Abstract

This article seeks to shed new light on the reality of Persian gardens by examining them as a trajective reality, being formed through a set of continuous and ongoing exchanges with various human and natural elements constituting its environment. More particularly, it aims to highlight the process of reciprocal engendering that existed between the garden and the worldview of traditional Iranian society. In this way, it shows how the Persian garden is not only the imprint of the cosmology of the Iranian people but also, insofar as it unfolds a certain world, reciprocally its matrix. A content analysis as well as the study of several cases have allowed the identification of three types of relationship between the garden and the world of the ancient Persians through which they co-construct one another. These are: analogy, enrichment and complementarity. Finally, this study explores the importance of the building of such relationships in contemporary landscape design.

Introduction

The development of environmental sciences and philosophical reflections, in particular, ecology and phenomenology, since at least the second half of the twentieth century, has clearly shown that we live in an interconnected and integrated world, a world ‘where things grow together’ and that ‘is obviously not a world where one thing causes the other. It is a phenomenal world rather than a physical world’. Footnote1 In other words, it is a world where each thing is rather the condition of other things, and all respond to each other at once. ‘They co-suscitate’,Footnote2 in terms of the French philosopher and geographer Augustin Berque. It comprises the concrescence of things, beings and facts, or the phenomenon in which things reciprocally presuppose, expect and elicit each other to become what they are.Footnote3

This vision of the world offers new ways of apprehending landscape. It calls on us to consider landscape no longer as an object in and of itself but rather as a relational entity that exists beyond its physical contours. It takes shape and meaning through multiple interactions and exchanges with the natural and cultural data of the milieu where it is located, and it participates reciprocally in the actual deployment of the latter. As such, the reality of landscape is ‘trajective’, that is to say that it born of a set of correspondences between the different ways in which a society establishes a relation with its milieu, like ecological and symbolic relationship.

It is in this perspective that this article proposes to study the gardening tradition in Iran and to delineate the relational fabric within which the gardens were developed. In other words, it seeks to explore the trajective reality of Persian gardens. This distinguishes the paper from the more traditional studies undertaken by either WesternFootnote4 or Iranian scholarsFootnote5 that focus almost exclusively on the description of the garden structure and the elements that compose it (such as water channel, wall, tree, terrace, pavilion), or on its symbolic foundations (myths, beliefs, traditions), or even on the natural characteristics of its environment (such as topography, climate, hydrology).Footnote6 However, in general, the Persian garden is examined only following a unilateral approach — exploring rather the incidences of the natural and cultural characteristics of the Iranian environment on the design of this placeFootnote7— whereas a relational approach — making it possible to grasp the interdependencies and the reciprocal impregnations between the two — is also important. By placing this co-construction at the heart of its research, it aims to make an original contribution to knowledge of these places; not only as the imprint but also as the matrix of a certain milieu or of a certain world.

That said, the task of outlining the entirety of correspondences (trajection) between the Persian garden and its environment at different levels (ecological, technical, symbolic, etc.) would clearly be beyond the scope of this article. Therefore, the present study focuses on the interrelationships between the way Iranian society designed these places and the way it perceived and conceived its world — in consideration, of course, of the fact that the worldview of the ancient Persians and their mode of spatial planning are closely linked to the natural and geographical realities of their milieu as well as the technical means and tools available to them at the time.Footnote8

Further, Iran and Iranian culture, like any human civilization, have traversed different cosmogonies and cosmologies in the course of their history. Roughly speaking, we identify three great periods: Iran of the ancient period (until the seventh century), Iran of the Islamic period, and Iran of the modern period (from the end of the nineteenth century until today). In this paper, I focus on the pre-Islamic period, characterized by Zoroastrianism,Footnote9 for the main reason that it exhibits a very enriching concrescence between things: between the way of life (pastoral) of the Iranian people, their use of the land (agricultural), their beliefs, myths and rituals as well as the ecological properties of their territory.

Research methodology

This study is a pioneering attempt to understand the Persian garden through the lens of trajective reality of landscape and has consequently employed a qualitative research strategy to compensate for the lack of data. The research sources and references, either in Farsi, English or French languages, have been mainly gathered from libraries and archives in Iran and France. In order to fully grasp the worldview of Iranian society in the pre-Islamic era, this study will first be based on sources concerning the Zoroastrian cosmogony, myths and cults, with careful consideration given to their influences on the Iranian relationship with nature. Moreover, I will refer to primary resources, such as the sacred texts of the Zoroastrians, the Avesta,Footnote10 that have seldom been scrutinized in the studies of Iranian and Western scholars on the Persian gardening tradition. A content analysis will be used to study the terms and the moral-religious concepts in which the notions of ‘nature’ and ‘heavenly world’ (paradise) are described and represented in Avesta texts; these notions are two important motifs of garden design in ancient civilizations.

In line with studying the trajectivity of Persian gardens, I will also analyze the way in which the garden is thought and designed in the Iranian culture of the pre-Islamic era. To this end, the literature review was made based on two threads: studies of a body of texts on the art of gardens in Iran from nationally and internationally recognized authors, and an examination of the examples of garden that had actually been built in antiquity and of which fairly precise plans still exist today. The data, collected notably from various archives in Iran, reinforced through site visits. Through employing an analytical approach, this research attempts to explore the structural elements in the Persian gardens and to identify the main characteristics of their layout. However, merely one analysis of the existing examples and the texts published about these gardens would not have allowed for an in-depth understanding of the reality of these places and how they are perceived and designed by Iranians. This is why I, in addition, performed a semantic and etymological analysis of the Avestan terms used by Iranian society to express the idea of the garden.

Finally, this research aims to correlate the results of the previous investigations to demonstrate the trajective reality of Persian garden, that is, how it takes shape and meaning through the multiple conjunctions and impregnations in its environment. To this end, I adopt a comparative strategy that allows creating a dialectical tension between the different analyses and, by doing so, bringing out the trajections that existed between the way Persian society symbolically conceived their world and the way they physically arranged their environment.

In doing so, this research allowed me to identify three types of trajection for examining the Persian garden: analogy, enrichment and complementarity. First, I will present the analogies that existed between the ancient Persians’ conception of the world and their mode of layout of the garden space. I will then discuss the enrichments that this garden brings to its site from a symbolic point of view. Finally, I will try to show how the Persian garden and its surrounding environment are complementary and interdependent at the semantic level.

