?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Studies on innovation and welfare are seemingly unrelated and, currently, scholars of innovation and welfare form distinctive groups. However, recent developments in the fields of business and psychology suggest that a social safety net and the positive mental assets that can be developed by implementing carefully designed welfare programs may stimulate innovative activities within a country. Further, they are closely connected due to their contribution to economic growth, which forms the central tenet of the discourses on both innovation and welfare. In this context, this study uses the patent applications filed under the Patent Co-operation Treaty and social spending data of 35 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries for the period 2000–2015 to investigate the effect of welfare on innovation. Contrary to the widespread belief that welfare spending can undermine innovative potential, we argue that welfare can harness a country’s innovative potential and contribute to the country’s long-term growth.

1. Introduction

Innovation is a popular mantra used by academics and policy makers having a keen interest in economic growth and social change. For example, Schumpeter’s entrepreneurship theory argues that innovations introduced by entrepreneurs serve as the source of dynamic economic growth and social change in a capitalist society (Schumpeter, Citation1934, Citation1942). Further, Romer’s new growth model describes innovation as a key factor of sustainable long-term economic growth (Romer, Citation1986, Citation1990). Overall, innovation has been the central topic of mainstream discourse and research on economic growth in the fields of business and economics.

Over the years, the significance of innovation in economic growth has encouraged researchers to examine its determinants. The most well-known approach that explains the drivers of innovation in a country is the knowledge production function model (Griliches, Citation1979; Jaffe, Citation1989). According to this model, the key inputs of innovation are direct, as well as indirect, research and development (R&D) investments. This approach, which underscores the linear relationship between R&D and innovation, was later questioned by the new system-based approach, that is, the national innovation system model. According to the new approach, all the relationship networks among the industry, academia, and government are critical elements of a system that is geared toward innovation (Lundvall, Citation1992). Although the new system-based approach constitutes a theoretical step to explain the phenomenon of innovation, the ‘interconnectedness of everything’ approach followed by this model is not always helpful in clarifying the complex network of social and other factors that may significantly affect innovation. In this context, we particularly focus on the role of governmental policy in fostering innovation. Based on cross-country comparisons, we hypothesize that welfare programs strongly influence innovation outcomes.

Welfare research often displays a keen interest in economic growth. Although one group of researchers has primarily investigated the potentially detrimental effects of welfare expenditure on economic growth (Ding, Citation2014), many scholars argue that welfare spending may serve as a significant stimulus for economic growth (Lindert, Citation2004). Similarly, another school of thought, which is often referred to as the wage-led growth school, focuses on the effects of consumption generated by the increase in income resulting from welfare spending (Onaran & Stockhammer, Citation2016). In addition to these demand-side arguments on the role of welfare in economic growth, there are relatively unexamined supply-side arguments, according to which innovation plays a major role. According to the recent literature on the different varieties of capitalism, a welfare state may have significant influence in shaping a country’s innovative potential (Estevez-Abe, Iversen, & Soskice, Citation1999; Hall, Citation2015), which implies that welfare may play a latent role in facilitating innovation and the resultant growth.

This study investigates the aforementioned supply-side linkage between innovation and welfare. Although the two appear unrelated, they are closely linked through multiple supply-side channels that have not been examined in detail to date. Conventional wisdom suggests that welfare spending can be a significant impediment to the long-term economic growth of a country, which may undermine its innovative potential. However, we argue that welfare can be conducive to harnessing a country’s innovative capacity and can contribute to its long-term growth. We develop this argument by theoretically connecting the concept of innovation and welfare according to the following two points:

First, recent developments in psychology reveal that a positive psychological state, such as happiness, can result in wider and richer momentary thought–action repertories, which offer a greater opportunity to build more diverse, novel, and innovative reactions to surrounding environments (Carr, Citation2011; Fredrickson, Citation2001). In addition, the capability theory developed and elaborated on by Sen (Citation1980) and Nussbaum (Citation2003) suggests that welfare support that enhances the capabilities of individuals can significantly enhance their subjective well-being. These microlevel theories in the fields of psychology and economics can strengthen the argument for the role of welfare in promoting innovations.

Second, recent business research provides a slightly different perspective that bridges the apparent gap between innovation and welfare. Studies on opportunity-driven entrepreneurs reveal that their success rates improve when the new endeavors of businesses’ founders are coterminous with their original jobs (Grant, Citation2017). The reason is that the security offered by regular jobs enables entrepreneurs to adopt more risky but creative approaches. Similarly, welfare programs may also serve as a risk-hedging mechanism for entrepreneurs, which can stimulate more innovative and sometimes even radical market-entry strategies and positions.

Based on these arguments, this study investigates the relationship between innovation and welfare. Using the patent and welfare program spending data of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, we show that welfare is an important support system for innovative activities and argue that innovation and welfare policies can be considered in tandem within a more comprehensive framework.

