?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Ferdowsi's Shahnameh has played a significant role in shaping the national identity of Iranians, transcending linguistic, religious, cultural, and ethnic differences. This paper examines the perceptions of Iranian Sunni Muslims, and non-Muslim minorities regarding Ferdowsi and Shahnameh. A survey was conducted on Persian Twitter using simple items, and the questionnaire was also distributed among Shia Muslims, who form the majority in Iran. The findings demonstrate unanimous agreement among participants regarding the role of Ferdowsi and Shahnameh in unifying Iran geographically and shaping its cultural and secular national identity against Islamic anti-nationalism identity.

Introduction

Ferdowsi and his major book, Shahnameh, played a significant role in homogenizing and revival of Iran's national identity structure, arguably ranking among the most influential factors. While various factors, such as religion, ethnicity, history, language, and others, have contributed to the formation of Iran's national identity, the impact of Ferdowsi and Shahnameh stands out as particularly noteworthy. Iran's secular and nonreligious nationalism is strongly influenced by the structural and semantic elements present in the tales and narratives of Shahnameh, alongside the lasting impact of Ferdowsi on Iranian thought.

Persian dynasties, particularly the Saffarid (879-840) and the Samanid (819-999) dynasties, played a pivotal role in liberating significant portions of Iran and Central Asia from more than two centuries of Arab occupation. The Saffarid Dynasty, under the leadership of Ya'qub ibn al-Layth al-Saffar, successfully challenged the Abbasid Caliphate and established an independent Persian state. Their military campaigns not only regained territorial control but also revitalized Persian culture and language. Similarly, the Samanid Dynasty, led by Saman Khuda, played a crucial role in the cultural and intellectual renaissance of Iran (Dabiri, Citation2010). They patronized Persian literature, arts, and sciences, resulting in a flourishing of Persian identity and a revival of national pride (Yarshater, Citation1993). These historical developments demonstrate that Persian dynasties were instrumental in the preservation and restoration of Iranian national identity, contributing significantly alongside Ferdowsi and Shahnameh.

Historical evidence points to the resilience and tenacity of the Iranian people themselves during the centuries of Arab occupation. Despite the dominance of Arabic language and Islamic culture, Iranians maintained their distinct cultural and linguistic identity. The Iranian populace's resilience, combined with the efforts of Persian dynasties, allowed for the continuous expression of Iranian national identity, even in the face of foreign occupation. The efforts of Persian dynasties further facilitated the expression of Iranian national identity.

Ferdowsi and his renowned masterpiece, the Shahnameh, hold immense significance as they continued the legacy of Iranian dynasties in reviving Persian culture and language during the past. Amidst the overwhelming influence of Arabic and Islamic culture, Ferdowsi emerged as a central figure in the revival of Iranian identity. His significant role in revitalizing the legacy of Persian dynasties cannot be overstated. Ferdowsi's Shahnameh played a pivotal role in reviving Persian culture by celebrating and documenting the pre-Islamic epic tradition, thereby preserving Iranian heritage and bridging the past with the present. Furthermore, Ferdowsi's contributions extend beyond his historical context and continue to hold relevance in contemporary times (Amanat, Citation2012). His work has nurtured secularism and played a crucial part in shaping the national identity of Iran. By emphasizing the importance of Ferdowsi's contributions, we recognize the enduring impact of his efforts in fostering a sense of unity and pride among Iranians.

Most of the researchers have concentrated on the literary and epic role of Ferdowsi in Iran’s history. Scant attention has been given to his political and cultural role in shaping the concept of Iran among religious minorities. Ferdowsi is one of the rare individuals whose vital role in the formation of Iran’s national identity geoculture and its cultural geography is acknowledged by all Iranians (including Muslims and non-Muslims, atheists and believers, and religious and non-religious people). All Sunni and Shia Muslims within Iran and all non-Muslims, from Khorasan to Kurdistan and from Kurdistan to Samarkand, admit that Ferdowsi has exerted profound influence on their culture, history, literature, art, and geography.

However, it is important to acknowledge that diverse political groups may hold varying opinions and interpretations regarding the role of the Shahnameh and its impact on Iran's national identity. These viewpoints can often be influenced by their respective positions, power dynamics, and political affiliations within Iran. Understanding and considering these different perspectives is crucial to gaining a comprehensive understanding of the complex relationship between the Shahnameh, national identity, and politics in Iran.

There are several prominent groups with different perspectives on Iran's national identity, and their views on the Shahnameh and Ferdowsi's role can vary significantly. These variations in perspective can stem from differing interpretations of history, cultural backgrounds, political ideologies, and personal experiences.

For instance, the Islamist groups in power adhere to an extreme interpretation of Islamic ideology and advocate for the implementation of strict religious laws within society. Their views on Ferdowsi and the Shahnameh can differ due to their approach to Islamizing the epic. While some may acknowledge the literary value of the Shahnameh, they tend to emphasize its Islamic aspects, seeking to align it with their religious beliefs. These groups interpret Ferdowsi's writings through an Islamic lens, highlighting religious themes present within the epic.

Moreover, some other Islamists tend to emphasize the non-religious and antiquarian elements of Ferdowsi's thought when analyzing Shahnameh. They view the Shahnameh as a work that transcends religious boundaries and portrays non-religious or even anti-religious themes. In their interpretation, they perceive the epic as being at odds with revolution and antithetical to the principles of Shia Islam. This perspective underscores their belief that the Shahnameh carries a secular and non-religious character that opposes the revolutionary ideals associated with Shia Islam.

Nonetheless, Ferdowsi’s influence on Islamist literature is limited. After the Islamic Revolution in Iran, most of the Shia clergies and some Shia intellectuals have regarded Shahnameh as an abominable source. In fact, after the Islamic revolution, most of the Islamist groups and clergies began to promote the idea that Ferdowsi and all other pan-Iranist poets and mystics, are part of the non-Islamic legacy; therefore, it is religiously illegitimate to refer to them as valid historical sources. Additionally, non-Islamic epic literature is crooked in the eyes of most Shia and Sunni Muslim scholars; hence, they try not to refer to them. There is a controversy among Muslim scholars and researchers as to whether Ferdowsi was a Sunni or Shia believer. Some researchers claim that Ferdowsi was Shia since he lived in the time of Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi and was subject to his usurpation and also wrote poems about the mythological past of Iran. Accordingly, these scholars have a Shia, justice-centered, and revolutionary interpretation of Ferdowsi’s books and poems. This type of interpretation also found support among Iranian left-wing thinkers and writers.

