Abstract

A research study conducted by six partners demonstrated that, despite the tangible benefits of integrating co-creation into design processes (as well as other areas), there are still noticeable gaps and deficiencies in the knowledge of how to implement the process of co-creation and co-design—both in many professional design teams and in the area of non-formal learning. This paper focuses on the process of co-creation and the findings obtained in the course of preparing the new curriculum and the accompanying handbook. The aim of the project was to co-create a new co-creation curriculum, which will allow vocational education institutions and creative industries organizations to provide their students and employees with the knowledge they will need to apply the participatory collaborative and co-creation process in their future professional practice.

Systematically Supporting the Collective Creativity of Others

We will see the emergence of new domains of collective creativity that will require new tools and methods for researching and designing. We will need to provide alternative learning experiences and curricula for those who are designing and building scaffolds to support the collective creativity of others. (Sanders and Stappers Citation2008, 16)

These words are an excellent summary of the purpose and the aim of the international study Co.Create, as well as its results, represented by the following documents: The Co-Design Best Practice Report, The Co-Create Curriculum for Creative Professionals, The Co-Create Handbook for Creative Professionals, and a hands-on guide accompanied by video tutorials The Co-Design Essentials – Collective Creativity: How to Learn Co-Creation. All of the above was created with the aim of filling the gap that, by the time the project commenced in 2016, had yet to be satisfyingly bridged, despite the bold prediction from the 2008 article. This despite the fact that, as Sanders and Stappers point out, this topic is not new in either design education or the professional field of design in the wider sense (ibid.). For a while now, numerous universities and professional associations have increasingly been introducing and carrying out various seminars, workshops, classes and programmes focusing on co-design, participatory, ethnographic and inclusive design (Coleman Citation1994; Manzini and Jegou Citation2003; Černe Oven and Predan Citation2013; Nova Citation2014; Sanders and Stappers Citation2008, Citation2014; Nielsen and Birch Andreasen Citation2015). Despite that, the study has shown that there remains a certain deficit in the area in question, namely ‘alternative learning experiences and curricula’ deliberately targeting vocational education while ‘[supporting] the collective creativity of others’; this leaves ample space for further development.

Before we continue, it is important to point out that in our interpretation of the terms co-creation and co-design, both in the study and in this text, we adhered to the definition offered by Sanders and Stappers, according to whom co-creation refers to ‘any act of collective creativity’ (Citation2008, 6) and is often used as an umbrella term for co-design and participatory design, whereas co-design refers ‘to the creativity of designers and people not trained in design working together in the design development process’ (ibid.). When it comes to the process of participatory design, our study focused primarily on the significance and role of mutual learning and on the ways of and capabilities for collectively responding to changing knowledge. As explained by Schön (Citation1983) and Simonsen and Robertson, participatory design is ‘a process of investigating, understanding, reflecting upon, establishing, developing and supporting mutual learning between multiple participants in collective “reflection-in-action” (Citation2013, 2).

Accordingly, the study presented in this paper focuses on the European research project carried out by six partners (Creative Region Linz & Upper Austria, Austria; Kunstuniversität Linz, Austria; Creative Industries Kosice, Slovakia; University of Ljubljana, Academy of Fine Arts and Design, Slovenia; Deusto University, Spain; European Creative Business network (ECBN), The Netherlands).Footnote1 While building on the existing knowledge in the field, the study also used observation, in-depth interviews and workshops to establish new findings, rigorously testing them along the way (with potential end-users, stakeholders and facilitators) and iterating them as needed (building on the user evaluation methodology tried and tested techniques were employed). The aim of the project was to create a new curriculum for co-creation which will allow vocational education institutions and creative industries organizations to provide their students and employees with the knowledge they will need to apply in the participatory collaborative and co-creation process in their future professional practice. In other words, the intent was to prepare, in the course of research and the project development, materials that would combine cutting edge design theory with hands-on knowledge and examples taken and distilled from current co-design best practice.

The remainder of this paper presents a co-creation case study in which six partners, together with a selection of stakeholders, used the methodology and tools of co-design to co-write a curriculum and an accompanying handbook for vocational education institutions and design professionals. The paper delineates the process of co-developing training materials in order to implement co-designing in professional practice. It also presents and examines a specific process and the outcomes of the co-development of the materials.

