?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper explores whether training programs were effective in improving labor market performance of individuals, in particular wages and employment probability, in South Korea. The regression analyses using the data from Korean respondents in the Program for the International Assessment of Adults Competencies (PIAAC) survey show the strong positive effects of vocational training programs on earnings as well as on employment probability of individuals, while controlling for education, experience, and literacy skills as a proxy for unobserved ability, as well as occupation and industry. Moreover, the effects of job-training tend to be larger in older cohorts. These results suggest that against challenges posed by rapidly aging population and emergence of technological breakthroughs, Korea should promote vocational training activities and life-long learning programs, especially to the elderly.

Introduction

Many economists have emphasized the importance of human capital for economic growth (Barro & Lee, Citation2015; Lucas, Citation1988). Strong human capital has been one of the contributing factors for Korea’s economic development over the past half a century. Significant improvements in the workforce in terms of both quantity and quality have allowed the nation to achieve rapid productivity growth, catching up with advanced economies in per capita income and living standards. Along with general education, the development of vocational education and training in Korea has contributed to securing a skilled workforce.

Over the coming decades, the Korean economy will face challenges from the rapid pace of technological progress and the acceleration of population aging. A shrinking labor force is a serious threat to the economy that is already losing economic vitality. Given the high level of educational attainment of the labor force in Korea, skills development activities outside formal education through vocational training needs to be re-emphasized in human capital development under rapidly changing environment.

Against this backdrop, this paper empirically examines the role of vocational training programs in the Korean economy. Using the sample of Korean respondents from the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) survey, we explore the effects of vocational training programs on individuals’ labor market performance, in particular, related to earnings and the probability of employment. In addition, we also examine whether the effects of training vary across age cohorts. These analyses are used to suggest some policy implications for designing vocational training programs that address the major challenges of rapid demographic shift and technological breakthroughs the Korean economy faces.

The importance of on-the-job training for human capital development was highlighted by Becker (Citation1964) over 50 years ago. Since then, an extensive volume of empirical literature has investigated the impacts of job training on the labor market performance of trainees, especially wages and their probability of employment. As reviewed by Leuven (Citation2004) and Cegolon (Citation2015), most of these empirical studies confirm positive effects of training on workers’ earnings. Leuven (Citation2004) reported that on average, individuals who received vocational training earn 5 ~ 10% higher real wages than those without any vocational training activities in the UK and USA. Using individual-level data for Europe, Bassanini et al. (Citation2005) also reported that the wage effects of receiving vocational training range from 3.7% to 21.6%. The wage returns to on-the-job training were also significantly positive in developing countries (Almeida & Faria, Citation2014).

Many studies have also shown positive effects of job training on the likelihood of employment. An analysis by Organization for Economic Co-operation Development [OECD] (Citation2004) reported that participation in vocational training increases the probability of being economically active, but decreases the probability of unemployed. Picchio and van Ours (Citation2013) documented that employer-provided training has a significant and positive impact on future employability.

However, the estimates for the impacts of vocational training on labor market performance are sensitive to the data and econometrical methods. Few studies show no significant positive effects of training (Goux & Maurin, Citation2000; Pischke, Citation2001). As noted in Leuven and Oosterbeek (Citation2008) and Dostie and Léger (Citation2014), the recent studies show that the returns to vocational training are lower or turn to insignificant after unobserved characteristics correlated with training decisions are controlled.

Some studies explore the effectiveness of vocational training across age groups. Empirical studies including Berg, Hamman, Piszczek, and Ruhm (Citation2017) and Picchio and van Ours (Citation2013) documented that vocational training, especially on-the-job training, is effective in improving labor market performance including productivity and employment for both young and older workers. To be more specific, the effects of training on productivity and wages decrease with age (Bassanini, Citation2006; Dostie & Léger, Citation2014; Lang, Citation2012). The different motives of younger and older workers are possible explanations for the differential in training returns (Dostie & Léger, Citation2014; Lang, Citation2012). Haelermans and Borghans (Citation2012)’s meta-analysis, using 71 estimates from 38 studies, confirmed the wage effects of on-the-job training are positive for all workers (2.4% per course) and larger for the younger workers aged below 35. However, the studies aimed at examining job training for old employees do not always show positive wage effects. Göbel and Zwick (Citation2013) showed specific job training for old employees is not associated with higher relative productivity of these employees. The impacts of training for the elderly vary across the EU countries, as reported in Belloni and Villosio (Citation2015). Budria and Pereira (Citation2007) argued that larger training effects for the workers with longer experience are attributable to the outdated formal qualifications and skills that they acquired. They also pointed out strong bargaining power of more experienced workers as a possible explanation for the large wage benefits.

