ABSTRACT

In Finland, teachers’ have extensive autonomy, that is freedom from control by others over their professional actions in the classroom, and it is considered a strength of Finnish education. At the same time, national assessment of learning outcomes has been constructed to examine the learner's progress and achievements in relation to the criteria of the Finnish National Core Curriculum for Basic Education in effect at the time. The national assessment of learning outcomes in music was conducted for the first time in 2011. In this article, the implementation and the main results of this National Assessment of Learning Outcomes in Music, in the ninth-grade of Finnish Basic Education are explored, and the whole process is examined critically from the perspective of teacher autonomy. The article discusses how, in the assessment, the ideals of teacher autonomy challenged assignment construction and the findings and conclusions of the national assessment. The article concludes that both teacher autonomy and national assessment are essential to compulsory education but must be balanced in a meaningful way.

Introduction

In today's data-driven educational climate, there is a need to demonstrate that learning is, in fact, taking place (Fisher Citation2008). Accordingly, education is performance driven and demonstrates its effectiveness by results. Assessment and evaluation have become forefront in education, and the quality assurance systems play a big role in educators’ daily life. The era of accountability, in the spirit of the neo-liberalFootnote1 schooling of the twenty-first century, has marked a transition from local control to increased state influence and direction in educational policy (especially in Great Britain and the USA). As a result, student outcomes are widely determined by standardised testing, and schools are judged effective by observable outcomes.

Assessment of learning, as part of wider evaluation systems, takes place on the local, national, and even international level. For example, in compulsory education the PISAFootnote2 exams have measured the outcomes of learning in mathematics, science, and reading on an international level since 2000. The published PISA ranking lists countries based on their pupils’ success in these exams, which in turn has led to educational discussions, actions and/or changes on a national level, regarding, for example, the amount of lesson hours devoted to each subject and core curricula. In almost all European countries, pupils are required to take a standardised national test at least once, at the primary or lower secondary level of education, and test scores are often regarded as defining school effectiveness.

However, in most cases, art subjects are not included in these exams. Exceptions are Ireland and Scotland, where national exams are offered for those pupils who have chosen optional studies in the art subjects, and Malta, where national exams are offered yearly in visual art (limited to drawing and painting) for pupils at the lower secondary level. In fact, it is only in Greece, Ireland, and Great Britain where the quality of teaching in art subjects is reported based on the work of inspectors or school boards (Arts and Cultural Education at School in Europe Citation2009, 60–62).

Also, very few national assessments have been carried out in the arts and crafts disciplines, and there are no assessments comparable to the international PISA studies. The national assessments that have been carried out vary in their objectives. In Sweden, two national assessments of the subjects of music and the visual arts have been conducted, whose focus has been on issues pertaining to teaching. These assessments have not generated information of learning results, but rather, for example, of teaching practices and the perspectives and objectives of the teachers and pupils in studying the visual arts and music (Marner, Örtegren and Segerholm Citation2004, 109; Sandberg, Heiling and Modin Citation2005, 22–23).

In the USA, where accountability is addressed both state and national level (Anderson Citation2010), a comprehensive national assessment on the artistic disciplines has been conducted in 1997 and 2008. Music was first assessed in 1972 and visual arts in 1975. The 2008 NAEP (National Assessment of Educational Progress) arts assessment measured the extent of what American students know and can do in the arts disciplines of music and visual arts by asking them to observe, describe, analyse, and evaluate existing works of music and visual art and to create original works of visual art (NAEP Citation2008). The assessment was administered at grade 8 only. The NAEP has been criticised for its small sample size, and for not assessing ‘student achievement in either performing or creating music, two areas central to the National Standards and to music curricula across the United States’ (Shuler et al. Citation2009, 12).

In Finland, where accountability cannot be found in educational policy discourse (Sahlberg Citation2011, 125), a national assessment of learning outcomes in the arts and crafts disciplines was conducted for the first time in 2011 (see Laitinen, Hilmola, and Juntunen Citation2011).Footnote3 Unlike in some other countries, the national assessment of learning outcomes in any subject is not regarded as a tool to control education but rather to improve it (Kumpulainen and Lankinen Citation2012; Niemi Citation2013). It can be considered a curriculum evaluation exercise that primarily informs curriculum development and reform. It is used as a diagnostic tool, and has no implications for individual teachers (Vitikka, Krogfors and Hurmenrinta Citation2012). Furthermore, the assessment of learning outcomes is not necessarily considered an issue of quality of teaching, which is defined instead through the mutual interaction between the school and the students, together with their parents (Sahlberg Citation2011, 92).

In the current article, the implementation and main results of the National Assessment of Learning Outcomes in Music in the ninth-grade of Finnish Basic Education are explored (see Juntunen Citation2011), and the whole process is critically examined from the perspective of teacher autonomy. The article discusses how, in the assessment, the ideals of teacher autonomy challenged assignment construction and even disputed the findings and conclusions of the national assessment. These issues lead to question the assessment roles and challenges for school music education, suggesting that we need to carefully and critically reflect on the conclusions of the national evaluation. In addition, this article highlights the relationship between the understanding of learning outcomes and assessment strategies, as defined by policy-makers, national evaluators, and measurements of music teaching successes.

Teacher autonomy

Studies directly pertaining to teacher autonomy are few in number. Attempts at identifying the underlying theoretical dimensions of teacher autonomy itself have met with varied results, and it has been a challenge to develop appropriate measures of autonomy, since the concept is difficult to operationalise (Pearson and Moomaw Citation2005). In this article, teacher autonomy refers to teachers’ freedom from the control by others of their professional actions, having extensive autonomy in the classroom (Helgøy and Homme Citation2007; Niemi Citation2013) rather than the capacity to self-direct one's own professional development (Hacker and Barkhuizen Citation2008). It particularly refers to teachers’ freedom and responsibility to make choices regarding content and ‘methods’ of teaching.