Approaches to Analysis

As noted previously, co-design and participatory design as potential education approaches are topics that have been discussed in the field of design for quite a while (Arnstein Citation1969; Cross Citation1971; Jones 1972; Mächtig Citation1976), but there has recently been a noticeable resurgence of interest (Clarkson and Coleman Citation2015; Manzini Citation2015; Peterlin et al. Citation2015; Černe Oven and Predan Citation2016; Jansen and Pieters Citation2017; Smith and Iverson Citation2018). The reason for the continuous relevance of the approach—as well as its persistent elusiveness—likely lies in the fact that ‘there is no universal participatory design process that can be transferred from one situation to the next’ (Luck Citation2018). Despite that, the numerous practices, methods and tools can be used as a basis for establishing an operating framework and instructions for tackling the individual steps in the process of collective co-creation and co-design and how to continually adapt them to the situation at hand.

We decided to put this into the context of a study characterized by three focuses that we selected beforehand. The first focus involved being attentive from the outset to how, in various contexts, participants in the co-design process systematically or spontaneously use, develop and adapt the diverse tools, methods and techniques. This proved vital for building an understanding of the methods of co-creation, as well as identifying effective approaches for stimulating collective creativity and the possibilities for co-creating knowledge, as well as its subsequent integration. The latter—co-creation and integration of new knowledge—is particularly important for the co-design process, since if ‘actors are not able to create and integrate knowledge, then they will not be able to design a new product’ (Kleinsman and Valkenburg Citation2008, 371).

In order to acquire new knowledge and investigate this new knowledge empirically, the necessity of understanding the diverse nature of co-design was chosen as the second key focus of the project. We deliberately selected for analysis the study cases that represented different settings of creative industries and design, as well as the different scopes of co-design. The third key focus of the project emerged from our decision to prepare materials suitable for use in non-formal learning and education. This decision feels especially sensible in light of our entry into the area of collaborative design activities, since according to the Council of Europe (listed on its website https://pjp-eu.coe.int/en/web/youth-partnership/non-formal-learning), it is the non-formal learning that commonly emphasizes ‘the learner's intrinsic motivation, voluntary participation, critical thinking and democratic agency. It is widely acknowledged and recognized that non-formal learning provides unique learning opportunities to millions of young Europeans on a daily basis’.

On the basis of the chosen focuses and the steps that had been accomplished, the findings we obtained in the process were first analysed and compared within the partner consortium and then repeatedly validated through focus groups. These consisted of a selection of stakeholders (creative professionals from various professions with practical experience in co-creation, co-design, participatory design and collaboration). This way, during the research, we—together with the broader group of participants—managed to successfully build the shared understanding (Kleinsman and Valkenburg Citation2008) of the subject and its processes as initially outlined.

Three years later, these validations, tests and iterations resulted in the documents presented later in the text. These documents are intended for organizations interested in implementing collaborative design training activities and improving collaborative design skills. Their primary purpose is to help organizations organize hands-on sessions and workshops in co-design. The handbook, together with the curriculum, the learning materials and the best practices report, provides a set of up-to-date educational resources for organizations (consortium-developed methodology especially for implementation in creative industries), vocational education institutions and creative professionals, as well as students interested in co-design.

The Empirical Study, the Research Methods Used and the Findings

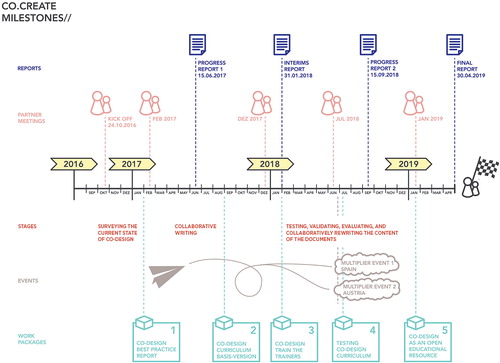

In order to achieve our objectives, we divided the project into three key stages. In the first stage, we set out to survey the current situation in the field of co-design. The results of the first round of focus group sessions and the knowledge gained after the elaboration of the best practice report proved immensely helpful in grounding the objectives of the second phase: co-creating and co-writing the curriculum and handbook. What most distinguished the second phase of the project in the process of creating the two documents was a series of workshops. In addition to validating the content of the documents that were being created, the workshops also served to validate the process in which the trainer, a subject-matter expert, trains other employees and simultaneously teaches them how to train others in the use of the subject. Finally, in the last phase, we looked for ways to convert the newly acquired knowledge into something that is comprehensible in terms of both content and form. In the following, we examine in more detail the methods and steps taken in the course of the project together with the main results and findings ().

