ABSTRACT

The past two decades have witnessed unprecedented policy effort to improve access to medical services and strengthen financial protection from catastrophic healthcare expenditure. Despite billions of dollars in health spending, many – especially across the developing world – continue to remain vulnerable to financial impoverishment. What accounts for this poor performance? To respond to this question, we turn to the design literature in public policy, which emphasises the role of policy tools or combination of tools in addressing a social problem. In this paper, we focus on two inter-related aspects of the design orientation to explain outcomes: a) the appropriateness of the policy tool and b) the capacity of government agencies. We apply a framework, which integrates vital questions on both these aspects along three common dimensions (analytical, operational and political) to assess healthcare reforms in India and Thailand. The case studies illustrate the importance of both these aspects of the design orientation in explaining outcomes, and show how they are commonly overlooked in the health and social policy literatures, and in reforms underway.

Introduction

Over the past decade many developing economies have introduced reforms that aim to improve access to medical services and increase financial protection from catastrophic health care expenditure (Bales, Citation2018; Bonilla-Chacin and Aquilera, Citation2013; Coelho & Shankland, Citation2011; Hanvoravongchai, Citation2013; Marten et al., Citation2014; Somanathan, Dao, & Tien, Citation2013) Universal health care has emerged as an overarching social policy goal, and is central to the development agenda in most emerging economies (Mills, Citation2014; Vega, Citation2013; McKee, Balabanova, Basu, Ricciardi, & Stuckler, Citation2013; Levy and Schady, Citation2013). While many economies have made important strides towards universal health coverage, many continue to remain – especially across the developing world – with inadequate access and financial protection when they fall ill (Mills, Citation2014; Bredenkemp et al., Citation2015). What accounts for this poor performance?

The health policy literature attributes this to limited expenditure on health, limited investments in public health, a large informal sector which is difficult to cover, and infrastructure and other ‘supply-side’ constraints (Mills, Citation2014; Bredenkemp et al., Citation2015; Hsiao and Shaw, Citation2007; Knaul & Frenk, Citation2005; ; Harimurti, Pambudi, Pigazzini, & Tandon, Citation2013; La Forgia & Nagpal, Citation2012). In this paper, we offer an alternate set of propositions that focus on the design of the health system, specifically exploring how universal coverage reforms affect dominant policy instruments used to finance healthcare.

Contemporary universal healthcare reforms typically contain two broad elements. The first are a series of reforms that essentially change how individuals pay for, and access healthcare services. Most countries that have implemented these reforms have introduced changes that affect how health-financing instruments are calibrated. This usually entails changes in benefit levels, or contribution rates and eligibility conditions (e.g. India, Vietnam, Philippines, Singapore, China, and Indonesia). The second broad set of reforms focus on how healthcare providers are paid for their services. This typically include introducing new provider payment instruments (e.g. Diagnostic related groups -DRGs- Capitation payments, etc.), or layering existing instruments with new mechanisms that affect change (e.g. China, Indonesia, Thailand). These broad elements of universal coverage reforms, and the extent to which they affect change, are summarised in .

Table 1. Core elements of universal coverage reforms.

In this paper, we advance two inter-related propositions. The first is that in many developing countries, the dominant instrument used to finance the health system (e.g. social insurance, voluntary insurance, mandatory savings, etc.) is often ill-suited to address the very problem it seeks to solve. This is aggravated when increased government spending is accompanied by parametric changes to benefit levels or the number of beneficiaries rather than the instrument in the first instance. The second is contemporary provider payment reforms entail not only designing and calibrating sophisticated instruments such as risk-adjusted capitation payments or DRGs that require advanced analytical abilities, but also a range of operational and political skills that reform efforts underway do not adequately recognise. Our analysis is a sobering lesson in caution on the perils of increased public expenditure in health systems that do not use appropriate policy instruments, and where limited policy capacities encumber the effectiveness of instruments.

In developing this line of reasoning, we rely on the ‘new’ design orientation, which emphasises how specific tools or a combination of tools are used in addressing a problem (Howlett, Mukherjee, & Woo, Citation2015). We draw on a framework on anticipating policy effectiveness developed in this special issue which connects the recent scholarship on policy tools – how they are assembled, sequenced, and deployed in heterodox contexts (Capano & Lippi, Citation2017; Howlett & Mukherjee, Citation2018) – and policy capacity (Howlett & Ramesh, Citation2016; Pierre and Painter, Citation2005; Wu, Ramesh, & Howlett, Citation2015; Bali and Ramesh, Citation2018). The framework is applied to study healthcare reforms in India and Thailand. The central argument we develop is that for universal coverage reforms to be effective, they must emphasise ‘tool appropriateness’, i.e. the extent to which policy tools are able to address a goal in a specific context; and a spectrum of policy capacities in managing these tools.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. The subsequent section summarises the ‘new’ design orientation in policy sciences, and the framework in this paper. This is followed by a summary of the design of health reforms in India and Thailand. The last section discusses the role of policy tools, and critical capacities for effective policy design using the backdrop of health reforms in both countries.

The ‘New’ design orientation

The design orientation in public policy echoes Harold Lasswell’s initial charge that policy sciences, as a field of inquiry, strive to retain three principal attributes: contextuality, problem orientation and [methodological] diversity (Laswell, Citation1971, p. 4). The approach emphasised the primacy of problem solving and the means (i.e. policy tools or instruments) most able to address or potentially address a problem. Michael Howlett and colleagues in a series of papers (Howlett, Citation2014; Howlett & Lejano, Citation2012; Howlett et al., Citation2015) trace the decline in the problem-solving approach and attributed this to the proliferation of market-centred and network governance approaches, which narrowed the spectrum of policy tools available to designers. These approaches largely focused on policy styles of governments and broad institutional arrangements to organise economic and social activity rather than the role of policy tools and instruments in problem solving. In recent years, however, there has been increased interest in policy design, design processes and consequently on policy instruments as the shortcomings of the undiscerning ‘deregulation’-‘marketisation’-‘any-thing-but-government’ approach became apparent (Peters, Citation2018). The ‘new’ design orientation re-emphasises the role of a policy instrument or a series of instruments packaged as a ‘policy-mix’ or a ‘portfolio’ of instruments in addressing specific problems (Howlett et al., Citation2015); and in the underlying capabilities of governments to effectively utilise these instruments (Bali & Ramesh, Citation2018).

