ABSTRACT

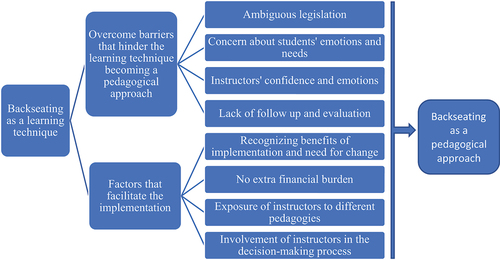

Flight training is a lengthy and resource-intensive process with additional learning, and teaching techniques are often overlooked. One technique is observational learning, or backseating in aviation training, which can accelerate pilot training. This study aimed to analyze the factors that facilitate and hinder the implementation of backseating in flight schools. The perceptions of students, instructors, and managers were investigated using an ethnographic approach. The results show that recognizing the benefits of implementation and the need for change, no extra financial burden, exposure of instructors to different pedagogies, and involvement of instructors in the decision-making process would facilitate the implementation of backseating. Additionally, factors such as practicality issues for implementation, concern about students’ needs, instructors’ self-confidence and emotions, lack of follow-up by managers, and regulatory ambiguity hinder implementation. To implement backseating, legislative ambiguity, instructors’ confidence and emotions, and their concerns about students’ needs should be addressed.

1. Introduction

The current instructional methods in flight training have remained the same since World War II (Franks et al., Citation2014; Socha et al., Citation2018). Given that flight training is highly resource-intensive in time and cost, making it difficult for students to afford (Callender et al., Citation2009; Cui et al., Citation2022; Weelden et al., Citation2021), the field of aviation has tried many different approaches to accelerate training without much success, such as competency-based training (CBT) (Franks et al., Citation2014) and multi-crew pilot licensing (MPL) (Wikander & Dahlström, Citation2016).

CBT teaches and assesses complex skills by breaking them into simple skills. There are concerns that there are better approaches than CBT to improve flight training. The industry needs help to interpret and implement CBT requirements. Accordingly, its utility needs to be better understood (Hattingh et al., Citation2022). Following the CBT implementation, apprentices tend to achieve minimum acceptable levels of competence instead of aiming for excellence (Franks et al., Citation2014). The implementation of CBT has resulted in declining standards; it is a concern that competency standards represent lower standards (Harris & Hodge, Citation2009).

Linked to CBT, MPL focuses on training pilots to become first officers in a particular commercial aircraft type linked to a specific airline. MPL locks the pilots in that aircraft model for a particular airline, with no possibility for the pilot to operate the same aircraft in another company or fly smaller aircraft (Adanov et al., Citation2020; Valenta, Citation2018). The true effect that MPL has on the performance of pilots has been a major topic of debate (Wikander & Dahlström, Citation2016).

One often overlooked learning technique and pedagogical approach is observational learning, which could improve quality and reduce flight training length. Observational learning is ‘the acquisition of attitudes, values, and styles of thinking and behaving through observation of the examples provided by others’ (Bandura, Citation2008, p. 1). In aviation, observational learning is also known as backseating, which involves a student conducting flight observations from the backseat of the aircraft while another student undertakes their flight lesson. The term ‘observational learning’ is used in the paper to refer to the learning technique in general terms, when it is not applied to the aviation context. However, the term ‘backseating’ is employed when specifically referring to observational learning in flight training. Through backseating, students can integrally dedicate their attention to what is happening in the flight because they are not flying the aircraft. Therefore, they can see how other students perform, the mistakes committed, and the flight instructor’s comments and even be aware of their surroundings (Biederman, Citation2016a). Ultimately, this learning technique allows students to be more exposed to flying without adding extra cost to the training (Schwarz, Citation2004).

This learning technique is not widely adopted in flight schools despite the benefits of backseating flights (Biederman, Citation2016a, Citation2016b; Schwarz, Citation2004). Most training flights fly without anyone in the back seat (Biederman, Citation2016a). Many students should know that backseating flight lessons are an option (Biederman, Citation2016b; Schwarz, Citation2004).

Making changes in a curriculum and adopting a new pedagogical approach is not easy, as people often feel resistant to change. Teachers may feel secure teaching the same way they have been, and it might be easier to keep the same techniques than adopt any changes (Altinyelken, Citation2013). An example of the difficulty of adopting a new pedagogical approach is backseating. Regardless of being beneficial for students learning in ab initio pilot training, this learning technique has yet to be adopted as a pedagogical approach. To implement a new pedagogical approach, such as backseating, knowing which barriers should be overcome and what would facilitate the implementation is necessary. Therefore, the objective of this study was to describe the factors that facilitate and hinder the implementation of backseating in flight schools in Australia, according to the viewpoints of managers, instructors, and students. By providing information about these factors, flight schools, and aviation authorities would know what measures need to be put in place for backseating to become a learning technique and a pedagogical approach in the early stages of pilot training.

2. Literature review

2.1. Definition of observational learning and its characteristics/benefits

Coined by Bandura in the 1970s (Borsa et al., Citation2019; Ferrari, Citation1996; Fryling et al., Citation2011), the term observational learning refers to the process through which students learn by watching peers perform the tasks they are being taught (Groenendijk et al., Citation2013). Through observational learning, individuals can learn by observing instead of directly experiencing the action’s consequences (Yoon et al., Citation2021). In observational learning, the individual does not merely copy an action but instead transforms the observation into the most similar action possible in alignment with the goal of the task (Torriero et al., Citation2007). It is essential for learning to reflect on daily experiences to comprehend better one’s actions, which ultimately results in the development of skills. Hence, experience and reflection on experiences should be connected, allowing one to examine one’s actions and experience with the outcome of developing skills, which is known as reflective practice (Caldwell & Grobbel, Citation2013).