Teacher autonomy is often considered to have a positive influence on education. For example, there is evidence that psychological factors such as career motivation, self-efficacy, teacher autonomy and perceived control, and teachers’ sense making all affect teachers’ learning and improve their teaching (Thoonen et al. Citation2011). The study of Pearson and Moomaw (Citation2005) examined the relationship between teacher autonomy and stress, work satisfaction, empowerment, and professionalism. In their study, it was found that as curriculum autonomy increased, on-the-job stress decreased, and that teacher autonomy necessarily related to the quality of empowerment and professionalism. In addition, as job satisfaction, perceived empowerment, and professionalism increased, on-the-job stress decreased, and greater job satisfaction was associated with a high degree of professionalism and empowerment. The results of the study also indicated that the effects of autonomy do not differ across teaching levels (primary, lower/upper secondary school). Kallio (Citation2015) has studied the autonomous processes of Finnish music teachers when choosing teaching materials, in particular when selecting music from the popular repertoire. Her study illustrates the complex, situational, and multifaceted negotiations involved in including or excluding popular repertoire from school activities.

Teacher autonomy and equity of education – cornerstones of Finnish education

In recent years, Finnish education has gained international attention, primarily because of its consistently high ranking in the PISA exams. The quality of Finnish education is believed to rest on, to a large degree, the principles of teacher autonomy and equity of education (Niemi, Toom and Kallioniemi Citation2012). In addition to high-quality teacher preparation, educating teachers as autonomous professionals is considered a main principle and goal of Finnish teacher education (Sahlberg Citation2011; Tirri Citation2012; Niemi Citation2013). Teachers have a high degree of pedagogical and professional freedom and opportunities, but also correspondingly great responsibility to influence their work and the development of their schools (Sahlberg Citation2011; Toom and Husu Citation2012). They participate in the administrative and pedagogical decision-making processes on the local level, but they are also included in the creation of the Core Curricula on the national level (Niemi Citation2013).

But how much freedom do Finnish teachers have? The Finnish National Core CurriculumFootnote4 for Basic Education aims to unify basic education and to make it comprehensive. It defines the basic value and role of education, the objectives and core content of teaching, the conception of learning, and the general guidelines for course structure, syllabus content, and assessment (see more, Vitikka, Krogfors, and Hurmerinta Citation2012). On the basis of these guidelines, the education providers, usually the local education authorities and the schools themselves, draw up their own curricula within the framework of the national core curriculum. Schools and teachers are trusted to follow the core-curriculum guidelines, expected to formulate their own curricula, and are free to determine the specific content taught within this framework. Teachers also have the freedom to decide what kinds of assessment methods they use in order to support student learning. Teachers are not evaluated through external or formal measures, and quality assurance is largely in the hands of school principals, who work together with the teachers in developing curricula and professional-development initiatives.

In addition to teacher autonomy, another fundamental quality criterion for education in Finland is the aspiration towards equality in education (Kumpulainen and Lankinen Citation2012). The goal is to ensure high-quality education, support, and guidance free of charge for all children and youths, no matter what their place of residence or social background. Systematic evaluation and assessment work has an important role in ensuring the realisation of this educational equity. For this purpose, the Finnish National Board of Education has developed a national system for assessing learning outcomes, published in 1998 (Jakku-Sihvonen and Heinonen Citation2001; FNBE Citation1999). One part of this system comprises the assessment of the learning results of basic education, which examines the learner's progress and achievements in relation to the criteria of the basic education curriculum in effect at the time (see more, Kumpulainen and Lankinen Citation2012).

Objectives of the arts and crafts follow-up assessment

The purpose of the assessment implemented in Finland was to obtain a reliable overall picture of the realisation of and level of competence in the objectives for music, visual arts, and handicrafts during the final stage of basic education (Laitinen, Hilmola, and Juntunen Citation2011). The results of the assessment were used to monitor the implementation of education-related equality, and feedback information was also given to the schools for the development of instructional methods. The goal of the assessment was to determine how the objectives defined in the criteria (FNCC Citation2004) of the curriculum with regard to music, the visual arts, and handicrafts had been accomplished in the final, ninth-grade of basic education.

The author of this article was responsible for conducting the assessment in music. This task was problematic from the very beginning: in music, teachers have even more autonomy than in some other subjects, since the core curriculum of music (FNCC Citation2004, 230–232) is very open. The core content of musical instruction includes voice control, skills in playing a musical instrument in a group, versatile musical production and listening repertoire, and experimentation with musical ideas. The goals of music teaching are to ‘help the pupils find their objects of interest in music, to encourage them to engage in musical activity, to give them means of expressing themselves musically, and to support their overall growth’ (229), as well as to help them to understand that music is different at different times, and in different cultures and societies, and has a different meaning for different people. The more specific learning objects for the grades 5–9 are defined as following (FNCC Citation2004, 231):

The pupils will

maintain and improve their abilities in different areas of musical expression, acting as members of a music-making group

learn to examine and evaluate various sounds environments critically, and to broaden and deepen their knowledge of different genres and styles of music

learn to understand the task of music's elements – rhythm, melody, harmony, dynamics, tonal colour, and form – in the formulation of music, and to use the concepts and notations that express these elements

build their creative relationships with music and its expressive possibilities, by means of composing.

In accordance with these broad objectives, teachers can formulate their more specific goals, use the methods they want, choose the kinds of music they teach; and when designing teaching content and teaching material, they may use textbooks offered by various publishers and/or prepare their own materials. In addition, in music there is very little student testing, and teaching is not geared to meet any standardised requirements.

