ABSTRACT

While there is a well-developed body of literature in the health field that describes processes to implement research, there is a dearth of similar literature in the disability field of research involving complex conditions. Moreover, the development of meaningful and sustainable knowledge translation is now a standard component of the research process. Knowledge users, including community members, service providers, and policy makers now call for evidence-led meaningful activities to occur rapidly. In response, this article presents a case study that explores the needs and priorities of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in Australia who have experienced a traumatic brain injury due to family violence. Drawing on the work of Indigenous disability scholars such as Gilroy, Avery and others, this article describes the practical and conceptual methods used to transform research to respond to the realities of community concerns and priorities, cultural considerations and complex safety factors. This article offers a unique perspective on how to increase research relevance to knowledge users and enhance the quality of data collection while also overcoming prolonged delays of knowledge translation that can result from the research-production process.

Introduction

Compared with other Australians, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experience disproportionately higher rates of disability (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2019). A leading cause of disability for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is traumatic brain injury (TBI) (Jamieson et al., Citation2008; Katzenellenbogen et al., Citation2018). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with acquired TBI are in greater contact with the court and prison systems and experience exponential barriers to safe, appropriate, and supportive healthcare (Gilroy et al., Citation2016; Lakhani et al., Citation2017; Toccalino et al., Citation2022). The lived experiences of TBI for Indigenous peoples in settler colonial countries globally suggests that the intersectionality of Indigeneity and TBI significantly compounds enduring layers of discrimination (Gilroy et al., Citation2021). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are a high-risk population for head injuries, mostly because of violence. For example, the rate of head injury due to assault (1999–2005) among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women was 69 times compared with other Australian women (Jamieson et al., Citation2008). It is therefore imperative that any research conducted in this area has a direct translation impact to address the levels of violence experienced alongside service responsiveness and safety for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women (Fitts, Bird, et al., Citation2019). The translation of research into practice in this area requires a rigorous body of knowledge around cultural, methodological, and practical approaches that are both meaningful to and respectful of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women with a TBI.

In this article, we present the collaborative procedure we followed when designing and implementing a three-year multisite project focused on listening to and learning from the experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who have experienced a head injury and/or are now diagnosed TBI because of family violence (Fitts et al., Citation2023). Given the critical need for cultural responsiveness and safe service provision, service providers and hospital staff who are responsible for providing care and support services of relevance are also included. This article reflects on the research processes, adaptations, and practices that were specifically required to incorporate an integrated, community co- designed knowledge translation approach early in the research project. The research partners and team decided to implement an educational knowledge-translation program as part of the initial data collection process. This strategy aimed to increase participation of the intended research audience by improving local understandings of the impact of TBI on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women's daily lives.

The invisibility of Indigenous women with disability: the necessity of embedded knowledge-translation practices

As this article is drawing on the case example of women who experience TBI through violence, we have incorporated the work of feminist disability scholars such as Salmon (Citation2011) as well as Stienstra and colleagues (Citation2018) who have worked explicitly with Indigenous women in Canada on issues of violence and the (re)production of impairment as an outcome. Salmon as well as Stienstra and colleagues begun by thinking through the question, ‘What makes Indigenous women and girls with disabilities largely invisible in Northern Canada and how do we, as researchers, work with them to amplify their voices and share their stories and experiences’? This question is central to our research project undertaken in Australia, given that disability arising from family violence is rarely, if at all, recognised as a critical concern within family violence research. In fact, as demonstrated in the existing data, acquired disability of all types – including TBI – through gender-based violence remains invisible across frontline service and hospital domains (Fitts et al., Citation2022).

In the broader context of this research, success in the knowledge-translation process comes down to researcher capacity to practice deep and respectful listening to understand the types and formats of content required for an embedded knowledge-translation action plan that is meaningful for the participants. As Stienstra and colleagues (Citation2018) suggested, when a group of people with specific needs are rendered invisible, their civic entitlements remain unseen and unaddressed. But this question of invisibility can also affect the relevance of research to its intended beneficiaries, making dialogue with participants critical to the process of understanding what they want from the research and what they want it to do. Listening is a crucial element in making the experiences of research populations visible and translatable. Listening helps researchers to think more carefully about the language they use to describe the issue that affects the population involved in the research. It also provides control to the research population of the research aims and direction so they can recast it in their own ways to achieve greater impact and take up overall.