Left-wing and Marxist groups in Iran have varied perspectives on national identity and the role of the Shahnameh in Iran. Generally, they approach national identity from a class-based and socio-economic perspective, emphasizing the importance of addressing social inequalities and challenging dominant power structures. For some left-wing and Marxist thinkers, the Shahnameh seen as a reflection of feudal or pre-capitalist societal structures, and they might critique its portrayal of monarchy and aristocracy. For these groups, the legends depicted in the Shahnameh, particularly the mythical and epic figures such as Zahak, are viewed as symbolic representations of capitalism. Additionally, they emphasize that many of the heroes in the Shahnameh strive for justice and greater equality. The writings of left-wing thinkers regarding the Shahnameh often revolve around an interpretation focused on justice, drawing upon their understanding of ‘Dad’ (justice) as portrayed within the epic. From their perspective, the Shahnameh is perceived as an ideological text rather than solely a national or non-religious one.

On the contrary, some researchers, including Sunni scholars from Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and some other countries, contend that Ferdowsi was a Sunni believer (Beidollahkhani, Citation2022). To support their view, these scholars refer to Ferdowsi’s poems in which he has praised Abu Bakr, Omar, and Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi, as well as some books, historical sources, and researchers such as Jafar Langeroodi, Mohammad Ali Eslami Nodoushan, etc. Despite all these controversies, no research has been carried out to explore Iranian minorities’ (i.e. Sunni Muslims and non-religious minorities) perceptions of Ferdowsi and Shahnameh. In the absence of this line of inquiry, some scholars, including ethnicity-oriented researchers, assert that Ferdowsi and its book (i.e. Shahnameh) are completely Persian-oriented and belong to Persian and Shia Iranians.

Some ethnic groups, such as pan-Kurdish nationalist groups, Turks, and certain religious minorities, who frequently experience economic, ethnic, and social discrimination and have their rights suppressed, hold a critical perspective on Iran's national identity. They perceive this identity, along with its symbols, including the Shahnameh, as inherently ethnic and exclusive to the Persian community. Additionally, Ferdowsi is seen as a symbol of discrimination. Their focus lies in challenging the notion of Iranian national identity as they analyze the Shahnameh through the lens of their own ethnic, linguistic, and cultural backgrounds. Consequently, they interpret the role of this literary work as promoting ethnic bias and racism.

Radical Islamists in positions of power, who are closely aligned with Iran's government, and certain ethnic groups occasionally find common ground in their interpretations of the Shahnameh. Despite their divergent perspectives on other matters, they may converge in their understanding and portrayal of the Shahnameh, emphasizing specific aspects that resonate with their respective agendas or narratives. This convergence of interpretive viewpoints can create unexpected parallels between these groups, particularly in relation to the significance of the Shahnameh and its role within the broader context of Iranian identity.

Both of these groups share the belief that the Shahnameh and Ferdowsi lack worth and should not be esteemed, though their ethnic and religious rationales differ. Islamists perceive Ferdowsi and the Shahnameh as rivals to religious texts, seeing them as a potential threat to advancing a sectarian- Islamic identity. Meanwhile, ethnicists consider the works of Ferdowsi and the Shahnameh as possessing fascist elements, arguing they lack value for the nation as a whole and a unifying identity for all Iranians. They maintain that as the texts were not written in their languages nor align with their historical and identity narratives, they cannot serve as the foundation for national unity.

The data from our research endeavors to provide relative evidence supporting the significant role of Ferdowsi in revitalizing and fostering solidarity within the non-religious national identity among Iranians, including religious and ethnic minorities. Naturally, it is important to acknowledge that the data obtained from our research holds a relative nature and cannot be deemed definitive. This is primarily due to the fact that the data was collected from social media and based on a limited sample size. However, it is worth noting that this sample represents a diverse and statistically significant community of educated Iranians who possess knowledge of Ferdowsi and his work Shahnameh. These individuals are well-acquainted with his book, and many of them actively engage in academic, political, and intellectual discussions on Twitter.

The present study adopts a survey-based approach, utilizing closed-type items on Twitter, to gather data on the religious and ethnic perspectives of researchers with Shia or Sunni religious orientations, as well as those with left-wing orientations, and individuals with an Iranian ethnicity focus (e.g. Kurds, Turks, and Arabs) regarding Ferdowsi.

Moreover, most Muslim and non-Muslim Iranians have a non-religious perception of Ferdowsi and his significant role in Iran’s geography and territorial integrity. The researchers focused on Shahnameh because almost all Iranians are familiar with it through their ancestors or education in primary and secondary schools and the book is usually kept as a general literary and mythological source in every Muslim and non-Muslim household. In addition, many Iranians gain more information about Shahnameh through their education, studies, exposure to advertisements and TV/radio programs, and social and political interactions in the social media. After the Islamic revolution in Iran, public interest in Ferdowsi and Shahnameh as a national symbol has increased despite the Shia Islamist regime’s opposition to non-religious symbols and characters. Assessing the significance of Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh as a mythological text in the revival of secular national identity in Iran can have a notable contribution to pinpointing the elements of Iranians’ collective identity. This study explores perceptions of Sunni Muslims, Shia Muslims, and non-Muslim minorities (Jews, Zoroastrians, Christians) on Ferdowsi and Shahnameh. Using a survey on Persian Twitter and questionnaires among Shia Muslims, findings indicate unanimous agreement. Chi-square and one-way ANOVA analysis validate results. Ferdowsi and Shahnameh are recognized for unifying Iran geographically and shaping its cultural and secular political identity.

