ABSTRACT

Digital technology has been found useful in bridging the gap between school and work placements. In earlier studies we have interviewed vocational teachers with creative ideas on addressing this issue, but they encountered obstacles and could not always proceed as they wanted. The aim of this study is to provide a deeper understanding of the obstacles encountered by Swedish vocational teachers when using digital technology to bridge the gap between school and work placements. The study is based on a theoretical understanding of teacher agency, and also presents a hierarchical model developed from our research. Ten in-depth interviews were conducted with five purposively selected vocational teachers. The teachers provided detailed examples of a range of problems stemming from structural, cultural and material aspects, and how these problems forced them to take steps backwards when trying to develop their teaching practices.

Introduction

The digitalisation of schools has been promoted in many countries in different ways for some decades (e.g. DEAG – Digital Education Advisory Group, Citation2015; EU – European Union, Citation2020; ED – United States Department of Education, Citation2016). In 2017, the Swedish Ministry of Education and Research (Citation2017) launched a digital strategy for schools, and curricula were changed accordingly. A follow-up study from the Swedish National Agency for Education (SNAE, Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2019) concluded that although schools have the needed infrastructure, technology is not used to the desired extent. Similar results have also been reported in several studies done in other countries (cf. Enochsson & Rizza, Citation2009; Gill et al., Citation2015; Tondeur et al., Citation2016). While teachers were positive towards digital tools in classrooms, the report revealed that they felt a need for more training before feeling comfortable using them (SNAE, Citation2019). Recent qualitative studies of teachers working with young students (Enochsson & Ribaeus, Citation2020; Lindeman et al., Citation2021), have found that the reasons for not using digital tools are more multifaceted than shown by big surveys, and the low level of use can be related to a range of practical matters, teachers’ own values, parents’ opinions as well as local policies, alongside a lack of training.

Vocational teachers’ digital competence and mission is twofold. First, they need to keep up with sometimes quite advanced digital technology used in their vocational field (e.g. Cattaneo & Barabasch, Citation2017; Kilbrink et al., Citation2021). Second, in their role as teachers, they also need to stay abreast of various kinds of commonly used digital technology, such as communication platforms, word processing software, etc. Vocational education is usually organised around different learning arenas, and a gap between the school and the vocational workplaces has often been noted (e.g. Aarkrog, Citation2005; Akkerman & Bakker, Citation2012; Schaap et al., Citation2012; Tanggaard, Citation2007). Unlike other teachers, vocational teachers working in dual secondary school programmes, also have a mission to support students to bridge this gap, i.e. to facilitate boundary crossing (cf. Akkerman & Bakker, Citation2011). Research has discussed various ways of achieving this (cf. Illeris, Citation2009; Sappa et al., Citation2016; Tynjälä, Citation2009). Digital technology has been found to be useful boundary objects, which in this context refers to tools that facilitate bridging the gap between two learning arenas more smoothly (Akkerman & Bakker, Citation2011, Citation2012; Berner, Citation2010; Cattaneo & Aprea, Citation2018; Cattaneo & Barabasch, Citation2017; Kilbrink et al., Citation2021).

In our own research, we have met vocational teachers considered to be enthusiastic ‘early adopters’ of digital technology as boundary objects between school and workplaces, and a lack of competence in using digital technology has not been an issue (Enochsson et al., Citation2020; Kilbrink et al., Citation2020) Such teachers provided examples of many creative solutions for using technology as boundary objects. The teachers did not identify only a single gap, but multiple gaps that can be bridged using different kinds of technology. They further indicated that putting their ideas into practice was not always easy. We realised that the picture is more complex than just a need for more training or changing attitudes (cf. Enochsson & Rizza, Citation2009; Gill et al., Citation2015; SNAE, Citation2019; Tondeur et al., Citation2016). We also discovered a lack of research on the obstacles teachers may encounter in their attempts to bridge gaps between school and workplaces using digital technology, which may lead to a risk of not addressing the appropriate issues. Therefore, this topic warrants further studies. In Swedish vocational training in secondary school, students alternate between school courses and placements at workplaces, which is also the case in several other countries. In this context, we studied the specific challenges vocational teachers face when trying to help students to connect what they learn in school with what they learn at their work placements.

The aim of this study is to provide a deeper understanding of the obstacles vocational teachers encounter when trying to use digital technology to bridge different gaps between school and workplaces. Digital technology or tools are here used interchangeably to refer to the hardware and/or software used by vocational teachers to bridge this divide. Examples of digital technology and tools used in this context are laptops, mobile phones, clouds for sharing information, learning platforms, social media, interactive apps, blogs as well as apps connected to different vocational branches.

Teachers’ use of digital technology

This section presents research focused on explanations as to why vocational teachers use, or do not use, digital technology to support the students in connecting school and workplaces. Few relevant studies have been retrieved from several academic databases. The most important ones, already mentioned in the introduction, tend to focus on how this can be done (Akkerman & Bakker, Citation2011, Citation2012; Berner, Citation2010; Cattaneo & Aprea, Citation2018; Cattaneo & Barabasch, Citation2017; Schwendimann et al., Citation2015). We therefore first provide a short background on why teachers generally use technology, and in a later section, we present our own research that led to the present study.

