ABSTRACT

This themed issue entitled Social Investment in the Knowledge-Based Economy aims to investigate desirable policy packages of social investment for the knowledge-based economy, the interactions between policy and economic inequality, and political and institutional configurations that shape policies. This introduction to our themed issue situates the contribution of the volume in the literature, summarizes the main findings and their implications, and identifies core issues for a future research agenda. We trace the development of the social investment approach over time and across regions, and we explain its logic and the accumulated evidence supporting its importance. We then link our contributions squarely to the transition to the knowledge economy and the concern with innovation, growth, and inequality. We summarize the policy lessons emerging from the individual articles which emphasize specifically the need to treat social investment as complementary to social protection. We also summarize the insights into the politics of generating support coalitions for the introduction of effective social investment policies, emphasizing the leadership role of political parties in shaping both public preferences and legislation. Finally, we outline some key unanswered questions, among them questions regarding the obstacles to major progress in social investment so far and the impact of immigration and party system fragmentation on future progress.

Background of the subject area and recent developments

In the past 30 years, technological advances, demographic changes, and globalization have combined to put pressure on labor markets and enhance inequality in upper and upper middle-income countries around the world. Global capital markets have also resulted in periodic localized or global economic crises. At the same time, productivity increases have slowed. Governments have responded to these pressures with a wide variety of policies, navigating between the double imperatives of fostering economic innovation and growth and improving the welfare of their populations. In this context, the idea and practice of social investment assumed prominence in the repertoire of policy responses. Social investment is typically understood as public policy or spending that directly aims to promote an individuals’ capacity (Lundvall & Lorenz, Citation2012). In this respect, it could be any welfare state program in a broad sense, but it normally includes expenditures and policies related to families’ relationships with the economy, human capital improvement, and activation policies for employment (Prandini, Orlandini, & Guerra, Citation2016). Hemerijck (Citation2017, p. 19) distinguishes three interrelated functions of social investment: improving the stock of human capital, easing the flow of life and labor market transitions, and providing a buffer in the form of universal social safety nets for income protection and economic stabilization.

Origins and logic of the social investment approach

Social investment has a long tradition in the Nordic welfare state regimes, even though the label was not coined until the 1990s. Social investment policies were linked to the Nordic models of industrial modernization and labor market policies. These policies were particularly pronounced in Sweden. Rather than subsidizing jobs in declining industries, Swedish governments invested in retraining workers for emerging production methods and in helping them relocate to growing areas. With the shift to the knowledge economy, governments began to invest in life-long learning, from early childhood to the pension age. The concern with learning in early childhood squared with another important goal, the provision of care for small children, which was coming to the forefront as women’s labor force participation increased. So, the life-long learning agenda and the work/family conciliation agenda reinforced each other.

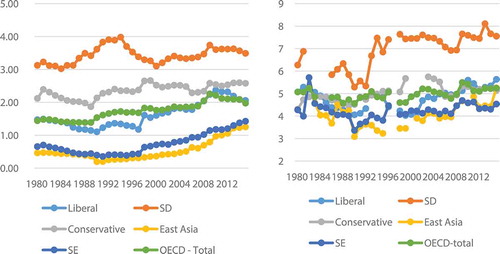

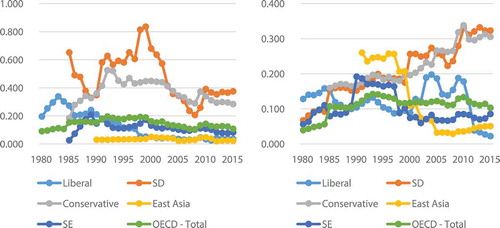

Bismarckian welfare states initially responded to deindustrialization and rising unemployment beginning in the 1970s with passive labor market policies, offering long-term unemployment benefits and putting large numbers of older workers on disability pensions. This response led to falling labor force participation rates among men and to a perceived inactivity crisis. The timing varied, with the Netherlands being an early stark example, but the tendency was similar in the continental countries. Increasing expenditures and falling tax revenue highlighted the need for activation and for increasing women’s labor force participation. Bringing more women into the labor force in turn required the creation of more part-time jobs and the development of work/family conciliation policies. Declining fertility rates in the continental countries and the Nordic example of higher fertility rates further underlined the need to make it possible for women to combine paid work and rearing families. Finally, as the decline of religiosity weakened the bond between women and Christian democratic parties, some of these parties perceived a need to change their policies to appeal to women (Hien, Citation2013; Morgan, Citation2013). This was clearly not the case for the Christian Democrats in Italy and the conservative party in Spain. As and make clear, they remained laggards in family policy as well as in other areas of social investment. In all areas, the social democratic welfare states have been the leaders, followed by the Bismarckian. The liberal welfare states increased their family spending and their education expenditure to the OECD average, but they remained way lower in spending on training and on public employment service and active labor market policy spending.

Figure 1. Family (1a, left) and education (1b, right) spending from 1980 to 2015.

Figure 2. Training (2a, left) and Public Employment Service (2b, right) spending (within ALMP) from 1980 to 2015. *% of GDP, Liberal (US, UK), SD-Social Democratic (Sweden, Denmark), Conservative (France, Germany), East Asia (Japan, Korea), SE-Southern European (Italy, Spain). Source: SOCX Data, OECD (Citation2019a)

East Asian countries built their welfare states a lot later than European and North American countries, and their original developmentalist model put heavy emphasis on mobilizing and protecting labor to support economic growth. As and show, their expenditure levels remained comparatively low. Yet, in line with the fertility crisis and rapid ageing since the 1990s, they also began to increase social investment spending. The fertility crisis provided additional incentives to adopt family support policies. In contrast, they did not invest in training and they greatly reduced their expenditures on public employment services and active labor market policies.

The basic goals of social investment came to be articulated as emphasizing predistribution rather than re-distribution, or preparing rather than repairing, by building an active rather than a passive welfare state (Hacker, Citation2011; Huber & Stephens, Citation2015; Morel, Palier, & Palme, Citation2012). The central ideas are (1) to educate a labor force that is and remains qualified for new jobs in the knowledge economy and that fosters innovation and thus the competitiveness of national economies, (2) to raise employment levels in the society by integrating women, young people, and the unemployed into the labor force by providing specific support services, from child care to job training and retraining and relocation, and (3) with these measures to enable people to earn a living rather than relying on transfer payments from the state and to keep inequality from rising to ever higher levels.

Many of the issues relevant for optimal policy choices to support a successful transition to the knowledge economy both from a societal and an individual point of view have been discussed in the literature. Endogenous growth theory has long emphasized the importance of human capital for economic growth (e.g. Barro, Citation1991; Romer, Citation1994). Typically, human capital was operationalized with average years of education in the population. Hanushek and Woessmann (Citation2008, Citation2012) have shown that the effect of average years of education in the adult population on economic growth is much weaker than the effect of cognitive skill scores on standardized tests administered to secondary school students. When they substituted the skills measure for average years of education and controlled for the initial level of GDP per capita in a regression analysis, the variation explained in economic growth increased from 25% to 73%. This is strong evidence for the importance of investment in skills for economic success at the level of a society.

