ABSTRACT

Entrepreneurs pitching new ideas are hard-pressed to frame their message in the most compelling way to win the attention and support of relevant audiences. But could a simple shift in framing sanction the success or failure of their communication efforts? Drawing on recent scholarship on the recognition of novel ideas and language, we compare the effectiveness of two framing approaches to idea pitching: abstract vs. concrete framing. We suggest that the best framing strategy to rally audience support depends on the novelty of the idea. Two controlled experiments where we investigate the combined impact of an idea’s degree of novelty and the abstractness level (why vs. how) of the framing strategy used to pitch it on the idea’s evaluation by members of a lay audience (e.g. crowdfunders, students, or other non-professional evaluators) confirm our intuition. The findings indicate that radical ideas are significantly more likely to elicit favourable evaluation from lay audience members when those ideas are framed in concrete ‘How’ terms; whereas incremental ideas fare better when framed in abstract ‘Why’ terms. By focusing on the framing strategies that entrepreneurs can use to communicate their new ideas, our study contributes to the growing research on the role of language in shaping the recognition of novelty. More generally, it provides entrepreneurs with actionable insights that they can leverage to attract attention and support from a general (lay) audience.

Introduction

What is the most effective way for entrepreneurs to communicate a highly innovative entrepreneurial idea in order to capture audience members’ attention and support? Should they favour a concrete or abstract form of communication? Highly innovative entrepreneurial ideas typically refer to products or services that defy straightforward categorisation in terms of existing concepts (Herzenstein et al., Citation2007). Consider the case of Segway, a pioneering idea of a self-balancing scooter (Herzenstein et al., Citation2007), at the time of its launch widely heralded as a technological wonder. The Segway was promoted as a product that aimed to change the way people move and many opinion leaders ‘admired what the Segway could do’ (Barringer & Ireland, Citation2012, p. 103). However, customers could not answer many practical questions such as: ‘How do you take it with you in your car? How do you park it? How and where can you ride it? Sidewalks or roads? How do you get it up or down stairs?’ (Barringer & Ireland, Citation2012, p. 103, emphasis added). Customers could not figure out how the Segway would fit into their existing lifestyle as it appeared to be incongruous with existing schemasFootnote1 regarding transportation vehicles. Would a more concrete communication – a framing strategy more attentive to how the Segway functions – have made to the success of this pathbreaking solution possible?

Recent evidence suggests that the answer to this question is not plainly positive or negative, but depends on the target audience. Studying the impact of framing a new idea in abstract or concrete terms when it is pitched to audience members with varying levels of domain-relevant expertise, Falchetti et al. (Citation2022) demonstrate experimentally that framing strategies based on concrete how arguments appeal more to expert evaluators (e.g., professional investors, innovation managers), while framing strategies based on abstract why arguments appeal more to lay evaluators (e.g., crowdfunders, students or other non-professional evaluators). The intuition behind this finding is rooted in cognitive research suggesting that, unless individuals have developed significant domain-relevant expertise, they tend to rely on abstract, high-level mental construals in their evaluations (Bettman & Sujan, Citation1987; Su et al., Citation2008). Since information congruent with individuals’ mental representations is more comprehensible (Kim et al., Citation2009; Mandler, Citation1995; White et al., Citation2011) and persuasive, lay evaluators are more appreciative of novel ideas when those ideas are framed in abstract why terms. In this study, we build on Falchetti et al. (Citation2022) to suggest another potential boundary condition for whether a novel idea should be communicated emphasising a concrete or abstract language: the degree of novelty of the idea. Holding the evaluating audience constant, we then ask: ‘What framing strategies, concrete or abstract, should entrepreneurs prioritise when pitching a radical idea? Should the same framing approach be applied to ideas that are incremental?’

Extant experimental evidence indicates that different levels of information novelty in evaluative tasks elicit different processing orientations (Liu, Citation2008). In particular, this evidence shows how a concrete, low-level mental construal is activated when individuals process highly novel information that is discrepant with pre-existing schemas (Vallacher & Wegner, Citation1987). Stated differently, individuals tend to process highly novel information in a detailed and piecemeal manner. By contrast, less novel information does not activate a concrete thinking mode because in this case the information usually matches an individual’s pre-existing schemas. Since idea framings that match individuals’ mental construals are processed more fluently and lead to more positive evaluations (Falchetti et al., Citation2022), we anticipate radical ideas that contain highly novel information to be evaluated more favourably when framed in concrete (how) than in abstract (why) terms, while we expect the opposite to hold true for incremental ideas that contain less novel information.

Prior evidence supports this intuition. In articulating their rhetorical typology, for instance, van Werven et al. (Citation2015) suggest that ‘arguments by cause’ (why-laden framing in our terminology) are less effective in supporting radical ideas due to the inherent uncertainty associated with cause-effect relations in very novel concepts. Arguments by cause are weak when targeting radical concepts because it is uncertain whether the explanatory facts upon which they are based will have the expected effect. Recent empirical findings by Boulongne and Durand (Citation2021) similarly indicate that ambiguous offerings (e.g., products that unravel existing categories) elicit more positive evaluations when ‘audiences evaluate [those] entities in terms of how they can meet one’s needs’ (p. 259) – when, in other words, evaluative responses are primed on concrete, feasibility cues. In summary, the congruity level between the framing of an idea and its degree of novelty will result in differentially favourable attitudes among lay evaluators. To examine this prediction, we chose the case of entrepreneurial pitches as our experimental setting. We manipulated an idea’s degree of novelty (incremental or radical) and the abstractness level (why vs. how) of the framing strategy used to pitch that idea to lay evaluators. We investigated the combined effect of these variables on two evaluative outcomes: the appreciation of the idea and the propensity to support it.