Teachers as a group – including student teachers – have been found to use digital technology less than average citizens (CMA, Citation2009; Knowledge Foundation, Citation2006; Nordicom, Citation2008; Salaway et al., Citation2008). As time passed, these studies were claimed to have become irrelevant; teachers and student teachers are said to have caught up at group level. A longitudinal study conducted at a Swedish teacher training programme showed that recently admitted student teachers increased their competence over time, but more slowly than the average citizen of the same age group, aged 20–25 (Buskqvist & Enochsson, Citation2012; Enochsson, Citation2017). While private use does not result in using technology for teaching (Krumsvik, Citation2011), general digital competence lays the foundation for skilfully using digital tools in teaching (cf. Lucas et al., Citation2021).

A teacher’s ICT self-efficacy is an important factor in using digital media in the classroom (Gudmundsdottir & Hatlevik, Citation2018). According to Gudmundsdottir and Hatlevik, teachers’ beliefs constitute one element, and they found that the perceived usefulness of digital tools did not correspond to ICT self-efficacy in teaching, while perceived distraction corresponded negatively to ICT self-efficacy in teaching. On the other hand, the teachers answering the researchers’ questionnaire felt underprepared for the use of digital tools by their initial teacher education. One interpretation is that there is room for improvement, but this also highlights how vital it is for teacher educators to serve as positive role models. Specific training has also been found crucial in using digital tools, according to a study taking a domestication theoretical perspective on teachers’ work (Lindeman et al., Citation2021).

In a quantitative study of more than a thousand Portuguese teachers, Lucas et al. (Citation2021) found that in addition to personal factors, contextual factors, such as students’ access to technology, also affect pedagogical uses; the teacher’s personal engagement had to be facilitated by the school. Nevertheless, Lucas et al. claimed that personal factors are stronger predictors of the pedagogical use of digital tools than contextual factors. Other studies have shown that teachers felt that the digital technology brought into schools does not always suit their needs (e.g. Haydn & Barton, Citation2007). This has led to a certain scepticism and restraint regarding the use of digital technology in schools, and reflecting on what technology actually adds can be a sound approach (e.g. Selwyn, Citation2016). A study from the Swedish Teachers’ Union (Lärarförbundet, Citation2020) shows that teachers are not always allowed to control technology, which therefore may pose a work environment problem.

Teachers generally also use digital tools for administrative purposes or to facilitate work (e.g. Enochsson & Rizza, Citation2009; Lindeman et al., Citation2021), and there can be different levels of pedagogical use. When assessing student teachers’ classroom practices, Angeli and Valanides (Citation2009) used a model to distinguish between activities that were only possible because of the technology used, and choosing technology in the light of the specific topic. In our own research focused on vocational teachers, we made similar distinctions in their uses of digital technology with the aim to bridge the gaps they had identified between school and workplaces. From our data, we developed a model where the teachers’ uses of technology were ordered hierarchically depending on their pedagogical aims (Enochsson et al., Citation2020; Kilbrink et al., Citation2020). To provide background to the present study, this model is described in the following section.

Hierarchical model of the use of boundary objects in vocational education

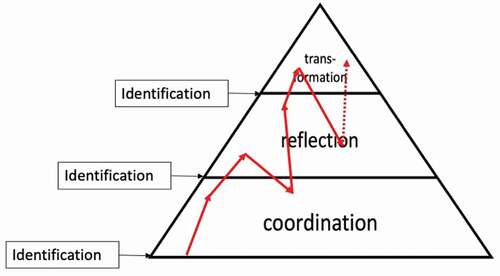

Our hierarchical model (Enochsson et al., Citation2020; Kilbrink et al., Citation2020) uses the concepts coordination, reflection and transformation, borrowed from Akkerman and Bakker (Citation2011). These concepts represent three levels to which all gaps identified by the teachers relate. According to this model, teachers’ pedagogical aims are qualitatively different at the different levels. At the lowest level, coordination, teachers aim to keep in touch when there is not enough time to visit all students, or to ensure that students meet the course outcomes. For this purpose, teachers for example, use phone calls, text messages, emails and online document sharing. At the next level, reflection, the teachers’ pedagogical aims are to let students develop their thoughts. The teachers want to create better learning conditions by connecting coursework to practice. Interactive technology, such as chat tools or discussion forums, are appropriate here because teachers can quickly provide feedback. At the most advanced level, transformation, the teachers aim to ensure holistic education and seamless moving between learning arenas. Teachers continually identify new gaps that need to be bridged, and this ongoing identification process forms part of their development as teachers (see ).

Figure 1. The hierarchical model (Enochsson et al., Citation2020)

Some teachers in our studies (Enochsson et al., Citation2020; Kilbrink et al., Citation2020) wanted to develop their teaching further by aiming at a higher level in the hierarchy, but they did not always achieve their aims. The red line in shows a hypothetical teacher moving through the hierarchy and thus developing their teaching practice through the use of digital tools. When encountering obstacles, the teacher stepped ‘back’ or ‘down’. When falling back to a lower level, they did it with new experience; they reconsidered their plans, and the movement continued. When teachers move up in the hierarchy and use digital tools for reflection or transformation, they still use them at the lower levels too, for example, for communication and administration.