The Co-Design Best Practice Report

In surveying the current state of co-design with the aim of developing the user requirements overview and example scenarios (best practices), mixed qualitative methods were used. At the beginning of the project, five focus group sessions and workshops were organized in Austria, Denmark, Slovakia, Slovenia and Spain. These sessions brought together creative professionals with practical experience in the field of co-creation and co-design in industry, in non-governmental and public organizations and in academia. They shared their expertise, focusing on the benefits, challenges and difficulties of collaborative design in co-design projects. Part of the workshops were also in-depth interviews with the protagonists of the selected practices. Through a number of questions and lengthy group discussions, the participants were deliberately and exhaustively quizzed about their experiences, challenges, barriers and possible ways of overcoming them, as well as ways of ensuring successful and active co-creation with the aim of promoting knowledge sharing. The interviews indicated that despite all the benefits of co-creation and co-design processes, co-creation can be challenging for creative professionals to manage. The process typically involves a large number of stakeholders; during the co-creation process the facilitator or participant might face issues arising from the different personal characteristics of stakeholders, complex relationships and divergent expectations, as well as (not that rarely) be confronted with resistance to change or disbelief that users can bring value to the process. That is why specific skills for the management of collaborative development processes are usually necessary.

The participants also shared their know-how on overcoming these challenges; in combination, the above provided the foundation that enabled us to summarize the focus group findings in eight key guiding principles () required for successful co-creation (Sneeuw et al. Citation2018).

Table 1. 8 key principles for successful co-creation.

These eight key guiding principles proved crucial for the following steps, as they also served as the backbone of all subsequent documents. Like other findings and the final documents, they were repeatedly tested in practice during the research and supplemented or partially revised as needed (the steps involved in testing and evaluations are described in more detail below). The research eventually confirmed that when engaging in a co-creation process, these eight key principles form the basis for a successful co-creation process—of course with the proviso that the proposed guiding principles, while forming the framework for successful operation, must also be adapted each time according to the individual project and the context of the identified challenge.

The Co-Create Curriculum for Creative Professionals

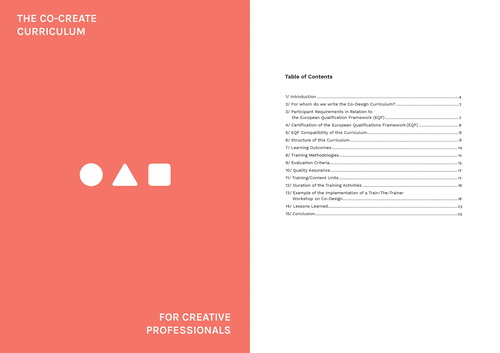

Prior to elaborating and producing a curriculum for developing training activities in co-design, four new focus group sessions were developed and conducted later on in Austria, Denmark, Slovakia and Spain. At this stage, the topics discussed with the participants of four new focus group sessions included ‘what a curriculum for co-design should comprise’ and ‘which training formats would be best suitable for their successful application in creative industries’. The resulting Focus Group Findings Report, together with the already produced The Co-Design Best Practice Report, instigated the production of the first version of the curriculum ().

Figure 2. The contents of the co-create curriculum (Retegi et al. Citation2019a).

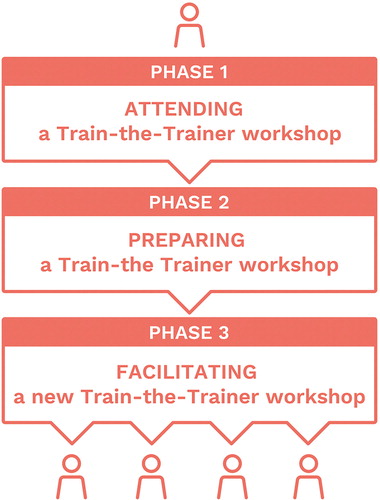

Much like the key guiding principles, the curriculum was also written in an open-ended fashion—given the nature of the co-creation process, flexibility of processes and methods is required from the outset. The document reflects the findings of the study, while the structure of the final version of the document is determined by learning outcomes defined by three descriptors: Knowledge, Skills and Competences. In practice, this entails a three-step process that the trainer needs to grasp in order to successfully complete the proposed vocational education programme:

PHASE I: Attending a ‘Train the Trainer’ workshop in order to learn and practice co-design both in theory and practice, using collaborative methods to develop co-design solutions to a challenge that the participants are briefed on. In this phase, theoretical and practical knowledge on collaborative design, as well as knowledge on how to train others in the same topic, is acquired. In this phase, a minimum of three days of intensive work is necessary to cover the first phase of the methodology. These three day-sessions can be extended or even organized into several shorter sessions. However, it is recommendable that the intervals between individual sessions are short.

