Abstract

This paper explores how design students overcome various obstacles they encounter during their design processes. By studying the processes of three textile design students during their weaving course, we investigated the forces and agencies that help overcome or accommodate obstacles by developing solutions. The interview data showed that while learning and advancing a skill, in our case weaving, various obstacles emerge through direct and indirect interactions. By recognizing how to position themselves and build relationalities, students start working with various agencies to develop ways of being with these obstacles. Our findings propose that experiencing obstacles fosters the learning process of students by leading them to actively look for ways of being with other elements while becoming more skillful in their practice.

Introduction

Education in and for the twenty first century should prepare students for the unknown-ness of the complex world, and multiple interpretations of situations (Barnett Citation2004). With such uncertainties, education cannot merely build knowledge or skills, but it should tackle the being of students as an ontological task to challenge and encourage students in the formation of their authentic selves. In this way, Barnett argues, students can gain the qualities needed to operate in ‘the gap between one’s actions and one’s limited grounds for those actions’ (260).

The rapid changes and complexities generate obstacles to be tackled creatively. The unknown obstacles highlight the cruciality of growing professionally and personally. These discussions show that education needs to go beyond teaching domain-specific knowledge and skills to bring together broader competencies of critical thinking and problem solving, communication and collaboration, creativity, and self-efficacy (Binkley et al. Citation2012). Thus, the skills related to tackling obstacles and learning from failures or overcoming failures become important assets for students in preparing for their professional life (Sawyer Citation2019). Studying various complexities and challenges that students experience in their courses, and ways of overcoming these situations can provide insights for understanding how learning takes place in complex settings and how these experiences might be transferred to upcoming learning and working contexts.

Accordingly, in this article, we examine the obstacles that MA-level textile design students encountered during a weaving studio course – Woven Fabrics. The main learning outcome of this course is to gain the ability to work with various weaving techniques, tools, materials and skills. While learning a new skill and developing course projects, students face obstacles, and developing solutions becomes an important aspect of gaining competency and achieving originality. To examine the role of obstacles and solutions, this study addresses the following research question: What kind of obstacles did design students encounter and how did they overcome these emerging obstacles during the textile design course?

This article conceptualizes learning as a sociomaterial entanglement, and unplanned or deliberate obstacles as part of learning experiences. We propose that experiencing obstacles leads students to develop their competencies in relation to other elements of the sociomaterial entanglements.

The role of obstacles in learning and design

Despite learning being an activity of the self in terms of facilitating personal progress in a certain topic, it is hardly ever accomplished individually. Learning emerges in a complex non-linear process in which human actors and the material environment produce and shape each other (Hakkarainen and Seitamaa-Hakkarainen Citation2022). Similarly, learning to design is intertwined with materiality: even when students develop their individual projects alone, they are constantly in contact with other things, such as their materials, tools, or peers (Mäkelä and Aktaş Citation2023). Accordingly, we adopted a sociomaterial perspective to study learning in an educational context. Sociomateriality proposes examining social and material elements as a unified entity that creates the learning environment and affects the learning experience (Fenwick, Nerland, and Jensen Citation2012).

Studying the experiences of students through the sociomaterial lens allows one to trace ‘how knowledge, knowers and known (representations, subjects and objects) emerge together with/in activity’ (Fenwick, Nerland, and Jensen Citation2012, 7). In this framing, the world is understood as active, whereby humans and nonhumans embed agencies to act individually and collectively (Barad Citation2003; Bennett Citation2010; Pickering Citation1993). Barad (Citation2003) refers to nonhuman things as entities that embed the power of making new configurations to discuss the sociomaterial entanglements of humans and nonhumans. Considering the power that nonhumans hold, Bennett (Citation2010) proposes matter as vibrant and creative for it can make a change in its surroundings. According to Bennett, things can make an impact individually or as part of an assemblage, and these impacts can vary depending on the materialities in those situations. In this context, and following the current discourse, we refer to the agency of things as the capacities to cause new configurations (Bennett Citation2010; Pickering Citation1993).

Fenwick (Citation2015, 91) argues that when the world is understood with different agencies, learning can become a way to attune to changes and influences within situations, and to prompt alternative actions. This perspective shifts learning from ‘preparation and acquisition of competency to learning as attunement, response and even interruption’ (ibid.).

