OVERVIEW

The mass digital adoption and rapid industry transformation have increased the number of things that need to be designed. In addition, Lean and Agile development demands faster ways to reflect and foresee impact. Designers are tackling more complex challenges, contexts, and systems. To assess these design challenges and decentralize the creative contribution, designers seek distributed knowledge, diverse and systemic thinking, adopting various collaborative practices, and more inclusive and holistic approaches to perform their work. The following sub-study supports the assessment of collaboration in Design in the broader term, contributing to the overall PhD study that aims to develop a collaborative and systemic method and toolkit to design technological and responsible service solutions. It shows a thematic analysis of a virtual focus group discussion where four designers discuss the past, present, and future collaboration in and through Design.

Introduction

Before this sub-study, I participated in several collaborative projects where designers played an essential role in orchestrating and integrating knowledge and making subjective topics more concrete for discussion.

I argue that co-creation and multidisciplinary sense-making offers advantages for the innovation process, and designers, beyond bringing their unique perspective, can work as facilitators, using participatory methods and tools that support reflection and consideration of sensitive topics. People can provide different perspectives on their job responsibilities, past experiences, and intrinsic cultural and social values (Luff Citation1999). Furthermore, diverse thoughts boost change in mindset and support organizations to remain competitive in the market (Prahalad and Ramaswamy Citation2004), engage in shared ownership of decision and responsibility of impact, care about successful customer engagement and the value creation across the business ecosystem (Institute of Noetic Sciences Citation2007).

This sub-study presents a thematic analysis of a virtual focus group discussion where a panel of experts, four experienced designers, discussed the past, present, and future collaboration in and through Design. The themes resulting from the analysis will support the overall PhD study to understand the challenges, advantages, and expectations of the multidisciplinary innovation and future collaboration in Design practice. The topics that emerged from this sub-study will be the starting point for further assessment and to develop a collaborative framework to approach innovation and a systemic method and toolkit to design technological and responsible service solutions.

The panel of experts discussed answers to the following questions:

How does collaboration play over time in their career as a designer?

How familiar were they with Co-design, Co-creation, Participatory Design? What are the main differences, if any?

What are the biggest challenges in collaboration?

What is the desired way of collaboration in the Design Future?

Materials and methods

I performed a virtual focus group and used a thematic analysis approach (Terry et al. Citation2017) to analyze the content generated by the participants. The intention is to understand how collaboration in Design practice evolves and what methods and tools designers will need to facilitate and tackle more complex and systemic challenges.

Focus group

The focus group methodology enables the research to expose a topic to people collectively construct meanings around it (Bryan-Kinns, Wang, and Wu Citation2018). A convenient sampling of six experts was invited to the panel, but only four attended. Like me, the participants are experienced Brazilian designers living in different parts of the globe and engaged in co-creation, co-design, and participatory design practices. And to anonymize their profiles, I will refer to them as FG 01—Experienced design practitioner and streamer working in a global remote company that provides a freelancing platform, FG 02—Senior UX Designer at a European fintech start-up, FG 03—Senior Service Designer working with CDE classes in a Brazilian bank and FG 04—a professor and researcher with PhD in Participatory Design, currently studying oppression in Design ().

The session was held online, using MS Teams, and was 80 min long. Participants engaged in the discussion from the beginning to the end. They knew each other as they are all involved with Design communities of practice. They were comfortable and felt secure about the setup. A Miro board was presented for taking notes, but they preferred a casual conversation.

Thematic analysis

A thematic analysis was used to identify patterns in challenges, diverging points of view, and trend opportunities in the discussion generated in the focus group.

The data extracted from the virtual focus group interview recording was analyzed using Thematic Analysis within the critical realist framework and following the interpretative paradigm (Ceschin and Gaziulusoy Citation2020). This contextualist method supports the understanding of topics that could arise from the participant’s reflection on past and current experiences, and when collectively discussing the desirable future of collaboration in Design—the coding of the data considered meaning and experience at both semantic and latent levels ( and ).