Analogies

The term ‘analogy’ designates a relationship of resemblance or similarity between things subjected to comparison. This article examines the analogies between the way in which traditional Iranian society conceived its world and the way in which it designed its gardens. To be clear, this is done without referring to the chaharbagh patternFootnote11 often associated with Persian gardens. Conventionally understoodFootnote12 as an orthogonally planned garden divided into four by two perpendicular axes, this model has been questioned over the past decades. Recent historical and archaeological research by some scholarsFootnote13 has challenged not only the assumption of the existence of the quadripartite chaharbagh as the archetypal Persian garden but also the idea that it necessarily refers to a garden physically divided into four.

Persian garden, imago mundi and khshathra of the king

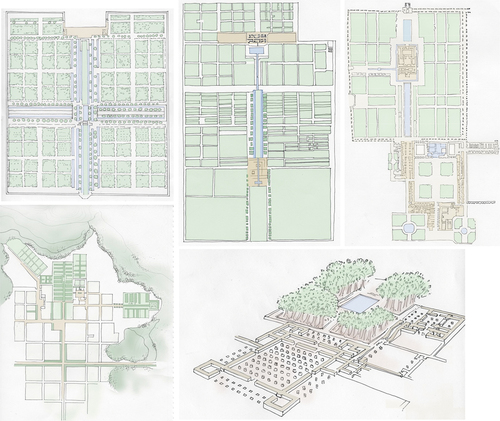

Using several case studies, this article has identified three major characteristics through which these gardens’ spatial organization refers to a cosmic order. The first is their geometrical order (). This orthogonality refers not only to technical factors, such as irrigation systems, agricultural techniques and surveyingFootnote14 but also to a cosmic order that ancient civilizations saw as absolute and perfect.Footnote15 The reproduction of this order on Earth essentially served as a means of ordering the disorder of the wild world or, in the words of Augustin Berque, of ‘cosmicizing’ it, and thus of making it reassuring and comprehensible.

FIGURE 1. Geometrical order of Persian gardens. From left to right and top to bottom: Gholshan Garden in Tabas, Eram Garden in Shiraz, Chehel Sotoun Garden in Isfahan, Ashraf gardens in Behshahr and Ardeshir II Garden-Palace in susa these garden plans are drawn by Claudia-Emma Farley-Dabis to show the orthogonality of Persian gardens and are based on : Mehdi Khansari, Minouch Yavari, and M. R. Moghtader, the Persian Garden: Echoes of Paradise (Washington, DC: Mage, 1998, pp: 42, 76, 98, 119, 142). © Shabnam Rahbar.

Moreover, Persian gardens are marked by a center consisting of the main building (the royal palace or kiosk) that determines the layout of important elements, such as the main entrance, the central pond, the shah joy (‘king of the moats’) and the main paths.Footnote16 This organization plays a fundamental role in the worlds of traditional Iranian society. As Alexandros Lagopoulos writes, these are all ordered ‘regardless of the number, shape and specific organization of their subdivisions’ according to a common principle, which consists of ‘the arrangement of peripheral elements authoring a central element, identified at the center of the universe and the Earth (…)’.Footnote17 Indeed, Zoroastrian cosmology represents the Earth in seven parts: a central region surrounded by six others, arranged either in concentric circles or in spokes. Thus, the city of Ecbatana (), which was the capital of the Median Empire around 700 BC, had a circular plan with seven concentric enclosures around the royal palace, each associated with a planet and bearing a distinct color.Footnote18 It is in this perspective that the central building of the gardens refers to the center of the world.

FIGURE 2. Circular pattern of Ecbatana. Source: Mahmoud Tavassoli, Urban Structure in Hot Arid Environments: Strategies for Sustainable Development (New York: Springer Cham, 2016, p. 20). © Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission.

Finally, the third characteristic feature of Persian gardens is the quadripartition of the building in their center. Called chahartaq (‘four arches’), it is most often a square construction, opening out to porches (taqs) on its four sides, and whose four angular pillars support a dome (). A characteristic element of Iranian architecture, the chahartaq is found in different types of built space, from the Sassanid fire temples (which are nothing more than isolated chahartaq) to the prayer halls of Safavid mosques, where it is integrated into a set of buildings. It appears, for example, in the great throne rooms of the Sassanid palaces in Firuzabad, Bishapur and Qasr-e Shirin. These rooms are of a cruciform design, topped by a central dome and equipped with four axial doors leading to annexed rooms, or to ivansFootnote19 or even talars.Footnote20 According to Eliade, this structuring of the center is the material translation of the view that the world extends from a center outward to the four horizons, or cardinal directions, and serves to ‘homologizing the dwelling place to the cosmos’.Footnote21 Eliade points out that in Bali as well as in certain regions of Asia, when one is about to build a new village, one looks for a natural crossroads where two roads intersect perpendicularly.Footnote22 The same is true of the Persian garden. With its quadripartite structure and open on four sides, the center of the garden becomes a place from which the four directions of space are projected. In this way, it perfectly evokes the deployment of the world ().

However, beyond this horizontal correspondence between the central building and the vision of the world, we can also identify another correspondence, this time vertical. Indeed, if the center of the world is a place open to the beyond through a cosmic axis, the palace — erected on an artificial platform — symbolizes very well this vertical axis (to be discussed in more detail below). We can therefore say that the center of the Persian garden is a cosmic center par excellence. From this center, one is not only connected to the four corners of the world but also to the beyond. It is thus a point where Earth and Heaven, the human and the divine, the finite and the infinite intermesh.Footnote23

It is important to emphasize that the inscription of this cosmic order on Earth has both a divine and a political meaning. It is a means of assimilating the land to the cosmos and, in so doing, of displaying the power and sovereignty of the king. To demonstrate this, I refer to the Avestan term khshathra (Xšaθra), meaning both ‘power, sovereignty’ and ‘the kingdom where this power is exercised’.Footnote24 In the Gathas,Footnote25 it is used as much as an attribute of celestial beings as of terrestrial ones. As such, it can designate the divine power of Ahura MazdaFootnote26 as much as the political power of a king. Or, it can designate the domain over which the unique divinity of Zoroastrianism exercises its power, being the universe, as much as the geographical area governed by a monarch, being the kingdom, country or territory. These two meanings of the term khshathra illustrate well to what extent the notion of royalty is intrinsically linked to that of territory in the thought of the ancient Persians. Indeed, insofar as developed land is considered as khshathra of the king, it had to reflect the superiority and the absolute domination of this political power. Hence, the correspondence between the khshathra of the monarch and the khshathra of God is translated by the landscape: the territory of the king is arranged in the image of God. Thus, just as the divine palace stands at the center of the universe, the king’s palace stands at the center of the city or garden. By placing the seat of their power at the center, the Persian kings wanted to position themselves at the center of the world and prove their legitimacy.Footnote27