These attunements, responses and interruptions occur at times through encounters with various obstacles that emerge from various sources and forces. While discussing practices and how humans participate in them, Pickering (Citation1993) proposes that humans may encounter obstacles that lead them to revise their initial intentions. In the context of learning, these activities or resistances can occur as a result of the mismatch between the intentions of students and the actions and qualities of other entities. By accommodating these resistances (Pickering Citation1993) and reflecting on them, one can develop ways of being with them in various ways. Throughout these interactive encounters, the ideas and materials transform, as well as the practicing person (Aktaş Citation2020; Pickering Citation1993). As a person develops their competency, they gain insights to evaluate those obstacles emerging from the making process (Aktaş Citation2020). This ability allows them to understand how to negotiate with various obstacles and actions of nonhuman participants to develop intentions-in-action as well as collaboratively create an artefact with all the participating entities (ibid.). As a result, makers think through making, which leads to developing technically, creatively, and personally. This process emerges like a dialogue through reflections on various experiences as an artefact emerges (Mäkelä Citation2007). Like sociomaterial interactions, while thinking through making, practitioners entangle with the participating entities, occurrences, materials, and tools and students develop their own learning journeys.

Some of these occurrences regard to obstacles. Obstacles in education can relate to a deliberate, intentional and constrained process (Sawyer Citation2019). The combination of the open-endedness of creative tasks and students’ lack of domain-specific knowledge and skills easily lead to encountering obstacles in their projects that cause uncertainty and increase tensions regarding the emerging artistic agency (Sheridan, Zhang, and Konopasky Citation2022). Indeed, in design education, obstacles are seen as an elemental part of learning since design projects are often open-ended. When the course assignment is open, students are guided to go through a deeper process of learning and reflection as they internalize material and embodied knowledge (Sheridan, Zhang, and Konopasky Citation2022; Seitamaa-Hakkarainen Citation2022). In these open-ended processes, teachers and studio masters often help students overcome the obstacles by supporting them in developing their professional artistic agency and their capacity to engage in creative processes, in cultivating their expressive intentions, and in envisioning how things could be (Sheridan, Zhang, and Konopasky Citation2022; Sawyer Citation2019).

Additionally, students can also encounter obstacles that do not necessarily stem from the course design but from the fact that learning is a socially and materially connected experience, and various elements can affect its emergence (Fenwick and Nerland Citation2014). Following the idea that learning takes place through sociomaterial entanglements, we study interruptions as obstacles that emerge from the broad sociomaterial situations of how learning takes place. In this sense, we have a broad understanding of obstacles that goes beyond course limitations and pre-designed tasks. We perceive obstacles as situations that create friction, hardship, confusion, problems or unknown situations in executing the intended goal. We studied the emergence of such obstacles and how students overcome or accommodate them as they gain competence.

Woven fabrics and student interviews

This article is based on qualitative data collected during the four-week course ‘Woven Fabrics’ at Aalto University, Finland. The course is offered to first-year master’s students in the Fashion, Clothing and Textile program. The course welcomes students with a textile design degree from national and international institutions, and those who have never studied weaving or textiles before. The course is designed for students from different competencies to familiarize them with the specific textile thinking of the program. Throughout the course, students gain technical knowledge and a basic understanding of weaving techniques and woven fabrics to cultivate their expertise in the context of textile design.

The course takes place in the weaving workshop, accompanied by classroom lectures to introduce various weave structures with lecture slides, material samples, and diagrammatic explanations. Throughout the course, they work with a moodboard as a visual cue to explore various woven structures and textures.

Students work on 10 looms that are set up before the course begins by the course teachers and workshop masters. Each loom offers different woven structures (e.g. plain, basket, satin weaves, and twill) with varied warp material (e.g. silk, cotton, wool). Students are not able to change the woven structure – the tie-up – the warp materials, or the warp size, and can only work with nude and neutral tones (). These preconditions act as constraints on the open-ended design task and lead students to create texture and express their visuals by working with the woven structure rather than focusing on creating patterns merely via colors. Students are also introduced to WeavePoint (a computer-aided weave design program) and digital looms.

Throughout the course, students work with each loom at least twice and create a minimum of 20 swatches as they experiment with the woven structures. By the end of the course, students create two collections by editing those swatches in groups. Additionally, students learn to draw different kinds of diagrams that show the weave structure and cloth diagram to be able to replicate the samples. The information for each swatch is documented via info cards to showcase the skill level of communication in the textile language. The course progresses through independent work in the weaving workshop, individual tutoring with teachers, one mid-critique and a final critique where each student presents their final collections.

