Overview

While dementia may affect the way our minds work, we will always know what we like. Where biographical identity diminishes, but experiential identity and emotional memory is retained, experiencing pleasure from personal preferences in everyday surroundings has significance. If verbal communication becomes arduous, assumptions can be made about inability, leading to everyday decisions being made on our behalf. The resultant negative impact on sense of identity and agency in the context of intrapersonal and interpersonal relationships is recognized in dementia care. Consequently a strengths-based approach is advocated, where a focus on abilities can challenge negative assumptions. This study explores the role of research through design, using visual stimuli as probes, to support non-verbal expression of personal aesthetic preferences in the curation of personal space. This paper describes the development of methods using remote sensory ethnography to share personal preferences for everyday objects and colour in the context of home.

Introduction

Dementia describes a group of diseases that result in a progressive and permanent decline in cognitive function. It is estimated that 700,000 informal caregivers support 850,000 people living with dementia (Alzheimer’s Research UK Citation2018). In a society that places value on intellect, assumptions can be made about capability. Where dementia is characterized by trauma, deterioration, and shame, loss of self is situated in intrapersonal and interpersonal relationships. Kitwood and Brooker (Citation2019) cite negative and overprotective physical and social environments as contributory factors to the acceleration of the disease. They advocate preservation of personhood, through an empathic approach that confers mutuality and respect, that can be intuited on an emotional level. Choice is central to dementia advocacy articulated by people with lived experience of dementia (NDAA (National Dementia Action Alliance) Citation2021) who are asking for research that challenges assumptions about capability (Mitchell Citation2019).

In dementia, Halpern et al. (Citation2008) found that, even in the absence of executive function, aesthetic preferences might be retained. Byers (Citation2011, 1) observed a preoccupation with arranging colours and materials, suggesting a search: ‘for something aesthetically satisfying’. The value of arts viewing to improve mood, attention, communication, and dyadic care relationships (Windle et al. Citation2018) is being promoted (SCIE (Social Care Institute of Excellence) Citation2021). Ability to learn new skills in dementia is being demonstrated (Clare et al. Citation2019). Sanders and Stappers (Citation2012) suggest that co-design methods that invert the hierarchy of needs to prioritize self-actualization have relevance to challenging assumptions about ability. Winton and Rodgers’ (Citation2019) observations of participants’ ability to recognize their own designs suggests this is the case.

Aim

To use research through design to develop tools to enable visual expression of aesthetic preferences to support agency in the curation of personal space.

Objectives

Review research and practice on use of visual stimuli to motivate and support people living with dementia.

Articulate the relevance of personal aesthetics preferences to support identity and agency in dementia.

Develop collaborative design methods to explore preferences for everyday objects, colour, materiality, and personal space to reinforce conscious awareness of aesthetic preferences.

Test the efficacy of interactive tools to support expression of everyday aesthetic preferences in curation of personal space.

Approach

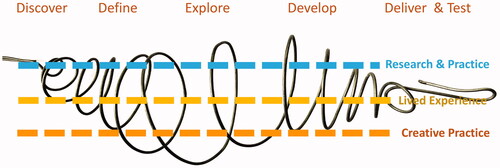

Situated in practice-based research through design, I adopted a reflexive approach to define and explore the issues, and develop, deliver, test, and evaluate design tools to support non-verbal expression of preferences. It is a revolving process: review of research; conversations with specialist practitioners and participants; and design practice to reflect, interpret, and create tangible responses and interventions (). Within COVID-19 restrictions contact has been via remote video conferencing.

Positionality

As an occupational therapist specializing in accessible housing design to support independence for disabled and older people at home, my approach is informed by the ‘person–environment–occupation’ model of practice (Law et al. Citation1996) and the impact that these factors have on ability and agency. In healthcare, a predominant medical model defines people by their diagnosis (Pollard and Block Citation2017), resulting in home environments that become clinical or institutional in appearance. The negative and stigmatizing impact of these environments on wellbeing can be significant. A cultural model of disability and ageing that seeks to learn from strategies individuals adopt through lived experience (Lee Citation2020) informs my methodology. My research aims to inform design briefs for environments that people want to live in, rather than must live in, due to complex cognitive impairments such as dementia (Walker Citation2017).

