ABSTRACT

Servitisation, which occurs when products are offered with service components as product-service bundles, has increased rapidly in consumer markets during recent years because of digitalisation. Digital technologies have enabled the emergence of peer-to-peer marketplaces and made it possible for B2B lease and rental actors to push for B2C markets. Despite extensive research on servitisation, we know little of what kinds of companies can best exploit the opportunities created by it and how digitalisation affects inter-company relationships regarding these opportunities. This article addresses these research gaps by making a revelatory case study on the entry order and strategy of established B2B lease companies to enter the B2C private leasing and carsharing markets. We collect an interview-based dataset on key companies in the Dutch car lease market, that we analyse abductively. We find that knowledge of the opportunities, position in the value chain, and resources are focal elements that define which companies are pioneers, early followers, and late entrants. In contrast to former servitisation literature, manufacturing incumbent companies are not active in exploiting opportunities created by private leasing. Additionally, we discover that the leasing companies create capabilities for private leasing themselves whereas they partner to enable carsharing. We discuss the contribution of these findings to research on disruptive innovation, servitisation, and digital innovation.

Introduction

Digital innovation has disrupted many markets through the reconfiguration of business models. Among the industries affected are both product industries (camera, car manufacturing, music, telephone) and services industries (information search, media, retail, television, tourism, and transportation) (Kenney & Zysman, Citation2016; Nambisan et al., Citation2017). Many incumbents have lost their leading positions because of difficulties to adapt their capabilities and business models. Against the background of ongoing digitalisation during the past three decades, a rich literature has emerged in innovation studies on the organisational consequences of the introduction of new business models for incumbents (Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, Citation2013; Christensen & Raynor, Citation2003; Tripsas & Gavetti, Citation2000).

Two types of contexts are distinguishable in the current business model literature. First, some studies look at a new business model for a given set of customers (e.g., Tripsas & Gavetti, Citation2000). Here, the question is how incumbent companies can deal with the introduction of a new business model that reaches out to their existing customer base. Second, some studies look at the introduction of a new business model for a new set of customers (e.g., Christensen & Raynor, Citation2003). Here, the key question holds under what conditions incumbents can maintain their lead or instead are disrupted by startups, for example, once a niche market extends to the masses. As these business model studies are mostly examining the introduction of new business models in business-to-consumer (B2C) contexts, they ignore the current trend partially stimulated by digitalisation: boundaries between business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-consumer (B2C) markets are diminishing.

In an attempt to grapple with digitalisation, traditional B2B companies attempt to follow e-commerce companies and move into B2C markets, thus bypassing traditional intermediaries. Examples include airlines bypassing travel agencies, computer manufacturers bypassing retailers, fashion houses bypassing clothing stores, and coffee producers bypassing supermarkets. Leveraging the possibilities of online sales channels, B2B companies can move up in value chains bypassing intermediaries such as importers, wholesalers, and retailers, and sell to end customers directly. Such companies adapt their business by developing a B2C channel next to their traditional B2B channel, or even by replacing their B2B channel altogether. At the same time, they need to deal with a second challenge: the rise of online platforms as a new type of intermediary. With platforms, we refer to digital marketplaces that connect a large number of (small) suppliers to a large number of consumers (Kenney & Zysman, Citation2016). B2C platforms such as Alibaba, Amazon, Booking.com, e-Bay, and Zalando are attractive to consumers as they aggregate the offerings of many small suppliers in a simple-to-search manner, while also taking care of payment and delivery. Digital marketplaces have also enabled the growth of the peer-to-peer (P2P) segment as private owners rent out their consumer goods to fellow consumers through sharing-economy platforms such as Airbnb, BlaBlaCar, or Getaround (Frenken & Schor, Citation2017). With the advent of digital marketplaces, large incumbent businesses moving into the B2C segment do not only have to care about competition with small businesses but also with consumers trading among themselves.

The move from B2B to B2C markets, along with the rise of digital platforms, emphasise servitisation, which occurs when products are offered with service components as product-service bundles (Baines et al., Citation2009). Servitisation has been studied extensively (Lightfoot et al., Citation2013; Zhang & Banerji, Citation2017). However, it is still largely unknown what kinds of actors are best positioned to exploit the opportunities created by it (Cusumano et al., Citation2015). Additionally, ‘the impact of digital technologies in shaping inter-company relationships as part of servitisation remains largely unexplored’ (Raddats et al., Citation2019, p. 219). In this article, we conduct a revelatory case study (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007) addressing these gaps that examines companies in a sector that has experienced both a shift from B2B to B2C and the growing importance of digital marketplaces as intermediaries. We collect a qualitative dataset of Dutch car lease companies that have moved from B2B (the company car) to B2C (private lease) which we analyse abductively (Dubois & Gadde, Citation2002). The guiding research question of our study is ‘what explains the entry order and strategy of lease companies entering private leasing and carsharing markets?’

Dutch companies are chosen for the study because the Netherlands’ private leasing sector has grown from non-existence in 2012 to more than 188,000 contracts in 2019, during which private leases represented 20% of the country’s total lease contracts (Vereniging van Nederlandse Autoleasemaatschappijen, Citation2016, Citation2020a). Indeed, more than 10% of the country’s newly bought cars in 2018 were private lease cars; therefore, the car lease sector comprised a significant percentage of the country’s overall car market. Moreover, some lease providers encouraged users to share their cars with others using a P2P carsharing platform, thus blending various access-based business models.

Theoretical setting

Innovation studies and the move from B2B to B2C markets

Early research in innovation studies has been dominated by studies on the manufacturing industries, such as the car, aircraft, tractor, PC, and camera industries (Abernathy & Utterback, Citation1978; Baldwin & Clark, Citation2000; Christensen, Citation1993; Sahal, Citation1985; Tripsas & Gavetti, Citation2000). The core assumption underlying this body of work has been that the competitive advantage of firms lies primarily in the ability to continuously improve the technological performance of products and the cost efficiency of production. More recently, scholars have emphasised the importance of business model innovation as well.