Listening is also critical to the work of culturally responsive research with culturally and racially marginalised people. As Indigenous disability scholar Avery (Citation2018) argued, Western disability research is often subject to critique by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples for its tendency towards medicalisation in positioning dis ability as defective and in need of Western therapeutic interventions, medicines, and rehabilitation (Berghs et al., Citation2016; Rivas Velarde, Citation2018). As is now well established within the Indigenous disability scholarship, there is no equivalent word in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages for ‘disability’, and many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living with disabilities also do not self-identify as having a ‘disability’ (see Ariotti, Citation1999; Grant et al., Citation2014). For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experiencing disability, the language of ‘disability’ can create significant barriers to their research participation and engagement (Stienstra et al., Citation2018). First, Western notions of disability carry significant stigma (Gilroy, Lincoln, et al., Citation2018). Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples therefore avoid disability diagnoses and labels. For Aboriginal women, the concept of disability is also associated with the colonial practice of the state removal of children deemed to have a disability or impairment from mothers and families, which has resulted in loss of family, Country, law, and ceremonies (Ariotti, Citation1999).

A further failure of health research has been the reproduction of colonial ways of doing knowledge translation (Estey et al., Citation2010; Smylie et al., Citation2014). The field of knowledge translation is concerned with how to bridge the research/research-user divide (Straus et al., Citation2009) and has been defined as the ‘exchange, synthesis and ethically-sound application of knowledge – within a complex system of interactions among researchers and users – to accelerate the capture of the benefits of research’ (Graham et al., Citation2006). Historically, the act of research using a Western knowledge system is a linear and objective process where the research team focuses their energies on knowledge-translation activities as the final stage of the research journey once data collection and analysis are completed. Indigenous scholars such as Smylie and colleagues (Citation2004) suggested Indigenous knowledge systems are at odds with a Western approach, as the former are ecologic, holistic, and relational. As Indigenous scholar-practitioner Dowling (Citation2022) outlined, the knowledge translation-research nexus can disrupt the continuity of past injustices in present-day policymaking. It can also actively facilitate Indigenous rights in policymaking processes and outcomes with research take-up.

A variety of research models and frameworks have emerged in Australia and similar settler colonial nations such as Canada to reorient the ways research and knowledge translation are conducted (Dew & Boydell, Citation2017; Vargas et al., Citation2022). Similarities among the approaches include recognition of the time necessary to build sustainable and trusting partnerships between researchers and the community research partners from the outset; a focus on the co-creation, co-design, and co-production of essential research components and processes, rather than merely labelling research activities for each stage; centring collaborative research orientations from the point of research conceptualisation as the core ethical value of practice to inform the overall design; and adapting and adjusting the research parameters, particularly when in the field, including allowing for additional time and financial investment required to complete the work in line with community partner expectations (Nguyen et al., Citation2020).

Indigenous disability scholars such as Gilroy and McEntyre, as well as community-controlled organisations, have outlined the decolonising methodological approaches they have used to strengthen cultural sensitivity, legitimacy, and responsiveness within their work (Gilroy, Lincoln, et al., Citation2018; McEntyre et al., Citation2019). Some examples include flexibility in data collection (e.g., continuing data collection until all members of a community who wish to participate have been interviewed, rather than stopping at data saturation, as well as the employment of local Aboriginal community members who can act as interlocutors or brokers for participant recruitment and feedback on the conduct of the research project as well as draft versions of resources and research findings. In other examples, local art and resources have been commissioned to increase connection and relevancy of the project to communities and as tools to elevate the voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples living with disability (Bohanna et al., Citation2019; Gilroy, Dew, et al., Citation2018). As discussed in the following sections, we map the knowledge translation practices co-designed early with our partners to ensure that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women were actively engaging through learning about the lived implications of TBI from the outset of the fieldwork

A case study on acquired disability through TBI as an outcome of violence

In Western medicine, TBI is defined as damage to, or alteration of brain function due to a blow or force to the head (Menon et al., Citation2010). As a subset of acquired brain injury, TBI can consist of various short- and long-term cognitive impacts as well as psychological and physical consequences. Disabilities resulting from a TBI depend on the severity and location of the injury. Some common changes can include memory loss, difficulty with motivation, limited insight, sensory and perceptual problems, fatigue and sleep difficulties, as well as mood changes and anxiety (Baxter & Hellewell, Citation2019).

