Abstract

Universal design aims to maximise usability for all, and to achieve this participation of people with disabilities in design processes is essential. However, it is unknown how universal design and co-design, as a means of participatory design, can be applied to the architectural design of public buildings. This study aimed to explore stakeholder perceptions and experiences on this topic. As a qualitative study, three workshops were held with 26 people with disabilities, advocates, and design professionals. A phenomenological approach to data analysis was employed. Four major themes emerged: there are challenges to practicing co-design; co-design is inclusive, accessible, and genuine; co-design is planned and embedded in all design stages; and co-design delivers positive outcomes. Findings strongly support participation of people with disabilities in architectural design, highlight challenges and limitations to current practice, and provide insight into factors that optimise outcomes and the experiences of those involved.

Introduction

Universal design encourages designers to design environments that are usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without need for adaptation or specialised design (Mace Citation1985). Other terms, such as ‘inclusive design’ and ‘design for all’, are used synonymously but definitions, historical origins, and geopolitical contexts of use vary (Persson et al. Citation2015). In Australia, universal design is called for by several local, state, and federal political frameworks (Larkin et al. Citation2015) and internationally is enshrined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations Citation2007).

There is advocacy for users to participate in design and a range of methods identified by which this can be achieved (Day and Parnell Citation2003; Sánchez De La Guía, Puyuelo Cazorla, and De-Miguel-Molina Citation2017). Co-design describes participatory design where end users are actively involved in the whole design process (Sanders and Stappers Citation2008). The user is given a role of expert in their experience and invited to contribute toward knowledge development, idea generation, and decision-making (Sanders and Stappers Citation2008). Co-design in architecture is a recognised method of participatory design with several descriptions and practice case studies available (See for example: Combrinck and Porter Citation2021; Cruickshank, Coupe, and Hennessy Citation2013; Gaete et al. Citation2022; Shouman, Othman, and Marzouk Citation2022). However, there is limited empirical evidence on how people with disabilities participate in the co-design of public buildings where universal design is applied and how these experiences are perceived by those involved.

Background

Proponents of universal design and inclusive design have long advocated for people with disabilities to participate in design as ‘user-experts’ (Coleman Citation1994; Ostroff Citation1997; Ringaert Citation2001) – a term coined by Ostroff (Citation1997) to identify people who have ‘developed natural experience in dealing with the challenges of our built environment’ (33). This is based on the understanding that designers commonly do not have lived experience of disability, may not appreciate how environmental barriers influence activity and social participation, and may be unable to effectively predict experiences of people who do (Barnes Citation2016; Bickenbach et al. Citation1999; Oliver Citation1990). Inadvertently, designers may create barriers or overlook design solutions that maximise environmental accessibility and usability (Heylighen, Van der Linden, and Van Steenwinkel Citation2017; Heylighen et al. Citation2016; Pritchard Citation2014; Sarmiento-Pelayo Citation2015). A premise of universal design and inclusive design is that by considering the needs of people with disability, environmental barriers are reduced for all people, e.g. designing a step-free entrance not only benefits people who use wheelchairs but also people with temporary impairments, parents with prams, older people, and delivery personnel (Bianchin and Heylighen Citation2017; Fleck Citation2019; Hamraie Citation2017). However, an individual’s experience and perceptions of environmental barriers is unique and the concept of ability/disability is not binary (Campbell Citation2019). Rather as a social construct, disability is an umbrella term that describes an outcome of the interaction between a person and their environment (World Health Organization (WHO) Citation2002). People who identify as living with disability experience health conditions that impact physical, cognitive, and/or sensory abilities (WHO Citation2002), but concepts like intersectionality remind us that there is no single story of exclusion. Rather, people’s interactions with environments are affected by multiple intersecting personal and cultural concepts of gender, race, and ability (Crenshaw Citation1991). Application of universal design offers a broader way of meeting user needs than accessibility standards which address only a singular aspect of identity or need, e.g. wheelchair use (Hamraie Citation2013).

Human diversity and intersectionality can also be seen to influence designers and design processes. Design is a value-laden process whereby actions, priorities, and decisions cannot be separated from the sociological, personal, and emotional contexts of those involved. Decisions to embed methodologies, such as accessibility, universal design, and co-design, are value-driven (Hamraie Citation2013) and can be seen, not only as ways to challenge designers’ views of a ‘normative’ user group, but also to address value-driven barriers that have excluded and disadvantaged people with disabilities over time. Social inequality, power, and privilege cannot be separated from design methodologies but rather should be considered and acknowledged as factors underpinning people’s motivations, decisions, and emotional responses to design and the processes involved (Clement et al. Citation2019; González-Hidalgo and Zografos Citation2020).

Co-design is a way of explicating the knowledge of non-designers and potentially influencing values underpinning design (Hamraie Citation2016). However, little is known about whose perspectives are and should be included in co-design, how people with disabilities perceive co-design processes, facilitators and barriers to meaningful participation, and what outcomes are achievable. Additionally, in the Australian context, there is a gap in empirical knowledge about which stages of the design process people with disabilities participate in and how timing of participation influences experiences and outcomes. This research aims to explore stakeholder perceptions and experiences of co-design as applied to the universal design of public buildings in Australia.