One line of research looks at the possible key role of new business models accompanying technological innovation (Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, Citation2013; Chesbrough, Citation2010). As new artefacts do not just replace old ones, but also trigger new user practices, companies may need to adapt their entire business model to exploit the potential of new technology. The exemplar here is the digital camera which rendered the ‘razor-blade model’ of traditional camera companies, making money on films, obsolete (Tripsas & Gavetti, Citation2000). Another line of research deals with business model innovation in existing markets where new actors enlarge the total market through ‘redefining’ a product or service (Markides, Citation2006), often targetting the low-end market segment. This type of business model innovation is known as a disruptive innovation (Christensen & Raynor, Citation2003). In such contexts, incumbents may stick too long to established customers, fearing cannibalisation and conflicting value chains, possibly underestimating the growth potential of challengers entering the markets with new business models. Low-cost airlines serve as a good exemplar here, leveraging the possibility of direct marketing through the Internet with a range of other cost-saving measures within a new, coherent business model (Porter, Citation1996).

How incumbents introduce new business models as means to diversify into already existing market segments, remains understudied. In particular, previous literature has neglected companies that hitherto only sold to firms (B2B) that move up in value chains by bypassing intermediaries and selling to end consumers directly (B2C). Such companies thus diversify their business by developing a B2C channel next to their traditional B2B channel. In this context, diversification thus differs from business model innovation for either an existing segment of customers (e.g., Tripsas & Gavetti, Citation2000) or an entirely new segment of customers (Christensen & Raynor, Citation2003).

Servitisation is a current trend that creates opportunities for incumbents to move from B2B to B2C markets when products are offered with service components as product-service bundles to individual consumers (Baines et al., Citation2009; Tongur & Engwall, Citation2014). What is more, servitisation creates new opportunities through the introduction of services to replace consumer ownership with access to assets. Servitisation literature has largely focused on the manufacturing incumbents introducing service components in their offerings focusing on why and how they do it and how it can be done successfully (Lightfoot et al., Citation2013; Raddats et al., Citation2019; Zhang & Banerji, Citation2017). However, the manufacturers are not the only ones that can exploit the opportunities that are created by servitization and it is still largely unknown, which kinds of actors are best positioned to exploit them (Cusumano et al., Citation2015).

The car lease market, for example, features different types of actors each with their strengths and weaknesses in opportunity exploitation. The car manufacturing owned companies are powerful actors in the existing value chains and know the customer needs, but they suffer from the danger of channel conflict and cannibalisation of the existing business (Du et al., Citation2018; Kim & Chun, Citation2018). The established B2B lease companies have many existing capabilities that they can exploit but they have to create a whole new set of capabilities required to operate in a B2C environment (Yeow et al., Citation2018). Challengers can delve into access-based business models fast and customise their offering for the needs of the B2C market, but they lack the resources that the established actors have (Sosna et al., Citation2010). Because of the strengths and weaknesses of the different kinds of actors, it is unclear what is the entry order of the different kinds of incumbents to the new markets.

Entry order when entering new markets

When entering new markets, companies can choose from three strategies: pioneering, following, and late entrance (Robinson & Chiang, Citation2002). The advantage of an offensive strategy, such as entering as a first mover, is that a company can maintain a technological lead (Lieberman & Montgomery, Citation1988). Moreover, by creating a new product or product category, a company can claim a market as its own, e.g., through identity-based actions developing a customer attachment to the brand (Santos & Eisenhardt, Citation2009).

However, Markides and Geroski (Citation2005) noted that first movers are not always ‘winners’. When first movers enter a market, there is no consensus amongst consumers; technological developments are still in progress - there is no dominant design and there are ‘teething problems’. Thus complementary goods need to be created. This migh allow the followers to take advantage of the opportunity-seeking activities of pioneers (Santos & Eisenhardt, Citation2009). Similarly, late entrants can compete with efficient production costs and low prices. These advantages and disadvantages differ by sector and context (Lieberman & Montgomery, Citation1988; Robinson et al., Citation1994; Schnaars, Citation1994).

Unlike followers and late entrants, pioneers recognise business opportunities early and are knowledgeable about opportunities in markets (Swann, Citation2009). With economies of scale being pervasive in services, first movers benefit from obtaining numerous, primary insights into what their customers want while quickly building network effects, brand value, and reputation. Ideally, recognising opportunities should be complemented with proper resources and capabilities. Indeed, empirical evidence suggests that incumbent firms are responsible for a high share of radical innovations due to their resources (Chandy & Tellis, Citation2000). However, companies with strong competitive positions are less interested in deviating from technological trajectories than entrepreneurial companies to pursue new opportunities (Adner & Snow, Citation2010; Christensen, Citation1997; Kaplan & Tripsas, Citation2008; Tripsas, Citation2009). Their resources include technological, infrastructural, complementary, and reputational assets (Teece et al., Citation1997). To pursue new opportunities, new resources need to be acquired that can only partially build on existing resources.

We take the differentiation between pioneers, followers, and late entrants as a starting point to investigate opportunity exploitation in the private leasing market. Indeed, pioneers, followers, and late entrants have different strategic reasons for the timing of their market entry, and these reasons can be used to examine the effects of entrance timing. They include firms’ sizes, resource positions, resource needs, capabilities, switching costs, and sector-level dynamics, such as the maturity of the sector’s lifecycle and market uncertainty (Gomez et al., Citation2016; Markides & Sosa, Citation2013).

Regarding the servitisation markets, companies can enter them either by building their own sales channels or through partnerships with businesses that have established channels to individual consumers or make use of the newly emerging platforms that serve as a digital marketplace between customers (Kenney & Zysman, Citation2016). Following again the capabilities-theoretical lens, incumbents that have relevant pre-entry experience may be less inclined to enter into alliances or platform sales than firms who lack such capabilities. Nonetheless, usually companies cannot act on their own as they need to gain access to complementary resources, which are often owned by other actors (Kumaraswamy et al., Citation2018). This pushes companies moving from B2B markets to B2C markets to use an ‘ecosystem’ strategy (Adner, Citation2012) involving mobilising complementary resources and capabilities from other firms to serve the needs of individual consumers.