2. Bridging innovation and welfare

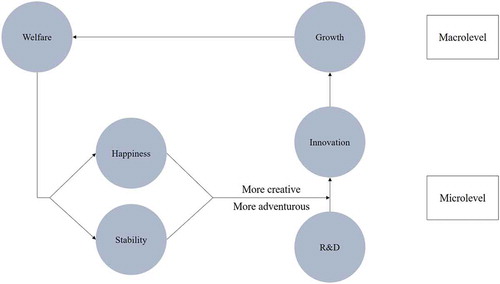

Disentangling the complex relations between innovation and welfare is an onerous task. This is because innovation usually occurs at the level of an individual or a firm (i.e. the microlevel), whereas welfare is more concerned with macrolevel issues, such as the economic growth of a country. Although many factors associated with innovation and welfare operate at different levels, they are all interconnected. Accordingly, their relationships are more complicated than they seem to be. Hence, the macrolevel relationships between growth and welfare have been the topic of intense debate; however, such debates have largely overlooked the microlevel relationships between innovation and welfare. In addition to the discrepancy between the levels of interest in micro and macro issues held by them, scholars of innovation and of welfare rarely overlap. As a result, there have been only limited research attempts to theoretically explain the potentially important but seemingly nonexistent relationships between innovation and welfare. Hence, based on new developments in the psychology, economics, and business literatures, this section develops a microlevel argument to explain how welfare may catalyze innovations. In particular, we propose two notable linkages that form a bridge between welfare and innovation by augmenting the returns on R&D (i.e. innovation inputs).

Path I: linkage among welfare, happiness, and innovation

Schumpeter (Citation1947), the progenitor of innovation research, defines innovation as ‘ … getting a new thing done … ’ (p. 153). This definition implies that the essence of innovation is the creation of something new. In general, ‘new’ implies something that has not existed before. However, in the world of innovation, it can imply creative recombinations of existing things and ideas, as well. Many historical examples of innovation illustrate the latter point (Hargadon, Citation2003). Similarly, Schumpeter (Citation1934) argues that the essence of entrepreneurship, that is, the driver of innovation, is recombinant searching.

One of the most important microlevel determinants of innovation in the literature is cognitive diversity.Footnote1 Recent studies argue that individuals and groups with a high level of cognitive diversity demonstrate more creative problem-solving skills (Page, Citation2007). The significance of creativity in innovation research has an important implication since creativity serves as a unique linking pin that bridges innovation and welfare, which have rarely been discussed in tandem. Cognitive diversity can provide a greater probability of recombining existing knowledge and ideas in nonconventional ways. For instance, Page (Citation2007) showed that students with average skills but coming from diverse backgrounds perform better in solving complex problems compared to those with more advanced skills but coming from a uniform background. In the same manner, based on numerous cases and empirical analyses, Feldman (Citation1999), Hargadon (Citation2003), Bae and Koo (Citation2009) proved that a diverse knowledge base clearly stimulates technological innovation and entrepreneurship.

Further, research on individual mental status that may affect cognitive diversity deserves special attention. In particular, recent developments in the field of psychology focus on how positive mental assets, such as happiness and optimism, contribute to the formation of unique and novel ideas. A common conclusion of these studies is that individuals with a positive mental status are more likely to produce innovative outcomes. For instance, MacLeod (Citation1973) found that happy individuals are more likely to discover innovative solutions to complex problems, and Gasper (Citation2004) reported that individuals with a negative mental status often display a tendency to resist the adoption of new ideas. Such research leads to interesting questions on the mechanism by which happiness influences creativity.

The most systematic research on the relationship between positive mental status and creativity is encompassed in the broaden-and-build theory developed and elaborated on by Fredrickson (Citation2001, Citation2009). The theory posits that a positive mental status broadens the scope of human attention. Accordingly, happy individuals are more open to new ideas and more likely to make creative cognitive choices (Carr, Citation2011). In particular, a positive mental status enables individuals to pay more attention to their surroundings and helps them develop more diverse and novel reactions to any changes in their environment based on wider and richer thought–action repertories. In this context, an extrovert personality, which is often associated with a positive mental status, is often believed to contribute to the development of creative ideas. Many studies have provided empirical evidence to support the hypothesis that a potential relationship exists between happiness and creativity (Cohn & Fredrickson, Citation2009; Fredrickson, Citation2009; Fredrickson & Losada, Citation2005).

The findings derived from the broaden-and-build theory are completely aligned with the aforementioned argument on the benefits of cognitive diversity. Since a positive mental status is associated with more varied and diverse mental reactions to environmental changes, happy individuals are likely to develop more diverse cognitive bases than others. Hence, happy individuals with diverse cognitive bases often demonstrate more innovative behaviors than others. In addition, as illustrated by Page (Citation2007), this line of argument with respect to happy individuals can be extended to the group level. Page argued that a diverse group of problem-solvers generally outperforms a homogenous group. This is an intuitive argument since the cognitive bases of a homogenous collection of individuals can be analogous to the cognitive base of a single person. Accordingly, a collection of happy individuals with a wide range of cognitive perspectives is likely to form a highly capable organization. Similarly, the existing literature on entrepreneurship underscores the importance of cognitive diversity at the firm level. For instance, based on a sample of 496 technology ventures, Gruber, MacMillan, and Thompson (Citation2013) showed that diverse knowledge bases among founding team members are important considerations in identifying different market opportunities. Further, Ruef (Citation2002) revealed that an entrepreneur’s nonredundant social networks, through which he or she obtains new information, are critical to entrepreneurial success.

In addition, recent studies on happiness have given rise to a debate on the ways in which welfare can influence a society’s innovative potential. One of the most important topics in happiness research is the Easterlin paradox (Easterlin, Citation1974, Citation1995), in which income levels are not clearly associated with happiness levels across time, as well as countries. A potential explanation for the paradox can be found in the capability theory introduced by Sen (Citation1980) and Nussbaum (Citation2003). The capability of an individual is defined as the set of opportunities that can be freely pursued by him or her. This set comprises a wide range of components, such as the ability to maintain good health, think and reason, ensure adequate nourishment, and access safe shelter (Nussbaum, Citation2003).

