ABSTRACT

This paper examines the role of technical and vocational education and training (TVET) in Palestine through an economic and social development lens, and identifies the lessons learned. The paper discusses the effect of TVET on employment within the notion of decent work, poverty reduction, and empowerment of youth, within a context of marginalization, extracting lessons learned and policy implications to ensure equity and inclusion in TVET and labor markets. The paper also illustrates the effect of TVET on marginalized communities. The case and experience of Palestine can be of value to other countries from various perspectives. The analysis of the marginalized groups engaged in TVET could present a framework of measurement of the effect of TVET on these different groups within a marginalized context that could be of benefit to fragile and conflict-affected states elsewhere.

Introduction

Palestine is considered a fragile state. On the one hand, it has the quasi-status of a state-in-formation. On the other, it is composed of territories that are fragmented and under military occupation, which controls the economic and social status of Palestine. Within such a context, technical and vocational education and training (TVET) has played an important role in its economic and social development, including the well-being of learners.

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, Citation2018), the occupied Palestinian territories (oPt)Footnote1 is considered one of 48 fragile states in the world, most of which are in Asia. The OECD’s multidimensional framework (2018, p. 9) attempts to capture fragility’s intrinsic complexity and frames fragility ‘as a combination of risks and coping capacities in economic, environmental, political, security and societal dimensions. It thus offers the advantage of a more comprehensive and universally relevant perspective because it takes into consideration that each context is experiencing its own unique combinations of risks and coping capacities.’ The International Labour Organization (ILO) highlights the inability of labor market actors to provide employment and decent work opportunities in fragile states (International Labour Organisation [ILO], Citation2016). The ILO has also noted that TVET is a key strategy for social and economic development within a fragile context, especially within the context of the ILO’s decent work agenda.

The TVET situation in Palestine presents a learning case for fragile countries, countries in conflict, countries in a state-building or rebuilding phase, or countries in a quasi-status. High youth unemployment and increased inequality in Palestine despite global and national economic growth has been noted by various international reports, as highlighted in the Global TVET Strategy 2016–2021 of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, Citation2016). This strategy has three priorities: fostering youth employment and entrepreneurship; encouraging member-states to set policies and carry out reforms to achieve employment, decent work, entrepreneurship and lifelong learning; and promoting equity and gender equality, which includes policies to enrich skills development among disadvantaged groups. Thus, UNESCO’s 2019 Global Education Monitoring report (UNESCO, Citation2018) highlights the importance of TVET in meeting the needs of people living under migration pressures and displacement, and uses a case study of the work of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) in providing education (including TVET) for Palestinian refugees.

This paper focuses on the empowerment and human development elements and outcomes of TVET. The paper sheds light on TVET’s contribution to economic and social development within the fragile context in Palestine by drawing on political economy theories of skills formation based on economic sociology and the new institutionalism (Brown, Citation1999; Brown, Green, & Lauder, Citation2001; Brown & Lauder, Citation1991, Citation1996; Green, Citation1997; Lauder, Brown, Stuart Wells, & Halsey, Citation1997). The paper is also in line with the growing account of TVET’s contribution to human development (Hilal, Citation2017b; Hilal & McGrath, Citation2016; Lopez-Fogues, Citation2016; McGrath, Citation2012; McGrath & Powell, Citation2015; Powell, Citation2012). As a result, the paper situates the role of TVET as going beyond economic development to also include social development and the reduction of marginalization. Thus, the paper also draws on the ILO concept of decent work, highlighting employment of workers in relation to quality, rights, and protection (International Labour Organization [ILO], Citation2012).

The next sections present the oPt and TVET contexts, followed by findings on TVET contribution to economic and social development. Challenges and enabling factors to graduates’ achievements, including decent work conditions, are then discussed.

The oPt context

The occupied Palestinian territories (oPt) are subdivided into three different zones: the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip of which Palestinians only control or partially control a small area, with 60 per cent of the West Bank, by far the largest of the three zones, almost fully under the control of Israel. The population was 4.781 million in 2017. Of this, 2.882 million live in the West Bank, 435.5 thousand in East Jerusalem, and 1.899 million in Gaza (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics [PCBS], Citation2018a). However, the three zones are largely isolated due to the imposition of a permit regime systems by the Israeli military occupation, present since 1967, which restricts the mobility of people and goods across the different areas.