Empirical setting

Car ownership, leasing, and sharing

Car leasing is a financial arrangement in which a lessee pays a lessor for the use of an asset, i.e., a customer pays a company for the right to drive a car (OECD, Citation2001). The customer typically pays a monthly fee that includes vehicle depreciation and interest (Pierce, Citation2012). There are two types of basic leases: financial and operational. A financial lease focuses on financing a car for a consumer; the car acts mainly as a security for the leasing organisation. Typically, the duration of the lease is equal to the expected economic life of the leased object, and tax ownership remains with the customer. Financial leases, therefore, resemble car ownership with a monthly fee instead of an initial lump sum. In contrast, an operational lease is a contract that allows a customer to drive a certain amount of kilometres each year while a lease organisation addresses all additional services. The car is made available to the customer for an agreed period that is shorter than the economic life of the car, usually a couple of years. Economic and legal ownership stays with the leasing company, as does the risk of declining residual value. Full operational leases are the most comprehensive of such agreements and involve the provision of additional services, such as insurance, maintenance, tire replacements, and replacement transport (Vereniging van Nederlandse Autoleasemaatschappijen, Citation2020b).

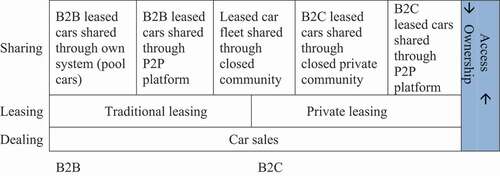

Next to owning and leasing, another way to get access to a car is through carsharing. Companies or individual car owners rent their cars to individual customers only for a certain number of hours for fees that cover all costs of car use. If an individual car owner rents out their car, the agreement is called peer-to-peer (P2P) carsharing, and if a company rents out a car, the agreement is called business-to-consumer (B2C) carsharing. shows the differences between these various modes of car access.

Table 1. A comparison of car access modes

Private leasing and sharing business models in the Netherlands

In the United States and many other countries, discussions about car leases typically refer to financial leases. In Europe, however, operational leases are widespread, both in the traditional B2B market where employers lease a fleet of cars from a leasing company used by individual employees (known as a company car) and the emerging B2C market (known as private lease). The market for private lease is especially increasing rapidly in Italy, The Netherlands, the United Kingdom, France, Spain, and Sweden.Footnote1

In the Dutch context, operational lease in the B2B market is ubiquitous, strongly incentivised by tax regulations. The cars are not part of companies’ taxable assets, and employees can receive access to leased cars instead of salaries, therefore having to pay lower income taxes (Belastingdienst, Citation2020; Graus & Worrell, Citation2008). Private leasing is a new and rapidly growing market segment providing new business opportunities to leasing organisations as it substitutes for private car ownership. The segment has enormous growth potential considering that there are about 7 million private cars in the Netherlands, and private lease contracts represent only about 1.5% of them (Vereniging van Nederlandse Autoleasemaatschappijen, Citation2016).

Recently, modes of sharing are being integrated with leasing services. For example, some leasing organisations have integrated carsharing into their services by establishing a pool of lease cars that can be shared between employees of a company. Similarly, other lease organisations have established shared fleets of lease cars for closed communities, using both B2B models, e.g., inside business parks, and B2C models, e.g., inside new housing developments. Additionally, some companies offer private lease cars for sharing inside closed groups of private individuals, while other companies team up with P2P carsharing platforms, obliging their lessees to offer their lease car on a P2P carsharing platform when they do not use their car. This latter business model is particularly disruptive as it has lowered the monthly operational lease price to a record low of ~150 euro a month, all services included, except fuel. The different forms of sharing offered by lease organisations are shown in .

Methodology

Lease companies substituting formerly ownership-based markets presents under-studied servitisation dynamics. As pointed out earlier, former research has neglected the types of actors best positioned to exploit opportunities created by servitisation and how digitalisation affects the relationships between companies. Our research is thus a revelatory case study (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007) delving into these topics. To answer our research question, we collected a qualitative dataset that we analysed abductively. We engaged in the process of systematic combining, i.e., findings emerged from data, and research on extant literature was used to conceptualise the phenomenon in a way that enabled connecting the findings to existing theories (Dubois & Gadde, Citation2002). The theories were not chosen beforehand, but they were picked to explain emerging patterns on the data. This enabled us to ground our emerging theoretical framework in the data and not on predetermined theories.

Data collection

The data was collected in two phases. The first phase focused on obtaining an initial interpretation of market developments and structures and identifying relevant cases. The canvassing interviews involved two experts and were held in April 2018 for an average of 85 minutes each. The first expert is the director of the association of Dutch vehicle leasing companies (Vereniging van Nederlandse Autoleasemaatschappijen, VNA), and the second expert is a director of a Dutch platform that is used for management in the automotive industry.

Based on these interviews and desk research, a list of diverse organisations was compiled to be studied in the second phase. Different businesses operate in the Dutch car lease market; they range from numerous small local lease organisations to a few large multinational companies that dominate the market in terms of the numbers of leased cars. Additionally, several other small businesses operate in the market; they entered the segment directly with private leases or radical sharing business models. Businesses and the Dutch Lease Association typically divide lease organisations in the Dutch market into two categories. The first is family-owned universal lease organisations that are independent of and are not affiliated with automotive conglomerates; the second is dealerships and lease organisations that are owned by car manufacturers or banks (Erich, Citation2013).

To collect the data, we adopted a theoretical sampling strategy (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007). That is, it was collected from 10 organisations selected based on the following criteria: their offering on carsharing and private car lease services, timing used to enter new markets, firm size, and position in the car sector value chain. Subsequently, key decision-makers in the organisations were interviewed regarding their strategic decisions; reasons for their strategies were identified. Between June to September 2018, 11 interviews were conducted: one interview each for nine organisations and two interviews for one organisation. The average interview length was 68 minutes. provides an overview of the organisations and their characteristics studied for this article. The table also shows the roles of those who were interviewed for the study. The companies participating in the study are referred to using pseudonyms for the sake of anonymity.

