Abstract

The 1970s ushered in a period of significant feminist activism, public debate and judicial reform on issues of rape and child sexual abuse. In this article, I examine how The Australian Women’s Weekly raised and navigated the issue of rape from its commercial position as a conservative-leaning publication between 1970 and 1982. It seeks to understand mainstream Australian women’s attitudes towards sexual assault and how they evolved under emerging feminist critique.

The attitudes of the mostly male police forces and courts are still frequently contemptuous or disbelieving towards the victims of rape. The victim finds herself on trial for the crime that has been committed against her. It is iniquitous that the victim’s previous sexual history should be revealed in the courtroom, while the accused man’s previous history is considered inadmissible as evidence.Footnote1

In July 1980 The Australian Women’s Weekly published a four-page feature article ‘The legacy of anguish and broken marriages: Women talk about the trauma of rape’, detailing their perceived realities of rape for Australian women. The feature included statistical and anecdotal evidence collected from The Weekly’s Voice of the Australian Woman survey – a 230-question questionnaire dedicated to uncovering Australian women’s concerns and opinions on everyday issues. This provided considerable space for readers to share their harrowing experiences of sexual violence.Footnote2 The Weekly claimed to have received 30,000 responses from women across Australia, not all of whom were regular readers of the magazine, with an additional 10,000 letters providing comprehensive commentary on issues such as incest, rape and abortion.Footnote3 A letter (quoted above) from an unnamed Queensland woman was selected for a pull quote – ‘The victim finds herself on trial’ – poignantly encapsulating the two core themes The Weekly disseminated on sexual violence.Footnote4 These were the intersection of rape and the Australian law, and the understanding of rape as a traumatic experience. This article examines The Weekly’s coverage of rape to understand mainstream Australian women’s attitudes towards sexual assault throughout the 1970s and how they evolved under emerging feminist critique.

The Weekly has provided Australian women with a space to discuss a range of issues since its inception in 1933 and it has been a focus of many social, cultural and gender histories. Susan Sheridan’s exploration of The Weekly’s conceptualisation of Australian womanhood between 1946 and 1971 revealed how women were represented primarily through conservative gender roles.Footnote5 Kate Borrett’s examination of The Weekly’s coverage of female sexuality in the 1960s showed how the magazine constructed ‘commodified’ representations of ‘freedom’ and ‘revolution’, co-opted from the Women’s Liberation Movement.Footnote6 Denis O’Brien’s 1982 social history of The Weekly explored the magazine’s cultural influence in Australia through its evolving representation of womanhood. Despite O’Brien’s brief acknowledgement of Buttrose’s role in commissioning coverage on serious topics he does not examine The Weekly’s coverage of rape.Footnote7 Building upon this body of literature, I investigate how The Weekly navigated the issue of rape from its commercial position as a conservative-leaning publication and how this, in turn, illuminates Australian women’s attitudes towards sexual assault against the climate of the Women’s Liberation Movement.

There is limited scholarship on representations of sexual violence in The Weekly. In her book, Sexual Violence in Australia, 1970s–1980s: Rape and Child Sexual Abuse, legal historian Lisa Featherstone identifies the role the Australian media played in shifting conversations around sexual violence, suggesting these went from being held primarily in feminist spheres to making their way into mainstream discourse.Footnote8 Featherstone draws upon several articles from The Weekly to illustrate the role of the media in communicating feminist conceptualisations of sexual violence as a traumatic experience to a mainstream audience. My article provides a detailed close cultural analysis of The Weekly’s rape coverage, tracking how the issue evolved in the magazine’s reporting during this period of significant sociocultural change.

In her 2022 article, Leah Nichol examines rape narratives within The Weekly and argues that the magazine’s Voice of the Australian Woman survey replicated the Royal Commission on Human Relationships’ commitment to feminist ideology.Footnote9 However, her argument that The Weekly was engaging in a feminist project through the survey is questionable: while providing space for women to speak can be regarded as feminist, during this period The Weekly was also clear to distinguish itself from the Women’s Liberation Movement. In her 1998 autobiography, former editor-in-chief Ita Buttrose mused on the role of The Weekly as ‘a champion of women’s issues’ and a provider of Australian women’s ‘voice[s]’ in the seventies. However, she argued these actions were not viewed as feminist at the time.Footnote10 I argue The Weekly’s coverage of rape was not an intentional commitment to second-wave feminism; it was rather a reflection of the evolving sociocultural and legal attitudes towards sexual violence during this period. This is evident in how the magazine primarily framed its coverage through reader contributions and legal and political developments.

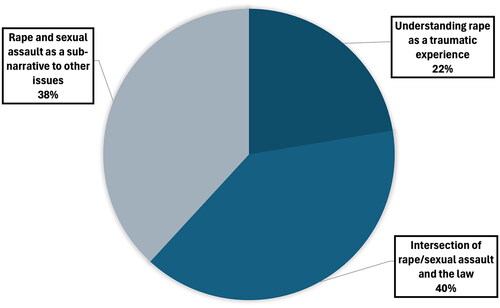

My research is grounded methodologically in cultural historical theory and historical newspaper analysis. Drawing from cultural history’s scholarly interest in ‘language, meaning and identity’, I consider how narratives of sexual violence were constructed and disseminated by The Weekly between 1970 and 1982.Footnote11 This period was chosen to capture a time in Australian history, which witnessed significant legal, political and sociocultural change regarding attitudes towards sexual violence.Footnote12 It concludes at the end of 1982 when The Weekly shifted to be a monthly magazine. My research was achieved by reading digitised copies of The Australian Women’s Weekly accessible through the National Library of Australia’s database TROVE. A data sample representative of The Weekly’s coverage of rape that contained 69 articles was collated using keyword searches. All issues of The Weekly between 1970 and 1982 were searched for the terms ‘rape’, ‘sexual assault’, ‘sexual abuse’ and ‘child sexual abuse’. The data sample was utilised for content and textual analysis allowing for the identification of three, often interconnecting, themes contained within The Weekly’s coverage of rape: first, the intersection of rape and the Australian law; second, rape and sexual assault as a sub-narrative to other issues such as abortion or risks when hitch-hiking; and, third, understanding rape as a traumatic experience ().

In this article, I initially discuss the political, cultural and legal context of rape in Australia during the 1970s. Then I demonstrate how The Weekly’s coverage of rape evolved significantly under Buttrose’s leadership, with her commitment to reflect a ‘revisioning’ of Australian women’s needs.Footnote13 Next, I highlight how The Weekly’s coverage of rape from 1975 to 1982 centred primarily on sexual violence and shifting developments within Australian law. Finally, I show how at the height of The Weekly’s coverage of sexual violence, the magazine positioned rape as a traumatic experience.

The seventies and rape discourse

Megan Le Masurier states ‘[m]agazines are not conceived and produced in isolation, out of time and place’.Footnote14 It is crucial to establish the political, cultural and legal context around rape to understand The Weekly’s coverage. The 1970s were a significant period of sociocultural change as global countercultural movements contested pre-existing attitudes towards gender, sexuality, race and class.Footnote15 In Australia, commonly held attitudes towards gendered and sexual violence were challenged by feminists, academics and politicians, leading to ample cultural and legislative change.