Despite the mixed effects in the economics literature, many studies in the organizational psychology training literature suggest that training designed for the elderly workforce is more effective in developing human capital, and improving labor market performance (Hedge, Borman, & Lammlein, Citation2006; Sterns, Citation1986). In addition, Kraiger (Citation2017) pointed out that age-differences in training performance such as training mastery or time to complete can be attributed to not only cognitive and physical changes in older adults, but their motivation to learn.

Many studies focusing on vocational training in Korea also document positive training effects on earnings or employment probability. Yoo and Kang (Citation2010) reported that job-related vocational training increases a worker’s earnings by 2.6 ~ 9.0% on average. The effectiveness of public training programs was also examined in Lee and Lee (Citation2005) and Choi and Kim (Citation2012). Choi and Kim (Citation2012) found positive employment effects of public training programs, in general, but they also pointed out that training has negative effects on the disadvantaged including female, less educated, and older workers. Kim and Park (Citation2015) reported that vocational training reduces the duration of unemployment but did not find supportive evidence that the training increases the individual’s employment probability. They argued that this ineffectiveness is due to short-term and inexpensive training courses, and highlighted the importance of high-quality training courses.

Building on this literature, this paper examines the labor market performance of vocational training using the PIAAC data, especially in Korea. To our knowledge, this paper is the first study to use this important data set. The PIAAC data allows us to address the bias in the estimations, caused by unobserved characteristics of individuals, enabling us to generate more accurate estimates of the impacts of training. Most importantly, this paper not only confirms positive impacts of vocational training on labor market outcomes but also reports significant training impacts for the elderly, which contrasts to the general findings of previous studies focusing on advanced economies. This implicitly supports the importance of vocational training for the elderly to keep them productive in workforce.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 overviews the development of vocational training in Korea. Section 3 describes research design – data and specifications for the analyses. In Section 4, the effects of vocational training on labor market performance in Korea are discussed. Section 5 concludes with discussion of the challenges to Korea’s life-long training programs under rapidly-changing environments.

Vocational training in Korea

Korea’s vocational training system was introduced through the Vocational Training Act of 1967. It was set up in line with National Development Plans in order to meet an increasing demand for skilled labor for industrialization in the 1960s. It aimed to nurture employees, job seekers and unemployed youth to become technicians with adequate skills. The Korean government implemented various vocational training policies to promote both quantity and quality in response to evolving demands from the industry (Lee, Citation2008).

These policies enabled the economy to satisfy the increasing manpower demands for the development of labor-intensive light industry in the early 1960s, and heavy and chemical industries in the 1970s. In particular, public vocational training focused on securing the supply of skilled workers in the heavy and chemical industries, as well as other national key industries and export industries (Lee, Citation2008). In addition, private sector involvement was actively promoted in offering trainings to their employees as well as in establishing the support system.Footnote1 Thus, over the industrialization period from 1962 to 1997, the total number of vocational trainees was 2.5 million, with about 60% of the trainees receiving on-the-job in-plant trainings.

Korea’s vocational training system faced a turning point in the 1990s with the introduction of the Employment Insurance (EI). It was established to secure the supply of skilled labor in line with industrial sophistication. The Korean government shifted the vocational training to an active labor market policy from a development policy. Its focus switched from the unskilled to the unemployed (Ra & Kang, Citation2012). Then, the vocational system was expanded to provide lifelong learning opportunities that contributed to skills development of all individuals and enabled the nation to ensure the supply of skilled workers and maintain competitiveness in the global economic market.