The findings from these experiments confirm our prediction contributing valuable insights to the growing stream of language-oriented scholarship in entrepreneurship that is concerned with how entrepreneurial actors can strategically mobilise narratives and language to successfully champion their ideas (Cattani et al., Citation2020; Clarke et al., Citation2019; Cutolo & Ferriani, Citation2023; Falchetti et al., Citation2022; Huang et al., Citation2021; Navis & Glynn, Citation2011). Our work also informs extant scholarship in innovation and creativity that focuses on the evaluation and recognition of novel ideas (e.g., Cattani et al., Citation2022; Chai & Menon, Citation2019; Chan & Parhankangas, Citation2017; Perry-Smith & Mannucci, Citation2017; Trapido, Citation2015) and addresses recent calls for more randomised experiments in entrepreneurship research (Bolinger et al., Citation2022; R. M. Stevenson & Josefy, Citation2019; R. Stevenson et al., Citation2020). More broadly, the finding that ideas with varying degrees of novelty should be framed differently is relevant to research on persuasive communication and linguistic devices, including politics, advertising effectiveness, consumer choices, and other contexts in which the congruity between the novelty of an idea and its framing is crucial to gaining the attention of the general public.

Experimental studies: an overview

We conducted two experimental studies designed to probe the conditions under which ideas with varying degrees of novelty are more likely to receive a favourable evaluation (attractiveness and investment propensity). In the online lab experiment of Study 1, we explored the effect of concrete and abstract construal framings on the attractiveness of novel ideas (a summary indicator of how much the participants liked the idea and how likely they are to invest in it) by changing the description of the idea in an entrepreneurial pitch deck presentation. In Study 2, we used a different idea that was presented with a longer pitch deck and investigated whether idea framing affected the investment propensity of lay evaluators (crowdfunders) – which is now measured by using a behavioural dependent variable to capture the actual propensity to invest in the idea. In both experiments, we manipulated the novelty level (incremental vs. radical) of an idea and the construal level (why vs. how) of the innovator’s framing strategy.

Study 1

In Study 1,Footnote2 participants evaluated an entrepreneurial pitch deck that was used to present an incremental or radical idea and activate a concrete or abstract thinking mode among the lay evaluators: we designed two different frames for championing the novel ideas by varying the content of their description. We then tested the moderating role of novelty level on the effect of the construal frame in the evaluative process.

Method

Participants

We conducted the experiment at a large university in Italy by recruiting 194 business students who completed the survey online. Sampled students ‘resemble the population of novice crowdfunders’ (Guarana et al., Citation2022, p. 9) and represent our population of interest: lay evaluators. The final sample included 132 students (36.4% female, Mage = 20.59 years, SD = 2.22 years) because we had to remove participants who failed an attention check question (Oppenheimer et al., Citation2009).Footnote3 Specifically, we asked them to answer whether they had read a slide about the market to ensure participants paid attention to the idea presentation. The question was: ‘In the presentation of the idea, did you read a slide about the MARKET (consumers)?’ They had two options as possible answers: (1) Yes, I read a slide about the market (consumers) or (2) No, I did not read a slide about the market (consumers).

Material and procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four conditions in a 2 (construal framing: concrete vs. abstract) x 2 (novelty: incremental idea vs. radical idea) between-subjects experiment and invited to see the pitch deck by using an online survey tool. After watching the pitch deck, participants completed the questionnaire. The pitch deck adapted from prior work (Falchetti et al., Citation2022) was used to manipulate the construal framing and the idea’s degree of novelty. All pitch decks across the four conditions consisted of five slides covering the problem, the solution, the target market, the product, and the concluding call to action. To manipulate novelty and construal framing, we varied the content of two slides in the pitch decks: the solution and the product. We manipulated the novelty of the idea in the solution slide and the construal framing in the product slide by providing the participants with additional information on the lamp ideas. This information was framed in How or Why terms depending on the experimental condition (see below for a description of the novelty and construal framing manipulation and refer to Pilot Study 1 for the manipulation checks). We then embedded the manipulations of novelty and construal framing in the pitch decks.

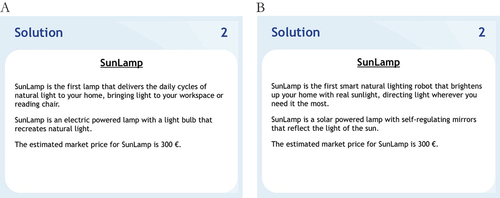

Novelty manipulation

For the novel idea, we adapted the idea from Falchetti et al. (Citation2022), while for the radical idea we used another real-case crowdfunding campaign. Both ideas refer to a lamp developed to bring natural light indoors, but differ with respect to the type of natural light the lamp delivers. One lamp recreates natural light (i.e., incremental idea), while the other lamp reflects real sunlight inside (i.e., radical idea). In the description of our study, we named both ideas SunLamp and provided an estimated market price. The price for the two ideas was held constant to control for confounds due to different price perceptions. The description for the incremental idea was: ‘SunLamp is the first lamp that delivers the daily cycles of natural light to your home, bringing light to your workspace or reading chair. SunLamp is an electric powered lamp with a light bulb that recreates natural light. The estimated market price for SunLamp is $300’. For the radical idea, the description was: ‘SunLamp is the first smart natural lighting robot that brightens up your home with real sunlight, directing light wherever you need it the most. SunLamp is a solar powered lamp with self-regulating mirrors that reflect the light of the sun. The estimated market price for SunLamp is $300’.