Policy tools, mixes, and their attributes

Policy tools or instruments – ‘a set of techniques by which governmental authorities wield power in attempting to support and effect change’ (Vendung et al, Citation1997) have been central to studies of public policy and policy formulation (Hood, Citation2007; Howlett, Ramesh, & Perl, Citation2008). Most of the earlier scholarship focused on developing taxonomies to classify policy tools (see Kirschen, Citation1964; Lowi, Citation1966; Bardach, Citation1980; Hood, Citation1983; Elmore, Citation1978; Schneider & Ingram, Citation1990; Howlett, Citation2011). These taxonomies provided analysts a framework for describing and assessing the ways in which governments connect policy goals and means in their effort to improve outcomes which over time have fostered the emergence of a ‘tools approach’ to understanding problems (Hood, Citation2007).

Recent research has focused not only on choice of individual tools but also how they are assembled together as ‘policy mixes’ or ‘portfolios’ to maximise complementarities amongst and between tools (Borras and Edquist, Citation2013; Flanagan, Uyarra, & Laranja, Citation2011; Howlett & Del Rio, Citation2015; Mohnen and Roller, Citation2005; Schaffrin, Sewerin, & Seubert, Citation2014; Sovacool, Citation2008); issues relating to policy coordination (Jordan & Lenschow, Citation2010; Peters, Citation2015, Citation2018); policy coherence and consistency of these mixes (Howlett & Rayner, Citation2007; Kivimaa and Virkamaki, Citation2014; Rogge & Reichardt, Citation2016); how they are sequenced and layered (Howlett, Citation2019); the ‘intensity’, and explicitness with which they affect change (Thomann, Citation2018; Howlett, Citation2018) and criteria to evaluate them (Howlett, Capano, & Ramesh, Citation2018; Capano & Woo, Citation2018; Mukherjee & Howlett, Citation2018; del Rio, Citation2018; Bali, Capano and Ramesh, Forthcoming). These studies go beyond describing broad institutional choices used to organise a sector or policy styles and implementation preferences of governments (Bemelmans-Videc, Citation1998; Hood, Citation1983; Linder & Peters, Citation1989; Salamon, Citation2002; Trebilcock et al., Citation1982).

Some studies have tried to explain stability and change in policy-mixes. Using broad contours of arguments developed by Howlett and Cashore (Citation2009) – see – change in policy-mixes is explained through the processes of replacement, drift, conversion, and layering (Carey, Kay, & Nevile, Citation2017; Howlett & Rayner, Citation2007, Citation2013; Kern & Howlett, Citation2009; Kern, Kivimaa, & Martiskainen, Citation2017) These processes result in policy packaging, when instruments are discarded, and new instruments are introduced; or in policy patching and stretching which involves restructuring existing policy tools rather than proposing completely new, alternative arrangements (Feindt & Flynn, Citation2009; Howlett & Mukherjee, Citation2018).

The proliferation of research on policy tools and mixes has however not adequately emphasised the, ex-ante, feasibility of the tool to address the problem. The literature emphasises contextual factors (Howlett & Ramesh, Citation1993); Five I’s – ideas, interests, individuals, institutions and international environment (Peters, Citation2002); constituencies, which socialise their use (Beland & Howlett, Citation2016; Jenkins, Citation2014); and subjective perceptions on the political trade-offs in explaining instrument choices. Even the popular schema developed by Christopher Hood (Citation1983, Citation2007) which groups tools into four functional categories: Nodality, Authority, Treasure and Organisation; and Howlett’s (Citation2011) distinction between procedural and substantive tools does not focus on the feasibility of the tool. Similarly, scholars that emphasise attributes such as ‘goodness of fit’ in policy mixes or the need for policy instruments to be compatible with larger ‘political context’ and reflect ‘common patterns of governance arrangements… … order for these designs to be considered feasible’ (Howlett, Mukherjee, & Rayner, Citation2014, p. 5) refer to the coherence of instruments with policy styles but not with the problem at hand.

Policy capacities: a spectrum of skill-sets and abilities

Policy capacity is widely used in the literature to describe a composite set of resources available to governments and their use of these resources in policy-making. For instance, Painter and Pierre (Citation2005) define it as ‘‘. . the ability to marshal the necessary resources to make intelligent collective choices, in particular to set strategic directions, for the allocation of scarce resources to public ends”; Howlett and Lindquist (Citation2004) as “scanning the environment and setting strategic directions”; and Parsons (Citation2004) as ‘weaving’ interests of stakeholders and knowledge in to a coherent policy. Wu et al. (Citation2015), building on Moore (Citation1995), outline key skills or competences which comprise policy capacity across three different dimensions analytical, operational and political. Each of these three competencies involves capabilities at three different levels – individual, organisational and systemic – generating nine basic types of policy-relevant capacity. Analytical capacities help to ensure policy actions are technically sound. Operational-level capacity focus on resources that enable policy actions so that they can be implemented in practice. Political capacity helps to obtain and sustain political support for policy actions Gleeson, Legge, O’Neill, & Pfeffer, Citation2011; Rotberg, Citation2014; Tiernan & Wanna, Citation2006).

Analytical framework

We rely on the anticipating policy effectiveness framework developed in this special issue (see Bali, Capano and Ramesh, CitationForthcoming). The framework brings together the above discussion on tools and capacity, and attributes central importance to problem solving and abstracts away from issues relating modes of governance used and/or formulation styles of governments. It focusses on the potential of a tool to solve the problem in a given context, the extent to which it can be operationally deployed, and is politically acceptable; and on the capacity of the implementing agency to be able to use the tool to its potential (). The implicit assumption is that variations in design effectiveness can be explained by studying tool choices and the capacities of government agencies.

Table 2. Dimensions of Policy Effectiveness.

Empirical strategy

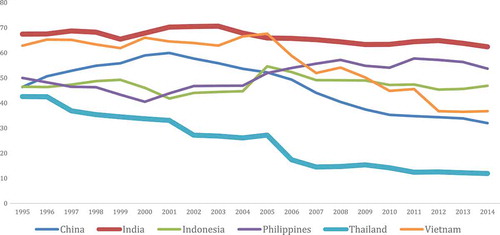

The fundamental goals of any health system, and the primary focus of universal coverage reforms, relate to access to medical services and protection from financial impoverishment when people fall ill (Roberts, Hsiao, Berman, & Reich, Citation2004). In most modern societies, access to medical services is constrained by an individual’s ability to pay. At the same time, expecting individuals to pay for their healthcare expenditure entirely is not only socially and politically unacceptable but economically inefficient due to the uncertainty of falling ill, and its associated costs (Blomqvist, Citation2011). This is why most health systems pool the risks of falling ill across the society through private or social insurance or other such mechanisms to reduce, if not eliminate, out-of-pocket (OOP) spending (by patients) on healthcare. OOP spending on healthcare serves as a proxy for measuring performance on the two contradictory goals of health systems: maintaining affordability while minimising moral hazard (Bali & Ramesh, Citation2015a). An optimal OOP spending is a trade-off between preventing financial impoverishment and the economic inefficiencies caused by moral hazard (Blomqvist, Citation1997). The share of healthcare expenditure over the past two decades across major economies in developing Asia are plotted in . This paper focuses on cases at either extremes of OOP spending: India and Thailand. While OOP spending continues to account for an overwhelming share of total health expenditure in India, Thailand's health policy reforms have been successful in not only improving access, but lowering OOP spending on healthcare since 2002.

