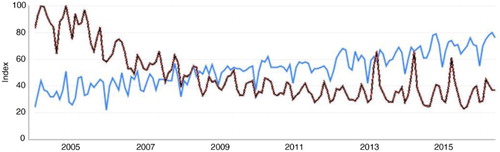

In the early 2000s, a distinct shift occurred in government and public discourse from ‘public participation’ to ‘community engagement’. Our search of Google trends (after Butteriss Citation2014), based on frequencies of keyword searches, shows that worldwide, the term ‘public participation’ is in decline, while ‘community engagement’ is rising ( and ). In 2004 (the first year data are available), the term ‘community engagement’ was searched 40 per cent of the extent to which ‘public participation’ was searched. Apart from two periods in 2013, when search numbers matched, the indicator suggests that interest in community engagement has been firmly in the ascendancy relative to public participation. In April 2016, the worldwide search rate for ‘community engagement’ was double that for public participation. From 2004 to 2016, Australia was the main source of searches for the term ‘community engagement’, with double the rate of South Africa, 2.5 times the rate of Canada and the UK, and treble the rate of USA (though some of these countries have other preferred terms).

Figure 1. Worldwide searches for the terms ‘public participation’ (black, declining) and ‘community engagement’ (blue, rising). Note that the graph shows an index, not absolute numbers. The vertical access shows how often a term is searched, relative to the total number of searches made. The highest point, 100, is a reference point. Source: Google trends, viewed 16 May 2016, https://www.google.com.au/trends/

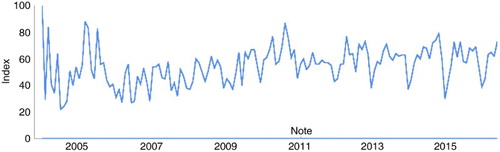

Figure 2. Australia’s searches for the term ‘community engagement’ (blue). Source: Google trends, searched 16 May 2016, https://www.google.com.au/trends/

In Australia, searches for the term ‘public participation’ were negligible, and the term community engagement prevails (South Australia, Queensland, and Victoria were the dominant sources of web searches) (). Data are not available for New Zealand.

This change in preferred terminology is puzzling. Does it signify a new way of thinking and major shift in practice, a difference in contexts (discrete decisions versus more continuous policy development, or the interest in corporate social responsibilityFootnote1 and social licence to operate), or a change in preferred terms for much the same concepts? We suspect all of these. The preeminent international organisation in this field, International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) confirms that it uses the terms ‘public participation’ and ‘community engagement’ interchangeably. It defines public participation as:

a process that involves the public in problem solving or decision making and uses public input to make decisions. It includes all aspects of identifying problems and opportunities, developing alternatives and making decisions. It uses tools and techniques that are common to a number of dispute resolution and communication fields. (IAP2 Citation2010, p. 20).

It also introduces its spectrum of public participation by using both terms:

IAP2’s Public Participation Spectrum is designed to assist with the selection of the level of participation that defines the public's role in any community engagement program. (IAP2 Citation2016)

We note that the organisation has not changed its name, but now calls its newsletter Engagement matters.

Others portray public participation and community engagement as different but related concepts, with engagement as the broader concept. For example, Consult Australia (Citation2015, p. 5) states ‘Engagement is a broad term that can encompass public participation, community, stakeholder or public relations, consultation, government and media relations’.

