ABSTRACT

Soft plastics pose significant environmental and waste management challenges in Australia and globally. As a pioneering programme that aimed to enhance soft plastic collection and recycling in Australia, the REDcycle initiative was discontinued due to the lack of adequate end markets. By integrating actor-network and sustainability transitions theories, this article analyses existing soft plastic governance arrangements and examines lessons from the discontinuation of REDcycle. Suggested solutions for enhancing soft plastic governance include policy and regulatory reforms, local market enhancement and stakeholder collaboration strategies. The article contributes significantly to the ongoing scholarly and policy discourse on the circular plastics economy.

1. Introduction

Soft plastics, which encompass flexible packaging including plastic bags, films, pouches and shrink wraps, are a unique and pervasive element in waste management systems. They offer valuable packaging solutions, particularly for food, keeping products shelf stable while potentially limiting food waste (Kirwan, Plant, and Strawbridge Citation2011). Furthermore, their light weight and adaptable qualities have made them useful for various industries and applications, resulting in their presence in all three major waste categories: construction and demolition, commercial and industrial waste and municipal solid waste.

However, the ubiquity of soft plastics also poses a significant challenge to the environment and waste management, in Australia and globally. The composition and potential contamination during collection and sorting (CSIRO Citation2021; Hahladakis and Iacovidou Citation2018) make these materials difficult to recycle, leading to their disposal in landfills or – historically – overseas exportation. They contribute to resource depletion and greenhouse gas emissions through production processes and landfill disposal and often escape into the marine environment.

The introduction of the REDcycle soft plastics collection programme in 2011 provided one possible mechanism to recover soft plastics in Australia. The scheme invited householders and consumers broadly to separate approved soft plastics at the point of consumption and then deposit the plastics in collection bins at local supermarkets. However, the scheme was discontinued in 2022 due to the lack of markets for the collected materials, a consequence of the China National Sword policy (Hughson Citation2022). The policy revealed Australia’s struggle to establish and maintain local markets for recovered soft plastics (Hossain et al. Citation2022; Macklin and Dominish Citation2018).

These challenges underscore the critical need for immediate and effective management strategies. Specifically, Australia needs more sustainable and comprehensive solutions to manage its soft plastics, including the adoption of circular economy approaches (Cáceres Ruiz and Zaman Citation2022; Hossain et al. Citation2022). Circular economy approaches aim to prolong the use of resources such as soft plastics for as long as possible, extract the maximum value from them while in service and recover and regenerate products and materials at the end of their lifecycle. This approach requires designing, producing and consuming these materials to minimise waste and maximise value (Govindan and Hasanagic Citation2018).

Recent studies have begun to explore the implications of achieving a circular plastic economy in Australia, especially in light of the discontinuation of the REDcycle initiative. These issues include national regulatory response (Bousgas and Johnson Citation2023), voluntary measures (Jones and Head Citation2023), public attitudes (Dilkes-Hoffman et al. Citation2019), waste campaigns and policies (Willis et al. Citation2018), environmental impacts (Leterme et al. Citation2023) and regional plastic actions (Cáceres Ruiz and Zaman Citation2022; Macintosh et al. Citation2020). However, the governance of soft plastics has been has received limited scholarly attention in the literature despite being one of the most problematic plastic types in the Australian market.

This article addresses the question of how Australia can improve its approach to soft plastic governance to achieve a circular economy. The article develops an integrated socio-technical framework based on the actor-network theory and the sustainability transitions theory to analyse soft plastic governance dynamics.

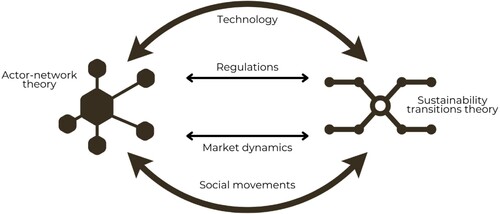

Actor-network theory suggests that human and non-human actors collaborate to establish and transform social realities (Latour Citation1987, Citation2005). We use the actor-network theory approach to gain insight into the role of soft plastic actors in shaping soft plastic governance in Australia. Similarly, sustainability transitions theory posits that transitions are a comprehensive, long-term and systemic change process involving multiple actors and levels (Köhler et al. Citation2019). We apply the sustainability transitions theory perspective to understand the transition dynamics of the current soft plastic waste regime, emerging niche innovations and the broader waste management landscape. Integrating the actor-network theory and sustainability transitions theory perspectives reveals soft plastic governance factors, including technology, regulations, market dynamics and social movements.

In Section 2, this article examines current soft plastic governance arrangements. Section 3 outlines the methodology. Section 4 analyses the dynamics of soft plastic governance and the circular economy in Australia using actor-network theory and sustainability transitions theory. Section 5 presents an analysis of the REDcycle case. Section 6 proposes various strategies to enhance soft plastic governance in Australia, including policy and regulatory reforms, local market enhancement and stakeholder engagement. These solutions contribute significantly to the ongoing scholarly and policy discourse on sustainable plastic waste management. Finally, Section 7 concludes with the importance of ongoing scholarly and policy discourse on the circular plastic economy.

2. Overview of existing soft plastic waste governance approaches

The global packaging industry is undergoing significant growth propelled by the surge in online sales and urbanisation trends. Plastic waste generation is also on the rise. The Plastic Waste Makers Index revealed that 139 million metric tons of single-use plastic waste was produced globally in 2021, an increase of 5 million metric tons from 2019 (Minderoo Foundation Citation2023).

While plastic packaging may offer convenience, it has proven detrimental to the environment and society when not managed effectively. To compound the problem, an estimated 11 million metric tons of plastic are discarded into our oceans annually (Reddy and Lau Citation2020). Where plastic packaging is collected as part of waste management strategies, recycling facilities are struggling to keep up with the mounting packaging generated. In the United States, just 5 per cent of residential, commercial and institutional plastic waste was recycled in 2021 (Ramirez and Romine Citation2022).

Furthermore, mixed plastic collection systems and the resulting contaminants create complications for plastic recycling. Globally, most plastics collected for recycling are still downcycled, resulting in a considerable loss of value in the process (Johansen et al. Citation2022). Nonetheless, the emergence of new technologies, such as advanced recycling, holds the potential to facilitate plastic upcycling on a larger scale. This underscores the need to transition to a circular plastic economy, which has the potential to reduce virgin plastic production significantly by 55 per cent (United Nations Environment Programme Citation2021). Accordingly, many global, national and local initiatives are emerging to accelerate this transition.

On a global governance level, the United Nations Environment Assembly is currently negotiating the world’s first-ever legally binding international plastic treaty, receiving support from 175 nations. The treaty highlights the global consensus and urgency surrounding plastic pollution (United Nations Environment Programme Citation2022).

Nation-states and their provincial/state and municipal governments in various parts of the world have recognised the urgency of addressing this crisis and have implemented different effective strategies to manage plastic waste, including alternative materials, post-consumer plastic collection, and recycling promotion. For example, in 2022, California passed legislation mandating a 25 per cent reduction in plastic packaging sales by 2032 (Anguiano Citation2022). Similarly, the European Union and several Australian states and territories have banned single-use plastic items (European Commission Citationn.d.; Judd Citation2023).

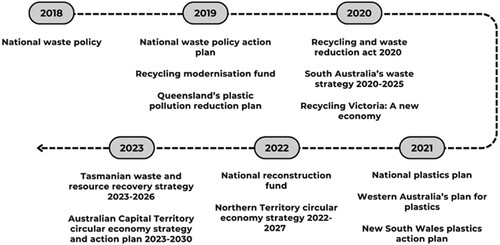

In Australia, waste governance is a complex process that involves national, state, territory and local actors and policies (see ). The Australian Federal Government plays a crucial role in coordinating these across horizontal and vertical governance levels and with industries and communities. In 2019, the Council of Australian Governments agreed to develop a National Waste Action Plan, which focuses on banning plastic exports, phasing out unnecessary plastics, and increasing recycling and recycled content utilisation (Jones and Head Citation2023; Schandl et al. Citation2021). The Recycling and Waste Reduction Act (2020) provides a comprehensive national framework for managing waste and recycling throughout Australia, including export waste (Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water [DCCEEW] Citation2022a).

