ABSTRACT

This article discusses changes in the labor market in reference to industrial development and outlines perspectives for a set of competencies as an overall objective for technical and vocational education and training (TVET). Essential steps toward achieving this objective include a praxis-oriented approach in vocational didactics and its alignment with outcome-oriented qualification frameworks. Research on TVET is a driver for systemic development, thus supporting the process of adaptation and innovation of TVET systems. Especially, participatory action-research approaches encourage sustainable societal innovation, and generation of knowledge. The exchange of relevant knowledge is enhanced by international cooperation of the scientific community. The Regional Association of Vocational and Technical Education in Asia (RAVTE), as a network in East and Southeast Asia, is enhancing the development of TVET systems in the ASEAN region by supporting the establishment of vocational education as a scientific discipline, the education of vocational teachers, and through generation and dissemination of knowledge that can be applied by practitioners, administrators, and politicians.

JEL CLASSIFICATION CODE:

- A2: Economic Education and Teaching of Economics

- J24: Human Capital • Skills • Occupational Choice • Labor Productivity

- L31: Nonprofit Institutions • NGOs • Social Entrepreneurship

- N95: Asia including Middle East

- O15: Human Resources • Human Development • Income Distribution • Migration

- O31: Innovation and Invention: Processes and Incentives

- O35: Social Innovation

The 4th industrial revolution and the picture of humankind for future labor markets

Disruptive digital transformation affects all areas of professional, private, and social life. The rapid pace of development and change continues to increase. Advances in digitalization are changing how we live and work, and opening up new dimensions to the understanding of learning. In particular, the term Industrial Revolution 4.0 (IR 4.0) changes in the conditions of production and the role of employees brought about by digital transformation in all economic sectors. IR 4.0 creates the technological prerequisites for self-organization, self-regulation, and self-optimization of production and value-added chains (Hirsch-Kreinsen & Weyer, Citation2014, p. 5). The key technological innovation is the integration of information and communication technology into the operating plants that exchange their process data and commands. The interaction between physical and virtual processes gives rise to cyber-physical systems (CPS) (Spöttl, Gordl, Windelband, Grantz, & Richter, Citation2016, p. 27) and to the Internet of Things. The additional interlinking of privacy with social and operational processes enables the accumulation and analysis of unimaginable data (big data), which either solves or creates problems, depending on how it is used.

Increasing the efficiency of operating plants can either meet labor shortage or lead to higher unemployment; the interlinkage of vehicles both increases mobility efficiency of, and reduces, drivers’ autonomy; while smart homes lower private energy consumption and provide data from the most private of spaces. Social media can inform people and reinforce learning; or it can be used to manipulate individual decisions, and thus democratic societies. We, as societies and individuals need to be aware that we are entering a new phase of humankind that will fundamentally change our relationship to social constructs and to the societies we live in. We cannot foresee the final outcome of this ongoing development but we must be aware that this relationship needs to find a new balance in a global context.

The digital transformation of industrial production has far-reaching consequences for competence requirements of skilled or competent workers (Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, Citation2017). Recent research into sociology and qualifications conducted in Germany shows a relevant shift of qualifications and describes three scenarios (Hirsch-Kreinsen & Weyer, Citation2014):

The Downgrade Scenario predicts that CPS and artificial intelligence (AI) will substitute standardizable work tasks on operative, logistical, and administrative levels. 70% of all human operations in industrial work at an intermediate level, e.g. National Qualifications Framework (NQF) Level 5–6 could become obsolete. In the future, even centralized control functions could be transmitted to CPS and decisions will be made by AI. Remaining activities will be strongly determined by information and communication technology (ICT), with the consequence of deskilling of professions and the corresponding loss of value in the labor market (Hirsch-Kreinsen & Ittermann, Citation2017).