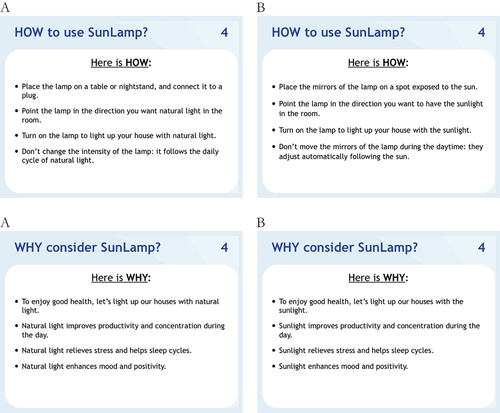

Construal framing manipulation

We manipulated the construal framing by following prior research (Falchetti et al., Citation2022; Kim et al., Citation2009; White et al., Citation2011): in the concrete framing, the product slide of the pitch deck describes the lamp focusing on how SunLamp operates; while, in the abstract framing, the product slide describes the lamp focusing on why SunLamp is beneficial. Since the two novel lamps operate in different ways, we developed a concrete framing for each idea but kept the two descriptions as similar as possible. Appendix 1 reports the pitch decks with the novelty and construal farming manipulation used in the experiment.

Manipulation checks: pilot study 1

To verify the effectiveness and independence of our novelty and construal framing manipulation, we conducted a pilot study with 190 MTurk participants. We restricted potential participants only to those located in the US with a 95% or greater approval rating on MTurk. To ensure data quality, we used a catch question and excluded responses from participants who gave the incorrect answer (Aguinis et al., Citation2021). The final sample consisted of 177 participants (53.7% female, Mage = 36.67 years, SD = 12.31 years) who were randomly assigned to one of the four conditions in a 2 (construal framing: concrete vs. abstract) x 2 (novelty: incremental idea vs. radical idea) between-subjects experiment. First, participants read the description of one of the two novel ideas. Next, they received additional how or why information about the idea. For the manipulation check of construal framing, participants indicated whether the information about the lamp was concrete (detailed) or abstract (general) on a 7-point scale (1 = very concrete; 7 = very abstract; Jin & He, Citation2013). For the novelty manipulation check, participants evaluated the novelty of the idea on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all, 7 = extremely) using the following items: novel, unique, original, creative (α = .90). We adapted these items from the Creative Product Semantic Scale (O’Quin & Besemer, Citation1989). A 2 × 2ANOVA on perceived concreteness of the information about the idea showed only a significant main effect for construal framing (F (1, 173) = 15.490, p = .000, ηp2 = .082): participants in the abstract framing construal rated the idea description as more abstract (M = 3.68, SD = 1.64) than those in the concrete framing construal condition (M = 2.78, SD = 1.36). We found no other significant effects. Next, we tested the novelty manipulation by running a 2 × 2ANOVA on the novelty rating. The analysis revealed only a significant main effect for novelty (F (1, 173) = 15.733, p = .000, ηp2 = .083): the incremental idea (M = 4.66, SD = 1.31) was evaluated as less novel than the radical idea (M = 5.39, SD = 1.11). Since we found no other significant effects, we concluded that our manipulations of the two independent variables worked well.

Measures

Dependent Variable: idea attractiveness

The dependent variable measures the attractiveness of the idea, which we captured by asking participants how much they liked the idea on a 7-point scale (1 = ‘I liked it very much’, 7 = ‘I disliked it very much’), and how likely they are to invest in the idea on a 7-point scale (1 = ‘Extremely likely’, 7 = ‘Extremely Unlikely’).Footnote4 Since the two measures were highly correlated (r = .706, p = .000), we combined them into a summative indicator that captures the attractiveness of an idea.

Results & discussion

Idea attractiveness

We run a 2 (construal framing: concrete vs. abstract) x 2 (novelty: incremental idea vs. radical idea) between-subjects ANOVA on idea attractiveness. The results showed a two-way interaction between construal framing and novelty (F (1, 128) = 7.201, p = .004, one-tailed test, ηp2 = .053). To further explore the nature of this two-way interaction, we conducted simple effects tests. These tests revealed that, in the case of an incremental idea, participants evaluated the idea as more attractive in response to the abstract framing (M = 9.79, SD = 2.57) than in response to the concrete framing (M = 8.41, SD = 2.88; F (1, 128) = 4.564, p = .018, one-tailed test, ηp2 = .034). In the case of the radical idea, we found that participants were more likely to evaluate the idea as more attractive in response to the concrete framing (M = 10.47, SD = 1.61) than in response to the abstract framing (M = 9.35, SD = 3.23; F (1, 128) = 2.778, p = .049, one-tailed test, ηp2 = .021). Overall, these results point to an interactive effect between construal framing and novelty: abstract framings increase the attractiveness of incremental ideas, while concrete framings increase the attractiveness of radical ideas. The main effect for novelty was significant (F = 3.010, p = .043, one-tailed test, ηp2 = .023), while the main effect for construal framing did not reach significance (F < 1, n.s.). See for a summary of the results, and for a graphical representation.

Table 1. Means per experimental condition (study 1).

Study 2

The second experimentFootnote5 replicates the previous results by testing the moderating effect of novelty on the construal framing in lay evaluations. We used different ideas with alternative manipulations for novelty and construal framing, and included three additional slides (the Hook, the Team, and the Revenue Model slides) in the pitch deck to increase the realism of the idea presentation. To examine our phenomenon in a realistic evaluative entrepreneurial setting, we conducted the experiment with a sample of crowdfunders. This specific subset of individuals was strategically selected to epitomise our focal population: lay evaluators. The rationale behind leveraging crowdfunders rests on their embodiment of a broad and heterogeneous collective, notably devoid of the specialised domain-specific expertise commonly possessed by professional evaluators such as venture capitalists or research and development managers. This characteristic absence of preconceived professional knowledge makes them an ideal representation of the general evaluative populace, thereby providing a robust foundation for our empirical investigation. We also created a behavioural dependent variable that measures the actual support lay evaluators are willing to offer to the idea.