To explore the topic in-depth, the following participant cohorts were invited to participate in the project: (1) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women (aged 18+) with lived experience of head injuries or diagnosed TBI as an outcome of family violence; (2) family members and carers of women with head injuries or diagnosed TBI as an outcome of family violence; (3) hospital staff; and (4) service providers including family violence, health, housing and crisis accommodation, social, disability, mental health, and legal sectors, as well as local community groups. Meeting and field-trip notes and interview data were used to map the changes to the study design to respond to feedback from the knowledge holders, including community Elders and leaders, community group members (including women's groups), and the service-provider workforce.

The project team consisted of three Aboriginal and three non-Indigenous research team members. Aboriginal team members had a background in advocacy and research roles as well as legal and family violence service provision. One Aboriginal team member was a traditional owner in one project location. In the other project location, one Aboriginal team member had extended family relationships. Non-Indigenous team members had a background in health and disability research as well as health-service provision. Some members of the team also had lived experience of family violence. Four members of the research team had previously collaborated on TBI and disability research projects with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples across Northern Australia (Fitts, Bird, et al., Citation2019; Fitts, Condon, et al., Citation2019; Soldatic & Fitts, Citation2020; Townsend et al., Citation2019), which included one project location within the current project (Fitts et al., Citation2023). The project was also guided by an advisory group that consisted mainly of Aboriginal women from service providers and advocacy services.

To achieve a broader understanding of the diversity of lived experience, the project targeted three different locations (urban, regional, and remote) across the Australian jurisdictions of Queensland, Northern Territory, and New South Wales. One project team member is based at a national brain injury organisation (referred to as ‘the partner organisation’). The partner organisation is Australia’s peak organisation for the advocacy of people with brain injury. The partner organisation provides specialist support services for people living with brain injury, delivers community and service provider TBI education and training, and participates in targeted research activities.

As presented in the next section, our implementation and data-collection activities add compelling evidence of how two-way learning and knowledge feedback loops created a dynamic environment tailored to the needs of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities the research was meant to serve. Our collaborative knowledge-translation approach generated critical dialogue with research participants about the complex and sensitive issue of living with impairment and disability, as well as the research process itself and its educational purpose.

Redistribution of the power dynamics between knowledge holders and researchers

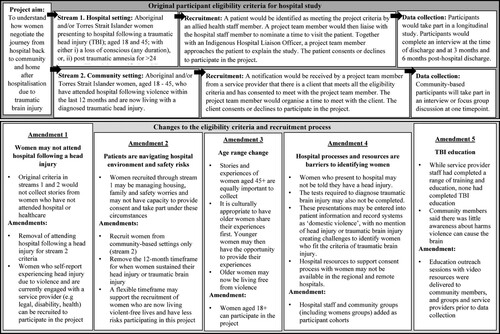

Over six months, the research team met with community Elders and members of community groups, service providers, and hospital staff to collect feedback about the research objectives and methodology. The project originally included a longitudinal study to connect the research team with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, aged 18 to 45 years, who presented to hospital with a TBI through family violence (stream 1, ). It also included a community-based recruitment approach with women in the community who have attended hospital following violence and were diagnosed TBI within the last 12 months (stream 2, ). The initial recruitment pathways had to be rethought considering the six barriers identified by community members and service providers that impact women’s access to healthcare services (see amendments 1–3, ). First, health professionals at a hospital might not inform women who present to the hospital that they have experienced a TBI. Second, the treating medical team might not order the tests required to diagnose TBI. Third, these presentations might be entered into patient information and record systems as ‘domestic violence’, with no reference to head injury or TBI – this can hinder participant recruitment in identifying women who fit the criteria of TBI. Fourth, the hospital might not have the resources to ensure that women experiencing family violence indicate informed consent to participate in the research. Fifth, women who present to hospital following family violence contend with a range of urgent needs requiring support, including the need for safe housing for themselves and their children (Cripps & Adams, Citation2014). Sixth, women might not present to hospitals for healthcare following violence as they face several dilemmas accessing healthcare or reporting violence to police. If women report violence, this can put them at high-risk of experiencing further violence. The work of Aboriginal scholars such as Langton and colleagues (Citation2020) as well as Cripps and Adams (Citation2014) also showed that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women decide not to access healthcare following violence due to a fear of greater contact with police and potential child removal. This feedback from service providers shifted the research focus beyond hospitals, with the recognition that women do not follow a linear process of accessing hospital care, getting a diagnostic assessment, and moving onto recovery and rehabilitation. The project design was therefore amended to include additional target participants sourced from community groups (including women's groups) and hospital staff (see amendment 4, ).

