ABSTRACT

This paper is centred on exploring how young people from Sikh and Hindu backgrounds, who are British born and living in the London area understand Britishness. By utilising transcripted interviews from eighty respondents, this research uncovers and presents the core perceptions and understandings that these young people have about British national identity and the ways in which it is accommodated (or not) alongside other important sources of belonging in their lives. This paper presents the diverse ways in which these young people understand Britishness. In particular, ‘thick' and ‘thin’ conceptualisations of Britishness and the role of family structures in shaping belonging are examined. It is suggested that any discussion of how ethnic minorities relate to national identity requires a better understanding of the diverse ways in which this form of identity is understood and accommodated. This, in turn, will encourage a more inclusive and productive debate on the role of national identity in multi-cultural Britain. This is particularly salient in a post-Brexit Britain where the themes of nationality and belonging have been brought into the socio-political fore once more, and newer immigrants are facing the challenges of feeling included and becoming British.

1. Introduction

In recent years, when tensions have arisen and boiled over between different ethnic groups, multiculturalism’s failure to bind people together has been viewed as the cause. The solution thus far on a policy level has been to promote a ‘new Britishness’ focusing on commonality and togetherness, which will bind people together in the face of new challenges and pressures (Cantle, Citation2012; Kalra & Kapoor, Citation2008; Kundnani, Citation2007; Pilkington, Citation2008; Platt, Citation2014; Worley, Citation2005). The perception has been that social fragmentation and unrest has been caused by people living separate lives, which has led to the assumption that if there were a clearer sense on citizenship, and commitment to ‘British Values’ this will be the much needed ‘glue’ necessary to hold together a fragmented society. As a result, throughout Europe, governments have attempted to crystallise what it means to have a sense of national identity as an instrument to better integrate members of ethnic minorities (Barry, Citation2001; Bingham, Citation2012; Heath & Demireva, Citation2013; Joppke, Citation2004; Palmer, Citation2012; Pilkington, Citation2008; Platt, Citation2014; Vasta, Citation2007; Wright & Taylor, Citation2011).

The proposed alternatives to multicultural policies have thus been focused on cohesion, shared values, citizenship and national identity (Cantle, Citation2012; Casey, Citation2015; Kalra & Kapoor, Citation2008; Kundnani, Citation2007; Pilkington, Citation2008; Platt, Citation2014; Worley, Citation2005). Contrastingly, academics researching the extent to which members of ethnic monitories feel a sense of Britishness, or more generally have a positive feeling of belonging to Britain have found overwhelmingly that these groups do feel ‘British’, that they do have a sense of ‘Britishness’ and that they have positive orientations towards British culture, institutions and the local and national community (Güveli & Platt, Citation2011; Manning & Roy, Citation2010; Platt, Citation2013b; Platt, Citation2014).

The continued debate about a loss of British culture implies that despite the positive findings of empirical research, there still remains a high level of scepticism over the extent to which members of ethnic minorities are culturally integrated (Bhambra, Citation2015). There has been a focus on the perceived identity dilemmas of British Muslims, Pakistani and Bangladeshi in particular, with less focus on what is happening in other groups (Ibid.) This concern continues despite many reports highlighting that British Muslims have a strong sense of belonging and positive orientations towards Britishness even compared to the white majority (Platt, Citation2014). As Alba and Foner have recently noted, ‘Despite British Muslims’ strong identification with their country and pride in being British, public discourse about Muslims’ identity often takes a different tack. Fears about Muslims’ loyalty […] are widespread, and leading journalists and politicians often portray Muslims as having difficulty feeling British’ (Alba & Foner, Citation2015, p. 203).

These issues continue to be salient in a post-Brexit environment where there is on-going debate and focus on immigration, nationality and belonging. Brexit has highlighted social divides, often about who belongs and who does not (Bhambra, Citation2016a, Citation2016b; Dorling et al., Citation2016; Ford & Sobolewska, Citation2018). It has also conveyed deep-seated beliefs about who deserves to be part of British society and who does not (Ford & Sobolewska, Citation2018). It has for many, been an opportunity to try and re-establish a sense of Britishness, of trying to make clear statement about who is British and who is not, as exemplified by the Leave campaigns now infamous ‘we want our country back!’ slogan. It has been a pivotal movement where boundaries internally and externally have been interrogated, and for many, re-established to include ‘us’ and ‘them’; ‘us’ the British people and the ‘others’ within our society, and ‘us’ as a separate and more independent nation. Thus, it has reignited the debate on Britishness, what it means and whom it represents and encompasses.

2. Background

Shared National identification is widely regarded in the literature as an important indicator for levels of social cohesion and the incorporation, or alienation, of minorities (Platt, Citation2014, p. 1). There are broadly speaking two sides of the argument: On the one hand, there has been a celebration of the way a multiculturalist society is able to accommodate diverse people with different cultural and religious backgrounds within a common framework (Modood, Citation2007; Platt, Citation2014, p. 1; Parekh, Citation2000a). Contrastingly, there has been a growing concern about the extent to which members of ethnic minorities are seen to be following ‘parallel lives’ that carry with them the potential exclusiveness of strong minority ethnic and religious identities, coupled with little sense of belonging to the nation as a whole (Cameron Citation201l; Heath & Demireva, Citation2013; Huntington, Citation1993; Phillips, Citation2005).

Heath and Demireva argue that, ‘more sociologically, the hypothesis is that MCPsFootnote1 promote “bonding” rather than “bridging” social capital’ (Heath & Demireva, Citation2013, p. 162). In the practical sense for ethnic minorities in Britain, it is the essentialist assumption that having a strong ethnic and/or religious identity is a hindrance to having strong relations with the majority culture and people; a lack of bridging which can lead to separatism. (Barry, Citation2001; Bingham, Citation2012; Heath & Demireva, Citation2013; Heath & Spreckelsen, Citation2014; Joppke, Citation2004; Palmer, Citation2012; Platt, Citation2014; Wright & Taylor, Citation2011). The critics of multiculturalism in recent years have used this argument repeatedly: that there are separate communities in Britain whereby people live separate lives away from the mainstream culture (Joppke, Citation2004; Pilkington, Citation2008; Vasta, Citation2007).