Table 2. A list of the studied organisations

Data analysis

Using an existing classification (Robinson & Chiang, Citation2002), the studied organisations were divided into three categories: pioneers, early followers, and late entrants. We did this based on five different criteria, which are presented in . Launch timing of their private-lease and/or sharing services was the most important criterion because it affected the order in which the companies entered the market. The importance and breadth of the services were also factors that were considered: they brought nuance to the strategy because in some cases the first companies to experiment are not necessarily the ones that bring about a major change in the supply chain. Finally, self, peer, and expert evaluations were used for corroborative evidence of the organisations’ strategies. In uncertain cases, they were used to fine-tune the categorisation

Table 3. The categorisation criteria

When the categorisations were complete, we examined the reasoning on which the companies´ strategies were built. We did this by asking why the companies launched private leasing and sharing services and why they chose to enter the market when they did. We also asked what difficulties they encountered during their launches; this was done to understand possible hindrance factors. These answers provided us a thorough understanding of the companies’ perceptions regarding their strategies. However, we also compared the companies to each other to uncover factors that some companies have been lacking but have not been aware of it. Altogether six factors emerged from the data as possible reasons explaining the strategies: knowledge of the opportunities, position in the supply chain, resources, structure, perception of the market, and perception of the company. We examined these reasons across the cases to understand which explain the different strategies.

Both the categorisation efforts and the reasons for strategies were discussed among the research team. On the categorisation, special attention was paid to actors, which deviated from generic patterns identified in the data (e.g., early actors, which are still small in private leasing and sharing services at the time of the interviews). These actors were important to understand which strategies work well on the market. On the reasons explaining the strategies, we tried to distil necessary conditions for why a company becomes a pioneer, an early follower, or a late entrant. Therefore, we attempted to find factors that are necessary to enter the market but that only some actors possess.

Findings

This chapter presents the findings to address the research question: ‘what explains the entry order and strategy of lease companies entering private leasing and carsharing markets?’ The findings are presented using the three categories mentioned above: pioneers, early followers, and late entrants.

Pioneers

The car manufacturing companies had tried private leasing services in their own sales channels since the early 2000s. However, the trials were unsuccessful. As a representative of ‘LuxLeasing’ stated, ‘I worked at [a car manufacturing company] from 2003 to 2011, and in 2003, we already had a private lease product there. Absolutely no one bought it’. Private leasing was just an additional service that was offered to the customer, so no one had a significant interest in aggressively marketing it. It did not make a significant difference for the car manufacturer or the dealer whether the customer bought or leased the car. Moreover, customers coming to a car dealer were not very interested in how to get the car; rather, they were interested only in the cars themselves. The failure of these early experiments caused significant scepticism among established lease actors regarding the benefits of private leasing.

Thus, the first actors to believe in private leasing and sharing services were small companies. A private lease business was started in 2010 by ‘AdvertCar’, a company that primarily made money through web hosting and web portal design and used leased cars as marketing space. Leasing was then a side business with which the company could save on expenses that would normally go to billboard marketing firms. AdvertCar’s offering was more of a financial lease than it was an operational lease – it did not include maintenance services. However, it was a service in which customers paid a recurring fee for the car, and after the contract, AdvertCar took care of its aftersales. Therefore, the business bypassed the dominant sales channel in which each customer bought a car from a dealership. AdvertCar had to establish a financing infrastructure itself because lease companies did not believe in the business. As a representative said, ‘Leasing companies did not believe in [private leasing] at all. They all said, “That’s nothing; we tried”. Then [we] set up a bond platform. So we are also self-financing … That was not easy’.

Sharing was brought into lease services by the small company ‘GreenLease’ in 2011. It had been offering B2B leasing to a pro-environment demographic by cooperating with a sustainability-oriented bank. The sharing service was started based on a customer request:

We got a request [from] a client seven years ago [about whether] they were allowed to share their car on a P2P carsharing platform. They weren’t allowed to do that through other lease organisations; there were concerns about risk, insurance, that kind of stuff. We studied the risks and saw, “Hey, there is someone who wants a sustainable car and wants to do something sustainable with it, so why not facilitate it?”. (GreenLease)

However, both GreenLease and AdvertCar were unable to grow their businesses in a significant way. Scale is a very important success factor in the car lease business because profits are primarily made through procurement, i.e., car manufacturers sell cars at low costs if they are bought in large quantities. Therefore, the breakthrough in the market had to be done by one of the established actors. The first mover was ‘LeaseBig’, a company owned by an investment group. It was one of the largest actors in B2B leasing in the Netherlands. However, even for this established company, it was difficult to enter the market. Car manufacturers were protective of their current supply chains and were very reluctant to sell cars for private leasing purposes because they wanted to preserve their contact with the customer.

Car manufacturers panicked [over] cars being sold outside their supply chains, so [there were] no [good purchasing] conditions. Or you did not get the cars at all … all the dealers said, “It is a business that we should have done”, or “We do not earn anything with it”. (LeaseBig)

However, LeaseBig managed to find a car manufacturer that was willing to provide cars and an electronic retail company that was willing to work as a sales channel for the new service. The companies launched a campaign in connection with the electronic retail company’s sales campaign in autumn 2014. This was the first large-scale operational lease service in the Netherlands. Each car was offered for a monthly fee that included the vehicle, insurance, maintenance, repairs, and tire replacements. The campaign was a significant success.

[The introduction of private leasing] was done in an innovative way that [was] almost disruptive … car companies really stood there with their mouths open. They said, “What’s happening now? Usually, the consumer comes to us. And now an [electronic retail company] or an internet channel has something similar to offer?”. (Expert 1)

Consequently, offering full operational leases outside of the regular car retail channel became popular among the industry. LeaseBig established a very successful collaboration with the Dutch touring club (De Koninklijke Nederlandse Toeristenbond, ANWB), which was the largest club in the Netherlands and had 4.5 million members. Other lease actors established partnerships with retail companies, such as the supermarket chain Albert Heijn and the hardware chain GAMMA.