Therefore, observational learning can be beneficial to allow students to refine their skills (Watson & Livingstone, Citation2018). Learning by observation improves learning skills, especially when combined with physical practice. Neuroimaging experiments have demonstrated that when action production and observation co-occur, common neural structures are activated, making learning more effective (Wulf et al., Citation2010).

Physical practice is as essential to learning a new skill as observing the skill is (Heyes & Foster, Citation2002). However, when combined, learning new skills can be faster (Blandin et al., Citation1999). Observational learning is particularly favorable in high-risk training environments, where the safety of people is at stake when procedures are not done correctly. Aviation and medical training are examples of areas where mistakes can cost lives. For example, in medical training, research has shown that observational learning improves the development of motor skills when applied in combination with physical practice in a cost-efficient way, which makes the learning process and skills acquisition faster and more effective (Cordovani & Cordovani, Citation2016; Wulf et al., Citation2010).

Alternating observations with physical practice is better than merely observing or fully doing one before the other (Cordovani & Cordovani, Citation2016; Shea et al., Citation2000). Nevertheless, studies suggest that observing a skill being performed activates cognitive processes similar to those that arise during the physical practice of a skill (Blandin et al., Citation1994; Heyes & Foster, Citation2002; Shea et al., Citation2000). Shea et al. (Citation2000) demonstrated that when half of the lessons that require physical practice are replaced with observation, the performance increases compared to the training that solely uses physical practice. This means that combining physical and observational practice can be more effective than physical or observation alone.

2.2. Observational learning in pilot training

Learning by observing is recognized by the Federal Aviation Administration as a way for student pilots to acquire flying skills. According to the FAA, instructors should encourage students to observe other pilots to strengthen their learning, allowing them to process what has been learned and reflect upon themselves. A demonstration is also a type of observational learning; in in-flight lessons, the instructor generally demonstrates the steps necessary to perform the skill. Then, the student practices the steps and performs them in front of the instructor (FAA, Citation2020). Although demonstration and backseating are part of observational learning, they differ in that during a demonstration; the instructor shows the student in control of how the skill should be performed, whereas, during backseating, a student learns by observing the student in the front performing their duties.

In the context of in-flight training, backseating involves a student sitting in the spare seat of an aircraft observing another student during a one-on-one flight session with an instructor. During the lesson, the student in charge of the controls carries out the tasks that the student on the back has executed or will have to execute during their lesson. The observing student can pay attention to the flight dynamics in a relaxed, stress-free environment, as they are not in charge of flying the aircraft. The advantage of this learning technique is that the student can perceive aspects of flying that they would otherwise not be able to notice while flying, as they do not have any pressure to manipulate the controls. With backseating, student pilots learn from the mistakes of the student performing the flight, and they know which mistakes they may have committed or should avoid making in future lessons. Moreover, through this learning technique, students backseating can listen to the instructors’ explanations again, reinforcing their learning (Schwarz, Citation2004).

Although the literature on backseating is scarce, Schwarz (Citation2004) found that the learning technique makes a difference in the total flight training time. However, many students are not aware that they have the option of backseating their peer’s lessons, and those who are aware do not embrace the opportunity. During the study, 60 students were required to backseat two flights during the first block of training and another two flights during the second block of training. His study showed that students who backseated two and four flights needed, on average, 59.2 and 57.6 hours, respectively, to obtain their private pilot licenses compared to those who had not observed any flights that required 61.4 hours. These results demonstrate that the more flights a student observes, the quicker they learn and the less time they need to obtain their licenses. In the study, most flight instructors reported that backseating benefited students. The more beneficial instructors thought backseating was, the more likely they were to encourage students to backseat more lessons than required. The study by Schwarz (Citation2004) was one of the inspirations of this paper as it validates backseating as an effective learning and teaching technique for ab initio pilot training, and it proved that backseating can reduce flight training time and that the more students backseat, the less training time they require.

2.3. Implementation of a new pedagogy

Many factors can affect the implementation of a new pedagogy (see ). Students’ voices should be heard and considered to successfully implement a change. Involving students in the new approach’s development process enables them to have their own voice. As such, they may see the implementation as embracing the benefits of their own initiatives. Not considering students’ voices and not involving them in the implementation process can be detrimental and can make students disengage in class (Ngussa & Ndiku Makewa, Citation2014).

Table 1. Factors that affect the implementation of a new pedagogy.

Their previous learning experiences can condition students’ acceptance or resistance to the new approach. Students will accept and support the change if they have a previous positive experience. On the contrary, if students had a prior negative experience with a certain learning approach, it could negatively affect their perspective of the approach. Therefore, they can resist its implementation (Tolman & Kremling, Citation2017).

If students resist curriculum change, it can negatively affect their learning because they will engage less in class. Students will not make any effort required by the chance if they believe the new approach does not add value to their learning. Students can also resist the implementation if the chance requires an increased effort from them. In that case, even if the change enhances their learning, students may resist by feeling stressed from the additional effort required. However, that might be at the beginning of the implementation; student resistance may stop once students are convinced of the new approach’s added value. This process can take less time if the change is incrementally put in place. Once convinced of the additional value, students feel motivated to make the required effort to enhance their learning (Agrawal et al., Citation2020).

Moreover, the success of any implementation will also depend on teachers accepting change, so teachers’ resistance needs to be considered. A way to facilitate acceptance from educators is to involve them in the decision-making process and have their concerns addressed before implementing any changes. Teachers tend to be less enthusiastic about a new curriculum when not involved in its creation and implementation. Moreover, teachers might need specific training to deliver the new curriculum if they have not been involved in the implementation process (Simmons & MacLean, Citation2018).

