Abstract

Airline food waste is a critical issue which is affected by passenger behaviour. In parallel with the unexpected advent of COVID-19, passengers have exhibited changes in eating behaviour, generating more food waste during flights. In this paper, the authors explore and reflect on the use of participatory design workshops conducted with designers and airline passengers with the aim to develop behaviour change interventions towards reducing airline food waste. This paper identifies seven types of behaviour change intervention, whilst empirically evidencing the effectiveness of participatory design in facilitating the development of behaviour change interventions, towards achieving airline food waste reduction.

Introduction

Food waste is a pressing issue and leads to environmental impacts on climate, water, land and biodiversity throughout the food supply chain. The global airline industry has paid increasing attention to food waste in recent years, particularly in the cabin service sector, due to both the food wastage itself, and the corresponding detriment to the environment. The global airline industry generated 6.1 million tonnes of cabin waste in 2018, with over 20% of that being unused food and drink (IATA Citation2020). At a global level, passengers generate an average of 1.43 kg per passenger per trip (IATA Citation2014). With the annual passenger growth rate continuing to rise, the amount of cabin waste could double over the next decades (IATA Citation2019).

Airline food waste volume is heightened due to the strict protocols for ensuring food safety and quality. For example, unconsumed meals must be treated as catering waste even if the meals were unopened (You, Bhamra, and Lilley Citation2019). Missed flights also lead to wasted airline meals, with the number of meals required relying on figures based on passenger flight bookings (Jones Citation2007). Airline food wastage has been exacerbated due to the unexpected advent of the Covid-19, threatening public health and greatly impacting the aviation industry’s operation. For example, research identified that passengers preferred to bring their own food instead of receiving the in-flight catering service due to health concerns (Samanci, Didem Atalay, and Bahar Isin Citation2021) passengers who were particularly fearful or cautious were more likely to waste food (Li, Kallas, and Rahmani Citation2022). These findings highlight how a public health crisis impacted passenger behaviour which in turn resulted in food wastage in the airline industry.

A substantial positive environmental effect can be achieved by reducing airline food waste. Previous research contribute to the transition towards a circular economy in the airline industry, suggesting airlines to replace unpopular food products that passengers rarely consume to aid the reduction of food waste (Blanca-Alcubilla et al. Citation2018). Concerns about cabin waste date back more than two decades. However, in the past few years, several airlines and stakeholders (notably catering companies) have increased their efforts to tackle this issue. Many factors such as low landfill disposal rates, particularly for inorganic fractions, lack of appropriate facilities and restrictive regulations had traditionally discouraged airlines and other actors to proactively look for solutions. Other studies suggest redesigning food menus and improving service quality to reduce in-flight catering food waste (Thamagasorn and Pharino Citation2019; Halizahari et al. Citation2021). However, these suggestions only provide solutions from the point of view of the service provider, exhibiting corporate responsibility in response to food waste issues. A holistic perspective is needed to ascertain solutions that consider the perspective of service receivers (passengers) (You, Bhamra, and Lilley Citation2020).

An association has been found between the generation of food waste and human behaviours in both household and public contexts (Quested et al. Citation2013; Stancu, Haugaard, and Lähteenmäki Citation2016). Measures for the prevention of consumer food wasting behaviour already identified include; creating policy initiatives and introducing both business and retailer solutions (Schanes, Dobernig, and Gözet Citation2018). Behaviour change interventions have been viewed as an effective way to address the problem of food waste and foster sustainable food consumption (Stöckli, Niklaus, and Dorn Citation2018). Design for Sustainable Behaviour (DfSB) is a developing area of design research and practice, situated within the broader realm of sustainable design (Wever, van Kuijk, and Boks Citation2008; Bhamra and Lilley Citation2015). Its primary focus lies in applying behavioural theory to gain insights into user behaviour and employ strategies for changing behaviour to create products, services, and systems that promote more sustainable usage (Lilley et al. Citation2017).

Participatory design is a process which transforms end users with problems into non-design experts to seek solutions drawing on their knowledge and lived experiences. In recent years, participatory design (PD) has been applied as a sustainable practice for driving socio-environmental change (Smith and Iversen Citation2018). Notably, food waste in the public context is more diverse and complex in terms of where food waste is generated, determinants of food wasting behaviour, spanning contexts such as university canteens, hotels, restaurants, and supermarkets. To gain a deeper understanding of food wasting behaviour patterns beyond household settings is essential. This understanding can pave the way for the development and selection of potential solutions to address this issue.

Through the lens of DfSB, this paper explores the utilisation of participatory design to develop and select appropriate behaviour change interventions for addressing airline food waste issues. It aims to ascertain which specific criteria should be considered when selecting appropriate behaviour change interventions to address airline food waste issues.

Literature review

Design for sustainable behaviour and design interventions

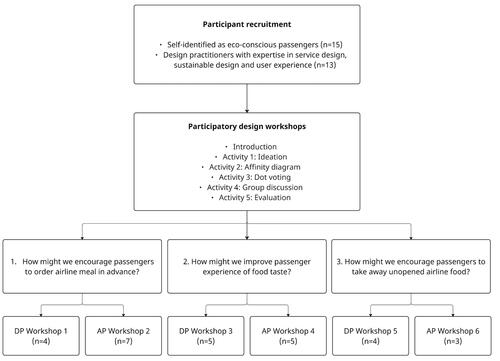

Design for Sustainable Behaviour is a transdisciplinary enquiry, which draws on behavioural theory, to explore how design can influence consumers’ activities to shape more sustainable practice. The DfSB process involves five steps, as depicted in .