There are three reasons LeaseBig was the first successful pioneer in the market instead of the other companies that now offer private leasing: its knowledge of opportunities, position in the value chain, and resources. These are shown in detail in . Regarding its knowledge of opportunities, LeaseBig had sold used cars to individual customers for years because it provided an aftermarket for its B2B lease cars. Thus the company knew that consumers might be interested in leasing and it believed that the market would be there. Moreover, regarding its position in the value chain, LeaseBig was optimally positioned to pursue the opportunity. It had very little business in the B2C car sales value chain, so its private lease venture did not cannibalise that business. Finally, regarding its resources, B2B leasing was stagnating and the competition was increasing, but LeaseBig had the resources to overcome these challenges. In addition to its buying power, it had some of the resources needed to serve individual customers. For example, the company had been developing its systems to serve small and medium businesses (SMEs) for years. Therefore, its shift to the B2C market was not too risky.

Table 4. The factors that facilitated LeaseBig’s position as a pioneer

After entering the market, LeaseBig rapidly developed its private lease business and became one of the biggest companies in the market. Additionally, the company actively innovated with sharing services. It allowed the sharing of its cars and developed a product to offer carsharing to its B2B customers. It also developed a partnership with a P2P carsharing company to expand the sharing to its private leasing services.

Early followers

The success of LeaseBig inspired many other companies to enter the private lease market, beginning in 2015. As ‘John’ from ‘LeaseDeVries’ said,

We really had a smart following strategy … other players [were entering] the market, [LeaseBig] had one of the first big campaigns … all of a sudden, [we] saw the market changing, and then, well, [we got] FOMO, [or a] fear of missing out … so we also had to have a private lease solution.

The availability of inexpensive cars fuelled the growth of the market and allowed more companies to enter. Demand for automobiles decreased during the financial crisis of 2008, and thus there was a significant overproduction of cars. Therefore, lease companies could buy large quantities of vehicles from importers at discounts of up to 35%. The cars were not suitable for traditional B2B leasing because employees usually had high expectations for company cars and wanted them customised to their needs. However, for private leasing, they were ideal. This situation allowed lease companies to offer full operational leases for monthly payments that were equal to or cheaper than loan payments for a new car. These offers were facilitated further by the availability of low-interest loans, which also existed because of the financial crisis. The lease companies used these loans to buy cars in bulk.

Half of the early followers were family conglomerates with multiple branches in the automotive sector. These companies started as family-owned car dealerships and slowly and organically grew into larger company groups while staying family owned and while continuously adding ventures, assets, and services to facilitate their broad customer groups. B2B leasing was a strong pillar in such groups. Private customers were served at dealerships belonging to the conglomerates, and they were able to access various financial options, such as regular payments.

Although these companies had strong relationships with individual consumers, they did not observe opportunities as well as LeaseBig. These companies did, however, perceive clear changes in the market. New services, such as carsharing, were emerging, and this increased the diversity of transportation options. Additionally, some B2B lease customers were moving away from the company car model and offering their employees mobility budgets that they could use on different transportation options. Therefore, increasing numbers of customers were looking for transportation partners instead of leasing companies to address all their transportation needs. However, these family conglomerates were deeply ingrained in the existing car supply chain and were accustomed to existing business models. Thus, the emergence of the private lease market caught them by surprise. As ‘Steve’ from LeaseDeVries noted,

Private leasing really opened the eyes of lease organisations. For 30 years, we did the same trick in a saturated market, actively poaching on each other’s market shares. And suddenly we thought of something new … a new market. What a Walhalla!

These companies were embedded in the B2C supply chain because they owned parts of it. Therefore, for them, private leasing was not only a new business opportunity but also a threat because it could cannibalise some of their existing business. However, their existing business was already threatened because in the wake of the financial crisis employers were less inclined to provide their workers with company cars, which stagnated the B2B lease market. Additionally, the car manufacturers were forward integrating in the supply chain.

You see the car manufacturers forward integrate along the value chain. They want to have the links of the chain under their own management. Because of that, we had to give up some of our import business in the Netherlands. (Steve, LeaseDeVries)

Regarding sharing services, family conglomerates were quite innovative. They were involved in many different businesses in the car sector, and sharing was a natural extension of private leasing. It was also a way for companies to differentiate themselves in the market, which was becoming more competitive. As John from LeaseDeVries explained, ‘We [we]re not the biggest, [and] we [we]re not the smallest; [we were] kind of stuck in the middle. Therefore, we need[ed] to diversify into other markets’. Thus, family conglomerates began to offer carsharing through partnerships and even offered lower lease prices to customers who were willing to share their cars.

Late entrants

Some actors did not enter the private lease market until 2016 and 2017, when the sector had already begun to grow. They were hesitant to offer carsharing services and had only planned to do so or had only offered it to the B2B segment. These companies were owned by banks, and the slow reaction was partially due to this: ‘You just [saw] it, [we are] … part of a bank. Clearly risk-averse’ (LuxLeasing).

However, their late entrance can also be explained by what these companies lacked as compared to LeaseBig: knowledge of opportunities and resources. These companies did not work closely with individual customers; rather, they mainly worked with large companies and were therefore unaware of private consumers’ interest in lease services. Additionally, these late entrants did not have the technical resources that LeaseBig had. LeaseBig could extend its organisation serving SMEs to address private leasing. Although it had to recruit new people who had experience with the consumer market like all other companies launching private leasing, it could facilitate the capabilities and IT systems already designed for small customers. The late entrants could not adopt this strategy. They had to build entirely new organisations to cater to the needs of private lease customers. The quick, unpredicted growth of the private lease market also caused these organisations to reconsider their strategic flexibility concerning their ability to react to rapid changes to their business model. As ‘KaidenAuto’ explained,

We are now working on a new strategic plan—and [the rapid growth of private leasing] indeed led us as an organisation [to] really be more flexible … it [did] not broadly change [our] strategy, but it [made] even clearer how fast [we] should be able to act and how flexible [we] should be.