The level and distribution of skills in a society have important implications not only for the competitiveness of national economies at the macro level but also for the ability of individuals to function successfully in these economies at the micro level. There is an extensive literature on the impact of technological change and globalization on the dualization of labor markets (e.g. Emmenegger, Häusermann, Palier, & Seeleib-Kaiser, Citation2012; Frey & Osborne, Citation2013; Goos, Manning, & Salomons, Citation2014; Oesch, Citation2013). The demand for and the compensation for skilled workers is rising, and the employment and earnings prospects for unskilled workers are declining, giving rise to long-term unemployment among the latter and overall inequality in the income distribution. Societies that are losing the race between education and technology are seeing their levels of inequality increase steeply, a prime example being the United States (Goldin & Katz, Citation2008). Inequality in educational achievement is strongly associated with earnings inequality (Nickell, Citation2004). In contrast, levels of education spending are negatively associated with the pre-tax and transfer Gini of household income inequality in an analysis of data for 18 post-industrial societies from the 1970 s to 2010 (Huber & Stephens, Citation2014).

Given the importance of skills for both economic growth and equity, scholars have paid much attention to educational systems and regimes of skill formation. Among regimes of skill formation, vocational education and training (VET), as opposed to general school-based education, has been credited with providing essential skills and entry into well-paying jobs to young people as an alternative to tertiary education (Busemeyer, Citation2015; Thelen, Citation2004). As a complementary measure, opportunities for continuous training to keep skills from becoming obsolete, or for retraining of workers whose skills had become obsolete, have been a central feature of active labor market policies (ALMPs), though with mixed results (Burgoon, Citation2017; Clasen & Clegg, Citation2011).

Given the overwhelming evidence of the impact of socio-economic background on students’ educational achievement, the fostering of education and skill formation came to include early childhood education and care (ECEC) (Urban, Vandenbroek, Lazzari, Peeters, & van Laere, Citation2011). Expansion of public support for ECEC has the dual purpose of preparing children from disadvantaged backgrounds to succeed in school and of making it possible for women to combine paid work and family responsibilities (Esping-Andersen, Gallie, Hemerijck, & Myles, Citation2002; León & Pavolini, Citation2014). In the context of the catch-up of female to male educational achievement, facilitating women’s entry into the labor force is not only a step towards greater gender equity but also a means of mobilizing talent and thus the productivity of the economy and of maintaining household income without the need to rely on welfare state transfers (Hobson, Citation2014). Particularly in the context of the disappearance of well-paying jobs for low-skilled workers and thus of the option for such workers to support a family, increasing female labor force participation is essential for keeping families out of poverty.

The social investment welfare state is essentially a service state. Services in education and training, but also in the care of children and the elderly, and in job placement are at the very core of creating and mobilizing human capital. This raises the question whether the public sector is capable of providing these services effectively, or whether cooperation with private providers is more effective. There may be trade-offs between accessibility and results, such as between school-based and firm-based vocational education and training. The former is practiced in Sweden, for instance, and the latter in Germany, and the former provides greater accessibility but the latter more direct entrance into jobs after completion of the training (Busemeyer, Citation2015). Reliance on private providers in education has often been promoted in the interest of ‘choice’ and competition. On the other hand, depending on the rules of operation for private providers, their services may be more expensive and may increase inequality among the recipients of these services.

Recent developments

The practice of social investment received official endorsement from the European Union with the launching of the Lisbon agenda in 2000. The goal of turning Europe into the ‘most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world’ apparently received wide support. The turn to social investment was also in part a response to the neoliberal assault on the welfare state and the rising levels of poverty and inequality (Jenson, Citation2010). It was part of the search for a new welfare state. However, as social investment was to become a European strategy, the Nordic model of social investment was in decline. The economic crisis of the early 1990s and the frequency of center-right government in Sweden beginning in 1991 resulted in permanently higher unemployment and a greater emphasis on fighting inflation. Spending on labor market training was reduced significantly and shifted to employment agencies assisting the unemployed in the job search. Unemployment benefits were reduced and qualifying conditions were made more stringent (Esser, Citation2015, p. 183). At the same time, the center-right governments also introduced private provision into social services, from education to health and care services. The justification was that this would increase ‘consumer choice’ and make these services more efficient (Blomqvist, Citation2004). Deteriorating PISA scores among students and sudden close-downs of schools suggested that at least in the field of education these expectations were not borne out (Henrekson & Jaevervall, Citation2016).

Despite the apparent widespread support for social investment policies, disagreements existed from the beginning on the question of their relationship to traditional social policies (Morel et al., Citation2012; Nolan, Citation2013); would social investment complement social protection, or was the goal to replace social protection? And if the goal was to replace social protection, what would be the sequence, when would this be possible? Politically, the two sides of the argument became identified with advocates of the Third Way and advocates of the comprehensive welfare state, as exemplified by the Nordic model before its decline. These disagreements were aggravated by the economic crisis of 2008 and subsequent pressures for austerity.

The disagreements concern the question of the need for social assistance or the passive welfare state during the transition to the new welfare state and on a permanent basis for those who, for a variety of reasons, do not succeed in the knowledge economy (Cantillon, Citation2011). Indeed, the relationship between social protection or social consumption expenditures and social investment expenditures, or between the passive and the active welfare state has been a highly contentious issue in politics (Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt, & Kriesi, Citation2015; Garritzmann, Busemeyer, & Neimanns, Citation2018). As noted, the social investment state was originally conceived by some politicians at least in part as an alternative to the passive welfare state that dealt with rising long-term unemployment by putting people on early pensions or disability pensions (Giddens, Citation1998). The concept of ‘prepare rather than repair’ reflects this conceptualization (Morel et al., Citation2012), and it was politically linked to the ‘third way’ path charted by leaders like Tony Blair.

In the ‘third way’ view the social investment welfare state was compatible with the deregulation of labor markets and cuts in social transfers, particularly unemployment benefits and other transfers to able-bodied people of working age (Morel et al., Citation2012). Relatedly, in this view active labor market policies could be oriented more towards workfare activation than towards enabling workers to increase their skill sets. What the advocates of this path failed to recognize is that the financial hardship of unemployed workers has repercussions for their children and their children’s ability to learn. Moreover, cuts in social protection in the longer run lead to the development of private insurance alternatives for the better off. Such developments generate not only greater differences in social protection but they are likely to make the disadvantaged groups absolutely worse off because their benefits keep getting cut. As better-off groups resort to private solutions, their support for public social protection declines and their resistance to taxation strengthens (Seeleib-Kaiser, Citation2012).

Social scientists from the beginning emphasized the synergistic relations of social protection with social investment (Armingeon & Bonoli, Citation2007; Hemerijck, Citation2017). In particular, children need a secure home environment to take advantage of the opportunities offered by education at all age levels. At the macro level, this can be seen in the depressing effect that poverty and inequality in the parents’ generation have on test scores of school-age children (Huber & Stephens, Citation2015). Recent work has also shown that the education premium is shaped not only by the supply of education but by the general welfare state in which it is embedded (Weisstanner & Armingeon, Citation2018). Bell, Chetty, Jaravel, Petkova, and Van Reenen (Citation2018) have warned that a neglect of support for low-income families might have costs at the societal level because of ‘lost Einsteins.’ In short, the arguments for synergy have been strong, but fiscal constraints and political pressures have induced governments to make trade-offs.

Critics of social investment have made an important argument that has implications for the trade-off. Investment in education may actually enhance advantages conveyed by socio-economic background of students. The critics of the social investment agenda have referred to this as the ‘Matthew effect’ – ‘to them that has, shall be given’ (Bonoli, Cantillon, & Van Lancker, Citation2017, p. 67, cf. Cantillon, Citation2011), meaning that children and adults who are already better positioned in the income distribution are better able to take advantage of the social investment programs (Bonoli & Liechti, Citation2018). If these critics are correct, the social investment strategy is bound to fail in counteracting rising inequality, unless it is preceded and accompanied by social protection policies that reduce socioeconomic differences.