Following the student processes: Data analysis

During the four weeks, we collected our data through ethnographic methods. From the beginning of the course, three researchers followed the course meetings, classroom lectures, workshop activities, and critique sessions. Additionally, the first author of this article enrolled in the course and acted as a participant observer to collect data, participating in each class. The second author conducted observations and interviews with students and gathered her own field notes. We invited three students – Elina, Janneke, and Anusuya – to participate in the study, and closely followed the processes of these students by taking photographs, conducting observations, and having interviews twice per week. In these interviews, we asked the students the following questions repeatedly: What have the last few days been like? What type of materials and tools did you use? On which looms and in which classrooms or workshops did you work? What was the high and low points of the past few days? The interviews lasted between 8 and 30 min, and each student took part in a minimum of six interviews. The field notes and insights that were gathered by the two authors of this article supported the analysis when needed.

The analysis of the interview transcripts resembled qualitative thematic content analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2012). With its flexibility in taking various approaches, thematic analysis enables the generation of findings representing the voices of research participants by elaborating on information related to their experiences, reasoning, reflections, and questions (ibid.). Following Braun and Clarke's (Citation2012) descriptions, we applied an inductive bottom-up approach that led to generating insights driven by the interview and observation data. First, we went through the data to gain initial insights about the context of perceived obstacles, and the directions the students were led. Guided by the initial insights, the analysis followed seven steps:

Step 1: Identifying the hardship and obstacles that the students encountered.

Step 2: Generating codes to refer to the obstacles. Although students can refer to similar issues as limitations, the context in which they experience the situation can vary. For example, one student referred to the pre-defined woven structure as a design obstacle while to a more experienced student, it proposed a material obstacle. Reducing the codes to patterns too quickly would omit these nuances. Thus, while identifying the codes, we also identified the source of an obstacle and the things it mainly related to.

Step 3: Identifying solutions that students developed or chose to overcome the obstacles. Frequently, obstacles appeared with solutions that the students developed. Identifying solutions revealed why certain situations were perceived as obstacles, as students often explained the two in entangled ways.

Step 4: Developing codes for solutions. Similar to obstacles, solutions are developed depending on the context and personal knowledge of the students. To preserve these specific conditions, we generated codes for each solution and identified what each of them related to.

Step 5: Creating a relational map for each student to illuminate the contexts that the obstacles and solutions emerged from with codes, sources, and relations. The large version of the relational map enmeshed all the obstacles and solutions that were identified and their relations to various sources, forces and agencies (Steps 6 and 7).

Step 6: Identifying the forces that led to these situations. While examining the obstacles that students encountered, we studied the sources that these obstacles stemmed from and the causes of those situations. We grouped these sources and causes as forces emerging from a wider context. Here, referring to forces highlights situations that created actions and active changes that led the students to exert an impact on their encounters. Deleuze and Guattari (Citation2004) proposed that an essential relationship between materials and forces exists in life. In this relationship, all materials and their properties enmesh with forces of the cosmos to reciprocally create each other and the things that exist. Taking this further, Ingold (Citation2010) proposed joining with those forces and following flows and transformations of materials as a way of form creation in creative practice and as a way of being in the world. In our study, we identified the forces as things that students actively encountered and that affected their workflow with materials. Then, we grouped the information to identify what type of conditions and elements create the contexts for obstacles and solutions ().

Table 1. List of identified forces (1.a) and agencies (1.b) involved in learning.

Step 7: Identifying how these forces were triggered by agencies, including human agencies and the agencies of nonhumans. Human agency functions as an ability to connect past and future projects through unforeseen events and leads the capacity to imagine alternative promises for the future (Emirbayer and Mische Citation1998). Nonhuman agency tackles vitality in things and entities that empowers them to make a change in their surroundings. As discussed earlier in this article, we perceive nonhuman agency as the capacity embedded in things to affect humans and their way of thinking, acting, or behaving (Aktaş Citation2020). In the analysis, we identified the power dynamics that created those causes and forces as the agencies that lead to experiencing obstacles or developing solutions ().

Although the seven steps may initially seem to overcomplicate the analysis, the identified obstacles and solutions were nuanced, and to preserve nuances among students who came from different cultural and educational backgrounds we followed a meticulous process of involving several steps. First, we analyzed the transcripts pertaining to each student separately. A combined analysis was conducted after identifying the forces and agencies involved.