India

India’s earliest health policy document – The Bhore Committee Report published in 1946 – envisioned a largely publicly financed system with primary care delivered through a network of sub-centres and primary healthcare centres; secondary care through community healthcare centres; and advanced treatment at specialist hospitals in large cities across India (Bhore Citation1946). Seven decades since, this vision has not been realised (Bali & Ramesh, Citation2015b). Most healthcare in India is paid for privately, with limited risk-pooling, through OOP payments (), and delivered at privately owned hospitals (Gupta and Chowdhury, Citation2014; Rao and Choudhury, Citation2012). India's performance on conventional health indicators such as life expectancy, infant and child mortality rates, until very recently, has been unequivocally poor (Bali & Ramesh, Citation2015a; Rao Citation2015). Its health system has relied on four broad health-financing instruments to organise health services to its civilian population. Programs for civil servants and military personnel cover a small share of the population and are therefore not discussed here.

First, a large network of publicly-financed and publicly-owned hospitals and health centres which provide, in principle, free services across urban and rural India. However, starved of funds and with limited accountability, these centres and hospitals are poorly run, suffer from chronic absenteeism, often out of essential medical supplies and equipment (Radwan, Citation2005). A Government of India Report on Health Statistics in 2012 estimated that the shortfall in healthcare infrastructure was nearly 25 and 40% at rural health centres; and that over 40% of the available positions for specialist doctors at community health centres were lying vacant due to shortage of applicants willing to work in rural areas and in small towns (Government of India, Citation2012).

Second, a mandatory social insurance program – The Employees State Insurance Scheme (ESIS) – has existed since 1948 to provide care for those in the formal private sector. The program covers less than 5 percent of India’s population and ESIS hospitals are heavily under-utilised, reflected in average bed occupancy ratio of 51% in 2016. A major challenge the ESIS faces is technical in nature – it is designed to cover only those who work in the formal sector in an economy overwhelmingly characterised by informal employment (Bali, Citation2016). The Employees State Insurance Corporation (ESIC) which administers the ESIS does not perform many critical agency functions such as fund management, strategic purchasing of services, etc. (Bali, Citation2016; Ross, Citation2011).

Third, many state governments offer insurance-based programs that provide basic health services at designated public or private hospitals. While the institutional arrangements that underpin these programs vary, they are essentially non-contributory programs and target households below the poverty line. While these programs have played an important role in extending coverage to vulnerable groups, they cover a relatively small population. A major improvement occurred in 2008 with the launch of the Rashtariya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY). It is a non-contributory scheme for poor households to cover the costs of in-patient treatment (subject to limits) at designated hospitals, who are paid at negotiated prices. The program has faced numerous challenges related to inadequate coverage, weak management, variable quality, and so on (Karan, Yip, & Mahal, Citation2017; Maurya & Ramesh, Citation2018). In 2017, the central government announced a new program, The National Health Protection Scheme, which provides benefits up to USD 7,000 per year, per family. While, limited information on its design is available at this stage, it is largely similar to the RSBY, except for higher benefit levels and less stringent eligibility criteria.

The fourth broad instrument is voluntary health insurance, which play a small role, accounting for less than 5% of total health spending. Until the late 1990s, the insurance market was dominated by two government-owned companies – the Life Insurance Corporation and the General Insurance Corporation – which had limited incentives to offer innovative products or expand membership. While there has been a proliferation of private insurers in recent years, about 75% of the 400 million insured individuals are enrolled in government-administered programs such as the RSBY, and about another 15% are enrolled in employer-sponsored programs. The major challenge with these schemes is that they offer small benefits levels and often exclude pre-existing illnesses.

Thailand

Thailand is widely admired for achieving universal healthcare coverage at relatively low levels of spending following reforms adopted in 2002. Until then, there existed numerous schemes that together covered about two-thirds of the population. There are currently three broad sets of health financing arrangements in Thailand.

The first is Social Health Insurance (SHI), which is a typical insurance scheme for formal sector employees and their dependents. The SHI contracts services with public and private hospitals, and reimburses them on a capitation basis for outpatient care based on the number of registered members. These capitation payments are not risk-adjusted, but chronic and high-cost diseases are paid for using a risk-adjusted payment per beneficiary. Fee for service (FFS) reimbursements are used for specific services for outpatient and inpatient care. Given that most formal sector employees are concentrated in metropolitan areas SHI contracted hospitals do face market competition in having to retain their members. The program covers about 10 percent of the population.

The second broad program is the publicly financed Civil Services Medical Benefit Scheme (CSMBS) which covers civil servants, and their dependents. It is a generous scheme for both the beneficiaries, who face few restrictions, and providers, who are paid on an FFS basis. The program is governed by the Comptroller’s office which has limited capacity to monitor and supervise medical services. Understandably, the scheme is believed to suffer from over-billing and over utilisation (World Health Organization, Citation2015; Hanvoravongchai, Citation2013; Tangcharoensathien et al 2014). To rein in the costs, in 2007 the scheme was reformed to cover only hospitalisation in public hospitals, and only ambulatory care would continue to be paid on FFS-basis. Inpatient care is reimbursed on DRG basis, though no global budgets – a critical pre-requisite for DRGS to be effective – are applied. The CSMBS covers about a tenth of the population, and is the most expensive public healthcare scheme (per capita) in Thailand.

The third is the tax-financed Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS) which is administered by the National Health Security Office (NHSO). The UCS is a non-contributory tax-financed scheme. Under the scheme, patients receive primary care at registered clinics and advanced care through a referral system in tertiary hospitals. Most healthcare services are delivered at public hospitals, which account for an overwhelming share of total hospital beds in Thailand. Primary care providers are reimbursed on a capitation basis, which is adjusted for age and gender and revised annually. A single capitation rate is applied throughout the country for both public and private providers. The capitation is paid to a contractor network, which allocates capitation payments to primary centres and smaller hospitals within a network based on their utilisation rates.