Method

Study context

This study was an extension of a larger 2019 project ‘Accessible and Inclusive Geelong (AIG)’ in which researchers worked with a community Taskforce to determine actions required to overcome obstacles to city-scale accessibility and inclusivity in Geelong; an Australian regional city (Tucker et al. Citation2022). AIG participants recommended that an Inclusive Visitor Centre, run and managed by people with disabilities, should be built in Geelong. At project conclusion, this was posited as a priority action to be underpinned by co-design and universal design (Tucker et al. Citation2022).

This paper presents a study that aimed to explore stakeholder perceptions and experiences of engaging people with disabilities in the co-design and universal design of a proposed public building, i.e. the Geelong Inclusive Visitor Centre.

The Empirical Phenomenological Framework (Todres and Holloway Citation2004) informed a qualitative study design and a participatory approach was taken to maximise input of people with disabilities. Generating new knowledge collaboratively serves to strengthen credibility of findings and provide opportunity for a greater range of outcomes to be achieved (Bigby and Frawley Citation2015). A person with a disability who was a member of the Taskforce and experienced in advocacy and policy was employed as a Participant Researcher during development and delivery of data collection methodology. Participants, many of whom lived with disability, were invited to contribute to data analysis by reviewing and commenting on study findings as they were generated. These forms of member checking enabled the researchers to compare their account of workshop discussions with participants and seek verification and clarification on their interpretation of findings (Higginbottom Citation2015). Thematic analysis was employed using an Interpretative Phenomenological Approach (IPA) (Smith and Eatough Citation2007). The Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee approved this project (Project ID: 2019-023).

Data collection

Data were collected via three online workshops (WS) where the researchers were able to facilitate in-depth conversations and rich group interaction (Liamputtong Citation2020). Four researchers facilitated the workshops: three academics and a Participant Researcher.

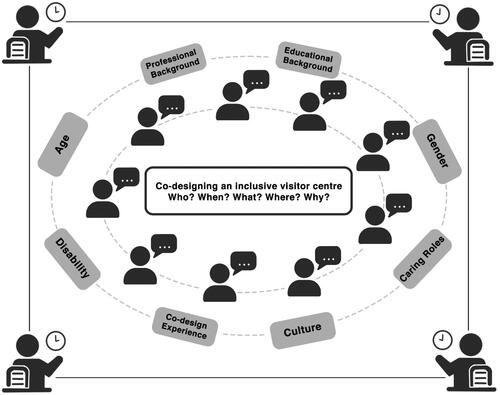

During each 1.5-hour workshop, participants introduced themselves describing relevant professional/volunteer roles, and experiences relating to disability, building design, and co-design. Participants were then asked to discuss what the terms co-design and universal design meant to them and to reflect on past experiences where people with disability participated in co-design of public buildings. Participants were not asked to identify past projects or present details on project scale or type, but rather to describe experiences and roles broadly. Participants were prompted to outline who was involved, what stages of design people with disabilities participated in, and what could have been improved. To simulate application of theory, participants were prompted to complete the sentence ‘If we were going to co-design the Geelong Inclusive Visitor Centre, we would need to ….?’, giving consideration to: who should be involved; when people with disability should participate; what should happen; where co-design should occur; and why co-design should be employed. Participants interactively discussed questions posed and shared perspectives and experiences. graphically depicts the workshop process and key personal attributes and experiences noted to influence discussion.

People were invited to identify support needs before each workshop and live-transcription services were included in Workshops One and Two. Visual prompts, and a video summarising AIG project findings, were presented. Demographic data were collected via questionnaire. All workshop discussions were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Sampling

Phenomenology calls for participation of people with lived experience of a phenomenon of interest (Patton Citation2015). In this study, that cohort was people who have experience of co-design and universal design. Additionally, this study sought to gain perspectives of people with disabilities, some of whom may hold professional roles relating to design, advocacy, and/or access consultancy. The study was promoted via the Taskforce with ongoing commitment to the AIG project and to the broader community as part of a public event, Geelong Design Week 2020. Due to Covid-19 restrictions, all workshops were held online. Two workshops were held in November 2020. Responding to low recruitment of design professionals, an invitation to participate in a third workshop in July 2021 was purposively disseminated to professional peak bodies and at a professional conference. All interested parties were provided with a plain language statement and consent form via email and returned this prior to workshop participation. To be eligible to participate, people needed to have experience in co-design and/or universal design, be over 18 years of age and have capacity for informed consent. Malterud, Siersma, and Guassora (Citation2016) Model of Information Power was used throughout this study to inform decisions about sample size, membership, and number of workshops.

Participants

Over three events, 26 people took part (Workshop One: n = 9; Workshop Two: n = 8; Workshop Three: n = 9). All participants in Workshops One and Two were in Geelong (n = 17). Participants in Workshop Three were located across Australia: Queensland (n = 2); New South Wales (n = 2); Victoria (n = 3); and Western Australia (n = 2). The majority were aged over 45 years (n = 21) and female (n = 23). Thirteen identified as disability advocates, six as access consultants, and five as architects. Access consultants commonly identified multiple roles including occupational therapist, architect, and/or disability advocate. Representation of occupational groups varied across workshops. Participants most commonly identified as a disability advocate in Workshops One (n = 4) and Two (n = 6) and as access consultants in Workshop Three (n = 9). All participants reported experience of disability, with 13 stating that they had personal experience of disability. See for demographic details.