The Upgrade Scenario suggests that an incremental indentation of CPS and ICT will cause critical activities, such as interpreting data, making decisions, or intervening in processes will continue to be reserved for people. Dual vocational education and training (NQF 3–4) are considered a valuable pedestal qualification, which should be extended with process-oriented, strategic, and project knowledge; social and communicative competencies; as well as ICT and digital media competencies (Lee & Pfeiffer, Citation2017). Activities at the level of the low-skilled workers (NQF 1–2) can be enhanced by the use of ICT, e.g. by supporting the processing of increasingly complex tasks with data glasses. The technician level, or NQF 5–6, plays a particularly important role, mediating between the physical and virtual dimensions of work processes (Lee & Pfeiffer, Citation2017). In the form of so-called swarm organizations, this could result in a completely new form of work organization in which employees with different qualifications work together in an equal and flexible way in temporary, situationally determined, project contexts (Hirsch-Kreinsen & Ittermann, Citation2017).

The Polarization Scenario identifies a separation of qualifications through the erosion of activities at the intermediate qualifications level, which have a costly error rate and high labor costs. Polarization results from digital deskilling of simpler activities on one hand, and the upgrade of presently more demanding activities on the other (Pfeiffer, Lee, Ziring, & Suphan, Citation2016). In this scenario, low-skilled activities are often maintained for economic reasons and low-skilled laborers are instructed by digital devices and tutorials, so that internal processes and complex relationships no longer need to be understood. As a consequence, professionally skilled staff will no longer be needed at an operational level (Autor, Citation2015; Hirsch-Kreinsen & Ittermann, Citation2017). Highly qualified skills, meanwhile, will become all the more necessary in planning, design, programming, maintenance, installation, and troubleshooting. According to this scenario, the boundary between highly qualified and low-skilled jobs runs precisely through the level of skilled workers who were educated within the dual TVET system at NQF 4. Their current level of professional qualification is not sufficient for the administrative tasks of digitally networked production systems. A systematic adaptation of the dual vocational training system is advised in the form of modularized training, deploying flexible modules attuned to specific qualification requirements for individual training. In return, established job descriptions and their connectivity would no longer apply (Lee & Pfeiffer, Citation2017).

In Germany, sociologists recommended the modularization of technical and vocational education and training (TVET) when new disruptive technologies emerged. Similar recommendations were given in the context of the 3rd industrial revolution some 40 years ago and repeatedly ever since. The so-called occupation principle (berufsprinzip) has hitherto been sacrosanct and is equally protected by industry associations, unions, politicians, and vocational education scientists. Societal acceptance of the TVET system is largely dependent on the fact that the society has an idea which competencies match occupational profiles.

Labor markets are increasingly influenced by the globalized organization of work. Digital transformation will change the global organization of work and the division of labor. Artificial intelligence, robotics, and automatization will lead to a loss of jobs (Chui, Manyika, & Miremadi, Citation2016; Frey & Osborne, Citation2013; Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], Citation2016), while new and different jobs will emerge. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) predicts that lower skilled and routine skills jobs will be especially threatened in Asia (Asian Development Bank [ADB], Citation2018). For example, the garment industry will not only lose jobs but will also surrender its competitive advantage over high-wage countries, which will be tempted to remove production and exacerbate the situation in the low-skills-sector of low-income countries. On the other hand, it is assumed that the number of nonroutine jobs will increase (ADB, Citation2018), as will the demand for ICT qualifications (ADB, Citation2018). In summary, the development of the labor market within a crossover industry depends on many factors that go beyond displacement effects, increase of productivity, and reinstatement effects on a microeconomic level. The macroeconomic effect is largely dependent on the development of labor income when efficiency increases, creating secondary effects on consumer behavior, and thus on other industries. The ADB report states: ‘careful investigation of time series data spanning many decades shows these forces at play, countering the job displacement effects that arise when new technologies allow a given output to be produced by fewer workers’ (ADB, Citation2018, p. 65). Precise forecasts on the development of labor markets are almost impossible since digitalization will have an unprecedented impact on the global economy, trade behavior, and national economies. A recent study from the German Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (Citation2019), conducted by the Institute for Employment Research and the Federal Institute of Vocational Education and Training, estimates that Germany will lose approximately 1.3 million jobs until 2025, totaling 4 million by 2035. Meanwhile, new jobs will emerge: 2.1 million until 2025, and another 1 million by 2035 (Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, Citation2019).