This separation thesis, based on a concern over integration, has evolved from the idea that multiculturalism, or more specifically, that multicultural policies in Britain, have negatively impacted the sense of commonality, and common culture; these concerns about multiculturalism have also raised concerns about perceived ‘clashing values’ between minority and majority groups.

The assumption is that members of ethnic minorities are strongly bound together within their distinct communities, and that there may be a tension between the values of these communities and those of the majority, which has led to a lack of integration (Barry, Citation2001; Bingham, Citation2012; Heath & Demireva, Citation2013; Heath & Spreckelsen, Citation2014; Joppke, Citation2004; Palmer, Citation2012; Platt, Citation2014; Wright & Taylor, Citation2011). There is also a perception of competing loyalties (Heath & Demireva, Citation2013). As Jaspal and Cinnirella note ‘These discussions frequently anchor the issue of Britishness to national loyalty and implicitly or explicitly highlight some form of necessary rivalry between British national and ethnic/religious identities’ (Jaspal & Cinnirella, Citation2013, p. 157)

Other sources of identity can thus be seen as a barrier to being British. This poses several dilemmas. First, the essentialist nature of the claim must be called into question; how much do we actually know about the way that members of minority groups feel about other sources of belonging, are they as engrossed in a separate minority culture as the critics would claim? Secondly, the literature on, and our knowledge of, social identities highlights the malleability and multiplicity of identities, people can, and do, have more than one identity, it is not an ‘either or’ scenario; to have a strong ethnic or religious identity does not necessarily equate into a lack of Britishness (Berry, Citation1997; Platt, Citation2014; Verkuyten & Zaremba, Citation2005). Also, ‘contradictions between these identities are often emphasised, while commonalities and points of connection are rarely acknowledged’ (Jaspal & Cinnirella, Citation2013, p. 157)

There has thus been much debate and academic research on British national identification.Footnote2 However, the issue of data on the real experience of identity still remains. We simply do not have enough information about the identity patterns of ethnic minority members to make sweeping generalisations about their identification, or lack of identification with Britishness . ‘Despite the common academic belief in national identity as central to cohesion, a social glue that binds individuals together the evidence relating to minority immigrant identification is not extensive’ (Platt, Citation2014, p. 4).

British Hindus and Sikhs have long been seen as model minorities, well-integrated and unlikely to cause problems yet, are under-represented in the literature (Bhambra, Citation2015). Certainly first, second and third generation can be seen to have successfully integrated into British society if we use the thinner measures of educational attainment, and access to higher paid jobs.

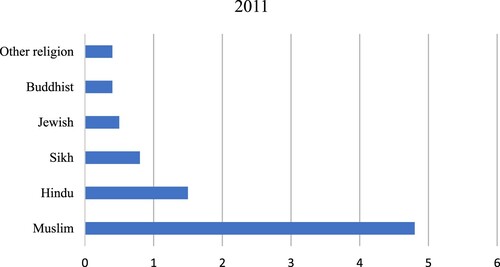

These communities thus become interesting because they has been so successful. More specifically, this group is not compounded by issues of Islamophobia and economic disadvantage, yet still has high levels of community involvement and organisation (Bhambra, Citation2015). Additionally, Sikhs and Hindus form the second two largest minority groups in England and Wales after Muslims (see ).Footnote3 Thus, the size of these communities and their contribution to the fabric of social life warrants a closer investigation into how young people from these groups are experiencing their Britishness; the opportunities and challenges it entails for them. This dialogue is vital to maintain and promote social cohesion, and facilitate conversations with these communities.

This paper will thus focus on the Sikh and Hindu community in London, it’s young people as a ‘test case’ to uncover how these issues of competing loyalties and Britishness may apply to these individuals. The rationale for focusing on these groups is to provide detailed insight into the way that young Sikhs and Hindus experience their own identities, to provide analysis from a large data set of interviews and to present themes that cut across both religious groups so that they can be more generalisable in the continuing scholarly interest in Britishness and minority groups.

3. Methodology

3.1. Biographical insights

As with much research, the choice of this topic reflects my own personal experiences and interests. As a second-generation British Indian, living in multicultural London, learning about what it means to be ‘Indian’, ‘Sikh’ and also ‘British’ has marked my own life. Being a ‘British-Indian’ is more than ticking a box on a job application. For me, it has been, and continues to be a lifelong journey of accommodating two cultures that form the core part of my identity, albeit in different ways. As a researcher, I have been committed to uncovering this journey for other young people and discovering the different ways that we have all accommodated these cultures (or not), the factors which have impacted this, and discovering how living in multicultural London has shaped our ideas about what it means to be British and our own Britishness (Baumann, Citation1996; Bhambra, Citation2015; Jandu, Citation2015; Sian, Citation2013). My role as a researcher is to use my ability to gain insight into minority cultures to facilitate meaningful conversations, which in my experience has been aided immensely by my own minority status.

For this research, I initially undertook eighty in-depth interviews in order to speak to a wide range of second generation young people between the ages of 18–25 (mean age – 22); the sample included male and female second-generation British-Sikhs and British-Hindus, from a range of backgrounds.Footnote4These were then followed up with a further 60 follow-up interviews over the next two years with a smaller sample of the respondents.Footnote5 The decision to focus on London was practical in the sense of most of these young people being based in the city, but also deliberate in that it allows for investigation into how these issues play out in a multicultural setting. Often London’s diversity is equated with a sense of belonging for all Londoners, but I found that there are still some challenges in a diverse, liberal setting such as London.

Given my aims for this research, I decided that I would conduct a criterion-based sampling approach aided by utilising my own networks of family and friends, my contacts at London community centers for British-Indian youths, and my contacts at London-based Gurdwaras and Mandirs. I then used a snowball-sampling approach to gain more participants via these networks. These methods combined allowed me to gain access to young people whom I needed to speak to in order to make sure that my sample was as diverse as possible. I used my own acquaintances to contact young Sikhs from a range of backgrounds, as well as utilising my contacts at a London-based drop-in community center for young British-Indians. The initial contacts I made were made mindful of the fact that people needed to come from a diverse range of backgrounds. I was thus able to conduct in-depth interviews with a wide range of young people who gave me a detailed insight into how they experience and understand Britishness. Most importantly, I was able to explore the diversity in experience in order to convey the range of ways that these young people respond to the challenges of being Sikh, Hindu and also British.

