ABSTRACT

In areas where science is quite incomplete, such as in the deployment and use of new environmental water reserves, it might be reasonable to expect that managers will be learning ‘on the job’ or ‘learning by doing’ as they seek to apply best available science to decision making. Similarly, it might be expected that the public would have some empathy for the challenges facing environmental managers with incomplete data on which to base decisions. However, there is also a contrasting body of literature that shows the preferences of the public and voters for certainty in outcomes. This article reviews the status of adaptive management in the context of using water to bolster environmental outcomes. We also report the results of a discrete choice experiment where respondents were asked to assign a value to adaptive management undertaken by water managers. The article reports the difficulties of developing an attribute along these lines and the challenges of encouraging the public to engage with the concept and place a value on it. This provides a platform for considering what this means more generally for environmental interventions and the acceptance of environmental policies where ecological outcomes are frequently uncertain.

1. Introduction

The notion of adaptive management has been a mainstay of environmental stewardship for several decades. The initial contributions by Holling (Citation1978) and Walter and Hilborn (Citation1978) laid the foundation for numerous subsequent analyses that have sought to categorise adaptive management processes into frameworks or typologies (e.g. McFadden, Hiller, and Tyre Citation2011), provide examples of deployment (e.g. Moore and Conroy Citation2006), reflect on how it might be done better (e.g. McCarthy and Possingham Citation2007) and ponder the intersect between adaptive management and other environmental management philosophies (e.g. Stringer et al. Citation2006). Adaptive management in its most basic form implies that information about the impacts of earlier management interventions is used to inform subsequent choices (Lessard Citation1998). The common phrase of ‘learning by doing’ is used in some contexts and has an intuitive appeal, especially when many natural systems under management are complex and not fully understood. Nonetheless, the concept has important nuances.

Adaptive management has gained traction beyond academic circles and is now enshrined in legislation in multiple countries. The principles of adaptive management also cover multiple domains including fisheries (see Baumgartner et al. Citation2014; Conallin, Campbell, and Baumgartner Citation2018) and water resource planning (see, for example, the New South Wales Water Management Act Citation2000). Regardless of its widespread acceptance amongst the environmental management community, several concerns have emerged about the clarity of adaptive management and how it is pursued in practice (see, for instance, Allen and Gunderson Citation2011; Walters Citation2007; Williams and Brown Citation2014).

First, there are relatively few successful cases of adaptive management actually reported in the literature (Allen and Gunderson Citation2011). This might not be a major concern, especially given the circular processes involved and the subsequent difficulty of adjudging its success against any other management approach. For instance, questions have arisen about the start and end point at which approaches to adaptive management are deployed and what their performance is measured against (Gregory, Failing, and Higgins Citation2006). Second, a number of studies raise concerns about the capacity of decision makers to comprehend the breadth of adaptive management and to map the advantages of different forms against cost (Gregory, Failing, and Higgins Citation2006). Adaptive management in some cases appears randomly confused with a suite of alternatives, like monitoring or evaluation programmes, with evidence drawn from water planning proving particularly instructive in this context (e.g. Hasselman Citation2017a).Footnote1 Third, it is not clear that adaptive management resonates as a concept with anyone else other than environmental management specialists (Walters Citation2007). This is particularly concerning given that many environmental problems require input from multiple disciplines and agencies, necessitating buy-in from a wide range of stakeholders. Moreover, management actions usually come at a cost, and it might be reasonable to expect that those bearing this expense would at least have a passing interest in costs and any related benefits.

A related concern is the interface between public perceptions of uncertainty generally and how this relates to their ongoing support for an action. On the one hand, there is a body of literature that associates uncertainty with less political support, especially amongst less discerning voters (e.g. McGraw, Hasecke, and Conger Citation2003) and those who are risk averse (Tomz and van Houweling Citation2009). This is important because, in the water space, most decisions that require a reallocation of resources to engender a positive environmental outcome are instigated at the political level, and yet the environmental outcome cannot always be assured nor can successful implementation of the proposed intervention. Advocates for an environmental change might therefore face an uphill battle with opponents pointing to the uncertainty of any future improvement as a basis for retaining the status quo. There is also evidence in the literature that uncertainty can act against efforts to win support when individuals already hold a predisposition against change (Haas, Baker, and Gonzalez Citation2021). Those not in favour of environmental restoration will likely solidify their rejection of environmental measures where a level of uncertainty exists. It is therefore important to have a better understanding of how the general population understand and value notions like adaptive management and evidence-based decision making. More specifically, we test the hypothesis that if the benefits and value of adaptive management can be conveyed to the general public, they will be more inclined to support an intervention to bring improved environmental outcomes, especially if they already hold pro-environmental values.

