ABSTRACT

A skilled music education workforce is essential to ensure longevity of music-making for future generations of young learners and access to high-quality instrumental music tuition remains crucial for school-aged pupils. Yet, Higher Education providers, including conservatoires, are not held accountable for providing high-quality pedagogical training to ensure that music graduates are best equipped to support musical learning in children and young people. Perspectives on instrumental teacher education obtained through interviews with academics at six English conservatoires were triangulated with questionnaire responses from senior leaders of 66 Music Education Hubs in England. Findings revealed institutional challenges relating to the privileging of principal study activity; inconsistent pedagogical provision across the conservatoire sector, and a mismatch between students’ pedagogical training and employer expectations. Closer collaboration and dialogue between institutions and employers are recommended to ensure that conservatoire graduates are trained appropriately to meet the needs of the modern music education sector.

Introduction

Access to instrumental music tuition is one of the principal ways in which school-aged pupils are able to experience long-term music-making, yet for many years, the quality of instrumental teaching has been highly variable across England (Ofsted Citation2009). With no single quality assurance measure in place, instrumental teachers are at liberty to set up in private practice with no formal qualifications whatsoever (Barton Citation2019, 2). Similarly, the School Teachers’ Pay and Conditions set out by the Department for Education (DfE Citation2021) permits instrumental music teachers to be employed without Qualified Teacher Status (QTS) in schools and Music Education Hubs (MEHs) (MEHs were formed in response to the first National Plan for Music Education in 2011, to provide access, opportunities and excellence in music education for all children and young people in England). Many of these teachers emerge from music degree courses at conservatoires where they have been trained to an extremely high level in the performance of Western classical music: the ‘principal study’ discipline. According to Mills (Citation2005, 63) conservatoire students ‘typically do not aspire to obtain QTS’, possibly because it entails taking a year out of their emerging professional performing careers to pursue a year-long intensive postgraduate teacher training route based almost exclusively in a classroom environment, resulting both in loss of earnings and valuable professional connections gained during their undergraduate studies. Furthermore, instrumental teaching qualifications available to undergraduates through organisations such as the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music (Citationn.d) and Trinity College London (Citationn.d) involve an additional time commitment and financial investment that may conflict with full-time study. Yet, it is crucial that emerging music professionals are adequately prepared to respond to the rewards and challenges of practices in instrumental teaching that are likely to be very different from their own learning experiences in music.

Over a decade ago, in the Review of Music Education in England (Henley Citation2011, 26) it was recommended that ‘Conservatoires should be recognised as playing a greater part in the development of a performance-led music education workforce of the future’. The subsequent first National Plan for Music Education (NPME) (DfE and DCMS Citation2011, 21) recognised that such a workforce includes ‘musicians for whom music education may make up only part of a portfolio career’, though it did not address sufficiently the specific training needs of this particular group, which includes conservatoire graduates. The need to build a workforce of skilled music education professionals is also highlighted by Daubney, Spruce, and Annetts (Citation2019) and The Music Commission (Citation2019). However, these reports show that the supporting ecosystem for music educators is in decline. This strongly implicates Higher Music Education Institutions (HEMIs), who have a crucial role to play in preparing music students to undertake professional music educator roles. Indeed, according to the recently revised National Plan for Music Education (NPME2) (DfE and DDCMS Citation2022, 68) ‘Higher education […] institutions are an important part of the overall music education landscape and are vital to ensure a strong talent pipeline into the global music industry’. Despite this claim, the most recent Subject Benchmark Statement for Music published by the Quality Assurance Agency (QAA Citation2019) only defines in broad terms what a music degree involves, and according to Tatlow (Citation2022), categorisation and reporting processes employed by the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) do little to add clarity. There is currently no compulsion for HEMIs to play their part in providing bespoke training for aspiring instrumental teachers, even though ‘teaching’ is listed third amongst the possible career paths for musicians after performing and composing.

To ensure that teachers and practitioners are ‘best equipped to support children and young people’, the importance of building skills through connecting with other teachers, practitioners and the ‘wider music education ecology’ is emphasised in NPME2 (DfE and DDCMS Citation2022, 66). ‘At every stage, musical progression will best be facilitated through a joined-up partnership of organisations putting children and young people first’ (63). According to Fautley, Kinsella and Whittaker (Citation2019, Citation2022 309), partnership working is a complex process in which an awareness of and sensitivity towards others’ situations and ontologies is vital if they are to be successful and beneficial for all parties. With this in mind, the current article draws together perspectives on instrumental teacher education from both within and outside the conservatoire sector to respond to the question: ‘What are the main challenges faced by the conservatoire sector in preparing students for careers in instrumental teaching?’

Materials and methods

A mixed-methods approach was adopted to ‘examine current attitudes, beliefs, opinions or practices’ (Creswell Citation2012, 37) regarding instrumental teacher education. Given the author’s positionality as an academic involved in the delivery of instrumental teacher education at Royal Birmingham Conservatoire, UK, it was deemed necessary to exclude this institution from the study and instead to focus on outsider perspectives (Reed-Danahay Citation2006) to mitigate against inevitable bias, whilst increasing accuracy and reliability of data through triangulation (Denscombe Citation2014).