3.2. Research duration and stance

This research was began in 2012 when I started to get to know each of the respondents. This forming of relationships was crucial to being able to ask these young people about identity and their own experiences, which were often quite painful to recall especially for those who had encountered significant racial abuse. Being from a similar background was crucial in being able to uncover such experiences over a long period of time. Mutual exchanges were instrumental creating an open environment and breaking down the traditional interviewer-interviewee dynamic whereby personal reflections could be offered more easily; my research stance was thus participatory and empathic.

3.3. Analytical method

I employed a grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1994) approach to this research as I wanted to allow themes to emerge from the data, which would inform theory rather than imposing a strict theoretical framework on the data. Interviews were arranged after obtaining consent from each participant and they all followed a semi-structured format using an interview guide. This type of interview allowed me to combine structure with flexibility (Gaskell, Citation2000; Legard et al., Citation2003, p. 141). After each interview, I spent time writing a report summarising the key findings and emergent themes. The audio recordings of the interview were transcribed and then the transcripted data was uploaded using the NVivo software (Miall, Citation1990; Silverman, Citation2010). The data was then analysed using qualitative thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). Thematic analysis allowed me to look for emergent patterns in the data, this was made more efficient by using NVivo where I could safely store the large data corpus, and store the demographic details of the respondents to look for patterns.

4. Results

I found that there are many subtle shades of meaning surrounding British identity and great diversity in the way that young Sikh and Hindus express their relationship with the notion of Britishness. Ideas about what British identity constituted and meant were mostly formulated on the life experiences of the individual, contact experiences with white British people, their own level of involvement and attachment in their own ethnic communities, and where they felt they could fit in during their day-to-day lives – within British society, in their own ethnic communities, or in a combination of the two. The most common emergent themes across both Sikhs and Hindu groups after the thematic analysis was completed are presented here.

4.1. There is no Britishness without distinct culture

Some of the young respondents understood and experienced ‘British identity’ in direct comparison with the experienced cultural richness and ‘togetherness’ of their own ‘group’. It was unsurprising, then, that those respondents who felt this way most strongly were also the same young people whose experiences of being a ‘Sikh’, being a ‘Hindu’, or simply being ‘Indian’ were not only positive and inclusive, but also provided them with a strong sense of belonging and community.

British identity was thus often considered an ‘empty’ notion for these young Sikhs and Hindus as it was seen as being devoid of the rich cultural attributes that constitute an ‘identity’ as such; distinctive food, music, religious days, language and community. The latter was drawn on heavily by respondents who defined the notion of ‘identity’ interchangeably with having a sense of culture; unique traditions and a distinctive community who upheld these traditions. To them, you could not have a sense of identity without a strong sense of community. Britain was seen as being fragmented and insular, in comparison with their own ethnic/religious community, which was experienced as having a strong sense of togetherness, loyalty and mutual respect.

I would say that there isn’t a British identity, if you look at people that live in Spain, or Italy and France, well they have their own culture, they like their healthy living and their wine, but there isn’t anything like that here, there isn’t a culture, there isn’t any pride, it’s all really mixed up […] I don’t think you can have a British identity when there isn’t a British culture. People have to be together for there to be an identity, like how we are Sikh brothers we have that issat (respect). We are together, there is nothing like special about them […] they haven’t got a culture. If you haven’t got a culture then you can’t have like a British identity ‘cos there is nothing to celebrate; it’s all like bland. People are all separate; no one talks to each other. We can depend on our community if we need something, the goras (white British people), they have no community, they haven’t got a culture like we have.

Ranbir 22, Sikh Male, Accountant.

As Ranbir described, the meanings attached to British identity were thus often formulated in direct contrast with other culturally rich, distinctive and more meaningful identities. Additionally, the idea of a sense of togetherness, of camaraderie and that feeling of support from a community was intrinsic for many of the young people I interviewed. These comparisons between social groups lead to felt sense of separation form the British majority based on having a ‘real’ culture as opposed to a group that was ‘without culture’ (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1986).

For many of these young people British identity did not exist, not only because there was nothing special, or culturally rich in Britishness or British life itself, but also because British people, meaning white people specifically, were fragmented; they had no sense of ‘community’ and ‘brotherhood’. These ideas were formulated in direct comparison with the feelings of security and warmth provided by their ethnic community. British identity was thus void. As one respondent asked me, ‘how can you have a sense of identity when the people don’t have nothing to do with each other, they are all split up?’ To have identity was for them, to have a sense togetherness and community.

There is no glue, there is nothing to hold British people together, there is, no culture, no bonds with each other. There is nothing distinctive about them.

Tejas 19, Gujerati Male, University Student.

Tejas and other Hindus and Sikhs I interviewed, described life in Britain and London as a myriad of cultures, a place where many people lived in their own cultural groups, where people interacted with each other in the workplace, at university or in day-to-day life, but then retreated to their own cultural group, their own segment of the population. Being British was described as superficial involvement; being part of the workforce, being part of a university, but then going home to what was seen as the ‘real culture’, the real source of belonging – family, traditions, Indian food, culture and unity.

4.2. The legacy of empire

National events, national symbols, and the historical and current policies of the British Government had strong implications for the acceptance of British identity as a source of belonging in some of these young people’s lives.

For some young people, the meanings they attached to British identity were not shaped so much by the lack of culture and traits, but instead were more about the negative traits of the country’s current and historical foreign policy. During the interviews, these young people did not focus on what British identity lacked, or how it compared unfavourably with other more ‘culturally rich’ identities, but instead focused on the actions of the country’s leaders and Britain’s role in geo-political events such as wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. For them there was a ‘British identity’ and it was largely determined by British domestic and foreign policy, and the way that this political behaviour impacted others around the world.