Table 1. Participant demographics.

Data analysis

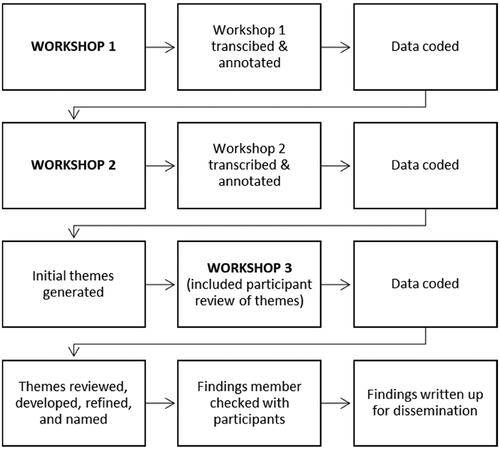

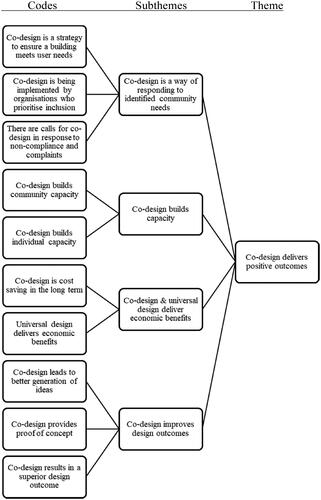

An Interpretative Phenomenological Approach (IPA) was employed during data analysis. This enabled the researchers to analyse data for meaning about co-design and universal design and how participants’ lives had been impacted by related experiences (Alase Citation2017; Creswell Citation2013). Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2013) reflexive thematic analysis was used to work through six steps of analysis: (1) become familiar with the dataset; (2) code the data; (3) generate initial themes; (4) develop and review themes; (5) refine, define, and name themes; and (6) write up findings (Braun and Clarke Citation2013). Researcher One reviewed each transcript several times to become familiar with the data and the individual and collective perspectives within (Alase Citation2017; Braun and Clarke Citation2013). To strengthen interpretation of meaning, comments and observations relating to the data, participants, and workshop dynamics were noted in each transcript (Creswell Citation2013). Significant statements and portions of text were ascribed meaningful codes that were then grouped according to similarity of meaning (Braun and Clarke Citation2013). These groupings were generated by Researcher One and reviewed by the broader research team to ensure that themes meaningfully represented embedded codes. Discrepancies were collaboratively reconciled through discussion. The researchers then worked through a process of ongoing refinement whereby themes were named and defined and meaningful data extracts selected for reporting (Braun and Clarke Citation2013). A graphical representation of the data analysis process is presented in and an example of theme development is presented in .

Strategies to strengthen the rigour of the study

Several strategies were implemented to enhance the rigour of this research. Firstly, multiple data forms and a multi-disciplinary research team served to triangulate data and perspectives (Liamputtong Citation2020). Secondly, an audit trail of codes, subthemes, and themes was maintained throughout analysis. Thirdly, a detailed description of methodology allows readers to consider transferability of findings to alternative contexts and settings (Liamputtong Citation2020). Finally, two forms of member checking were employed: (1) participants in Workshop 3 were invited to comment on a summary of findings gained from earlier workshops and responses indicated that emerging themes reflected participant perceptions and experiences of co-design; (2) after data collection, all participants were invited to review draft findings presented as a short video. Three participants responded with statements and practice examples supporting proposed findings. Data collected via member checking were interpreted during analysis and write-up of findings.

Results

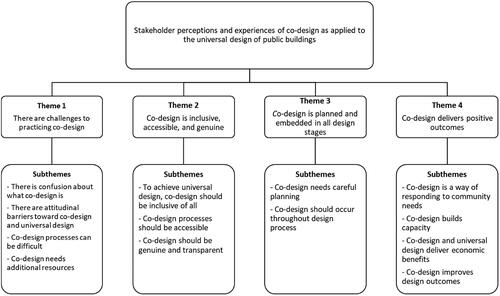

Findings are presented here as they respond to the research question: ‘what are stakeholder perceptions and experiences of co-design as applied to the universal design of public buildings?’.

Data were grouped under four overarching themes: there are challenges to practicing co-design; co-design is inclusive, accessible, and genuine; co-design is planned and embedded in all design stages; and co-design delivers positive outcomes. All themes and related subthemes are presented in .

There are challenges to practicing co-design

Findings highlighted challenges associated with co-design, which were grouped into four sub-themes: (1) confusion about what co-design is; (2) attitudinal barriers toward co-design and universal design; (3) co-design processes can be difficult; and (4) co-design needs additional resources.

Participants noted that the term co-design is inconsistently understood and can be challenging to differentiate from consultation and consumer engagement. Experience suggests that co-design, particularly of larger scale public buildings, is, at times, run as public-relations or marketing exercises that serve to ‘tick boxes’ rather than address ‘the nitty-gritty of actual access details’ (Participant 8; WS 3) or create inclusive environments. Attitudes such as designers thinking that they know all that is needed about access, being apathetic toward the needs of people with disabilities, and believing that meeting minimum code requirements was sufficient, were identified as barriers to universal design and co-design and discussed with expressions of frustration during workshops. Similarly, project managers’ and designers’ perceptions of co-design as being too complex, time-consuming, or costly were noted to limit application. This was supported by participants describing co-design processes as challenging, particularly without additional time and economic resources. Recruitment of people that experience diversity in disability and ensuring that all participants are genuinely heard during co-design, were noted as common practice difficulties. As stated by Participant 1 (WS 1): ‘It takes more time. It is important to be thorough. I recognise that fully, and co-design can take a lot longer to be all-inclusive.’ To address these challenges, participants called for greater advocacy and education on co-design, universal design, and disability.