Implementation of the national assessment in music

Selection of schools and pupils

A total of 4792 pupils (age 15–16) participated in the assessment. The assessment was organised on a sampling basis. When selecting the sample, care was taken to include all regional and municipal types on a statistically proportional basis. Likewise, the target population (all schools and their pupils providing ninth-year instruction) was divided into sections in accordance with regional factors. In this respect, various types of schools were selected from each province in order to represent the full range of school types. This procedure ensured that the sample reliably represented all schools and pupils. On average, approximately one-fifth of those schools where ninth-year instruction was given were included in the sample. Of the Swedish-language schools,Footnote5 12 were included in the sample, which is slightly more than the relative share of the schools providing ninth-year instruction. The selection of the sample pupils was not affected by whether or not the pupil had studied music, visual arts or handicrafts as an optional subject at school, as the goal of the assessment was to measure overall achievement in these fields as opposed to the achievement of students specifically enrolled in arts classes.Footnote6

Assessment structure

The assessment was completed in three stages (). From the perspective of music, the first challenge of the assessment process was that the structure and the tasks had to be in accordance with assessment practices of the Finnish National Board of Education implying pencil-and-paper assignments in two stages. Yet, very few musical skills can be tested through pencil-and-paper tests (see Gordon Citation1999). Thus, it was obvious that pencil-and-paper tasks were particularly problematic for assessing learning outcomes in music.

Table 1. Assessment structure in music subject.

During the first stage, all sample pupils (N = 4792) received a task notebook in which the pencil-and-paper tasks of all three school subjects were comprised. During the second and third stages, the schools (N = 152) were divided into three groups: in one-third of the schools, the sample pupils (N = 1609) performed the tasks of music. The second stage tasks were advanced pencil-and-paper assignments. Deviating from the practice of the assessment of learning outcomes based on other school subjects, the assessment of the art and handicraft subjects contained a further third stage in which the production of skills were assessed. During the third stage of assessment in music subject, 12 pupils (6 boys and 6 girls as a rule) from 50 schools (total: 589 pupils) performed a production task in which the pupils played instruments and sang as well as composed and presented a small piece. Pupils’ self-assessment was also attached to the production tasks.

In addition to the assessment tasks, the pupils responded to the questionnaires in which their study backgrounds, attitudes towards musical studies and concepts of themselves as musical learners, as well as the pupils’ perspectives on the significance of music studies on the personal level were surveyed. The assessment also included questionnaires for principals and teachers, addressing teaching arrangements and learning opportunities and barriers. In this article, only the tasks and results of assessing the learning outcomes in music are reported.

Preparation of assessment tasks

The second challenge in the process of assessing the learning outcomes in music was the preparation of assessment tasks that took place in a specialist group of five music lecturers from universities and schools. The tasks were intended to be prepared on the basis of the objectives of music subject presented in the Basic Education Curriculum (FNCC Citation2004). Yet, because of teacher autonomy and openness of the music curriculum, there was hardly any data available concerning what pupils are actually taught, how they are taught, and what they learn in school music lessons.

I will explain the challenges of task preparation more in detail: In the curriculum, the content of music teaching is specified on an operational basis. The general knowledge-based content areas that are possible to target with pencil-and-paper tasks have been specified only on a very general level. This means that in practice the content of teaching may vary considerably from school to school. Thus, uniform familiarity with the specific content of music with regard to the entire age class could not be assumed to even exist. This being the case, it was not possible to formulate to assessment tasks only based on curriculum, and hence the criteria in the preparation of the tasks were the content of the textbooks as well as the experience of the specialist group teacher members of what is taught during the music lessons at school. General knowledge of what is actually taught in various schools was also unavailable. The content area distribution (see below) used in this assessment was prepared for this assessment. The preparation of musical production tasks (third stage) was easier and more meaningful since the music curriculum defines the criteria for the grade 8 (in the scale of 4–10) for assessing the basic skills in singing, playing and playing and performing in a group.

The tasks of each school subject were subjected to trial in schools in November and December 2009 in various parts of Finland. After the pre-experimentation of the tasks, the specialist group selected, on the basis of the analysis results, the tasks to be used in the final test and their assessment instructions.

Assessment tasks and procedure

All assessment stages were conducted at all the schools in March 2010 during one and the same week. The assessment tasks in the first and second stage, comprising pencil-and-paper tasks were multiple choice, combination, short answer or open question-type tasks.Footnote7 Of the open tasks, some were writing assignments. Listening samples were also included in the musical tasks. All tasks were scored in accordance with the instructions.

The pencil-and-paper tasks used in the assessment were divided into the following content areas: (1) musical knowledge and cultural competence, divided into (a) musical knowledge in listening tasks, (b) familiarity with works, styles and composers, and (c) other musical knowledge, (2) competence related to musical activities, (3) relationship to music,Footnote8 and (4) music ‘civics’ (hearing protection and copyright). In some assessments tasks, there was an attempt to assess the pupil's ability in several content areas at the same time. Examples of the pencil-and-paper tasks are presented in Appendix.

The tasks varied in level of difficulty, including easy, moderately difficult, and difficult tasks. Certain tasks assessed areas of learning already contained in the teaching in the lower classes whereas in some other tasks, the level of difficulty was set to that of required in order to achieve a good mastery at the final stage of basic education. In tasks concerning the pupil's personal relationship with music, the pupil had the possibility to provide many kinds of answers arising from his/her experiences, which were scored in accordance with the pupils’ rationales and versatility as applied.

