You have to listen to both versions, the Indigenous version of our history, and the non-indigenous version of our history, because they’re both telling the truth, but they’re both not the same story. (Don Christophersen, 2014)

This quotation, which closes the exhibition Encounters: Revealing Stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Objects from the British Museum (Encounters) at the National Museum of Australia (NMA), directly responds to Geoffrey Blainey’s simplistic categorisation of Australian history writing as either black armband or three cheers.Footnote1 Christophersen, an Indigenous Northern Territory man, reminds us that in order for one to have a true understanding of these debated histories, they need to occupy the same space,Footnote2 as Encounters and its partner exhibition at the British Museum (BM) demonstrate. The quotation is one of many which adorn the walls of Encounters highlighting the extensive consultation process the museum undertook with the Indigenous communities represented within it. Its placement at the end of the exhibition helps the viewer understand why there are so many voices in the exhibition, and why this is important.

Indigenous Australia: Enduring Civilisation (Enduring Civilisation) held at the BM ran from 23 April to 2 August 2015, and Encounters at the NMA, which ran from 27 November 2015 to 28 March 2016, are the products of a collaboration which began in 2007 with the aim of making the Australian collections at the British Museum better known and more accessible to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. The dual exhibition project was characterised by an in-depth consultation process over six years involving the 27 communities from the regions represented in the exhibitions.

Ultimately, the exhibitions linked by similar objects, artists and themes, developed quite differently. Enduring Civilisation was challenged by the small space it was given in the BM, which meant that at times the exhibition seemed cramped, and a British public whose knowledge of Indigenous Australia and Australian history was quite minimal. The premise of Enduring Civilisation was to introduce the audience to what the BM called ‘the remarkable story of one of the world’s oldest continuing cultures’, corresponding thematically to the BM’s trope of blockbuster exhibitions that explore great civilisations. The exhibition guided viewers through the small space using a series of themes, while introducing them to basic concepts such as country, the Dreamtime, and the ideas behind Western Desert acrylic paintings. While moving the viewer through these themes and concepts clearly and concisely, the exhibition also moved chronologically through key moments in history such as the landing of Captain Cook, the stolen generations, land rights and the referendum. This chronological sequence was constantly interrupted by contemporary objects, video and sound such as the Michael Cook painting Untitled #4 which was placed amongst objects collected by Captain James Cook (), reappropriating that moment of encounter from an Indigenous perspective. These interventions reaffirmed the aim of the exhibition to show that this is a continuing culture, an enduring civilisation.

Encounters, which featured 151 objects from the BM, wanted instead to explore the many stories about these objects, and the moments of encounter that surrounded their production, procurement and journey to the collections of the BM, highlighting how the stories form a part of the shared Indigenous and non-indigenous histories of Australia. The entrance of the exhibition led viewers in and up a central walkway through a large wooden fish trap, to one of the earliest moments of encounter between Gweagal people and Captain Cook (). Where Enduring Civilisation organised itself chronologically and thematically as a way of guiding viewers, Encounters was organised geographically and because of this, as well as the size of the exhibition venue, the exhibition had no fixed route, allowing viewers the freedom to explore. Each geographical space mixed historic objects with contemporary objects, videos, quotes and photographs to tell the story of that country through many voices and many perspectives, ultimately allowing the viewer to build up a rich history as they moved through the exhibition.

Figure 2. Encounters: Shield and Gararra (fishing spears) Gweagal people. Photo: Jason McCarthy, National Museum of Australia.

Importantly, neither exhibition shied away from the often contentious histories surrounding the acquisition of these objects and their placement in museum collections today. But, while many of the reviewers of both exhibitions have chosen to focus solely on these contentious histories and issues of repatriation as a means of criticising the exhibitions, they have overlooked the actual process of consultation that both of these exhibitions engaged with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. The exhibitions do not just select positive quotations from consultations to fit their narratives, but remarks that challenge and contest. They also actively include the work produced from contemporary artistic interventions that were a part of the consultation process.

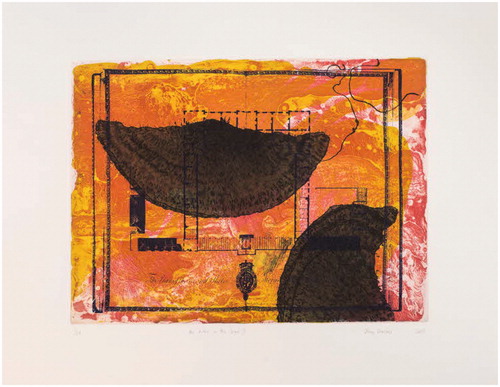

The NMA chose to hold a companion exhibition to Encounters that focused specifically on these artistic interventions, entitled Unsettled: Stories Within (Unsettled), featuring the work of Indigenous artists Elma Kris, Jonathan Jones, Judy Watson, Julie Gough and Wukun Wanambi. These artists were invited to the BM to produce work that explored the circumstances within which many of the objects were collected, such as Judy Watson’s hole in the land 3 () which overlays images of pituri bags in the BM collected on Watson’s country on to the plans of the BM and features in both Enduring Civilisation and Unsettled. The pituri bag shows a use of Aboriginal and settler material, and the print references the movement of the object off the land and into the BM, as well as its placement in the landscape of Queensland, as it would have been used. These artworks are critical to the exhibitions and ordered to explore the contemporary implications of these collections for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Figure 3. the holes in the land 3 by Judy Watson, 2015. Oc2015, 2004.3. Courtesy and Copyright Trustees of the British Museum.

Both Enduring Civilisation and Encounters wanted to ‘support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in re-establishing a connection with objects from the British Museum’s collection that were made by their ancestors’, and both have clearly done this.Footnote3 The contemporary bicornual basket made by Abe Muriata and the accompanying video of him talking about it which closed Enduring Civilisation, and the carved pole by Noel Wellington () in Encounters, spoke not just of re-establishing connections with collections but connections with ancestors and ideas of what it means to be from that country. The exhibitions were about engagements and how, as Yirandali man Jim Hill described in one of the quotes in Encounters, ‘when you talk about country, country talks [to you]’. Both exhibitions depicted as fully as possible these many stories that the country has to tell.

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ERC grant agreement n° [324146]11.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 Geoffrey Blainey, ‘Drawing up a Balance Sheet of Our History’, Quadrant 37, no. 7–8 (1993): 10–15.

2 Anna Clark and Stuart Macintyre, The History Wars (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2003).

3 Ian Coates, Encounters: Revealing Stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Objects from the British Museum (Canberra: National Museum of Australia Press, 2015), 16.