I think it is hard for us Indians that are born in England, ‘cos we can’t forget what has gone on in the past, if you know what I mean. Our loyalties are always going to be India, but like we can say we have ‘British identity’ like what you are asking me ‘cos British identity is like being proud of the culture of Britain, the culture of like ruling other countries, like how they ruled India. Imagine if we tried to rule their country? They are always saying ‘Pakis’ should get out and immigrants get all the good jobs, but the British actually have the guts to go into another country and take over and make the people of that country their slaves. How hypocritical is that? They don’t even like immigrants working in their country. […] I can never forget what they did to India. That is their identity: ‘the rulers of other countries’.

Namrika, 18, Moderate Hindu Female, On a Gap-Year.

Existing research on the identity orientations of British Souths have also highlighted the way that history shapes belonging in contemporary British society. There continues to be a social boundary based on history that is particularly ‘bright’ (Alba Citation2005)Footnote6 for some young Sikhs and Hindus. Jaspal and Cinnirella also find that ‘The historical boundary refers to the importance of self-inclusion within the historical or mythological “story” of the nation in order to acquire membership in the national group’ (Jaspal & Cinnirella, Citation2013, p. 171).

As Gurpreet explained:

I think British identity is about celebrating all the things that Britain has done, I think it is all a bit imperialist, but that’s not really surprising as that is British history, it is not really even that, they just ignore all the stuff that Indians have done for Britain. My Papaji (paternal grandfather), he fought in the war for Britain, but it really makes me so angry, he never got an invitation to all the Remembrance Day stuff, when you watch it on telly, where are the Indians? They have got all the old white men sitting there in their wheelchairs like they are only ones who have made a sacrifice. I’m not trying to be out of order! But where are the old Indian men? They are left out. […] British identity is celebrating British stuff, but making it out like it was only the white people who made it happen.

Gurpreet, Moderate Sikh, Female, 22 years old, Master’s Student.

Namrika and Gurpreet’s interviews are good examples of the common sentiments expressed around this topic. They, and others, spoke at length about the British Raj, how the rule of India had affected their grandparents and the sense of sadness and often anger they felt at how their ancestors had been treated by the British at the time, often they would become emotional when recalling these stories These political contexts influenced the way some respondents felt about British identity. For them, the notion itself was so strongly intertwined with events of the past or current political behaviour that it was impossible for them to embrace British identity in any way. This is also found by Jaspal and Cinnirella who note that ‘Those BSA who temporally delineate or compartmentalise colonial Britishness from a contemporary, inclusive and egalitarian Britishness, might be expected to embrace Britishness more readily’ (Jaspal & Cinnirella, Citation2013, p. 164)

4.3. Racism and threat as barriers to Britishness

Another variant of this idea of British identity as ‘negative’ and ‘undesirable’ focused on a perceived culture of hooliganism, threat, and racism, which were experienced as features of Britishness that formed the basis of the identity itself. These young people acknowledged the presence of a British culture and a British identity, yet for them it was devoid of any positive characteristics. Instead, the identity was seen as a representation of the feelings of threat, outsiderness and xenophobia that they had experienced in their lives.

Britishness, it’s about the white people wanting to protect Britain, and make it obvious that even though the country is mixed, it’s still a white country. They feel like they have to protect their identity, I think they feel a bit threatened by all the coloured people in their country. […] That’s why they call us pakis. Their culture is a bit like that, like all the hoodies and all the chavs and skinheads, they are the ones trying to protect British identity.

Rani, Hindu Female, 22, Legal Secretary.

Look at all the celebrations they have for the Queen, you see it on the news, thousands of people outside the palace, waving their flags, it’s like a sea of fucking white people, I have never seen no Indians there. […] It’s like it’s like it their chance to say, this is our celebration, this is our identity, it is British, it’s our time

Tejas 19, Gujerati Male, University Student.

For Rani and Tejas, and others, British identity was thus understood not only as something for ‘white people’, but was seen as a way to threaten members of ethnic minorities. It was perceived as a racist identity, where white British people came together, where they united to ‘protect’ ‘their’ country. During the interviews, young people described British identity as something that was designed to remind them that Britain would never be ‘their country’. These young people often felt that British identity was formulated on British culture, which had many different facets from the Royal Family, to celebrating Remembrance Day, to the image of the Union Jack and the cross of St George. Unlike other respondents who highlighted the fact that Indian people should be included in celebrations, these young people felt that these events and symbols also served as strong boundary markers between these young Sikhs and Hindus on one side, and the white British, celebrating their British culture and British identity on the other.

I don’t like it when all the old people start selling poppies, why should I buy a fucking poppy? The poppy appeal is about the old goreh (white people), it actually really makes me mad. Then when you don’t buy a poppy they look at you as if to say ‘oh yeah there goes another paki, who lives here and isn’t interested with anything to do with our country’. […] Even all this stuff with the Queen, the Royal marches and stuff, I don’t feel anything about it, I don’t feel part of it, it’s for the goras, it’s not for us’

Kulweer 22, Sikh Male, Trainee Account.

Events and symbols associated with ‘British identity’ were thus important in creating ideas of belonging, inclusion and exclusion. Many respondents spoke about the exclusion they felt on what they saw as ‘British days’: the Queen’s Jubilee, Royal Celebrations, St. George’s Day and Remembrance Sunday. Young people saw these events as British celebrations only to be celebrated by the white majority. The Union Jack, Poppies on Remembrance Day, and the events associated with the monarchy were particularly poignant and served as reminders of cultural separation and social boundaries; young Sikhs and Hindus saw these as intrinsic parts of ‘British identity’. British identity was formulated and celebrated by white people coming together to remind others that this was ‘their country’, and these celebrations were ‘theirs’, that this was their chance to celebrate ‘their history’, ‘their way’. This made these young people feel completely excluded from these events and celebrations, and removed from the idea of Britishness itself, which was seen as being celebrated through the medium of this collective identity and participation and pride in these events.