Michelle Arrow poignantly illustrates how the ‘seemly intractable problem of men’s violence towards their partners and children [was made] visible’ by feminist advocates during the early to mid-1970s.Footnote16 Conferences such as the Women and Violence Forum in March 1974 created spaces for women to share stories of physical and sexual violence experienced at the hands of their partners, fathers, brothers or family friends.Footnote17 Australian feminists quickly realised their advocacy required practical support for women experiencing men’s violence. Thus, they helped to establish women’s refuges, such as Elsie and the Melbourne Rape Crisis Centre in 1974.Footnote18 As Australian feminists recognised the lasting trauma victims experienced – from both the assault itself and their treatment by police, the courts and societal attitudes – feminist rape crisis centres played a crucial role in providing ongoing emotional support and care.Footnote19

Second-wave feminism was essential to reconceptualising rape as both ‘a crime and social problem’.Footnote20 American feminists argued rape existed in every aspect of western culture with ‘[t]he media, advertising, and pornography all promot[ing] violence against women, and the use of women as objects’.Footnote21 The idea of rape as a sociocultural issue gained widespread attention with Susan Brownmiller’s 1975 book Against Our Will, which positioned rape as ‘a conscious process of intimidation by which all men keep all women in a state of fear’.Footnote22 Similarly, Australian feminists made connections between ‘power, chauvinism and sexual assault’, articulating how gender norms reinforced social conditions which condoned a culture of rape. Thus, Australian feminism contended rape ‘represented a wider culture that saw men as having rights over women’s bodies’.Footnote23 Feminist advocacy identified how women were often blamed and held responsible for their own assaults. Lisa Featherstone uncovered how the Sydney Women’s Liberation Newsletter challenged these social attitudes by conceptualising the notion of victim blaming through a series of myths regarding sexual assault.Footnote24 These included: ‘it is impossible to rape a woman’, ‘women attract rape by the way they dress’ and ‘rapists are strangers’.Footnote25 Australian feminists argued such rhetoric impacted rape victims’ ability to come forward and receive support. Feminist understandings of sexual violence moved beyond feminist circles with its incorporation in criminology and legal scholarship.Footnote26 The prevalence of rape mythology and ideas of victim blaming were a key concern for criminologists focusing on the impact of rape on victims and society’s view of sexual assault. This is evident in American criminologists Julia Schwendinger and Herman Schwendinger’s research, which demonstrated how women were victimised ‘twice’ by rape myths, suffering remarks such as ‘she was asking for it’ or ‘the offender was overcome by uncontrollable passions’.Footnote27 In 1975 Australian criminologist John Noble argued societal attitudes which perceived rape victims as (partially) responsible for their assaults was contributing to the underreporting of sexual offences.Footnote28

The issue of rape within the context of marriage began to receive mainstream attention through its debate amongst law scholars and politicians. This is evident in feminist law scholar Jocelynne Scutt’s work which advocated for rape law reform in academia, the media and government inquiries.Footnote29 Scutt asserted ‘[t]here is no legal justification for a rule that a husband cannot be prosecuted for the rape of his wife’.Footnote30 The issue of marital rape gained prominent attention amongst the public with South Australia’s Mitchell Report (1976) which ‘strongly condemned the idea that a woman had, through marriage, committed herself to indefinite vaginal and anal sex’.Footnote31 The report advocated for legislative change to remove the ‘immunity against a husband being prosecuted for raping his wife’.Footnote32 However, the proposed reforms faced fierce opposition from religious and conservative groups including the South Australian Women’s Council of the Liberal Party and the Anglican Church. They argued these laws were an attack on the family, an undermining of the institution of marriage and ‘a dangerous weapon [in] the hands of a vindictive wife’.Footnote33 As a result, the legislation was watered down with South Australia partially criminalising marital rape in 1976, including a clause that required the presence of some form of a threat or physical harm to constitute rape in these circumstances.Footnote34 As law scholar Peter Sallman asserted at the time, while ‘the principle of rape within marriage has been established’ the wording of the legislation ‘leaves open a wide variety of interpretations’.Footnote35

The Royal Commission on Human Relationships demonstrates how feminist reconceptualisations of sexual violence entered into mainstream discourse by the mid-to-late 1970s. Launched by the Whitlam Government in 1974 led by Justice Elizabeth Evatt, Dr Felix Arnott, and Anne Deveson it intended to investigate and ‘capture ordinary people’s experiences of intimate and private life in order to support a case for legislative and social change’.Footnote36 The Commission received over 1,264 written submissions, conducted thousands of short informal interviews and heard evidence from 374 people in public hearings on a range of issues including rape, domestic violence and child abuse.Footnote37 The Royal Commission on Human Relationships’ five-volume Final Report presented in 1977 emphasised the need for substantial reform, arguing ‘a completely new approach to sexual offences [b]oth in the legal and the social context’ was necessary to tackle the issue of sexual violence in Australia.Footnote38 The commissioners echoed feminist thought, acknowledging how ‘[c]ommunity attitudes can contribute to … the crime [of rape] itself and … may aggravate the distress and humiliation of the victim’.Footnote39 Thus, the commissioners recognised the link between a ‘substantial lack of understanding about rape in [the] community [with rape] often seen to be a sexual act, rather than a violent one’ and the reality of rape as an underreported crime.Footnote40

The Royal Commission made 57 recommendations on rape and other sexual offences including the ‘need to redefine rape’, suggesting that ‘[s]exual penetration should be defined to include all forms of vaginal, anal and oral intercourse, including the insertion of foreign objects into the victim’s anal or vaginal cavities’.Footnote41 The commissioners recognised the feminist understanding of rape as a traumatic experience, stating a ‘woman who has been through the trauma of rape needs sympathetic and sensitive treatment’ and they called for measures to be put in place to minimise harm to victims when interacting with both the police and the courts.Footnote42 The report also acknowledged the injustice of the ‘presum[ption]’ women ‘have consented to acts of intercourse’ based on their marital status and that the law should protect both the privacy of marriage and the ‘individual against unwanted intercourse’.Footnote43 The Royal Commission was crucial in taking Australian feminist discourse on sexual violence and allowing for the implementation of legislative and policy change. Thus, from the late 1970s reforms to sexual offences were introduced across the nation including ‘expanding the definition of sexual assault’, ‘reconsidering the treatment of [rape] victims in the courtroom’ and the criminalisation of rape within marriage such as in New South Wales (1981) and Victoria (1985).Footnote44

The Weekly, the seventies and rape

Chelsea Barnett asserts the 1970s is often understood in popular memory as a decade of ‘upheaval and change’.Footnote45 This certainly was the case for The Weekly. The magazine underwent significant development as cultural attitudes on Australian womanhood shifted, and a reformatting of the paper and changes in leadership allowed for a younger editorial voice.Footnote46 In the early 1970s The Weekly, led by Esmé Fenston, had fostered an ‘affinity’ with readers, ensuring the magazine catered to the needs of suburban Australian families by appealing to both men and women.Footnote47 Having assumed the position as editor in 1950, Fenston firmly believed The Weekly’s role in Australian society was to reflect, not shape, public sentiment by ‘gradually mov[ing]’ with the times. This was evident throughout the 1960s as articles concerning contraception slowly began to be published.Footnote48 After Fenston’s unexpected death in April 1972, Dorothy Drain was appointed interim editor.Footnote49 Little changed under Drain’s leadership. She was not sympathetic to the Women’s Liberation Movement, and The Weekly continued to produce coverage deemed beneficial to middle-class housewives and mothers.Footnote50 However, despite its significant cultural influence, The Weekly was in serious economic trouble at this time, impacted by declining circulation figures and a world paper shortage that increased production costs. In March 1975, following Drain’s resignation, Kerry Packer (then proprietor of Consolidated Press, The Weekly’s parent company) took drastic action, appointing Buttrose, the magazine’s youngest editor. In August 1975 he also downsized the magazine by 33 per cent from its original size.Footnote51

Under this new configuration, The Weekly thrived and came to be regarded as the ‘bible’ for Australian women, asserting a ‘strong’ and ‘authoritative’ voice that was respected and had the ‘ability to sway people’s minds’.Footnote52 The Weekly was circulated into ‘one in four homes’ and was read by ‘almost 45 per cent of all women fourteen and over, and 20 per cent of all men fourteen and over’ in Australia.Footnote53 The Weekly’s readership throughout the 1970s was comprised primarily of middle-class heterosexual white women.Footnote54 Buttrose understood her readers as ‘being from the middle ground’, and that they ‘were not bent on taking over the world, nor … motivated by bitterness’.Footnote55 Buttrose realised that while shifting cultural ideas were influencing Australian women in the 1970s, many still held deeply traditional views on gender and family, and The Weekly’s coverage was committed to conform mostly to this reality.

