ABSTRACT

The global COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted music education across the world, resulting in radical changes to the field of practice, accelerating a ‘turn’ toward online digital musical experiences. This digital ‘turn’ is likely to influence the future of music education in a variety of complex and inter-connected ways. In this special issue, we explore the implications of such a ‘turn’ for music educators and their students / participants, and highlight some of the ways in which music researchers and educators have responded to the crisis. We hope these narratives will help illuminate some of the ways in which music education might recover its equilibrium, as well as make a contribution more generally to the complex business of human recovery in a post-COVID world.

Introduction

Enforced social isolation and the prohibition of ‘music(k)ing’ (Elliott Citation1995; Small Citation1998) – especially group singing – in many parts of the world has meant that such practices have had to either cease during the pandemic crisis, or adapt to become predominantly online experiences. Music education too has undergone a similarly significant ‘turn’ toward online experiences through the pandemic in order to continue. In autumn 2020, we published a call for papers which would shed light on any of the following themes:

the practical implications of the digital ‘turn’ in music education;

the relational aspects of music education in a digital world;

the psychological implications of the digital ‘turn’ in music education for music educators as well as for their students / participants;

music education and the process of recovery / sustainable development in a post-COVID world;

implications of the digital ‘turn’ in music education for teacher education and musician training.

As many of the contributors to this special issue make clear, any perceived ‘turn’ toward online experiences in music education is not a new phenomenon; digital technology and online learning have formed an important part of music education for some decades. What is perhaps new during the global pandemic crisis has been the need for music education to operate principally within a digital / online domain, and this necessary ‘turn’ has caused considerable disruptions to practice for many music educators. What we hope the papers in this special issue highlight are some of the ways in which these disruptions have been experienced, and more significantly how their impact has been minimised and adapted to.

Content

The majority of the papers included in this issue report on findings of research undertaken during the pandemic crisis, while some introduce different positions in relation to the crisis, and point to emerging ways of thinking about or re-conceptualising music education practice. We hope that both of these perspectives – changes in or adaptations to practice alongside new ways of thinking about such practice – will help both researchers and practitioners to make sense of the ‘new normal’ music educators and researchers collectively face.

As well as each paper being an independent inquiry or perspective, we have also arranged them in a loose sequence which we hope will take a reader on a meaningful journey through the special issue, and which we summarise below. We start with some papers which include what we think contain helpful concepts to make sense of some of what follows, before proceeding into a number of studies of music education in different contexts. We then turn our attention to some studies which focus very much on practitioner experience, and conclude with a number of papers which either introduce promising methodologies for interrogating practice, or illuminate possible approaches for the theory and practice of music education during a period of recovery.

Diego Calderón-Garrido

Calderón-Garcia’s study of the experiences of over 300 Spanish teachers during the crisis introduces a number of useful perspectives which help to set the scene for this special issue. Firstly, they highlight the positive contribution that music education might be seen to have made to family life during lockdown in some situations, a perhaps unexpected benefit of the crisis. They also introduce an important and helpful distinction between ‘online learning’ and ‘emergency remote teaching’ (Hodges et al. Citationn.d.), which greatly assists in understanding the complex issues affecting the digital ‘turn’ in music education. After all, if ‘social isolation is a distressing experience when it is externally imposed’ (al-Rodhan Citation2020), music education – in common with all education – has been operating in conditions of heightened distress for many over the last twelve months, which has clearly had an impact on practice.

Sarah-Jane gibson

Gibson’s article highlights the tensions implicit in adaptations to practice very clearly, in the context of an ‘offline’ community music practice being required to move ‘online’ during the pandemic. The resulting changes to practice are conceptualised by referring to the significant differences between online and offline music education worlds, and the need to think differently about ways of practicing music education that music educators may have come to take for granted in exclusively offline settings. This encounter of offline worlds re-framed in an online setting requires considerable shifts in thinking to comprehend, and drawing on the considerable literature surrounding online music education clearly helps to make more sense of these disruptive transitions. She also grounds her argument in a consideration of Turino’s fields of recorded and performing music (Turino Citation2008) and the ways in which this ‘turn’ toward online continuation of offline musical practices represents a greater convergence between these fields, something we discuss later as an important distinction to inform music education practices going forward. Her analysis provides a very helpful framework for understanding some of the impact of the pandemic crisis not just on music education practice, but more broadly on the wider field of music and its complex array of interconnected domains.