In our previous studies, we noted that teachers could take steps backwards because of obstacles related to technology, but we did not analyse these further (Enochsson et al., Citation2020; Kilbrink et al., Citation2020). However, the aim of this study is to provide deeper knowledge on the obstacles encountered by vocational teachers in relation to their use of digital technology to bridge different gaps between school and workplaces. This aim is explored in the light of the following research question:

What obstacles beyond the teachers’ control do they, themselves, see as hindrances to reaching their aim?

Hence, this study focuses on the obstacles teachers face when using digital technology to bridge the gaps between school and workplaces in vocational education.

Theoretical framework

The present study is based on a theoretical understanding of teacher agency drawing on the ecological approach advocated by Priestley et al. (Citation2015). According to this view, past experiences, including those from teacher education, are important for how teacher agency is enabled in the present. At the same time, the present is important for the enablement of a vision of future action in a teaching situation. Priestly, Biesta and Robinson suggest a chordal triad with three dimensions of agency: the iterational (past, habit), the projective (future, imagination) and the practical-evaluative (present, judgment). This view builds on Emirbayer and Mische (Citation1998), who discussed agency in general rather than teacher agency specifically.

According to an ecological approach, teacher agency is achieved through the interplay between the context and the capacity of the individual, which means that the individual cannot always act according to personal ideas and visions (Priestley et al., Citation2015), and that ‘Teacher agency is not a capacity of individuals’ (p. 3). Priestley et al. (Citation2015) highlight three aspects on achieving teacher agency: culture, structures and available material. The cultural aspect, here, represents people’s beliefs, but also their ways of thinking and speaking of values. The structural aspect pertains to social structures and relational resources, while the material aspect involves the physical environment (see , Biesta et al., Citation2015). These aspects allow us not only to analyse what affects teachers’ development efforts, but also the reasons they sometimes fail to reach their pedagogical aims.

Figure 3. A model for understanding the achievement of agency (Biesta et al., Citation2015, p. 627)

In the teacher agency theory used here, the iterational dimension (teacher training and past life experiences) affects how teachers express their visions in the short and long term, i.e. the projective dimension. The visions in (the projective dimension) are then expressed through the aims – or visions of teaching – corresponding to the different levels of the hierarchical model (). It is important to remember that Priestley et al.’s (Citation2015) understanding of teacher agency also includes a temporal aspect, which means that the dimensions are not static; today’s present will be tomorrow’s past.

Materials and methods

Our interest lies in how teachers tell about the obstacles they encounter. Therefore, the empirical data consist of narrative in-depth interviews (Clandinin & Connelly, Citation2000; Kilbrink, Citation2013; Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2009; Polkinghorne, Citation1995). We chose to interview the informants twice, partly to understand how their ideas had developed, but also because the telling of their stories is seen as a process of creating meaning from their actions (cf. Freeman, Citation2010). The two interviews took place in two consecutive school years. The interviewees were encouraged to provide examples from their work and were given time to express themselves freely. In the first interview, the teachers gave examples of what they were doing and how. They all described ideas they wanted to put into practice, and the main reason for the second interview was to allow them to tell about how their teaching development and how their ideas had worked out. Although this was not the original aim of the interviews, we obtained rich material on the obstacles they encountered, which constitutes the data in this study.

Participants

Five teachers were purposively selected for the interviews (cf. Cohen et al., Citation2000; Yin, Citation2014) because they used digital technology to bridge the gap between school and workplaces, and their attitudes to and/or beliefs on the use of technology were positive. They represented different vocational programmes with different ways of organising student work placements (see ). The teachers were recruited from the authors’ networks, but for ethical reasons we avoided interviewing a person we knew personally, as far as possible. Each teacher was interviewed twice, and the average duration of one interview is just under an hour [in total 9h41m41s]. The interviews took place either at their schools or at the university, depending on the interviewee’s preference.

Table 1. Informants

Analyses

We used the model of teacher agency developed by Priestley et al. (Citation2015) in our analysis, focusing on how the three aspects of the practical-evaluative dimension in this model affect the achievement of the interviewees’ teacher agency. These three aspects – culture, structures and available material – are described above. Using the teachers’ narratives, we analysed the factors they described as necessitating backward steps and presenting hindrances to achieving their aims. The transcribed narratives were read several times, and excerpts relating to the different aspects were first identified separately by the authors and then discussed. Typical examples from the narratives were chosen to illustrate the different aspects. The same quotations could sometimes be related to more than one aspect, since they are intertwined. We did not find any obstacles in the analysed interviews which we were unable to relate to one of these aspects. We also noted similarities and differences between the excerpts from the different interviewees and categorised them in relation to the kind of obstacle they pertained to. Excerpts from different teachers are chosen to illustrate the different kinds of obstacles below.