Secondary care under UCS was initially reimbursed on the basis of a national global budget, but a regional global budget is currently employed. This is estimated based on an expected utilisation rate and unit cost per admission at different levels of hospitals. Subsequently DRGs with accompanying relative weights are assigned to each treatment – and the reimbursement rate for each weight is obtained by dividing the global budget by aggregated relative weights (Tangcharoensathien et al., Citation2014). This ensures that a fixed budget constrain is in place, when distributing amounts to respective hospitals. High-cost cases or selected diseases are subject to a pre-assigned fee schedule, which are reviewed periodically (Hanvoravongchai, Citation2013).

Discussion

In India, the dominant instruments used to finance the healthcare system are social insurance, and a network of publicly-funded hospitals and health centres. Both are, however, dwarfed by private out of pocket payments and private healthcare providers. There are several pre-requisites and a range of critical governance functions that need to be completed for such an arrangement to work – most of these conditions are missing.

For publicly organised health insurance to work effectively, it is necessary to ensure a large insurance pool with broad coverage of population segments of different age and health status so that high risks are offset by low risks. It also requires formal and functioning labour markets, investment and fund management, so that contributions can be collected and managed on a regular basis (Bali, Citation2016; Ross, Citation2011), and a range of purchasing or contracting functions on behalf of members (Tangcharoensathien et al., 2014; Preker & Langenbrunner, Citation2005; Preker, Liu, Velenyi, & Baris, Citation2007). Very few of these conditions exist in India. RSBY covers the poor, mostly rural population, who are hard to reach and serve. Moreover, labour markets in India are overwhelmingly informal (Srinivasan, Citation2011), which explains the relatively small membership in the ESIS which raises management costs.

RSBY and especially ESIC are hobbled by management inefficiencies as well (Maurya & Ramesh, Citation2018). The latter fails to complete many of the core agency functions – including staffing and maintenance, not to mention strategic purchasing, and contract negotiations and management. The program’s bloated administrative apparatus account for about a tenth of revenues (Employees State Insurance Corporation [ESIC], Citation2017), which is very high compared to other social security organisations in developing Asia (see Asher & Bali, Citation2015). Its inefficiency is evident in the average bed occupancy ratio of 50 percent in ESIS hospitals, despite a massive overall under-supply of beds in the country (ESIC, Citation2017). The program is however, politically popular, especially with trade unions because the premiums are paid by employers. Moreover, the ESIC is governed by the Ministry of Labour rather than the Ministry of Health which pleases labour but aggravates problems of policy coordination (Bali & Asher, Citation2012).

The second dominant instrument, a network of publicly funded hospitals and health centres across India have a poor record, unlike such hospitals in other countries (e.g. Canada, Cuba, U.K, Hong Kong) where they have been bulwarks of efficiency. The challenge in India stems from the operational and political dimensions: hospitals are administered by State governments, many of which suffer from weak fiscal and administrative capacities (Bali & Ramesh, Citation2015b). This is aggravated by, until recently, central government’s own very limited leverage to intervene in service delivery or regulate standards of care due to its peripheral role in financing and provision of health care in the country. There are also lapses in governance arrangements. Health agencies in both state and central governments are staffed by non-specialists and career bureaucrats that are rotated across different agencies every few years which denies them opportunity to develop domain expertise. Hospital superintendents have limited autonomy and discretion in important administrative and personnel decisions (Bali & Ramesh, Citation2015b). At a political level, successive governments have been unable to divert more resources to these cash strapped hospitals (La Forgia & Nagpal, Citation2012). Surprisingly, the extremely poor quality of care provided in these hospitals has not been a significant issue in Indian elections.

Government-sponsored insurance-based programs are politically popular and have proliferated at the state level, including Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh. Moreover, neither the insurance companies nor State governments that pay for the program have the capacity to monitor these claims, and ensure that hospitals did not charge patients extra payments (Maurya & Ramesh, Citation2018). Recently, the central government has been increasing benefits, enrolling beneficiaries, and contracting with hospitals at an expedited rate in the face of looming elections. However, there are limited accountability mechanisms to monitor and moderate the ‘physician agency’ that is commonly associated with healthcare markets (Bali & Ramesh, Citation2015a).

Thailand’s experience with the earlier programs (the social insurance and civil service scheme) and their limited success in achieving universal coverage were instructive in shaping the design for the universal coverage scheme (Tangcharoensathien, Suphanchaimat, Thammatacharee, & Patcharanarumol, Citation2012). For instance, the tax-funded scheme for the civil servants (CSMBS) was found to be prohibitively expensive to be extended universally. Moreover, The Comptroller’s office, which supervised the program did not have the capacity to monitor reimbursement claims and lacked mechanisms to make changes (Hanvoravongchai, Citation2013; World Health Organization, Citation2015). The government was also unable to overcome the entrenched interests of the civil servants, and healthcare providers that benefited from the generous and expensive program. Changes to the CSMBS were only introduced after extensive lobbying by the the Ministry of Public Health, the NHSO and the Ministry of Finance and benchmarking costs of the three programs (Tangcharoensathien et al., Citation2014). However, they were unable to impose a global budget which would have imposed a hard budget constraint on the CSMBS.

Similar to India, the Social Health Insurance program (SHI) was unable to cover non-formal sector population, did not carry out many of the agency functions (e.g. investment management), and was expensive to administer (Bali, Citation2016). However, it was able to make changes in how it negotiates contracts with hospitals. It was also able to change capitation rates to account for treating expensive or high-cost diseases.

The UCS – a non-contributory and tax-financed program – meets all the criteria of an appropriate policy instrument. It is not only tax-funding the most appropriate instrument to organise healthcare in a large informal economy, but also it was operationally feasible as most hospitals where owned by the government itself. No less significantly, it was politically popular. The Thai Rak Thai party championed the program and made it the mainstay of its 2001 election campaign and went on to win the election.

UCS is governed by the NHSO which is staffed by internationally trained health economists and health policy scholars. Between the 1998–2008, 36 staff have received advanced post-graduate training (PhDs, MS degrees) in health economics and policy, and have returned to various agencies in Thailand’s public health ecosystem (Pitayarangsarit & Tangcharoensathien, Citation2009). These technical skills have helped calibrate and fine-tune risk and age-based adjustments to capitation rates, designing the DRG system and its accompanying weights, conducting utilisation reviews, etc. Reliance on costs information and benchmarking of performance provided evidence for fine-tuning the scheme. For example, in the face of hospitals’ complaints that capitation rates were too low, the NHSO was able to analyse the data presented by hospitals and calibrate rates accordingly. The ability to introspect and learn from the strengths and weaknesses of previous programs is central to efficient management of the UCS (Tangcharoensathien et al., Citation2012).