Results

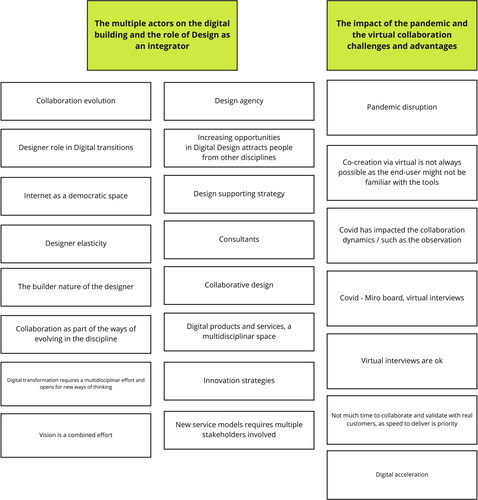

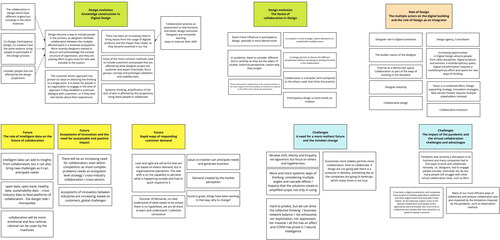

The initial coding links to the questions subjects. Using thematic analysis, the study revealed four main themes and categories related to the research questions. The themes branched into eight sub-themes, all originating from my interpretation of the data (). The themes and sub-themes align with or complement my current thoughts on the subjects being studied.

Next, I analyzed quotes from the focus group session and interpretation of themes and sub-themes:

The collaboration in the design evolution

The increasing work complexity in the Design field has led designers to continuously assess the knowledge that support them to perform their work better.

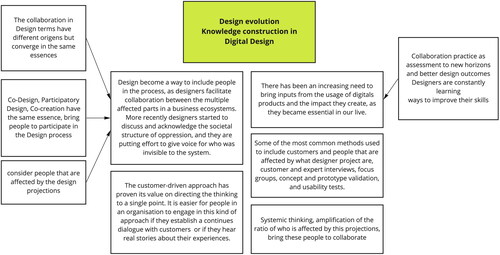

Knowledge construction in digital design

Collaboration practices support designers’ knowledge growth by adding diverse perspectives and steering the process to better digital design outcomes. Although, there have been different approaches during the last 50 years. For instance, in Design Thinking (Kimbell Citation2011), Design is a reflexive act that helps collaborators understand wicked problems in an ambiguous space. It assumes that the design outcomes have multiple meanings to multiple individuals. Service Design extends the thinking to support collaborators to reach a bird’s eye view of the service experience life cycle, considering value network and organizational operations to bridge the company’s silos and achieve customer-centric excellence (Stickdorn et al. Citation2018) ().

Figure 5. Desing evolution (theme) and knowledge construction in digital design (sub-theme), data summary example.

FG 04—“Collaboration was presented first in the 60 s, with the shift in the industry, the Toyotism, also known as Toyota Production System, where people needed to start working more closely. In the 70 s surges the Collaborative Design, Designers began to work more collaborative with other disciplines, influenced by the Toyotism in the automotive industry. Later in the 90 s, the term Co-design started being used for Collaboration with users, not only in multidisciplinary setups. Nowadays, the term Co-Design evolved to encompass a variety of collaborations in Design … Participatory Design was presented as a more democratic process, surging syndicates and academies in Europe, between the 60 s-70s, grounded in Constructivism theories presented by Paulo Freire in participative communities. Participatory Design aims to give the participants the power to decide what to Design and how, and if given tools Design by themselves.”

There are several approaches to collaboration in Design, e.g. Co-creation, Co-design, and Participatory Design. These approaches may have different origins, e.g. Marketing, Business, and Design. Still, it converges in the same principles of considering people affected by the design process or outcomes. As these systems we are facing are recognizably more complex, design becomes a way to assess and map the impacted parts of an ecosystem. Including people in the process helps build a shared vision and shared responsibility. Designers facilitate conversations by making the intangible subjects tangible. Recently, designers started to discuss and acknowledge the societal structure of oppression. They are putting effort to give a voice to those invisible to the system.

FG 03—“The customer-driven approach has proven value in directing the thinking to a single point. It is easier for people in an organization to engage in this kind of approach if they establish a continued dialogue with customers or hear real stories about their experiences.”

Some of the most used methods and tools in Digital Design focus on users and their interactions with the brand, products, and services, e.g. customer and expert interviews, focus groups, concept and prototype validation, and usability tests. There has been an increasing demand for methods and tools that support designers to foresee the impact of the design process and outcomes, to be more inclusive, fair, just, and responsible.

The facets of collaboration in design

Scholars need to carefully consider different terms in academia as they are the object of studies. They look at historical perspectives and reasons why they are increasingly used.

FG 04—“Co-creation is more strategic, where demand is co-created with multiple actors. Co-design permits the discussion of the different perspectives without narrowing or putting limits in the collaboration. Collaboration is a broader term than the others used, limiting the practice. Participatory design is more hands-on creation.”