While the leadership role of the Nordic model in social investment diminished, new concerns emerged and insights were gained that kept social investment at the top of the agenda. First, slow economic growth in the decade after the 2008 crisis raised concerns over a lack of innovation (Gordon, Citation2017). Expenditure on research and development alone did not seem to solve the problem, so the search began for ways to educate creative individuals and teams who could lead the way in innovation. Since the need to enlarge the pool of potential innovators was recognized, the search for innovation has led back to social investment. In addition, research into the origins of innovation in the post-WWII period showed very clearly that public funding has been totally central (Hacker, Citation2015, p. xxiii). These insights have strengthened the voices of academics and politicians advocating for public investment in life-long education and training and in research (Hemerijck, Citation2017). In contrast, initiatives to create low-wage jobs for low-skill individuals are blamed for perpetuating if not aggravating inequality and contributing nothing to innovation and improved productivity by various international organizations (ILO, OECD, World Bank Citation2014; International Labor Organization [ILO], Citation2016).

Second, two very different socio-economic trends came together to highlight the issue of inter-generational justice. Increasing indebtedness of countries on the one hand and climate change on the other hand have raised the question whether the present generation is engaging in reckless consumption at the expense of future generations. This concern has been heightened by the realization that child poverty has grown significantly. Clearly, welfare states vary tremendously in their allocation of expenditures to different age groups. Following Julia Lynch’s pioneering work (Citation2006), Vanhuysse (Citation2013, p. 27) created an index of elderly bias in social spending and found that Italy and Greece were at one end of the spectrum, spending roughly seven times more on each elderly person than each non-elderly person, whereas the Nordic countries were towards the lower end with a ratio of a little more than 3:1, and South Korea had the lowest elderly bias with a ratio of about 2.5:1. Even taking into account that some of these funds are redistributed by the elderly to their families, these private transfers are likely to aggravate inter-generational inequalities and the reproduction of social inequalities (Künemund, Motel-Klingebiel, & Kohli, Citation2005). Moreover, these private redistributions cannot create the type of educational system that is needed to maximize the development of talent for successful functioning in the knowledge economy.

Third, the debate about insiders and outsiders widened to include not just low-skilled unemployed but also people at varying skill levels on temporary employment contracts or part-time contracts, and people in the gig economy (Emmenegger et al., Citation2012; Palier & Thelen, Citation2010). It has also become clear that women and old people are disproportionately represented among those with temporary and part-time contracts (OECD, Citation2019b, p. 70). Benefits associated with temporary and part-time contracts vary across countries and companies, but typically they are inferior to benefits associated with permanent and full-time contracts. Essentially, many welfare states have become dualistic as well, reflecting the dualistic structure of the labor market. The gig economy has created jobs for people as independent contractors, with the consequence that they receive no employer contributions and thus carry the entire burden of ensuring for their social protection and access to health care where such access is based on health insurance (OECD, Citation2018, p. 19–21). This obviously is not a problem if the country has a national health service financed out of general taxation. However, the fact that in many cases the welfare state reflects the dualization of the labor market has increased the urgency of finding ways to improve the qualifications of the labor force in order to reduce the dualization of job quality.

Most of the literature we just discussed has come out of the experience of advanced post-industrial societies, essentially Europe and the Anglo-Saxon countries. It reflected the response of these countries to the shortcomings of the traditional passive welfare state in dealing with new economic and demographic realities, specifically the rising levels of unemployment and the changing roles of women. It has only begun to address social investment in other areas of the world (e.g. Garritzmann, Häusermann, Palier, & Zollinger, Citation2017) and thus the question of different patterns of development of social protection and social investment. It has also put inequality and employment in the center of attention and devoted less attention to societal success in innovation and economic growth, issues of greater salience in other areas of the world. Finally, it has heavily focused on public policy and paid less attention to a comparison of policies involving public and private actors. It is in these areas that our issue makes its contributions.

Aims and scope of the themed issue: academic and practical

The articles in this themed issue address the debates about social investment in the following three ways. First, we anchor the debate firmly in the connection to the knowledge economy and focus on education policy, active labor market policy, and innovation. As noted, early literature on social investment compared the Nordic social democratic with the Continental European Bismarckian welfare states, highlighting the emphasis on ALMP and labor mobilization, along with work/family conciliation policies supporting women’s labor force participation in the former, compared to the workforce reduction strategies and continued reliance on the male breadwinner model in the latter (Esping-Andersen et al., Citation2002). But, less has been investigated about the role of social investment policies specifically related to the knowledge-based economy, in which innovation has increasingly been the core agenda.

The contributors in this issue elucidate the conditions under which different social investment policies are likely to emerge and are more or less successful in realizing the goals of innovation, growth, and equity. Based on the findings, we draw out the lessons for policy choices that will facilitate the advancement of innovation, economic growth, and human welfare and we outline political strategies for implementing such policies. In doing so, we closely examine the dynamics of social protection and social investment. Our articles include the macro analysis of the relationship between social protection and social investment spending, the effect of social protection and social investment on innovation, and also citizens’ preference on social protection and social investment. Our contributors use both quantitative and qualitative comparative methods to explore the policy configurations that promote innovation, growth, and equity, along with the political conditions that facilitate or obstruct the implementation of such policies.

Second, we pay particular attention to the connections between these policies and income inequality, both as a cause and a consequence of social investment. Empirical studies have consistently shown an increase of income inequality and a growing productivity gap among firms and industries in advanced knowledge-based economies (Byrne, Fernald, & Reinsdorf, Citation2016; Piketty & Saez, Citation2006). Social investment or the lack thereof cannot be the single cause of or the main policy response against this phenomenon, but it is important to examine what role social investment policy and the politics that shaped it have played behind the scene. Such examination can provide policy and political implications for the welfare state. Public preferences regarding social investment are shaped by people’s experiences in the labor market (Häusermann, Kurer, & Schwander, Citation2016), which in turn are at least in part a result of social investment. We ask whether economic insecurity affects people’s attitudes towards social consumption and investment policies. Education is at the center of social investment and is generally seen as an instrument to counteract the rise in inequality generated by growing demand for high-skilled workers (Goldin & Katz, Citation2008). However, much depends on equal access to quality education. We ask whether different models of private-public financing mix of education policy produce different levels of income inequality.

Third, we analyze social investment developments in East Asia, Europe, and North America, and we provide explicit comparisons between and within dynamics in the different regions. Welfare states in Western and East Asian countries are far from following common social investment policy patterns and combinations of active and passive welfare state policies, neither in kind nor in extent. In Europe, it has been a matter of transforming well-developed welfare states, whereas in East Asia it has more been a matter of deciding where to put the emphasis in welfare state construction or expansion. While some previous studies explicitly deal with the development of social investment policies in East Asia (Fleckenstein and Lee’s work in Hemerijck, Citation2017), what is largely lacking in the literature is explicit comparisons of the emergence, functioning, and effects of social investment policies across regions. What were the motivations of different actors – political parties, governments, business, organized labor, civil society organizations, and the mass public – in pushing different social investment agendas? And how did the power balance between these actors, along with policy legacies, shape the nature of social investment policies? Such questions will help us identify the role of policy legacies and of different political coalitions promoting different versions of social investment under different structural conditions. We conduct both cross-regional comparisons and within-region comparisons so that we can reveal the theoretical driver of social investment politics beyond regional differences. These comparisons will also help us map the variety of policy instruments available to governments.