Figure 1. DfSB design process (Reproduced from Lilley et al. Citation2017, 128).

Prior research by the authors identified that passenger food wasting behaviour occurred during three phases of the in-flight catering process; before the in-flight catering, during the in-flight catering and after the in-flight catering service (You, Bhamra, and Lilley Citation2020). This suggested the necessity for targeted behaviour change interventions to be deployed at each respective phase to effectively reduce food waste.

There is lack of understanding of types of behaviour change strategies and when to apply them for researchers in the field of DfSB (Boks Citation2012). Daae and Boks (Citation2014) recognise the challenge to support designers’ informed choice of the most promising behaviour change strategies to be accepted by users, emphasising understanding users in the context. However, the question of how to develop and select appropriate behaviour change interventions that can be accepted by target users, whilst having the potential to change food wasting behaviours, remains unaddressed.

The role of participatory design in tackling socio-environmental problems

Participatory design has been widely used to inform design for sustainability in many areas of design research, such as household recycling (Xiao, Luo, and Li Citation2022) and waste management (Seravalli, Upadhyaya, and Ernits Citation2022). Previous studies claimed the vital role of PD in providing awareness and facilitating the production of design solutions when addressing waste issues and enabling behavioural change. In general, it has been identified positive effects of participation-related dimensions on the environmental governance (Newig et al. Citation2023). Key stakeholders of these studies were engaged in a series of participatory design activities and contributed to the development of solutions in response to the identified problems. Despite the increased use of PD in various domains, its application in the field of DfSB to produce and select appropriate design interventions to promote behaviour change remains understudied. This paper recognises an absence of studies examining the application of PD in response to food wasting behaviour in airline services. Thus, a qualitative study was conducted by focusing on the development and selection of behaviour change interventions through a PD-based approach to further academic knowledge in the field of DfSB.

Manzini and Rizzo (Citation2011) defines participatory design as ‘a constellation of design initiatives aiming at the construction of socio-material assemblies where open and participated processes can take place’. This definition highlights participatory design as a driver and enabler of social innovation, where different actors collaborate and contribute to make a positive change. Involving stakeholders with professional design training and non-designers could facilitate the collaborative development and selection of behaviour change approaches and ensure a democratic and inclusive decision-making process (Verbeek Citation2006; Pettersen and Boks Citation2008; Wilson, Bhamra, and Lilley Citation2016). This collaboration is a key step towards facilitating design innovation for sustainability by fully utilising expertise from both groups. Users are encouraged to work autonomously on complex tasks, whilst co-designers and advisors provide guidance and support throughout the innovation process (Callens Citation2023). The designers facilitate the selection and implementation of effective behaviour change strategies with ideas taking service quality, user experience, and ethics into considerations. By involving passengers and experienced designers in the problem-solving process, outcomes can be democratically discussed and assessed by multiple stakeholders from different perspectives. This approach prevents a ‘top-down’ imposition of solutions which may restrict passengers’ choice in how to act and ensures a more democratic and inclusive process enabling appropriate strategies to be selected.

Whether participatory design approaches could offer a practical way in behaviour change intervention development and selection is understudied in the field of DfSB. Moreover, insufficient guidance on how PD can be applied to facilitate the selection and development of behaviour change and facilitate the selection of behaviour change strategies, especially in a public setting. The assumption is that the selection and development of behaviour change in the customer service context requires careful consideration on balance between user experience, quality of service and the effectiveness of appropriate behaviour change interventions. Therefore, the second question here is how PD can be applied to facilitate the development and selection of behaviour change interventions and factoring in user experiences for a business scenario.

Methodology

This research employed a participatory design approach by engaging passengers and designers in the development and selection of behaviour change interventions through design workshops.

Participants

The research was approved through Loughborough University’s ethics committee. Twenty-eight participants were recruited for the participatory design workshops through purposive sampling (Robson and McCartan Citation2016). Fifteen were self-identified as eco-conscious passengers, whilst 13 were designers with expertise in service design, sustainable design, and consumer behaviour. The inclusion criteria of ‘eco-conscious’ passengers were outlined in the participant recruitment flyer and information sheet. Participants’ eco-consciousness was determined by their voluntary sign-up for the ‘reducing airline food waste’ workshops, showing their values and motivations for engaging in pro-environmental design activities. This inclusion criterion was chosen based on research evidence stating that ‘eco-responsible’ individuals are most willing to reduce consumer food waste and bring positive influence on others (Stöckli, Niklaus, and Dorn Citation2018). Thus, passengers who identify themselves as eco-conscious are more likely to be motivated by environmentally friendly practices and can proactively provide unique insights into what will be effective in encouraging environmentally responsible behaviour amongst passengers.

Study design

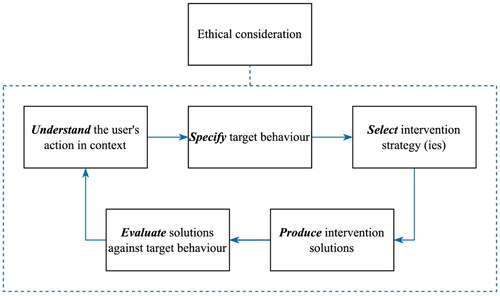

Six participatory design workshops were conducted between January and March in 2021 using online platform Miro, with three sessions involving passengers and another three sessions involving designers. Participants were coded as AP (passenger) and DP (designer) to distinguish their groups. Each workshop lasted around 1.5 h.

