ABSTRACT

Predator Free 2050 (PF2050) is an ambitious goal that aims to remove three types of invasive mammals from New Zealand by 2050. It will require a significant amount of funding, research, and support. Young adults will have an important role to play for this programme to be successful. Therefore, understanding the awareness and attitudes of young adults towards PF2050, and predator control, is an essential consideration. A survey of 1479 18- to 24-year-olds was conducted in 2017. The results showed that a higher percentage of young adults than members of the broader public view the small, introduced mammals as threats to New Zealand’s environment. Furthermore, this study highlights support for the control of feral, stray, and domestic cats. More focused research on attitudes towards cats is recommended to gauge which control methods are approved of by young adults. Indeed, methods appear to be a key factor to young adults supporting PF2050. The aerial distribution of poison was largely viewed negatively, and moderate concern was expressed about the targeted animal’s welfare. Interestingly, young adults appeared to be open to the use of gene editing and gene drive, although they expressed caution. Targeted communication towards young adults on toxins and genetic methods is recommended.

Introduction

Invasive species – introduced species that rapidly spread and cause harm to their new environment – have been found to threaten global biodiversity by preying on native species, competing with native species for resources, modifying habitats, and introducing new pathogens to ecosystems (Bergstrom et al. Citation2009; Clavero and García-Berthou Citation2005; Crowl et al. Citation2008; Harvey-Samuel, Ant, and Alphey Citation2017). Thus, the management of introduced species is an important component of many conservation efforts throughout the world. In New Zealand, invasive species have had significant ecological, economical, and social impacts, and invasive species management is an integral part of national conservation and biosecurity policy (Russell Citation2014). This management includes the control and eradication of populations of introduced mammals.

However, environmental management of any kind does not exist in isolation from society, and the removal of animals or the targeting of a specific species can elicit strong reactions from citizens. In fact, such programs can be very difficult to implement without social support and the public may object if it involves the use of their land, or if they view the eradication as unnecessary or inhumane (Bertolino and Genovesi Citation2003; Harper, Pahor, and Birch Citation2020; Parkes et al. Citation2017). For example, in 1997 in Italy, an animal rights group took the National Wildlife Institute to court to halt their action plan to eradicate the American grey squirrel. This legal action caused a suspension of the project for three years, by which time eradication was no longer feasible (Bertolino and Genovesi Citation2003). Conversely in 2015, in the Canary Islands, complaints from landowners drove an attempt to eradicate ring-necked parakeets. The successful eradication of this population was one of the few in the world to be achieved without social conflict (Saavedra and Medina Citation2020). Unless the public is willing to support efforts to achieve the conservation aims, eradication efforts can be openly opposed, which can undermine the likelihood of success (Ogden and Gilbert Citation2011). Yet invasive species research that incorporates social dimensions is scarce (Estéves et al. Citation2015; Schüttler, Rozzi, and Jax Citation2011).

In 2016, New Zealand’s Predator Free 2050 programme (PF2050) was announced, which outlines the government's plans to remove possums, mustelids, and rats from the entire country by 2050. The announcement of the programme received mixed responses. While it obtained large ‘in principle’ public support, it has also been described as overambitious and underfunded (Linklater Citation2017). Various social issues could arise as a result of the work under the PF2050 banner, including objections to the use of toxins, which have been raised before (Hansford Citation2009). The pesticide, sodium fluoroacetate, or 1080, has been used in New Zealand since the 1950s to control introduced mammals (PCE Citation2007). However, protests against its use have been ongoing since the early 2000s (Hubbard Citation2015; Jolliff Citation2017; Nicoll Citation2016). As well as general concern about the poison, opponents often express concern for its aerial distribution. Reasons include the indiscriminative destination of the poison in the environment, the risks to livestock, large feral mammals used for hunting, and domestic dogs, the risk of bycatch, ethical concerns, the perceived risks to human health, and a general antipathy towards poisons for pest control (Chand and Cridge Citation2020; Eason et al. Citation2010; Green and Rohan Citation2012; Hansford Citation2009).

Because the ongoing use of 1080 remains highly contentious, the announcement of PF2050 brought a renewed interest in developing novel tools to eradicate invasive animal species (Dearden et al. Citation2018; Gemmell et al. Citation2013; PCE Citation2007; Warburton et al. Citation2022). Several different options for gene technology are currently being developed for predator control (MacDonald et al. Citation2022). The research has not been without its fair share of controversy in the media, both nationally and internationally. In December 2017, this method made headlines around New Zealand (Fisher Citation2017; One News Now Citation2017; In the News Citation2017). Although it may be years to decades before this method is technologically, if not socially, practical, public acceptance of these techniques will be essential so a significant amount of social science research has been conducted over the last six years to elicit the attitudes of the broad public to PF2050 and novel pest control methods (Esvelt and Gemmell Citation2017; Kirk et al. Citation2020; MacDonald et al. Citation2020; Murphy et al. Citation2019; Russell, Taylor, and Aley Citation2018; Tompkins Citation2018; Warburton et al. Citation2022). From research published in 2019, Kirk et al. identified several themes as to why New Zealanders did or did not support these novel technologies. While some New Zealanders were concerned about the risk of unintended consequences, others discussed the benefits, such as a preference for non-toxic control methods, the chance to be an early adopter of these technologies, and the opportunity to move away from the aerial distribution of poisons.

Social acceptability is thus crucial for eradication success. Furthermore, it is critical to include and engage young people. This is the group that will inherit the consequences of decisions made today (and who stand to be most impacted by ongoing global change) (Devenport et al. Citation2021; Thomas et al. Citation2021). This study focuses on a sub-population of the public in New Zealand – young people aged 18–24 years old at the time of the survey. With a timeline of around 30 years, this sub-population is also likely one of the key groups that will see PF2050 through to fruition. Thus, understanding their attitudes towards the goal is important. Importantly, a review conducted on attitudes to pest control in New Zealand in 2017 highlighted that there was a need to understand the attitudes of young adults (Kannemeyer Citation2017). Several key themes emerged in the results of this study, namely the respondents’ attitudes towards cats, animal welfare, and controversial predator control methods.