Co-design is inclusive, accessible, and genuine

This theme included three subthemes: (1) to achieve universal design, co-design should be inclusive of all; (2) co-design processes should be accessible; and (3) co-design should be genuine and transparent.

Participants explained that buildings should meet the needs of all end-users by ensuring that people with a diverse range of abilities and health conditions are included in co-design. Participants disappointedly observed that, in their experience, often only a small number of people with disabilities are included and, as observed by Participant 3 (WS 1), there is a ‘need to broaden who is involved because I sometimes think the same people are involved in a lot of projects’. Participants called for co-design ‘to be inclusive of other people with different voices or different needs’ (Participant 7; WS 1) and that people with less visible conditions, like mental illness, cognitive impairment, neurodiversity, and complex communication needs, are commonly excluded. The use of advisory committees within local councils or transport departments, was seen by one participant with extensive access consultancy experience as a strategy to aid recruitment.

Participants acknowledged the complexities of making co-design accessible for all and proposed that multiple ways of communicating and participating should be offered. Scheduling multiple sessions, offering online and in-person communication, inviting people to indicate support needs, and implementing appropriate supports, were noted as ways that co-design could be tailored. Reflecting on their experience in professional roles supporting people with disability, Participant 8 (WS 1) noted that the best way to make co-design inclusive and accessible is to ‘ask people with disabilities how they would like to be engaged and what that would look like if we achieved it’. This was seen as an important first step to authentic co-design.

Participants emphasised that transparency was key to genuine co-design and expressed frustration that current practice often felt tokenistic. Participation in design commonly occurred via one-off consultations where information was collected from people with disabilities who were not included beyond that point. Participants emphasised that co-design should ensure that all voices are genuinely heard, that decision-making is collaborative, and that feedback is received on decisions made after providing input. In the words of Participant 2 (WS 3), a long-time disability advocate and person with disability:

…it is important to have a discussion about ‘Yes, we can do that’, ‘No, we can’t’, ‘Why can’t we do that? ‘Can we do it a different way?’, and that people are heard and encouraged to come to consultation. [People] will therefore feel that they are part of the process, because their feedback has been taken on board and responded to.

Co-design is planned and embedded in all design stages

Co-design requires careful planning and integration into all design stages. Participants emphasised that there is a complex process involved in effective co-design and that good planning and management was essential. As stated by Participant 2 (WS 2): ‘Having a clear plan … right at the very beginning, like a plan of how you are going to do it, so it does not start fading away or getting lost, like every single element needs to be considered.’

The timing of when people with disabilities should be involved in co-design was discussed and experiences varied. Sometimes people with disabilities were invited into the design process too late as decisions had already been made. Contrastingly, participants also expressed frustration at instances where they were involved in early design stages but not beyond that. Participants noted the importance of people with disabilities being involved in decision-making that occurs in later design stages so that accessibility and universal design were not value-managed out. As stated by Participant 3 (WS 2):

That is absolutely my experience – If the voices are not at the table through the project management and the design stages. If people are not there at the table, often it does get project managed out or budget managed out.

Co-design delivers positive outcomes

The final theme arose from four subthemes: (1) co-design is a way of responding to community needs; (2) co-design builds capacity; (3) co-design and universal design deliver economic benefits; and (4) co-design improves design outcomes.

Co-design was seen as a way to respond to accessibility issues in existing buildings and to determine if a new or modified building will meet user needs post-occupancy. Co-design also provided opportunities for building skills, knowledge, and positively changing attitudes of individuals involved. As noted by Participant 8 (WS 1), ‘If people don’t have skills - it is great to have a capacity approach to support growth of skills to enable participation’ and Participant 2 (WS 3), ‘The engineers and people like that who are involved really get to understand how people in mobility devices struggle to get in and out of spaces ….’. More broadly co-design offers opportunity to learn more about the needs of others:

…it is a sense of education across all spheres, across everything, I mean, if you know, sometimes you wouldn’t think about putting this in, but a blind person said to do it, or you wouldn’t think to put that in but a person in a wheelchair said to do it. Sometimes you might think about lighting because of Deaf people or people with epilepsy. There are many things that we can learn from others. (Participant 9; WS 1)

In this study, co-design and universal design were both perceived to deliver economic benefits and negate costly retrofitting. Finally, participants indicated that co-design leads to better idea generation, provides opportunity to test ideas, and results in superior design outcomes. As stated by Participant 3 (WS 1), when discussing their experiences as architect and access consultant, ‘The generation of ideas and practical application is so much better when you include everybody and their diverse ideas.’