‘How Might We’ (HMW) questions (IDEO Citation2023) were applied to facilitate the brainstorming session in workshops. Specifically, each HMW question was associated with an in-flight food waste generation category, with each establishing the food wasting behaviour identified during pre-service, in-service and post-service phases. Each group of designers and passengers was assigned one of the three HMW questions to ensure that multiple food wasting scenarios could be discussed by the participants. Each HMW question was firstly addressed by designers in a workshop, and then by passengers in the next workshop. Three HMW questions were discussed in the six participatory design workshops. The rationale to conduct sequential design workshops for passengers and designers was (1) to avoid repetitive design ideas and (2) prevent the dominance of designers. Passengers can build upon designers’ outputs whilst producing innovative ideas aligned with their values on effective measures. Passengers might feel more comfortable explore ideas with people with shared experience without the presence of designers. This arrangement of workshop orders and participant composition allowed designers and passengers to propose ideas from their focused perspectives, considering possible solutions more comprehensively. It also enhanced non-designers’ creativity through non-intrusive empowerment. The overall study design is presented in .

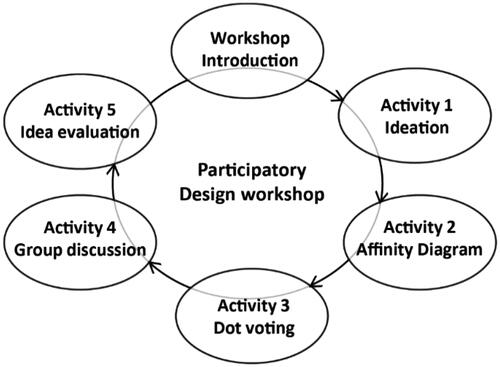

The PD process is iterative and include a series of participatory activities which can be conducted using a variety of tools and techniques. The approach emphasises the way needs, and practice can be clearly defined and comprehend by researchers, with developed solutions. presents the five activities of the PD workshops designed based on Bratteteig’s user-oriented participatory design circle (Bratteteig et al. Citation2013).

Figure 3. Activities in the ‘Reducing Airline Food Waste’ workshop (Adapted from Bratteteig et al. Citation2013).

The PD workshop started by introducing various factors associated with passenger food wasting behaviour derived from user behaviour research findings by You (You, Bhamra, and Lilley Citation2020). Then, participants were shown three case studies of existing food waste intervention strategies employed by three global full-service airlines. Next, participants worked individually to generate ideas to address the HMW question and then in groups to sort the generated ideas according to levels of influence. In activity 3, they prioritised promising ideas by voting, followed by a discussion about the prioritised ideas in activity 4. Five prompt questions were used to facilitate the group discussion of the prioritised ideas, including (1) What action should be required? (2) What is the purpose of this action? (3) What impact will this action have? (4) What expected outcomes will be? (5) Is this action (refer to the proposed design interventions) a short-term, medium-term or long-term intervention? Finally, in activity 5 each participant evaluated ideas by filling out a survey.

Data analysis

All workshops were video recorded and transcribed for data analysis. The workshops outputs, including design ideas, idea categorisation and idea prioritisation results were exported from Miro for data analysis. Thematic analysis of transcribed data (Braun and Clarke Citation2022) was conducted using NVivo 12 (Lumivero Citation2017) through open, axial and selective coding processes (Williams and Moser Citation2019).

Findings

Three key findings emerged from data analysis: user acceptance in strategy selection, prescribed behaviour change interventions for in-flight catering services and three levels of behaviour change interventions.

Overview of behaviour change interventions towards airline food waste reduction

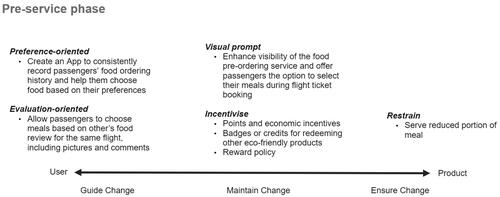

The findings established the seven types of behaviour change interventions and 15 suggested methods for changing airline food wasting behaviour. provides an overview of the levels of influence each method may exert classified into three levels as ‘Guide’, ‘Maintain’ and ‘Ensure’ (Bhamra, Lilley, and Tang Citation2011). These intervention levels range from user-dominant power in decision-making to product-oriented interventions aimed at enforcing change.

Table 1. Behaviour change intervention types, methods and levels of influence.

The results showed that ‘Guide’ and ‘Maintain’ intervention strategies are frequently mentioned to inform and maintain the behaviour change through omni-channels, such as visual, voice, and environmental prompts. For example, linking behaviour change interventions to the ticket booking process ensures passengers pre-order meals, reducing the chance of unsatisfactory onboard choices. Additionally, offering meal customisation empowers passengers to avoid purchasing unwanted items.

Finding 1: User acceptance in behaviour change intervention selection

Both groups of participants exhibited a greater inclination towards accepting ‘Maintain’ interventions aimed at altering food wasting behaviour. It was found that ‘Maintain’ behaviour change interventions provide the most promising or, in some cases, most appealing ways of changing passenger behaviour without damaging the overall customer in-flight experience. Participants generated behaviour change ideas whilst also considering ideas that enhanced the overall in-flight catering services. An improved in-flight catering experience was prioritised by many participants, which shows enhanced user experience is likely to ensure their motivation to embrace the change.