Methods

The methodology used for this research was an online survey. This was deemed the most practical way of collecting data from a high number of participants. Similar surveys on attitudes towards pest control were distributed to the public in 2010, 2012, 2013, and 2017 (Farnworth, Campbell, and Adams Citation2011, Citation2014; MacDonald et al. Citation2020; Russell Citation2014), however, none specifically targeted young people.

The survey was designed for three key purposes. Firstly, it sought to explore the attitudes of this demographic towards introduced mammals in general, through questions such as how much of a threat to the environment respondents thought different introduced species were and how they thought different introduced species should be managed. Secondly, it sought answers on the awareness and attitude towards PF2050 specifically. Respondents were asked if they had heard of the goal, what they thought of it, how likely they were to get involved with predator control, and about their attitudes towards different predator control methods. Thirdly, it explored attitudes towards introduced mammals that were not included in the goal but are the focus of other predator control campaigns. Standard demographic information was also gathered. Through testing, the survey was estimated to take 10 minutes to complete. For the full survey, please refer to the supplementary material.

During the design phase, existing surveys were reviewed. These included the ‘Public Perception of New Zealand’s Environment’ (Hughey, Kerr, and Cullen Citation2016) survey, run by Lincoln University on a triennial cycle, and Russell’s ‘A Comparison of Attitudes Towards Introduced Wildlife in New Zealand in 1994 and 2012’ (Russell Citation2014). Questions 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 in this survey were taken with permission from the latter. This provided a good comparison for how perception might have changed in the last five years, and how the views of young adults may differ from those of the broader population. The survey was administered using the software Qualtrics – an easy-to-use and industry standard platform that sets up web-based surveys.

The participants in this research were recruited in the following three ways:

Targeted: The survey was emailed to systematically selected organisations throughout New Zealand. These institutes were selected as they cater to young adults and are not associated with New Zealand conservation or ecology.

All 73 tertiary institutes in New Zealand were contacted with the survey and asked to both pass it on to their students and post it on their social media sites. This was done either by emailing the student unions of the institute or, if the institute did not have a student union, directly emailing the institute. They were emailed on June 1st, 2017, and again on June 14th.

Large social sports centres throughout New Zealand were emailed and asked to pass the survey on to their members and post it on their social media sites. These 43 centres were selected as they came up in a Google map search of social sports centres in a particular city. All cities in New Zealand were searched. The list of these centres was reviewed, and, in some cases, certain ones were removed if they did not contain any contact details or were not actually social sport centres. The social sports centres were emailed on June 1st and then again on June 14th.

Twelve lecturers, three each from the University of Auckland, Victoria University of Wellington, the University of Canterbury, and the University of Otago, were emailed and asked to display the survey on their course internal website. These four universities were selected as they are the largest in New Zealand and the lecturers came from a range of faculties, i.e. arts, sciences, law, and commerce. The lecturers were selected if they ran large, 100 level papers that were not associated with environmental science to avoid sampling bias. The lecturers were emailed on July 3rd to correspond with the beginning of semester 2. A follow up email was sent on August 9th to those who had not responded to the initial email.

The student services of all eight New Zealand universities were contacted and asked to email the survey out directly to their student body. If the student services could not be located on the webpage of the university, then the university was emailed directly, with the assumption that this email would get through to these services. For the University of Otago, this was on August 7th. The other universities were emailed on August 16th.

Email snowball: Once the participants completed their survey, they were invited to pass it on to other people they knew in the correct demographic.

Social media snowball: The survey was shared on Facebook and participants were asked to share it on their social media pages. Again, this method of sampling was used as a way of reaching participants outside of tertiary institutes.

The survey was open from 1st June 2017 to 24th August 2017 and received 1,589 responses, of which 1,479 were from the target demographic.

The demographics of the respondents were requested but these questions were optional. However, they are suggestive of the responding population. Of the people who answered this section, 62 per cent were female, 37 per cent male, and one per cent identified as other. Seventy one point six per cent of the respondents were New Zealand European, 9.6 per cent were Asian, 3.7 per cent were Māori, 1.7 per cent were Pacific Islanders, and 12.9 per cent ticked the box ‘other’. Most of the respondents – 79.8 per cent – lived in a town or city of more than 30,000 people.

As with many surveys, this one contains biases in the demographics of the respondents. The March 2018 census of the total New Zealand population showed that 49.4 per cent of people identified as female, compared to 62.3 per cent who answered that question is this survey (Statistics New Zealand Citation2018). This survey also underrepresents Māori views. The 2018 census indicated that 16 per cent of the total New Zealand population are Māori, compared to 3.7 per cent in this survey (Statistics New Zealand Citation2018). Therefore, the results of this survey are likely to be skewed towards certain subgroups. Furthermore, as the survey was distributed largely via tertiary institutes a disproportionate number of respondents were likely to be tertiary students in urban areas. The survey was only administered online, which limited sampling to people with Internet access. Similar surveys that target subgroups within this subpopulation may well yield slightly different results. Still, the current study, with a reasonably large response rate, provides a useful and important snapshot currently not available elsewhere.

To obtain further insights into the respondents’ views and attitudes, an optional, open-ended comment box was provided at the end of the survey. Two hundred and seventy seven respondents left comments, varying in length from a few words to whole paragraphs. 241 of these comments were related to PF2050 or issues surrounding predator control. These were analysed to identify themes. A comment could have more than one theme. The percentage of respondents who left comments that discussed each theme was also established. The qualitative findings are presented alongside results from thematically related survey questions.

Results

Attitudes towards introduced mammals and predator control in New Zealand

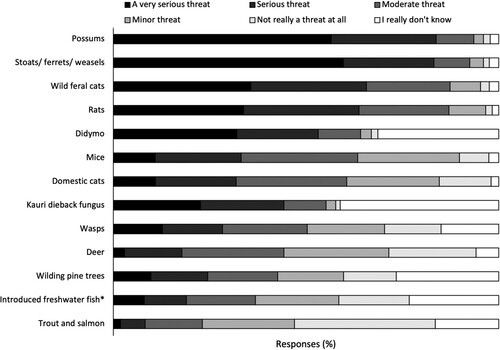

Mammals were more commonly seen as a threat than non-mammals towards New Zealand’s native plants, birds, animals, or natural environment. The most common species identified as threats were possums, mustelids (stoats, weasels, and ferrets), feral cats and rats. As shown in , the combination of the top three threat levels (very serious threats, serious threats, or moderate threats) showed 93.5 per cent of respondents view possums to be a threat, with 92.5 per cent for mustelids, 87.4 per cent for wild feral cats, 87.1 per cent for rats, 64.1 per cent for didymo, 63.4 per cent for mice and 60.6 per cent for domestic cats.