Current training system in Korea is classified into three categories – vocational training for the employed, vocational training for the unemployed and public training for strategic industries (). Various programs are implemented to increase training opportunities, expand the training market to private providers, and provide financial support to SMEs.

Table 1. Classification of vocational training programs in Korea.

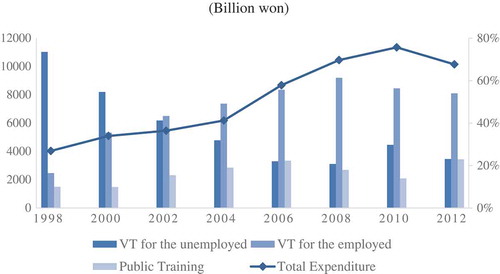

illustrates the increasing trend in the number of participants in vocational training in Korea since 1998. The number of trainees who participated in employer-provided training programs aimed at upgrading their skills/competence increased from 693,000 in 2008 to 3,477,000 in 2012. In contrast, the number of trainees in training programs for the unemployed and those for strategic industries accounted for only a small portion of the total number of participants in vocational training programs.Footnote2 This was, in part, due to the introduction of the Employment Insurance in 1995 and implementation of various measures to promote trainings for employees in SMES and temporary workers which resulted in an expansion of training opportunities for employed workers () and a reduction in training gap between large and small firms.Footnote3,Footnote4 The ratio of number of trainees from firms with less than 149 employees to total number of trainees decreased from 12.2% in percent to 29.6% in 2012 (Paik, Citation2015).

Figure 1. Trends in number of participants in skills development training. Source: Statistics of Korea (Citation2019); Original data from Employment Insurance DB.

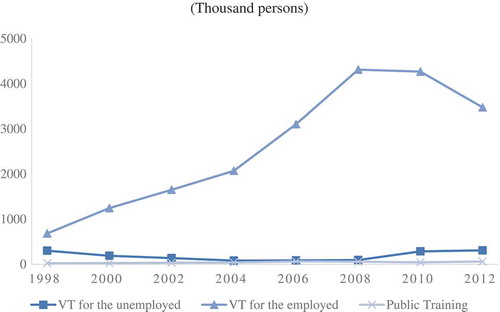

describes annual expenditure for skills development training programs from 1998 to 2012. It mostly increased from 4,034 billion KRW in 1997 to 27,170 billion KRW in 2012. For most of the years except 1998–2002, the largest proportion of the expenditure was spent on vocational training for the employed, which reflects the expansion of training opportunities and the active engagement of the businesses after the introduction of the EI. In the awake of the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997/98, more than 50% of the funds were used to implement the massive reemployment training for those who lost their jobs.

Research design

Data

This study uses the Korean sample sourced from the PIAAC survey, developed by the OECD (Citation2013b). This internationally comparable dataset is available for 24 countries and is based on the surveys of approximately 166,000 adults aged between 16 and 65. It contains 6,667 Korean respondents with their personal and employment information including age, gender, education attainment, and job characteristics. It also provides measures of adult skills proficiency in three domains – literacy, numeracy, and problem-solving in technology-rich environment.Footnote5

More importantly, the PIAAC provides detailed information about adult education and training (AET). This allows us to capture whether vocational training was effective in improving labor market performance during the 12 months preceding the survey. It classifies AET into formal and non-formal education. As defined by OECD (Citation2013a), the former indicates ‘planned education provided in formal educational institutions’, whereas the latter refers to ‘sustained educational activities’ including open or distance education, on-the-job training or training by supervisor or co-workers, seminars or workshops, and privately provided courses. AET can be also classified by reasons – job-related and non-job-related. The former is expected to improve skills, and thereby raises productivity and earnings, whereas the latter leads to skills improvement but does not necessarily improve productivity.

For the analysis, this paper focuses on non-formal job-related education, that is vocational training by definition. Only about 4.05% in our sample of the Korean respondents reported that they had participated in formal job-related education at least once during the 12 months preceding the survey, whereas 48.2% received non-formal job-related education.

