ABSTRACT

Implementation in the late nineties of Transmilenio, a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) based transportation policy in Bogotá (Colombia), marked an inflection milestone for the replication processes of such urban transportation policies. Multiple actors and actions brought the Transmilenio model to numerous cities worldwide, first replicated in other Colombian and Latin American cities later it reached Turkey, China and India and then spread all over the world. This article explores the role of think tanks steering and promoting BRT policies during complexes processes and interactions of power among multiple scales. In doing so, the article situates itself within the research arenas studying linkages between local interests, demands and needs and the global neoliberal allocation of capital and expertise via consulting, advising commerce and construction activities. I argue that BRT promotion think tanks have emerged as powerful mechanisms mobilizing specific transportation policies acting as facilitators of movements via ‘policy translators’, promoters and network developers among the plethora of actors and interests. Methodology utilized is based on data from policy reports, archives and in-depth interviews exploring networked interactions while tracing linkages between think tanks and policy actors and observing knowledge dissemination arenas. This research contributes to the exploration of urban transportation epistemic communities and its role in urban change under a neoliberal global context and underlines the role of emerging policies from the south that permeate global policy arenas, traditionally dominated by actors from developed economies and discusses the mediation of global north institutions in the global south urban policy mobilities landscape.

1. Introduction

Social interdependencies have increased today to levels never previously imagined. Global connections create relations and interactions that feed off each other in a constantly growing progression. Regarding urban issues, plans, programs and policies that worked in other cities and other latitudes which were then tried elsewhere are especially worthy attention. Traditionally, operating under the modernist rational model, decision-makers focused on the search for solutions that could be applied to all times and places, regardless of unique and specific social, political and economic contexts. Along these lines, Latin American nations adopted for many decades foreign practices, mainly from Europe and the United States, in the shaping of their economies and cities.

Contemporary research has brought into question the universality of policies and plans, arguing that local realities are unique in many ways and policies and practices from other latitudes do not necessarily fit, at least not in ways they did elsewhere (Brenner, Citation2004; Dollowitz & Marsh, Citation2000; Lovell, Citation2017, Citation2019; McCann & Ward, Citation2011; Mccann, Citation2011a, Citation2011b; Porto de Oliveira and Pal, Citation2018; Rose, Citation1991; James and Lodge, Citation2003). Globalization has intensified the linkages emerging from international allocation of capital and its relationship with territorial structures that can be modified by strong external influxes while resisting according to their local fix and immobile conditions (Brenner, Citation1999). So, it is commonly accepted that global capital allocation imposes conditions to the adoption and implementation of local policies in the global south. Nonetheless, important attention comes from the global South where some urban polices have become global models to be replicated around the world (Novick, Citation2009; Jajamovich, Citation2013; Montero, Citation2017; Sosa López & Montero, Citation2018; Porto de Oliveira & Pimenta de Faria, Citation2017; Wood, Citation2014, Citation2015a, Citation2015b, Citation2016), a practice that was traditionally reserved for developed countries as exporters. So, while knowledge emanated from the South appears to have great potential to be diffused, to a certain extent, there still requires some connections and filtering of this knowledge from northern entities and actors. Here is when global actors such as think tanks emerge as facilitators of global movements of policies coming from the global South.

The implementation of a specific urban transportation policy in Bogotá (Colombia) at the beginning of the new millennium, known as Transmilenio, marked the detonation of an accelerated process of proliferation of Bus Rapid Transit systems in Colombia, then Latin America and later in other cities in Asia, Africa, North America and Europe (Levinson et al., Citation2002; Hidalgo & Huizenga, Citation2013; Sengers & Raven, Citation2015; Mejía-Dugand, Hjelm, Baas, & Ríos, Citation2013; Mallqui and Pojani, Citation2017). Transmilenio became a reference model and was explicitly used to replicate similar policies in numerous other cities. Although it was not the first Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) based urban policy in Latin America nor in the world, it marked a milestone in the proliferation of such policies because it provided a new approach and generated new knowledge in terms of operational, fare-collection and investment models that attracted countless actors. Instead of the traditionally claimed reason for the proliferation of such projects as a ‘best practice’ worthy of replication, BRT policies' movements have witnessed a complex interaction of global actors such as renowned consultants, knowledge experts, think tanks and multilateral banks with local authorities such as mayors, city councils, national executive branch officers, national government advisors among many others. As knowledge has been used as a facilitator of policy mobilities in an arena of competing power interactions, this knowledge is worthy of careful analysis; although these interactions have used professional, technical and policy knowledge as the foundation of their recommendations many of these actors have sturdy linkages with private sector actors that have modulated their relationships.

This article focuses on two specific think tanks that have played the role of ‘policy mobilizers’ in the last couple of decades: First, the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) and second, EMBARQ (part of the World Resource Institute Ross Center for Sustainable Cities and former Centro de Transporte Sostenible – CTS). Both have had a close relationship and discreet interaction with Transmilenio having used the power of its narrative to promote iterative replications of this policy coming from the South into multiple other global South locations and likewise in many cities of developed economies where bus systems have found its way over rail-based systems. In this article, I analyze different arenas where global urban transportation policy takes place by scrutinizing the dynamics and operations of these two major think tanks which can be considered relevant representatives of the global epistemic community on urban transportation policy due to their capacity to influence urban policy agendas worldwide.

Think tanks and their influence in developing cities have raised many eyebrows and attracted many criticisms (Peck & Theodore, Citation2010; Brenner & Theodore, Citation2012; Stone, Citation1996, Citation2002b, Citation2009, Citation2013, Citation2014, Citation2017; Stone and Ladi, Citation2017). Moreover, some think tanks and their claims have been deemed biased by the fact that they represented the interests of funding sources, sponsor and donors, for the case of urban transportation policy foundations of companies related to certain level with the automobile and oil industry and not necessarily deploying their recommendations purely from technical arguments. To a certain extent the two think tanks analyzed, although explicitly concerned for sustainable transportation solutions, have mainly focused on BRT systems as the only plausible solution for urban transport in the developing world arguing that this solution represents lower costs. Critics suggest such cost evaluations are not so rigorous cost and that alternative have not been seriously and meticulously analyzed (Filipe & Macário, Citation2013; Nikitas & Karlsson, Citation2015).

After many decades of local debate and knowledge exchange with the absence of policy templates, ‘solutions’ or ‘best-practices’, Bogotá came to an answer for its transportation problems and the resulting knowledge was easily packed as a policy by certain actors and moved all over the world (Ardila, Citation2004; Duarte & Rojas, Citation2012; Montero, Citation2017; Silva Ardila, Citation2016). Although the BRT concept has not been an exclusive product of Bogota, the Transmilenio model offered a comprehensive package that reduced complicated planning processes and gave international players a solid policy capable of replication in multiple locations. Thus, BRT policies are adequate illustrations of transnational policy transfers where ideas and knowledge are converted into policy templates allowing for easier replication in other places which is the proposed central discussion on this special issue. Precisely under this context, global transportation think tanks have promoted knowledge development, assemblage and package urban transportation policies and facilitate policy mobilities working as articulators of multidimensional global interests.