The 1970s saw a significant rise in women’s media with the establishment of publications which appealed to young and progressive Australian women such as Cleo (1972) and Cosmopolitan (1973). The Weekly’s sister publication Cleo under the editorship of Ita Buttrose aimed to ‘produce a magazine for women under 40 with a liberal feminist editorial agenda, washed through with the less revolutionary ideas of Women’s Liberation’.Footnote56 Buttrose platformed feminist concerns to her mainstream audience publishing stories on sex, contraception and domestic violence which proved to be lucrative: Cleo achieved a ‘circulation of 234,000 by the end of its second year, [which] held throughout the decade’.Footnote57 Furthermore, Megan Le Masurier’s research on Cleo in the 1970s reveals how young Australian women engaged with feminist ideas through women’s magazines by participating in dialogues on Women’s Liberation, gender equality and notions of femininity.Footnote58 The success of Cleo’s popular feminism paved the way for Buttrose to slowly integrate liberal ideas from second-wave feminism including those on rape, into The Weekly’s coverage under the guise of catering to Australian women’s interests and needs. Buttrose’s coverage of rape primarily reflected the sociocultural change taking place in mainstream Australian women’s attitudes towards sexual violence creating conditions for such discussions to take place in the commercial conversative-leaning publication. However, Buttrose made some editorial choices, which helped to gently shape Australian women’s attitudes towards sexual violence by making the issue a palatable concern for more conservative readers. This is evident in The Weekly’s decision to frame issues of sexual violence through readers’ contributions, legal developments and political debates. This in turn helped position anti-rape advocacy as a concern for ordinary Australian women, which was yet detached from the Women’s Liberation Movement.Footnote59

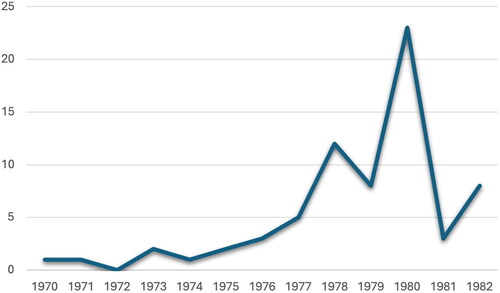

The Weekly’s coverage of rape evolved significantly under Buttrose’s leadership, with her commitment to reflect the emerging needs of Australian women alongside major cultural shifts in legal and political spheres relating to sexual offences.Footnote60 O’Brien identified how under Buttrose The Weekly gradually introduced coverage of the ‘dark realities of life’ with articles on issues including cancer, alcoholism and rape.Footnote61 This is reflected within my data sample which illustrates the gradual increase in The Weekly’s coverage of rape and child sexual abuse, with the height of its reporting taking place in 1980 as a result of the Voice of the Australian Woman survey (). Buttrose, despite being made editor-in-chief of Consolidated Press’ women’s publications in 1976, maintained a close relationship with The Weekly, remaining its face and working closely with its day-to-day running even when Dawn Swain was officially appointed to her old role.Footnote62 The notable decrease in coverage of rape captured in the data sample, which occurred in the final two years of The Weekly as a weekly publication coincided with Buttrose’s resignation from The Weekly at the end of 1980.Footnote63 The trend of moving away from featuring weightier topics, such as rape, can be understood through the role Buttrose played as editor in shaping The Weekly’s coverage.

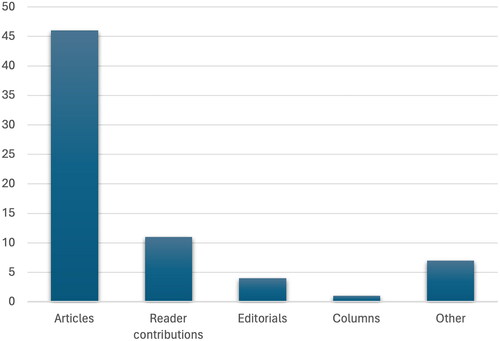

The Weekly’s investment in coverage of sexual violence under the leadership of Buttrose tended to place these stories in feature articles or editorial content (). Its trend of covering sexual violence in relation to specific legal developments or political reports points to The Weekly’s clear intention to distinguish itself from the Women’s Liberation Movement. The Weekly perceived their reporting of sexual violence as newsworthy journalism catering to what Buttrose regarded as Australian women’s needs rather than a feminist ideological position.

There was a significant tonal shift around how issues of sexual violence were discussed in The Weekly following Buttrose’s appointment as editor. As demonstrated, The Weekly’s coverage of issues of rape can be understood through three themes: the intersection of rape and the Australian law; understanding rape as a traumatic experience; and early in the decade decentring sexual violence in relation to other issues such as abortion (). This is evident in a November 1973 article detailing the results from an Australian survey on opinions regarding three contentious issues – abortion, marijuana, and divorce – which mentioned how Australians regarded rape as an acceptable reason to seek an abortion.Footnote64 Furthermore, some of The Weekly’s casual and flippant references to rape contained victim-blaming rhetoric. This can be seen in a June 1971 article on dating which was syndicated from Helen Gurley Brown’s 1970 book Sex and the New Single Girl which stated, ‘lingerie hanging on the bathroom door or across a chair in the bedroom’ could ‘encourage rape’.Footnote65 The decision to publish this extract illustrates the normalisation of attitudes that women’s actions or clothing can provoke the sexual assault.

Although a majority of The Weekly’s coverage of rape in the early 1970s centred around other issues, a reader contribution from December 1973 was an exception. A Townsville reader, B. Rennie, lamented discrimination against women on rape trial juries.Footnote66 Her letter was a response to a fellow reader, O. Woolcock, who shared her dismay regarding women’s reluctance to attend jury service. Rennie lamented being refused the right to serve on juries of rape cases in Townsville.Footnote67 Rennie posed the rhetorical question: ‘[w]hy shouldn’t a woman be as objective as a man on such a case?’. Her letter highlighted the absurdity of Australian jury laws, especially with regard to adjudicating crimes that particularly affected women. This reader’s experience was not uncommon. Andrew Choo and Jill Hunter have noted that common law countries, such as Australia, had ‘very low’ representation on juries, despite women gaining the ability to opt into jury rolls.Footnote68

The Weekly’s coverage of rape in the early to mid-1970s was minimal and tended to be discussed alongside other issues such as abortion. Furthermore, it illustrates how normalised attitudes that rape victims were culpable in their assaults were amongst Australian women.