We restrict our analysis to the Korean respondents aged over 25 years who had completed their formal education at the time of the survey. We exclude the respondents aged between 16 and 25 as the majority of Koreans aged between 16 and 25 are in formal education or military duty. Workers with very high reported wages are also excluded.Footnote6 After these exclusions, the sample consists of 5,481 respondents.

summarizes the characteristics of the Korean survey respondents in our sample. On average, Korean respondents were about 44.9 years old and 53.1% were females. The average hourly wage was estimated to be around 15,447 Korean Won (US$ 15.1). The mean score in the literacy test was 267 out of 500. We classify the educational attainment of the respondents into four levels – lower secondary and below, upper secondary, college, and university and above. The respondents who completed upper secondary formed the largest group, amounting to 37.2%, followed by the graduates from university and above (24.6%) and those with lower secondary and below (21.1%). The lowest share was of those with college degrees (17.0%).

Table 2. Characteristics of the Korean sample.

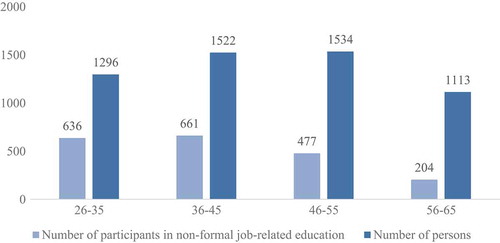

As can be seen in , the incidence of non-formal job-related education was relatively low. Only 36.1% of the respondents in the sample had participated in vocational training activities at least once in 2011/2012. describes the characteristics of the Korean respondents by participation in non-formal job-related education. It captures differences between the respondents who had participated non-formal job-related education and the non-participants. Compared to the non-participants, the participants were younger and less likely to be females, obtained a higher level of education and higher test score, and earned higher hourly wages. To be specific, the participation rate for non-formal job-related education decreased with age (). About 49.0% of the workers aged 26–35 had participated vocational training in the previous year, whereas the participants accounted for only about 18.3% of the workers aged 56–65.

Table 3. Characteristics of non-formal job-related education participants vs. non-participants in the sample.

Figure 3. Participation in non-formal job-related education by age group.

Source: PIAAC from OECD (Citation2013b)

For the analysis of wage effects of vocational training, the sample is further restricted to full-time workers, aged 25–65, who worked more than 30 hours per week. Those who are self-employed are also excluded as their wages were not reported. This reduced the sample to 2,447 respondents. The respondents in this sample had almost similar values for personal characteristics and educational background with those in the full sample.

Specifications

The following equation is adopted to examine the effects of training on labor market performance:

where:

is the labor market outcome (including wages and the probability of employment of individual i);

is an indicator of whether an individual i had taken non-formal job-related education at least once in the previous 12 months at the time of the PIAAC survey; It takes a value of either 1 or 0 representing participation or non-participation.

is a vector of workers’ characteristics including age and its squared term, indicators for female and educational levels. A female indicator represents whether a worker is female or not.

We create dummy variables for each educational level – lower secondary and below, upper secondary, college, or university and above. Our interest is to examine the parameter that indicates the effects of non-formal job-related education. In some specifications, we add industry and occupation fixed effects.

As widely known in educational research, the unobservability factor (such as ability) can cause a bias in the estimations. This is because an individual with a high level of unobserved ability has a high probability of receiving vocational training and tends to earn higher wages. To address the endogeneity bias resulting from unobserved ability, we add normalized test scores for literacy from the PIAAC as a proxy for ability.Footnote7

In addition, we further examine which age groups gained relative benefits from vocational training, through the following equation:

This Equation (2) adds an interactions term between the job training participation indicator and age group dummies

to explain how training effects differ by age groups. To identify differential training effects among the age groups, the Korean respondents in the sample were classified into four age groups

– 26–35 years, 36–45 years, 46–55 years, and 56–65 years. The parameters

and

indicate the relative training effects on earnings and employability across age groups.