The age range targeted in the original project design for women presenting to hospital with a TBI following violence reflected the high rates of family violence and head injuries experienced by women in that age category. The reshaping of the project to adopt a broader age inclusion (aged 18+) came from knowledge holders’ comments that the project might benefit from older women (aged 40+) who were no longer in but had previously experienced violent relationships. Some older women were in a safer position to participate in the project and could provide valuable information about their experiences. Older people have intersecting central roles, responsibilities, and occupation in the community, including as mentors and caretakers of cultural knowledge.

Reframing the narrative of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who experience violence

The project commissioned artwork at each project location to reflect and celebrate the powerful presence and influence of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in families and communities (see ). The intention of these artworks was to improve relatability through the storytelling of local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women to symbolise the strength and resilience of women and the importance of healing. The artworks are layered and textured, speaking to the rich diversity of culture, heritage, and histories.

Importantly, the work of the women artists symbolised the purpose and intent of the research in a manner that demonstrated cultural respect and understanding. By commissioning local women artists, the research team sought to articulate to local potential Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women participants that they had given an extensive commitment – of both time and resources – to learn about local women's experiences and include, from the outset, the narratives of local women who had experienced, either directly or indirectly, the impact of family violence on their communities. Importantly, it enabled the research team to demonstrate to potential Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women participants that their stories of family violence, TBI, and where possible, recovery, were considered important to build broader responsive service systems for future generations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women.

Research feedback loops – increasing validity and legibility of the project

Within the implementation meetings, the research team received consistent comments from community leaders and community members about low levels of knowledge and recognition of the long-term injuries and damage to the brain from family violence. As one community group member commented, ‘We didn't know about this brain injury’. To increase knowledge access, education outreach sessions were held with community organisations and service providers without formalised data collection to respond to community leaders’ recommendation about wider delivery of the education: ‘[It’s] important for [the] community to know – have awareness about it – brain damage and DV [domestic violence]’ (community group member).

Low levels of knowledge and training regarding TBI was also across government and community-controlled service sectors in combination with community leaders. While service providers had invested in their workforce, completing a range of training and education, none of the service providers involved with the project had completed TBI education

We have training about a lot of different things, but training around how to help people with an acquired or a traumatic brain injury is not something I’ve come across in this space, in this case management space, [in contrast to] trauma-informed care person, [and] client-centred practice, that sort of training. We get ADD [attention-deficit disorder] workshops, we get domestic and family violence workshops, disability support workshops, but nothing around brain injury (community-based service provider).

This training would be helpful because we aren't a health service. We have information about women who have been to hospital and diagnosed with a brain injury, but we aren't medically trained, we’re lawyers. So, this will help us identify women who fit the criteria and have these conversations with them, to explain the project and why it's happening (community-based service provider).

Disrupting the linear process of knowledge translation: implementing knowledge translation into research design

Education outreach sessions were delivered by two Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander educators. The education was an existing resource the partner organisation had devel- oped for Aboriginal and Torres Strait communities and services providers working in regional and remote locations. Among the topics covered were the psychological, behavioural, and cognitive challenges that can occur with acquired brain injury and how other health conditions can display similar symptoms (e.g., mental health conditions). The facilitators drew on real case examples from work the partner organisation had done with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with acquired brain injuries in communities as well as in the court and prison systems. The education sessions appeared to provide community members with greater confidence to share information and stories of women they knew who had experienced head injuries through family violence:

[The education outreach session] was raising awareness. We see women who had this happen to them. They don't recognise who you are, are forgetting things. They get moody and upset with noises (elder and community-based service provider).

The contextual relevance of the content was critical to community groups and service providers to gain the benefits of the education and translate the knowledge into practice:

I think it's always difficult finding training that's contextually relevant as well, because some of these trainings like I said before, we might be working in line with best practice, but if best practice is to take someone to ED [emergency department] immediately, what does that look like in a remote community? So sometimes it's a bit hard finding, I guess adapting those trainings to our context (community-based service provider).