Discussion

Our paper examines the diverse strategies of lease market actors in moving into private leasing and carsharing businesses in terms of entry timing and strategy. We discover that although car manufacturers and small entrepreneurial actors had experimented with private car-leasing and carsharing business models for years, the most impactful entrance into the market was done by a dominant lease market actor LeaseBig that had a campaign partnership with a retail consumer-electronics company. This created a bandwagon effect in which family-owned automotive conglomerates and, later, bank-owned lease companies followed the leader into the market. P2P sharing business models benefitted from these entrances into private leasing. In particular, these models involved partnerships with P2P digital marketplaces on which consumers were allowed to rent out their private lease cars. The main reasons explaining LeaseBig’s successful pioneering strategy were its resources, its knowledge about opportunities, which came from the used car business, and its optimal position in the supply chain as a pure lease actor. Below we present the contribution of our case to the literature of disruptive innovation and servitisation and to the one on sharing economy and digitalisation.

Contribution to literature on disruptive innovation and servitisation

In many ways, the emergence of private lease resembles a classic case on disruptive innovation (Christensen, Citation1997). Private leasing was invented and experimented with by the car manufacturing incumbent companies, which, however, did not see the potential in the business. Subsequentially, the pioneer private leasing companies targeted over-serviced customers: people who were not really interested in their cars but only wanted mobility for a decent price. However, our paper presents one striking difference to the classical cases on disruption: the disruptor was not a new entrant (Markides, Citation2006) but an established company central to the incumbent value network. Although small entrepreneurial company AdvertCar had tried to experiment on the market early on, it had significant problems mobilising partners. Instead, the disruption resulted mainly from an incumbent and legitimate actor with ample resources. Interestingly, the car manufacturing owned lease companies had some of the same resources that LeaseBig had (see ) – they had direct access to customer information through the dealers and had important resources like purchasing power. However, their experimentation on private leasing was half-hearted because car manufacturers dominated the existing value chain. This rigidity conflicts with servitisation literature, which notes that manufacturing incumbents are typically proactive when providing services to product markets (Baines et al., Citation2009; Cusumano et al., Citation2015). We argue that this is due to the type of service innovation that private leasing is.

Cusumano et al. (Citation2015) create a typology of three kinds of services offered by the product firms: sales transaction smoothing services (e.g., warranty), product usage adapting services (e.g., major customisation), and product substituting services (e.g., renting and leasing). Manufacturing companies are usually very interested in providing the two first types of services because it leads to increased sales. However, providing product substituting services is risky (Benedettini et al., Citation2015). Thus, they require a significant demand-pull originating from the market. The pull is fairly strong in the B2B sector (Cusumano et al., Citation2015; Raddats & Easingwood, Citation2010) because companies often aim to save costs, lighten the balance sheet, and outsource asset management. In the automotive industry, this is demonstrated by the established B2B lease business and by the fact that companies have experimented with getting rid of the company cars by offering mobility budgets to their employees. However, in the B2C sector, the demand-pull effect is much weaker. People do not present much experimentation in their car purchases but they are more guided by past behaviour and brand loyalty (Nayum & Klöckner, Citation2014). Therefore, it is unlikely that people in large numbers would be vocal in requesting alternatives to owning a car from the manufacturers or dealers. This creates possibilities for other actors to disrupt these markets with substitution services

In the automotive sector, the importance of substitution services is constantly increasing. This is partially due to the raise of sharing and leasing business models but also due the future prospect of automated driving (Genzlinger et al., Citation2020). Following this dynamic, we call for more research on servitisation that focuses on ecosystems and networks instead of individual companies. We know very little, for example, what are the antecedents of successful partnerships to exploit substitution services highlighted by the unexpected cooperation of a leasing company, car manufacturer, and electronics retailer that opened up the Dutch private lease markets. Of course, not all industries seem as likely candidates for these kinds of disruptions, as lease and rental business models are profitable only for expensive and durable products. In addition to the car industry, for example, furniture or consumer electronics sectors seem possible targets for disruption.

Contribution to literature on digital innovation

Our research emphasises the importance of an established actor in bringing about a disruptive innovation. These kinds of established companies providing access to assets have been somewhat neglected in management literature. For example, research on sharing economy studying the shift from ownership to access to assets has focused on the efforts of disruptive, dedicated sharing actors (Pelzer et al., Citation2019; Thelen, Citation2018) and on reactions of incumbents that offer ownership-based products or services (Ciulli & Kolk, Citation2019; Weber et al., Citation2019). However, as demonstrated in , access-based business models are more a continuum than they are a dichotomy. Thus, more research on the diversity of the access-based business model and required capabilities is called for with more attention on the established actors like lease and rental companies.

Regarding digital capabilities, while all of our case companies managed to build private leasing channels, their entry order was partially dictated by their existing capabilities. LeaseBig was able to exploit a successful pioneer strategy in the private lease market because it had developed e-commerce capabilities by serving SME customers. Late movers, on the other hand, were companies that were used to dealing with large customers. This finding is in line with research on the literature on e-commerce capabilities, which has discovered that successful e-commerce adoption requires established companies to build their capabilities gradually (Cui & Pan, Citation2015; Jelassi & Leenen, Citation2003). Thus, incumbents that have relevant ‘pre-entry experience’ (Helfat & Lieberman, Citation2002; Klepper & Simons, Citation2000), specifically related to e-commerce, have a better chance of being successful when adding a B2C channel to their B2B operations than firms who lack such capabilities.

Regarding the sharing economy business models, it is an interesting finding that while many of the lease companies are building the private leasing capabilities themselves, they partner up with carsharing companies to enable sharing of the leased cars. While the lease companies have to create new capabilities concerning B2C markets to enable private leasing, it has not presented an insurmountable challenge to any actor. Carsharing, on the other hand, is fundamentally a digital innovation requiring entirely different capabilities from the leasing business, for example, on software development and online community governance (Reischauer & Mair, Citation2018; Vaskelainen & Piscicelli, Citation2018). Additionally, it requires aggressive marketing because sharing services benefit from network effects, i.e., the value of the service increases with each additional user (Kenney & Zysman, Citation2016). Thus, carsharing requires very different capabilities from those that the lease actors already possess, and therefore, the companies prefer to access the market through partnerships.

