ABSTRACT

This article explores the academic identities of college educators of higher education in vocational institutions. Qualitative semi-structured interviews generated data from eleven educators in five vocational education institutions. Discourse analysis revealed that educators distinguished their vocational institutions’ contributions to HE as different, but equal or superior to those of universities. Educators presented their culture and practices in advantageous ways, contrasted against imagined stereotypes of university experiences, which are perceived to be deficient for supporting the types of students they teach. In adopting academic identities that distinguish their cultures and practices from those presumed prevalent in universities, these educators seek parity of esteem with universities through distinctiveness, and reject research-focused academic identities and academic drift. In embracing teacherly identities supporting students rather than the research-teaching nexus, educators may be contributing to the ‘therapeutic turn’, diminishing opportunities for students, and furthering the vertical stratification of institutions within the Australian HE space.

Introduction

Globally, as governments pursue their economic and equity agendas in widening access to higher education (HE), new types of non-university providers of undergraduate programs are entering the HE space. In Australia, new provider institutions of higher education, that we are naming Higher Education in Vocational Education institutions (HEiVI), are providing Bachelor qualifications within the Technical and Further Education (TAFE) system. In many other countries, such as the UK and North America college-based HE has been tasked with opening up access to HE because historically large number of students from low Socio-Economic Status (SES) backgrounds are already participating in these institutions on vocational education and training programs (Webb et al.Citation2017). Widening access to higher education is understood as fulfilling a social equity remit by raising the qualification levels and employment opportunities for new types of graduates, learners from disadvantaged backgrounds (Wheelahan et al., Citation2012). Whether or not the expansion of HEiVI in Australia also widens access to higher education and creates new forms of institutional diversity in the system are the concerns of a larger project from which this analysis of academic identities for this article has been derived.Footnote1

By exploring the academic identities of educators engaged in leading and teaching higher education programs in vocational institutions, this article will contribute to discussions about whether or not the expansion of the system through growing college-based HE is reducing social inequalities. Specifically, the article considers how HEiVI educators’ academic identities indicate whether there is greater institutional horizontal differentiation or whether the growth of HEiVI is exacerbating existing institutional hierarchies and vertical stratification and inequalities within the system between universities and non-university HE providers. As Marginson (Citation2016) has argued as higher education systems have expanded, the concerns in high participation systems turn away from providing access to questions about what is being accessed. Consequently, the expansion of higher education in vocational institutions in Australia provides an intrinsically interesting case (Flyvbjerg, Citation2006) to explore how educators’ academic identities might be implicated in the form of higher education being developed in these non-university spaces. Gaining an appreciation of educators’ academic identities, through exploring the work cultures and practices they are engaged in and asking about how they identify with this work, will inform whether or not the expanded higher education system is increasingly vertically stratified or horizontally differentiated.

Key concerns in this article are whether new providers can offer an HE experience and degrees that have the socio-cultural value and status required to meet their social equity goals (A.-M. Bathmaker, Citation2017). Implicit in these questions is a question about parity of esteem in the expanded system, that is, are these new providers becoming like universities. Are these new providers engaging in a process of upward academic drift with the attendant possibility that they may be offering a lower status form of HE – thus contributing to vertical stratification of the system; or are these providers developing a distinctively different form of higher education – leading to horizontal diversity in the system? To gain insights into what is seen as distinguishing HEiVI institutions, and the cultural tensions that play-out and help shape HE, we explored the construction of academic identity through interviews with staff in education roles in five Australian HEiVI institutions across three states. We asked: ‘What academic identities are being built for those teaching in HEiVI institutions?’ and ‘How do these identities relate to the context in which higher education in vocational education is being offered?’ A discourse analysis of the interviews made it possible for us to explore the implicated ways of being, valuing, seeing, doing and believing (see Gee, Citation2011a) in HEiVI institutions through the sense-making activities of the educators interviewed. Our qualitative research reveals how, in distinguishing HEiVI institutions’ contributions to HE, the college educators interviewed built academic identities that value particular relationships with students, knowledge and pedagogy. Of interest are questions of whether HE is being framed in ways that narrow possible understandings of academic identities and HE experiences. This article does not consider in detail who the students are as our focus is identity through the lens of the teaching staff. However, we note that the wider research that this study is part of has demonstrated that Bachelor degrees in TAFEs are often in different fields of education to those of public universities, and they recruit different students (Webb et al., Citation2019).

To contextualize the concerns of this article in the field, we begin with the broader context of HEiVI and then look at literature that highlights the tensions pertaining to the HEiVI context, tensions that arise from offering HE that is distinctly vocational in focus, while embracing ‘academic-ness’.

The expansion of the HE system

Expansion of higher education has become commonplace in developed economies as a well-educated and highly skilled population, as human intellectual capital, is considered a core aspiration to securing economic advantage in the global knowledge market (Avis & Orr, Citation2016; Gale & Tranter, Citation2011; Griffioen & de Jong, Citation2013; Parry, Citation2009). This skills agenda narrative also positions employability skills as an essential equity mechanism in creating and accessing individual and national prosperity (Avis & Orr, Citation2016; Bathmaker, Citation2017; Gale & Tranter, Citation2011; Parry, Citation2009; Sellar et al., Citation2011). It is argued that access to higher education (HE) addresses social inequality through creating economic advantage and social mobility – as increased employment opportunities and higher salaries (Fisher, Citation2006; Marginson, Citation2011; Naidoo & Williams, Citation2014; Sellar et al., Citation2011). There are however challenges and tensions for new providers in offering HE provision that has characteristics and functions distinct from those of a university, while striving to meet the requisites of delivering a curriculum, experience and qualification that has equivalent value. These challenges and tensions can be traced in literature on ‘academic drift’ from the late 1970s onward (Teichler, Citation2008).

Academic drift

For over forty years, academic drift has been investigated in many countries in Europe and beyond (Tight, Citation2015). As we are not theorizing academic drift by analyzing how system expansion and change affects the mission and purpose of institutions as others have (Kyvik, Citation2007), a broad definition of academic drift satisfies our interest in how the concept has shaped the construction of non-university provision, and academic identity as a socially constructed notion. For our purposes, academic drift is defined as the tendency to strive for ‘academic-ness’ and a move away from a practical/vocational focus towards achieving the ‘status, recognition and rights’ of universities (Griffioen & de Jong, Citation2013, pp. 174–175).