Rape: the law and calls for reform

The Weekly’s coverage of rape from 1975 to 1982 centred around sexual violence in relation to shifting Australian law. This coverage informed Weekly readers of their legal rights – or lack thereof – and explored notions of policing and protection. In September 1975, The Weekly published a ‘wanted’ flyer for a man suspected of committing a series of rapes and an attempted murder of young women in Victoria.Footnote69 This report was unprecedented for The Weekly, with limited prior coverage on issues of rape. The unusual nature of the piece was even acknowledged by Buttrose in her editorial, which informed readers of her hesitancy to publish the flyer as requested by Victoria Police ‘as rape is not a pleasant subject’.Footnote70 She justified The Weekly’s editorial decision by positioning rape as a concern for her readership, as rape is ‘one of the most hideous offences that can be committed against a woman’. Buttrose stated The Weekly ‘felt that it was in the public interest’ to run the flyer with the man’s picture and urged its readers to come forward to police with any information on the crimes.Footnote71 The decision to dedicate a full page to the report, located towards the front of the magazine on page 7, as well as Buttrose’s editorial on the case, reinforces the notion that The Weekly under Buttrose came to deem rape a newsworthy subject. The report, while produced by Victoria Police, revealed how The Weekly constructed representations of rape to its readers. It suggested women were at high risk of random acts of violence, emphasised by the detectives’ statement that ‘all women, anywhere who find themselves alone in their houses or with only young children for company’ are to remain on high alert.Footnote72 It urged the need for precautions, with women told to protect themselves by ensuring all doors and windows were locked, houses well-lit and blinds kept drawn. The seriousness of the threat was reinforced when the report informed women who are attacked ‘to avoid panic or any action which might further endanger [their] safety’.Footnote73

The Weekly provided no editorial commentary on the actual content of the report or any additional coverage detailing the realities of rape. Its initial representation of rape, portraying young women at risk of being assaulted at random, reinforced the idea that sexual assault was usually perpetrated by a stranger.Footnote74 This myth, theorised by feminists, provides language to the phenomena of women (and men) being dismissed or having their credibility undermined due to the circumstances revolving around their assault not reflecting this stereotype. This representation of sexual violence stands in stark contrast to the realities of rape in Australian society. In 1980, results from The Weekly’s Voice of the Australian Woman survey revealed that the majority of Australian rape victims were assaulted by someone known to them, such as a casual acquaintance, friend or husband.Footnote75

The Weekly’s coverage of sexual violence during the late 1970s informed readers of their rights, responsibilities and protections under Australian law in relation to sexual offending. In May 1978, the multi-page feature ‘What Australian women should know about marriage’, extracted from Barbara Bishop and Kerry Petersen’s book Pink Pages, discussed Australian women’s rights as married or single women under Australian law. The Weekly utilised this syndicated resource to demonstrate the varied ‘rights available to married women and women who are unmarried but living in stable, long-term relationships’, including those relating to sex.Footnote76 Readers were informed that under current Australian law as a married woman ‘you can’t refuse your husband sex while you are living together’ with the exception of women living in the jurisdiction of South Australia. This was reinforced later in the article under the subheading ‘Rape within marriage’, which informed Australian women that the act of marriage under the law implies you ‘consent to have sexual relations with your husband’.Footnote77 The Weekly’s inclusion of this excerpt emphasised the significance of legal protections afforded to women living in South Australia as it is the ‘only place in the world where a man can be charged with raping his wife’. Readers were informed there were only two ways an Australian married woman (outside of South Australia and Western Australia) may prevent her husband from having non-consensual sex: ‘apply to the family court for an injunction’ or leave your home. The article spent a couple of lines communicating the rights women have to protect their children from violence or molestation under the Family Law Act.Footnote78 However, readers were made aware of the failures of policing in protecting children from abusive fathers with police ‘reluctant’ to involve themselves in what they consider ‘domestic disputes’. Readers were informed that despite rape being against the law unmarried women would find justice ‘unlikely’ in a courtroom ‘unless there was clear proof of physical violence’. Similarly, the article emphasised that while women in de facto relationships can report rape the police would be ‘reluctant’ to take the case ‘unless there was very clear evidence that violence was involved’.Footnote79 Women in these circumstances were advised to leave the relationship. This syndicated article communicated to Weekly readers that while there are some protections for women and children against sexual violence, Australian laws were lacking and varied based on jurisdiction and circumstance.

From the late 1970s, Australian women were concerned with protecting themselves from perceived or actual threats of sexual violence. The August 1981 two-page feature ‘How to defend yourself and your home’ informed readers that sexual violence was increasing in Australia and all women needed to take ‘basic safety precautions’ against assaults and burglaries.Footnote80 The Weekly emphasised both the urgency and perceived necessity for the article, stating in the opening paragraph ‘[e]very day in Australian women are attacked, molested and raped’—with 938 rapes reported to police in 1978 alone. The Weekly included the Rape Crisis Centre in New South Wales’ estimate that ‘around 70 per cent of rapes are never reported’, thereby communicating that sexual violence was an even greater issue than the crime statistics portrayed.Footnote81

Despite this report – positioned as a ‘common sense guide to protecting yourself, your children, and all your possessions’ – the article was also filled with judgement, victim-blaming rhetoric and suggestions of culpability in survivors. The Weekly judged Australian women who have been attacked, either physically or sexually, by implying if they had learnt how to ‘minimise danger’ and not ‘ignored’ common sense safety tips they could have avoided their experience. In the second paragraph journalist Sandra Moore asserted: ‘you don’t have to be a victim. Accept that we live in an age of violence and learned to protect yourself. Too many attacks are made on people who didn’t bother to take basic safety precautions’. Such rhetoric shifted culpability from (largely) male perpetrators of violence to victims – predominantly women and children. The Weekly’s readers are provided a list of safety tips to ‘avoid danger’ such as ‘avoid walking alone late at night’, ‘[n]ever ride in a railway carriage alone or with just one other person’ and ‘[w]hen at home keep the doors locked’. These precautions, listed alongside a half-page image depicting a man grabbing a woman from behind in an attempt to forcibly move her towards him, reinforced the notion of ‘real rape’ as a violent act, which is committed by a stranger in a dark public space.Footnote82 The Weekly failed to consider the underreporting of rape or notice how the tone and representation of sexual violence contained in this article may contribute to this statistic by breeding shame and shifting blame for sexual violence. This article illustrated how despite sexual violence becoming a key issue for The Weekly, it still produced misleading and potentially harmful coverage.

Spurred by political developments, the magazine also platformed critiques of the current judicial and policing systems to emphasise the need for rape law reform. In July 1977, The Weekly’s Daphne Guinness interviewed Queensland Liberal MP Rosemary Kyburz for a two-page feature following Kyburz’s provocative comments against Queensland rape laws.Footnote83 Kyburz’s grabbed the attention of the Australian media and brought the issue of rape law reform to the public’s attention when she told a group of women from the country town of Ingham protesting sexual violence that they should ‘try to maim or kill rapists attacking them’.Footnote84 Guinness informed The Weekly’s readers of how Kyburz’s inflammatory comments sparked Queensland Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen to commit to pursuing reform to the state’s rape laws, such as removing references to ‘the victim’s past history’. However, Kyburz, whilst acknowledging the Premier’s attempts to bring forward rape reform in Queensland, argued changes needed to go further and proposed that victims should be able to present evidence in written form, that rape trials be held within three months of the committal and that there be ‘no cross-examination of a woman on her prior sexual experience’.Footnote85

Guinness humanised Kyburz to readers by discussing her conventional looks, unconventional marriage (with her husband undertaking the housework) and her resilience as she lived with migraine attacks.Footnote86 However, Guinness did provide some critique of Kyburz’s work on rape reform, arguing that her provocative comments opened her own self up to rape. Guinness informed her readers how Kyburz’s ignored such criticism and was driven by Australian women who reached out to share their experiences. The article concluded with the ‘overwhelming’ amount of letters Kyburz’s received on the issue of rape, such as one from a father arguing that pictures of girls in bikinis in the newspaper encouraged rape. The Weekly provided no editorial comment, nor mentioned Kyburz’s own response to the letter, thus allowing the false belief that clothing causes sexual violence to go unchallenged. The Weekly’s belief that Rosemary Kyburz’s campaign for rape law reform in Queensland was of interest to their readers is evident in its placement as a double-page spread on pages 2 and 3 of the issue. The magazine anticipated that the issue of sexual violence may directly impact some readers by providing an information box at the end of the article with a list of numbers for rape crisis centres around the country.Footnote87 Thus, by 1977 it is evident how The Weekly was beginning to take the issue of rape seriously within their publication and how feminist understandings of sexual violence were being incorporated into mainstream discourse.