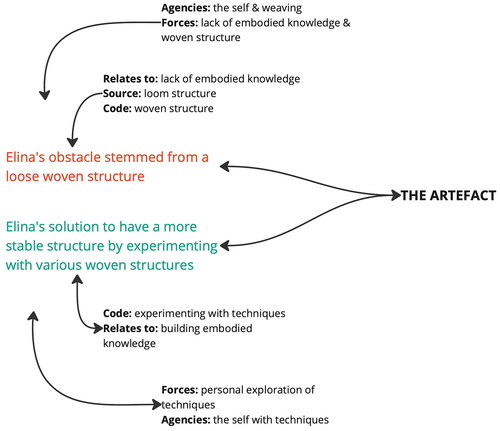

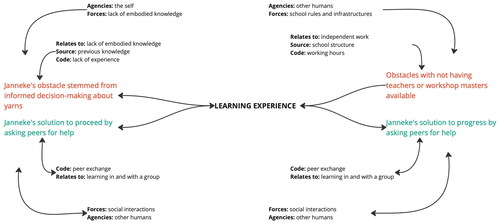

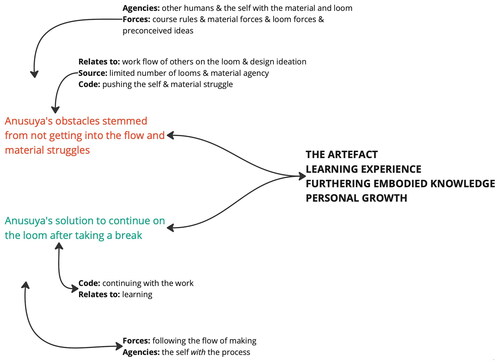

In the next section, we share excerpts from each student, showing how a particular obstacle was encountered and overcome (). To facilitate a clear discussion, these excerpts show singled-out agencies and forces, and how they lead to obstacles and solutions. As oftentimes, the agencies and forces regarding obstacles precedent the projects, the arrows are one directional showing the limited influence of the students over them. Immediately after the obstacles are experienced, students search for solutions. These solutions are also fostered by agencies and forces. However, students gain a more active role in developing solutions. Therefore, the relationship between solutions and the students are more reciprocal, as shown with double-headed arrows. In this visual explanation, the forces and agencies are not a unified entity, but they are grouped to show their interwovenness, as certain agencies can lead to various forces. As the obstacles and solutions are experienced and lived through by the students, their becoming one leads to an outcome, which differs in every situation.

Obstacles and agencies: Examples from the data

The analysis identified various types of obstacles (). For example, the course design implies constraints on student projects, such as the colors and pre-defined woven structures, as well as limitations in the weaving workshop, such as sharing the looms and fixed workshop hours. Obstacles emerging from working in a workshop concerned practicalities. Other obstacles included daily routines such as arranging dinner, managing time, and balancing free time and study time. Besides these, in our weekly interviews, students frequently mentioned obstacles related to the creative process, school rules, or social interaction.

The findings from the analysis show that obstacles are individually experienced depending on the context. Although students may refer to similar situations as obstacles, the reason for those situations becoming an obstacle depends on the students’ subjective experiences. Thus, obstacles are shaped by the self within a context to a large degree. The second finding shows that coming up with solutions also depends on the self and the context to a large extent. However, unlike experiencing obstacles, when students refer to their solutions, they refer to other things almost as emphatically as their personal experiences. The way students refer to those solutions often indicates that as they develop solutions, they move away from merely participating in a situation to becoming a part of it. Thus, the third finding is that developing solutions relies on internalizing sociomaterial experiences and undergoing personal growth. These findings highlight the sociomaterial connections of learning in the given example.

To elaborate on these findings, we will discuss three instances and various agencies involved in experiencing obstacles and overcoming them. These instances from three students will explain further some of the identified forces and agencies from . We selected these instances since those agencies and forces that we identified during our analysis were the most commonly occurring ones.

Example 1: Agencies of weaving and techniques

While learning a new practice, students explore the capacities of the practice, techniques, materials and tools to understand what they can do with those entities (). In the data, embodied knowledge and previous experiences emerge as the most common forces and agencies in encountering obstacles and developing solutions. Students refer to their own selves in relation to obstacles and solutions about domain-specific knowledge, skills and competences, personal motivations and explorations. The bodily experiences, embodied knowledge, ideation, or personal initiations are understood as a unified entity as the self.

For instance, Elina encountered an obstacle with one of the pre-set loom structures. Although this experience was challenging, it was also one of the main learning expectations of the course: to understand woven structures and gain the ability to experiment with them. While trying to develop a working technique with a loom, Elina explained her need for experimentation:

Obstacle: ‘I felt that this is already loosey-goosey and it has no structure … So if I’m just doing these … with this kind of yarn doing this basket weave, I think it will fall apart’.