Early studies on academic drift highlighted this concept as a key element of concern when HE education systems expand and new non-university providers enter the system. Neave (Citation1978, Citation1979) describes how the expansion the HE system in the UK and a number of European countries was anticipated as fulfilling an economic and social equity remit that universities did not provide. Unlike universities, polytechnics (and similar institutions), were seen as offering responsiveness to industry requirements and student demand, and as providing ‘a chance to “late developers” or those with qualifications not deemed suitable for university entry.’ (Neave, Citation1978, p. 106). However, in seeking to resemble universities, these new institutions moved away from their original objectives; a commitment to vocationalism, to the local community and to their traditional student base of working-class students (Neave, Citation1978).

Contemporary research reveals that HEiVI institutions are understood as fulfilling similar socio-economic objectives for their local communities and are valued as making similar distinctive contributions to education (Callan & Bowman, Citation2015; Henderson, Citation2018; Wheelahan et al., Citation2012, Citation2009). So, a question that arises about the practices that distinguish HEiVI is, in part, underpinned by concerns about academic drift eroding HEiVIs’ distinctive contribution to HE and undermining its economic and social equity objectives to local communities. The potential power of academic drift to do this has been discussed as driving the transformation of UK polytechnics into universities in the 90s (Gellert, Citation1993; Stanton, Citation2009; Tight, Citation2015). The control of academic drift, through its sensitivity to socio-political contexts, has also become a much researched theme (Tight, Citation2015). In Australia, for example, where the Dawkins report in 1988 led to the national unified system of universities combining with colleges of advanced education, the government emphasis on ‘system differentiation through research evaluation’ is seen as effective in controlling drift (Gellert, Citation1993, p. 82). A consequence, however, of this limit to academic drift within a unified system has been to increase vertical stratification between higher education providers, a tendency that maybe exacerbated further by the entry of non-university providers to the higher education system.

The control of staff drift, in the context of institutions maintaining distinctions between universities and non-university providers, brings into focus debates that seek to understand and define HE (Bathmaker, Citation2016; Lea & Simmons, Citation2012; Parry et al., Citation2012) and academic identity (Archer, Citation2008; Clegg, Citation2008; Feather, Citation2010, Citation2016; Harris, Citation2005). In defining these elusive notions, research seeks to identify what constituted the higher-ness of the institutions and their practices and staff identities, and to what must be present if a ‘HE experience’ is to deliver social equity.

Teaching, scholarship and research – keystones of HE and academic identity?

Much of the literature on academic identity and theories of identity suggests that shared and competing professional/social practices and relationships feature in shaping identity. Therefore, it is important to consider how academic identity is being shaped by tensions arising from HEiVI institutions seeking to distinguish their provision, from that of universities in the HE field and other VET providers, while also striving for legitimacy in the expanded HE space. The traditional keystones of HE – research, scholarship and teaching – feature strongly in literature on the construction of academic identity and HE culture. In an increasingly diverse HE sector, these keystones are both framed as identifying practices and points of contention.

In a number of European countries, non-university providers, who were previously teaching-only institutions are now expected to engage in research, while emphasizing their distinctiveness from universities (Griffioen & de Jong, Citation2013). However, this literature shows there is a retention of past non-university non-research cultures that pushes against expectation of the institution to be more research focused (Griffioen & de Jong, Citation2013). So, while there may be a push towards research activities to gain parity with prominent universities, some institutions working in the expanded HE field may hang on to aspects of their teacher-oriented culture and practices. Are these institutions seeking to counter academic drift, perhaps because a move towards a research focus is perceived as threatening underpinning values, cultures and practices that are more ‘teacherly’ and teaching focused? Research that has found a ‘research focus’ is positioned against a ‘teaching focus’ by drawing on representations of university elitism – representations of the university, research activities and university educators as elitist – may offer some support to this argument (Feather, Citation2016; Henderson, Citation2018; Snowden & Lewis, Citation2015; Wheelahan et al., Citation2012).

That the research focus is perceived as threatening non-university sector values, culture and practices can be seen in recent literature on the expansion of HE in VET in UK institutions, since the early 2000s. This literature indicates that there is evidence of a different non-research HE culture (Feather, Citation2010), and a culture in which teachers are dual professionals with complex and competing identities (Avis & Bathmaker, Citation2005; Bathmaker, Citation2016; Springbett, Citation2018). This research suggests that dual professionals are immersed in a culture that values teaching practice over educational theory (Avis & Bathmaker, Citation2005; Springbett, Citation2018) and where the emphasis on vocational expertise and teaching practice makes developing an academic research identity unlikely (Orr & Simmons, Citation2010; Springbett, Citation2018). There would appear to be attempts within college-based higher education institutions to manage academic drift by managing academic identities. Such institutions appear to homogenize teachers across their mixed sector provision of VET and HE, perhaps to manage down staff aspirations for academic status and quell discord that might arise from perceptions of status differences within the institution.

Teachers may teach across HE and FE/VET staff (Springbett, Citation2018; Wheelahan et al., Citation2012, Citation2009) and they may have the same employment conditions, salaries and workloads (Feather, Citation2010; Springbett, Citation2018; Wheelahan et al., Citation2009). Springbett (Citation2018) highlights that teachers in further education colleges (FECs) are unlikely to have a higher degree and that pursuing higher education qualifications is unlikely to be supported by the institution. This is a point of difference between HEiVI provision in England and Australia, as in Australia teaching staff must have a qualification above the level taught and be given time for scholarly activities (Callan & Bowman, Citation2015; Wheelahan et al., Citation2009). Although, research suggests that Australian HEiVI institutions may be relying on a pool of highly qualified casual staff to teach HE subjects, niche subjects that are not the focus of universities (Callan & Bowman, Citation2015).

Student academic support and pastoral care also feature strongly as part of an educators’ role, and are distinguishing features of HEiVI along with strong connections to industry and an applied focus (Henderson, Citation2018; Wheelahan et al., Citation2009). However, the emphasis on a providing a comfortable learning experience can be seen as problematic. This is because this emphasis is linked to the commodification of HE and the positioning of students as sovereign consumers, whose satisfaction supersedes educational concerns (Feather, Citation2010; Molesworth et al., Citation2009). This emphasis is also seen as fostering the ‘therapeutic turn’ in education, which is theorized as constructing students from disadvantaged background as vulnerable diminished subjectivities (Ecclestone & Rawdin, Citation2016) and deficit learners (Archer, Citation2007). The ‘therapeutic turn’ is also understood to position educators as addressing social equity through demonstrating care for vulnerable students (Ecclestone & Brunila, Citation2015; Ecclestone & Rawdin, Citation2016). Brooks highlights how in English HE policy documents the vulnerable student (disadvantaged background students) is used to frame institutions and teachers that prioritize research at the expense of teaching as not meeting their obligations in widening participation (Brooks, Citation2018, p. 749). This suggests that the teacher is being polarized on a ‘good teacher’ – ‘bad teacher’ continuum that corresponds to the keystones of HE and the teaching-research nexus.