Andrea schiavio, michele biasuttui & roberta phillipe

Looking to the experience of conservatoire students during the crisis, Schiavio et al’s article highlights a range of challenges and also benefits of the ‘turn’ toward online music education, not least the pressures this places upon educators to adapt swiftly through the use of technology to maintain high pedagogical standards. Their article illustrates very clearly the complexities of teaching during the pandemic, with students’ narrative accounts of their experiences highlighting how their musical development may have been disrupted by the pandemic, but also how developing strategies and mindsets for overcoming such disruptions – especially with their peers and their teachers – can be a creative opportunity in itself. As they suggest, ‘the need for novelty and exploration [in response to the crisis] led to new forms of communication among students, highlighting the link between creativity and social connectedness’. The implications for teachers are very clear – in order to continue to be integral to students’ ongoing development, they have to be able to adapt pedagogical approaches fluently and efficiently in response to unfamiliar and disruptive circumstances, and this also requires institutions to mobilise the necessary resources and training for their workforce to support them to be able to respond most effectively, echoing similar concerns in other papers in the issue.

Dainora daugvilaité

At the other end of the spectrum of music education activity, Daugvilaité’s article introduces us to a detailed consideration of some of the effects of the digital ‘turn’ on the experience of beginner and intermediate piano students. Relying on exploratory case studies, the research seeks to investigate whether students’ approaches to learning change in the online scenario. It also explores engagement levels in synchronous online learning and motivation to practice in between lessons. The paper explores crucial issues that have received much attention from research on face-to-face music learning, but which have not yet been explored in relation to the sudden ‘turn’ to online learning. Although students and parents both refer to their preference for face-to-face teaching with the physical presence of a teacher as an enhancing factor, there are also important considerations for teaching to take from this study – students became more independent and progressed at normal pace when learning online. Comparisons between online and face-to-face learning are unavoidable but the fact that independence in learning can be further developed in this scenario sheds light on how adaptations of teaching approaches can be made to engage with the ‘turn’ in music education. The study also points out how families adapted to the new online scenario and it makes a positive contribution towards the future of music education demonstrating how instrumental teaching can be shaped through a broader approach where online interactions may complement more traditional models of face-to-face pedagogy.

Karen salvador, erika knapp & whitney mayo

Shifting to music education within the community, Salvador et al focus their research on a large number of participants from all ages attending two Community Music Schools, which were closed due to the pandemic. All activities, including music therapy, were shifted online. Students, parents, caregivers, teachers, ensemble directors, music therapists and administrators took part in a mixed methods study responding to surveys and interviews that give a holistic view of their experiences and perspectives of online interactions in the context of community music. The article makes an important contribution to music education, highlighting themes that emerged from the data, including relational aspects of ‘trustworthiness’ and ‘hospitality’ in online learning during a global pandemic. They outline some of the implications for teacher education and professional development, suggesting that the ‘turn’ to online learning has pushed people ‘over the hump’ but also that this requires time and effort, and that appropriate technology and training needs to be available for everyone involved, a recurrent theme within this special issue. In the context of the ‘turn’ during lockdowns, not all families could participate in the online experiences, others refused, others had negative experiences, and many found ways of remaining positive within their experiences. The authors make a powerful statement that ‘supporting teachers, students, and families in weathering unexpected changes and assisting them in creating a successful experience could bolster the sustainability of community music schools’.