Passengers weighted ‘Guide’ intervention strategies more highly than ‘Ensure’ intervention strategies, indicating that their decision-making leaned more towards solutions which placed control with the user. ‘Ensure’ interventions were less favourable in terms of changing food wasting behaviour in the airline service. Interestingly, the research found that passengers are more receptive to coercive behaviour change interventions than designers. The majority of ‘Ensure’ interventions were proposed by passengers indicating that passengers are more accepting of this type of intervention.

AP04 stated that informing passengers to change may fail to achieve the desired behaviour as it was only an external reminder. They used an example to explain, ‘It is like an external reminder from my parents requiring me to study hard, but I cannot internalise it if my motivation to study is low’. AP04 also concerned about the interventions of ensuring behaviour changes, ‘It is too controlling, and it deprives passengers’ rights in decision-making’. Besides, AP04 chose intervention strategies for maintaining the desired behaviour because passengers can receive monetary and psychological incentives, thereby transforming the incentives into motivation for behaviour change. As they commented, ‘Passengers can be encouraged to proactively engage in airline food waste prevention. Therefore, I think ‘Maintain’ interventions will have a long-term impact on food wasting behaviour’. The results revealed that the most acceptable control level of behaviour change strategies tends to be user-in-control in this research. In other words, both designers and passengers prefer to have more power in decision-making when interacting with behaviour change interventions.

Conversely, the finding of the research identified passengers’ openness to the ‘Ensure’ interventions. AP01 said that ‘Serving small portion size of airline meal will not only reduce the costs of airlines, but also offer a healthier choice for passengers’. AP02 stated, ‘Reducing the default portion size of the meal but still allowing passengers to ask for more food if they require’. Another interesting viewpoint concerning ‘Ensure’ interventions was related to changing behaviour by adjusting the cabin environment. DP01 alluded to the notion of branding the passenger experience by building expectation and excitement. Commenting on the branded in-flight catering experience, DP01 said ‘…like walk into a COSTA or McDonald’s, it’s the same everywhere because they control the lighting, the smell and the temperature…but if you had a McDonald’s aeroplane, what would that be like?’ Passengers may treat their meals differently when the cabin lighting, smell, temperature and atmosphere are controlled to enable food consumption behaviour.

Finding 2: Prescribing behaviour change strategies in context

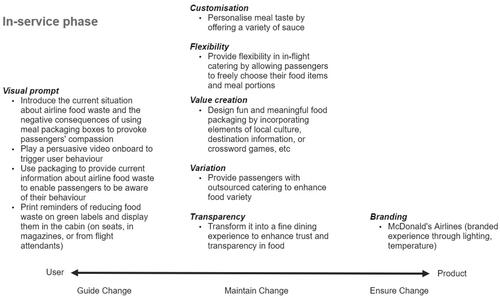

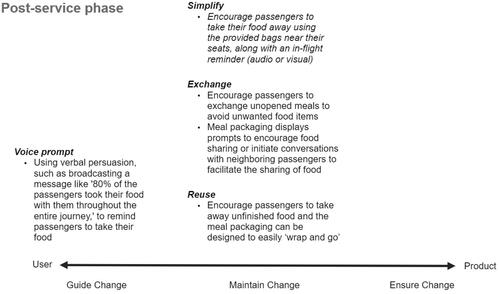

A categorisation of participant-produced ideas was established based on the voting results and discussion from the six workshops. Fifteen behaviour change ideas were reviewed and categorised into three phases of the in-flight catering service where food waste is generates. This categorisation was driven by the contextual relevance of each idea to the three phases, which ensures prescribed behaviour change interventions to target key stages of the in-flight catering service, as shown in .

Figure 4. Behaviour change interventions for the pre-service phase as suggested by participants in this study.

Figure 5. Behaviour change interventions for the in-service phase as suggested by participants in this study.

Figure 6. Behaviour change interventions for the post-service phase as suggested by participants in this study.

Behaviour change interventions for addressing food wasting behaviour during the pre-service phase exhibited all three levels of influence, primarily relying on ‘Guide’ interventions with incentives to nudge desired behaviour. The findings also indicated that providing reduced meal portions could contribute to ensuring a reduced amount of food waste.

Behaviour change interventions for addressing food wastage during in-flight catering services have focused on sustaining changes through enhanced quality of food and service. Participants believe that more sustainable food behaviours can be influenced through the perceived value of the service, making meals, dining experiences, and even food packaging more exciting and meaningful to them.

There were no coercive interventions proposed at the post-service phase. Audiovisual feedback was proposed to induce and guide the desired behaviour, with the requirement of supporting facilities, such as take-away bags, prompting designs to enable food sharing and take-away eating behaviours.

Finding 3: Three types of behaviour change interventions to reduce airline food waste

Participants in activity 5 of the PD workshops evaluated behaviour change interventions, exhibiting high awareness of the benefits of implementing such interventions to cut food waste in airlines.

The ideas prioritised ‘Guide’ interventions which mainly play a role in raising the attention of passengers using auditory or imagery as media to inform desired behaviours. This type of behaviour change strategy can activate participants’ sense of responsibility regarding their unsustainable behaviour but are less likely to secure the actual behaviour change as passengers retain the power to create changes to their behaviour or decline to change. The findings indicated that ‘Guide’ interventions require adequate attention and higher motivation from participants. Moreover, for passengers without relevant experience of the desired behaviour, the lack of knowledge and ability hinders them from changing their behaviour. Hence, providing passengers with a clear, step-by-step guide to adopting sustainable catering practices alongside ‘Guide’ interventions is essential.