According to recent studies, human capabilities are an important source of human happiness. Unlike income, for which the relative level is important to most people, absolute levels are important in the case of human capabilities. For instance, in terms of my level of life satisfaction, how much my neighbor earns may be as important as how much I earn. However, people rarely compare their own state of health with that of others. This distinction provides some explanations for the paradox raised by Easterlin several decades ago. Contrary to widespread belief, income is less important for the attainment of happiness since relative, rather than absolute, income levels often play a crucial role in determining individuals’ levels of life satisfaction. Accordingly, an increase in income across the board may not result in an increase in the level of average happiness (Easterlin, Citation1995). On the other hand, the extent to which human capabilities are assured in a society may be a crucial factor affecting the average level of happiness.

Further, it is noted that most issues discussed in the discourse on human capability are closely related to various fields of welfare policy (e.g. the fields of health, safety, and education). When a society fails to provide basic health and education services to everyone, some individuals will likely fail to realize their true potential. Accordingly, well-designed welfare programs that enhance human capabilities may serve as an important source of individual happiness in a society. Since happiness stimulates creativity, the aforementioned discussion suggests that well-designed welfare policies may enhance innovative outcomes by augmenting the effects of innovative inputs. In other words, happy individuals can provide a greater return on R&D investment by being more creative. Therefore, we can hypothesize that welfare is associated with innovation, since it enhances the effects of R&D inputs by fostering high levels of individual happiness.

(2) Path II: linkage among welfare, stability, and innovation

The previous section provides explains how welfare influences innovation through its link with the level of a society’s happiness. A more direct investigation on the effects of welfare on innovation and entrepreneurship is found in the literature on the varieties of capitalism (VofC). The VofC approach provides a sophisticated account of welfare and innovation. By placing firms at the center of their analysis, researchers who employ this approach analyze institutional complementarities among industrial relations, corporate governance, vocational training and the educational system, inter-firm relations, and social protection. Ultimately, they distinguish between two distinct types of capitalism, that is, liberal market economies (LMEs) and coordinated market economies (CMEs) (for more details, see Hall and Soskice (Citation2001)). Rather than adopting a uniform concept of innovation, the VofC literature argues that LMEs with a flexible labor market tend to produce radical innovation, whereas CMEs mainly offer process innovation. In particular, the theory posits that the strong social protection and high level of job security offered by CMEs are facilitators of process innovation, but barriers to radical innovation (Estevez-Abe et al., Citation1999).

However, subsequent studies have challenged the distinction between LMEs/radical innovation versus CMEs/incremental innovation, and the stability of the two types of capitalism over time (Akkermans, Castaldi, & Los, Citation2009; Taylor, Citation2004). Such studies argue that there is no empirical evidence to support a division between LMEs and CMEs with respect to innovation. For instance, some argue that the model adopted by Nordic countries is different from the Germany-led CME model (Maliranta, Mättännen, & Vihriälä, Citation2012). According to Lorenz (Citation2015), welfare may be a significant factor fostering radical innovation in Nordic countries. It is essential that radical innovation is accompanied by the labor mobility of experts having tacit knowledge; however, such an assertion holds only when the mobility is realized with both well-developed unemployment protection and active labor market policies. This so-called ‘flexible security’ system can promote the accumulation and transfer of experts’ tacit knowledge in localized or industry-specific networks, stimulating more radical innovations.

Although the VofC literature clarifies a welfare state’s effects on innovation to some extent, it does not provide a detailed explanation of the mechanism by which a welfare state influences innovation activities. In particular, these studies overlook the potentially important microlevel effects of welfare on individual attitudes toward risk. A better microlevel account on the role of welfare in fostering innovation is found in the business literature pertaining to stability and risk-taking behaviors. According to recent research on opportunity-driven entrepreneurship, entrepreneurs who choose to maintain their original jobs during the initial stages of their new business ventures are more likely to see their businesses survive than those who choose to leave existing positions and exclusively commit to their new ventures (Raffiee & Feng, Citation2014). Similarly, Filippetti and Guy (Citation2016) found that workers who are eligible for unemployment benefits or who have employment security tend to develop their specific skills and engage themselves in innovative activities. Such empirical findings can be considered from the perspective of the risk-hedging concept. In this context, risk-hedging entails entrepreneurs or workers making risky but novel and innovative bets that might not have been plausible options if there had been no access to a social safety net. Similarly, McKenna (Citation2017) observes that access to free healthcare and education, as well as good public infrastructure, is a reason for the recent upsurge in Swedish start-ups. Contrastingly, Fairlie, Kapur, and Gates (Citation2008) maintain that the fear of being without health insurance deters entrepreneurial employees from leaving their firms and starting their own businesses in the United States.

The value of the social protection dimension of a welfare system can be evaluated from the perspective of its provision of equal opportunity, which can enhance risk-taking behaviors, particularly among disadvantaged population groups. Celik (Citation2015) argues that an environment that promotes unequal opportunity may cause the misallocation of talent, which can result in low productivity in a society. Bell, Chetty, Jaravel, Petkova, and Van Reenen (Citation2017) argue that the children of the top 10th percentile of high-income parents are twice as likely to become inventors as the children of low-income parents below the 80th percentile, even after controlling for these children’s third-grade mathematics test scores. The two aforementioned studies underscore the importance of the universal social investment approach. Further, they reveal the significance of social protection, which provides economic stability that can ensure equal opportunity for all and facilitate risk-taking behavior. In this context, Hemerijck (Citation2017) notes the important ‘buffering’ role of social protection. A well-designed social protection system can increase productivity by facilitating risk-taking behaviors.