Figure 1. The perceived threat level of selected exotic species currently present in New Zealand.

Note: Respondents were asked to select one of six answers to the following question: ‘The following is a list of species that have been introduced to New Zealand. Based on what you have seen or heard, to what extent do you believe each is a threat to New Zealand's native plants, birds, animals or natural environment?’ Sample size: 1479.*Such as koi carp and catfish but excluding trout and salmon.

To discern how young adults valued different animals, respondents were asked whether they saw certain animals as pests, resources, or both pests and resources. Most respondents viewed possums, mustelids, rodents, and feral cats as pests only (78.5 per cent, 89.2 per cent, 88.1 per cent, and 87.0 per cent respectively). This was also the case for hares, rabbits, and wasps (64.3 per cent, 59.3 per cent and 63.7 per cent respectively). In contrast, larger mammals generated a range of opinions. Most respondents did not know how to classify thar or chamois. Feral goats and feral pigs were largely viewed as a resource (57.4 per cent for goats and 56.9 per cent for pigs) and deer was split between a resource (49.8 per cent) and both a pest and a resource (40.2 per cent).

This was emphasised by some respondents in the comment section of the survey. Nineteen respondents (7.9 per cent of those who left comments) discussed the link that these mammals had with the hunting industry. For example:

Deer, goats, pigs, tahr, chamois are all good for hunting as a recreational sport, however farmers need to control numbers on their property and not let them breed excessively.

We'd be better off promoting game parks in sections of bush and alpine areas for the larger herbivores to be hunted for money, this could potentially encourage more jobs in the remote areas.

In the comment section, respondents often stressed how much they valued the New Zealand environment and the native fauna and how they hoped PF2050 would be successful for this reason. For example:

I think [PF2050] is a very admirable goal, and I would love for our currently endangered native species to live in the wild in larger numbers than they do now.

Predator 2050 [sic] is a terrific initiative to get rid of introduced predators once and for all. For decades we've been exhausting resources on manual trapping and poisoning but it's failing because our wildlife numbers just keep going down.

Attitudes towards predator control methods

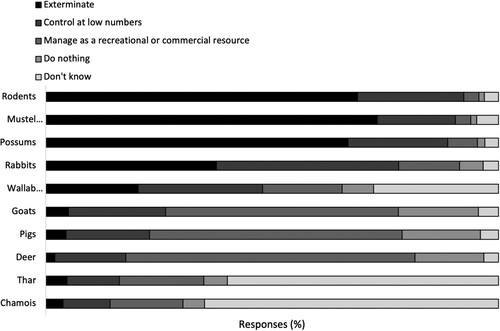

Most participants viewed the smaller introduced mammals as pests, and this was reflected in their views on how introduced mammals should be controlled. Ninety two point four per cent of respondents believed that rodents should be ‘exterminated’ or ‘controlled at low numbers’, 90.5 per cent for mustelids, 88.8 per cent for possums and 78.0 per cent for rabbits. Once again, herbivores were largely seen as resources rather than pests (see ). A high proportion of respondents did not know thar and chamois should be managed, but this was hardly a surprise as they also did not know how to classify either of these species.

Figure 2. Views on the appropriate form of management for selected introduced mammals currently present in New Zealand

Notes: Respondents were asked to select one of five answers in response to the following question: ‘In your opinion, what sort of management is most appropriate for the following species of wild animal? (tick one box for each species).’ Sample size: 1479.

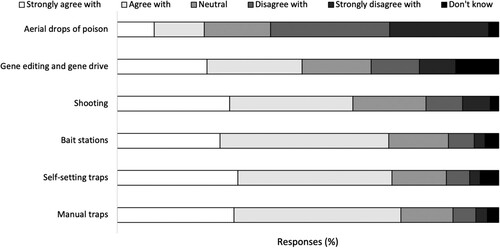

Participants were more divided when it came to the methods that should be used to achieve PF2050. As shown in , physical forms of control were viewed favourably, such as traps (74.4 per cent for manual traps and 72.1 per cent for self-setting traps), bait stations (71.2 per cent) and shooting (61.3 per cent). In contrast, aerial drops of poison were viewed less favourably, with 22.8 per cent agreeing with its use (57.1 per cent did not agree with it). The view towards gene editing was particularly interesting, with a strong ‘in principle’ support (48.5 per cent supportive, 18.1 per cent neutral, 22.2 per cent opposing and 11.3 per cent ‘did not know’).

Figure 3. The attitudes towards different types of predator control.

Note: Respondents were requested to select one of six responses to the following statement for each of the six predator control methods given: ‘Please tick the following predator control methods that you agree with.’ Sample size: 1479.

The use of poison came up several times in the comment section, with a small number of respondents being in favour of it, but by far the majority being against it. Issues surrounding animal welfare, the possibility of poison getting into the waterways, and the potential for bycatch were the most common reasons given.

TWelve comments specifically mentioned ‘gene’ and a few more (6), while not specifically mentioning ‘gene’, discussed predator control methods in such a way that their attitude towards genetic technology was implied. This technology was generally discussed with caution. Some respondents stated concern over the premise of manipulating genes while others acknowledged its potential but emphasised the need for further research. For example:

In my opinion, gene drive seems the only viable way to become ‘predator-free’ by 2050 – this method requires a lot more research to ensure it won’t create more extinct species (e.g. possums in Australia after someone decides to protest against use of GMOs).

It is extremely important that we focus on using novel pest control methods that take into account each animal’s intrinsic value and welfare. Such methods are usually considered much more effective, despite being controversial.