Background

Aesthetics and identity

The complexity of aestheticsFootnote1 from perspectives in philosophy, arts, science, and psychology continues to be contested (Townsend Citation2010). The relevance of ‘everyday aesthetics’ to the experiential self in dementia is considered here.

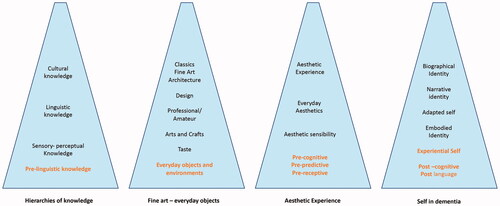

If design is reliant on sensory-perceptual knowledge rather than solely an intellectual process where aesthetics involves ‘acquiring and creating knowledge – prelinguistic knowledge’ (Whitfield Citation2005, 16) it is located within a hierarchy () where an aesthetic sensibility experienced in everyday life can be overlooked. Exponents of ‘everyday aesthetics’ see its value in enhancing quality of life (Saito Citation2007).

As cognition becomes impaired our response to the environment is increasingly on a sensory level (van Hoof et al. Citation2010). Brown observes progression towards an experiential self where ‘the evolution of self is clearly toward a post language/post cognitive self’ (Brown Citation2017, 1011). Visuo-sensory experience becomes significant. If aesthetic experience is a pre-cognitive and pre-reflective understanding of the perceived without need for higher mental capacities (Carman Citation2008), it is accessible at a prelinguistic level. Neuroaesthetics situates aesthetics in a framework of sense, meaning, and emotion (Chatterjee Citation2014). If personal preferences reflect a sense of identity, then pleasure derived from perceived beauty resonates with the assertion that an emotional rather than factual memory is retained (Alzheimer’s Society Citation2022), then this immediate and visceral experience has relevance in dementia.

Environmental design for dementia

Improved visual access (attention to lighting, tonal contrast, coherence, legibility, and sightlines) can support function and orientation (Marquardt, Bueter, and Motzek Citation2014). In the field of neuroarchitecture, Feddersen and Lüdtke (Citation2014) propose multi-sensory design approaches to support a more intuitive engagement with the environment. A salutogenic approach to design centred on promoting wellbeing in dementia is advocated (Fleming, Zeisel, and Bennett Citation2020), challenging designers to incorporate a sense of ‘meaningfulness’.

Life stories

In dementia where a narrative sense of self is lost, life story work provides insights into factors that influence behaviours enabling more personalized care (Kaiser and Eley Citation2017). Life story practitioners have acknowledged that although photographs of family and friends are often used, images of home environments are rare. In everyday aesthetics the interrelationship between utility and appearance presents opportunities to explore the meaningfulness of visual and haptic responses.

Personal space and the meaning of home

Our control over personal space expands and contracts throughout life. In dementia an increasing reliance on others who are making decisions on our behalf reduces choice and control over curation of personal space. Lee’s notion of ‘material citizenship’ advocates the routine use of utilitarian objects in care settings to provide familiarity and sense of competence (Lee Citation2019). Relevance and specificity of environmental stimulation have been found to affect motivation, and personalization in care environments is recommended (Bowes and Dawson Citation2019, 92). Pertinent to supporting agency is the notion of curation to create a collection of familiar objects that could provide visual clues to identity ().

Research through design applied to exploring lived experience

In design-led enquiry both artefacts and methods can emerge from an inductive approach and embody ideas that inform new theories (Knutz and Markussen Citation2019). The potential for ‘producing knowledge that is relevant to that very complexity intrinsic to all situated conditions’ (Ednie Brown Citation2017, 134) has relevance to understanding lived experience in dementia. Creative methods of enquiry to explore expression of preferences might reveal previously unimagined alternatives.