In August 1980 The Weekly published an informative article detailing proposed changes to New South Wales rape and sexual assault legislation. The Women’s Advisory Council, set up by the New South Wales Premier, was tasked with drafting a set of changes to the state’s rape laws to tackle underreporting and minimise the harm victims experienced when navigating the legal system. The Weekly’s Robin Oliver spoke with the Women’s Advisory Council’s chairperson Kaye Loder about the proposed reforms, including changing legal terminology for sexual offences with ‘sexual assault’ proposed to replace the term ‘rape’ to reflect its violent nature. Reforms also introduced grades of offences to indicate seriousness and improve prosecution rates.Footnote88 Loder explained the Council’s position towards ‘gender neutrality’ and equality in sexual assault legislation, asserting it is ‘essential that we get away from overtones of man against woman in dealing with sexual assault. It must be seen as one against another’, as was the case with other criminal offences.Footnote89 The Weekly’s inclusion of this quote marks a significant shift in the conversation of sexual violence within The Weekly, as previous coverage had framed the issue of rape and sexual assault as a women’s issue. This position of gender neutrality would see ‘both men and women … enjoy the full protection of the law’ and the outlawing of marital rape. The Women’s Advisory Council acknowledged how sexual assault was an underreported crime in Australia and proposed reforms to address barriers to accessing the legal system, such as limiting cross-examination of victims’ prior sexual history and preventing the media from publishing reports that identify the victim. The Weekly concluded the article by informing their New South Wales readers that they could have a say on the proposed changes at a public hearing in late September and early October.Footnote90

Despite The Weekly centring a large portion of their coverage of rape around the Australian legal system, with an emphasis on the need for law reform, they did not report South Australia’s partial criminalisation of marital rape in 1976, nor cover New South Wales’ outlawing of marital rape in 1981.Footnote91 While later coverage of rape in the magazine noted both, the magazine omitted real-time reporting on these significant changes.Footnote92

The Weekly committed to its role as a forum for women’s issues by allowing space for readers who were hesitant about calling for rape reform. On 10 August 1977, The Weekly’s published a letter from Queensland reader Hazel Jamieson, which shamed rape victims for taking ‘needless risks’ such as hitch-hiking.Footnote93 Despite Jamieson acknowledging that Australian women who have not experienced sexual violence are unable to ‘fully understand the feelings’ of others, she continued to engage in victim-blaming rhetoric by implying ‘girls’ open themselves up to the threat of sexual violence by engaging in risky behaviour.Footnote94 The use of the term ‘girls’ rather than women also holds an undertone of victim blaming, implying Jamieson and women like her are more mature and responsible and therefore would not open themselves up to the threat of rape.Footnote95 Such rhetoric highlights the prevalence of societal attitudes in which rape victims are deemed culpable for their assaults as reflected in the Sydney Women’s Liberation Newsletter’s February 1975 list of (mis)beliefs women held towards sexual assault such as ‘women attract rape by the way they dress’.Footnote96 Jamieson’s letter was published in the month following the feature article on Rosemary Kyburz’s calls for rape law reform in Queensland. It illustrated how some Australian women thought calls for rape law reform was unnecessary. However, despite the victim-blaming stance, Jamieson’s view was complex as she also contended that society ‘should educate the boys to avoid situations where they are tempted to disregard the legal and moral codes’.Footnote97

The Weekly’s coverage of rape from 1975 to 1982 centred around sexual violence in relation to Australian law. This reporting was spurred by a change in editorship, and by significant legal and political conversations relating to rape legislation. It demonstrated how feminist understandings of sexual violence entered mainstream discourse through legal and political debates.

Understandings of rape as a traumatic experience

The Weekly’s coverage of rape evolved throughout the late 1970s to include a discussion of the trauma of sexual violence. The Weekly’s focus on rape as a traumatic experience was not explicitly linked to the Women’s Liberation Movement, despite it being an inherently feminist conceptualisation.Footnote98 Instead, just as The Weekly used Australian law to discuss rape, the magazine utilised legal and political developments to bring reader attention to rape trauma. In their 1978 two-page feature article on the International Women’s Day Lunch in Sydney, the magazine distinguished to their audience the difference between caring about women’s issues such as rape and divorce reform and being a part of the established Women’s Liberation Movement. Journalist Jenny Irvine opened the piece by asserting the ‘aggressive bra-burning attitude of women’s libbers in the early 1970s is a thing of the past’ and that those who are truly concerned about women’s liberation focused on both their roles as wives and mothers alongside attaining equality within society.Footnote99 This distinction was reinforced by a woman in attendance at the lunch who stated she would be ‘horrified’ to be ‘tabbed a women’s liberationist’ but that like ‘all women [she] care[s]’.Footnote100

Buttrose’s reflections on her time as editor at The Weekly in her 1998 memoir reveal her hostility towards the Women’s Liberation Movement and that The Weekly was not engaging in feminist politics but instead providing Australian women with a voice on issues that impacted their lives.Footnote101 Irvine reported on New South Wales Premier Neville Wran’s speech at the lunch in which he announced proposals to prevent discrimination against women. The Weekly emphasised specifically the proposal for reforms to rape legislation, which would ‘concentrate mainly on the psychological trauma suffered by the victim’.Footnote102 By including Wran’s comments that rape is an underreported crime due to the current interrogation and medical examination processes being ‘simply too much to bear’ for victims, The Weekly explicitly linked the experience of rape with trauma.Footnote103 Irvine’s article revealed how by the late 1970s feminist conceptualisations of sexual violence had become detached from feminist ideology in the media and had been incorporated into mainstream discourse on the issue. Thus, the magazine made sexual violence advocacy palatable for their conservative readers by framing rape as a mainstream women’s issue.

In May 1978, The Weekly published a three-page feature article illustrating rape victims’ suffering, which centred around a government report on the trauma women faced when reporting rape in New South Wales. Lisa Featherstone asserts that despite ‘inflated’ and ‘sensationalised’ language throughout the article, The Weekly used this feature intentionally to draw readers in and still maintain a serious tone.Footnote104 It included statistics, expert opinions, and personal anecdotes, all highlighting both the reality of rape in Australian society in the mid-1970s and its impact on victims.Footnote105 The Weekly’s journalist Rose Munday offered a snapshot of the ‘ordeal’ of reporting rape in Australia by interviewing three experts: South Australian doctor Aileen Connon, South Australian detective Anne Buring from the Rape Enquiry Unit, and Queensland sociologist Paul Wilson who researched unreported rapes.Footnote106 Readers were guided through the painful and ‘humiliating’ process of reporting to police, which included details of the medical examination to emphasise the horrific nature of rape, with Dr Aileen Connon stating ‘vaginal, oral and anal assault’ were common types of sexual assault in Australia.Footnote107 The article provided a glimpse into the trauma adult victims of sexual assault experienced in court and under cross-examination via a quote by The Weekly’s own Margot Lang, a former court reporter: ‘the odds are still against a woman rape victim in the courtroom’. Lang saw that the limitless cross-examination of victims left many of them ‘sobbing’. The Weekly dedicated a separate space in the piece to focus solely on the trauma experienced by child sexual abuse victims. Dr Wilson’s expertise was used to inform the readership that victims are most likely to be abused within their own homes. It told how the required medical examination can worsen the trauma child sexual abuse victims face and legal actions can cause ‘further harm’ when victims are subjected to cross examination when giving evidence.Footnote108