Our articles in this thematic issue connect well to each other in the four main areas of investigation – the investigation of policy packages for the knowledge-based economy, of the interactions between policy and economic inequality, and of political and institutional configurations that shape policies. Huber, Gunderson and Stephens; Koo, Choi and Park; and Choi and Kim all explore the nature of policy packages, the dynamics of social protection and investment, and the effects of different policy packages on innovation and distribution of benefits and income. Han and Kwon; Huber, Gunderson and Stephens; Choi and Kim highlight the connections between social investment policies and inequality, the first two directly look at inequality as a cause or a consequence and the final indirectly examines the effect of social investment on income inequality by analyzing the trade-off relationship between social protection and social investment. Finally, Shi and Kim; Kwon; Fleckenstein and Lee; and Huber, Gunderson and Stephens all focus on political and institutional configurations that shape different kinds of social investment policies and outcomes. These articles cover East Asian and Western countries; Shi and Kim conduct the within-region comparison, focusing on East Asia exclusively, whereas Fleckenstein and Lee engage in an explicit comparison of Europe and East Asia. Huber, Gunderson and Stephen use data from both regions to establish broad patterns.

Through these analyses, this thematic issue attempts to bring us closer to a nuanced understanding of at least some of the policy and political issues of the transition to the knowledge economy. Based on these contributions, we will explain key policy lessons and theoretical insights on the politics of social investment in the next section. Then, finally, we will discuss new research directions and agendas.

Main contributions and insights offered

Policy lessons: social investment

Social investment has been proposed as the new vanguard replacing the traditional welfare state and also as the new solution to knowledge-based economies (Morel et al., Citation2012). Its emphasis on pre-distribution rather than re-distribution and preparing rather than repairing has been regarded as productive and active compared to the transfer-oriented welfare state. Yet, looking back over the last two or three decades, the productivity gap within nations and inequality among individuals and households have increased and some see a deadlock of innovation (Gordon, Citation2017; Nordhaus, Citation2008). What has been the role of social investment and the welfare state? Does it fail to reduce the productivity gap and inequality? There are possible and plausible answers for the question. First, the actual spending on social investment has been too short to compensate for the negative effect of the structural change. Second, social investment can be useful for enhancing human capability, but may be less useful for reducing the gap and inequality due to its Matthew effect. Third, the emphasis on social investment is not wrong but the policy package might not be appropriate. It is true that it is less clear how to connect social investment into economic growth (Morel et al., Citation2012). Let’s review these answers.

The first answer is related to whether there has been an actual ‘social investment turn’ in contemporary welfare states. Choi and Kim in this issue have reviewed the literature of which results have been mixed. According to , it is clear that family policy has been the star of the social investment paradigm beyond the rhetoric, whereas compared to its theoretical importance, the spending on active labor market policies and education has not been increasing much, as seen in and . Instead of the convergence, the large spenders such as Sweden and Denmark have increased their training and education investment, but others have not changed their spending level much during the last three decades. The average social spending of the OECD welfare states is around 20% of GDP, but the ALMP and family spending is still less than 20% of total spending in many countries.

In the meantime, the number of industries with low productivity has increased and the productivity gap between firms and industries has widened. It is true that the number of people with tertiary education has increased considerably but this increase has not produced high productivity in developed countries. In the post-industrial economy, middle-paying jobs have significantly fallen whereas high and low-paying jobs have risen from 1993 to 2010 (Goos et al., Citation2014). In this context, it is hard to predict that the social investment spending could play the important role in reversing these trends. We need a rigorous study of the extent to which social investment policies have reduced the dualization, but compared to the magnitude of social risks, the size of social investment might not be enough.

The other possible answer is that the social investment approach could have a ‘Matthew effect’ as the vulnerable tend to benefit less from social investment policies compared to the better-off. These findings are supported by empirical studies (Bonoli et al., Citation2017; Busemeyer, Garritzmann, Neimanns, & Nezi, Citation2018). Depending on the structure of the policies, family policies, ALMPs, and education policies, particularly university education, are likely to benefit the middle-class more than the (near) poor. In other words, instead of reducing inequality, social investment could have contributed to heightening it. As a result, more investment could aggravate the polarization, particularly when social investment has come at the price of social protection.

This is linked to a third possible answer regarding the problem of the policy package of social investment. Hemerijck (Citation2017) and Esping-Andersen (Citation2002) argue that the effect of social investment can be enhanced when it goes with social protection, the function of buffer. At the individual level, it would not be possible to participate in ALMP or education programs without decent protection during that period. Without the protection program, only relatively better-off citizens could enjoy the programs. In that respect, social protection is an integral complement of the social investment paradigm. Choi and Kim’s article illustrates that social protection has been developed along with social investment. But they also observe that there is an increasing trade-off between the two types of programs under budgetary pressure. Therefore, they suggest that the right mix of the policy package has increasingly become difficult to achieve. As the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (Citation2017) rightly points out in the report on Tackling Inequality, progressive taxes and transfers are key components of efficient fiscal redistribution to implement decent social protection and social investment, which is also closely linked to the following issue.

An important aspect of policy packages is the public-private mix. A number of studies have investigated the public-private mix in social service areas at local and national levels (Gingrich, Citation2011; Greve & Sirovátka, Citation2014; Wollmann, Koprić, & Marcou, Citation2016). As countries moved from the bureaucratic paradigm to the new public management paradigm in the late twentieth century, the market has emerged as the key actor. This shift has been labeled marketization and privatization (Lane, Citation1997, p. 1). Yet, many studies doubt that the new public management paradigm has effectively delivered social and public services. It sometimes led to rising costs, decreasing accessibility, widening gap of service quality, exclusion of eligible service users from services, loose regulation, and the principle-agent problem (Van Slyke, Citation2003; Dharwadkar, George, & Brandes, Citation2000; Hefetz & Warner, Citation2012). These issues have given rise to a new public governance paradigm in which the government is expected to play a more active role in the new public-private mix (Denhardt & Denhardt, Citation2000). Some studies have observed that ‘back to insourcing from outsourcing’ and greater emphasis on public service sector can be achieved without much involvement of private actors (Hefetz & Warner, Citation2004; Girth, Hefetz, Johnston, & Warner, Citation2012). Huber, Gunderson, and Stephen in this issue also clearly show that ‘back to public’ is highly relevant in education policy in terms of reducing inequality and increasing students’ performance at the lower end of the achievement scale. Same as in public services, in their analysis, large involvement by private actors could be less helpful for equitable access to education, which would not only produce less equal opportunity but also less innovation in the future (Bell et al., Citation2018). Therefore, for the right mix of the policy package, the government should carefully design the source of financing of social investment policies.

According to the literature so far, one could well assume that the right mix of the policy package contributes to narrowing the productivity gap and to lowering inequality in the society (Bell et al., Citation2018; Miettinen, Citation2013). Does it also contribute to economic growth? Koo, Choi, and Park in this issue pay attention to the effect of social investment and social protection on innovation. Business and economic innovation have been the top priority of the national agenda in most countries as existing industries fail to produce enough jobs and economic value. Therefore, by boosting entrepreneurship, national governments have attempted to increase innovation activities, which is expected to drive economic growth. The conventional view is that the ‘cuddly’ capitalism enhances equity and welfare at the price of innovation, which is completely opposite in the ‘cutthroat’ capitalism such as the United States (Acemoglu, Robinson, & Verdier, Citation2012; Henrekson & Rosenberg, Citation2001).