Results

Following Biesta et al.’s model described above, we can see obstacles pertaining to all three aspects of the practical-evaluative dimension. The three aspects are intertwined and sometimes overlap; a lack of or limited infrastructure may be the result of financial considerations. The main purpose is to show examples of obstacles and demonstrate the many layers of this complex process of using technology in bridging the gaps between school and workplaces.

The material aspect

The material aspect generally concerns the effect of material resources and physical environment on teachers’ agency. Many examples given by the interviewees were related to a lack of mobile devices that could be used in various ways when the students were at different workplaces. Alicia said:

They have used their own phones, and that’s not great. There is a cost for the student. It shouldn’t cost the students anything to attend school. So, this is not right. [Alicia, Care and Treatment]

Like Alicia, Lily talked about the problem of finding workable solutions when education must be free of charge. Lily wanted to collaborate with workplace supervisors, but they could not access the school’s virtual learning environment. This may be regarded as a structural problem, but Lily the way she tells about it could rather be related to a material problem, since she argued that it must be solvable and education must have acceptable costs:

We are trying to find something that would work in school and we also have a lot of workplaces [where it is also supposed to work]. I think that’s the big problem. How to solve so many domains. […] there are apps. But often they are quite expensive or just not what you need. [Lily, Handicrafts]

Stephen described compatibility problems he had encountered, which can also be linked to the material aspect. When forced to use incompatible systems, having technology available does not help:

Unfortunately, not all digital tools or teaching media work perfectly at all actually. So, the connection between computer and phone doesn’t always work … And that is supposed to be fixed. [Stephen, Construction and Installation]

The material aspect mainly concerns resources in general, and mobile technology for students in particular. Vocational teachers struggle with not always having access to the hardware or software they need to do their work. This sometimes leads to students using their own mobile phones to keep in touch with the school during the placement periods, which may entail costs.

The structural aspect

In our study, the structural aspect mostly concerns finances – and a lack of time, as a consequence of a lack of money – but also regulations. The lack of time, as a result of shrinking resources, was a recurring factor in the narratives. When teachers discovered that something was not working, it was usually impossible to solve it within a reasonable time frame before the next semester or placement period. Mary felt that everything she needed to learn took more time than she had at her disposal:

I’m pretty bad myself at technology. It takes time for me to learn it. […] and I’m quite useless at it. That’s probably the reason why it doesn’t work. It’s not because I’m negative. […] We have to work on it and that takes time. [Mary, Animals]

Stephen described the same situation, but also wanted the supervisors to be paid, so he could ask to meet them and present his ideas:

One thing is that you have to have the time to be able to learn this. To create a good teaching practice so you feel comfortable doing it. And after that you can go out with a big smile and show off your new skills. [Stephen, Construction and Installation]

The interviews showed that structures can also concern regulations, as well as a whole municipality making a decision without taking into account the specific needs of schools, and the even more specific needs of various vocational programmes. When these interviews were conducted, the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) was relatively new. This was the major structural obstacle discussed by everyone. This regulation led to the banning of a lot of free software that teachers had been using, as it was difficult to comply with the requirement to determine how much information was collected by third parties, for example. Employers did not want to risk liability for the inadequate handling of personal data:

We have had one, as you say, logbook via Facebook. […] Then the supervisor and students and teachers join, […] all students have been able to read each other’s [comments], because we […] learn from each other. But now [everyone] has become so afraid here of this new law. So now they do not want us to use Facebook. So, at the moment we do not have a good digital channel that we can use. But we’re looking into it. [Alicia, Care and Treatment]

A lack of suitable material at different levels was described in various ways. Below, Mary tells about problems with workplace supervisors not having email addresses, and students not having computers to work on, and these became structural problems:

It’s extremely difficult [to keep in touch with the supervisors at the workplaces], because there are those who don’t even have an email address. […] But what if you could take care of everything via email and do it digitally. I would like to have it all digitally, but it is difficult. […] I mean, if they [the students] had their own computers, we would have been in a completely different situation right away. They could have sat down directly and worked. Now they have to collect everything on their phones and then they will have to process it when they return to school, if they do not have computers at home. [Mary, Animals]

Stephen pointed at the difficulties supervisors have in following up on students’ progress when there are different work placements for different placement periods. Digital cloud services could allow student records to accompany them from one workplace to the next, according to Stephen:

Often, they change supervisors, change workplaces, which can mean that you need to take over material. Yes, there is some kind of move-over-thought there. You need to transfer material to a new supervisor, because he or she should actually be able to see what has been done before. Often, it is completely concealed because you change the name, and you turn over a new leaf, so to speak. That supervisor has not seen what the other supervisor had written [at] the previous workplace. And it’s like having a meeting without reading the previous minutes. […] What if you could come out and sit down with a new supervisor and say: This is what we did at the previous place, now I’ll add you here on this page, if it’s okay, you start to fill this in and we will pass it on. So, Charlie, who is learning to be a bricklayer, has already done a lot of brickwork. So maybe he should learn a bit more about rendering. [Stephen, Construction]

Here, it was clear how different the same phenomenon can appear in various contexts. Mary, who described above that a supervisor refused email, states that this can still be handled, because ‘the students will be assigned to different workplaces, so they won’t always be at the same place.’ What Stephen described as a challenge, Mary deemed less problematic. Stephen continued the above reasoning and elaborated on how their records could accompany students into proper employment. He claims that collaboration is required between different parties: the National Agency for Education, the trade, and the school. Stephen described envisioning a system similar to that which the students will use later in working life, and saw using such a system already in school as a win-win situation. The descriptions above clearly show that the factors linked to the structural aspect are closely intertwined with those linked to the material, but as several of the teachers pointed out, they also concern priorities at several levels.