PHASE II: Preparing a ‘Train the Trainer’ workshops on co-design for his or her own professional environment. In our methodology, this phase is the one in which the participants are meant to personally apply the knowledge and competences acquired during the previous phase. In our case, the latter lasted approximately three months. The duration can be shortened. However, if the participants work in dynamic professional sectors, regular educational activities become unfeasible. Moreover, developing the workshop requires ample time.

PHASE III: Facilitating a new ‘Train the Trainer’ workshop in the candidate’s specific professional scenario. This phase is meant for practicing the actual specifics of running a collaborative process in a real professional environment. It is also understood as a phase in which the candidate attempts to evaluate their own competences. During our Co-Create project, we conducted intensive three-day workshops (8 hours per session) with excellent results. The workshop can be extended throughout several months. Furthermore, its proposed simulations can be converted into actual implementations ().

These three phases may be seen as the basic methodological mechanism through which the curriculum is meant to facilitate the education. They form the ‘operating system’ which—as stated before—can and should be customized for specific professional applications. To provide additional encouragement for the latter, we have integrated dynamic and integrative forms of collaborative design training into the curriculum. The intent of this integration was to find a way to avoid proposing specific formulas or training methodologies which will soon end up outdated. Our aim was for this training methodology to be understood as a customizable system to be run at ‘Train the Trainer’ activities in co-design. Therefore, the ‘operating-system’ metaphor is a three-phase set of co-design and educational principles which enable creation of specific and successful educational experiences. On successful completion of the suggested training module, students will be able to:

Consider a collaborative and methodological design strategy for the issue in question.

Define key structural aspects to develop the collaborative process: funding, division of responsibilities, production of the events, etc.

Facilitate and develop a complete collaborative process.

Prepare specific co-design workshops for training others in collaborative design.

We supplemented the training methodologies and learning outcomes with two further elements that are mandatory for any educational programme: Evaluation Criteria and Educational Quality Assessment, as well as another key document with content useful for carrying out the curriculum: the handbook.

The Co-Create Handbook for Creative Professionals

Once the curriculum was at an advanced stage, the handbook for training trainers in co-design was elaborated as a document supporting both participants and organizers of co-design process. Building on all the previous deliverables and the know-how produced in the course of the project, the document underwent several subsequent revisions on the basis of validation tests, much like the curriculum. Crucial insights were gathered at the workshop ‘Train the Trainer’ (organized in 2018), the purpose of which was to test the adequacy of the suggested content of both main documents.

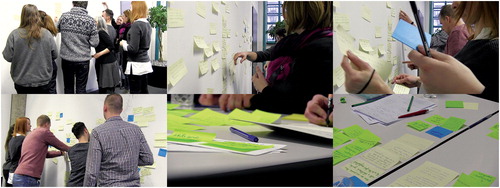

The ‘Train the Trainer’ workshop in Austria was developed with the intention of training ten co-design professionals; at the conclusion of the workshop, these would become co-design trainers themselves. Together with these newly trained trainers, we tested many aspects of the curriculum and the handbook, which resulted in important contributions to both documents. The ‘Train the Trainer’ workshop in Austria was later followed by five ‘Train the Trainer’ workshops in Austria, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Slovenia and Spain. These workshops were prepared and facilitated by the aforementioned co-design professionals who received their training at the workshops in Austria, and were attended by 99 participants. Workshops dealt with five different topics: co-design, social design, service design, urban design, and system design and had five different challenges for the workshop participants. Their task was to implement methodology from the curriculum and the handbook in their local professional environment and once more empirically evaluate both of them.

It needs to be emphasised that the process at the workshops was not evaluated by the trainers alone; members of the consortium actively participated in the evaluation through contextual observation. The workshops enabled us to build the foundation for the user evaluation methodology and therefore the basis for further iterations of the documents under development (the curriculum, the handbook and the training materials). In other words, the development of the workshops followed the double helix principle: the three-phase ‘operating system’ that represents the basic methodological mechanism through which the curriculum is meant to facilitate the education also served as the basis for the user evaluation methodology. In practice, this meant that at the ‘Train the Trainer’ and ‘Train the Professionals’ workshops in Austria, throughout the learning process and through various assignments, we constantly monitored the primary test users (our future trainers), recorded our observations and finally conducted interviews and compared the results thus obtained.