The NHSO has demonstrated a spectrum of operational skills in its coordination efforts across multiple hospital networks and government agencies, including the Ministry of Public Health (its parent agency), the Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Labour. Its skills in managing relationships with stakeholders allowed it to promote coherence among different goals: promote access to health care while minimising expenditures. For example, the NHSO introduced a national formulary for prescription drugs so the UCS could access pharmaceuticals at lower costs. It established accountability mechanisms, and quality and standardisation protocols for public hospitals (Bali, Citation2016).

The NHSO has demonstrated political acumen too in negotiating with hospitals and program costs with the Ministry of Public Health. However, the initial policy vision of an integrated program (which brings together the civil service, social insurance and the UCS) remains unrealised. It was unable to overcome the entrenched interests that benefited from the other two relatively generous programs. However, it was successful in introducing some parametric changes such as the use of DRGs in the civil service program.

Using the analytical framework which emphasises tool appropriateness and policy capacity, two generalisable propositions emerge from the empirical cases in this paper.

Tool appropriateness

The framework conceptualises tool appropriateness along three essential questions. Can the tool substantively solve the problem? Can it be easily deployed? Is it politically acceptable? These three questions recognise that while any design process aims to be instrumentally oriented (i.e. prioritises problem-solving in instrument choice – see Howlett, Citation2019; Peters, Citation2018), it is often driven by political priorities and is a highly contingent process (Chindarkar, Howlett, & Ramesh, Citation2017; Colebatch, Citation2018). Understanding of trade-offs among policy tools choices are not new of course. Nearly three decades ago, Linder and Peters (Citation1991) note that design involves ‘not only the potential for generating new mixtures of conventional solutions, but also the importance of giving careful attention to trade-offs among design criteria when considering instrument choices’. However, the potential of the tool to address the problem it seeks to solve deserves utmost priority. Furthermore, each policy tool has a range of institutional pre-requisites essential for its functioning that must be considered if the tool is to be effective.

This is evident in both case studies. In using social insurance to pool risks, India and Thailand have relied on an instrument that is intrinsically unable to provide healthcare for beyond a relatively small population in formal employment. While social insurance does not address the issue of substantive usefulness in large informal economies, it is operationally feasible and politically popular, especially with labour unions. This explains why social insurance is readily adopted and easily launched without doing much to expand coverage to the vulnerable population that need protection the most. The policy lock-in and consequent path dependency restrict significant changes in the future (Christensen, Laegreid, & Wise, Citation2002). This flexibility is further reduced in large public expenditure programs (such as healthcare), where changes affect the material interests of constituents, elites and political actors. Thus, most reforms result in calibrations () that invariably increase (public) spending, without doing much to address the problem.

While non-contributory, tax-financed healthcare schemes work well in developing countries with large informal employment, the pre-requisites for its effectiveness have been present in Thailand but not India. For instance, ownership and financing of public hospitals in India were not accompanied by appropriate mechanisms to ensure accountability and performance management. Similarly, state insurance schemes do not have mechanisms in place to manage the ‘physician agency’ in healthcare markets (Bali & Ramesh, Citation2015a). In Thailand’s case, on the other hand, these institutional pre-requisites were actively designed and included in the UCS’ design.

The conclusion that emerges from this analysis is that in developing economies the dominant instrument to finance the health system must be pooling of healthcare risks for the entire society. Increased spending on any contributory program, or changes in benefit levels, or eligibility criteria (which is the mainstay of contemporary reforms), as highlighted in , will do little advance the goals of universal health coverage. Unless reforms focus on instrument choice rather than on pubic expenditure, the gap between the ‘intended design’, ‘realised design’, and policy outcomes will continue to widen Peters (Citation2018).

Critical capacities

The notion of capacities in the Framework focuses on the skills and abilities of the implementing agency to utilise a tool to its full potential. Contemporary policy tools are increasingly complex and require a range of technical skills to ensure that the policy addresses the desired attributes (e.g. ‘adaptive’ ‘resilient’, ‘robust’, and ‘agile’ – see Howlett et al., Citation2018). If the policy tool in question requires deep changes in the key stakeholders’ behaviour, then the implementing officials would need political acumen, a skill which goes beyond technical expertise in policy formulation (Wu et al., Citation2015). Howlett and Ramesh (Citation2016) develop the notion of ‘critical capacities’, arguing that while weaknesses in some governance capabilities may be offset by strengths in other areas, certain critical weaknesses can undermine the policy entirely. This line of reasoning also applies to universal health coverage reforms, as our cases demonstrate.

Contemporary provider payment instruments such as capitation (which unless continually adjusted for individual risk levels, demographic profiles, and cost of treatment are ineffective) or DRGs (which need to be adjusted for weights which are based on data such as co-morbidities, etc) require substantial analytical capabilities on the part of program managers. Although multi-lateral agencies (notably the World Bank and the WHO) have published extensive technical manuals (Langenbrunner, Cashin, & O’Dougherty, Citation2009; Liu, Citation2003; Preker & Langenbrunner, Citation2005), large deficits in technical skills remain, as evident in the poor performance of such arrangements in many countries that have adopted them (e.g. Bredenkam et al., Citation2015; Mills, Citation2014).

While technical deficits can be remedied, a critical weakness stems from the lack of political leverage needed to negotiate, and successfully manoeuvre provider payment reform through what is a deeply political process. Changes to how providers are paid, or how powerful elites such as those in the formal private sector or the civil service access services, are resisted if they erode the dominant material interests of these stakeholders (Ramesh, Citation2013). This is why Thailand has been unable to integrate its three programs, or impose a tight financial constraint over its generous civil service program, and India has been unable to rein in the private sector and strengthen its public health system, despite the clear need for these reforms.

The second proposition that emerges is that deficits in ‘political’ capacities (see Wu et al, 205; Bali & Ramesh, Citation2018) can serve as the Achilles’ heel, and undermine provider payment reforms. The more complex the reimbursement instrument, the greater the need for behavioural change, which in turn requires political capacity . Current reform efforts do not adequately emphasise this, and instead focus largely on the tools’ technical dimensions (e.g. how the instrument is calibrated and deployed). Thailand’s case is instructive. The provider payment design that underpinned the UCS was opposed by both the Ministry of Finance and healthcare providers. It was through the political capital and acumen of the newly elected Prime Minister that the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) was able to successfully introduce the provider payment reform in 2002. MoPH was aided by the fact that it owned the majority of hospitals beds in Thailand (Ramesh, Citation2009). Conversely, health agencies in India – in the central as well as state governments – have very limited instruments of control to intervene and shape provider behaviour as most healthcare is financed and delivered privately (Bali & Ramesh, Citation2015a).

