ABSTRACT

The implementation of fauna-sensitive road design has the potential to mitigate negative impacts on wildlife caused by roads. However, our previous international review found adoption of fauna-sensitive road design has been limited at the level of transport planning, even in nations that mandate this. In Australia, where the adoption of fauna-sensitive road design is still in its early stages, a review of 57 peer-reviewed papers revealed that transport practitioners generally have not acknowledged or considered fauna-sensitive road design measures or road ecology concepts. This lack of consideration is due to deeply rooted economic interests and attitudes institutionalised within the industry. While the development of fauna-sensitive road design is possible in the Australian transport sector, a substantial institutional change driven by appropriate policies and user experiences is necessary. We recommend future studies explore practitioner experience to better understand the conditions that facilitated the voluntary adoption of fauna-sensitive road design policies in two Australian states.

1. Rationale

The evolving discipline of road ecology, encompassing the study of various road elements such as vehicles, soil, water, air, plants and wildlife, strives to mitigate the adverse impacts of linear transport infrastructure on fauna (van der Ree, Smith, and Grilo Citation2015). In parallel, endeavours to address the impact of linear transport infrastructure on wildlife have given rise to the widespread adoption of fauna-sensitive road design (FSRD) – green infrastructure that integrates diverse wildlife crossing structures, including ecoducts, land/green bridges, wildlife overpasses, canopy bridges, glider poles, underpasses and modified culverts, to facilitate safe wildlife movement across fragmented habitats intersected by linear transport infrastructure. Demonstrating effectiveness globally, these structures are designed not only to sustain landscape connectivity but also to enhance road safety, reducing wildlife-traffic collisions and associated costs (Jones et al. Citation2011; Jones and Pickvance Citation2013; Wilson, Marsh, and Winter Citation2007). Consequently, this has stimulated the implementation of policy measures such as green networks, wildlife corridors and defragmentation programmes, particularly within European Union member states (Damarad and Bekker Citation2003; Iuell Citation2003; van der Ree, Smith, and Grilo Citation2015).

The implementation of these frameworks has sparked notable research interest, evident in studies by Ledoux et al. (Citation2000), Diaz (Citation2001), Morris (Citation2011) and Papp et al. (Citation2022). However, our recent systematic review has brought to light a limited global consideration of both fauna movement and FSRD in transport planning research (Johnson et al. Citation2022a). Notably, only around 12 per cent of published research addressing the application of environmental policies in transport projects originated from outside the European Union (see Johnson et al. Citation2022a). This poses a significant challenge, given the highly variable impacts of roads on landscapes, necessitating tailor-made measures for the effective and impactful implementation of FSRD (Iuell Citation2003; van der Ree, Smith, and Grilo Citation2015).

Effective policy implementation in this domain hinges on a robust regulatory framework as emphasised by practices in some European Union member states (Damarad and Bekker Citation2003; Jones and Pickvance Citation2013; Wilson, Marsh, and Winter Citation2007). Although analogous policies have been introduced to a more limited extent by transport infrastructure agencies in Australia (Veith et al. Citation2015; TMR Citation2000, Citation2010; VicRoads Citation2012), Australia’s regulatory approach to the management of transport infrastructure environmental outcomes is frequently criticised as inadequate (Byrne, Snipe, and Dodson Citation2014; Macintosh et al. Citation2018; Rieder Citation2011; Tridgell Citation2013). To gauge the extent to which FSRD measures have been considered in Australian transport planning, still in its early stages of adoption, we conducted a systematic literature review using frameworks presented in Pickering and Byrne (Citation2014) and De Vos and El-Geneidy (Citation2022). The focus of the review is on Australia, guided by the question: To what degree are FSRD measures acknowledged and considered in transport planning, as evidenced by the peer-reviewed literature? Due to a lack of information in this area, this review does not consider or explore the outcomes of applying policy directives.

2. Background

The application of the ecologically sustainable development principle in Australia is marked by a lack of clarity and guidance for practitioners in their decision-making processes (England Citation2005; England Citation2006a, Citation2006b; Meurling Citation2005; Summerville, Adkins, and Kendall Citation2008). Instead, there is a strong emphasis on regulating ecologically sustainable development through community behaviour and democratic principles such as community rights and responsibilities (Summerville, Adkins, and Kendall Citation2008). This approach has led to the adoption of passive environmental policies, introducing ambiguity in their interpretation and providing significant discretion in policy options considered during the decision-making process (England Citation2015, Citation2016; Fisher Citation2001b). Decision makers in numerous Australian states and territories are only obligated to ‘have regard to’ or ‘consider’ environmental policies in environmental impact assessment (England Citation2010; Fisher Citation2001a; Ives et al. Citation2010; McGrath Citation2014). This complexity is further compounded by the limited definition of significant impact and likelihood of significant impact (Fisher Citation2000; Macintosh Citation2004; Stein Citation2000; Williams and Williams Citation2016). Consequently, when implementing environmental management programmes, decision makers have often prioritised procedural correctness over tailoring approaches to ensure the intended outcomes are achieved (Clement, Moore, and Lockwood Citation2015; Fisher Citation2005; Wright Citation2001).