However, an increasing number of studies has challenged this traditional view. The welfare state could contribute to innovation through enhancing human capital and skill formation, as well as increasing risk-taking behaviors (Bell et al., Citation2018; Filippetti & Guy, Citation2015; Mkandawire, Citation2007). In effect, Nordic countries, which are known for their extensive welfare state apparatus, have been praised as the most innovative economies (European Commission, Citation2019) whereas the lack of social safety nets including health insurance has been pointed out as the major barrier keeping talented workers in the US from becoming entrepreneurs (Fairlie, Kapur, & Gates, Citation2011). Hopkin, Lapuente, and Moller (Citation2014) also show that inequality is negatively correlated with innovation. Though social investment and protection are not sufficient conditions by themselves, they are crucial necessary conditions to produce innovation when they are combined with research and development (R&D) spending and appropriate regulation policy for entrepreneurs, which is shown in Koo, Choi, and Park’s article in this issue.

Even the digital transformation we are facing might aggravate the situation rather than improve it as ICT and artificial intelligence (AI) might not replace our jobs but replace our core skills. De-skilling tends to yield low-paying jobs. Therefore, simply better skills might not be enough in the digital era as it could be also replaced by AI. According to Marcolin, Miroudot, and Squicciarini (Citation2016) and Goos et al. (Citation2014), in contrast to routine tasks, creative tasks would not be easily replaced by AI. Just like entrepreneurship, creativity is the product of institutions rather than simply the result of individuals’ talent. Cognitive diversity and psychological assets such as happiness are core sources of creativity (MacLeod, Citation1973; Page, Citation2007). On the one hand, creative individuals could produce more STI (Science, Technology, Innovation), which is highly important for the economy but does not generate many jobs. On the other hand, they could also enhance DUI (Doing, Using, Interacting) innovation, a more grass-root type of innovation, which could create more jobs and increase individuals’ employability. Again, it is known that welfare states with decent social protection and investment tend to be associated with high levels of happiness of the population (Anderson & Hecht, Citation2015).

Contemporary knowledge-based economies have confronted a so-called productivity paradox. Despite the remarkable development of information & communication technology (ICT), the overall productivity growth rate has been falling since the 1990s except for about a decade around the millennium (OECD, Citation2016; Soete, Citation2018). Scholars such as Gordon (Citation2017) predict that the current slowing down of productivity is the beginning of a long winter in terms of innovation and growth. He further argues that four headwinds are slowing down economic growth, namely demographic change, education, inequality, and debts, which are directly related to social protection and social investment. These concerns are not only shared and promoted by progressives and the left. International organizations such as the OECD and the International Monetary Fund have vehemently pursued the agenda of inclusive growth and tackling inequality on similar grounds (IMF, Citation2017; Mahon, Citation2019; OECD, Citation2016). While the emphasis on inclusive growth has been widely spreading, the actual policy package of social investment and protection has not been specifically discussed. We argue that more and better quality of social investment with decent social protection is crucial in the knowledge-based economy.

Moreover, the articles in this issue evidently show that politics matter in shaping different social investment policies. Knowing what is right is not always translating in doing what is right. That is why some countries are performing well while most countries are struggling to balance inclusiveness and innovation. The next section is going to discuss this issue.

Politics of policy

Much recent research on the politics of social policy has focused on public opinion and voter preferences (e.g. Beramendi et al., Citation2015; Rueda & Stegmueller, Citation2019). Certainly, voter preferences are important, but they are not exogenous and they do not necessarily translate into policy. Rather, these preferences can be shaped by political actors, and it takes political actors with legislative power to translate them into policy. The key actors are political parties with a commitment to particular models of social policy and the electoral strength to shape policy.

There is wide agreement in the welfare state literature that long-term incumbency of different party families shapes the generosity and redistributive profile of welfare states. Social democratic or center-left parties shape generous and redistributive welfare states; Christian democratic parties shape generous welfare states that largely reflect the income distribution; and center-right parties shape non-generous welfare states that include much targeting (Esping-Andersen, Citation1990; Huber & Stephens, Citation2001; Van Kersbergen, Citation1995). Targeting is redistributive in structure but does not achieve much redistribution in these welfare states because of a narrow reach and non-generous benefits, a phenomenon labeled ‘the paradox of redistribution’ (Korpi & Palme, Citation1998). In general, this pattern translates well to the promotion of social investment policies, with center-left parties being the pioneers in advocating for the new paradigm. However, several Christian democratic parties broke away from their support for traditional family policies and gender roles and came to promote work/family conciliation policies (Morgan, Citation2012). Moreover, partisan incumbency effects on social policy have become weaker since the 1990s due to greater problem pressures and fiscal constraints, and due to the loss of vote shares of all established parties and greater need to form coalition governments (Huber & Stephens, Citation2015). Choi and Kim in their contribution to this volume show a significant left government effect for social investment expenditure in general over the entire period, but only in the earlier period for family policy.

Still, despite declining capacity to shape policy according to their own preferences, political parties remain the key actors with the capacity to shape public opinion and at least push policy in the desired direction. Arguably one of the key obstacles to the shaping of powerful pro-social investment coalitions is the growing perception in the mass public that politics has lost its capacity to counteract the effects of technological change, globalization, and demographic changes. The apparently inexorable pressures from these impersonal forces, however, are at least partly a political construct of neoliberal advocates of state shrinking. TINA (There Is No Alternative) became the mantra for neoliberal reformers in their attacks on the welfare state and their appeals to individualism and personal responsibility. As Hall (Citation2015) points out, what is needed is an appeal to find a new social contract that links social investment to innovation, economic success, the social function of corporations, and social solidarity. And policy programs need to specify how particular policies contribute to innovation, growth, and human welfare.

A second obstacle to the formation of broad pro-social investment coalitions is the long time horizon required for much of social investment to bear fruit (Myles, Citation2017). Early childhood education and care is arguably one of the most important ingredients of social investment packages, yet its results in terms of a more highly qualified and diverse labor force ready to promote innovation are some two decades removed from the initial investment. This invites linkages of long-term investment to shorter-term goals. In the case of early childhood education and care, the shorter-term goals are freeing mothers to enter the paid labor force and facilitating work/family conciliation. The political challenge then is not to lose sight of the long-term goal and forget about the education part in favor of simple early childhood care to get women into the labor force.

In developing policy programs, parties need to anticipate popular reactions and assess the potential of different groups to be incorporated as supporters of the program (Beramendi et al., Citation2015). As Han and Kwon show in their contribution to this volume, experiences of unemployment strengthen preferences for traditional social protection over social investment. The strength of the support for social protection is particularly strong among low-income individuals who have actually experienced a job loss. In contrast, preferences for social investment are higher among higher income than among lower-income unemployed people. In general, higher-income people prefer social investment over social protection. This suggests that pro-investment coalition building is particularly difficult in periods of high unemployment, economic stagnation or decline, and fiscal constraints that require trade-offs. In periods of low unemployment, economic growth, and/or fiscal room to maintain social protection of the unemployed, it is easier to build a pro-investment coalition among lower- and higher-income constituencies. In this sense, pro-investment preferences are clearly to be understood in context (e.g. Gingrich & Ansell, Citation2012) and the formation of pro-investment coalitions hinges in large part on cross-cutting configurations of economic insecurity across income groups (Garritzmann et al., Citation2018). As Kitschelt and Rehm (Citation2007) have shown, the kinds of higher education/higher organizational authority occupations that are conducive to generating welfare state support in general and social investment support, in particular, are socio-cultural professionals, that is, professionals involved in human interactions.

Public preferences are shaped not only by concrete experiences with employment, unemployment, and income but also by more general cultural legacies. Despite similar problem pressures, such legacies can push governments to different policy solutions. As Fleckenstein and Lee argue in their contribution to this volume, social conservatism among all age groups was more pronounced in Japan than in Korea, which made voters less inclined to support state intervention in child care in Japan. Interestingly, extremely low fertility in both countries pushed center-left governments to expand child care provision. However, in Japan, this initiative was relatively short-lived and the center-left began to support cash benefits for families, rather than childcare services, to respond to the more traditional family views of the electorate. In this case, the party leadership chose to follow voter preferences rather than trying to shape them.