This study uses everyday objects and environments as a lens through which to explore expression of personal identity, where critical artefact methodologies such as those used to convey experience with difficulties in dressing (Lee Citation2018) have relevance to supporting personhood and sensory awareness retained in dementia. At a visuo-sensory perceptual level, exploring subjective experience using visual cues could inform design briefs for accessible interactive tools for visual expression in dementia.

Developing a methodology

Lovely mug ugly mug

To provoke reflections on everyday aesthetic preferences a surveyFootnote2 asked participants (nine males, 14 females aged 26–95 recruited through personal and professional networks) to share images of their favourite and least favourite mugs and the reasons for their choices.

Unsurprisingly, what is deemed lovely or ugly is interchangeable and individual, and preferences change. Remarks about dislikes were often more vociferous (). Participants remarked that this experience enhanced their awareness of personal preferences.

Colour choices

Initial tests with 100 Pantone colour cards (one male, five female, age range 24–87) provoked more immediate and decisive responses. Reflections on everyday aesthetic preferences in homes, clothing, and sentimental attachments emerged, and suggested that colour triggers a visual biography of preferences related to how control over personal space expands and contracts throughout life.

Testing feasibility and relevance to dementia

An advisor living with dementia has advised on how to make videoconferencing as accessible as possible. User-led guidance has informed the ethics application DEEP (Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project, Citation2013). The value and relevance of this enquiry to potential beneficiaries was explored in a Zoom meeting with members of Sheffield Dementia Involvement Group (SHINDIG) using favourite mugs to provoke discussion. Responses included: ‘That it should never be assumed that people with dementia are not capable of making choices’; that objects ‘provoke positive memories’; and ‘Colour is a huge part in our choice of clothes and interiors and should always be considered’. The value of videoconferencing was noted: ‘Can virtual access to our homes/possessions via Zoom help us get to know each other better?’ (SHINDIG Citation2020, 28–29). Facilitators remarked on benefits for participants, emphasizing the need to challenge the assumed power of institutions of care on how personal space could be curated.

Shared looking

An iterative practice of exchange using visual stimuli and response to map and articulate expression of aesthetic preferences has been developed. This collaborative approach to making everyday aesthetic preferences explicit uses one-to-one online meetings to learn from situated experience in the home. The rationale for this methodology is drawn from frameworks that support everyday creative thinking (Sanders and Stappers Citation2012) by exploring present experience to provoke reflections that can inform future preferences.

The facilitation methods are adapted from visual thinking strategies, a non-judgemental approach that provokes personal reflection found to be effective in arts viewing for people living with dementia (Camic et al. Citation2018, 8). The use of objects, colour, and personal space as probes to provoke and support non-verbal expression through gesture and facial expression is intended to support capabilities retained in dementia where communication can become challenging.

Videoconferencing first adopted due to COVID-19 restrictions has benefits for remote sensory ethnographic methods that interrogate the complexity of situated experience (Pink Citation2012). While digital exclusion is acknowledged, more active engagement by some online than in person has been observed by SHINDIG facilitators. Remote participation is potentially less intrusive, more immediate, and accessible and relevant to exploring curation of personal space.

Phase 1

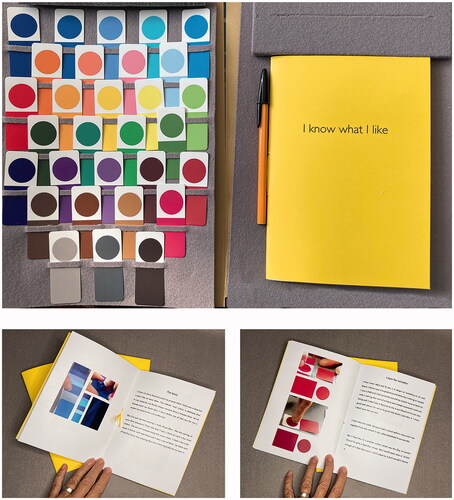

Participants without a diagnosis of dementia (five male, nine female, age 24–96) shared reflections on their preferences for mugs, colour choices, and favourite spaces in the home. Three semi-structured, 45 min ‘show and tell’, one-to-one meetings test the efficacy of these probes to elicit expression of choice. Colour cards were designed with an intentionally approximate spectrum, range in hue, and saturation to account for visual deficit ().