This division followed the 1994 international peace treaties, called the Oslo Accords, in which the Palestinian Authority was established. It became responsible for services, such as education and health, but not sovereignty over its borders, currency, national choices, or even mobility across its own areas. This arrangement was planned to be temporary for five years, but is still in place today.

Thus, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA (Citation2018) has identified the status of the oPt as a ‘protracted protection crises’ due to the Occupation. This has severely undermined social and economic development. The economic structure of the oPt is largely comprised of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which constitute 89 per cent of the economy and are the largest employers (PCBS, Citation2018b). Informality is high in the oPt; national figures indicate that half of the businesses in Palestine are informal businesses (Al-Falah, Citation2014) while the national labor force survey (PCBS, Citation2018c) indicates that one-third of the work force is employed in the informal sector, with 59 per cent in informal employment in the oPt.

Economic conditions in the oPt are in serious decline due to the restriction on movement in the West Bank, the isolation of East Jerusalem, and the blockade in Gaza. Recently, The World Bank (Citation2019) noted that growth in 2018 slowed due to the steep deterioration in Gaza and a slowdown in the West Bank, where the economic situation is fragile, marked by increased unemployment, poverty, and restrictions to economic competitiveness:

Monetary living standards in both regions remained fragile. In the West Bank, poverty status is sensitive to even small shocks in household expenditures, while in Gaza any change in social assistance flows can significantly affect the population’s wellbeing. (World Bank, Citation2019, p. 2)

An earlier World Bank report noted how the economy was distorted by the ‘artificial reliance on donor-financed consumption’ (Niksic, Cali, & Nasser Eddin, Citation2014, p. 1), a situation that would not be necessary as the West Bank could provide the land, water, minerals and other resources needed for growth. Indeed, it is estimated that reducing restrictions on access to, and development in, the West Bank could increase the Palestinian gross domestic product (GDP) by as much as 35 per cent, paving the way toward decreasing dependency on donor support. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) has also noted the deformation of the economic structure and low productivity due to the occupation (UNCTAD, Citation2016).

The ILO (Citation2018) has reported on the effects of these issues on Palestinian people, including: a weakened Palestinian labor market, constraints on the rights of Palestinian workers, and eroded resilience of workers and enterprises. These conditions affect the population significantly and result in increasing poverty and unemployment, especially among youth. National statistics indicate that only one in three young people is in the labor force and around 40 per cent are unemployed: a prevailing reality for many years. The participation and unemployment rates for youth in Gaza are 68 and 65 per cent, respectively. However, these statistics are drastically worse for female youth as their participation in the labor force is only 12.4% per cent with an unemployment rate of 70.3 per cent (PCBS, Citation2018c). Females are also burdened with social constraints that affect their choices and could lead to their disempowerment (Hilal, Citation2017b).

Poverty rates are high among the Palestinians, reaching 29.2 per cent in the oPt, and higher in Gaza at 53 per cent (PCBS, Citation2018d). Poverty rates in Jerusalem are affected by Israeli consumption and income levels: 76 per cent of Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem (and 83 per cent of the children) live below the Israel-defined poverty level (UNOCHA, Citation2017). East Jerusalem also has very high school drop-out rates with its population and economic opportunities further restricted by demolition orders (UNOCHA, Citation2017).

The World Bank (Citation2017) report on prospects for economic growth and jobs in Palestine has identified priority actions for improving the business climate and creating jobs, including: the removal of restrictions, improvements in doing business indicators, an increased focus on vocational training to bridge the skill gap in the labor market, and accelerating land registration to fully release this factor of production into the economy.

Theoretical framework

The research upon which the balance of this paper is based (Hilal, Citation2018a) positions TVET within its social and economic roles through careful consideration of the impacts of TVET on people’s lives. This draws upon political economy theories to situate TVET beyond the traditional market-driven approach toward broader social policies (Allais, Citation2012) by analyzing skills acquisition not only as an individual act but also as social acts, such as the higher responsibilities of TVET policy makers and institutes. As such, the paper views TVET in the oPt within its own context and history given the enabling factors and challenges within national policies and institutional practices.