Lee cheng & gigi lam

Turning to some larger studies of practitioner experience, Cheng & Lam provide a detailed analysis of the psychological impact of the pandemic on music teachers in Hong Kong, using a multistrategy approach to understand this impact through both quantitative and qualitative measures. Their work points to an important feature of educator resilience, that perhaps not unexpectedly, less experienced teachers – as well as those who only taught music – were more susceptible to the stresses inherent in adapting to emergency remote teaching. They identify a range of such stressors, including increased parental involvement, inconsistent school management systems, technological challenges and digital poverty, pointing to how the presence of multiple stressors can have a destabilising effect on an educator’s best intentions to remain pedagogically resilient.

Ketil thorgersen & annette Mars

Thorgersen & Mars also examine a large population of music educators through an analysis of activity on a Swedish music educators’ Facebook group during the crisis. They emphasise the importance of ‘teacher collegiality’ within this particular group as a defining characteristic of educator resilience, highlighting a theme found elsewhere in the special issue of professional peer support as an important resource for dealing with the crisis. In relation to the notion of ‘convergence’ of musical domains, and the disruptions brought about by the sudden need for emergency remote education, they illustrate the role that other professionals can play in supporting educator resilience – not just as sounding boards but as a whole networked community where a sense of belonging and solidarity can help strengthen educators’ personal and collective professional identities in relation to a common threat.

Dawn joseph & lucy lennox

Further emphasising the theme of collegiality, Joseph & Lennox introduce ‘narrative inquiry’ (Clandinin Citation2013) as a methodological approach to develop practical insights into the situation they each found themselves in as music educators, both independently and in dialogue with each other. For situations of complexity, ambiguity or uncertainty – such as have been very present through the current / recent crisis – this approach offers a novel way of exploring those uncertainties. Through a process of telling and subsequent re-telling of their lived experiences of the ‘thrills, twists and turns’ of music education during lockdown, they are able to highlight some of the ways in which this collegiate approach has helped them to ‘re-live’ their practice i.e. to find new ways of addressing some of the challenges faced. The rich descriptions of their experiences, and that of some of their students, helps us to appreciate the complex ways in which the forced ‘turn’ to online learning has disrupted familiar narratives of participation, and how some of those narrative arcs are being re-written.

Andrew goodrich

Staying with the theme of beginning to think differently about the crisis and possible strategies for capitalising on some of its repercussions for music education, Goodrich presents a detailed literature review of one possible opportunity to emerge from the crisis, that of peer mentoring. A number of the papers point to shifts in pedagogical practice, especially shifts which respond to different ways of knowing which a distributed knowledge system like the internet throws up (Wegerif Citation2012). The dialogic opportunities for educators recognised by Thorgersen & Mars and Joseph & Lennox might also have resonance in opportunities for more dialogic peer learning, specifically that of peer mentoring, where (more experienced) students can support other (less experienced) students’ development. While by no means the only kind of structured peer learning available to students and their teachers, Goodrich’s detailed review of the literature on peer mentoring provides a valuable and detailed introduction to the subject, and a launchpad for further investigation into the pedagogical possibilities of such an approach.

Juliet hess

Hess’ paper presents an individual position in relation to the current crisis, and is addressing directly the issues raised by question 4 (above) concerning music education’s potential value as a resource of imagination in the recovery from the impact of the pandemic. Her article takes a philosophical approach to understanding music education’s potential role in recovery from the current crisis, by locating it in relation to themes of social justice. We’re pleased to be able to include this perspective in the special issue as we hope it will provoke discussion and debate around the broader and more complex nexus of existential crises which the pandemic might be seen to be part of, and the potential role of music education in addressing such complexity. In giving space for these issues to be raised, we hope to stimulate a discourse among music education researchers about these larger philosophical issues to do with the purpose of music education in a globally sustainable future. Hess reminds us of our ethical responsibilities as educators, not just to our students but to our broader responsibilities as citizens on a fragile planet facing multiple crises, and how our practice as educators might address some of those challenges.