In Australia, political and economic interests significantly influence infrastructure and transportation provision, often prioritising economic development over environmental sustainability and management (Austin Citation2000; Caulfield Citation1993; Curran Citation2015; Hu Citation2015). This tendency is evident in the implementation of various biodiversity management plans and initiatives such as the Back on Track species prioritisation framework, the Tasmanian Midlands Water Strategy and the Plan of Management for Kosciuszko National Park, which emphasises cost-effective and orderly implementation without undermining state/territory rights or ownership (Clement, Moore, and Lockwood Citation2015; Kim et al. Citation2016). This is reflective of a broader approach by the Australian Government to regulate environmental management and planning through economic instruments, exemplified by the ‘one-stop-shop’ policy aimed at achieving faster, short-term economic gains and administrative efficiency (Brown and Nitz Citation2000; England Citation2010; Jaireth and Figg Citation2014; Moon Citation1998; Young and Gray Citation2000).

Despite the intended benefits, these initiatives have adversely impacted the transparency, accountability and quality of the environmental impact assessment process, resulting in delays in project evaluations and limitations on applications (England Citation2010). Moreover, the mitigation hierarchy – an essential tool in environmental impact assessment aimed at minimising environmental damage through a sequence of avoidance, mitigation and offsetting – has encountered challenges due to the limited capacity of decision makers to accurately assess environmental significance in infrastructure projects. This challenge is further exacerbated by the duplication of environmental impact assessment provisions across different legislations and government levels (England Citation2010; Marsden and Ashe Citation2006; Williams and Williams Citation2016).

The need for a comprehensive review of FSRD policies is evident given the expansive Australian road transport network, which covers approximately 880,000 km (with ∼427,000 km paved), and the substantial annual investments from all levels of government, totalling AUD 36 billion (BITRE Citation2020; WorldData Citation2024). This review will provide valuable insights into the acknowledgement and consideration of road ecology principles and FSRD measures in transport planning, which have played a crucial role in improving transportation infrastructure worldwide. Furthermore, this review will pave the way for future research and inform local – and state-level government planning priorities, policies and legislation.

3. Methods

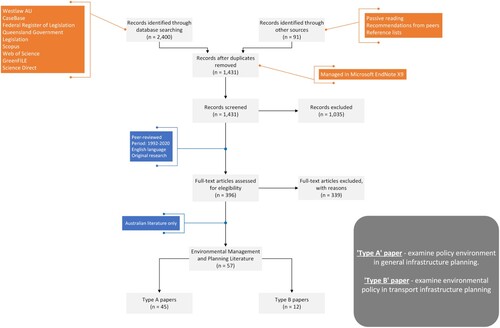

The present study adopted the Pickering and Byrne model (Citation2014) for systematic quantitative literature review, which was modified to align with the PRISMA-P guideline (Moher et al. Citation2009) and the recommendations of De Vos and El-Geneidy (Citation2022). The latter provides a valuable approach to crafting a review that offers meaningful contributions to the transportation field. Specifically, the framework underscores the importance of demonstrating ‘added value’ by either constructing a conceptual model, pinpointing avenues for future research or examining policy insights and implications. For this study, the focus will be on the latter two aspects.

A literature search, using 143 keyword searches, was conducted across eight journal databases to identify peer-reviewed articles related to environmental management and planning (see supplementary material). This search focused on the implementation and operation of key environmental legislation and policies without necessarily concentrating on the on-the-ground implementation of FSRD. The search was limited to the period after the Earth Summit (1992–2021) when legally binding goals for sustainable development came into existence. The search only included peer-reviewed literature to ensure scientific rigor, and grey literature such as reports, statutes and books were intentionally excluded under the assumption that they were indirectly captured and expanded upon in scientific texts. This methodology is consistent with that used by Johnson et al. (Citation2022b). Following the removal of duplicate records, the articles were classified into two types, namely Type A and Type B papers, based on their content. Type A papers were concerned with environmental policy in infrastructure planning generally, while Type B papers examined environmental policies in transport infrastructure planning ().

4. Results

A substantial number of individual search attempts (143) yielded 2,400 peer-reviewed articles. A further 91 articles were obtained by other means, such as contributions of peers and searches of article reference lists. Once all duplicates and peripheral (i.e. non-relevant) articles were removed, only 57 articles remained for quantitative analysis. Following reclassification, 45 Type A papers and 12 Type B papers were identified.

The combined dataset of Type A and B papers displayed a significant geographic bias towards certain regions within Australia. Specifically, Queensland was the focus of approximately 36 per cent of all studies (n = 21), while Victoria (n = 4) and other Australian states/territories (n = 5) received relatively little attention. Moreover, about 32 per cent of the articles analysed examined policies at the national (Australian) level.