The requirement for public participation in environmental decision-making emerged with environmental impact assessment (EIA) and social impact assessment (SIA), from 1969 in the USA, 1974 in Australia, and also 1974 (affecting government departments onlyFootnote2) in New Zealand. In planning, it responded to public concerns about poor urban outcomes, including rapid freeway expansion in the USA. Where SIA paralleled EIA in projecting (or monitoring) the impacts of potential developments, public participation, required under environmental legislation, allowed the public a say in key environmental and planning decisions. This came to be recognised as both a matter of natural justice (that affected people should have a voice) and as a source of useful information. Organisations learnt the value of public participation in providing useful information and insights, and reaching greater accord with affected communities. Practice increasingly moved from the limited statutory requirement to allow public comment on proposals immediately before a final decision, to deeper forms of involvement much earlier in the design processes, when plans could be modified with far less difficulty and expense, and proponents could more easily withdraw from the most contentious developments. Theory and practice evolved, particularly in North America where specialists in this field were employed to assist project planners. A body of knowledge was (and continues to be) disseminated through conferences, academic publication, and organisations such as the IAP2.Footnote3 Empowerment of the public through greater involvement is a recurrent theme in this literature. Public participation, however, remains essentially about the rights to participate in another party’s decisions, usually those of powerful organisations (otherwise the requirements for EIA and public participation are not triggered).

Where terminological distinctions are made, ‘community engagement’ tends to be used in a more general way, and often to refer to longer term arrangements. We believe that it responds to a recognition of a need for more initiative to involve the public over longer periods. Community engagement, and the related idea of ‘stakeholder engagement’, was strongly associated internationally with public participation in policy-making (e.g. OECD Citation2001). Head (Citation2007) argues that the shift towards interest in engagement has multiple influences, including international trends in governance in which representative government is seen no longer as sufficient, with demand emerging for shared responsibility for resolving complex issues, and the local politics of managing environmental and other projects.

While public participation originally centred on specific decisions by organisations, particularly industry and government organisations, community engagement is seen as an ongoing, two-way or multi-way process, in which relationships rather than decisions may be focal. Consistent with the IAP2 definition, participants expect to have some influence on the decisions. Community engagement can thus be an ongoing and adaptive process for an organisation to maintain good relations, and ideally learning from and with, the specific communities and general public in which it is interested. It contributed a very significant new idea. Aslin and Brown (Citation2004, p. 5) pointed out that:

Engagement goes further than participation and involvement. It involves capturing people’s attention and focusing their efforts on the matter at hand – the subject means something personally to someone who is engaged and is sufficiently important to demand their attention. Engagement implies commitment to a process which has decisions and resulting actions. So it is possible that people may be consulted, participate and even be involved, but not be engaged.

This idea has important implications as we observe the process of communities (and their individual members and leaders) engaging themselves in issues, from running and belonging to action-oriented voluntary organisations (Landcare to green activism), advocating for more public transport and bike paths, to campaigning against developments of concern, or for greater action on climate change mitigation. Thus, in community engagement, communities may be initiators and collaborators, not limited to responding to externally proposed developments and plans, or major organisations’ public relations aspirations and desires for ‘social licence to operate’. IAP2 (Citation2015, p. 12) argues that:

Perhaps the most significant shift in thinking about community engagement has come with recognition that the engagement may now be motivated from within the community or even led by the community itself rather than the one-way path from government or organisation to community.

Other than these distinctions, there appear to be few differentiations in theory, again suggesting closeness between the concepts. Models of participation and engagement have evolved, partly to overcome the linearity of popular ‘ladder’ images (Arnstein Citation1969; Wondolleck et al. Citation1996) as well as to encapsulate other notions (Ross et al. Citation2002). Wheels of engagement based on Davidson’s (Citation1998) ‘wheel of empowerment’ (also labelled participation) relate different approaches to the main entries on IAP2’s spectrum, without substantial elaboration of the key ideas.

Engaged communities, in the sense intended by Aslin and Brown, clearly tend to benefit the environment. Engaged citizens and communities are active agents, often taking their own initiatives to protect environments, whether through advocacy or practical action. As we see in current campaigns about the export of coal, expansion of ports and dredging in relation to the Great Barrier Reef, the locus of decision-making can shift from the corporate driven (project proponents) and regulatory process, to public ability to stymie developments through political and financial suasion, particularly mobilising through social media and influencing investors. This type of public-led ‘engagement’ relates to what Head (Citation2007) refers to as a ‘democratic deficit’, between democratic ideals and managerial realities. It is far from new. The Audubon Society in the USA, founded in 1905, is credited with much influence over wildlife conservation. In Australia, protected areas including the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, and Moreton Bay Marine Park, originated from public concern and campaigning. In New Zealand, campaigns have assisted in the recognition and protection of the Fiordland. Climate action is another example of an active citizenry engaged with an issue, while not being well heard in the governance process. A highly engaged public has been involved in practical environmental stewardship through Australia’s and New Zealand’s Landcare and many other groups since the early 1990s. One would also consider individual landholders who commit to strong environmental stewardship on their land as ‘engaged’.