At the third stage of the assessment, production, work process and self-assessment skills were assessed in the production tasks. In this article, the results concerning music production skills only are presented. Three separate tasks were included in the production tasks. The first was a song task where the pupils’ ability to sing in a rhythmically correct way and in accordance with a melody line was assessed. Instrumental skills were assessed in a task where pupils played instrument in an ensemble (percussion/drums, chordal instruments: guitar, kantele and/or keyboards) and sang in varying set-ups. It was also possible to use a bass guitar and a melodic instrument. The teacher had chosen the pieces to be sung and played either from the alternatives selected by the musical specialist group or, under certain conditions, freely. The first two tasks were presented under the teacher's supervision. In the third task, the pupils produced and then performed their own piece in a group of 3–5 pupils.Footnote9 In the task, musical inventiveness was assessed. On the basis of the tasks described above, the teacher also assessed the pupil's ability to participate in ensemble performance as well as his/her skills in understanding musical notation (chord and repetition symbols, etc.) and applying concepts. The time reserved for the entire production task realisation was approximately 90 minutes. The production tasks were videoed. The teacher performed the assessment either during the task or after it, assisted by video if she/he preferred. The relation between the assessment structure and the final-assessment criteria for a grade of 8 as defined in the Core Curriculum (FNCC Citation2004) is presented in . (Since during the assessment process it became evident that it was impossible for teachers to assess students’ ability to use concepts in music making, this assessment criteria was dropped in production tasks.)

Table 2. Final-assessment criteria for a grade of 8 as defined in the Core Curriculum (FNCC Citation2004) in relation to the National assessment structure.

Assessment validity and reliability

When considering the assessment validity and reliability, the following aspects should be considered. To ensure conformity with the assessment, the assessment instructions were detailed. An assessment-based auxiliary form was prepared as well as the assessment criteria for the teachers: a description of each rating (4–10) corresponding to competence for each target area of assessment. The assessment material produced at the schools was coded and analysed at the Finnish National Board of Education. The materials were inspected during the summer of 2010. The musical production tasks (video recordings) were re-assessed by experienced music teachers and teacher trainers during the summer of 2010.Footnote10

When assessing the reliability of the assessment it should be noted that 62% of the participating pupils had not studied music after the seventh grade (during the previous two years) and had likely forgotten a lot. In the assessment situation pupils had limited time to practice singing and playing. Moreover, teachers interpreted assessment instructions differently: in the assessment situation some teachers taught their pupils how to play while others left their pupils without any guidance.

The assessment reliability relates to assessment tools’ capability to produce data that is not random. Cronbach's alpha (∂) was used to estimate the internal uniformity of the assessment tasks. The ∂-correlation was 0.81 in paper-and-pencil tasks and 0.92 in production tasks, and can be considered good results.

Results

General level of competence

The pupils received, on average, 57% (girls 58%, boys 55%) of the maximum number of points for all intended sample pupils (N = 4792) with regard to the music-based general task series (first stage). The pupils selected only for the music sample (N = 1609) received, on average, 56% (girls 60%, boys 52%) of the maximum number of points respective to the advanced music task series (second stage). The pupils responding to both the combined and advanced musical task series received, on average, 56% (girls 59%, boys 53%) of the maximum number of points. In addition, the pupils (N = 589) selected to complete the music production task (third stage) received, on average, 58% (school rating 7.5 in the scale of 4–10) of the maximum number of production task points,Footnote11 with girls 62% (school rating 7.8) and boys 53% (school rating 7.2) ().

Table 3. Averages and dispersions of tasks’ solution shares as relative shares of the total number of points.

Results of pencil-and-paper tasks

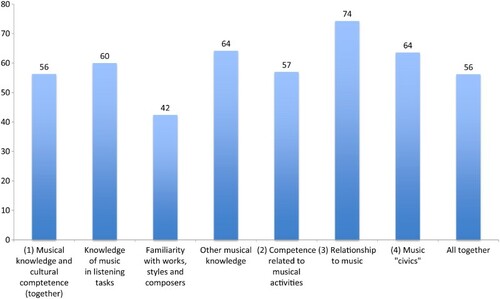

The pupils’ results in the various content areas of the pencil-and-paper tasks are presented in . In the results, those pupils’ responses that replied to both the combined and music-based advanced notebook tasks (N = 1607) are taken into account. These results are nevertheless merely indicative.

Figure 1. The pupils’ results in the pencil-and-paper tasks according to content area. The percentages of correct solutions are presented in the figure for each content area.

A total of 2% of the pupils achieved excellent results. Poor performances were conversely noted with 9% of the pupils.Footnote12 The pupils’ competence varied a lot with regard to the task. The pupils’ answers split into the content area of the music relationship (dispersion 24.38) more than other content areas (dispersion in all content areas on average 12.13). It was necessary to answer these questions in the form of open responses. The tasks required the skill to verbalise musical experience or significances connected with music. For this, the pupils clearly had varying readiness and possibly varying willingness as well.

Results of production tasks

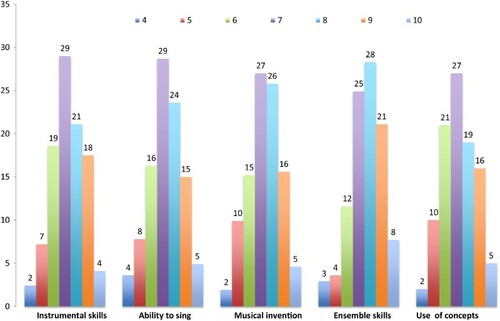

The teachers assessed the pupils’ production tasks with school ratings. The result of the assessment among all sample pupils (N = 589) was an average rating of 7.5, which, converted to the solution share, corresponded to a share of 58% of the production task-related maximum score. The dispersion of ratings was 1.1 units. The distribution of the production task results is presented in . A total of 12% of the pupils achieved excellent results. Poor performance was identified in 16% of the pupils.