Around 75 per cent of papers (Type A and B) employed statutory analysis and/or policy operation as their methodological approach, with a majority focusing on broader environmental legislation and/or policy, particularly the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. Only one article in the reviewed literature explored the content of Australian transport policies and used interviews/surveys of practitioners in its methodological approach. None of the reviewed articles incorporated case studies (i.e. specific real-world applications).

The way in which Type-B papers referenced environmental concerns sheds light on practitioners’ understanding of environmental concepts. The most frequently mentioned environmental concerns were broad and non-specific, including the environment (n = 6), biodiversity (n = 5) and pollution/contamination (n = 5). Only one paper acknowledged fauna movement, and none of the reviewed Type-B papers recognised habitat quality, habitat fragmentation or wildlife-vehicle collisions.

In transport research, resistance towards addressing environmental concerns in policy was found to be primarily due to various factors. Policy misinterpretation (i.e. incorrect understanding and/or application of policy) was cited in seven instances, while conflicted knowledge and political interests (i.e. individual, sector and/or political motivations that run counter to FSRD) were identified as factors in six and five cases, respectively. Regulatory power was also a significant factor, with statutory recognition cited in six instances and statutory confinement (i.e. the extent to which policies may be applicable) in four. Other factors included procedural focus, which was identified in four cases, and poor assessment/monitoring, which was cited in four instances.

5. Discussion

The main finding of this study was that FSRD has not been widely acknowledged in the body of peer-reviewed literature (i.e. published research) focused on Australia. This is concerning because road ecology, which encompasses wildlife biology, engineering and natural areas management, is crucial for sustainable transportation planning. FSRD provides a framework for ecological planning, engineering and mitigation in road transport projects (van der Ree, Smith, and Grilo Citation2015). In regions like the EU, acknowledging the environmental impacts of roads, particularly on wildlife, in peer-reviewed literature has significantly improved their consideration in transport planning (Damarad and Bekker Citation2003; Iuell Citation2003; Johnson et al. Citation2022b).

Australia’s extensive road network, which interacts with many sensitive landscapes, has the potential to make significant positive contributions to public greenspace and the conservation of biodiversity (Chang, Bertola, and Hoskin Citation2023; Hamer, Harrison, and Stokeld Citation2016; Marshall, Grose, and Williams Citation2019; Munro, Williamson, and Fuller Citation2018). However, most research on this topic has been from an ecological perspective (Hall et al. Citation2018; Hawkins, Ritrovato, and Swaddle Citation2020; Johnson, Evans, and Jones Citation2017; Goldingay et al. Citation2018), with few studies critically examining environmental policies within transport departments and institutions.

A poor understanding and recognition of road impacts in legal documents and policy guidelines can leave transport planners ill-equipped to address ecologically sensitive areas, engage stakeholders, secure funding and implement effective mitigation strategies (Papp et al. Citation2022). The only known critique of transport policies in the Australian transport sector, which also examined environmental aspects, was conducted by Bray, Taylor, and Scrafton (Citation2011), in which 43 urban transport strategies, published between 1965 and 2010, were reviewed. Several key issues were highlighted, including:

Similar policies were observed across states and territories, but there was little evidence of critical evaluation of these policies.

Recent strategies tended to feature ‘soft’ and ‘aspirational’ policies rather than evidence-based, demand-driven policies prominent in earlier strategies.

Environmental consequences of transport infrastructure were addressed only in more recent strategies, focusing mainly on greenhouse gas emissions.

These observations align with the present study’s results, where broader environmental concerns dominated the literature.

6. The legislative framework for fauna-sensitive road design in Australia

The implementation of FSRD measures in national road transport infrastructure projects is limited by the lack of legislative support in current landscape management policies. Few projects meet the criteria for Commonwealth assessment, making national-level implementation of FSRD unlikely (Field, Burns, and Dale Citation2012; Kennedy et al. Citation2001; Macintosh Citation2004). When a road project does qualify for assessment, there is limited scope for considering FSRD measures due to the weak and ineffective mandate for environmental impact assessment in the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commins Citation1993; Lindsay and Trezise Citation2016; Tridgell Citation2013).

