?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

In recent years, there has been a growing consensus in management and organisation studies regarding the crucial role played by business model innovation in supporting firms’ competitiveness. However, the intra-organisational processes that aim to develop business model innovation and the antecedents for its conceptualisation remain underexplored. Organisational mechanisms for learning between managers lead to the establishment of intra-organisational advice networks, which facilitate the acquisition and diffusion of knowledge for innovation. Using social network analysis, this study investigates the elements associated with intra-organisational networking intended to innovate business models. We analyse a multiunit cooperative firm as a case study. Within this firm, the conceptualisation of the novel business model activated a collaborative system of advice exchange between managers. We found that networking is supported by active managers who spread advice within the firm and managers who go beyond the boundaries of their organisational role. We propose several managerial recommendations, including that managers can develop sub-groups constituting specific and unique knowledge structures, which represent the real generators of business model innovation.

Introduction

In a dynamic competitive landscape influenced by new disruptive phenomena where social changes shape customer needs, firms need to constantly renew and adapt their business models (Martins et al., Citation2015; Schneider & Spieth, Citation2013; Su et al., Citation2020). A business model refers to the designed system of activities through which a firm creates value and is considered a crucial factor in its survival and success (Zott & Amit, Citation2010). Business model innovation (BMI) represents an additional (and complementary) source of innovation compared to traditional units of analysis such as product, process and organisational innovation (Berends et al., Citation2016; Zott et al., Citation2011). In recent years, both scholars and practitioners have dedicated increased attention to BMI as a means of supporting entrepreneurial development paths and achieving above-average performance. The Business Model Canvas (BMC) (Osterwalder & Pigneur, Citation2010) has been widely applied for its effectiveness in making sense of ‘doing business’. Using this approach, cognitive maps of managers and entrepreneurs have been investigated to extend the reach of the BMC to the individual level (Keane et al., Citation2018). The BMC’s utility in entrepreneurial training activities compared to tools such as the business plan has been explored in depth (Türko, Citation2016). An effort has also been made to understand how IT infrastructure can dynamically enable alignment between business modelling and enterprise architecture to achieve the most effective combination of business model elements (Fritscher & Pigneur, Citation2015). Academic research has investigated the construct of BMI from different theoretical perspectives (Belussi et al., Citation2019; Foss & Saebi, Citation2018; Martins et al., Citation2015; Zott et al., Citation2011). Scholars in strategy (Teece, Citation2010), entrepreneurship (Osiyevskyy & Dewald, Citation2015) and innovation management (Casadesus-Masanell & Zhu, Citation2013) argue that a business model may serve as a vehicle to transfer innovation to the market but may also represent a subject of innovation per se. Hence, firms increasingly attempt to innovate their business models with either radical or incremental changes as a source of value creation and competitive advantage (Zott et al., Citation2011).

Although much of the previous research has focused on the design, execution and evolution of business models, systematic research on their antecedents is still limited (Amit & Zott, Citation2015; Berends et al., Citation2016; Foss & Saebi, Citation2018; Su et al., Citation2020; To et al., Citation2018; Zott et al., Citation2011). BMI is based on the principle that firms innovate through an organisational process that leverages internal capabilities and resources (Zott & Amit, Citation2010). Since (individual) cognition and learning are crucial components of this process, a central question is how interactions between managers – who are responsible for introducing changes in a firm – affect BMI. Previous studies have largely focused on either the cognitive or experiential dimension of the BMI process (Casadesus-Masanell & Ricart, Citation2010; Cavalcante et al., Citation2011; Zott & Amit, Citation2010), but their findings are not conclusive. According to the seminal works of Gavetti and Levinthal (Citation2000) and Levitt and March (Citation1988), the innovative process involves different learning mechanisms, while Berends et al. (Citation2016) suggest that BMI results from an iterative process involving both cognitive search and experiential learning. Zott and Amit (Citation2015) point out that the concept of innovation is closely related to the notion of design and that the design process of a new system is strictly interrelated with the concept of the business model. These authors agree with Martin (Citation2009) that design thinking is fundamental in gaining competitive advantage and that the individuals in charge of defining the novel business model (i.e., the ‘designers’) play a pivotal role within the organisation. In recent studies, these individuals (who mainly occupy managerial roles) and their social relationships have emerged as the bases for organisational learning in the BMI process, since interpersonal relationships facilitate the acquisition and diffusion of knowledge used to prepare for BMI (Osiyevskyy & Dewald, Citation2015; Schneckenberg et al., Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2017). However, these studies focus on managers’ relationships with the external environment, while other authors emphasise the role of intra-organisational collaborative networks in knowledge management and innovative processes (Aalbers & Dolfsma, Citation2017; Nakauchi et al., Citation2017). The establishment of intra-organisational advice relationships between managers provides an opportunity to exchange information and knowledge about the BMI process, thus improving its conceptualisation. Business model conceptualisation is characterised by cognitive search and refers to the ‘development of concepts, ideas, and analyses for one or more BM components or their interaction, without actually changing or creating any of the components’ (Berends et al., Citation2016, p. 189). Hence, this mechanism facilitates the development of original and unconventional ideas through the social interactions of managers. As noted by Lomi et al. (Citation2014), advice relationships are particularly important in understanding how knowledge is shared and used within firms; thus, they play a relevant role in supporting innovative activities, as in the case of conceptualising BMI. However, there are still limitations in our understanding of the drivers of these networks and their managerial implications; these limitations hinder the advancement of the BMI theoretical construct, negatively impacting managers’ understandings of the BMI process.

Following previous calls to investigate the role of networking in the emergence of BMI (e.g., Fjeldstad & Snow, Citation2018), this study uses a network approach to address the following research question: What are the main drivers of intra-organisational advice networks for conceptualising BMI? According to Lusher et al. (Citation2013), actor attribute–based and endogenous network effects are particularly relevant in network formation processes. Louch (Citation2000) states that network relationships are influenced by the presence of similarities between actors, and Lazega et al. (Citation2012) found that individuals with similar attributes had a high probability of exchanging advice. Per the definition provided by McPherson et al. (Citation2001, p. 416), ‘homophily is the principle that a contact between similar people occurs at a higher rate than among dissimilar people’. Two managers can be considered similar if they share similar personal characteristics, such as age, education and gender, or professional attributes, like tenure and organisational role. Hence, multiple forms of homophily can be observed, each influencing the propensity to exchange advice. Scholars have highlighted the importance of the second group of drivers (endogenous network effects) when analysing network structures (Lomi et al., Citation2014; Lusher et al., Citation2013) and, in particular, advice networks (Tortoriello & Krackhardt, Citation2010). These endogenous network effects are identified by sub-structures that reflect social processes like reciprocity, popularity, activity and transitivity. As mentioned by Lomi et al. (Citation2014) and Rank et al. (Citation2010), it is important to consider these effects when analysing advice networks in order to fully understand a firm’s innovative processes.