Method

Participants

We recruited lay evaluators via Prolific, an online UK-based platform of high data quality (Peer et al., Citation2017), and followed the approach of recent studies that have used Prolific for experiments on early-stage investment decisions (e.g.: Dushnitsky & Sarkar, Citation2022; Zunino et al., Citation2022). To recruit a representative sample of lay evaluators, we prescreened potential participants who invested in crowdfunding in the past. We recruited a sample of 218 prescreened participants: each participant received 1 pound for completing the study. As in prior studies, we used two catch questions to detect inattention. The final sample consisted of 195 participants (37.9% female, Mage = 37.51 years, SD = 11.05 years, 73.3% full-time employed, Mwork experience = 16.03 years). shows the number of participants per experimental conditions.

Table 2. Participants per experimental condition (study 2).

Material and procedure

We employed a 2 (construal framing: concrete vs. abstract) x 2 (novelty: incremental idea vs. radical idea) between-subjects experiment. We randomly assigned participants to the construal framing and novelty conditions. Consistently with Study 1, we increased the realism of the experiment by inviting participants to evaluate an idea pitch deck, and instructing them that our aim was to obtain their opinion before launching a fundraising campaign. To show that our findings are not contingent on the chosen idea, we used a different idea – a wearable sensor – as well as different manipulations of novelty and construal framing. Before running the main experiment in Prolific, we conducted an additional pilot study to define our manipulations and create the pitch decks. We made the presentation more realistic by creating a more complete pitch deck that consisted of eight slides: the hook, the problem, the solution, the team, the market size, the product, the revenue model, and the concluding call to action slides. Like Study 1, we varied the content of the slides in the pitch decks: the hook, the solution and the revenue model slides, to manipulate the novelty of the idea; and the product slide, to manipulate the construal framing.

Novelty manipulation

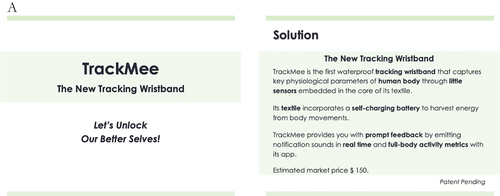

We adapted the idea concerning a new tracking wristband from Falchetti et al. (Citation2022) for the novel condition, while we used an idea about a smart bio-sensing t-shirt for the radical condition. Both ideas were named TrackMee and had the same estimated market price to control for potential confounds. The incremental idea was described as follow:

The new tracking wristband

TrackMee is the first waterproof tracking wristband that captures key physiological parameters of human body through little sensors embedded in the core of its textile. Its textile incorporates a self-charging battery to harvest energy from body movements. TrackMee provides you with prompt feedback by emitting notification sounds in real time and full-body activity metrics with its app. Estimated market price $150.

Whereas, the description for the radical idea was:

The smart bio-sensing T-shirt

TrackMee is the first washable bio-sensing t-shirt that captures key physiological parameters of human sweat and body through advanced biocompatible polymers coated in its textile. Its smart textile features a thermo-regulator fabric to maintain your body temperature constant whatever the weather conditions. TrackMee provides you with prompt feedback by changing the colour of its textile in real time and full-body activity metrics with its app. Estimated market price $150.

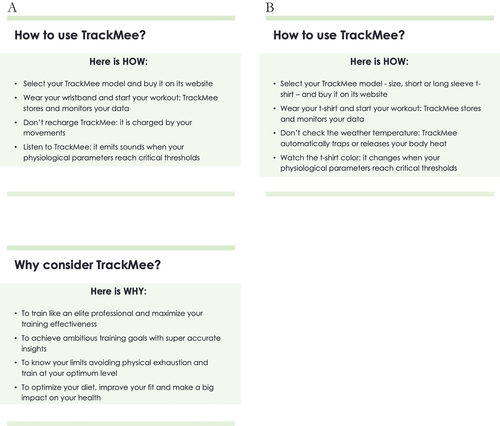

Construal framing manipulation

We manipulated the construal framing by following prior research (Falchetti et al., Citation2022; Kim et al., Citation2009; White et al., Citation2011). In the descriptions of the two wearable sensor ideas, the product slide of concrete framing condition explains how to use TrackMee, while the product slide of the abstract framing condition focus on why to use TrackMee. Like in Study 1, we developed two descriptions for the concrete framing – one for each idea – by keeping the information as similar as possible. Appendix 2 reports the pitch decks used in the experiment.

Manipulation checks: pilot study 2

We checked the effectiveness and independence of our novelty and construal framing manipulations in a pilot study with 142 participants from MTurk (we followed the same recruitment and data quality procedure of our prior pilot study). The final sample consisted of 137 participants (68.6% female, Mage = 35.70 years, SD = 12.00 years). We randomly assigned participants to one of the four conditions (radical-concrete framing idea, radical-abstract framing idea, incremental-concrete framing idea, incremental-abstract framing idea) in a 2 × 2 between-subjects experiment. Participants read the description of the wearable sensor idea with the additional how or why information. For the construal framing manipulation check, participants were asked to indicate the extent to which the information about the idea explains the reasons for its benefits on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all; 7 = extremely). For the novelty manipulation check, participants rated the idea on the same novelty scale (α = .91). A 2 × 2ANOVA confirmed the appropriateness of the construal framing manipulation: the abstract framing (M = 5.10, SD = 1.24) was perceived to explain the reasons for the benefits of the idea more than the concrete framing (M = 4.54, SD = 1.62; (F (1, 133) = 5.088, p = .026, ηp2 = .037). No other effects were significant. The novelty manipulation was also confirmed in a 2 × 2ANOVA: the incremental idea (M = 4.44, SD = 1.41) was perceived as less novel than the radical idea (M = 5.77, SD = .92; (F (1, 133) = 42.373, p = .000, ηp2 = .242)). We found no other significant effects. Thus, our manipulations were effective and independent.