In 2021, following the inaugural National Plastics Summit, the National Plastics Plan was unveiled (Hardesty, Willis, and Vince Citation2022; Hossain et al. Citation2022). This long-term plan outlines various targets, mainly related to recycling and plastics, with a commitment to collaborate with the industry, boost investments in recycling capabilities and expand research efforts, aiming to establish Australia as a global leader in this domain (Jones Citation2020; Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and the Environment [DAFE] Citation2021). The plan recognises that states and territories play a fundamental role in achieving these targets, and successful implementation requires cooperation at all levels of government. Therefore, the plan facilitates coordination between the federal government and state and territory governments to ensure a consistent approach across the country. The plan further pledges to expedite the implementation of the Australasian Recycling Label, including instructions for ‘conditionally recyclable’ items like soft plastics by the end of 2023 (Jones Citation2020).

In November 2022, the Federal Minister for the Environment announced the Ministerial Advisory Group on the Circular Economy as an expert group to advise the federal government on Australia’s transition to a circular economy by 2030 (DCCEEW Citation2022b). The Advisory Group commenced meeting in 2023 to provide recommendations to the Environment Minister on various themes, such as the built environment, circular design and innovation to drive a circular economy (DCCEEW Citation2023a).

Although national policies, such as the National Waste Policy, provide a governance framework, the day-to-day efforts of waste management are implemented at the state and local levels. Thus, state and territory governments have historically shaped the waste regulation landscape, with some leading in the development of plastic policies and regulations (). For instance, South Australia was the first state to ban lightweight shopping bags as far back as 2009 (Macintosh et al. Citation2020), and Western Australia announced the most comprehensive bans on single-use plastics in 2021 (Government of Western Australia Citation2024). Queensland has also followed suit with a five-year roadmap to ban a range of single-use plastics (Judd Citation2023).

Waste management approaches to plastics also differ across states. The South Australian government, for instance, has long-standing container deposit legislation for beverage packaging collection. In contrast, other states, like Tasmania, have yet to implement such legislation due to the need for adequate resources to effectively implement such programmes locally (Lane et al. Citation2023).

However, before the recent development of various initiatives and policies by the federal and state governments, the pace of progress in tackling the issue of soft plastic waste remained slow. Recycling facilities struggled to keep up with the mounting packaging generated, and mixed plastic collection systems and resulting contaminants created complications for plastic recycling. In response, the REDcycle programme emerged in the Australian soft plastic waste management landscape in 2011 as a voluntary initiative. The programme aimed to reduce soft plastic waste by encouraging consumers to drop off their soft plastics at designated REDcycle bins located at participating supermarkets. As such, REDcycle filled a gap in the waste governance landscape by collaborating with industry partners to provide an accessible and convenient option for consumers to recycle their soft plastics (Hughson Citation2022).

Following the discontinuation of REDcycle, which highlighted the weaknesses in the end-to-end supply chain in achieving a circular materials flow, industry stakeholders are now responsible for developing innovative solutions. For instance, the Australian Packaging Covenant Organisation (APCO), a peak industry body for the packaging sector, works collaboratively with industry and government to develop and implement sustainable packaging solutions. These include the National Packaging Targets and the Australia, New Zealand and Pacific Island Countries Plastics Pact (DCCEEW, n.d.).

Furthermore, the Australian Food and Grocery Council (AFGC) has been tasked with the development of a National Plastics Recycling Scheme, an industry-driven initiative supported by the Federal Government. The AFGC received funding to support the development of this scheme as part of the National Product Stewardship Investment Fund disbursements (AFGC Citation2023). The National Plastics Recycling Scheme aims to use advanced recycling technology to transform soft plastics into food-grade packaging. This sets the scheme apart from REDcycle, which facilitated the downcycling of soft plastics into items like garden equipment and outdoor furniture (Hughson Citation2022). The scheme conducted trials in Victoria, New South Wales and South Australia to assess models for expanded kerbside collection and processing. The National Plastics Recycling Scheme is anticipated to help fill the void left by REDcycle’s demise and propel Australia toward sustainable plastic waste management (AFGC Citation2023).

3. Methodology

This article uses a case study approach to analyse soft plastic governance in Australia. Case studies provide an effective research methodology for gaining in-depth insights into a specific phenomenon and its context (Neuman Citation2014; Yin Citation2009). The article’s focal point is the pioneering REDcycle initiative, the only soft plastics programme with nationwide coverage and significant consumer participation in Australia. Analysing the REDcycle provides valuable insights into Australia’s governance challenges and opportunities associated with soft plastic waste.

The article critically analyses recent academic literature, policy documents, industry and government reports, news articles and media releases to gather data on the REDcycle programme, soft plastic waste, circular economy, sustainability transitions and Australia’s waste management landscape. The analysis results are presented as a narrative synthesis, which discusses the key themes, insights and strategies related to soft plastic waste governance in Australia.

The discussions include the actors involved in soft plastic waste governance, circular economy challenges and opportunities, and the application of sustainability transitions theory and actor-network theory for governance analysis. Actor-network theory was used to understand the different actors involved in soft plastic waste governance and their roles, while sustainability transitions theory was used to understand the dynamics of sustainability transitions and their governance implications for various actors. Integrating these two frameworks further helped identify the factors that shape transition dynamics and actors’ behaviour, interactions and strategies within the soft plastic network.

In the next section, we explore how the integration of actor-network theory and sustainability transitions theory provides a framework for learning from REDcycle’s challenges and charting a path toward more sustainable solutions.

4. Unveiling the dynamics of soft plastic governance: an integrated socio-technical perspective

Achieving a circular economy in Australia requires a significant shift from the current linear approach of using, disposing and processing resources to a new model that emphasises waste reduction, material recycling and product reuse. However, implementing this transformation is a complex challenge as it faces various obstacles and resistance from the existing system and dominant regime. To successfully drive this change, it is essential to understand the intricacies and mechanisms of system governance and transition and apply appropriate theoretical frameworks. This necessitates a comprehensive understanding of the complicated network of actors, practices, technologies and processes involved in producing, consuming and disposing of soft plastics while simultaneously reducing, repurposing and recovering these materials.

This study addresses these complexities by integrating actor-network theory and sustainability transitions theory. This synthesis illuminates the intricate web of actors involved in soft plastic governance. We use the X-Curve model to highlight the complex dynamics of transitioning from a linear to a circular system. By integrating these frameworks, we evaluate the approaches to effectively tackle the complexities of soft plastic governance, fostering collaboration and sustainability in waste management.

4.1. Actor-network theory

Rooted in sociology, actor-network theory emerges as a potential framework to scrutinise Australia’s multifaceted landscape of soft plastic governance. This theoretical framework challenges conventional paradigms of agency, asserting that human and nonhuman actors engage in dynamic interactions, collectively crafting social realities (Latour Citation1987, Citation2005). Actor-network theory dismisses the notion of fixed roles or identities for actors, emphasising their perpetual negotiation and influence within networks (Latour Citation1992). Importantly, actor-network theory does not bestow primacy upon human agency at the expense of nonhuman agency; instead, it recognises the profound impact of both on outcomes (Callon and Law Citation1997). By applying actor-network theory to soft plastic governance, we unravel the intricate relationships that give rise to, sustain, and reshape the network of soft plastics and the environmental ramifications it entails. Finally, actor-network theory helps us understand the processes through which circular economy came into being to compete against the linear way of doing things (Niero et al. Citation2021).

presents the key actors within Australia’s web of soft plastic governance networks. These actors operate in a complex, interdependent network with evolving relationships and interactions (Michael Citation2017). For example, soft plastic manufacturers could work with recyclers to develop more eco-friendly products, while environmentally-conscious consumers may participate in recycling schemes promoted by advocates and recyclers. Regulators may also introduce mandates or incentives to encourage sustainable practices. Advocates could challenge stakeholders across the network, from manufacturers to regulators, to improve their environmental performance and accountability.

Table 1. Key actors in the web of soft plastic governance networks in Australia.