To address our research question, we apply social network analysis (SNA) to an empirical case study. SNA enables us to investigate network structures by modelling actor-level attributes and endogenous network effects. Specifically, we use exponential random graph models (ERGMs) to test whether various factors are associated with managers’ advice behaviour by analysing a multi-unit leading cooperative firm specialising in personal care services.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 illustrates the theoretical framework and network approach used in this study. The data and methodology are presented in section 3. Section 4 describes the main results, while section 5 concludes the paper.

Theoretical framework

Designing business model innovation (BMI)

Despite its importance for business researchers and practitioners, there is no clear consensus on the definition of the term ‘business model’ (Foss & Saebi, Citation2018; Zott et al., Citation2011). Amit and Zott (Citation2001, p. 501) define the business model as ‘the content, structure, and governance of transactions designed so as to create value through the exploitation of business opportunities’. For Shafer et al. (Citation2005), the business model reflects a firm’s realised strategy, which generates value through the identification of key resources and capabilities. Teece (Citation2010, p. 179) argues that the ‘business model articulates the logic, the data and other evidence that support a value proposition for the customer, and a viable structure of revenues and costs for the enterprise delivering that value’. While these definitions mainly refer to the operational dimension of a firm, BMI occurs when firms change the key elements of their architecture over time (Fjeldstad & Snow, Citation2018) and of their own initiative, not only as a consequence of developing ICT tools to support organisational changes and enhance productivity and efficiency (Belussi et al., Citation2019; Chesbrough, Citation2007). Innovating the business model reshapes a firm’s policies, creating new functional systems aligned with the external environment (Zott et al., Citation2011). However, designing BMI is not a linear process: the design process suffers from uncertainty about BMI’s effectiveness, along with a high risk of failure due to its intrinsic complexity (Berends et al., Citation2016; Zott et al., Citation2011). Scholars have analysed the main phases of the BMI process in order to understand which activities must be successfully executed to develop a novel business model (e.g., Ebel et al., Citation2016). In this vein, Evans and Johnson (Citation2013) illustrated the results of a novel approach implemented at Lockheed Martin for assessing the total risks of innovative strategies, demonstrating that, despite the challenges surrounding BMI, it is possible to create tools for evaluating investment decisions. However, the effort of shaping effective configurations becomes more uncertain when innovative business models are developed that coexist with traditional ones (Markides, Citation2013). Scholars identify barriers to BMI as resulting from resistance to changing assets and processes or from managers’ cognitive inability to understand the potential advantages of a new business model (Cavalcante et al., Citation2011; Zott et al., Citation2011). Berends et al. (Citation2016) distinguish between two fundamental modes of organisational learning: cognitive search and experiential learning. According to Im and Rai (Citation2008, p. 1284), cognitive search involves the exploration ‘of local and distant alternatives’ – that is, learning by shifting to new trajectories (Gupta et al., Citation2006). In contrast, experiential learning (or experiential search, to use the terminology adopted by Im and Rai (Citation2008)) is related to exploitation, as it ‘focuses on slow and steady improvement through alternative evaluation in the neighborhood of current activity’ (Im & Rai, Citation2008, p. 1284). These two activities are not mutually exclusive: indeed, March (Citation1991) argues that the capacity to adapt to new circumstances requires both exploitation and exploration and that a successful learning process must therefore be able to integrate elements of cognitive search and experiential learning. Cognitive search identifies a forward-looking approach wherein BMI is first conceptualised and then put into action (Tikkanen et al., Citation2005). On the other hand, experiential learning refers to a backward-looking process where past experiences drive managers’ choices among alternative action pathways. Prior behaviour is codified into routinised activities so that successful actions can be retained and failures abandoned (Levitt & March, Citation1988). Therefore, in the context of experiential learning, action precedes cognition as the source of BMI.

Although these two modes of organisational learning involve action and cognition, previous studies have emphasised that cognitive search facilitates the management of complex interactions among interdependent components (Gavetti & Levinthal, Citation2000; Martins et al., Citation2015). Gavetti and Levinthal (Citation2000) found that cognitive representations enable long jumps to distant parts of the landscape, whereas experience – acting as a backward-looking mechanism – tends to produce solutions aligned with the current behaviour. Tikkanen et al. (Citation2005) and Cavalcante et al. (Citation2011) highlight the importance of cognition in the BMI process. Managers define appropriate strategies by relying on cognitive structures such as mental models, analogies and identity (Ott et al., Citation2017; Schneckenberg et al., Citation2018). Managerial cognition is recognised as a crucial element in interpreting external challenges and opportunities and, consequently, designing new organisational processes (Fjeldstad & Snow, Citation2018; Martins et al., Citation2015; Wang et al., Citation2017).

Cognitive change may enable managers to break with existing routines and shift towards an active search for alternatives (Cavalcante et al., Citation2011; Martins et al., Citation2015; Ott et al., Citation2017). Cognition allows for off-line evaluations (i.e., managers can assess activities in which they are not engaged). The process of business planning is commonly depicted as a set of off-line activities driven by individuals’ cognition (Gavetti & Levinthal, Citation2000). The current literature underscores how cognitive structures enable managers to conceptualise the integration of different interdependent activities into an organisational business model.

Fjeldstad and Snow (Citation2018) emphasise the need for planned changes in a firm’s existing business model as a dynamic adaptation to environmental conditions and as strategic decisions made with the intention of increasing value. Several factors influence BMI: external environmental changes, organisational characteristics and intra-organisational elements, including individual attributes. According to Beckhard and Harris (Citation1977) and Hayes (Citation2002), planned change and change management address all activities carried out to transform the state of an organisation. Indeed, firms need an accurate system for planning all future activities and interventions in the process of transforming their business model. Environmental changes are constantly occurring; therefore, it is necessary to move towards a novel business model that enables prompt reactions to these changes. In describing the eight stages of a successful change process, Kotter (Citation1996) emphasises the importance of intra-organisational discussion and communication and the role of organisational culture in supporting change. Bock et al. (Citation2012, p. 282) argue that ‘culture is a critical aspect of the firm’s informal structure, and influences innovativeness’. Since resistance to change can be an issue in the innovation process, the conceptualisation and implementation of BMI requires a creative culture and a shared vision amongst managers, who need to understand the opportunities offered by innovation and move beyond their traditional beliefs about business success factors (Osiyevskyy & Dewald, Citation2015). Conceptualising BMI requires a collaborative environment intended to develop and share organisational knowledge through interpersonal interactions, which depends on a firm’s capacity to mobilise internal resources – in other words, to encourage organisational learning through the exchange of advice between individuals (Teece, Citation2010; Wang et al., Citation2017).