Thus, the paper seeks to create an understanding of marginalized groups in the oPt, and identify the contribution of TVET to reducing inequality and enriching social development. Empowerment framework within the Gender and Development (GAD) Theory (Kabeer, Citation1994, Citation1999; Mayoux, Citation2000; Moser, Citation1991, Citation1993) and the intersectionality approach (Collins, Citation1989; Crenshaw, Citation1989; Davis, Citation1983) inform the analysis of marginalization and inequality as well as pathways to social development. The notion of ‘empowerment’, which Kabeer (Citation1999) explains as a process that can bring change to those who have been denied the power of choice, is used to analyze gender and other inequalities (Hilal, Citation2017b). As such, it draws upon the human development approach and related scholarly work on contribution of TVET to human development (Hilal & McGrath, Citation2016; Lopez-Fogues, Citation2016; McGrath, Citation2012; McGrath & Powell, Citation2015; Powell, Citation2012).

Methodology

As noted above, the research underpinning this paper is based on the doctoral work of the researcher (Hilal Citation2018a). The research design included a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods, including a survey of TVET graduates, and interviews and focus group discussions with students, graduates, different TVET policy makers and stakeholders,. The research was carried in 2015, and engaged 1,240 people from West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza. These people included 764 TVETFootnote2 graduates who had graduated in 2011, four years before the field work as well as current students, teachers, counsellors, and the management staff of over 30 TVET institutes, policy makers at national and regional levels (directorates and ministries) teachers and principals of general schools, employers, community representatives, and other government officials. The TVET institutes represented the different TVET systems in Palestine: government, nongovernment organizations (NGOs), semi-government, and United Nations bodies, with the institutes and resource persons identified and selected to represent this diversity.

TVET within the context of marginalization and efforts in state building

The development of TVET in oPt began in 1948 when over 300,000 Palestinians became refugees at the establishment of the state of Israel. The UNRWA, the UN agency established in 1949 to cater to Palestinian refugees, extended TVET for the refugees. Religiously-affiliated organizations also established TVET offerings at that time as part of their support to the Palestinians, and have continued this to the present day. In the 1960s several vocational schools were started by the Jordanian government in those parts of the West Bank then controlled by Jordan, and by Egypt in Gaza. TVET in each area followed its own educational system. In 1967, when Israel occupied the West Bank including East Jerusalem and Gaza, it built Vocational Training Centres as a source for cheap labour. Following the 1994 Oslo Accords, the Palestinian Authority assumed responsibility for education, training, and TVET. Despite being rich in its diversity, the fragmented nature of the inherited TVET systems presented many challenges. A national TVET strategy was developed with the participation of all stakeholders in 1995 with a governance structure including representatives from the diversified stakeholders. Two tracks of work-based learning schemes were introduced. The first is through civil society organizations engaged in TVET to overcome mobility restrictions and construction of the Separation Wall in 2004–2006. The second track is through donor support to the government to produce relevant human resources to meet labor market demand (Hormans and Hilal, Citation2017).

For many Palestinian refugees, TVET became a tool for economic and social inclusion, which has continued until today. The Palestinian Authority’s double role in establishing systems and statehood and resisting the Israeli occupation, has shaped its policies toward TVET as a tool for integrating marginalized groups, for increasing youth employment, and for promoting economic development, as highlighted in the 2017–2022 National Policy Agenda (Palestinian Authority [PA], Citation2016).

TVET’s contribution to economic development

TVET’s contribution to economic development can be seen in several ways: (1) the employment of TVET graduates; (2) the contribution of TVET graduates to the demands of a marginalized and fragile economy; and (3) TVET’s contribution to poverty reduction.