The cultural aspect

The cultural aspect concerns ideas and beliefs. In the analysed narratives, the obstacles and challenges described for example, included the fact that teachers and school managers could express different views on learning and education, as well as on the possible or permissible uses of technology. Maintaining contact with the workplaces using digital technology, without relying on the students as go-betweens, requires supervisors to be interested in keeping in touch. When teachers feel that this is not the case, they must find alternative solutions. To some extent, this challenge could be related to a lack of technological competence among the supervisors, but more often the teachers stressed the fact that workplace cultures did not always permit technology use. Construction teacher Stephen argued that the problem was that students could not use mobile devices during work placements at construction sites; the culture of these workplaces signals that mobile phones should not be used at construction sites. This culture can also be recognised at other workplaces, even if it is expressed differently. Mary also mentioned several supervisors who were reluctant to use information and communication technology:

I have a supervisor who doesn’t even have email! […] It’s true. My only options are the phone or visits. That is a disadvantage, and that is one of the best places I have [laughs], he just refuses to use the computer. [Mary, Animals]

Even supervisors who use advanced technology in their professions can be reluctant to use digital technology to bridge the gap between school and workplaces. However, there are examples of teachers who emphasised that they believe in long-term change. Stephen said, for example, that more and more young supervisors were used to working with digital tools as learning platforms from their own schooling. According to Stephen, these young supervisors would find it easier to accept working with digital tools in relation to students’ education. The teachers also provided examples of how several actors in their schools have an attitude of restraint towards the use of digital technology in vocational education. Not just workplace supervisors were reluctant; colleagues at school or even the students themselves may resist the use of technology. According to Lily, many students preferred using pen and paper, but things were starting to change. She said:

And it’s about the resistance, it can be anywhere – just logging in can be a problem for them [the students]. […] I think it’s starting to change step by step. […] They are not as afraid of it as they used to be. […] Today, the computer is not a problem, today there is a discussion about mobile phones […]. For me, it is not black or white. [Lily, Handicrafts]

The following quote is an example of how the three aspects are intertwined. Stephen talked about costs, which is a material aspect. The fact that the school does not work on the issue can implicitly be a structural aspect, but here we highlight it as an example of attitudes at the school:

It is not the supervisors themselves, I think, but it’s the school that doesn’t really see the benefit. Or yes, they see the benefit, want the benefit, but actually do not really see that it costs money, or that it costs time, or that you actually have to set aside opportunities for this. [Stephen, Construction and Installation]

Teacher Sophie highlighted cooperation and how it could be enacted to varying degrees. She sees the integration of school subjects as beneficial to the students as well as the workplaces. To her, this involves a deeper collaboration than just keeping each other informed or doing similar activities. The interviewer asked if Sophie had not found any solutions that worked:

No, they [the other teachers] didn’t understand. They did not understand. We will integrate topics. “Yes, then I will create a task in your task?” “No! But the students have to do the task and then we have to look at it with different glasses. On the other hand, as a competition entry or business plan or something like that. For me, you can just as easily do it in English. It does not matter to me. If your students reach your course goal better that way“- but, no. […] The same teacher then had three weeks of projects in social media, Instagram, communication and not subject-integrated when it’s such a big feature in my courses, it is … sad. Sad! But they do not understand, they really do not understand what it means. […] I think that’s the attitude to digitalisation. I don’t think it has anything to do with the actual knowledge, because I wouldn’t say that I myself am a top expert on digitalisation. But I like digitisation. I like looking for opportunities. So, I think it’s the attitude towards digitisation that bothers me. [Sophie, Business and Administration]

In her narrative, Sophie elaborated on why some colleagues did not want to cooperate. She talked about closed classroom doors and different views on school and learning among teachers. This could also be a view of technology. Reading between the lines of Sophie’s – and to some extent Stephen’s – narratives, we interpret this as a view on how technology is used in school that is closely linked to teachers’ epistemological approaches to their different subjects. Today Swedish teachers increasingly teach in teams. The interviewees described difficulties in finding colleagues who wanted to collaborate. Collaboration concerns views of teaching and learning as well as views of digital technology.

The different aspects are intertwined, but our analysis identified the obstacles and challenges faced by vocational teachers who want to use digital technology to bridge the gap between school and workplaces. Challenges come in various forms and at different levels of our hierarchical model.