Vadher and Barrett work on British Indians and Pakistanis also uncovered what they called the ‘historical boundary’. Similarly, their work found that

To develop a national identification with a nation whose officially sanctioned and codified history ignores the contributions which other peoples have made to that nation, or ignores the exploitation, enslavement and massacre of other peoples during that nation’s history, may effectively exclude those groups whose ethnic heritage is derived from the peoples who have been treated in these ways. (Vadher & Barrett, Citation2009, p. 451)

4.4. Positive dual-identities (and gender)

In contrast, there were other respondents who had very positive ideas about British identity and their own Britishness; this was the most common pattern that emerged. For many young Hindus and Sikhs, being British was a source of great pride in their lives. They had a very clear sense of what British identity stood for and felt that it was their primary source of belonging, while for others, it was as important as their own ethnic identities. It was described as something that these young people felt comfortable with.

I think British identity has a lot of really good attributes, democracy, tolerance, respect and I really like the way British people kind of mind their own business, unlike Asians. I would say that I am really proud actually of my British identity, I am really proud to be British.

Harjeetpal, 19, Sikh Male, Looking for work.

I am British, it’s not like something that I have ever battled with or had a problem. If you are born here and you live here, that makes you British in my eyes, I guess some people don’t want to take it any further than that especially in our communities people don’t really mix with white people they tend to stick to their own. […] I have always felt more comfortable with white people than Indians anyway, I think I have more in common and I guess that’s why I feel more British than Indian in a way. Our culture is so restrictive especially for women, British culture is less sexist, you can be more free.

Geetanjali, 22, Hindu Female, Masters student.

I am British in the same way as I am Sikh, I’m Punjabi, I’m a Londoner – it’s just another thing that I am, that’s just what I am, that’s it. I enjoy being British the same way I enjoy being Punjabi. […] I think it’s good that we can be everything, we don’t have to choose, choosing would be hard. I can be a Punjabi Londoner!!! Its fine, mum and dad have always told me to have different friends.

Neeta, 20, Sikh-Female, works as a full-time nanny.

The above excepts exemplify the most common expressions of positive accommodations of Britishness. Their descriptions of British identity were less culturally charged than other respondents: it was not about the lack of distinctive culture or traditions, or the lack of togetherness, but instead the focus was on the openness of British identity; it was part of their lives, not demanding, nor particularly culturally rich, but it existed nonetheless – and this was enough. Their descriptions often centered on what they saw as British values and traits, which, to them, constituted the very idea of British identity. Harjeetpals’s interview and many others spoke about ‘tolerance’, ‘equality’, ‘democracy’ as part of the Britishness they enjoy, their descriptions thus fit well with the concept of ‘civic’ nationalism (Breton, Citation1988; Tilley & Heath, Citation2007).

Neeta and Geetanjali also discussed the way that gender can impact identity and feelings of belonging (or not). Many young women, both Sikh and Hindu echoed these sentiments, they felt they had a stronger sense of belonging with the white British majority, they felt that it was led patriarchal and more equal;

Our culture is so restrictive especially for women, British culture is less sexist, you can be more free.

As Neeta describes, the family structure is crucial in this; the extent to which young people are allowed, and encouraged to socialise, meet and have contact with others outside of school shapes how the understand their own Britishness. This was particularly salient for many other young Sikh and Hindu women who felt attracted to the more ‘open and tolerant’ way of life, but were sometimes restricted in how free they were to socialise in the ‘British way’. This was described as ‘going out to drink in bars and clubs’ and ‘having male friends’, which was frowned upon by their parents who wanted them to maintain ‘a good imagine’ in the ‘community’. If we compare this to the positive sense of Britishness based on social activities and contact described by Piral:

I like the culture here. It’s pretty laid back. I think Asians can be really like intense; you have to look a certain way, do certain things. With my white mates, we just have a laugh together, we go out every Friday to the pub, we go football, we go around each other’s houses and play XBox and Playstation, it’s just easy, it’s easier. I am British, we all do the same stuff, no one has ever said anything racist to me, you know, we live their lifestyle, so we are as British as them.

Piral, Hindu-Gujerati Male, 19, Works in family business.

For him, British activities were central to defining British culture and his own sense of belonging,

5. Discussion

5.1. Dual-identities; the role of family, friends and positive social contact

Overall the most common sentiment amongst most of the young people I interviewed was that there was a space in their lives for British identity and being British. I did not find any overarching evidence of self-segregation or a lack of integration amongst these young people; what I did find is a range of ideas and great diversity about the notion and reality of British identity. I found that the way these young people understand what constitutes Britishness and how they relate to it in their day-to-day lives is highly individualistic, but overall, in terms of Berry’s typology, most of my respondents were ‘integrated’, holding both minority and majority identities simultaneously (Berry, Citation1997; Platt, Citation2014).

5.2. The importance of family structures

A majority of the young people I interviewed acknowledged the negative and positive attributes and life experiences of being both a young British-born Sikh or Hindu and a British Asian. Although some of the young people occasionally found it hard to juggle the responsibilities and obligations they felt to their parents and the cultural traditions of their own ethnic group, at the same time as being a young British person, many of these young people had found a way to be both Indian and British. These young people were often those who had had a fairly liberal upbringing and were not under extreme pressures from their families to continue specific religious or cultural traditions. Often these young people had a range of friends, those from South Asian and white British backgrounds, as well as other ethnic groups; they were exposed to different cultures by attending racially mixed schools and enjoyed a range of social activities.

These young people were able to cross in and out of different groups and sources of belonging due to the fact that there were no penalties for them from their parents or peers. Other young people from stricter backgrounds, or those who had mostly South Asian friends, worried about being called a ‘coconut’Footnote7 (Vadher & Barrett, Citation2009, p. 450) and being accused of abandoning their own culture or even of trying to be, or acting ‘white’. Thus, the extent to which there was prejudice and penalties from family and peers about having white friends and engaging in British activities affected the extent to which young people were freely able to enjoy membership to both groups. For some young women the need to maintain a ‘good image’ was challenging and this led them feeling separate from British society not able to enjoy the freedoms they felt were part of this. Going forward, more attention should be paid to how family structures and attitudes held by elder generations towards Britishness impact the extent to which young women, in particular, from the second and perhaps the third generations too, are able to express, experience and navigate their own sense of belonging.