Whatever the real situation will be with respect to labor market demand, TVET systems will have to respond to changes. In the past and until today – partly as a result of a Taylorist organization of work and education – people have been educated as homogeneous cogs in hierarchic organizations, without creative or decision-making faculties. They were supposed to function in work organizations with planning and operation separated (Rousson & Muller, Citation1981). Most educational systems worldwide are still based on a Taylorist understanding of education, making them part of the problem rather than part of the solution.

The quality of education in times of digital transformation has to find an answer that allows for a different understanding of education practices and the employment of a broad variety of learning venues and technologies (Schröder & Dehnbostel, Citation2019), which will allow equal access and create opportunities for lifelong learning. Since it is impossible to predict reliably the exact path of technological advancement or future labor market demands, TVET systems must educate learners to participate in the present and in the unpredictable future in a professionally and socially adequate manner.

The overriding objective of education and training must therefore be based on a vision that enables the individual to continue to develop throughout his or her life, making independent decisions, acting responsibly and appropriately in private, professional, and societal contexts, to shape the society of the present and future.

Modern approach to vocational didactics for various TVET learning venues

TVET systems have to respond to changes in the world of work and the acceleration of this change. Contemporary TVET systems will have to adopt a modern approach of vocational didactics that can be employed in all possible learning venues and economic sectors. Internationally, TVET systems are based on three traditions: (i) skills development with a focus on functional use in the world of work; (ii) technical education, which is mostly over theoretical and not very practical; and (iii) a combination of both approaches (Greinert, Citation1988). The third combines theory and practice, which educates and trains for present labor market demands, individual development, and lifelong learning, otherwise known as the dual–corporative TVET system with its various learning venues. Vocational education and training systems are, at best, meritocratic and permeable in order to enable the best opportunities for career development through vocational education and training. Vocational training not only raises the competence or skill level of the workforce in general, it also allows for flexible training throughout the life cycle. Permeability, recognition, and lifelong learning can be achieved if the objectives of TVET and professional didactics are consistent and interrelated so that informal, nonformal, and formal learning can be equally conceptually involved.

The NQF provides a basis for the acknowledgment of learning outcomes, irrespective of the place of learning and the learning path, through outcome orientation. In connection with validation procedures, which record vocationally acquired competencies and credit them to vocational profiles or higher education occupational profiles, the NQF forms a central requirement for lifelong learning (Schröder & Dehnbostel, Citation2019). Another important requirement is the overarching objective of vocational education: a vision of humankind living in innovative societies composed of individuals who are capable of making adequate decisions, solving problems and innovating, and continuing to develop throughout their lives. This vision requires certain competencies as a precondition.

The concept of 21st century skills aims to meet future demands on educational systems that emerge from the socioeconomic megatrends brought on by IR 4.0 (Ledward & Hirata, Citation2011; Scott, Citation2015; Trilling & Fadel, Citation2009). The sub-competencies named in the context of 21st-century skills, such as critical thinking, problem-solving, creativity, collaboration, communication, etc., are unarguably of great importance for every single human being. The concept has a general pedagogical and andragogical validity, but it needs to be specified and concretized for technical and vocational education, and integrated into a holistic concept of competencies that will embrace individuals´ responsibility and autonomy, especially if the Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, Citation2015) are to be incorporated.

The sub-competencies within the concept of 21st-century skills are also part of the model of competence for TVET that is applied in all learning venues of the dual system of TVET in Germany: the workplace, the training center, and the vocational school. This TVET-specific model of competencies, which can be traced back to Chomsky (Citation1965) in its theoretical foundation, was introduced as a result of a similar debate in the wake of the 3rd industrial revolution. In the mid-1990s, it was implemented in vocational curricula and developed a sustainable change in TVET provision toward task-based and project-oriented learning organization (Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs of the Federal States, Citation2018). According to this comprehensive model, competencies consist of knowledge, skills, and the ability and readiness for independent, adequate action. It is noteworthy in that the learning outcome for all levels of the NQF includes autonomous thinking, judging, deciding, and acting. This relates to holistic vocational tasks, which are increasing in complexity with each level. The overall objective is to work toward an individual who is able to act both proactively and adequately in the workplace, society, and family.