Figure 2. The pupils’ results of music production tasks. The percentages of each grade (4–10) given by teachers for each competence area are presented in the figure.

Examined on average, the competence of the pupils in various areas was even. The strongest skills were assessed in participation in performing music in a group (ensemble skills), where the average rating was 7.7. The pupils’ instrumental skills, ability to sing, and musical inventiveness were assessed with an individual rating of 7.3 on average. The teachers assessed as poorest the skills of understanding and using concepts (7.2).

The production task and the areas of learning assessed in it, such as singing, playing instruments, musical invention, and performing music in a group (ensemble skills), represent the most pivotal content of the music curriculum in Finnish basic education. This task can be regarded as the most essential stage of the assessment from the perspective of the curriculum. The drawback was that the sample in the third stage was not big enough for statistically significant results.

Observations and discussion

With respect to the specified objectives in the Finnish National Core Curriculum for Basic Education (FNCC Citation2004), the general level of musical competence in the ninth year of comprehensive school is, according to the results of this assessment, only moderate. Only the girls attained satisfactory results in the production tasks.Footnote13 In the results, there were some differences between various parts of the country, types of municipalities and language groups. For example, pupils at the Finnish-language schools succeeded better than the pupils at Swedish-language schools. Also recent assessment studies in other subjects have revealed growing differences in learning outcomes between genders, regions and population groups (Kumpulainen and Lankinen Citation2012, 77). In this light, the overall goal of equality in education does not seem to have materialised in an inclusive manner.

According to this assessment research study, the pupils leave basic education in Finland with rather varying knowledge and levels of skills in music. The pupils’ competence varied to a surprising extent with regard to the task, and a few tasks presumed to be rather easy were surprisingly difficult for the pupils. The percentage of correct solutions in the weakest content area (work-, style- and composer-related knowledge) was only 42. Yet, this was not surprising considering that teacher autonomy (and the slackness of the core curriculum of music) allows very many types of musical content solutions. Familiarity with uniform musical content from these starting points cannot even be assumed to exist. For the same reasons, this may be seen as deriving from the fact that in one task a pupil who has shown good competence has not necessarily risen to equally good results in another task.

Assessment can be defined as the comparison of the relationship between set objectives and achieved results (Jakku-Sihvonen and Heinonen Citation2001). The information gathered from national evaluations is intended to be used in the development of education and in the training of teachers. National assessment also serves to inform professional development needs of in-service teachers (Fisher Citation2008). National assessment results and conclusions offer information regarding the specific areas of teaching that require reinforcement (Colwell Citation2003). On the other hand, what is seen as meaningful as an object for assessment during the final stages of school nationally or internationally strongly determines what is regarded as important to learn and teach during all the school years. What is assessed directs teaching as a hidden hand. What is alternatively not assessed remains at school in a more marginal position.

From the first look, the conclusions about follow-up assessment in music are unambiguous: the pupils’ competence throughout but especially their cultural competence and knowledge of music should be reinforced since there were deficiencies throughout. On the other hand, the follow-up assessment challenges the educational culture based on teacher autonomy. One can ask whether, in the criteria behind the curriculum, the content of musical teaching and its goals should be determined in such a detailed manner that also the national assessment of learning results would be more reliable and at least more easily realised. It is obvious that pupils in Finnish basic education are taught different things in music. But should all pupils, to begin with, be taught the same content? And, are pupils actually treated more equally when they can exploit their teacher's best, though possibly narrow, musical expertise instead of reaching for standardised learning outcomes?

The questions of equality and teacher autonomy nevertheless link with the basic and continuing education of teachers as well: the more freedoms and powers are left to teachers to decide the content of teaching – a feature regarded essential for Finnish high-quality education – the more mastery and subject knowledge teachers need. The autonomy does not mean only freedom but also capacity to act. As Helgøy and Homme (Citation2007) note, ‘[d]evolved autonomy at the teacher level does not mean that teachers are capable of making use of the autonomy’ (233). The earlier research on music teaching at Finnish schools (as well as internationally) indicates that classroom teachers often experience music teaching as challenging and feel that their own skills are insufficient, and consequently, do not even want to teach music (Tereska Citation2003), or do not identify themselves as music teachers (Vesioja Citation2006). Furthermore, pupils are in an unequal position when having a skilful and enthusiastic teacher in music is random. In this light it seems inconsistent that many primary school teacher education programmes in Finland, using the autonomy of universities to design their curricula (Niemi Citation2013), have reduced substantially the amount of music studies.Footnote14 For example, in the University of Helsinki the required amount of music studies is only 3 ECTC (Kairavuori and Sintonen Citation2012). As a consequence, the expertise in music depends essentially on classroom teacher's personal interest and activities in music, and the competence in music varies a lot between teachers. This situation leaves one to ask: who is, then, accountable for the quality of music teaching and learning in schools?

Moreover, when making conclusions on the results of national assessment, there should be some consideration for what such assessment has not achieved with regard to competence in music and the central areas of activity, and how these areas should be taken into consideration in the coming curricular work and assessment. The national assessment addresses the subject specific learning objectives. Yet, there are also wider learning objectives, such as to give the pupil the possibility for versatile growth and to develop his/her self-esteem, to provide support for the pupil's cultural identity, and to aid in the communication and perpetuation of the cultural legacy from one generation to another (FNCC Citation2004, 12). Though the objectives concerning the pupil's holistic growth are not clearly defined as learning outcomes they are as important as the school subject-based goals. In order to assess the learning results of these areas in music, we should ask: Has studying music promoted tolerance and understanding between cultures? Have the experiences of musical expression or playing instruments in a group together opened the finding of one's own selfhood and identity, corroborated self-esteem, advanced social flexibility or channelled the expression of feelings and thereby supported the pupil's holistic growth? Areas of learning that are difficult to assess and the pivotal tasks of basic education must be made so important that these matters cannot, in the name of assessment or because of the limitations of the assessment tools, be underestimated in the development of any subject at school. On the contrary, the assessment tools should be developed in a way that they uncover all the important areas of learning and growth.