Various tracer studies have highlighted the high participation and employment rates of TVET graduates compared to their peers who had not participated in TVET: 89 per cent participation in the labor force compared to 32.7 per cent of Palestinian youth with 77 per cent of TVET graduates being employed compared to only 59 per cent of Palestinian youth Hilal (Citation2018a). Another tracer study (Hilal, Citation2018b) conducted annually for the last 18 years has confirmed these results. TVET graduates are also more likely than other graduates to work in the private sector, or become employers or self-employed (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics [PCBS], Citation2006). Indeed, twice as many TVET graduates as others become employers or self-employed.

Labor force surveys and needs assessments conducted within various sectors indicate a very high demand for TVET graduates, including in the services, manufacturing, construction, tourism, information and communication technology (Hilal, Citation2011, Citation2013b; Citation2013b, Citation2017a, Citation2018a; Hilal, Kassis, Rantisi, & Nassar, Citation2015). This demand for TVET graduates has been confirmed in research by the Palestinian Economic Policy Research Institute (Abdallah, Citation2018; Jamil, Citation2018) and interviews with the private sector (Hilal, Citation2018a)

Like all workers in oPt, TVET graduates suffer from poor working conditions in the job market, which only begins to change three to five years after graduation and working in the profession. In the interim, however, many TVET graduates drop out of their profession and transfer to higher-paying jobs when available (Hilal, Citation2018a).

Results have also revealed the effect of these graduates on empowering the marginalized private sector in various areas in the oPt, specifically in East Jerusalem, where the effect of TVET on businesses was seen through the provision of required human resources on the one hand, and the start of own businesses in marginalized and isolated areas in East Jerusalem and Zone C of the West Bank on the other. Both have added to the resilience of communities and strengthened economic activities in these areas (Hilal, Citation2018a). This is noteworthy given that Palestine’s economic status is fragile, in addition to being challenged with lack of control over resources, borders and currency.

As such, TVET is contributing to the economic development of the oPt, and to achieving its national development goals. In his macroeconomic study of the Palestinian Economy, Nassar (Citation2018) highlighted the importance of TVET as a driving tool for the Palestinian economy.

TVET is contributing to reducing marginalization

TVET’s contribution to reducing marginalization is seen in the groups defined as marginalized and disempowered groups, which have demonstrated attraction to TVET, the empowerment effect of TVET on graduates, and the effect of reducing inequality (Hilal, Citation2017b, Citation2018a).

Marginalized groups in the oPt can be grouped into two categories (Hilal, Citation2018a). The first includes groups that are commonly identified worldwide, such as youth, women, and people with a disability (PWD), as well as the poor and school drop-outs. The second category comprises context-related vulnerable groups affected by the military occupation. This includes four main groups: a) those living within the vulnerable localities (e.g. Jerusalem, Zone C in the West Bank and Gaza); b) youth and their households economically affected by occupation measures (due to loss of land, home, and resources); c) refugees; and d) other groups (e.g. those that have lost a family member, due to death or imprisonment). The research has found that both categories of the marginalized are attracted to TVET and, through the years, have achieved success in various indicators of empowerment due to TVET and consequent employment opportunities.

For example, TVET training enabled 63.3 per cent of the graduates to reach high levels of empowerment across four sets of indicators (i.e. Power Within, Power To, Power Over, and Power With).Footnote3 This was a result of the enabling resources of TVET skills, such as paid and unpaid work and the development of economic resources. Empowerment indicators show the highest achievements in gaining internal powers and respect from surroundings, gaining extra control over household decisions, and ability to participate in public life (CitationHilal, Citation2017b, 2018a).

TVET has also contributed to poverty reduction. Over half of the graduates are contributing to family income (two out of three male graduates and almost one out of three female graduates). Around half of the families have improved their status from the time of enrollment to the point of the survey four years after graduation. This finding is important within the context of the impoverishment experienced by the Palestinians in recent years.