Conclusion

An overwhelming majority of healthcare expenditure across the developing world is paid for for by individuals themselves, with limited societal risk pooling. Understandably, governments have focused their attention on increasing public spending on healthcare. This paper reflects on the policy design literature on tool appropriateness and policy capacity to assess health- financing reforms, and makes two overarching arguments. The first is that universal coverage reforms must focus on the ability or the extent to which financing instruments can pool risks across the entire society. Calibrations or parametric changes in health financing instruments, that are intrinsically unable to pool risks beyond a sub-section in the society, will do little to advance the goals of universal healthcare. The second is that the political acumen and leverage are needed to manage and calibrate provider payment instruments. Deficiencies in governance capabilities along this dimension in health agencies, can undermine the effectiveness of these complex instruments (Bales, Citation2018).

The paper makes several contributions. First, it contributes to the ‘new’ design orientation by focusing on individual tools, their institutional pre-requisites, and the capabilities of agencies to use these tools, rather than broad-based institutional approaches (Howlett & Lejano, Citation2012). This in turn contributes to theory building, and developing generalisable propositions on effectiveness in policy design. Second, it draws attention to the appropriateness of policy tool choices used in developing countries to organise healthcare, rather than how much is spent on healthcare. The prevailing orthodoxy to analyse re-distributive programs largely through a fiscal lens (see Levi-Faur, Citation2014) offers limited insights to designing universal coverage reforms.

Acknowledgements

The Authors are grateful to Nihit Goyal, Sarah Bales, Ishani Mukherjee, Mike Howlett, Maurya Daya, Altaf Virani, and Giliberto Capano for constructive comments on an earlier version of this paper. The authors acknowledge generous funding from the National University of Singapore, AcRF grant Universal Coverage Reforms & Health System Governance in Developing Asia .

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Azad Singh Bali

Azad Singh Bali is Lecturer in Public Policy at the University of Melbourne. His research interests lie in comparative public policy and social policy in developing Asia.

M Ramesh

M Ramesh is UNESCO Chair Professor in Social Policy Design, and Professor in Public Policy at the National University of Singapore. His research interests lie in governance and social policy in Asia.

References

- Asher, M., & Bali, A. S. (2015). Public pension programs in southeast Asia: An assessment. Asian Economic Policy Review, 10(2), 225–245.

- Bali, A. S. (2016). Health system design and governance in India and Thailand. PhD Thesis Submitted to the National University of Singapore.

- Bali, A. S., & Asher, M. G. (2012). Coordinating healthcare and pension policies: An exploratory study. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute.

- Bali, A. S., & Ramesh, M. (2015a). Health care reforms in India: Getting it wrong. Public Policy and Administration, 30(3–4), 300–319.

- Bali, A. S., & Ramesh, M. (2015b). Mark time: India’s march to universal health care coverage. Social Policy & Administration, 49(6), 718–737.

- Bali, A. S., & Ramesh, M. (2018). Policy capacity: A design perspective. In Routledge handbook of policy design (pp. 331–344). Routledge.

- Bali, AS., G. Capano, & M Ramesh. (Forthcoming). Anticipating and Designing for Policy Effectiveness. Policy & Society.

- Bales, S. (2018). Evidence in Developing and Refining Capitation Payment for Health Care: The case of Vietnam (PhD Thesis). Singapore: National University of Singapore.

- Bardach, E. (1980). Implementation studies and the study of implements. Paper presented to the American Political Science Association. Berkeley: University of California.

- Béland, D., & Howlett, M. (2016). How solutions chase problems: Instrument constituencies in the policy process. Governance, 29(3), 393–409.

- Bemelmans-Videc, M.-L., Rist, R. C., & Vedung, E. (Eds.). (1998). Carrots, sticks and sermons: Policy instruments and their evaluation. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Bhore, J. (1946). Report of the health survey and development committee. Report. New Delhi: Government of India.

- Blomqvist, Å. (1997). Optimal non-linear health insurance. Journal of Health Economics, 16(3), 303–321.

- Blomqvist, A. (2011). Public sector health care financing. In S. Glied & P. Smith (Eds.), The oxford handbook of health economics (pp. 257–284). Chippenham: Oxford University Press.

- Bonilla-Chacín, M. E., & Aguilera, N. (2013). The mexican social protection system in health (Report, UNICO Studies Series #1). Washington, DC:World Bank

- Borrás, S., & Edquist, C. (2013). The choice of innovation policy instruments. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 80(8), 1513–1522.

- Bredenkamp, C., Evans, T., Lagrada, L., Langenbrunner, J., Nachuk, S., & Palu, T. (2015). Emerging challenges in implementing universal health coverage in Asia. Social Science & Medicine, 145, 243–248.

- Capano, G., & Lippi, A. (2017). How policy instruments are chosen: Patterns of decision makers’ choices. Policy Sciences, 50(2), 269–293.

- Capano, G., & Woo, J. J. (2018). Designing policy robustness: Outputs and processes. Policy and Society, 37(4), 422–440.

- Carey, G., Kay, A., & Nevile, A. (2017). Institutional legacies and ‘Sticky Layers’: WhatHappens in cases of transformative policy change? Administration & Society.

- Chindarkar, N., Howlett, M., & Ramesh, M. (2017). Conceptualizing effective social policy design: Design spaces and capacity challenges. Public Administration and Development, 37(1), 3–14.

- Christensen, T., Laegreid, P., & Wise, L. R. (2002). Transforming administrative policy. Public Administration, 80(1), 153–179.

- Coelho, V., & Shankland, A. (2011). Making the right to health a reality for Brazil’s indigenous peoples: Innovation. Decentralization And Equity, MEDICC Review, 13(3), 50–53.

- Colebatch, H. K. (2018). The idea of policy design: intention, process, outcome, meaning an validity. Public Policy and Administration, 33(4), 365–383.

- Del Río, P. (2018). Managing uncertainty: Controlling for conflicts in policy mixes. In Routledge handbook of policy design (pp. 404–419). Routledge.

- Elmore, R. F. (1978). Organizational models of social program implementation. Public Policy, 26(2), 185–228.