As is generally recognised, assessment in music is complex and even disputable. The available assessment tools do not necessarily achieve what is pivotal to musical learning by reference musical competence. The national assessment of learning outcomes in music applied the task formats suitable for academic subjects to assess learning in music subject though it was very clear from the beginning that these tools (pencil-and-paper tasks) would not fit and bring out the essential outcomes of learning in music. While with pencil-and-paper tasks enabled material that was suitable for statistical processing and comparison, the material also required, for example, the scoring of tasks describing musical experiences and music relationship. Thus, the essential qualitative content of the answers could not be made visible and brought up. Also, taking into account the extensive autonomy of individual music teachers would have required the integration of the teacher specific nature of the pupils’ musical knowledge (instead of assuming the existence of a shared and uniform knowledge), and the use of a different assessment structure, tasks, and data to obtain more meaningful assessment results and conclusions.

However, it was important that the national assessment in music was implemented: if national assessment is abandoned completely, a school subject easily loses its significance in the mutual comparison of subjects. As Sims (Citation2000) notes, the fact that the arts subjects are valued enough to be included in a national assessment undertaking is a positive sign of them being viewed as curriculum subjects worthy of this considerable effort and expense. In the case of Finland, the national assessment of learning outcomes in music has raised the awareness of music among other school subjects – at least among the school administration – and has influenced the core-curriculum renewal (see FNCC Citation2014, OPS Citation2016) by reinforcing the areas of music teaching (such as music technology, composition, and music and movement) that, according to the student and teacher questionnaires, have received little attention or have been neglected entirely in music teaching. Furthermore, learning in the artistic disciplines means, among other things, the implementation of cultural equality. From this perspective, the assessment of the artistic disciplines may be seen as a pivotal tool in the development of education.

To conclude, I argue that even though this case has shown that teacher autonomy has challenged the implementation of the national assessment, both are essential to education: national assessment brings out the deficiencies of educational systems (in this case differences in learning between regions, schools, and sexes among other things), which may in turn be recognised in curriculum development on the national level but which also can be addressed most effectively on the local level through autonomous teaching practices. However, there must be a balance between these two aspects. Too broad a level of teacher autonomy can challenge and even threaten the overall quality and equality of education. On the other hand, the strategies and procedures of national assessment have to be tailored according to the requirements of each school subject, in order to bring out the essential elements of learning and to thus be meaningful. If assessment is utilised to closely control the teachers and their work, which is luckily not the case in Finland, teaching too easily focuses only on obtaining high test results, and teachers will also just as easily lose their precious inner motivation and passion for teaching.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marja-Leena Juntunen

Dr Marja-Leena Juntunen is professor in music education at Sibelius Academy, University of the Arts Helsinki. She received her Ph.D. in Music Education at the University of Oulu in 2005. Her main research interest areas cover narrative inquiry, (higher) music education, music teacher education, Dalcroze pedagogy, and embodiment. She has published teaching materials and textbooks as well as several book chapters and articles in international and Finnish research publications. She has served as review reader in various international journals.

Notes

1 Neoliberalism holds that ‘the social good will be maximised by maximising the reach and frequency of market transactions’ and ‘seeks to bring all human action into the domain of the market’. It ‘proposes that human well-being can be best advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets, and free trade’ (Harvey Citation2005, 2–3).

2 PISA (the Programme for International Student Assessment) is a worldwide study by the OECD of 15-year-old school pupils' scholastic performance. It was first performed in 2000 and then repeated every three years. It is done with a view to improving education policies and outcomes.

3 The Education Evaluation Plan determines what subjects are evaluated in a given year, Mathematics and mother tongue (Finnish and Swedish) are assessed systematically. Students’ performance in other subjects is assessed at irregular intervals. (Kumpulainen and Lankinen Citation2012, 76).

4 The notion of Core Curriculum refers to the efforts to integrate the curriculum and can be traced to curriculum reform efforts of the 1930s and 1940s. “The most important of these, the progressive education movement, included a strong emphasis on student-centered, integrative approaches to education, usually under the name of core curriculum” (Vars Citation1991, 14).

5 Because Swedish is Finland's second official language, a number of the comprehensive schools are Swedish-speaking, Finland is actually trilingual country having Sami as a third official language.

6 Music is taught as an obligatory subject in lower secondary school on the 7th or 8th grade. If a school provides instruction also on the 9th grade, it means that music is also taught as an optional subject. Selection in the sample included both such pupils who still had these subjects in their study programme in all upper comprehensive school year levels and those who had studied the subjects concerned at upper comprehensive school only for one year. The sample represents all ninth-year pupils regardless of how much they have received instruction in music, visual arts or handicrafts at comprehensive school; the differences in the total number of teaching hours received by the pupils are rather large (Kuusela Citation2009).

7 Of the pencil-and-paper tasks, the majority (82%) were multiple choice or two-alternative tasks. Slightly over one-fifth of the tasks contained listening samples. Of the tasks, 18% required open responses or filling in an image (e.g. naming the strings on a guitar or setting bar lines into place rhythm-wise).

8 A musical relationship refers to the contacts the pupil has with music; its activities or experiences in the area of music, on the basis of which musical significance and identity are built.

9 According to the instruction, the beginning, midpoint and end of the piece had to be found: it was possible in the realisation to use one's own voice and musical instruments as well as sounds coming from objects, and to incorporate one's own body as an instrument.