In this article, I present two central arguments. First, I claim that ITDP and EMBARQ have grown as global facilitators of urban policy mobilities of BRT-based urban transportation systems using similar strategies and conducting comparable actions. Both have used the model, narrative and expertise of Transmilenio to benchmark and promote the replication of similar policies in numerous cities around the world and at the same time both have used similar strategies such as awards, guidelines, standards, and the use of ‘policy mobilisers’ as advisors for consulting strategies or as speakers in promotion events such as conferences, talks or workshops. And second, I show that the process of promotion conducted by these think tanks respond to complex processes and interactions of power among multiple scales, particularly attempting to link local interests, demands and needs with the global capitalist allocation of capital and expertise via consulting, advising commerce and construction activities. These interactions result in strong relations with industries related and in proximity with the mobilized policy such as oil-based vehicles manufacture, combustible companies or financial institutions among others.

Using documents, reports, archives and digital information mixed with a set of more than forty in-depth interviews I have been able to trace the most relevant linkages of these think tanks in terms of knowledge dissemination and specific direct interactions. As a case-specific application of the ‘follow the policy’ strategies (Peck & Theodore, Citation2012) the methods enrich the conversation on forms and mechanisms of observing trajectories, epistemic communities and linkages within the movement of ideas framed as policy templates. In order to understand the exchange mechanisms and map the actors and their relations, I developed a multi-scalar and multi-sphere analytical framework that includes three theoretical territorial scales (local, national and global) and crosses them with three theoretical spheres of interaction (production, knowledge and financing). As a result, I have been able to trace linkages, connections and partnerships between multiple global actors with these think tanks understanding their role in the global allocation of ideas and policies in and environment of local demands for solutions. These extreme arenas interact with the national context, which functions as a mediator, posing interesting questions on the process of ‘domestication’ of a policy within different social, political and economic contexts.

The paper is structured as follows. First, I discuss the general framework of the analysis locating this article within the conversation of policy transfers, diffusions and mobilities. Additionally, I briefly present the broader discussion on neoliberal urbanism within contemporary capitalism where this article can be situated as part of the body of a broader discussion. Then, I describe the national BRT development for Bogotá and trace its trajectory to other Colombia and Latin American cities and then the international permeation of the narrative and the policy implementation worldwide mediated by experts, consultants, and most importantly the analyzed think-tanks. Then, a section devoted to the scrutiny of the role of ITDP and EMBARQ as BRT promotion think tanks will describe the convergent strategies and the mechanisms used to facilitate mobilities from the actions and activities of think tanks. Finally, I will present some concluding remarks and will establish a conversation with the contemporary literature on policy mobility and frame the results with some theoretical debates emerging from the Transfers/Diffusion/Circulation/Mobility scholarship. Observing the case of BRT promotion think tanks will primarily open the conversation of the role of mediation that northern mobilizers play within the mobilities of south urban policies, specifically if there is a need of global north consent and arbitration in order to spread the ideas within global epistemic communities or if in fact with are facing the emergence of novel form of interactions of global south policy agents.

2. Global attractiveness of urban policies and methods for its exploration

Transformations happening in urban scenarios are spatial materializations of power territorialities and imply power relations along multiple scales serving multiple specific interests (Allen & Cochrane, Citation2007; Brenner, Citation1999, Citation2004; Robinson, Citation2011; Jajamovich, Citation2018a). These processes, sometimes framed as policies, involve a wide range of agents interacting around an issue and gravitating on a topic that serves each one’s own agenda that converge in this effort. Ideas and knowledge are fundamental to the process of policy development and require the existence of multiple capacities to emerge within a specific territorial arrangement. Although knowledge is generated in multiple spaces, actors playing at the global scale present a major role in the development and consolidation of knowledge networks that promote and disseminate urban policies via conferences, experts’ visits, professional and technical consulting, business and investment plans.

Power relations emerging from urban policy mobilities modify, in the end, the material form of cities but also alter the forms of policy-making while changing local economic dynamics. In his theory of epistemic communities, Haas (Citation2015, p. 85) affirms that, ‘members of a prevailing community become strong actors at the national and transnational level as decision-makers solicit their information and delegate responsibility to them; to the extent to which an epistemic community consolidates bureaucratic power within national administrations and international secretariats, it stands to institutionalize and insinuate its views into broader international politics’. Therefore, these emerging power mechanisms can be considered as techniques that serve and allow for the expansion of capital under neoliberal approaches of spatial change. So this conversation deals with the role of novel agents on neoliberal landscapes of global capital allocation, while urban policy may be assumed as extremely fixed process global actions show that there are growing interests in facilitating the allocation of capital into local policies as irrigation expansion of capital allocation, with a particular interest in public services.

Knowledge-and expertise-based global agents, in turn, develop relationships with other international and global actors such as banks and multinational industrial corporations that are interested in expanding their markets, while offering comprehensive solutions that address the what and the how of the policy (Stone, Citation2002a, Citation2015, Citation2017; Stone & Ladi, Citation2015, Citation2017). Thus, they can facilitate access to resources that local authorities normally consider difficult to get. Think tanks are crucial organizational platforms that can link international agents with national and local policymakers, matching interests that may constitute conscious strategies to find better options when solving local problems.

The links and mobilities promoted by international actors may also be part of a complex framework proposed or imposed by powerful agents using a wide range of strategies, from voluntary to coercive in the process of policy mobilities (Benson & Jordan, Citation2011; Bok & Coe, Citation2017; Evans, Citation2009). The observation of these power mechanisms relates to one of the question of why somebody that does not know much about a specific local context allocates millions of dollars to implement certain local policy. An interviewedFootnote1 global actor based on a multilateral bank affirm that ‘think tanks help to understand local contexts and provide answers to the questions that we already know we will not have time or resources to answer, but we know there are investment opportunities that we might overlook’. So, capital allocation has become a technique to assure that power serves interests of powerful agents from a productive sphere. This insight implies that although there is not an explicit exercise of coercive power, there are powers in place and actively interacting when policy mobilities allow the allocation of resources in different milieus.

Urban policy mobilities resulting from the circulation of ideas that are accepted and already tested in one place and then packed and used to replicate specific policies to another place, can be assumed to be a sturdy technique of power. It is a technique that uses knowledge as a strategy to support but also to convince agents to follow the proposed actions. It is where epistemic communities and knowledge networks – such as those of think tanks or thematic experts – become relevant and key subjects of study. In this area of scrutiny, Diane Stone (Citation2001, Citation2008, Citation2013, Citation2014, Citation2015, Citation2017) focuses on globalization, transnational policy and the role of think tanks and provides a general framework to understand the existing interests of think tanks of policy diffusion. So, Stone (Citation2000, p. 45) argues that ‘the importance of think tanks to policy transfer is their ability to diffuse ideas by (1) acting as a clearinghouse for information, (2) their involvement in the advocacy of ideas, (3) their involvement in domestic and transnational policy networks, and (4) their intellectual and scholarly base providing expertise on specialized policy issues.’ Additionally, Stone identifies a reinforcing dynamic between think tanks and policy transfers; in this sense, while think tanks have supported the increase of policy transfers, their concurrent proliferation can be understood as an indicator of the acceleration of policy transfers in the context of globalization.

The myriad of existing think tanks is a suggestion of the proliferation of multiple epistemic communities that advocate for specific topics, agendas and interests. Many think tanks focus on global agendas and implement them on the global scenarios, others focus on attempting to persuade national governments or companies to adopt their ideas or knowledge while others have found their niche in the scouting process of ‘successful’ urban polices that will be capable of reproduction in other milieu. An interviewee from an international organization said ‘sometimes we have broad agendas and think tanks have already walked the path of specific topics. We consider think tanks great allies when in need of specialization in topics and issues’. As part of this specialization process and its direct interaction with specific urban policy implementation, I have found in the case of BRT proliferation in Latin American cities and later in the rest of the world a pertinent research arena for the exploration of epistemic communities, particularly from the narrative promotion and the process of displaying the policy as a ‘best practice’ to finally packaging the policy and implementing it several locations. This case study of BRT speaks to the observation and analysis of the increasing policy transfers emanating from the South in an arena traditionally dominated by policies and practices that are disseminated from developed countries.