Discussion

In this section, we discuss some of the over-arching themes which we see as emerging from this collection of papers, including the distinction between online learning and emergency remote teaching and the notion of ‘convergence’ between recording and performing fields of music alluded to earlier, as well as some of the relational issues which have surfaced through the papers. In the context of recovery from the crisis, we also consider implications for future music education practice, in particular some of the pedagogical shifts which this collection of papers highlights.

Online learning and emergency remote teaching

An important distinction which this collection highlights is the difference between online learning and what Calderón-Garrido introduces as ‘emergency remote teaching’. Generally speaking, online learning refers to teaching and learning that occurs over a network connection and which can take different forms: synchronous learning (that is, real time), when musicians located at remote geographical locations interact over a network to teach, learn, rehearse and/or perform (Lisboa, Jonasson, and Johnson Citationin press); asynchronous learning (taking place at different times) which can occur through various online platforms; and blended or hybrid learning when teaching and learning happens through a structured mixture of both terms above (Mayadas, Miller, and Sener Citation2015).

Online teaching and learning is not a new approach to education. In 1947, the medical teaching community used closed-circuit television for American medical teaching, (Castle Citation1963) later followed by cross-continent broadcasts via telephone connections.

Online learning is therefore not a new feature of music education and performance either, and a comprehensive literature has already built up around it e.g. (Brändström, Wiklund, and Lundström Citation2012; Buhl, Ørngreen, and Levinsen Citation2014; Johnson Citation2017; Waldron, Horsley, and Veblen Citation2020). From as early as the 1990s Higher Education music institutions across the world have been investing in state-of-the art technology to complement face-to-face teaching and learning and to assist with remote rehearsing and performing. Many of these institutions have collaborated with technology companies in order to improve audio and video quality for musicians as well as to reduce latency in synchronous online learning (Lisboa, Jonasson, and Johnson Citationin press). The aim has often been to achieve telepresence, a state where participants perceive themselves as being present within a remote or virtual site (Draper, Kaber, and Usher Citation1998). Online learning has become common practice across music conservatoires and universities prior to the pandemic as it also allows for the expansion of international collaborations; for developing new forms of teaching and learning; for lowering costs and reduction of carbon emissions due to decreased air travel.

However, the sudden need for ‘emergency remote teaching’ that many music educators were faced with in 2020 throws up a whole other set of challenges, where there was a sudden and unexpected need to adapt to a situation of social isolation and where some form of online learning became the only way to sustain any sort of music education practice. With the need for state-of-the art studio equipment down to home computer systems of laptops and headsets, educators were faced with pedagogical demands never before envisaged. Many of the authors in this collection point to the challenges of home schooling, lack or preparedness, inconsistent availability of resources including devices and reliable internet connection, all of which conspire in new ways to either facilitate or thwart attempts to provide continuity in music education. As stated in Joseph & Lennox’s paper: ‘using new technology was a steep learning curve for both authors given the sudden move to online teaching due to the lockdown’.

Convergence

This increased use of technology by music educators in order to sustain their practice through the crisis highlights another important feature to emerge, which we might see as a convergence between recording and performing fields of music. Especially for ensemble musical activity, playing and performing with other people is what drives participation. However, the audio latency problems associated with domestic online platforms mean that attempts at synchronous ‘music(k)ing’ are ultimately disappointing. As Gibson highlights, one response to this situation is a further ‘turn’ by music educators toward the use of recorded materials to give the impression of live performance in online musical activity, through the use of high fidelity recordings and / or recordings produced using studio audio software.