Participants have recommended the use of ‘Maintain’ interventions to modify food wasting behaviour, believing that these interventions can have a lasting impact on shaping sustainable behaviour during in-flight catering services in the driving force of persuasion and incentivisation. Amongst them, 25% of participants believed that this type of intervention strategy demands specific physical abilities, relevant knowledge, and additional support or guidance to shape desired behaviours.

The ideas of ‘Ensure’ behaviour change interventions were deemed by passengers as coercive strategies. The findings indicated that passengers are more accepting of this type of intervention compared to designers. Amongst the three votes for the type of intervention, two were voted by passengers. The research findings revealed that coercive intervention would require little attention from passengers since the intended behaviour was scripted without reminding them. For instance, providing passengers with reduced portioned meals seems to be able to reduce the overall amount of food waste, but this behaviour change intervention left passengers with no choice but to passively accept what they were offered. This might affect their perception of the ‘value’ of the flight cost and meal service with which they are provided.

Discussion

This paper discusses three key dimensions, including strategy selection in DfSB using a PD-based approach, internal stakeholder engagement and implementation of behaviour change interventions.

Facilitating strategy selection through key stakeholder participation

The participatory design workshop was introduced to engage passengers and designers in the development and framing of possible behaviour change interventions. Participatory design workshops assisted strategy selection by identifying participants’ acceptance of behaviour change interventions, key stakeholders in the behaviour change process and additional features for successful implementation. This finding aligns with previous work (Degbey et al. Citation2023), which highlights that a collaborative process enables both customers and suppliers to work together towards developing responsible innovations to address environment challenges. The involvement of passengers and designers in this study has revealed potential solutions that airline companies could consider addressing the issue of in-flight catering waste.

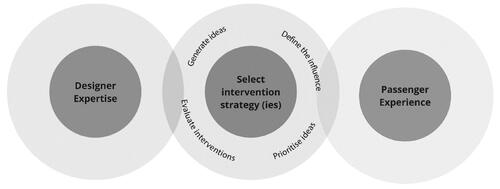

The PD workshops achieved the goal of raising awareness of the airline food waste problem, whilst enabling both parties to develop and select suitable solutions. Creative tools and techniques were introduced in reflective activities to build the inspiring experience of participation, which encouraged participants to actively reflect on the issue of passenger food wasting behaviour and the selection of appropriate behaviour change intervention strategies. Notably, prior research established the value of engaging users in the design process to uncover latent needs and generate innovative design concepts. However, these benefits were most apparent in cohesive teams where user-generated concepts were developed collaboratively (Trischler et al. Citation2017). This paper builds on this finding by providing empirical evidence for the effectiveness of involving passengers and designers in tackling the issue of airline food waste. The use of participatory design workshops extends previous findings, demonstrating how the inclusion of diverse perspectives can lead to innovative solutions for industry-specific challenges. This contribution advances the understanding of how user involvement can be leveraged in strategy selection to achieve environmental problems, like airline waste reduction. depicts the application of PD approach in the development and selection of behaviour change interventions with designers and passengers.

The development and selection of intervention strategies consist of four important steps through participatory design activities, idea generation, defining the levels of influence as in the control exerted (e.g. guide, maintain, ensure), prioritising interventions which balance potential effectiveness in addressing the problematic behaviour and meeting (or exceeding) users’ expectations of experience and evaluation. The consumption phase contributes significantly to the total environmental impact of the in-flight catering service. This impact is largely influenced by passengers’ behaviour. It is suggested designers influence this behaviour in a more sustainable direction based on a user-centred approach (Wever, van Kuijk, and Boks Citation2008). Hence, integrating PD in the DfSB process has inspire passengers to build upon professional designers’ work to provide comprehensive ideas to drive changes, leveraging their expertise and personal experience. Designers apply their expertise in and knowledge of sustainable design, service design and user experience. They found design solutions that ensure a balance between service quality and desired behaviour change. This was evidenced by their preference for interventions that prioritise potential effectiveness in addressing problematic behaviour whilst meeting passengers’ expectations of in-flight experience, rather than adopting coercive interventions. Passengers’ experience of in-flight catering service and their motivation to engage themselves in reducing food waste were found to be associated with the exploration of acceptable behaviour change interventions. Passengers proposed behaviour design interventions that better suit their own situations and are more acceptable to them on top of those ideas that have already been generated by designers. Through their perspective, it can be defined which type of interventions could enhance their motivation to change.

This process reduces conflicts arising from the distinct stances of both parties, ensuring the possibility of mutual learning, whilst enabling effective behaviour change intervention selection. When designing sustainable behaviour within public settings, the role of PD in the selection of behaviour change interventions is as a mediator to find a sweet spot between reducing unsustainable practice and maintaining an effective service operation.