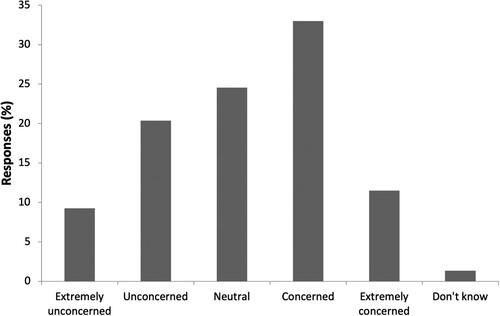

Many participants were concerned about the target animal’s welfare during predator control campaigns, with 44.5 per cent expressing some concern over this, compared to 29.7 per cent who were unconcerned (see ).

Figure 4. The level of concern respondents had for the target animal’s welfare.

Note: Respondents were asked to select one of six answers to the following statement: ‘On the scale below, please mark how concerned you are about the targeted animal's welfare during predator control.’ Sample size: 1479.

Animal welfare was one of the most persistent topics in the comments – in total, 64 out of the 241 comments (26.6 per cent) mentioned animal welfare in some capacity. For example:

I support getting rid of predators that are a threat to native NZ wildlife and plants, I do not support any cruelty of (sic) the animals in the process of extermination or control.

I think that predation needs to be addressed regardless of the cost. Even if methods aren't that humane, they are a lot more humane than the pests are to our endangered flora/fauna.

Attitudes towards cats and rabbits

Additional questions about feral cat and rabbit management were included. Although these mammals are not part of the official scope of PF2050, they are part of other predator control campaigns. An assessment of how young adults feel about these methods could shed light on how they feel about predator control in general.

Cats were heavily discussed by young adults throughout the survey. Overall, participants thought wild feral cats were worse than rats in terms of threat, and, consistent with other research, they expressed support for the control of feral cats (Russell Citation2014; Russell et al. Citation2015). Interestingly, domestic cats were viewed as only slightly better than mice.

Thirty five out of the 241 (14.5 per cent) comments left in the survey mentioned cats. Seventeen of these comments mentioned stray or feral cats and 17 mentioned domestic cats. These comments were categorised based on whether they were positive (i.e. respondents agreed with controlling cats due to their environmental impact), negative (i.e. respondents were concerned about controlling cats), both, or neither. Forty three per cent (15) of the comments were categorised as positive (of these eight specifically mentioned feral or stray cats and six mentioned domestic cats), 37 per cent (13) were categorised as negative (of these six specifically mentioned feral or stray cats and eight domestic cats), 14 per cent (5) as other, and six per cent (2) as both (domestic cats only).

When it came to domestic cats, respondents were concerned about their pet cat being affected by certain predator control methods or being mistaken for a stray or feral cat, or stated that there needed to be greater restrictions on domestic cats. Neutering, mandatory collars, and microchips were suggested as ways this could be implemented. Examples include:

Very concerned about issues surrounding cat populations. Media and government discussion about culling cat populations breeds public hatred towards all cats including domestic pets. I personally know many instances of my own or friends' domestic cats being abused or killed due to this. It is an outrage.

I think that it is important to try our best to eradicate these pests, including the public taking precautions with mammals that are their pets, such as making sure domestic cats are either kept inside full time or wear a collar with bell so they are less of a danger to native birds.

Neutering feral and stray cats will not stop them eating our wildlife.

I am very much for pest control as long as the well being of the pest is taken into consideration and that is humane and safe. I am also very strongly against the killing of feral or stray cats. Trap-neuter-release has been proven to work to control and eriadicate [sic] these communities of cats without harming or hurting them in the process.

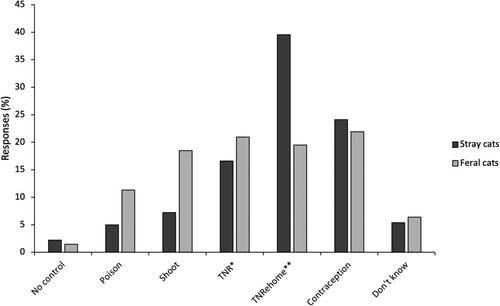

Figure 5. The management deemed most appropriate for stray and feral cats.

Note: Respondents could select more than one response as they were asked to tick all that applied. The question was framed as follows: ‘There are large populations of both feral (rural dwelling) and stray (urban dwelling) cats living in New Zealand. How do you think these cats should be controlled to reduce their impact on wildlife?’ Sample size: 1479.*Trap-neuter-release **Trapneuter-rehome.

In terms of stray cats, trap-neuter-rehome was the most popular option, followed by contraception, and trap-neuter-release. For feral cats, contraception was the most popular form of control, followed by trap-neuter-release, trap-neuter-rehome and shooting. Neither ‘Poison’ nor ‘No control’ were accepted approaches for managing feral and stray cats.

Respondents were not given specific details about the method that would be used to control feral rabbits. However, they were asked how likely they would be to support their control overall. Seventy four point two per cent of respondents indicated they support the control of feral rabbits and only 8.4 per cent opposed the idea.

One common method of controlling feral rabbits is biocontrol (to release a variant of rabbit calicivirus). The origin strain of calicivirus was released into New Zealand illegally in 1997. A new strain was released into Canterbury in early 2018 through approval from the Ministry of Primary Industries. Respondents were asked if they would still support the control of feral rabbits if it meant that domestic rabbits would need to be vaccinated. This scenario led to 21.6 per cent expressing lower levels of support for rabbit control while 9.6 per cent increased their level of support; 68.9 per cent of respondents did not change their answer. Although specific details of this kind of control were not given in the survey, some respondents did express concern about the use of biocontrol in the comment section.

Discussion

Attitudes towards introduced mammals and predator control in New Zealand

In 2022, a survey conducted of the broader public found 35 per cent of them were aware of PF2050 (Fresh Perspective>Insight Citation2022), similar to the 37.5 per cent of young adults found in this study. Thus, like the wider public, young adults have moderate awareness levels of PF2050 (around one out of three have heard of the goal) (Fresh Perspective>Insight Citation2022). However, even young adults who have not heard of PF2050 place value on New Zealand’s environment and are, in theory, supportive of efforts to protect this environment. This finding aligns with other research, which has found that New Zealanders have a well-established identity as an environmentally focused nation (MacDonald et al. Citation2020; Russell et al. Citation2015). Having an interested public who are supportive of the outcome of PF2050 will be useful for achieving such a momentous task.