Discussion

A key finding from this study is that stakeholder expectations of co-design as applied to public buildings differ from their experiences. Jenkins (Citation2009) proposed that, despite vast diversity in terminology and processes, participatory design is experienced in three ways: providing information; consultation; and negotiated/shared decision-making. Co-design sits within the third category as it requires a significant shift in power and process as the roles of professionals and users change to share decision-making (Jenkins Citation2009). Findings from this study suggest that collaborative decision-making is a highly valued expectation of stakeholders but that this was not commonly reflected in experiences shared. Rather these align with provision of information and consultation, suggesting a dissonance between the theory of co-design and reality in practice. Supporting these findings, Steen (Citation2013) highlighted that the term co-design is increasingly used to describe projects that incorporate participatory design but that overuse and misuse of the term has created confusion and dilution of its theoretical constructs. In this study, a dissonance between theoretical expectations and practical application was noted to create frustration in participants who intimately understood the impact of inaccessible environments and held strong emotional investment in design methodologies that value and promote inclusion. Such emotional investment may have influenced expectations of best practice and critique of current practice. Findings from this study support Sørensen and Ryhl’s (Citation2018) call for greater clarity on roles and expectations of people with disabilities in co-design.

Aligning with Sanders and Stappers’ (Citation2008) definition of co-design, building users should be involved across all design stages, especially where decisions are made about design outcomes. Although participants in this study emphatically supported this contention, it was again not reflected in their experiences. The timing of when people with disabilities participate in co-design was noted to not only impact perceptions of their experience but also outcomes gained from participation. In the co-design of services, user participation has been considered particularly important during the early ideation stages of design (Patrício and Fisk Citation2013; Trischler, Dietrich, and Rundle-Thiele Citation2019). However, findings from this study suggest that if people with disabilities are only involved in early stages of architectural design, participants may feel like they have not been genuinely heard and their participation not valued. These responses were expressed strongly when it was perceived that economic rationalism was prioritised over user needs and social inclusion. Conversely, study findings highlight risks associated with user-experts being involved too late where their role is limited to consultation and their impact on design outcomes is minimised. A challenge inherent in co-design is that by bringing together stakeholders with diverse backgrounds and perspectives, those involved may have conflicting values (Molnar and Palmås Citation2022). It is essential that consideration is given to potential power imbalances and the emotional investment that people with disability make to effect social change through value-driven methodologies such as co-design (González-Hidalgo and Zografos Citation2020). Developing and implementing ways for user-experts to effectively negotiate design outcomes throughout the design process is called for.

A key finding from this study is that, to apply universal design, co-design should be inclusive of everyone. Historically, there has been a bias in accessibility standards presenting needs of people with physical impairments, particularly those who use wheelchairs (Hamraie Citation2017), and subsequently a narrow understanding of accessibility and disability has been engendered in design professions (Sørensen and Ryhl Citation2018). In Australia, only 4.4% of the population who identify as living with disability use a wheelchair (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2015). Greater understanding of how people with diverse sensory, cognitive, and physical abilities interact with environments and what design features facilitate usability is needed (Castell Citation2014; Edwards and Harold Citation2014; Jenkins Citation2011). As highlighted by Sørensen and Ryhl (Citation2018), people with disability are experts in their own experience of the built environment but cannot be expected to represent the needs of others. The interaction that occurs between individuals and their environment is complex and unique (Bamzar, Citation2019). As conceptualized by the Person-Environment-Occupation Model (Law et al. Citation1996), this interaction is also dynamic and influenced by the occupations or activities that a person engages in – a factor that is often overlooked in universal design (Watchorn et al. Citation2021). Effort should be made to recruit user-experts with a diverse range of attributes, ages, and abilities, and consideration given to the occupations that people will engage in within the built environment.

Development of co-design processes that are inclusive of all, particularly those with complex communication needs, cognitive, and sensory impairments can be difficult but, as noted by Raman and French (Citation2022), there is no single framework or approach that will suit all people. Rather, co-design should foreground genuine participation by those involved and open, adaptable frameworks are needed (Raman and French Citation2022). Strategies were suggested by participants in this study, and a range of embodied methodologies, artefacts, and tools are increasingly reported in literature (Rajapakse, Brereton, and Sitbon Citation2021; Vermeersch and Heylighen Citation2021). To implement and develop inclusive co-design methodologies, Raman and French (Citation2022) challenge designers to ‘shift their roles from translators, facilitators, and leaders to listeners, observers, and followers …’ and in this way, empower co-designers to ‘play, discover and cocreate their own methods for participation’ (136). Supporting findings from this study, Rieger, Herssens, and Strickfaden (Citation2020) argue that the experts on how individuals with disabilities can meaningfully participate in co-design are the individuals themselves. Further development and critique of methodologies that facilitate genuine participation and do not place excessive demand on user-experts is needed.

Design processes are associated with tangible outputs, such as a functional building, and intangible outcomes, such as expressions of creativity, aesthetics, innovation, and emotion (Pressman Citation2012). Similarly, participatory design provides opportunity for outcomes to transcend beyond design outputs to include building capacity of individuals and, at a broader level, strengthen community responsibility, connection, ownership and pride (Day and Parnell Citation2003; Drain, Shekar, and Grigg Citation2021; Raman and French Citation2022; Steen Citation2013; Trischler, Dietrich, and Rundle-Thiele Citation2019). Findings from this study support the notion that co-design can lead to positive outcomes at individual and community levels and that participation of people with disability strengthens the generation of ideas that can enhance universal design. Yet, despite co-design being perceived positively, findings from this study suggest that the intended outcomes and motivations of those organising co-design processes are unclear and that, at times, co-design can be perceived to be driven only by notions of compliance. Education on universal design and co-design was called for as a means of enhancing knowledge, skills, and attitudes of design professionals. This reflects past research findings (Hitch et al. Citation2012) and supports international efforts in this field, such as the introduction of mandated education on inclusive design by the Royal Institute of British Architects (Citation2022).