The process enables an iterative and responsive dialogue. Booklets of images and quotes are provided after meetings to sense-check whether this represents participants’ choices (). Participants have remarked that making choices more explicit, and the feeling of pleasure it evokes, reinforces a sense of identity. Participants have noticed becoming more conscious of habitual routines and private internal narratives.

Preferences for personal space, and how this supports or hinders activity and engagement, privacy, or social exchange, have also been discussed. The extent to which emerging themes resonate with spaces that support creativity is of interest. User groups (Dementia Pioneers Citation2022) and specialist practitioners have advised on tailoring methods to suit individual capabilities.

Phase 2

Evaluation of findings in Phase 1 is informing methods in Phase 2. Recruitment criteria are drawn from those used in cognitive rehabilitation (GREAT (Goal Oriented Cognitive Rehabilitation in Early Alzheimer’s and Related Dementias) Citation2022): people with a diagnosis of dementia, and capacity to consent, who can engage in everyday activities, and are interested in exploring personal preferences. Ability to use, or be supported to use, videoconferencing is also required. Design of recruitment materials has been informed by user guidance DEEP (Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project, Citation2020). Ethics was approved in February 2022Footnote3

Phase 3: Design response and evaluation

Findings will inform criteria for a design brief for accessible tools to support expression of choice in the curation of everyday personal space. Experiments in materializing visuospatial experience of personal space using three-dimensional models are emerging. The design brief and initial prototypes will be shared for the purposes of evaluation and efficacy with participants and the specialist practitioners who were interviewed at the outset.

Analysis

Grounded Theory as an iterative process of analysis and reflection is being used to support a generative design research approach that can reveal observable and tacit knowledge through inductive reasoning (Sanders and Stappers Citation2012). Continuous immersion and close analysis of qualitative data are documented in reflective journals. A framework of emerging convergent and divergent themes identified from exchange with participants is being coded into a framework to track design decisions, documented in an annotated portfolio.

Conclusion

A review of existing research and current practice in dementia has highlighted the significance of personalization to support identity and agency. This study has explored the value of research through design to develop interactive methods and tools to support expression of personal everyday aesthetic preferences. A shared looking methodology using visual probes to provoke engagement is emerging. Visualization of findings to make choices more explicit indicates potential to enhance awareness and personal aesthetic sensibility. In the context of progressive cognitive impairment this strengths-based approach utilizes sensory abilities retained, offering potential to challenge assumptions about capability in intrapersonal and interpersonal relationships.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marney Walker

Marney Walker is a research degree candidate at Lab4Living, Sheffield Hallam University.

Notes

1 Aesthetics: ‘A branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of beauty and taste, as well as the philosophy of art (its own area of philosophy that comes from aesthetics). It examines subjective and sensori-emotional values, or sometimes called judgments of sentiment and taste’. Stanford Dictionary of Philosophy.

2 Converis Ethics Review ID ER22515755 23.04.20.

3 Converis Ethic Review ID: ER34886059.

References

- Alzheimer’s Research UK: Dementia Statistics Hub. 2018. Accessed 1 June 2022. https://www.dementiastatistics.org/statistics/impact-on-carers/

- Alzheimer’s Society. 2022. How Do People Experience Memory Loss? Accessed 1 June 2022. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia/symptoms-and-diagnosis/symptoms/memory-loss-in-dementia

- Bowes, Alison, and Alison Dawson. 2019. Designing Environments for People with Dementia: A Systematic Literature Review. Emerald Publishing. doi:10.1108/978-1-78769-971-720191004.