The current discussion provides an important theoretical rationale for the provision of welfare support to stimulate risky and innovative business activities. When individuals feel secure, they tend to become more innovative and adventurous. Hence, we hypothesize that welfare can positively augment the rate of returns on innovation inputs (i.e. R&D investments) by providing security to individuals and, thereby, stimulating their risk-taking behaviors.

The seemingly unrelated issues of welfare and innovation can be interconnected, since the availability of welfare support may harness the innovative potential of individuals by enabling them to take happiness-enhancing, as well as risk-hedging, paths. Welfare may not be a direct input with respect to innovation. However, it may serve as a critical moderator of innovative outcomes by making individuals more creative and adventurous. A summary of the presented model is illustrated in .

3. Model and method

We developed a model of innovation production to verify the hypothesis presented above as follows:

where represents the number of patent applications per ten thousand people;

represents the welfare expenditure in three areas (i.e. social, public health, and tertiary education expenditures) as a percentage of the gross domestic product (GDP);

represents the expenditure on R&D as a percentage of GDP, which indicates the level of R&D investment relative to the size of each country’s economy; and

represents the interaction term between the two factors. The interpretation of the coefficient

requires special attention. The interaction term is included to reflect the moderating role of welfare on innovative outcomes. Therefore, the presence of

suggests that the marginal effects of R&D expenditure can be augmented with an increase in welfare expenditure since the slope of

may change according to the level of

.

The proposed dependent variable innovation can be measured using the number of patent applications. Patents have been considered an important indicator of innovative activities in many previous studies (Griliches, Citation1984; Jaffe, Citation1986; Jaffe, Trajtenberg, & Fogarty, Citation2000; Koo, Citation2006). However, one should exercise caution while employing patent statistics as a measure of innovation. Although several studies have empirically validated the hypothesis that patent rates represent the level of innovation (Acs, Anselin, & Varga, Citation2002; Acs & Audretsch, Citation1989), many other studies have questioned the use of patents as a proxy for innovation counts (Griliches, Citation1990; Hall, Helmers, Rogers, & Sena, Citation2013). In this context, an important measurement issue is the variation in patenting propensities across industries, as well as differences in firm sizes. These studies clarify that patent statistics should be utilized as innovation counts with caution. Kleinknecht and Reinders (Citation2012) suggested the need to control for industry heterogeneity in empirical analysis. From a practical perspective, another extensively recognized issue is whether to use application or registration statistics of patents as a representative of the level of innovation. According to the Frascati Manual (OECD, Citation2015), the use of application statistics is preferred over that of registration statistics, since patent applications are believed to better represent the R&D output (Acs & Audretsch, Citation1989). Although some concerns regarding industry heterogeneity with respect to patent activity have been expressed, we chose to use patents as a proxy measure for innovation due to two reasons. First, the unit of analysis in our study is the state, which aggregates patents from the complete spectrum of industries. Second, other than patents, there is no better alternative measure for innovation for utilization in a cross-country comparison.Footnote2

Welfare expenditure variables in the following three areas constitute a key explanatory variable of the proposed model: social, public health, and tertiary education expenditures. The social expenditure data compiled by the OECD encompass a wide range of welfare and social policy categories, such as expenditures on the elderly, families, survivors, incapacity-related benefits, health, active labor market programs, unemployment, and housing (OECD, Citation2016). These data represent a country’s overall level of commitment to welfare services. To construct the social expenditure variable, we excluded public pension to better reflect the overall safety net available to the economically active population. The other two areas comprise more specific fields of welfare. Public health expenditure is the sum of all the public spending on public health. The data compiled by the World Health Organization cover preventive and curative health services, family planning activities, nutrition programs, and emergency aid.Footnote3 The tertiary education expenditure data obtained from the OECD include all the public expenditures on tertiary education. They primarily cover the spending on the instructional and ancillary services available to students and their families. These data reflect the investment of a country on supporting people at advanced educational levels.

Some other factors that influence the level of innovation have emerged from the knowledge production function approach (Griliches, Citation1979). The most important input for the generation of new knowledge (i.e. innovation) is investment in R&D. Accordingly, this model includes the total expenditure on R&D carried out by all the companies, research institutes, universities, and government laboratories in a country. In addition to R&D expenditure, this model incorporates a variable that is designed to capture the level of human capital. Further, the number of graduates from tertiary educational institutions and research programs represents a country’s human capital input (OECD, Citation2017).

To control for the economic and regulatory environment of a country, three variables were included in the proposed model. First, the unemployment rate captures the degree to which an economy utilizes its human resources. Since a low unemployment rate implies heightened competition for human resources between incumbents and newcomers in an economy, the unemployment rate is believed to be closely related to the formation of new firms and subsequent innovations (Evans & Leighton, Citation1990; Storey, Citation1991). Second, the business environment is assessed according to the gap between an economy’s current performance and its optimal conditions to start a new business at a specific point in time. The measure ranges from 0 to 100 and is designed to capture a country’s overall entrepreneurial environment in comparison with a hypothetical threshold comprising the best performances for all time intervals. Finally, the variable of regulatory quality represents the ability of a country to formulate and implement sound policies and regulations. Regulatory quality may play an important role in shaping the economy, particularly in emerging technology-driven markets. Therefore, it is probably closely associated with innovative entrepreneurial activities, as well. The appendix depicts a list of the descriptions of all variables and their sources.