Challenges and enabling factors

Social, political, and economic challenges

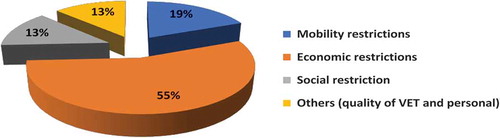

The structural challenges to the achievements of TVET graduates identified by the research included: economic challenges, mobility restrictions, social barriers, and others (). Most of the graduates faced the first two challenges, which were caused by, or aggravated, by the military occupation measures. Mobility restrictions and part of the economic challenges are context-related due to the political situation. Social challenges are related to social norms and culture that lead to negative attitudes toward women’s work, while other challenges are related to quality of TVET received. National and institutional policies were important in enabling higher achievements among graduates but could prove to be obstacles if, for example, they did not put in place measures to enable access of the marginalized to TVET, retention, and access to the labor market.

The challenge of the decent work agenda

The TVET graduates faced poor working conditions as evidenced by the fact that only one in three of the employed graduates was fully satisfied with his or her employment. Another third were partially satisfied while the remainder were unsatisfied. The reasons offered for discontent included: ‘Low pay and/or benefits’ and ‘working regulations – long hours, no flexibility’ as well as crowded work places (as most businesses in oPt are small businesses, and more than half are informal). In addition, there were mobility obstacles faced in reaching the workplace, and for some, a mismatch between their qualification and the work they could obtain.

Enabling measures

Institutional support and policy intervention were to key factors in retaining TVET graduates in their profession. Participants in the research indicated that the support provided by TVET institutes was very important in preparing them access to, and retention and further training in the labor market. This is because most TVET institutes have policies and actions for promoting access to education and training as well as measures for facilitating access to work after graduation. Institutes that were particularly successful in this had clear mandates, e.g. in training the marginalized (such as NGOs and UNRWA), serving particular marginalized groups, such as females or PWD, or who worked in the most-affected contexts (e.g. East Jerusalem and Gaza).

Policy was also seen as a supporting enabling factor. This included two types of policies: economic development policies that supported and strengthened small businesses to flourish and employ more people; and policies related to regulations and monitoring systems for TVET graduates in the labor market in order to mainstream decent work agenda. In addition, the National TVET Strategy (PA Citation1999) and its review by the MOEHE & MOL (Citation2010) have been important in supporting TVET. The activation of a national governance body for TVET in 2004 and its reactivation in 2017 after a period of instability has also proven important.

Conclusion

This paper has illustrated the framework of analysis of TVET, linking its own context and history to the overall economic and social status, and to learners’ marginalization. This approach adds a new dimension to analyzing TVET in general and in a fragile country in particular. The paper illustrated that the effect of TVET goes beyond contributing to reducing inequality among the marginalized in a fragile economy. The paper has also illustrated the context-related and policy-related challenges, as well as the policy-related enabling factors and required policy interventions. TVET must be situated within the overall political economy framework and linked to the social development scenario. It has also identified a number of lessons of relevance to the positive role that TVET can play in other fragile states. These include:

TVET in countries within a fragile context fueled by war, conflict or violence and where the population has been displaced could benefit from TVET as it provides skills for the population that has lost its livelihood resources.

Employment and income, with supporting services, can lead to empowerment of marginalized groups and reduction of inequality.

Joint government and NGO efforts can develop TVET as a tool for economic and social development for post-conflict countries and those in state building mode.

Institutional and government policies are effective in supporting youth through skills and employment, and in providing best practices for upscaling.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Randa Hilal

Randa Hilal is an expert in TVET, with long experience in the field in Palestine and the region. Randa is a practitioner, being a director of many VET institutes where she has introduced new models of training including school-based apprenticeship training and facilitated female entry into traditionally male oriented fields. She is a consultant and researcher in the field of TVET and development, and has recently accomplished her PhD studies at the University of Nottingham-UK, research title: ‘The value of VET in advancing human development and reducing inequality: The case of Palestine.

Notes

1. In certain reports, such as those of the World Bank and the OECD, Palestine is referred to as the West Bank and Gaza territories. The ‘State of Palestine’ was designated by the United Nations in 2012, although the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) report uses the Occupied Palestinian Territory definition to describe the status. In this paper, ‘oPt’ follows the definition of Hilal and McGrath (Citation2016, p. 88) as ‘occupation is a continued reality and statehood an aspiration.’