The Weekly also discussed harmful myths about rape that existed within the community, such as ‘there is no such thing as rape – the victim must surely have been a willing partner at some stage’.Footnote109 Through this article, we can see how The Weekly’s reporting of rape has evolved to include a critique of rape myths that their previous coverage had reinforced. However, there is no acknowledgement that this critique had emerged from the feminist movement. Despite The Weekly engaging with feminist concepts in their coverage of sexual violence they were hesitant to paint these issues as feminist to their readership. The article concludes with another mixed message by providing readers with details about rape crisis centres across the country, which were inherently feminist organisations.Footnote110 This feature highlighted how The Weekly’s coverage of rape was evolving to consider feminist notions of the impacts sexual violence has on victims even while it denied the influence of the Women’s Liberation Movement. Regardless of whether The Weekly’s editorial team or readers read this piece as feminist it was a meaningful intervention advocating against the harms of sexual violence by explicitly linking rape to the notion of trauma.Footnote111

The Weekly’s coverage of sexual violence, which emphasised the victim’s suffering and trauma, was spurred on in part by the magazine’s own readers. Written contributions provided The Weekly both with content on sexual violence and permission to dedicate space to this serious yet contentious issue. This is most evident in 1980 with statistical and anecdotal evidence emerging from The Weekly’s Voice of the Australian Woman series. Buttrose, believing Australian women deserved to have their ‘point of view heard’, conceptualised a 230-question survey dedicated to uncovering Australian women’s opinions on everyday issues and social topics such as health, abortion, marriage, family, and sex.Footnote112 The survey was constructed with considerable space dedicated to collecting Australian women and girls’ experiences of sexual violence with questions 165 through 191 relating to the topics of rape and child sexual abuse specifically incest.Footnote113 These questions sought Australian women’s attitudes towards sexual violence, their experiences with the police and legal system and details surrounding their assaults such as their age at the time, their relationship to the perpetrator and how they responded following the assault.Footnote114 The Weekly invited readers to respond to questions through a tick-box format, including yes/no and agree/disagree options and also allowed readers to elaborate on their answers by writing to the magazine.Footnote115 The response was significant with 30,000 returns from women across Australia and an additional 10,000 letters filled with comprehensive commentary on issues such as incest, rape and abortion.Footnote116 O’Brien’s study of The Weekly emphasised the wide range of opinions which were conveyed in the contributions and Buttrose’s observation that the survey result ‘differs dramatically and significantly from the conditioned view of the Australian female’.Footnote117 Buttrose ‘insisted’ Swain publish feature articles catering to their readership’s substantial response to the issues of rape and incest.Footnote118

In April 1980, The Weekly duly published a seven-page feature, ‘Incest: the hidden crime you wanted brought into the open’, highlighting the trauma and suffering that members of its readership had experienced. The piece opened with a letter from Buttrose to readers, asserting the gravity of incest in the Australian community and the importance of addressing the topic even despite its difficulty. Buttrose emphasised that this is the first time The Weekly had addressed the topic of incest in detail and that it did so as a direct response to the readership’s call to ‘bring this crime out into the open’.Footnote119 The Weekly informed its audience how their Voice of the Australian Woman survey revealed that incest occurs primarily between a brother and sister or father and daughter, most victims were under the age of 15 when the incest first occurred and young women between the ages of 15 to 19 are ‘especially prone to avoid reporting’ to the police.Footnote120 The Weekly emphasised the trauma associated with incest via bolded subheadings such as ‘readers who have been victims of incest open up their hearts to tell of the misery, the guilt and the hopelessness’.Footnote121 The last four pages of the piece were dedicated solely to personal anecdotes communicating the shame, fear and mental suffering victims experience both at the time of the abuse and in subsequent years.Footnote122 Furthermore, quotes placed in bold, such as ‘my uncle did untold damage to me’ as headings for each of the anecdotes emotionally pulled in readers and reinforced the connection between trauma and sexual abuse.Footnote123 The Weekly supplied a list of resources available to help victims of incest and their families.Footnote124 While The Weekly engaged with the feminist notion of sexual violence being a traumatic experience there was no explicit acknowledgement of this throughout the article.

On 23 July 1980, a four-page feature article, titled ‘The legacy of anguish and broken marriages: women talk about the trauma of rape’, split into three broad sections, detailed the realities of rape in Australia, the process of reporting rape and of navigating the courts, and what Australian women think should be done with rapists. The piece relied heavily upon the Voice of the Australian Woman survey results and reader’s letters as evidence and attempted to convey the trauma of rape to readers. It revealed to their audience how according to their survey eight out of every 100 women in Australia have been victims of rape, with most assaulted by either a friend or a casual acquaintance.Footnote125 The Weekly reported that 91 per cent of women who participated in the survey believe ‘unpleasant attitudes’ from the police and law courts discourage victims from reporting rape.Footnote126 The findings communicated how Australian women wanted more ‘severe’ penalties for rape and held strong support for the criminalisation of marital rape.Footnote127 Through a selection of 38 letters chosen by The Weekly’s editorial team, it communicated common attitudes Australian women hold towards rape and how their own readers’ ‘lives were changed, and their attitudes altered by the aftermath of [their] assault’.Footnote128 A woman from country Victoria wrote on why she chose not to report rape, explaining it is ‘humiliating’ going to the police and that the processes of questioning rape victims ‘prolong[s] the pain’. Another reader from Melbourne explained how multiple men raped her and her friend when hitch-hiking and that they did not fight fearing ‘being physically hurt’. This reader’s letter echoed the shame and blame many rape victims experience; she went on to reveal their decision not to report was based on the belief that the police would be unsympathetic and on not wanting to ‘hurt’ their families or friends ‘by publicising our misfortunes’.Footnote129 The notion of shame was reinforced in the following letter from a NSW woman aged between 35 and 44 who recalled her experience dealing with the police after her rape by a stranger at 12. She expressed the shock and terror she felt when being interviewed, having her underwear taken away, and not being provided any emotional care.Footnote130

The Weekly pointed out that while the survey revealed ‘a forceful [no] response’ to the question ‘do women who get raped ask for it?’ − 95 per cent disagreed with the statement – some rhetoric contained within the letters contradicted this stance.Footnote131 Several letters highlighted how many Australian women were ‘critical of girls and young women who invite trouble by accepting lifts from strangers, or who go hitch-hiking’. A Sydney woman within the 35 to 44 age group stated that a ‘majority of girls’ are culpable for their assaults for their revealing dress and actions such as ‘accepting lifts from strangers’.Footnote132 A reader from Alice Springs in the same age group blamed rape on ‘pornographic literature’ and staff from rape crisis centres who are ‘avowed man-haters and lesbians who encourage alienation from the male sex’.Footnote133 Moreover, The Weekly included several letters which asserted disbelief in marital rape. A reader from Melbourne stated that she ‘cannot see how a husband could rape his wife’ as ‘sex is a part of marriage’.Footnote134 If The Weekly was a feminist publication, it may have challenged such statements but instead omitted any criticism only pointed out contradictions: ‘Do women who get raped ask for it? That question drew a massive “no” response from the survey, with only five percent of the sample agreeing … Though this was a forceful response, it is clear from many of your letters that women are generally critical of girls and young women who invite trouble by accepting lifts from strangers, or who go hitch-hiking’.Footnote135

In October 1980 The Weekly published an anonymous letter entitled ‘rape in marriage can be devastating’. The writer stated that she was ‘perplexed’ by some readers’ dispute of marital rape, asserting a woman is not the ‘property’ of her husband ‘to be used as he sees fit’.Footnote136 She appealed to The Weekly’s readership’s new understanding of rape as a traumatic experience to explain from her personal experience that rape is as ‘emotionally devastating’ when it takes place in a marriage as it is outside of it.Footnote137 The reader explained how she healed from the ‘emotional scars’ following her divorce with the support, ‘patience and understanding’ of her new ‘loving husband’.Footnote138

The Weekly’s coverage of rape from 1977 positioned its readers to understand rape as a traumatic experience. This narrative was constructed primarily through reporting on political developments and feature articles based on readership contributions from the Voice of the Australian women survey. It revealed how feminist views of rape had infiltrated mainstream Australian women’s attitudes towards sexual violence.