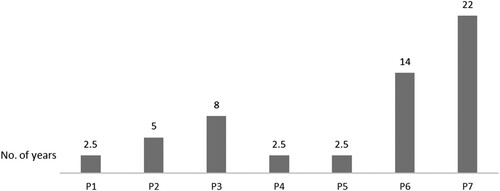

Firstly, seven academics with responsibility for designing, overseeing or delivering pedagogical training in six other conservatoires in England were selected through ‘theoretical sampling’ (110). The remit of participants interviewed included those who taught and/or led one or more music pedagogy modules themselves, through to those who line-managed colleagues to deliver provision across whole-year groups. Whilst some conservatoires had a recognised ‘department’ for music education with one or more members of staff leading provision in this area, in others the oversight of such provision was absorbed into wider academic responsibilities with no specific department or key staff member identified. Six of the seven participants interviewed originally trained at a conservatoire themselves and, at the point when the interviews took place, three participants were teaching at the conservatoire at which they previously studied, findings reminiscent of Mills (Citation2004), where graduates returned to their former institution to teach. The length of time participants had worked at their current institution ranged from 2.5 to 22 years, as shown in :

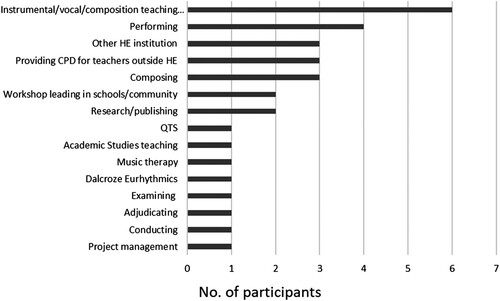

The conservatoire academics each brought to their role a wide skill set developed as part of a portfolio career, including, for the majority, significant prior experience of teaching instruments in schools (though intriguingly, only one academic reported QTS status, as shown in ).

The interviews were conducted across May–July 2019, either in the participants’ place of work or another setting of their choice. A semi-structured format allowed flexibility to ‘follow up ideas, probe responses, [and] investigate motives and feelings’ (Bell Citation2010, 161). Participants were invited to speak about their teaching philosophy and the nature of the instrumental teacher training offered by their institution.

Subsequently, an online questionnaire was distributed to 122 MEHs across England. The questionnaire was devised using a General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) compliant online survey tool: onlinesurveys.ac.uk to protect participants’ sensitive data (BERA Citation2018) and its design followed recommendations of Bell (Citation2010) and Cohen, Manion, and Morrison (Citation2018). Questions aimed to elicit responses regarding the areas within which recent conservatoire graduates would be required to teach and the particular challenges they might face. Employers were also asked about the extent of their involvement in course development and/or delivery in conservatoires. A cross-sectional sample of 66 senior leaders responded between December 2019–February 2022 representing 54% of MEHs with varying organisational structures across a wide geographical area. These participants were likely to have been conservatoire or university trained; may have begun their teaching careers as peripatetic staff within a MEH or elsewhere, and/or been former classroom teachers, active performers, or professionals working in areas other than music. Despite these variables within the sample, MEH representatives were viewed by the researcher as a homogenous group for the purposes of data analysis, since the main aim was to obtain a wide range of anonymous views.

Ethical approval was granted in accordance with institutional policies and frameworks and a rigorous, transparent and respectful approach was adopted throughout the research. Informed consent was gained prior to the gathering of data from conservatoire academics and employers through documentation clarifying the voluntary nature of participation, as well as the proposed benefits and potential risks. Permission was also sought in advance to record the interviews for transcription purposes. All data was stored securely and confidentially on encrypted, password-protected devices, and individuals were assured that they would never be identified by name or geographical location. (To preserve participants’ anonymity, alphanumeric codes are employed throughout this paper: P1–7 for conservatoire academics and H1–66 for employers.) Graphical representations of quantitative data were automatically generated from the questionnaire via the onlinesurveys.ac.uk platform. Qualitative data from both the questionnaires and the interviews were read multiple times for familiarisation purposes prior to being transferred into Excel and computer assisted software (NVivo) respectively to facilitate manual thematic analysis. Here, codes and categories were assigned to meaningful segments of text, and subsequently eliminated or merged to create overarching themes (Creswell Citation2012). The emerging institution-focused themes ‘valuing (staff/students)’ and ‘curriculum/provision’ and employer-focused themes: ‘preparedness: (incompetence/indifference)’ and ‘partnership potential (perceived barriers)’ are discussed below in turn.

Results and discussion

Institutional valuing of instrumental teacher education

Conservatoire academics’ reflections on their philosophy and approach to curriculum design demonstrated their commitment to preparing students for careers that included instrumental teaching. For example, teaching was perceived ‘a caring role’ (P5) and was recommended to students as ‘an extremely worthy occupation’ in which they could play a vital role in ‘shaping the future’ (P3).