A high percentage of young adults identified the following introduced mammals as at least a moderate threat to New Zealand’s native plants, birds, animals, or natural environment – possums (93.5 per cent), mustelids (92.5 per cent), wild feral cats (87.4 per cent), rats (87.1 per cent), mice (63.4 per cent), and domestic cats (60.6 per cent). These mammals are often the focus of predator control initiatives, such as the Department of Conservation’s Tiakina Ngā Manu (formally ‘Battle for our Birds’), the Capital Kiwi Project, which aims to bring kiwi back to Wellington, and the Green Party’s Conservation Policy. Indeed, a strong anti-possum rhetoric has been identified in New Zealand (Potts Citation2009). Publicity concerning the impact introduced predators have on New Zealand’s native environment has been widespread, and the results from this survey may highlight that this communication has been effective with young adults. In contrast, in 2022, when the wider public was surveyed, the most damaging predators to New Zealand’s native species were identified as possums (64 per cent), mustelids (60 per cent), and rats (58 per cent) (Fresh Perspective>Insight Citation2022). Feral cats were at 42 per cent and domestic cats at 22 per cent (Fresh Perspective>Insight Citation2022). These percentages are lower than the findings from this study and suggest that young adults are more concerned about the damage that introduced mammals cause to New Zealand’s native environment than the wider public.

Interestingly, young adults did not differ hugely from the wider public in their attitudes to the same introduced mammals when considering them either a pest or a resource. In 2012, a survey of the New Zealand public found that 80 per cent of them ranked possums as pests rather than resources (or pests and resources) (Russell Citation2014). Cats were ranked as pests by 93.3 per cent of respondents, mustelids by 88.4 per cent, and rodents by 96.1 per cent. Young adults were similar to this with possums viewed as pests by 78.5 per cent of respondents, cats by 87 per cent, mustelids by 89.2 per cent, and rodents by 88 per cent. However, this shift seems to have occurred with the wider pubic, rather than young adults who, as a group, still strongly see these introduced mammals as pests and threats to New Zealand’s native environment.

Attitudes towards cats

Cats are another introduced predator that have significant negative impacts on native animals (Farnworth, Dye, and Keown Citation2010), but they are also pets and many New Zealanders see them as companions. In fact, a report in 2011 found that New Zealand had the highest rate of households with a cat in the world (NZCAC Citation2011). The perception of domestic cats was interesting and unexpected, with 60.6 per cent of respondents identifying them as at least a moderate threat. In comparison, a 2022 study of the wider public found that only 22 per cent saw domestic cats as one of the most damaging predators for New Zealand’s native species (Fresh Perspective>Insight Citation2022). Domestic cats are estimated to kill between five and 11 million birds annually (PCE Citation2007). Participants who discussed this issue in the qualitative comments often thought that domestic cats required a greater level of control, suggesting compulsory neutering and a breeders’ licence.

This view that young adults have towards cats may reflect the increased publicity that has surrounded cats as predators in the half decade prior to this survey. In 2013, the Morgan Foundation, headed by economist Gareth Morgan, launched the ‘Cats to Go’ campaign. The campaign stated that cat owners should keep their cats indoors 24 hours a day, have them neutered, and not replace them when they die. Various city councils have attempted to introduce laws that limit the number of cats per household, make it compulsory for cats to be microchipped, and make desexing compulsory (Forbes and Weekes Citation2016; Simmons Citation2016; Maxwell Citation2016; PCE Citation2007; Cooper Citation2022).

Participants in this survey thought feral cats were worse than rats in terms of threat, and, consistent with other research, they expressed support for the control of feral cats (Russell Citation2014; Russell et al. Citation2015). Current estimates put the number of feral cats in New Zealand in the millions (PCE Citation2007). However, for both feral cats and stray cats, young adults were more in favour of non-lethal approaches. Trap-neuter-release, trap-neuter-rehome and contraception were all more popular methods of control than shooting or poison. However, these results should be interpreted with caution. Participants were not given information on the effectiveness of trap-neuter-release (TNR) and other non-lethal methods. TNR programs aim to create populations where the cats can no longer reproduce and thus result in a decrease of numbers. But this depends on several variables. These include the prevention of immigration of cats from outside of the colony, maintaining ongoing high levels of de-sexing of the individuals within the colony and any new immigrants, the ongoing removal of a maximum number of cats for adoption, and the allowance of time for natural attrition to occur (Walker, Bruce, and Dale Citation2017).

Similarly, no additional information was given about the effectiveness of contraception. Previous research has found that while oral agents administered in baits can be made species specific, the disadvantage is that they must be consumed almost daily to be effective (Asa and Moresco Citation2019).

Attitudes towards predator control methods

This research supports the notion that, when it comes to predator control, it is not solely the outcome that matters but also the process used to achieve the outcome. A moderate proportion of young adults (44.5 per cent) expressed concern about the welfare of the targeted animals. Previous research on the wider public has noted that animal welfare is a particular concern when discussing predator control (Russell Citation2014).

The aerial distribution of poison was viewed negatively, with 22.8 per cent agreeing with its use (57.1 per cent did not agree with it). Over the last three decades, there have been several reports on the public’s attitudes towards and support of the use of 1080. In the mid-90s; Fitzgerald et al. studied the difference in attitudes towards aerial application and ground baiting. Ground baiting, with a 37 per cent acceptance rate, was more acceptable. Aerial application was only accepted by 27 per cent (Fitzgerald, Saunders, and Wilkinson Citation1996, Citation1994). In a 2012 survey of Coromandel people, 78 per cent of respondents supported the use of 1080 if it was used in a bait station compared with 51 per cent if 1080 was broadcast aerially (Kannemeyer Citation2013). More recently, a report released in 2023 found that 44.9 per cent of the public were supportive of the use of 1080 for controlling predators and 36.8 per cent were supportive of aerial drops of 1080 (Kerr, Hughey, and Cullen Citation2023). This strong variation in the results seems to be linked to the way the survey questions were phrased and the media coverage of 1080 at the time (Fraser Citation2006). Research also indicates that there are many different subgroups in New Zealand with different views on the use of toxins for predator control. Although the wider public is generally cautious on the use of toxins, especially through aerial distributions, the results of this survey indicate that young adults are even less in favour of its use, indicating that targeted communications is required.

