): improving Indigenous health and well-being. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 8(4), https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2017.8.4.1

- Seehawer, M. K. (2018). Decolonising research in a Sub-Saharan African context: Exploring Ubuntu as a foundation for research methodology, ethics and agenda. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 21(4), 453–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2018.1432404

- Sherriff, S. L., Miller, H., Tong, A., Williamson, A., Muthayya, S., Redman, S., Bailey, S., Eades, S., & Haynes, A. (2019). Building trust and sharing power for co-creation in Aboriginal health research: A stakeholder interview study. Evidence & Policy, 15(3), 371–392. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426419X15524681005401

- Smith, L. T. (2021). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Smylie, J., Olding, M., & Ziegler, C. (2014). Sharing what we know about living a good life: Indigenous approaches to knowledge translation. The Journal of the Canadian Health Libraries Association / Chla = Journal De L’association Des Bibliotheques De La Sante Du Canada / Absc, 35(1), 16–23. https://doi.org/10.5596/c14-009

- Snijder, M., Wagemakers, A., Calabria, B., Byrne, B., O'Neill, J., Bamblett, R., Munro, A., & Shakeshaft, A. (2020). ‘We walked side by side through the whole thing’: A mixed-methods study of key elements of community-based participatory research partnerships between rural Aboriginal communities and researchers. The Australian Journal of Rural Health 28(4), 338–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12655

- Styres, S. D. (2011). Land as first teacher: A philosophical journeying. Reflective Practice, 12(6), 717–731. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2011.601083

- Tilbrook, L. (1983). The first South Westerners: Aborigines of South Western Australia.

- Wright, M. (2011). Research as intervention: Engaging silenced voices. ALAR: Action Learning and Action Research Journal, 17(2), 25–46. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.463130742827571

- Wright, M. (2014). Reframing Aboriginal family caregiving. Working together, second edition. (2nd ed, pp. 243–256). Telethon Kids Institute.

- Wright, M., Brown, A., Dudgeon, P., McPhee, R., Coffin, J., Pearson, G., Lin, A., Newnham, E., King Baguley, K., Webb, M., Sibosado, A., Crisp, N., Flavell, H. L. (2021). Our journey, our story: A study protocol for the evaluation of a co-design framework to improve services for Aboriginal youth mental health and well-being. BMJ Open, 11(5), e042981. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042981

- Wright, M., Culbong, M., Jones, T., O’Connell, M., & Ford, D. (2013). Making a difference: Engaging both hearts and minds in research practice. Action Learning and Action Research Journal, 19(1). https://alarj.alarassociation.org/index.php/alarj/article/view/64 (Accessed 29 January 2023)

- Wright, M., Culbong, M., O’Connell, M. (2013). Weaving the narratives of relationship in community participatory research. New Community Quarterly, 11(43), 8–14.

- Wright, M., Culbong, T., Crisp, N., Biedermann, B., & Lin, A. (2019). “If you don’t speak from the heart, the young mob aren’t going to listen at all”: An invitation for youth mental health services to engage in new ways of working. Early intervention in Psychiatry, 13(6), 1506–1512. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12844.

- Wright, M., Getta, A. D., Green, A. O., Kickett, U., Kickett, A., McNamara, A., McNamara, U., Newman, A., Pell, A., Penny, A., Wilkes, U., Wilkes, A., Culbong, T., Taylor, K., Brown, A., Dudgeon, P., Pearson, G., Allsop, S., Lin, A., … O'Connell, M. (2021). Co-designing health service evaluation tools that foreground first nation worldviews for better mental health and wellbeing outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168555

- Wright, M., Lin, A., & O'Connell, M. (2016). Humility, inquisitiveness, and openness: Key attributes for meaningful engagement with Nyoongar people. Advances in Mental Health, 14(2), 82–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/18387357.2016.1173516

- Wright, M., & O’Connell, M. (2015). Negotiating the right path: Working together to effect change in healthcare service provision to Aboriginal peoples. Action Learning and Action Research Journal, 21(1). https://alarj.alarassociation.org/index.php/alarj/article/view/143 (Accessed 29 January 2023).

- Wright, M., O'Connell, M., Jones, T., Walley, R., & Roarty, L. (2015). Looking forward Aboriginal mental health project: Final report. Telethon Kids Institute.