Conclusion

My examination of how The Weekly navigated the issue of rape reveals new insights into Australian women’s attitudes towards sexual assault. It demonstrates how Australian women’s understanding of sexual violence evolved under emerging feminist critique and political debates. The issue of rape and sexual violence emerged and evolved within The Weekly’s reporting throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, a period of significant legal and sociocultural change regarding crimes of sexual offending in Australia. The Weekly’s coverage of rape in the early to mid-1970s had been minimal and tended to sit alongside other issues such as abortion. Buttrose’s appointment as editor of The Weekly was essential to The Weekly’s increasing coverage of rape, which both reflected and shaped mainstream Australian women’s evolving attitudes towards sexual violence. By using a non-feminist lens to frame its rape coverage The Weekly conveyed Australian women’s evolving attitudes towards sexual violence and positioned its conservative readers to perceive sexual violence as a key concern for ordinary Australian women, and one that was detached from the Women’s Liberation Movement.Footnote139

The magazine’s coverage of rape was largely framed in relation to shifting developments within Australian law. Spurred by political developments, The Weekly, platformed critiques of the current judicial and policing systems to emphasise the need for rape law reform. Thus, The Weekly’s coverage revealed how feminist understandings of sexual violence had become incorporated into mainstream discourse about legal and political debates.

Finally, The Weekly positioned its readers to understand rape as a traumatic experience. This narrative was constructed primarily through reporting on political developments and feature articles based on readership contributions. The Weekly did not regard its coverage as an intentional commitment to second-wave feminism but it did reveal how the feminist view of rape as a traumatic experience had moved into mainstream Australian understandings of sexual violence.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my supervisors Dr Jessica Lake and Professor Susan Broomhall for their support in the development of this work. I am thankful for Kate Fullagar and Karen Downing’s guidance and editorial suggestions throughout the submission process. I would also like to thank the peer reviewers for their expertise and valuable feedback on this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of intertest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zara Saunders

Zara Saunders is a PhD Candidate at Australian Catholic University. Her doctoral research examines Australian media representations of sexual assault against women and teenage girls from a historiographical lens.

Notes

1 Anonymous, ‘The Legacy of Anguish and Broken Marriages: Women Talk About the Trauma of Rape’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 23 July 1980, 33, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article51588272.

2 Ita Buttrose, A Passionate Life (Ringwood: Viking, 1998), 81.

3 Ibid., 82.

4 Anonymous, ‘The Legacy of Anguish’, 31, 33.

5 Susan Sheridan, ed., Who Was That Woman: The Australian Women’s Weekly in the Post-War (New South Wales: UNSW Press, 2002), 1, 33.

6 Kate Borrett, ‘Satisfaction Guaranteed! Female Sexuality and Desire in The Weekly, 1961–71’, in Who Was That Woman: The Australian Women’s Weekly in the Post-War, ed. Susan Sheridan (New South Wales: UNSW Press, 2002), 105.

7 Denis O’Brien, The Weekly: A Lively and Nostalgic Celebration of Australia Through 50 Years of its Most Popular Magazine (Ringwood: Penguin Books Australia, 1982), 153–54.

8 Lisa Featherstone, Sexual Violence in Australia, 1970s–1980s: Rape and Child Sexual Abuse (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021), 20.

9 Leah Nichol, ‘The Royal Commission on Human Relationships and the Australian Women’s Weekly, 1977–1980: The Personal, the Political, the Popular’, Australian Feminist Studies 37, no. 111 (2022): 72, https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.2022.2130170.

10 Buttrose, A Passionate Life, 70–72, 81.

11 Adrian Bingham, ‘Reading Newspapers: Cultural Histories of the Popular Press in Modern Britain’, History Compass 10, no. 2 (2012): 142, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-0542.2011.00828.x.

12 Featherstone, Sexual Violence in Australia, 7.

13 Buttrose, A Passionate Life, 71.

14 Megan Le Masurier, ‘Fair Go: Cleo Magazine as Popular Feminism in 1970s Australia’ (PhD thesis, University of Sydney, 2007), 53, http://hdl.handle.net/2123/7777.

15 Michelle Arrow, The Seventies: The Personal, the Political and the Making of Modern Australia (Sydney: New South Publishing, 2019), 5.

16 Arrow, The Seventies, 70.

17 Ibid., 71–72.

18 Ibid., 72; Featherstone, Sexual Violence in Australia, 83–84.

19 Featherstone, Sexual Violence in Australia, 75–78.

20 Ibid., 13.

21 Jackie MacMillan, Freada Klein, Mary Ann Largen, Debbie Friedman, Sue Lenaerts, and Linda Kupis, ‘F.A.A.R. Editorial’, Feminist Alliance Against Rape Newsletter, 1 September 1974, 1, https://jstor.org/stable/community.28036267.

22 Susan Brownmiller, Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape (New York: Fawcett Book, 1975), 15. Note that this argument has received valid criticism for its treatment of race: Angela Y. Davis, Women, Race, Class (New York: Random House, 1981).

23 Featherstone, Sexual Violence in Australia, 66.

24 Ibid.

25 ‘Rape Crisis Centre’, Sydney Women’s Liberation Newsletter, February 1975, 17, cited in Featherstone, Sexual Violence in Australia, 69.

26 The origins of the term rape myth and the concept of rape mythology emerged from feminist thinking and social science scholarship such as criminology during this period. I acknowledge the tension of this concept historically as these myths hold varied meanings across different sociocultural contexts. I engage with the concept of rape mythology through the context in relation to Australian (predominately white) women from the 1970s and 80s.

27 Julia Schwendinger and Herman Schwendinger, ‘Rape Myths: In Legal, Theoretical, and Everyday Practice’, Crime and Social Justice 1 (1974): 20–21, http://www.jstor.org/stable/29765884.

28 John Noble, ‘Women as the Victims of Crime’ (Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology, 1975), 6, https://doi.org/10.52922/tpr37702.

29 Featherstone, Sexual Violence in Australia, 142.

30 Jocelynne Scutt, ‘Consent in Rape: The Problem of the Marriage Contract’, Monash University Law Review 3, no. 4 (1977): 287.

31 Lisa Featherstone, ‘‘‘That’s What Being a Woman Is For’’: Opposition to Marital Rape Law Reform in Late Twentieth-Century Australia’, Gender & History 29, no. 1 (2017): 90, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0424.12281; Peter Sallmann and Duncan Chappell, Rape Law Reform: A Study of the South Australian Experience (Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology, 1982), 11, https://www.aic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-10/CRG-11-77-FinalReport_0.pdf.

32 Peter Sallmann, ‘Rape in Marriage’, Legal Service Bulletin 2, no. 6 (1977): 202.

33 Sallmann, ‘Rape in Marriage’, 203.

34 Ibid., 204.

35 Ibid.

36 Arrow, The Seventies, 141.

37 Ibid., 143.

38 Royal Commission on Human Relationships, Final Report vol. 5 (Canberra: Government Printer, 1977), 159.

39 Ibid., 161.

40 Ibid., 161, 169.

41 Ibid., 206, 234.

42 Ibid., 178.

43 Ibid., 205.

44 Featherstone, ‘That’s What Being a Woman is For’, 87; Featherstone, Sexual Violence in Australia, 143; Michael D.A. Freeman, “‘But If You Can’t Rape Your Wife, Who[m] Can You Rape?”: The Marital Rape Exemption Re-Examined’, Family Law Quarterly 15, no. 1 (1981): 27, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25739275.