An opportunity arose to explore the public understanding and potential willingness to pay for adaptive management when a study was undertaken that focussed on the value Melburnians placed on environmental water entitlements managed by the bulk water provider. This study employed a discrete choice experiment that included an attribute focussed on adaptive management along with additional costs to households and varying quantities of environmental water that produced different ecological outcomes in catchments. The study also collected data on environmental attitudes of respondents. We are thus able to empirically explore questions like: ‘Are households willing to pay for adaptive management in the context of environmental water?’ and ‘Do those with stronger environmental preferences systematically value adaptive management more than others?’ By answering these questions, this research adds to the debate about adaptive management and provides a basis to reflect on the implications for environmental policy makers.

The article itself comprises four additional parts. In Section 2, we review the basics of adaptive management and evaluate some emerging complications specific to water resources. Section 3 describes the discrete choice experiment method used, and Section 4 reports the results of a choice experiment focussed on environmental water entitlements in Victoria, Australia. Section 5 offers a discussion of the key results along with a reflection of the implications for adaptive management in practice.

2. Adaptive management and water resources

The rationale for investing in adaptive management stems from the uncertainties that pertain to the management of natural ecosystems, especially as these systems are seldom stable and unlikely to move to an everlasting equilibrium (Holling Citation1978; Pagan and Crase Citation2005). Hasselman (Citation2017, 10) distinguished different forms of uncertainty, and each has implications for the form of adaptive management to deploy. So-called imperfect knowledge is described by Hasselman (Citation2017, 10) as ‘undiscovered science’ and requires experimentation to facilitate the progressive reduction in uncertainty; active adaptive management is used to reduce knowledge gaps. In contrast, incomplete knowledge is limited to cases where at least some knowledge is available, but is not held by an individual decision maker; rather it is spread across multiple parties and processes are required to bring the incomplete components to the fore. Arguably, this could be facilitated by adaptive management or some other process. Finally, unpredictability relates to those forms of uncertainty that attend ‘unforeseen futures with unknown societal and environmental responses’ (Hasselman Citation2017, 10). In this instance, passive adaptive management would likely suffice in so much as it intuitively treats unpredictability as a given. Here the manager seeks to identify the single-best solution for dealing only with the problem at hand and accepts that new solutions will necessarily need to be found for other unpredictable futures. The main difficulty here is that the manager has no idea what the outcome would have been if the action was not undertaken or done differently. Consequently, all learning only occurs in response to the outcome from a single decision applied at a point in time, whereas the baseline might vary from year to year.

Many advocates for adaptive management bemoan the fact that practitioners routinely claim to be employing adaptive management when in fact they are defaulting to more passive forms at best (Walters Citation2007). There is also concern that monitoring of the environment is treated as being analogous to adaptive management: ‘[S]ome people seem to think that monitoring resource conditions is sufficient in and of itself to make a project “adaptive”' (Williams and Brown Citation2014, 14). This is only likely to ever be true if monitoring outcomes are used to improve future decision making in response to the intervention of interest. Arguably, everyone seems to agree with the concept of adaptive management even if they have different notions in mind when expressing support.

Part of this confusion stems from the fact that adaptive management should, in principle, comprise both technical and institutional learning. Technical learning relates to increasing our understanding of resource structure and functioning, while institutional learning encompasses learning about resource problems and how better decisions can be made about dealing with those problems (Williams and Brown Citation2014). Put differently, technical learning may be of use in some situations, but to actually harness the value of the additional knowledge requires an investment in social structures to develop and process the new information within resource management organisations. Adaptive management is an iterative process that can take many years, and not all paths taken will lead to success. Successes are to be celebrated, but equally important is reporting on failures and understanding the reasons why an intervention failed. Otherwise, it is doomed to be repeated.

Williams and Brown (Citation2014, Citation2016) correlate the two types of learning with two discrete phases of adaptive management. The first is referred to as the ‘deliberative’ phase and entails engaging with a range of stakeholders to understand the appropriate way to frame the resource management problem, setting the objectives of any intervention or strategy, developing a range of alternatives to consider, undertaking some predictions around the impacts of different alternatives and developing monitoring protocols by which to adjudge impacts (Williams Citation2011). These tasks are essentially aligned with the process of institutional learning. The second phase is referred to as the ‘iterative’ phase and aligns with technical learning. Here, a decision is made about which action to take, monitoring occurs, and an assessment is then made about management effectiveness. The technical learning is accomplished by comparing the predictions from the deliberative phase with the actual environmental impacts, whereas institutional learning is facilitated by ‘periodically interrupting the cycle of technical learning in the iterative phase to reconsider project objectives, management alternatives and other elements of the set-up phase’ (Williams and Brown Citation2014, 6).