To examine the proposed hypothesis on the relationship between innovation and welfare, we constructed a unique dataset covering 35 OECD countries for 16 years, 2000–2015. Some missing values were interpolated using Stat’s ipolate function. The panel structure of the data enables us to control for country-specific heterogeneity. A random-effects model incorporates country-specific errors, whereas a fixed-effects model incorporates country-specific intercepts. A significant difference between the two models is their treatment of time-invariant error terms, in terms of whether they are correlated with independent variables. A random-effects model is productive when the assumption of the independent time-invariant error term is not violated. If the results of such a model are estimated when the independent time-invariant error assumption is not satisfied, the parameter estimators are likely to become biased. Therefore, the fixed-effects model may be preferable over the random-effects one unless strong evidence for the independent time-invariant error term is found (Johnston & DiNardo, Citation1997).

An alternative approach to conducting panel data analysis is the Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) model proposed by Liang and Zeger (Citation1986). A GEE model has a distinctive advantage over conventional fixed- and random-effects models since it requires only the first and second moments of the dependent variable. This indicates that asymptotically consistent and unbiased estimators can be obtained without considering parametric assumptions regarding unknown distributions and the correlation structure of observations (Koo, Yoon, Hwang, & Barnerjee, Citation2013; Liang & Zeger, Citation1986). A major advantage of the GEE model is that it produces reasonably accurate standard errors that create confidence intervals with the correct coverage rates (Hanley, Negassa, & Forrester, Citation2003). Accordingly, we have reported the estimation results derived from the GEE model and from the random- and fixed-effects models to conduct a robustness check. In addition, we have reported the results of a Hausman test to evaluate the specifications of the random- and fixed-effects models and those of the Wald test in relation to the GEE model.

4. Results

depicts the bivariate correlations among the variables. Patenting activities (or the innovation output) are very highly correlated with R&D expenditure (or the innovation input), as expected. The table demonstrates that all the welfare variables (social, public health, and tertiary education expenditures) are closely associated with the level of patent. In addition, the correlations between independent variables are reasonably low, which implies that the provided list of independent variables captures their unique contributions to the dependent variable. The only exception is the correlation between social and public health expenditures (r = 0.77). However, we estimated three separate regression models on different areas of welfare to avoid the multicollinearity issues that may occur as a result of overlaps between these fields of welfare.

Table 1. Bivariate correlations.

The effects of the welfare policy on innovation were evaluated based on the following three key variables: 1) the share of social expenditure (except public pensions) as a percentage of GDP, 2) the share of public health expenditure as a percentage of GDP, and 3) the share of tertiary education expenditure as a percentage of GDP. We separately estimated the effects of these three welfare variables, whose results are presented in –. Each welfare model was divided into two sub-models (the welfare variable–only base model and the interaction variable model), and their results were estimated using fixed, random, and GEE methods. Further, six models were estimated for each welfare variable, and the results of the 18 models are presented in –.

Table 2. Regression results (Welfare: social expenditure).

Table 3. Regression results (Welfare: public health expenditure).

Table 4. Regression results (Welfare: tertiary education expenditure).

As predicted by the knowledge production function model, the innovation input (i.e. R&D expenditure) is a critical factor influencing innovation in all the nine base models (–). These results are consistent and robust. Regarding welfare spending variables, social and public health expenditures are positive and statistically significant; however, tertiary education expenditure does not show any statistical significance in the base models.

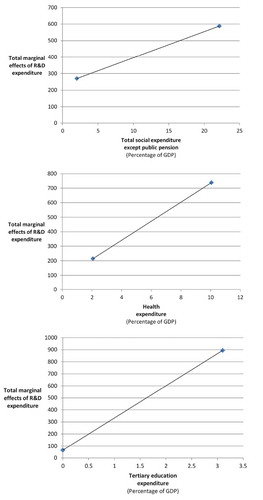

The R&D expenditures mentioned in the interaction models are somewhat inconsistent. The R&D expenditure is positive and statistically significant in the interaction model using social expenditure as a welfare variable (). On the other hand, the R&D expenditure loses its statistical significance in the interaction models that incorporate public health and tertiary expenditures as welfare variables ( and ). However, the results of the interaction models should be interpreted with caution. The coefficient of the main variable in an interaction model represents the marginal effect of the main variable when the level of the interacted variable is zero. In other words, the coefficients of R&D expenditure in the interaction models indicate the marginal effect of R&D expenditure when welfare spending is zero. Therefore, the marginal effect of R&D expenditure in interaction models should be interpreted as a composite effect, which accounts for the coefficients of the main and interaction variables in tandem.Footnote4 This approach is illustrated in , which reveals how the total marginal effects of R&D change according to the levels of welfare spending in the three different fields of welfare. The coefficients of the interaction terms in the interaction models are all statistically significant, and reveals that the total marginal effects of R&D expenditure are augmented when the welfare spending increases. The results strongly imply that welfare expenditure moderates the effects of R&D expenditure.