However, most of these young people had found a good middle way whereby they could feel like they belonged to Britain and that they had a sense of Britishness on a day-to-day basis, but could also enjoy the cultural richness of their own communities at the same time (Jandu, Citation2015). Often what was described was a comfort at being part of mainstream British society, but the ability to dip in and out of Sikh and Hindu, culture as and when they wanted, but also as and when the necessity arose, for example, during important religious functions such as Navratri, Vaisakhi, and Garba.

I found that there was great diversity in the experience and attitudes that these young people attached to British identity. For some it was exclusive and xenophobic, and British identity itself came to be defined by the negative experiences that these young people had encountered from white British people. Some saw British identity as a core part of their lives, a comfortable source of belonging, providing a thin glue, but a glue nonetheless. Young people saw British identity as different things, the demands they put on this national identity also varied. For some it was ‘enough’ to have positive values and traits of tolerance, democracy and respect; while for others, ‘having a passport’, being born here and residing here were sufficient determinants of this ‘identity’. For another group, British identity could not even be considered to be a viable identity through its lack of rich, cultural traditions, yet this did not mean they led parallel lives – they often felt a culturally thinner, more civic, sense of being British that was based on legally being British citizens and structural integration. Overall, I found that a majority of these young people had positive orientations to both groups: they had ‘diverse dual-identities’. That is, dual identities understood and experienced in diverse ways reflecting the individual themselves (Bhambra, Citation2015).

5.3. Thick and thin versions of Britishness; differing conceptualisations of Britishness

There were thus ‘thick’ and ‘thin’ versions of British identity: for some, Britishness needed to be culturally ‘thicker’, there was a desire for special days (Oonk, Citation2020), customs, food, music and a sense of community between all people living in Britain. Britishness was in a sense seen as being too civic, it needed more cultural weight to make it viable and appealing as an identity option. Alternatively, there were those young people who thought that Britishness was too ethnic in its character; it was about white people, doing white things. Perceived xenophobia and exclusivity on the part of white Britons were key parts of this more ethnic conception of the British nation (see Tilley & Heath, Citation2005). For others Britishness was a thinner glue: a civic identity based on respect for British institutions, the legal citizenship of being born here and living here and that having this sense of civic, or thinner, British identity was sufficient to ‘belong’.

Kelman (Citation1997) has differentiated between two different types of national attachment, which individuals may have to their nation; ‘sentimental’ and ‘instrumental’. The former is seen as an emotional attachment where ‘people feel that the group closely reflects or confirms their own personal identity, allowing them to feel involved as a group member and committed to the group’s traditions and values’ (Vadher & Barrett, Citation2009, pp. 433–434). The latter is one where national attachment fulfils the practical needs and interests of the individual, ‘so that the individual accepts the rules and regulations of the group and is committed to the group’s institutional arrangements and operating values’ (Vadher & Barrett, Citation2009). The thinner and thicker attributes described give insight into what makes up these instrumental or emotional conceptualisations of Britishness for these young people.

Anderson describes the ‘imagined community’ (Anderson, Citation2006) and the importance of imagination is an important one in this debate on Britishness. Some young people, often due to their own positive, diverse contact experiences and networks, were able to imagine a Britain that was tolerant and accepting. Others imagined a country where they would always be outsiders, but within their lives they still felt a sense of community, be it local, based on a place of worship or their family and friends who accepted them. Britishness was thinner here, it was about institutions, freedom and often the ability to maintain cultural and religious identities more freely.

5.4. Accommodating multiple identities

One finding I wish to emphasize here is the fact that many of the young people I interviewed who had a thinner more civic conceptualisation of Britishness were not only happy with this thinner glue, but they felt that the comparative thinness of Britishness was why they could accommodate it alongside their thicker, and often more demanding ethnic identity (Bhambra, Citation2015; O’Connor, Citation2016). To them, the fact that Britishness was based on a less demanding, more civic notion of identity meant that in day-to-day life they could easily hold dual-identities without impeding their sense of belonging in either social circle.

They were thus able to embrace a civic Britishness, which was often understood as a sound institutional and legal framework that they felt part of, whilst enjoying the thicker ethno-religious-cultural aspects of being a Hindu or a Sikh. These young people felt that if Britishness were made thicker and more culturally demanding it would make the accommodation more difficult; it would in fact be harder to be British and be a Sikh or Hindu and this scenario would lead them into a place where they had to make a ‘choice’. Many of them thus simultaneously held ‘sentimental’ attachment to their own culture and religion, as well as an ‘instrumental’ attachment to being British.

Perceptions of British identity are diverse. Yet this is neither necessarily surprising nor problematic given that we do not have a clear statement about the core components of British identity and its constitutional ideals. It is thus not simply the case that young people have a strong sense of ethnic identity and that this therefore stands in the way of a national identification. There have been fears that multiculturalist policies have supported the maintenance of ethnic culture and ethnic identity and as a result have directly undermined and hindered the scope for the development of an overarching national identity (Platt, Citation2014, p. 5). For a majority of these young people, it is simply not a case of the either/or scenario envisaged and espoused by nervous politicians such as David Cameron (Cameron, Citation2011), many of these young people have a positive sense of Britishness, but this is experienced in diverse ways.

We cannot simplify their complex, intricate experiences of identity formation and belonging into any essentialised typology in which national identification and ethnic identification stand at opposite ends, nor one where we do not appreciate that there is diversity within diversity in the way that people from minority groups understand and accommodate Britishness as individuals rather than as members of ethnic groups.

6. Conclusion

I would conclude by saying that I found that minority and majority cultures are not separate entities. In the future we may see more hybrid identities, and amalgamations of minority and majority traditions. For example, I found that cultural and religious events in minority cultures were being changed to reflect living in a liberal egalitarian environment. ‘Lohri’, which is a traditional celebration for the birth of boys in Punjabi culture, is now being celebrated for the birth of girls too. Many Hindu males were now fasting on ‘Karva Chauth’, a fast that women traditionally take for the well-being of their husbands. Ethnic cultures are in fact changing to reflect the second generation’s rejection of what they saw as unequal cultural traditions. They saw this as a reflection of being British and respecting the right for equality, which they saw as an intrinsic part of Britishness. Minority and majority cultures can in fact influence each other and create cultural content.