However, interviewees sensed resistance amongst some of their colleagues who did not necessarily share their passion for developing students’ teaching skills. One academic spoke of colleagues with ‘an old-fashioned snobby attitude’ and needing to convince them of the value of such provision by speaking to them individually to ‘break down barriers’ (P1). Another detected ‘a little bit of a disconnect’ between pedagogical studies and performance in their institution, and expressed frustration that colleagues were ‘not always as open-minded and aware as they might be’ (P4). It was suggested that the ‘messages’ that students receive even before they arrive at an institution, for example via the conservatoire’s website, at open days and even at the audition, will play a part in influencing the extent to which students value pedagogy modules within their course:

It’s not just what you provide, it’s how you […] communicate it […] If [students] are told we’re about performing excellence, for example, or you’re here primarily to develop as a performer […], then they’re the wrong messages, or they’re incomplete messages (P5).

A lack of institutional valuing also manifested itself in equivocal responses regarding students’ and graduates’ achievements resulting from pedagogical training. Participants implied that, while performance successes were highly celebrated by conservatoires; graduates’ and current students’ achievements in the field of music education were less widely acknowledged. This is akin to findings by Ford (Citation2010, 218):

The conservatoire notice boards offered visual clues as to the official values of the institution […] the celebration of competition wins and orchestral positions gained by alumni, along with the distinct absence of congratulations to students who had won jobs as say, teachers or jobs outside of the music profession.

The main challenge, as ever, is to negotiate the competing ingredients of a music undergraduate degree at conservatoire level because everyone wants a piece of the cake and there are certain skills that are considered to be essential and need to be covered, and yet it’s all open to negotiation. Do we need as much music history? Do we need as much musicianship? Do we need as much weighting towards principal study? Maybe yes, maybe no? Maybe that could change across the years. All these are questions we can discuss (P5).

Provision for instrumental teacher education in conservatoires

Most conservatoires represented in this study offered a four-year BMus course, with one institution running a three-year programme. Commonalities in curriculum mapping were clear with each institution offering a range of compulsory and/or optional credit-bearing music education modules utilising two curricular ‘strands’, namely teaching and workshop facilitation (often some form of music in the community). Some pedagogy modules required students to engage in interdisciplinary collaboration across genres, with many including some form of work experience. Such approaches to curriculum design adhere to recommendations set out in the Subject Benchmark Statement for Music (QAA Citation2019, 1), which ‘allow[s] for flexibility and innovation in course design’.

However, it would seem that ‘flexibility and innovation’ has led to a lack of parity across the conservatoire sector regarding at what stage(s) in a BMus course pedagogical modules should be studied. Data suggested that provision tended not to be ‘joined up’ from one year to the next because the curriculum was often not structured in a way that enabled students to build on acquired skills. In some conservatoires, it was not possible to specialise equally in teaching and workshop facilitation, since the curriculum structure forced students to choose between one or the other. Furthermore, approaches to assessment varied between modules and across institutions. In many conservatoires, as noted by Boyle (Citation2021), postgraduate provision for pedagogical training seemed to take priority over undergraduate provision.

Of the six conservatoires participating in the study, only four seemed to offer principal study-specific pedagogical training, for example: strings, woodwind, brass, percussion, keyboard and voice; while pedagogical training for non-performance areas, for example, composition, was rarely bespoke. Where departmental heads were directly involved the delivery of pedagogical training, participants believed this to be beneficial in engendering student engagement ‘because everything that comes down from [principal study] has a priority element compared to other areas of the curriculum' (P7). It was reported that heads of departments were given ‘free rein’ (P1) and ‘autonomy’ (P7) to develop and deliver their provision as they thought best. Whilst this approach was presumably advantageous in building trust and cooperation between colleagues as well as enthusiasm for the subject, it raises questions about quality assurance, possibly to the detriment of students’ learning and development as music educators: ‘We don’t line manage [the performance staff]. We’re not always convinced that they’re terribly up to date with their [pedagogic] practices’ (P6). Indeed, conservatoire staff are invariably not required to gain a formal teaching qualification, and many have no formal pedagogical training at all (Gaunt Citation2008).

There appeared to be inconsistency regarding at what point in the course pedagogical training was introduced: only three institutions embedded pedagogical training from Y1, enabling students to build on informal teaching experiences they may have gained prior to commencing their undergraduate studies. In one institution, a Y1 module enabled students to ‘dip their toe in the water’ and ‘begin to think about the skills that a teacher actually needs’ (P5) by observing in a one-to-one instrumental lesson setting (normally the conservatoire’s junior department). Elsewhere, equivalent Y1 modules aimed to develop students’ transferable skills through ‘improvisatory, creative work […] to get them communicating with one another and learning from different disciplines’ (P7). Similar inconsistency in Y2 provision ranged from no core pedagogical training whatsoever, through to specialist modules focusing on interactive performances or projects that would be devised by students and subsequently delivered in real-life settings. In the institution of participant 2, there was no credit-bearing opportunity for students to develop their skills in follow-up modules, though ‘the basics of […] one-to-one, [small] group and whole class instrumental teaching’ were explored in Y2.