Solution: ‘So I thought … the plain weave should actually work best for this. I’m basically going to have these squares in between…I like experimenting with (and) mastering the technique and craft … (I am) doing this experiment with … a good technique, … and thinking about this warp and how it’ll behave when we take it off’ (interview excerpt, 25.11.2021).

Example 2: Agencies of peers and the teaching team

During the learning process, students always interact with other people, sometimes directly, such as by asking peers questions, and sometimes indirectly, such as by being influenced by the decisions that the school board makes about working hours. Since the school workshops close at a certain time, the students work without the supervision of a workshop master for some time. When faced with obstacles or problems during those times, the solution lies in collaborating and exchanging ideas with peers, which leads to learning with and in a community where peers support each other (). Accordingly, the agencies of other people involved was another commonly occurring agency. These can be peers, workshop masters, and teachers, people who are directly involved in learning experiences, as well as the school board, friends from outside the course, or previous designers as sources of inspiration. In these instances, the most effective role is often played by peers. Janneke, for example, a weaving novice, refers to the importance of peer exchange:

Obstacle: ‘(at times) I really don’t know which yarn to choose; it can be anything’.

Solution: ‘They (some of the peers) have more, … experience on the loom. So sometimes they help me with threads or by tightening the warp …’ (interview excerpt, 23.11.2021).

Obstacle: (not having masters or teachers on hand all the time in the workshop)

Solution: ‘S. (a peer with a textiles degree) explained to me how this loom works. Because the teachers had already left’ (interview excerpt, 25.11.2021).

These agencies can emerge from various contexts and obstacles, such as not knowing enough about the materials or not knowing how to use the loom to advance the woven textile. Engaging in social interaction with other people can affect various aspects of practice. In our data, this mostly appeared to affect the learning experience of students by enabling self-communication, reflection and peer support (). Thus, the solution emerges from building dialogue with others.

Example 3: Agencies of looms, materials and the process

A final example among the agencies is the significant impact of material agency on the process, design ideation and outcome. In Anusuya’s interviews, the material and the loom were mentioned frequently when she discussed her progress with the project and decision-making. Having a background in textiles and weaving, she often described her process in relation to her materials, looms, woven structures and outcomes. In one interview, Anusuya shared various problems she had encountered one night with a particular loom that resulted in an obstacle that involved getting into the flow of making:

Obstacle: ‘I was doing it, and it just wasn’t getting done. … And then one of the yarns here, this black one, … I spun it, I think twice, or three times (). And it kept forming these knots and getting stuck in this metal thing. And it just wasn’t working at one point. And I was so frustrated. I was like, no, I have to finish it because the next person needs to weave. … the thread was kind of just not cooperating at one point. And then, … I started thinking these colours were too dull. Because I was loosening the tension both at the top and at the bottom, after a point, … everything was just moving around’ (interview excerpt, 30.11.2022).

Solution: Anusuya’s solution to this obstacle was to take a break, have a chat with her friend, and then continue working on the loom. She called this loom ‘the struggle corner’. This particular piece subsequently gained very positive feedback from the course teachers.

Figure 7. The elements involved affect the weaving process. An example from Anusuya’s process. Illustration: Aktaş, 2022.

The three examples illustrate the role of different agencies in encountering an obstacle and developing a solution. They also show that these agencies are seldom independent. Rather, things interweave to create situations for various encounters to arise. When discussing how they overcame or accommodated various obstacles, the students mostly referred to rather relational descriptions with other elements, such as processes, materials, tools, and peers. This way of explaining indicates that the sociomaterial interactions contributed to the domain-specific knowledge and personal development of the students.

Discussion: Relating to forces and agencies

The learning process is described as a sociomaterial entanglement (Fenwick Citation2015) and as an assemblage of students, teachers, classroom and course content designed to develop skills such as being adaptive, reflective, and active (Barritt, Thompson, and Woodward Citation2021). Confirming these discussions, the analysis of obstacles and solutions shows that students entangle with many elements in their learning processes in the form of forces and agencies ().

The analysis shows that as the students learned weaving, they developed a sense of understanding the practice from their own perspectives. Depending on the context of the obstacles and how they appeared, overcoming these situations supported the development of the students. The selected examples showed that finding ways to overcome or accommodate obstacles can impact the emergence of the artefact and the learning experience, and can further embodied knowledge and self-growth.

Our first finding shows that obstacles are context-dependent and situated in each person’s previous experiences. When design students are learning by doing, they can follow different learning processes depending on their proficiency levels (Yuan, Song, and He Citation2018). When the experience level is low, students tend to focus on skill development, while students with more experience tend to focus on developing skills for problem solving (ibid.). Similarly, in our data, most obstacles were related to the experience level of the student. When obstacles stemmed from material sources or practices, students referred to these situations separately from themselves, as situations that they encountered. While developing solutions, they learned how to integrate themselves into these situations. As the students gained competency and acquired domain-specific knowledge, they became part of their practice and making processes.