As the articles in this issue suggest, there are many more dimensions to public participation and community engagement than the explanations of these ideas usually convey. The variants go well beyond focus on particular environmental decisions or plans, or the relationships of particular organisations with their beneficiaries and critics. They can be formal or informal, and can be initiated by members of the public.

We cannot rely on formally arranged community engagement processes alone to guide environmental policy and management. That route can certainly improve dialogue and mutual understanding, even stimulate co-learning and co-production of new directions (Bovaird Citation2007). However, it does not guarantee sufficient focus on the range of important problems, or necessarily the inclusion of all of the interests. We very much need well-judged long- and shorter-term public participation processes to bring the public equitably into environmental direction-setting, early and with respect for their contributions. Otherwise there is a risk of community engagement programs becoming more focused on maintaining specific relationships, rather than on the broader questions of what those relationships need to be about in the interests of sustainable futures. We also need an alert and engaged public that takes the initiative to fill the gaps in formal processes, and so helps to look after the planet.

Articles in this issue

Examples of our discussion of public participation and community engagement illustrate the complexity of these fields. Leonie Lockstone-Binney, Paul Whitelaw, and Wayne Lockstone-Binney examine the experiences of members of Victoria’s voluntary committees that manage crown lands reserves across that state, under a delegated system of management. Some 8000 voluntary committee members are responsible both for decision-making and on-ground works. Their main motivations for this service are improvements for their communities, a family legacy of such volunteering, representing particular user groups such as sporting clubs, and opportunities for social interaction. While clubs provide a source of much-needed members for these committees, there is potential for role conflict. The committees suffered problems noted frequently in the literature on volunteering, such as issues of recruitment and retention, especially in declining communities, and burnout and feeling trapped in the roles. This situation reminds that high levels of community involvement can come at a cost (as well as benefits) to those at the forefront of the responsibility and role.

Methods for public participation or community engagement abound, and are regularly improved. Zhifang Wu, Ganesh Keremane, and Jennifer McKay show how an elaboration of the visual elicitation process of ‘photostory’ (an elaboration of photovoice) can be used to provide deep understanding of people’s engagement with urban water, including how water saving and sustainable water management are rationalised and how they can become shared experiences. While there are practical limitations to the numbers of people who can participate, the method was effective in eliciting in-depth information, and stimulating participants’ understandings of the implications of their actions.

Kathleen Mackie and David Meacheam conducted a policy analysis of the establishment of Australia’s widely regarded Working on Country program which serves environmental and employment goals. Excellent stakeholder engagement was one factor in the program success, alongside extended dialogue among departments in developing and ‘road testing’ the concept, and making the environmental management aims ostensibly secondary to the employment aims. They comment that by September 2013, nearly 700 rangers in 90 projects cared for 1.5 million km2 of land (2016 figures are 777 full-time equivalent ranger positions, in 109 projects, Australian Government Citation2016).

Choice modelling experiments are one of the sources of information about public preferences for certain policy options. Here Jim Sinner, Brian Bell, Yvonne Phillips, Michael Yap, and Chris Batstone take a different stance to the usual reporting of methodology or results, to explore the value of choice modelling in communicating public preferences to decision-makers. In a New Zealand case about freshwater management, they argue that if choice experiments are to inform management decisions in contested policy contexts, they need to be more closely integrated into the stakeholder engagement process. This is important given the increasing use of collaborative decision-making for natural resource management, and the need for evidence to inform these participatory processes.