2.1. The methodological challenge

Given the complexity of this effort, this inquiry required the use of various methodological strategies in order to track processes that are not easily observed. I opted for the ‘follow the policy,’ distended-case study approach proposed by Peck and Theodore (Citation2012), because it permits in-depth observation while exploring wider networks and accompanying circumstances along with the relations taking place among the agents involved in the process. As the name indicates, the ‘follow the policy’ method (Peck & Theodore, Citation2012) traces the process taking place as the policy moves while observing its possible modifications through the scales, agents and relationships that shape it and the process as it moves from one location to another, from one context to another, from one political economy to another.

As Peck and Theodore (Citation2012, p. 26) suggested, ‘a judicious combination of observations, documentary analysis, and in-depth interviews as a means of probing, interrogating, and triangulating issues around the functioning of global policy networks, the reconstruction of policy models, and the adaptation of policy practice – spanning an expansive “causal group” of policy actors, advocates, and critics’. In this way, this method tries to capture the fluidity and possibly transformative process taking place as policies move and the role of the numerous actors. It also aims to explain the extent to which policy mobilities can be contained in single explanations or, rather, call for a flexible and complex methodology that can capture what remains and what changes in the process.

First, I traced the trajectory of the policy, starting in Bogotá and tracing back former BRT policies in the region that influenced Transmilenio and the regional urban transportation debate. Later I traced the trajectory after Transmilenio and identified the expansion in Latin America and then in the rest of the world. After identifying the policy trajectory, I mapped actors and created a schematic model of interactions that facilitated the archival research for documents, reports, articles, among other digital sources. Then, I conducted roughly forty in-depth interviews covering each of the dimensions, scales and actors which allowed me for triangulation, snowballing and organization of narratives of the informants.

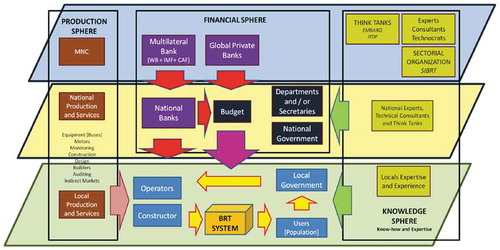

In order to organize and guide the methodological exploration, agents were theoretically categorized by scales and spheres (as seen in ) under the assumption that policy mobilities may involve an intricate set of actors arranged on three main theoretical scales where the BRT system’s implementation process took place: the local (the lower level), the national, and the global (the higher level). It is important to recognize that this scheme is not a representation of reality but a methodological tool used to map the relevant actors, categorize them and use as an indicator of the arenas where I needed to find actors to interview and be capable of gathering information to construct coherent database out of the reported information.

At the local level, there is the ‘material implementation’ of the policy. This is what I like to call the artefacto and is represented by the blue actors in , which is the policy in its definite configuration: that is, it is the BRT system itself composed by the relations between the users, operators, constructors, local government. Then, I proposed three analytical dimensions that directly and indirectly affect the material implementation of the policy and are represented by the thick line boxes as seen in : (1) a production dimension related to the goods and services needed for the construction and running of the project such as motor fabricants, bus parts distributors, construction companies, fare collection technologies, sliding doors companies, among multiple others, (2) a financial dimension that encompasses all actors related with the allocation of resources such government resources and funding agencies, multilateral bank that provide loans or capital investments within a complex institutional infrastructure, and (3) a knowledge dimension where ideas are exchanged on the basis of ideologies, expertise and accounts of actors that directly influenced the process, urban public transportation institutional arrangements, urban project design, and implementation. Each dimension (sphere) is characterized by different actors as well as at each scale and I have tried to map certain level of interactions and relations within the policy arena.

For this paper a comprehensive understanding and discussion of the policy arena scheme is not a priority because I have focused on the exploration of the agents situated at the knowledge sphere within the global scale, where think tanks, experts and epistemic communities predominantly operate. Nonetheless, some arguments within the paper will point the spheres and scales in order to locate the arena where interactions where happening but mainly as a methodological instrument where they were detected during the data collection process. Although these scales and spheres are schematically segregated on the diagram for theoretical purposes, they intermingle/overlap on an intricated and complex set of relations that make it hard to distinguish clear boundaries and limits as a result of the complexity of social and policy arenas. Most of this research effort consisted of carefully observing how they are articulated, how they relate, and how they get transformed during the implementation of the program.

3. A replicable global model emerging from a local urban transportation policy

The idea of implementing a comprehensive and integrated urban transportation system based on buses for Bogotá had been discussed profoundly for more than four decades (Ardila, Citation2004; Hermann & Hidalgo, Citation2004; Jara-Moreno, Citation2012; Suzuki, Cervero, & Iuchi, Citation2013; Wright & Hook, Citation2007). Ideas fluctuated from metro systems to bus systems and the debate on these schemes was closely related to electoral cycles. Although some projects and policies were implemented, there were no fully effective solutions put in place. Most actions that had been implemented were unsuccessful, but by the end of the nineties the context seemed slightly different. The city, as a result of fiscal decentralization and a reduction of corrupt practices marked by the previous two governments, had enough resources to invest in urban infrastructure. The debate about the metro system had been shelved due to the lack of national resources (Colombian law establishes a cap of 70% national participation and 30% local in mass transportation investments) and the new mayor was ready to implement the BRT idea after he promoted a metro line that was declined after the national economy entered its most deep economic crisis in the second half of the twentieth century.

Since the mid-seventies, Bogotá attempted to implement a transportation policy and there is multiple evidence of observation and explorations of other cases in other cities in the world. I have been able to track back the knowledge discussion to the moment when Álvaro Pachón, an urban expert consultant translated John Kain (Citation1975) article and published it at Universidad Nacional de Colombia Economics Department Magazine. Later there were years of knowledge exchange with Companhia de Engenharia de Trafego from Sao Paulo and the idea of segregated lanes for buses was modeled according to the example of Brigadeiro Project in Brasil, but it was never successful in Colombia.

In the mid-nineties Bogotá had a major transportation plan (Japanese International Cooperation Agency [JICA], Citation1996) written with the help of the Japanese International Cooperation Agency – JICA – which included a mature design for a future BRT system in the city, along with many other transportation elements such as a new operational system for bus service in the city, bike networks, a progressive mass transportation investment program to satisfy the city growth that would have required rail transportation investment and highway expansion program. By 1998, the moment when the metro idea was abandoned, Curitiba, Brazil was already a successful story and the experience was analyzed by Bogotá’s mayor Enrique Peñalosa’s team. Additionally, his team explored the experiences of Sao Paulo and invited Brazilian experts to help them. A transportation research center – known as SER – had previously observed and studied the case of Curitiba and most of that knowledge was included in the emerging new projects (Ardila, Citation2004). On top of the Brazilian exchanges, Quito, Ecuador was included in the observed cases, where Mayor Cesar Arias had engaged in a bare-bones experience of the BRT approach. After multiple knowledge exchanges and technical work that derived in the solution and adaptation for the local conditions, running December 2000, Transmilenio was inaugurated and symbolically presented as a solution for the new Millennium. Within months, the number of users rose at an exponential rate and its subsequent expansion was a reflection of its success.