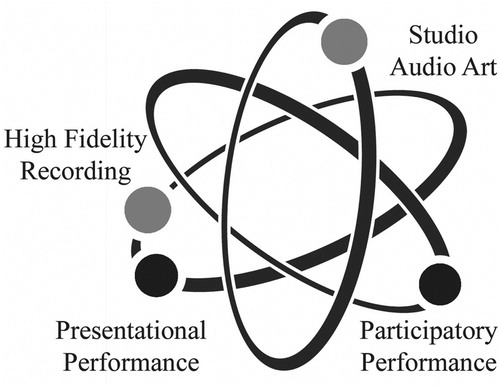

We might see this blending of musical fields as part of a broader process of ‘convergence’ i.e. an ongoing feature of the music industry since the digital distribution of recorded music disrupted established means at the turn of the century (Anderson Citation2009). Originally conceived as a term to describe ‘the flow of content across multiple media platforms’ (Jenkins Citation2008, 2), we might also see convergence as occurring within and across the various sub-fields which characterise the field of music in its broadest sense. As Gibson summarises in her article, Turino (Citation2008) classifies these various sub-fields into two categories: performing fields (presentational performance and participatory performance) and recording fields (high fidelity and studio audio art). Gibson’s article outlines in some detail the ways in which these fields converge in the transition between an established offline experience of festivals of music-making into a largely online experience of participatory music during the pandemic.

The experience of convergence within the field of music over the last twenty years might have been more apparent within its performance domains, with the boundaries between presentational performance or the ‘performance of works’ and participatory performance or the ‘performance of relationships’ (Camlin Citationin pressa; Citationin pressc; Camlin, Boyce-Tillman, and Hendricks Citationin press; Camlin, Daffern, and Zeserson Citation2020) increasingly blurred and contested, as evidenced by the rise of disciplines such as community music (CM), music, health and wellbeing and the social impact of music-making (SIMM) as subjects within the academy. What many of the articles in this collection point to is also an accelerated convergence with recorded fields of music as well – the use of high fidelity and studio audio art as increasingly essential elements of an online music education practice. With effective online synchronous music-making largely out of the reach of a domestic audience, manipulating sounds using audio software to be able to re-create a musical experience that resembles the memory of synchronous music-making has become one of the few ways that offline group musical practices have been able to move online, as Gibson’s article discusses, and as reflected in the growth in popularity of the phenomenon of online ‘virtual’ choirs and music ensembles during the crisis.

Rather than seeing this convergence as a more straightforward drawing together of disparate practices, it rather seems to be the case that these musical domains operate with each other more like a complex constellation of inter-dependent dimensions, with different shifts in emphasis occurring in different contexts, as illustrated in . It is with these complex and emergent multi-dimensional shifts in the broad field of music that the papers in this special issue are grappling.

Figure 1. Convergence between Turino’s (Citation2008) categorisation of performance (in black) and recorded (in grey) fields of music. Source: figure by authors.

Disruptions to any field by information technology lead to changes in the way that the field operates (Mason Citation2016, 109–145), as should be immediately apparent to anyone who has lived through the last twenty years of dramatic changes to the field of music resulting from the digital distribution of recorded music (Anderson Citation2009). We should therefore expect that this ongoing convergence between music’s various domains should lead to further disruption, as well as opportunity. As technological innovations begin to overcome the limitations of online musical experiences, consumers and learners alike will be faced with an increasing array of choices about how to consume or learn music. As the field of music re-constitutes itself around a ‘new normal’ of increased hybridisation, music educators too need to adapt and innovate their practice to respond to the new opportunities and challenges which emerge. What we hope this issue presents is some of the ways in which those practices – and practitioners – are already adapting and innovating.

Turning to one another

In spite of these disruptions to practice, a common theme described by the different studies is the extent to which addressing the challenges of emergency remote teaching involved turning to others for practical, psychological, familial, peer and / or collegiate support. Thorgersen & Mars’ article highlights the importance of collegiality in developing professional resilience, while Salvador et al and Joseph & Lennox’ papers illustrate this collegiality in practice. Both sets of authors also highlight the positive experience of siblings and parents being more involved in students’ musical activities as a way of strengthening family unity, especially during this period of adversity. Interruptions by other family members, pets or other aspects of a students’ home life might normally be considered a distraction to learning, but in these circumstances they also serve to blur the boundaries between home and school, enlisting other family members into a student’s musical development whilst simultaneously giving teachers insights into students’ identities outside of a classroom setting. Furthermore, despite the stresses of lockdowns during a pandemic with serious economic implications, there are reports of music instrument sales doubling during the pandemic, even whilst shops were closed (Breathnach Citation2020), pointing to the possible resurgence of home-based musical culture as a potentially valuable resource for individual musical development.