Conceptual framework

Myths, epics, and its various symbols play a significant role in reviving national identity symbols (Bell, Citation2003). A myth is the narrative accepted by the people about the roots and foundations of societies and nations and expresses the way today’s world, behaviors, customs, and traditions are formed. In many cases, a myth has a deep connection with religious foundations. Specifically, from a political perspective, myths and epics give meaning to societies’ political culture and, in the nation building process, are displayed as successive examples and role models for future generations (Thio, Citation2007; Zene, Citation2007). In this regard, the important thing is how myths are exploited to construct national identity and subsequently give meaning to the society’s political values to shape people’s attitude in a country (Figueira, Citation2002). Thus, a myth plays a vital natural (and sometimes manipulative) role in the process of nation building.

Fundamental national myths and epics are a sacred history shedding light on the secret of creation and comprise the eternal origin of every ritual, idea, and action established once and for all at the time of the beginning of mythology and has become an example ever since. Myth may be regarded as a system of associations that is shaped in the space between form, concept, and meaning. In fact, in a myth, the concept disrupts the form and connects to the meaning. Myths manipulate reality (Miller, Citation2014). They convert history to nature and present a historical matter as partial, singular, historical, and eternal.

As a solid structure, national epics and myths form the social foundation and identity of people and create meaning for them. From a constructivist view toward identity, myth can be the center of human actions. Constructivists believe that national identity is an intersubjective and mental construct (Pfadenhauer & Knoblauch, Citation2018). In a similar vein, ancient mythological and epic texts can build mental identities collectively and then nationally. Human actions are formed and gain meaning in the social space. This process of sense making can give a symbolic form to social realities. Building reality refers to getting meaning out of reality and perceiving it from a particular social viewpoint (Bader, Citation2001). The foundation of constructivism is a normative issue, and these norms can create common values and give a historical state to the reality that is being formed. The reality emerging from social activists’ perceptions of their actions and mental characteristics shapes identity (Kubalkova et al., Citation2015). Myths constitute the objectification of human social experience and can create common identity structures in the form of a social construction. Myths, along with epics, give continuity to collective identities over time and then distinguish them from others (Beeman, Citation2000; Sethi, Citation1999).

As a mythological and epic text, Ferdowsi's Shahnameh revives various aspects of Iranians’ collective identity, minimizing the role of religion in identity construction and positioning the text as a consensus-builder for national identity.

Ferdowsi's epic achieves this by weaving together various themes, symbols, and narratives that resonate with the Iranian collective consciousness. For instance, the epic celebrates the virtues of bravery, honor, and loyalty, which are deeply ingrained in the Iranian cultural fabric. Through the portrayal of heroic characters and their struggles, the poem reinforces a collective identity rooted in these values (Farhat-Holzman, Citation2001). Furthermore, Ferdowsi skillfully incorporates historical events, such as the pre-Islamic Persian empires, which serve as cornerstones of Iranian heritage. By emphasizing these historical narratives, the poem establishes a sense of continuity and pride in the Iranian cultural identity across time.

Shahnameh encompasses a rich tapestry of stories that contribute to the construction of collective identity. One prominent example is the story of Rostam and Sohrab, which explores themes of sacrifice, fatherhood, and tragic destiny. This tale resonates deeply within the Iranian psyche, highlighting the importance of family, lineage, and the inevitability of fate. Another example is the character of Zahhak, a tyrant king corrupted by his quest for power. Zahhak symbolizes the eternal struggle between good and evil, and his defeat by the heroic figure of Kaveh embodies the triumph of righteous resistance against oppression. Arash Kamangir (the Archer) is another epic story from the Shahnameh that explores the concept of borders and national identity, as well as the division between Iranians (insiders) and non-insiders, specifically the Turanians.

These stories, among many others in Shahnameh, serve as foundational pillars that shape the collective identity of Iranians by engendering a sense of shared values, historical consciousness, and socio-cultural resilience.

The appropriation of Shahnameh by opposing groups within Iranian society is made possible due to the inherent multi-faceted nature of the poem. Its structure and content offer interpretive flexibility, allowing different factions to find resonance with their own perspectives. For instance, some Iranian nationalists might emphasize the epic's celebration of Persian identity and use it to foster a sense of cultural pride and unity. On the other hand, certain Islamist groups might focus on the epic's moral and ethical teachings, seeking to align it with their religious beliefs and highlight its Islamic dimensions. Furthermore, ethnic minority groups within Iran may appropriate Shahnameh to assert their unique cultural identities within the broader Iranian narrative. The poem's openness to diverse interpretations and adaptability to varying socio-political contexts enable its appropriation by different groups, revealing the complexity and dynamism of Iranian identity.

Many non-Shia and non-Muslim Iranians establish an identity-based relationship with Shahnameh through its mythological and epic content. This leads to the revival of an intersubjective national identity between them and other secular Muslim citizens (Gholami, Citation2015). This identity is in opposition to political Islam and its hegemonic discourse signifiers. As a mythological and epic symbol, Shahnameh connects Iranians beyond religion. This is in stark contrast to Shia political Islam, which typically divides Iranians to self and others based on religious discrimination. Shia political Islam is a hegemonic discourse and the major identity vision of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Based on this discourse, Iraqi and African Shias and even Arab Sunnis and non-Arab Muslims who subscribe to the ideologies of Shia political Islam with regard to opposing the west and Israel are given priority to the political system over Iranian minorities and non-Muslims. They are believed to be closer to the political system than secular and non-Muslim Iranians or Muslim Iranians who oppose the Shia political Islamic thinking.