We first examine the impact of vocational training on the wages, which is measured in the logarithm of hourly earnings. Some specifications add literacy skills as proxy for unobserved ability and/or industry and occupation fixed effects in order to address the omitted variable bias and the differences in characteristics across occupation and industry. Besides wage effects, as we discussed in the previous section, vocational training may have an effect on employment. We use the probability of employment, measured by an individual’s employment status in the previous week, as a dependent variable to examine the employment effects of vocational training.

Estimation results

Impacts on Korea’s vocational training on wages

reports estimation results for the wage regression, Equation (1), using the sample of full-time employees. All of the control variables for workers’ characteristics are statistically significant and show the expected signs across specifications. The coefficients of the age variable and its square term suggest an inverted U-shape relationship between age and wage. Across the specifications, females earn less than their male counterparts and the returns to schooling increase over the educational levels. Industry and occupation fixed effects are included in Columns (2) and (4) of .

Table 4. Estimation results for wage equation.

Column (1) reports the estimates of non-formal job-related education on wage with other controls. The returns to participation in non-formal job-related education in the previous 12 months are positive and statistically significant. The estimated coefficient of 0.212 indicates that taking vocational training courses raises a worker’s earnings by 21.2%. After controlling for industry and occupation, the training effects become smaller (a coefficient of 0.168) but remain significantly positive (Column (2)).

The estimate of non-formal job-related education can be biased due to the endogeneity sourced from unobserved ability. Columns (3) and (4) report the estimation results when controlling for literacy skills as unobserved ability. The coefficient for non-formal job-related education of 0.193 is positive and statistically significant. This supports the strong effect of non-formal job-related education on wages, with the skills controlled. Additionally, the estimate on skill of 0.102 is also positive and statistically significant, which suggests that one standard deviation increase in literacy scores led to a wage increases of 10.2%.

To explore whether the wage effects of training vary across age cohorts, we add an interaction term between the job training indicator and 10-year age group dummies – 26–35 years, 36–45 years, 46–55 years, and 56–65 years. reports estimation results for the wage regression with different age groups, that is Equation (2). All the control variables are statistically significant and have expected signs. As we have seen in , age has a positive effect on wages, with decreasing returns. Female workers, on average, earn less than their male counterparts, and the returns to schooling increase over the educational levels.

Table 5. Estimation results for wage equation with age cohort effects.

Column (1) of presents positive and significant returns from non-formal job-related education. The estimates for the interaction term between the job training indicator and 10-year age group dummies – 26–35 years, 36–45 years, 46–55 years, and 56–65 years – suggest that the wage effects of non-formal job-related education increase with age. The return to non-formal job-related education is 14.6% if the worker is in the age group 26–35. This indicates that when the workers aged 26–35 have received vocational training at least once during the year, their wages are higher by 14.6% compared to those who did not participate in training. The job training effect on wages for workers aged 36–45 is not significantly different from that for workers in the age group 26–35. However, the return to job training for the workers aged 46–55 is significantly larger than the return for that for the workers aged 26–35 by as much as 11.4 percentage point. The strongest effect of job training on wage is captured for workers aged 56–65. In this age group, workers who received vocational training earn 26.0 percentage point more than those aged between 26 and 35 who received vocational trainings. These results remain when the occupation and industry are controlled. These results are not consistent with the general findings of previous studies, but the evidence for larger training effects for older workers compared to younger ones is often found in some studies including Budria and Pereira (Citation2007).

To control unobserved ability, Columns (3) and (4) include the skills measured by literacy scores. While estimates for non-formal job-related education and the interaction with age dummies become smaller than Columns (1) and (2), the significantly positive effects of job training on wages and the largest effect for workers aged 56–65 remain valid.

Impacts of Korea’s vocational training on employment

reports estimation results for employment regression, using the full sample of Korean respondents. Column (1) reports the estimates of the simple employment equation with the job training indicator in the previous analysis and other individual characteristics. The skills variable is added in Columns (2) and (4) to control for unobserved ability, which can bias the estimates. The training and age group interaction term to examine the age effects of vocational training on employment probability is presented in Columns (3) and (4). The effects of age on the probability of employment also display an inverted-U shape, which is similar to the relationship between age and wages in the previous analysis. Females have a lower probability of employment than males, which is in line with the lower employment rate for females. However, the effect of education on the employment probability is not statistically significant.