The evaluation did not end here, however; as mentioned, we envisioned from the outset a dual role for the primary test user. In the first phase, they acquired knowledge and tested in practice the steps and ways of adapting tools and methods, evaluating the education process received according to their experience. They were subsequently placed in the position of teaching, transmitting the acquired knowledge to the secondary test user. In this next step, the same participants could therefore evaluate the same material from an entirely different point of view.

The advantages of this approach (with the objective of validating and evaluating the methodology established in the curriculum, the handbook and the useful resources and supplementary materials provided) therefore lie in placing the newly trained trainers in the position of having to clarify and explain the steps from the curriculum using the tools and methods provided in the handbook, thus revealing the extent of the understanding they had achieved in the first phase. In the next phase, both us—the observers—and trainers once again evaluated the acquired knowledge, this time from the position of one who needs to have understood the knowledge before passing it on, as well as planning and conducting the co-design workshop. In simple terms, much like how we test children’s understanding of the meaning of a particular word by having them use the word in a sentence, the trainers, who were the primary test users, had to pass the knowledge newly obtained from the curriculum and handbook on to the professionals, the second test user.

Contextual observation has (among other things) shown that sometimes, certain groups of participants will need more support than others in order to let their imagination fly. It is therefore vital for trainers to observe their participants very closely and identify the difficulties they may find. It also turned out that another way that trainers can improve their ability to facilitate the process is by basing any of their additional explanations on examples from their own practice, and in other cases through active participation. Yet another finding from the observations was that trainers should also take into account that sometimes more than one facilitator would be needed. This requires additional thinking and planning at the time of preparing the workshop.

Throughout the period of observation, during the workshops, it was important to track the ways in which the objectives were being achieved. The success of the latter was evaluated on the basis of the mutual understanding of the co-design process. The results obtained weren't based solely on observation, however; we also sought feedback after the workshops concluded. We asked everyone—the trainers and the participants—to fill out a standardised questionnaire (featuring questions such as: ‘Is the structure of the document clear to you?’, ‘Is the redaction of the contents easily understandable?’, ‘Are the concepts well explained?’); we also let them independently express their opinions and provide suggestions for improvements. Indeed, it was these suggestions that eventually proved to be of vital importance for the last iteration of the curriculum and the manual. For instance, from a Trainer’s perspective it was important to:

Create groups of participants with a diversity of approaches and mindsets. Homogeneity led to predictable solutions while diversity produced creative outputs.

Work on real challenges with the participation of real people involved with the issue in question. Real, tangible challenges motivated participants much more than abstract ones.

Be prepared for some participants to show no interest in certain methods. Always have more methods ready and change along the way if necessary.

Be willing to share your methods and tricks with the participants. Participants will—if interested—also become trainers and they were usually curious about the methods of facilitation and the organization of group dynamics.

Combine working periods with discussion sessions. Trainers realized that participants were quite open to bringing in their expertise. Oftentimes, they had the need to share how certain processes worked in their organizations. Guiding these discussions and making them part of the workshop proved to be very valuable.

From a Participant’s perspective it was important to:

Have the possibility to flexibly manage his or her practice with workshop time.

Adjust the difficulty of the workshop to participants’ expertise. Even within the same workshop process, different groups can use more or less sophisticated methods and prototyping materials. This may help to reduce the number of participants who lose motivation during the workshop.

Prepare enough pedagogical material to expand the content of the workshop.

At the end of the workshop, revisit the methods and processes employed. A recap session was often suggested by the participants who felt unable to abstract the big steps given in the workshop.

Propose excursions and networking sessions to engage with others’ expertise and professional activity. An important aspect of these workshops are the new networks and relationships which will be created during real-life scenarios. Participants expect this.

Through the results obtained from these five ‘Train the Trainers’ workshops, the consortium used the logic of affinity diagram to organize the gathered insights and prioritized the findings. One of the key prioritisation criteria was, how to train professionals in the clearest and most understandable way and simultaneously impart to them the skills necessary for training others. Alongside the existing objective of continuously evaluating the adequacy of the curriculum and handbook in real professional scenarios that involved training non-experts in co-design ().