The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 allows the Commonwealth to consider impacts on threatened species and ecological communities within the project area (Chapple Citation2001; Clement, Moore, and Lockwood Citation2015; Godden and Peel Citation2007; Macintosh Citation2004). However, the Act’s definitions of significant impact and the likelihood of significant impact are poorly defined, complicating the assessment of a project’s overall impact (England Citation1999; Hardman Citation2003; McGrath Citation2004; Williams and Williams Citation2016). Additionally, the Act does not account for cumulative impacts or suitable alternatives for development, which are better addressed through strategic environmental assessment (Hawke Citation2009; Marsden Citation2013; Samuel Citation2020). In Australia, impacts are typically assessed at the project level, with strategic environmental assessment being voluntary and limited to Matters of National Environmental Significance and Matters of State Environmental Significance at the federal level (Kabir, Momtaz, and Morgan Citation2020; Macintosh Citation2004; Marsden and Ashe Citation2006). This contrasts with FSRD, which emphasises the need to consider species within a broader landscape context (van der Ree, Smith, and Grilo Citation2015), unlike the project-specific focus currently adopted in environmental impact assessment (Hawke Citation2009; Samuel Citation2020).

Additionally, the effective implementation of environmental impact assessment relies on access to accurate species and ecosystem information by project planners and assessment managers (Fraser et al. Citation2019; Simmonds et al. Citation2019). However, recovery, threat abatement and conservation plans suffer from several inadequacies: (1) a significant time gap between species listing and plan publication, (2) inconsistent measures for mitigating identified threats and (3) ineffective criteria for evaluating performance (Lindsay and Trezise Citation2016; Ortega-Argueta, Baxter, and Hockings Citation2011). These plans offer only guidance and are enforceable only if incorporated into approval conditions (Lindsay and Trezise Citation2016). Two statutory reviews of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, Hawke (Citation2009) and Samuel (Citation2020), recommended addressing these shortcomings, but implementation has yet to occur. Consequently, the Commonwealth’s capacity to mitigate project impacts on threatened species and ecological communities remains limited (Simmonds et al. Citation2019).

State and territory governments, primarily responsible for land-use and landscape management, often lack the capacity to consider FSRD policy measures (Clement, Moore, and Lockwood Citation2015; Grant and Papadakis Citation2004; Gurran, Gilbert, and Phibbs Citation2015; Sollberger Citation2006). Similar to the Commonwealth, inconsistencies in conservation and land-use management legislation are prevalent (Clement, Moore, and Lockwood Citation2015; Simmonds et al. Citation2019), with many states prioritising the economic benefits of infrastructure projects (Boge Citation2017; England Citation2015; Gleeson and Low Citation2000).

Queensland, which featured prominently in the present study, exemplifies this issue with its history of turbulent land-use management and emphasis on microeconomic reform since the early 1990s (England Citation2010; England and McInerney Citation2017; Homel Citation1999; Williams and Williams Citation2016). The introduction of the Planning Act 2016 further shifted procedural matters to separate regulations and non-mandatory best practice guidelines (England Citation2015; Citation2016). These changes gave decision makers discretionary powers to choose which non-mandatory guidelines, like environmental impact assessment, to consider in infrastructure assessments (England Citation2015, Citation2016; Field, Burns, and Dale Citation2012; Williams and Williams Citation2016). FSRD in Queensland also exists as a non-mandatory administrative guideline, similar to environmental impact assessment (TMR Citation2010).

Victoria has a non-mandatory FSRD guideline (VicRoads Citation2012) similar to Queensland’s, likely due to knowledge transfer between the two states, akin to the spread of transport strategies described by Bray, Taylor, and Scrafton (Citation2011). However, due to limited published literature on transport and environmental policy, it is unclear how the Victorian FSRD guideline is applied in infrastructure projects, as noted in this study.

7. Implications and future directions

This systematic review found that, although FSRD guidelines have been in place in Australia, at the state level, for over a decade, road ecology and FSRD are not widely acknowledged or considered in road transport infrastructure planning. Two recent studies, Johnson et al. (Citation2022b) and Papp et al. (Citation2022), provided useful insights into the current and emerging practices of FSRD on a broader scale. This study offers a more nuanced approach to FSRD in Australia, a large and economically advanced country with few publicly available FSRD policies and a history of substandard landscape management. Indeed, it is the first study of its kind in Australia.

Australia’s FSRD guidelines are largely symbolic and carry little weight in the decision-making process. They exist solely as non-mandatory administrative guidelines, within two states, making them susceptible to exclusion due to the numerous exemptions and discretionary powers granted by statutes. Even when FSRD guidelines are considered by decision makers, achieving meaningful conservation outcomes is challenging as environmental planning in Australia is deficient both in language and content, characterised by flawed planning, monitoring and management practices. Additionally, the administration of Australia’s sustainability principles through passive and ambiguous regulation has allowed economic interests and attitudes to proliferate and become entrenched. For example, ecologically sustainable development is a principle that many Australian governments strive for but have trouble achieving due to the significant discretionary powers afforded to policy- and decision-makers, compounded by limited definition and guidance of key terminologies such as ‘significant impact’ and ‘likelihood of significant impact’.

Developing linear transport infrastructure that meets ecologically sustainable development principles requires dialogue and cooperation between departments. Road ecology plays a crucial role in this process, combining research insights and industry best practices from various disciplines such as wildlife biology and road engineering. By fostering interdisciplinary collaboration, road ecology can help bridge the gap between environmental sustainability and infrastructure development, ensuring that conservation goals are integrated into the planning and implementation of road projects.