This was particularly clear in Elina’s and Janneke’s explanations compared to Anusuya’s since Elina and Janneke were both novices at the start of the weaving course, while Anusuya was more advanced. Initially, Elina’s and Janneke’s reflections on the obstacles they experienced were more descriptive, whereas Anusuya was able to reflect more analytically on the entire process and procedures. Over time, Elina and Janneke started reflecting more analytically in a way that built connections between various pieces of knowledge and experiences.

The second finding shows that developing solutions requires actively searching for and generating ways of relating to other elements. While studying the developed solutions, we observed that although their processes were self-driven, the students usually took actions in relation to other humans or things. Rather than coming up with an idea that is meaningful on its own, students find ways of being with other things to develop a solution. Therefore, the various agencies involved in obstacles and solutions suggest that developing one’s own ways comes about by gaining a perspective in which the student positions herself in relation to other elements. This process happens by recognizing the practice as an aggregation of many things, including the self, other humans, structures, materials, tools and the process as a whole.

When discussing the processes of making, scholars have proposed changing the perceptions from forcing a preconceived idea to following the flow of the material and, by extension, making (Ingold Citation2013). Ingold (Citation2000) proposes that artefacts emerge within the relational contexts of the mutual involvement of people and their environment. The form of the artefact comes into being through the gradual unfolding of the field of forces set up through the active and sensuous engagement of the practitioner and the material (ibid.; see also Mäkelä Citation2019). Ingold (Citation2013) discusses making processes as becoming, whereby the maker changes with the materials through interacting with them. By losing the sense of control, students could transition into a mindset of being-with where they see themselves as an elemental part of a larger unity. The perspective of being-with can provide students with a precise understanding of material behaviors, encourage them to critically review their practice, and help them build a bridge between prior and present experiences (Aktaş and Groth Citation2020).

In accordance with finding their own ways, students follow different approaches as solutions. For instance, when it comes to the limitations that they cannot change, such as the length of the course, students learn to accommodate themselves to the situations. With other limitations, such as working with a slippery thread, they change their way of approaching this limitation to find a way to be with the situation in a fruitful way. Overall, to overcome an obstacle, students often search for ways of being with other elements, such as being with techniques to experiment, being with peers to learn, or being with the process to immerse themselves in the information coming from other participating entities. Thus, students learn to follow active togetherness with nonhumans rather than perceiving them as static entities.

The third finding is that experiencing obstacles and developing solutions happen through internalizing sociomaterial interactions. Design processes emerge differently for each person since, based on the designer’s personal knowledge and perception of the topic, they develop what to do, how and when in their own way (Dorst and Cross Citation2001). As designers develop personal ways of working with and interpreting their tools and sources, they also advance their expertise and design thinking (Omwami, Lahti, and Seitamaa-Hakkarainen Citation2020). Our findings show that people and things beyond the self also shape this individual process. The creative agency in the process of learning is a combination of several creative agencies such as the learner, peers, teachers, materials, tools, and the entire process of working. The analysis shows that while students develop their creative agencies, they tend to remove themselves from the center and pursue building relationships with others. As they get to know the agencies that create obstacles, they also learn how to be with agencies to develop solutions. As the three selected examples show, in the process of learning, students go through personal, interpersonal, and material experiences. When they are able to entangle these experiences, learning becomes a fruitful one that contributes to the being of the students.

One hidden obstacle entails making sense of the extensive experiences emerging from learning itself and going through the design process, which is often unknown, explorative, and frustrating. Making, designing, managing the process, and going through the course happen simultaneously and often demand most of one’s time and energy during learning. This leaves little space for reflecting on and digesting the experiences to make sense of what is being learnt. One supportive finding is that room for reflection assists the learning experience. Previously, scholars discussed the role that writing plays in fostering students’ learning, designing, thinking, reflecting and affections (Gelmez and Tüfek Citation2022). In the interviews, we were able to observe a similar improvement in students’ abilities in discussing their processes. After almost every interview, students stated that talking to the researchers about the past few days had helped them verbalize their ideas and feelings and contributed to recognizing and explicating their learning processes. Indeed, the reflective interviews became so helpful that at times students started sharing their processes before we initiated the interview. By adopting a reflexive position, students can gain autonomy in shaping their cognitive and perceptual development (Barritt, Thompson, and Woodward Citation2021). Voicing their experiences showed the importance of articulation and communication in advancing learning and self-awareness about what is being learned and how the design process progresses.