Another aspect of engagement with the public – and the public taking an interest in the performance of public authorities – is reporting of environmental performance information. Grainne Oates and Amir Moradi-Motlagh examined the rates of disclosure of environmental performance by Victorian local governments, using the criteria of the well-accepted Global Reporting Initiative. They found that the level of reporting was very low. The level of disclosure is related to underlying environmental performance, an issue which may give concern to the interested public.

This set of articles illustrates some of the potential breadth of concerns in contemporary ‘community engagement’. At one extreme, institutions exist for direct and longstanding public participation (by engaged community members) in the mainstream of managing government-owned land. At the other, governments need to consider systematically disclosing their performance in environmental management, before an ever-watchful public. Meanwhile, social and economic research methods are valuable in exploring and reporting the ways in which members of the public think about issues. These can provide evidence in stakeholder decision processes, but it is important to ensure the evidence is suitably packaged, and integrated well into the deliberative process. The creation of good policy relies on far more than inclusive stakeholder participation; however, the process within government is also important.

Turning to another topic, Chirag Mehta, Robyn Tucker, Glenn Poad, Rod Davis, Eugene McGahan, Justin Galloway, Michael O’Keefe, Rachel Trigger, and Damien Batstone point out that while Australia is a net food exporter, it achieves this by relying heavily on imported fertilisers to provide nutrients for agriculture. Their assessment of opportunities to recycle nutrients from agricultural and industrial residues showed that in principle, 23 per cent of the needs for nitrogen and phosphorus, and all of the need for potassium, could be met from waste streams. Sources in intensive livestock production, mining and electricity-generation are also available within a 200 km radius of grain growing regions. The best sources of nutrients were intensive livestock facilities. Uses of these resources are not currently economic, but increasing regulation of the disposal of organic wastes, rises in fertiliser prices, and more cost-effective recovery technologies could render these sources more attractive in future.

Editors’ tip

This tip continues the advice of our March editorial, to help those accustomed to writing technical reports to write in journal style. It assumes you have a new contribution to knowledge (see editors tip, editorial of December 2012) and there are no contractual obstacles to your publishing work conducted through consultancy or in public service roles.

Study published journal articles in your field, and observe the stylistic differences from a report. Note differences between an abstract, and an executive summary. See how the structure of the article typically begins with an introduction which is also a literature review, placing your work in the context of existing knowledge. The extent of referencing used is important. A journal article tends to have fewer headings than a report, and generous paragraphs, each containing a complete ‘thought’ (i.e. paragraphs are not broken artificially after reaching a few lines in length).

Choose a journal before beginning writing. You need to be certain your work fits within the scope of the chosen journal. Other criteria are reaching the readership you seek, the status of the journal, and the opportunity to follow related work (see editors tip, editorial of March 2011).

Conduct a thorough literature review, systematically searching for the key, and especially recent, works in your field (see editors’ tips, June 2011 and June 2012). Your aim is to summarise, and introduce readers to, existing knowledge in the field, showing the gap in knowledge that your work will now fill. At the same time, you demonstrate your knowledge of the field. You should rely on refereed literature (i.e. journal articles, books and book chapters) and make only sparing use of non-refereed works such as reports where essential to acknowledge content. Ideally, you should ask a library’s help to do systematic searches on databases, using keywords (Google Scholar is a free substitute, but has limitations). You may introduce the purpose of the article at the end of the introduction.

If yours was a practical study, explain the methods in sufficient detail for readers to assess the rigour of the work (see editors’ tip, March 2012).

Write your body, discussion and conclusions towards making a new contribution to knowledge. You do not need to report every aspect of a complex study; it is better to assemble your evidence and argue your case towards a conclusion that presents your key message or contribution to environmental management. Your discussion will relate the results of your work to the literature, showing where your results agree or disagree with, and in particular add to, existing knowledge. We give tips on conclusions in our September 2012 editorial.