During the deliberative phase (i.e. ostensibly the set up and strategic review phase), engagement with a variety of groups and sets of knowledge are seen as paramount (Wondolleck and Yaffe Citation2000). Arguably, this has led to other concepts emerging in the literature such as adaptive co-management and adaptive governance. Hasselman’s (Citation2016) concise review of these concepts highlights the complexity and overlap between them. After reviewing the epistemological foundations of adaptive management in general, they conclude that adaptive co-management is best defined as ‘a type of adaptive management that empowers resource users and managers in experimentation, monitoring, deliberations and responsive management of local scale resources, supported by, and working with, various organisations at different levels’ (37). Hasselman (Citation2016, 39) notes particular concerns about the current confusion surrounding the use of the term adaptive governance, arguing in the current milieu there is a ‘lack of additionality’. In an effort to provide more surety around its meaning, they describe the notion therefore:

Adaptive governance systematically integrates adaptive management across the political processes, polity and policy aspects of governance, with the implications to legitimacy and accountability addressed by the structures of the agents present. (Hasselman Citation2016, 40)

In summary, adaptive management is intuitively appealing to most people working in natural resource management contexts, because ecosystems are notoriously complex and uncertain. The approach implies some systematic processes being put in place to ultimately reduce at least some form of uncertainty and to improve future interventions. This necessarily requires some effort to: (a) establish a system for integrating new information back into decisions (i.e. institutional learning) and (b) generate and/or harvest information about resource functioning. The evidence on the success of adaptive management is varied, but this may also be a function of the different forms it can legitimately take. For example, passive adaptive management is likely to be adequate in settings where the aim is to access existing information held in other quarters or where events are perceived as strictly non-ergodic. To adjudge adaptive management to have failed due to a lack of experimentation in those cases would miss the point. The common view is that adaptive management will function more effectively if it facilitates engagement with a range of stakeholders, and this is given particular emphasis through the notion of adaptive co-management. Adaptive governance implies a higher order of flexibility covering elements of polity, politics and policy.

Water management has both employed adaptive management (e.g. Murray-Darling Basin Authority Citation2023a) and been influenced by other philosophies that share some elements in common with the tenets of adaptive management (e.g. Downs and Gregory Citation1991). Adaptive management adheres to the view that participation in the process by a range of stakeholders is required; this is seen as a critical ingredient to success. Participation can be used to harness existing knowledge and bring it to the fore, i.e. help counter what Hasselman (Citation2016) describes as incomplete knowledge, and participation is also seen as critical in setting the goals as emphasised by Williams and Brown’s (Citation2014) deliberative phase. Participation is also necessarily pluralistic in nature and therefore notionally consistent with the adaptive co-management ethos.

At its crudest level, participants comprise a minimum of two groups: government officials responsible for implementation of environmental management and members of the public who may hold an interest in the outcomes of decisions, especially as many will be involved in funding the activities through tax payments or other charges. Amongst the more costly attempts to undertake environmental restoration in a riverine setting is the much-publicised Murray-Darling Basin Plan (see, for example, Crase Citation2012) that came with an initial budget of $13 billion. The Plan aims to reduce the amount of water taken for consumptive use and provide additional water for environmental purposes. A critical objective of the Plan was to establish an environmental water reserve, i.e. water entitlements held and managed with the purpose of delivering environmental beneficial outcomes. The overarching hypothesis is that restoring more water for environmental uses will enhance the riverine environment, which has been deemed to suffer disproportionately from earlier water management approaches in the basin. In recognising there is a degree of uncertainty to the ecological and social responses of reassigning water, the MDBA itself notes that a ‘cornerstone of the strategy for managing water resources in the Basin is adaptive management – “learning as you go” by trialling techniques, monitoring, and making changes as needed' (MDBA Citation2023b).

Hasselman (Citation2017) reviewed the implementation of the Murray-Darling Basin Plan with a focus on environmental water management. Two forms of analysis were used to understand what adaptive management meant from the perspective of the various state and federal agencies involved in the Basin Plan. The first was a detailed document analysis covering legislation, planning documents, publicly accessible reports, policy statements, speeches and the Plan itself. For the second phase, interviews were held with sixteen Commonwealth policy makers and implementers along with ten interviews of state-based water bureaucrats and four stakeholders with regional responsibilities. The interviews ‘sought to determine how adaptive management is socially constructed, under the framework set by the Basin Plan and associated governance arrangements’ (Hasselman Citation2017, 11).