As mentioned previously, academics and practitioners refer to collaboration in Design in many ways. Terms, such as Co-creation, Co-design, and Participatory Design are used in many studies and even in academia; these approaches seem to have multiple definitions. An example: Prahalad and Ramaswamy (Citation2004) define Co-creation, in the context of the future of the business competition, as the process of continuously generating product or service demand by involving potential and existing consumers in the design process, creating a dialogue between the organization and their customers. Sanders and Stappers (Citation2008) differ between Co-design and Co-creation, as Co-design takes place across the lifespan of the design process, and Co-creation takes place within a single design session. Here you see an utterly opposed definition of Co-creation. I have used the Prahalad and Ramaswamy definition of Co-creation since my MBA in Service in Design and Innovation, where I first encountered the term.

There is an increased demand for real-world collaboration in the market to support more sustainable and responsible processes and outcomes, and academia has not been able to keep up with the fast digital transformation speed, as academics tend to respond to the shifts in the industry by observation. On the other hand, industry practitioners find internal ways to organize themselves with agile and lean approaches. Practitioners are increasingly investing in continuous collaboration with customers. From these dialogues, they try to quickly respond to demand from the business network and customers (users of their products and services). These fast responses and tunnel vision work may lead to unexpected and unwanted consequences.

However, considering participants as ‘partners’ rather than ‘subjects’ is at the roots of participatory Design (Sanders and Stappers Citation2008), and configuring participation in innovation and design process became essential to achieve more sustainable and responsible outcomes in the real world.

The integrator role of designers in multidisciplinary collaboration work

Designers have been a crucial part of the digital transitions. The rapid changes in technology and the increasing number of things that need to be designed have required flexibility and adaptability from the practice. Designers need to gain access and learn to use resources that support diverse perspective integration. The outcomes of an innovation process are the work of many, and a successful approach would consider a shared vision from the start.

FG 03—“When working in agencies, we had a great number of projects from different industries. And as a consultant, you must be able to collaborate to attend to the expectations and assess the knowledge you need for the work. There is an elasticity that is required from designers.”

FG 04—“Vision is a combined effort. The design supports innovation strategies, with it, new service models, which requires multiple stakeholders involved.”

Challenges in collaboration

There have been challenges in finding value in collaboration from stakeholders, as coming to workshops, attending interviews, and sometimes even doodling ideas feels demanding in the first place.

A need for a more resilient future and the mindset change

Academics and practitioners must develop empathy to understand and accept differences and focus on otherness and togetherness. In addition, establish practices to encompass systems thinking, considering multiple angles and ways of knowing, taking responsibility, and looking into the cascade effects of their decisions towards the society and the planet.

FG 01—“Hard to predict, but we can drive the collective thinking, bring to the business network a balance, not exhaust nor exploit, nor oppress, nor invasive. All this has an effect, and COVID has proven it. There is natural intelligence, and it looks for balance.”

The impact of the pandemic and the virtual collaboration challenges and advantages

The pandemic was undoubtedly a disruption in all businesses, and many companies had to find ways to work and collaborate remotely. Designers and other practitioners had to engage with people virtually, and many of the design research methods were made difficult.

FG 03—“Many of our more efficient ways of collaborating and analyzing collaboration was also impacted by the limitations imposed by the pandemic, such as observation method.”

Collaboration in the design future

The new directions in collaboration will bridge the communication between industry, academia, and society to respond quickly to the market demand for sustainable and resilient products and services that can respond to situations, such as the pandemic.

The collaboration will continuously expand, involving communities of practice and nurturing local community capabilities as part of the business ecosystem.

Rapid ways of responding to customer demand

Lean and agile are becoming old terms as they are organizational operations based on the need to react to customer demands. The shift is towards a more proactive approach, generating demand by sensing what is happening outside, continuously dialoguing with customers, and capturing demand before needing to react.

FG 04—“The demand discovery should be created by the market perception. The fundamental approaches have no clear understanding of what needs to be solved, there is no clear hypothesis that predicts long-term impact, but we are all there to learn and understand.”

Ecosystems of innovation and the need for sustainable and positive impact

There will be an increasing need for collaboration, even within competitors, as more complex problems need an ecosystem level strategy.

FG 04—“Cross-sector collaboration has increased due to the challenges faced by the ecosystem networks. The innovation between industries has increased. There is also a constant demand coming from customers experiences with digital services and the global challenges, which requires a systemic and more holistic approach.”