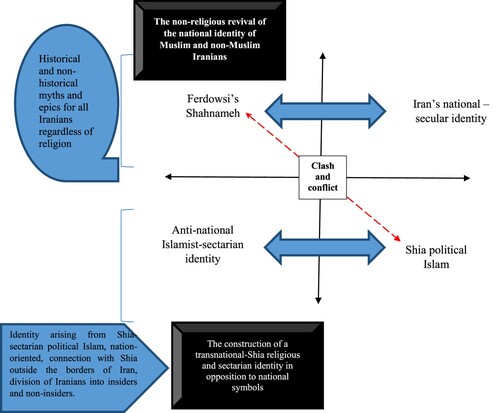

depicts a significant confrontation and conflict between Ferdowsi's Shahnameh and the sectarian and Islamist identity characterized by an anti-national stance. The visual representation clearly demonstrates that Ferdowsi's Shahnameh is intricately linked and aligned with the secular national identity of Iran. However, it stands in stark contrast to Shiite political Islam and its sectarian identity, which prevails within the country. The construction of a transnational-Shia religious and sectarian identity, promoted by the ideological framework of the Islamic Republic, stands in opposition to Iran's national symbols. This political Islamic Shia identity aims to attract non-Iranian Muslims while downplaying the significance of Iran's national identity. On the contrary, Shahnameh and its epics serve as a revival of Iran's national historical symbols, which transcend religious boundaries and encompass the non-religious aspects of the national identity of both Muslim and non-Muslim Iranians. Shahnameh attracts a wide range of Iranian citizens who have experienced discrimination under the religious ideological system of the Islamic Republic. Its inclusive nature allows individuals from diverse backgrounds to connect with and embrace their shared national heritage.

Ferdowsi as a text: hermeneutic analysis of research on Ferdowsi among Iranians in Twitter

Given the importance of Ferdowsi and his Shahnameh among Iranians, numerous interpretations about him have been published. In general, most of the studies on Ferdowsi can be classified under one of the following three categories.

The first category entails researches and books that have examined the literary, mythological, and epic aspects of Shahnameh and explored Ferdowsi’s thoughts from the perspective of literature, epic poems, linguistic issues, poetic linguistic understanding of Shahnameh (Gabri, Citation2015), the role of Shahnameh in Iranian national identity and idealism based on Shahnameh’s text (Gabbay, Citation2023), the sanctity of Shahnameh (Mousavi, Citation2019), and the mythology and aesthetics of Shahnameh (Yaghooti, Citation2018). These studies have focused on the literary aspect of Shahnameh and emphasized the poet’s eloquent power and Shahnameh’s magnificent language as the keys to the longevity of this epic. Other literary aspects of researching Shahnameh, which have been explored in Persian and some English articles, include the interpretation of good and evil as well as familiarity with evil demons and femininity and masculinity in Shahnameh (Pierce, Citation2015), the ethics of war and peace in Shahnameh (Mahallati, Citation2015), the tragedies of Shahnameh and women (Hariri, Citation2018), and different interpretations of the tragic story of Rostam and Sohrab (Clark, Citation2010; Cross, Citation2015).

The second category entails studies that have tried to shed light on Ferdowsi’s character, life, thinking, and Shahnameh from the historical, social, and cultural development perspectives. These studies have particularly focused on the social, political, and cultural history at the time of Ferdowsi. In this line of inquiry, Ferdowsi’s religious, nationalistic, and rationalistic beliefs are emphasized or the historical context in which Shahnameh was developed is explored to collect evidence about different dynasties and the history of Iranian kingdoms, hence offering historical interpretations (Hayes, Citation2015; Rezaei, Citation2016; Sataravala, Citation2023). Some other subjects that are explored within this second category are the role of religion in Shahnameh and its myths/heroes (Davis, Citation2015; Sadeghi, Citation2004), comparison of Shahnameh’s heroes, artists, and characters with other myths in the world and the role of art and Hellenistic culture in Shahnameh (Skupniewicz & Maksymiuk, Citation2019), and the role of sedition and betrayal in Shahnameh in its various stories and episodes (Davis, Citation1992). A big proportion of these researches have been published in Persian. Due to the large bulk of these studies, it is not feasible to examine all of them here. For example, hundreds of articles and books have been published in Persian only in the domain of the relationship between religion and Shahnameh’s stories.

The third category includes studies that have concentrated on the political, identity-oriented, and nationalistic concepts of Shahnameh to explore the implications of the identity-based and political dimensions of this book and use them to shape Iranians’ identity at the present time (Ansari, Citation2012; Shahvari, Citation2018; Taheri, Citation1983). Some of these studies have made attempts to reconcile Islamist, justice-seeking, and leftist ideas in Shahnameh’s mythological stories and symbols (Baratlo, Citation2023; Mizani, Citation2009). Some other studies, done by ethnicity-oriented researchers, assert that Ferdowsi belongs to the Persian ethnicity and Shahnameh is full of ethnic traces since it is basically a book for Persian people and has capitalized on their myths. As such, Ferdowsi and Shahnameh are not able to play a role in reviving of the political and social identity of other ethnic groups (e.g. Kurds, Turks, Arabs, etc.) in Iran (Cabi, Citation2017; Vali, Citation1995).

The number of studies falling under the last category is limited. Nonetheless, as researchers have become more interested in the political and identity-based dimensions of Shahnameh and its importance for Iranians, researchers have begun to concentrate more on this line of inquiry. Moreover, the opposition of cultural-religious and ethnicity-oriented currents in the Islamic Republic of Iran with rationalistic and nationalistic (secular) analysis of Ferdowsi and Shahnameh has recently expanded the attention of studies on this field. As observed, a large bulk of studies on Ferdowsi and Shahnameh have focused on literary, cultural, artistic, and linguistic dimensions. This line of study is mainly pursued through running content analysis of Shahnameh’s text. On the other hand, the external impact of Shahnameh and the role of Ferdowsi and Shahnameh’s text in reviving the social and political identity of contemporary Iran, especially at the time of social media, have received scant attention. This mixed-methods study was an attempt to explore the impact of Shahnameh, as an independent variable, on Muslim and non-Muslim Iranians’ national identity.

These three categories of inquiry emerged based on the studies on Ferdowsi and Shahnameh. As a result of qualitative and conceptual analysis of these three categories, four conceptual approaches about Shahnameh were identified in Twitter.

These four approaches were detected through analyzing Twitter feeds posted from 2010 through 2022. In total, 150 feeds in Twitter were analyzed to identify these three general categories and conceptual signifiers.