The German Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs of the Federal States designates three dimensions of competence: vocation-related competence (fachkompetenz) that identifies the individual in relation to his profession, social competence (sozialkompetenz) that relates the individual to his social environment, and self-competence (selbstkompetenz) that places the individual in relation to himself and his own qualities. The capacity for reflection is regarded as a subcompetence of self-competence and is a key requirement for lifelong learning. From an international perspective, it is important to understand that the German model of competencies incorporates a holistic understanding of the individual’s development, whereas the Anglo-Saxon model of competency-based training, as applied in TVET, is primarily focused on skills development.

It is crucial that the development of competencies is understood as an integral part of all vocational education and training processes in all learning venues, in holistic, explicitly not Taylorist, learning arrangements. Since competencies cannot be taught through instruction, but have to develop as the learner actively engages with a task, learning situations must be designed didactically in such a way that they have a holistic character comprising planning, decision, execution, evaluation, and reflection, in that sequence.

From a systemic perspective, the question needs to be addressed how a traditional input-oriented logic of subjects deriving from a scientific subject classification system, and an action and learning process based on work tasks and processes can be combined in a didactically sound manner to enhance experiential learning (Dewey, Citation1938).

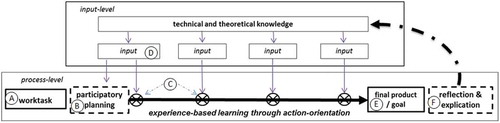

The didactical process () of combining theoretical input with an experiential action and learning process is helpful for the implementation of competence-oriented vocational didactics:

Holistic occupation-typical work tasks (A) are transformed didactically into learning tasks. Their complexity corresponds to the level of competence of the learners.

These work tasks also serve as a subject of learning, which has to be worked on in an action-oriented and experiential learning setting. Learners play an active role in planning, implementing, and evaluating work outcomes, and are granted adequate scope for decision-making and action.

Participatory planning (B) is a process in which the final result (E), work steps, resources, work equipment, etc., are jointly anticipated.

The process is carried out by the learner. Learners are confronted with challenges and problems (C) that they could not anticipate. To solve the problems, they will need information that they either find themselves or that is conveyed as input (D).

The work process is completed by a performance assessment and a qualitative evaluation of the work outcome (E) by the learners and the teacher.

The entire process concludes with a reflection (F) on selected subcompetencies, such as problem-solving, cooperation, teamwork, and vocational competencies. Furthermore, reflection allows the analysis of implicit competencies.

Didactical concepts as outlined above follow the principles of work-oriented learning if employed in vocational schools or in vocational training centers, and work-based learning in the workplace or in companies (Dehnbostel & Schröder, Citation2017). The concept of employing suitable work tasks to design learning, i.e. competence development processes, provides a sound basis for the validation and recognition of informally acquired competencies, and thus lays a basis for lifelong learning in accordance with all levels of a national qualification framework.

A precondition for a successful implementation of vocational didactics as outlined above is the analysis and identification of suitable work tasks conducive to competence development through vocational science (Schröder, Schulte, & Spöttl, Citation2013), with vocational teachers who have completed advanced training programs (Busian & Schröder, Citation2015).

TVET research as a driver for innovation

In order to enhance the development of TVET systems, specific research on TVET is essential. For regular research and systematization of knowledge, the established discipline of vocational education science is a central systemic prerequisite for development, yet is seldom taken into consideration. Vocational education scientists not only contribute to the improvement of TVET systems through participatory research approaches like action research, they should ideally gain access to internationally available knowledge in order to avoid carrying out inefficient or redundant research. They can also include their own experiences. International exchange supports the scientists in their search for answers and solutions.

In this period of disruptive digital transformation, TVET research should focus on three areas:

World of work. How is work changing? Tasks, equipment, organization? How should technical and vocational training respond?

Quality of education. What social and personal subcompetencies are required? What didactic approaches need to be established to achieve the right conditions for competence development at various learning venues and for lifelong learning?

TVET personnel. How should vocational teachers and in-company trainers be educated and trained so that they can act as agents of change? How can they best implement the objectives described above? What is the ideal didactical approach?