It is thus quite clear that grasping the reality expressed through the space of the Persian garden requires more than simply referring to the conceptions of the world or to the notion of paradise. Other keys of understanding, such as the political and economic value of the land or the divine representation of royalty, also contribute to the constitution of its meaning. Thus, while the Persian garden certainly represents the cosmic order, it also represents the divine world of a political power, if not a consolidated empire or the legitimacy of the dynasty and its territorial control.

Enrichment

Enrichment is an action or a way of making something richer or more valuable, ‘especially by the addition or increase of some desirable quality, attribute, or ingredient’.Footnote28 The art of traditional Iranian gardens must be understood in this sense as well, namely, as a symbolic and semantic enhancement of a space. It is not simply an act of spatially organizing the Earth’s expanse but more fundamentally a process of cosmicization that results in the transformation of that expanse in a certain world. This type of trajection emerged from a critical inquiry into the scriptures of Zoroastrianism as to its myths and moral-religious concepts that might give meaning to the practice of gardening.

Persian garden, spandarmatîkîh and creation of a high place

The study of the teachings of Zoroaster, the founder of Zoroastrianism, clearly shows that his aim was to value civilization and civic construction, and to encourage his people to transition from a nomadic way of life toward a rural society of sedentary herders and cultivators. It is written, for example, in the Yasna XXXI, 9 and 10, that:

9. Thine was Armaiti, Thine the Ox-Creator, (namely) the Wisdom of the Spirit, O Mazda Ahura, because Thou didst give (the cattle) choice whether to depend on a husbandman or one who is no husbandman. 10. So she chose for herself out of the two the cattle-tending husbandman as her lord to guard the Right, the man that advances Good Thought. He that is no-husbandman, O Mazda, however eager he be, has no part in this good message.

Furthermore, the expression spandarmatîkîh translates well to this mode of existence that man must assume. The term is derived from Spandarmat (the Pahlavi form of the name Spenta Armaiti) and has been translated by Henry Corbin as ‘sophianity, the sophianic nature of Spenta Armaiti’.Footnote29 In Zoroastrian cosmology, Spenta Armaiti is one of seven highest divine entities embodying a moral and religious principle.Footnote30 It appears as the divine sage with ‘the Good Thought’ (Gathas XLIV, 4) or with bountifulness (Yasht, XVI, 3). It is this power that yields or engenders prosperity of the regions and the abundance of goods. Spenta Armaiti also has a material dimension, an incarnation in the elements of the earthly world, and hence corresponds to the element earth. According to Corbin, for the human being, assimilating spandarmatîkîh means to exemplify in his or her person the mode of being of Spenta Armaiti (…).Footnote31 Thus, Spenta Armaiti is the sage who does good deeds, while humans are entreated to embody these same qualities by doing their part to contribute to the development and prosperity of the earthly world through their actions. This work can be achieved through a way of life based on agriculture and animal husbandry.

It is for this fundamental reason that the Zoroastrian myths and legends do not only impart the rituals and the worship that man must render to the heavenly spirits by his words (prayers) but also prescribe actions that man must perform with his hands on the land, or soil. In this regard, Paula R. Hartz writes: ‘In a time when most people believed that worship consisted mainly of elaborate rituals to satisfy angry deities, he (Zoroaster) preached a religion of personal ethics in which people’s actions in life were more important than ritual and sacrifice’.Footnote32

In this context, the cultivation of trees and flowers took on the meaning of a liturgy. Activities such as making the land fertile, cultivating fields, raising domestic animals and building qanats, in short, making the earth habitable, was valued. In Zoroastrian ethical terms, these actions are considered as ‘good deeds’ (Huvarshta) by which man can increase the benefits of Ahura Mazda in the earthly world. It is by this, among other ways, that man can make the Spenta Armaiti happy, allowing in return for abundance, fertility and happiness for man in his earthly life.Footnote33 Moreover, according to the scriptures of the Avesta, developed and cultivated places are the seat of beneficial powers, countering the evil forces of Ahriman. This is expressed through two Avestan terms that designate the garden: baga, referring to the garden as ‘the abode of the gods’, and pairi-daeza, meaning, as we shall see later, ‘the place protected from demons’.

It is thus this will to perfect the world, to create a better world, that gave meaning to the art of pre-Islamic gardens in Iran. It serves as a means of purification and transformation of the earthly expanse into a transcendent and holy place.Footnote34 In other words, the act of building a garden expressed the veneration of celestial beings, giving rise to holiness and strengthening the Mazdean lawFootnote35; one may recall that it is also the aspiration to transcendence that underlies the spatial organization of Persian gardens in the image of the world.

By embodying sovereignty and royal power, the gardens appear as transcendent places from a political point of view. Indeed, we have seen that they are considered as the khshathra of the king, that is to say, as royal territory from which the sovereign observes and governs the earthly world. In this sense, it seems appropriate to define the gardens of ancient Persia as ‘high places’, which connotates height, or highness, both in socio-political terms, as the elevated place of someone, and in mystico-religious terms, designating a holy place. Moreover, the idea of height is especially appropriate here, as the gardens are also elevated in the literal sense; the land is as physically elevated as it is symbolically valued.