The project’s scale, planning, resources, and expectations were humble. Transmilenio was designed with a strong sense of discretion, although the expected outcome was ambitious in hoping for a comprehensive and integrated transport system to follow. Transmilenio became a demonstrative case for transport experts (Pochet et al., Citation2006; Montero, Citation2017a, Citation2017b). First, the capacity of Transmilenio surprised the engineering world when a bus-based system reached levels of passenger measurements only previously reached by metro systems. Second, a semi-comprehensive and successful BRT system applied for the first time in a large urban agglomeration with more than 5 million inhabitants now existed. Users felt immediately the benefits that came from the service improvement of quality and reductions in their commuting times while private companies felt they had done good business, reflected in their profits.

The actual numbers of users started to surpass expectations. In particular, Avenida Caracas – an arterial road in Bogotá that runs through the city from north to south – became a ‘world marvel’ when surpassing the technically and academically well-known statistic of 40,000 thousand passengers per hour on one-way, doubling from the expected capacity of 20,000. Multiple transport academics and experts (Suzuki et al., Citation2013; Wright & Hook, Citation2007) saw TRASMILENIO as an interesting case study and policy lesson that was going to be able to compete with railway technologies in terms of capacity and, at the same time, cost a fraction to implement when compared to railway investment. By the same token, the engineering world wanted to know how to achieve such an outcome.

On November 8th, 2006, Bogotá was awarded the Leone d’Oro per le Città during the Biennale di Venezia. The 10th Mostra Internazionale di Architettura at the Corderie dell’Arsenale, curated by Richard Burdett, included presentations on the urban experiences of 16 cities (New York, Los Angeles, Ciudad de México, Johannesburg, Berlin, Caracas, São Paulo, Tokyo, Shanghai, Cairo, Bombay, Istanbul, Barcelona, Milano, Torino, and Bogotá). The transformation of Bogotá presented on the exhibition ‘El Renacer de una Ciudad’ (The Rebirth of a City) was recognized as a significant experience for poor and rich cities all over the world and was referenced as an important and integral form of urban change.

The Leone d’Oro per le Città may be, symbolically, understood as the result of a long-term process of political, economic, and social change in Colombia, and specifically in Bogotá. Investments on radical transformations, renovation and construction of public spaces, revitalization of education infrastructure, and improvement of the public libraries’ system, social inclusion and civic culture programs, creation of a comprehensive bike network, security and safety initiatives, among other projects were recognized as exemplary. One of the multiple projects presented as a component of the urban strategy of Bogotá’s transformation was Transmilenio, a mass transportation system, using a specific technology known as a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) that radically changed urban transport in the city. Although this urban mass transport policy was not the only successful one, it was the only one that travelled rapidly and steadily throughout the world.

BRT systems, with Transmilenio as the example, became an innovative and relevant option for fast-growing cities in the developing world; its technical peculiarities also made it interesting and pertinent for several cities in developed countries. The success was explained by incorporated innovations, namely the surpass lanes at stations that allowed for the development of express routes and the implementation of access cards and its GPS location and monitoring systems. It also quickly caught the attention of petrol operated bus manufactures who could take the success of Transmilenio and similar schemes as new evidence for the social and economic potency of their product. As noted in the production sphere plays a central role in the feasibility of the policy and in this case Transmilenio was a verified model to replicate, and it held promise for numerous new markets to generate.

Once a policy has been properly implemented in a place, and many attributes can be presented as positive at the same time that it matches specific interests of stakeholders (such, profits, esthetic attributes, and social impact), there is a great incentive to mobilize it to other places. The urban mobilities body of literature (Mccann, Citation2011; McCann & Ward, Citation2010, Citation2012); Harris & Moore, Citation2013; Peck & Theodore, Citation2010) highlights the process of consolidation of a policy and its subsequent process of benchmarking as a requirement for movement from one place to another. Transmilenio was able to generate enough incentives for the private sector to participate investing resources in urban policies, the public sector to focus on transportation issues, the financial institutions to fund it, and various other incentives for other key actors. But probably one of the most important impacts of Transmilenio was the fact that it generated a new set of actors that would disseminate the story and promote BRT along with the innovations taking place in Bogota around the globe, and most important in this constellation were think tanks. Many Colombians became ‘transportation experts’ and were hired by countries and cities as advisors and called by the multilateral bank to help to promote their investments interest. Many Colombians ended-up working in the World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank or advising Mexican, Peruvian, Chilean cites in the aftermath of Transmilenio implementation. So this set of actors, as noted in , mainly located at the national scale on the knowledge sphere, on one side played a central role in policy dissemination worldwide and some years later on the other hand had negative consequences when reducing the availability of expertise for the implementation of the Colombian BRT Program some years later generating technical local challenges.

In parallel, the experience of many policymakers and actors involved in Transmilenio would lead to the reconfiguration of think tanks that formalized and defended the public transportation policies and practices but now clearly promoting BRT systems as the solution to replicate all over the world. Think tanks became key actors for ensuing explosion of mass urban transport projects based on BRT around the world, first in Latin America, later in Asia and Africa, and then in the United States (to a certain extent as a novelty, despite the fact that some ideas and projects of this sort had been implemented at the beginning of the 20th century) and in Europe (where bus systems were redesigned and improved through the agency of the new technological capacities developed by the bus industry in Latin America and Asia). Among these think tanks, ITDP and EMBARK are two of the most prominent.

4. Think tanks spreading the idea around the globe

Briefly, this section describes the consolidation process of each think tank and then discusses the different mobility strategies used by them to promote BRT systems worldwide. Although emerging from different sets of interests both think tanks share goals and in the long run started sharing action arenas promoting similar dialogues worldwide. Strategies such as awards, guidelines, conferences, consultancy, support for incubator of sectoral initiatives became the most recognized actions. Additionally, each think tank attempted to create and strengthen their own policy networks in order to be capable of influencing the urban transportation landscapes of the countries where the policy was attempted to be implemented. First, let us look at the development process of each think tank.

4.1. Think tank presentation

4.1.1. The institute for transportation and development policy

The Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) was created in 1985 by Michael Replogle as an ‘umbrella organization for several worldwide peace and development initiatives and advocacy efforts.’ (Institute for Transportation and Development Policy [ITDP], Citation2018) Today ITDP is an organization concerned with urban transport policies particularly those reducing car dependence through non-motorized modes and BRT systems and is mainly funded by the Climate Works Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Hewlett Foundation. For many years, ITDP proposed multiple strategies in the developing world with no success but it was after Transmilenio’s accomplishment that the organization became a relevant worldwide actor. Once Enrique Peñalosa finished his term as Bogotá’s mayor, he moved to New York City and became a transportation consultant and lecturer in multiple scenarios. Knowledge and experience became the key attributes Peñalosa was capable of diffusing to many audiences.

As acknowledged by ITDP, Transmilenio was highly relevant in the history of this think tank that claimed that it had influenced the system’s design through by ITDP papers. ITDP became a policy diffuser and focus its efforts in inspiring the spread of BRT globally and promoting and providing technical support for those BRT projects. As stated by ITDP in 2001, ‘building off Transmilenio’s success, ITDP sponsors and organizes workshops and presentations on Bus Rapid Transit in over 15 cities, winning support for BRT projects in many and laying the groundwork for future projects.’ (ITDP, Citation2018)

4.1.2. EMBARQ

EMBARQ, an initiative located in Washington D.C. with branch offices in Mexico, Brazil, Turkey, India, and China that promotes implementation of BRT systems in large urban agglomerations. EMBARQ is supported by the World Resource Institute (WRI) and its name has mutated multiple times as so its location within the institute. Initially funded the Center for Sustainable Transport (CTS) in Mexico and Brazil, aiming to reduce gas emissions in the world. CTS strategy was later enhanced in order to expand world-wide and it was renamed EMBARQ. Once Transmilenio became a reference example of the BRT system, it was also presented as an efficient way of investing resources and improving the quality of urban transportation while reducing urban CO2 emissions.