The current study acknowledges certain limitations that warrant acknowledgment. Firstly, it is essential to recognise the confined scope of the research, which specifically targeted Australian published literature. While some may view this as a limitation, we contend that it serves as a strength for the study. As discussed earlier, the intricate and diverse nature of the relationship between roads and landscapes makes FSRD implementation challenging, necessitating a foundational understanding of the policy environments in the regions in which they operate. The present review establishes a baseline for the Australian context, introducing new insights that complement broader-scale analyses available in other regions (see Johnson et al. Citation2022a and Papp et al. Citation2022). Additionally, we assert that the chosen keyword strings were sufficiently broad to encompass all peer-reviewed literature pertinent to this topic, aligning with the typical approach adopted by road transport planners in Australia.

Secondly, the study did not evaluate the degree to which Australian environmental and FSRD policies have been incorporated into transportation infrastructure policy and planning. Although this was beyond the scope of the review and such information may reside in the grey literature (see Bray, Taylor, and Scrafton Citation2011), it raises concerns about the level of integration, particularly given the issues with environmental legislation in Australia, especially concerning development referrals and approvals. Additionally, the limited scope of policy learning within and between government institutions, as noted by Bray, Taylor, and Scrafton (Citation2011), may explain why FSRD in Australia currently exists only as non-mandatory best practice guidelines in two states.

Further exploration into the factors facilitating the acceptance and integration of FSRD in Australia is imperative. Employing a mixed-methods approach, which utilises linguistic analytical tools and incorporates follow-up interviews with transport practitioners, can effectively scrutinise FSRD policy. This action-oriented methodology, proven successful in assessing biodiversity conservation policies in Australia (see Clement, Moore, and Lockwood Citation2015), holds considerable value for transport practitioners. In addition to gauging the knowledge and experience of policy and decision makers regarding FSRD policies, this approach would shed light on:

The conditions that facilitated the incorporation of FSRD from road ecology concepts and research into the transport sectors of Australian states and territories.

Areas that could be further developed to enhance the practical implementation of FSRD measures.

Roads divide habitats and impede wildlife movement, but the judicious application of FSRD interventions can mitigate such impacts. Although FSRD implementation is still in its early stages, there is substantial potential for its adoption in the Australian transport sector. Achieving effective institutional change requires supportive policies and practical user experiences, an area where Australia currently lags behind other advanced nations. Nonetheless, valuable lessons can be gleaned from the experiences of other countries in implementing FSRD, providing insights that can contribute to a more successful adoption and implementation of the approach in Australia.

Author contributions

Conceived the systematic quantitative literature review: CJ, TM. Performed the systematic quantitative literature review: CJ. Analysed the data: CJ. Contributed materials/critique/analysis tools: CJ, TM, MB and DJ. Wrote, formatted and edited the paper: CJ, TM, MB, and DJ.

SQLR-Reference-Matrix.xlsx

Download MS Excel (88.6 KB)Acknowledgments

Special thanks go to Daryl Evans for their valuable insight and contributions toward data analysis and comments. Thanks also to Dan Pagotto, Alexandra White and Maree Hume for their assistance in reviewing the systematic quantitative literature review database search methodology. I am also grateful to the academic reviewers whose valuable comments helped to improve the quality of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Austin, M. 2000. “New State Development Legislation Implications for Infrastructure Development, Environmental Assessment and Integrated Planning in Queensland.” Local Government Law Journal 3:239–247.

- Boge, C. 2017. “Public Roads in Queensland: Where Statute and the Common Law Intersect – Parts 1.” The Queensland Lawyer 37:26–52.

- Bray, D. J., M. A. P. Taylor, and D. Scrafton. 2011. “Transport Policy in Australia—Evolution, Learning and Policy Transfer.” Transport Policy 18 (3): 522–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2010.10.005.

- Brown, L., and T. Nitz. 2000. “Where Have All the EIAs Gone?” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 17 (2): 89–98.

- Bureau of Infrastructure and Transport Research Economics (BITRE). 2020. Key Australian Infrastructure Statistics 2020. Canberra, ACT.

- Byrne, J., N. Sipe, and J. Dodson. 2014. Australian Environmental Planning: Challenges and Future Prospects, 23–28. Abingdon, OX: Routledge.

- Caulfield, J. 1993. “Responses to Growth in the Sun-Belt State – Planning and Coordinating Policy Initiatives in Queensland.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 52 (4): 431–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8500.1993.tb00298.x.

- Chang, Y., L. V. Bertola, and C. J. Hoskin. 2023. “Species Distribution Modelling of the Endangered Mahogany Glider (Petaurus Gracilis) Reveals key Areas for Targeted Survey and Conservation.” Austral Ecology 289–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/aec.13266.