As Gilbert Durand has shown, this correlation between verticality and valorization is not a coincidence.Footnote36 The ascending direction refers on the one hand to the path toward the light and thus toward illumination and self-purification and, on the other hand, to the feeling of sovereignty and mastery of the universe. This axis is, hence, valorizing, as underlined by Bachelard, who stated that any verticalization is valorization.Footnote37

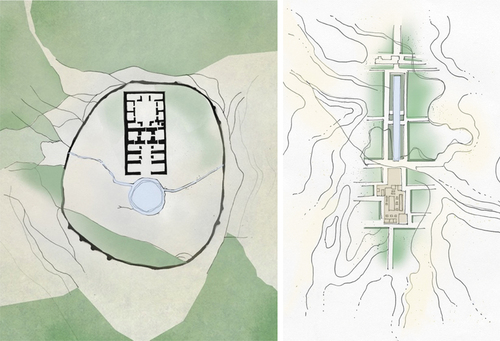

To recreate this sense of elevation, Persian kings tended to build their palaces on the highest point of the site, thus offering commanding views of the surrounding space. Conversely, the main entrance to the garden was usually located at the bottom of the site. From there, reaching the palace meant moving upward, toward the seat of power. But the most important embodiment of verticality in traditional royal architecture is undoubtedly the takht, a term meaning ‘throne’ and ‘mountain’, which refers to ‘the elevated, rectangular platform or socle’Footnote38 on top of which the royal palaces were built (). Such platforms, symbolizing this ascending verticality, can be found at Takht-e Jamshid (Jamshid’s throne), Qasr-e Shirin, Firouzabad (), Taq-e Bostan and Takht-e Soleyman ().Footnote39

FIGURE 5. The expression of takht in Falak-ol-Aflak castle in Khorramabad (left) and Chogha Zanbil Ziggurat in the Khuzestan province (right). These images are drawn by Claudia-Emma Farley-Dabis. © Shabnam Rahbar.

FIGURE 6. Takht-e Soleyman (left) and Firouzabad Palace Garden (right). These images are drawn by Claudia-Emma Farley-Dabis to show the contrast between the orderly space of the garden and the disorderly nature of its surroundings and are based on: Mehdi Khansari, Minouch Yavari, and M. R. Moghtader, op.Cit., pp. 46 and 55. © Shabnam Rahbar.

All in all, it is through this great correlation between productive activities and spirituality that the reality of Persian gardens must be understood. They embodied a land that was cosmicized and charged with certain fundamental values of traditional Iranian society, such as purity, holiness and wisdom. In this way, they manifested as a world where all things were, in Avestan terms, ‘in goodness’ and ‘in beauty’.

Complementarity

The term ‘complementarity’ designates a type of interdependence between two phenomena that is characterized by reciprocity, meaning that the two phenomena determine or cross-fertilize each other. The relationship between the Persian garden and its environment is quite clearly one of reciprocity. To show this, I examine two complementary studies: first, I explore the possible meanings of the word pairidaeza and the realities it can designate, and then I examine the essence of the Persian garden on the basis of the dualistic system underlying the onto-cosmology of the ancient Persians.

Persian garden, pairidaeza and logic of diairesis

In Achaemenid times (556−330 BC), the term pairidaeza signified garden; and gave rise to the Greek paradeisos, the Latin paradisus, the Arabic firdaws, pardîs (پرديس) in modern Persian, as well as the terms paradis (French) and paradise (English).

The term is composed of two words: pairi and daeza. According to the Dehkhoda Dictionary, the Avestan pairi means ‘periphery’, ‘around’ (accounting for the Greek ‘peri-’), while daeza means ‘to wall’ and ‘to build’ and also refers to the rampart, the enclosure, the wall. Put together, these two words then evoke an enclosure around something. In this sense, pairidaeza is defined as an enclosure and a closed space.Footnote40

However, such a definition of pairidaeza remains unsatisfactory insofar as it is based on an objective approach describing rather the physical space of the garden. In other words, it does not tell us what the ontological reality of the garden was for the ancient Persians. In an effort to fill this gap, I offer an alternative interpretation of the meaning of the word pairi — one based on a close inquiry into the term pairikâ and its relationship with the term pairidaeza — with a view to identifying other aspects of the reality of the Persian garden that might be reflected by the term pairidaeza.

In the Avesta, pairikâ are described as originally evil female creatures. An inquiry into the etymology of the term pairikâ reveals that it can be broken down into two parts: on the one hand the word pairi- and on the other hand -kâ. The first component, pairi-, has been the subject of many interpretations. According to Güntert, the term comes from the Indo-European root pelê- (to fill); according to Sarkārātī, from per- (to create, to support); and according to Geiger, from the Sanskrit parakīya (belonging to others, foreigner), whose root is para-, which means ‘prior in time’, ‘more distant in space’, ‘that which comes after’, ‘other’, ‘different’ or ‘hostile’.Footnote41 A priori, these very divergent interpretations do not allow us to identify a clear and univocal meaning of the word pairi-.

As to the meaning and role of the Indo-Iranian suffix kâ-, there is little ambiguity. In his article ‘The K-Suffixes of Indo-Iranian’, Franklin Edgerton has dealt extensively with this term. Examining this suffix in the Rig-Veda and Avesta texts, Edgerton associated it with four categories of meaning:

a) as a primary suffix, most often giving active verbal force; b) as a secondary suffix, forming nouns and adjectives of likeness (masyâka, man) and characteristic (nipasnaka, envious, i. e. characterized by envy; c) as a diminutive (aparanayuka, minor, child) and pejorative suffix (developed out of the preceding) (pairikâ, enchantress); d) as a secondary suffix forming adjectives of appurtenance and relationship.Footnote42

For her part, Claudia Ciancaglini points out that the only general semantic value that can be attributed to the suffix -kâ is the expression of a relationship that could be either similarity, degradation or belonging, depending on the meaning of the term it completes, the context and the overall morphological system of each language in which this suffix appears.Footnote43 She added that the evil connotation of -ka in the Avesta seems to be confirmed by the fact that it is often found in terms designating sins or diseases. This finding has likewise been confirmed by Jacques Duchesne-Guillemin, who, highlighting the four terms constructed with the suffix ka- in Yasht V, 95, says: ‘It is probably not by chance that all four (…) describe demonic beings. The suffix ka- seems to give these formations an unfavorable meaning’.Footnote44

Assuming that kâ- in the word pairikâ is a pejorative suffix that amplifies the quality or characteristic carried by pairi-, one can assume that the latter designates a demonic being, the other or the enemy. As we can see, the key to understanding the word lies in the first of the two terms we have studied so far: pairi-. I choose here to follow Geiger’s interpretation, which links this word to the Sanskrit para-, which means ‘other, opposite, hostile, the enemy’ but also ‘more distant in space’. I can, hence, put forth the hypothesis that the word pairi- designates both the periphery and the demonic being, two notions that are closely linked in traditional societies. According to Eliade:

One of the outstanding characteristics of traditional societies is the opposition that they assume between their inhabited territory and the unknown and indeterminate space that surrounds it. The former is the world (more precisely, our world), the cosmos; everything outside it is no longer a cosmos but a sort of ‘other world’, a foreign, chaotic space, peopled by ghosts, demons, ‘foreigners’ (who are assimilated to demons and the souls of the dead).Footnote45

We may, therefore, assume that pairi does not simply refer to the physical space that extends beyond the borders of the garden but to a foreign and unknown land populated by evil spirits (pairikâ). In other words, it represents the wilderness that surrounds the controlled and ordered nature of the garden ().