Sustainable systemic innovation is best achieved through participative action research conducted by local scientists who seek solutions in tune with the cultural and societal background. TVET research must therefore be regarded as a systemic element of TVET, and vocational education science must be established as a self-reliant academic discipline. Research results can be translated into policy recommendations or used for the development of systemic elements, such as teacher education, curriculum development, etc. Knowledge conducive to development can be acquired through exchange within a network, a scientific community, or communities of practice (Schröder, Carton, & Paryono, Citation2015; Wenger, Citation1998).

Digital transformation will have an extensive impact on TVET and labor markets on a global scale. TVET systems will have to innovate and adapt to technological progress. TVET researchers are required to generate the knowledge which will be conducive to development. TVET research will have to exert an effect through policy recommendations at the policy level, foster innovation at the level of TVET provision and support the dissemination of knowledge for various stakeholders. A precondition is the existence of a self-reliant academic discipline and a scientific community which generates and exchanges knowledge internationally. Since Germany has a compararatively strong scientific community in vocational education science (i.e. vocational pedagogy), which increasingly conducts research on IR 4.0 and the impact on TVET systems, the exchange with Asia can be enhanced through the Regional Association of Vocational and Technical Education in Asia. The exchange between and within regions will have a positive influence on the innovation of TVET systems in the wake of digital transformation.

Regional cooperationa s a driver of innovation

The Regional Association for Vocational and Technical Education in Asia (RAVTE) is a network of TVET-related universities that strives for exchange of TVET-relevant knowledge and common research. Founded in March 2014 in Chiang Mai, Thailand, RAVTE’s constitution defines it as a nongovernmental organization of civil society. It currently comprises 26 universities that intend to foster TVET systems in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) through research and the exchange of knowledge both within and beyond the region. The members of RAVTE share a common interest in improving TVET systems and TVET teacher education. Furthermore, RAVTE seeks to contribute to the ASEAN Economic Community through enhancing harmonization and mobility. RAVTE intends to harness action research aimed at the innovation of TVET praxis and the regional dissemination of research results (RAVTE, Citation2019). TVET@Asia (TVET@Asia, Citation2019) is an open access online journal for Technical Education and Training in Asia, which contributes toward the establishment of a regional scientific community. It is operated by RAVTE in cooperation with TU Dortmund University, Colombo Plan Staff College, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization–Bangkok, and SEAMEO VOCTECH.

RAVTE’s Strategy and Action Plan 2019–2023 includes five strategic objectives:

to increase the standardization and harmonization in compliance with the ASEAN qualification reference framework (AQRF);

to improve international and regional cooperation and to exchange knowledge and staff within ASEAN and beyond;

to secure labor-demand-driven policies and partnerships between the public and private sector in order to increase work-based learning scenarios;

to enhance the development of capacity, TVET systems innovation, and TVET research; and

to promote and secure sufficient funding for TVET systems in member countries.

Together with its member universities, RAVTE is strategically well placed to have an impact on the development of TVET systems in the ASEAN region, if political and financial backing can be secured. It could support the establishment of vocational education science as a self-reliant academic discipline and promote subsequent research approaches that are conducive to systemic innovation, as well as contribute toward more culturally sound and evidence-based policy recommendation.

In order to enhance the capacity of Asian nations for a sustainable development of TVET systems in the wake of IR 4.0, several development and research measures are recommended:

Enhancement of a regional structure that has a direct impact on technical and vocational education, on research and dissemination. Address universities who are engaged in TVET-related activities and use them as multipliers and as a resource. Strengthen their research capacities. Best practice shows that universities which provide their own research findings and recommendations can have a sustainable impact on national TVET policy development and innovation of TVET provision. The case of RAVTE shows that there is a demand (in the ASEAN region).

The development of a regional TVET strategy (in ASEAN), including the formulation of specific objectives based on Asian cultural traditions in combination with 21st century skills, would be a valuable basis for directing future development. TVET systems and higher education systems in Asia often appear to be an import from western societies that lack the integration of a culture which has deep societal roots.