Advice networks and BMI conceptualisation

As previously illustrated, the collaborative environment established within a firm for conceptualising BMI depends on managers’ capacity to develop networking. More than other mechanisms based on formal procedures, conceptualising ideas and new proposals relies on informal networking, where advice exchange enables the diffusion of knowledge without constraints (Oparaocha, Citation2016). According to network theory, social interactions foster knowledge creation and use (Burt, Citation1992); with regard to organisations, individuals are the repositories of organisational knowledge, which can be used only if ‘organizational members must know who knows what, and interact with each other in order to utilize and combine knowledge’ (Cross et al., Citation2001, p. 216). Advice relationships facilitate sharing knowledge among individuals (Cross et al., Citation2001; Lomi et al., Citation2014), thereby fostering change and innovation (Kim, Citation2015). The importance of studying intra-organisational advice networks in innovation studies has been highlighted recently by several scholars, including Brennecke and Rank (Citation2017), Di Vincenzo and Mascia (Citation2017), and Christensen and Pedersen (Citation2018), among others. Rouchier et al. (Citation2014, p. 255) argue that ‘within organizations, advice networks are particularly important channels for influence’, and these networks have been deeply studied to understand ‘knowledge transmission, changes of organizational strategies, changes in attitude toward technology, and status differentials’. Intra-organisational advice networks are therefore key elements of firms’ innovative processes. Nevertheless, the establishment of advice networks does not automatically lead to successful innovative activity. As pointed out by Burt (Citation1992), redundant advice deriving from the presence of highly connected groups might lead to a locked-in situation wherein individuals do not benefit (in terms of new knowledge) from establishing additional relationships because they are overburdened by the activities pursued in their current network structure. In this vein, Wong (Citation2008) argues that knowledge overlap is positively related to high intra-group network density; however, Alexiev et al. (Citation2010) claim that heterogeneity in managerial groups should reduce the ‘redundancy effect’ due to the presence of managers with similar prior knowledge. At the same time, being connected with few actors is risky: if relationships can be easily broken, there may be a disruption in the network structure, leading to reduced ability to exchange knowledge and therefore produce innovation. Intermediaries in innovation (Howells, Citation2006) play a crucial role in accelerating (or reducing) the diffusion of innovation. Being connected with one of these intermediaries can be beneficial, but if the connection vanishes, it could be problematic for the innovation process.

Advice networks that aim to conceptualise BMI are not immune to these problems. However, the need for a collaborative environment wherein individuals have multiple interactions overcomes the risk of possible inefficiencies due to redundancy, at least in the early stages of BMI conceptualisation; thus, business model ideas require interactions between individuals (Eppler & Hoffmann, Citation2012). Spreading internal advice among managers is valuable for a firm because doing so enhances innovative performance (Aalbers & Dolfsma, Citation2017): it is thus fundamental for conceptualising new business models. Berends et al. (Citation2016) argue that the conceptualisation process can be described as ‘learning-before-doing’, which is congruent with the idea of relying on knowledge acquired from other individuals (and thus activating a learning process) in advice exchange. Advice relations support the diffusion of intra-organisational knowledge, providing information for problem-solving, activating tacit knowledge in specific units or sub-units and encouraging the exchange of opinions (Lomi et al., Citation2014). These activities lead to the acquisition and internal re-elaboration of knowledge, enabling the development of BMI through the reconfiguration of organisational practices and capabilities (Foss et al., Citation2011).

Drivers of advice networks

Advice networks are often driven by individual attributes and endogenous network effects. Managers’ attributes influence the innovation process, fostering coopetition between units and increasing overall managerial performance (Yuan et al., Citation2014). Studies on intra-organisational advice networks have demonstrated the importance of homophily in shaping interpersonal advice relationships (Agneessens & Wittek, Citation2012; Lazega et al., Citation2012; Louch, Citation2000; Soda & Zaheer, Citation2012). Homophily is a phenomenon describing a situation in which individuals with similar attributes tend to interact more frequently than they would by chance (McPherson et al., Citation2001). Personal characteristics such as age, education, and gender are usually considered individual attributes along with attributes related to professional characteristics such as tenure and organisational role (Agneessens & Wittek, Citation2012; Lomi et al., Citation2014). Tenure is positively associated with the development of innovative capabilities (Reichheld & Teal, Citation2001), and Fleming et al. (Citation2007) and Soda and Zaheer (Citation2012) argue that advice relationships intended to promote innovative activities are influenced by the careers of individuals within a firm. Moreover, Pahor et al. (Citation2008) found that tenure homophily positively influences the development of social relations between individuals in organisations. Agneessens and Wittek (Citation2012) argue that individuals’ organisational roles influence intra-organisational advice, leading to an informal network structure that could differ from the formal hierarchical structure. This affects interpersonal channels of communication because informal relationships are nevertheless negatively influenced by status recognition, as ‘members of higher status may not want to lose status by seeking advice from colleagues ‘below them’ in the formal hierarchy’ (Lazega et al., Citation2012, p. 324).

In addition to homophily, endogenous network effects are equally important in the analysis of intra-organisational advice networks (Rank et al., Citation2010). These effects represent social features such as reciprocity, popularity, activity and transitivity, which support interpersonal social relations that aim to share knowledge related to the conceptualisation of innovative activities and processes (Lomi et al., Citation2014). Network theory identifies these effects with specific network configurations called subgraphs ‘that may represent a local regularity in social network structure’ (Lusher et al., Citation2013, p. 17), composed of dyads (pairs of actors) or triads (groups of three actors). In directed networks, reciprocity occurs when the exchange of advice between two actors is reciprocal. Managers’ advice networks can benefit from a high level of reciprocal exchanges, which increase trust (Burt, Citation1992) and pave the way for the establishment of new relationships in the future. Popularity and activity refer to two opposite social mechanisms: in advice networks, the former indicates the degree to which an actor can attract advice from others, while the latter indicates the actor’s capacity to spread advice through the network. In SNA, these effects are termed ‘in-degree’ and ‘out-degree’, respectively. Finally, transitivity explains ‘the nature of connections between individuals’ (Louch, Citation2000, p. 48) by highlighting the ‘tendency for hierarchical path closure’ in a network (Lusher et al., Citation2013, p. 44). Two individuals are expected to establish a relationship if they already have a connection with a third individual. This is the same principle expressed by the balance theory (Cartwright & Harary, Citation1956): if individual A is friends with individual B, and individual B is friends with individual C, there may be a tendency for C to become a friend of A. In the context of advice exchange for conceptualising BMI, this means that managers’ decisions to provide advice to others are driven by their potential connections with ‘advisors of advisors’.