As an unofficial medium, Twitter is highly popular among Iranians irrespective of their political orientations. Prominent international social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, are subject to blocking in Iran, but Iranians are able to access them through circumvention tools like virtual private networks (VPNs) and proxy services. The Iranian government has implemented these network blocks for security reasons and to exercise control over the dissemination of information, thereby mitigating the potential rise in political awareness among the population. However, it is important to note that Iranians continue to utilize these platforms, despite the restrictions in place. While official and accurate statistics regarding Twitter usage in Iran are unavailable due to the network being blocked, a significant number of Iranian authorities and citizens are active members of Twitter, particularly those with academic backgrounds who engage in discussions on various topics. Clear statistics on the number of Iranian internet users are not readily available. However, according to data from February 2022 provided by DataaK (Iranian Report Network on social media) and Iran Live Stats, approximately 80.6 percent of Iranians above the age of eighteen utilize social media platforms and messaging applications. Among these platforms, Telegram is particularly popular in Iran, boasting nearly 60 million accounts. Many individuals, including political figures, post content on Telegram, despite the platform being blocked. Twitter, with an estimated 4 to 3.5 million Iranian users, ranks third in terms of its popularity among Iranians. Following the protests in Iran in 2022, especially after the death of Mahsa Amini, there was an increase in activity on Persian Twitter, particularly among the younger generation. Many individuals, including political writers and critics, maintain anonymous pages on Twitter. This precaution is necessary because expressing views on political, cultural, economic, and social issues that oppose the government can result in severe consequences and significant personal risks, including the possibility of facing the death penalty. According to the available statistics, Iranian users generate an average of 233 tweets per second. These statistics suggest that approximately 52.4% of tweeters are male, 33.6% are female, and the remaining percentage consists of LGBTQ + individuals and others (Aftana security news agency, Citation2023; Iranlivestats, Citation2024).

It is important to acknowledge that these figures are not precise due to the nature of Twitter Farsi content. Given the significant focus on political issues in Iran, and considering the potential repercussions of criticizing the government, many pages on Twitter operate anonymously without disclosing the gender of the account holders.

Many educated Iranians use this platform. The collected posts for this study belonged to 50 non-fake users who came from Iran and had different political and religious (Muslim and non-Muslim) orientations ().

Table 1. The features the accounts and gender of Twitter users.

Summative method and conceptual analysis were utilized to identify the major lines of discourse about Ferdowsi and Shahnameh in the Twitter posts. In content analysis, summative method is typically used to examine the initial words and sentences with particular concepts and aims to gain a more extensive understanding of their use (Rapport, Citation2010). The frequency of these words and sentences sheds light on the intentions behind their use. One of the strengths of this method is that it is non-interventionist and non-reactive in examining the studied phenomenon. This feature made the method appropriate for the present research based on the goal of the study. The frequency data were generated using the application Numbers. The content analysis search of the tweets was carried out with the help of a Python computer program and based on the Tweepy library, which is provided to software developers by the API service of the Twitter website. The researcher feeds a keyword to this computer program, which in turn retrieves the tweets containing the keyword. The number of retrieved tweets depends on the length of time the program is run. The output is a file, known as Json, and contains information such as the content of the tweet and the user who has posted it.

Analyzing the 150 tweets yielded four main conceptual approaches, based on which major interpretive-hermeneutic elements among Iranians in relation to Shahnameh were classified. displays these conceptual approaches along with their descriptions and frequency percentage.

Table 2. Main conceptual elements (or features) in relation to Ferdowsi and Shahnameh in Persian Twitter.

It is observed that the first approach, which emphasizes the role of Shahnameh in reviving Iran’s national identity, has the highest frequency. The third and fourth approaches reflect the narratives offered by the opponents of national identity and Iranian-centered secular nationalism. These approaches demonstrate the shared viewpoint of Islamists and Islamist intellectuals, various left-wing groups, and ethnicity-oriented individuals. The current study aimed to explore the prevalence of these four approaches toward Ferdowsi and Shahnameh in social networks and examine the approach that non-Muslim and minority Iranians adopt to view Ferdowsi and its epic book. To this end, a general (non-specialized) closed-item questionnaire was distributed in Twitter among Iranian citizens with at least bachelor's degrees.

The participants included non-Muslim Iranians (including Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians, etc.), Sunni Muslims (as an ethnic minority in Iran), and Shia Iranians. The questionnaire aimed to assess the national role of Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh and its perception in the national non-religious identity of Iranians.

Research method

To evaluate the influence of Ferdowsi and Shahnameh in shaping the national and cultural identity of Iranians, a set of 10 focused closed-ended questions was formulated. These yes/no questions were designed in the form of a Twitter survey. A total number of 150 people who were active in Twitter were invited to answer the questions. Out of this number of participants, 50 were Muslims and 50 were non-Muslims. To enhance the validity of the research, the survey was distributed among a targeted sample of Iranian Twitter users with specific characteristics. The selection criteria included daily active users, popularity of their page, number of followers, and degree of influence within the Farsi Twitter community particularly engaging in political and social issues. The participants were chosen to represent a diverse range of ethnic, religious, and minority groups in Iran. Additionally, to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the perspectives, the survey included a background information section to collect data on participants’ religious identity, age, education, and gender. Participants were selected based on their active engagement on Twitter, the popularity of their page, the size of their followership, and their influence within the platform. The common feature of all the participants was their belief in Iran’s secular national identity.

Twitter was selected as the target platform since it has a profound impact on Iranians and political and social activists and a major role in shaping Iranians’ public and political opinions. Additionally, all leading political, cultural, and social activists have a notable presence in Twitter and their accounts have a large number of followers.

As previously mentioned, a considerable number of Twitter users in Iran choose to maintain anonymity, especially when discussing political matters. They often refrain from disclosing personal information such as gender and education. Consequently, in order to respect and accommodate their preferences, we have avoided requesting specific details regarding their educational background. This tendency to conceal one's identity is primarily attributed to the tight monitoring of social media platforms by cyber armies and security organizations associated with the Islamic Republic. If a user's identity is unveiled, punitive measures are enforced. Consequently, in order to encourage wider participation in our research, we have deliberately focused on users with a lower level of education, specifically targeting individuals with a bachelor's degree. This approach ensures a larger pool of potential respondents for our study, facilitating a comprehensive analysis of user perspectives. By adopting a more flexible approach to capturing data on education, we aim to encourage participation and ensure a broader representation of user perspectives in our research. So, we asked individuals with a bachelor's degree or higher education to participate in our questionnaire.