Summary of results

The teachers provided examples of many solutions they would like to put into practice to develop their teaching, such as collaboration with colleagues, or using or developing specific apps. Most problems were related to the schools’ equipment, which was similar at the different schools. Following Biesta et al.’s (Citation2015) model, the teachers experienced obstacles related to all three aspects of the practical-evaluative dimension.

Material aspect

A lack of economic resources when freeware could not be used, as well as lack of mobile phones allowing students to keep in touch more easily during placement periods.

Structural aspect

Between the two interviews, the new European General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) was implemented. Accordingly, schools feared doing something wrong when using digital tools. A lot of the freeware that teachers had used previously was banned by the management of several schools. Different technologies were not always compatible.

Cultural aspect

The interviewees described difficulties in finding colleagues who want to collaborate. Collaboration concerns views of teaching and learning as well as views of digital technology. These problems were also visible in collaboration with supervisors. The cultural aspect revealed that different vocations have differing views on mobile technology.

Based on earlier experiences, the interviewees gave examples of what could help them to continue bridging the gap. An important result is also that different professional fields have different needs – there is no single solution that could be implemented at all workplaces.

Discussion

Our results show that these vocational teachers had many reasons not to use technology, and these reasons are linked to different aspects in our theoretical framework. Such reasons vary depending on the context, but other categories of teachers can probably recognise several of the situations highlighted in the results. Our teachers were all considered positive to the use of digital technology, yet they still reported problems. Mary’s claim that she is ‘not good at it at all’ could be considered a lack of competence, as it may well be in surveys which do not always explore causes very deeply. However, self-reported competence does not always correspond to a more objective measure of competence (see Kruger & Dunning, Citation1999), and is here rather the understanding that there is more to learn.

The teachers in this study provided many examples of solutions they would like be implemented to better bridge the gap between school and workplaces, such as collaboration with colleagues, or using or developing specific apps. These solutions are considered to be at different levels in the hierarchical model described above (Enochsson et al., Citation2020; Kilbrink et al., Citation2020). When looking at the obstacles in relation to this model to find out where in the teachers’ development processes they arise, it seems that the different aspects also concern different levels. There are no clear divisions between the different aspects, but as for the hierarchical model, there seems to be a fundamental obstacle concerning material aspects, and mentioned by all teachers. National statistics indicate that all Swedish schools have access to digital tools/computers and the internet (SNAE, Citation2019), yet the interviewed teachers claimed that the technology is inadequate to meet their pedagogical aims (see Haydn & Barton, Citation2007). Problems can involve hardware as well as software, or compatibility. At the next level, obstacles relate to the structural aspect. Those obstacles are more specific, and include not being allowed to use social media or certain chat apps, which some branches may benefit from. All teachers do not encounter obstacles related to the cultural aspect, or some describe them as less severe. Teachers who want to change the organisation of education face the most difficult obstacles related to the cultural aspect, as they experience disagreement on how education should be organised.

The interviewed teachers were chosen because they were known to use digital technology, and their reasons for not using it are neither their attitudes (see Gudmundsdottir & Hatlevik, Citation2018; Lucas et al., Citation2021) nor a lack of competence or training (see Lindeman et al., Citation2021; SNAE, Citation2019). Not using digital tools to the extent requested by the authorities is shown to be more complex. Asking teachers or students to what extent digital media are used at schools does not result in a sufficiently detailed picture of the measures that have to be taken to increase their use – if that is the aim. Attitudes are important (Lucas et al., Citation2021), but being an enthusiastic teacher with many ideas does not ensure that digital boundary objects can be used successfully to bridge the gap between school and workplaces (Enochsson et al., Citation2021).

This study examined the narratives of five teachers. They were given ample time to elaborate on their thoughts in the interviews, which is necessary to discover a multitude of nuances. However, it is clear that our results warrant further investigation. The interviewees were all enthusiastic teachers full of ideas, and they wanted to improve their teaching by using digital technology in various ways. For teachers with no interest in using digital technology (see Buskqvist & Enochsson, Citation2012; Enochsson, Citation2017), the results might be completely different. Nevertheless, our results show a need for more than in-service training to increase the use of digital technology in schools. As opposed to many other teachers, vocational teachers also have to deal with other workplaces and the students’ placement supervisors (see Cattaneo & Barabasch, Citation2017), thus rendering the process even more complex. Based on earlier experiences, the interviewees gave examples of how they could be assisted in continuing to bridge the gap between school and workplaces. An important result is also that different professional fields have different needs, and that there is no single solution that could be implemented at all workplaces.

Conclusion

The primary focus on teachers’ non-use of digital technology in education has often been on reluctant teachers or those who claim to lack digital competence (cf. Enochsson & Rizza, Citation2009; Gill et al., Citation2015; Tondeur et al., Citation2016). This study shows that there is a need to move beyond attitudes and hands-on skills to better understand teachers’ needs. Our study demonstrates that a more comprehensive understanding may be reached of why technology is used or not used as boundary objects to cross boundaries in vocational education. The teachers in our study wanted to use technology to develop their teaching, the programme and/or implement a more holistic perspective on education. The obstacles they encountered sometimes made this impossible. At first sight, obstacles pertaining to technology may appear to only concern technology itself, but they also hinder teaching progress in general.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ann-Britt Enochsson

Ann-Britt Enochsson (PhD) is Professor of Educational work at Karlstad University. Enochsson has a long record of research on digital technology in educational settings in general, and also specifically on communication with technology.