Changes can be challenging and can negatively affect the confidence of teachers. Therefore, it is necessary to support teachers, preventing them from feeling so overwhelmed that they regress to their previous teaching methods (Zimmerman, Citation2006). It is essential to support teachers in the implementation phase to assist them in adapting to the change by providing clear guidelines, instruction from managers, and feedback on the efforts they are making to achieve the goals of the new curriculum (MacLean et al., Citation2015).

Another factor that impacts the adoption of a new pedagogy is the level of understanding teachers have about the need for that change. The better teachers understand why the curriculum needs to change, the more teachers will engage with the implementation (MacLean et al., Citation2015). Implementing a curriculum with clear goals and standards positively influences effective implementation by teachers. When the goals and standards of a curriculum are clear, teachers will feel more motivated to implement the curriculum. The level of training of lecturers is another factor that influences implementation. Lecturers with high levels of education training implement better new curricula than those who have received low levels of training (Rudhumbu, Citation2022).

Changing a teaching approach can be difficult, especially when the new approach might no longer be practical for students, and it has been the method used in the last few years (Brownell & Tanner, Citation2012). Teachers can perceive change as uncertainty, resulting in resistance and the need to cling to how things have always been done (Johns, Citation2003). Teachers’ resistance can be a factor that can significantly hinder the implementation of new pedagogy, especially when teachers believe the changes are threatening. Teacher resistance can originate as a defense mechanism when teachers must protect their well-established status and interests from threatening changes. Resistance can especially appear when teachers are in their late careers and they feel less inclined toward change. It can also arise from the teachers’ fear of losing what is familiar and comfortable. They can feel uncomfortable adopting something unfamiliar when their established teaching styles are disturbed. Teachers can feel resistant when they feel the changes are being imposed, as they can perceive the changes as disregarding the school’s concerns, needs, and priorities. Teachers can oppose the changes when they do not understand why the curriculum requires changes and believe that the implementation will deny their students’ needs (Altinyelken, Citation2013).

Teachers’ unwillingness to change their pedagogical philosophies and adapt to curriculum changes can be caused by the fear of change (Southren, Citation2015). Teachers have different conceptions about how students should acquire knowledge, which affects their teaching methods (Jin et al., Citation2021). Implementing new pedagogies can be incredibly challenging when teachers are satisfied with the current teaching because they are not motivated to engage in the new pedagogical approaches (Southerland et al., Citation2011).

Implementing educational changes is complex because teaching and learning can be inherently emotional. Teachers experience positive and negative emotions; to teach effectively, they need to feel positive emotions about what they are transmitting, including enthusiasm, excitement, and enjoyment. Teachers experiencing emotions such as powerlessness, disappointment, anger, or anxiety can negatively impact the implementation of a new curriculum. Negative emotions can arise when teachers believe the new curriculum goes against the relevant educational objectives. Thus, teachers’ emotions toward the change must be considered when implementing educational changes (Harper, Citation2012).

Managers play an essential role in adopting a new pedagogy, as their leadership affects the implementation success (Park & Jeong, Citation2013). An important facilitating factor for adopting a new approach is the involvement of the school principal, which shows that the change is being taken seriously (Nachmias et al., Citation2004). They must initiate the change, communicate it, and convince teachers to implement the new approach. Their role is also to create a process where the development is done collaboratively with teachers (Gouëdard et al., Citation2020). An additional role of the manager is to monitor the achievement of the change implementation and provide feedback to teachers about how they are implementing the new approach (Hsiao et al., Citation2008).

3. Methods

3.1. Ethnographic approach

Understanding students’, instructors’, and managers’ perceptions of adopting flight observations requires comprehending their narratives, actions, inactions, and behaviors. Therefore, the study conducted an ethnography, a method through which the researcher is completely immersed in a particular social context to obtain in-depth knowledge of the subjects of study (Queirós et al., Citation2017).

This ethnographic study was conducted at a flight school in Brisbane, Australia, where one cohort of ab initio student pilots at the flight school was the study object. The selection criteria for the flight school were (a) being representative of most flight schools in Australia, (b) being a CASA-approved flight school, and (c) specializing in recreational, private, and commercial pilot licenses.

The first author of this study played the role of an active member while remaining an engaged outsider. The member role was adopted to shed the outsider identity and to identify with the flight school, albeit without active participation (Angrosino, Citation2007). The ethnographer noticed she became part of the group when students and instructors ceased to act as if a stranger was in the room. This status was confirmed when the ethnographer entered the lecture room on 30 November 2021 (the second week of the training program), and the students and instructors did not turn around. The ethnographer also took five flight lessons to put herself in the place of the students, be able to relate to them and hence obtain a deep comprehension of what students experience when they first learn to fly.

Ethics approval was received from the Griffith University Ethics Committee (#2021/718). Data were collected while students undertook their Recreational Pilot License and Private Pilot License between 22 November 2021 and 14 April 2022. The first author conducted observations and in-depth interviews, spending approximately 300 hours in the flight school during that period.

3.2. Participants’ profile

The cohort included five students enrolled in the Graduate Diploma in Flight Management degree. The flight school and university partner jointly deliver this program, with two annual intakes. The cohort part of this study started in the second intake of the year. Despite having other students from other intakes enrolled in the program, only the five students comprising that intake cohort were observed and interviewed.

In addition to the students, the three flight instructors actively involved with this cohort participated in the research project. All instructors were CASA-certified and responsible for delivering lectures and one-on-one sessions in the simulator and the aircraft. The Chief Executive Office, the Chief of Operations, and the Base Manager were also interviewed, as they are directly engaged in teaching activities. In sum, eleven students and professionals participated in the study.