10 Since there were not a lot of variation between the re-assessment and the original assessment the results of the re-assessment are not reported.

11 The ratings correspond to the maximum number of points for the production task as follows:

rating 10 = 100% of the maximum number of points

rating 7 = 50% of the maximum number of points

rating 4 = 0% of the maximum number of points

12 The result was regarded as excellent if it was larger than 80% of the maximum score, a good level refers to 71–80%, satisfactory to 61–70%, moderate to 51–60%, adequate to 41–50% and poor to 40% or lower level of competence calculated as a percentage of the maximum test score. The same scale has been used in, for example, the Finnish/Swedish (mother tongue) learning results' assessments (see Lappalainen Citation2004, Citation2006). The scale is prepared for the purpose of learning results-based assessments and is not directly comparable to the school ratings or the good competence criteria mentioned in the Basic Education Curriculum (2004).

13 Girls’ competence was better than that of boys in all types of tasks. Attitudes towards the school subject were also more positive amongst the girls. Moreover, the girls’ report card marks were higher than those of the boys, and they had participated in optional music studies as well as recreational music activities more than the boys.

14 In Finland, at large classroom teachers teach music in grades 1–6.

References

- Anderson, A. K. 2010. “Assessment in Elementary Music Education: One District's Approach to Authentic Assessment in the Elementary Music Classroom.” In The Practice of Assessment in Music Education: Frameworks, Models, and Designs, edited by T. S. Brophy, 179–188. Chicago, IL: GIA.

- Arts and Cultural Education at School in Europe. 2009. European Commission. Education, Audivisual and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA P9 Eurydice). Brussels. Available at: http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/education/eurydice/documents/thematic_reports/113en.pdf/.

- Colwell, R. 2003. “The Status of Arts Assessment: Examples from Music.” Arts Education Policy Review 105 (2): 11–18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10632910309603457

- Fisher, R. 2008. “Debating Assessment in Music Education.” Research and Issues in Music Education 6 (1). http://www.stthomas.edu/rimeonline/vol6/.

- FNBE. 1999. A Framework for Evaluating Educational Outcomes in Finland. Evaluation, 1999: 18. Helsinki: Finnish National Board of Education.

- FNCC. 2004. Finnish National Core Curriculum for Basic Education 2004. Helsinki: Finnish National Board of Education. http://www.oph.fi/english/curricula_and_qualifications/basic_education/.

- FNCC. 2014. Finnish National Core Curriculum for Basic Education 2014. Helsinki: Finnish National Board of Education.

- Gordon, E. 1999. “All About Audiation and Music Aptitudes.” Music Educators Journal 86 (2): 41–46. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/3399589

- Hacker, P., and G. Barkhuizen. 2008. “Autonomous Teachers, Autonomous Cognition: Developing Personal Theories Through Reflection in Language Teacher Education.” In Learner and Teacher Autonomy: Concepts, Realities, and Response. Vol. 1, edited by Terry Lamb, and Reinder Hayo, 161–186. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

- Harvey, D. 2005. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Helgøy, I., and A. Homme. 2007. “Towards a New Professionalism in School? A Comparative Study of Teacher Autonomy in Norway and Sweden.” European Educational Research Journal 6 (3): 232–249. doi: https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2007.6.3.232

- Jakku-Sihvonen, R., and S. Heinonen. 2001. Johdatus koulutuksen uudistuvaan arviointikulttuuriin [Introduction to the renewing assessment culture, in Finnish]. Evaluation 2/2001. Helsinki: Finnish National Board of Education.

- Juntunen, M.-L. 2011. “Musiikki” [Music].” In Perusopetuksen musiikin, kuvataiteen ja käsityön oppimistulosten arviointi 9. vuosiluokalla [Assessment of Learning Outcome in Music, Visual Arts, and Craft Education in the 9th Grade of Basic Education, in Finnish], edited by S. Laitinen, A. Hilmola, and M.-L. Juntunen, 36–95. Follow-up report of Education 2011:1. Helsinki: National Board of Education.

- Kairavuori, S., and S. Sintonen. 2012. “Arts Education.” In Miracle of Education. The principles and practices of teaching and learning in Finnish schools, edited by H. Niemi, A. Toom, and A. Kallioniemi, 209–223. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Kallio, A. 2015. “Drawing a Line in Water: Constructing the School Censorship Frame in Popular Music Education.” International Journal of Music Education 33 (2): 195–209. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761413515814.

- Kumpulainen, K., and T. Lankinen. 2012. “Striving for Educational Equity and Excellence: Evaluation and Assessment in Finnish Basic Education.” In Miracle of Education. The Principles and Practices of Teaching and Learning in Finnish Schools, edited by H. Niemi, A. Toom, and A. Kallioniemi, 69–82. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Kuusela, J. 2009. Selvitys taide- ja taitoaineiden opiskelutuntimääristä perusopetuksessa [Report of the Amount of Teaching in Art and Craft Subjects in Basic Education, in Finnish]. Helsinki: Finnish National Board of Education.

- Laitinen, S., A. Hilmola, and M.-L. Juntunen. 2011. Perusopetuksen musiikin, kuvataiteen ja käsityön oppimistulosten arviointi 9. vuosiluokalla [Assessment of the Learning Outcome in Music, Visual Arts, and Craft Education in the 9th Grade of Basic Education; in Finnish]. Follow-up Report of Education 2011:1. Helsinki: Finnish National Board of Education, 36–95.

- Lappalainen, H.-P. 2004. Kerroin kaiken tietämäni. Perusopetuksen äidinkielenja kirjallisuuden oppimistulosten arviointi 9. vuosiluokalla 2003. [I Told Everything I Knew. The Assessment of Learning Outcomes in Mother Tongue and Literature on the 9th Grade in 2003, in Finnish]. Assessment of Learning Outcomes 2004: 2. Helsinki: Finnish National Board of Education.