Internal stakeholder engagement in a DfSB process

Due to the complexity of the current airline catering system, an evaluation involving internal stakeholders from the industry is still required to gain professional insights into the feasibility of implementation. The design workshops helped identify relevant roles of internal stakeholders. For example, in activity 4, flight attendants were mentioned to assess the feasibility of proposed behaviour change interventions, as AP12 stated:

Many passengers did not know about the pressing issue of airline food waste, but the flight attendants who serve the meals and collect the food waste knew the situation. If they could inform passengers about this issue, passengers would have known the negative consequences of their actions

Recommendations for the implementation of behaviour change interventions

This paper recommends using ‘Maintain’ interventions as appropriate solutions for changing passenger food wasting behaviour and potentially leading to airline food waste reduction. This finding resonates with people’s inclination to change if design interventions are considered acceptable for their respective comfort levels (Boks and Daae Citation2017). Motivation can be observed through participants’ emotions, revealing their goals and values during the interaction (Desmet et al. Citation2023). Participants in this study presented a greater motivation to shift to desired behaviours, whilst maintaining a level of autonomy in decision-making of how to switch to a more sustainable practice. This paper highlights a customer perspective to drive radical changes to prevent waste rather than simply follow traditional protocol of handling airline waste only by airline service providers. The findings of this paper advocates using PD to select and development behaviour change interventions that prioritise waste prevention under an economy that is circular by design.

The forms of coercive interventions to change behaviours were found receive insufficient attention because they are difficult to be put in practice and resulting in a gap in the research relating to pro-environmental behaviour studies (Staddon et al. Citation2016). To fill this gap, this paper reveals opportunities for design interventions with more coercive control. Some of passengers were found to advocate for coercive interventions. The possible explanation for this finding is that introducing coercive interventions can ensure desired behaviour changes which align with the values of eco-conscious passengers. They may view these types of interventions as necessary steps to protect the environment, making them more likely to accept such interventions. The participants of this study might be pre-disposed by their eco-conscious values to accept increased control. Further investigation would need to examine whether passengers lacking eco-consciousness or pro-environmental beliefs would be receptive to coercive interventions and how coercive behaviour change interventions can effectively reduce food waste without negatively impacting passengers’ in-flight catering experience.

Previously, social norms have been seen as an effective intervention type to change consumer food wasting behaviour at home (Stöckli, Niklaus, and Dorn Citation2018). The current findings uncovered the significance of social norms in designing for ‘Guide’ and ‘Maintain’ interventions, and to inducing food sharing and taking-away behaviour in a public setting.

Nevertheless, the implementation of design interventions is not without challenge. An earlier study found a correlation between the low quality of in-flight catering service and food, influences passenger experience and results in increased food waste (Halizahari et al. Citation2021). The need to ‘strike a balance’, or in other words, navigate a trade-off between achieving effective change and maintaining a positive service experience is acknowledged as a key challenge. Similarly, previous work acknowledges that positive emotions can influence individual decisions and actions, potentially inducing more sustainable behaviour change (Brosch Citation2021). This aligns with our findings, suggesting that maintaining a positive service experience whilst implementing behaviour change interventions is crucial for their effectiveness. The selection and implementation of behaviour change interventions for addressing airline food waste, especially in the service sector, need to be managed carefully in practice. For instance, environmental and economic trade-offs are commonplace in organisational decision-making. Hence, it will be necessary to engage key decision-makers within airline catering services to evaluate the viability further and refine the behaviour change intervention plan. They will play a crucial role in evaluating and helping implement design interventions, allowing for the anticipation and prevention of unintended and harmful impacts on customers and services and the compliance with airline regulations. Moreover, airlines should assess their commitment to sustainability values and determine the degree to which they will prioritise initiatives, even if these choices might negatively impact their financial performance and corporate image.

Conclusions and future work

The issue of airline food waste requires urgent attention on the selection of behaviour change interventions to shaping sustainable behaviour amongst passengers. Returning to the questions posed at the beginning of the paper, this paper has argued that user acceptance should be considered when selecting appropriate behaviour change interventions and contributed to:

The provision of empirical evidence highlighting the advantages of applying participatory design to the development and selection of behaviour change interventions in the context of preventing or reducing airline food waste.

An exploration into the potential of design-led solutions to reduce food waste by changing airline passenger behaviour.

Enhanced knowledge and understanding about the selection of appropriate behaviour change interventions through the identification of user acceptance as a decisive factor.

By designing sequential design workshops and separating participants into two groups, passengers can be empowered in the ideation and decision-making processes without being dominated by professional designers. Designers were also able to select effective behaviour change interventions whilst considering the balance between user satisfaction and desired behaviour change. This finding, with empirical evidence on how user acceptance can be identified and considered as a criterion in behaviour change interventions using a PD design process, provides new knowledge for strategy selection in the field of DfSB.

The generalisability of these findings is subject to certain limitations. The pre-set values of recruited passengers could show different acceptance towards behaviour change interventions compared with those passengers with less eco-consciousness. Future research could benefit from a larger sample size to enable generalised research findings.

Another notable strength of this paper is the documentation of a validated participatory design process and seven types of behaviour change interventions. The paper provides evidence through an empirical study for the future service design and development of the airline industry and other public sectors to reduce food waste from the catering service.

PD design workshops focussed on solutions for reducing airline food waste are being undertaken in which behaviour change interventions acceptable for passengers identified. Stakeholder involvement is a vital step towards the development and selection of behaviour change intervention strategies. This paper, through the lens of DfSB, revealed that a participatory design process for finding solutions aids decision-making in strategy selection and behaviour change intervention development. It should be noted that the implementation of these types of behaviour change interventions requires a comprehensive assessment by professional stakeholders from airline companies. Future studies should involve the stakeholder assessment of proposed design solutions, considering practicability, effectiveness and possible consequences of their implementation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants for providing their time and valuable insights in the workshops.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Fangzhou You

Fangzhou You is a Lecturer in Digital Design at School of Arts and Creative Technologies, University of York. Her research centres on responsible design, design for sustainable behaviour and design for behaviour change. She explores methods and strategies for developing design-led solutions to change problematic behaviour and promote sustainable consumption.