The literature reviewed suggests that identity is a slippery notion. This relates in part to the fluidity and multiplicity of identity. In this paper identity is theorized as a socio-cultural construction, situated within the unfolding context (Gee, Citation2011a, Citation2011b; Hall, Citation1997b). We also understand identity as caught up in our lived experiences (Gee, Citation2001, Citation2011b) and connected with feelings, values and beliefs and actions, which play out as acts of affiliation and contestation as we position and represent ourselves and others, through discourse and in discourse practices (Hall, Citation1985, Citation1997a).

The literature demonstrates the variation in academic identification across higher education institutions with the three keystone practices of teaching, scholarship and research. Therefore, we determined that Feather’s (Citation2010) academic identities benchmark types () might provide a useful typology to analyze what staff in HEiVI institutions say they do and what they value. Feather (Citation2010) generated these benchmark types in order to understand the academic identities of lecturers teaching higher education level programs in non-university further education college settings in England. Similar to our interest in higher education provision in vocational institutions in Australia and the academic identities of the teaching staff, Feather (Citation2010) asked whether or not the college lecturers regarded themselves as academics. These benchmark identities, while broad in scope, nevertheless make a useful reference for examining the academic identities constructed by the educators since the benchmarks encompass a range that reflects differences associated with the vertical stratification of institutions. Furthermore, discussions of academic drift typically explore the extent to which there have been shifts among staff in non-university providers from identities similar to the Facilitator or Practitioner types to the Lecturer or to the Elite Professional types (Griffioen & de Jong, Citation2013). Employing these benchmark ideal types in our analysis permits the operationalization of the academic identities that emerge from the interviewees’ ‘talk’, as they normalize their understandings of ways of seeing doing, being, valuing and believing in their institutions and in the HE expanded system.

Table 1. Benchmarks academic identities (Feather, Citation2010, pp. 198–199)

Methodological framework

Origins and design of the framework

The data analyzed for this paper, the interview transcripts, formed part of the broader data collection for the ARC Project. This project investigated provision in the expanded HE system and questioned whether HEiVI institutions are contributing to vertical stratification or introducing horizontal diversity. The interview guide was constructed in response to these project questions and the shape of the interview was designed to reveal the practices of the institution and the understandings held by staff who lead and teach the higher education programs.

In reviewing the transcripts with educators, our attention was drawn to the ways that the interviewees were aligning themselves with particular relationships, knowledge and pedagogy. We asked what identities were being created, for ‘self’ and ‘others’, and why particular relationships and so on were being valued by the educators? We wondered how these identities and acts of valuing might connect with the educational context. Two research questions were explored: What academic identities are being built for those teaching in HEiVI institutions?’ and ‘How do these identities relate to the context in which higher education in vocational education is being offered?’ Answering these questions also informed the broader research questions of the ARC Project. Feathers’ typology (Feather, Citation2010) was used in the analysis, as a reflexive tool, but did not feature in the construction of the interview guide.

Theorizing identity

The conceptualization of identity and its relationship to representation and discourse are embedded in the methodology and the methods used to examine identity, these form a methodological framework. Through analysis of representation we gain insights into what the speaker sees as acceptable and not acceptable within specific contexts and the roles that they see themselves and others playing within that context (Hall, Citation1997b). This conceptualization of identity responds directly to the research questions and the analysis methods, by offering insights into HEiVI culture in action (ways of being, valuing, seeing, doing and believing). A case study approach allows for an exploration of identity as a social construct and research questions that were designed to generate complex and nuanced data (Merriam, Citation1998; Yin, Citation2003). A discourse analysis approach looks beyond the surface level of what is said to what the speaker/s are attempting to accomplish through discourse. It is concerned with the relationship between language, meaning and context. This interpretation offers insights into lived and imagined, shared and unique, understandings of our perceived realities (Fairclough, Citation2003; Gee, Citation2001, Citation2011b; Kramsch, Citation1998). Our analysis is therefore concerned not only with what the interviewees say but also with how and what they use to construct identities, as acts of validation and normalization.

The case study participants

Eleven educators responsible for teaching and program management of bachelor’s degrees in five Higher Education in Vocational Education (HiVE) institutions were interviewed. The participants were those put forward by their institutions and who agreed to be interviewed. The participants held full-time educator positions, such as head of department or program or unit leader, and therefore what they say maybe the public messages the institutions wish to get across. The interviewees may be interpolated into this discourse or they may resist it and so introduce tensions or contradictions for investigation. Nevertheless, revealing institutional messages about the role of educators in HEiVI and any tensions in the narrative accounts are intrinsically valuable for what these reveal about how academic identities are being shaped to position institutions within the HE system.

The educators brought a range of teaching and industry experience to their current position in a HiVE institution. While some had only worked in TAFE, most had also worked in a university. Only one of the interviewees had a combination of VET, industry and university experience. Not all of the interviewees had VET or industry experience. The interviewees all held a master’s degree and some had PhDs, which were in theoretical and applied study subjects. One of the educators underscored that she was research active. Pseudonyms were used for the educators and their institutions.

The interviews were individual and small group (with 2–3 participants) semi-structured interviews; one follow-up interview was also conducted. The use of group interviews is valuable in eliciting and validating shared, divergent and observable perceptions (Yin, Citation2003). The interview questions elicited information in five areas: the position of degree within the institution; provision of undergraduate teaching; differences to other provision of undergraduate teaching; perspectives on student engagement with the programs; and educational participation information. This guide was designed to reveal the character of provision, such as the qualification and conditions of employment, as well as insights into perceptions about the distinct contributions their work in these institutions made to higher education.