2. The paper is concerned with the three basic levels of TVET, or prior to the tertiary level. Hence is concerned with VET within the overall umbrella of TVET.

3. Empowerment indicators were subdivided into four main areas: Power Within, Power To, Power Over and Power With. This follows the notion of ‘Power’ identified by Kabeer (Citation1999) and developed further for TVET graduates (Hilal, Citation2017b, Citation2018b). Each of these four had their own detailed sets of indicators.

References

- Abdallah, S. (2018). Skills shortages and gaps in the building and construction sector in the occupied Palestinian territory. Ramallah, Palestine: Palestinian Economic Policy Research Institutes (MAS).

- Al-Falah, B. (2014). Informal sector in occupied Palestinian territories, Ramallah, Palestine. Ramallah, Palestine: Palestinian Economic Policy Research Institutes (MAS).

- Allais, S. (2012). Will skills save us? Rethinking the relationships between vocational education, skills development policies, and social policy in South Africa. International Journal of Educational Development, 32(5), 632–642.

- Brown, P. (1999). Globalisation and the political economy of high skills. Journal of Education and Work, 12(3), 233–251.

- Brown, P., Green, A., & Lauder, H. (2001). High skills: Globalization, competitiveness, and skill formation (1st ed.). New York, USA: Oxford University Press.

- Brown, P., & Lauder, H. (1991). Education, economy and social change. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 1(1–2), 3–23.

- Brown, P., & Lauder, H. (1996). Education, globalization and economic development. Journal of Education Policy, 11(1), 1–25.

- Collins, P. (1989). The social construction of black feminist thought. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 14(4), 745–773.

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex. Chicago Legal Forum, 1(8), 139–167.

- Davis, A. (1983). Women, race & class. New York, NY: Vintage Books - a division of Random House.

- Green, A. (1997). Education, globalization and the nation state. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hilal, R. (2011). Quantitative and qualitative training needs assessment of work force within the basic work levels. Ramallah, Palestine: Ministry of Education and Higher Education supported by Belgium Development Agency (BTC/Enabel).

- Hilal, R. (2013a). Labour market survey: Training needs and VET relevance gaps analysis. Ramallah, Palestine: Ministry of Education and Higher Education supported by Belgium Development Agency (BTC/Enabel). (Arabic.

- Hilal, R. (2013b). Labour market analysis and skills surveys in East Jerusalem. Jerusalem: COOPI - Cooperazione Internazionale.

- Hilal, R. (2016). Assessment of informal apprenticeship in Palestine. Ramallah, Palestine: BTC/Enable.

- Hilal, R. (2017a). Rapid needs assessment in East Jerusalem. Jerusalem: COOPI - Cooperazione Internazionale.

- Hilal, R. (2017b). TVET empowerment effects within the context of poverty, inequality and marginalisation in Palestine. International Journal of Training Research, 15, 255–267.

- Hilal, R. (2018a). The value of VET in advancing human development and reducing inequality: The case of Palestine (Unpublished Doctoral dissertation). University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK.

- Hilal, R. (2018b). LWF-VTP 2017 Graduates employment statistics. Jerusalem: The LWF World Service.

- Hilal, R., Kassis, L., Rantisi, S., & Nassar, J. (2015). Situation and capacity assessment of targeted 10 to 13 TVET and youth institutions and analysis of the relevant local job market to ensure trainings align with local market demand. Ramallah: Mercy Corps.

- Hilal, R., & McGrath, S. (2016). The role of vocational education and training in Palestine in addressing inequality and promoting human development. Journal of International and Comparative Education, 5(2), 87–102.

- Horemans, B., & Hilal, R. (2017). Closing the gap: The introduction of work based learning schemes in Palestine. TVET@Asia, Issue 9. Retrieved from http://www.tvet-online.asia/9/issues/issue9/horemans-hilal

- International Labour Organisation. (2016). Fragile states and decent work in Asia and the Pacific and the Arab States. Geneva: ILO.

- International Labour Organisation. (2018). Appendix: The situation of workers of the occupied Arab territories. Report to the Director General. International Labour Conference, 107th Session, Geneva.