- Brown, Juliette 2017. “Self and Identity Over Time: Dementia.” Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 23 (5): 1006–1012. doi:10.1111/jep.12643.

- Byers, Angela 2011. “Visual Aesthetics in Dementia.” International Journal of Art Therapy 16 (2): 81–89. doi:10.1080/17454832.2011.602980.

- Camic, Paul M., Sebastian J. Crutch, Charlie Murphy, Nicholas C. Firth, Emma Harding, Charles R. Harrison, Susannah Howard, Sarah Strohmaier, Janneke van Leewen, et al. 2018. “Conceptualising and Understanding Artistic Creativity in the Dementias: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Research and Practise.” Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1842. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01842.

- Carman, Taylor. 2008. Merleau-Ponty. London: Routledge.

- Chatterjee, Anjan. 2014. The Aesthetic Brain: How We Evolved to Desire Beauty and Enjoy Art. Oxford University Press.

- Clare, L., Kudlicka, A., Oyebode, J. R., Jones, R. W., Bayer, A., Leroi, I., Kopelman, M., et al. 2019. “Goal-Oriented Cognitive Rehabilitation for Early-Stage Alzheimer's and Related Dementias. The GREAT RCT.” Health Technology Assessment 23 (10): 1–242. doi:10.3310/hta23100.

- DEEP (Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project). 2013. DEEP Guide: Writing Dementia Friendly Information. Accessed 23 March 2022. https://www.dementiavoices.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/DEEP-Guide-Writing-dementia-friendly-information.pdf

- DEEP (Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project). 2020. The DEEP Ethics Gold Standards for Dementia Research. Accessed 23 March 2022. https://www.dementiavoices.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/The-DEEP-Ethics-Gold-Standards-for-Dementia-Research.pdf

- Dementia Pioneers. 2022. Mini Internship Session 26-05-2022. Accessed 1 June 2022. https://dementiaenquirers.org.uk/news/

- Ednie-Brown 2017. “When Words Won’t Do: Resisting Impoverishment of Knowledge.” In Practice-Based Design Research, edited by Laurene Vaughan, 131–140. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Feddersen, Eckhard, and Insa Lüdtke, eds. 2014. Lost in Space: Architecture and Dementia. Basel: Birkhäuser.

- Fleming, Richard, John Zeisel, and Kirsty Bennett. 2020. World Alzheimer Report 2020: Design, Dignity, Dementia: Dementia-Related Design and the Built Environment. London, England: Alzheimer’s Disease International. Accessed 23 March 2020. https://www.alzint.org/resource/world-alzheimer-report-2020/

- GREAT (Goal Oriented Cognitive Rehabilitation in Early Alzheimer’s and Related Dementias). 2022. “Cognitive Rehabilitation: Who Is It For?” Accessed 1 June 2022. https://sites.google.com/exeter.ac.uk/great-cr/cognitive-rehabilitation/who-is-it-for?authuser=0

- Halpern, Andrea R., Jenny Ly, Seth Elkin-Frankston, and Margaret G. O’Connor. 2008. “I Know What I like”: Stability of Aesthetic Preference in Alzheimer’s Patients.” Brain and Cognition 66 (1): 65–72. doi:10.1016/j.bandc.2007.05.008.

- Kaiser, Polly and Ruth Eley, eds. 2017. Life Story Work With People With Dementia: Ordinary Lives, Extraordinary People. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Kitwood, Tom, and Dawn Brooker. 2019. Dementia Reconsidered Revisited: The Person Still Comes First. London: Open University Press.

- Knutz, Eva, and Thomas Markussen. 2019. “The Ripple Effects of Social Design: A Model to Support New Cultures of Evaluation in Design Research.” In Design Research for Change Symposium, 223–240. Lancaster University.

- Law, Mary, Barbara Cooper, Susan Strong, Debra Stewart, Patricia Rigby, and Lori Letts. 1996. “The Person-Environment-Occupation Model: A Transactive Approach to Occupational Performance.” Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 63 (1): 9–23. doi:10.1177/000841749606300103.