Method

While Membership Categorization Analysis (MCA) is often used as a methodology for conversation analysis, in this case it is used as a discourse analysis tool. It was selected because it is said to focus attention on ‘culture in action’ (Hester & Hester, Citation2012) and align with the theories of identity posited in this paper. MCA focuses attention on what the speaker is attempting to accomplish in situ and how they go about accomplishing it. This is achieved by looking at how speakers group things together and how they see them as belonging together. Categories are understood as belonging together as analysis reveals the rules of application, which includes category-bound activities (i.e. dogs bark) and standardized relational pairings (i.e. student-teacher) (Stokoe, Citation2012). MCA allows analysis of how a speaker constructs, connects and reflects back socio-cultural knowledge and their social and moral understandings. The analysis of moral obligations is particularly valuable because elicits the understandings or ‘rules’ speakers employ to criticize ‘categories’ for not behaving in ways that fulfill the duties and moral obligations that the speaker/writer attributes to the category. For example, in the sentence ‘The teacher should have corrected my work’ we understand that teachers are meant to correct work and that this moral obligation has not been fulfilled. This understanding comes from the student and teachers being a standardized pairing with certain relational obligations.

Thus, MCA analysis of the responses to the interview questions offers up rich and nuanced data about what the interviewees do; why they do it; and how this implicates others. It renders visible what is valued by the educators in their work: the objects that are the focus of their work; their activities; their identities; and the positions the participants adopt in supporting/contesting these acts of valuing.

Analysis

HE in TAFE: distinguishing themes

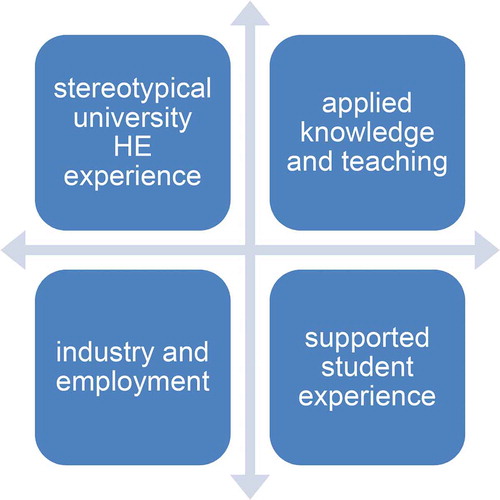

The analysis allowed for a nuanced understanding of the characterization work of the interviewees, as they positioned themselves and others to distinguish and validate their perceptions of valued knowledge, pedagogical practice, relationships and identities. While to some extent the interviews invited the participants to make comparisons with university provision, the interviewees drew on a stereotyped university experience to do this. The interviewees also drew on three other overlapping themes to distinguish their institutions contributions to HE and to construct academic identities see .

The (Stereotypical) University HE experience

The HEiVI study experience was contrasted against an imagined university experience, a stereotypical experience. This is surprising because most of the interviewees had worked in a university. It may be that these stereotypical representations are used as a discursive resource to distinguish HEiVI provision because this is the promotional position of their institutions and/or because the educators did not wish to acknowledge a perceived lack of distinction in provision. Only one of the interviewees (Ivy, Injune) acknowledged she was making generalizations.

We also found references to specific universities that drew on the interviewee’s past work experience and these are used to support claims of HEiVI distinction. For example, Adam (Arlie) and Harvey and Hillary (Hughenden) talk about differences in delivery and student class sizes. A lecture scenario at university is compared unfavorably to teaching a class of 25–30 students in the TAFE. However, there is no acknowledgement of the teaching and learning strategies employed by universities to manage large cohorts. It would seem that the interviewees are indeed constructing a stereotypical idea of a university to contrast with the practices they and their institutions' value in their own work in HE in TAFEs.

We also found that in most accounts the university and its teaching staff, through a perceived focus on research, were represented as out of touch with the real world. They were framed as elite, emotionally distant, inward-looking and unconcerned with student needs and interests. The HEiVI institutions could, however, be heard as aspiring to equal status with universities in discussions of how TAFE degrees are unrecognized or seen as lower status – by parents and school career advisors, unlike in the case of employers. Comparisons were also made in the case of assessment as the interviewees sought to demonstrate that TAFE degrees had equivalent rigor to university degrees. Turning next to the way interviewees discuss students, this ‘othering’ of the idea of a university is sharply revealed.

The supported student experience

The students were positioned as either not being able to ‘cope’ in the big and emotionally distant university environment; as not yet academically ready; or emotionally ready to make the choices that would lead to the outcome of a degree. A supportive learning environment is indicated as enabling HEiVI students to achieve academic success by giving them the time to consolidate their learning and to build on their achievements in incremental stages, so they can work towards a degree. Support is characterized as time; alternative pathways to a degree, with multiple entry and exit qualification points; academic advice; and pastoral care. Support is facilitated by an intimate and nurturing teaching and learning environment, which is based on strong student-teacher relationships and small class sizes.

‘Students that tend to come here are looking for that small environment, that small comfortable nurturing environment where they feel at home.’

Grant (Ganmain)

‘ … you tend to find they’re (classes) smaller and there’s more interaction between the lecturer and the student. Because of that connectedness they should feel more at home. In terms of teaching style, because most of our classes are classroom based rather than lecture and tutorial there’s much less chalk and talk and much more student-centred teaching.’

Gavin (Ganmain)

‘The teachers know exactly who you are. Why haven’t you submitted your assessment? Are you struggling? It’s quite personal in comparison to university.’

Fleur (Fitzroy)

The university is characterized as offering a pedagogical approach that involves distance in the student-teacher relationship; large lecture and ‘chalk and talk’ teaching, invoking understandings of student passivity, anonymity and disengagement. The university teacher is bound to the activity of ‘chalk and talk’, and the university student, as a relational identity, is talked at and not listened to. In contrast, the HEiVI teacher is student and teaching focused, tied to facilitating a nurturing study experience. Interestingly, a number of educators conceded that some of the teaching at their institutions was lecture-based, but they characterized lectures as ‘smaller’ and with high levels of interaction.

The HEiVI student is constructed as needing or desiring high levels of support which only the HEiVI institution can offer. Students are represented as successful based on the provision of support. The level of support for students rather than their academic ability is stressed in examples that speak to how the student has thrived in TAFEs.

‘ … they feel that you know they are just a number and they’re not getting that one-to-one attention … they suddenly become a distinction student because they feel that oh you know they can speak here’

Harvey (Hughenden)

The institution and their teaching staff are constructed as having a moral obligation to provide this experience, supporting students through a focus on teaching and applied knowledge. This obligation to provide support is contrasted against a focus on research and theoretical knowledge. Any shifts away from the student-centered teaching focus positions institutions and their teaching staff as not fulfilling their obligations.

‘ … our teachers are full time teachers and not researchers, their job is teaching. So it’s all about the student. It’s not about the research it’s just about the student.’