By utilising actor-network theory as a framework to analyse soft plastic governance in Australia, we can better understand this complex issue. actor-network theory sheds light on the challenges and opportunities in achieving a circular economy for soft plastics and provides insights into effective collaboration and potential conflicts between the different actors involved, ultimately shaping the environmental landscape (Flynn, Pagell, and Fugate Citation2020; Hald and Spring Citation2023).

4.2. Sustainability transitions theory

One of the most widely recognised frameworks in sustainability transitions research is the multi-level perspective, which distinguishes three analytical levels: the niche, the regime and the landscape (Geels Citation2002; Geels and Schot Citation2007). The niche represents the space where radical innovations emerge and are tested. The regime encompasses the established system’s dominant practices, rules and norms. The landscape comprises exogenous factors and pressures influencing the system, such as cultural values, political events or environmental shocks. According to the multi-level perspective, transitions occur when niche innovations break through and challenge the regime, supported by landscape changes creating windows of opportunity.

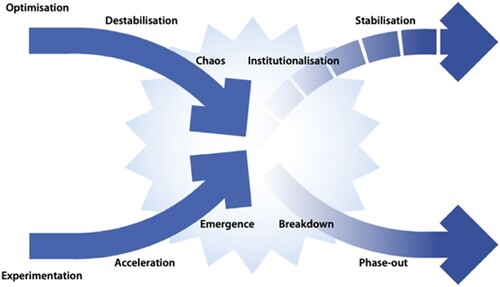

An extension of the multi-level perspective, the X-Curve transition model provides a temporal perspective on transitions and their governance implications for various actors. This model illustrates the co-evolution of two regimes: the declining old regime and the emerging new regime. According to Hebinck et al. (Citation2022),

[t]he X-curve is a conceptual framework that offers guidance in understanding and developing governance practices for sustainability transitions. It was developed to support diverse societal actors in understanding the dynamics of societal transitions, where dynamics of breakdown and decline are becoming more obvious and visible. (1019)

The X-Curve model offers a framework for understanding the process of introducing a new regime, beginning with experimentation and followed by acceleration towards commercialisation (see ). During the transition, the emergence phase occurs as the adoption of the new system becomes disruptive to the existing order. Meanwhile, the old regime continues to optimise until it recognises the transition and destabilises. As the transition progresses, there is potential for significant disruption and chaos as the old way of doing things breaks down (Hebinck et al. Citation2022).

Figure 2. X-curve transition model. Source: Hebinck et al. (Citation2022).

When applied to the Australian soft plastic governance system, the X-Curve model highlights its challenges. The old regime relies heavily on single-use plastics, with low recycling rates and waste export, lacking environmental and social sustainability. However, changing consumer preferences, awareness campaigns, regulatory bans, trade restrictions and environmental crises destabilise this regime and create opportunities for niche innovations. The new regime aims to reduce plastic consumption, increase recycling rates and develop local waste processing markets. However, its success is threatened by challenges such as lack of coordination, capacity mismatches, supply chain disruption and market uncertainty, as exemplified by the recent discontinuation of REDcycle.

Achieving a smooth and stable transition requires a comprehensive view of the entire soft plastic supply chain, ensuring alignment and integration of its elements. Effective governance arrangements involving collaboration among government, industry, civil society and academia, coordination across various local and national levels, and adaptability to changing circumstances and feedback are essential. The X-Curve model assists in identifying who should provide governance at different transition stages.

4.3. Integrating actor-network theory and sustainability transitions theory for soft plastic governance

The integrated socio-technical framework in delineates the governance factors that shape actors’ behaviours, interactions and strategies within actor-network theory networks. These factors also drive the dynamics of sustainability transitions and influence the adoption of circular economy principles and more sustainable practices in Australia’s soft plastic governance system. Understanding these factors is crucial for effective policy development, innovation and governance in transitioning toward a circular economy for soft plastics.

As a critical factor in actor-network theory, technology is vital in influencing human and nonhuman actors within the network. Soft plastic manufacturers and recyclers employ various technologies to produce, process and recycle materials (Hina et al. Citation2022; Silvério et al. Citation2023; Vallecha and Bhola Citation2019). These technologies shape their capabilities and interactions within the network. Technological advancements in recycling can lead to more efficient processes and a higher volume of recycled materials, thereby shaping the network’s dynamics. Technology is also a central element in sustainability transitions theory, affecting transitions at multiple levels. Innovations in waste sorting, recycling and processing technologies can drive transitions by enabling more sustainable practices. These innovations can create opportunities for experimentation and accelerate the adoption of circular economy principles.

Regulations represent an external factor within the actor-network theory framework. Regulators set rules and standards that influence the behaviour of all actors involved in soft plastic governance. Regulators may mandate specific recycling practices or impose restrictions on certain types of soft plastics, thereby affecting the strategies and interactions of manufacturers, consumers and recyclers (Hina et al. Citation2022; Mathews and Tan Citation2011). Furthermore, regulations are a significant driver of sustainability transitions, particularly at the regime level. Government policies and regulations can shape the dominant practices within the soft plastic governance system. For example, regulations that ban single-use plastics or promote extended producer responsibility can create regime pressures and support the emergence of more sustainable practices.

Market dynamics influence the decisions and strategies of actors in the actor-network theory network. Manufacturers respond to consumer demand and market trends, adapting their products accordingly (Siderius and Zink Citation2022). Recyclers may seek markets for recycled materials based on demand and pricing. Consumer choices, influenced by market availability and affordability, also impact the consumption and disposal of soft plastics. Likewise, market dynamics are critical to sustainability transitions, especially at the niche and regime levels. Changing market conditions can create opportunities for niche innovations to break through. For instance, increased consumer demand for eco-friendly products can drive manufacturers to adopt more sustainable materials and processes. Market disruptions, such as shifts in the demand for recycled materials, can also influence the success of sustainability transitions within the soft plastic governance system (Hogg et al. Citation2018).

Lastly, social movements can be considered external factors that influence actor-network theory networks. Advocates for environmental causes, part of the soft plastic governance network, mobilise resources, shape public opinion and challenge existing actors’ practices and roles. Their efforts can lead to changes in behaviours and priorities among manufacturers, consumers and other actors. Similarly, social movements are instrumental in sustainability transitions theory, particularly in shaping landscape-level factors. Movements advocating for reduced plastic consumption and waste reduction can contribute to landscape pressures, destabilising the old regime and supporting new practices. These movements can also influence regulators and market dynamics by raising awareness and driving changes in public attitudes and policies (de Jesus and Mendonça Citation2018).

5. Challenges and lessons learned from REDcycle: a case study in soft plastic governance

The RED Group, which developed and implemented the REDcycle initiative, was founded by Elizabeth (Liz) Kasell in 2011 with the aim of promoting soft plastic recycling in Australia. Its humble beginnings in a kitchen were driven by a collective determination to find a solution to the issue (Hughson Citation2022; Vedelago Citation2022), reflecting the governance factor of social movements in the integrated socio-technical framework. From actor-network theory and sustainability transitions theory perspectives, social and technological changes are driven by networks of actors, and the success of a transition towards sustainability depends on these networks’ ability to integrate and align their goals and values.

The REDcycle initiative was promoted to give soft and single-use plastics a second life and keep them out of the landfill (Gredley Citation2015; Hepplestone Citation2017; Lewis Citation2017). It also aimed to support households in boosting their recycling capacity to benefit the environment and communities (Cox Citation2018; Jenkins Citation2021; Topsfield Citation2018). The initiative’s success was dependent on the collaboration of multiple stakeholders, including supermarkets, consumers and recycling companies, which is in line with the governance factors of the integrated socio-technical framework.

However, while REDcycle’s in-store collection programme had some success, managing soft plastic waste in Australia presented significant challenges and opportunities for improvement. The complex supply and reverse supply chain and insufficient market demand for recovered materials made it challenging for REDcycle to recycle all the collected products, highlighting an ineffective market dynamics governance factor. As a result, the programme ceased operating in November 2022 (Hughson Citation2022).

In the wake of REDcycle’s collapse, questions were raised about the programme’s integrity. Media articles reported that consumers were ‘outraged’ (Achenza Citation2022) and ‘betrayed’ as details of the ‘secret’ stockpiles and mismanagement of soft plastics emerged (Vedelago and Dowling Citation2022). This attracted speculation about whether the programme had misled consumers by not admitting to the stockpiling earlier (Vedelago and Juanola Citation2023). However, despite some negative perceptions of REDcycle’s practices, most media commentary has situated the programme’s challenges within the broader context of a ‘broken’ recycling system (Phelan Citation2022, para. 5) and the perpetual absence of sufficient markets for soft plastics (Murray-Atfield Citation2023).