While reciprocity, popularity and activity control the degree distribution of the network, transitivity accounts for the possibility to shape intra-organisational network clusters between individuals (Lomi et al., Citation2014). Exchanging advice for conceptualising BMI benefits from both activities: the more managers are involved in trustworthy relations, the more easily knowledge flows within the firm. Moreover, the presence of managers actively involved in the diffusion and collection of knowledge supports dialogue and the understanding of the ongoing innovative process shaping the business model (Osterwalder & Pigneur, Citation2010).

Data and methodology

Research site

This study was conducted on a multi-unit leading cooperative firm specialising in personal care services that serves over 7,000 people on a daily basis in seven Italian regions in the elderly, disabled, child, minor and healthcare sectors. The firm has a total of 140 low, middle and top managers, including the president. These managers’ formal organisational roles include coordinators, specialists, project managers, managers in charge of organisation, senior managers in charge of production and directors. These managers are organised by service (three macro-areas: education, health and well-being) and working location (Italian regions and provinces). Low- to middle-level managers (coordinators and specialists) have high autonomy in defining the implementation and adoption of new practices and activities in their area of interest. Top management considers sharing opinions and engaging managers in the decision-making process to be a key feature of the firm, whose cooperative structure implies participation and strong organisational commitment (Nilsson, Citation2001). In 2016, the firm started the process of designing a novel business model intended to support the introduction of new health services and, at the same time, enter new market niches by directly managing nursing homes. This process required a change in organisational processes, and managers have been involved in and encouraged to contribute to the business model design and implementation.

Data collection

In spring 2017, we defined the research proposal to be submitted to the firm and organised a preliminary meeting with the president and the chief of the human resources (HR) department to present our research project. In the autumn of the same year, we organised two meetings with the chief of the HR department to determine the objective of the study, define the data collection process (which would take place via an online questionnaire) and address privacy issues. We then presented the project to top managers and to the managers responsible for each organisational unit, since we agreed with the chief of the HR department that these individuals would be responsible for encouraging their subordinates to complete the questionnaire. On this occasion, we presented a video tutorial on how to complete the questionnaire in order to aid comprehension.

Once the formal agreement for the data collection process was made, we created an online platform for the questionnaire and mailed invitations to complete it to the 140 managers. The data collection process began in December 2017 and ended in February 2018. The questionnaire included sociodemographic, professional and relational questions. The sociodemographic and professional questions asked respondents to indicate their age, role within the organisation, education level, tenure and professional experience. We collected relational data using the roster method (Wasserman & Faust, Citation1994) by listing all 140 managers in a single table and asking respondents to indicate, for each manager, whether they had received or sent advice intended to conceptualise BMI. Specifically, we used the following question: ‘Please tick the box corresponding to the manager with whom you have exchanged advice (sent or received) in the last year for developing concepts or ideas concerning one or more components of the business model, even if no changes have followed’. We then stored this information in a binary adjacency matrix where the value of a cell is one if two managers exchanged advice on the conceptualisation of BMI and is zero otherwise. In total, we received 102 surveys, representing a 73% response rate.

Methodology

In this study, we use SNA to investigate the drivers associated with intra-organisational advice networking. SNA uses analytical techniques to uncover the social structures between the actors in a network and understand how these structures influence their behaviour (Wasserman & Faust, Citation1994). Since we are interested in the antecedents of networking, we apply ERGMs to our network data. ERGMs are used to analyse relational systems in which actors are linked via complex interdependencies. The main problem with network data is related to the data structure: by definition, observations are non-independent because the presence of a relation (tie) between two actors may influence other relations in the network, and classical econometric models fail to provide a consistent estimation (Robins et al., Citation2007). ERGMs overcome this problem and at the same time can include actor attributes and endogenous network effects to model the probability distribution of networks. The general form for an ERGM is as follows (Lusher et al., Citation2013):

The probability that the observed network y is identical to the randomly generated network Y is given by an exponential model assuming that ƞB is the parameter corresponding to network configuration B and gB(y) is the network statistic corresponding to configuration B. k is a normalising quantity ensuring a proper probability distribution of the ERGM. If network relationships are not randomly created but follow an underlying pattern, ERGMs can detect whether changes in relationships are associated with actor attributes and endogenous network effects. In this study, parameters were estimated using Markov chain Monte Carlo maximum likelihood estimation (Robins et al., Citation2007).

ERGMs can be applied to both directed and undirected networks. Directed networks are characterised by directed ties, where the relation between two actors has a direction flow (for example, a transfer of physical resources or information), while undirected networks are composed of ties that do not have a direction flow, as in the case of family relationships. Since advice flows have a direction (e.g., from manager i to manager j), the network data square matrix used to input the observed network y in the ERGM is not symmetric.

Since we are interested in investigating the effects of attribute-based processes and endogenous network effects on tie formation, we estimated three ERGMs: Model 1 includes only (attribute-based) homophily effects as variables; Model 2 includes only endogenous network effects; and Model 3 includes all variables from both categories. This approach separately estimates the parameters for each group of variables (Models 1 and 2) in order to understand which are positively (or negatively) associated with tie formation independent of the other group, then estimates a model (Model 3) that is comprehensive of all variables to simultaneously examine their relevance. Age_diff (age difference between two managers) and Tenure_diff (tenure difference between two managers) control for differences in age and tenure that could hamper the propensity to exchange advice; since these are continuous variables, they were calculated in terms of difference in years. Similarities in terms of organisational role (Role_match), education (Educ_match) and gender (Gender_match) are included as homophily effects by matching pairs of managers according to these characteristics. Regarding endogenous network effects (), we use Edge to control for the baseline propensity to form a tie, similar to the intercept in econometric regression models (Lusher et al., Citation2013). We expect a negative value for the parameter associated with this effect, since the marginal benefit of creating connections with other actors declines over the long term as the costs of maintaining these connections increase. We use Mutual to model the tendency towards reciprocation in advice: a positive value indicates a positive association between mutual exchange of advice and tie formation, while a negative value suggests the opposite. AinS and AoutS are used to control for popularity and activity effects, respectively; positive values for these parameters confirm the association between popular (active) managers and receiving (sending) advice with tie formation. Finally, 2-path shows whether there is an association between the presence of managers who ‘bridge’ disconnected individuals and tie formation.