Tracy Bhamra

Tracy Bhamra is a Professor of Design for Sustainability, the Provost and Pro Vice-Chancellor (Global) at Royal Holloway, University of London. Her research interests include methods and tools for sustainable design, sustainable product service systems, and sustainable design strategy.

Debra Lilley

Debra Lilley is a Senior Lecturer in Design within the School of Design and Creative Arts, Loughborough University. Debra’s research focuses on the intersection of material change and behaviour change within the context of sustainable design and the circular economy.

Nikki Clark

Nikki Clark is a Lecturer in Design at School of Design and Creative Arts, Loughborough University. Nikki has a track record of research on consumer behaviour with packaging when designing for circular systems. Nikki is currently undertaking research into improving the experience of reusable packaging systems, to ensure social, environmental and economic value.

References

- Bhamra, Tracy, and Debra Lilley. 2015. “IJSE Special Issue: Design for Sustainable Behaviour.” International Journal of Sustainable Engineering 8 (3): 146–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/19397038.2015.1026666.

- Bhamra, Tracy, Debra Lilley, and Tang Tang. 2011. “Design for Sustainable Behaviour: Using Products to Change Consumer Behaviour.” The Design Journal 14 (4): 427–445. https://doi.org/10.2752/175630611X13091688930453.

- Blanca-Alcubilla, Gonzalo, Alba Bala, Juan Ignacio Hermira, Nieves De-Castro, Rosa Chavarri, Rubén Perales, Iván Barredo, and Pere Fullana-I-Palmer. 2018. “TACKLING INTERNATIONAL AIRLINE CATERING WASTE MANAGEMENT: LIFE ZERO CABIN WASTE PROJECT. STATE OF THE ART AND FIRST STEPS.” Detritus 3 (1): 159–166. https://doi.org/10.31025/2611-4135/2018.13698.

- Boks, Casper. 2012. “Design for Sustainable Behaviour Research Challenges.” In Design for Innovative Value Towards a Sustainable Society, 328–333. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-3010-6_64.

- Boks, Casper, and Johannes Zachrisson Daae. 2017. “Design for Sustainable Use: Using Principles of Behaviour Change.” In Routledge Handbook of Sustainable Product Design, 316–334. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315693309.

- Bratteteig, Tone, Keld Bødker, Yvonne Dittrich, Preben Holst Mogensen, and Jesper Simonsen. 2013. “Methods: Organising Principles and General Guidelines for Participatory Design Projects.” In Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design, 1st ed., 117–144. London, UK:Routledge.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2022. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. 1st ed. London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Brosch, Tobias. 2021. “Affect and Emotions as Drivers of Climate Change Perception and Action: A Review.” Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 42 (December): 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.02.001.

- Callens, Chesney. 2023. “User Involvement as a Catalyst for Collaborative Public Service Innovation.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 33 (2): 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muac030.

- Daae, Johannes Zachrisson, and Casper Boks. 2014. “Dimensions of Behaviour Change.” Journal of Design Research 12 (3): 145–172. https://doi.org/10.1504/JDR.2014.064229.

- Degbey, William Y., Elina Pelto, Christina Öberg, and Abraham Carmeli. 2023. “Customers Driving a Firm’s Responsible Innovation Response for Grand Challenges: A Co-active Issue-Selling Perspective.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 41 (2): 379–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12705.

- Desmet, Pieter M. A., Haian Xue, Xin Xin, and Wei Liu. 2023. “Demystifying Emotion for Designers: A Five-Day Course Based on Seven Fundamental Principles.” Advanced Design Research 1 (1): 50–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijadr.2023.06.002.

- Halizahari, M., Mohd Hamran Mohamad, Wan Anis, and Aqilah Wan. 2021. “A Study on in-Flight Catering Impacts on Food Waste.” Solid State Technology 64 (2): 4656–4667.

- IDEO 2023. “How Might We.” Design Kit. https://www.designkit.org/methods/how-might-we.html.

- IATA (International Air Transport Association). 2014. “Airlines Financial Health Monitor”. IATA Economics, May. https://www.iata.org/whatwedo/Documents/economics/airlines-financial-monitor-apr-14.pdf www.iata.org/economics.

- IATA (International Air Transport Association). 2019. “Cabin Waste Fact Sheet.” https://www.iata.org/pressroom/facts_figures/fact_sheets/Documents/fact-sheet-cabin-waste.pdf.

- IATA (International Air Transport Association). 2020. Economic Performance of the Airline Industry. International Air Transport Association.

- Jelsma, Jaap, and Marjolijn Knot. 2002. “Designing Environmentally Efficient Services; a ‘Script’ Approach.” The Journal of Sustainable Product Design 2 (3/4): 119–130. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JSPD.0000031031.20974.1b.

- Jones, Peter. 2007. “Flight Catering.” In Catering-Management Portrait Einer Wachstumsbranche in Theorie Und Praxis, edited by John S. A. Edwards, 2nd ed., 39–55. Hamburg: Behr’sVerlag. https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/9780750662161/flight-catering.

- Li, Shanshan, Zein Kallas, and Djamel Rahmani. 2022. “Did the COVID-19 Lockdown Affect Consumers’ Sustainable Behaviour in Food Purchasing and Consumption in China?” Food Control 132 (February): 108352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.108352.