Chi-square test (X2) was used to analyze the collected data. This test explores if there is any significant difference between the expected and observed frequencies (Ott & Longnecker, Citation2015). The participants were meticulously chosen according to specific criteria in order to guarantee a diverse and representative sample. We sought out individuals who actively participated in discussions on sociopolitical matters on Farsi Twitter, encompassing individuals from various genders, ethnic backgrounds, and religious affiliations, including both Muslims and non-Muslims. Furthermore, we specifically targeted participants who exhibited a substantial influence on the platform, as evidenced by their extensive follower counts, high engagement levels (such as likes and retweets), and consistent daily tweeting activity. Being a minority, both in terms of religious affiliation and ethnic background, was a significant factor in our selection process. This deliberate choice was made to gain insights into how individuals with diverse perspectives perceive the role of Ferdowsi and Shahnameh in shaping Iran's national identity. In total, 150 people participated in this study, out of which 50 were Sunni and another 50 were non-Muslim Iranians (i.e. Jewish, Christian, Zoroastrian, etc.). In order to enhance the validity of the study, the survey was also distributed among 50 Iranian Shia Muslims.

In the Shia Muslim group, 28 participants were male and 22 were female or LGBTQ + . Considering the Sunni Muslim group, 24 were male and 26 were female or LGBTQ + . In the non-Muslim group, 25 were male and 25 were female or LGBTQ + . In terms of education, the respondents had bachelor’s, master’s, or PhD. Their responses to the survey items are displayed in the following table. The questions were closed and their responses would be yes or no. The frequency of these responses was the major focus of the study. Chi-square analysis was carried out to see if there was any significant difference between the three groups.

Each item as a question in the survey brings attention to the significant relationship between Ferdowsi, Shahnameh, and their role in shaping Iran's non-religious national identity. Through this online survey, participants were asked to provide their perspectives on how they perceive the positive role of Shahnameh in shaping Iran's secular national identity. The aim was to explore participants’ perceptions and understand how they perceive the connection between Shahnameh and Iran's non-religious national identity. In Iranian society, Ferdowsi and Shahnameh are widely recognized as representing an alternative, non-religious aspect of Iran's identity that stands apart from the Islamic identity espoused by the Islamic Republic. Their significance lies in their association with a cultural and national identity that transcends religious boundaries and offers a distinct perspective on Iran's historical and cultural heritage. As a literary and epic text, Shahnameh holds a vital position in evoking national sentiments and shaping the historical perception of cultural identity among Iranians. Its significance lies in its ability to resonate deeply with Iranians, connecting them to their rich heritage, traditions, and collective memory. Shahnameh serves as a powerful source of inspiration, fostering a sense of pride and attachment to Iran's cultural legacy. It provides a narrative framework through which Iranians can explore their historical roots and develop a stronger understanding of their cultural identity. By delving into the stories and characters within Shahnameh, Iranians are able to forge a stronger connection to their past, fostering a sense of continuity and belonging to their cultural heritage.

Data analysis and research findings

As indicated in , no significant differences were found among the three groups in terms of their responses to the questionnaire items (p > 0.05). This suggests that a portion of Iranians, regardless of their religious affiliation (Shia, Sunni, or non-Muslim), share a similar attitude towards Shahnameh. The positive attitude observed in this research can be extended to the research population, highlighting the influence of Ferdowsi on non-religious national identity perception among Shia and Sunni Muslims, as well as non-Muslims in Iran. This indicates that both Shia and Sunni Muslims, alongside the non-Muslim minority, share the belief that Ferdowsi plays a positive role in shaping the non-religious national identity among Iranians. However, it is important to note that these findings are specific to the research population and may not be generalizable to the entire Iranian population.

Table 3. Survey items and the difference between the three groups based on the results of Chi-square.

The results indicate that both Shia and Sunni Muslims, as well as non-Muslim minorities in Iran, share a common perspective on the role of Ferdowsi in shaping Iranians’ non-religious national identity. They collectively recognize his contribution to Iran's cultural and political identity, particularly in terms of cultural revival and national cohesion.

In addition to the Chi-square test, one-way ANOVA was used to further validate the findings. This test compares the mean scores between three or more groups to see if there is any significant difference between them. One-way ANOVA is a non-parametric test, with its null and alternative hypotheses being proposed in the following way:

H1: At least one of the mean scores is significantly different from the others.

Based on the objective of the current research, one-way ANOVA was used. The results are demonstrated in the following tables ().

Table 4. The features of the responding groups based on the mean score of their responses.

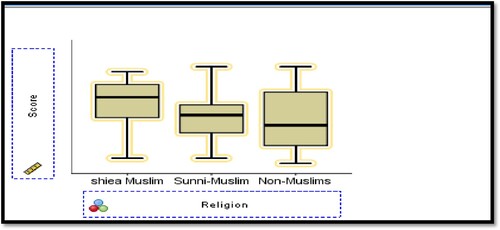

is the output of one-way ANOVA, which is the main table in this analysis. The p-value and the F columns indicate that the null hypothesis (i.e. lack of any significant difference in the mean scores of the three groups) is confirmed. The fact that the obtained p-value is smaller than 0.05 demonstrates that, despite slight differences in their mean scores, the three groups of respondents have the same opinion about Ferdowsi. Equality of variance can also be checked using Boxplot ().

Figure 2. Equality of variance in the participants’ responses to the survey items about Ferdowsi and Shahnameh

Table 5. The difference between the three groups.

Based on the figure above, it appears that there is no significant difference in the mean scores of the three groups. It is thus concluded that the three groups, including Shia and Sunni Muslims as well as non-religious minorities, share the same perception about Ferdowsi and his role in reviving Iranians’ non-religious national identity.