Recovery

Finally, we turn to questions of recovery. Hess’ article points to a number of related current crises – climate crisis, racial injustice, economic instability – which face human society in the present moment, but even this view is only partial. Forecasting over the next thirty years points to a complex cocktail of ageing populations, reduced Potential Support ratios (PSR), ongoing population growth and attendant mass migration alongside environmental degradation and increasing inequality which have been known about since the Brundtland report (Brundtland Citation1987) and which can be recognised in the current policy of the United Nations toward sustainable development (United Nations Citation2015). Awareness of these complex global issues, alongside the potential of future zoonotic outbreaks as a feature of a ‘pandemic age’ (UN Environment Citation2020) may come to define the way humans are able to co-exist on an increasingly fragile planet for some time to come. In many ways, the current pandemic crisis has highlighted the fragility of global systems, and therefore research of all kinds – including music education research – needs to have these existential complexities in mind as our focus turns to questions of recovery. Hess’ invokes perspectives such as Critical Reconstructionism, Abolitionism, and Critical Pedagogy as valuable frameworks to re-imagine the function of music education research going forward.

However, we need to be cautious about glorifying the potential value of music education to ‘imagine’ alternative futures. The problem with using our imagination to conceive of better worlds is that, as Rickie Lee Jones expresses it, ‘the world that you make inside your head is the one you see around you; but the one that you see is the one that you make’ (Lee-Jones Citation1989). In other words, imagining any future from within a given system may be prone to recreating at least some of the inconsistencies or inequalities of that system. Hess cautions vigilance in ensuring our approaches to music education are grounded in an ethical praxis, although remaining ‘vigilant’ to the ways in which our practices might contribute to unequal distribution of cultural resources may be easier said than done (Camlin Citationin pressb). Centring such vigilance within a cautiously embodied experience of music, as Hess suggests, perhaps provides more of an assurance of authentic and empathic connection.

We should also perhaps take comfort from the assumption that as well as providing the potential for metaphorical recovery in the way that it offers opportunities to experience particular social realities which may differ from those of everyday life, music making offers us a more literal potential for ‘mutual recovery’ (Camlin, Daffern, and Zeserson Citation2020) through the way in which our neurobiology may come to resonate with that of others through the act of musical entrainment (Camlin Citationin press). As Schiavio et al highlight, ‘online collaborations, dialogue, and open communication among students may not be enough when compared to the live presence of others’, and it is to the re-emergence of face-to-face ‘music(k)ing’ that we must surely now turn with hope.

Implications for future practice

Clearly, the pandemic crisis has disrupted music education practice considerably, and some of these disruptions are explored in detail by the contributions to this special issue. What is also clear is that the pandemic crisis has also prompted important conceptual and epistemological shifts in both theory and practice. Practitioners and researchers are both acting and thinking their way beyond these disruptions. It is a valuable observation that ‘music teachers are realising that they need to transform themselves from instructors into facilitators of students’ learning’ (Cheng & Lam) in response to the crisis, echoed in the observations of (Schiavio et al) into students’ experience of conservatoire teaching. As the online world contains many more resources than just the teacher, understanding the role of the teacher amidst that complexity becomes a matter of considerable ‘pedagogical sensitivity’ (Huhtinen-Hildén and Pitt Citation2018; van Manen Citation2008). Inconsistencies both in provision of resources and in support for educators themselves, can inevitably lead to compromises in the student experience, a theme picked up by a number of articles in this special issue, highlighting the importance of technological resourcing, training and support to enable educators to provide the best possible experience for their students.