In the context of the documentation analysis, Hasselman (Citation2017) concluded that adaptive management was employed in the passive sense only and that there were also strong managerial overtones in its use. They contended that ‘a relationship between science and adaptive management is not apparent, instead, monitoring and evaluation of the Basin Plan is seen to both contribute to adaptive management and to improve knowledge’ (Hasselman Citation2017, 13). Similar findings emerged from their analysis of interviews with policy and implementation personnel and they noted, somewhat dishearteningly, the proclivity of respondents to have quite different meanings of the concept, albeit usually inclined to the more passive forms. Hasselman therefore concluded from the interviews:

Adaptive management, despite its definition and prescription in the legislation, remains an enigma. There is overriding use of monitoring and evaluation language, a dominance of passive forms of adaptive management, as connected to evaluation, and a loss of experimentation to gain scientific knowledge. (Hasselman Citation2017, 13)

3. Development of a discrete choice experiment to understand households’ valuation of adaptive management

Melbourne is one of Australia’s fastest-growing cities, albeit located outside the Murray-Darlin Basin, and meeting water demand can be both costly and contentious. New sources of supply include rain-fed storages, but these necessarily restrict the environmental outcomes that can be achieved downstream of the storage. Desalination is an option, but has been shown to come with costs and some protestation (e.g. Poposki Citation2018). There is also scope for localised water management in the landscape to offset some current uses of potable water, but this can prove costly and the yield can be limited. A pipeline attached to the Murray-Darlin Basin is also available that connects Melbourne to irrigation areas north of the city, although this has proven politically difficult to operationalise (see, Crase, Pawsey, and Cooper Citation2014). Against that background, the bulk water supplier was keen to understand how customers valued environmental water entitlements, especially given its additional role as the environmental steward of waterways that circumscribe the city.

As noted, Melbourne is not located in the Murray-Darling Basin and the attitudes expressed by customers may not be strictly additive to the challenges identified by Hassleman (Citation2017) in their analysis of the Murray-Darling Basin Plan. Nonetheless, the bulk water supplier does control non-trivial environmental water entitlements on the Yarra, Tarago and Werribee river systems around Melbourne and seeks to manage these in a manner that facilitates learning by doing. In addition, our interest in this case focussed on how laypeople might conceptualise adaptive management and how the concept could be presented so that they could express a value for it. To the knowledge of the authors, this has not been previously attempted.

A choice experiment was designed where adaptive management was chosen as an attribute. Choice experiments are one form of discrete choice experiments and are an established means of generating monetary values for non-marketed goods, especially environmental goods. The basic idea of a choice experiment is that respondents are given choice sets that comprise a small number of options (usually two or three). Each option has the same attributes but the levels of the attributes vary across each option. The respondent can only select one option within each choice set and, having made a choice, moves to another choice set. By systematically varying the levels within the choice sets, respondents can ultimately reveal how they make trade-offs across the attributes and levels. If one of the attributes has a monetary value (e.g. price or an extra amount paid on a bill), the relative dollar-value of other attributes can be established empirically, referred to as the marginal rate of substitution and expressed as part-worth estimates. Choice experiments are well-grounded in theoretical contributions like random utility theory (McFadden Citation1986) and have been used in multiple contexts including coastal management (Rolfe et al. Citation2021; Tocock et al. Citation2023), land development (Graham et al. Citation2020) and water management (Bennett, McNair, and Cheesman Citation2016; Cooper and Crase Citation2008; Sinner et al. Citation2016).

Choice experiments are usually developed in an iterative fashion. Attributes are identified by the research problem at hand and refined with expert input, usually gained through semi-structured interviews (see Hensher, Rose, and Green Citation2015). Since ultimately the attributes are valued by laypeople, focus groups are then required to convert the expert information into a form that is tractable with the general population.

A detailed description of focus sessions and the results of the environmental water valuation are reported in Cooper, Crase, and Burton (Citation2023). Here we focus specifically on the challenges related to valuing adaptive management. A total of eight focus sessions were held between September 2016 and January 2017 with recruitment undertaken through a proprietary panel of Melbourne residents and participants comprising individuals over 18 years with responsibility for paying household water bills. The focus groups were also used to test participants’ understanding and preferred description of adaptive management. The concept was introduced along the lines of managers not fully understanding the ecology of the river system, and the fact that allocating water for the environment was a relatively new approach. Many participants thought that the idea of learning by doing and monitoring outcomes was fitting, with one respondent describing it as ‘common sense’ and others noting it is ‘appropriate in the circumstances’. It was also a common view that environmental managers should do this already. A discussion around this topic was stimulated when a respondent noted: ‘Isn’t that what we already pay for?’

More active forms of adaptive management were subsequently tested. Participants were introduced to the idea of testing competing hypotheses by using water differently and then actively gathering information about the consequences and feeding this back to the next watering event. In an effort to make this resonate with participants, it was noted that conventional trial and error would take a decade to assemble all the necessary information to do a reasonable job of deploying environmental water. In contrast, active adaptive management would double the rate of learning (i.e. managers would know in five years what would usually take ten years to learn).