These results are well-aligned with the proposed hypothesis on the relationship between innovation and welfare. Welfare spending does not simply mean the provision of certain public services. Rather, it entails potentially important implications for innovation and subsequent growth. The results presented in – suggest that the consideration of welfare as a subject isolated from innovation (and, thereby, potentially growth, as well) may likely cause policy mistakes. Although they appear unrelated, our evidence reveals that innovation and welfare are potentially interrelated, which means that the extent to which countries invest in welfare programs may affect the effectiveness of their efforts to foster innovation. The proposed hypothesis clearly explains the mechanism by which welfare influences innovation. When appropriate welfare services are implemented and innovators possess positive mental attitudes fostered by carefully designed welfare programs, they may become more creative and risk-seeking, which increases the probability that they develop path-breaking and disruptive innovations. Accordingly, the conventional discourse on the issue of welfare, which has taken place without facilitating serious consideration of innovation and growth, is probably flawed. This result strongly suggests that welfare and innovation policies should be discussed in the context of a more comprehensive framework.

A careful review of the results depicted in – suggests another interesting implication with respect to the relative importance of various welfare areas as catalysts of innovation. The augmentation of the marginal effects of R&D spending is highest in the area of tertiary education expenditure. In the GEE model, a 1 percent increase of tertiary education spending as a share of GDP increases the marginal effects of R&D by 267.43 (the number of patents per 10,000 people). On the other hand, when social expenditure and public health expenditure increase by 1 percent as a share of GDP, the marginal effects of R&D are expected to increase by 15.81 and 65.67, respectively. These results support the conventional view of education as investment in human capital. In particular, government spending on higher education clearly has some characteristics of a welfare program since it provides greater opportunities for the poor than the rich and has important implications for innovation in terms of fostering productive R&D.

One noteworthy results is that, contrary to conventional wisdom, the effect of college graduates on innovation activities is statistically insignificant in all 18 models. This finding can be interpreted as a result of variable aggregation. It is noted that this variable includes all graduates who completed tertiary and advanced research programs. Accordingly, humanities and social science graduates, who are not directly associated with innovation activities, are included in the variable construction, as well. Such an aggregation may have contributed to the unexpected loss of statistical significance.

In addition to the examination of welfare variables as determinants of innovation, it is worthwhile to pay some attention to the effects of regulatory quality on innovation. The regulatory quality consistently displays a very strong association with the level of patent applications in all the 18 models depicted in –. The ability of the government to introduce sound policies and regulations is a key factor fostering innovative activities. A high-quality regulatory environment implies the existence of transparent and predictable legal and regulatory systems. Such an environment entails the repeal of unnecessary laws and regulations in areas where entrepreneurs may be free to realize their innovations, as well. It is noted that scientists and engineers are not the only concerned parties in the realm of innovation. The government, who provides a safety net and promulgates sound policies and regulations, assumes the central role in the promotion of innovative activities, as well.

5. Conclusions

This study examined how welfare policies encourage innovation. It is noted that scholars of innovation and welfare form distinctive groups. Accordingly, their different preoccupations are rarely holistically addressed in either academic or policy debates. However, recent developments in the fields of business and psychology suggest that the presence of adequate social policies and the development of positive mental assets in individuals through carefully designed welfare programs may stimulate innovative activities in a country. We employed panel regression models to analyze three areas of welfare: social, public health, and tertiary education expenditures. Our results revealed that welfare spending, regardless of its target, has a strong impact on the marginal effects of R&D investment. In other words, countries with a higher share of welfare spending as a percentage of GDP tend to produce more numbers of patents for each dollar invested by them in R&D. This implies that welfare spending can influence the level of innovative activities.

Our findings have particularly important policy implications. Often, welfare policies are discussed in a completely different context than innovation policies. To facilitate innovation, many countries have expended every effort to overhaul their scientific, technological, and industrial policies. However, our findings strongly suggest that apparently unrelated innovation and welfare policies should be examined in tandem in a more comprehensive framework. The existing literature argues that creativity is the key to entrepreneurship and innovation and that happier people with a reasonable level of economic security and autonomy are likely to be more creative. Further, we know that the welfare state, which has as its functions social investment and social protection, provides economic stability and autonomy. Although this study does not provide a detailed discussion on the causal mechanism by which the welfare state interacts with a country’s innovation level, the analysis conducted by the study, along with the literature review, confirms that there is a strong causal link between the two. Therefore, countries that pursue high levels of innovation should carefully redesign and strengthen their welfare policies.

Finally, our findings provide indirect insights into the relationship between welfare and economic growth. For many years, the relationship between the welfare state and economic growth was strongly debated in the academic and political arenas. Further, numerous studies have investigated whether the welfare state promotes or undermines economic and productivity growth; nonetheless, they could achieve only mixed results. However, our findings suggest that welfare, through stimulating innovations, may be conducive to economic growth. Further, future research should focus on the innovation linkage between welfare and economic growth.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jun Koo

Jun Koo is a professor in the Department of Public Administration at Korea University. He has diverse research interest including regional development, innovation and entrepreneurship, and happiness. His research has appeared in many international journals and books in public policy, regional science, urban planning, and business.

Young Jun Choi

Young Jun Choi is an Associate Professor in the Department of Public Administration at Yonsei University. His research interests include aging and public policy, social investment policy, comparative welfare states, and comparative methods. His research has been published in international journals including Journal of European Social Policy, International Journal of Social Welfare, Ageing and Society, and Government and Opposition.