- Employees State Insurance Corporation (ESIC). (2017). Annual Report, 2016–17. New Delhi: ESIC

- Feindt, P. H., & Flynn, A. (2009). Policy stretching and institutional layering: British food policy between security, safety, quality, health and climate change. British Politics, 4(3), 386–414.

- Flanagan, K., Uyarra, E., & Laranja, M. (2011). Reconceptualising the ‘policy mix’for innovation. Research Policy, 40(5), 702–713.

- Gleeson, D., Legge, D., O’Neill, D., & Pfeffer, M. (2011, June). Negotiating tensions in developing organizational policy capacity: Comparative lessons to be drawn. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 13(3), 237–263.

- Government of India. (2012). Rural health statistics in India in 2012. New Delhi: Ministry of Health.

- Gupta, I., & Chowdhury, S. (2014). Public financing for health coverage in India: Who spends, who benefits, and at what cost? Economic and Political Weekly, XLIX, 59–63.

- Peters, Guy B. (2002). The politics of tool choice. Chapter 19. In L. Salamon (Ed.), The tools of government: A guide to the new governance (pp. 562–564). Oxford University Press.

- Hafner, T., & Shiffman, J. (2014). The emergence of global attention to health systems strengthening. Health Policy and Planning, 28, 41–50.

- Hanvoravongchai, P. (2013). Health financing reform in Thailand: Toward universal coverage under fiscal constraints (Report, UNICO Study Series #20). Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Harimurti, P., Pambudi, E., Pigazzini, A., & Tandon, A. (2013). The nuts & bolts of jamkesmas, Indonesia’s Government-financed health coverage program for the poor and near-poor. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Hood, C. (1983). The tools of government. London: Macmillan.

- Hood, C. (2007). Intellectual obsolescence and intellectual makeovers: Reflections on the tools of government after two decades. Governance, 20(1), 127–144.

- Howlett, M. (2011). Designing public policies: Principles and instruments. Oxon: Routledge.

- Howlett, M. (2014). From the ‘old’to the ‘new’policy design: Design thinking beyond markets and collaborative governance. Policy Sciences, 47(3), 187–207.

- Howlett, M. (2018). Matching policy tools and their targets: Beyond nudges and utility maximisation in policy design. Policy & Politics, 46(1), 101–124.

- Howlett, M. (2019). The policy design primer. Oxon: Routledge.

- Howlett, M., Capano, G., & Ramesh, M. (2018). Designing for robustness: Surprise, agility and improvisation in policy design. Policy and Society, 37(4), 405-421.

- Howlett, M., & Cashore, B. (2009). The dependent variable problem in the study of policy change: Understanding policy change as a methodological problem. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 11(1), 33–46.

- Howlett, M., & Del Rio, P. (2015). The parameters of policy portfolios: Verticality and horizontality in design spaces and their consequences for policy mix formulation. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 33(5), 1233–1245.

- Howlett, M., & Lejano, R. P. (2012). Tales from the crypt: The rise and fall (and rebirth?) of policy design. Administration & Society, doi:10.1177/0095399712459725.

- Howlett, M., & Lindquist, E. (2004). Policy analysis and governance: Analytical and policy styles in Canada. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 6(3), 225–249.

- Howlett, M., & Mukherjee, I. (Eds.). (2018). Routledge handbook of policy design. Oxon: Routledge.

- Howlett, M., Mukherjee, I., & Rayner, J. (2014). The elements of effective program design: A two-level analysis. Politics and Governance, 2(2), 1–12.

- Howlett, M., Mukherjee, I., & Woo, J. J. (2015). From tools to toolkits in policy design studies: The new design orientation towards policy formulation research. Policy & Politics, 43(2), 291–311.

- Howlett, M., & Ramesh, M. (1993). Patterns of policy instrument choice: Policy styles,policy learning and the privatization experience. Review of Policy Research, 12(1/2), 3–24.

- Howlett, M., & Ramesh, M. (2016). Achilles' heels of governance: Critical capacity deficits and their role in governance failures. Regulation & Governance, 10(4), 301–313.

- Howlett, M., Ramesh, M., & Perl, A. (2008). Studying public policy. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Howlett, M., & Rayner, J. (2007). Design principles for policy mixes: Cohesion and coherence in ‘new governance arrangements’. Policy and Society, 26(4), 1–18.

- Howlett, M., & Rayner, J. (2013). Patching vs packaging in policy formulation: Assessing policy portfolio design. Politics and Governance, 1(2), 170–182.

- Hsiao, W. C, & Shaw, P. W. (2007). Social health insurance for developing nations. World Bank Publications.

- Jenkins, J. D. (2014). Political economy constraints on carbon pricing policies: What are the implications for economic efficiency, environmental efficacy, and climate policy design? Energy Policy, 69, 467–477.

- Jordan, A., & Lenschow, A. (2010). Environmental policy integration: A state of the art review. Environmental Policy and Governance, 20(3), 147–158.

- Karan, A., Yip, W., & Mahal, A. (2017). Extending health insurance to the poor in India: An impact evaluation of Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana on out of pocket spending for healthcare. Social Science & Medicine, 181, 83–92.

- Kern, F., & Howlett, M. (2009). Implementing transition management as policy reforms: A case study of the Dutch energy sector. Policy Sciences, 42(4), 391.

- Kern, F., Kivimaa, P., & Martiskainen, M. (2017). Policy packaging or policy patching? The development of complex energy efficiency policy mixes. Energy Research & Social Science, 23, 11–25.

- Kirschen, E. S., Benard, J., Besters, H., Blackaby, F., Eckstein, O., Faaland, J., … Tosco, E. (1964). Economic policy in our time. Chicago: Rand McNally.

- Kivimaa, P., & Virkamäki, V. (2014). Policy mixes, policy interplay and low carbon transitions: The case of passenger transport in Finland. Environmental Policy and Governance, 24(1), 28–41.

- Knaul, F. M., & Frenk, J. (2005). Health insurance in Mexico: achieving universal coverage through structural reform. Health Affairs, 24(6), 1467–1476.

- La Forgia, G., & Nagpal, S. (2012). Government-sponsored health insurance in India : Are you covered? Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Langenbrunner, J. C., Cashin, C., & O’Dougherty, S. (2009). Designing and implementing health care provider payment systems: How-to manuals. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Lasswell, H. D. (1971). A pre-View of Policy Sciences. New York: American Elsevier.

- Levi-Faur, D. (2014). The welfare state: a regulatory perspective. Public Administration, 92(3), 599-614.

- Levy, S., & Schady, N. (2013). Latin America’s social policy challenge: Education, social insurance, redistribution. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(2), 193–218.