The programme’s suspension also sparked a loss of consumer trust and confidence in Australia’s plastics recycling system as the realities of soft plastics were laid bare (APCO Citation2023; Malcolm, Citation2022). For example, local councils have been left to deal with complaints and frustrations from consumers over the diversion of soft plastics to landfills and the loss of trust in the recycling industry (Local Government Association of South Australia Citation2023). There is now an imperative for the government and industry to restore consumer confidence in plastic recycling. Initiatives such as the National Plastics Recycling Scheme are more vital than ever, providing new solutions that demonstrate that soft plastic recycling is possible at scale.

The REDcycle case study highlights the importance of community engagement, scalable solutions involving multiple stakeholders and a diverse supply chain to address the plastic waste crisis in Australia. By examining both the challenges and successes of the REDcycle initiative, this study provides valuable insights into the limitations and opportunities of Australia’s soft plastic recycling system. It is evident that collaborative efforts are necessary to tackle the plastic waste crisis, and programmes like REDcycle represent a crucial step towards a circular economy if they are appropriately supported and resourced.

5.1. The supply chain dynamics of the REDcycle programme

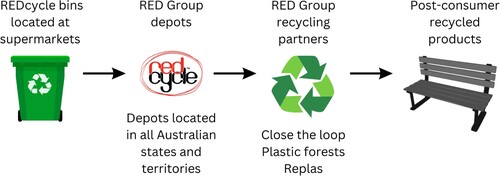

Based on the integrated socio-technical framework, sustainable transitions require the mobilisation of a complex network of actors and infrastructures. Adhering to this, the REDcycle initiative relied on consumers’ return of soft plastics to designated points of collection located across a spectrum of retail stores throughout the country. As the initiative expanded, it formed partnerships with large collection point partners (see ), and collection bins were distributed to major supermarkets. Prominent collection infrastructure was established, often at the entrances/exits of stores, with retailers like Coles and Woolworths playing a crucial role in encouraging individuals to recycle their soft plastics and reduce plastic waste sent to landfills. Additionally, REDcycle received broad community visibility due to its logo being featured on the packaging of many well-known brand names (Kasell Citation2023), indicating support from the business community to enhance programme uptake.

The REDcycle scheme focused on collecting post-consumer soft plastics, typically from the retail and food sectors. While they are used widely in the construction, agriculture, industrial, commercial and retail sectors, the food and beverage sector is the largest consumer of soft plastics (APCO Citation2019).

Customers quickly embraced new recycling practices by collecting soft plastics, with supermarkets publishing annual soft plastic recycling data from collection points. Moreover, positive media attention towards the REDcycle initiative played a vital role in changing household waste practices and norms for the disposal of single-use plastics (see also Borg, Lindsay, and Curtis Citation2021). The widespread engagement with the positive outcomes of REDcycle in diverting soft plastics from landfills and its alignment with the values and realities of households influenced the popularity and credibility of the associated messages.

The initiative purportedly diverted 5.4 billion soft plastic items (Vedelago Citation2022), which would have otherwise been disposed of in landfills. By the time of the programme’s closure in 2022, it was collecting 5 million pieces of soft plastic a day (Vedelago Citation2022), representing a real success in uptake. However, due to the stockpiling of over 12,400 tonnes of collected materials from as early as 2018, the actual percentage of soft plastics sent for reprocessing remains uncertain (Vedelago Citation2023).

However, from an integrated socio-technical perspective, the adoption and diffusion of innovations are contingent on the nature and interaction of technological and sociocultural factors at the landscape and regime levels. In REDcycle’s case, the initiative had to navigate a highly intricate supply/reverse supply chain for soft plastics after collection, which involves multiple stakeholders, including oil/polymer producers, commercial brands, retailers, logistics partners, converters and post-consumer recyclers (see ). This complexity made the back-end management and processing of collected material particularly challenging.

Furthermore, despite major brands, retailers, and producers promoting recyclability by emphasising this on their soft plastic packaging (i.e. using the REDcycle logo), collecting and processing post-consumer soft plastics remained a significant challenge. The soft plastics collected by REDcycle included mono- and multi-layer materials. Amongst the mono-materials, the most common are LDPE, LLDPE, HDPE and PP. Soft plastics, however, can also be made from, or in combination with, many other polymers (APCO Citation2019). The multi-layered materials (such as sachets and chip packets) can contain three to nine layers of different materials, including foils and a variety of polymers, so the collected materials were diverse and complex. The highly diverse feedstock collected by consumers means that finer sorting was not feasible resulting in a recyclability challenge.

The complexity of the soft plastic supply chain is further exacerbated by the sparseness of end markets for these materials. As Close the Loop Group CEO Joe Foster stated in 2022:

We understand that such a diverse mix of soft plastics is not attractive to many in Australia’s plastics recycling industry, and not suited to chemical recycling either in its current form, but it still has value if you know how to extract it. (Hughson Citation2022, para. 23)

Furthermore, the REDcycle initiative faced challenges in engaging stakeholders along the supply chain to participate. While major supermarkets and other retailers supported the programme in helping with collection points, other essential stakeholders, such as recyclers willing to accept soft plastic feedstock, were not as easy to engage. The diversity of soft plastic types and the lack of adequate end markets appeared to have hindered the initiative’s ability to scale and achieve its goals.

5.2. The loss of recycling partners and fire at the Close the Loop facility

REDcycle collected more than 7,000 tons of soft plastic annually, with a reported 350 per cent increase in collection since 2019 across thousands of retail store sites (Kasell Citation2023). This rise in collection volume was credited to a large-scale shift in behaviour with Australians becoming advocates of diverting soft plastics from landfills and the online shopping boom where plastic packaging was and still is rampant (Kasell Citation2023).

REDcycle’s collected material was recycled by three major associates: Close the Loop, Plastic Forests and Replas. The three recyclers collectively processed an estimated 3,200 tons of soft plastic yearly (Vedelago Citation2022). Close the Loop, which recycled the majority of the reclaimed material, transformed the soft plastics into TonerPlas, an asphalt additive, as well as rFlex, a recycled plastic injection-moulding resin. Plastic Forests produced a range of items from recycled soft plastics, including gardening kits, while Replas integrated REDcycle material into its recycled plastic outdoor furniture and decking products (Hughson Citation2022).

Ultimately, the reprocessing partners’ capacity fell well short of the material volumes the programme collected (Vedelago Citation2022). As REDcycle founder Liz Kasell stated, ‘REDcycle’s recycling partners were unable to accept and process the rapidly increasing volume of soft plastics due to lack of immediate access to infrastructure, inadequate processing capacity and, most importantly, reduced demand for recycled products’ (Kasell Citation2023, para. 12). As a result, as early as 2018, the programme stockpiled excess material (Vedelago Citation2022).

In June 2022, the Close the Loop facility suffered a fire that caused significant damage to the TonerPlas line. The fire underscored the vulnerability of REDcycle’s supply chain, as Close the Loop was its primary recycler. In 2022, some of the recycling partnerships started to dissolve. Plastics Forests parted ways with the programme in February 2022, while Replas ceased accepting REDcycle plastics in late 2022 due to oversupply (Hughson Citation2022). Consequently, at this point, no recyclers were accepting REDcycle collected material. This situation highlights the importance of considering a diversified supply chain when implementing resources, funding and regulatory interventions to a programme that initially started as a small scheme but proliferated. The absence of recyclers also meant that stockpiles of stored soft plastics would increase at an ever-increasing pace, and at this stage the programme announced a pause in November 2022 (Hughson Citation2022).