Table 1. Structural effects (and related visual configurations) included in the ERGMs

The analysis (including estimates and goodness-of-fit diagnostics) was conducted using the software PNet (Wang et al., Citation2009). The goodness-of-fit assessment follows the procedure of Hunter et al. (Citation2008): a model converges if the t ratios have an absolute value close to zero or at least less than two. Goodness-of-fit diagnostics are included in the Appendix.

Results

shows the main descriptive statistics for the respondents. Managers were mainly women (77%), were on average 45 years old and had spent around 11 years working at the case study firm. Coordinators accounted for the majority of respondents (51.96%), and individuals overall had very high education levels: 28.43% had a BSc or MSc in humanities and 25.49% had a PhD or a medical specialisation.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics

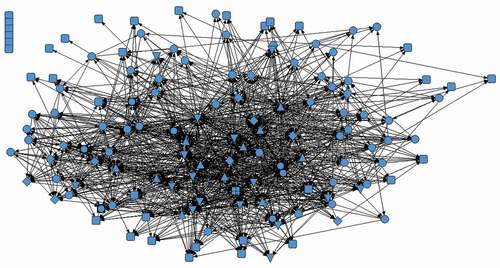

shows the advice network. A group of top managers (mainly directors and managers in charge of organisational function) are clustered into a central cloud wherein advice exchange is particularly intense. The outer ring of the advice network includes low and middle managers (especially coordinators) with operative duties.

Figure 1. Advice network

The results of the analysis are illustrated in . As described in the methodology section, we estimated three different ERGMs: Model 1 includes homophily effects only, Model 2 examines endogenous network effects and Model 3 considers both effects. The estimated coefficients of the parameters reflect the change in the log-odds likelihood of a tie per unit change in the predictors (i.e., the exponential function is used for conversion into a probability).

Table 3. ERGMs results for the advice network to conceptualise the BMI

The value of the rate parameter (Edge) is negative and statistically significant in all models. This result confirms that networks are sparse and establishing new advice relations is costly; therefore, managers tend to reduce the number of relationships to avoid advice overload. Model 1 shows a positive estimate for gender homophily and a negative estimate for organisational role homophily, while the parameter for Tenure_diff is negative, meaning that managers with similar tenures are more prone to exchanging advice. This effect acknowledges that long-term managers are endowed with a set of capabilities that favour innovative activities; however, this requires the creation of relationships with equally expert managers. On the other hand, age (Age_diff) and education (Educ_match) are not statistically significant, suggesting that these individual attributes have no significant impact on networking. These results confirm the findings of Lomi et al. (Citation2014) and Pahor et al. (Citation2008) but contradict Lazega et al.’s (Citation2012) assumption of status awareness when considering the impact of organisational role homophily. Indeed, the presence of advice relationships between managers with similar organisational roles is negatively associated with tie formation. However, this finding is supported by the work of Rank et al. (Citation2010), who argue that network ties resulting from formal authority relationships can be replaced as a governance mechanism by other social networks, like friendship; hence, formal governance structures are not a strong constraint with regard to sharing information about BMI.

Model 2 illustrates the associations of reciprocity, popularity, activity and transitivity with tie formation. Reciprocity (Mutual) does not have a significant effect; therefore, we cannot assume that the establishment of advice exchange is associated with reciprocal relationships between managers. The popularity effect (AinS) is also not statistically significant, while the odds of activity (AoutS) exceed the odds of no activity, indicating that individuals receiving advice from others play an important role. Moreover, the 2-path configuration is negative, which supports the previous findings for AinS and AoutS: managers who send advice are not those who receive advice. Rather, there is a clear separation between these two categories. The transitivity effect has a significant and positive impact on tie formation: all else being equal, transitive closure is more likely to be observed in tie formation than not.

Model 3 integrates the previous models into a single ERGM. In this model, none of the homophily effects are significant, and the endogenous network effects show similar results. The influence of the intra-organisational social processes of activity and transitivity overcomes the effects of homophily on networking. Similarity shapes individual choices: however, a network’s structural properties are more important in advice exchange, since their interaction totally undoes the significance of gender, tenure and organisational role homophily. Hence, we can assume that social processes like activity and transitivity, which lead to the creation of sub-groups in a firm’s network, are stronger than similarities (or differences) in terms of gender, tenure and organisational role, while the lack of significance of reciprocal relationships (Mutual) indicates that we cannot assume a trust-based process in the development of these sub-groups.

Discussion

The conceptualisation of BMI can be understood in depth by examining the intra-organisational advice networks among a firm’s managers, who are vehicles of knowledge diffusion for supporting innovative activities (Cross et al., Citation2001; Lomi et al., Citation2014). Foss and Saebi (Citation2018) emphasise managers’ crucial role in innovating the business model. They suggest that BMI poses managerial challenges and thus different interventions are required. Management sometimes serves as a central monitor to ensure that the BMI is consistent with the firm’s core activities, while sometimes it is actively involved in the design and experimentation of complex BMI. Our findings, in line with previous literature (Lomi et al., Citation2014; Yuan et al., Citation2014), confirm that managers, when exchanging advice to conceptualise a novel business model, establish relationships that exceed the boundaries of their hierarchical role. Moreover, this research contributes to advancing our understanding of BMI by shedding light on how the behaviour of managers relates to specific network configurations. Active managers (i.e., those who spread advice to other managers) play a key role in the dissemination of knowledge, and the same applies to the development of transitive processes for interpersonal advice. These processes can lead to the creation of sub-groups that constitute specific and unique knowledge structures representing the real foci of innovation in the business model. Depending on the identities of the central actors, their roles and skills and, above all, the composition of their sub-groups, different strategic directions and content can be generated in the BMI process. Therefore, we argue that it is necessary to focus on the analysis of managerial sub-groups and their structural characteristics to achieve an in-depth understanding of the innovation of a business model. As a practical implication, firms can enhance the conceptualisation process of BMI by supporting the ‘dissemination’ activities of specific actors (the most active from a networking perspective) and providing managers with opportunities to interact in small groups led by these actors. These groups should not be created based on formal roles or the hierarchical structure of the firm but other individual skills, such as the capability to spread knowledge for innovation.