The new knowledge acquired and the lessons learned at these workshops were included in the latest versions of The Co-Create Curriculum for Creative Professionals and The Co-Create Handbook for Creative Professionals documents. The findings discussed in the documents include the four key steps in co-creation () that have been identified and defined.

Table 2. 4 key steps in co-creation.

The handbook therefore provides detailed explanations as to how to prepare a co-creation workshop: what to look out for, which methods and tools have been found—on the basis of numerous validations—to be potentially useful for various contexts and the various problems identified. In other words, the handbook serves as a guide for the elaboration of ‘Train the Trainer’ workshops in co-design and to specify the minimum content these workshops may cover. On the one hand, it assists organizations in designing successful workshops in co-design. On the other, it includes useful content for practising co-design, understanding its theory and gaining training skills. It also presents case studies and real application scenarios. The handbook should, therefore, be seen as a resource showing ways to implement the curriculum. While the curriculum presents a methodology for disseminating co-design in professional environments, the handbook introduces newcomers to co-design theory, as well as to the practical issues of co-creation in the context of creative industries ().

Figure 5. The contents of the co-create handbook (Retegi et al. Citation2019b).

The Co-Design Essentials – Collective Creativity: How to Learn Co-Creation

The last phase of the project was devoted to the elaboration of training materials which can be easily distributed and managed. The implementation steps in the form of The Co-Design Essentials (video tutorials and hands-on guide) derived from the findings obtained at the capacity-building workshop on implementing teaching and learning open educational resources (Draganovská et al. Citation2019). The Co-Design Essentials are conceived as useful resources and supplementary materials meant to improve success in preparing and conducting the co-design workshops. They also serve as graphic resources for professionals interested in the field of co-design. During the ‘Train the Trainers’ workshops, the working versions of the materials were (in the same way—described above—as the curriculum and the handbook previously) evaluated and revised based on users’ responses.

Conclusion

Active introduction of co-design into design practice and into the broader context of co-creation has brought with it the anticipated changes—both in the way we operate and in the understanding of who designs, as well as what we design (Sanders and Stappers Citation2008). These shifts have spurred the development of new tools and methods and introduced considerable changes in the very nature of design: from designing for people to designing with and by people (Sanders and Stappers Citation2014, 25). It is this change of approach that creates the foundation for building on trust (Clarke et al. Citation2019) and consequently shared understanding (Kleinsman and Valkenburg Citation2008). Both co-design factors are increasingly being pushed to the forefront of design, as prerequisites for achieving results that are high quality, tangible and well-received by end-users (Jansen and Pieters Citation2017), as well as for ‘demonstrating new approaches, insights and validation using material resources toward enabling action’ (Clarke et al. Citation2019, 14).

Despite the tangible benefits of incorporating active co-design into design processes, there are still noticeable gaps and deficiencies in the knowledge of how to implement the co-creation process—both on the part of the many professional design teams and in the area of non-formal learning: an area that could enable many professional designers, as well as the interested public in the general sense, to acquire the knowledge necessary to actively introduce co-creation and co-design into their work. The research demonstrated that many design professionals first and foremost lack the skills for facilitating the process with the aim of stimulating the collective creativity of the participants, as well as encouraging the sharing and generation of new knowledge and the establishment of new understanding (the backbone of which are the eight key principles for successful co-creation).

Accordingly, the proposed curriculum and handbook attempt to reduce this gap by making co-design training more accessible among educational organizations and creative professionals. The value of the results is in that it builds the foundation for actively fostering the processes of integrating co-design into the field of professional design. Through the creation of alternative learning experiences and the curriculum, we have simultaneously expanded and strengthened the possibilities for including the general public into the processes of co-creation with the aim of stimulating collective creativity. The two documents are not only valuable in the sense that they enable the interested public to acquire the knowledge necessary for the preparation and facilitation of co-design workshops; they also present methods for training others in collaborative design in the course of the workshop (4 key steps in co-creation).