Even without the fire, significant efforts would still have been required to bridge the gap between what was being collected and the lack of adequate recycling capacity to handle the complete volume of waste streams collected by REDcycle. Interestingly, in 2023, Close the Loop announced its intention to continue accepting increased and significant volumes of REDcycle soft plastic, with the ability to process up to 5,000 tons of REDcycle material annually. This equates to almost a year of REDcycle’s total collections (Hughson Citation2022). At the time of writing, other former partners have not made such announcements. Since the programme’s closure, the extent of potentially hazardous stockpiling of soft plastics has become apparent. Regulators continue to investigate the scale of the issue and have subsequently started to charge the REDcycle operators concerning allegations relating to the stockpiles (Cassidy Citation2022).

Retailers and the Australian federal government have also taken action to begin planning for the future of soft plastics. The amplifying effect of media coverage has prompted a more extensive response from supermarkets with major Australian supermarkets collaborating to adopt a ‘Roadmap to Restart’ plan in 2023 (Kasell Citation2023). In February 2024, in-store soft plastic collection trials commenced in twelve Melbourne suburbs with plans to potentially expand to other locations (Korycki Citation2024).

5.3. The key learnings – need for a comprehensive approach to supply chain governance

The REDcycle case offers several critical insights using the integrated socio-technical perspective. In some respects, the programme served as a successful model of stewardship that focused on source separation and collection with the aim of reducing the amount of soft plastic packaging that ends up in landfills. Its high visibility, facilitated by prominent in-store collection infrastructure at some of Australia’s largest retailers and eminence on the packaging of many of the nation’s most well-known brands, has led to rapid growth and community participation, with billions of items collected. This underscores the significance of community engagement, linked to a shared responsibility among manufacturers, retailers, and consumers for a sustainable future – a key programme aim (Kasell Citation2023).

Nevertheless, the case highlights the perils of such approaches when market support is lacking, resources are constrained and some aspects of the programme succeed and scale quickly. The REDcycle programme faced several challenges, including inadequate uptake of recovered soft plastic material, the loss of recycling partners, and a fire at a strategically vital reprocessing line in the Close the Loop facility. These factors emphasise the need for a comprehensive approach to supply chain governance and a range of partners and options in such contexts. In essence, the REDcycle case study epitomises the necessity of continuous investment and resourcing in the circular economy while emphasising the importance of all relevant stakeholders working together towards a common goal.

In the meantime, it is recommended that policymakers facilitate a series of engagements for discussion and action on this issue, involving all supply chain stakeholders and considering the implementation of various mechanisms to achieve desired societal, environmental and economic outcomes. This type of activity has already begun (Jolly Citation2023), but there is scope for expansion. Policy responses may range from financial incentives, penalties and regulation/deregulation to collaborative vehicles, among other options, much like what has been suggested in the recent national strategy for designing a circular economy (Lockrey et al. Citation2022). This holistic approach is critical to ensuring the long-term sustainability of plastic waste governance practices in Australia. It is essential to consider the entire lifecycle of plastic products, from production to disposal, and work towards a closed-loop system with a range of stakeholders willing and able to bring about changes that reduce waste and minimise environmental impact. Lastly, the REDcycle case study underscores the importance of academic research and analysis in understanding pressing environmental challenges.

6. Evaluating solutions for effective soft plastic governance in Australia

In this section, we explore various approaches to overcome the challenges of managing soft plastics effectively in Australia based on the integrated socio-technical transitions framework, with the broader goal of supporting the transition to a circular economy for soft plastics. To achieve this, Australia must adopt a comprehensive waste governance system that combines regulatory measures like extended producer responsibility and product stewardship policies that place responsibility on producers to manage the entire lifecycle of their products, encouraging them to design environmentally friendly products and invest in recycling infrastructure, with effective stakeholder engagement and collaboration across the entire soft plastic supply chain. By implementing the strategies outlined in and discussed further in this section, Australia can extract maximum value from soft plastics while minimising waste and advancing towards a circular economy.

Table 2. Overview of solutions for effective soft plastic governance in Australia.

6.1. Integrating comprehensive policy and regulatory framework with sustainable packaging

Australia’s plastic waste governance system is currently subject to incomplete regulatory interventions that fail to address the full scope of the issue. National-level plans provide targets that the states and local governments need to implement; however, many waste management policies focus on specific aspects, such as waste collection or recycling targets, without considering the broader challenges. For instance, while the National Plastics Plan infers soft plastics and the lack of adequate soft plastic recycling, they are not directly addressed (DAFE Citation2021). This limited approach leaves gaps in the system and allows specific stakeholders to avoid taking responsibility for their contribution to plastic waste.

It is imperative that all stakeholders fulfil their obligations and actively contribute to sustainable waste governance practices. This can only be achieved by establishing a more comprehensive and integrated regulatory framework. As presented in , such a framework should include legislation that delineates the responsibilities of each government, industry and community level. The Circular Economy Ministerial Advisory Group has echoed this need, recommending that federal government regulations be revised and strengthened to ensure they are fit-for-purpose and future-ready to support a circular economy (DCCEEW Citation2023a, 1).

The integrated socio-technical framework underscores the necessity of a comprehensive approach across all levels of government, encompassing all stages of the plastic waste lifecycle. Equally important is the need for greater vertical integration among government and stakeholders. This entails setting stricter waste reduction targets, enhancing collection and recycling infrastructure and enforcing extended producer responsibility policies (Hossain et al. Citation2022).

To provide a foundation for effective extended producer responsibility implementation, the scope of the Product Stewardship Act needs to be strengthened and expanded. The regulatory aspects of sustainable packaging have gained significant attention, both in academic circles and the industry. There is a growing consensus on the need for a more robust regulatory framework to address packaging-related issues (Arreza and Hughson Citation2023). Even packaging companies, traditionally not inclined towards regulatory measures, have expressed a desire for government intervention and guidance.

One potential solution suggested by the integrated socio-technical framework is the implementation of mandatory packaging design standards by the government (see ), such as using single polymers exclusively. However, the impact of such a measure on the existing packaging landscape raises uncertainties, particularly regarding soft plastics that commonly contain mixed polymers. Determining the effects on current practices requires careful consideration and further research to ensure a smooth transition. By combining regulatory interventions with sustainable packaging practices, Australia can establish a more robust framework for managing plastic waste, reducing its environmental impact and promoting a circular economy. Implementing such a framework could be worth AUS $2 trillion but can only be achieved through holistic approaches from all levels of government (Towell Citation2021).

6.2. Facilitating stakeholder engagement and collaboration through governance

From an integrated socio-technical perspective, meaningful engagement and collaboration among stakeholders are essential for effective soft plastic governance. The governance arrangements need to address the involvement of multiple stakeholders, including waste producers, manufacturers, distributors, retailers and consumers, each of whom plays a role in the generation, use and disposal of soft plastics. However, achieving this can be a significant challenge, as stakeholders may have competing interests and priorities, making aligning efforts and implementing coordinated actions difficult. To address this issue, we propose appointing an independent, non-government and high-profile ‘transition broker’ to facilitate effective engagement between stakeholders and government so that a holistic and balanced supply chain for soft plastics can be developed and implemented (see ).

The action research conducted by Cramer provides valuable guidance on the governance of large-scale circular economy transitions in an industry sector (Cramer Citation2020). Introducing a formally appointed transition broker expedites the creation of a ‘coalition of the willing’ and facilitates the networking of key stakeholders. As Cramer (Citation2020, 2) rightly identifies, ‘[the transition brokers] were considered as trustworthy in their effort to build coalitions with parties that were willing to make transformative steps forward’. Given that the circular economy transition necessitates establishing and emerging a new regime, identifying the stakeholders who are prepared to tackle the required change is often necessary, and an independent broker can help build a new consortium of market actors (Cramer Citation2020).

The Nestle case study described in Box 1 exemplifies what a brokering role might represent. In this case, Nestle appointed one of its senior managers to assist in stakeholder negotiations to deliver supply chain proof of concept for recycling Nestle’s soft plastic packaging. This successful trial demonstrated the complexity of the transition required in the complete supply chain. The AFGC’s leading role in the National Plastics Recycling Scheme offers a similar approach to Nestle’s supply chain project (Paten Citation2023). The industry-led recycling scheme is trialling a circular plastics loop for hard-to-recycle soft plastics with funding from the National Product Stewardship Investment Fund. The project aims to recycle soft plastic packaging into food-grade material to create a true closed-loop system, and the AFGC has engaged a range of stakeholders across the supply chain (i.e. brand owners, manufacturers and recyclers) to partner and support the scheme (AFGC Citation2023). In this example, the AFGC could be considered the transition broker as its leadership has brought together a ‘coalition of the willing’ to develop a circular plastics loop for soft plastic packaging.