Measures

Dependent Variable: investment propensity

To capture the actual support for the idea, participants were given the following choice: ‘You have earned a bonus payment of 20 cents. If you want, you can invest some of this bonus to support the development of TrackMee. How much of the 20 cents would you like to invest in TrackMee?’ They reported their choice on a sliding scale. We operationalised the measure as a dichotomous variable that is equal to 1 if participants supported the idea, and 0 otherwise.Footnote6 Transforming the measure using a logarithmic function yielded similar results. This measure was designed to capture variations in lay evaluators’’ behaviour by probing their actual intention to support the development of the idea (see Greenberg & Mollick, Citation2017).

Results & Discussion

Investment Propensity

We tested for moderation by estimating a logistic regression model on investment propensity (no support coded as 0; support coded as 1) with construal framing (concrete coded as −1; abstract coded as 1), novelty (incremental idea coded as −1; radical idea coded as 1) and its interaction as predictors. The analysis revealed a significant two-way interaction between construal framing and novelty (b = −.428, SE = .150, p = .002, one-tailed test). No other effects reached significance levels (p > .056, one-tailed test). To further explore the nature of the two-way interaction, we conducted additional analyses that produced results consistent with our prior study: for incremental ideas, participants in the abstract framing condition were more likely to support the idea than participants in the concrete framing condition: b = .515, SE = .220, p = .010 (one-tailed test); for radical ideas, participants in the concrete framing condition gave more support to the idea than participants in the abstract framing condition: b = −.342, SE = .205, p = .047 (one-tailed test). reports the results and offers a graphical representation. In summary, although Study 2 uses a different idea and a behavioural dependent variable, the results are consistent with those of Study 1: a why framing increases lay evaluators’ propensity to invest in incremental ideas, while a how framing increase their propensity to invest in radical ideas.

Table 3. Logistic regression on investment propensity (study 2).

Discussion

Novel ideas usually emerge from combining elements of otherwise disconnected categories. Many studies demonstrate that novel combinations hold the potential for great impact and change, yet they also get constant rebukes rather than support (Augier et al., Citation2015; March, Citation2010). This devaluation is intrinsic to the paradoxical nature of novelty: on the one hand, creating something genuinely new requires breaking away from existing categories, often by reconfiguring them in atypical ways; on the other, the outcomes of atypical combinations are less likely to be recognised by relevant audiences (Cutolo & Ferriani, Citation2024; Uzzi et al., Citation2013), sometimes resulting in false negatives. This paradox is particularly evident when evaluative feedback is given before any tangible product or reputational signal is available to relevant audiences (Elsbach & Kramer, Citation2003). That is why innovators have to rely on their communication skills to win audience’s support. Indeed, in many settings – pitch contests, crowdfunding, venture capital funding, film production, marketing or new product development – the potential of new ideas is assessed primarily based on subjective evaluations of the innovator’s oral or written narrative. Entrepreneurial pitches of new venturing ideas are emblematic of this persuasion effort because the only devices available to the entrepreneur at this stage of development are typically a short story and some visuals.

Our goal in this article was to investigate whether the use of concrete or abstract language is better suited for pitching ideas that vary in their degree of novelty. Tapping into the growing stream of scholarship on how innovators can strategically use language to champion their projects (Cattani et al., Citation2020; Clarke et al., Citation2019; Cutolo & Ferriani, Citation2023; Falchetti et al., Citation2022; Martens et al., Citation2007; Navis & Glynn, Citation2011), we designed two experimental studies where we analysed lay evaluators’ appreciation for ideas that vary in their degree of novelty and level of abstraction. Specifically, we found that while incremental ideas are more likely to elicit favourable evaluations when framed in abstract (why) terms than in concrete (how) ones, ideas that are perceived to be radical are more likely to elicit favourable evaluations when framed in concrete (how) than in abstract (why) terms. These findings contribute to several lines of research by offering theoretical as well as managerial insights, to which we now turn.

Previous studies in narrative persuasion have shed light on how communication devices set the cognitive and pragmatic expectations of resource holders and how different types of arguments can help entrepreneurs garner support from relevant stakeholders (Fisher et al., Citation2017; Garud et al., Citation2014; Snihur et al., Citation2022; van Werven et al., Citation2015). We complement this research by showing how the framing of an idea can be strategically construed to facilitate its reception depending on its degree of novelty. While scholars debate whether to couch novel ideas in symbolic and abstract narratives (Aldrich & Fiol, Citation1994) or anchor them in concrete details (Hargadon & Douglas, Citation2001), our experimental evidence suggests that this choice should be informed by a deeper understanding of how individual mental construals interact with the degree of novelty of those ideas. In particular, we showed that lay evaluators are more likely to appreciate incremental ideas when abstract framings focused on ‘Why to use the idea’ are used, and radical ideas when concrete framings focused on ‘How to use the idea’ are used. Framing a radical idea in concrete (how) terms or an incremental idea in abstract (why) terms ensures congruity between a lay evaluator’s mental construal and the way that idea is communicated. It is this congruency (incongruency) that lies at the core of more (less) favourable evaluative responses (Berson & Halevy, Citation2014; Falchetti et al., Citation2022; Rose et al., Citation2021) that we observe across the four possible combinations of framing strategy and idea novelty.