Table 6. Estimation results for employment equation.

Column (1) of reports that taking non-formal job-related education programs raises the probability of employment by 28.6%. The effect of vocational training on employability still remains valid after controlling the literacy skills (Column (2)). Unlike the results from the wage regressions, the skills seem to have no impact on employability (Column (2)).

Columns (3) and (4) add interaction terms of an indicator for non-formal job-related education and four different age cohorts for Columns (1) and (2), respectively. The results in Columns (3) and (4) show that participation in non-formal job-related education has significantly positive effects on the probability of employment for workers aged 26–35. The estimates in Column (3) indicate that when a respondent aged 26–35 has participated in vocational training at least once during the year, the probability that she or he gets employed increases by 27.9%. The results show that the employment effects of vocational training are not significantly different between respondents aged 36–45 and 46–55, and workers aged 26–35. Nevertheless, the effects are significantly larger for respondents in the age group 56–65. The respondents in the 56 and 65 age group who received vocational training have a higher probability of employment by 7.6% on average, compared to those aged between 26 and 35 who received vocational training.

Challenges of vocational training in Korea

This paper examined the effectiveness of vocational training programs in improving labor market performance, in particular earnings and the probability of employment, using the Korean sample from the PIAACs. The estimation results showed that participation in non-formal job-related education has positive and statistically significant effects on earnings and the probability of employment. These strong training effects remain after controlling for skills as a measure of unobserved ability and differences in industry and occupation characteristics. In addition, we also assessed how the effects of vocational training differ by age groups and found that the positive effects of participating non-formal job-related education are larger for older cohorts.

The vocational training system in Korea has played a major role in securing the supply of skilled labor in the labor market over the industrialization period. The role of vocational training should be re-emphasized to overcome the new challenges resulting from the acceleration of population aging and the rapid advancement of technology.

The advent of digital technologies and artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming the nature of work and the workplace. Korea is one of the economies that rapidly adopted advanced technologies and replaced humans with robots in routine tasks. Indeed, it has the world’s highest density of industrial robots in the manufacturing sector in the world with 631 robots per 10,000 workers (International Federation of Robotics [IFR], Citation2018).

In this regard, in addition to general education, the vocational training system must serve a complementary role in preparing all workers with adequate skills. As a consequence, it should be enhanced to let workers keep their skills up-to-date with new technologies. This will help workers enjoy opportunities and benefits from new technologies. With the strong incentives for employees and firms to re-skill and up-skill, workers can also take continued learning opportunities voluntarily.

Nevertheless, Korea will experience dramatic shift in demographics toward a super-aged society in coming decades. According to the recent UN estimates, by 2040, people aged over 65 years will account for 31.15% of the total population of Korea, more than doubling from 12.97% in 2015 (United Nations, Citation2017). Against the demographic shift, retaining senior workers in the workplace over the normal retirement age can be an option for sustaining the supply of labor. However, many senior workers have lower productivity than prime-age workers and often belong to low-paid jobs. Without appropriate training, this can harm overall productivity and output growth. This calls for development of various vocational training activities for the older workers. This paper produced empirical evidence that vocational training in Korea has a positive effect on labor market outcomes, and these tend to larger for the older workers in Korea. These results suggested that providing vocational training opportunities can help to mitigate the negative effect of an aging workforce on productivity as workers continuously upgrade their skills in response to rapid technological progress. Ensuring access to lifelong learning programs for older workers would be invaluable in Korea. In this way, Korea should meet challenges posed by its rapidly aging population and the technological breakthroughs characteristic of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jong-Wha Lee

Jong-Wha Lee is a professor of economics at Korea University. He served as a senior adviser for international economic affairs to former President of the Republic of Korea. He was also previously Chief Economist and Head of the Office of Regional Economic Integration at the Asian Development Bank and an economist at the International Monetary Fund. He has published extensively on topics relating to human capital, growth, financial crises, and economic integration in leading academic journals. His most recent books include Is this the Asian Century? (World Scientific, 2017) and Education Matters: Global Schooling Gains from the 19th to the 21st Century, coauthored with R. J. Barro (Oxford University Press, 2015). He obtained his Ph.D. and Master’s degree in Economics from Harvard University.