Fleckenstein and Lee’s discussion of the German case shows the importance of party agency in pushing forward parental leave and childcare expansion. The social democratic party’s election manifesto for 2002 highlighted the need for childcare expansion as part of modernizing the German welfare state. This was done to appeal to younger women voters, but it brought the issue to the attention to all voters. This preference-shaping initiative turned into the precedent for family policy under the Grand Coalition of 2005–2009. The Christian democratic party wanted to compete with the social democrats for young women voters, and thus it broke with its tradition of support for the male breadwinner family and championed expansion of child care and introduction of a ‘daddy months’ component in parental leave. The party got the family ministry under the Grand Coalition and thus was able to claim credit for these innovations.

In general, women are more supportive of social investment than men, and particularly younger women are the most supportive constituency for work/family conciliation and investment in education (Wren, Citation2015, p. 231–2). This is true for women voters and women politicians. Women’s labor force participation, political mobilization, and social investment policies – particularly work/family conciliation policies – stand in a positive reinforcement relationship to each other (Huber & Stephens, Citation2000). As women’s labor force participation rises, demands for work/family conciliation policies rise, and the implementation of these policies in turn facilitates greater women’s labor force participation. Greater women’s labor force participation is also associated with greater political mobilization and thus the access of women to political leadership positions. Women in political leadership positions in turn are more likely than men to push for policies that facilitate women’s labor force participation. Such a self-reinforcing cycle works well once women’s labor force participation has reached a critical threshold. What is difficult and requires strong party leadership is to set the cycle in motion in the context of a society with conservative gender and family norms.

In the area of active labor market policies (ALMP), parties have to work with employers and unions in shaping and implementing policy. Ultimately, employers are supposed to hire the (re)trained workers and unions, where they are strong, may represent them before, during, and after (re)training. Theoretically, employers in knowledge-intensive sectors that are exposed to international competition should recognize the importance of having an educated labor force and thus should support social investment (Seeleib-Kaiser & Fleckenstein, Citation2009). However, these employers as well as their workers are also less supportive of taxes and public spending than employers and workers in knowledge-intensive social services (Wren, Citation2015). Again, it is the task of party leaders to articulate the importance of social investment for educating a labor force that will make knowledge-intensive sectors of all kinds successful and to generate support coalitions that include employers and workers in knowledge-intensive exposed sectors.

Finally, policy legacies profoundly shape the options for social investment policies. As Kim and Shi argue in their contribution to this volume, the choices in ALMP between Korea and Taiwan took the forms of public employment creation in the former and training and employment services in the latter country because of the presence of a tradition of public works and of political patronage in Korea and their absence in Taiwan. Political competition in both countries after democratization became more programmatic, but the practice of attracting voters through clientelism remained strong in Korea. In Taiwan, the progressive party in power from 2000 to 2008 advanced a program of human resource development and innovation and relied on employment activation. In contrast, the progressive Kim government in Korea built on the tradition of providing jobs in public works and concentrated on job creation. Under the conservative governments of Lee and Park, job creation became increasingly directed at their supporters, particularly the elderly, thus perpetuating a tradition of clientelistic politics.

Of course, policy legacies are not immutable constraints, as the shifts in family policies in many countries illustrate. Nevertheless, as we just saw in the case of active labor market policies, they can provide powerful incentives to choose some policies rather than others. A final area of social investment that deserves discussion in this respect is education policy. As Huber, Gunderson and Stephens show in their contribution to this volume, heavy reliance on private financing of education is associated with lower scores among low-achieving students and with greater inequality in earnings. Clearly, countries with strong traditions of private education will find it difficult to make a rapid transition to a high quality purely public education system. Private providers of education can form powerful interest groups mobilizing students and parents to pressure politicians to protect their interests. This is particularly true where private providers are for-profit corporations and are well connected to other business interests, and where they are affiliated with majority religions. Both of these conditions are present in Chile, for instance. However, in Chile and in other countries, many private schools are publicly subsidized, which gives governments some leverage to reduce the negative effects of reliance on private education by regulating these private schools. Prohibiting the levying of additional fees and the use of selective admissions are important steps towards reducing the inegalitarian results of private education. Again, if parties connect such steps to a program advocating social investment and innovation for success in the knowledge economy, they can play a leadership role in constructing political support coalitions.

Future research agenda

While the findings explained so far have added new insights for the future of the social investment approach, we also found further issues for our collective research agenda as explained below. In addition to an ongoing large scale of comparative research and publications (e.g, WoPSI project, see Choi, Fleckenstein, & Lee, Citation2020; Garritzmann et al., Citation2017), new research is required to establish more resilient and higher quality social investment policies in changing socio-economic environments. Specifically, we need to understand better the reasons for unfulfilled expectations regarding the expansion of social investment policies and their impact on gender roles. We also need to elucidate the conflicting goals of social investment and the rootedness of these goals in the national economic and political context. Finally, we need to explore in more depth the political obstacles to the establishment of high-quality social investment policies, such as immigration and party fragmentation.

First, more research is required on why social investment has not expanded more. As the amount of knowledge required for a decent job has considerably risen, the time and intensity of education and training should have increased as well. In addition, the educational system should receive more investment to enhance both skill formation and creativity. Yet, as seen in , education and training spending has not increased much, and the restructuring of the current educational system, particularly the implementation of lifelong learning, has made slow progress. The policy and political mechanisms accounting for these shortcomings should be studied further.

Second, the social investment approach seems not to have paved the way to complete the gender revolution (Esping-Andersen, Citation2009). The old employment-based male breadwinner model has changed to the flexible labor market model in most OECD countries, in which women are included as workers and earners. Although much has been written about this topic (Jenson, Citation2009; Saraceno, Citation2016), it is an incomplete revolution as gender inequality and segregation in the labor market are still evident. It is true that the socialization of care has considerably advanced even in East Asian countries, but less is known about detailed social investment strategies that would help to complete the ‘revolution’.

Third, the goals of social investment policy need to be discussed further. Some scholars are asking whether the social investment approach is subordinated to neoliberalism (Deeming & Smyth, Citation2015). Others see social investment as an instrument to pursue national competitiveness or capital interest. For example, in East Asia, the rhetoric of social investment has much to do with national competitiveness and the sustainability of the welfare state via increasing the fertility rate and producing better human capital (Peng, Citation2014). The politics of social investment that are neglecting individuals’ welfare and happiness should be reexamined.

It would also be important to closely investigate how the recent upsurge of economic nationalism and trade conflicts transforms welfare states by reconstructing their skill formation and education systems. Under newly emerging economic nationalism, the nation state would have no choice but to develop various industrial strategies, instead of relying on trade based on comparative advantage. But can a country with a particular Variety of Capitalism (VoC) change its path? Studies have investigated how particular VoCs produce systems of human capital formation, i.e., the social investment regime (Iversen & Soskice, Citation2009; Iversen & Stephens, Citation2008) or exhibit path-dependence, e.g., the UK case (Souto-Otero, Citation2013). However, others observe that the distinction between different VoCs has become less clear (Akkermans, Castaldi, & Los, Citation2009). Indeed, as advanced knowledge-based economies have confronted productivity slow-down and trade conflicts, the evolution of the social investment approach would be an important research topic.