Lastly, with Brexit and anti-immigrant sentiment leading up to and after the referendum, these findings can help us in understanding how this event may shape ideas about Britishness and belonging for newer migrants. With the explicitly anti-immigrant Leave campaign with its associated imagery in the media, there is a danger that those migrants still choosing to be part of British society may well continue to feel like targets going forward. This one event could have a powerful legacy in the way that these communities feel included. Indeed, for those with already negative ideas about Britishness and the openness of British society, it may well have strengthened further these social boundaries. This has been the case for some members of ethnic minorities who felt that they were the targets of the immigration debate even when they were British born (Begum, Citation2018; Runnymede Trust, Citation2015). Again, this highlights the diversity within minority communities as much as been made of the high vote to leave by members of the British-Indian community. Existing notions of inclusion as well as socio-economic wellbeing and access to resources surely have shaped the diverse responses to Brexit we see across minority groups, and within these groups.

With this rhetoric on belonging and migration, if we can learn from the experiences of more established communities how processes of belonging plays out and their long term effects, we can apply this knowledge into including newer migrants who have been more explicitly targeted in the campaign to leave the European Union. Thus, there is a need for greater community engagement and policies directed in counteracting the long-term impact of these events and perhaps more focus on the inclusive, civic aspects of Britishness that have facilitated belonging for these young people. This will be crucial to ensure that these events do not stand as a barrier to a positive sense of Britishness and inclusion as it has done for some of these young people in this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Manmit Bhambra

Manmit Bhambra is based at the LSE and teaches across the social sciences. Her research interests are centered around identity politics and formation, national identities as well as the broader themes of inclusion and minority rights.

Notes

1 MCPs refer to Multiculturalism Policies.

2 For further discussions (see Cohen, Citation1995; Colley, Citation1992a, Citation1992b; Dowds & Young, Citation1996; Ethnos, Citation2005; Heath & Roberts, Citation2008; Jacobson, Citation1997a, Citation1997b; Langland, Citation1999; Parekh, Citation2000a, Citation2000b; Modood, Citation2007; Platt, Citation2014; Smith & Jarkko, Citation1998; Tilley et al., Citation2004).

3 Data downloaded from Office of National Statistics website and available here: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/religion/articles/religioninenglandandwales2011/2012-12-11

4 See Appendix containing demographic information (with anonymised names) for all respondents.

5 80 interviews were conducted in the main data collection process, and follow-up interviews were conducted over the next two years with a purposeful sample (in terms of gender, religion, occupation) to see if any new themes emerged.

6 Richard Alba distinguishes social boundaries as being ‘bright’ or ‘blurred’. For further discussion see Alba (Citation2005).

7 A term used in the British Asian community to describe someone who is acting like they are ‘white on the inside’ to insinuate that the person has lost, or turned their back on, their cultural heritage.

References

- Alba, R. D. (2005). Bright vs. blurred boundaries: Second-generation assimilation and exclusion in France, Germany, and the United States. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 28(1), 20–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141987042000280003

- Alba, R. D., & Foner, N. (2015). Strangers no more: Immigration and the challenges of integration in North America and Western Europe. Princeton University Press.

- Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. Verso Press.

- Barry, B. (2001). Culture & equality: An egalitarian critique of multiculturalism. Polity Press.

- Baumann, G. (1996). Contesting culture: Discourses of identity in multi-ethnic. Cambridge University Press.

- Begum, N. (2018). Minority ethnic attitudes and the 2016 EU referendum. In Brexit and public opinion. The UK in a Changing Europe. http://ukandeu.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Public-Opinion.pdf.

- Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 46(1), 5–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x

- Bhambra, G. K. (2016a). Brexit, the commonwealth, and exclusionary citizenship. https://www.opendemocracy.net/gurminder-k-bhambra/brexit-commonwealth-and-exclusionary-citizenship.

- Bhambra, G. K. (2016b). Viewpoint: Brexit, class and British national identity. https://discoversociety.org/2016/07/05/viewpoint-brexit-class-and-british-national-identity/.

- Bhambra, M. K. (2015). The social worlds and identities of young British Sikhs and Hindus in London [Doctoral dissertation, University of Oxford].

- Bingham, J. (2012). Multiculturalism past its sell-by date warns race expert. The Telegraph. Retrieved November 12, 2012. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/politics/9544252/Multiculturalism-past-its-sell-by-date-warns-race-expert.html.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Breton, R. (1988). From ethnic to civic nationalism: English Canada and Quebec. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 11(1), 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.1988.9993590

- Cameron, D. (2011). Speech to the Munich Security Conference.

- Cantle, T. (2012). Interculturalism: The new era of cohesion and diversity. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Casey, L. (2015). The Casey review: A review into opportunity and integration. Ministry of Housing, Community and Local Government.

- Cohen, R. (1995). Fuzzy frontiers of identity: The British case. Social Identities, 1(1), 35–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630.1995.9959425

- Colley, L. (1992a). Britons: Forging the nation 1707–1837. Yale University Press.

- Colley, L. (1992b). Britishness and otherness: An argument. The Journal of British Studies, 31(4), 309–329. https://doi.org/10.1086/386013

- Dorling, D., Stuart, B., & Stubbs, J. (2016). Brexit, inequality and the demographic divide. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/brexit-inequality-and-the-demographic-divide/.

- Dowds, L., & Young, K. (1996). ‘National identity’. In R. Jowell, J. Curtice, A. Park, L. Brook, & K. Thomson (Eds.), British social attitudes: the 13th report. Dartmouth.

- Ethnos. (2005). Citizenship and belonging: What is Britishness? CRE.

- Ford, R., & Sobolewska, M. (2018). Brexit and public opinion. The UK in a Changing Europe. http://ukandeu.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Public-Opinion.pdf.

- Gaskell, G. (2000). Individual and group interviewing. In M. Bauer, & G. Gaskell (Eds.), Qualitative researching with text, image and sound: A practical handbook (pp. 38–56). Sage Publications.