Across Y3–4, most conservatoires offered optional modules in instrumental music pedagogy and/or workshop delivery, often with some form of embedded professional placement connected with, for example, a Music Education Hub, an independent school, or a Learning and Participation department linked to an orchestra, opera company or other arts organisation. Inevitably, the nature of placements varied between conservatoires due to geographical location or other factors. In some instances, where students were evidently required to source placements themselves, it was not possible to discern from the interviews the extent to which these were ‘vetted’ by institutions. One institution encouraged students to ‘lead some sectionals […] within ensembles’ or do ‘a little bit of co-teaching under the supervision of another teacher’ (P5), though it was not clear whether mentors in external settings received training or were made aware of module learning outcomes, raising wider questions about quality assurance procedures involving external partners. Several institutions appeared to avoid potential complications by utilising their own junior department as a means of offering observation opportunities. However, doing so could mean that this ‘relatively high pressure and high expectation environment’ (P6), might be the only professional teaching setting students engage with during their entire undergraduate course, thus providing a very limited outlook on the instrumental teaching profession and the many factors that influence pupils’ learning and development. Arguably, it may also reduce the possibilities for raising students’ awareness of unfamiliar socio-economic and multi-cultural environments where music-making happens.

One institution required students taking Y3–4 pedagogy options to be teaching already: ‘If they don’t have any teaching then […] we advertise a free course of lessons […] to a [non-music] student’ (P6). Other institutions were more inward looking with provision not extending beyond the lecture room: ‘It’s pretty much all taught in-house’ (P3) or ‘They get paired up with somebody who’s a complete beginner. [While] they’re very musically able, they’ve never played that instrument before […]. It’s as much like teaching a complete beginner as we can make it’ (P2). Elsewhere, students were encouraged to find their own placements: ‘They go back to their old school, or observe each other […] or their old teacher’ (P6). While experiences such as these are arguably valuable in providing a testing ground for articulating and demonstrating pedagogical concepts, there is a risk that teaching a peer or shadowing a former teacher might magnify students’ predisposition to teach as they were taught themselves. The outlook of P3 suggests that for many instrumental teachers, ‘teach as taught’ approaches can result in negative outcomes:

I think a lot of […] students who end up in music college have often been taught in a particular kind of way [and] represent somewhere between 0–5% of their teacher’s pupils who managed to stick with that kind of teaching […]. Often the other 95% will have given up, having decided they don’t like […] music. […] That is a terrible indictment of the kind of teaching that has prevailed in many nations in the world for many decades […]. Often a teacher goes on to teach in the way that they were taught and except for a few cases, that’s not a good idea.

Employer perceptions of conservatoire graduates’ preparedness for the music education workforce

Issues of institutional valuing discussed by conservatoire academics align with responses from employers who perceived varying levels of ‘incompetence’ (defined as inability to teach effectively) and ‘indifference’ (defined as a negative attitude towards pursuing teaching as a career, or a reluctance to develop as a teacher) in their conservatoire graduate employees. In fact, the following employer statement correlates directly with the stance of P3 above:

As a general rule, graduates of both conservatoires and university music departments are miles away from being ready for the modern music education sector. Invariably they have been taught one-to-one their whole lives, including at conservatoire. Our experience is that this teaching they have experienced is old-fashioned ‘master says and pupil does’. We feel that conservatoires have a lot to do in order to address the quality of individual teaching and learning in their own settings – rather than just a focus on ‘good players’ (H26).

Perceived graduate incompetence

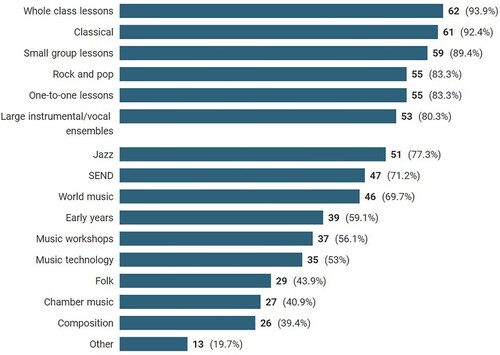

According to employer respondents, conservatoire graduates working for MEHs were required to teach across a range and breadth of specialisms, as illustrated in .