Like the wider public, participants were more supportive of manual forms of control such as shooting, bait stations and trapping (Fraser Citation2006). Although these forms of control can be used in small, accessible areas, they are labour intensive, costly, and not feasible for remote, inaccessible areas. The willingness to support these methods may show that many young adults are not comprehending the full extent of the control that PF2050 will need. It is also interesting that bait stations were seen as a more acceptable form of predator control than aerial drops of poison. Aerial drops of poison mainly only utilise 1080, a poison that research suggests is moderately humane, whereas bait stations often use less humane poisons such as brodifacoum (Littin et al. Citation2014). Furthermore, an assessment in 1999 found that the ecological costs of using toxins are much less than the damage caused by introduced predators if they are not used, but more research on the repeated use of brodifacoum and other persistent toxins was needed (Innes and Barker Citation1999). The reason for the strong opposition to aerial drops of poison may be the perceived lack of discrimination in destination of the poison in the environment (such as it being dropped into waterways) and the risk to livestock, large feral mammals that are used for hunting, and domestic dogs, which are reasons often given (Eason et al. Citation2010; Hansford Citation2009). This result might also highlight a gap between perceived and actual animal welfare, or a lack of knowledge about the different poisons utilised in predator control. These results add to a considerable body of social science research that has found that a method that is species-selective and more humane is strongly preferred by the New Zealand public (Warburton et al. ). However, despite the large amount of resources and time that has gone into finding such an alternative method, one that has the same level of efficacy at the same cost has not yet been identified (Warburton et al. ).

The attitudes of young adults towards genetic technology as a predator control are important to establish now. While this technology faces numerous technical obstacles, the biggest hurdle to their use may come from public opinion (Druckman and Bolsen Citation2011). As the use of gene technology as a predator control tool would not be for at least another decade, it may well be today’s young adults who are the ones to see it through. The largely positive response (48.5 per cent) may reflect that young adults understand the need to develop another effective technology, if they have deemed aerial poison drops to be unacceptable. Less than a quarter of respondents disagreed with it. Genetic engineering may be perceived as a humane form of predator control, and this may have increased its popularity amongst young adults given the concern that was expressed for animal welfare. Many respondents did go on to state that, although gene drive looked promising, extensive research and testing would be needed before it could be utilised. A study published in 2020 found, in general, moderate support for the use of gene drive but stated that, as this is an emerging technology, there was unsurprisingly little knowledge, interest or concern about it (MacDonald et al. Citation2020). The same study recommended that future engagement surrounding this topic should incorporate the different worldviews and perspectives of participants (MacDonald et al. Citation2020). The results of this survey aligned with the review on attitudes to pest control methods in New Zealand, conducted in 2017 by Landcare Research (Kannemeyer Citation2017). This literature review found that criteria for support included humaneness; safety for humans and non-target species; specificity to the target species; effective control of the target species; cost efficiency; generation of additional benefits; tested or well researched and proven control; and no visible death (Kannemeyer Citation2017). The review highlighted that these criteria need to be supported with good communication, trustworthy science, rigorous and robust decision-making processes, and inclusive consultation with local communities.

In summary, like the wider population of New Zealand, young adults mostly support PF2050 and predator control, though they are critical of certain aspects. The generation most likely to be leading the effort to eradicate rats, stoats and possums from NZ expressed a need for caution and consideration over the methods used to achieve the aims of PF2050, especially regarding these methods’ impact on animal welfare. Targeted communication towards young adults on the use of toxins and gene drive for predator control is recommended to ensure that accurate scientific information on the pros and cons of both methods is conveyed. This communication should also include information about the humaneness of different types of toxins. The study also highlights that young adults are supportive of increased control of feral, stray, and domestic cats. More focused research on young adults’ attitudes towards cats is needed to fully understand the methods deemed acceptable and ensure that they will support future control initiatives. Over the next few decades, it is imperative that social scientists and policymakers involved in PF2050 discuss and communicate the nuances of the goal with this demographic to address any potential future conflict.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (528.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Edy MacDonald who reviewed the survey, and Dr. James Russell, from the University of Auckland, and Dr. Geoff Kerr, Dr. Ross Cullen, and Dr. Kenneth Hughey, from Lincoln University, for providing data from past surveys.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in OSF at http://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/5EKNS. [Identifier: doi: 10.17605/OSF.IO/5EKNS].

Additional information

Funding

References

- [PCE] Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment. Evaluating the Use of 1080: Predators, Poisons and Silent Forests, 2011PCE.

- [PCE] Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment. Taonga of an island nation: Saving New Zealand's birds, 2017PCE.

- Asa, C., and A. Moresco. 2019. “Fertility Control in Wildlife: Review of Current Status, Including Novel and Future Technologies.” Reproductive Sciences in Animal Conservation, 507–543. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-23633-5_17.

- Bergstrom, D. M., A. Lucieer, K. Kiefer, J. Wasley, L. Belbin, T. K. Pedersen, and S. L. Chown. 2009. “Indirect Effects of Invasive Species Removal Devastate World Heritage Island.” Journal of Applied Ecology 46 (1): 73–81. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2008.01601.x.

- Bertolino, S., and P. Genovesi. 2003. “Spread and Attempted Eradication of the Grey Squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) in Italy, and Consequences for the red Squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) in Eurasia.” Biological Conservation 109 (3): 351–358. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(02)00161-1.

- Chand, R. R., and B. J. Cridge. 2020. “Upscaling Pest Management from Parks to Countries: A New Zealand Case Study.” Journal of Integrated Pest Management 11 (1): 8. doi:10.1093/jipm/pmaa006.

- Clavero, M., and E. García-Berthou. 2005. “Invasive Species are a Leading Cause of Animal Extinctions.” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 20 (3): 110. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.01.003.

- Cooper, K. 2022, June 22. “Whangārei District Council Passes Mandatory Desexing and Microchipping for Pet Cats.” New Zealand Herald. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/northern-advocate/news/.