- Güveli, A., & Platt, L. (2011). Understanding the religious behaviour of Muslims in the Netherlands and the UK. Sociology, 45(6), 1008–1027. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038511416165

- Heath, A. F., & Demireva, N. (2014). Has multiculturalism failed in Britain?, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 37(1), 161–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2013.808754

- Heath, A. F., & Roberts, J. (2008). British identity: Its sources and possible implications for civic attitudes and behaviour. Research report for Lord Goldsmith’s Citizenship Review.

- Heath, A. F., & Spreckelsen, T. (2014). European identity. In J. A. Elkink, & D. M. Farrell (Eds.), The act of voting: Identities, institutions and locale (pp. 11–34). University College Dublin.

- Huntington, S. P. (1993). The clash of civilizations? Foreign Affairs, 72(3), 22–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/20045621

- Jacobson, J. (1997a). Perceptions of Britishness. Nations and Nationalism, 3(2), 181–1999. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1354-5078.1997.00181.x

- Jacobson, J. (1997b). Religion and ethnicity: Dual and alternative sources of identity among young British Pakistanis. Ethnic and Racal Studies, 20(2), 238–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.1997.9993960

- Jandu, G. S. (2015). London Sikh youth as British citizenry: A frontier of the community’s global identity? In K. Jacobsen, & K. Myrvold (Eds.), Young Sikhs in a global world negotiating traditions, identities and authorities (pp. 231–260). Routledge Press.

- Jaspal, R., & Cinnirella, M. (2013). The construction of British national identity among British South Asians. National Identities, 15(2), 157–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/14608944.2012.728206

- Joppke, C. (2004). The retreat of multiculturalism in the liberal state: Theory and policy. The British Journal of Sociology, 55(2), 237–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2004.00017.x

- Kalra, V., & Kapoor, N. (2008). Interrogating segregation, integration and the community cohesion agenda. CCSR Working Papers. Cathie Marsh Centre for Census and Survey Research.

- Kelman, H. C. (1997). Nationalism, patriotism and national identity: Social psychological dimensions. In D. Bar-Tal & E. Staub (Eds.).

- Kundnani, A. (2007). Integrationism: The politics of anti-Muslim racism. Race and Class, 48(4), 24–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396807077069

- Langland, R. (1999). Britishness or Englishness? The historical problem of 347 national identity in Britain. Nations and Nationalism, 5(1), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1354-5078.1999.00053.x

- Legard, R., Keegan, J., & Ward, K. (2003). ‘In-depth interviews.’. In J. Ritchie, & J. Lewis (Eds.), Qualitative research practice. A guide for social science students and researchers (pp. 138–169). Sage Publications.

- Manning, A., & Roy, S. (2010). Culture clash or culture club? National identity in Britain. The Economic Journal, 120(542), F72–F100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2009.02335.x

- Miall, D. S. (Ed.). (1990). Humanities and the computer: New directions. Clarendon.

- Modood, T. (2007). Multiculturalism. Polity Press.

- O’Connor, M. (2016). The Indian Diaspora in the UK: Accommodating Britishness. Indialogs, 3, 137–150. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/indialogs.24

- Oonk, G. (2020). Sport and nationality: Towards thick and thin forms of citizenship. National Identities.

- Palmer, A. (2012). Multiculturalism has left Britain with a toxic legacy. The Telegraph. Retrieved November 12, 2012. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/immigration/9075849/Multiculturalism-has-left-Britain-with-a-toxic-legacy.html.

- Parekh, B. (2000a). The future of multi-ethnic Britain (The Parekh Report). Runnymede Trust/Profile Books.

- Parekh, B. (2000b). Defining British national identity. The Political Quarterly, 71(1), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.00274

- Phillips, T. (2005). Manchester council for community relations.

- Pilkington, A. (2008). From institutional racism to community cohesion: The changing nature of racial discourse in Britain. Sociological Research Online, 13(3), 6. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.1705

- Platt, L. (2013b). How might we expect minorities feelings of ethnic, religious and British identity to change, especially among the second and third generation? Driver.

- Platt, L. (2014). Is there assimilation in minority groups' national, ethnic and religious identity? Ethnic and Racial Studies, 37(1), 46–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2013.808756

- Runnymede Trust. (2015). This is still about us. https://www.runnymedetrust.org/uploads/Race%20and%20Immigration%20Report%20v2.pdf.

- Sian, K. P. (2013). Losing my religion: Sikhs in the UK. Sikh Formations, 9(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/17448727.2013.774707

- Silverman, D. (2010). Doing qualitative research: A practical handbook. Sage.

- Smith, T. W., & Jarkko, L. (1998). National pride: A cross-national analysis, GSS report no. 19. University of Chicago.

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1994). Grounded theory methodology: An overview. In N. Denzin, & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 273–284). SAGE.

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel, & W. G. Austin, (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relation (pp. 7–24). Chicago: Hall Publishers.

- Tilley, J., Exley, S., & Heath, A. F. (2004). What does it take to be truly British? In A. Park, J. Curtice, K. Thompson, M. Phillips, M. Johnson, & E. Clery (Eds.), British social attitudes: The 21st report. Sage.

- Tilley, J., & Heath, A. F. (2007). The decline of British national pride. The British Journal of Sociology, 58(4), 661–678. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2007.00170.x

- Vadher, K., & Barrett, M. (2009). Boundaries of Britishness in British Indian and Pakistani young adults. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 19(6), 442–458. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.1006

- Vasta, E. (2007). From ethnic minorities to ethnic majority policy: Multiculturalism and the shift to assimilationism in the Netherlands. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30(5), 713–740. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870701491770

- Verkuyten, M., & Zaremba, K. (2005). Inter-ethnic relations in a changing political context. Social Psychology Quarterly, 68(4), 375–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250506800405

- Worley, C. (2005). It’s not about race. It’s about the community: New labour and community cohesion. Critical Social Policy, 25(4), 483–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018305057026

- Wright, O., & Taylor, J. (2011). Cameron: My war on multiculturalism. The Independent. Retrieved November 12, 2012. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/cameron-my-war-on-mul-ticulturalism-2205074.html.