Data collection was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have resulted in the small sample size of the study. Nevertheless, following an ethnographic approach, the study covered all the participants of a subculture or group, in this case, a cohort of students. Ethnography focuses on the quality and extent of data per subculture or group, rather than on the number of participants. Therefore, in ethnography, the number of participants in a culture determines the sample size (Higginbottom, Citation2004).

3.3. Observations

The ethnographer immersed herself in the flight school and followed students around their daily routines. Students were observed during their daily tasks, including lectures and flight lessons on the aircraft and on the simulator. Given that the first author was in the flight and simulator session in the back seat of the aircraft, it is reasonable to assume she could take the perspective of a student conducting flight observation. This was confirmed by the Chief of Operations, instructors, and some students, given that she gained special permission to accompany the sessions.

The ethnographer backseated before the first solo, at the very early stages of the program, during the Recreational Pilot License. The ethnographer backseated six flights, all the flights that she was allowed to until students started practicing emergency procedures, which do not permit an observer on the backseat The six flight lessons the ethnographer backseated targeted the effects of controls, straight and level, as well as climbing and descending. Pre-flight checks, taxiing, and radio telephony to air traffic control were practiced in each of these flights. The ethnographer has yet to observe another backseater to see how they learnt from the process, as backseating was not implemented in the flight school. Every procedure observed was equally suitable for backseating, as long as the backseater uses a headset to hear the instructions provided by the instructor and the communications between student and instructor. Thus, the ethnographer did not find a particular part that is better facilitated than others by backseating.

Ethnographers must record field notes to recognize patterns and depend on their field notes to produce interpretations and conclusions (Hoey, Citation2014). The ethnographer kept daily field notes on a laptop and revised them at the end of each day. Field notes were taken while the ethnographer backseated flights and during any other situations and activities students undertook at the flight school. Field notes recorded during the daily routine of the students included information such as the activities that students performed, the tools they used, quotations containing any interesting comments students and instructors made during the lessons, any meaningful communication that occurred among them, or remarks about the students’ performance and struggles during specific tasks.

3.4. Interviews

The eleven participants were interviewed in depth for 45 minutes each on average. Participants were asked four open-ended questions about (1) their opinion regarding students backseating their peers’ flights, (2) the advantages of backseating, (3) the disadvantages of backseating, and (4) the challenges of adopting backseating at the flight school.

The interviews were recorded to ensure all information was included in the conversation. The recordings were transcribed through the Microsoft Teams transcription feature. Both the recording and the transcription were reviewed for any mistakes.

3.5. Data analysis

A thematic analysis was conducted on the interview transcriptions to identify common threads in the different answers (Bowen, Citation2009). Interview transcripts were read three times, and codes were assigned to each opinion of all 11 participants. Subsequently, codes were further categorized by agreements and disagreements of the answers provided by the three groups of people (students, instructors, and managers). Codes were then divided into two groups: commonalities of the answers linked to factors that facilitate implementing backseating and to factors that hinder it. Nine common themes emerged from the data, four on factors that facilitate the adoption of backseating (recognizing benefits of implementation and need for change, no extra financial burden, exposure of instructors to different pedagogies, and involvement of instructors in the decision-making process) and five on the factors that hinder it (practicality issues for implementation, concern about students’ needs, instructors’ self-confidence and emotions, lack of follow-up by managers and regulatory ambiguity).

Although the factors found in the literature review set the stage for what themes to look for in the data, the nine common themes were set based on thematic analysis and, therefore, on commonalities among the answers provided by the flight school’s students, instructors, and managers. Some associations were found between the literature review () and the data collected in this study, including recognizing the added value of implementation, the involvement of instructors in the decision-making process, previous exposure to the pedagogy, instructors- self-confidence, and emotions, and lack of follow-up by managers.

Additionally, the data were corroborated through data triangulation. This approach added depth to the collected data by examining the subject of study from different perspectives, thus mitigating any potential bias (Fusch et al., Citation2017). The data from the interview transcriptions were verified with the information recorded in the field notes during the observations conducted.

4. Results

4.1. Creating opportunity for backseating

According to a manager, the flight school’s curriculum was changed some years ago to accommodate backseating. The manager explained that emergency procedures were scattered throughout the curriculum before this change. Because backseating is not allowed when emergency procedures are being practiced, the curriculum was rearranged so that emergency procedures would be concentrated in some lessons. Moving the curriculum around ensured that some flight lessons would not involve practicing emergency procedures; therefore, students could backseat those procedures. However, despite this change in the curriculum, backseating was not adopted in the flight school.

Even though the curriculum was changed to accommodate backseating, it was not followed up by management to ensure that the changes were put in place and that everyone in the flight school implemented it.

4.2. The importance and necessity of flight observation

All instructors, managers, and students agreed that backseating flights are an opportunity for students to learn from each other’s mistakes, recognize patterns, and reinforce any specific areas that students might be struggling with. None of the parties involved disagreed with these benefits associated with flight observations.

Students reported the need to ask instructors to backseat other students’ simulator sessions when they struggled in certain areas. Although instructors agree most of the time and seem supportive, they usually do not advertise the opportunity of backseating simulator sessions among students.

Students revealed that backseating flights would also benefit their learning, especially at the early stages of the training when everything is new. They reported that this learning technique would allow them to familiarize themselves with the cockpit and mentally prepare for what they would have to go through during their own lessons. They believe it would allow them to learn in a stress-free environment where they would not feel pressured to perform well because they would not be in charge of the controls. A student pilot said, ‘watching the reaction and the feedback and what sort of pointers they give makes me more prepared for the next flight’. Every time a student finished their flight lesson and returned to the lecture room, the ethnographer witnessed how the other students asked many questions to the student about the flight lesson that they just undertook. It was perceived that students found reassurance in knowing how their peers performed, the type of mistakes they made during the flight, and the feedback provided by the instructor.