It is significant that Whole Class Ensemble Teaching (WCET) was ranked top of the list, given the reach of WCET across England and its delivery having become a ‘core role’ of MEHs via NPME (DfE and DCMS Citation2011, 26; Fautley, Kinsella, and Whittaker Citation2019). It is also striking that ‘rock and pop’ and ‘one-to-one lessons’ were ranked equally, suggesting that conservatoire students should be just as prepared to teach the former as the latter. Indeed, the popularity of ‘rock band’ provision across schools and MEHs is cited by Fautley and Whittaker (Citation2018). Small-group teaching was ranked more highly than one-to-one teaching and ensemble direction was also considered hugely important. A range of additional specialisms fell below 80%, including ‘others’ specified by participants, such as rap, contemporary, DJ training, theory, musicianship, piano accompaniment, instrument repair, leading singing festivals (or other one-off events) and offering alternative provision for young people in pupil referral units (PRUs). Some hubs expected employees to teach ‘multi genres’ and ‘composition [when] integrated into whole class […] teaching’ (H15). However, MEHs had found ‘very few conservatoire graduates with real-life rock and pop or music technology experience’ (H54), or many with a ‘folk or world music specialism’ (H53) suggesting that instrumental teacher education in conservatoires could be more diverse to assist with this, especially given wider national concerns around equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) in the music education workforce (Spence Citation2021). It is possible that a lack of awareness of musical diversity may manifest itself even before students begin their conservatoire training: at least for many students in England, the content of A-level music syllabuses represents ‘a kind of scholastic canon’ (Whittaker Citation2020, 18), which inevitably forms a significant proportion of the cultural capital students bring to their undergraduate studies and future employment.

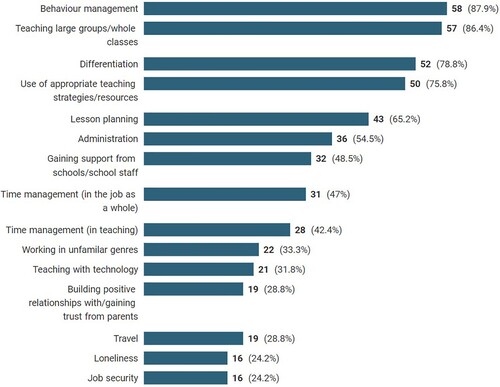

The key challenges experienced by early-career instrumental teachers, as perceived by employer respondents, are shown in .

With a certain empathy, MEH participants stated that ‘the expertise required to command a full class of young people is not covered during conservatoire courses’ (H52) so new graduates ‘have limited experience and can find teaching […] whole classes intimidating and discouraging’ (H30). Even where small-group teaching was concerned, it was suggested that conservatoire students were simply ‘not prepared for the reality of […] teaching in schools’ (P39) and that delivering short workshop sessions during their undergraduate degrees would ‘rarely equate to longer term weekly teaching of this kind’, giving them ‘a distorted view’ of the challenges involved (H65). Indeed, as noted by Gane (Citation1996, 64), group teaching (of any size) brings its own set of diverse challenges:

Class music teachers face, in each year group, children whose diverse interests, background, music education to date, abilities, and needs demand great skill in the planning of learning so that it is effective for each pupil. Instrumental teachers working in school have to encompass similar diversity, compounded by inconsistency of age, period of learning and instrument, perhaps even within the same group. If, added to this, there is the differing character of individual teachers and schools, it is a mixed picture indeed.

Really basic stuff seems to be missing, e.g. transposing, playing by ear, even reading different clefs, preparing a score as a conductor, basic conducting technique, how to plan and structure a rehearsal for young people [and] arranging rewarding music for beginner players’ (H3).

Despite technological advancements in recent years, employers felt that ‘typically, most graduates are not particularly conversant with music IT’ (H52), or even set up for ‘using technology at a basic level’ (H2). Nor are they ‘competent in enabling their pupils to improvise […], often rely[ing] on tutor books to drive the structure the lesson, rather than selecting appropriate repertoire that fits with the focus of their lesson planning’ (H4). Like Participant 3 above, several hub representatives perceived that ‘Most conservatoire students are limited to teaching what they themselves have been taught’ (H1) and ‘it is sometimes difficult for new teachers to understand that the students they teach are not always as passionate about music as they are’ (H20). Moreover, they ‘have very little understanding of the basic building blocks of music and how musical learning develops’ (H62).

We find that new teachers teach the way they’ve been taught at graduate level […]. The focus nearly always emphasises technical perfection over musical fluency (which is necessary before technical aspects can be improved). Lesson pace is often far too slow as a result, and sometimes the angle of a finger seems more important than making sense out of a musical phrase (H6).

Perceived graduate indifference

A further significant challenge for hubs related to retaining recent conservatoire graduates as employees . Invariably, employers perceived that conservatoire graduates saw teaching ‘as a stopgap’ (H6), or ‘as something they might do on the side’ (H46). Others concurred: ‘There are some students who see teaching as the means to generate income while they pursue performance rather than investing early on in becoming the best educator they can be’ (H33). This perceived tendency for conservatoire graduates to prioritise performing work over their teaching was highly problematic for employers who believed that ‘many see it as an easy option and underestimate how skilled the best instrumental tutors are’ (H25).

Equally, employers could see why teaching for a music hub might not be appeal to some conservatoire graduates. One participant intimated that the portfolio nature of their careers may preclude them from any sense of belonging to an organisation or ‘workforce’, reflecting the ‘de-professionalisation’ described by Daubney, Spruce, and Annetts (Citation2019, 28).