Support the establishment of vocational education science as a self-reliant academic discipline at the university level, thus facilitating more innovation conducive research at a local level through participatory action research and the dissemination of knowledge and best practice. Academia in most Asian nations derives from an Anglo-Saxon tradition, which – for various reasons – doesn´t include vocational education science as a self-reliant academic discipline. In Germany, vocational education science and its community members are included in the ongoing development of the TVET system through research, exchange, dissemination, and the education of TVET experts, scientists, and vocational teachers.

Establishment of a knowledge platform for Asia on IR 4.0 and TVET that fosters the exchange of knowledge between the regions, deriving from research on TVET provision and work in the industry. Research on work tasks and processes are a precondition for the development of vocational didactics, focusing on the didactical transformation of work tasks in TVET-related action-learning environments that enhance praxis orientation and competence development. These are both preconditions for lifelong learning.

Research on IR 4.0 and its impact on the world of work are a precondition for innovation in TVET and technical education. International exchange might help to avoid redundant research, but nevertheless, action-research approaches on a local level need to be strengthened in order to adapt TVET provision in cooperation with all relevant stakeholders to local needs and conditions. It is essential to work with scientists and experts who focus on developing solutions and have the capacity to cooperate on a practical level.

Research on TVET must enter the level of TVET provision in order to contribute to the continuous innovation cycle. Societies need to provide the necessary preconditions and incentives.

Conclusion and outlook

Technical and vocational education and training systems must continue to embrace change, adapt, transform, and develop. Disruptive digital transformation will have an impact on the quantitative and qualitative demands of the labor markets globally. The unprecedented pace of change on a global scale presents a unique challenge. Further, relevant topics such as inclusion, equality, and greening also need to be addressed in transformative processes of TVET systems (Marope, Chakroun, & Holmes, Citation2015). The transformation of TVET systems is a continuous and infinite process. The question is: what preconditions can be established in order to sustain the continuous transformation and change?

A debate is needed to define an overarching objective of TVET that addresses the image of humankind. It must be specific enough to serve the various perspectives of TVET, but general enough to be applicable to all economic sectors. An overarching objective is required, which balances technical education and skills development; and which combines knowledge, skills, and autonomous responsible action in professional, private, and societal contexts on the basis of values and ethics (Maclean, Jagannathan, & Sarvi, Citation2013). Individuals are needed who embrace change and are motivated to shape new challenges in a wide spectrum of lifelong learning.

In the wake of IR 4.0, qualification research needs to be enhanced in order to examine how digital transformation impacts the work of existing vocations and professions in all economic sectors while tracking new professions as they emerge. It has to be clear that most ICT-driven technological innovations have a short life cycle. TVET curricula and training regulations need to demonstrate a readiness to adapt. TVET teachers and trainers must be educated as agents of change who embrace new technological and socioeconomic developments and can design programs accordingly. TVET teacher education will become more diverse and more sophisticated.

Action learning, based on working tasks and processes, must facilitate an approach to vocational didactics that allow application across all learning venues and establishes an outcome-oriented basis for validation methods and lifelong learning. Action learning and action research (as well as systemic consultancy) follow similar logics (Lewin (Citation1951)) and principles. Competencies can be developed in experiential learning settings.

Research capacities in TVET need to be strengthened on a truly global scale. The relevance of TVET with respect to the life span of all individuals and its systemic complexity are not mirrored by existing research capacities. An active global scientific community of practice that generates knowledge and engages in dissemination can make a major contribution to the continuous transformation process – perhaps by using advanced digital media?!

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Thomas Schröder

Thomas Schröder is director of the Institute of Educational Philosophy and Vocational Education at TU Dortmund University/Germany. He holds the Chair of International Cooperation in Education and TVET Systems. His main research areas are TVET systems and its structural elements, work-based competence development and vocational didactics, the validation of informal and experiential learning, and the development of TVET systems in an international context. Prof. Schröder belongs to the academic tradition of action research that seeks to fruitfully combine societal and systemic innovation, capacity building, research, and sustainable development. From 2011 to 2014, Prof. Schröder worked for the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH (GIZ) as director of the Secretariat of the Regional Cooperation Platform located at Tongji University/Shanghai/PR China. He supported its member universities from Chna and Southeast Asia in conducting various reform-oriented research projects, capacity building, and reforms in the field of technical and vocational education and training. The 14 member universities founded the Regional Association of Vocational and Technical Education in Asia (RAVTE) in March 2014. At present, RAVTE comprises of 27 universities from 10 nations from East- and Southeast Asia, who share a common interest in TVET systems through action research and capacity building. Prof. Schröder is a member of the RAVTE advisory board and Editor-in-Chief of TVET@Asia. In September 2016, Prof. Schröder was awarded an Honorary Doctoral degree from Rajamangala University of Technology Lanna/Thailand by her Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn from Thailand.