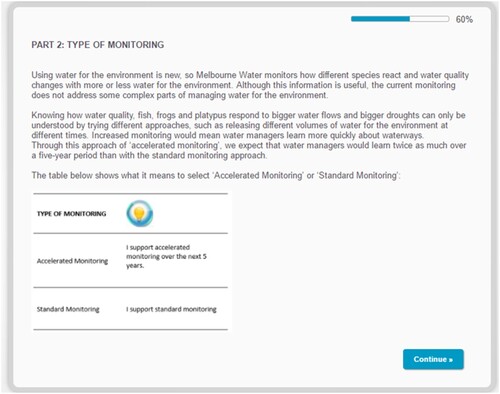

While respondents were comfortable with the description of the activities related to watering events, there was general resentment to the notion of taking this too far. Some groups raised concerns about ‘experimenting with the environment’. Several respondents expressed disquiet about ‘killing fish to learn more’. Respondents were generally at ease with terms like ‘monitoring’ and ‘learning’, and in that context a draft survey was developed with an attribute described as ‘Monitoring and Learning’. The attribute had two levels titled ‘Accelerated’ and ‘Standard’, which loosely aligned with active and passive forms of management, respectively.

After testing the pilot survey in some focus groups, there remained some concern from respondents about paying extra for managers to learn. This was explored with the project steering group, which comprised environmental experts from the bulk water utility. The steering group recommended excising the term ‘learning’ from the attribute title. Accordingly, the choice experiment proceeded with an attribute titled ‘Type of Monitoring’ with two levels: ‘Accelerated Monitoring’ which would double the knowledge generated versus ‘Standard Monitoring’.

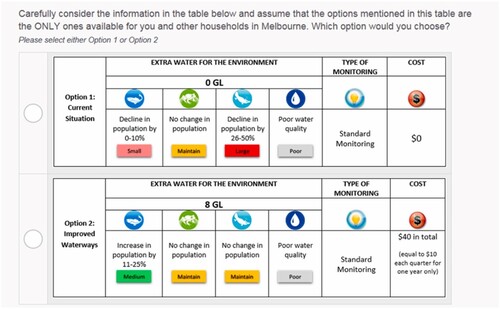

Collectively, this resulted in a choice experiment with three attributes: one described as ‘Extra Water for the Environment’ which then used colour coding and percentages to translate the additional water into positive changes in species population and water quality. The status quo in this experiment would see a decline in fish, frog and platypus populations, along with ongoing poor water quality. ‘Cost’ describing the additional payments on water bills to realise change and ‘Monitoring’ relating to two forms of adaptive management, one which would result in double the rate of learning compared to standard monitoring. A sample choice set is provided in and the specific explanation for the adaptive management attribute shown to respondents appears in .

Figure 1. Sample choice set for 8GL of additional environmental water (source: Cooper, Crase, and Burton Citation2023).

A range of innovations have been incorporated into the administration of choice experiments and are now relatively common practice. These include employing so-called ‘cheap talk’ statements to remind participants to engage with the choices seriously, test questions to monitor the extent to which participants understand the contextual information and attitudinal scales to facilitate more detailed modelling of preferences and heterogeneity. In addition to these administrative innovations, the statistical modelling of the data gathered from choice experiments continues to be refined. Multinomial logit models are arguably the more rudimentary means of analysing choice data and can be used to establish the significance of attributes and their related coefficients. However, mixed logit modelling has become more common, especially because of the capacity to offer improved behavioural specifications. Mixed logit models also allow for the relaxation of the independence of irrelevant alternatives assumption and remove the assumption that the coefficients are the same for all individuals. In addition, latent class modelling can be used to better understand heterogeneity within choice data by identifying classes of individuals with differing preferences.

4. Results of the discrete choice experiment

Data from the choice experiment were collected online between 23 February and 8 April 2017, with a total sample of 701 respondents stratified by water retailers across the city. In addition to the choice sets and related video and text information, the survey included questions about attitudes, using items adapted from the New Ecological Paradigm. Socio-economic information and standard items that limit survey bias were also included (e.g. cheap talk and test questions). The survey also included questions that automatically appeared if respondents only chose the status quo in all their choice sets or always opted for the alternative. The purpose of these questions was to establish if the respondent was protesting, rather than making trade-offs as intended by the experiment. Removing protestors (e.g. respondents who both consistently selected an option and then revealed in the follow-up that they made choices because they do not trust government to deliver or respondents who chose an option because they thought they would not have to pay) reduced the sample to 559.

The choice data were modelled using both rudimentary and more sophisticated statistical techniques. Cooper, Crase, and Burton (Citation2023) report the findings relevant to the value of environmental water, while here we focus primarily on the findings that relate to the adaptive management attribute.

Initially, models were generated using a mixed logit form that permitted the ‘Additional Water’ attribute’s alternative-specific constant and the ‘Additional Water’ coefficient to be treated as normally distributed random parameters. Additional interactions were included with two factors generated from attitudinal data, both relating to environmental attitudes. The first factor (fac1) was a measure of an individual’s ‘pro-environment’ perspective. The second (fac2) captured the view that respondents saw natural resource management as not being imperative, although the environment does contribute to human welfare. Interactions between the factors and the attributes of the choice experiment, including monitoring, did not generate any statistically significant effects.