- Crowl, T. A., T. O. Crist, R. R. Parmenter, G. Belovsky, and A. E. Lugo. 2008. “The Spread of Invasive Species and Infectious Disease as Drivers of Ecosystem Change.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 6 (5): 238–246. doi:10.1890/070151.

- Dearden, P. K., N. J. Gemmell, O. R. Mercier, P. J. Lester, M. J. Scott, R. D. Newcomb, … D. R. Penman. 2018. “The Potential for the use of Gene Drives for Pest Control in New Zealand: A Perspective.” Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 48 (4): 225–244. doi:10.1080/03036758.2017.1385030.

- Devenport, E., E. Brooker, A. Brooker, and C. Leakey. 2021. “Insights and Recommendations for Involving Young People in Decision Making for the Marine Environment.” Marine Policy 124: 104312. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104312.

- Druckman, J. N., and T. Bolsen. 2011. “Framing, Motivated Reasoning, and Opinions About Emergent Technologies.” Journal of Communication 61 (4): 659–688. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01562.x.

- Eason, C., R. Henderson, S. Hix, D. MacMorran, A. Miller, E. Murohy, J. Ross, and S. Ogilvie. 2010. “Alternatives to Brodifacoum and 1080 for Possum and Rodent Control—how and why?” New Zealand Journal of Zoology 37 (2): 175–183. doi:10.1080/03014223.2010.482976.

- Estévez, R. A., C. B. Anderson, J. C. Pizarro, and M. A. Burgman. 2015. “Clarifying Values, Risk Perceptions, and Attitudes to Resolve or Avoid Social Conflicts in Invasive Species Management.” Conservation Biology 29 (1): 19–30.

- Esvelt, K. M., and N. J. Gemmell. 2017. “Conservation Demands Safe Gene Drive.” PLOS Biology 15 (11). doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2003850

- Farnworth, M. J., J. Campbell, and N. J. Adams. 2011. “What's in a Name? Perceptions of Stray and Feral cat Welfare and Control in Aotearoa, New Zealand.” Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 14 (1): 59–74. doi:10.1080/10888705.2011.527604.

- Farnworth, M. J., N. G. Dye, and N. Keown. 2010. “The Legal Status of Cats in New Zealand: A Perspective on the Welfare of Companion, Stray, and Feral Domestic Cats (Felis catus).” Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 13 (2): 180–188. doi:10.1080/10888700903584846.

- Farnworth, M. J., H. Watson, and N. J. Adams. 2014. “Understanding Attitudes Toward the Control of Nonnative Wild and Feral Mammals: Similarities and Differences in the Opinions of the General Public, Animal Protectionists, and Conservationists in New Zealand (Aotearoa).” Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 17 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1080/10888705.2013.799414.

- Fisher, D. 2017, December 4. “The Big Read: What Happened When One Expert Killer was Visited by the US Military’s Science Agency.” NZ Herald. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/.

- Fitzgerald, G., L. Saunders, and R. Wilkinson. 1994. Doing Good, Doing Harm: Public Perceptions and Issues in the Biological Control of Possums and Rabbits. Report prepared for MAF Policy and Landcare Research by NZ Institute for Social Research and Development. Christchurch, New Zealand.

- Fitzgerald, G., L. Saunders, and R. Wilkinson. 1996. “Public Perceptions and Issues in the Present and Future Management of Possums.” In MAF Policy Technical Paper 96/4. Wellington.: Ministry of Agriculture.

- Forbes, M., and J. Weekes. 2016, March 11. Wellington Bylaw Would Cap Cat Numbers, Ban Roosters and Limit Pigeon Feeding. Stuff. http://www.stuff.co.nz.

- Fraser, A. 2006. Public Attitudes to Pest Control. A Literature Review. Wellington: Department of Conservation.

- Fresh Perspective>Insight. 2022. Understanding the Health of the Predator Free Movement. Wellington, New Zealand: Predator Free New Zealand Trust. https://predatorfreenz.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/PFNZ_Final_2022.pdf.

- Gemmell, N. J., A. Jalilzadeh, R. K. Didham, T. Soboleva, and D. M. Tompkins. 2013. “The Trojan Female Technique: A Novel, Effective and Humane Approach for Pest Population Control.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 280 (1773): 20132549. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2549.

- Green, W., and M. Rohan. 2012. “Opposition to Aerial 1080 Poisoning for Control of Invasive Mammals in New Zealand: Risk Perceptions and Agency Responses.” Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 42 (3): 185–213. doi:10.1080/03036758.2011.556130.

- Hansford, D. 2009, May. 1080. New Zealand Geographic 97: 52–63.

- Harper, G. A., S. Pahor, and D. Birch. 2020. “The Lord Howe Island Rodent Eradication: Lessons Learnt from an Inhabited Island.” Proceedings of the vertebrate pest conference 29(29).

- Harvey-Samuel, T., T. Ant, and L. Alphey. 2017. “Towards the Genetic Control of Invasive Species.” Biological Invasions 19 (6): 1683–1703. doi:10.1007/s10530-017-1384-6.

- Hubbard, A. 2015, March 15. A Toxic History of 1080 in New Zealand. Stuff. https://www.stuff.co.nz/.

- Hughey, K. F., G. N. Kerr, and R. Cullen. 2016. Public Perceptions of New Zealand’s Environment: 2016. Christchurch, New Zealand: EOS Ecology.

- Innes, J., and G. Barker. 1999. “Ecological Consequences of Toxin Use for Mammalian Pest Control in New Zealand—An Overview.” New Zealand Journal of Ecology 111–127.

- In the News. 2017, December 5. US Military Investment in Gene Drives. Science Media Centre. https://www.sciencemediacentre.co.nz/.

- Jolliff, E. 2017, December 5. 1080 Protesters Threaten to ‘Bring Down’ DoC helicopters. Newshub. http://www.newshub.co.nz/.

- Kannemeyer, R. 2013. Public Attitudes to Pest Control and Aerial 1080 use in the Coromandel. MSc, University of Auckland, Auckland 209 p.

- Kannemeyer, R. L. 2017. A Systematic Literature Review of Attitudes to Pest Control Methods in New Zealand. Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research: Lincoln, NZ.