This study contributes to the literature on BMI in several ways. First, it adopts a network approach to investigate how intra-organisational processes drive the conceptualisation of BMI. Since BMI is a complex and non-linear process (Zott et al., Citation2011) led by managers involved in strategic and operating activities, the development of interpersonal networks plays a relevant role in its creation, as it supports the diffusion of knowledge between decision-makers. Therefore, our findings provide useful insights for understanding intra-organisational features associated with the conceptualisation of BMI.

Second, this work focuses on the advice network structure underlying the conceptualisation of BMI. Although previous research has investigated the organisational learning mechanisms through which firms innovate their business models (Berends et al., Citation2016), gaps in the literature remain regarding how these mechanisms work; moreover, the role of advice networks, which are a relevant component in fostering innovation (Lazega et al., Citation2012), has been neglected. An intra-organisational advice network can increase knowledge diversity (Oparaocha, Citation2016) and allow for greater individual autonomy while reducing social pressure to conform; therefore, managers are free to elaborate and submit original and disruptive ideas, rather than generating proposals in a closed hierarchical setting.

Third, we contribute to the advancement of recent research streams on the micro-foundations of intra-organisational networks (Tasselli et al., Citation2015). We found that an open collaboration between different organisational levels is positively associated with advice exchange, which supports the idea that formal hierarchical structures should not be a strong constraint on innovative activities. In addition, the presence of active managers and trustworthy relationships between ‘advisors of advisors’ is fundamental for networking; advice relationships result in low search effort because of the activity of pivotal actors, which creates a path for managers to reach others and disseminate their ideas. Therefore, more (informal) opportunities and occasions for sharing knowledge could be provided to support collaborative activities.

The design of a new business model in a framework characterised by a cooperative background requires broader inclusion of all managers in the decision-making process. Therefore, although managers who share similar values and interests usually tend to create their own groups, managers engaged in the conceptualisation of BMI should not be partitioned, and it might be relevant to support more heterogeneous networks. These results empirically support the findings of Ott et al. (Citation2017) and Martins et al. (Citation2015), who point out that innovativeness is driven by processes of generative cognition; furthermore, they advance the extant research addressing how firms should adapt to create conditions for collaboration that in turn feed the conceptualisation of BMI (Fjeldstad et al., Citation2012).

Conclusions

This study responds to recent calls for research to advance the theoretical understanding of the BMI process (Berends et al., Citation2016; Cavalcante et al., Citation2011; Foss & Saebi, Citation2018). In recent years, the interest in BMI has grown exponentially; however, it has been highlighted the persistence of theoretical limitations and ambiguity that affect understanding of the topic (e.g., Casadesus-Masanell & Ricart, Citation2010; Geissdoerfer et al., Citation2018). As pointed out by Amit and Zott (Citation2015), the design of novel business models has become a relevant topic for scholars and practitioners, and it is necessary to deeply investigate its antecedents to ensure success in its implementation.

We contribute to filling the gap in the extant literature by focusing on the role of intra-organisational advice networks. Our work addresses an important issue in the antecedents of BMI, and our results show that networking is established between managers at different levels. This is indicative of the presence of informal relational structures wherein managers activate sub-groups that represent the real generators of innovation in the business model.

Our work provides insights to practitioners about the importance of intra-organisational network structures when conceptualising a novel business model. Our findings can support firms involved in this process, who may be interested in ‘structuring’ the informal sub-groups that arise to manage new challenges, thus improving the efficiency of their internal processes for achieving BMI. New organisational forms can be designed to strengthen internal networking with the aim of making resources available to a large set of self-organised actors (Fjeldstad et al., Citation2012). New designs are possible through organisational actors’ abilities to develop collaborative relationships, which may shift organisational structures from hierarchical to actor-oriented forms.

This study represents a first attempt to investigate the drivers associated with intra-organisational advice networks that aim to conceptualise BMI. It faces three main limitations. First, this research is based on a single case study; as such, the generalisability of our results is limited. The societal structure of the cooperative firm could have been an additional factor influencing the internal networking process; indeed, the internal organisation of cooperative firms operating in the provision of social services is inherently different from that of high-tech manufacturing companies or financial consultancies. Our work confirms that individuals involved in innovation activities can overcome the boundaries imposed on their roles; however, it is not clear what would happen if the advice-seeking process were limited to a restricted circle of top managers, which might occur in companies that are not structured in such a cooperative manner. Future research should investigate network drivers in other large firms operating in different sectors in order to investigate whether societal structure can play a role in networking. Second, perceptions of advice exchange vary across individuals. Moreover, individuals tend to forget advice that they do not consider relevant, leading to problems related to misunderstanding and memory omission. Since these are common problems in empirical network studies, we attempted to overcome them by specifying in the questionnaire 1) a definition of what we meant by the term ‘advice exchange’ and 2) the exact time period in which exchanges took place. Third, despite the high response rate, our analysis does not provide information on whether the advice exchanged between managers had an actual effect on their decisions regarding BMI. Future research should analyse the quality of the advice – that is, the type of information shared within the organisation and how it is supported and conveyed by managers. This could offer a new perspective on how final decisions are influenced by ‘lobbying’ activities. In this vein, a longitudinal study could provide new insights into the evolution of advice networks and their effects on the adoption of specific features of the novel business model. Longitudinal network data can be collected in multiple time waves (Snijders et al., Citation2010) during the implementation of BMI using the same data collection scheme adopted in this study. However, the question related to advice exchange should be modified to include more options regarding the type of advice exchanged between managers. A mixed-methods approach based on stochastic actor-oriented models for directed networks, which can be used to undertake a quantitative analysis of ties evolution, and a qualitative investigation based on interviews can provide a deeper understanding of the success (or failure) of certain ideas during the process of BMI conceptualisation and how this translates into specific actions pursued in the implementation phase.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (142 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

References

- Aalbers, R., & Dolfsma, W. (2017). Improving the value-of-input for ideation by management intervention: An intra-organizational network study. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 46(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jengtecman.2017.10.006

- Agneessens, F., & Wittek, R. (2012). Where do intra-organizational advice relations come from? The role of informal status and social capital in social exchange. Social Networks, 34(3), 333–345. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2011.04.002

- Alexiev, A. S., Jansen, J. J. P., Van den Bosch, F. A. J., & Volberda, H. W. (2010). Top management team advice seeking and exploratory innovation: The moderating role of TMT heterogeneity. Journal of Management Studies, 47(7), 1343–1364. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00919.x

- Amit, R., & Zott, C. (2001). Value creation in e-business. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6–7), 493–520. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.187

- Amit, R., & Zott, C. (2015). Crafting business architecture: The antecedents of business model design. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 9(4), 331–350. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1200

- Beckhard, R., & Harris, D. (1977). Organization transitions: Managing complex change. Addison-Wesley.