45 Chelsea Barnett, ‘Male Chauvinists and Ranting Libbers: Representations of Single Men in 1970s Australia’, in Everyday Revolutions: Gender, Sexuality and Society in 1970s Australia, ed. Michelle Arrow and Angela Woollacott (Canberra: ANU Press, 2019), 296.

46 Buttrose, A Passionate Life, 65–68.

47 Valerie Lawson, ‘Fenston, Esmé (Ezzie) (1908–1972)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography (ADB), National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, accessed online 20 July 2023, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/fenston-esme-ezzie-10165/text17957.

48 Lawson, ‘Fenston, Esmé’.

49 Jeannine Baker, ‘Drain, Dorothy Simpson (Dot) (1909–1996)’, ADB, accessed online 20 July 2023, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/drain-dorothy-simpson-dot-25991/text34066.

50 Baker, ‘Drain, Dorothy Simpson’; O’Brien, The Weekly, 146.

51 Buttrose, A Passionate Life, 68–69.

52 Ibid., 69–70.

53 Ibid., 75.

54 Sheridan, Who Was That Woman, 143.

55 Buttrose, A Passionate Life, 72.

56 Megan Le Masurier, ‘Desiring the (Popular Feminist) Reader: Letters to Cleo during the Second Wave’, Media International Australia 131, no. 1 (2009): 107, https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X0913100112.

57 Le Masurier, ‘Desiring the (Popular Feminist) Reader’, 108.

58 Ibid., 110–15.

59 Buttrose, A Passionate Life, 70–72, 81.

60 Ibid., 71.

61 O’Brien, The Weekly, 152.

62 Ibid.

63 Buttrose, A Passionate Life, 90–96.

64 Anonymous, ‘Three Contentious Issues’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 21 November 1973, 7, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article47228787.

65 Anonymous, ‘Entertaining and How the Place Should Look to Him’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 9 June 1971, 15, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article44799808.

66 B. Rennie, ‘Letterbox: Jury Service’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 5 December 1973, 55.

67 Rennie, ‘Letterbox: Jury Service’, 55; O. Woolcock, ‘Letterbox: Women on Juries’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 7 November 1973, 63, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article52260921.

68 Andrew Choo and Jill Hunter, ‘Gender Discrimination and Juries in the 20th Century: Judging Women Judging Men’, International Journal of Evidence & Proof 22, no. 3 (2018): 212, https://doi.org/10.1177/1365712718782990.

69 Anonymous, ‘For the Public Benefit: Have You Seen This Man?’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 10 September 1975, 7, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article55190318.

70 Ita Buttrose, ‘At My Desk’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 10 September 1975, 1, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article55190324.

71 Ibid.

72 Anonymous, ‘For the Public Benefit’, 7.

73 Ibid.

74 E. Clare Wilkinson, ‘“‘Real Rape” and the Coverage of Sexual Violence in Dutch Newspapers, 1880 to 1930’, Women’s History Review 31, no. 7 (2022): 1190, https://doi.org/10.1080/09612025.2022.2088086.

75 Anonymous, ‘The Legacy of Anguish’, 30.

76 Barbara Bishop and Kerry Petersen, ‘What Australian Women Should Know About Marriage’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 10 May 1978, 16, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article51777867.

77 Ibid., 19.

78 Ibid., 16.

79 Ibid., 19.

80 Sandra Moore, ‘How to Defend Yourself and Your Home’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 12 August 1981, 32, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article58151500.

81 Ibid.

82 Ibid., 33; Wilkinson, ‘“Real Rape”’, 1190.

83 Daphne Guinness, ‘The Question of Rape: A Queensland MP Calls for Action’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 13 July 1977, 2–3, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article55477120.

84 Ibid., 2.

85 Ibid.

86 Ibid., 3.

87 Ibid.

88 Robin Oliver, ‘Sweeping Changes to Rape Legislation Proposed’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 13 August 1980, 13, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article44795608.

89 Ibid, 13.

90 Ibid.

91 Freeman, ‘But If You Can’t Rape Your Wife, Who[m] Can You Rape’, 27.

92 Bishop and Petersen, ‘What Australian Women Should Know About Marriage’, 16.

93 Hazel Jamieson, ‘Letterbox: Needless Risks’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 10 August 1977, 65, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article47229957.

94 Jamieson, ‘Letterbox: Needless Risks’, 65.

95 Ibid.

96 ‘Rape Crisis Centre’, Sydney Women’s Liberation Newsletter, February 1975, 17 cited in Featherstone, Sexual Violence in Australia, 69.

97 Jamieson, ‘Letterbox: Needless Risks’, 65.

98 Featherstone, Sexual Violence in Australia, 26, 76–78.

99 Jenny Irvine, ‘Women Who Care About What is Going On’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 5 April 1978, 4, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article57644267.

100 Irvine, ‘Women Who Care About What is Going On’, 5.

101 Buttrose A Passionate Life, 81.

102 Irvine, ‘Women Who Care About What is Going On’, 5.

103 Ibid.

104 Rose Munday, ‘Rape: The Victim’s Ordeal’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 3 May 1978, 16, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article51779009.

105 Featherstone, Sexual Violence in Australia, 63; Munday, ‘Rape: The Victim’s Ordeal’, 16.

106 Munday, ‘Rape: The Victim’s Ordeal’, 16.

107 Ibid., 17.

108 Ibid.

109 Ibid., 19.

110 Michelle Arrow and Angela Woollacott, ‘Revolutionising the Everyday: The Transformative Impact of the Sexual and Feminist Movements on Australian Society and Culture’, in Everyday Revolutions: Gender, Sexuality and Society in 1970s Australia, ed. Michelle Arrow and Angela Woollacott (Canberra: ANU Press, 2019), 3, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvq4c17c.4; Robinson, ‘Eggs, O’Wheels, Hexagons, Repairs’, 116.

111 Featherstone, Sexual Violence in Australia, 63.

112 Buttrose A Passionate Life, 81; O’Brien, The Weekly, 153.

113 Anonymous, ‘The Voice of the Australian Woman’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 13 February 1980, 10–30, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article44553998.

114 Anonymous, ‘The Voice of the Australian Woman’, 10–30.

115 O’Brien, The Weekly, 153.

116 Ibid.

117 Ibid.

118 Sheridan, Who Was That Woman, 153.

119 Anonymous, ‘Incest: The Hidden Crime You Wanted Brought into the Open’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 30 April 1980, 16–17, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article51585320.

120 Ibid., 19.

121 Ibid., 20–21.

122 Ibid., 20–21, 24–25.

123 Ibid., 24.

124 Ibid., 19.

125 Anonymous, ‘The Legacy of Anguish’, 30.

126 Ibid., 31.

127 Ibid., 35.

128 Ibid., 31.

129 Ibid., 33.

130 Ibid.

131 Ibid., 30.

132 Ibid.

133 Ibid., 30–31.

134 Ibid., 35.

135 Ibid., 30.

136 Anonymous, ‘Between Ourselves: Rape in Marriage Can Be Devastating’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 1 October 1980, 57, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article57568679.

137 Anonymous, ‘Between Ourselves: Rape in Marriage’, 57.

138 Ibid.

139 Buttrose, A Passionate Life, 70–72, 81.