The role of intelligent data in the future of collaboration

With the accuracy and reliability of predictive models, data intelligence can predict behaviour and measure the impact on supporting organizations to make wiser decisions. Intelligent data will become easy to access, and collaboration will have a moral purpose, e.g. the trolley problem (Bonnefon, Shariff, and Rahwan Citation2016). Access to Intelligent data can also become a privilege for big companies.

FG 03—“Intelligent data can add to insights from collaboration. Still, it can also bring new challenges as it can anticipate needs from open data analysis, healthy data, sustainability data. We could cross-industry data to feed platforms of collaboration. The dangerous side of it are the monopolies, and small companies might not benefit from it.”

Conclusion

All the themes and sub-themes presented in this study contribute to the overall PhD study. A general reflection on the subjects shows that the value of collaboration through Design is growing exponentially. Designers are constantly introducing new collaborative and systemic methods and tools that give people space to debate, express what they know, and learn from others, increasing trust and teamwork along the service and product lifecycle.

This sub-study confirms that sharing knowledge to solve design challenges relies on ‘partners’ (Sanders and Stappers Citation2008), even if they are ‘intelligent machines’, and their capabilities to make shared and responsible decisions based on transdisciplinary collaboration and real-world insights.

There is still a need to further investigate how designers and non-designers are configuring the collaboration process and review some current methods and tools they have been using. The objective is to find challenges and opportunities to promote others’ worldviews, which are essential for generative knowledge and expansive learning, and support larger ecosystems to connect and meet the demand for a healthier planet and society.

Acknowledgements

This work builds on the knowledge for a PhD dissertation. No grant or funding was used.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available on request from the corresponding author, JV. The data is not publicly available as it compromises the privacy of research participants.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jane Vita

Jane Vita is the design lead at the Technological Research Center of Finland, VTT. Her daily work is about creating bridges between innovative technologies and sustainable, human, and ethical futures, supporting the research impact’s maximization. She is a PhD candidate in New Media at Aalto University and owns Masters in Web Design and Service Innovation and Design from Laurea University. With over 20 years of career, Jane has experienced various design fields, such as Visual, Interaction, Service Innovation, and Digital Strategy Design, within multiple projects in different industries and countries. She taught courses on Service Design in the Digital Context at Laurea University and teaches the course Designing Services with New Technologies at Aalto University and Design Thinking in the Gamification Applied to Digital Platforms program at Post-PUC Digital. She regularly shares her work in magazine papers, workshops, and conferences. Jane believes that design challenges must be tackled holistically and systemically. And that designers can facilitate collaboration and communication between experts to reflect and build solutions for a better world.

References

- Bonnefon, J. F., A. Shariff, and I. Rahwan. 2016. “The Social Dilemma of Autonomous Vehicles.” Science 352 (6293): 1573–1576.

- Bryan-Kinns, Nick, Wei Wang, and Yongmeng Wu. 2018. “Thematic Analysis for Sonic Interaction Design.” doi:10.14236/ewic/HCI2018.214.

- Ceschin, F., and I. Gaziulusoy. 2020. “Design for Sustainability: A Multi-Level Framework from Products to Socio-Technical Systems.” In Routledge Focus on Environment and Sustainability. 1st ed. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429456510

- Institute of Noetic Sciences. 2007. “The 2007 Shift Report: Evidence of a World Transforming.” In Proceedings of the Design Research Society’s Conference 1971, edited by N. Cross. London: Academy Editions.

- Kimbell, Lucy. 2011. “Rethinking Design Thinking: Part I.” Design and Culture 3 (3): 285–306. doi:10.2752/175470811X13071166525216

- Luff, D. 1999. “Dialogue across the Divides: “Moments of Rapport” and the Power in Feminist Research with anti-Feminist Women.” Sociology 33 (4): 687–703. doi:10.1017/S0038038599000437

- Prahalad, C. K., and V. Ramaswamy. 2004. “Co-Creation Experiences: The Next Practice in Value Creation.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 18 (3): 5–14. doi:10.1002/dir.20015

- Sanders, Elizabeth B.-N., and Pieter Jan Stappers. 2008. “Co-Creation and the New Landscapes of Design.” CoDesign 4 (1): 5–18. doi:10.1080/15710880701875068

- Stickdorn, M., M. E. Hormess, A. Lawrence, and J. Schneider. 2018. This is Service Design Doing: Applying Service Design Thinking in the Real World. O'Reilly Media, Inc.

- Terry, G., N. Hayfield, V. Clarke, and V. Braun. 2017. “Thematic Analysis.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, 17–36. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526405555