Iljoo Park

Iljoo Park is a research associate in the Institute for Future Government at Yonsei University. She has earned her Ph.D. in Public Administration from Korea University in 2018. Her research interests include entrepreneurship, innovation, and self-efficacy.

Notes

1 This paper focuses on two limited individual-level paths associated with innovative activities. However, a well-established body of literature that examines the individual characteristics associated with innovation and entrepreneurship is currently available. Some examples of these characteristics are educational and technical backgrounds (Shane, Citation2000), networks (Elfring & Hulsink, Citation2003), industry clusters, and knowledge spillovers (Koo & Cho, Citation2011). Further, see Block, Fisch, and Pragg (Citation2017) for a more detailed discussion on the individual traits that differentiate innovators and entrepreneurs.

2 Some studies have employed direct measures of innovation (Feldman & Audretsch, Citation1999). However, the availability of such measures is very limited.

3 It is noted that the United States occupies a unique position in health expenditure. The United States spends the largest amount in total healthcare; however, its public health expenditure is only slightly above the average among OECD countries (https://www.oecd.org/health/healthspendingcontinuestooutpaceeconomic growthinmostoecdcountries.htm).

4 Similarly, the negative but statistically significant coefficients of the public health and tertiary expenditure variables in the interaction models should be interpreted in combination with their interaction terms. The total marginal effects of all the welfare variables are positive at the average level of R&D expenditure.

5 OECD defines private social expenditure as the interpersonal redistributional spending by private-sector programs that requires the compulsory participation of individuals or employers by law and regulations (OECD, Citation2007). Therefore, it suits the profile of welfare definition considered by this study.

References

- Acs, Z., Anselin, L., & Varga, A. (2002). Patents and innovation counts as measures of regional production of new knowledge. Research Policy, 31, 1069–1085.

- Acs, Z. J., & Audretsch, D. B. (1989). Patents as a measure of innovative activity. Kyklos, 42, 171–180.

- Akkermans, D., Castaldi, C., & Los, B. (2009). Do ‘liberal market economies’ really innovate more radically than ‘coordinated market economies’? Hall and Soskice reconsidered. Research Policy, 38, 181–191.

- Bae, J., & Koo, J. (2009). The nature of local knowledge and new firm formation. Industrial and Corporate Change, 18, 473–496.

- Bell, A. M., Chetty, R., Jaravel, X., Petkova, N., & Van Reenen, J. (2017). Who becomes an inventor in America? NBER Working Paper Series, 24062.

- Block, J. H., Fisch, C. O., & Pragg, M. V. (2017). The Schumpeterian entrepreneur: A review of the empirical evidence on the antecedents, behaviour and consequences of innovative entrepreneurship. Industry and Innovation, 24, 61–95.

- Carr, A. (2011). Positive psychology: The science of happiness and human strengths. East Sussex: Routledge.

- Celik, M. A. (2015). Does the cream always rise to the top? The Misallocation of Talent and Innovation. Unpublished, University of Pennsylvania.

- Cohn, M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2009). Positive emotions. In S. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology (pp. 13–24). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ding, H. (2014). Economic growth and welfare state: A debate of econometrics. Journal of Social Science for Policy Implications, 2(2), 165–196.

- Easterlin, R. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. David & M. Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in honour of Moses Abramovitz (pp. 89–125). New York: Academic Press.

- Easterlin, R. (1995). Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 27, 35–47.

- Elfring, T., & Hulsink, W. (2003). Networks in entrepreneurship: The case of high-technology firms. Small Business Economics, 21, 409–422.

- Estevez-Abe, M., Iversen, T., & Soskice, D. (1999). Social protection and the formation of skills: A reinterpretation of the welfare state. Paper presented at the 95th American Political Science Association Meeting, Atlanta.

- Evans, D. S., & Leighton, L. S. (1990). Small business formation by unemployed and employed workers. Small Business Economics, 2, 319–330.

- Fairlie, R. W., Kapur, K., & Gates, S. M. (2008). Is employer-based health insurance a barrier to entrepreneurship? RAND Working Paper, No. WR-637-EMKF.

- Feldman, M. P. (1999). The new economics of innovation, spillovers and agglomeration: A review of empirical studies. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 8, 5–25.

- Feldman, M. P., & Audretsch, D. B. (1999). Innovation in cities: Science-based diversity, specialization and localized competition. European Economic Review, 43, 409–429.

- Filippetti, A., & Guy, F. (2016). Skills and social insurance: Evidence from the relative persistence of innovation during the financial crisis in Europe. Science and Public Policy, 43, 505–517.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. American Psychologist, 56, 218–226.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2009). Positivity. New York: Crown.

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Losada, M. (2005). Positive affect and the complex dynamics of human flourishing. American Psychologist, 60, 678–686.

- Gasper, K. (2004). Permission to seek freely? The effect of happy and sad moods on generating old and new ideas. Creative Research Journal, 16, 215–229.

- Grant, A. (2017). Originals: how non-conformists move the world. New York: Penguin Books.

- Griliches, Z. (1979). Issues in assessing the contribution of research and development to productivity slowdown. Bell Journal of Economics, 10, 92–116.

- Griliches, Z. (Ed.). (1984). R&D, patents, and productivity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Griliches, Z. (1990). Patent statistics as economic indicators: A survey. Journal of Economic Literature, 28, 1661–1707.