The additional interactions were also tested using the data on the number of incorrect answers to the test questions (of which there were three) that were included to measure comprehension and attentiveness throughout the survey. In addition, the number of incorrect answers to test questions was shown to influence the ‘Cost’ and ‘Extra Water’ attribute, suggesting some systematic link between choosing incorrect answers and stated preferences. Accordingly, these were included in the statistical modelling and appear as ‘wrong’ in . The alternative specific constant relates to how respondents view the status quo versus a shift away from the status quo generally. A statistically significant and negative coefficient for the alternative specific constant implies that respondents would gain utility from change, regardless of the level of the attributes in the alternative. The alternative specific constant and interactions with the alternative specific constant are thus included in the modelling in . A variable that indicated whether respondents thought the study would make a difference to water management was found to be statistically significant when interacted with the alternative specific constant. The implication is that those who more strongly believe their answers to the survey will affect water management place greater weight on retaining the status quo.

Table 1. Mixed logit estimates of discrete choice experiment data.Footnote2

Importantly, no significant effects were identified for the ‘Monitoring’ attribute, regardless of main or interaction effects. This supports the view that the form of adaptive management (i.e. passive or active), at least as described in this survey, had no bearing on how respondents chose between supporting extra environmental water or not.

An additional model was generated using only those respondents who answered all test questions correctly, but parameter estimates did not differ significantly from those generated in the model reported in , implying a degree of robustness.

Latent class modelling was also undertaken and is reported in appendices of Cooper, Crase, and Burton (Citation2023). Four classes of respondent were identified covering those who trade off water against cost, along with preferring change in general; a class who prefer change but do not respond systematically to the attributes; a class that values change overall but is highly cost sensitive; and a class that is solely focussed on cost and have a 50 per cent probability of choosing either option. Markedly, no class showed any systematic preference – in either direction – for the attribute that proxied adaptive management.

Additional insights can be gained by examining the questions used to identify protest respondents. As noted, these are respondents who potentially opt for (or against) the status quo consistently because of the structure of the experiment. This sequence of questions was presented only to respondents who continuously opted for the status quo, regardless of the choices on offer. Ignoring those who made mistakes to the test questions revealed a total of 93 respondents who always chose the status quo. To establish the extent to which this behaviour was a protest, 15 explanatory statements were then provided (e.g. ‘I don’t trust government to deliver’). One option was the statement ‘I’m scared that accelerated monitoring will lead to mistakes and harm’. Only one respondent indicated this as a reason for always opting for the status quo.

As is common with most contemporary application of choice experiments, a series of follow-up questions were used to establish the ease with which the survey was completed and to allow self-reporting of understanding and comprehension. This was done in the form of Likert scale questions ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ through to ‘strongly agree’. Tellingly, 91 per cent of respondents indicated either ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ to the statement ‘I read all of the information provided in this part of the survey carefully’. In addition, 89 per cent of respondents chose either ‘strongly agree’ or ‘agree’ for the statement ‘I understood all of the information provided in this part of the survey’. Finally, 92 per cent either ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ that ‘I was given enough information in this part of the survey to make an informed choice’.

Collectively, these results suggest that the description and explanation of the adaptive management attribute were both plausible and generally understood by respondents, but the willingness to pay for active adaptive management in preference to passive forms was insignificant, irrespective of the modelling approach.

Part of the motivation for this paper was to explore the hypothesis that those with stronger preference for environmental remediation would be more inclined to tolerate or even support environmental uncertainty. In contrast, we also hypothesise that those with weaker commitment to the environment will treat environmental uncertainty as an additional reason to not offer support for environmental remediation. The fact that neither of the attitudinal factors produced any significant effects when interacted with ‘monitoring’ leads us to reject both hypotheses.

5. Lessons for adaptive management in practice

There are several important lessons to be taken collectively from the results of the choice experiment in Melbourne, the extant literature reviewed of adaptive management and the links between uncertainty and political support.

First, the broad notion of learning by doing is generally accepted as a reasonable response when the uncertainty of natural systems needs to be considered. This acceptance extends to both experts and laypeople. Moreover, there is some evidence that the latter recognises this as a norm for experts in some fields, but not an attribute worthy of funding per se.

Second, the value of the distinction between active and passive adaptive management is not at all clear to many parties. Both experts involved in managing environmental outcomes in the Murray-Darling Basin and laypeople in Melbourne regularly conflate notions like monitoring and evaluation with adaptive management. Moreover, when there was an option of including the term ‘learning’ as a descriptor of the attribute presented to laypeople in Melbourne, the steering committee of experts opted to reduce this to ‘monitoring’. This is not to be taken as criticism of the committee. Rather it points to the challenge of making clear the benefits of active adaptive management and then articulating them with precision.