The different strategies for private leasing and carsharing speak to the importance of an ecosystem strategy in service markets that are transforming by digitalisation (Adner, Citation2012), where a traditional B2B company aligns the strategies and capabilities of its partners into a new configuration to be able to offer a new B2C proposition in a mass consumer market. However, not all established actors enter the sharing markets with partnerships but choose to build the capabilities themselves. For example, in the accommodation sector, some hotels have invested heavily on their own P2P business models (Ciulli & Kolk, Citation2019). Therefore, we call for more research on the factors that lead to the choice of developing digital capabilities for access-based business in-house versus acquiring them through partnerships.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. See for example, the reports by Fleet Europe (https://www.fleeteurope.com/en/financial-models/europe/analysis/private-lease-logical-next-step?) and Frost & Sullivan (https://ww2.frost.com/frost-perspectives/promising-year-ahead-for-private-vehicle-leasing-industry/).

References

- Abernathy, W. J., & Utterback, J. M. (1978). Patterns of industrial innovation. Technology Review, 64(7), 228–254.

- Adner, R. (2012). The wide lens: A new strategy for innovation. Portfolio/Penguin.

- Adner, R., & Snow, D. (2010). Old technology responses to new technology threats: Demand heterogeneity and technology retreats. Industrial and Corporate Change, 19(5), 1655–1675. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtq046

- Baden-Fuller, C., & Haefliger, S. (2013). Business models and technological innovation. Long Range Planning, 46(6), 419–426. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.08.023

- Baines, T. S., Lightfoot, H. W., & Kay, J. M. (2009). Servitized manufacture: Practical challenges of delivering integrated products and services. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part B: Journal of Engineering Manufacture, 223(9), 1207–1215. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1243/09544054JEM1552

- Baldwin, C. Y., & Clark, K. B. (2000). Design rules: Volume 1. The power of modularity. MIT Press.

- Belastingdienst. (2020). Ik koop of lease een auto van de zaak. https://www.belastingdienst.nl/wps/wcm/connect/bldcontentnl/belastingdienst/zakelijk/ondernemen/ik_koop_of_lease_een_auto_van_de_zaak

- Benedettini, O., Neely, A., & Swink, M. (2015). Why do servitized firms fail? A risk-based explanation. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 35(6), 946–979. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-02-2014-0052

- Chandy, R. K., & Tellis, G. J. (2000). The incumbent’s curse? Incumbency, size, and radical product innovation. Journal of Marketing, 64(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.64.3.1.18033

- Chesbrough, H. (2010). Business model innovation: Opportunities and barriers. Long Range Planning, 43(2–3), 354–363. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.010

- Christensen, C. M. (1993). The rigid disk drive industry: A history of commercial and technological turbulence. Business History Review, 67(4), 531–588. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3116804

- Christensen, C. M. (1997). The innovator’s Dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail. Harvard Business School Press.

- Christensen, C. M., & Raynor, M. (2003). The innovator’s solution: Creating and sustaining successful growth. Harvard Business Review Press.

- Ciulli, F., & Kolk, A. (2019). Incumbents and business model innovation for the sharing economy: Implications for sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 214, 995–1010. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.295

- Cui, M., & Pan, S. L. (2015). Developing focal capabilities for e-commerce adoption: A resource orchestration perspective. Information and Management, 52(2), 200–209. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2014.08.006

- Cusumano, M. A., Kahl, S. J., & Suarez, F. F. (2015). Services, industry evolution, and the competitive strategies of product firms. Strategic Management Journal, 36(4), 559–575. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2235

- Du, Y., Cui, M., & Su, J. (2018). Implementation processes of online and offline channel conflict management strategies in manufacturing enterprises: A resource orchestration perspective. International Journal of Information Management, 39, 136–145. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2017.11.006

- Dubois, A., & Gadde, L.-E. (2002). Systematic combining: An abductive approach to case research. Journal of Business Research, 55(7), 553–560. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00195-8

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

- Erich, M. (2013). Assetvisie Autoleasemaatschappijen. Autolease op weg naar 2020. https://docplayer.nl/718786-Ing-economisch-bureau-assetvisie-autoleasemaatschappijen-autolease-op-weg-naar-2020.html

- Frenken, K., & Schor, J. (2017). Putting the Ssharing Eeconomy into Pperspective. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions. 23, 3–10.https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2017.01.003

- Genzlinger, F., Zejnilovic, L., & Bustinza, O. F. (2020). Servitization in the automotive industry: How car manufacturers become mobility service providers. Strategic Change, 29(2), 215–226. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jsc.2322

- Gomez, J., Lanzolla, G., & Maicas, J. P. (2016). The role of industry dynamics in the persistence of first mover advantages. Long Range Planning, 49(2), 265–281. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2015.12.006

- Graus, W., & Worrell, E. (2008). The principal–agent problem and transport energy use: Case study of company lease cars in the Netherlands. Energy Policy, 36(10), 3745–3753. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2008.07.005

- Helfat, C. E., & Lieberman, M. B. (2002). The birth of capabilities: Market entry and the importance of pre-history. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11(4), 725–760. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/11.4.725

- Jelassi, T., & Leenen, S. (2003). An e-commerce sales model for manufacturing companies: A Conceptual framework and a European example. European Management Journal, 21(1), 38–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0263-2373(02)00151-2

- Kaplan, S., & Tripsas, M. (2008). Thinking about technology: Applying a cognitive lens to technical change. Research Policy, 37(5), 790–805. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2008.02.002

- Kenney, M., & Zysman, J. (2016). The rise of the platform economy. Issues in Science and Technology, 32(3), 61–69. http://issues.org/32-3/the-rise-of-the-platform-economy/

- Kim, J. C., & Chun, S. H. (2018). Cannibalization and competition effects on a manufacturer’s retail channel strategies: Implications on an omni-channel business model. Decision Support Systems, 109, 5–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2018.01.007

- Klepper, S., & Simons, K. L. (2000). Dominance by birthright: Entry of prior radio producers and competitive ramifications in the U.S. television receiver industry. Strategic Management Journal, 21(10–11), 997–1016. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0266(200010/11)21:10/11<997::AID-SMJ134>3.0.CO;2-O