This really is an area that, I think, there's just maturity and skills to be built for us and to be able to believe, just for us to recognise what's happening for them. Because, I think, everyone that works here believes [it is] happening and it's very real for some women, where to go in terms of the support that we can provide. I think, it's really good to do this type of training. Because also with the barriers, that in itself is a barrier for women, right, because they’re not, the service providers aren't fully understanding what's happening to them (community- based service provider).

[It would be good] if we could have a few key questions, with how we broach the conversation with our clients in a way that is appropriate, because we screen for violence but we don't screen for brain injury (community-based member).

Experts through experience: the power of digital stories

Augmenting the education outreach sessions were digital storytelling resources of people sharing their personal journeys of TBI. The video was a part of a suite of resources (including patient and carer booklets) developed under a previous research project on the experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples transitioning from hospital to home (Bohanna et al., Citation2019). The primary video presented in the education outreach sessions was inspired by the experiences of an Aboriginal woman (the ‘storyteller’) who has sustained a violence-related TBI. Still images selected from the storyteller's personal collection were used in combination with filmed footage in a location selected by the storyteller.

Education outreach where stories were shared created ‘teachability’ opportunities (Stenhouse & Tait, Citation2014), allowing information and knowledge to be shared across time and space. These opportunities offered the individuals who attended a deeper understanding of the experience of TBI and how someone navigates the challenges and opportunities of rebuilding their identity

‘I was a go getter’. And she still is, how awesome is that. Wow … she had to learn to walk and talk again. She is such a strong woman, resilient to have worked so hard to get control back in her life. You wouldn't think that when you see her (community-based service provider).

As a service provider, you think, why did I not think about this earlier? Now that we are having this conversation, I can think of a few clients, one in particular who we thought had mental health issues and also had a long history of AOD [alcohol and other drugs], but it is likely that she was experiencing a brain injury after the years of violence she had suffered. But we didn't pick that up when we were working with her (community-based service provider).

As she said on the video, you forget your appointments. When we think about women missing their appointments, it can be seen that they don't care about their health or attending appointments for their kids. It is because they can't retain the information (community-based service provider).

Concluding discussion

This article has presented an overview of the implementation of a project designed to understand the needs and priorities of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women with head injuries (or diagnosed TBI) as an outcome of family violence in one regional and one remote location in Australia. Drawing on the principles of co-creation in the design of the essential research components (Nguyen et al., Citation2020; Vargas et al., Citation2022), the processes followed in this case study highlight how two-way knowledge-sharing can flatten power differences and integrate decolonising social-care approaches into rigorous research praxis (Gilroy, Lincoln, et al., Citation2018). Indigenous scholars, such as Gilroy, describe the importance of decolonising disability research to lead to meaningful outcomes for knowledge users and their communities, starting with dissolving of the privileged position of colonial power and control (Gilroy, Dew, et al., Citation2018). The dynamic use of community knowledge feedback loops within the participation criteria and recruitment environment provided a means of autonomous self-representation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who had experienced TBI following family violence. These community knowledge feedback loops transformed the research process at every stage of its design. The feedback loops responded to the realities of community priorities and concerns, cultural considerations and complex safety factors that were particularly racialised for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, children and their communities with present settler colonial governance (Ariotti, Citation1999; Avery, Citation2018).

The ‘blending’ of the conceptual elements in knowledge translation, together with the practical steps described within collaborative approaches to research (Dew & Boydell, Citation2017; Nguyen et al., Citation2020; Vargas et al., Citation2022) achieved a rigorous and engaged two-way exchange. Both knowledge holders and research knowers were viewed as possessing relevant and complementary expertise in the subject matter. These non-linear activities responded to feedback from knowledge users (community members, community groups, and service providers) while ensuring participants had a baseline understanding of TBI. The education outreach and video resources together with data collection ultimately improved research relevance to knowledge users and led to rich insights for all those involved with the research. Such an approach overcame the limitations of research outcomes where knowledge users find themselves challenged to apply research findings in their day-to-day lives. This approach also circumvented the lengthy delays typically associated with research that seeks to transform policies, public awareness and service provision. Bringing education directly to service providers removed some of geographical distance and resource pressures that are well-described barriers for restricting access to continuing professional development for regional and remote health professionals.