Box 1. Nestle KitKat Wrapper - Supply Chain Project. Source: LyondellBasell Australia (Citationn.d)

In 2020, Nestle initiated a supply chain project to validate that a wrapper for its KitKat brand could be produced with 30 per cent recycled plastic content. The intent was to support the achievement of the APCO target to achieve 30 per cent recycled packaging content by 2025 (DCCEEW Citationn.d.). Nestle established a coalition of supply chain partners to achieve this outcome in the Australian market and make the end-to-end process possible. Eight supply chain partners were involved in the pilot, from the collection of soft plastic waste streams to the manufacture of printed material (REDcycle, CurbCycle, iQ Renew, Licella, Viva Energy, LyondellBasell, Taghleef Industries and Amcor). Nestle’s report (Nestle, Citation2021) showed whilst this trial identified one option for using recycled soft plastic, it demonstrated the complexity and interdependence in the supply chain involved.

If the national government appointed a truly independent transition broker to facilitate stakeholder engagement during the soft plastic waste export ban, this broker could have facilitated and expedited a network of actors to address each stage of the supply chain that could have prevented the discontinuation of REDcycle. The transition broker could have addressed all possible uses of the soft plastic waste stream, not only as feedstock for soft plastic packaging with recycled content.

6.3. Policy and regulatory reforms required to create and scale local markets for soft plastics

To achieve a circular economy and in the wake of China’s strict regulations on waste imports, the integrated socio-technical framework emphasises the crucial need to create and expand local markets for recycled soft plastics. Unfortunately, this poses a significant challenge in Australia owing to the favourable economics of virgin plastic resins and inadequate market demand for recycled plastic materials. This discourages waste producers and recyclers from investing in recycling infrastructure and technologies. To overcome this issue, the country must find ways to stimulate a more robust market demand for recycled materials.

One effective method to encourage the use of recycled materials is implementing procurement policies prioritising recycled content. Financial incentives can also be offered to businesses that use recycled materials that might supply into procurement policies, while extended producer responsibility measures can facilitate recycling, thereby increasing the use of recycled materials. Promoting product labelling that highlights the environmental benefits of recycled products can also be effective.

Government-led initiatives, such as the Recycling Modernisation Fund and National Reconstruction Fund, can provide funding and support for developing recycling infrastructure and establishing viable markets for recycled plastics (DCCEEW Citation2023b; Department of Industry, Science and Resources Citation2022). This includes expanding recycling facilities and investing in advanced recycling technologies. Strategic investments in technology and waste management infrastructure, such as improving waste collection and sorting systems, are also necessary to overcome logistical and infrastructural challenges. Developing regional waste management hubs can also help address the challenges faced in remote areas by enabling efficient collection, processing and transportation of plastic waste.

Furthermore, instead of solely focusing on creating new markets, governments need to prioritise developing laws and policies with specific supply chain requirements. For instance, mandating a minimum of 70 per cent recycled soft plastics in plastic products would drive the collection and recovery of materials, leading to the development of innovative products. In cases where the cost of implementation is prohibitive, exploring alternative packaging solutions becomes essential. Thus, establishing a regulatory framework governance structure with clear rules and laws is indispensable in driving progress and achieving sufficient local markets for soft plastics in Australia.

7. Conclusion

Effective soft plastic waste governance in Australia requires various stakeholders to collaborate. The REDcycle programme is a compelling case study showcasing the potential of scalable solutions that incentivise sustainable practices throughout the supply chain. Despite significant obstacles, such as a complex supply chain and insufficient market demand for recycled materials, the programme remains a noteworthy example of managing plastic waste sustainably.

By drawing on an integrated socio-technical framework of actor-network theory and sustainability transitions theory to examine soft plastic governance in Australia, this paper highlighted the dynamics of the current soft plastic waste regime and its network of actors. For instance, the challenges faced by REDcycle can be attributed to the misalignment between the programme’s technical aspects and the social and political context in which it operated. The lack of adequate recycling infrastructure and local market demand adversely affected the programme. Reflecting on the REDcycle case, the integrated socio-technical perspective further provided a greater understanding of the key governance strategies for soft plastics to achieve a circular plastic economy.

Proposed solutions for effective soft plastic governance in Australia include implementing stricter waste reduction targets, improving waste collection and recycling infrastructure, and enforcing extended producer responsibility policies. The extended producer responsibility approach requires producers to manage their products’ entire lifecycle, encouraging environmentally friendly design and investment in recycling infrastructure. Expanding the scope of the Product Stewardship Act provides a solid foundation for effective extended producer responsibility implementation.

In addition to establishing new and updating existing regulatory frameworks, addressing the challenges of soft plastic recycling and promoting sustainable packaging practices is critical to plastic waste governance. Strategies to help this cause include exploring alternative packaging design standards, stakeholder collaboration, and further academic and industry research. Enhancing the collection system to maintain the highest value of these materials and promote their reintroduction into the circular system can also be a viable method.

Further funding for multidisciplinary research across academia, industry and the government is needed. In addition, embracing innovative models such as product-as-a-service and prioritising minimising overall plastic waste are essential steps towards sustainable resource utilisation. Lastly, critically examining recycling practices, re-evaluating concepts of circularity and market creation, and considering material limitations are crucial for optimal resource management.

Australia can move towards a more sustainable soft plastic governance system by addressing the challenges and implementing the proposed solutions. The plastic waste management industry can mitigate environmental impacts and promote a more sustainable future through collective responsibility, stakeholder collaboration, and a comprehensive approach. The REDcycle programme serves as a reminder that progress can be made with collaborative efforts and a comprehensive approach towards plastic waste governance.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Associate Professor Glen Croy, Professor Amrik Sohal and Professor Usha Iyer-Raniga, the coordinators of the Circular Economy Research Network Asia-Pacific (CERN-APac), as this paper has been developed resulting from a meeting held by CERN-APac’s Plastics and Packaging research stream.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Achenza, M. 2022. “Outrage as REDcycle Exposed for not Recycling Plastic Waste Collected by Customers.” News, November 9. https://www.news.com.au/technology/environment/sustainability/outrage-as-redcycle-exposed-for-not-recycling-plastic-waste-collected-by-customers/news-story/21526845ea1fac49319e1cda650a9487.

- Anguiano, D. 2022. “California Passes First Sweeping US Law to Reduce Single-Use Plastic.” The Guardian, July 1. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/jun/30/california-single-use-plastic-reduce-law-gavin-newsom.

- Arreza, J., and L. Hughson. 2023. “Packaging Waste Legislation: Environment Ministers Step In.” Packaging News, June 9. https://www.packagingnews.com.au/latest/packaging-waste-legislation-environment-ministers-step-in.

- Australian Food and Grocery Council (AFGC). 2023. “National Plastics Recycling Scheme.” https://www.afgc.org.au/industry-resources/national-plastics-recycling-scheme.

- Australian Packaging Covenant Organisation (APCO). 2019. “Soft Plastic Packaging Working Group 2018.” https://documents.packagingcovenant.org.au/public-documents/Soft%20Plastic%202018%20Working%20Group%20Key%20Findings.

- Australian Packaging Covenant Organisation (APCO). 2023. “Australasian Recycling Label Consumer Insights Report.” https://documents.packagingcovenant.org.au/public-documents/ARL%20Consumer%20Insights%20Report%202023.

- Borg, K., J. Lindsay, and J. Curtis. 2021. “When News Media and Social Media Meet: How Facebook Users Reacted to News Stories About a Supermarket Plastic Bag Ban.” New Media & Society 23 (12): 3574–3592. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820956681.

- Bousgas, A., and H. Johnson. 2023. “Australia’s Response to Plastic Packaging: Towards a Circular Economy for Plastics.” The Sydney Law Review 45 (3): 305–336.

- Cáceres Ruiz, A. M., and A. Zaman. 2022. “The Current State, Challenges, and Opportunities of Recycling Plastics in Western Australia.” Recycling (Basel) 7 (5): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling7050064.