The significance of this work goes beyond the research results; its merit is also in its in-depth illustration of the development process of the new curriculum and manual in the field of co-creation. The detailed explanation of the processes involved in the co-creation of the present documents and their continuous evaluation (all of the steps in the creation of the documents were based on the methodologies of co-creation) gives design professionals (as well as the broader public) a unique perspective on the possibility of a different approach to the creation of educational materials. New knowledge has been established for all those (pedagogical) communities that will, in the future, be facing the task of preparing a new curriculum, manual or any other document meant to facilitate the inclusion of numerous stakeholders with the intent to educate and integrate new knowledge, competences and skills (regardless of whether the topic is closely associated with co-creation). The described approach highlights the power of establishing and integrating a plurality of voices from both practical and theoretical backgrounds, and of the capability of actively developing competences and skills that build on both practice and theory; at the same time, the established carefully considered steps, along with continuous evaluation, help create a system of knowledge that is exceptionally open and adaptable on the one hand, and quantifiable in a concrete way on the other.

The Curriculum also provides an evaluated format and methodology of disseminating co-design in professional environments, especially in the context of creative industries. In addition, the fact that the proposed curriculum is EQF-compatibleFootnote2 enables national certification agencies to certify the particular implementations. It is important to mention here that the consortium partners are well aware of the limitations of the study, since with the given project funding, the last step (the certification) was not realized; accordingly, we welcome any responses from the interested public with regards to our implementation attempt. Any responses from users of the materials provided will likewise be welcomed, as this would serve as a confirmation of the aim of the research: to boost the creation of co-design training communities and the active implementation of co-creation processes in order to promote collective creativity.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank all the co-creators and co-authors of the Co-Create project, Denisa Draganovská, Martin Kaltenbrunner, Aiur Retegi, Brigitte Sauvage, Gisa Schosswohl, and Enrique Tomás. I also thank the members of focus groups and the participants of the co-creation workshops. Special thanks go to Tjaša Bavcon, Dominika Belanská, Domen Benčič, Juraj Blaško, Petra Černe Oven, Mojca Fajdiga, Andreas Hentner, Ján Hološ, Marián Hudák, Joan Knudsen, Gaja Mežnarič Osole, Klemen Ploštajner, Lidija Pritržnik, Patricia Stark, Maja Vardjan, Zuzana Tabačková, Gerin Trautenberger, and Peter Zehetbauer for their collaboration.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Barbara Predan

Barbara Predan is an Associate Professor, theoretician, designer, and author. She is also the co-founder and leader of the Department of Design Theory at the Pekinpah Association and, since 2014, the Director of the Institute of Design, an academic research organization. She has published professional and scholarly articles in Design Issues, Design Principles and Practices, Filozofski vestnik, and Dialogi, among others. She is also the author or co-author of six books, has edited ten books and curated twenty exhibitions. With Dr. Petra Černe Oven, she established the book series Zbirka 42. Since 2009, she has been teaching at the University of Ljubljana, Academy of Fine Arts and Design, and regularly lectures at international academic and professional conferences.

Notes

1. Since the project included six partners from five European countries, it was unanimously agreed our working language would be English. In order to avoid language barriers, all the interviews, workshops, testing and evaluations that took place in the individual countries were conducted in their national languages. Materials were likewise translated. The results obtained were translated into English by professional translators and handed out to partners at periodic partner meetings. All the meetings, conferences and workshops (such as the ‘Train the Trainer’ workshops) with an international audience were conducted in English, as had been announced in advance.

2. To make the multiple European education and training systems more transparent and comparable, the EU Commission suggested changing the way professional curricula have traditionally been set up. The EQF is an instrument for mapping qualifications from the national education system to other educational systems in Europe. The EQF can be seen as a translation tool which is necessary to reference all national qualifications and to make them comparable. Each EU Member State is able to implement its own qualification framework but it must allocate specific national qualifications to a European reference level system.

References

- Arnstein, Sherry R. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Planning Association 35 (4): 216–224. doi:10.1080/01944366908977225.

- Černe Oven, Petra, and Barbara Predan. 2013. Designing an Agenda, or, How to Avoid Solving Problems That Aren't: Focus: Service and Information Design. Ljubljana: Pekinpah Association and Regional Development Agency of the Ljubljana Urban Region.

- Černe Oven, Petra, and Barbara Predan. 2016. V Kakšnem Svetu Hočemo Živeti? Zdravstvo: življenjska Premica [What World Do We Want to Live In? Healthcare: The Life Line]. Ljubljana: Društvo Pekinpah and Inštitut za oblikovanje.

- Clarke, Rachel Elizabeth, Jo Briggs, Andrea Armstrong, Alistair MacDonald, John Vines, Emma Flynn, and Karen Salt. 2019. “Socio-Materiality of Trust: Co-Design with a Resource Limited Community Organisation.” CoDesign: 1–20. doi:10.1080/15710882.2019.1631349.