Conclusions

Learning has been described as an embodied and situated practice that takes place in multiple spaces and with human and nonhuman stakeholders (Mäkelä and Aktaş Citation2023). In this article, we discussed learning from a similar perspective by empirically analyzing the involvement of various elements and their role in acting as obstacles or solution generators.

Bennett (Citation2010) suggests that a person who has an intimate connection with things encounters a creative materiality. The direction in which this power takes the maker depends on the forces, affects, or agencies that are present in the process, or bodies with which they come into close contact (see also Mäkelä Citation2019). Adding further empirical evidence to this thinking, our article examined a diversity of forces that impact the creative design process via three main channels including personal, interpersonal and material realms.

We discussed the identified obstacles and solutions created by various human and nonhuman agencies as factors leading to changes and transformations. Bringing the agency discussion to the educational context is relevant as nonhuman agency highlights the active reconfigurations. Learning settings are also active and dynamic spaces where students participate in transformative experiences. Therefore, experiencing various obstacles through the agencies of participating entities, and developing personal solutions or ways of accommodating these obstacles, become an essential part of learning and developing creative agencies.

Additionally, studying the emergence of obstacles and developing solutions in response to them unravelled how designers think in action. The analysis shows that as a result of sociomaterial interactions, learning goes beyond the given time and space of a course design, and it becomes a part of students’ everyday experiences. Deliberate course designs that bring the attention to students’ course and everyday activities can lead to conscious self-observations regarding skill development and growth. Additionally, in creative processes embracing obstacles other than constraints acting as creative limits, can make a positive impact on skill acquisition that is not merely about technical growth but also about developing a personal way of practicing. Instead of bypassing or overlooking unexpected obstacles, working with them can enhance the learning experience interplaying with various creative agencies and forces. This attitude can foster creative agencies of designers and students.

When examining ways of overcoming or accommodating various obstacles, students develop their creative agencies along with other elements – human and nonhuman – in relational ways. Therefore, as they learn how to weave, they become weavers and designers. Having continuous and explicit reflective conversations (interviews in our case) can act in an educational context as important means that support students in their holistic learning process. This article shows that the sociomateriality in learning is embedded in various forces and agencies, and as one learns a new skill or practice, one also learns how to entangle within those elements.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the course teachers Prof. Maarit Salolainen and Tiina Paavilainen, and workshop master Tiina Saivo for opening the doors to their classrooms, the study participants, Anusuya, Elina, Janneke, for sharing their journey with us, and Luis Vega for his contributions to the research and data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bilge Merve Aktaş

Bilge Merve Aktaş (Ph.D.) is an independent researcher working with textile crafts to understand their power of connecting people with their environment. She examines interaction between humans and materials to understand ways of being with the world.

Anniliina Omwami

Anniliina Omwami is a doctoral researcher in craft science at Faculty of Educational Sciences, University of Helsinki. Her main research interests are to analyse the inspiration and ideation processes in individual and collaborative designing.

Pirita Seitamaa-Hakkarainen

Pirita Seitamaa-Hakkarainen (Ph.D.) is Professor of Craft Science at the Faculty of Educational Sciences, University of Helsinki. Her research interests focus on collaborative designing as well as embodied and socio-material aspects of designing.

Maarit Mäkelä

Maarit Mäkelä (Doctor of Arts) is Professor of Design at the Department of Design, Aalto University, Finland. Her own creative practice locates in the context of contemporary ceramics. Her research interest lies in creative processes, in particular, how reflective diaries and visual documentation can be utilized for capturing the personal process.

References

- Aktaş, B. M. 2020. “Entangled Fibres – An Examination of Human-Material Interaction.” Doctoral dissertation, Aalto University.

- Aktaş, B. M., and C. Groth. 2020. “Studying Material Interactions to Facilitate a Sense of Being with the World.” In Design Research Society Biannual Conference, Australia, November 14.

- Barad, Karen. 2003. “Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 28 (3): 801–831. https://doi.org/10.1086/345321

- Barnett, Ronald. 2004. “Learning for an Unknown Future.” Higher Education Research & Development 23 (3): 247–260.