4.3. No extra financial burden

The fact that backseating would not affect the cost of such training was reported as one of its main benefits. Instructors and managers agreed that backseating allows students to obtain extra experience inside an aircraft without incurring extra costs. The difference in fuel needed to carry one extra person would be insignificant and would not be noticeable. As explained by one of the managers, ‘I would never charge a student for backseating; what a crazy thing. It costs us nothing, so why put any kind of barriers to students doing it?’

Students found the high cost of flight training stressful. They expressed that backseating flights are attractive because they would get more time in the air without paying any extra money. For students, it was important not to have to worry about increasing the cost of the training. Students found reassuring the idea of being exposed to the expertise of the instructors while physically in the aircraft for more hours without having to incur any extra cost.

4.4. The belief that the new pedagogy would not be beneficial for all students equally

One of the concerns shared by instructors is that students receive unequal training. One of the instructors believed that the bad part is that the students do not have an equal amount of training; someone has to be first, right? (…) it’s not fair to the first student that the next student got to have that experience without them getting to have that experience also. Another instructor disagreed and noted that when he backseated during his training, students would alternate on being the ones to be observed so that none of them would be at a disadvantage. Any other instructor, managers, or students did not mention this concern. To avoid this potential issue, students could therefore rotate and take turns being the first one to be observed to avoid anyone being at a detriment.

4.5. Not considering the implementation to be practical due to time constraints

Lack of time in students’ current schedule was a reported issue. According to instructors, by implementing backseating, students’ time would not be wasted, as they can backseat any other students’ lessons whenever they do not have a flight class scheduled. However, students believed they might not have enough time to incorporate backseating into their curriculum. They showed concern about having their own flight lesson scheduled at the same time as their peers, preventing them from being able to backseat. Nonetheless, the ethnographer noticed that some students would employ the time while others had flight lessons to self-study the theory.

4.6. Concern about students’ emotions

Two of the instructors reported that students would not feel confident having their peers observing them from the backseat of the aircraft. According to one instructor, ‘if students are struggling, they may not want someone to backseat and embarrass them while they are sort of struggling and doing things wrong’. Only two instructors believed that students would get nervous about making mistakes in front of the student backseating their flight. However, another instructor disagrees, as he backseated every flight during his pilot training and only felt nervous at the beginning; as he got used to someone in the back of the aircraft, that pressure disappeared. For managers, learning to overcome the pressure and self-consciousness of being observed while flying is part of becoming an adult.

It stands out that only one student considered feeling self-conscious and nervous at the beginning if another student was backseating their flight lesson. Nevertheless, this student acknowledged that getting used to the presence of someone while flying would be beneficial in the long term since it would make them more confident pilots.

4.7. Instructors’ self-confidence and emotions

One manager believed that instructors use the pretext of students being more nervous when someone is backseating the flight as an excuse to prevent their teaching from being observed. He revealed that instructors might fear students comparing instructors, possibly leading to a bad reputation. The manager explained ‘how the instructor teaches (will be) compared to the other because people just talk, students just talk, and then the other instructors would talk’. He noted that this issue might be related to the instructor’s insecurity rather than the students’ insecurity regarding the presence of another student in the backseat.

4.8. Regulatory ambiguity

All instructors and managers mentioned that the current regulations need to state who is allowed to backseat a training flight clearly. Instructors indicated that in regulation CASR Part 91, a list of people allowed to participate in a training flight is provided by the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA): a supervisor, a crew member, an examiner, and an auditor. Nonetheless, this regulation does not contain the definitions for each of the permitted persons. Moreover, they reported another issue regarding the same regulation: students cannot backseat a training flight when practicing emergency procedures.

4.9. The belief that students will not embrace the new pedagogy

One manager believed that students would not embrace the opportunity that the new pedagogical approach could bring and expressed concerns that students might use backseating as an excuse not to be prepared for their flights.

According to one of the managers, backseating could be a waste of time for students worrying they will not do anything useful with the time spent in the aircraft. The manager noted that unless students are engaged during any activities while observing, the opportunity will not be embraced by students. The manager explained that when students asked him to backseat a flight lesson, he would only allow them if they were willing to perform some tasks. These activities included completing a mock navigation plan, making the relevant diversions, calculating the timing, helping to look for other airplanes flying nearby, verifying that the primary student was maintaining track, and calculating how far they were from the track.

5. Discussion

5.1. Factors that facilitate the implementation of a new pedagogy

5.1.1. Recognizing the benefits of implementation and the need for change

All participants agreed that the new pedagogy was beneficial for students learning and believed that through backseating, students could learn from the mistakes of the student in charge of the controls. The fact that students can learn new skills by observing someone else’s errors is corroborated by Brown et al. (Citation2010), Schuch and Tipper (Citation2007), and Tang et al. (Citation2022). Schuch and Tipper (Citation2007) indicate that observing another individual makes a mistake induces processes similar to when making such a mistake oneself. Learners can adjust their behavior to avoid making future mistakes without making these errors themselves. Moreover, observing a novice with poor performance contributes positively to students’ learning because they can recognize the gap between the novice’s performance and the desired outcome. These authors also note that observing a combination of correct actions and errors is more beneficial than observing only correct actions.

The fact that all participants recognized the new pedagogy to be beneficial for student learning is a factor that facilitates the implementation. According to MacLean et al. (Citation2015), teachers’ level of understanding of the need for change in a curriculum positively impacts the extent to which teachers engage with the implementation. Therefore, instructors’ understanding of why pedagogical change would be beneficial and needed for students would facilitate its implementation.