Check that the abstract, introduction, evidence and conclusions are aligned towards a clear argument (see editor’s tip, September 2011). The abstract is subtly different from a summary. An abstract usually includes the rationale for the study, the methods, and key learnings, and stimulates your potential readers to study the article. Check that your referencing follows the journal’s format.

Seek advice from experienced authors of journal articles, and consider co-authoring with one to obtain the benefit of their skills.

Having submitted, do not be dismayed if your work requires substantial revision after its first round of peer review. That is extremely common, indeed very few articles are accepted without minor to major revisions. If the substance of your content is valuable, you may be asked to revise and resubmit.

Notes

1. Search trends on this term dominate over community engagement, worldwide and in Australia, but it has been in relative decline since 2008.

2. The widespread adoption of EIA in New Zealand is attributed to the Resource Management Act 1991, but specific EIAs were conducted from at least the 1970s.

3. This body of knowledge is summarised by Reed (Citation2008).

References

- Arnstein, SR 1969, ‘A ladder of citizen participation’, Journal of the American Institute of Planners, vol. 35, pp. 216–224. doi: 10.1080/01944366908977225

- Aslin, HJ & Brown, VA 2004, Towards whole of community engagement: A practical toolkit, Murray-Darling Basin Commission, Canberra.

- Australian Government Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2016, Indigenous rangers: working on Country, viewed 15 May 2016 <http://www.dpmc.gov.au/indigenous-affairs/environment/indigenous-rangers-working-country>.

- Bovaird, T 2007, ‘Beyond engagement and participation: user and community coproduction of public services’, Public Administration Review, vol. 67, 5, online. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00773.x

- Butteriss, C 2014, ‘Civic engagement versus community engagement’, Bang the table: all about engagement, viewed 14 May 2016, <http://bangthetable.com/2014/11/18/community-engagement-vs-civic-engagement-vs-public-involvement/>.

- Consult Australia, 2015, Valuing Better Engagement: an economic framework to quantify the value of stakeholder engagement for infrastructure delivery, Consult Australia, <http://www.iap2.org.au/resource-bank/command/download_file/id/243/filename/valuing-better-engagement-economic-framework.pdf>.

- Davidson, S 1998, ‘Spinning the wheel of empowerment’, Planning, vol. 1262, pp. 14–15.

- Head, B 2007, ‘Community engagement: participation on whose terms?’ Australian Journal of Political Science, vol. 42, pp. 441–454. doi: 10.1080/10361140701513570

- International Association for Public Participation (IAP2), 2010, Public participation: state of the practice, Australasia, IAP2, viewed 18 May 2016, <http://www.iap2.org.au/resource-bank/area?command=record&id=174>.

- International Association for Public Participation (IAP2), 2015, Quality assurance standard for community and stakeholder engagement, IAP2, viewed 15 May 2016, <http://www.iap2.org.au/resources/quality-assurance-standard>.

- International Association for Public Participation (IAP2), 2016, The IAP2 public participation spectrum, viewed 18 May 2016, <http://www.iap2.org.au/resources/public-participation-spectrum>.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development), 2001, Citizens as partners: OECD handbook on information, consultation and public participation in policy-making, OECD, <http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/citizens-as-partners_9789264195561-en>.

- Reed, MS 2008, ‘Stakeholder participation for environmental management: a literature review’, Biological Conservation, vol. 141, pp. 2417–2431. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2008.07.014

- Ross, H, Buchy, M & Proctor, W 2002, ‘Laying down the ladder: a typology of public participation in Australian natural resource management’, Australian Journal of Environmental Management, vol. 9, 4, pp. 205–217. doi: 10.1080/14486563.2002.10648561

- Wondolleck, JM, Manring, JA & Crowfoot, JE 1996, ‘Teetering at the top of the ladder: the experience of citizen group participants in alternative dispute resolution processes’, Sociological Perspectives, vol. 39, pp. 249–262. doi: 10.2307/1389311