Gavin (Ganmain)

Applied knowledge and teaching

Strong markers of difference perceived between staff identities in HEiVI institutions and universities were the characterizations of talk about knowledge and teaching. There was a semantic emphasis on the applied focus and the combination of skills and knowledge linked to the useful and practical outcomes of that knowledge. The interviewees emphasized that their programs, and assessment of their programs, were taught in ways that gave theoretical knowledge a ‘real-world’ application, unlike their perception of what happens at universities.

‘We teach all the theories but then we get them to consider how you would apply those theories to the workplace.’

Gavin (Ganmain)

‘My experience is that universities tend to focus a lot more on the theory than they do combining theory and application or building skills as well. They are more interested in knowledge building … ’

Fleur (Fitzroy)

By ‘knowledge building’ this interviewee would seem to be referencing the idea of research and thereby tying the university to research and a focus on theory, whilst contrasting HEiVI practice as combining theory with application and building skills. Teachers are bound to characterizations of applied teaching and knowledge and yet also construct themselves as being the same as university teachers because they teach theory just as much as university teachers and have the same qualifications. But this attachment to the idea of combining theory and application indicates that they perceive that HEiVI educators bring added value to HE in TAFE work compared to HE in universities. TAFE staff are valued for their skills in teaching (heard through the reference to ‘classroom’ in the extract below) and the industry expertise, knowledge, skills and experience that they bring to teaching.

‘ … our teachers who have their postgrad and all the right qualifications but also have to have industry currency. So that’s what they bring into the classroom.’

Fabianne (Fitzroy)

Teachers are discussed as ‘industry experts’ or ‘practitioners’ and equated to university professors, because they have the same depth of knowledge, but their status is grounded in industry experience, rather than research. They may teach both VET and HE subjects or only HE, depending on whether they have higher degrees, and Grant and Gavin (Ganmain) see advantages for students and for managers in teaching both levels. However, their comments also suggest that the majority of the teachers in their HE programs only teach HE and apart from the program and unit leaders who are full-time, these other teachers are more likely to be sessional staff with PhDs.

Research activities are negatively positioned teacher activities, a distraction from the primary activity of teaching. Fred (Fitzroy) argues that research and teaching should be done by different people. Grant explains that research activities are limited to involvement with projects organized by a specialist unit. Overall, research was framed as an imposition and as a distraction from the real business of the institutions – teaching.

‘the focus is purely on teaching, they’re not distracted by the requirement to publish papers on a regular basis or complete a PhD albeit we still want them to engage in research and scholarly activity … but they are employed as teachers and predominantly that’s what they do, they’re here to teach.’

Grant (Ganmain)

So, research in the TAFEs is understood as applied in that it is regarded as being relevant to professional practice, rather than contributing to pure knowledge building. Additionally, the projects referred to are collaborations with businesses, which have impacts that flow back into the institution directly by benefitting the curriculum, or by strengthening business networks and student placements opportunities. Autonomous research is done ‘off your own back’. Grant also ties teachers to scholarly activity and professional development such as conference attendance, membership of professional bodies and connections with industry.

However, another perspective is introduced by Fred and Fleur (Fitzroy) who suggest that the programs they offer do not require their institutions and teachers to be engaged with ‘pure research’ and so teachers do not need to be researchers. While Fleur says that future jobs may involve research, pure research, is within the university domain and tied to degrees that require it i.e. medicine. Research is discussed positively as a student activity and there are a number of references to student engagement in research and how this research has an industry impact and supports student employability.

In this section, our analysis has shown that teachers are bound to teaching and the teaching of applied knowledge and theory. Overall, research does not yield professional value, unless it flows back into the institution by contributing in some way to industry or teaching and learning activities at the center. Teachers’ are valued for their industry experience, connections and membership of professional bodies.

Industry and employability

Alongside this perception of the value of being a dual professional (a teacher and an industry expert), the interviewees characterized the university as not being able to deliver graduate employability, because universities focus on teaching theoretical knowledge and not application. Thus, the university is characterized as not meeting its obligations to students in not producing graduates who are work-ready. Hillary gives an anecdotal example of the employability, and superiority, of her institution’s graduates compared to university graduates.

‘ … what they were given for the interview was a broken network and the task was to fix it. So most of the university graduates were trying to remember the theory and how that applied to the practical case that was in front of them and in the meantime the (Hughenden) graduate just fixed it. And got the job.’

Hillary (Hughenden)

The message is that HEiVI students and the HEiVI institution offer employers real-world knowledge and skills and student employability. This message can also be heard in comments by Fleur (Fitzroy) about employers choosing TAFE rather than university graduates and in discussions of the rates of graduate employment. For example, Ivy (Injune) and Fabianne and Faye (Fitzroy) highlight that a high percentage of their students get jobs within their field of study, and some before they graduate. HEiVI students are claimed to be in demand. However, while there is discussion of the recognition of degrees by industry/employers, it is also acknowledged that the existence of HEiVI is not widely known, and that TAFEs are seen as having lower status than universities by parents and secondary schools. Thus, the value of TAFE degrees is not broadly recognized. This focus on employability as a distinguishing feature of HEiVI may suggest that the institutions also see themselves as having a moral obligation to industry/employers and, perhaps society (the economy) to produce work-ready graduates.

‘We produce employable graduates … they can be immediately employed and immediately useful to an employer. A number of more theoretically placed – well focused degrees require the employer to put their graduates through a training program to accustom them to what particular skills they actually need at that time so we would – I’d say we produce graduates who are contributing to the economy quicker than some universities might do.’

Hillary (Hughenden)

The interviewees all stressed the importance of their programs meeting the accreditation and qualifications requirements of professional bodies’ skills and knowledge-based requirements, as well as those for higher education quality assurance, the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) requirements. Moreover, the importance of strong industry relationships; of industry and professional bodies input, and in developing relevant student work-based skills was broadly stressed. The role of industry input was in keeping the curriculum relevant and in facilitating relevant student placements and internships, which allowed students to make ‘real’ contributions to the industry and gain relevant experience that gave them an advantage in securing employment.

‘We’ve got fantastic relationships with them. They sit on our course advisory committee’

Faye (Fitzroy)

‘ … we have really strong links with our industry partners. You’ll actually gain industry relevant skills that will give you a better chance of a job … ’

Ivy (Injune)

Many of the interviewees discussed how their programs were developed to respond to industry requirements and with industry/professional body input. Ivy, for example, talks about how her institution (Injune) was approached to develop a qualification. Although, she also suggests that in some cases of there may be credential inflation because they may be developing degree courses in response to direct requests from industry partners where a vocational qualification would suffice. Ivy cites students leaving at the end of the second year to get jobs or start a business to support her claim that an HE qualification was unnecessary.