5.1.2. Exposure of instructors to different pedagogies

The exposure of instructors to different pedagogies is a factor that affects how supportive they are of a new pedagogical approach. The instructor who experienced backseating during their flight training was the only one fully supportive of the new approach. The other instructors who did not have previous exposure to backseating were not fully supportive of the new pedagogical approach.

5.1.3. Involvement in the decision-making process

Flight schools could benefit from involving instructors in the decision-making process of implementing backseating, as the literature suggests that the involvement of teachers in the decision-making process contributes to adoption by making them feel more enthusiastic about the changes (MacLean et al., Citation2015; Simmons & MacLean, Citation2018).

5.2. Factors that hinder the implementation of a new pedagogy

5.2.1. Instructors’ concerns about students’ needs

Instructors’ concern about students’ unmet needs was also found in the literature as a factor that hinders the implementation of a new curriculum. Altinyelken (Citation2013) suggests that teachers’ resistance can arise when they believe the implementation will disregard their concerns and students’ needs.

5.2.2. Instructors’ confidence and emotions

Instructors show a lack of emotional connection to the process of backseating. It appears that instructors feel they need more confidence about having other students observe how they teach at the aircraft, fearing students would compare instructors, as one of the flight managers indicated. The literature corroborates that change can hurt teachers’ confidence (Zimmerman, Citation2006). Instructors may find it threatening that students would criticize how they teach compared to other instructors and fear losing their status within the flight school. This factor was also found in the literature, suggesting that when teachers consider the changes threatening, they can resist the implementation to protect their status (Altinyelken, Citation2013). The negative emotions of powerlessness or anxiety instructors might feel about flight observations could hinder the implementation. This factor is corroborated by Harper (Citation2012), who also suggests that teachers’ negative emotions can hinder the implementation of new pedagogy, and as such, they should be considered.

5.2.3. Lack of follow-up and evaluation

Although the manager had changed the curriculum to accommodate backseating, its implementation needed to be followed up and evaluated hindered the adoption of the pedagogy. As Conrad et al. (Citation2007) suggest, sometime after the implementation, the change should be reviewed to confirm whether the change was successfully established.

5.2.4. Ambiguous legislation

Regulatory policies can significantly influence implementing a new pedagogical approach (Rudhumbu, Citation2022). This factor was present in the results of this study, as regulations do not clearly state who is allowed to backseat a training flight, which can impede the implementation. CASA (Citation2021) states that crew members, auditors, and inspectors are the only people approved of backseat flight lessons. Nevertheless, it must clearly articulate whether a student would be allowed to do so. Moreover, the regulations need to more precisely state whether students can backseat when emergency procedures are being practiced during the flight lesson. Whether students can backseat negatively impacts the adoption of flight observations for flight training.

5.2.5. Backseating from learning technique to pedagogical approach

For backseating to become an adopted pedagogical approach, there are barriers that the learning technique needs to overcome (see ), such as instructors’ concerns about students’ needs, instructors’ confidence and emotions, lack of follow-up and evaluation from managers, and ambiguous legislation.

6. Conclusion

To improve the declining standards in flight training, the industry could benefit from more effective ways to improve without dramatically changing the curriculum, such as implementing backseating of flights. This paper describes the factors that facilitate and hinder the implementation of backseating in flight schools in Australia. Four main factors that facilitate the implementation were identified, including recognizing the benefits and need for change, no extra financial burden, exposure of instructors to different pedagogies, and involvement of instructors in the decision-making process. Five factors hinder such implementation: practicality issues, concern about students’ needs, instructors’ self-confidence and emotions, lack of follow-up by managers, and regulatory ambiguity.

Ensuring that instructors understand the need for change and involving them in the decision-making process would prevent resistance toward the change and ultimately facilitate the implementation of backseating flights. To adopt backseating in flight schools, the following recommendations are made: (1) rotating students so that they take turns backseating to ensure that all students have an equal amount of time, (2) allocating the same instructor to a student for teaching and backseating to prevent instructors from feeling nervous and worried that students will compare them with other instructors, (3) having students backseat in pairs to make sure that they have an equal amount of backseating and that no comparisons are made between instructors, (4) a meeting between regulators and flight schools to clarify the regulatory ambiguities, and (5) managers following up with instructors and students about the status of the backseating practice to ensure that the new pedagogical approach is in place.

This study could be limited by its small size. Previous cohorts at the flight school exhibited larger sizes, which were frequently double the size of the cohort included in this study. However, data collection was conducted in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have negatively influenced the number of students enrolled in flight training. Further research could explore the adoption of backseating by conducting a trial adoption in a flight school and interviewing students, instructors, and managers after the trial implementation has been carried out. Further studies could also investigate whether certain specific flight maneuvers are identified with a higher rate of achievability with backseating implemented as part of the flight training.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adanov, L., Efthymiou, M., & Macintyre, A. (2020). An exploratory study of pilot training and recruitment in Europe. International Journal of Aviation Science and Technology, 1(2), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.23890/IJAST.vm01is02.0201

- Agrawal, V. K., Khanna, P., Agrawal, V. K., & Hughes, L. W. (2020). Change in student perceptions of course and instructor following curriculum change. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 18(3), 481–516. https://doi.org/10.1111/dsji.12214

- Altinyelken, H. K. (2013). Teachers’ principled resistance to curriculum change: A compelling case from Turkey. Global Managerial Education Reforms and Teachers, 109. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Hulya-Altinyelken/publication/311509549_Global_Education_Reforms_and_the_Management_of_Teachers_A_Critical_Introduction/links/5849682b08ae82313e71028d/Global-Education-Reforms-and-the-Management-of-Teachers-A-Critical-Introduction.pdf#page=121

- Angrosino, M. (2007). Naturalistic observation. Left Coast Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315423616

- Bandura, A. (2008). Observational learning. In W. Donsbach (Ed.), The international encyclopedia of communication. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405186407.wbieco004

- Biederman, J. (2016a). The benefits of back seating, part one. Disciples of Flight, https://disciplesofflight.com/benefits-back-seating-free-flying-lessons-part-one/

- Biederman, J. (2016b). The benefits of back seating, part two. Disciples of Flight. https://disciplesofflight.com/benefits-back-seating-pilot-skills-part-two/#:~:text=Back%20seating%20is%20a%20low,make%20you%20a%20better%20pilot.