Jong-Suk Han

Jong-Suk Han is a research fellow at Korea Institute of Public Finance. He obtained his Ph.D. and Master’s degree in Economics from University of Rochester. His research area is macroeconomics.

Eunbi Song

Eunbi Song is a PhD student in Economics at Korea University. Her research interests include Macroeconomics and Labor Economics. She obtained her Master's degree in Economics from Korea University.

Notes

1. Since the introduction of vocational training system in Korea, the government promoted employer-provided trainings. It provided training subsidies to the selected enterprises in the early stage of TVET development in the 1960s and enforced the firms with certain size to offer in-firm training to their employees under the levy-exemption scheme that was introduced in 1976. Over the period, 1976–1995, under the levy system, employer could either pay levy to a training fund or provide training services to their employees.

2. The EI served an important role in offering vocational training for those who lost their jobs due to the Asian Financial Crisis.

3. The Worker Vocational Competency Development Act was legislated in 2004 to offer more equitable training opportunities for SMEs and the disadvantaged including females, unemployed youth, self-employed and defectors from the North Korea.

4. The government’s support in forming a training consortium with other SMEs and training providers is one of the innovative ways to make vocational training more accessible. Please refer to Lee (Citation2016) for the details of SME.

5. The PIAAC examined the proficiency of adult cognitive skills in these three domains, measuring each skill on a 500-point scale. As discussed below, we use literacy skills as a proxy of unobserved ability, which allows us to control for an omitted variable bias in the estimations.

6. Workers whose earnings were over 100,000 won per hour (US$91.6) are excluded from the sample in order to eliminate outliers in wages at the end of the sample selection procedure. Only one outlier was removed.

7. The skills measure may not be able to clean out influences from other individual fixed effects which can affect both labor market performance and participation in vocational training. In order to solve this issue, we also adopted the IV approach by using regional dummies – measure of availability of training facilities – as instruments for participation in non-formal job-related education. However, the variables turned out to be weak instruments and the empirical results were not very satisfactory. We leave the issue of finding appropriate instruments for participation in vocational training for future research.

References

- Almeida, R. K., & Faria, M. (2014). The wage returns to on-the-job training: Evidence from matched employer-employee data. IZA Journal of Labor & Development, 3(1), 19.

- Barro, R. J., & Lee, J. W. (2015). Education matters: Global schooling gains from the 19th to the 21st century. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bassanini, A. (2006). Training, wages and employment security: An empirical analysis on European data. Applied Economics Letters, 13(8), 523–527.

- Bassanini, A., Booth, A., Brunello, G., De Paola, M., & Leuven, E. (2005). Workplace training in Europe ( Working Paper No. 1640). Bonn: The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

- Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to schooling. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Belloni, M., & Villosio, C. (2015). Training and wages of older workers in Europe. European Journal of Ageing, 12(1), 7–16.

- Berg, P. B., Hamman, M. K., Piszczek, M. M., & Ruhm, C. J. (2017). The relationship between employer-provided training and the retention of older workers: Evidence from Germany. International Labor Review, 156(3–4), 495–523.

- Budría, S., & Pereira, P. T. (2007). The wage effects of training in Portugal: Differences across skill groups, genders, sectors and training types. Applied Economics, 39(6), 787–807.

- Cegolon, A. (2015). Determinants and learning effects of adult education-training: A cross-national comparison using PIAAC data ( Working Paper No. 15-11). London: Department of Quantitative Social Science-UCL Institute of Education, University College London.

- Choi, H. J., & Kim, J. (2012). Effects of public job training programs on the employment outcome of displaced workers: Results of a matching analysis, a fixed effects model and an instrumental variable approach using Korean data. Pacific Economic Review, 17(4), 559–581.