- Chapple, S. 2001. “The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth): One Year Later.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 18 (6): 523–539.

- Clement, S., S. A. Moore, and M. Lockwood. 2015. “Authority, Responsibility and Process in Australian Biodiversity Policy.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 32 (2): 93–114.

- Commins, I. 1993. “Biodiversity – Legal Implications for Australia.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 10: 486–498.

- Curran, G. 2015. “Political Modernisation for Ecologically Sustainable Development in Australia.” Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 22 (1): 7–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14486563.2014.999359.

- Damarad, T., and G. J. Bekker. 2003. COST 341 - Habitat Fragmentation due to Transportation Infrastructure: Findings of the COST Action 341. Office for official publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg.

- De Vos, J., and A. El-Geneidy. 2022. “What is a Good Transport Review Paper?” Transport Reviews 42 (1): 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2021.2001996.

- Diaz, C. L. 2001. “The EC Habitats Directive Approaches its Tenth Anniversary: An Overview.” Review of European Community and International Environmental Law 10 (3): 287–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9388.00288.

- England, P. 1999. “Toolbox or Tightrope? The Status of Environmental Protection in Queensland's Integrated Planning Act.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 16 (2): 124–139.

- England, P. 2005. “Judicial Interpretation of Planning Schemes Under the Integrated Planning Act 1997 (Qld): The More Things Change.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 22:281–295.

- England, P. 2006a. “Flexibility or Restraint? Interpreting Queensland’s Performance Based Planning Schemes.” Local Government Law Journal 11:209–2018.

- England, P. 2006b. “IPA Planning Schemes: Is There a Difference?” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 23:81–99.

- England, P. 2010. “From Revolution to Evolution: Two Decades of Planning in Queensland.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 27:53–68.

- England, P. 2015. “Regulatory Obesity, the Newman Diet and Outcomes for Planning law in Queensland.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 32: 60–70.

- England, P. 2016. “Planning and Development Dilemmas in a Minority Government: Restoring Community or Held to Ransom?” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 33:31–46.

- England, P., and A. McInerney. 2017. “Anything Goes? Performance-Based Planning and the Slippery Slope in Queensland Planning law.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 34:238–250.

- Field, G., G. L. Burns, and P. Dale. 2012. “Managing Vegetation Clearing in the South East Queensland Urban Footprint.” Local Government Law Journal 17: 215–230.

- Fisher, D. 2000. “Considerations, Principles and Objectives in Environmental Management in Australia.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 17 (6): 487–501.

- Fisher, D. 2001a. “Environmental Impact Assessment in Queensland.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 18:2.

- Fisher, D. 2001b. “Sustainability – the Principle, its Implementation and its Enforcement.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 13 (4): 361–368.

- Fisher, D. 2005. “The South-East Queensland Regional Plan – A New Planning Approach for Queensland.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 22:89–95.

- Fraser, H., J. S. Simmonds, A. S. Kutt, and M. Maron. 2019. “Systematic Definition of Threatened Fauna Communities is Critical to Their Conservation.” Diversity and Distributions 25 (3): 462–477. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12875.

- Gleeson, B., and N. Low. 2000. “Revaluing Planning: Rolling Back neo-Liberalism in Australia.” Progress in Planning 53 (2): 83–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-9006(99)00022-7.

- Godden, L., and J. Peel. 2007. “The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth): Dark Sides of Virtue.” Melbourne University Law Review 31 (1): 106–145.

- Goldingay, R. L., B. D. Taylor, J. L. Parkyn, and J. M. Lindsay. 2018. “Are Wildlife Escape Ramps Needed Along Australian Highways?.” Ecological Management and Restoration 19 (3): 198–203.

- Grant, R., and E. Papadakis. 2004. “Transforming Environmental Governance in a “Laggard” State.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 21:144–160.

- Gurran, N., C. Gilbert, and P. Phibbs. 2015. “Sustainable Development Control? Zoning and Land use Regulations for Urban Form, Biodiversity Conservation and Green Design in Australia.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 58 (11): 1877–1902. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2014.967386.

- Hall, M., D. Nimmo, S. Watson, and A. F. Bennett. 2018. “Linear Habitats in Rural Landscapes have Complementary Roles in Bird Conservation.” Biodiversity and Conservation 27 (10): 2605–2623.

- Hamer, A. J., L. J. Harrison, and D. Stokeld. 2016. “Road Density and Wetland Context Alter Population Structure of a Freshwater Turtle.” Austral Ecology 41 (1): 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/aec.12298.

- Hardman, F. 2003. “Are our Land use Decisions Having Adequate Regard for the Environment?” Local Government Law Journal 9:34–48.

- Hawke, A. 2009. “The Australian Environment Act: Report of the Independent Review of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.” https://webarchive.nla.gov.au/awa/20130329091649/http://www.environment.gov.au/epbc/review/publications/final-report.html. Viewed 24th August. 2022.