- Blandin, Y., Lhuisset, L., & Proteau, L. (1999). Cognitive processes underlying observational learning of motor skills. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A, 52(4), 957–979. https://doi.org/10.1080/713755856

- Blandin, Y., Proteau, L., & Alain, C. (1994). On the cognitive processes underlying contextual interference and observational learning. Journal of Motor Behavior, 26(1), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222895.1994.9941657

- Borsa, D., Heess, N., Piot, B., Liu, S., Hasenclever, L., Munos, R., & Pietquin, O. (2019). Observational learning by reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and MultiAgent Systems. https://doi.org/10.5555/3306127.3331811

- Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027

- Brownell, S. E., & Tanner, K. D. (2012). Barriers to faculty pedagogical change: Lack of training, time, incentives, and … tensions with professional identity? CBE—Life Sciences Education, 11(4), 339–346. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.12-09-0163

- Brown, L. E., Wilson, E. T., Obhi, S. S., & Gribble, P. L. (2010). Effect of trial order and error magnitude on motor learning by observing. Journal of Neurophysiology, 104(3), 1409–1416. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.01047.2009

- Caldwell, L., & Grobbel, C. C. (2013). The importance of reflective practice in nursing. International Journal of Caring Sciences, 6(3), 319–326. http://www.internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org/docs/4.%20us%20La.Caldwell.pdf

- Callender, M. N., Dornan, W. A., Beckman, W. S., Craig, P. A., & Gossett, S. (2009). Transfer of skills from Microsoft flight simulator X to an aircraft. In 2009 International Symposium on Aviation Psychology (pp. 244). https://doi.org/10.22488/okstate.18.100364

- CASA. (2021). General operating flight rules. https://www.casa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-08/plain-english-guide-part-91-new-flight-operations-regulations-interactive-version.pdf

- Conrad, J., Deubel, T., Köhler, C., Wanke, S., & Weber, C. (2007, August 28-31). Change impact and risk analysis (CIRA): Combining the CPM/PDD theory and FMEA-methodology for an improved engineering change management. In International Conference on Engineering Design. https://doi.org/10.22028/D291-22482

- Cordovani, L., & Cordovani, D. (2016). A literature review on observational learning for medical motor skills and anesthesia teaching. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 21(5), 1113–1121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-015-9646-5

- Cui, S., Chen, Y., & Tao, H. (2022, August 3-5). An automatic approach for aircraft landing process based on iterative learning control. In 2022 IEEE 11th Data Driven Control and Learning Systems Conference (DDCLS). https://doi.org/10.1109/DDCLS55054.2022.9858388

- FAA. (2020). Aviation instructor’s handbook. https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/handbooks_manuals/aviation/aviation_instructors_handbook/

- Ferrari, M. (1996). Observing the observer: Self-regulation in the observational learning of motor skills. Developmental Review, 16(2), 203–240. https://doi.org/10.1006/drev.1996.0008

- Franks, P., Hay, S., & Mavin, T. (2014). Can competency-based training fly?: An overview of key issues for ab initio pilot training. International Journal of Training Research, 12(2), 132–147. 10.1080/14480220.2014.11082036

- Fryling, M. J., Johnston, C., & Hayes, L. J. (2011). Understanding observational learning: An interbehavioral approach. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 27(1), 191–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03393102

- Fusch, P. I., Fusch, G. E., & Ness, L. R. (2017). How to conduct a mini-ethnographic case study: A guide for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report, 22(3), 923–941. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2017.2580

- Gouëdard, P., Pont, B., Hyttinen, S., & Huang, P. (2020). Curriculum reform: A literature review to support effective implementation. OECD Education Working Papers, 239. https://doi.org/10.1787/efe8a48c-en

- Groenendijk, T., Janssen, T., Rijlaarsdam, G., & Van Den Bergh, H. (2013). The effect of observational learning on students’ performance, processes, and motivation in two creative domains. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(1), 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2011.02052.x

- Harper, H. (2012). Teachers’ emotional responses to new pedagogical tools in high challenge settings: Illustrations from the Northern Territory. The Australian Educational Researcher, 39(4), 447–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-012-0075-7

- Harris, R., & Hodge, S. (2009). A quarter of a century of CBT: The vicissitudes of an idea. International Journal of Training Research, 7(2), 122–133. https://doi.org/10.5172/ijtr.7.2.122

- Hattingh, A., Hodge, S., & Mavin, T. (2022). Flight instructor perspectives on competency-based education: Insights into educator practice within an aviation context. International Journal of Training Research, 20(3), 264–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/14480220.2022.2063155

- Heyes, C., & Foster, C. (2002). Motor learning by observation: Evidence from a serial reaction time task. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A, 55(2), 593–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724980143000389

- Higginbottom, G. M. A. (2004). Sampling issues in qualitative research. Nurse Researcher, 12(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2004.07.12.1.7.c5927

- Hoey, B. A. (2014). A simple introduction to the practice of ethnography and guide to ethnographic fieldnotes. Marshall University Digital Scholar, 2014. 10.1080/17439884.2013.770404