Let us now return to the term pairidaeza. In view of the above, there seem to be two possible ways of interpreting pairidaeza: 1) space surrounded by a wall, expressing the idea of an enclosed place, and 2) space separated from its surroundings, expressing the idea of a transcendental space that is distinguished from its surroundings by the wall. In both cases, however, we can emphasize the idea of separation, carried by the term daeza, rather than that of delimitation, and this considering the demonic connotation of the word pairi-.

The act of walled-in space can be read as an act of dividing the space between two worlds, evil and good, but also as an act of protecting against evil spirits. The wall, intended to protect the interior space from the wild and demonic unknown that extends outside, plays a strongly symbolic role. In this way, we are touching on a major characteristic of sacred and pure spaces, understood to presuppose above all a separation from the profane world. Hence, I propose to understand by pairidaeza the separated, protected and sanctuarized space rather than a simple closed space.

Similarly, this notion of distinction is a clear reflection of Zoroastrian cosmogony,Footnote46 which is fundamentally based on the primordial dualism between two cosmic principles — good and evil — through two opposing Mainyu (spirits): Spenta Mainyu, the holy spirit who dwells in the height of light, and Angra Mainyu (or Ahriman), the evil spirit who dwells in an abyss of darkness. The former promotes birth, growth and purity; the latter represents crime, disease and death. Between these two spirits a cosmic struggle takes place, for which the Earth is the stage. On the surface of Earth, these two spirits coexist, incarnating themselves through the beings and the earthly, terrestrial phenomena. Thus, the pastoral, settled person, ‘useful’ animals, cultivated land, fresh water and the ‘vivifying wind’ belong to the domain of Spenta Mainyu, while the nomadic man, ‘harmful animals’, desert land, salt water and the violent winds represent Angra Mainyu.

The studies of Gilbert Durand show well that this vision of the world is inspired by an antithetical philosophical system that is underpinned by the logic of diairesis: things are defined in juxtaposition to their opposite, good is understood in relation to evil, the day is affirmed in relation to the night, and light is manifested in relation to darkness. According to this logic, making sense of beings, things and even places implies dividing, distinguishing and confronting. This pattern also organizes the Persian garden: as an ordered, cultivated and geometric place, it is partly defined by what it is not, which would be its formless surrounding space. Indeed, wild and infertile spaces are perceived as a profane and impure world, animated by evil powers, and it is precisely in contrast to this that the garden was built as a high place. Thus, the sacredness of the royal gardens is constructed in close connection with the uninhabited and undeveloped space that surrounds them. In the same vein, the geometric organization of the garden draws its deep meaning, that of a cosmic order, in opposition to the external world, considered as indeterminate and chaotic … and vice versa.

Overall, it is within this co-belonging to two opposite worlds that the Persian garden acquires its profound significance. While it is true that there are differences, and even oppositions, both physical and semantic, between the garden and the space that surrounds it, and that these exclude each other, it is also true that they define each other. In other words, they are two distinct realities that need each other in order to be grasped as such.

Conclusion

Starting from the definition of landscape as a trajective reality, that is, a reality formed in concrescence with the things that surround it, the challenge of this article was to show the trajections through which Persian gardens and their environment are inter-defined. Three types of trajection are identified: analogy, enrichment and complementarity. Analogy refers to the art of shaping according to Iranian society’s representations and conceptions of the world. Enrichment shows that the creation of the garden is more than an art of formal composition: it participates in the semantic and symbolic deployment of the place. Finally, complementarity implies thinking of the garden not as an intrinsic object but rather as a reality that makes sense through a series of exchanges and transitions with its surrounding environment. These three trajections highlight a reciprocal adequacy between the garden and its milieu in a way that transcends the notion of a unilateral relationship that presupposes the pre-eminence of one over the other. The result is a designed landscape that is inseparable from the environment in which it is located, and which only has meaning within its own geographical, historical and cultural context. At the same time, it participates considerably in the constitution and blossoming of the Iranian world.

Moreover, the establishment of such relationships is particularly topical and relevant with regard to some of the major challenges facing landscape architects. Firstly, ‘analogy’ puts forward an approach to design according to which a landscape project draws its definition, form and materials from the systems of ideas, values and collective beliefs of the society concerned. In fact, it favors the creation of embedded works, that is to say, landscapes that are intrinsically specific to the society that conceives and uses them and that respect each milieu in its locality, singularity and historical and cultural particularities. Analogy therefore proposes a design process that is antithetical to the ‘clean slate’ attitude of modernism, where architects, landscape architects, urban designers and planners design their work from boilerplate recipes and rules that are applied independently of situations and places.Footnote47 Indeed, this is how modernist projects have contributed to the abolition of the local identity of places and, by doing so, to the emergence of homogeneous spaces.Footnote48 Establishing analogies is therefore a principle very close to the concerns of contemporary landscape architects who are looking for creative ways to counteract the standardization of territories and the erasure of the cultural specificities and identities of human environments.Footnote49