Academic identities in HEiVIs

In what follows we now turn to comparing what was being said by the educators with Feather’s (Citation2010) categorizing benchmarks of ideal types of HE educator identities () in order to discuss what identities the educators’ valued. The analysis of the categorization work of the interviewees shows that there is a strong focus on teaching, applied learning and applied knowledge. Research activities are only valued when they support teaching and learning activities or contribute to employability, in ways that leverage or strengthen industry relationships. Research activities are only endorsed when strategically aligned with the interests of the institution. Research, as an autonomous activity is not a valued activity and it is perceived as unnecessary and distracting from the real work of the teacher, teaching. Moreover, representations of elitism attached to research activities are used to validate and normalize a teaching-only culture. We also found a strong emphasis on student support, which is not captured in Feather’s benchmark identities, and expectations of a more ‘teacherly’ approach to student-teacher relationships that connects with high levels of pastoral care.

Discussion

Educators working in Australian HEiVI institutions distinguish HEiVI contributions to higher education in ways that focus on perceived institutional strengths. These strengths were predominantly positioned against perceptions of deficiencies in stereotypical representations of a university. These distinctive features of HEiVI institutions are similar to those presented in other Australian reports (Callan & Bowman, Citation2015; Wheelahan et al., Citation2012, Citation2009) and a recent English study (Henderson, Citation2018). These points of distinction highlight the importance of forms of knowledge embedded in practice; teacher-student relationships; specific occupational outcomes for students; support for student learning; and prioritizing of pedagogy over pure research. These valued forms of knowledge and pedagogical practices are understood as being part of a vocational culture and indicate the unique contribution to HE that HEiVIs provide. Yet, in aligning with the institutional vocational culture, these educators also distinguished themselves from other teachers in the TAFEs who taught at lower levels on non HE programs within the competency-based frameworks as Wheelahan and colleagues found in Ontario, Canada (Wheelahan et al., Citation2017).

Furthermore, the construction of students as needing support to achieve their outcomes may be conflated in ways that represent students as vulnerable (Avis & Bathmaker, Citation2004; Ecclestone, Citation2004; Ecclestone & Hayes, Citation2008) and as deficit learners (Archer, Citation2007). Compounding this is the perceived lower status of TAFEs (Wheelahan et al., Citation2009) and perceptions that these institutions traditionally attract students from disadvantaged background students. The educators interviewed may also be aware of the implications of positioning students as deficit learners because of the ways that they counter these perceptions by emphasizing student academic capability and the positioning of universities as failing the student. There is a sense that the educators are in an ambivalent position, on the one hand stressing the distinctive role they provide in supporting students by offering a different form of higher education, yet on the other hand, recognizing that promoting their differentness may undermine their claims to parity of esteem with university higher education just as Moodie et al. (Citation2018) found in Canada. TAFE educators resolve this ambivalence by suggesting that it is the universities that are in deficit and not the student.

Our study also suggests that the participants sought to legitimize teaching as the priority of the HE educators working in their institutions. They constructed ‘good’ teachers as having this focus and as having a moral obligation to support students. The good teacher has expert status; industry connection; a student-centered approach; and establishes a comfortable and nurturing learning environment. This is distinct from a learning-centered approach where support is located within addressing the educational needs of the student and the student is not positioned as vulnerable deficit learner, or, as suggested by research on commercialization, a consumer (Molesworth et al., Citation2009; Williams, Citation2013). Similarly, if educators are perceived to be focusing on research, which is not sanctioned as serving the interests of students or industry and the teaching needs of the institution, this focus on research positions teachers as ‘bad’ teachers. Scholarly activities on the other hand are valued because they are clearly linked to knowledge development for the purposes of teaching. Although, Australian reports on TAFE suggest that what constitutes scholarly activities is not clear and that a strong definition is needed (Callan & Bowman, Citation2015; Wheelahan et al., Citation2012, Citation2009). So, returning to Feather’s (Citation2010) categories (), we can see that in the teaching-focused Australian context of HEiVI, academic identity is constructed as drawing on pedagogical and knowledge concerns. This construction is conceptualized as the benchmark ‘Practitioner’ identity. However, the focus on industry also connects this construction of academic identity with ‘The Facilitator’ benchmark identity and this latter identity is perhaps more closely associated with educators in VET. Moreover, in framing research activities as elite, Feather’s (Citation2010) ‘Professional Research Elite’ and ‘The University Lecturer’ identities are not distinguished. None, however, of the benchmark identities put forward by Feather (Citation2010) captures expectations of the high levels of support for students expected of HEiVI educators. This notion of ‘caring’ is perhaps one that is more expected of secondary education educators who have a clear duty of care.

In terms of what was found with regards to teaching conditions, as in other college-based higher education contexts (Springbett, Citation2018) and previous Australian research (Callan & Bowman, Citation2015; Wheelahan et al., Citation2009), teachers may teach both VET/FE and HE subjects or only teach in one area, but our study of HEiVI indicates that increasingly HE specialist educators are emerging. There would seem to be a preference only in a minority of institutions for teachers to teach across both levels, rather than specialize in higher education level programs. The cognitive shift required in teaching across both VET and HE levels may mean this is not ideal for teachers (Feather, Citation2010), but it serves management needs in terms of assigning teaching loads (Sarawat, Citation2015). Whether or not a continuity of teachers from further education to higher education levels supports student learning is unclear (Sarawat, Citation2015). Moreover, there is a suggestion in the interviews that some institutions may currently be relying on a pool of casual staff who may teach higher education programs in TAFEs and universities. A reliance on highly qualified casual staff who teach across the expanded sector leads us to reflect on how their academic identities might be shaped and about how they might shape higher education.

Our research also suggests that, despite claims to student-centeredness, HEiVI institutions may support the needs of industry/professional bodies/employers and the economy over those of students and the social equity objectives of widening participation. This can be seen in the unequal relationship with industry. For, in creating degree courses that industries ask them to develop where they anticipate a vocational qualification would be sufficient, HEiVI institutions may be prioritizing their commercial objectives over their educational ones, and maybe contributing to qualification creep.