- Lee, Kellyn 2019. “‘Could Be a Risk Couldn’t It’: Decision-Making, Access to, and the Use of Functional Objects for People with a Dementia lIving in a Care Home.” PhD diss., University of Southampton.

- Lee, Yanki 2018. “Dementia Going Social Innovation Design Lab.” Accessed 23 March 2022. https://www.enable.org.hk/en

- Lee, Yanki 2020. “Co-Design the Ingenuity of Ageing: A Cultural Model of Ageing Through Design Thinking.” In Researching Ageing: Methodological Challenges and Their Empirical Background, edited by Maria Luszcynska, 99–107. London: Routledge.

- Marquardt, Gesine, Kathrin Bueter, and Tom Motzek. 2014. “Impact of the Design of the Built Environment on People with Dementia: An Evidence-Based Review.” HERD 8 (1): 127–157. doi:10.1177/193758671400800111.

- Mitchell, Wendy. 2019. Speaking at UK Dementia Congress Session: Dementia Enquirers – People with Dementia in the Driving seat of Research. UK Dementia Congress, December 2019.

- NDAA (National Dementia Action Alliance). 2021. “The Dementia Statements: Through a Legal Lens.” Accessed 23 March 2022. https://dementia-united.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2021/05/National-Dementia-Action-Alliance-Dementia-Statements.pdf

- Pink, Sarah 2012. Situating Everyday Life: Practices and Places. London: Sage Publications.

- Pollard, Nicholas, and Pam Block. 2017. “Who Occupies Disability?” Cadernos Brasileiros de Terapia Ocupacional 25 (2): 417–426. doi:10.4322/0104-4931.ctoEN18252.

- Saito, Yuriko 2007. Everyday Aesthetics. Oxford: Oxford University Press on Demand.

- Sanders, Elizabeth B. -N, and Pieter Jan Stappers. 2012. Convivial Toolbox: Generative Research for the Front End of Design. Amsterdam: BIS.

- SCIE (Social Care Institute of Excellence). 2021. “Creative Arts for People With Dementia.” Accessed 23 March 2022. https://www.scie.org.uk/dementia/living-with-dementia/keeping-active/creative-arts.asp

- SHINDIG (Sheffield Dementia Involvement Group). 2020. “I Know What I Like – Looking At Our Tastes and Preferences in Everyday Life.” Accessed 22 March 2022. https://www.shsc.nhs.uk/get-involved/service-user-groups/sheffield-dementia-involvement-group-shindig

- Townsend, D. 2010. The A to Z of Aesthetics. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

- van Hoof, J., H. S. M. Kort, M. S. H. Duijnstee, P. G. S. Rutten, and J. L. M. Hensen. 2010. “The Indoor Environment and the Integrated Design of Homes for Older People with Dementia.” Building and Environment 45 (5): 1244–1261. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2009.11.008.

- Walker, Marney 2017. Housing LIN Viewpoint 85: Creating Homes That People Would Like to Live in Rather Than Have to Live In. Accessed 22 March 2022. https://goo.gl/0U4AjH

- Whitfield, T. W. Allan 2005. “Aesthetics as Pre-linguistic Knowledge: A Psychological Perspective.” Design Issues 21 (1): 3–17. doi:10.1162/0747936053103002.

- Windle, Gill, Samantha Gregory, Teri Howson-Griffiths, Andrew Newman, Dave O'Brien, and Anna Goulding. 2018. “Exploring the Theoretical Foundations of Visual Art Programmes for People Living with Dementia.” Dementia (London, England) 17 (6): 702–727. doi:10.1177/1471301217726613.

- Winton, Euan, and Paul A. Rodgers. 2019. “Designed with Me: Empowering People Living With Dementia.” The Design Journal 22 (sup1): 359–369. doi:10.1080/14606925.2019.1595425.