- Barritt, L., S. Thompson, and M. Woodward. 2021. “(Re) considering Pedagogy–Entangled Ontology in a Complex Age: Abstraction Pedagogy and the Critical Pedagogical Importance of Art Education for Other Discipline Areas.” International Journal of Art & Design Education 40 (4): 784–793. https://doi.org/10.1111/jade.12391

- Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Binkley, M., O. Erstad, J. Herman, M. Ripley, M. Miller-Ricci, M. Rumble. 2012. “Defining Twenty-First Century Skills.” In Assessment and Teaching of 21st Century Skills, edited by E. Care, P. Griffin, and B. McGaw, 17–66. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2012. “Thematic Analysis.” In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology: Vol. 2. Research Designs, 57–71. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- de Gier, N. 2017. “A Conversation with Material.” The Design Journal 20 (sup1): S745–S753. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1353021

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 2004. A Thousand Plateaus. Translated by Brian Massumi. London: Continuum.

- Dorst, K., and N. Cross. 2001. “Creativity in the Design Process: Co-Evolution of Problem–Solution.” Design Studies 22 (5): 425–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0142-694X(01)00009-6

- Emirbayer, Mustafa, and Ann Mische. 1998. “What is Agency?” American Journal of Sociology 103 (4): 962–1023. https://doi.org/10.1086/231294

- Fenwick, Tara, and Marianne Nerland. 2014. “Introduction: Sociomaterial Professional Knowing, Work Arrangements and Responsibility. New Times, New Concepts?” In Reconceptualising Professional Learning. Sociomaterial Knowledges, Practices and Responsibilities, edited by Tara Fenwick and Marianne Nerland, 1–8. London: Routledge.

- Fenwick, Tara, Marianne Nerland, and Karen Jensen. 2012. “Sociomaterial Approaches to Conceptualising Professional Learning and Practice.” Journal of Education and Work 25 (1): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2012.644901

- Fenwick, Tara. 2015. “Sociomateriality and Learning: A Critical Approach.” In The SAGE Handbook of Learning, edited by David Scott and Eleanore Hargreaves, 83–93. London: SAGE.

- Gelmez, Kerim, and Tuğba E. Tüfek. 2022. “Locating Writing in Design Education as a Pedagogical Asset.” The Design Journal 25 (4): 675–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2022.2088174

- Hakkarainen, K., and P. Seitamaa-Hakkarainen. 2022. “Learning by Inventing: Theoretical Foundations.” In Invention Pedagogy: The Finnish Approach to Maker Education, edited by Tiina Korhonen, Kaiju Kangas, and Laura Salo, 15–27. Oxon, UK: Routledge.

- Ingold, Tim. 2000. The Perception of the Environment. London: Routledge.

- Ingold, Tim. 2010. “Bringing Things to Life: Creative Entanglements in a World of Materials.” Realities Working Papers 15: 1–14.

- Ingold, Tim. 2013. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London: Routledge.

- Mäkelä, M. 2007. “Knowing through Making: The Role of the Artefact in Practice-Led Research.” Knowledge, Technology & Policy 20 (3): 157–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12130-007-9028-2

- Mäkelä, M. 2019. “A Nourishing Dialogue with the Material Environment.” In Design & Nature: A Partnership, edited by Kate Fletcher, Louise St Pierre, and Mathilda Tham, 173–178. London: Routledge.

- Mäkelä, M., and B. M. Aktaş. 2023. “Learning with the Natural Environment: How Walking with Nature Can Actively Shape Creativity and Contribute to Holistic Learning.” International Journal of Art & Design Education 42 (1): 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/jade.12447

- Omwami, A., H. Lahti, and P. Seitamaa-Hakkarainen. 2020. “The Variation of the Idea Development Process in Apparel Design: A Multiple Case Study.” International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education 13 (3): 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/17543266.2020.1817573

- Pickering, Andrew. 1993. “The Mangle of Practice: Agency and Emergence in the Sociology of Science.” American Journal of Sociology 99 (3): 559–589. https://doi.org/10.1086/230316

- Sawyer, R. Keith. 2019. “The Role of Failure in Learning How to Create.” Thinking Skills and Creativity 33: 100527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2018.08.002

- Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P. 2022. “Creative Expansion of Knowledge-Creating Learning.” Journal of the Learning Sciences 31 (1): 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2022.2029105

- Sheridan, K., X. Zhang, and A. Konopasky. 2022. “Strategic Shifts: How Studio Teachers Use Direction and Support to Build Learner Agency in the Figured World of Visual Art.” Journal of the Learning Sciences 31 (1): 14–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2021.1999817

- Yuan, X., D. Song, and R. He. 2018. “Re-Examining ‘Learning by Doing’: Implications from Learning Style Migration.” The Design Journal 21 (3): 313–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2018.1444126