- Hsiao, H.-C., Chen, M.-N., & Yang, H.-S. (2008). Leadership of vocational high school principals in curriculum reform: A case study in Taiwan. International Journal of Educational Development, 28(6), 669–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2007.12.002

- Jin, H.-Y., Su, C.-Y., & Chen, C.-H. (2021). Perceptions of teachers regarding the perceived implementation of creative pedagogy in “making” activities. The Journal of Educational Research, 114(1), 29–39. 10.1080/00220671.2021.1872471

- Johns, D. P. (2003). Changing the Hong Kong physical education curriculum: A post-structural case study. Journal of Educational Change, 4(4), 345–368. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JEDU.0000006055.01460.eb

- MacLean, J., Mulholland, R., Gray, S., & Horrell, A. (2015). Enabling curriculum change in physical education: The interplay between policy constructors and practitioners. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 20(1), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2013.798406

- Nachmias, R., Mioduser, D., Cohen, A., Tubin, D., & Forkosh-Baruch, A. (2004). Factors involved in the implementation of pedagogical innovations using technology. Education and Information Technologies, 9(3), 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:EAIT.0000042045.12692.49

- Ngussa, B., & Ndiku Makewa, L. (2014). Student voice in curriculum change: A theoretical reasoning. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development, 3(3), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARPED/v3-i3/949

- Park, J.-H., & Jeong, D. W. (2013). School reforms, principal leadership, and teacher resistance: Evidence from Korea. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 33(1), 34–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2012.756392

- Queirós, A., Faria, D., & Almeida, F. (2017). Strengths and limitations of qualitative and quantitative research methods. European Journal of Education Studies, 3(9). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.887089

- Rudhumbu, N. (2022). Implementation of the technical and vocational education and training curriculum in colleges in Botswana: Challenges, strategies and opportunities. International Journal of Training Research, 20(2), 160–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/14480220.2021.1990106

- Schuch, S., & Tipper, S. P. (2007). On observing another person’s actions: Influences of observed inhibition and errors. Perception & Psychophysics, 69(5), 828–837. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193782

- Schwarz, T. J. (2004). Flight observations for initial flight students: Are they worthwhile? https://commons.und.edu/theses/406/

- Shea, C. H., Wright, D. L., Wulf, G., & Whitacre, C. (2000). Physical and observational practice afford unique learning opportunities. Journal of Motor Behavior, 32(1), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222890009601357

- Simmons, J., & MacLean, J. (2018). Physical education teachers’ perceptions of factors that inhibit and facilitate the enactment of curriculum change in a high-stakes exam climate. Sport, Education and Society, 23(2), 186–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2016.1155444

- Socha, V., Hanakova, L., Socha, L., Bergh, S. V. D., Lalis, A., & Kraus, J. (2018, August 30-31). Automatic detection of flight maneuvers with the use of density-based clustering algorithm. In 2018 XIII International Scientific Conference - New Trends in Aviation Development (NTAD). https://doi.org/10.1109/NTAD.2018.8551680

- Southerland, S. A., Sowell, S., Blanchard, M., & Granger, E. M. (2011). Exploring the construct of pedagogical discontentment: A tool to understand science teachers’ openness to reform. Research in Science Education, 41(3), 299–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-010-9166-5

- Southren, M. (2015). Working with a competency-based training package: A contextual investigation from the perspective of a group of TAFE teachers. International Journal of Training Research, 13(3), 194–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/14480220.2015.1077722

- Tang, Z.-M., Oouchida, Y., Wang, M.-X., Dou, Z.-L., & Izumi, S.-I. (2022). Observing errors in a combination of error and correct models favors observational motor learning. BMC Neuroscience, 23(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12868-021-00685-6

- Tolman, A. O., & Kremling, J. (2017). Why students resist learning: A practical model for understanding and helping students (1st ed.). Stylus Publishing, LLC.

- Torriero, S., Oliveri, M., Koch, G., Caltagirone, C., & Petrosini, L. (2007). The what and how of observational learning. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 19(10), 1656–1663. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2007.19.10.1656

- Valenta, V. (2018). Effects of airline industry growth on pilot training. MAD - Magazine of Aviation Development, 6(4), 52–56. https://doi.org/10.14311/MAD.2018.04.06

- Watson, P., & Livingstone, D. (2018). Using mixed reality displays for observational learning of motor skills: A design research approach enhancing memory recall and usability. Research in Learning Technology, 26, 26. https://doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v26.2129

- Weelden, E. V., Alimardani, M., Wiltshire, T. J., & Louwerse, M. M. (2021, September 8-10). Advancing the adoption of virtual reality and neurotechnology to improve flight training. In 2021 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Human-Machine Systems (ICHMS). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICHMS53169.2021.9582658

- Wikander, R., & Dahlström, N. (2016). The multi-crew pilot license part II: The MPL data-capturing the experience. Lund University School of Aviation. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/N-Dahlstrom/publication/304062538_The_MPL_Part_II_The_MPL_Data_-_Capturing_the_Experience/links/576535af08ae1658e2f48171/The-MPL-Part-II-The-MPL-Data-Capturing-the-Experience.pdf

- Wulf, G., Shea, C., & Lewthwaite, R. (2010). Motor skill learning and performance: A review of influential factors. Medical Education, 44(1), 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03421.x

- Yoon, H., Scopelliti, I., & Morewedge, C. K. (2021). Decision making can be improved through observational learning. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 162, 155–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2020.10.011

- Zimmerman, J. (2006). Why some teachers resist change and what principals can do about it. NASSP Bulletin, 90(3), 238–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192636506291521