Second, ‘enrichment’ emphasizes the importance of creating landscapes that carry meaning. In fact, it aims to encourage work that is not only about the spatial organization of the place but that opens it up to new horizons of the world to be discovered and experienced. This point here is to consider the practice of landscape architecture as an act that transforms space, both materially and immaterially, into a place rich in meanings, qualities and values. This approach to landscape design allows us to address a major problem of the twenty-first century, namely: the advent of flat and insignificant landscapes that, more often than not, fail to deliver meaning to the people who inhabit them. Augustin Berque describes these landscapes as ‘decosmicized’ spaces, that is, spaces reduced to a neutral receptacle and which are hardly differentiated from one another except by their functioning, and which express no cosmicity (values of the society concerned).Footnote50 According to Catherine Grout, we are witnessing the disenchantment of the everyday,Footnote51 while Jean-Marc Besse, for his part, speaks of this crisis of the contemporary city in terms of ‘poverty in the world’.Footnote52 By considering the landscape project as a process of opening up and unfolding a world, ‘enrichment’ is therefore a principle that allows us to participate in the ‘recosmicization’ and re-enchantment of human spaces. Isn’t this exactly what contemporary landscape architects are looking for? To create familiar landscapes, places that have meaning for those who use them and that give us the opportunity to see and feel a certain cosmicity?Footnote53

Finally, ‘complementarity’ favors an ecosystemic (or relational) approach of the project according to which landscape is thought of and conceived not as an object distinct from its environment but as a reality which takes shape through a continuous, ongoing dialogue with the constituent elements of its context. Here, the concern of the landscape architect is less with the landscape work in itself and its composition than with its relationship with the environment in which it is inserted. Thus, ‘complementarity’ represents a principle that makes it possible to address an important issue of contemporary cities, namely: the fragmentation and loss of connection between the different elements that make up the city; between natural environment and social environment, between urban units, between an infrastructure and its context, between different uses, between citizens and urban rhythms, and so on. Many scholars and practitioners emphasize the importance of ‘articulating what is separate and connecting what is disjoint’Footnote54 in order to promote continuity and access, social relations and daily life, meaning and local identity and so on. By establishing transitions and passages at the heart of the project, the principle of complementarity offers the landscape architect the possibility of working not only within the limits of site but between the borders that separate it from its context, with a view to reweaving the links between them.

In light of all of the above, I conclude that analogy, enrichment and complementarity represent concrete and practical orientations that are at the heart of the current concerns of landscape architects. Thus, their analysis and identification not only contribute to the advancement of knowledge about the art of gardening in Iran but also offers new possibilities for thinking and defining landscape design.

The present study focused only on the trajections that existed between the garden and the worldview of the ancient Persians. However, there were also trajections at the ecological level. A thorough analysis of the interdependence between Persian garden design and the climatic, hydrological, geological and biological characteristics of the Iranian regions would be very enriching.Footnote55 This could not only offer a more complete view of the trajective reality of Persian gardens but also open up avenues of reflection about a harmonious design with nature. In fact, the study of these places as an imprint of the available natural resources as well as of the environmental constraints of its milieu, and as a matrix of their ecological enhancement, could contribute to answering a series of questions on eco-design, such as: How might we integrate human interventions and ecosystems in a coherent and interactive network? Even more, how might we establish symbiotic relationships in which both support and enhance each other?

Finally, beyond seeking to present Persian gardens from an ontological perspective, this study also wishes to invite landscape architects to be more attentive to the cross-fertilization of worlds, places, words and actions in which landscape works can amply participate

Acknowledgments

This paper is part of the doctoral thesis La terre du point de vue paysager : enjeux esthétiques, enjeux éthiques, enjeux écologiques under the direction of Professor Augustin Berque, and presented in May 2019 at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales of Paris (EHESS). I warmly thank Mr. Berque for his scientific support and for allowing me to discover my relational being and its existential link with space.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Augustin Berque, Poetics of the Earth: Natural History and Human History (London; New York: Routledge, 2019), 107.

2. Berque, 129.

3. Augustin Berque, “Comment Souffle l’esprit Sur La Terre Nippone [How the Spirit Blows on the Japanese Land],” in Colloque Spiritualités Japonaises. (Bruxelles, Palais des Académies, 2011), http://ecoumene.blogspot.com/2012/01/comment-souffle-lesprit-sur-la-terre.html.

4. See for example Christophe Girot, The Course of Landscape Architecture: A History of Our Designs on the Natural World (New York, NY: Thames and Hudson, 2016); Elizabeth Barlow Rogers, Landscape Design: A Cultural and Architectural History (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2001); Geoffrey Alan Jellicoe and Susan Jellicoe, The Landscape of Man: Shaping the Environment from Prehistory to the Present Day, Third Edition, Expanded and Updated (New York, N.Y: Thames and Hudson, 1995); Albert Forbes Sieveking, Sir William Temple Upon The Gardens of Epicurus, with Other Xviith Century Garden Essays (London: Alpha Edition, 2020); Thomas Browne, The Garden of Cyrus (Scotts Valley: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2016); Albert Forbes Sieveking, Gardens Ancient and Modern An Epitome of the Literature of the Garden-Art (London: J. M. Dent & Co, 1899).

5. See for example Mehdi Khansari, Minouch Yavari, and M. R. Moghtader, The Persian Garden: Echoes of Paradise (Washington, DC: Mage, 1998); Mohammad Gharipour, Persian Gardens and Pavilions: Reflections in History, Poetry and the Arts (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020); Nasim Yazdani and Mirjana Lozanovska, “The Design Philosophy of Edenic Gardens: Tracing ‘Paradise Myth’ in Landscape Architecture,” Landscape History 37, no. 2 (2016): 5–18; Mohammadsharif Shahidi et al., “A Study on Cultural and Environmental Basics at Formal Elements of Persian Gardens (before & after Islam),” Asian Culture and History 2, no. 2 (2010): 133–47.

6. See for example Khansari, Yavari, and Moghtader, The Persian Garden: Echoes of Paradise; Gharipour, Persian Gardens and Pavilions: Reflections in History, Poetry and the Arts; Yazdani and Lozanovska, “The Design Philosophy of Edenic Gardens: Tracing ‘Paradise Myth’ in Landscape Architecture”; Shahidi et al., “A Study on Cultural and Environmental Basics at Formal Elements of Persian Gardens (before & after Islam).”

7. For example, we can see that historians of gardens often refer in their studies to the Chaharbaq pattern or to the term Pairidaeza in order to shed light on the origin of the spatial organization of Persian gardens.

8. On this subject, see Nasrine Faghih and Amin Sadeghy, “Persian Gardens and Landscapes,” Architectural Design 82, no. 3 (2012): 38–51, https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.1403; James W. P. Campbell and Amy Boyington, “Fountains and Water: The Development of the Hydraulic Technology of Display in Islamic Gardens 700–1700 CE,” Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes 38, no. 3 (July 3, 2018): 247–67, https://doi.org/10.1080/14601176.2018.1452827.