‘Job security is a huge issue. The employment structures in many hubs have weakened as have the pay and conditions. It’s difficult to see why an aspiring young student would seek [to develop] a career in some hubs. The CPD systems that allowed many instrumental teachers to gain PGCE training and pay no longer exist and that has undoubtedly downgraded the attractiveness of peripatetic teaching as a career. This leads to ‘part-time-ism’ across the workforce which also leads to loneliness (H33).

We are proud to offer salaried posts. However, many really struggle with the reality of working full time in the sector and the commitment required to develop themselves, work on a growth mind-set and ensure that teaching and learning is exciting and relevant to children and young people from all backgrounds (H26).

Partnership potential

Some employers suggested that they would be keen to encourage music students to view instrumental teaching as a means to ‘career progression’ (H13), as opposed to ‘just a way to pay the bills’ (H20). However, at the time of the study, only a small proportion of hubs (27.3%) had previously been asked to collaborate with conservatoires, for example, by delivering one-off lectures, offering talks at careers events or contributing to course validation, and only 30.3% of hubs reported that they had worked in partnership with institutions to offer placements (though 13.6% of respondents referred to collaborations with university music departments rather than conservatoires specifically, and another 7.5% referred to PGCE courses as opposed to undergraduate modules). Representatives from 57.6% of hubs who had not previously collaborated with conservatoires were keen to do so: ‘This would be a great step forward in helping to forge career pathways for graduates’ (H7) and ‘I would jump at the chance if offered. This is an area that interests me greatly and I can see so many mutual benefits’ (H58).

However, in some instances where hubs had offered their services to conservatoires, their support had not been welcomed:

Due to the unpreparedness of students, [we] have attempted to offer support for undergraduates in the local conservatoire. There is very little recognition of the extent of the problem there, and the support that our experience and knowledge could give (H15).

should be working closely with conservatoires in this field, as hubs are a major employer of musicians. There continues to be an identity crisis for [teachers] and we can turn this around if we can spend time with undergraduates shaping their understanding of this exciting and rewarding role (H26).

The apparent rejections of employer support by institutions are highly concerning, given that, according to employer respondents, conservatoire graduates were seemingly unprepared by their institutions for instrumental teaching in a hub setting at the time of the study. However, in addition to a very full curriculum, it is plausible that the lack of formal training requirements in place for the instrumental teaching profession may have led conservatoires to lack confidence in the quality of teaching within hubs, precluding the formation of collaborative relationships in a climate where conservatoires are subject to institutional quality assurance measures. Additionally, restrictions were posed by distance and travel costs where hubs did ‘not have a conservatoire in the area’, thus limiting the support the hub could offer to students (H59).

Nevertheless, MEH representatives believed they were ‘an underused resource in conservatoire training, [being] in a unique position to know what is required of a conservatoire graduate’ in the professional teaching context (H58). This is highly pertinent since hubs revealed that they would be unlikely to employ a recent conservatoire graduate who had no teaching experience. Therefore, accepting offers of support from external colleagues who ‘would dearly love to be involved with helping conservatoires to prepare the next generations of graduates for work with modern Music Education Hubs’ (H31) could be a positive step in helping conservatoires respond to the government directives outlined in the introduction above.

Conclusion and recommendations

These findings have offered an indication of the strength of fit between conservatoire-led instrumental teacher education in England and the needs of Music Education Hubs.

Challenges

It would seem that one of the main challenges faced by the conservatoire sector in preparing students for careers in instrumental teaching, is the ‘hegemonic culture’ (Bruner Citation1996) underlying the conservatoire ecosystem. Whilst on the one hand, conservatoires prioritise training in the principal study discipline in order to prepare the performers of the future, on the other, this long-established tradition poses a significant threat to future music education workforce development. It would seem therefore, that conservatoires need to take steps to eradicate disparaging remarks and negative attitudes towards instrumental teaching as a career choice and change traditional perceptions of failure into strong indicators of success.

A second, related challenge is the inconsistency of provision for instrumental teacher training across the conservatoire sector. This raises significant questions about whether there is a need to monitor pedagogical training more closely, to ensure that wherever students choose to study they can access comparable instrumental teacher training at undergraduate level and that those conservatoire staff delivering provision are up to date with wider practices in music education.

Perceived institutional barriers present a third challenge in relation to training the next generation of music educators, restricting collaboration between conservatoires and employers. Ideally, such barriers would be broken down, and funding would be made available to enable final-year undergraduate conservatoire students to undertake a mandatory minimum allocation of mentored placement activity. If completed successfully, this could then be endorsed by employers in partial fulfilment of a specialist instrumental teaching qualification that could be completed across the first year of employment, under the ongoing supervision of an approved mentor. Such a scheme would not only help to improve the quality of learning for children and young people: arguably, it would help graduates to feel more valued as teachers and inclined to invest in their teaching skills. Internship initiatives, such as those that already exist in a few MEHs and other arts organisations, also provide ongoing professional development for established practitioners who can benefit from the reciprocal learning opportunities that mentoring offers through mutual reflection.