- Linder, S. H., & Peters, B. G. (1989). Instruments of government: Perceptions and contexts. Journal of Public Policy, 9(1), 35–58.

- Linder, S. H., & Peters, B. G. (1991). The logic of public policy design: Linking policy actors and plausible instruments. Knowledge in Society, 4, 125–151.

- Liu, X. (2003). Policy tools for allocative efficiency of health services. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Lowi, T. J. (1966). Distribution, regulation, redistribution: The functions of government. Public Policies and Their Politics: Techniques of Government Control, 1966, 27–40. WW Norton New York.

- Marten, R., McIntyre, D., Travassos, C., Shishkin, S., Longde, W., Reddy, S., & Vega, J. (2014). An assessment of progress towards universal health coverage in Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS). The Lancet, 384(9960), 2164–2171.

- Maurya, D., & Ramesh, M. (2018). Program design, implementation and performance: The case of social health insurance in India. Health Economics, Policy and Law, 1–22.

- McKee, M., Balabanova, D., Basu, S., Ricciardi, W., & Stuckler, D. (2013). Universal health coverage: A quest for all countries but under threat in some. Value in Health, 16(1), S39–S45.

- Mills, A. (2014). Health systems in low- and middle-income countries. The New England Journal of Medicine, 370(6), 552–667.

- Mohnen, P., & Röller, L.-H. (2005). Complementarities in innovation policy. European Economic Review, 49, 1431–1450.

- Moore, M. H. (1995). Creating public value: Strategic management in government. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Mukherjee, I., & Howlett, M. (2018). Gauging effectiveness: First and second-best policy design. In Routledge handbook of policy design (pp. 375–388). Routledge.

- Painter, M., & Pierre, J. (Eds.). (2005). Challenges to state policy capacity: Global trends and comparative perspectives. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Parsons, W. (2004). Not just steering but weaving: Relevant knowledge and the craft of building policy capacity and coherence. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 63(1), 43–57.

- Peters, B. G. (2015). Pursuing horizontal management: The politics of public sector coordination. Kansas: University Press of Kansas.

- Peters, B. G. (2018). Policy problems and policy design. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Pitayarangsarit, S., & Tangcharoensathien, V. (2009). Sustaining capacity in health policy and systems research in Thailand. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 87(1), 72–74.

- Preker, A. S., & Langenbrunner, J. C. (2005). Spending Wisely: Buying health services for the poor. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Preker, A. S., Liu, Z., Velenyi, E. V., & Baris, E. (2007). Public ends, private means: strategic purchasing of health services. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Radwan, I. India—private health services for the poor Radwan, I. (2005). Report, health. DC: World Bank: Nutrition and Population. Discussion Paper. Washington.

- Ramesh, M. (2009). Healthcare reforms in Thailand: Rethinking conventional wisdom. In M. Ramesh (Ed.), TransforminG Asian Governance (pp. 164–177). Oxon: Routledge.

- Ramesh, M. (2013). Health care reform in Vietnam: Chasing shadows. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 43(3), 399–412.

- Rao, G., & Choudhury, M. (2012). Health care financing reforms in India. Report. New Delhi, India: National Institute of Public Finance and Policy.

- Rao, S. (2015). Inter-state comparisons on health oucomes in major states and a framework for resource devolution for health. Report, Background Study for the 14th Finance Comission. New Delhi, India: Government of India.

- Roberts, M., Hsiao, W., Berman, P., & Reich, M. (2004). Getting health reform right: A guide to improving performance and equity. New York: Routledge.

- Rogge, K. S., & Reichardt, K. (2016). Policy mixes for sustainability transitions: An extended concept and framework for analysis. Research Policy, 45(8), 1620–1635.

- Ross, S. (2011). Collection of social contributions: Current practice and critical issues. In N. Takayama (Ed.), Priority challenges in pension administration. Tokyo: Maruzen.

- Rotberg, R. I. (2014). Good governance means performance and results. Governance. doi:10.1111/gove.12084

- Salamon, L. M. (Ed.). (2002). The tools of government: A guide to the new governance. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Schaffrin, A., Sewerin, S., & Seubert, S. (2014). The innovativeness of national policy portfolios – climate policy change in Austria, Germany, and the UK. Environmental Politics, 23(5), 860–883.

- Schneider, A., & Ingram, H. (1990). Behavioral assumptions of policy tools. Journal of Politics, 52(2), 510–529.

- Somanathan, A., Dao, H. L., & Tien, T. V. (2013). Vietnam Integrating the poor into universal health coverage in Vietnam (Report, UNICO Studies Series #24). Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Sovacool, B. K. (2008). The problem with the ‘portfolio approach’ in American energy policy. Policy Sciences, 41(3), 245–261.

- Srinivasan, T. N. (2011). Growth, sustainability, and India’s economic reforms. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Tangcharoensathien, V., Limwattananon, S., Patcharanarumol, W., Thammatacharee, J., Jongudomsuk, P., & Sirilak, S. (2014). Achieving universal health coverage goals in Thailand: Thevital role of strategic purchasing. Health Policy and Planning 30(9), 1152-1161.

- Tangcharoensathien, V., Suphanchaimat, R., Thammatacharee, N., & Patcharanarumol, W. (2012). Thailand’s universal health coverage scheme. Economic & Political Weekly, 47(8), 53.

- Thomann, E. (2018). “Donate your organs, donate life!” Explicitness in policy instruments. Policy Sciences, 51(4), 433–456.

- Tiernan, A., & Wanna, J. (2006). Competence, capacity, capability: Towards conceptual clarity in the discourse of declining policy skills. Presented at the Govnet International Conference, Australian National University, Canberra.

- Trebilcock, M., & Hartle, D. G. (1982). The choice of governing instrument. International Review of Law and Economics, 2, 29–46.

- Vedung, E., Bemelmans-Videc, M. L., & Rist, R. C. (1997). Policy instruments: Typologies and theories. In E. Vedung, M. L. Bemelmans-Videc, & R. C. Rist (Eds.), Carrots, sticks and sermons: Policy instruments and their evaluation (pp. 21–58). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Vega, J. (2013). Universal health coverage: The post-2015 development agenda. The Lancet, 381(9862), 179–180.

- World Health Organization (2015). The kingdom of thailand health system review. Health Systems in Transition, 5(5). Available online at http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/208216. Accessed on Jan 18, 2019.

- World Bank. (2018). World development indicators Retrieved from http://databank.worldbank.org/

- Wu, X., Ramesh, M., & Howlett, M. (2015). Policy capacity: A framework for analysis. Policy and Society.