The findings inform recent work on entrepreneurship and CLT that has studied how abstract and concrete language affect investment decisions (Falchetti et al., Citation2022; Huang et al., Citation2021; Rose et al., Citation2021). By showing how the choice between a concrete or abstract language is contingent on the degree of novelty of the idea, we also add to recent work on construal flexibility, which highlights the importance of an individual’s ‘capacity to make construal shifts to align one’s current construal with the processing demands of the current activity or situation’ (Steinbach et al., Citation2019, p. 872). Just as a seemingly imperceptible shift in word choice may improve customer satisfaction (Packard et al., Citation2021), so the use of framing strategies that are congruent with novelty-driven mental construal can shape lay evaluators’ preferences, including their resource-allocation choices. That is why entrepreneurs should tailor their framing strategy (i.e., concrete (how) or abstract (why) frames) to the specific audience they target and the degree of novelty of their ideas.

Our study has obvious limitations that also constitute opportunities for future research. We used two controlled experiments to examine our research question. While controlled experiments have their strengths in terms of internal validity and causal inferences, our experimental design does not fully replicate crowdfunding platforms, which often include videos and images of novel ideas as well as other elements of these platforms (e.g., interactions between backers and entrepreneurs). We indeed used a minimalistic approach to present business ideas to lay evaluators by describing these ideas with pitch decks. We believe our approach represents an opportunity for future work that can extend our study by considering longer and more complex texts of actual crowdfunding campaigns. For instance, future research could test the external validity of our results by conducting a field study in which the levels of idea novelty and language abstraction are extrapolated from longer narratives using computationally based linguistic analyses (for a recent application see Cutolo & Ferriani, Citation2023). Additionally, since our focus was on lay evaluators, a natural extension of this research is to examine how framing strategies vary when ideas that differ in their degree of novelty are pitched to different audiences. For example, probing the joint effect of differences in perceived novelty and audience expertise (experts vs. lay) on how novel ideas are evaluated is an interesting avenue for future inquiry. In so doing, future research could also measure evaluators’ professional experience or similar constructs to add nuances to our findings.Footnote7

Our findings provide actionable insights that can be leveraged across a variety of situations such as pitching contests, crowdfunding campaigns, or seed-stage fundraising events where entrepreneurial success often hinges on the ability to masterfully harness linguistic prowess, captivating the attention and resources of a wide-ranging audience. Expanding the horizon of our discourse, the broader implications of our study may be extrapolated to encompass any context in which entrepreneurs are tasked with the delicate endeavour of translating groundbreaking ideas into narratives that resonate and endure. As an illustration, take the case of a tech founder bringing radically new blockchain solutions to enhance supply chain transparency in agriculture. Our research underlines that the essence of achieving such transformative engagement lies in skilfully couching the technology within a concrete framing that highlights its tangible benefits, thus better resonating with the farmers’ practical aspirations. In contrast, our findings advocate for the adoption of an abstract framing when the proposed solution represents a more incremental innovation, one that dovetails seamlessly with the established expectations within the farming community.

Beyond these entrepreneurial contexts, the ramifications of our study ripple through any evaluative landscape where strategic communication is key to reshaping perceptions of desirability. Imagine the nuanced linguistic strategies UX designers employ to present groundbreaking solutions to pressing environmental and societal issues, the inventive language marketers craft to introduce radically new products that defy conventional categorisation, or the compelling narratives screenwriters construct to capture the imagination of executive producers during pivotal pitch sessions. We leave it to future research to elucidate key language features – such as the conception of framing concreteness described in this study across multiple domains of audience interaction and novelty levels – and to examine how they relate to evaluative responses.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Schemas are cognitive structures containing ‘knowledge about a concept or type of stimulus, including its attributes and the relations among those attributes’ (Fiske & Taylor, Citation1991, p. 98).

2. We described our sampling plan, all data exclusions (see Footnote 3), all manipulations, and all measures used in the study. Data are available in the Supplementary material. The analysis was conducted with SPSS 25. This study was not preregistered, as it was run before the advent of preregistration.

3. Before performing any data analysis, we excluded 62 out of 194 participants who completed the survey (32%) because they failed the attention check. The percentage of students who failed the attention check is lower than the percentage reported in the paper by Oppenheimer et al. (Citation2009) on the use of Instructional Manipulation Checks (IMC) to detect non-diligent participants and increase statistical power and data reliability. Specifically, they conducted two studies with NYU students and reported that ‘46% of the sample failed the IMC’ in the first study, and 35% of the sample failed the IMC in the second study (Oppenheimer et al., Citation2009, respectively p. 869 and p. 870).

4. To make the results easier to interpret, we reversed the coding for both Liking and Investment Likelihood: higher values correspond to a higher liking of the idea and higher probability to invest in the idea.

5. We described our sampling plan, all data exclusions, all manipulations, and all measures used in the study. Data are available in the Supplementary material. The analysis was conducted with SPSS 25. This study was not preregistered, as it was run before the advent of preregistration.

6. We dichotomised our dependent variable because its distribution was positively skewed (Skewness = .568) and there was a high percentage of zero responses (42.6%). The bonus (20 cents) is the 20% of the payment (1 pound).

7. We did not measure professional experience or other similar variables in both of our experiments because we controlled for the evaluators’ expertise in idea evaluation by selecting only lay evaluators, that is, students or crowd funders.