Similarly, it is important to recognise that any ‘turn’ toward online music education necessitated by the pandemic should not contribute to any unhelpful binary thinking about online and offline experiences. As this collection of articles illustrates, there are clear benefits of both online and offline music education, and both domains need to be considered in the devising of music curricula, and in how those curricula are provisioned.

At the time of going to press, the disruptions and shifts discussed herein are only partially evolved and resolved. This special issue represents some initial insights into the impact of the global pandemic on music education, but that impact is likely to be played out over many years. We hope that the various perspectives presented highlight the critical importance of an ethical praxis (Elliott and Silverman Citation2014; Regelski Citation2009) of music education, with research and practice closely ‘imbricated’ (Nelson Citation2013) throughout the period of recovery. As changes in practice continue to occur in response to the conditions of uncertain recovery, research plays a vital role in articulating, transmitting, critiquing and indeed influencing those shifts, emphases and practices.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

David A. Camlin

Dr. Dave Camlin is a musician based in Cumbria, UK whose practice spans performance, composition, teaching, socially-engaged music practice and research. He is Lecturer in Music Education at the Royal College of Music and Trinity-Laban Conservatoire, and was Head of Higher Education and Research at Sage Gateshead from 2010–19. His research focuses on group singing, music health and wellbeing, musician training and Community Music, as well as pioneering the use of ‘distributed ethnography’ as a method for research into cultural phenomena. He performs in various guises, and leads a number of community music choirs and projects.

Tania Lisboa

Dr. Tania Lisboa is Research Fellow in Performance Science at the Royal College of Music and also an honorary Research Fellow at Imperial College London and an honorary member of the RCM. Her current research focuses on expert memory, performance education, communication in online rehearsal and music and autism. She has acted as a commissioner to the International Society for Music Education’s Commission for the Education of the Professional Musician from 2014 to 2020 and she has managed the RCM’s videoconferencing programme for over 15 years. Dr. Lisboa established one of the world's first videoconferencing labs at the RCM in the early 2000s and since then she has been an advocate for the exploration of low-latency audio visual systems for musical teaching and remote collaboration. Activities in this area include links with international conservatoires and universities in the USA, Europe and Asia. In parallel with her academic research, she pursues an active career as a solo cellist with concert engagements that encompass Europe, Asia, and North and South America. In addition to the standard repertoire, she has pioneered recordings of Brazilian music including the complete works for cello and piano by C Guarnieri and by H Villa-Lobos for Meridian Records, the latter in three volumes.

References

- al-Rodhan, N. 2020. Social Distancing: A Neurophilosophical Perspective. Areo, April. https://areomagazine.com/2020/04/07/social-distancing-a-neurophilosophical-perspective/.

- Anderson, C. 2009. The Longer Long Tail: How Endless Choice is Creating Unlimited Demand. New York: Random House Business.

- Brändström, S., C. Wiklund, and E. Lundström. 2012. “Developing Distance Music Education in Arctic Scandinavia: Electric Guitar Teaching and Master Classes.” Music Education Research 14 (4): 448–456. doi:10.1080/14613808.2012.703173.

- Breathnach, C. 2020. “British Music Stores Report Spiking Sales During the Pandemic.” Guitar.Com | All Things Guitar, September 10. https://guitar.com/news/industry-news/uk-stores-sales-spike-covid-19/.

- Brundtland, G. H. 1987. Our Common Future. 1st ed. USA: Oxford University Press. http://www.un-documents.net/wced-ocf.htm.

- Buhl, M., R. Ørngreen, and K. Levinsen. 2014. “Teaching Performance in Performing Arts: Videoconferencing at the Highest Level of Music Education.” In Performativity, Materiality and Time: Tacit Dimensions of Pedagogy. European Studies on Educational Practice (Vol. 4, edited by A. Kraus, M. Buhl, and G.-B. von Carlsburg, 21–40. Denmark: Waxmann.

- Camlin, D. A., H. Daffern, and K. Zeserson. 2020. “Group Singing as a Resource for the Development of a Healthy Public: A Study of Adult Group Singing.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 7 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1057/s41599-020-00549-0.