According to this finding, Ferdowsi has a critical role in the development of nationalistic non-religious identity among Iranian minorities and their integration with Iran’s national identity. This has a vital role in the revival of non-religious and national secular identity in the presence of the Islamic Republic. The revival of the national non-religious identity in Iran consolidates the main part of the nationalistic discourse against political Islam, which is supported by the authorities and their followers, especially Islamists who assert that Iranians’ national identity is a western and non-Islamic enterprise. To get closer to Shia and Sunni Islamists in other countries of the Islamic world, these people question the national secular and citizen-oriented identity of Iran, fight against its supporters, and typically place them in jail. The obtained data indicate the importance of the new secular identity movement in a country where the government runs the country based on the teachings of political Islam. This movement has become stronger as a result of the spread of social media. Recent social movements in Iran (e.g. the women, life, freedom movement) are also connected to the national secular identity of Iran, which frequently resorts to Ferdowsi and Shahnameh. Borrowing concepts from Shahnameh to describe the challenging campaign of Iranian female and male youth against the Islamic regime and political Islam to achieve freedom are major constructs depicting future democratic and secular Iran.

This paper does not aim to provide a statistically representative perspective of the entire Iranian population's views on Ferdowsi's role in Iran's national identity. Instead, it focuses on gaining insights from a specific group of influential Farsi Twitter users who represent the politically active population in Iran. These users hold positive views regarding Ferdowsi's significance in shaping the national identity. While caution is needed in generalizing these findings to the entire Iranian population, the perspectives of these influential Twitter users shed light on Ferdowsi's enduring impact within the context of Iran's national identity.

Conclusion

It is observed that Ferdowsi’ Shahnameh has a critical role in expanding non-religious ties of national identity in Iran among minorities. The results also showed that many Iranians perceive their national secular identity through Shahnameh. Ferdowsi and its major book, Shahnameh, can be regarded as the central core of the national identity of secular Iranians and the central point of consensus on the formation of a non-religious historical revival of national identity in Iran. Some researchers of Iranian studies believe that religion, especially Shiism, has exerted a great effect on re-rise of Iranians’ national identity (Ahmadi, Citation2005; Ashraf, Citation1993; Boroujerdi, Citation1996, Citation1998; Farhi, Citation2005; Saleh, Citation2013; Saleh & Worrall, Citation2015; Shayegan, Citation1992; Vaziri, Citation1993). They claim that, since the establishment of the Safavid dynasty, Shiism has had a significant role in Iran’s territorial integrity and the expansion of national identity structures. The importance of Shahnameh as a text consolidating national unity among Muslim and non-Muslim Iranians can question this meta-narrative. Many non-Muslim and Sunni Iranians do not agree with the claim made by some researchers and thinkers that religion in general and Shiism in particular are factors unifying Iranians’ national identity. Thus, it is argued that the foundation of the modern national identity in Iran is secular and Shahnameh and Ferdowsi’s character can be regarded as a unifying and historical construct for this new foundation. They can replace Shiism and its historical and belief-oriented statements among Iranians. In fact, Shiism is the foundation of the construction of political Islam used by the Islamic Republic to oppress dissent. As a pluralistic text, Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh unifies Iran’s national secular identity discourse. In contrast to Shiism, it accommodates the ideas of both Muslim and non-Muslim Iranians. In addition, Shahnameh and Ferdowsi’s character can encompass the meta current of Iran as a widespread geography. In the national secular identity revived by Shahnameh, it is highly likely that the citizens of Panjshir in Afghanistan, Balkh, Badakhshan, Dushanbe, and Smarkand can also share the same identity with Iranians. It is probably easier for the citizens of these cities to reach consensus with Iranians regarding the common themes extracted from Shahnameh. The expansion of the idea of Iran as a connectionist political geography will depend on the expansion of the idea of a secular national identity based on Iranian culture and historical and discursive objects, including Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh. The major force behind today’s libertarian political movements in Iran, especially women’s movement, is the expansion of libertarian and democratic analyses of Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh as opposed to the concepts of political Islam. As such, religion plays an insignificant role in perceiving identity symbols in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh. Non-Muslim Iranians, including Baha’is and Zoroastrians, as well as Sunni Iranians (all of whom are minorities in Iran) share a common perception of Shahnameh’s identity sources and its role in consolidating a national secular identity in Iran.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Arash Beidollahkhani

Arash Beidollahkhani holds a PhD in Political Science and is a research fellow at the Global Development Institute in the School of Environment, Education, and Development at the University of Manchester. His research focuses on broader interdisciplinarity interests with an emphasis on Middle Eastern politics and history, as well as the political sociology of non-democratic and authoritarian regimes in the Middle East and Central Asia.

References

- Ahmadi, H. (2005). Unity within diversity: Foundations and dynamics of national identity in Iran. Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies, 14(1), 127–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/10669920500057229

- Aftana cyber security news agency. (2023). Social Network Usage Among Iranians: Insights from DataaK's Statistical Report since 2022. Retrieved June 8, 2023, from https://aftana.ir/vdciy3ar.t1auz2bcct.html.

- Ansari, A. M. (2012). The politics of nationalism in modern Iran (Vol. 40). Cambridge University Press.

- Ashraf, A. (1993). The crisis of national and ethnic identities in contemporary Iran. Iranian Studies, 26(1–2), 159–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/00210869308701795

- Amanat, A. (2012). Introduction: Iranian identity boundaries a historical overview. In A. Amanat, & F. Vejdani (Eds.), Iran facing others: Identity boundaries in a historical perspective (pp. 1–33). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137013408_1

- Bader, V. (2001). Culture and identity: Contesting constructivism. Ethnicities, 1(2), 251–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879680100100206

- Baratlo, F. (2023). An introduction to division of labor in social classes as a representation of justice in Ferdowsi’s Shahnama. Classical Persian Literature, 13(2). https://doi.org/10.30465/cpl.2023.7383

- Beeman, W. O. (2000). Ferdowsi and Tajik National Identity. Ferdowsi in the Realms of Culture and History. Centre for the Great Islamic Encyclopedia. Tehran.

- Beidollahkhani, A. (2022). From a radical-religious movement to a democratic social sub-movement. International Journal on Minority and Group Rights, 29(5), 929–952. doi:10.1163/15718115-bja10079

- Bell, D. S. (2003). Mythscapes: Memory, mythology, and national identity. The British Journal of Sociology, 54(1), 63–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/0007131032000045905

- Boroujerdi, M. (1996). Iranian intellectuals and the west. Syracuse University Press.