- Callon, M., and J. Law. 1997. “After the Individual in Society: Lessons on Collectivity from Science, Technology and Society.” Canadian Journal of Sociology 22 (2): 165–182. https://doi.org/10.2307/3341747.

- Cassidy, C. 2022. “Environmental Watchdog Charges REDcycle Operators over Secret Soft Plastics Stockpiles.” The Guardian, December 23. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/dec/23/environmental-watchdog-charges-redcycle-operators-over-secret-soft-plastics-stockpiles.

- Cox, L. 2018. “Australians Mistakenly Throwing Soft Plastics into Recycling Bins, Survey Finds.” The Guardian, November 12. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/nov/12/australians-mistakenly-throwing-soft-plastics-into-recycling-bins-survey-finds.

- Cramer, J. 2020. “Practice-Based Model for Implementing Circular Economy: The Case of the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area.” Journal of Cleaner Production 255: 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120255.

- CSIRO. 2021. “Circular Economy Roadmap for Plastics, Glass, Paper and Tyres: Pathways for Unlocking Future Growth Opportunities for Australia.” https://www.csiro.au/en/research/natural-environment/Circular-Economy.

- de Jesus, A., and S. Mendonça. 2018. “Lost in Transition? Drivers and Barriers in the Eco-Innovation Road to the Circular Economy.” Ecological Economics 145: 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.08.001.

- Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and the Environment (DAFE). 2021. “National Plastics Plan.” https://www.agriculture.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/national-plastics-plan-2021.pdf.

- Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW). 2022a. “Waste Exports. https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/protection/waste/exports.”

- Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW). 2022b. “New Expert Group to Guide Australia’s Transition to a Circular Economy.” https://minister.dcceew.gov.au/plibersek/media-releases/new-expert-group-guide-australias-transition-circular-economy.

- Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW). 2023a. “Circular Economy Ministerial Advisory Group Meeting Communique.” https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/ministerial-advisory-group-meeting-2.pdf.

- Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW). 2023b. “Investing in Australia’s Waste and Recycling Infrastructure.” https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/protection/waste/how-we-manage-waste/recycling-modernisation-fund.

- Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW). n.d. “Australian Packaging Covenant Organisation.” https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/protection/waste/packaging/packaging-covenant.

- Department of Industry, Science and Resources. 2022. “National Reconstruction Fund: Diversifying and Transforming Australia’s Industry and Economy.” https://www.industry.gov.au/news/national-reconstruction-fund-diversifying-and-transforming-australias-industry-and-economy.

- Dilkes-Hoffman, L. S., S. Pratt, B. Laycock, P. Ashworth, and P. A. Lant. 2019. “Public Attitudes Towards Plastics.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 147: 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.05.005.

- European Commission. n.d. “EU Restrictions on Certain Single-Use Plastics.” https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/plastics/single-use-plastics/eu-restrictions-certain-single-use-plastics_en.

- Flynn, B., M. Pagell, and B. Fugate. 2020. “From the Editors: Introduction to the Emerging Discourse Incubator on the Topic of Emerging Approaches for Developing Supply Chain Management Theory.” Journal of Supply Chain Management 56 (2): 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12227.

- Geels, F. W. 2002. “Technological Transitions as Evolutionary Reconfiguration Processes: A Multi-Level Perspective and a Case-Study.” Research Policy 31 (8-9): 1257–1274. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00062-8.

- Geels, F. W., and J. Schot. 2007. “Typology of Sociotechnical Transition Pathways.” Research Policy 36 (3): 399–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2007.01.003.

- Government of Western Australia. 2024. “Western Australia’s Plan for Plastics.” https://www.wa.gov.au/service/environment/business-and-community-assistance/western-australias-plan-plastics.

- Govindan, K., and M. Hasanagic. 2018. “A Systematic Review on Drivers, Barriers, and Practices Towards Circular Economy: A Supply Chain Perspective.” International Journal of Production Research 56 (1−2): 278–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2017.1402141.

- Gredley, R. 2015. “How the REDcycle Program Makes Plastic Fantastic Using Recycled Products.” The Daily Telegraph, August 2. https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/how-the-redcycle-program-makes-plastic-fantastic-using-recycled-products/news-story/a1ffc4f4ce28cbdb4efd785d8990f26c.

- Hahladakis, J. N., and E. Iacovidou. 2018. “Closing the Loop on Plastic Packaging Materials: What is Quality and how Does it Affect Their Circularity?” The Science of the Total Environment 630: 1394–1400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.02.330.

- Hald, K. S., and M. Spring. 2023. “Actor-Network Theory: A Novel Approach to Supply Chain Management Theory Development.” Journal of Supply Chain Management 59 (2): 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12296.

- Hardesty, B. D., K. Willis, and J. Vince. 2022. “An Imperative to Focus the Plastic Pollution Problem on Place-Based Solutions.” Frontiers in Sustainability (Lausanne) 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2022.963432.

- Hebinck, A., G. Diercks, T. von Wirth, P. J. Beers, L. Barsties, S. Buchel, R. Greer, F. van Steenbergen, and D. Loorbach. 2022. “An Actionable Understanding of Societal Transitions: The X-Curve Framework.” Sustainability Science 17 (3), https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-01084-w.

- Hepplestone, S. 2017. “Are you a Little Unsure of How to Recycle? A Nunawading Couple have the Good Oil on How it’s Done.” Herald Sun, May 29. https://www.heraldsun.com.au/leader/east/are-you-a-little-unsure-of-how-to-recycle-a-nunawading-couple-have-the-good-oil-on-its-done/news-.

- Hina, M., C. Chauhan, P. Kaur, S. Kraus, and A. Dhir. 2022. “Drivers and Barriers of Circular Economy Business Models: Where we are now, and Where we are Heading.” Journal of Cleaner Production 333: 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.130049.

- Hogg, D., C. Durrant, A. Thomson, and C. Sherrington. 2018. Demand Recycled: Policy Options for Increasing the Demand for Post-Consumer Recycled Materials. Bristol, UK: Eunomia.

- Hossain, R., M. T. Islam, A. Ghose, and V. Sahajwalla. 2022. “Full Circle: Challenges and Prospects for Plastic Waste Management in Australia to Achieve Circular Economy.” Journal of Cleaner Production 368: 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133127.

- Hughson, L. 2022. “Industry Reels at REDcycle Suspension.” Packaging News, November 9. https://www.packagingnews.com.au/latest/industry-reels-at-redcycle-suspension.

- Jenkins, D. 2021. “Game-Changing Recycled Plastic Products Lead the Aussie Charge.” The Daily Telegraph, November 7. https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/technology/environment/gamechanging-recycled-plastic-products-lead-the-aussie-charge/news-story/2d1abfb3d2d204bb799a80a5c8c092ce.

- Johansen, M. R., T. B. Christensen, T. M. Ramos, and K. Syberg. 2022. “A Review of the Plastic Value Chain from a Circular Economy Perspective.” Journal of Environmental Management 302 (113975): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113975.

- Jolly, P. 2023. “Soft Plastics Update: Major Supermarkets Agree on a Soft Plastics Recycling Road Map.” Business Recycling Planet Ark, March 16. https://businessrecycling.com.au/news/display/soft-plastics-update-major-supermarkets-agree-on-a-soft-plastics-recycling.

- Jones, S. 2020. “Establishing Political Priority for Regulatory Interventions in Waste Management in Australia.” Australian Journal of Political Science 55 (2): 211–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2019.1706721.

- Jones, S., and B. W. Head. 2023. “The Limits of Voluntary Measures: Packaging the Plastic Pollution Problem in Australia.” Australian Journal of Public Administration, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12614.

- Judd, B. 2023. “Australia is Phasing Out Single-Use Plastics - But what Items and when Depends on where you Live.” ABC News, July 31. https://www.abc.net.au/news/science/2023-07-31/war-on-waste-single-use-plastics-states-territories/102554268.

- Kasell, L. 2023. “REDcycle’s Liz Kasell Speaks Out.” Packaging News, March 1. https://www.packagingnews.com.au/latest/opinion-redcycle-s-liz-kasell-speaks-out.