WRI was attracted to BRT policy and with the CTS initiative promoted the creation of a global network of policy promotion that was later organized under the umbrella of EMBARQ and currently again reorganized as a subprogram of the WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

4.2. The role of recognized experts or policy mobilizers

Both cases present an interest reinvigorating process of their actions, activities and interests with the inclusion of key figures of BRT experiences. On the ITDP side, the success story of Transmilenio together with Peñalosa’s charisma and the fact that he was living in New York were sufficient arguments for ITDP’s CEO, Walter Hook, to invite Peñalosa to become a member of ITDP’s Board of Directors where he was its president for many years. Later Jaime Lerner, former mayor of Curitiba became a key ally of the narrative promotion from ITDP and a similar to Peñalosa could claim: ‘I did it’, in order to encourage other local governments to pursue the implementation. In parallel, EMBARQ received and hired multiple relevant BRT policy actors such as Dario Hidalgo, who was during Peñalosa’s administration project director for a Metro Company in Bogotá (1998–2000) and Deputy Director of Transmilenio (2000–2003). Dario Hidalgo, as EMBARQ’s Director of Integrated Transport, along with multiple key policy mobilizers in CTS and later EMBARQ in Mexico, Turkey, India and China have played a crucial role in the process of mobilizing BRT policies all over the globe. He, for instance, became a key actor promoting the experience of Bogotá via EMBARQ and together with multiple Colombian experts became part of various Latin American initiatives (Deng & Nelson, Citation2013; Díaz Del Castillo, Sarmiento, Reis, & Brownson, Citation2011; Froschauer, Citation2010)

The personification of the policy implementation process, via policy mobilizers, is a crucial strategy for think tanks and have helped them to establish a more human connection with potential local authorities interested in BRT policies (Larner and Laurie, Citation2010). Policymakers such as Enrique Peñalosa and Jaime Lerner became key promoters as former mayors of cities that successfully implemented the basic idea. They have been important and necessary to convince other decision-makers elsewhere in Latin America and the world to implement the project. The policy mobilizer has the capacity to strengthen the narrative, becomes the instrument to communicate and promote the benefits but also the challenges faced by such a project and establish links that will identify the action spheres and dimensions where think tanks can deploy their capacities. Policy mobilizers play a crucial role in facilitating policy mobility process and are central actors of the goals and interests of each think tank.

4.3. Awards, recognitions and awareness

As part of the emerging relationship between Bogotá’s Transmilenio and ITDP, in 2005, the think tank created the Sustainable Transport Award and Bogota’s Transmilenio was the first award recipient. The award emphasizes the necessity to promote the model as a relevant ‘best practice’ and made it replicable when framed as a replicable and movable example. Similarly, WRI has launched the Ross Prize for Cities collecting successful experiences and promoting winners as benchmarking policies that may be prone to be replicable in other locations. While ITDP awards have been focused towards transportation issues WRI has broadened the spectrum of topics, both cases reflect the impact of these strategies as awareness mechanisms.

Recognitions are crucial into the narrative of successful stories and ‘best practices’. An urban public policy ‘that has received an award is more likely to be replicated by others. The prizes become a tool for illustrations and recognition of what is going on in other places and create a kind of policy market’ reported a policymaker working for the Colombian national strategy.

4.4. Guidelines, standards and consulting services

In 2007 ITDP published The BRT Planning Guide, based on Transmilenio’s experience (Wright & Hook, Citation2007). Through this Planning Guide, ITDP’s diffusion efforts influenced the implementation of BRT in Johannesburg in South Africa; Pune, Indore, Jaipur, Bhopal and Ahmedabad in India; Lanzhou in China; México City, and Rio de Janeiro. Once diffusion was done, multiple projects emerged such as those in Guangzhou, China, and Dar es Salaam, in Tanzania, partly funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and which were later awarded with the prize. In this way, ITDP became a world reference in BRT systems, promoting multiple projects and growing exponentially. Additionally, together with the German Cooperation Agency, ITDP has published a couple of versions of BRT Implementation Guidelines and provided knowledge to the development of excellence standards of BRT systems.

EMBARQ grew parallel to the expansion of Transmilenio’s network of expertise and has been able to convince multiple cities around the globe to implement Bogota-inspired systems via consulting services and providing knowledge advice. Mexico and Brazil became main hubs of the network in Latin America and the implementation of the BRT of Istanbul allowed the consolidation of a branch office in Turkey, which then allowed for a later expansion to India and China. EMBARQ is a great example of a different kind of strategic behavior towards knowledge diffusion and expansion via regionalization and the location of the regional headquarters in countries large enough to support not only multiple replications of BRT but also to influence its neighboring countries (Hidalgo & Huizenga, Citation2013; Hidalgo & King, Citation2014; Rizvi and Sclar, Citation2014; Nakamura et al., Citation2017). EMBARQ’s network has targeted BRICS countries, excluding Russia, and similar countries such as Mexico and Turkey. The actions of EMBARQ have centered on identification and allocation of experts, studies, technical documents, media education, and benchmarking as policy diffusers focused in promoting systems around the world.

4.5. Direct promotion and intervention in policy development

ITDP has been actively involved in the process of convincing policymakers to implement BRT policies. Once ITDP identifies that a city might have similar problems as the ones faced by Bogotá in the past, they encourage authorities to visit the city in order to promote its replication. An ITDP employee reported the following: ‘Did you know that Guangzhou’s government decided to implement a BRT after visiting Bogotá’ and he answered the question, why did they visit Bogotá? as straightforward as ‘because we convinced them to go and we brought them there’. This shows the crucial role of think tanks as a strong and proactive policy broker advocating the ‘solution reference’ and by identifying and connecting to new areas of local demand.

ITDP exemplifies the ways in which policies are labeled as ‘best practices’ after their implementation and then promoted, transferred, diffused, and adapted by think tanks. To certain extent ITDP and its relationship not only with Transmilenio but also with the ‘policy mobilizer’ Enrique Peñalosa demonstrates that the mechanisms through which a South policy moves from its local environment towards world-wide travel and transmission responds to the filter and dynamics that a global think tank can stamp on it. ITDP also exemplifies how best practices are used by global infrastructures to multiply an idea in multiple areas. Nonetheless, the Transmilenio case runs counter with the current directionality; as former ITDP CEO Walter Hook stated about ITDP, ‘mostly what we do is just collect best practices from Europe and we bring them to developing countries’, but this was not the case with Transmilenio.

In both cases, the most common quoted ‘best practice’ model and benchmarking project have been Bogota’s Transmilenio, making it and Colombia’s expertise major forces in the multiplication of BRT systems. Although the BRT concept has not been the exclusive product of Bogota, the approach of Transmilenio turned it into a model for replication where key actors acknowledged the need to adjust the model to other environments. Transmilenio offered a comprehensive package that saved others many headaches and gave them a solid guidance in policy design.