References

- Aguinis, H., Villamor, I., & Ramani, R. S. (2021). MTurk research: Review and recommendations. Journal of Management, 47(4), 823–837. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206320969787

- Aldrich, H. E., & Fiol, C. M. (1994). Fools rush in? The institutional context of industry creation. The Academy of Management Review, 19(4), 645–670. https://doi.org/10.2307/258740

- Augier, M., March, J. G., & Marshall, A. W. (2015). Perspective—the flaring of intellectual outliers: An organizational interpretation of the generation of novelty in the RAND corporation. Organization Science, 26(4), 1140–1161. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2014.0962

- Barringer, B. R., & Ireland, R. D. (2012). Entrepreneurship: Successfully launching new ventures (4th ed.). Pearson.

- Berson, Y., & Halevy, N. (2014). Hierarchy, leadership, and construal fit. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 20(3), 232–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000017

- Bettman, J. R., & Sujan, M. (1987). Effects of framing on evaluation of comparable and noncomparable alternatives by expert and novice consumers. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(2), 141–154. https://doi.org/10.1086/209102

- Bolinger, M. T., Josefy, M. A., Stevenson, R., & Hitt, M. A. (2022). Experiments in strategy research: A critical review and future research opportunities. Journal of Management, 48(1), 77–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063211044416

- Boulongne, R., & Durand, R. (2021). Evaluating ambiguous offerings. Organization Science, 32(2), 257–272.1. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2020.1402

- Cattani, G., Deichmann, D., & Ferriani, S. (Eds.). (2022). The generation, recognition and legitimation of novelty. Emerald Group Publishing.

- Cattani, G., Falchetti, D., & Ferriani, S. (2020). Innovators’ acts of framing and audiences’ structural characteristics in novelty recognition. In J. Strandgaard, B. Slavich, & M. Khaire (Eds.), Technology and creativity (pp. 13–36). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chai, S., & Menon, A. (2019). Breakthrough recognition: Bias against novelty and competition for attention. Research Policy, 48(3), 733–747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.11.006

- Chan, C. R., & Parhankangas, A. (2017). Crowdfunding innovative ideas: How incremental and radical innovativeness influence funding outcomes. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(2), 237–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12268

- Clarke, J. S., Cornelissen, J. P., & Healey, M. P. (2019). Actions speak louder than words: How figurative language and gesturing in entrepreneurial pitches influences investment judgments. Academy of Management Journal, 62(2), 335–360. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.1008

- Cutolo, D., & Ferriani, S. (2023). Now it makes more sense: How narratives can help atypical actors increase market appeal. Journal of Management, 50(5), 1599–1642. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063231151637

- Cutolo, D., & Ferriani, S. (2024). Atypicality: Toward an integrative framework in organizational and market settings. The Academy of Management Annals, 18(1), 157–209.

- Dushnitsky, G., & Sarkar, S. (2022). Here comes the sun: The impact of incidental contextual factors on entrepreneurial resource acquisition. Academy of Management Journal, 65(1), 66–92. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2019.0128

- Elsbach, K. D., & Kramer, R. M. (2003). Assessing creativity in Hollywood pitch meetings: Evidence for a dual-process model of creativity judgments. Academy of Management Journal, 46(3), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.2307/30040623

- Falchetti, D., Cattani, G., & Ferriani, S. (2022). Start with “why,” but only if you have to: The strategic framing of novel ideas across different audiences. Strategic Management Journal, 43(1), 130–159. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3329

- Fisher, G., Kuratko, D. F., Bloodgood, J. M., & Hornsby, J. S. (2017). Legitimate to whom? The challenge of audience diversity and new venture legitimacy. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(1), 52–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.10.005

- Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (1991). Social cognition (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Garud, R., Schildt, H. A., & Lant, T. K. (2014). Entrepreneurial storytelling, future expectations, and the paradox of legitimacy. Organization Science, 25(5), 1479–1492. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2014.0915

- Greenberg, J., & Mollick, E. (2017). Activist choice homophily and the crowdfunding of female founders. Administrative Science Quarterly, 62(2), 341–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839216678847

- Guarana, C. L., Stevenson, R. M., Gish, J. J., Ryu, J. W., & Crawley, R. (2022). Owls, larks, or investment sharks? The role of circadian process in early-stage investment decisions. Journal of Business Venturing, 37(1), 106165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2021.106165

- Hargadon, A. B., & Douglas, Y. (2001). When innovations meet institutions: Edison and the design of the electric light. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(3), 476–501. https://doi.org/10.2307/3094872

- Herzenstein, M., Posavac, S. S., & Brakus, J. J. (2007). Adoption of new and really new products: The effects of self-regulation systems and risk salience. Journal of Marketing Research, 44(2), 251–260. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.44.2.251

- Huang, L., Joshi, P., Wakslak, C., & Wu, A. (2021). Sizing up entrepreneurial potential: Gender differences in communication and investor perceptions of long-term growth and scalability. Academy of Management Journal, 64(3), 716–740. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2018.1417

- Jin, L., & He, Y. (2013). Designing service guarantees with construal fit: Effects of temporal distance on consumer responses to service guarantees. Journal of Service Research, 16(2), 202–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670512468330

- Kim, H., Rao, A. R., & Lee, A. Y. (2009). It’s time to vote: The effect of matching message orientation and temporal frame on political persuasion. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(6), 877–889. https://doi.org/10.1086/593700

- Liu, W. (2008). Focusing on desirability: The effect of decision interruption and suspension on preferences. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(4), 640–652. https://doi.org/10.1086/592126

- Mandler, G. (1995). Origins and consequences of novelty. In S. M. Smith, T. B. Ward, & R. A. Finke (Eds.), The creative cognition approach (pp. 9–25). The MIT Press.

- March, J. G. (2010). The ambiguities of experience. Cornell University Press.