A particularly important question regarding the politics of social investment policies is how mass immigration is shaping the possibility of forming supportive coalitions. Immigrants are particularly likely to benefit from life-long learning, so the question is whether this will be politically constructed as a welcome path to integration or whether support for universal access to life-long learning will fall victim to welfare chauvinism. Will the opponents of immigration attack the entire social investment agenda as disproportionally benefiting immigrants, or will they want to restrict access to citizens? What will be effective policy packages and frames that can be offered by parties supportive of social investment to counter either type of attacks?

Finally, how will the weakening of traditional parties and the greater fragmentation of party systems affect the credibility of the social investment approach? If parties are less able to shape the legislative agenda and in particular to bring long-term social investment policies to fruition, will the public remain supportive of these policies? And will parties be able to forge new coalitions to shape both public support for these policies and legislative support for their consistent implementation? Essentially, will political parties be able to put social policy in the service of creating successful and inclusive societies in the knowledge economy?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Young Jun Choi

Young Jun Choi is a Professor in the Department of Public Administration at Yonsei University. His research interests include aging and public policy, social investment policy, comparative welfare states, and comparative methods. His research has been published in international journals including Journal of European Social Policy, International Journal of Social Welfare, Ageing and Society, and Government and Opposition.

Evelyne Huber

Evelyne Huber is Morehead Alumni Distinguished Professor of Political Science at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. She studies democratization and redistribution in Latin America and post-industrial democracies. She is the author and co-author of several books, three of which have won book awards. She received an Honorary Doctorate in the Social Sciences from the University of Bern, Switzerland, in 2010.

Department of Political Science, University of North Carolina, Campus Box 3265, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3265 Phone: 919-962-3041, Fax: 919-962-0432

Won Sub Kim

Won-Sub Kim is a Professor of Sociology at Korea University in South Korea. He previously taught at Bielefeld University in Germany and at Kyung-Sang National University in South Korea. His research work centers on the theory of the welfare state, old age income security systems, and the East Asian social policy. He has published books and articles in German, English, and Korean languages, including ‘Institutionalisierung eines neuen Wohlfahrtsstaates in Ostasien? Eine Fallstudie über Südkorea’ (2006), and several journal articles in Government and Opposition, Zeitschrift für Soziologie, International Journal of Social Quality.

Hyeok Yong Kwon

Hyeok Yong Kwon is a Professor of Political Science and Director of the Center for the Study of Inequality and Democracy at Korea University. He previously taught at Texas A&M University in the USA. His research on comparative political economy and political behavior has been published in journals such as the British Journal of Political Science, Electoral Studies, Party Politics, Political Research Quarterly, and Socio-Economic Review, among others.

Shih-Jiun Shi

Shih-Jiunn Shi is a Professor of Social Policy in the Graduate Institute of National Development, National Taiwan University. He serves currently as Chair of the international organization ‘East Asian Social Policy Network’. His fields of research include comparative social policy with particular focus on East Asian social policy. He has published papers in major policy journals including the Journal of Social Policy, Social Policy & Administration, Policy & Politics, International Journal of Social Welfare, Public Management Review, Ageing & Society; Journal of Asian Public Policy; Environment & Planning C: Politics and Space.

References

- Acemoglu, D., Robinson, J. A., & Verdier, T. (2012). Can’t we all be more like Scandinavians? Asymmetric growth and institutions in an interdependent world (No. w18441). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Akkermans, D., Castaldi, C., & Los, B. (2009). Do ‘liberal market economies’ really innovate more radically than ‘coordinated market economies’? Hall and Soskice reconsidered. Research Policy, 38(1), 181–191.

- Anderson, C. J., & Hecht, J. (2015). Happiness and the welfare state: Decommodification and the political economy of subjective wellbeing. In P. Beramendi, S. Hausermann, H. Kitschelt, & H. Kriesi (Eds.), The politics of advanced capitalism. (pp. 357–380). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Armingeon, K., & Bonoli, G. (Eds.). (2007). The politics of post-industrial welfare states: Adapting post-war social policies to new social risks. London and New York: Routledge.

- Barro, R. J. (1991). Economic growth in a cross section of countries. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(2), 407–443.

- Bell, A., Chetty, R., Jaravel, X., Petkova, N., & Van Reenen, J. (2018). Who becomes an inventor in America? The importance of exposure to innovation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(2), 647–713.

- Beramendi, P., Häusermann, S., Kitschelt, H., & Kriesi, H. (eds.). (2015). The politics of advanced capitalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Blomqvist, P. (2004). The choice revolution: Privatization of Swedish welfare services in the 1990s. Social Policy and Administration, 38(2), 139–155.

- Bonoli, G., Cantillon, B., & Van Lancker, W. (2017). Social Investment and the Matthew effect. In A. Hemerijck (Ed.), The uses of social investment (pp. 66–76). Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

- Bonoli, G., & Liechti, F. (2018). Good intentions and Matthew effects: Access biases in participation in active labour market policies. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(6), 894–911.

- Burgoon, B. (2017). Practical pluralism in the empirical study of social investment. In A. Hemerijck (Ed.), The uses of social investment (pp. 161–173). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Busemeyer, M. R. (2015). Skills and inequality: Partisan politics and the political economy of education reforms in western welfare states. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Busemeyer, M. R., Garritzmann, J. L., Neimanns, E., & Nezi, R. (2018). Investing in education in Europe: Evidence from a new survey of public opinion. Journal of European Social Policy, 28(1), 34–54.

- Byrne, D. M., Fernald, J. G., & Reinsdorf, M. B. (2016). Does the United States have a productivity slowdown or a measurement problem? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2016(1), 109–182.

- Cantillon, B. (2011). The paradox of the social investment state: Growth, employment and poverty in the Lisbon era. Journal of European Social Policy, 21(5), 432–449.

- Choi, Y., Fleckenstein, T., & Lee, S. (2020). Welfare reform and social investment policy in Europe and East Asia. forthcoming. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Clasen, J., & Clegg, D. (eds.). (2011). National adaptations to post-industrial labour markets in Europe. (pp. 333–345). Oxford:: Oxford University Press (Work and Welfare in Europe).

- Deeming, C., & Smyth, P. (2015). Social investment after neoliberalism: Policy paradigms and political platforms. Journal of Social Policy, 44(2), 297–318.

- Denhardt, R. B., & Denhardt, J. V. (2000). The new public service: Serving rather than steering. Public Administration Review, 60(6), 549–559.

- Dharwadkar, R., George, G., & Brandes, P. (2000). Privatization in emerging economies: An agency theory perspective. Academy of Management Review, 32, 480–495.

- Emmenegger, P., Häusermann, S., Palier, B., & Seeleib-Kaiser, M. (eds.). (2012). The age of dualization: The changing face of inequality in deindustrializing societies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (2002). A child-centred social investment strategy. In G. Esping-Andersen, D. Gallie, A. Hemerijck, & J. Myles (Eds.), Why we need a new welfare state (pp. 26–67). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (2009). Incomplete revolution: Adapting welfare states to women’s new roles. Oxford: Polity.

- Esping-Andersen, G., Gallie, D., Hemerijck, A., & Myles, J. (eds.). (2002). Why we need a new welfare state. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Esser, I. (2015). Looking to the nordic? The Swedish social investment model in view of 2030. In C. Chwalisz & P. Diamond (Eds.), The predistribution agenda: Tackling inequality and supporting sustainable growth (pp. 177–190). London and New York: I.B.Tauris.

- European Commission. (2019). European innovation scoreboard. Brussels. Author.

- Fairlie, R. W., Kapur, K., & Gates, S. (2011). Is employer-based health insurance a barrier to entrepreneurship? Journal of Health Economics, 30(1), 146–162.