Outside the relationships between the knowledge holders (community and service providers) and the research team, the established relationships within the project team were equally critical to the dynamic nature of the project. Established relationships of trust between a diverse range of project partners (academics, service providers, and advocates) leveraged the project's capacity to collect feedback from multiple field sites (hospital, community, and service providers) on the methodology as initially conceptualised and to respond rapidly to that feedback through making adjustments (McEntyre et al., Citation2019). The project team drew on their experiences in co-creating resources with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities living with TBI as well as acquired brain injury more broadly (Bohanna et al., Citation2019).

Returning to the work of Stenhouse and Tait (Citation2014), education through the retelling of the recovery journey provided an opportunity for service providers to look beyond the changes that can occur cognitively, psychologically, and behaviourally with TBI. The storytelling component in the education outreach workshops and the video resources supported the dismantling of the biomedical model or impairment-based view of the injury, which has persisted in disability research for decades with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (Avery, Citation2018). Moving away from that model where TBI is thought of as a deficit that requires ‘fixing', sharing stories moved the audience to consider individuals’ hopes and desires alongside the complex emotions of grief and loss in their narratives of self-discovery. The rebuilding of a new life in language and terminology that is familiar to the audience – rather than, say, the dispassionate and alienating technical language typically used in medicine – is what enables the making of meaning for the realisation of rights in real-world policy making and everyday practices.

Finally, disability within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities is a con- tentious issue for data collection. This is chiefly because this terminology often has different cultural interpretations contingent on local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge systems. In the Australian context, the construct of ‘disability' – with its emphasis on deficit and dysfunction – does not resonate with, nor is accepted within some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities (Ariotti, Citation1999; Grant et al., Citation2014). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander womens’ differential and embodied cultural knowledges of injury and chronic conditions can create opportunities to open out and expand practices of disability rights realisation in ways that consolidate Indigenous rights as enshrined within the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (Citation2007). The incorporation of disability rights, such as the right to respect home and the family (United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Citation2006), as enshrined in international law, can strengthen Indigenous peoples' claims for social justice. Indigenous peoples' ongoing claims for rights – such as the right to economic security and self-determination and the right to sustained social programming that realises improvements in everyday living conditions and overall quality of life – are grounded in Indigenous relationships of family, home, and kin. Through comprehensive knowledge translation, this research project gave meaning to the individual experience of family violence and TBI for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and, more importantly, critically informed essential service workers who ultimately have the power either to reinforce or actively remove Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women's rights to family and home for the years ahead post TBI.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval for the project was received from the Central Australian Human Research Ethics Committee (CA-21-4160), Townsville Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/QTHS/85271 and HREC/QTHS/88044), and Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee (H14646). The study also received approval from Aboriginal community-controlled, legal and family-violence research committees and boards and complies with national guidelines for research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Acknowledgements

We recognise and thank the ongoing support the project has received from community members, advocates, women's groups, as well as family violence, health, and legal services who have help to inform the design and implementation of this project. We would also like to acknowledge the artwork contributed to the project by all the artists. Further to this, we thank Aunty Colleen McLennan and Kylie-Lee Bradford from Synapse Australia for delivering the education sessions to community groups and service providers. Three of the authors, including JC (Bidjara and Wakka Wakka), EW (Warumungu) and YJ (Wulgurukaba), are Aboriginal women, and provided the research with an Indigenous perspective and worldview. The views reflected in this article are those of the authors only and do not reflect the funder, the Australian Research Council.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the writing of the article, or in the decision to publish the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ariotti, L. (1999). Social construction of Anangu disability. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 7(4), 216–222. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1584.1999.00228.x

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2019). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability, Disability, ageing and carers, Australia: Summary of findings. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/disability/disability-ageing-and-carers-australia-summary-findings/2018

- Avery, S. (2018). Culture is inclusion: A narrative of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability. First Peoples Disability Network.

- Baxter, K., & Hellewell, S. C. (2019). Traumatic brain injury within domestic relationships: Complications, consequences and contributing factors. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 28(6), 660–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2019.1602089

- Berghs, M., Atkin, K., Graham, H., Hatton, C., & Thomas, C. (2016). Implications for public health research of models and theories of disability: A scoping study and evidence synthesis. Public Health Research, 4(8), 1. https://doi.org/10.3310/phr04080

- Bohanna, I., Fitts, M., Bird, K., Fleming, J., Gilroy, J., Clough, A., Esterman, A., Maruff, P., & Potter, M. (2019). The potential of a narrative and creative arts approach to enhance transition outcomes for Indigenous Australians following traumatic brain injury. Brain Impairment, 20(2), 160–170. https://doi.org/10.1017/BrImp.2019.25

- Cripps, K., & Adams, M. (2014). Family violence: Pathways forward. In P. Dudgeon, H. Milry, & R. Walker (Eds.), Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice (pp. 399–416). Telethon Institute for Child Health/Kulunga Research Network; University of Western Australia.