Conclusion

Our research reveals how college-based higher education educators relationally position students and teachers within a matrix of distinction () that represents students as vulnerable and deficit learners, and teachers as obligated to provide care, support and student-centered teaching. Arguably this matrix of distinction may be undermining their social justice mission and inadvertently contributing to vertical stratification of the system by not facilitating students to become self-guided autonomous lifelong learners and future professional leaders. Teachers interested in autonomous research are represented as ‘bad’ teachers because they put their needs for employment satisfaction above those of vulnerable students (Brooks, Citation2018). Teaching activities are prioritized over pure research activities and only scholarly activities and research that supports teaching are valued because of this.

It would seem then that HEiVI teachers do not present identities congruent with the category of the Lecturer as defined by Feather (Citation2010). The educators interviewed demonstrated awareness of debates on the importance of research in knowledge building, in informing curriculum and teaching, but they saw research as a university activity. This raises the question of how teachers in HEiVI are expected to develop the skills and depth of knowledge required to teach HE programs (Feather, Citation2016) and to guide student research activities. Rather than investing in their teachers’ as researchers, the interviewees description of their workforce suggests these institutions are drawing on casual ‘work-ready’ PhD staff.

For those academics seeking to secure ongoing positions and to develop their careers as teacher-researchers through working in HEiVI institutions, the future is not promising. Australian HEiVI institutions, in distinguishing the higher education work and expectations of educators from the imagined stereotyped views of practices in universities appear to be narrowing the scope of academic work. Perhaps the justification for these practices is to counter staff academic drift and threats to their institutional objectives of being distinctive HE providers for their local communities and industries, but these practices may also be limiting imagining of academic identity for those engaged in higher education in TAFEs.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Australian Research Council in the 2017 Discovery Project funding round (DP170101885). The authors acknowledge the support of other research team members in the data generation for this article: These include Chief Investigators: Dr Steven Hodge, Griffith University; Dr Shaun Rawolle, Deakin University; Partner Investigators: Professor Ann-Marie Bathmaker, University of Birmingham, UK; Professor Trevor Gale, University of Glasgow, UK; and Research Fellow, Dr Elizabeth Knight, Victoria University. The Project Team including the authors also thank the participants in the research who were so generous with their time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alice Sinclair

Alice Sinclair, PhD, is an early career researcher. She is currently in an academic learning and teaching development position at the University of Melbourne. Prior to this, Alice worked as a Research Fellow on an ongoing ARC Discovery Project, based in the Faculty of Education, Monash University. Before completing her PhD in Education at Monash University, Alice was an educator and senior manager in the TESOL sector. Her research and teaching interests are in the areas of discourse analysis methods (including document analysis); ‘Discourse’; the politics of representation and identity; and the pedagogy and ideology of TESOL.

Sue Webb

Sue Webb is a Professor of Education at Monash University, Australia (and since June 2020, Professor (Research) Adjunct). Before moving to Australia in late 2010, she was Professor of Continuing Education at the University of Sheffield, UK. She has researched the policy effects and practices related to access and participation of students from under-represented groups in the field of further and higher education, including the experiences of migrants and refugees in the UK and in Australia. Recently she led a project funded by the Australian Research Council Discovery Project DP170101885 2017-2020 entitled - Vocational institutions, undergraduate degrees: distinction or inequality? She is also Co-Editor of theInternational Journal of Lifelong Education.

Notes

1. The larger project, the Australian Research Council DP170101885 Vocational Institutions, Undergraduate Degrees: Distinction or Inequalities ran from 2017–2020. The closing report is available on www.monash.edu/hive

References

- Archer, L. (2007). Diversity, equality and higher education: A critical reflection on the ab/uses of equity discourse within widening participation. Teaching in Higher Education, 12(5–6), 635–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510701595325

- Archer, L. (2008). Younger academics’ constructions of ‘authenticity’, ‘success’ and professional identity. Studies in Higher Education, 33(4), 385–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802211729

- Avis, J., & Bathmaker, A. M. (2005). Becoming a lecturer in further education in England: The construction of professional identity and the role of communities of practice. Journal of Education for Teaching, 31(1), 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607470500043771

- Avis, J., & Bathmaker, A.-M. (2004). The Politics of Care: Emotional labour and trainee further education lecturers. Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 56(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820400200243

- Avis, J., & Orr, K. (2016). HE in FE: Vocationalism, class and social justice. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 21(1–2), 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2015.1125666

- Bathmaker, A.-M. (2016). Higher education in further education: The challenges of providing a distinctive contribution that contributes to widening participation. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 21(1–2), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2015.1125667

- Bathmaker, A.-M. (2017). Post-secondary education and training, new vocational and hybrid pathways and questions of equity, inequality and social mobility: Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 69(1), 126–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2017.1304680

- Brooks, R. (2018). The construction of higher education students in English policy documents. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 39(6), 745–761. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2017.1406339

- Callan, V., & Bowman, K. (2015). Lessons from VET providers delivering degrees. Retrieved from Adelaide: http://www.ncver.edu.au/publications/2791.html

- Clegg, S. (2008). Academic identities under threat? British Educational Research Journal, 34(3), 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920701532269

- Ecclestone, K. (2004). Learning or Therapy? The Demoralisation of Education. British Journal of Educational Studies, 52(2), 112–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8527.2004.00258.x

- Ecclestone, K., & Brunila, K. (2015). Governing emotionally vulnerable subjects and ‘therapisation’ of social justice. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 23(4), 485–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2015.1015152

- Ecclestone, K., & Hayes, D. (2008). The Dangerous Rise of Therapeutic Education. Routledge.

- Ecclestone, K., & Rawdin, C. (2016). Reinforcing the ‘diminished’ subject? The implications of the ‘vulnerability zeitgeist’ for well-being in educational settings. Cambridge Journal of Education, 46(3), 377–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2015.1120707

- Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing Discourses: Textual Analysis for Social Research. Routledge.

- Feather, D. (2010). A whisper of academic identity: An HE in FE perspective. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 15(2), 189–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596741003790740

- Feather, D. (2016). Defining academic - real or imagined. Studies in Higher Education, 41(1), 110–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.914921

- Fisher, S. (2006). Does the ‘Celtic Tiger’ society need to debate the role of higher education and the public good? International Journal of Lifelong Education, 25(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370500510827

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363

- Gale, T., & Tranter, D. (2011). Social justice in Australian higher education policy: An historical and conceptual account of student participation. Critical Studies in Education, 52(1), 29–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2011.536511

- Gee, J. P. (2001). Identity as an Analytic Lens for Research in Education. Review of Research in Education, 25, 99–125. https://doi.org/10.2307/1167322

- Gee, J. P. (2011a). How to do discourse analysis: A toolkit. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Gee, J. P. (2011b). An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Gellert, C. (1993). Academic drift and blurring of boundaries in systems of higher education. Higher Education in Europe, 18(2), 78–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/0379772930180206

- Griffioen, D., & de Jong, U. (2013). Academic Drift in Dutch Non-University Higher Education Evaluated: A Staff Perspective. Higher Education Policy, 26(2), 173–191. https://doi.org/10.1057/hep.2012.24

- Hall, S. (1985). Signification, Representation, Ideology: Althusser and the Post-Structuralist Debates. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 2(2), 91–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295038509360070

- Hall, S. (1997a). The Specticle of the ‘Other’. In S. Hall (Ed.), Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices (pp. 225–290). Sage in association with The Open University.