Participation of user-experts in design also raises ethical considerations. If co-design processes are not genuine and transparent, people may experience frustration, sadness, and disillusionment. Beyond personal impact, negative experiences are likely to result in wasted resources and missed opportunities to enhance project outcomes. Although the ethics of participatory design have been considered previously by Kelly (Citation2019) and Steen (Citation2013), greater exploration of these concepts as they relate to participation of people with disabilities is needed. In particular, the involvement of people with cognitive and sensory impairments in co-design processes is under-researched (Hendriks, Slegers, and Duysburgh Citation2015) and issues relating to informed consent, communication methods, reimbursement, and collaborative decision-making processes require further exploration (Hendriks, Slegers, and Duysburgh Citation2015; Imrie and Luck Citation2014; Jones Citation2014).

Limitations

Study limitations are noted and should be considered. Firstly, although this study did not seek to achieve a representative sample, there are notable imbalances in participant location, disability experience, gender, age, and occupational group. As the sample included only Australian-based participants, findings may not generalise to other geographical and socio-political contexts. It is plausible that, due to being emotionally connected to the topics under investigation, people with experience of disability were more likely to participate than those without. The predominance of females aged over 45 years is noted and, in Australia, may reflect an older, female dominated disability and allied health workforce (National Disability Services (NDS) Citation2020). Secondly, ethical requirements of this study restricted participation to people who could provide informed consent. Consequently, this excluded people with significant cognitive impairment and further research with this population is needed. Thirdly, the subjective nature of findings and potential for recall bias is acknowledged. Finally, workshop participants were not asked to describe project details, such as scale, location, or participant role(s), when describing co-design experiences. Such details may have helped in the phenomenological interpretation of data. Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable insights into participation of people with disabilities in co-design and universal design processes and maintains rigour in its methodology and reporting.

Conclusion

This study sought to explore stakeholder perceptions and experiences on the role of people with disabilities in co-design and universal design. Findings emphasise that, for effective implementation, these processes must be carefully planned, genuine, and transparent to all involved. There is a need for project managers and designers to explicate roles and expectations to user-experts and, more broadly, there is a call for greater advocacy to include people with diverse abilities in the co-design and universal design of public buildings. To maximise the effectiveness of these efforts, there is a need for education to aid practitioners in applying these concepts.

Participation of people with disabilities in co-design allows valuable contributions to be made toward universal design and fosters opportunity to build individual capacity, influence attitudinal change, and generate positive community outcomes. Importantly, as Sarmiento-Pelayo (Citation2015) argued, participation of people with disabilities in co-design also provides opportunity to empower a group of people who have historically faced oppression and discrimination from inaccessible environments – an outcome with potential to incite valuable social change.

Ethics statement

This study received ethics approval from Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (DUHREC) (Project ID: 2019-023). All data were collected, analysed, and stored in accordance with ethical guidelines for research involving human participants and all people who contributed to this study provided informed consent to participate.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the individuals who generously gave their time and expertise to participate in workshops for this research project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alase, A. 2017. “The Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA): A Guide to a Good Qualitative Research Approach.” International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies 5 (2): 9. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.5n.2p.9

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2015. 4430.0 – Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings. Australian Bureau of Statistics. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/4430.0main+features202015.

- Bamzar, R. 2019. “Assessing the Quality of the Indoor Environment of Senior Housing for a Better Mobility: A Swedish Case Study.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 34 (1): 23–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-018-9623-4

- Barnes, E. 2016. The Minority Body: A Theory of Disability, Studies in Feminist Philosophy Series. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bianchin, M., and A. Heylighen. 2017. “Fair by Design. Addressing the Paradox of Inclusive Design Approaches.” The Design Journal 20 (Suppl 1): S3162–S3170. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1352822

- Bickenbach, J. E., S. Chatterji, E. M. Badley, and T. B. Ustun. 1999. “Models of disablement, universalism and the International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps.” Social Science & Medicine 48 (9): 1173–1187. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00441-9

- Bigby, C., and P. Frawley. 2015. “Conceptualizing Inclusive Research – A Participatory Research Approach with People with Intellectual Disability: Paradigm or Method?” In Participatory Qualitative Research Methodologies in Health, edited by G. Higginbottom and P. Liamputtong, 136–160. London: SAGE Research Methods.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2013. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: SAGE.

- Campbell, F. K. 2019. “Precision Ableism: A Studies in Ableism Approach to Developing Histories of Disability and Abledment.” Rethinking History 23 (2): 138–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642529.2019.1607475

- Castell, L. 2014. “Building Access for People with Intellectual Disability, Dubious Past, Uncertain Future.” Facilities 32 (11/12): 675–684. https://doi.org/10.1108/F-03-2012-0017

- Clement, F., W. Harcourt, D. Joshi, and C. Sato. 2019. “Feminist Political Ecologies of the Commons and Commoning (Editorial to the Special Feature).” International Journal of the Commons 13 (1): 1. https://doi.org/10.18352/ijc.972

- Coleman, R. 1994. “The Case for Inclusive Design an Overview.” 12th Triennial Congress. International Ergonomics Association and the Human Factors Association of Canada, Toronto, Canada.