In some respects, acceptance of the term ‘monitoring’ as a way of making adaptive management accessible to laypeople is tolerable, provided a distinction is subsequently made between the different actions required for active versus passive management. What is probably less tolerable is the confusion evident amongst the expert community about what adaptive management entails in its different manifestations.

We contend that the information provided in establishing the context of the choice experiment in Melbourne made some progress in explaining the distinction to the general public. Further research where environmental outcomes are directly proportional to the investment in adaptive management, is probably worth pursuing. This would imply that respondents would not be presented with certain environmental outcomes, but with some probability of achieving outcomes, and the adaptive management would then imply greater certainty about achieving those outcomes. Clearly, this needs to be balanced with increasing the cognitive demands of an already complex technique and acceptance on the part of funding agencies to publicly communicate uncertainty around decision making. This latter issue may be the greatest challenge, because environmental agencies are also potentially cognisant of the prospect of uncertainty being used by opponents to stall environmental actions.

It is nonetheless clear that adaptive management can be appreciated, and understood, by multiple stakeholders including laypeople. It is therefore important for practitioners involved in environmental management to improve the clarity with which they conceptualise and employ adaptive management strategies. As with other broadly accepted environmental doctrines, adaptive management seems likely to deliver greatest net benefits when thoughtfully deployed. Ideally, it will not become a ‘tick-box’ for managers seeking agreement from policy makers, and governments will simultaneously invest in communicating the necessity of this approach in the face of uncertainty. This is likely to be increasingly important as the challenges of water management increase in the face of climate change.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Monitoring and evaluation is not adaptive management in its own right but, if well-designed and resourced, does have an important role to play in the process.

2 These results correspond to model M1 in Table 7 of Cooper, Crase, and Burton (Citation2023).

References

- Allen, C., and H. Gunderson. 2011. “Pathology and Failure in the Design and Implementation of Adaptive Management.” Journal of Environmental Management 92 (5): 1379–1384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.10.063.

- Baumgartner, L., J. Conallin, I. Wooden, B. Campbell, W. Robinson, and M. Mallen-Cooper. 2014. “Using Flow Guilds of Freshwater Fish in an Adaptive Management Framework to Simplify Environmental Flow Delivery for Semi-Arid Riverine Systems.” Fish and Fisheries 15 (3): 410–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12023.

- Bennett, J., B. McNair, and J. Cheesman. 2016. “Community Preferences for Recycled Water in Sydney.” Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 23 (1): 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/14486563.2015.1129364.

- Conallin, J., J. Campbell, and L. Baumgartner. 2018. “Using Strategic Adaptive Management to Facilitate Implementation of Environmental Flow Programs in Complex Social-Ecological Systems.” Environmental Management 62 (5): 955–967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-018-1091-9.

- Cooper, B., and L. Crase. 2008. “Waste Water Preferences in Rural Towns Across North-East Victoria: A Choice Modelling Approach.” Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 15 (1): 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/14486563.2008.9725181.

- Cooper, B., L. Crase, and M. Burton. 2023. “‘Households’ Willingness to pay for Water for the Environment in an Urban Setting.” Journal of Environmental Management 348: 119263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119263.

- Crase, L. 2012. “The Murray-Darling Basin Plan: An Adaptive Response to Ongoing Challenges.” Economic Papers 31 (3): 318–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-3441.2012.00187.x.

- Crase, L., N. Pawsey, and B. Cooper. 2014. “The Closure of Melbourne's North-South Pipeline: A Case of Hydraulic Autarky.” Economic Papers 33 (2): 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-3441.12076.

- Downs, P., and K. Gregory. 1991. “How Integrated is River Basin Management?” Environmental Management 15 (3): 299–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02393876.

- Graham, V., C. M. Fleming, F. Agimass, and J. C. R. Smart. 2020. “Preferences for the Future of the Southport Spit: Evidence from a Choice Experiment.” Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 27 (4): 396–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/14486563.2020.1843193.

- Gregory, R., L. Failing, and P. Higgins. 2006. “Adaptive Management and Environmental Decision Making: A Case Study Application to Water use Planning.” Ecological Economics 58 (2): 434–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.07.020.

- Haas, I., M. Baker, and F. Gonzalez. 2021. “Political Uncertainty Moderates Neural Evaluation of Incongruent Policy Positions.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 376 (1822). https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0138.

- Hasselman, L. 2016. “Adaptive Management; Adaptive co-Management; Adaptive Governance: What’s the Difference?” Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 24 (1): 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/14486563.2016.1251857.

- Hasselman, L. 2017. “Adaptive Management Intentions with a Reality of Evaluation: Getting Science Back Into Policy.” Environmental Science and Policy 78: 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.08.018.

- Hensher, D., J. Rose, and W. Green. 2015. Applied Choice Analysis. Cambridge.: Cambridge University Press.

- Holling, C. 1978. Adaptive Environmental Assessment and Management. London: John Wiley and Sons.