References

- Asian Development Bank (ADB). (2018). How technology affects jobs. In Asian development outlook 2018. Manila: Asian Development Bank. Retrieved from http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/411666/ado2018-themechapter.pdf.

- Autor, D. (2015). Why are there still so many jobs?: The history and future of workplace automation. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26(3), 3–30.

- Busian, A., & Schröder, T. (2015). Vocational teacher education at technical university of Dortmund, Germany; recommendations for interoperability of regional standards and local operation in the ASEAN-region. TVET@Asia, 5, 1–16. Retrieved from http://www.tvet-online.asia/issue5/busian_schroeder_tvet5.pdf

- Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Chui, M., Manyika, J., & Miremadi, M. (2016). Where machines could replace humans—And where they can´t (yet). San Francisco, CA: McKinsey & Company.

- Dehnbostel, P., & Schröder, T. (2017). Work-based and work-related learning—Models and learning concepts. TVET@Asia, 9, 1–16. Retrieved from http://www.tvet-online.asia/issue9/dehnbostel_schroeder_tvet9.pdf

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience & education. New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, (Eds.). (2017). Work 4.0 [white paper]. Retrieved from https://www.bmas.de/EN/Services/Publications/a883-white-paper.html;jsessionid=44E9D2BB56B8C2697FBD44290F82AA02

- Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs. (2019). BMAS-Prognose ‘digitalisierte Arbeitswelt’. Forschungsbericht 526/1K [BMAS-prognosis ´digitalized world of work´research report]. Retrieved from https://www.bmas.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/PDF-Publikationen/Forschungsberichte/fb526-1k-bmas-prognose-digitalisierte-arbeitswelt.pdf;jsessionid=37A6772F060B06C2F65D3FB5D5E422C2?__blob=publicationFile&v=1

- Frey, C. B., & Osborne, M. A. (2013). The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerization? Technological forecasting and social change. (Working Paper). Oxford, UK: Oxford Martin School.

- Greinert, W. D. (1988). Marktmodell-Schulmodell-Duales system. Grundtypen formalisierter Berufsbildung [Market model – school model – dual system. The basic models of formal TVET]. In Die berufsbildende schule (Vol. 40, pp. 145–156).

- Hirsch-Kreinsen, H., & Ittermann, P. (2017). Drei Thesen zu arbeit und qualifikation in industrie 4.0. In G. Spöttl & L. Windelband (Eds.), Industrie 4.0 -risiken und chancen für die berufsbildung (pp. 131–152). Bielefeld: Bertelsmann.

- Hirsch-Kreinsen, H., & Weyer, J. (Eds.). (2014). Wandel von produktionsarbeit—’Industrie 4.0ʹ [The change of work in production – industry 4.0]. Soziologisches Arbeitspapier, 38. Retrieved from http://www.wiwi.tu-dortmund.de/wiwi/ts/de/forschung/veroeff/soz_arbeitspapiere/AP-SOZ-38.pdf

- Ledward, B., & Hirata, D. (2011). An overview of 21st century skills for students and teachers—A summary and case study. Open Journal of Leadership, 6(1), In Pacific Policy Research Center Honolulu: Kamehameha Schools–Research & Evaluation (Ed.). Retrieved from www.ksbe.edu/_assets/spi/pdfs/21st_Century_Skills_Brief.pdf

- Lee, H., & Pfeiffer, S. (2017). Industrie 4.0-Szenarios zur Facharbeiterqualifizierung und ihrer betrieblichen Gestaltung [scenariaos of industry 4.0 for the technical and voctional education and training of skilled workers and their in-company design]. In G. Spöttl & L. Windelband (Eds.), Industrie 4.0 - Risiken und Chancen für die Berufsbildung [industry 4.0 – Risks and chances for TVET] (pp. 153–170). Bielefeld: Bertelsmann.

- Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science: Selected theoretical papers. Oxford, England: Harpers.

- Maclean, R., Jagannathan, S., & Sarvi, J. (2013). Skills development issues, challenges, and strategies in Asia and in the Pacific. In R. Maclean, S. Jagannathan, & J. Sarvi (Eds.), Skills development for inclusive and sustainable growth in developing Asia-Pacific. Technical and vocational education and training: Issues, concerns and prospects 19 (pp. 3–38). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Marope, P. T. M., Chakroun, B., & Holmes, K. P. (2015). Unleashing the potential. Transforming technical and vocational education and training. Paris: UNESCO.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2016). Tax policy reforms in the OECD Citation2016. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Pfeiffer, S., Lee, H., Ziring, C., & Suphan, A. (2016). Industrie 4.0—Qualifizierung 2025 [Industry 4.0 – Qualification 2025]. Frankfurt: Studie der VDMA Bildung.

- RAVTE (2019). Regional association for technical and vocational education in asia. Retrieved from http://www.ravte-asia.rmutt.ac.th/

- Rousson, M., & Muller, P. (1981). Arbeit, Beruf, Freizeit. Sinn und Problematik der Eingliederung des Menschen in organisierte Systeme [work, vocation, recreation - the meaning and problem of human integration into organised systems]. In F. Stoll (Ed.), Die Psychologie des 20. Jahrhunderts. XIII Anwendungen im Berufsleben [Psychology of the 20th century. XIII applications in working life (pp. 7–28). Zürich: Kindler Vlg.

- Schröder, T., Carton, M., & Paryono, P. (2015). The world of TVET networks—How international and regional networks contribute to the development of national TVET-systems.In Ministry of Education & UNESCO (Ed.), Making skills development work for the future 3–5 August 2015 (pp. 109–116). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Paper presented at the Asia-Pacific Conference on Education and Training (ACET).

- Schröder, T., & Dehnbostel, P. (2019). Enhancing permeability between vocational and tertiary education through corporate learning. In S. McGrath, M. Mulder, J. Papier, & R. Stuart (Eds.), Handbook of vocational education and training (pp. 1–24). Cham: Springer.

- Schröder, T., Schulte, S., & Spöttl, G. (2013). Vocational educational science. TVET@Asia, 2, 1–14. Retrieved from http://www.tvet-online.asia/issue2/schroeder_etal_tvet2.pdf

- Scott, C. L. (2015). The futures of learning 1—Why must learning content and methods change in the 21st century? Paris: UNESCO Education Research and Foresight. Retrieved from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000234807

- Spöttl, G., Gordl, C., Windelband, L., Grantz, T., & Richter, T. (2016). Studie Industrie 4.0—Auswirkungen auf die Aus- und Weiterbildung in der M+E Industrie [study industry 4.0 – effects on initial and further vocational education and training in the mechanical and electrical industry]. Retrieved from https://www.baymevbm.de/Redaktion/Frei-zugaengliche-Medien/Abteilungen-GS/Bildung/2016/Downloads/baymevbm_Studie_Industrie-4-0.pdf

- Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs of the Federal States. (2018). Handreichung für die Erarbeitung von Rahmenlehrplänen der Kultusministerkonferenz für den berufsbezogenen Unterricht in der Berufsschule und ihre Abstimmung mit Ausbildungsordnungen des Bundes für anerkannte Ausbildungsberufe [Guideline for the development of framework curricula of the Standing Conference of Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs for vocational teaching in the vocational school and their coordination with federal training regulations for recognised apprenticeships]. Retrieved from https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/Dateien/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2011/2011_09_23-GEP-Handreichung.pdf

- Trilling, B., & Fadel, C. (2009). 21st century skills: Learning for life in our times. San Francisco,CA: Jossey-Bass Wiley Imprint.

- TVET@Asia. (2019). TVET@Asia— The online journal for technical and vocational education and training in Asia. Retrieved from http://www.tvet-online.asia/about

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: University Press.