- Lilley, Debra, Garrath Wilson, Tracy Bhamra, Marcus Hanratty, and Tang Tang. 2017. “Design Interventions for Sustainable Behaviour.” In Design for Behaviour Change, 40–57. London, UK: Routledge.

- Lumivero 2017. “NVivo 12.” www.lumivero.com.

- Manzini, Ezio, and Francesca Rizzo. 2011. “Small Projects/Large Changes: Participatory Design as an Open Participated Process.” CoDesign 7 (3–4): 199–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2011.630472.

- Newig, Jens, Nicolas W. Jager, Edward Challies, and Elisa Kochskämper. 2023. “Does Stakeholder Participation Improve Environmental Governance? Evidence from a Meta-Analysis of 305 Case Studies.” Global Environmental Change: Human and Policy Dimensions 82 (September): 102705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2023.102705.

- Niedderer, K., G. Ludden, S. J. Clune, D. Lockton, J. Mackrill, A. Morris, R. Cain, et al. 2016. “Design for Behaviour Change as a Driver for Sustainable Innovation: Challenges and Opportunities for Implementation in the Private and Public Sectors.” International Journal of Design 10 (2): 67–85.

- Pettersen, Ida Nilstad, and Casper Boks. 2008. “The Ethics in Balancing Control and Freedom When Engineering Solutions for Sustainable Behaviour.” International Journal of Sustainable Engineering 1 (4): 287–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/19397030802559607.

- Quested, T. E., E. Marsh, D. Stunell, and A. D. Parry. 2013. “Spaghetti Soup: The Complex World of Food Waste Behaviours.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 79 (October): 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2013.04.011.

- Robson, Colin, and Kieran McCartan. 2016. Real World Research: A Resource for Users of Social Research Methods in Applied Settings. Wiley

- Samanci, Simge, Kumru Didem Atalay, and Feride Bahar Isin. 2021. “Focusing on the Big Picture While Observing the Concerns of Both Managers and Passengers in the Post-Covid Era.” Journal of Air Transport Management 90 (October 2020): 101970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101970.

- Schanes, Karin, Karin Dobernig, and Burcu Gözet. 2018. “Food Waste Matters - A Systematic Review of Household Food Waste Practices and Their Policy Implications.” Journal of Cleaner Production 182 (May): 978–991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.030.

- Seravalli, Anna, Savita Upadhyaya, and Heiti Ernits. 2022. “Design in the Public Sector: Nurturing Reflexivity and Learning.” The Design Journal 25 (2): 225–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2022.2042100.

- Smith, Rachel Charlotte, and Ole Sejer Iversen. 2018. “Participatory Design for Sustainable Social Change.” Design Studies 59 (vember): 9–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2018.05.005.

- Staddon, Sam C., Chandrika Cycil, Murray Goulden, Caroline Leygue, and Alexa Spence. 2016. “Intervening to Change Behaviour and save Energy in the Workplace: A Systematic Review of Available Evidence.” Energy Research & Social Science 17 (July): 30–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2016.03.027.

- Stancu, Violeta, Pernille Haugaard, and Liisa Lähteenmäki. 2016. “Determinants of Consumer Food Waste Behaviour: Two Routes to Food Waste.” Appetite 96 (January): 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.08.025.

- Stöckli, Sabrina, Eva Niklaus, and Michael Dorn. 2018. “Call for Testing Interventions to Prevent Consumer Food Waste.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 136: 445–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.03.029.

- Thamagasorn, Metawe, and Chanathip Pharino. 2019. “An Analysis of Food Waste from a Flight Catering Business for Sustainable Food Waste Management: A Case Study of Halal Food Production Process.” Journal of Cleaner Production 228 (August): 845–855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.312.

- Trischler, Jakob, Simon J. Pervan, Stephen J. Kelly, and Don R. Scott. 2017. “The Value of Codesign: The Effect of Customer Involvement in Service Design Teams.” Journal of Service Research 21 (1): 75–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670517714060.

- Verbeek, Peter-Paul. 2006. “Materializing Morality.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 31 (3): 361–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243905285847.

- Wever, Renee, Jasper van Kuijk, and Casper Boks. 2008. “User‐Centred Design for Sustainable Behaviour.” International Journal of Sustainable Engineering 1 (1): 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/19397030802166205.

- Williams, Michael, and Tami Moser. 2019. “The Art of Coding and Thematic Exploration in Qualitative Research.” International Management Review 15 (1): 45–55.

- Wilson, Garrath T., Tracy Bhamra, and Debra Lilley. 2016. “Evaluating Feedback Interventions: A Design for Sustainable Behaviour Case Study.” International Journal of Design 10 (2): 87–99.

- Xiao, Jia Xin, Ming Jun Luo, and Wenhua Li. 2022. “From the Fuzzy Front End to the Back End: A Participatory Action Research Approach to Co-Design Promoting Sustainable Behaviour.” The Design Journal 26 (1): 32–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2022.2113262.

- You, Fangzhou, Tracy Bhamra, and Debra Lilley. 2019. “Design for the Passengers’ Sustainable Behaviour in a Scenario of the in-Flight Catering Service.” Proceedings of the Design Society: International Conference on Engineering Design 1: 3231–3240. https://doi.org/10.1017/dsi.2019.330.

- You, Fangzhou, Tracy Bhamra, and Debra Lilley. 2020. “Why is Airline Food Always Dreadful? Analysis of Factors Influencing Passengers’ Food Wasting Behaviour.” Sustainability 12 (20): 8571. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208571.