- Lessard, G. 1998. “An Adaptive Approach to Planning and Decision-Making.” Landscape and Urban Planning 40 (1-3): 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(97)00100-X.

- Månsson, J., L. Eriksson, I. Hodgson, J. Elmberg, N. Bunnefeld, R. Hessel, M. Johansson, et al. 2023. “Understanding and Overcoming Obstac ‘Understanding and Overcoming Obstacles in Adaptive Management.” Trends in Ecology and Evolution 38 (1): 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2022.08.009.

- McCarthy, M., and H. Possingham. 2007. “Active Adaptive Management for Conservation.” Conservation Biology 21 (4): 956–963. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00677.x.

- McFadden, D. 1986. “The Choice Theory Approach to Market Research.” Marketing Science 5 (4): 275–297. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.5.4.275.

- McFadden, J. E., T. L. Hiller, and A. J. Tyre. 2011. “Evaluating the Efficacy of Adaptive Management Approaches: Is There a Formula for Success?” Journal of Environmental Management 92 (5): 1354–1359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.10.038.

- McGraw, K., E. Hasecke, and K. Conger. 2003. “Ambivalence, Uncertainty and Processes of Candidate Evaluation.” Political Psychology 24 (3): 421–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00335.

- Moore, C., and M. Conroy. 2006. “Optimal Regeneration Planning for old-Growth Forest: Addressing Scientific Uncertainty in Endangered Species Recovery Through Adaptive Management.” Forest Science 52 (2): 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1093/forestscience/52.2.155

- Murray-Darling Basin Authority. 2023a. Adapting to Climate Change. Accessed 10th October 2023. https://www.mdba.gov.au/climate-and-river-health/climate/adapting-changing-climate.

- Murray-Darling Basin Authority. 2023b. Key Elements of the Basin Plan. Accessed 6th October 2023. https://www.mdba.gov.au/water-management/basin-plan/key-elements-basin-plan.

- NSW Water Management Act 2000. Accessed 12th October 2023. https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/act-2000-092#sec.8B.

- Pagan, P., and L. Crase. 2005. “Property Right Effects on the Adaptive Management of Australian Water.” Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 12 (2): 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/14486563.2005.10648637.

- Poposki, C. 2018. “Melbourne Desalination Plant Costs Tax-Payers an Eye-Watering $649 Million in Annual Operating Charges.” Daily Mail, 20 May. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-5749621/Melbourne-desalination-plant-costs-tax-payers-eye-watering-649-million-year-operate.html.

- Rolfe, J., H. Scarborough, B. Blackwell, S. Blackley, and C. Walker. 2021. “Estimating Economic Values for Beach and Foreshore Assets and Preservation Against Future Climate Change Impacts in Victoria, Australia.” Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 28 (2): 169–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/14486563.2021.1919232.

- Sinner, J., B. Bell, Y. Phillips, M. Yap, and C. Batstone. 2016. “Choice Experiments and Collaborative Decisions on the Uses and Values of Rivers.” Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 23 (2): 175–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/14486563.2015.1086963.

- Stringer, L., A. Dougill, E. Fraser, K. Hubacek, C. Prell, and M. Reed. 2006. “Unpacking “Participation” in the Adaptive Management of Social–Ecological Systems: A Critical Review.” Ecology and Society 11 (2): 39. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-01896-110239.

- Tocock, M., A. Borriello, D. Tinch, J. M. Rose, and D. Hatton MacDonald. 2023. “How Environmental Beliefs Influence the Acceptance of Reallocating Government Budgets to Improving Coastal Water Quality: A Hybrid Choice Model.” Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 30 (3-4): 348–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/14486563.2023.2248090.

- Tomz, M., and R. van Houweling. 2009. “The Electoral Implications of Candidate Ambiguity.” American Political Science Review 103 (01): 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055409090066.

- Walter, C., and R. Hilborn. 1978. “Ecological Optimization and Adaptive Management.” Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 9 (1): 157–188. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.09.110178.001105.

- Walters, C. 2007. “Is Adaptive Management Helping to Solve Fisheries Problems?” Ambio 36 (4): 304–307. https://doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[304:IAMHTS]2.0.CO;2

- Williams, B. 2011. “Adaptive Management of Natural Resources – Framework and Issues.” Journal of Environmental Management 92 (5): 1346–1353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.10.041

- Williams, B., and E. Brown. 2014. “Adaptive Management: From More Talk to Real Action.” Environmental Management 53 (2): 465–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-013-0205-7.

- Williams, B., and K. Brown. 2016. “Technical Challenges in the Application of Adaptive Management.” Biological Conservation 195 (C): 255–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.01.012.

- Wondolleck, J., and S. Yaffe. 2000. Making Collaboration Work: Lessons from Innovation in Natural Resource Management. Washington, DC: Island Press.