- Hawkins, C. E., I. T. Ritrovato, and J. P. Swaddle. 2020. “Traffic Noise Alters Individual Social Connectivity, but not Space-Use, of RED-BACKED Fairywrens.” Emu-Austral Ornithology 120 (4): 313–321.

- Homel, B. 1999. “Just a Process Change? The Impact of IDAS on Environmental Protection in Queensland.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 161 (1): 75–91.

- Hu, R. 2015. “Sustainability and Competitiveness in Australian Cities.” Sustainability 7 (2): 1840–1860. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7021840.

- Iuell, B, ed. 2003. Wildlife and Traffic: A European Handbook for Identifying Conflicts and Designing Solutions. KNNV Uitgeverij. ISBN: 9050111866.

- Ives, C., M. P. Taylor, D. A. Nipperess, and P. Davies. 2010. “New Directions in Urban Biodiversity Conservation: The Role of Science and its Interaction with Local Environmental Policy.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 27:249–271.

- Jaireth, H., and M. Figg. 2014. “Dispute Resolution and the “EPBC Act Bilaterals”.” Local Government Law Journal 19:195–207.

- Johnson, C. D., D. Evans, and D. Jones. 2017. “Birds and Roads: Reduced Transit for Smaller Species Over Roads Within an Urban Environment.” Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 5:10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2017.00036.

- Johnson, C., D. Jones, T. Matthews, and M. Burke. 2022a. “Advancing Avian Road Ecology Research Through Systematic Review.” Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2022.103375.

- Johnson, C., T. Matthews, M. Burke, and D. Jones. 2022b. “Planning for Fauna Sensitive Road Design: A Review.” Frontiers in Environmental Science. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.959918.

- Jones, D., M. Bakker, O. Bichet, R. Coutts, and T. Wearing. 2011. “Restoring Habitat Connectivity Over the Road: Vegetation on a Fauna Land-Bridge in South-East Queensland.” Ecological Management & Restoration 12 (1): 76–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-8903.2011.00574.x.

- Jones, D., and J. Pickvance. 2013. “Forest Birds use Vegetated Fauna Overpass to Cross Multi-Lane Road.” Oecologia Australis 17 (1): 147–156. https://doi.org/10.4257/oeco.2013.1701.12.

- Kabir, Z., S. Momtaz, and R. Morgan. 2020. “Strategic Environmental Assessment of Urban Plans in Australia: The Case Study of Melbourne Urban Extension Plan.” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 38 (5): 368–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2020.1762389.

- Kennedy, M., N. Beynon, A. Graham, and J. Pittock. 2001. “Development and Implementation of Conservation law in Australia.” Review of European Community and International Environmental Law 10 (3): 296–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9388.00289.

- Kim, M. K., L. Evans, L. M. Scherl, and H. Marsh. 2016. “Applying Governance Principles to Systematic Conservation Decision-Making in Queensland.” Environmental Policy & Governance 26 (6): 452–467. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1731.

- Ledoux, L., S. Crooks, A. Jordan, and R. K. Turner. 2000. “Implementing EU Biodiversity Policy: UK Experiences.” Land Use Policy 17 (4): 257–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-8377(00)00031-4.

- Lindsay, B., and J. Trezise. 2016. “The Drafting and Content of Threatened Species Recovery Plans: Contributing to Their Effectiveness.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 33:237–251.

- Macintosh, A. 2004. “Why the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act’s Referral, Assessment and Approval Process is Failing to Achieve its Environmental Objectives.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 21:288–311.

- Macintosh, A., P. Gibbons, J. Jones, A. Constable, and D. Wilkinson. 2018. “Delays, Stoppages, and Appeals: An Empirical Evaluation of the Adverse Impacts of Environmental Citizen Suits in the New South Wales Land and Environment Court.” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 69:94–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2018.01.001.

- Marsden, S. 2013. “Strategic Environmental Assessment in Australian Land-use Planning.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 30:422–433.

- Marsden, S., and J. Ashe. 2006. “Strategic Environmental Assessment Legislation in Australian States and Territories.” Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 13 (4): 205–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/14486563.2006.10648688.

- Marshall, A. J., M. J. Grose, and N. S. G. Williams. 2019. “From Little Things: More Than a Third of Public Green Space is Road Verge.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 44: 126423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126423.

- McGrath, C. 2004. “Key Concepts of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth).” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 22 (1): 20–39.

- McGrath, C. 2014. “One Stop Shop for Environmental Approvals a Messy Backward Step for Australia.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 31 (3): 164–191.

- Meurling, R. 2005. “IDAS – More, or Less, Integrated?” Local Government Law Journal 11:74–87.

- Moher, D., A. Liberati, J. Tetzlaff, D. G. Altman, and P. Group. 2009. “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement.” PLoS Medicine 6 (7): e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Moon, B. 1998. “Environmental Impact Assessment in Queensland, Australia: A Governmental Massacre!.” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 16 (1): 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.1998.10590185.