- Combrinck, C., and C. J. Porter. 2021. “Co-Design in the Architectural Process.” Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research 15 (3): 738–751. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARCH-06-2020-0105

- Crenshaw, K. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43 (6): 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

- Creswell, J. 2013. Qualitative Research and Research Design. Choosing among Five Approaches. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Sage Publications Incorporated.

- Cruickshank, L., G. Coupe, and D. Hennessy. 2013. “Co-design – Fundamental Issues and Guidelines for Designers: Beyond the Castle Case Study.” Swedish Design Research Journal 10: 48–57. https://doi.org/10.3384/svid.2000-964X.13248

- Day, C., and R. Parnell. 2003. Consensus design. Oxford: Routledge.

- Drain, A., A. Shekar, and N. Grigg. 2021. “Insights, Solutions and Empowerment: A Framework for Evaluating Participatory Design.” CoDesign 17 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2018.1540641

- Edwards, C., and G. Harold. 2014. “DeafSpace and the Principles of Universal Design.” Disability and Rehabilitation 36 (16): 1350–1359. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.913710

- Fleck, J. 2019. Are You an Inclusive Designer? Milton, UK: RIBA Publications.

- Gaete, C., M. A. Ersoy, D. Czischke, and E. Van Bueren. 2022. “A Framework for Co-Design Processes and Visual Collaborative Methods: An Action Research Through Design in Chile.” Urban Planning 7 (3): 363–378. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v7i3.5349

- González-Hidalgo, M., and C. Zografos. 2020. “Emotions, Power, and Environmental Conflict: Expanding the ‘Emotional Turn’ in Political Ecology.” Progress in Human Geography 44 (2): 235–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518824644

- Hamraie, A. 2013. “Designing Collective Access: A Feminist Disability Theory of Universal Design.” Disability Studies Quarterly 33 (4): 4–4. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v33i4.3871

- Hamraie, A. 2016. “Universal Design and the Problem of "Post-Disability" Ideology.” Design and Culture 8 (3): 285–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2016.1218714

- Hamraie, A. 2017. Building Access: Universal Design and the Politics of Disability. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Hendriks, N., K. Slegers, and P. Duysburgh. 2015. “Codesign with People Living with Cognitive or Sensory Impairments: A Case for Method Stories and Uniqueness.” CoDesign 11 (1): 70–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2015.1020316

- Heylighen, A., J. Schijlen, V. Van der Linden, D. Meulenijzer, and P. W. Vermeersch. 2016. “Socially Innovating Architectural Design Practice by Mobilising Disability Experience. An Exploratory Study.” Architectural Engineering and Design Management 12 (4): 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/17452007.2016.1172197

- Heylighen, A., V. Van der Linden, and I. Van Steenwinkel. 2017. “Ten Questions Concerning Inclusive Design of the Built Environment.” Building and Environment 114: 507–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2016.12.008

- Higginbottom, G. 2015. Participatory Qualitative Research Methodologies in Health. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Hitch, D., H. Larkin, V. Watchorn, and S. Ang. 2012. “Community Mobility in the Context of Universal Design: Inter-Professional Collaboration and Education.” Australian Occupational Therapy Journal 59 (5): 375–383. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2011.00965.x

- Imrie, R., and R. Luck. 2014. “Designing Inclusive Environments: Rehabilitating the Body and the Relevance of Universal Design.” Disability and Rehabilitation 36 (16): 1315–1319. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.936191

- Jenkins, G. 2011. “The Challenges of Characterizing People with Disabilities in the Built Environment.” OT Practice 16 (9): 1–8.

- Jenkins, P. 2009. “Concepts of Social Participation in Architecture.” In Architecture, Participation and Society, edited by P. Jenkins and L. Forsyth, 9–22. London, UK: Routledge.

- Jones, P. 2014. “Situating Universal Design Architecture: Designing with Whom?” Disability and Rehabilitation 36 (16): 1369–1374. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.944274

- Kelly, J. 2019. “Towards Ethical Principles for Participatory Design Practice.” CoDesign 15 (4): 329–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2018.1502324

- Larkin, H., D. Hitch, V. Watchorn, and S. Ang. 2015. “Working with Policy and Regulatory Factors to Implement Universal Design in the Built Environment: The Australian Experience.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12 (7): 8157–8171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120708157

- Law, M., B. A. Cooper, S. Strong, D. Stewart, P. Rigby, and L. Letts. 1996. “The Person-Environment-Occupational Model: A transactive Approach to Occupational Performance.” Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 63 (1): 9–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841749606300103

- Liamputtong, P. 2020. Qualitative Research Methods. Melbourne: Oxford.

- Mace, R. 1985. “Universal Design. Barrier-Free Environments for Everyone.” Designers West 33 (1): 147–152.