9. Although Zoroastrianism was not the only religion in pre-Islamic Iran, it was nevertheless dominant during the Achaemenid (approximately 556−330 BC) and Sassanid (224 − 651) dynasties, two decisive periods in Persian history. It was therefore the dominant conceptual framework of Iranian thought, even representing a typical form of Iranian religions. Alexandros-Faidon Lagopoulos, Urbanisme et Sémiotique Dans Les Sociétés Préindustrielles (Paris: Anthropos, 1995).

10. The Avesta originally contained twenty-one texts, of which only four have been handed down to us. The main parts of the Avesta are the Yasna, Yashts, Vendidad, Visperad, Khordeh Avesta and Siroza. When quoting from the Avesta in English, I have used the translation by L. H. Mills (from Sacred Books of the East, American Edition, 1898) available at www.avesta.org

11. Chaharbagh literally means ‘the fourfold gardens’; chahar meaning ‘four’ and bagh ‘garden’. In the Encyclopedia Iranica, chaharbagh is also defined as ‘a rectangular garden divided by paths or waterways into four symmetrical sections’. David Stronach, “ČAHĀRBĀḠ,” in Encyclopedia Iranica, n.d., https://iranicaonline.org.

12. See for example David Stronach, “Parterres and Stone Watercourses at Pasargadae: Notes on the Achaemenid Contribution to Garden Design,” The Journal of Garden History 14, no. 1 (March 1994): 3–12, https://doi.org/10.1080/01445170.1994.10412493; Faghih Nasrin, “« Chaharbagh, Mesal Azalî Baghhaye Tamadon Eslamî» [Chahar Bagh, the Archetypal Garden of Islamic Civilization],” in « Bâgh Iranî: Hekmat Kohan, Manzar Jadîd » [Persian Garden: Ancient Wisdom and the New Landscape], ed. Mohammad Reza Javadi Javaherian, Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (Tehran, 2004), 26–52.

13. On this subject, see the studies by Mahvash Alemi, Seyed Amir Mansouri and Vahid Heydarnattaj.

14. On this subject, see Ann K.S. Lambton, Landlord and Peasant in Persia: A Study of Land Tenure and Land Revenue Administration (London: Oxford University Press, 1953); Hans E. Wulff, The Traditional Crafts of Persia: Their Development, Technology, and Influence on Eastern and Western Civilizations (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1966); Michael Bonine, “The Morphogenesis of Iranian Cities.,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 69, no. 2 (1979): 208–24; Mohammad Karim Pirnia, ‘« Baghhaye Irani » [Persian Gardens]’, Abadi, no. 15 (1994): 4–9; Mojtaba Ansari and Darab Diba, ‘« Bagh Irani » [Persian Garden]’, in Histoire of Architecture and Urbanism in Iran (Tehran: Cultural Heritage Organization, 2004), 25–42.

15. Solmaz Mohammadzadeh Kive, “The Other Space of Persian Garden,” Polymath: An Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences Journal 2, no. 3 (2012): 86–96; Augustin Berque, Écoumène: introduction à l’étude des milieux humains [Ecumene: introduction to the study of human milieux] (Paris: Belin, 2010); Gilbert Durand, The Anthropological Structures of the Imaginary, trans. Judith Hatten and Margaret Sankey (Mount Nebo: Boombana Publications, 1999).

16. This center need not necessarily correspond to the geometric center of the piece of land.

17. Lagopoulos, Urbanisme et Sémiotique Dans Les Sociétés Préindustrielles, 241, our translation.

18. Piotr Bienkowski and Alan Millard, Dictionary of the Ancient Near East (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000), 99.

19. Vast vaulted porch open on the front by a large arch.

20. Porch with columns.

21. Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion (San Francisco: HarperOne, 1968), 52.

22. Eliade, 45.

23. Beyond the garden space, the triple characteristic I have highlighted — orthogonality, centrality and openness to the four cardinal directions — is also found in the royal cities of ancient Persia. Hence, insofar as this organization appears at different scales of space, it is a constant element of design in ancient Persia. For more information on the semiotic significance of pavilion in Persian Gardens, see Gharipour, Persian Gardens and Pavilions: Reflections in History, Poetry and the Arts.

24. For the meanings of this term, see Hossein Soltanzadeh, A Brief History of the City and Urbanization in Iran ; Ancient Era to 1976 (Tehran: Chartaq, 2011), 14–16; MOstafa Younesie, “Comparative Greek Persian Phraseology: Xsathra and Αναξ” (6th European Conference for Iranian Studies, Vienna, 2010), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1722496.

25. Gathas are seventeen songs attributed to Zoroaster and constitute the first part of the Avesta.

26. Zoroastrianism is a monotheistic religion in which Ahura Mazda is the only creator of the Sky and the Earth. Before becoming the supreme god, Ahura Mazda was one of the divinities of Mazdeism, which is a pre-Zoroastrian religion. This religion was later reformed by Zoroaster, the founder of Zoroastrianism, whereby Ahura Mazda became the only god.

27. On this subject, see Heidi A. Walcher, “Between Paradise and Political Capital: The Semiotics of Safavid Isfahan,” in Middle Eastern Natural Environment, Lessons and Legacies, Yale University, (New Haven, 1998), 330–48.

28. Definition of enrichment in Merriam-Webster’s dictionary.

29. Henry Corbin, Spiritual Body and Celestial Earth: From Mazdean Iran to Shi’ite Iran (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1989), 37.

30. David Leeming, The Oxford Companion to World Mythology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 29.

31. Corbin, Spiritual Body and Celestial Earth: From Mazdean Iran to Shi’ite Iran, 37.

32. Paula R. Hartz, Zoroastrianism (New York: Chelsea House Pub, 2009), 8.

33. For example, in sections XXIII−XXVII of chapter three of the Vandidad, devoted to acts pleasing to the Earth, when Zoroaster asks Ahura Mazda: ‘Who is the fourth who makes the earth taste great joy?’, the latter responds, ‘He who makes the most grain, herbs and fruit-bearing trees grow’; ‘Or he who waters the dry land and dries up the wet land’; ‘For there is no joy for land that lies uncultivated for a long time’. Similarly, when Zoroaster asks Ahura Mazda, ‘What is it that makes Mazdean law flourish?’, Ahura Mazda says, ‘It is the cultivation of wheat (practiced) with eagerness’; ‘He who produces wheat produces holiness’; “He develops the Mazdean law’; ‘He strengthens this Mazdean law. He nourishes this Mazdean law”.