Nina Kilbrink

Nina Kilbrink (PhD) is Associate Professor of Educational work at Karlstad University. Her research interests concern for example technical and vocational education, teaching and learning, the relationship between theory and practice, ICT in education and professional learning.

Annelie Andersén

Annelie Andersén (PhD) is Assistant Professor of Educational work at Karlstad University. Her research focuses on culture and (social) identity in education and at work, as well as teachers’ role in learning in vocational and higher education.

Annica Ådefors

Annica Ådefors (BA) is Lecturer of Educational work at Karlstad University. Ådefors has been working as a qualified vocational teacher since 2009 and has worked as a lecturer in vocational teacher education at Karlstad University since 2014.

References

- Aarkrog, V. (2005). Learning in the workplace and the significance of school-based education: A study of learning in a Danish vocational education and training programme. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 24(2), 137–147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370500056268

- Akkerman, S., & Bakker, A. (2011). Boundary crossing and boundary objects. Review of Educational Research, 81(2), 132–169. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654311404435

- Akkerman, S., & Bakker, A. (2012). Crossing boundaries between school and work during apprenticeships. Vocations and Learning, 5(2), 153–173. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-011-9073-6

- Angeli, C., & Valanides, N. (2009). Epistemological and methodological issues for the conceptualization, development, and assessment of ICT–TPCK: Advances in technological pedagogical content knowledge (TCPK). Computers & Education, 52(2009), 154–168. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2008.07.006

- Berner, B. (2010). Crossing boundaries and maintaining differences between school and industry: Forms of boundary‐work in Swedish vocational education. Journal of Education and Work, 23(1), 27–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080903461865

- Biesta, G., Priestly, M., & Robinson, S. (2015). The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teachers and Teaching, 21(6), 624–640. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044325

- Buskqvist, U., & Enochsson, A.-B. (2012, October 25–26). Digital kompetens som förutsättning och lärandemål i nätbaserad utbildning. Paper presented at NORDPRO, AArhus Oct, Denmark.

- Cattaneo, A., & Aprea, C. (2018). Visual technologies to bridge the gap between school and workplace in vocational education. In D. Ifenthaler (Ed.), Digital workplace learning. Bridging formal and informal learning with digital technologies (pp. 251–270). Springer.

- Cattaneo, A., & Barabasch, A. (2017). Technologies in VET: Bridging learning between school and workplace – The “Erfahrraum Model”. [bwp@ Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik], 33, 1–17. http://www.bwpat.de/ausgabe33/cattaneo_barabasch_bwpat33.pdf

- Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- CMA. (2009). Internet och lärarutbildningen: Om lärarstudenters och lärarutbildares attityd och användning av IT [Internet and Teacher Education: About Student Teachers’ and Teacher Educators’ Attitudes and Use of ICT]. Centrum för Marknadsanalys.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2000). Research methods in education (5th ed.). Routledge.

- DEAG – Digital Education Advisory Group. (2015). Beyond the classroom: A new digital education for young Australians in the 21st century. https://wlps.wa.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/deag_final_report-2.pdf

- ED – United States Department of Education. (2016). Future ready learning: Reimagining the role of technology in education. Office of Educational Technology. https://tech.ed.gov/files/2015/12/NETP16.pdf. Accessed 20 January 2017.

- Emirbayer, M., & Mische, A. (1998). What is agency? American Journal of Sociology, 103(4), 962–1023. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/231294

- Enochsson, A.-B., & Ribaeus, K. (2020). Everybody has to get a chance to learn: Democratic aspects of digitalisation in preschool. Early Childhood Education Journal. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01117-6

- Enochsson, A.-B. (2017, August 22–25). Digital literacy as a prerequisite in online teacher education. Paper presented at ECER 2017 in Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Enochsson, A.-B., Kilbrink, N., Andersén, A., & Ådefors, A. (2021). Att ständigt behöva tänka om: Ett yrkesdidaktiskt dilemma i digitaliseringens spår [The constant need to rethink: A vocational teaching dilemma in the wake of digitalisation]. In J. Kontio & S. Lundmark (Eds.), Yrkesdidaktiska dilemman(pp. 299–322). Natur & Kultur.

- Enochsson, A.-B., Kilbrink, N., Andersén, A., & Ådefors, A. (2020). Connecting school and workplace: Teachers’ narratives about using digital technology as boundary objects. Nordic Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 10(1), 43–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3384/njvet.2242-458X.2010143

- Enochsson, A.-B., & Rizza, C. (2009). ICT in initial teacher training: Research review. (Education Working Paper; 38). OECD.

- EU – European Union. (2020). Digital education action plan 2021–2021: Resetting education and training for the digital age. https://ec.europa.eu/education/sites/default/files/document-library-docs/deap-communication-sept2020_en.pdf

- Freeman, M. (2010). Hindsight: The promise and peril of looking backward. Oxford University Press.