- International Labour Organization. (2012). Decent work indicators: Concepts and definitions. ILO manual. Geneva: Author.

- Jamil, M. (2018). Developing the competitiveness of Palestinian products and increasing its market share: Furniture sector in the occupied Palestinian territory. Ramallah- Palestine: Palestinian Economic Policy Research Institutes (MAS).

- Kabeer, N. (1994). Reversed realities. London, UK: Verso.

- Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change, 30(3), 435–464.

- Lauder, H., Brown, P., Stuart Wells, A., & Halsey, A. (1997). Education, culture, economy, society (1st ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Lopez-Fogues, A. (2016). A social justice alternative for framing post-compulsory education: A human development perspective of VET in times of economic dominance. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 68(2), 161–177.

- Mayoux, L. (2000). From access to empowerment: Gender issues in micro-finance. CSD NGO Women's Caucus Position Paper for CSD-8, 2000. Retrieved from https://earthsummit2002.org/wcaucus/Caucus%20Position%20Papers/micro-finance.pdf

- McGrath, S. (2012). Vocational education and training for development: A policy in need of a theory? International Journal of Educational Development, 32(5), 623–631.

- McGrath, S., & Powell, L. (2015). Vocational education and training for human development. International Journal of Educational Development, 50, 12–19.

- Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MOEHE) and Ministry of Labour (MOL). (2010). Winning for a future, chances for our youth: Revised TVET strategy. Ramallah, Palestine: MOEHE and MOL.

- Moser, C. (1991). Gender planning and development. London, UK: Routledge.

- Moser, C. (1993). Gender planning and development: Theory, practice and training. London, UK: Routledge.

- Nassar, T. (2018). The future of the Palestinian economy: The role of aid. (Unpublished Doctoral dissertation). Universidad Autonoma De Madrid, Madrid, Spain.

- Niksic, O., Cali, M., & Nasser Eddin, N. (2014). Area C and the future of the palestinian economy. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- OECD. (2018). States of fragility 2018 highlights. OECD-DCD.

- Palestinian Authority (PA). (1999). TVET National Strategy. Ramallah, Palestine: PA.

- Palestinian Authority (PA). (2016). National policy agenda (2017–2022). Ramallah, Palestine: PA.

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS). (2006). Graduates’ survey of higher education and TVET: Main findings. Ramallah, Palestine. (Arabic): PCBS.

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS). (2018a). Population, housing and establishment census 2017: Census final results summary 2017. Ramallah, Palestine: PCBS.

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS). (2018b). Population, housing and establishments census 2017, final results—Establishments report. Ramallah, Palestine: PCBS.

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS). (2018c). Labour force survey: Annual report 2017. Ramallah, Palestine: PCBS.

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS). (2018d). Main findings of living standards in Palestine (expenditure, consumption and poverty), 2017. Ramallah, Palestine: PCBS.

- Powell, L. (2012). Reimagining the purpose of VET – Expanding the capability to aspire in South African further education and training students. International Journal of Educational Development, 32(5), 643–653.

- The World Bank. (2017). Prospects for growth and jobs in the Palestinian economy—A general equilibrium analysis. World Bank Group.Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/952571511351839375/pdf/121598-WP-P159645-PUBLIC-PALESTINEPROSPECTSFORGROWTHANDJOBS.pdf

- The World Bank. (2019). Palestinian Territories recent developments. Retrieved from http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/904261553672463064/Palestine-MEU-April-2019-Eng.pdf

- UNCTAD. (2016). Report on UNCTAD assistance to the Palestinian people: Developments in the economy of the occupied Palestinian territory. Geneva. Retrieved from http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/app2016d1_en.pdf

- UNESCO. (2016). Strategy for technical and vocational education and training (TVET) (2016–2021). Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- UNESCO. (2018). Global education monitoring report 2019: Migration, displacement and education – Building bridges, not walls. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA). (2017). 50 years of occupation—Occupied Palestinian territories. Humanitarian facts and figures. New York, NY: UNOCHA.

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA). (2018). Occupied Palestinian territories Humanitarian Fund (oPt HF) annual report 2018. New York, NY: UNOCHA.