- Morris, R. K. A. 2011. “The Application of the Habitats Directive in the UK: Compliance or Gold Plating?.” Land Use Policy 28 (1): 361–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2010.04.005.

- Munro, J., I. Williamson, and S. Fuller. 2018. “Traffic Noise Impacts on Urban Forest Soundscapes in South-Eastern Australia.” Austral Ecology 43 (2): 180–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/aec.12555.

- Ortega-Argueta, A., G. Baxter, and M. Hockings. 2011. “Compliance of Australian Threatened Species Recovery Plans with Legislative Requirements.” Journal of Environmental Management 92 (8): 2054–2060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.03.032.

- Papp, C.-R., I. Dostál, V. Hlaváč, G. M. Berchi, and D. Romportl. 2022. “Rapid Linear Transport Infrastructure Development in the Carpathians: A Major Threat to the Integrity of Ecological Connectivity for Large Carnivores.” Nature Conservation 47: 35–63. https://doi.org/10.3897/natureconservation.47.71807.

- Pickering, C., and J. Byrne. 2014. “The Benefits of Publishing Systematic Quantitative Literature Reviews for PhD Candidates and Other Early-Career Researchers.” Higher Education Research & Development 33 (3): 534–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.841651.

- Rieder, J. M. 2011. “An Evaluation of two Environmental Acts: The National Environmental Policy Act and the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act.” Asia Pacific Journal of Environmental Law 14 (1-2): 105–137.

- Samuel, G. 2020. “The Independent Review of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.” https://epbcactreview.environment.gov.au/. Viewed 24th August. 2022.

- Simmonds, J. S., A. E. Reside, Z. Stone, J. C. Walsh, M. S. Ward, and M. Maron. 2019. “Vulnerable Species and Ecosystems are Falling Through the Cracks of Environmental Impact Assessments.” Conservation Letters 13 (3). https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12694.

- Sollberger, K. 2006. “Local Government Autonomy in Australia/New South Wales and Switzerland/Graubünden, with a Particular Regard to the Environment.” Local Government Law Journal 12:82–97.

- Stein, P. L. 2000. “Are Decision-Makers Too Cautious with the Precautionary Principle?” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 17 (1): 3–23.

- Summerville, J. A., B. A. Adkins, and G. Kendall. 2008. “Community Participation, Rights, and Responsibilities: The Governmentality of Sustainable Development Policy in Australia.” Environment & Planning C: Government & Policy 26 (4): 696–711. https://doi.org/10.1068/c67m.

- TMR. 2000. Fauna Sensitive Road Design: Volume 1 - Summary. Brisbane: Queensland Department of Main Roads, Planning, Design and Environment Division.

- TMR. 2010. Fauna Sensitive Road Design Volume 2 - Chapter 1: Overview. Brisbane: Queensland Department of Main Roads.

- Tridgell, S. 2013. “Evaluating the Effectiveness of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth): 2008-2012.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 30 (3): 245–258.

- van der Ree, R., D. Smith, and C. Grilo. 2015. “The Ecological Effects of Linear Infrastructure and Traffic: Challenges and Opportunities of Rapid Global Growth.” In Handbook of Road Ecology, edited by R. van der Ree, D. Smith, and C. Grilo, 2nd ed., 1–9. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Veith, G., L. Louis, P. Aumann, S. Chia, and N. Callaghan. 2015. Guide to Road Design Part 6B: Roadside Environment. Austroads Ltd. https://austroads.com.au/publications/road-design/agrd06b. Viewed 15th April. 2022.

- VicRoads. 2012. Fauna Sensitive Road Design Guidelines. (1447218). Melbourne: VicRoads Environmental Sustainability. Victoria Government.

- Williams, P. J., and A. M. Williams. 2016. “Sustainability and Planning law in Australia: Achievements and Challenges.” International Journal of Law in the Built Environment 8 (3): 226–242. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLBE-06-2016-0008.

- Wilson, R. F., H. Marsh, and J. Winter. 2007. “Importance of Canopy Connectivity for Home Range and Movements of the Rainforest Arboreal Ringtail Possum (Hemibelideus Lemuroides).” Wildlife Research 34 (3): 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR06114.

- WorldData. 2024. “Transport and Infrastructure in Australia.” WorldData.info. https://www.worlddata.info/oceania/australia/transport.php#:~:text=The%20network%20of%20roads%20and,place%20in%20the%20global%20ranking. Viewed 15th May. 2024.

- Wright, I. 2001. “Plan Making and Development Assessment Under Queensland's Integrated Planning Act - Implications for the Public and Private Sectors.” Local Government Law Journal 7:78–91.

- Young, T., and G. Gray. 2000. “The Validity of Queensland Environmental Conditions.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 17 (6): 536–544.