34. Through the study of a series of historical texts and archaeological documents, Vahid Heydarnattaj arrives at a similar conclusion: pre-Islamic gardens possessed a sacred character. Vahid Heydarnattaj, “Bâgh Iranî”[Persian Garden] (Tehran: Centre de Recherche Culturelle, 2010).

35. This is why the cultivation of plants was of great importance in the court of the Achaemenid kings, as Xenophon (430-355 BC) indicated in his work Oeconomicus about the Persian king Cyrus II (known as Cyrus the Great). See J. Donald Hughes, “Europe as Consumer of Exotic Biodiversity: Greek and Roman Times,” Landscape Research 28, no. 1 (2003): 22; Marie Luise Gothein, A History of Garden Art : From the Earliest Times to the Present Day (Cambridge: Cambridge University press, 2014), 40; Walcher, “Between Paradise and Political Capital: The Semiotics of Safavid Isfahan,” 342.

36. Durand, The Anthropological Structures of the Imaginary.

37. Gaston Bachelard, Air and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Movement (Dallas: The Dallas Institute Publications, 1988), 60.

38. Nader Ardalan and Laleh Bakhtiar, The Sense Of Unity :The Sufi Tradition in Persian Architecture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979), 70, http://archive.org/details/the-sense-of-unity.

39. This valorization between high and low still structures everyday domestic spaces in Iran, to this day. For example, most living rooms are symbolically differentiated and divided in two: the entrance, the place of arrival and first moments, is called ‘the bottom’ of the room, while the part farthest from the door is designated as ‘the top’. Every host must place his guests in the most noble part of the room, i.e., in the upper part of the living room, while he himself must absolutely avoid taking a seat there, as this would show a lack of respect toward the guests.

40. For example see Yazdani and Lozanovska, “The Design Philosophy of Edenic Gardens: Tracing ‘Paradise Myth’ in Landscape Architecture,” 5–18; Muhammad A. Dandamaev and Vladimir G. Lukonin, The Culture and Social Institutions of Ancient Iran, trans. Philip L. Kohl and D. J. Dadson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 143; Anne van Erp-Houtepen, “The Etymological Origin of the Garden,” The Journal of Garden History 6, no. 3 (1986): 227–31.

41. Farrokh Hajiani and Mohsen Mahmoudi, “A Comprehensive Survey on the Etymology of Three Avestan Words’:Pairikā’’,Xnąϑaiti-’and’Gaṇdarəβa-’’, International Journal of Language Studies 12, no. 2 (2018): 116–18.

42. Franklin Edgerton, “The K-Suffixes of Indo-Iranian. Part I: The K-Suffixes in the Veda and Avesta,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 31, no. 3 (1911): 306.

43. Claudia Ciancaglini, “Claudia. Outcomes of the Indo-Iranian Suffix-Ka- in Old Persian and Avestan’, in Dariosh Studies II. Persepolis and Its Settlements: Territorial System and Ideology in the Achaemenid State, ed. Gian Pietro Basello and Adriano V. Rossi, Università degli Studi di Napoli “L’Orientale” (Napoli, 2012), 91–100.

44. Jacques Duchesne-Guillemin, Études de Morphologie Iranienne. I. Les Composés de l’Avesta. (Studies of Iranian Morphology. I. The Compounds of the Avesta. (Liège: Presses universitaires de Liège-Librairie Droz, 1936), 32, our translation.

45. Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion, 29.

46. On this subject, see James W. Boyd and A. Crosby Donald, “Is Zoroastrianism Dualistic Or Monotheistic?,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 47, no. 4 (1979): 557–88; Philip G. Kreyenbroek, ‘On Spenta Mainyu’s Role in the Zoroastrian Cosmogony’, Bulletin of the Asia Institute 7 (1993): 97–103; Moojan Momen, The Phenomenon of Religion: A Thematic Approach (Oxford: Oneworld, 1998); Philip G. Kreyenbroek et al., “Cosmogony and Cosmology,” in Encyclopaedia Iranica Online, 1993.

47. Brian Irwin, “Abstract City: The Phenomenological Basis for the Failures of Modernist Urban Design,” Journal of Aesthetics and Phenomenology 6, no. 1 (2019): 41–58; Lincoln Williams and Vishanthie Sewpaul, ‘Modernism, Postmodernism and Global Standards Setting’, Social Work Education 23, no. 5 (2004): 555–65.

48. Edward Casey, The Fate of Place: A Philosophical History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013).

49. Andrea Kahn and Carol J. Burns, eds., Site Matters. Strategies for Uncertainty through Planninatters. Strategies for Uncertainty through Planning and Design (London: Routledge, 2020).

50. Augustin Berque, “Cosmiser à Nouveau Les Formes ?,” Mésologiques. Études Des Milieux, 2016, http://ecoumene.blogspot.com/2016/06/cosmiser-nouveau-les-formes-augustin.html.

51. Catherine Grout, Le sentiment du monde: expérience et projet de paysage [The feeling of the world: experience and landscape project], Collection Essais (Bruxelles: La Lettre volée, 2017).

52. Jean-Marc Besse, La nécessité du paysage [The Necessity of the Landscape] (Marseille: Parenthèses, 2018), 27, our translation.

53. This is what the authors of Site Matters propose, or Verschaffel in his article ‘Loci Amoeni: The Meaning and Aesthetics of Sites’. Kahn and Burns, Site Matters. Strategies for Uncertainty Through Planning and Design; Bart Verschaffel, “Loci Amoeni: The Meaning and Aesthetics of Sites,” Architectural Theory Review 25, no. 3 (2022): 282–91.

54. Didier Rebois, ed., Reconnections. Europan 11 Results (Montreuil: Europan, 2012), 241.

55. See, for example, Mohamed Yusoff Abbas, Nazanin Nafisi, and Sara Nafisi, “Persian Garden, Cultural Sustainability and Environmental Design Case Study Shazdeh Garden | Elsevier Enhanced Reader,” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 222 (2016): 510–17, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.05.142.; Faghih and Sadeghy, “Persian Gardens and Landscapes.”