- Malterud, K., V. D. Siersma, and A. D. Guassora. 2016. “Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies.” Qualitative Health Research 26 (13): 1753–1760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315617444

- Molnar, S., and K. Palmås. 2022. “Dissonance and Diplomacy: Coordination of Conflicting Values in Urban Co-Design.” CoDesign 18 (4): 416–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2021.1968441

- National Disability Services (NDS). 2020. NDS Workforce Census Key Findings. National Disability Services. https://www.nds.org.au/images/news/NDS-Workforce-Census-Key-Findings-Dec-2020.pdf.

- Oliver, M. 1990. The Politics of Disablement: A Sociological Approach. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Ostroff, E. 1997. “The User as Expert: Mining Our Natural Resources.” Innovation, the Quarterly Journal of the Industrial Designers Society of America 16 (1): 33.

- Patrício, L., and R. Fisk. 2013. “Creating New Services.” In Serving Customers: Global Services Marketing Perspectives, edited by R Russell-Bennett, R. P. Fisk, and L. Harris, 185–207. Melbourne: Tilde University Press.

- Patton, M. Q. 2015. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Incorporated.

- Persson, H., H. Åhman, A. A. Yngling, and J. Gulliksen. 2015. “Universal Design, Inclusive Design, Accessible Design, Design for All: Different Concepts—One Goal? On the Concept of Accessibility—Historical, Methodological and Philosophical Aspects.” Universal Access in the Information Society 14 (4): 505–526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-014-0358-z

- Pressman, A. 2012. Designing Architecture: The Elements of Process. Oxon, UK: Routledge.

- Pritchard, E. 2014. “Body Size and the Built Environment: Creating an Inclusive Built Environment Using Universal Design.” Geography Compass 8 (1): 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12108

- Rajapakse, R., M. Brereton, and L. Sitbon. 2021. “A Respectful Design Approach to Facilitate Codesign with People with Cognitive or Sensory Impairments and Makers.” CoDesign 17 (2): 159–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2019.1612442

- Raman, S., and T. French. 2022. “Enabling Genuine Participation in Co-Design with Young People with Learning Disabilities.” CoDesign 18 (4): 431–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2021.1877728

- Rieger, J., J. Herssens, and M. Strickfaden. 2020. “Spatialising Differently Through Ability and Techné.” CoDesign 16 (2): 135–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2018.1531134

- Ringaert, L. 2001. “User/Expert Involvement in Universal Design.” In Universal Design Handbook, edited by Wolfgang F. E. Preiser and E Ostroff, 6.1–6.14. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). 2022. “Inclusive Design the Standard to Reach.” https://www.architecture.com/knowledge-and-resources/knowledge-landing-page/inclusive-design-the-standard-to-reach.

- Sánchez De La Guía, L., M. Puyuelo Cazorla, and B. De-Miguel-Molina. 2017. “Terms and Meanings of “Participation” in Product Design: From “User Involvement” to “Co-Design.” The Design Journal 20 (Suppl 1): S4539–S4551. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1352951

- Sanders, E. B. N., and P. J. Stappers. 2008. “Co-creation and the New Landscapes of Design.” CoDesign 4 (1): 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880701875068

- Sarmiento-Pelayo, M. P. 2015. “Co-Design: A Central Approach to the Inclusion of People with Disabilities.” Journal of the Faculty of Medicine of the National University of Colombia 63: 149–154.

- Shouman, B., A. A. E. Othman, and M. Marzouk. 2022. “Enhancing Users Involvement in Architectural Design using Mobile Augmented Reality.” Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 29 (6): 2514–2534. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-02-2021-0124

- Smith, J. A., and V. Eatough. 2007. “Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis.” In Analysing Qualitative Data in Psychology edited by E. Lyons and A. Coyle, 35–50. London: Sage Publications.

- Sørensen, R., and C. Ryhl. 2018. “Responding to Diversity Including Disability.” Design as a catalyst for change: Proceedings of DRS 2018 International Conference.

- Steen, M. 2013. “Co-Design as a Process of Joint Inquiry and Imagination.” Design Issues 29 (2): 16–28. https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00207

- Todres, L., and I. Holloway. 2004. “Descriptive Phenomenology. Life World as Evidence.” In New Qualitative Methodologies in Health and Social Care Research, edited by F. Rapport, 79–98. London: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Trischler, J., T. Dietrich, and S. Rundle-Thiele. 2019. “Co-Design: From Expert- to User-Driven Ideas in Public Service Design.” Public Management Review 21 (11): 1595–1619. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1619810

- Tucker, R., D. Kelly, L. Johnson, U. De Jong, and V. Watchorn. 2022. “Housing at the fulcrum: A systems approach to uncovering built environment obstacles to city scale accessibility and inclusion.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 37: 1179–1197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-021-09881-6.

- United Nations. 2007. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). New York: United Nations.

- Vermeersch, P. W., and A. Heylighen. 2021. “Involving Blind User/Experts in Architectural Design: Conception and Use of More-Than-Visual Design Artefacts.” CoDesign 17 (1): 50–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2018.1557696

- Watchorn, V., D. Hitch, C. Grant, R. Tucker, K. Aedy, S. Ang, and P. Frawley. 2021. “An integrated literature review of the current discourse around universal design in the built environment - is occupation the missing link?” Disability and Rehabilitation 43 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1612471.

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2002. Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health ICF. Geneva: WHO.