- Martens, M. L., Jennings, J. E., & Jennings, P. D. (2007). Do the stories they tell get them the money they need? The role of entrepreneurial narratives in resource acquisition. Academy of Management Journal, 50(5), 1107–1132. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.27169488

- Navis, C., & Glynn, M. A. (2011). Legitimate distinctiveness and the entrepreneurial identity: Influence on investor judgments of new venture plausibility. Academy of Management Review, 36(3), 479–499. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2011.61031809

- Oppenheimer, D. M., Meyvis, T., & Davidenko, N. (2009). Instructional manipulation checks: Detecting satisficing to increase statistical power. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 867–872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.009

- O’Quin, K., & Besemer, S. P. (1989). The development, reliability, and validity of the revised creative product semantic scale. Creativity Research Journal, 2(4), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400418909534323

- Packard, G., Berger, J., Inman, J. J., & Stephen, A. T. (2021). How concrete language shapes customer satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Research, 47(5), 787–806. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucaa038

- Peer, E., Brandimarte, L., Samat, S., & Acquisti, A. (2017). Beyond the turk: Alternative platforms for crowdsourcing behavioral research. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 70, 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.01.006

- Perry-Smith, J. E., & Mannucci, P. V. (2017). From creativity to innovation: The social network drivers of the four phases of the idea journey. Academy of Management Review, 42(1), 53–79. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2014.0462

- Rose, S., Wentzel, D., Hopp, C., & Kaminski, J. (2021). Launching for success: The effects of psychological distance and mental simulation on funding decisions and crowdfunding performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 36(6), 106021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2020.106021

- Snihur, Y., Thomas, L. D., Garud, R., & Phillips, N. (2022). Entrepreneurial framing: A literature review and future research directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 46(3), 578–606. https://doi.org/10.1177/10422587211000336

- Steinbach, A. L., Gamache, D. L., & Johnson, R. E. (2019). Don’t get it misconstrued: Executive construal-level shifts and flexibility in the upper echelons. Academy of Management Review, 44(4), 871–895. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2017.0273

- Stevenson, R. M., & Josefy, M. (2019). Knocking at the gate: The path to publication for entrepreneurship experiments through the lens of gatekeeping theory. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(2), 242–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.10.008

- Stevenson, R., Josefy, M., McMullen, J. S., & Shepherd, D. (2020). Organizational and management theorizing using experiment-based entrepreneurship research: Covered terrain and new frontiers. Academy of Management Annals, 14(2), 759–796. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2018.0152

- Su, H. J., Comer, L. B., & Lee, S. (2008). The effect of expertise on consumers’ satisfaction with the use of interactive recommendation agents. Psychology & Marketing, 25(9), 859–880. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20244

- Trapido, D. (2015). How novelty in knowledge earns recognition: The role of consistent identities. Research Policy, 44(8), 1488–1500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2015.05.007

- Uzzi, B., Mukherjee, S., Stringer, M., & Jones, B. (2013). Atypical combinations and scientific impact. Science, 342(6157), 468–472. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1240474

- Vallacher, R. R., & Wegner, D. M. (1987). What do people think they’re doing? Action identification and human behavior. Psychological Review, 94(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.94.1.3

- van Werven, R., Bouwmeester, O., & Cornelissen, J. P. (2015). The power of arguments: How entrepreneurs convince stakeholders of the legitimate distinctiveness of their ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(4), 616–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.08.001

- White, K., MacDonnell, R., & Dahl, D. W. (2011). It’s the mind-set that matters: The role of construal level and message framing in influencing consumer efficacy and conservation behaviors. Journal of Marketing Research, 48(3), 472–485. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.48.3.472

- Zunino, D., Dushnitsky, G., & Van Praag, M. (2022). How do investors evaluate past entrepreneurial failure? Unpacking failure due to lack of skill versus bad luck. Academy of Management Journal, 65(4), 1083–1109. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2018.0579

Appendices

Appendix 1 – Pitch decks for study 1

Each pitch deck was made up of five slides (the order of presentation is the number in the slide):

- the Problem (slide 1), the Target Market (slide 3) and the Conclusion (slide 5) was the same for all pitch decks:

- the Solution (slide 2) differs according to the novelty condition (respectively, incremental idea (A) and radical idea (B)):

- the Product (slide 4) differs according to the construal framing condition (respectively, how frame for incremental idea (A), how frame for radical idea (B), why frame for incremental idea (A), and why frame for radical idea (B)):

Appendix 2

– Pitch decks for study 2

Each pitch deck includes eight slides:

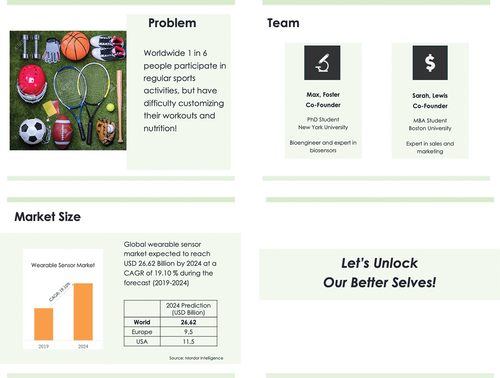

- the Problem (slide 2), the Team (slide 4), the Market Size (slide 5) and the Concluding Call to Action (slide 8) was the same for all pitch decks:

- the Hook (slide 1), the Solution (slide 3) and the Revenue Model (slide 7) differs according to the novelty condition (respectively, incremental idea (A) and radical idea (B)):

- the Product (slide 6) differs according to the construal framing condition (respectively, how frame for incremental idea (A), how frame for radical idea (B), why frame for both novel ideas):