- Gill, L., Dalgarno, B., & Carlson, L. (2015). How does pre-service teacher preparedness to use ICTs for learning and teaching develop through their degree program?”. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(1), 36–59. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2015v40n1.3

- Gudmundsdottir, G., & Hatlevik, O. (2018). Newly qualified teachers’ professional digital competence: Implications for teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 41(2), 214–231. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2017.1416085

- Haydn, T. A., & Barton, R. (2007). Common needs and different agendas: How trainee teachers make progress in their ability to use ICT in subject teaching: Some lessons from the UK. Computer & Education, 49(4), 1018–1036. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2005.12.006

- Illeris, K. (2009). Transfer of learning in the learning society: How can the barriers between different learning spaces be surmounted, and how can the gap between learning inside and outside schools be bridged? International Journal of Lifelong Education, 28(2), 137–148. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370902756986

- Kilbrink, N. (2013). Lära för framtiden: Transfer i teknisk yrkesutbildning [ Learning for the future: Transfer in technical vocational education, in Swedish] [Doctoral dissertation]. Karlstad University Studies.

- Kilbrink, N., Enochsson, A.-B., Andersén, A., & Ådefors, A. (2021). Connecting school and workplace-based learning in dual vocational education – Using digital boundary objects. In E. Kyndt, S. Beausaert, & I. Zitter (Eds.), Developing connectivity between education and work: Principles and practices (pp. 119–136). Routledge.

- Kilbrink, N., Enochsson, A.-B., & Söderlind, L. (2020). Digital technology as boundary objects: Teachers’ experiences in Swedish vocational education. In C. Aprea, V. Sappa, & R. Tenberg (Eds.), Connectivity and Integrative Competence Development in Vocational and Professional Education and training(ZBW-B, Band29,pp. 233–251). Franz Steiner Verlag.

- Knowledge Foundation. (2006). IT i skolan: Attityder, tillgång och användning [ ICT in schools: Attitudes, Access and Use].

- Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121

- Krumsvik, R. (2011). Digital competence in Norwegian teacher education and schools. Högre Utbildning, 1, 39–51.

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). InterViews. Sage.

- Lärarförbundet. (2020). Felsökning pågår: It i skolan behöver en omstart: En rapport om den digitala arbetsmiljön i skolan [ Diagnostics in Progress: Reboot Educational IT use: A Report on the Digital Work Environment in School].

- Lindeman, S., Svensson, M., & Enochsson, A.-B. (2021). Digitalisation in early childhood education: A domestication theoretical perspective on teachers’ experiences. Education and Information Technologies, 26(4), 4879–4903. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10501-7

- Lucas, M., Bem-Haja, P., Siddiq, F., Moreira, A., & Redecker, C. (2021). The relation between in-service teachers’ digital competence and personal and contextual factors: What matters most? Computers & Education, 160(2021), 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104052

- Ministry of Education and Research. (2017). Nationell digitaliseringsstrategi för skolväsendet [ National Digitalisation Strategy for the School System].

- Nordicom. (2008). Sveriges internetbarometer [ The Swedish internet Barometer] 2007 (No 2/2008. Nordicom-Sweden.

- Polkinghorne, D. (1995). Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 8(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0951839950080103

- Priestley, M., Biesta, G., & Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher agency: An ecological approach. Bloombury Academic.

- Salaway, G., Caruso, J. B., & Nelson, M. R. (2008). The ECAR study of undergraduate students and information technology, 2008. EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research.

- Sappa, V., Choy, S., & Aprea, S. (2016). Stakeholders′ conceptions of connecting learning at different sites in two national VET systems. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 68(3), 283–301. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2016.1201845

- Schaap, H., Baartman, L., & de Bruijn, E. (2012). Students’ learning processes during school-based learning and workplace learning in vocational education: A review. Vocations and Learning, 5(2), 99–117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-011-9069-2

- Schwendimann, B., Cattaneo, A., Dehler Zufferey, J., Gurtner, J., Bétrancourt, M., & Dillenbourg, P. (2015). The ‘Erfahrraum’: A pedagogical model for designing educational technologies in dual vocational systems. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 67(3), 367–396. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2015.1061041

- Selwyn, N. (2016). Is technology good for education? Polity Press.

- SNAE, Swedish National Agency for Education. (2019) . Digital kompetens i förskola, skola och vuxenutbilding.

- Tanggaard, L. (2007). Learning at trade vocational school and learning at work: Boundary crossing in apprentices’ everyday life. Journal of Education and Work, 20(5), 453–466. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080701814414

- Tondeur, J., van Braak, J., Ertmer, P., & Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. (2016). Understanding the relationship between teachers’ pedagogical beliefs and technology use in education: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Education Technology Research and Development, 65(3), 555–575. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-016-9481-2

- Tynjälä, P. (2009). Connectivity and transformation in work-related learning: Theoretical foundations. In I. M. Stenström & P. Tynjälä (Eds.), Towards integration of work and learning (pp. 11–37). Springer.

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). Sage.