- Dostie, B., & Léger, P. T. (2014). Firm-sponsored classroom training: Is it worth it for older workers? Canadian Public Policy, 40(4), 377–390.

- Göbel, C., & Zwick, T. (2013). Are personnel measures effective in increasing productivity of old workers? Labor Economics, 22, 80–93.

- Goux, D., & Maurin, E. (2000). Returns to firm-provided training: Evidence from French worker–Firm matched data. Labor Economics, 7(1), 1–19.

- Haelermans, C., & Borghans, L. (2012). Wage effects of on-the-job training: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 50(3), 502–528.

- Hedge, J. W., Borman, W. C., & Lammlein, S. E. (2006). Age stereotyping and age discrimination. In J. W. Hedge, W. C. Borman, & S. C. Lammlein (Eds.), The aging workforce: Realities, myths, and implications for organizations (pp. 27–48). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- International Federation of Robotics (IFR). (2018). World robotics industrial robots 2017. Frankfurt: IFR.

- Kim, Y. S., & Park, W. R. (2015). A study on the causes of long-term unemployment, effect of vocational training and schemes to improve vocational training [in Korean]. Seoul: Korean Development Institutes (KDI).

- Kraiger, K. (2017). Designing effective training for older workers. In E. Parry, & J. McCarthy (Eds.),The Palgrave handbook of age diversity and work (pp. 639–667). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lang, J. (2012). The aims of lifelong learning: Age-related effects of training on wages and job security. SOEP papers on multidisciplinary panel data research, DIW Berlin, 478/2012.

- Lee, C. J. (2008). Chapter 5: Education in the Republic of Korea: Approaches, achievements, and current challenges. In B. Fredriksen & J. P. Tan (Eds.), An African exploration of the East Asian education experience (pp. 155–217). Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Lee, K. W. (2016). Skills training by small and medium-sized enterprises: Innovative cases and the consortium approach in the Republic of Korea ( ADBI Working Paper Series No. 579). Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute

- Lee, M. J., & Lee, S. J. (2005). Analysis of job-training effects on Korean women. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 20(4), 549–562.

- Leuven, E. (2004). A review of the wage returns to private sector training. Unpublished paper.

- Leuven, E., & Oosterbeek, H. (2008). An alternative approach to estimate the wage returns to private-sector training. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 23(4), 423–434.

- Lucas, R. E. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(1), 3–42.

- Ministry of Employment and Labor and Human Resource Development Service of Korea. (2015). Regional human resource development committee: A member of a standing committee workshop. Paper presented at the Regional Human Resource Development[in Korean], Seoul.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2013a). Technical report of the survey of adult skills (PIAAC). Paris: Author.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2013b). OECD skills outlook 2013. Paris: Author.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2004). Chapter 4: Improving skills for more and better jobs: Does training make a difference? In OECD employment outlook 2004 (pp. 183–224). Paris: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development Publishing.

- Paik, S. J. (2015, June). Human resource development: The Korean experience (1950s–2000s). Presented at Mid-Career Training Program for IAS Officers: Korea Study Program, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

- Picchio, M., & Van Ours, J. C. (2013). Retaining through training even for older workers. Economics of Education Review, 32, 29–48.

- Pischke, J. S. (2001). Continuous training in Germany. Journal of Population Economics, 14(3), 523–548.

- Ra, Y. S., & Kang, H. S. (2012). Vocational training system for a skilled workforce. Seoul: KRIVET.

- Statistics of Korea (2019). Employment insurance DB. Seoul: Statistics of Korea (accessed Feb. 2019).

- Sterns, H. L. (1986). Training and retraining adult and older adult workers. In J. E. Birren, P. K. Robinson, & J. E. Livingston (Eds.), The Andrew Norman Institute series on aging: Age, health, and employment (pp. 93–113). New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Inc.

- United Nations. (2017). World population prospects: The 2017 revision. Retrieved from https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/

- Yoo, G., & Kang, C. (2010). The impacts of vocational training on earnings in Korea: Evidence from the economically active population survey. KDI Journal of Economic Policy, 32(2), 29–53.