Think tanks, in this case, transportation-focused think tanks, have helped to promote urban policies, to articulate multiple interests and place them together in a package that allows for easier mobility and replication in other places. Primarily promoting technical knowledge, and policy implementation processes have become the comparative advantage of BRT promotion think tanks. The generation and consolidation of knowledge networks are one of their principal attributes and as a former Transmilenio advisor stated, ‘they know the experts and are able to contact and contract them in order to expedite designs and technical studies’. They are depositories of the knowledge gained in the last 15 years; in this way, they guarantee to a certain extent the technical attributes of the project will reach a high level of quality. Think tanks are able to keep track of what is happening in the world and echo the outcomes worldwide; in this sense, they accumulate, facilitate, and disseminate knowledge among policymakers involved in BRT systems.

5. Conclusions

Transmilenio is a great illustration of a locally born initiative that achieved a global dimension facilitated by new communication technologies and international interdependencies that connect the production, financial and knowledge spheres with the transit of mobile polices. It illustrates the influential role of policy mobilizers in this outcome, most particularly in the production of what could be called a global industry of public transit. This article revealed how this success narrative can turn global via think tanks as template policy which is packaged and mobilized increasing the feasibility and profitability likelihood of projects in different contexts. While Transmilenio was the product of a long-term journey of exchanges, trial and error, local debates, and policy implementation, the policy industry marketing the actual outcome and trying to force BRT systems everywhere failed to acknowledge the complexities of policy mobilities and the critical importance of embedding for their success. Transmilenio exemplifies the complex process of policy ‘fit’ and tailoring coming from the global south that can be modulated by global think tanks in the global north.

This exploration points to the need to turn away from simplistic ‘best practice’ recipes. The soft factors of success associated with complex local processes should be researched carefully. The central question for BRT systems is the extent to which the recipe was possibly oversold or the extent to which different local experiences inform a process of policy mobility that transports the idea but needs to embed it in each specific context. As it appears, BRT is no panacea but it can be a critical component of a system that synchronizes different models of development within an integrated urban transport. Nonetheless, the focus of this inquiry was not to evaluate the impact of the policy but to understand the role of certain actors in the policy mobility process. Now that BRT has been tried in different contexts and scales and in smaller and larger cities, researchers can examine the extent to which it can contribute to different arrangements and types of cities.

In this sense, policy mobilities allow the practice of power, whereby mobility becomes, in some cases, a mechanism which at the same time controls social agents up to their finest details, returns value to capital investments, and transforms economic relations among involved agents. The result matches what Foucault (Citation1985, p. 178) defined as ‘the dissemination of micro-powers, a dispersed network of apparatuses without a single organizing system, center or focus, a transverse coordination of disparate institutions and technologies.’ Emergent agents in the global south can provide knowledge and expertise but require the strong power interactions of other global actors, in this case think tanks, that facilitate their capacity to interact with other locations.

Members of epistemic communities act on a specific local and national context but also diffuse their ideas through exchanges with their colleagues in ‘scientific bodies and other international organizations, during conferences, and via publications and other methods of exchanging lessons and information’ (Haas, Citation2015, p. 379) and emerging power networks are able to transfer and mobilize their discourses into other spaces. BRT, understood as a specific transport technology, is a good example of the consolidation of an epistemic community of think tanks and technical experts that cohered around the consensual knowledge of bus-based systems as efficient, easy to implement and cheaper than other options and which gained the patronage of key international organizations like the World Bank, Inter-American Development Bank, CAF and others, as identified on in the financial sphere on the global scale.

Interestingly is the fact that in some cases outcomes were not as expected and were not necessarily adequately presented into the global debate, and in many cases almost forgotten. Results in cities in Mexico, Chile, Perú and Brazil were not as successful as the reference models. Many cities presented problems of implementations due to the lack of local capacity, designs based on assumptions of the ‘success stories’ rather than local forecasts and the complications of bringing packaged financial, administrative and operational policies that not necessarily respond and adjust to the local contexts. The case of Lima in Perú is a good example of the lack of coordination with local actors and the BRT became the perfect argument to reject BRT initiatives and signified the acceptance of Metro system as the mobility priority for the city (Lindau, Hidalgo, & de Almeida Lobo, Citation2014). Similar outcomes happened in Delhi and in Santiago de Chile where BRT system implementation attempts failed when competing with other options and the lack of local adjustments meant certain levels of inflexibility whereby the BRT model was made incapable of responding to specific demands or attributes of the local context.

This paper has presented the role ITDP and EMBARQ have played in the mobility of BRT policy within Latin America and other parts of the world (mainly Asia and Africa). Indeed, both have emerged as commanding centers for the BRT policy operating, as clearinghouses for information (Stone, Citation2000) and as advocates of BRT projects and programs. Involved in domestic and transnational policy networks, they have been bringing together the multiple concerns involved in the design and implementation of the BRT policy and providing expertise on its various aspects. Both have developed projects inspired by Transmilenio in places such as Guangzhou, China, and Istanbul, Turkey that have been replicated in other cities within a certain degree of proximity to the initial BRT project city.

At the same time, however, think tanks may be tied to concerns more interested in selling the system than in examining carefully the possibilities and limitations of the policy. Hence, there is a need to examine them and other parties involved in the discussion and diffusion of policy packages such as BRT from a critical perspective, exploring the extent to which they do, or do not, operate as disinterested nodes of ideas interchange. As shown, official documents, reports, conferences, meetings, reports, and multiple other sources can provide information to study the role of these think tanks in promoting and mobilizing the BRT policy. Similar inquiries can examine political agendas such as the expansion of Transmilenio to other cities of Colombia and the issues associated with transnational firms and concerns more interested in selling a product than a solution.

The conversation that emerges from this research can be set on the role of the global south in the policy mobility landscape, both in the global urban policy practice and on the theory development. On the first hand there is strong evidence that ideas from the global south move globally and react to the global capital allocation dynamics under a neoliberal scheme but at the same time questions arise in terms of the forms and mechanisms of articulation of the global south with this flows (Jajamovich, Citation2016, Citation2018b). Is it possible that global south policies move autonomously on the global network or does it require the modulation of global north institutions such as think tanks? To what extent are global south policies interesting due to outcomes or are they relevant as facilitator of global north institutions penetration into other capital markets in the global south?

On the other hand, this article proposes a conversation with the theoretical development on policy mobilities providing some insights into the mechanisms used by think tanks to promote global south policies and the interactions that emerge between technical and political agents of policy mobilities. Additionally, there is a proposal on methodological tools that might enrich the conversation on how scholars can explore the trajectory of mobile policies attempting to gather information that is hard to identify and process. The schematic relational model presented in proposed an analytical instrument to identify sets of agents involved in the policymaking process and was used to select the groups of interviewees that will provide information when tracing the policy and gathering historical information. The core of the diagram focuses on the policy outcome, as mentioned before ‘the artefacto’ for the case of the BRT analysis, but the rest of the graph portraits other constitutive elements of the policymaking process that sometimes are overlooked or simply forgotten that are active elements of the policymaking process. So, the production sphere, at local, national and global scales, required attention as the arena of the material economic incentives where industrial and commercial actors play a relevant role in policy development. Furthermore, the financial sphere, as noted in , provides great information on the role of multilateral organizations, national governments and financial institutions in policy implementation and shed information on the complex interactions within the monetary flows in current neoliberal arrangements. Finally, the knowledge sphere, which was the focus of this article, becomes an interesting field of research as facilitator of the movement of ideas and construction of narratives that support policies' mobilities. This proposed methodological instrument allows to enrich the process of policy tracing, document research and in-depth interviews organization during the preparation stages of the inquiry and provide a schematic framework to organize the arguments in the moment of information organization, analysis, and synthesis process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Diego Silva Ardila

Diego Silva Ardila Economist and Historian (Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia) with master’s degree on Economics and Masters in Political and International Affairs. PhD in Urban Planning and Policy at University of Illinois at Chicago with interests in urban economics, public and collective allocation of goods and services in urban spaces. Research interests in urban policy mobilities, metropolitan governance and urban history. Former Deputy Director of the Colombian National Statistical Office (DANE) and Board President of the Colombian National Geographic Institute (IGAC). Consultant for UN-Habitat, Inter-American Development Bank, CEPEI (Policy Think-Tank). Professor and Researcher at the Urban Management and Development Program at Universidad del Rosario in Bogotá, Colombia.