- Boroujerdi, M. (1998). Contesting nationalist constructions of Iranian identity. Critique: Journal for Critical Studies of the Middle East, 7(12), 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10669929808720120

- Cabi, M. (2017). Clash of national narratives and the marginalization of kurdish-Iranian history. Contemporary Review of the Middle East, 4(4), 335–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/2347798917727894

- Clark, F. (2010). From epic to romance, via filicide? Rustam's character formation. Iranian Studies, 43(1), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/00210860903451212

- Cross, C. (2015). “If death is just, what is injustice?” Illicit rage in “Rostam and Sohrab” and “The Knight's Tale”. Iranian Studies, 48(3), 395–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/00210862.2014.1000620

- Dabiri, G. (2010). The Shahnama: Between the Samanids and the Ghaznavids. Iranian Studies, 43(1), 13–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00210860903451196

- Davis, D. (2015). Religion in the Shahnameh. Iranian Studies, 48(3), 337–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/00210862.2014.1000621

- Davis, D. (1992). Epic and sedition. The case of Ferdowsi’s Shāhnāmeh.University of Arkansas Press.

- Farhi, F. (2005). Crafting a national identity amidst contentious politics in contemporary Iran. Iranian Studies, 38(1), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/0021086042000336519

- Farhat-Holzman, L. (2001). The Shahnameh of Ferdowsi: An icon to national identity. Comparative Civilizations Review, 44(44), 6.

- Figueira, D. M. (2002). Aryans, Jews, Brahmins: Theorizing authority through myths of identity. Suny Press.

- Gabbay, A. (2023). “The earth my throne, The heavens my crown”: Siyāvash as supranational hero in Ferdowsi’s Shāh-nāma. Journal of Persianate Studies, 1(aop), 1–17.

- Gabri, R. (2015). Framing the unframable in Ferdowsi's Shahnameh. Iranian Studies, 48(3), 423–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/00210862.2014.1000623

- Gholami, R. (2015). Secularism and identity: Non-Islamiosity in the Iranian diaspora (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315608020

- Hariri, N. (2018). Ferdowsi, Zan va Teragedi. Avishan publication.

- Hayes, E. (2015). The death of kings: Group identity and the tragedy of Nezhād in Ferdowsi's Shahnameh. Iranian Studies, 48(3), 369–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/00210862.2014.1000625

- Iran live stats. (2024). Current statistics of Iran's virtual space. Retrieved January 11, 2024, from http://iranlivestats.ir/.

- Mahallati, M. (2015). Ethics of War and peace in the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi. Iranian Studies, 48(6), 905–931. https://doi.org/10.1080/00210862.2014.920663

- Miller, D. L. (2014). Mything the study of myth. Jung Journal, 8(4), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/19342039.2014.956379

- Mizani, F. (2009). Hamaseye DaaD; Bahsi dar Mohtavaye Siasi Shahnamehee Ferdowsi. Tudeh Party of Iran.

- Mousavi, S. M. (2019). Canonizing Shahnameh in early modern Iran: A historical-semiotic approach [In English]. Journal of Language Teaching ‘Literature & Linguistics (JLTLL)’, 2(1), 183–200.

- Ott, R. L., & Longnecker, M. T. (2015). An introduction to statistical methods and data analysis. Cengage Learning.

- Kubálková, V., Onuf, N., & Kowert, P. (2015). Constructing constructivism. In V. Kubálková (Ed.), International Relations in a Constructed World (1st ed., pp. 3–22). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315703299

- Pierce, L. (2015). Serpents and sorcery: Humanity, gender, and the demonic in Ferdowsi's Shahnameh. Iranian Studies, 48(3), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/00210862.2014.1000629

- Pfadenhauer, M., & Knoblauch, H. (Eds.). (2018). Social constructivism as paradigm?: The legacy of the social construction of reality (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429467714

- Rapport, F. (2010). Summative analysis: A qualitative method for social science and health research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 9(3), 270–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691000900303

- Rezaei, M. (2016). Shokoohe Kherad dar Shahnameh Ferdowsi. Elmi Farhanig pub.

- Sadeghi, A. (2004). Hero and heroism in the Shahnameh and the Masnavi. Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies, 13(2), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/1066992042000244326

- Saleh, A., & Worrall, J. (2015). Between Darius and Khomeini: Exploring Iran's national identity problematique. National Identities, 17(1), 73–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/14608944.2014.930426

- Saleh, A. (2013). Iran’s national identity problem. In Ethnic identity and the state in Iran. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137310873_4

- Sataravala, S. (2023). Parsi identity: Myth and collective memories. South Asia Research, 43(1), 34–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/02627280221120336

- Sethi, R. (1999). Myths of the nation: national identity and literary representation.Oxford university press.

- Shahvari, Ahmad. (2018) Ferdowsi, Shahnameh va Irangarayi. Shahvari publication.

- Shayegan, D. (1992). Cultural Schizophrenia: Islamic societies confronting the west. Saqi Books.

- Skupniewicz, P., & Maksymiuk, K. (2019). Gordāfarid, Penthesilea and Athena: The identification of a Greek motif in Ferdowsī’s Šāh-nāma and its possible association with Hellenistic art in the east. Mediterranean Historical Review, 34(2), 123–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518967.2019.1663651

- Taheri, A. (1983). The Islamic attack on Iranian culture. Index on Censorship, 12(3), 24–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/03064228308533535

- Thio, A. (2007). Society: Myths and realities: An introduction to sociology. Pearson/Allyn and Bacon.

- Vali, A. (1995). The making of Kurdish identity in Iran. Critique: Journal for Critical Studies of the Middle East, 4(7), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10669929508720071

- Vaziri, M. (1993). Iran as imagined nation. Paragon House.

- Yaghooti, M. (2018). Ferdowsi, Ostore va Realism. Negima publication.

- Yarshater, E. (1993). Persian identity in historical perspective. Iranian Studies, 26(1–2), 141–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/00210869308701791

- Zene, C. (2007). Myth, identity and belonging: The Rishi of Bengal/Bangladesh. Religion, 37(4), 257–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.religion.2007.10.002