- Hall, S. (1997b). The Work of Representation. In S. Hall, J. Evans, and S. Nixon (Eds.), Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices (pp. 15–74). Sage in association with The Open University.

- Harris, S. (2005). Rethinking academic identities in neo-liberal times. Teaching in Higher Education, 10(4), 421–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510500238986

- Henderson, H. (2018). ‘Supportive’, ‘real’, and ‘low-cost’: Implicit comparisons and universal assumptions in the construction of the prospective college-based HE student. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 42(8), 1105–1117. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2017.1349885

- Hester, S., & Hester, S. (2012). Categorial Occasionality and Transformation: Analyzing Culture in Action. Human Studies, 35(4), 563–581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-012-9211-7

- Kramsch, C. (1998). Language and culture. In H. G. Widdowson (Ed.), Oxford Introductions to Language Study (pp. 3–14). Oxford University Press.

- Kyvik, S. (2007). Academic drift—A reinterpretation. In The Officers and Crew of HMS Network (Ed.), Towards a Cartography of Higher Education Policy Change (pp. 333–338). Enschede: A Festschrift in Honour of Guy Neave, CHEPS.

- Lea, J., & Simmons, J. (2012). Higher education in further education: Capturing and promoting HEness. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 17(2), 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2012.673888

- Marginson, S. (2011). Higher Education and Public Good. Higher Education Quarterly, 65(4), 411–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2011.00496.x

- Marginson, S. (2016). High Participation Systems of Higher Education. The Journal of Higher Education, 87(2), 243–271. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2016.0007

- Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. Jossey-Bass.

- Molesworth, M., Nixon, E., & Scullion, R. (2009). Having, being and higher education: The marketisation of the university and the transformation of the student into consumer. Teaching in Higher Education, 14(3), 277–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510902898841

- Moodie, G., Skolnik, M. L., Wheelahan, L., Liu, Q., Simpson, D., & Adam, E. G. (2018). How are ‘applied degrees’ applied in Ontario colleges of applied arts and technology? In J. Gallacher & F. Reeve (Eds.), New Frontiers for College Education. International perspectives (pp. 137–147). Routledge Taylor and Francis.

- Naidoo, R., & Williams, J. (2014). The neoliberal regime in English higher education: Charters, consumers and the erosion of the public good. Critical Studies in Education, 56(2), 208–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2014.939098

- Neave, G. (1978). Polytechnics: A policy drift? Studies in Higher Education, 3(1), 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075077812331376396

- Neave, G. (1979). Academic drift: Some views from Europe. Studies in Higher Education, 4(2), 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075077912331376927

- Orr, K., & Simmons, R. (2010). Dual identities: The in‐service teacher trainee experience in the English further education sector. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 62(1), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820903452650

- Parry, G. (2009). Higher Education, Further Education and the English Experiment. Higher Education Quarterly, 63(4), 322–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2009.00443.x

- Parry, G., Callender, C., Scott, P., & Temple, P. (2012). Understanding higher education in further education colleges. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/32425/12-905-understanding-higher-education-in-further-education-colleges.pdf

- Sarawat, A. (2015). Managing organisational culture and identity in a dual sector college. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 5(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-08-2014-0039

- Sellar, S., Gale, T., & Parker, S. (2011). Appreciating aspirations in Australian higher education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 41(1), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2010.549457

- Snowden, C., & Lewis, S. (2015). Mixed messages: Public communication about higher education and non-traditional students in Australia. Higher Education, 70(3), 585–599. https://doi.org/doi:10.1007/s10734-014-9858-2

- Springbett, O. (2018). The professional identities of teacher educators in three further education colleges: An entanglement of discourse and practice. Journal of Education for Teaching, 44(2), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2017.1370481

- Stanton, G. (2009). A View from Within the English Further Education Sector on the Provision of Higher Education: Issues of Verticality and Agency. Higher Education Quarterly, 63(4), 419–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2009.00441.x

- Stokoe, E. (2012). Moving forward with membership categorization analysis: Methods for systematic analysis. Discourse Studies, 14(3), 277–303. https://doi.org/doi:10.1177/1461445612441534

- Teichler, U. (2008). Diversification? Trends and explanations of the shape and size of higher education. Higher Education, 56(3), 349–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-008-9122-8

- Tight, M. (2015). Theory development and application in higher education research: The case of academic drift. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 47(1), 84–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2015.974143

- Webb, S., Bathmaker, A.-M., Gale, T., Hodge, S., Parker, S., & Rawolle, S. (2017). Higher vocational education and social mobility: Educational participation in Australia and England. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 69(1), 147–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2016.1269359

- Webb, S., Rawolle, S., Hodge, S., Gale, T., Bathmaker, A.-M., Knight, E., & Parker, S. (2019). Degrees of Difference, Examining the Scope, Provision and Equity Effects of Degrees in Vocational Institutions, Interim Project Report. https://protect-au.mimecast.com/s/NAltCANZ0ohNNZYzVI80a83?domain=sites.google.com

- Wheelahan, L., Arkoudis, S., Moodie, G., Fredman, N., & Bexley, E. (2012). Shaken not stirred? The development of one tertiary system in Australia. http://www.ncver.edu.au/publications/2450.html

- Wheelahan, L., Moodie, G., Billet, S., & Kelly, A. (2009). Higher Education in TAFE. http://www.ncver.edu.au/publications/2167.html

- Wheelahan, L., Moodie, G., Skolnik, M. L., Liu, Q., Adam, E. G., & Simpson, D. (2017). CAAT baccalaureates: What has been their impact on students and colleges? Centre for the Study of Canadian and International higher education, OISE-University of Toronto. https://www.academic.edu/34112325/CAAT_baccalaureates_What_has_been_their_impact_on_students_and_colleges

- Williams, J. (2013). Consuming Higher Education: Why Learning Can’t be Bought. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Yin, R. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods. Sage Publications.