Notes

1 Interviewees are anonymized as part of the research protocol and disclosure agreed with them during the information gathering stage.

References

- Allen, J., & Cochrane, A. (2007). Beyond the territorial fix: Regional assemblages, politics and power. Regional Studies, 41(9), 1161–1175.

- Ardila, A. (2004). Transit planning in Curitiba and Bogotá, roles in interaction, risk, and change (Dissertation) (Vol. 201). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Dept. of Urban Studies and Planning.

- Benson, D., & Jordan, A. (2011). What have we learned from policy transfer research? Dolowitz and Marsh revisited. Political Studies Review, 9(3), 366–378.

- Bok, R., & Coe, N. M. (2017). Geographies of policy knowledge: The state and corporate dimensions of contemporary policy mobilities. Cities, 63, 51–57.

- Brenner, N. (1999). Globalisation as reterritorialisation: The re-scaling of urban governance in the European Union. Urban Studies, 36(3), 431–451.

- Brenner, N. (2004). New state spaces: Urban governance and the rescaling of statehood. Catalogue. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://ideas.repec.org/b/oxp/obooks/9780199270064.html

- Brenner, N., & Theodore, N. (2012). Spaces of neoliberalism: Urban restructuring in North America and Western Europe. Spaces of Neoliberalism: Urban Restructuring in North America and Western Europe. doi:10.1002/9781444397499

- Deng, T., & Nelson, J. D. (2013). Bus Rapid Transit implementation in Beijing: An evaluation of performance and impacts. Research in Transportation Economics, 39(1), 108–113.

- Díaz Del Castillo, A., Sarmiento, O. L., Reis, R. S., & Brownson, R. C. (2011). Translating evidence to policy: Urban interventions and physical activity promotion in Bogotá, Colombia and Curitiba, Brazil. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 1(2), 350–360.

- Dollowitz, D., & Marsh, D. (2000). Learning from abroad: The role of policy transfer in contemporary policy-making. Governance: An International Journal of Policy and Administration, 13(1), 5–24.

- Duarte, F., & Rojas, F. (2012). Intermodal connectivity to BRT: A comparative analysis of Bogotá and Curitiba. Journal of Public Transportation, 15(2), 1–18.

- Evans, M. (2009). New directions in the study of policy transfer. Policy Studies, 30(3), 237–241.

- Filipe, L. N., & Macário, R. (2013). A first glimpse on policy packaging for implementation of BRT projects. Research in Transportation Economics, 39(1), 150–157.

- Foucault, M. (1985). Discipline and punish: The birth of the Prision. 1926–1984. In Discipline and Punish the birth of the prison (Vol. 1). Retrieved from http://www.loc.gov/catdir/description/random048/95203580.html

- Froschauer, P. (2010). An analysis of the South African Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) policy implementation paradigm. Proceedings of the 29th Southern African transport conference (SATC 2010) (pp. 16–19). Retrieved from https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/14844/Froschauer_Analysis%282010%29.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Haas, P. (2015). Epistemic communities, constructivism, and international environmental politics. In Epistemic communities, constructivism, and international environmental politics. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315717906

- Harris, A., & Moore, S. (2013). Planning histories and practices of circulating urban knowledge. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(5), 1499–1509.

- Hermann, G., & Hidalgo, D. (2004). The Bogotá model for sustainable transportation: Inspiring developing cities throughout the world. Trialog, 82, 11–15.

- Hidalgo, D., & Huizenga, C. (2013). Implementation of sustainable urban transport in Latin America. Research in Transportation Economics, 40(1), 66–77.

- Hidalgo, D., & King, R. (2014). Public transport integration in Bogotá and Cali, Colombia – Facing transition from semi-deregulated services to full regulation citywide. Research in Transportation Economics, 48, 166–175.

- ITDP – Institute for Transportation and Development Policy. (2018). History of ITDP. https://www.itdp.org/who-we-are/history-of-itdp/

- Jajamovich, G. (2013). Miradas sobre intercambios internacionales y circulación internacional de ideas y modelos urbanos. Andamios, 10(22), 91–111.

- Jajamovich, G. (2016). Historicizing the circulation of urban policies through career paths analysis: Barcelonian experts and their role in redeveloping Buenos Aires’ Puerto Madero. Iberoamericana, 18, 2010.

- Jajamovich, G. (2018a). Puerto Madero en Movimiento. Un abordaje a partir de la circulación de la Corporación Antiguo Puerto Madero (1989–2017) (IEALC). TeseoPress. Buenos Aires.

- Jajamovich, G. (2018b). Promoting large urban projects: (trans)local issues in Puerto Madero (Buenos Aires), 1989–2017. Revista De Urbanismo, (38), 1. doi:10.5354/0717-5051.2018.46811

- James, O., & Lodge, M. (2003). The limitations of ‘policy transfer’ and ‘lesson drawing’ for public policy research. Political Studies Review, 1(2), 179–193.

- Jara-Moreno, A. (2012). How Bogotá inspired sustainable cities across the globe. Retrieved from This Big City website http://thisbigcity.net/how-bogota-inspired-sustainable-cities-across-the-globe

- JICA. (1996). Estudio del Plan Maestro del Transporte Urbano de Santa Fé de Bogotá en la República de Colombia.

- Kain, J. F. (1975). How to improve urban transportation at practically no cost. Public Policy, 20(Summer 1972), 335–358. Translation by Alvaro Pachón. Como mejorar el transporte urbano a un costo minimo.

- Larner, W., & Laurie, N. (2010). Travelling technocrats, embodied knowledges: Globalising privatisation in telecoms and water. Geoforum, 41(2), 218–226.

- Levinson, H., Zimmerman, S., Clinger, J., & Rutherford, G. (2002). Bus Rapid Transit: An overview. Journal of Public Transportation, 5(2), 1–30.

- Lindau, L. A., Hidalgo, D., & de Almeida Lobo, A. (2014). Barriers to planning and implementing Bus Rapid Transit systems. Research in Transportation Economics, 48, 9–15.

- Lovell, H. (2017). Mobile policies and policy streams: The case of smart metering policy in Australia. Geoforum, 81, 100–108.

- Lovell, H. (2019). Policy failure mobilities. Progress in Human Geography, 43(1), 46–63.

- Mallqui, Y. Y. C., & Pojani, D. (2017). Barriers to successful bus rapid transit expansion: Developed cities versus developing megacities. Case Studies on Transport Policy, 5(2), 254–266.

- Mccann, E. (2011a). Urban policy mobilities and global circuits of knowledge: Toward a research agenda. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 101(1), 107–130.

- McCann, E. (2011b). Veritable inventions: Cities, policies and assemblage. Area, 43(2), 143–147.