- Kumaraswamy, A., Garud, R., & Ansari, S. (2018). Perspectives on disruptive innovations. Journal of Management Studies, 55(7), 1025–1042. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12399

- Lieberman, M. B., & Montgomery, D. B. (1988). First‐mover advantages. Strategic Management Journal, 9(S1), 41–58. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250090706

- Lightfoot, H., Baines, T., & Smart, P. (2013). The servitization of manufacturing: A systematic literature review of interdependent trends. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 33(11–12), 1408–1434. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-07-2010-0196

- Markides, C. (2006). Disruptive innovation: In need of better theory. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 23(1), 19–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2005.00177.x

- Markides, C., & Geroski, P. A. (2005). Fast second: How successful companies bypass radical innovation to enter and dominate new markets. Jossey-Bass. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/ijppm.2005.07954dae.002

- Markides, C., & Sosa, L. (2013). Pioneering and first mover advantages: The importance of business models. Long Range Planning, 46(4–5), 325–334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.06.002

- Nambisan, S., Lyytinen, K., Majchrzak, A., & Song, M. (2017). Digital innovation management: Reinventing innovation management research in a digital world. MIS Quarterly, 41(1), 223–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.25300/misq/2017/41:1.03

- Nayum, A., & Klöckner, C. A. (2014). A comprehensive socio-psychological approach to car type choice. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 40, 401–411. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.10.001

- OECD. (2001). OECD glossary of statistical terms. OECD glossary of statistical terms - financial lease – BPM definition. https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=975

- Pelzer, P., Frenken, K., & Boon, W. (2019). Institutional entrepreneurship in the platform economy: How Uber tried (and failed) to change the Dutch taxi law. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 33, 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.02.003

- Pierce, L. (2012). Organizational structure and the limits of knowledge sharing: Incentive conflict and agency in car leasing. Management Science, 58(6), 1106–1121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1110.1472

- Porter, M. E. (1996). What is strategy? Harward Business Review, 74(6), 61–78. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1996.tb00796.x?casa_token=i2_eBF81WisAAAAA:t61C8OFzLZXzKJ039W2tpbfjvyOePbu6mKTRfXDMJDPIJvdn4_gFH_HPhLtiLG0pE3ZVYIQgSZptmcA

- Raddats, C., & Easingwood, C. (2010). Services growth options for B2B product-centric businesses. Industrial Marketing Management, 39(8), 1334–1345. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2010.03.002

- Raddats, C., Kowalkowski, C., Benedettini, O., Burton, J., & Gebauer, H. (2019). Servitization: A contemporary thematic review of four major research streams. Industrial Marketing Management, 83, 207–223. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.03.015

- Reischauer, G., & Mair, J. (2018). How organizations strategically govern online communities: Lessons from the sharing economy. Academy of Management Discoveries, 4(3), 220–247. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amd.2016.0164

- Robinson, W. T., & Chiang, J. (2002). Product development strategies for established market pioneers, early followers, and late entrants. Strategic Management Journal, 23(9), 855–866. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.257

- Robinson, W. T., Kalyanaram, G., & Urban, G. L. (1994). First-mover advantages from pioneering new markets: A survey of empirical evidence. Review of Industrial Organization, 9(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01024216

- Sahal, D. (1985). Technological guideposts and innovation avenues. Research Policy, 14(2), 61–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-7333(85)90015-0

- Santos, F. M., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2009). Constructing markets and shaping boundaries: Entrepreneurial power in nascent fields. Academy of Management Journal, 52(4), 643–671. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.43669892

- Schnaars, S. P. (1994). Managing imitation strategies. Free Press.

- Sosna, M., Trevinyo-Rodríguez, R. N., & Velamuri, S. R. (2010). Business model innovation through trial-and-error learning: The Naturhouse case. Long Range Planning, 43(2–3), 383–407. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2010.02.003

- Swann, G. M. P. (2009). The economics of innovation: An introduction. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199708)18:7<509::AID-SMJ882>3.0.CO;2-Z

- Thelen, K. (2018). Regulating uber: The politics of the platform economy in Europe and the United States. Perspectives on Politics, 16(4), 938–953. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592718001081

- Tongur, S., & Engwall, M. (2014). The business model dilemma of technology shifts. Technovation, 34(9), 525–535. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2014.02.006

- Tripsas, M. (2009). Technology, identity, and inertia through the lens of “the digital photography company”. Organization Science, 20(2), 441–460. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1080.0419

- Tripsas, M., & Gavetti, G. (2000). Capabilities, cognition, and inertia: Evidence from digital imaging [Special Issue: The Evolution of Firm Capabilities]. Strategic Management Journal, 21(10/11), 1147–1161. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0266(200010/11)21:10/11<1147::AID-SMJ128>3.0.CO;2-R

- Vaskelainen, T., & Piscicelli, L. (2018). Online and offline communities in the sharing economy. Sustainability (Switzerland), 10(8), 2927. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082927

- Vereniging van Nederlandse Autoleasemaatschappijen. (2016). VNA Autoleasemarkt in cijfers 2015. https://www.vna-lease.nl/website/iedereen/feiten-cijfers/infographics-2015

- Vereniging van Nederlandse Autoleasemaatschappijen. (2020a). Autoleasemarkt in cijfers 2018. https://www.vna-lease.nl/website/iedereen/feiten-cijfers/infographics-2018

- Vereniging van Nederlandse Autoleasemaatschappijen. (2020b). VNA Begrippenlijst. https://www.vna-lease.nl/begrippenlijst

- Weber, F., Lehmann, J., Graf-Vlachy, L., & König, A. (2019). Institution-infused sensemaking of discontinuous innovations: The case of the sharing economy. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 36(5), 632–660. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12499

- Yeow, A., Soh, C., & Hansen, R. (2018). Aligning with new digital strategy: A dynamic capabilities approach. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 27(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2017.09.001

- Zhang, W., & Banerji, S. (2017). Challenges of servitization: A systematic literature review. Industrial Marketing Management, 65, 217–227. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.06.003