- Dew, A., & Boydell, K. (2017). Knowledge translation: Bridging the disability research-to-practice gap. Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 4(2), 142–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/23297018.2017.1315610

- Dowling, C. (2022). Educating the heart: A journey into teaching First Nations human rights in Australia. In B. Offord, C. Fleay, L. Hartley, Y. G. Woldeyes, & D. Chan (Eds.), Activating cultural and social change: The pedagogies of human rights (1st ed, pp. 183–196). Routledge.

- Estey, E. A., Kmetic, A. M., & Reading, J. L. (2010). Thinking about Aboriginal KT: Learning from the network environments for Aboriginal Health Research British Columbia (NEARBC). Canadian Journal of Public Health, 101(1), 83–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03405569

- Fitts, M. S., Bird, K., Gilroy, J., Fleming, J., Clough, A. R., Esterman, A., Maruff, P., Fatima, Y., & Bohanna, I. A. (2019). Qualitative study on the transition support needs of Indigenous Australians following traumatic brain injury. Brain Impairment, 20(2), 137–159. https://doi.org/10.1017/BrImp.2019.24

- Fitts, M. S., Condon, T., Gilroy, J., Bird, K., Bleakley, E., Matheson, L., Fleming, J., Clough, A. R., Esterman, A., Maruff, P., & Bohanna, I. (2019). Indigenous traumatic brain injury research: Responding to recruitment challenges in the hospital environment. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), 172. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0813-x

- Fitts, M. S., Cullen, J., Kingston, G., Johnson, Y., Wills, E., & Soldatic, K. (2023). Understanding the lives of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women with acquired head injury through family violence: A qualitative study protocol. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20(2), Article 1607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021607

- Fitts, M. S., Cullen, J., Kingston, G., Wills, E., & Soldatic, K. (2022). ‘I don’t think it’s on anyone’s radar’: The workforce and system barriers to healthcare for Indigenous women following a traumatic brain injury acquired through violence in remote Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), Article 14744. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214744

- Gilroy, J., Dew, A., Barton, R., Ryall, L., Lincoln, M., Taylor, K., Jensen, H., Flood, V., & & McRae, K. (2021). Environmental and systemic challenges to delivering services for Aboriginal adults with a disability in Central Australia. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(20), 2919–2929. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1725654

- Gilroy, J., Dew, A., Lincoln, M., Ryall, L., Jensen, H., Taylor, K., Barton, R., McRae, K., & Flood, V. (2018). Indigenous persons with disability in remote Australia: Research methodology and Indigenous community control. Disability & Society, 33(7), 1025–1045. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2018.1478802

- Gilroy, J., Donnelly, M., Colmar, S., & Parmenter, T. (2016). Twelve factors that can influence the participation of Aboriginal people in disability services. Australian Indigenous Health Bulletin, 1(6), 1–9.

- Gilroy, J., Lincoln, M., Taylor, K., Flood, V., Dew, A., Jensen, H., Barton, R., Ryall, L., & McRae, K. (2018). Walykumunu Nyinaratjaku: To live a good life. Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Women’s Council Aboriginal Corporation.

- Graham, I. D., Logan, J., Harrison, M. B., Straus, S. E., Tetroe, J., Caswell, W., & Robinson, N. (2006). Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 26(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.47

- Grant, E., Chong, A., Beer, A., & Srivastava, A. (2014). The NDIS, housing and Indigenous Australians living with a disability. Parity, 27(5), 24–25. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.492646943701415

- Jamieson, L. M., Harrison, J. E., & Berry, J. G. (2008). Hospitalisation for head injury due to assault among Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians (July 1999– June 2005). Medical Journal of Australia, 188(10), 576–579. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01793.x

- Katzenellenbogen, J. M., Atkins, E., Thompson, S. C., Hersh, D., Coffin, J., Flicker, L., Hayward, C., Ciccone, N., Woods, D., Greenland, M. E., McAllister, M., & Armstrong, E. M. (2018). Missing voices: Profile, extent, and 12-month outcomes of nonfatal traumatic brain injury in Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal adults in Western Australia using linked administrative records. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 33(6), 412–423. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0000000000000371

- Lakhani, A., Townsend, C., & Bishara, J. (2017). Traumatic brain injury amongst Indigenous people: A systematic review. Brain Injury, 31(13/14), 1718–1730. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2017.1374468

- Langton, M., Smith, K., Eastman, T., O’Neill, L., Cheesman, E., & Rose, M. (2020). Family violence policies, legislation and services: Improving access and suitability for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety.