- McCann, E., & Ward, K. (2010). Relationality/territoriality: Toward a conceptualization of cities in the world. Geoforum, 41(2), 175–184.

- McCann, E., & Ward, K. (2012). Mobile urbanism: Cities and policymaking in the global age. In International planning studies (Vol. 17). doi: 10.1080/13563475.2012.698062

- McCann, E. (2011). Mobile urbanism: cities and policymaking in the global age. University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis.

- Mejía-Dugand, S., Hjelm, O., Baas, L., & Ríos, R. A. (2013). Lessons from the spread of bus rapid transit in Latin America. Journal of Cleaner Production, 50(50), 82–90.

- Montero, S. (2017). Study tours and inter-city policy learning: Mobilizing Bogotá’s transportation policies in Guadalajara. Environment and Planning A, 49(2), 332–350.

- Montero, S. (2017a). Persuasive practitioners and the art of simplification. Novos Estudos - CEBRAP, 36(01), 13–34.

- Montero, S. (2017b). Worlding Bogotá’s Ciclovía. Latin American Perspectives, 44(2), 111–131.

- Nakamura, F., Makimura, K., & Toyama, Y. (2017). Perspective on an urban transportation strategy with BRT for developing cities. Engineering and Applied Science Research, 44(3), 196–201.

- Nikitas, A., & Karlsson, M. (2015). A worldwide state-of-the-art analysis for Bus Rapid Transit: Looking for the success formula. Journal of Public Transportation, 18(1), 1–33.

- Novick, A. (2009). La ciudad, el urbanismo y los intercambios internacionales. Notas para la discusión. Revista Iberoamericana de Urbanismo, 1, 4–13.

- Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2010). Mobilizing policy: Models, methods, and mutations. Geoforum, 41(2), 169–174.

- Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2012). Follow the policy: A distended case approach. Environment and Planning A, 44(1), 21–30.

- Pochet, P., Room, G., Benchmarking, S., Making, P., Mosher, S., Matsaganis, M., … Holder, J. (2006). When do policy innovations spread? Lessons for advocates of lesson-drawing. Harvard Law Review, 119(5), 1467–1487.

- Porto de Oliveira, O., & Pal, L. (2018). Nuevas fronteras y rumbos en la investigación sobre transferencia, difusión y circulación de políticas públicas: Agentes, espacios, resistencia y traducciones TT - Novas fronteiras e direções na pesquisa sobre transferência, difusão e circulação de polít. A Revista de Administração Pública (Online), 52(2), 199–220. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-76122018000200199

- Porto de Oliveira, O., & Pimenta de Faria, C. A. (2017). Policy transfer, diffusion and circulation. Novos Estudos, 36(107), 13–32.

- Rizvi, A., & Sclar, E. (2014). Implementing bus rapid transit: A tale of two Indian cities. Research in Transportation Economics, 48, 194–204.

- Robinson, J. (2011). The spaces of circulating knowledge: City strategies and global urban governmentality. In K. McCann & E. Y. Ward (Eds.), Globalization and community : Mobile urbanism : Cities and policymaking in the global age (pp. 15–40). Minnesota University Press. Minneapolis, MN and London, UK. 2011

- Rose, R. (1991). What is lesson-drawing? Journal of Public Policy, 11, 3. Retrieved from https://ideas.repec.org/a/cup/jnlpup/v11y1991i01p3-30_00.html

- Sengers, F., & Raven, R. (2015). Toward a spatial perspective on niche development: The case of bus rapid transit. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 17, 166–182.

- Silva Ardila, D. (2016). Policy mobilities and urban change: The case of bus rapid transit in Colombia (Dissertation). University of Illinois at Chicago.

- Sosa López, O., & Montero, S. (2018). Expert-citizens: Producing and contesting sustainable mobility policy in Mexican cities. Journal of Transport Geography, 67(June2016), 137–144.

- Stone, D. (1996). Capturing the political imagination: Think tanks and the policy process. London: Frank Cass.

- Stone, D. (2000). Non-governmental policy transfer: The strategies of independent policy institutes. Governance, 13(1), 45–70.

- Stone, D. (2001). Learning lessons, policy transfer and the international diffusion of policy ideas. CSGR Working Paper No. 69/01 April 2001. Available at: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/2056/1/WRAP_Stone_wp6901.pdf

- Stone, D. (2002a). Global knowledge networks. Global Networks, 2, 1–12. Retrieved from http://www.cps.ceu.hu/publications/stone/2002/2230

- Stone, D. (2002b). Using knowledge: The dilemmas of “Bridging research and policy.”. Compare, 32, 285–296.

- Stone, D. (2007a). Recycling bins, garbage cans or think tanks? Three myths regarding policy analysis institutes. Public Administration. Volume 85, Issue 2. June 2007. Pages 259–278. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.2007.00649.x

- Stone, D. (2007b). Market principles, philanthropic ideals, and public service values in international public policy programs. PS - Political Science and Politics, 40(3), 545–551.

- Stone, D. (2008). Global public policy, transnational policy communities, and their networks. Policy Studies Journal, 36(1), 19–38.

- Stone, D. (2009). Private philanthropy or policy transfer? The transnational norms of the Open Society Institute. Policy & Politics, 2(5), 255.

- Stone, D. (2013). Knowledge actors and transnational governance: The private-public policy nexus in the global agora. Palgrave Macmillan. London

- Stone, D. (2014). Knowledge actors and transnational governance: The private-public policy nexus in the Global Agora. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 16. doi:10.1080/13876988.2014.887608

- Stone, D. (2015). The Group of 20 transnational policy community: Governance networks, policy analysis and think tanks. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 81(4), 793–811.

- Stone, D., & Ladi, S. (2017). Policy analysis & think tanks in comparative perspective. In M. Brans, I. Geva-May, & M. Howlett (Eds.), Handbook on comparative policy analysis. Routledge.

- Stone, D. (2017). Understanding the transfer of policy failure: bricolage, experimentalism and translation. Policy And Politics, 45(1), 55–70.

- Stone, D., & Ladi, S. (2015). Global public policy and transnational administration. Public Administration, 93(4), 839–855.

- Suzuki, H., Cervero, R., & Iuchi, K. (2013). Transforming cities with transit: Urban development. In Urban development series. Retrieved from http://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/978-0-8213-9745-9#

- Theodore, N., Peck, J., & Brenner, N. (2009). Urbanismo neoliberal: La ciudad y el imperio de los mercados. Temas Sociales SUR, 66, 1–11. Retrieved from www.sitiosur.cl

- Wood, A. (2014). Learning through policy tourism: circulating bus rapid transit from south america to south africa. Environment and Planning A, 46(11), 2654–2669.

- Wood, A. (2015a). The politics of policy circulation: Unpacking the relationship between South African and South American cities in the adoption of Bus Rapid Transit. Antipode, 47(4), 1062–1079.

- Wood, A. (2015b). Multiple temporalities of policy circulation: Gradual, repetitive and delayed processes of BRT adoption in South African Cities. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(3), 568–580.

- Wood, A. (2016). Tracing policy movements: Methods for studying learning and policy circulation. Environment and Planning A, 48(2), 391–406.

- Wright, L., & Hook, W. (2007). Bus Rapid Transit planning guide. ITDP. Retrieved from http://www.itdp.org/index.php/microsite/brt_planning_guide_in_english

- Zapata, P., & Zapata Campos, M. J. (2015). Unexpected translations in urban policy mobility. The case of the Acahualinca development programme in Managua, Nicaragua. Habitat International, 46, 271–276.