- Filippetti, A., & Guy, F. (2015). Skills and social insurance: Evidence from the relative persistence of innovation during the financial crisis in Europe. Science & Public Policy, 43(4), 505–517.

- Frey, C. B., & Osborne, M. A. (2013). The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation? University of Oxford. Retrieved from <http://www. oxfordmartin. ox. ac. uk/downloads/academic/The_Future_of_Employment

- Garritzmann, J., Häusermann, S., Palier, B., & Zollinger, C. (2017). WoPSI-the world politics of social investment: An international research project to explain variance in social investment agendas and social investment reforms across countries and world regions. LIEPP Working Paper No. 64. Paris: Sciences Po.

- Garritzmann, J. L., Busemeyer, M. R., & Neimanns, E. (2018). Public demand for social investment: New supporting coalitions for welfare state reform in Western Europe? Journal of European Public Policy, 25(6), 844–861.

- Giddens, A. (1998). The social investment state. In A. Giddens (Ed.), The third Way: Renewal of social democracy (pp. 99–128). Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Gingrich, J. (2011). Making markets in the welfare state. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Gingrich, J., & Ansell, B. (2012). Preferences in context: Micro preferences, macro contexts, and the demand for social policy. Comparative Political Studies, 45(12), 1624–1654.

- Girth, A. M., Hefetz, A., Johnston, J. M., & Warner, M. E. (2012). Outsourcing public service delivery: Management responses in noncompetitive markets. Public Administration Review, 72(6), 887–900.

- Goldin, C. D., & Katz, L. F. (2008). The race between education and technology. Boston, MA: Bellknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Goos, M., Manning, A., & Salomons, A. (2014). Explaining job polarization: Routine-biased technological change and offshoring. American Economic Review, 104(8), 2509–2526.

- Gordon, R. J. (2017). The rise and fall of American growth: The US standard of living since the civil war (Vol. 70). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Greve, B., & Sirovátka, T. (2014). Innovation in social services: The public-private mix in service provision, fiscal policy and employment. Farnham, Surrey, UK: Routledge.

- Hacker, J. (2015). The promise of predistribution. In C. Chwalisz & P. Diamond (Eds.), The predistribution agenda: Tackling inequality and supporting sustainable growth (pp. xxi–xxx). London and New York: I.B.Tauris.

- Hacker, J. S. (2011). The institutional foundations of middle-class democracy. Policy Network, 3, 33–37.

- Hall, P. (2015). Varieties of capitalism. In R. Scott & S. Kosslyn (Eds.), Emerging trends in the social and behavioral sciences (pp. 1–15). Wiley Online: John Wiley & Sons.

- Hanushek, E. A., & Woessmann, L. (2008). The role of cognitive skills in economic development. Journal of Economic Literature, 46(3), 607–668.

- Hanushek, E. A., & Woessmann, L. (2012). Do better schools lead to more growth? Cognitive skills, economic outcomes, and causation. Journal of Economic Growth, 17(4), 267–321.

- Häusermann, S., Kurer, T., & Schwander, H. (2016). Sharing the risk? Households, labor market vulnerability, and social policy preferences in Western Europe. The Journal of Politics, 78(4), 1045–1060.

- Hefetz, A. & M.E. Warner (2012) Contracting or Public Delivery? The Importance of Service, Market, and Management Characteristics. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22(2), 289–317.

- Hefetz, A., & Warner, M. (2004). Privatization and its reverse: Explaining the dynamics of the government contracting process. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 14(2), 171–190.

- Hemerijck, A. (2017). The uses of social investment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Henrekson, M., & Jaevervall, S. (2016). Educational performance in Swedish schools is plummeting – What are the facts? Stockholm: The Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences (IVA).

- Henrekson, M., & Rosenberg, N. (2001). Designing efficient institutions for science-based entrepreneurship: Lesson from the US and Sweden. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 26(3), 207–231.

- Hien, J. (2013). Unsecular politics in a secular environment: The case of germany’s christian democratic union family policy. German Politics, 22(4), 441–460.

- Hobson, B. (ed.). (2014). Worklife balance: The agency and capabilities gap. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hopkin, J., Lapuente, V., & Moller, L. (2014). Lower levels of inequality are linked with greater innovation in economies. London School of Economics US Centre. Retrieved from https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/usappblog/2014/01/23/lower-levels-of-inequality-are-linked-with-greater-innovation-in-economies/

- Huber, E., & Stephens, J. D. (2015). Predistribution and redistribution: Alternative or complementary policies? In C. Chwalisz & P. Diamond (Eds.), The predistribution agenda: Tackling inequality and supporting sustainable growth (pp. 67–78). London and New York: I.B.Tauris.

- Huber, E., & Stephens, J. D. (2000). Partisan governance, women’s employment, and the social democratic service state. American Sociological Review, 65(3), 323–342.

- Huber, E., & Stephens, J. D. (2001). Development and crisis of the welfare state: Parties and policies in global markets. Chicago: University of Chicago press.

- Huber, E., & Stephens, J. D. (2014). Income inequality and redistribution in post-industrial democracies: Demographic, economic and political determinants 1. Socio-Economic Review, 12(2), 245–267.

- ILO, OECD, & World Bank. (2014, September 10-11). G20 labour markets: Outlook, key challenges and policy responses (Report prepared for the G20 Labour and Employment Ministerial Meeting. Melbourne. Australia).

- International Labor Organization (ILO). (2016). Global Wage Report 2016/17: Wage inequality in the workplace. Geneva: ILO

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2017). IMF fiscal monitor: Tackling inequality. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- Iversen, T., & Soskice, D. (2009). Distribution and redistribution: The shadow of the nineteenth century. World Politics, 61(3), 438–486.

- Iversen, T., & Stephens, J. D. (2008). Partisan politics, the welfare state, and three worlds of human capital formation. Comparative Political Studies, 41(4–5), 600–637.

- Jenson, J. (2009). Lost in translation: The social investment perspective and gender equality. Social Politics, 16(4), 446–483.

- Jenson, J. (2010). Diffusing ideas for after neoliberalism the social investment perspective in Europe and Latin America. Global Social Policy, 10(1), 59–84.

- Kitschelt, H., & Rehm, P. (2007). New social risk and political preferences. In K. Armingeon & G. Bonoli (Eds.), The politics of post-industrial welfare states: Adapting post-war social policies to new social risks (pp. 70–100). London and New York: Routledge.

- Korpi, W., & Palme, J. (1998). The paradox of redistribution and strategies of equality: Welfare state institutions, inequality, and poverty in the western countries. American Sociological Review, 63(5), 661–687.

- Künemund, H., Motel-Klingebiel, A., & Kohli, M. (2005). Do intergenerational transfers from elderly parents increase social inequality among their middle-aged children? Evidence from the German aging survey. Journal of Gerontology, 60(1), 30–36.

- Lane, J.-E. (ed.). (1997). Public sector reform: Rationale, trends and problems. London: Sage Publ.

- León, M., & Pavolini, E. (2014). ‘Social investment’or back to ‘Familism’: The impact of the economic crisis on family and care policies in Italy and Spain. South European Society & Politics, 19(3), 353–369.

- Lundvall, B. Å., & Lorenz, E. (2012). Social investment in the globalising learning economy: A European perspective. In N. Morel, B. Palier, & J. Palme (Eds.), Towards a social investment welfare state?: Ideas, policies and challenges (pp. 235–257). Bristol: Policy Press.

- Lynch, J. (2006). Age in the welfare state: The origins of social spending on pensioners, workers, and children. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- MacLeod, G. A. (1973). Does creativity lead to happiness and more enjoyment of life? Journal of Creative Behavior, 7(4), 227–230.