- Belussi, F., Orsi, L., & Savarese, M. (2019). Mapping business model research: A document bibliometric analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 35(3), 101048. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2019.101048

- Berends, H., Smits, A., Reymen, I., & Podoynitsyna, K. (2016). Learning while (re)configuring: Business model innovation processes in established firms. Strategic Organization, 14(3), 181–219. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127016632758

- Bock, A. J., Opsahl, T., George, G., & Gann, D. M. (2012). The effects of culture and structure on strategic flexibility during business model innovation. Journal of Management Studies, 49(2), 279–305. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2011.01030.x

- Brennecke, J., & Rank, O. (2017). The firm’s knowledge network and the transfer of advice among corporate inventors – A multilevel network study. Research Policy, 46(4), 768–783. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2017.02.002

- Burt, R. S. (1992). Structural holes: The social structure of competition. Harvard University Press.

- Cartwright, D., & Harary, F. (1956). Structural balance: A generalization of Heider’s theory. Psychological Review, 63(5), 277–293. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/h0046049

- Casadesus-Masanell, R., & Ricart, J. E. (2010). From strategy to business models and onto tactics. Long Range Planning, 43(2–3), 195–215. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2010.01.004

- Casadesus-Masanell, R., & Zhu, F. (2013). Business model innovation and competitive imitation: The case of sponsor-based business models. Strategic Management Journal, 34(4), 464–482. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2010.01.004

- Cavalcante, S., Kesting, P., & Ulhøi, J. P. (2011). Business model dynamics and innovation: (Re)establishing the missing linkages. Management Decision, 49(8), 1327–1342. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741111163142

- Chesbrough, H. (2007). Business model innovation: It’s not just about technology anymore. Strategy and Leadership, 35(6), 12–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/10878570710833714

- Christensen, H. P., & Pedersen, T. (2018). The dual influences of proximity on knowledge sharing. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(8), 1782–1802. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-03-2018-0211

- Cross, R., Borgatti, S. P., & Parker, A. (2001). Beyond answers: Dimensions of the advice network. Social Networks, 23(3), 215–235. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8733(01)00041-7

- Di Vincenzo, F., & Mascia, D. (2017). Knowledge development and advice networks in professional organizations. Knowledge Management Research and Practice, 15(2), 201–213. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/s41275-017-0049-7

- Ebel, P., Bretschneider, U., & Leimeister, J. M. (2016). Leveraging virtual business model innovation: A framework for designing business model development tools. Information Systems Journal, 26(5), 519–550. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12103

- Eppler, M. J., & Hoffmann, F. (2012). Does method matter? An experiment on collaborative business model idea generation in teams. Innovation: Organization & Management, 14(3), 388–403. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5172/impp.2012.14.3.388

- Evans, J. D., & Johnson, R. O. (2013). Tools for managing early-stage business model innovation. Research-Technology Management, 56(5), 52–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5437/08956308X5605007

- Fjeldstad, Ø. D., Snow, C. C., Miles, R. E., & Lettl, C. (2012). The architecture of collaboration. Strategic Management Journal, 33(6), 734–750. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.1968

- Fjeldstad, Ø. D., & Snow, C. S. (2018). Business models and organization design. Long Range Planning, 51(1), 32–39. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2017.07.008

- Fleming, L., Mingo, S., & Chen, D. (2007). Collaborative brokerage, generative creativity, and creative success. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(3), 443–475. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.52.3.443

- Foss, N. J., Laursen, K., & Pedersen, T. (2011). Linking customer interaction and innovation: The mediating role of new organizational practices. Organization Science, 22(4), 980–999. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0584

- Foss, N. J., & Saebi, T. (2018). Business models and business model innovation: Between wicked and paradigmatic problems. Long Range Planning, 51(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2017.07.006

- Fritscher, B., & Pigneur, Y. (2015). A visual approach to business IT alignment between business model and enterprise architecture. International Journal of Information System Modeling and Design, 6(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4018/ijismd.2015010101

- Gavetti, G., & Levinthal, D. (2000). Looking forward and looking backward: Cognitive and experiential search. Administrative Science Quarterly, 45(1), 113–137. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2666981

- Geissdoerfer, M., Vladimirova, D., Van Fossen, K., & Evans, S. (2018). Product, service, and business model innovation: A discussion. Procedia Manufacturing, 21(1), 165–172. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2018.02.107

- Gupta, A. K., Smith, K. G., & Shalley, C. E. (2006). The interplay between exploration and exploitation. Academy of Management Journal, 49(4), 693–706. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2006.22083026

- Hayes, J. (2002). The theory and practice of change management. Palgrave.

- Howells, J. (2006). Intermediation and the role of intermediaries in innovation. Research Policy, 35(5), 715–728. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2006.03.005

- Hunter, D., Goodreau, S., & Handcock, M. (2008). Goodness of fit of social network models. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 103(481), 248–258. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1198/016214507000000446

- Im, G., & Rai, A. (2008). Knowledge sharing ambidexterity in long-term interorganizational relationships. Management Science, 54(7), 1281–1296. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1080.0902

- Keane, S. F., Cormican, K. T., & Sheahan, J. N. (2018). Comparing how entrepreneurs and managers represent the elements of the business model canvas. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 9(1), 65–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2018.02.004

- Kim, T. (2015). Diffusion of changes in organizations. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 28(1), 134–152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-04-2014-0081

- Kotter, J. P. (1996). Leading change. Harvard Business School Press.