- Kirwan, M. J., S. Plant, and J. W. Strawbridge. 2011. “Plastics in Food Packaging.” In Food and Beverage Packaging Technology, edited by R. Coles and M. Kirwan, 2nd ed., 157–212. Chichester, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Köhler, J., F. W. Geels, F. Kern, J. Markard, E. Onsongo, A. Wieczorek, F. Alkemade, et al. 2019. “An Agenda for Sustainability Transitions Research: State of the Art and Future Directions.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 31: 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.01.004.

- Korycki, L. 2024. “Soft Plastics Recycling Trial Starts in 12 Melbourne Suburbs.” Waste Management Review, February 12. https://wastemanagementreview.com.au/soft-plastics-recycling-trial-starts-in-12-melbourne-suburbs/.

- Lane, R., A. Kronsell, D. Reynolds, R. Raven, and J. Lindsay. 2023. “Role of Local Governments and Households in Low-Waste City Transitions.” https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4549648

- Latour, B. 1987. Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers Through Society. Cambridge, US: Harvard University Press.

- Latour, B. 1992. “Where are the Missing Masses? The Sociology of a Few Mundane Artifacts.” In Shaping Technology/Building Society: Studies in Sociotechnical Change, edited by W. E. Bijker and J. Law, 225–258. Cambridge, US: MIT Press.

- Latour, B. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor Network-Theory. New York, US: Oxford University Press.

- Leterme, S. C., E. M. Tuuri, W. J. Drummond, R. Jones, and J. R. Gascooke. 2023. “Microplastics in Urban Freshwater Streams in Adelaide, Australia: A Source of Plastic Pollution in the Gulf St Vincent.” The Science of the Total Environment 856 (158672): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158672.

- Lewis, D. 2017. “‘Recycling in Australia is Dead in the Water’: Three Companies Tackling our Plastic Addiction.” The Guardian, May 22. https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2017/may/22/recycling-in-australia-is-dead-in-the-water-three-companies-tackling-our-plastic-addiction.

- Local Government Association of South Australia. 2023. “Parliament of South Australia – Inquiry into the Recycling of Soft Plastics and Other Recyclable Material: LGA Response.” https://www.lga.sa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0036/1487664/LGA-Response-Parliamentary-Inquiry-into-Recycling-of-Soft-Plastics.pdf.

- Lockrey, S., H. Millicer, R. Collins, L. Fennessy, M. Richardson, T. Rajaratnam, A. Hill, et al. 2022. “Enabling Design for Environmental Good Sub Report: Buildings Sector.” DCCEEW. https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/enabling-design-environmental-good-sub-report-buildings_0.pdf.

- LyondellBasell Australia. n.d. LyondellBasell Australia Collaborates to Create Food Packaging Prototype with Recycled Content. https://www.lyondellbasell.com/en/news-events/advancing-possible/lyondellbasell-australia-collaborates-to-create-food-packaging-prototype-with-recycled-content/

- Macintosh, A., A. Simpson, T. Neeman, and K. Dickson. 2020. “Plastic Bag Bans: Lessons from the Australian Capital Territory.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 154 (104638): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104638.

- Macklin, J., and E. Dominish. 2018. “China’s Recycling ‘Ban’ Throws Australia into a Very Messy Waste Crisis.” The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/chinas-recycling-ban-throws-australia-into-a-very-messy-waste-crisis-95522.

- Malcolm, J. 2022. “Call for Urgent Action on Recycling Fail.” The Australian, November 29.

- Mathews, J. A., and H. Tan. 2011. “Progress Toward a Circular Economy in China: The Drivers (and Inhibitors) of eco-Industrial Initiative.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 15 (3): 435–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-9290.2011.00332.x.

- Michael, M. 2017. Actor Network Theory: Trials, Trails and Translations. London, UK: SAGE Publications.

- Minderoo. 2023. “Plastic Waste Makers Index.” https://www.minderoo.org/plastic-waste-makers-index/.

- Murray-Atfield, Y. 2023. “Coles and Woolworths Offer to Take on Tonnes of Soft Plastic after REDcycle Collapse.” ABC News, February 24. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-02-24/supermarkets-offer-to-store-soft-plastics-redcycle-collapse/102017410.

- Nestle. 2021. “The Wrap on Soft Plastics.” https://www.nestle.com.au/en/media/kitkat-sign-break-australias-waste-challenge.

- Neuman, W. L. 2014. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 7th ed. Essex, UK: Pearson.

- Niero, M., C. L. Jensen, C. F. Fratini, J. Dorland, M. S. Jørgensen, and S. Georg. 2021. “Is Life Cycle Assessment Enough to Address Unintended Side Effects from Circular Economy Initiatives?” Journal of Industrial Ecology 25 (5): 1111–1120. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.13134.

- Paten, S. 2023. “AFGC Takes on Soft Plastics Recycling.” Waste Management Review, May 8. https://wastemanagementreview.com.au/afgc-takes-on-soft-plastics-recycling/.

- Phelan, A. 2022. “REDcycle’s Collapse is More Proof that Plastic Recycling is a Broken System.” The Conversation, November 17. https://theconversation.com/redcycles-collapse-is-more-proof-that-plastic-recycling-is-a-broken-system-194528.

- Ramirez, R., and T. Romine. 2022. “Single-Use Plastic Waste is Getting Phased Out in California under a Sweeping New Law.” CNN, July 1. https://edition.cnn.com/2022/07/01/us/california-plastic-law-climate/index.html.

- Reddy, S., and W. Lau. 2020. “Breaking the Plastic Waste: Top Findings for Preventing Plastic Pollution.” July 23. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2020/07/23/breaking-the-plastic-wave-top-findings.

- Schandl, H., S. King, A. Walton, A. Kaksonen, S. Tapsuwan, and T. Baynes. 2021. Circular Economy Roadmap for Plastics, Glass, Paper and Tyres—Pathways for Unlocking Future Growth Opportunities for Australia. Canberra, Australia: CSIRO Publishing.

- Siderius, T., and T. Zink. 2022. “Markets and the Future of the Circular Economy.” Circular Economy and Sustainability (Online) 3 (3): 1569–1595. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-022-00196-4.

- Silvério, A. C., J. Ferreira, P. O. Fernandes, and M. Dabić. 2023. “How Does Circular Economy Work in Industry? Strategies, Opportunities, and Trends in Scholarly Literature.” Journal of Cleaner Production 412: 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137312.

- Topsfield, J. 2018. “The Number One Recycling Mistake Australians are Still Making.” The Sydney Morning Herald, November 11. https://www.smh.com.au/environment/sustainability/the-number-one-recycling-mistake-australians-are-still-making-20181111-p50fc4.html.

- Towell, N. 2021. 'Circular Economy’ Revolution Could be Worth $2 Trillion. The Sydney Morning Herald, March 23. https://www.smh.com.au/business/workplace/circular-economy-revolution-could-be-worth-2-trillion-20210323-p57d5a.html.

- United Nations Environment Programme. 2021. “Policy Options to Eliminate Additional Marine Plastic Litter.” https://www.resourcepanel.org/reports/policy-options-eliminate-additional-marine-plastic-litter.

- United Nations Environment Programme. 2022. “Historic Day in the Campaign to Beat Plastic Pollution: Nations Commit to Develop a Legally Binding Agreement.” March 2. https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/historic-day-campaign-beat-plastic-pollution-nations-commit-develop.

- Vallecha, H., and P. Bhola. 2019. “Sustainability and Replicability Framework: Actor Network Theory Based Critical Case Analysis of Renewable Community Energy Projects in India.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 108: 194–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.03.053.

- Vedelago, C. 2022. “‘Not what was Advertised’: Supermarket Plastic Bag Recycling Program Began to Fail in 2018.” The Sydney Morning Herald, November 26. https://www.smh.com.au/national/not-what-was-advertised-supermarket-plastic-bag-recycling-program-began-to-fail-in-2018-20221122-p5c0hl.html.

- Vedelago, C. 2023. “Millions of Plastic Bags Go to Landfill as Recycling Scheme Restart Hit by Delays.” The Sydney Morning Herald, February 12. https://www.smh.com.au/national/millions-more-plastic-bags-bound-for-landfill-unless-recycling-scheme-can-restart-20230131-p5cgqu.html.