- McEntyre, E., Vaughan, P., & Dew, A. (2019). Taking the research journey together: The insider and outsider experiences of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal researchers. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.1.3156

- Menon, D. K., Schwab, K., Wright, D. W., Maas, A. I., & Demographics and Clinical Assessment Working Group of the International and Interagency Initiative toward Common Data Elements for Research on Traumatic Brain Injury and Psychological Health(2010). Position statement: Definition of traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 91(11), 1637–1640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2010.05.017

- Nguyen, T., Graham, I. D., Mrklas, K. J., Bowen, S., Cargo, M., Estabrooks, C. A., Kothari, A., Lavis, J., Macaulay, A. C., MacLead, M., Phipps, D., Ramsden, V. R., Rendew, M. J., Salsberg, J., & Wallerstein, N. (2020). How does integrated knowledge translation (IKT) compare to other collaborative research approaches to generating and translating knowledge? Learning from experts in the field. Health Research Policy and Systems, 18(1), Article 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-0539-6

- Rivas Velarde, M. (2018). Indigenous perspectives of disability. Disability Studies Quarterly, 38(4), 4. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v38i4.6114

- Salmon, A. (2011). Aboriginal mothering, FASD prevention and the contestations of neoliberal citizenship. Critical Public Health, 21(2), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2010.530643

- Smylie, J. K., Martin, C. M., Kaplan-Myrth, N., Steele, L., Tait, C., & Hogg, W. (2004). Knowledge translation and Indigenous knowledge. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 63(2), 139–143. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v63i0.17877

- Smylie, J., Olding, M., & Ziegler, C. (2014). Sharing what we know about living a good life: Indigenous approaches to knowledge translation. Journal of the Canadian Health Libraries Association / Journal de L’Association des Bibliothèques de la Santé du Canada, 35(1), 16–23. https://doi.org/10.5596/c14-009

- Soldatic, K., & Fitts, M. (2020). Sorting yourself out of the system: Everyday processes of elusive social sorting in Australia’s disability social security regime for Indigenous Australians. Disability & Society, 35(3), 347–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1649128

- Stenhouse, R., & Tait, J. (2014). Finding our voices in the dangling conversations: Co-producing digital stories with people with dementia. In P. Hardy & T. Sumner (Eds.), Cultivating compassion: How digital storytelling is transforming healthcare (1st ed., pp. 283–296). Kingsham press.

- Stienstra, D., Baikie, G., & Manning, S. M. (2018). ‘My granddaughter doesn’t know she has disabilities and we are not going to tell her’: Navigating intersections of Indigenousness, disability and gender in Labrador. Disability in the Global South, 5(2), 1385–1406.

- Straus, S. E., Tetroe, J., & Graham, I. (2009). Defining knowledge translation. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 181(3–4), 165–168. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.081229

- Toccalino, D., Haag, H. L., Estrella, M. J., Cowle, S., Fuselli, P., Ellis, M. J., Gargaro, J., & Colantonio, A. (2022). The intersection of intimate partner violence and traumatic brain injury: Findings from an emergency summit addressing system-level changes to better support women survivors. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 37(1), E20–E29. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0000000000000743

- Townsend, C., McIntyre, M., Wright, C., Lakhani, A., White, P., & Cullen, J. (2019). Exploring the experiences and needs of homeless Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with neurocognitive disability. Brain Impairment, 20(2), 180–196. https://doi.org/10.1017/BrImp.2019.21

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). (2006). Article 23: Respect for home and the family. Retrieved December 13, 2006, from https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/article-23-respect-for-home-and-the-family.html

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. (2007, September 13). un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

- Vargas, C., Whelan, J., Brimblecombe, J., & Allender, S. (2022). Co-creation, co-design, co-production for public health: A perspective on definition and distinctions. Public Health Research & Practice, 32(2), Article e3222211. https://doi.org/10.17061/phrp3222211