- Lazega, E., Mounier, L., Snijders, T., & Tubaro, P. (2012). Norms, status and the dynamics of advice networks: A case study. Social Networks, 34(3), 323–332. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2009.12.001

- Levitt, B., & March, J. G. (1988). Organizational learning. Annual Review of Sociology, 14(1), 319–340. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.14.080188.001535

- Lomi, A., Lusher, D., Pattison, P. E., & Robins, G. (2014). The focused organization of advice relations: A study in boundary crossing. Organization Science, 25(2), 438–457. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2013.0850

- Louch, H. (2000). Personal network integration: Transitivity and homophily in strong-tie relations. Social Networks, 22(1), 45–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8733(00)00015-0

- Lusher, D., Koskinen, J., & Robins, G. (2013). Exponential random graph models for social networks: Theory, methods, and applications. Cambridge University Press.

- March, J. G. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 71–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2.1.71

- Markides, C. C. (2013). Business model innovation: What can the ambidexterity literature teach us? The Academy of Management Perspective, 27(4), 313–323. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2012.0172

- Martin, R. (2009). Design of business: Why design thinking is the next competitive advantage. Harvard Business Review Press.

- Martins, L. L., Rindova, V. P., & Greenbaum, B. E. (2015). Unlocking the hidden value of concepts: A cognitive approach to business model innovation. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 9(1), 99–117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1191

- McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 415–444. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415

- Nakauchi, M., Washburn, M., & Klein, K. (2017). Differences between inter- and intra-group dynamics in knowledge transfer processes. Management Decision, 55(4), 766–782. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-08-2016-0537

- Nilsson, J. (2001). Organisational principles for co-operative firms. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 17(3), 329–356. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0956-5221(01)00010-0

- Oparaocha, G. O. (2016). Towards building internal social network architecture that drives innovation: A social exchange theory perspective. Journal of Knowledge Management, 20(3), 534–556. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-06-2015-0212

- Osiyevskyy, O., & Dewald, J. (2015). Explorative versus exploitative business model change: The cognitive antecedents of firm-level responses to disruptive innovation. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 9(1), 58–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1192

- Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business model generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. Wiley.

- Ott, T. E., Eisenhardt, K. E., & Bingham, C. B. (2017). Strategy formation in entrepreneurial settings: Past insights and future directions. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 11(3), 306–325. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1257

- Pahor, M., Škerlavaj, M., & Dimovski, V. (2008). Evidence for the network perspective on organizational learning. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 59(12), 1985–1994. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20912

- Rank, O. N., Robins, G. L., & Pattison, P. E. (2010). Structural logic of intraorganizational networks. Organization Science, 21(3), 745–764. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0450

- Reichheld, F. F., & Teal, T. (2001). The loyalty effect: The hidden force behind growth, profits, and lasting value. Harvard Business School Press.

- Robins, G., Pattison, P., Kalish, Y., & Lusher, D. (2007). An introduction to exponential random graph (p*) models for social networks. Social Networks, 29(2), 173–191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2006.08.002

- Rouchier, J., Tubaro, P., & Emery, C. (2014). Opinion transmission in organizations: An agent-based modeling approach. Computational and Mathematical Organization Theory, 20(3), 252–277. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10588-013-9161-2

- Schneckenberg, D., Velamuri, V., & Comberg, C. (2018). The design logic of new business models: Unveiling cognitive foundations of managerial reasoning. European Management Review, 16(2), 427–447. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12293

- Schneider, S., & Spieth, P. (2013). Business model innovation: Towards an integrated future research agenda. International Journal of Innovation Management, 17(1), 1340001. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1142/S136391961340001X

- Shafer, S. M., Smith, H. J., & Linder, J. (2005). The power of business models. Business Horizons, 48(3), 199–207. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2004.10.014

- Snijders, T. A. B., van de Bunt, G. G., & Steglich, C. E. G. (2010). Introduction to stochastic actor-based models for network dynamics. Social Networks, 32(1), 44–60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2009.02.004

- Soda, G., & Zaheer, A. (2012). A network perspective on organizational architecture: Performance effects of the interplay of formal and informal organization. Strategic Management Journal, 33(6), 751–771. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.1966

- Su, J., Zhang, S., & Ma, H. (2020). Entrepreneurial orientation, environmental characteristics and business model innovation: A configurational approach. Innovation: Organization & Management, 22(4), 399–421. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14479338.2019.1707088

- Tasselli, S., Kilduff, M., & Menges, J. I. (2015). The microfoundations of organizational social networks: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Management, 41(4), 1361–1387. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315573996

- Teece, D. J. (2010). Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Planning, 43(2–3), 172–194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.003

- Tikkanen, H., Lamberg, J., Parvinen, P., & Kallunki, J. (2005). Managerial cognition, action and the business model of the firm. Management Decision, 43(6), 789–809. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740510603565

- To, C. K. M., Au, J. S. C., & Kan, C. W. (2018). Uncovering business model innovation contexts: A comparative analysis by fsQCA methods. Journal of Business Research, 101(1), 783–796. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.12.042

- Tortoriello, M., & Krackhardt, D. (2010). Activating cross-boundary knowledge: The role of Simmelian ties in the generation of innovations. Academy of Management Journal, 53(1), 167–181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.48037420

- Türko, E. S. (2016). Business plan vs. business model canvas in entrepreneurship trainings: A comparison of students’ perceptions. Asian Social Science, 12(10), 55–62. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v12n10p55

- Wang, D., Guo, H., & Liu, L. (2017). One goal, two paths: How managerial ties impact business model innovation in a transition economy. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 30(5), 779–796. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-09-2016-0178

- Wang, P., Robins, G., & Pattison, P. (2009). PNet: Program for the simulation and estimation of exponential random graph models. University of Melbourne: Melbourne School of Psychological Sciences.

- Wasserman, S., & Faust, K. (1994). Social network analysis: Methods and applications. Cambridge University Press.

- Wong, S. S. (2008). Task knowledge overlap and knowledge variety: The role of advice network structures and impact on group effectiveness. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29(5), 591–614. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.490

- Yuan, X., Guo, Z., & Fang, E. (2014). An examination of how and when the top management team matters for firm innovativeness: The effects of TMT functional backgrounds. Innovation: Management Policy & Practice, 16(3), 323–342. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14479338.2014.11081991

- Zott, C., & Amit, R. (2015). Business model innovation: Toward a process perspective. In C. E. Shalley, M. A. Hitt, & J. Zhou (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship (pp. 395–406). Oxford University Press.

- Zott, C., & Amit, R. (2010). Business model design: An activity system perspective. Long Range Planning, 43(2), 216–226. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.004

- Zott, C., Amit, R., & Massa, L. (2011). The business model: Recent developments and future research. Journal of Management, 37(4), 1019–1042. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311406265