- Gruber, M., MacMillan, I. C., & Thompson, J. D. (2013). Escaping the prior knowledge corridor: What shapes the number and variety of market opportunities identified before market entry of technology start-ups? Organizational Science, 24, 280–300.

- Hall, B., Helmers, C., Rogers, M., & Sena, V. (2013). The importance (or not) of patents to UK firms. Oxford Economic Papers, 65, 603–629.

- Hall, P. (2015). Varieties of capitalism. In R. Scott & S. Kosslyn (Eds.), Emerging trends in the social and behavioral sciences (pp. 1–15). Wiley Online: John Wiley & Sons.

- Hall, P., & Soskice, D. (2001). Varieties of Capitalism. Cambridge: Oxford University Press.

- Hanley, J. A., Negassa, A., & Forrester, J. E. (2003). Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: An orientation. American Journal of Epidemiology, 157(4), 364–375.

- Hargadon, A. (2003). How breakthroughs happen: The surprising truth about how companies innovate. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Hemerijck, A. (2017). The uses of social investment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jaffe, A. (1986). Technological opportunity and spillover of R&D: Evidence from firms’ patents, profits, and market value. American Economic Review, 76, 984–1001.

- Jaffe, A. (1989). Real effects of academic research. American Economic Review, 79, 957–970.

- Jaffe, A., Trajtenberg, M., & Fogarty, M. (2000). The meaning of patent citations: Report on the NBER/Case Western reserve survey of patentees. NBER Working Paper, 7631.

- Johnston, J., & DiNardo, J. (1997). Econometric methods. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Kleinknecht, A., & Reinders, H. J. (2012). How good are patents as innovation indicators? Evidence from Grman CIS data. In M. Andersson, B. Johansson, C. Karlsson, & H. Loof (Eds.), Innovation and growth: From R&D strategies of innovating firms to economy-wide technological change (pp. 115–127). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Koo, J. (2006). In search of new knowledge: Its origins and destinations. Economic Development Quarterly, 20, 259–277.

- Koo, J., & Cho, K. (2011). New firm formation and industry clusters: A case of the drugs industry in the U.S. Growth and Change, 42, 179–199.

- Koo, J., Yoon, G.-S., Hwang, I., & Barnerjee, S. G. (2013). A pitfall of private participation in infrastructure: A case of power service in developing countries. The American Review of Public Administration, 43(6), 674–689.

- Liang, K.-Y., & Zeger, S. L. (1986). Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika, 73(1), 13–22.

- Lindert, P. H. (2004). Growing public: Social spending and economic growth since the eighteenth century, volume I: The story. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lorenz, E. (2015). Work organisation forms of employee learning and labour market structure: Accounting for international differences in workplace innovation. Journal of Knowledge Economy, 6, 437–466.

- Lundvall, B.-A. (Ed.). (1992). National systems of innovation: Towards a theory of innovation and interactive learning. London: Pinter.

- MacLeod, G. A. (1973). Does creativity lead to happiness and more enjoyment of life? Journal of Creative Behavior, 7, 227–230.

- Maliranta, M., Mättännen, N., & Vihriälä, V. (2012). Are the Nordic countries really less innovative than the U.S.? (19 December 2012). CEPR Policy Portal. Retrieved from http://www.voxeu.org/article/nordic-innovation-cuddly-capitalism-really-less-innovative

- McKenna, J. (2017, October 12). Why does Sweden produce so many startups? World economic forum. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/10/why-does-sweden-produce-so-many-startups/

- Nussbaum, M. (2003). Capabilities as fundamental entitlements: Sen and social justice. Feminist Economics, 9, 33–59.

- OECD. (2007). The social expenditure database: An interpretative guide SOCX 1980–2003. Paris: Author.

- OECD. (2015). Frascati manual 2015:Guidelines for collecting and reporting data on research and experimental development. Paris: Author.

- OECD. (2016). Estimating Public Social Expenditure 2014/15-2016 – Sources and Methods.

- OECD. (2017). ISCED-97, Graduates by field of education.

- Onaran, O., & Stockhammer, E. (2016). Policies for wage-led growth in Europe. Policy Report-FEPS. Brussels: Foundation for European Progressive Studies.

- Page, S. (2007). The difference: How the power of diversity creates better groups, firms, schools, and societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Raffiee, J., & Feng, J. (2014). Should I quit my day job? A hybrid path to entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Journal, 57, 936–963.

- Romer, P. M. (1986). Increasing returns and long-run growth. Journal of Political Economy, 94, 1002–1037.

- Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy, 98, S71–S102.

- Ruef, M. (2002). Strong ties, weak ties and islands: Structural and cultural predictors of organizational innovation. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11, 427–449.

- Schumpeter, J. (1934). The Theory of Economic Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Schumpeter, J. (1942). Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. New York: Harper and Row.

- Schumpeter, J. (1947). The creative response in economic history. Journal of Economic History, 7, 149–159.

- Sen, A. (1980). Equality of what. In S. McMurrin (Ed.), The Tanner Lectures of Human Values (pp. 257–280). Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

- Shane, S. (2000). Prior knowledge and the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities. Organization Science, 11, 448–469.

- Storey, D. J. (1991). The birth of new firms: Does unemployment matter? A review of evidence. Small Business Economics, 3, 167–178.

- Taylor, M. Z. (2004). Empirical evidence against varieties of capitalism’s theory of technological innovation. International Organization, 58, 601–631.