Limitations

Limitations of the research include the small number of conservatoire academics taking part, though all conservatoires (other than the author’s institution) offering BMus courses across England were represented. Whilst a wide range of experiences and backgrounds amongst MEH participants brought multiple perspectives to the research, it was not possible to ascertain whether/how differences in organisational structure of MEHs impacted the findings. However, responses were likely to vary depending on the nature and extent of their association with, and geographical proximity to, one or more conservatoires. Furthermore, the findings were likely to have been influenced by participant bias: whether or not MEH senior leaders were themselves conservatoire-trained, it would have been impossible for them to remain completely impartial about their own ‘learning past’ (Kegan Citation2018, 39). In needing to be selective due to the boundaries of the research, it was not feasible to triangulate the MEH data by seeking the perspectives of directors of music from independent school music departments, even though these are another main source of employment for conservatoire graduates. Thus, this remains a potential avenue for future research.

Closing remarks

It is implied within NPME2 (DfE and DDCMS Citation2022, 66) that instrumental teachers belong to an ‘out-of-school workforce’. Perhaps, at least in part, this is an attempt to differentiate classroom teachers with QTS from instrumental teaching practitioners who are classed as ‘unqualified’ and therefore do not identify as ‘real teachers’ (Boyle Citation2021, 57). Arguably, this is an oversight, given that alongside those instrumental teachers working in private practice, significant numbers work in classrooms (Shaw Citation2021), not least due to the reach of Whole Class Ensemble Teaching (WCET) across England.

Whilst each conservatoire ‘offers a distinctive educational experience, with its own mission and focus, contributing to the healthy diversity of the sector’ (QAA Citation2019, 6), there is an urgent need to ensure that students who aspire to teach are sufficiently prepared to join the modern music education workforce, having witnessed and experienced up-to-date practices that have direct relevance for their early teaching careers. Indeed, given the ‘longer-term implications […] for the future of school, college and university music education, and perhaps more importantly, for individuals and society’ (Burland Citation2020, 2), one might challenge and question whether the privileging of principal study activity is appropriate for the development of the twenty-first century musician if it leaves insufficient space or flexibility in the curriculum to adequately develop pedagogical training.

According to NPME2 (DfE and DDCMS Citation2022, 69), the UK Government’s pilot of a new Portable Flexi-Job Apprenticeship will allow apprentices to move between different employers in order to become ‘occupationally competent’. The potential to use this, or an equivalent model, at HE-graduate level to provide bespoke training for early-career instrumental teachers across a wide geographical area is significant. The collective insights of employers and HEMIs will nevertheless be highly pertinent when developing curricula for instrumental teacher education in future. Indeed, the sensible way forward – from both perspectives and to mutual benefit – would seem to be to engage in much closer, ongoing dialogue.

Acknowledgements:

With grateful thanks to my doctoral research supervisors and academic colleagues for their ongoing support, and to all who participated in the research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Luan Shaw

Dr Luan Shaw is Associate Professor: Director of Postgraduate Studies at Royal Birmingham Conservatoire (RBC). She has practised as a performer and instrumental teacher for over 30 years, and leads instrumental teacher education for final-year undergraduates and postgraduates at RBC. Luan’s research explores how undergraduate conservatoire students can develop pedagogical knowledge. Informed by academics, employers, students and alumni, it aims to counteract a long-held notion that teaching is as a second-class profession, and demonstrates that, through specialist modules, professional placements and mentoring, students can develop transferable skills, and a sense of social responsibility to nurture the next generation of musicians.

References:

- Associated Board of the Royal School of Music (n .d). “Instrumental/Vocal Teaching Diplomas.” https://gb.abrsm.org/en/our-exams/diplomas/instrumentalvocal-teaching/.

- Barton, D. 2019. “The Autonomy of Private Instrumental Teachers: Its Effect on Valid Knowledge Construction, Curriculum Design, and Quality of Teaching and Learning.” PhD diss., Royal College of Music.

- Bell, J. 2010. Doing Your Research Project. 5th edn. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- BERA. 2018. Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research.” https://www.bera.ac.uk/researchers-resources/publications/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018.

- Boyle, K. 2021. “The Instrumental Music Teacher: Autonomy, Identity and the Portfolio Career in Music.” In ISME Global Perspectives in Music Education. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bruner, J. S. 1996. The Culture of Education. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Burland, K. 2020. “Music for All: Identifying, Challenging and Overcoming Barriers.” Music & Science 3: 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059204320946950.

- Chappell, S. 1999. “Developing the Complete Pianist: A Study of the Importance of a Whole-Brain Approach to Piano Teaching.” British Journal of Music Education 16 (3): 253–62. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051799000340.

- Cohen, L., L. Manion, and K. Morrison. 2018. Research Methods in Education. 8th edn. London: Routledge.