- Camlin, D. A. in pressa. “Encounters with Participatory Music.” In The Chamber Musician in the Twenty-First Century, edited by M. Dogantan-Dack. OUP. https://www.mdpi.com/books/pdfview/edition/1082.

- Camlin, D. A.. in press. “Recovering our Humanity—What’s Love (and Music) Got to Do With It?” In Authentic Connection: Music, Spirituality, and Wellbeing, edited by J. Boyce-Tillman and K. Hendricks. Switzerland: Peter Lang.

- Camlin, D. A. in pressb. “Mind the Gap!.” In Community Music at the Boundaries, edited by L. Willingham. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. https://www.wlupress.wlu.ca/Books/C/Community-Music-at-the-Boundaries.

- Camlin, D. A. in pressc. “Organisational Dynamics in Community Ensembles.” In Together in Music, edited by H. Daffern, F. Bailes, and R. Timmers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Castle, C. H. 1963. “Open-circuit Television in Postgraduate Medical Education.” Journal of Medical Education 38: 254–260.

- Clandinin, D. J. 2013. Engaging in Narrative Inquiry: 09. 1st ed. California: Routledge.

- Draper, J. V., D. B. Kaber, and J. M. Usher. 1998. “Telepresence.” Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 40 (3): 354–375. doi:10.1518/001872098779591386.

- Elliott, D. J. 1995. Music Matters: A New Philosophy of Music Education. New York: OUP USA.

- Elliott, D. J., and M. Silverman. 2014. Music Matters: A Philosophy of Music Education. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hodges, C., S. Moore, B. Lockee, T. Trust, and A. Bond. n.d. “The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning.” Educause Review. Retrieved 17 February 2021, from https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning.

- Huhtinen-Hildén, L., and J. Pitt. 2018. Taking a Learner-Centred Approach to Music Education: Pedagogical Pathways. 1st ed. Abingdon / New York: Routledge.

- Jenkins, H. 2008. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. Revised ed. New York: New York University Press.

- Johnson, C. 2017. “Teaching Music Online: Changing Pedagogical Approach When Moving to the Online Environment.” London Review of Education 15 (3): 439–456. doi:10.18546/LRE.15.3.08.

- Lee-Jones, R. 1989. The Ghetto of My Mind: Vol. Flying Cowboys [CD]. Geffen.

- Lisboa, T., P. Jonasson, and C. Johnson. in press. “Synchronous Online Learning, Teaching and Performance.” In The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance (Vol. 2), edited by G. McPherson. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mason, P. 2016. PostCapitalism: A Guide to Our Future. London: Penguin.

- Mayadas, F., G. Miller, and J. Sener. 2015, July 7. E-Learning Definitions. OLC. https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/updated-e-learning-definitions-2/.

- Nelson, R. 2013. Practice as Research in the Arts: Principles, Protocols, Pedagogies, Resistances. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Regelski, T. 2009. “The Ethics of Music Teaching as Professon and Praxis.” Visions of Research in Music Education 11.

- Small, C. 1998. Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

- Turino, T. 2008. Music as Social Life: The Politics of Participation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- UN Environment. 2020. Preventing the Next Pandemic: Zoonotic Diseases and how to Break the Chain of Transmission. UN Environment, June 7. http://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/statement/preventing-next-pandemic-zoonotic-diseases-and-how-break-chain.

- United Nations. 2015. Sustainable Development Goals. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/?menu=1300.

- van Manen, M. 2008. “Pedagogical Sensitivity and Teachers Practical Knowing-in-Action.” Peking University Education Review 1 (1): 1–23.

- Waldron, J. L., S. Horsley, and K. K. Veblen, eds. 2020. The Oxford Handbook of Social Media and Music Learning. New York: OUP USA.

- Wegerif, R. 2012. Dialogic: Education for the Internet Age. Abingdon: Routledge.