- Lappalainen, H.-P. 2006. Ei taito taakkana ole. Perusopetuksen äidinkielen ja kirjallisuuden arviointi 9. vuosiluokalla 2005. [A Skill in Not a Burden. The Assessment of Learning Outcomes in Mother Tongue and Literature on the 9th Grade in 2005, in Finnish]. Assessment of learning outcomes 2006: 1. Helsinki: Finnish National Board of Education.

- Marner, A., H. Örtegren, and C. Segerholm. 2004. Nationella utvärderingen av grundskolan 2003 (NU-03): bild. [National Assessment of Basic Education 2003: Visual Art, in Swedish]. Subject Report for the Report 253. Stockholm: Enlander Gotab.

- NAEP. 2008 National Assessment of Educational Policy. https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/arts/moreabout.aspx

- Niemi, H. 2013. “The Finish teacher education. Teachers for Equity and Professional Autonomy.” Revista Española de Educación Comparada 22: 117–138. doi: https://doi.org/10.5944/reec.22.2013.9326

- Niemi, H., A. Toom, and A. Kallioniemi, eds. 2012. Miracle of Education: The Principles and Practices of Teaching and Learning in Finnish Schools. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- OPS. 2016. Renewal of the Core Curriculum for Pre-primary and Basic Education. http://www.oph.fi/english/current_issues/101/0/ops2016_renewal_of_the_core_curriculum_for_pre-primary_and_basic_education/.

- Pearson, C. L., and W. Moomaw. 2005. “The Relationship between Teacher Autonomy and Stress, Work Satisfaction, Empowerment, and Professionalism.” Educational Research Quarterly 29 (1): 38–54.

- Sahlberg, P. 2011. Finnish lessons. What Can the World Learn from Educational Change in Finland? New York: Teachers College Press.

- Sandberg, R., G. Heiling, and C. Modin. 2005. Nationella utvärderingen av grundskolan 2003 (NU-03): Musik. [National Assessment of Basic Education 2003: Music, in Swedish.] Subject Report for the Report 253. Stockholm: Enlander Gotab.

- Shuler, S., P. Lehman, R. Colwell, and R. Morrison. 2009. “Music Assessment and the Nation's Report card: MENC's Response to the 2008 NAEP and Recommendations for Future NAEP in Music.” Music Educators’ Journal 96 (1): 12–13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0027432109346224

- Sims, W. L. 2000. “Why Should Music Educators Care About NAEP?” Teaching Music 7 (4): 40–45.

- Tereska, T. 2003. “Peruskoulun luokanopettajiksi opiskelevien musiikillinen minäkäsitys ja siihen yhteydessä olevia tekijöitä” [Pre-service Elementary Teachers’ Self-concept in Music, and Its Contributing Factors, in Finnish]. Doctoral diss., University of Helsinki. Research Report 243.

- Thoonen, E. E., P. J. Sleegers, F. J. Oort, T. T. Peetsma, and F. P. Geijsel. 2011. “How to Improve Teaching Practices The Role of Teacher Motivation, Organizational Factors, and Leadership Practices.” Educational Administration Quarterly 47 (3): 496–536. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X11400185

- Tirri, K. 2012. “The Core of School Pedagogy: Finnish Teachers’ Views on the Educational Purposefulness of Their Teaching.” In Miracle of Education. The Principles and Practices of Teaching and Learning in Finnish Schools, edited by H. Niemi, A. Toom, and A. Kallioniemi, 55–66. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Toom, A., and J. Husu. 2012. “Finnish Teachers as ‘Makers of the Many’: Balancing Between Broad Pedagogical Freedom and Responsibility.” In Miracle of Education. The Principles and Practices of Teaching and Learning in Finnish Schools, edited by H. Niemi, A. Toom, and A. Kallioniemi, 39–54. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Vars, G. F. 1991. “Integrated Curriculum in Historical Perspective.” In Abstracts International 20: 1830–1831.

- Vesioja, T. 2006. “Luokanopettaja musiikkikasvattajana” [A Classroom Teacher as a Music Educator, in Finnish]. Doctoral diss., University of Joensuu, Publications in Education 113.

- Vitikka, E., L. Krogfors, and E. Hurmerinta. 2012. “The Finnish National Core Curriculum: Structure and Development.” In Miracle of Education. The Principles and Practices of Teaching and Learning in Finnish Schools, edited by H. Niemi, A. Toom, and A. Kallioniemi, 83–96. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Appendix

Examples of tasks in different content areas:

Musical knowledge and cultural familiarity

Example 1 (listening):

Recognize the origin of the following musical sample. Circle the right option.

Trinidad

South-Africa

USA

France

Example 2 (listening):

Recognise the style of the following musical sample. Circle the right option.

Heavy metal

Techno

Progressive rock

Hard rock

Knowledge related to musical action

Example 3:

What is the chord in the picture? Circle the right option.

G-major

E-minor

D-major

A-dominant 7

Example 4:

Write the note name of each string of the quitar in the circle.

Example 5

Which one of the following drum patterns is a Waltz-rhythm? Circle the right option.

Pupils’ personal relationship with music

Example 6

What musical concert, performance or experience (at school or outside) do you remember very well?

Describe that concert, performance or experience:

‘I remember this concert/performance/experience because’ continue:

Knowledge related to ‘civics of music’, meaning copyrights and hearing protection

Example 7

How long can you stay in the volume of 100 dB (for example, a rock concert or disco) without hearing protection without risking your hearing? Circle the right option.

1.5 minutes

15 minutes

1.5 hours

any length of time