- Kerr, G. N., K. F. Hughey, and R. Cullen. 2023. Public Perceptions of 1080 Poison Use in New Zealand.

- Kirk, N., R. Kannemeyer, A. Greenaway, E. MacDonald, and D. Stronge. 2020. “Understanding Attitudes on new Technologies to Manage Invasive Species.” Pacific Conservation Biology 26 (1): 35–44. doi:10.1071/PC18080.

- Linklater, W. 2017, May 09. Predator Free 2050 is Scientifically Flawed [blog post]. https://sciblogs.co.nz/.

- Littin, K., P. Fisher, N. J. Beausoleil, and T. Sharp. 2014. “Welfare Aspects of Vertebrate Pest Control and Culling: Ranking Control Techniques for Humaneness.” Revue Scientifique et Technique (International Office of Epizootics) 33 (1): 281–289.

- MacDonald, E. A., J. Balanovic, E. D. Edwards, W. Abrahamse, B. Frame, A. Greenaway, … D. M. Tompkins. 2020. “Public Opinion Towards Gene Drive as a Pest Control Approach for Biodiversity Conservation and the Association of Underlying Worldviews.” Environmental Communication 14 (7): 904–918. doi:10.1080/17524032.2019.1702568.

- MacDonald, E. A., M. B. Neff, E. Edwards, F. Medvecky, and J. Balanovic. 2022. “Conservation Pest Control with new Technologies: Public Perceptions.” Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 52 (1): 95–107. doi:10.1080/03036758.2020.1850481.

- Maxwell, J. 2016, July 19. Kapiti Subdivision Imposes a No-Cats Covenant to Protect Wildlife. Stuff. http://www.stuff.co.nz.

- Murphy, E. C., J. C. Russell, K. G. Broome, G. J. Ryan, and J. E. Dowding. 2019. “Conserving New Zealand’s Native Fauna: A Review of Tools Being Developed for the Predator Free 2050 Programme.” Journal of Ornithology 160 (3): 883–892. doi:10.1007/s10336-019-01643-0.

- [NAWAC] National Animal Welfare Advisory Committee. 2007. Animal Welfare (Companion Cats) Code of Welfare; Ministry of Primary Industries.

- Nicoll, D. 2016, October 8. Large Turnout at Fiordland Anti-1080 Protest. Stuff. https://www.stuff.co.nz.

- [NZCAC] New Zealand Companion Animal Council. 2011. Companion Animals in New Zealand. Publicis Life Brands.

- Ogden, J., and J. Gilbert. 2011. Running the Gauntlet: Advocating Rat and Feral Cat Eradication on an inhabited Island–Great Barrier Island, New Zealand. Island invasives: eradication and management, 467-471.

- One News Now. 2017, December 6. NZ Playing Key Role in US Military’s Research into Controlling Rats. TVNZ. https://www.tvnz.co.nz/.

- Parkes, J. P., G. Nugent, D. M. Forsyth, A. E. Byrom, R. P. Pech, B. Warburton, and D. Choquenot. 2017. “Past, Present and two Potential Futures for Managing New Zealand’s Mammalian Pests.” New Zealand Journal of Ecology 41 (1): 151–161. doi:10.20417/nzjecol.41.1.

- Potts, A. 2009. “Kiwis Against Possums: A Critical Analysis of Anti-Possum Rhetoric in Aotearoa New Zealand.” Society & Animals 17 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1163/156853009X393738.

- Russell, J. C. 2014. “A Comparison of Attitudes Towards Introduced Wildlife in New Zealand in 1994 and 2012.” Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 44 (4): 136–151. doi:10.1080/03036758.2014.944192.

- Russell, J. C., J. G. Innes, P. H. Brown, and A. E. Byrom. 2015. “Predator-free New Zealand: Conservation Country.” BioScience 65 (5): 520–525. doi:10.1093/biosci/biv012.

- Russell, J. C., C. N. Taylor, and J. P. Aley. 2018. “Social Assessment of Inhabited Islands for Wildlife Management and Eradication.” Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 25 (1): 24–42. doi:10.1080/14486563.2017.1401964.

- Saavedra, S., and F. M. Medina. 2020. “Control of Invasive Ring-Necked Parakeet (Psittacula krameri) in an Island Biosphere Reserve (La Palma, Canary Islands): Combining Methods and Social Engagement.” Biological Invasions 22 (12): 3653–3667. doi:10.1007/s10530-020-02351-0.

- Schüttler, E., R. Rozzi, and K. Jax. 2011. “Towards a Societal Discourse on Invasive Species Management: A Case Study of Public Perceptions of Mink and Beavers in Cape Horn.” Journal for Nature Conservation 19 (3): 175–184. doi:10.1016/j.jnc.2010.12.001.

- Simmons, G. 2016, August 4. Wellington City Council Cat Bylaw a Win for the Environment [blog post]. http://morganfoundation.org.nz/the-council-and-the-cats/.

- Statistics New Zealand. 2018. New Zealand's Census of Population and Dwellings. https://www.stats.govt.nz/topics/census.

- Thomas, M. J., I. D. Giannoulatou, E. Kocak, W. Tank, R. Sarnowski, P. E. Jones, and S. R. Januchowski-Hartley. 2021. “Reflections from the Team: Co-Creating Visual Media About Ecological Processes for Young People.” People and Nature 3 (6): 1272–1283. doi:10.1002/pan3.10241.

- Tompkins, D. M. 2018. “The Research Strategy for a ‘Predator Free’ New Zealand.” In Proceedings of the Vertebrate Pest Conference (Vol. 28, No. 28). doi:10.5070/V42811002

- Walker, J. K., S. J. Bruce, and A. R. Dale. 2017. “A Survey of Public Opinion on cat (Felis Catus) Predation and the Future Direction of cat Management in New Zealand.” Animals 7 (7): 49. doi:10.3390/ani7070049.

- Warburton, B., C. Eason, P. Fisher, N. Hancox, B. Hopkins, G. Nugent, … P. E. Cowan. 2022. “Alternatives for Mammal Pest Control in New Zealand in the Context of Concerns About 1080 Toxicant (Sodium Fluoroacetate).” New Zealand Journal of Zoology 49 (2): 79–121.