- Creswell, J. W. 2012. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. 4th edn. Boston: Pearson.

- Daubney, A., G. Spruce, and D. Annetts. 2019. “Music Education: State of the Nation.” Report by the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Music Education, the Incorporated Society of Musicians and the University of Sussex. https://www.ism.org/images/files/State-of-the-Nation-Music-Education-WEB.pdf.

- Denscombe, M. 2014. The Good Research Guide. 4th edn. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- DfE and DCME (Department for Education and Department for Culture, Media and Sport). 2011. “The Importance of Music: A National Plan for Music Education.” https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-importance-of-music-a-national-plan-for-music-education.

- DfE and DDCMS (Department for Education and Department for Digital Culture, Media and Sport). 2022. The Power of Music to Change Lives: A National Plan for Music Education. The Power of Music to Change Lives: A National Plan for Music Education - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk).

- DfE (Department for Education). 2021. “School Teachers’ Pay and Conditions.” https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-teachers-pay-and-conditions.

- Fautley, M., V. Kinsella, and A. Whittaker. 2019. “Models of Teaching and Learning Identified in Whole Class Ensemble Tuition.” British Journal of Music Education 36 (3): 243–52. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051719000354.

- Fautley, M., and A. Whittaker. 2018. “Key Data on Music Education Hubs.” Birmingham City University.

- Ford, B. 2010. “What are Conservatoires For? Discourses of Purpose in the Contemporary Conservatoire.” PhD diss., University of London.

- Gane, P. 1996. “Instrumental Teaching and the National Curriculum: A Possible Partnership?” British Journal of Music Education 13 (1): 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051700002941.

- Gaunt, H. 2008. “One-to-one Tuition in a Conservatoire: The Perceptions of Instrumental and Vocal Teachers.” Psychology of Music 36 (2): 215–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735607080827.

- Goddard, E. 2002. “The Relationship Between the Piano Teacher in Private Practice and Music in the National Curriculum.” British Journal of Music Education 19 (3): 243–53. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051702000335.

- Henley, D. 2011. “Music Education in England: A Review by Darren Henley for the Department for Education and the Department for Culture, Media and Sport. Department for Education.” https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/music-education-in-england-a-review-by-darren-henley-for-the-department-for-education-and-the-department-for-culture-media-and-sport.

- Kegan, R. 2018. “What “Form” Transforms?: A Constructive-Developmental Approach to Transformative Learning.” In Contemporary Theories of Learning: Learning Theorists in Their Own Words. 2nd edn, edited by K. Illeris, 29–45. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Kinsella, K., M. Fautley, and A. Whittaker. 2022. “Re-thinking Music Education Partnerships Through Intra-Actions.” Music Education Research 24 (3): 299–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2022.2053510.

- Mills, J. 2004. “Working in Music: Becoming a Performer-Teacher.” Music Education Research 6 (3): 245–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461380042000281712.

- Mills, J. 2005. “Addressing the Concerns of Conservatoire Students About School Music Teaching.” British Journal of Music Education 22 (1): 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051704005996.

- The Music Commission. 2019. “Retuning Our Ambition for Music Learning: Every Child Taking Music Further.” ABRSM/Arts Council England. http://www.musiccommission.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/WEB-Retuning-our-Ambition-for-Music-Learning.indd_.pdf.

- Ofsted. 2009. “Making More of Music: An Evaluation of Music in Schools 2005/08.” https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/308/1/Making%20more%20of%20music.pdf.

- Porton, J. J. 2020. “Contemporary British Conservatoires and Their Practices – Experiences from Alumni Perspectives.” PhD diss., Royal Holloway, University of London.

- QAA (Quality Assurance Agency). 2019. Subject Benchmark Statement: Music. 4th edn. Gloucester: QAA. https://www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaa/subject-benchmark-statements/subject-benchmark-statement-music.pdf?sfvrsn=61e2cb81_4.

- Reed-Danahay, D. 2006. “Autoethnography.” In The Sage Dictionary of Social Research Methods, edited by V. Jupp, 33–35. London: Sage Publications.

- Shaw, L. 2021. “From Student to Professional: Recent Conservatoire Graduates’ Experiences of Instrumental Teaching.” British Journal of Music Education 38 (1): 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051720000212.

- Spence, S. 2021. Equity, Diversity and Inclusion. London: Music Mark. https://www.musicmark.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Music-Mark-EDI_Report.pdf.

- Tatlow, S. 2022. “Exploring Issues in Categorisation of Higher Music Education Courses Through FOI Surveys of Gender Demographics in UK Higher Education Institutions.” British Journal of Music Education. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051722000249.

- Trinity College London. n.d. “Music Teaching Diplomas.” https://www.trinitycollege.com/qualifications/music/diplomas/teaching.

- Whittaker, A. 2020. “Investigating the Canon in A-Level Music: Musical Prescription in A-Level Music Syllabuses (for First Examination in 2018).” British Journal of Music Education 37: 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051718000256.