- Clarkson, P. John, and Roger Coleman. 2015. “History of Inclusive Design in the UK.” Applied Ergonomics 46 (B): 235–247. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2013.03.002.

- Coleman, Roger. 1994. “The Case for Inclusive Design—An Overview.” Proceedings of the 12th Triennial Congress. Toronto: International Ergonomics Association and the Human Factors Association.

- Cross, Nigel. 1971. “Here Comes Everyman.” In The Design Research Society Conference, edited by Nigel Cross, 11–14. Manchester: Academy Editions.

- Draganovská, Denisa, Martin Kaltenbrunner, Barbara Predan, Aiur Retegi, Brigitte Sauvage, Gisa Schosswohl, and Enrique Tomás, eds. 2019. The Co-Design Essentials – Collective Creativity: How to Learn Co-Creation. Linz: Creative Region.

- Jansen, Stefanie, and Maarten Pieters. 2017. The 7 Principles of Complete Co-Creation. Amsterdam: BIS Publishers.

- Jones, John Chris. 1972. “Closing Comments.” In Design Participation: Proceedings of the Design Research Society's Conference, Manchester, edited by Nigel Cross. London: Academy Editions, September 1971.

- Kleinsman, Maaike, and Rianne Valkenburg. 2008. “Barriers and Enablers for Creating Shared Understanding in Co-Design Projects.” Design Studies 29 (4): 369–386. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2008.03.003.

- Luck, Rachel. 2018. “Editorial: What is It That Makes Participation in Design Participatory Design?” Design Studies 59 (C): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2018.10.002.

- Mächtig, Saša J. 1976. Minutes of the IXth General Assembly (ICSID), Typescript, Brussels. The Minutes Are Preserved as a Typescript in MAO’s Archive, Ljubljana.

- Manzini, Ezio. 2015. Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Manzini, Ezio, and François Jegou. 2003. Sustainable Everyday: Scenarios of Urban Life. Milan: Edizioni Ambiente.

- Nielsen, Jørgen Lerche, and Lars Birch Andreasen. 2015. “Higher Education in Scandinavia: A Case Study.” In Democratizing Higher Education: International Comparative Perspectives, edited by Patrick Blessinger and John Anchan, 92–110. New York: Routledge. Chapter 7.

- Nova, Nicolas, ed. 2014. Beyond Design Ethnography: How Designers Practice Ethnographic Research. Genève: HEAD – Genève.

- Peterlin, Marko, Tadej ŽAucer, Alenka Korenjak, and Zala Velkavrh. 2015. Celovita Urbana Prenova [Integrated Urban Renewal]. Ljubljana: Institute for Spatial Policies.

- Retegi, Aiur, Brigitte Sauvage, Barbara Predan, Enrique Tomás, Gisa Schosswohl, Martin Kaltenbrunner, and Denisa Draganovská, eds. 2019a. The Co-Create Curriculum for Creative Professionals. Linz: Creative Region.

- Retegi, Aiur, Brigitte Sauvage, Barbara Predan, Enrique Tomás, Gisa Schosswohl, Martin Kaltenbrunner, and Denisa Draganovská, eds. 2019b. The Co-Create Handbook for Creative Professionals. Linz: Creative Region.

- Sanders, Elizabeth B.-N., and Pieter Jan Stappers. 2008. “Co-Creation and the New Landscape of Design.” CoDesign 4 (1): 5–18. doi:10.1080/15710880701875068.

- Sanders, Liz, and Pieter Jan Stappers. 2014. “From Designing to Co-Designing to Collective Dreaming: Three Slices in Time.” Interactions 21 (6): 24–33. doi:10.1145/2670616.

- Schön, Donald. 1983. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York: Basic Books.

- Simonsen, Jesper, and Toni Robertson. 2013. “Participatory Design.” In Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design, edited by Jesper Simonsen and Toni Robertson, 1–17. New York: Routledge.

- Smith, Rachel Charlotte, and Ole Sejer Iversen. 2018. “Participatory Design for Sustainable Social Change.” Design Studies 59 (C): 9–36. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2018.05.005.

- Sneeuw, Adrian, Aiur Retegi, Barbara Predan, Barbora Spisakova, Enrique Tomas, Georg Tremetzberger, Gisa Schosswohl, Joan Knudsen, Martin Kaltenbrunner, and Nora Busturia, eds. 2018. Co-Design: Best Practice Report. Linz: Creative Region.